|

|

A Tale of Two Letters - The Early KO Engines

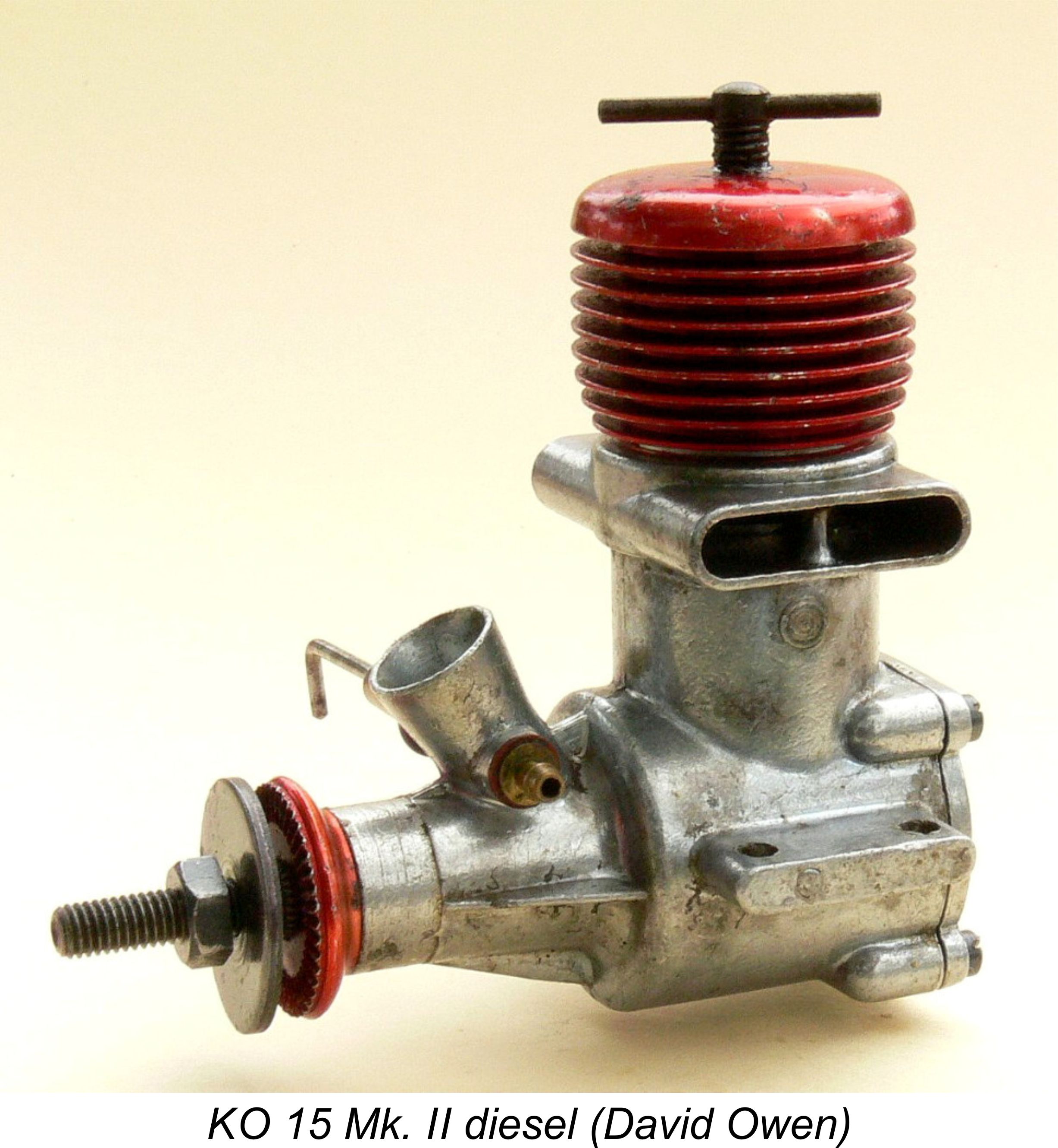

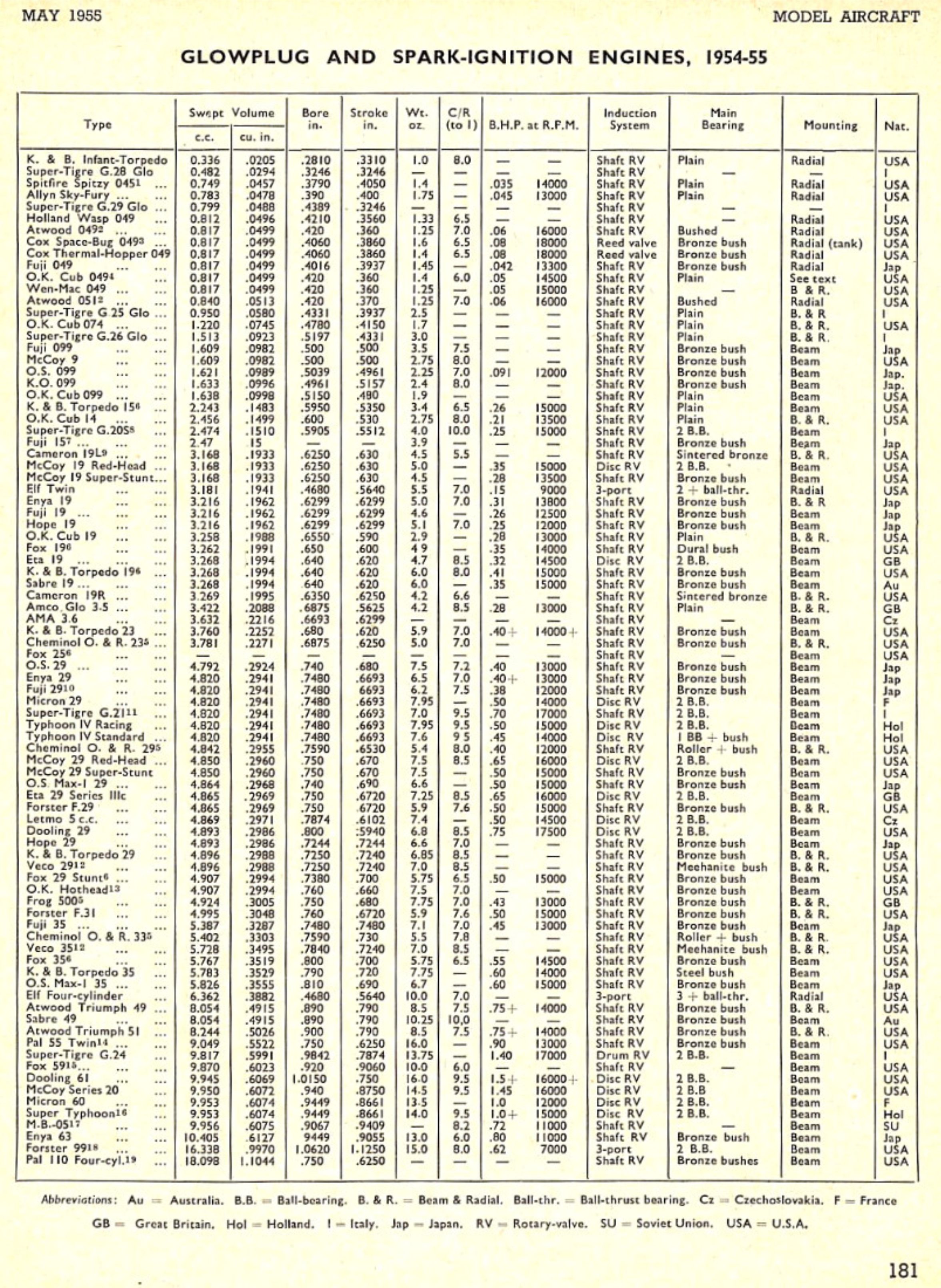

My focus here will be on several little-known Japanese engines which were commercially produced in the early post-war period by a manufacturing concern which subsequently became very well-known and successful but was just starting out at the time in question. The range in question was marketed under the KO brand-name. Many present-day classic model engine aficionados are aware of the KO diesel models in various displacements which were successfully marketed by the company during the mid 1950’s through into the mid 1960’s. The company’s neat little 0.099 cuin. glow-plug model from the 1950’s is also quite familiar to many folks. Finally, the company remains well-known to latter-day model R/C car racing enthusiasts through its highly-respected KO-PROPO range of R/C equipment. What is far less well-known is the fact that the involvement of the KO manufacturers in the model trade went much further back in time, to the earliest post-war years in fact. The KO brand was actually among the first modelling trade-names to emerge from the post-WW2 ruins of the Japanese economy during the mid 1940’s. Very few of today’s model engine enthusiasts appear to be aware of the engines which were produced under the KO banner during that early period. This is a pity, because these engines were both very well made and unusually interesting from a design standpoint. This being the case, I felt that it was time that these powerplants finally emerged from the shadows into the full light of published scrutiny. That will be my task in this article. It’s an undeniable fact that several of the early KO designs which laid the foundations of the company’s later success in the model engine field bore a striking resemblance to certain contemporary American products, including the OK engines which bore the same letters in reverse! This situation appears to warrant a closer look. So I'll begin at the beginning by setting the scene. But before doing so, it’s both my duty and my pleasure to acknowledge the considerable assistance rendered to me by my late good mate David Owen of Woolongong, Australia. David was most generous in providing both comments and images of KO models which do not form part of my collection. Thanks, mate! I’d also like to express my heartfelt appreciation of the work put in by my late dear friend Ron Chernich. Despite the life-challenging situation with which he was dealing when this article was in preparation, Ron remained the same cheerful and supportive colleague that he had been all along. An inspiration to all of us - cheers, amigo mio!! Background

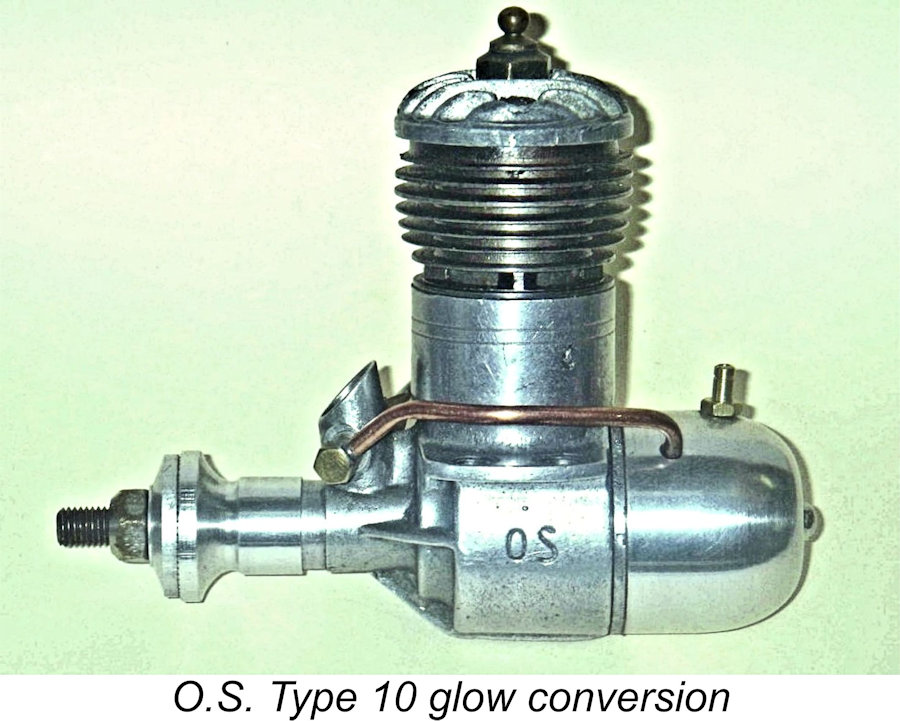

Unknown to modellers in other countries, a thriving power modelling scene had existed in pre-war Japan, with a number of commercial manufacturers such as O.S. emerging during the 1930’s to meet the

The manufacturing standards to which many of these engines were produced undoubtedly bore comparison with those prevailing elsewhere, a fact which took a remarkably long time to penetrate the somewhat elitist consciousness of the rest of the modelling world. Hence for the most part this early post-war activity went unnoticed and unreported outside of Japan. One of the Japanese model engine lines which got its start during this poorly documented but intensely active period was marketed under the KO banner. The However, the fact that the KO model engine range actually got its start in the late 1940’s with a line of spark ignition and glow-plug motors seems to be far less widely-known. As far as I’m aware, these early models have never previously been described in the English-language modelling media because their production preceded the time (c. 1954) when the products of the Japanese model engine industry became subject to ongoing scrutiny by contemporary English-language commentators. In addition, they are very rare indeed outside their native Japan, apparently being far from common even there. My good fortune in having managed to acquire several fine examples of these engines places me in the happy position of being able to do something to draw aside the veil that has hitherto shrouded these intriguing designs. Here goes …… Origins

Information obtained from a focused web search reveals that the Kondo brothers first entered the model industry immediately following the conclusion of WW2 - in fact, they are still viewed in Japan as pioneers of that industry. It’s actually fascinating to note the parallels between their entry into the model market and that of the Electronic Developments (E.D.) company in far-distant England. Like E.D., the KO company arose quite literally out of the ashes of war. Moreover, and again like E.D., their initial focus was on the production of radio control equipment for model aircraft rather than model engines. It appears that Jiro Kondo had been considering the question of radio control for models even while WW2 was still raging - indeed, it seems likely that he had been somehow involved with radio technology during the war, although we don’t know this for sure. However, such an involvement would go far towards explaining the confirmed fact that before the end of 1945 (only four months after the Japanese surrender) he had produced his first commercial R/C set for model aircraft use, thus beating E.D. into production by a considerable period of time. Although the original KO R/C equipment would be considered ultra-crude by today’s standards, it was actually extremely high-tech in the context of its times. Having developed their new state-of-the-art R/C equipment into a commercial form, the Kondo brothers naturally sought a suitable stage upon which to demonstrate their technical capabilities to potential buyers. It was this desire which motivated Jiro Kondo to undertake the necessary promotion and organizational steps to establish the first major hobby show in Japan. The resulting event still continues to this day in the guise of the annual Tokyo Hobby Show. Quite a testament to the energy and far-sightedness of Jiro Kondo! Thanks in part to initiatives such as the Tokyo show, the new company was soon well established as a significant player in the emerging post-war Japanese model industry. Given the fact that their initial success was founded upon their R/C equipment, it’s intriguing to note that the brothers were soon attracted to the then-burgeoning field of control-line model aircraft. This was most likely prompted at least in part by their residence in Tokyo, where suitable open areas for free flight and R/C flying were presumably in short supply. Control line with its greatly reduced space requirements must have appeared as an attractive alternative. The attention of the two brothers quickly became focused on the popular control-line speed events, for which contests and testing sessions were held regularly in a public square fronting the Imperial Palace in downtown Tokyo. They were to go on to become highly successful competitors in this technically-challenging field, establishing a number of Japanese records during the 1950’s.

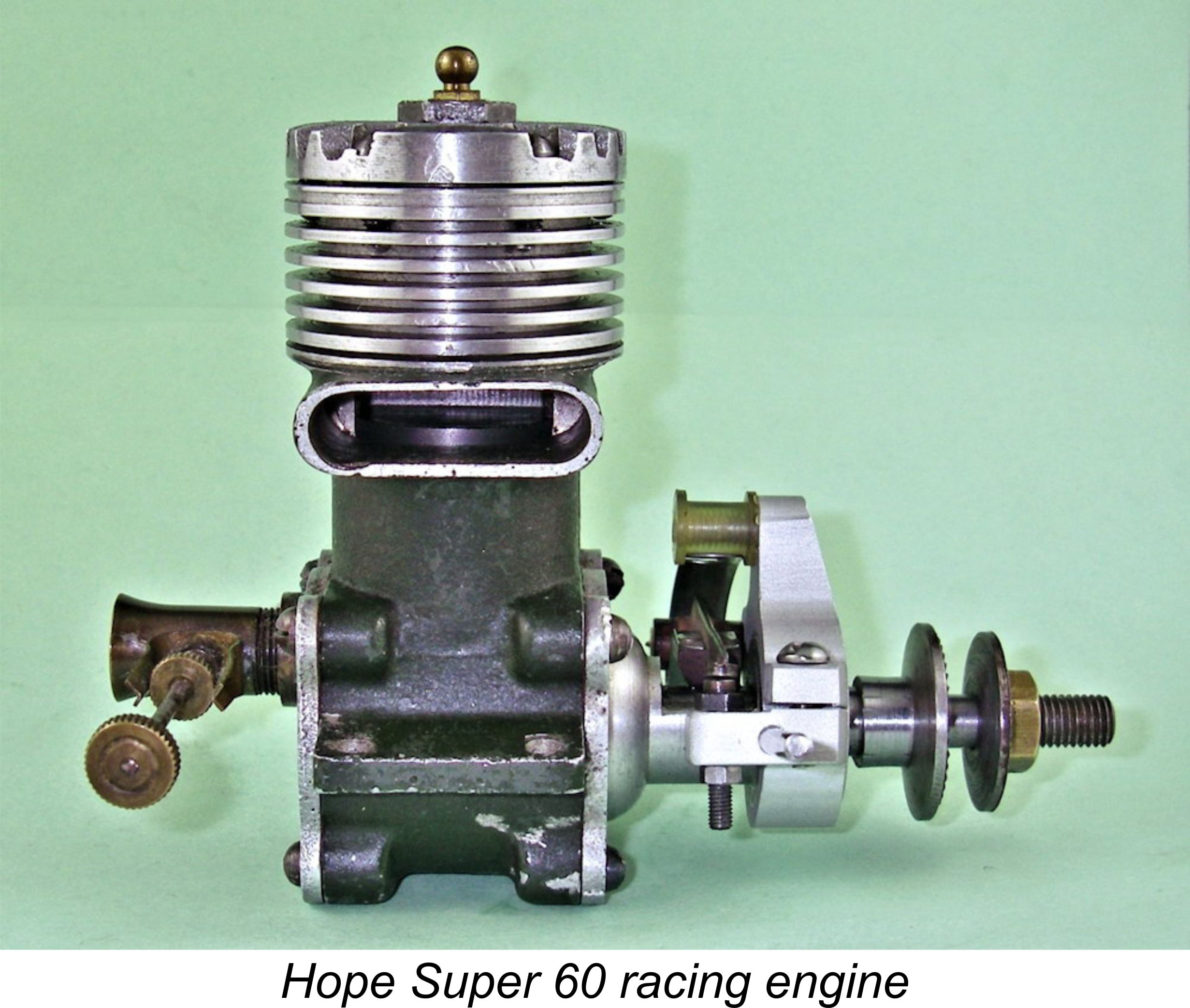

The business of Kondo Kagaku Co. Ltd. was well-established as of 1948 when the brothers appear to have decided to enter the field of model engine manufacture. This gave them several significant advantages over many of their emerging competitors in the model engine field - they had already developed a high level of consumer visibility along with a wide range of useful contacts within the industry; they had a thriving business line to fall back on if their model engine venture failed; and they had well-established production facilities along with some accumulated capital upon which to draw to set up their new product line. Given the above background, it should come as no surprise to learn that one of the early KO creations was a 10 cc (.60 cuin.) racing engine which was clearly designed specifically for control line speed flying. Let’s begin by taking a necessarily brief look at this engine………. The KO 60 Racing Engine

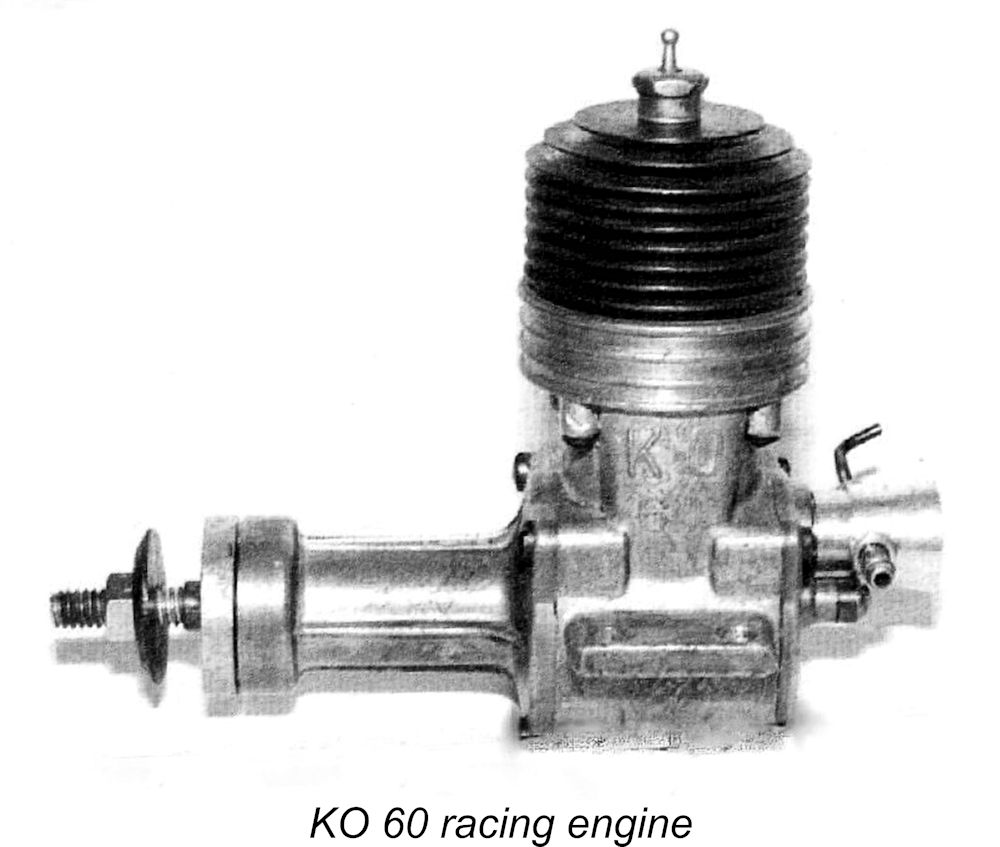

Fortunately, this image places me in a position to offer a few comments. The KO 60 featured the usual contemporary “racing” mixture of twin ball-races, bolt-on front and rear covers, disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction and cross-flow loop scavenging, although it was more or less unique among large racing engines in using a blind-bored cylinder with integral cooling fins. If it followed the design of its contemporary companions in the range, as seems likely, it would also have used a lapped cast-iron piston, a feature which was shared by several other Japanese racing engines of the period. It’s apparent from the illustration that the KO 60 used die-cast components throughout. Viewed in a Western context, this would normally be taken to indicate that the engine was intended for series production. However, this is not necessarily the case in a Japanese context. Japanese manufacturers were extremely comfortable with die-casting by this time, having employed the technology quite widely even before WW2. The scale of production was of lesser importance to them - what counted was their perception that die-casting was a logical method of producing high-quality castings, particularly those with some intricacy involved. This being the case, the technique was widely used by Japanese manufacturers at all scales of production. Accordingly, the use of die-casting provides no secure evidence regarding the scale of production of a given Japanese engine. Nonetheless, the scarcity of surviving examples of the KO 60 even in Japan seems to imply that it was never manufactured in significant quantities. It may in fact have been more of a “manufacturer’s statement” than anything else. It must surely have a strong claim to being the Holy Grail for collectors of early post-war Japanese racing engines! Rather remarkably, my valued Aussie friend and colleague Gordon Beeby found a reference to this engine in the "Scrap Box" feature in the October 1951 issue of "Model Airplane News" (MAN). Writer Jim Saftig had received a report from Toshihisa Watanabe which included the information that KO manufacturer Kanejiro (Jiro) Kondo had used a KO 60 to win the 10 cc control line speed class at the fourth All Japan Model Airplane Contest held in 1951 at the former Matsudo aerodrome. Kondo's winning speed was a quite respectable 133.33 MPH. While not a world-beating performance by then-current American standards, this speed would have given Kondo first place at the 1951 Knokke international contest in Europe. It's clear that the KO 60 was a stouter performer than its somewhat retrograde design might lead us to expect! Marketing Considerations The interest of the Kondo brothers was clearly not confined to the racing engine sphere - they intended to join their contemporaries who were trying to develop a viable business out of model engine manufacture. Mass sales of their .60 cuin. racing engine could scarcely have been a realistic expectation - rather, that model was probably intended to do no more than draw attention to their technical capabilities. To establish their new model engine line on a solid economic footing, they would have to offer engines which might be expected to sell in quantity at an economically rational price. This in turn required the development of designs which were tailored to the consumer market as it then existed, both in terms of technical specification and displacement. The Kondo brothers proceeded to do just this, developing general-purpose engines in several of the more popular displacement classes under the KO trade-name.

American service personnel had far greater discretionary spending power than the average Japanese citizen at the time. In addition, they could pay in US dollars instead of the greatly devalued Japanese currency of the day. Hence they represented a very real opportunity for Japanese manufacturers in many fields to get a head start in the competitive post-war consumer-based Japanese economy which was fast taking shape. Basically, these service personnel assured such manufacturers of a ready and lucrative market for any consumer goods which were surplus to domestic requirements. In fact, at this point in time there was little incentive for Japanese manufacturers to make strenuous efforts to export their products to the American market - that market had in effect come to them! The reverse of the usual pattern, in fact ............. A number of strategies were employed to present Japanese products in a way that would commend itself to potential buyers from overseas. One such strategy was the widespread application of Anglicised names to the products in question. Many of the names applied to post-war Japanese engines certainly reflect this trend, as does the more or less universal abandonment of Japanese ciphers on the engines themselves. Another strategy that might logically be expected to have had some attraction was the adoption of American design architecture for Japanese engines in order to give them a comfortable air of “familiarity” to overseas buyers. An important consideration in this regard was doubtless the fact that American goods at the time were (often quite unjustifiably) seen by the Japanese public as somehow superior to their Japanese equivalents. Hence an “American” appearance might be expected to have its attractions for domestic consumers also. However, this particular strategy was rarely pursued by Japanese manufacturers during the early post-war period. The Kondo brothers were noteworthy exceptions to this general statement, clearly seeing some value in pursuing an American-influenced architectural strategy. There’s no question that their early KO engines bore a striking and surely more than coincidental resemblance to several contemporary American designs. To illustrate this point, I can do no better than present the first of the models to be discussed in detail in this article - the KO 29. The KO 29 - The Japanese OK

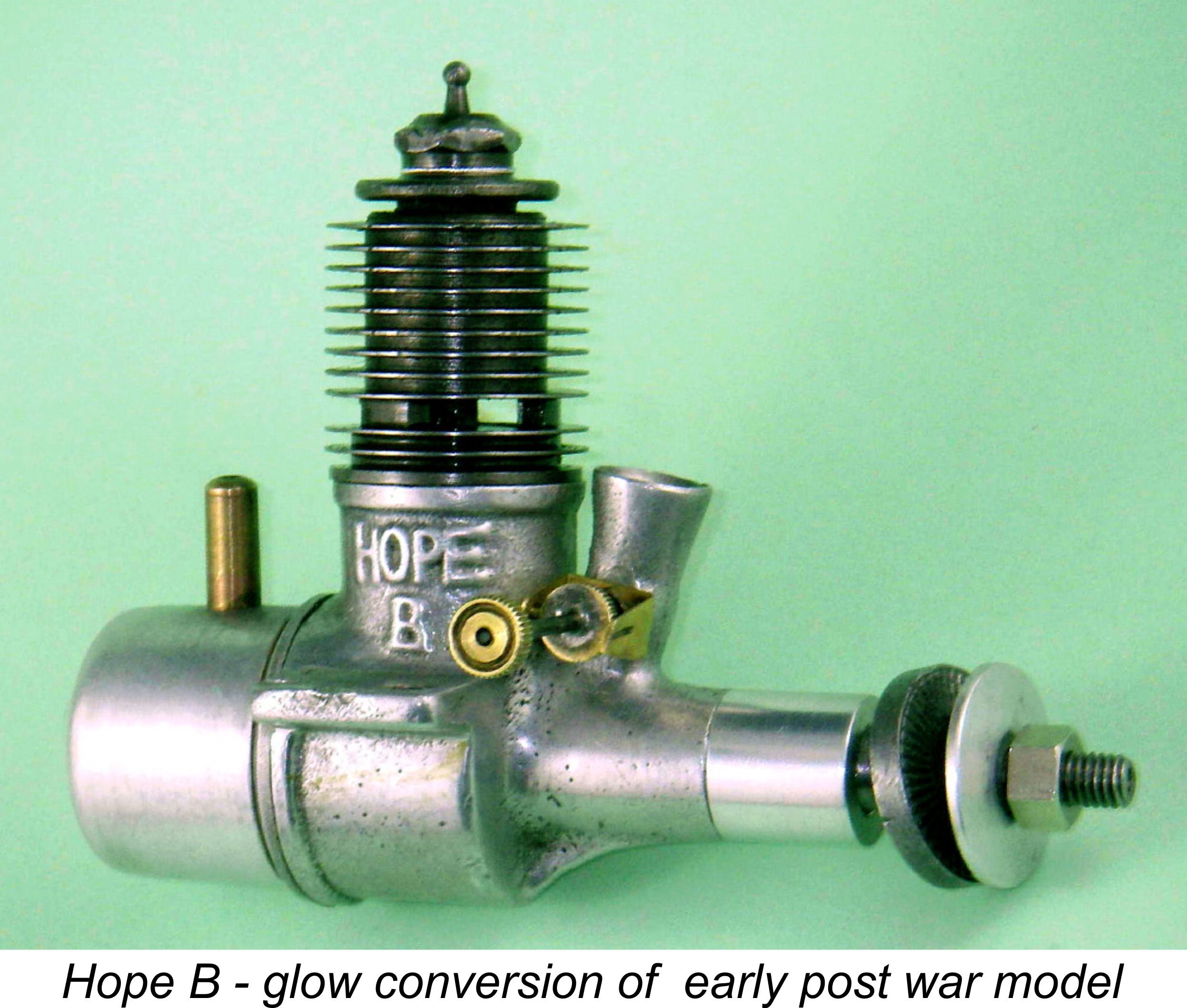

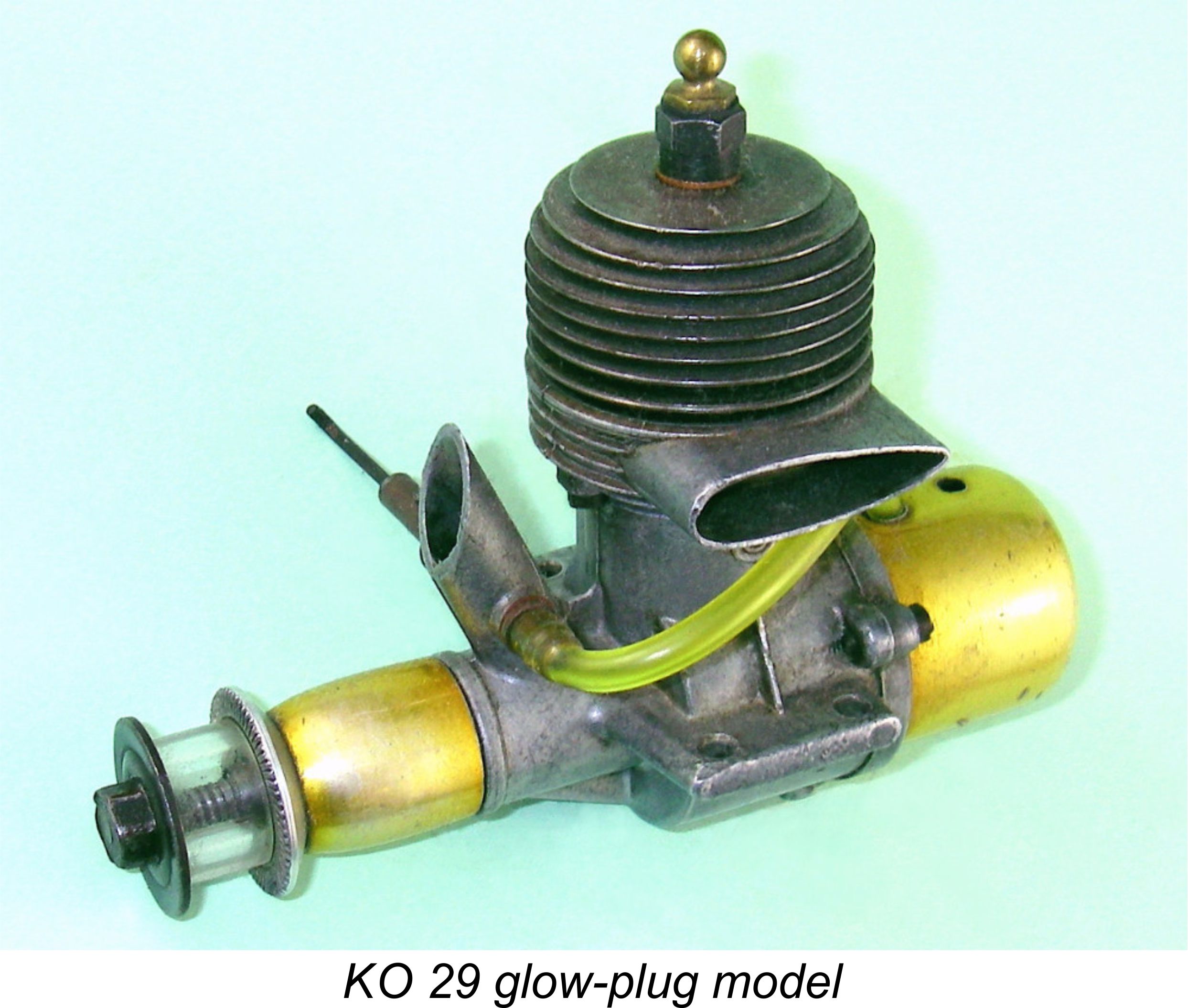

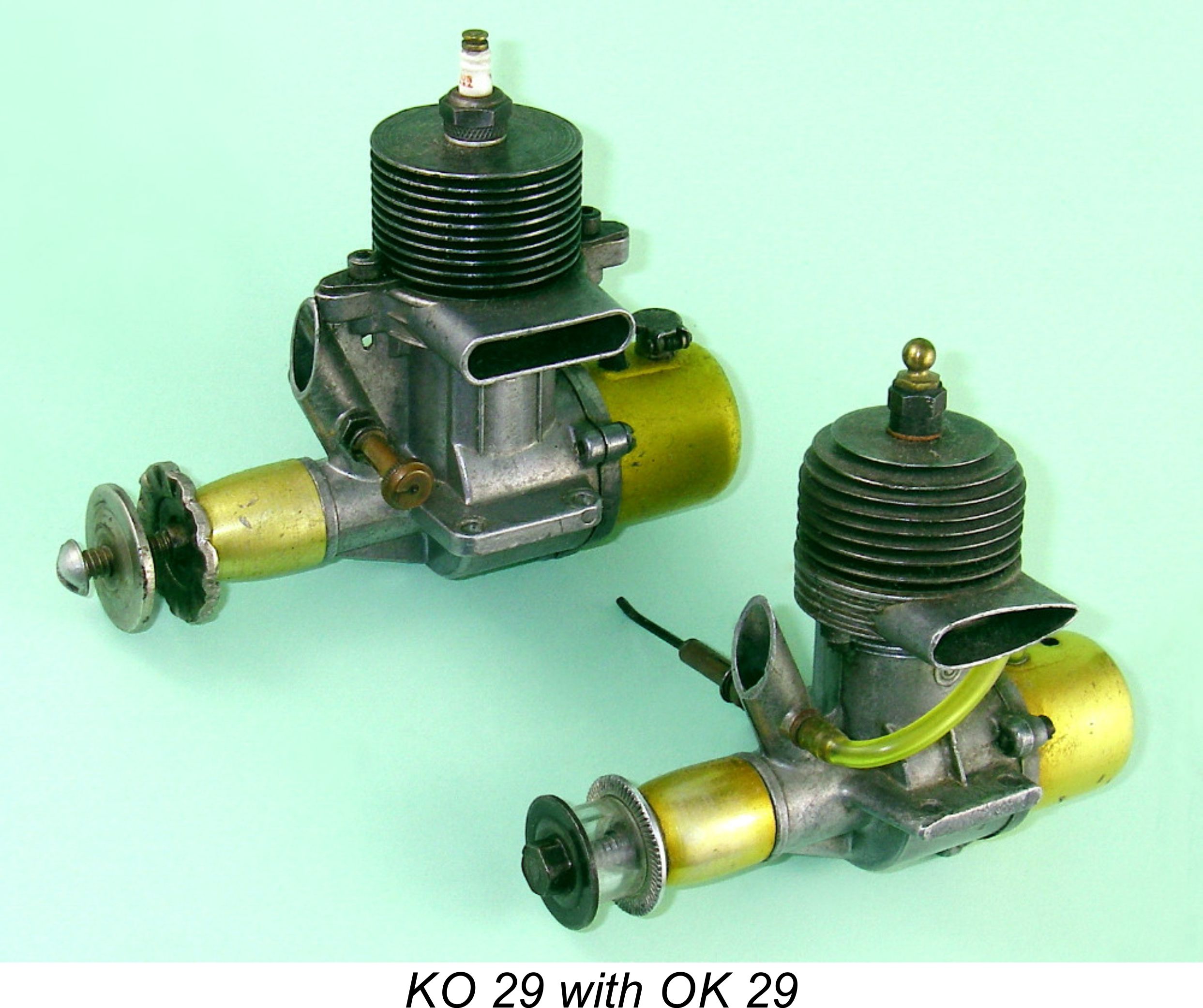

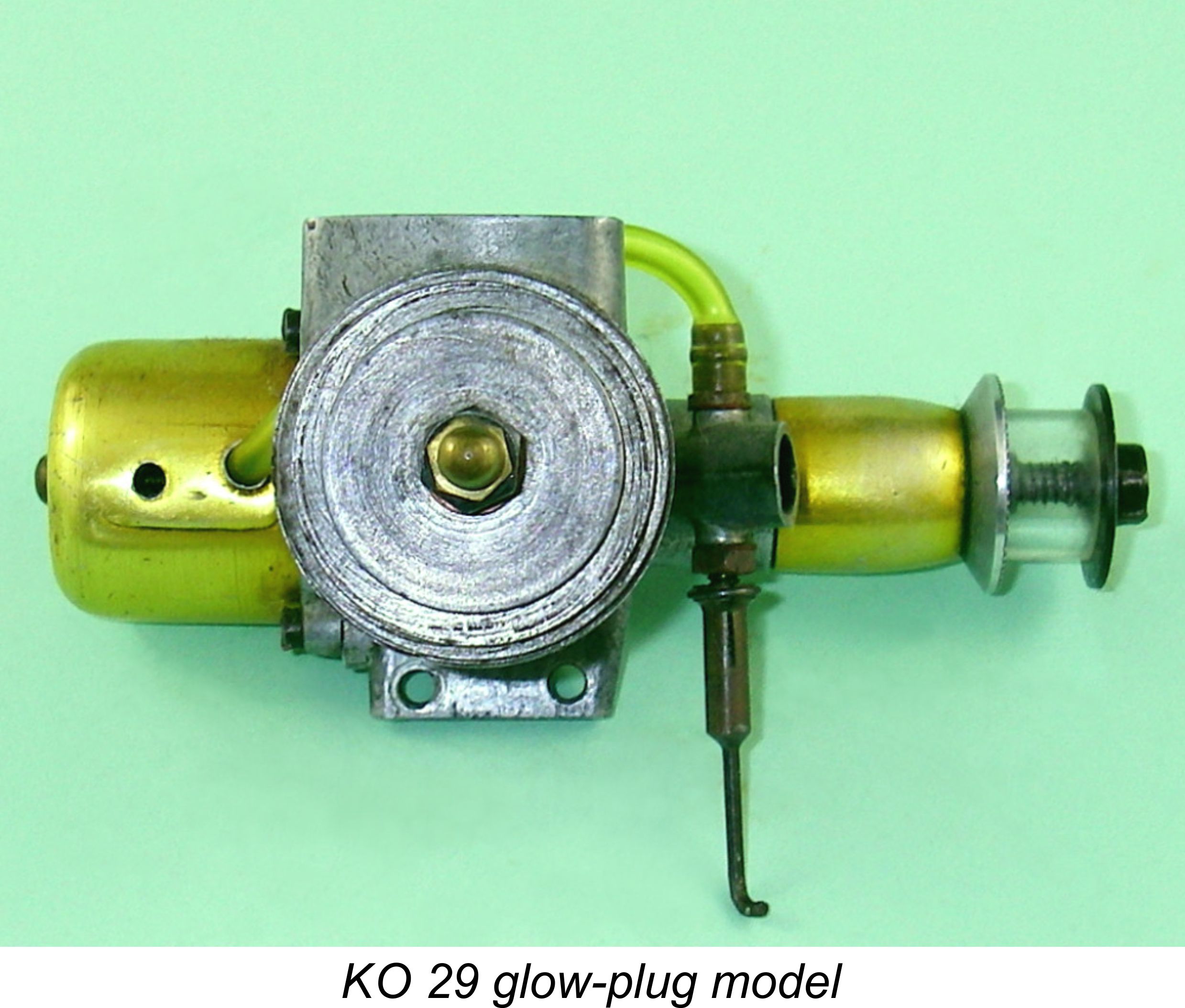

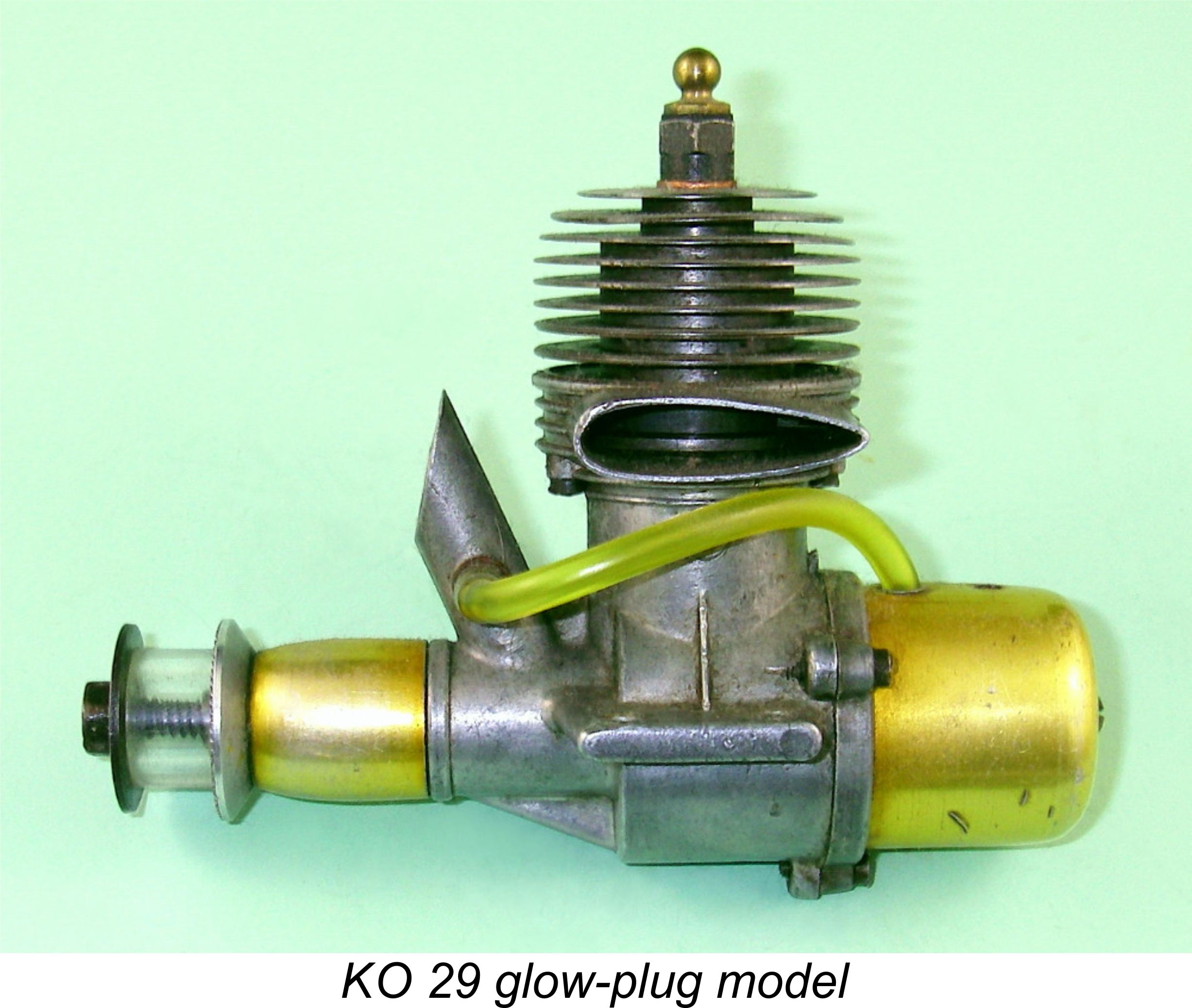

I'm extremely fortunate in being able to describe this engine in detail thanks to having a very fine original example of the glow-plug model on hand. This is actually the only example of this relatively rare engine that I’ve personally ever encountered in the metal. On first seeing this motor at arm’s length, one’s immediate thought is that it must be a hitherto-undocumented or owner-modified version of the well-known OK 29 from America! It’s only when you look closely enough to read the identification on the side of the crankcase that you learn that the letters of its At first sight it would appear logical to assume that the KO 29 was intended to be manufactured in quantity, since all castings were produced by the die-casting process. The creation of the necessary dies would have added considerably to the required start-up investment. As noted earlier, the previous success of the company in other manufacturing fields would have done much to generate the necessary capital. However, it’s important to remember the earlier comment that die-casting was used by Japanese manufacturers at a wide range of production scales. A side-by-side comparison of the KO 29 with a 1950 Mohawk Chief or its almost identical 1948 OK Hothead predecessor from the early post-war period soon clarifies both the points of direct similarity (of which there are many) as well as the differences that give the KO engine its own distinct personality. Although there are a fair number of such differences, they are mostly in the details. Hence an objective comparison leaves one in no doubt that the degree of design similarity between the two cannot be entirely coincidental.

When coupled with the apparent absence of any opportunity for OK designer Charles Brebeck Sr. to become familiar with Japanese model engine designs prior to 1946, this makes it appear almost certain that this was a case of the Kondo brothers being influenced by an existing OK design rather than the other way round. As active competitors themselves, they would doubtless have had ample opportunity to examine such engines in the hands of American modellers stationed in Japan.

Both engines use a flat-topped lapped cast iron piston with a cut-away milled into the crown on the transfer side in lieu of an upstanding baffle. The transfer port is set further down the cylinder wall to maintain a reasonable blow-down period, allowing the piston cut-away to act in the same manner as an upstanding baffle by directing incoming transfer gas upwards towards the top of the cylinder bore. The resulting combustion chamber shape at top dead centre is less than ideal due to the creation of a pocket of mixture In both designs, the exhaust stack is located on the left-hand side of the engine (looking forward in the direction of flight) with the single bypass passage on the opposite (right hand) side. The main bearing housing in both motors is cast integral with the crankcase, being equipped with a bronze bushing. Crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction is employed in both cases, with a relatively tall forward-raked intake venturi having its open end chamfered at a sharp forward angle to catch the slipstream to best advantage. The engine bearers are located with their mounting surfaces on the axial centre line of the crankshaft in both instances. The same basic needle valve design is used on both models, while the three-screw backplates and gold-anodized back tanks are very similar indeed. Even the gold-anodized thimble which covers the timer location f This being the case, it’s worth digressing for a moment to dispel the widely-held fallacy that Japanese model engine designers were merely talented imitators who got off to such a quick start following WW2 by basically copying the designs of others. The truth is that the degree of direct American design influence exhibited in the KO 29 was actually highly unusual among Japanese model engine designers at the time in question. The reader is reminded of my earlier comment regarding the extent to which model engine design and manufacture had progressed in Japan prior to the outbreak of WW2 (in December 1941 as far as Japan was concerned). This movement had developed more or less independently from any significant influence from America or elsewhere, the result being the evolution of an identifiable Japanese “house style” in which the emphasis was very much on function rather than form. Consequently, the majority of Japanese engines from the pre-war and early post-war periods differed quite markedly from their American contemporaries in that they reflected a minimalist design philosophy under which mechanical objects such as engines were designed strictly to do their job, with no features included beyond those required to achieve that goal. The resulting engines were quite distinct in character from their American counterparts, which generally incorporated considerations of both function and styling into their designs while also tending to be more heavily engineered. The point here is that the early KO engines stand apart from the general run of Japanese model engines of the period in terms of the degree to which they openly display design influence from across the Pacific Ocean. There seems to be little doubt that this was a conscious decision on the part of the Kondo brothers, the logical conclusion being that they adopted this approach quite deliberately in order to add an “International” cachet to their products, thus notionally increasing their attractiveness to the “imported” American market. The really interesting thing is that they were almost alone in taking this approach, at least at the time in question. In summary, there seems to be little doubt that the design of the KO 29 was strongly influenced by that of the contemporary OK 29 model and that the resulting similarities were adopted quite consciously for the reasons stated above. No doubt the Kondo brothers would have had ample opportunity to examine representative examples of the OK engines in the hands of American modellers, possibly even being able to acquire one themselves through trading or modelling contacts.

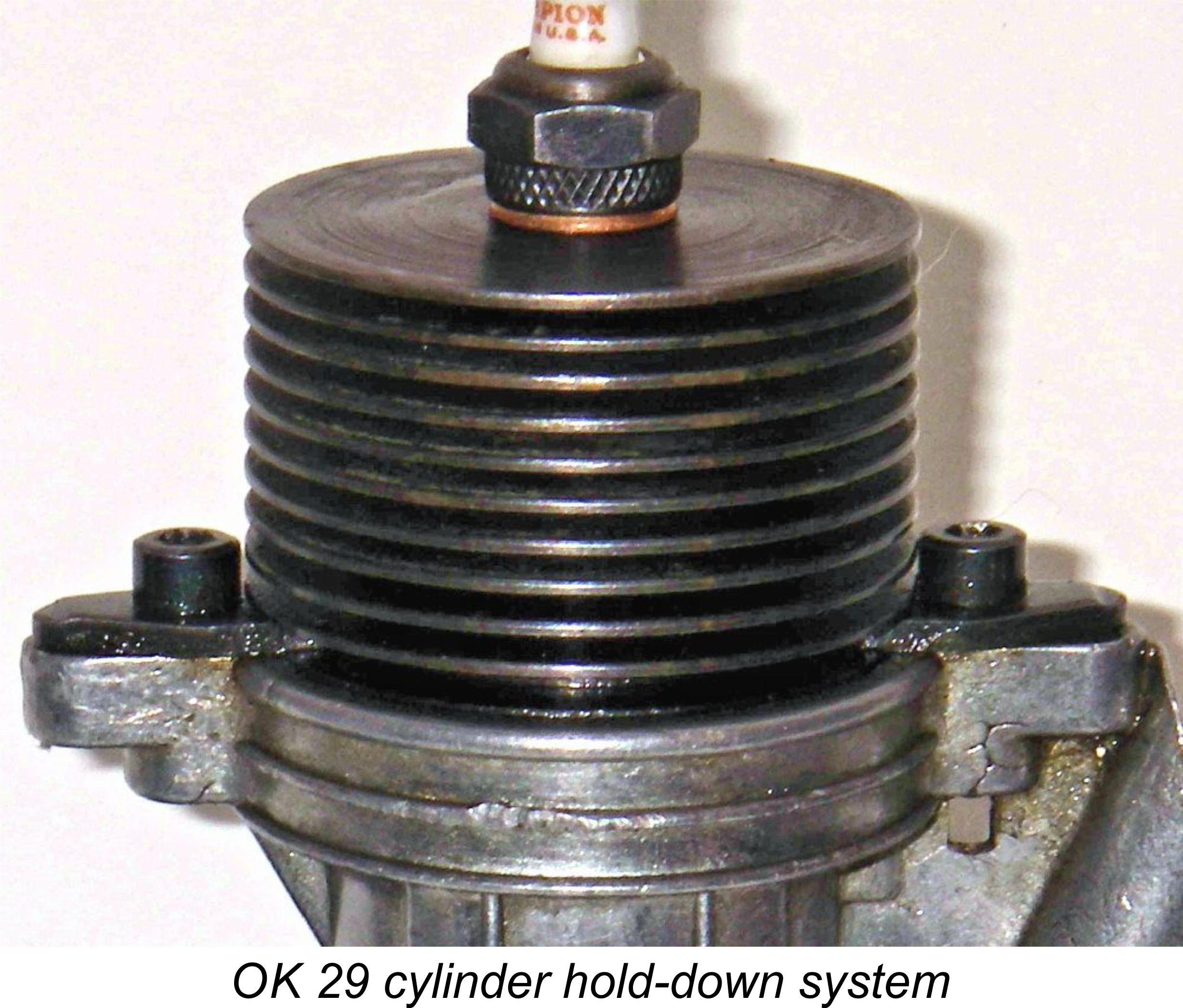

The most immediately obvious departures are the differing profiles of the cooling fins and exhaust stacks. The fins on the OK are of equal diameter, while those of the KO are progressively reduced in diameter at the top, giving the engine a rather attractive “beehive” look which mirrors the similar profile given to the cooling fins on the KO 61 model noted earlier. The exhaust stack on the OK is more or less rectangular, while that on the KO has a streamlined aerofoil section. Overall, it must be said that the styling of the KO’s cylinder down to port level is considerably more visually elegant than that of the OK. Of course, both of these differences are purely cosmetic. The first real departure in the engineering design of the two motors is to be found in the cylinder hold-down system. As noted previously, the cylinders In my earlier article on the OK Cub diesels, still to be found on the MEN site, I noted that OK designer Charles Brebeck Sr. was very much concerned with the reduction of shock loadings on the working components arising from ignition of the fuel mixture at (or slightly before) top dead centre. In his original .29 cuin spark ignition and glow-plug designs, he dealt with this concern by arranging for the cylinders to be held down by what amounted to a pair of spring steel clamps which were attached to the crankcase casting by screws in the fore and aft locations. When the screws were tightened, these clamps bore at their inner ends against a flange at the base of the cylinder, thus holding it down. A thick and rather soft gasket was used beneath this flange, building a measure of “give” into the hold-down system. When the mixture fired in the combustion chamber just before top dead centre, the cylinder was free to rise microscopically against the hold-down clamps, thus absorbing some of the developing energy in the system at a time when that energy could not yet be used to drive the piston. This energy was not lost - rather, it was stored in the strained hold-down system as opposed to the more usual fate of being stored through straining of the main working components. As the piston commenced its power stroke and the shock loading condition passed, the system returned to its normal state, releasing its absorbed energy back into the power train in the process. Brebeck was clearly a true believer in the effectiveness of this system, applying a basically similar “shock absorber” principle to his OK Cub diesel models of the 1950’s. However, it would appear that the Kondo brothers either disagreed with Brebeck’s theories regarding internal stress management or failed to appreciate the reasons for the highly individualistic system seen on the OK .29 models. It would be fascinating to know which ……………………

It must be admitted that this configuration made getting a screwdriver onto the hold-down screws rather more of a chore than it would otherwise be - Allen head screws would have been far easier to manage! However, it is very neat and unobtrusive, contributing to the cleaner and more elegant lines of the KO product by comparison with its OK counterpart. It’s worth noting that the previously-mentioned KO 61 racing engine used four screws deployed from below in a similar manner. In engineering terms, this system achieved one objective of the OK set-up - it eliminated hold-down stresses in the cylinder walls along with the consequent potential for distortion of the bore. However, it incorporated no provision for the absorption of stress generated during the ignition sequence at top dead centre. My own view of the matter is that the Kondo brothers probably understood the thinking behind the Brebeck system perfectly well but did not see any practical advantages in its use. After all, model engines had been built for years without such provisions, and most of them held up perfectly well in service! In my considered opinion, this was almost certainly a case of the designers reverting to the prevailing Japanese design philosophy that if a feature did not contribute materially to the functioning of the engine, it was considered redundant and could therefore be dispensed with. The other engineering design feature which was changed was the method of locking the prop driver to the front of the crankshaft. The OK engines used a relatively thin stamped steel prop driver with a singe flat formed at one point in the circumference of the central hole. This engaged with a flat milled into the end of the crankshaft, securing the driver in a fixed annular relationship to the shaft. The problem with this set-up was that over time the single flat in the driver tended to wear during starting or during crash impacts, allowing the driver to develop an annular “wobble”. It was not uncommon for the flat to strip completely over time, eliminating the required locking action. The driver on the illustrated well-used example of the OK is well on its way .......... The Kondo brothers clearly recognized this problem, hence adopting a different approach in their own model. This took the form of a relatively thick alloy prop driver with a square central aperture which engaged with a square “box” section of shaft milled into it at the front. This system is far less prone to wear and eventual stripping than the single flat system, since there are four locking surfaces rather than one. The greater depth of the flats also reduces the tendency of the system to wear over time. I would have to rate the KO design as considerably superior to that used by OK. One rather odd point which must be mentioned here is the very coarse thread used for the KO’s prop mounting bolt. I elected to make a new bolt for testing purposes to save wear and tear on the original, which looked a bit “experienced”. After unsuccessfully trying everything I knew in the way of metric measurements, I eventually resorted to Imperial measurements. To my complete surprise, the thread proved to be a very British 3/16-24 Whitworth! There’s no doubt at all about this - a tap of that size fits perfectly in the female thread inside the shaft, and the corresponding die is a very close fit on the bolt. My new bolt made with that die is a perfect match. The use of this very un-Japanese thread is one of the real mysteries associated with this engine. It presumably reflects the fact that both tools and materials were in very short supply in early post-war Japan. Manufacturers were forced to improvise, using whatever tools and materials they could scrounge. Japan had of course been an active ally of Great Britain during WW1, besides which British engineering had played a major role in the development of Japanese transportation infrastructure during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. There had thus been ample opportunity for British-specification tools to find their way into the Japanese workplace. Returning to our KO versus OK comparison, the two engineering design changes discussed so far indicate that although they were definitely “copying” an existing American design, the Kondo brothers were by no means doing so slavishly. Whenever they found a feature that was either redundant (in their view anyway) or failed to meet what they considered to be the required engineering standard, they changed it. It’s actually a tribute to the original design by Charles Brebeck that they found so little to change!! Overall, it would appear that the objective of the Kondo brothers in designing this engine was to produce a unit which retained the OK “look” that might hold out some inducement to many of their potential customers, while dealing with what they saw as a few design redundancies or shortcomings. At the same time, they took some steps to improve the aesthetic appeal of the engine. The balance of the changes to be documented here all fall into the latter category and may be dealt with very quickly.

The web which appears on the OK between the intake venturi and the main crankcase is absent on the KO. This omission was forced upon the KO designer by the need to allow access to the front cylinder hold-down screw. The web would in fact contribute to the ability of the intake to withstand a crash impact and would likely have been included if the screw arrangement had permitted this. However, the absence of the web once again represents an asset in terms of the overall visual elegance of the KO design.

So much for what can be seen on the outside. I haven’t ventured to disturb my example of the KO 29 since a tentative probing has revealed that both the seals have become “permanent” with age and use and would have to be broken, likely with damage to the sealing gaskets. In any case, the engine is in perfect running condition and does not appear to require any internal servicing. Dismantling might reveal further departures from the OK design, but for now the above description will have to suffice. Which leads us to the “tale of the tape”! Here’s how they measure up:

These figures provide further evidence of independent thinking on the part of the KO designers. They clearly wanted to improve the torque potential of their engine by lengthening the stroke, reducing the bore as necessary. More significantly, they built their model right up to the 5 cc limit allowed by the Japanese equivalent of Class B (and also in effect in Europe). The OK engine would of course be eligible for that class, but the KO had the very slightly larger displacement and longer stroke which could give it an edge against any OK opposition which might appear in Japanese contests. It’s an entirely rational assumption that making a good showing against American opposition in Japanese contests would be seen at the time by Japanese engine manufacturers as an important goal for a variety of reasons. This observation is extremely illuminating in one other respect. It indicates pretty conclusively that the Kondo brothers were not looking at export sales to the USA, at least at the time in question. They must surely have known that they were producing an engine that would be eligible for Japanese contests but would exceed the American Class B regulations. This would only become an issue if the engine were to be marketed in the USA, the clear inference being that the designers had no such expectations at this early stage of the company’s existence. If export sales had come into the picture at a later date, it would have been a simple matter to reduce the bore from 19.20 mm to 19.05 mm to yield an American-legal displacement of 4.90 cc (0.299 cuin). The net result of all of the above machinations was the production of a somewhat more elegant but still clearly identifiable OK spin-off. If one had to pick the more aesthetically pleasing of the two, most people would undoubtedly pick the KO. Moreover, the quality of construction is first class - despite the fact that the illustrated example has clearly seen a fair bit of use, all fits remain excellent. In terms of quality, the KO will easily withstand comparison with its OK progenitor. Fair enough, but how do the two designs compare in performance terms? That’s a question that I will have to answer at some point in the future when more time becomes available. For now, I can only say that an obejctive review of the functional designs of the two models leads me to expect very similar levels of performance from both, with perhaps the edge going to the KO in terms of torque development. The KO 19 - The Japanese O&R

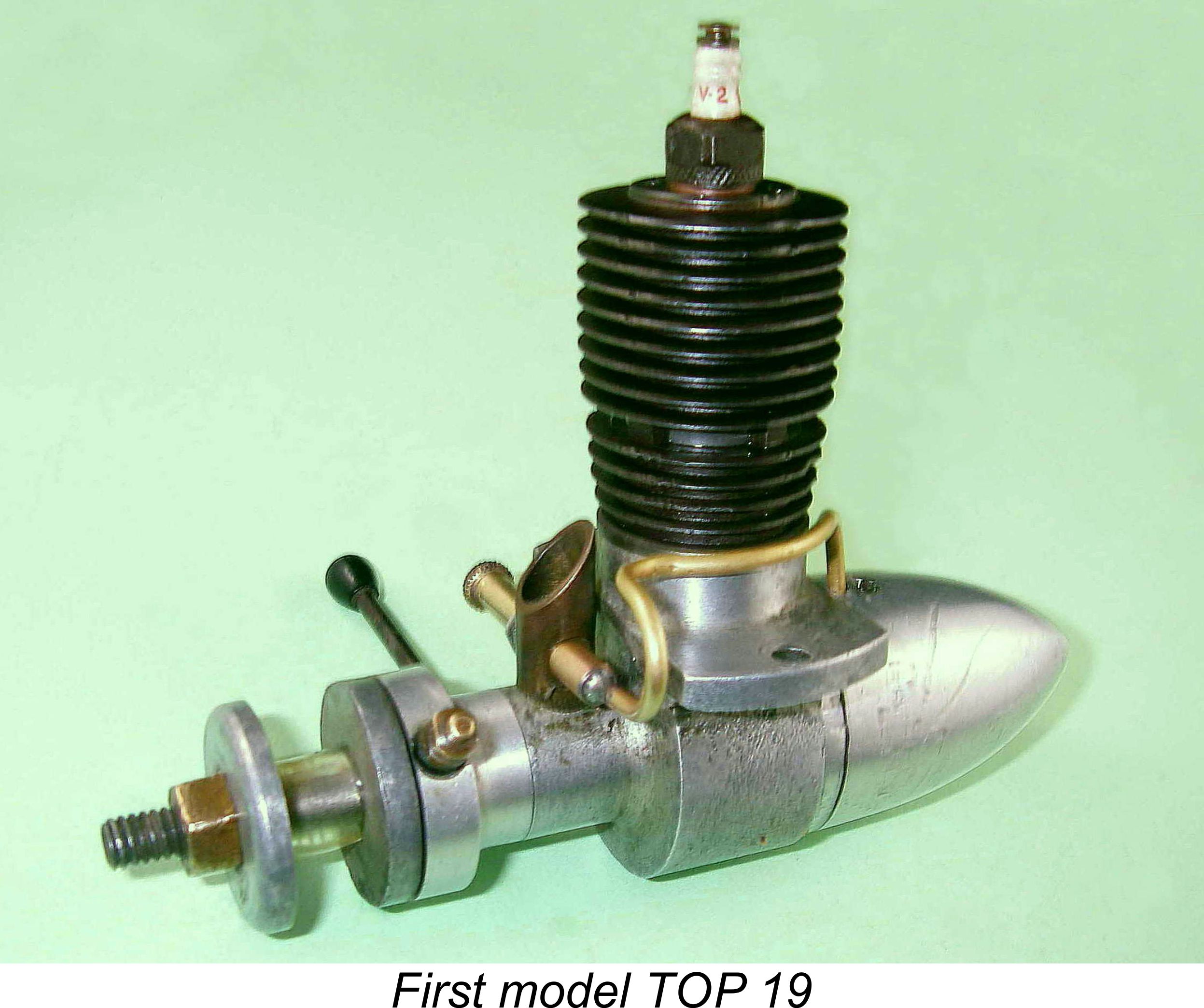

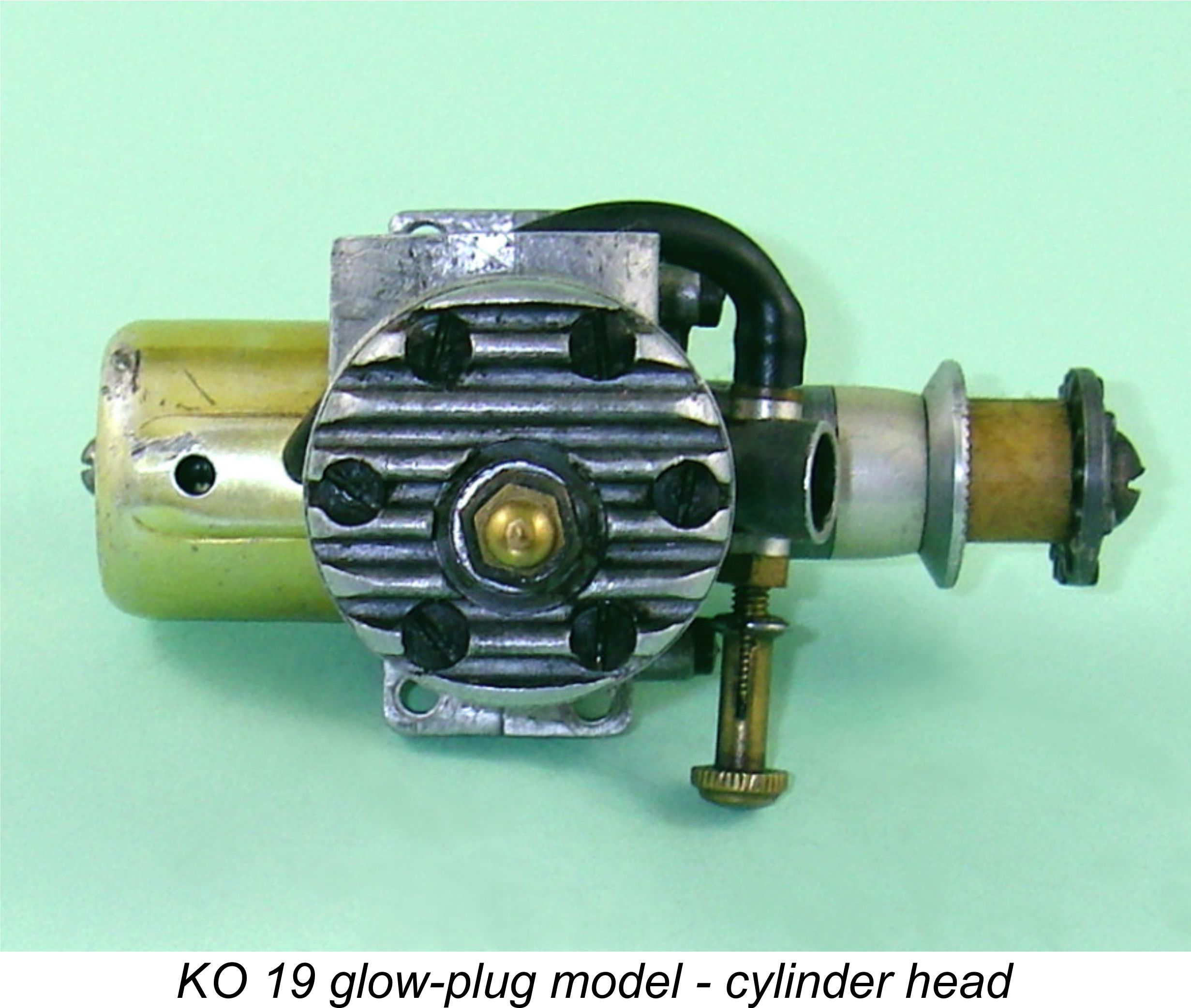

Given the fledgling state of the Kondo brothers’ engine production business at this time as well as the marked design differences between the two models, it seems unlikely that the KO .29 and .19 designs were developed concurrently - resource considerations would appear to argue against that scenario. The evidence to be discussed below suggests that the design of the .19 model was developed immediately following that of the .29 described earlier. There are certainly a number of similarities which keep the styling of the smaller engine within the early post-war KO “family”. However, there is also evidence of some progress in the designers’ understanding of certain aspects of model engine design, especially in relation to the issue of efficient combustion. It is this factor which seems to suggest that the design of the KO .19 was most likely developed after that of the .29 and .61 models, probably in late 1948 or even early 1949. However, I freely acknowledge that this is very far from certain at the present time.

This left them with two choices - they could either produce a scaled-down version of the larger KO model, or they could find a different American .19 cuin. model to take as their starting point. As it happened, just such a model was in existence at the time in question. This was the very popular O&R .19, which had been re-introduced in its pre-war sideport spark ignition form in 1946 and refined into an FRV version in late 1948 in both spark and glow plug versions, having been preceded by an FRV version of the very similar .23 cuin. model in June 1948.

But it didn’t stop there! As in the case of the .29 cuin. model, the designers were not content merely to imitate. Instead, they re-evaluated the entire O&R design, making changes as they saw fit on the basis of their own evaluation. Moreover, by this time their understanding of certain aspects of model engine design had clearly evolved. The resulting engine displayed obvious evidence of its O&R design origins but nevertheless embodied a considerable measure of independent thinking - far more so than with the KO .29 model. Once again, the apparent intent to engage in quantity production was underscored by the fact that all of the cast alloy components were produced by die-casting.

The crankcases of the two designs are basically similar too, with the sturdy beam mounting lugs being located well above the axial centre line of the shaft, thus placing the thrust line more or less on the centre of the model's engine bearers. Both crankcases have fins cast into their undersides, presumably to enhance crankcase cooling.

So much for the similarities, which are surely too marked to be coincidental. There seems to be little doubt that the Kondo brothers took the O&R .19 (or .23) FRV model as their design inspiration, thereafter setting out to create their own product which projected a comfortable and familiar O&R influence to potential buyers. But as before, they were not content to merely copy - rather, they took a long hard look at the O&R .19, modifying that design wherever they felt the need to do so. Let’s look at the changes which were made to the basic O&R design. The first important change is to be found at the top of the cylinder. The FRV version of the O&R .19 retained the blind bore which had become a trademark feature of the O&R models, with the addition of a swaged-on alloy cylinder head. However, this head was in fact a dummy - the engine would run perfectly well with the head removed. It may have contributed a little to improved cooling, but did little else apart from significantly enhancing the engine’s appearance. Furthermore, the use of a blind bore made it impossible to machine a really efficient combustion chamber shape into the underside of the head. It’s clear that by this time the Kondo brothers had developed an increasing appreciation of the benefits of a more efficient combustion chamber shape than was possible using a blind bore. Accordingly, they eliminated that feature from their own .19 model, converting the cast alloy cylinder head from what amounted to a cosmetic feature on the O&R into a fully functional head on the KO which sealed the open bore and allowed for the formation of a more efficient combustion chamber shape in the underside. This head was secured to the cylinder by 6 screws.

Of course, the problem of the creation of separate “pockets” of gas on either side of the piston baffle at top dead centre was not entirely eliminated by the use of a separate contoured head arrangement. To get around this, the plug in the KO was located offset towards the transfer side, more or less directly above the baffle. This would theoretically promote simultaneous ignition of the gas in the pockets on both sides of the baffle, hence promoting more rapid complete combustion. The above arrangements reflect a growing appreciation (in medium and larger bore engines, at least) of the benefits of promoting more rapid involvement of the entire charge in the combustion process. It seems that the Kondo brothers were learning on the job, and learning well!

The Kondo brothers decided to eliminate the welds in favour of a return to the system which had obviously served the purpose well in the case of their .29 cuin model previously described. The cylinder of their .19 model was secured exactly as it had been in the .29 model using two screws fore and aft which were inserted from below through two integrally-cast lugs on the crankcase to mate with threaded holes in the lower cylinder flange.

Finally, the KO .19 utilized the same prop mounting system which had been featured in the KO .29, with a square aperture at the centre of the alloy prop driver keying onto a square “box” section milled into the front of the shaft. The prop mounting system was also carried over from the KO .29. Unlike the O&R, which used a conventional prop-nut, the prop on the KO was secured by a bolt (once again using the odd-ball 3/16-24 Whitworth thread) which engaged directly with a tapped hole in the centre of the shaft. A gold-anodized alloy cap was fitted over the former timer mounting boss, exactly as it had been on the KO 29. This was considerably more attractive than the plain steel cap used on the O&R.

Overall, there were enough carried-over features to ensure that the KO .19 retained a recognizable family relationship to its larger companion despite the very different fundamental design influences involved in the creation of the two models. As with the .29 model described earlier, the quality of construction is first class - despite the fact that the illustrated example has clearly done a fair bit of running, all fits remain excellent. The result was a well thought-out variation of the basic O&R design which was in some ways more elegant in appearance and which incorporated a theoretically more efficient combustion chamber together with a somewhat more rational assembly. There may well have been internal departures also, but the documentation of these would require that the engine be dismantled, a step which I elected not to take after some tentative probing. The three seals are well and truly baked on, hence being highly likely to be destroyed during the dismantling process. In addition, the engine remains in excellent running order, hence requiring no internal attention. So that’s about as far as I can go on the basis of an external examination. However, there’s still the “tale of the tape”! Here’s how things shape up in this instance:

Once again, we see that the KO designers were quite prepared to throw away the book when it came to designing the engine to match their own ideas. The difference in the bore and stroke relationships for these two engines having identical displacements is most striking - it’s clear that the Kondo brothers were true believers in the advantages of a longer stroke. They had lengthened the stroke of their companion .29 cuin model by comparison with the OK “original”, and now they went even further by creating a true long-stroke .19 cuin. design, in dramatic contrast to the drastically short-stroke O&R. This provides clear evidence of a concern with torque development as opposed to mere horsepower or the achievement of high revolutions.

Just for fun, I tried the KO .19 at the same session using the same fuel. It certainly ran a little more enthusiastically, getting the 8x4 up to 10,000 RPM, although it too was exhibiting symptoms of under-compression. Both engines clearly needed a splash of nitro to operate at their best. Confirmation of this came from the fact that on 15% nitro the KO got the 8x4 up to a dead smooth 12,400 RPM, while the O&R topped out at 12,000 RPM. On this admittedly limited showing, the KO appears to have a modest performance edge over the O&R. I would expect the KO to develop a little more low-end torque, but the two engines seem to yield generally similar levels of performance. The Next Step - the KO .099 Glow-Plug Model It’s entirely possible and perhaps even likely that there were other models in the early post-war KO range. If so, I have encountered no evidence for their existence, nor have such models been reported to date by my Japanese contacts. I'd be extremely grateful for any information regarding early KO models of which I'm presently unaware. One of the really odd characteristics of the early KO .19, .29 and .61 models is their apparent rarity today, even in Japan. It seems logical to assume that they were intended for volume production, since the company went to the trouble and expense of producing dies for the alloy castings used in all three models, a step which could normally be justified in economic terms solely by significant production figures. But if such figures were actually achieved, where are all those engines now?!? Even my Japanese colleagues don’t seem to know ………

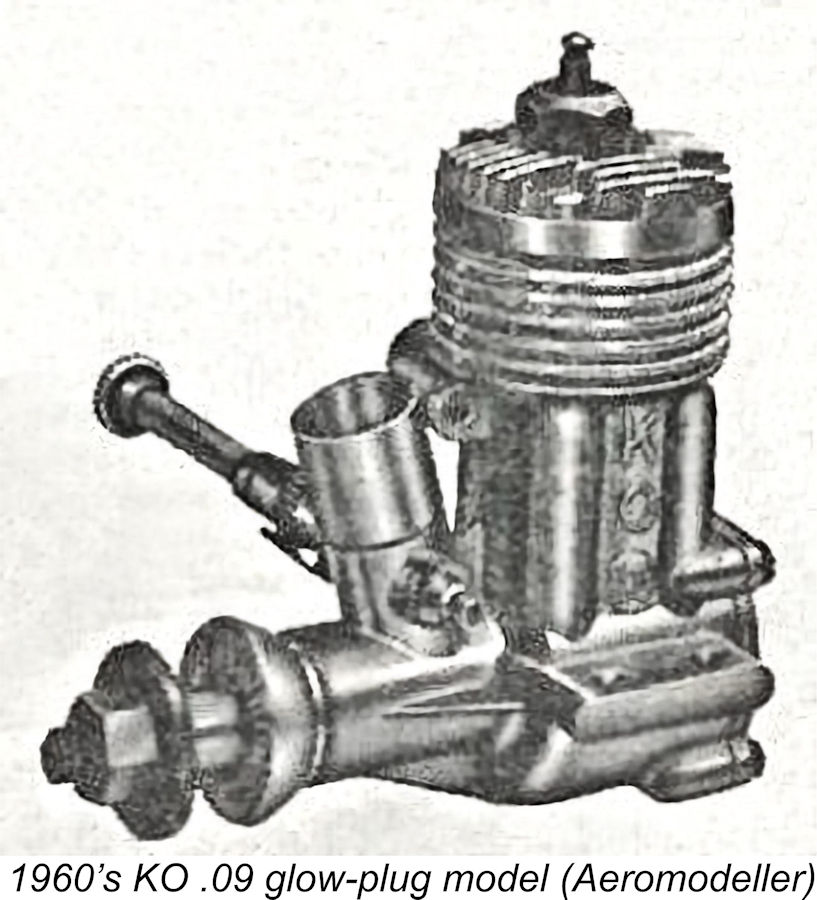

What is certain is that by 1952 the above models had all disappeared from view. Instead, the Kondo brothers had turned their attention to the far more modest yet practical goal of producing a simple and inexpensive twin-stack .099 cuin glowplug model. They had also entered the Ready-to-Fly (RTF) business.

There's irrefutable evidence to confirm that the KO .099 glow-plug model was in production by 1952. This evidence takes the form of a simple RTF control-line model powered by a KO .099 which was purchased new in Tokyo in 1952 by the father of my valued Danish friend Luis Petersen. Luis flew this model himself in 1960, and it still hangs on the wall of his hobby room. He recalled that the recommended fuel contained nitrobenzene, which is now known to be a powerful carcinogen.

Although a detailed description of this neat little unit is beyond the scope of the present article, one comment which may appear relevant is the fact that it too was a long-stroke engine. It featured bore and stroke dimensions of 12.60 mm and 13.10 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.63 cc (.099 cuin). Clearly the Kondo brothers had retained their belief in the benefits of longer strokes to generate improved torque! The little KO .099 glow-plug motor was undoubtedly a commercial success. Examples of this engine are encountered relatively frequently today - far more so than the earlier KO engines described above. Moreover, additional KO models were not long in appearing, notably the range of diesels for which the company was to become well-known. The Later Years

The KO model engine range continued in production well into the 1960's with a series of well-made diesels in different displacements as well as several additional glow-plug models. One of the latter offerings was an updated .09 model which was offered in both unthrottled and R/C configurations. This unit was mentioned in Peter Chinn's "Latest Engine News" feature in the December 1966 issue of "Aeromodeller".

By the mid-1960’s the model engine manufacturing activities of Kondo Kagaku Co. Ltd. had evidently come to constitute a relatively small proportion of the company’s overall business. It was likely for this reason that in 1965 or thereabouts the engine manufacturing operations were separated from the ongoing R/C production through the establishment of a separate company under the name of the Kondo Model Co. Ltd. In all probability, this was an accountant-driven decision since it established the model engine and R/C manufacturing lines as separate profit centres, to stand or fall on their own. Accountants love that sort of thing!!

Little more was heard of the Kondo model engine range thereafter - indeed, there’s currently no persuasive evidence that engine production continued into the 1970’s. However, the Kondo Kagaku Co. Ltd. went from strength to strength on the basis of its KO PROPO line of R/C equipment, still under the original family ownership. The company was among the first to sense the upsurge of interest in R/C model cars which began in the early 1980’s, resulting in a 1988 decision to concentrate exclusively on the R/C model car field.

But all of this constitutes another story to be written by others! For now, I hope that you’ve enjoyed this in-depth look at a few of the less common Japanese glow-plug engines from the early post-war period. _________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2014 Updated August 2023

|

||

| |

It’s amazing what a mere switch-around in the order of two letters can do! Here we look at such a switch which seems to have had the effect of transferring a well-known line of American engines across the Pacific Ocean to a re-birth in Japan!

It’s amazing what a mere switch-around in the order of two letters can do! Here we look at such a switch which seems to have had the effect of transferring a well-known line of American engines across the Pacific Ocean to a re-birth in Japan! In several previous articles about Japanese engines which may be found on Ron Chernich’s “

In several previous articles about Japanese engines which may be found on Ron Chernich’s “

It wasn’t long before these pioneering firms were joined by other would-be Japanese engine manufacturers. Consequently, within a few years of the cessation of hostilities an amazing diversity of model engine production was taking place in Japan. In addition to O.S., other names such as

It wasn’t long before these pioneering firms were joined by other would-be Japanese engine manufacturers. Consequently, within a few years of the cessation of hostilities an amazing diversity of model engine production was taking place in Japan. In addition to O.S., other names such as

The KO model engines were manufactured in Tokyo, Japan. The range was the brainchild of the Kondo brothers, one of whom was named Kanejiro (seemingly generally shortened to Jiro). I have been unable to confirm the name of the other brother. The letters KO apparently stand for Kondo Otoko, an abbreviated Japanese rendition of Kondo Brothers. However, the official company name was registered as Kondo Kagaku Co. Ltd., which translates to Kondo Scientific Co. Ltd. Reports from Japan indicate that Jiro Kondo was the company leader and chief designer of their products.

The KO model engines were manufactured in Tokyo, Japan. The range was the brainchild of the Kondo brothers, one of whom was named Kanejiro (seemingly generally shortened to Jiro). I have been unable to confirm the name of the other brother. The letters KO apparently stand for Kondo Otoko, an abbreviated Japanese rendition of Kondo Brothers. However, the official company name was registered as Kondo Kagaku Co. Ltd., which translates to Kondo Scientific Co. Ltd. Reports from Japan indicate that Jiro Kondo was the company leader and chief designer of their products.  Naturally, the engine is an extremely important element of any control-line speed model. It seems to have been this interest which first led the Kondo brothers to give serious consideration to the engines which they were using. The early post-war Tokyo contests attracted many competitors from among the predominantly American forces of occupation. Consequently, these events must have given the Kondo brothers and their Japanese competitors ample opportunity to examine engines from both domestic and American manufacturers. They appear to have joined other Tokyo manufacturers such as

Naturally, the engine is an extremely important element of any control-line speed model. It seems to have been this interest which first led the Kondo brothers to give serious consideration to the engines which they were using. The early post-war Tokyo contests attracted many competitors from among the predominantly American forces of occupation. Consequently, these events must have given the Kondo brothers and their Japanese competitors ample opportunity to examine engines from both domestic and American manufacturers. They appear to have joined other Tokyo manufacturers such as  I don’t have access to an example of this extremely elusive engine - indeed, I have never seen an example in the metal. It’s only through the kindness of my English contact Alan Strutt that I’m able to include the attached scanned photograph - the sole image which I presently have available for this ultra-rare model. Apologies for the rather poor quality of this illustration, but the fact that it’s the only one leaves me with little option …………

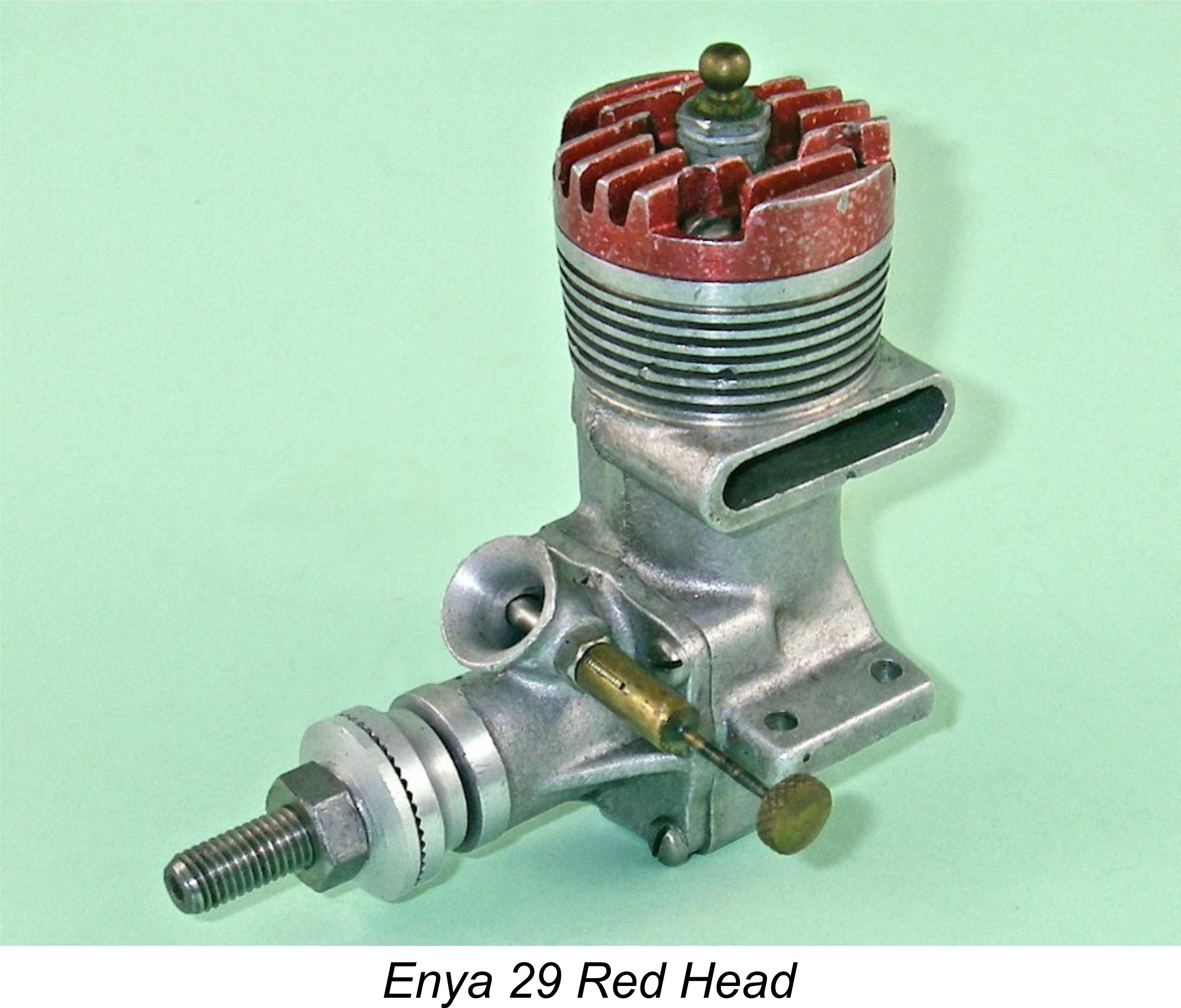

I don’t have access to an example of this extremely elusive engine - indeed, I have never seen an example in the metal. It’s only through the kindness of my English contact Alan Strutt that I’m able to include the attached scanned photograph - the sole image which I presently have available for this ultra-rare model. Apologies for the rather poor quality of this illustration, but the fact that it’s the only one leaves me with little option ………… As mentioned earlier, a major factor driving the post-war explosion of Japanese manufacturing both in the model engine and other fields was the very large market represented by the predominantly American forces of occupation. Every American forces base in Japan had its own hobby shop, and these retail outlets were officially encouraged to offer Japanese-made goods to assist in the economic reconstruction of the country. A number of ex-servicemen of my personal acquaintance recalled patronizing these shops and buying Japanese engines and other modelling goods there - an example is illustrated here. I obtained this Enya 29 Red Head from its original owner - an American ex-serviceman who had bought it new while on service in Japan in the early 1950's.

As mentioned earlier, a major factor driving the post-war explosion of Japanese manufacturing both in the model engine and other fields was the very large market represented by the predominantly American forces of occupation. Every American forces base in Japan had its own hobby shop, and these retail outlets were officially encouraged to offer Japanese-made goods to assist in the economic reconstruction of the country. A number of ex-servicemen of my personal acquaintance recalled patronizing these shops and buying Japanese engines and other modelling goods there - an example is illustrated here. I obtained this Enya 29 Red Head from its original owner - an American ex-serviceman who had bought it new while on service in Japan in the early 1950's.  The somewhat sparse information that is available from Japanese sources indicates that this engine was initially offered for sale in 1948 as a spark-ignition model, being subsequently adapted with little change to glow-plug operation in late 1948 or early 1949 when it had become clear that the future lay with glow-plug ignition. It’s also possible that the spark ignition version was offered for a time concurrently with the glow-plug model as an option.

The somewhat sparse information that is available from Japanese sources indicates that this engine was initially offered for sale in 1948 as a spark-ignition model, being subsequently adapted with little change to glow-plug operation in late 1948 or early 1949 when it had become clear that the future lay with glow-plug ignition. It’s also possible that the spark ignition version was offered for a time concurrently with the glow-plug model as an option.

This leads us to the chicken-and-egg question of who copied whom?!? Viewing the matter objectively, there can be little question that the original design influence came from OK in America rather than the other way round. The basic design of the OK Hothead (OK’s first glow-plug .29 from 1948) originated in 1946 with OK’s first .29 cuin. model, the original B29 spark ignition engine. There’s no evidence whatsoever that the Kondo brothers were involved with model engine production before that date - as noted earlier, their initial preoccupation was with the production of R/C equipment.

This leads us to the chicken-and-egg question of who copied whom?!? Viewing the matter objectively, there can be little question that the original design influence came from OK in America rather than the other way round. The basic design of the OK Hothead (OK’s first glow-plug .29 from 1948) originated in 1946 with OK’s first .29 cuin. model, the original B29 spark ignition engine. There’s no evidence whatsoever that the Kondo brothers were involved with model engine production before that date - as noted earlier, their initial preoccupation was with the production of R/C equipment.  It seems logical to follow up the above statements by listing the points of similarity which give rise to the view that this was a case of direct design influence. Probably the most significant shared feature is the use of a steel cylinder having integrally-turned cooling fins and a blind bore, features which the KO 29 shared with the companion .61 cuin. model described earlier. This cylinder is attached to the crankcase in both KO and OK models by two fasteners located fore and aft at the cylinder base, thus eliminating any hold-down stresses in the working cylinder walls. The two fastening systems are somewhat different (see below), but the basic arrangement is identical.

It seems logical to follow up the above statements by listing the points of similarity which give rise to the view that this was a case of direct design influence. Probably the most significant shared feature is the use of a steel cylinder having integrally-turned cooling fins and a blind bore, features which the KO 29 shared with the companion .61 cuin. model described earlier. This cylinder is attached to the crankcase in both KO and OK models by two fasteners located fore and aft at the cylinder base, thus eliminating any hold-down stresses in the working cylinder walls. The two fastening systems are somewhat different (see below), but the basic arrangement is identical.  located well away from the centrally-positioned plug. This will tend to delay the full involvement of the fresh charge in the combustion process. However, the use of a blind bore more or less precludes the use of an upstanding baffle of any height because of the difficulty in forming the underside of the head into a suitable shape to accommodate the baffle.

located well away from the centrally-positioned plug. This will tend to delay the full involvement of the fresh charge in the combustion process. However, the use of a blind bore more or less precludes the use of an upstanding baffle of any height because of the difficulty in forming the underside of the head into a suitable shape to accommodate the baffle. or the spark-ignition versions is more or less identical in both cases. Finally, the prop mounting system is basically the same, with the front of the shaft being drilled and tapped to accept a prop mounting bolt, along with the prop driver being keyed to the shaft using flats milled into the front of the shaft for that purpose. In fact, so far we seem to be describing two very close relatives indeed!!

or the spark-ignition versions is more or less identical in both cases. Finally, the prop mounting system is basically the same, with the front of the shaft being drilled and tapped to accept a prop mounting bolt, along with the prop driver being keyed to the shaft using flats milled into the front of the shaft for that purpose. In fact, so far we seem to be describing two very close relatives indeed!! However, it would be very surprising indeed if they had not evolved some ideas of their own to contribute to the design of their own product. Let’s now look at the differences which confirm that they were indeed thinking independently even while designing what was clearly intended to be an OK look-alike.

However, it would be very surprising indeed if they had not evolved some ideas of their own to contribute to the design of their own product. Let’s now look at the differences which confirm that they were indeed thinking independently even while designing what was clearly intended to be an OK look-alike. of both engines are held down on the case by two screws arranged fore and aft and acting upon a flange at the base of the cylinder. This is a good system insofar as it relieves the cylinder walls of any hold-down stresses. However, the manner in which the screws are actually deployed is very different on the two models.

of both engines are held down on the case by two screws arranged fore and aft and acting upon a flange at the base of the cylinder. This is a good system insofar as it relieves the cylinder walls of any hold-down stresses. However, the manner in which the screws are actually deployed is very different on the two models. Regardless of the reason, the KO 29 featured a far more conventional cylinder hold-down system using two screws acting directly upon the cylinder. The one unusual aspect of the KO set-up was the fact that the two screws were inserted upwards through two holes drilled in a pair of lugs cast fore and aft into the crankcase for that purpose. The two screws mated with threaded holes in the relatively thick lower cylinder flange.

Regardless of the reason, the KO 29 featured a far more conventional cylinder hold-down system using two screws acting directly upon the cylinder. The one unusual aspect of the KO set-up was the fact that the two screws were inserted upwards through two holes drilled in a pair of lugs cast fore and aft into the crankcase for that purpose. The two screws mated with threaded holes in the relatively thick lower cylinder flange.  The KO 29 featured a pair of stiffening gussets on the upper surfaces of the mounting lugs, one on each side. These were absent on the OK model. It would appear logical to deduce from this that the KO designers may have suspected a weakness in this area, but in fact the lugs are quite substantial in themselves while the size of the gussets is such that they would contribute little to the structural integrity of the engine. They were probably included for customer reassurance more than anything else!

The KO 29 featured a pair of stiffening gussets on the upper surfaces of the mounting lugs, one on each side. These were absent on the OK model. It would appear logical to deduce from this that the KO designers may have suspected a weakness in this area, but in fact the lugs are quite substantial in themselves while the size of the gussets is such that they would contribute little to the structural integrity of the engine. They were probably included for customer reassurance more than anything else!  Apart from the above, virtually the only other visible difference is the fact that the KO fuel tank lacks the filler cap which appears on the OK model. The filler hole size confirms that such a cap was never present. Otherwise, the tanks are essentially identical.

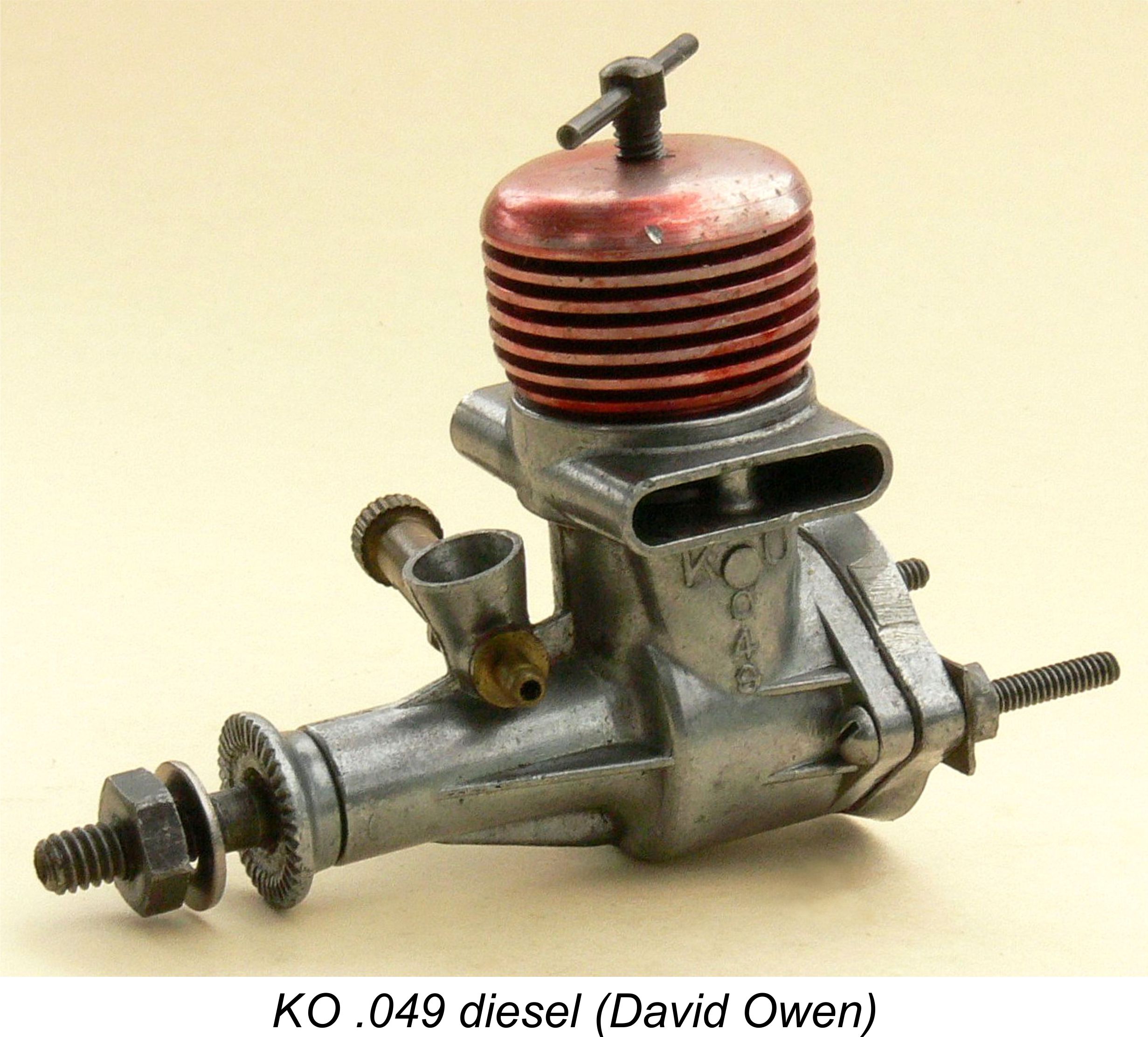

Apart from the above, virtually the only other visible difference is the fact that the KO fuel tank lacks the filler cap which appears on the OK model. The filler hole size confirms that such a cap was never present. Otherwise, the tanks are essentially identical. During the period under discussion, the Kondo brothers also manufactured a .19 cuin. model which was briefly produced as a spark ignition model before being converted to glow-plug ignition (or was perhaps offered concurrently in spark ignition form as an option). While this engine bore a certain family resemblance to its larger sibling, it displayed very different design influences as well as some more advanced thinking in engineering terms. Here we must turn our attention away from the OK design which clearly influenced the KO .29 previously described, looking instead to the Ohlsson & Rice (O&R) range for our source of design inspiration.

During the period under discussion, the Kondo brothers also manufactured a .19 cuin. model which was briefly produced as a spark ignition model before being converted to glow-plug ignition (or was perhaps offered concurrently in spark ignition form as an option). While this engine bore a certain family resemblance to its larger sibling, it displayed very different design influences as well as some more advanced thinking in engineering terms. Here we must turn our attention away from the OK design which clearly influenced the KO .29 previously described, looking instead to the Ohlsson & Rice (O&R) range for our source of design inspiration. What does appear certain is that the designers still wished to create a unit that possessed a certain “International” cachet in design terms which might attract both domestic customers and temporary residents from overseas. In the case of the .29 model, they had taken the popular OK .29 design as their inspiration, but at this time OK did not have a .19 cuin. model on the market for them to emulate.

What does appear certain is that the designers still wished to create a unit that possessed a certain “International” cachet in design terms which might attract both domestic customers and temporary residents from overseas. In the case of the .29 model, they had taken the popular OK .29 design as their inspiration, but at this time OK did not have a .19 cuin. model on the market for them to emulate. The Kondo brothers clearly elected to follow the second of the above options by taking the FRV version of the O&R .19 (or perhaps the slightly earlier .23) as their basic design inspiration. As with the OK .29 model, they would doubtless have had ample opportunity to examine examples of this very popular design in the hands of American service personnel.

The Kondo brothers clearly elected to follow the second of the above options by taking the FRV version of the O&R .19 (or perhaps the slightly earlier .23) as their basic design inspiration. As with the OK .29 model, they would doubtless have had ample opportunity to examine examples of this very popular design in the hands of American service personnel.  I'm again fortunate in having a fine example of the glow-plug version of this relatively rare engine on hand for study purposes. As with the KO .29 model, it seems best to begin by pointing out the similarities which lead to the inescapable conclusion that the KO .19 was inspired by the design of the O&R engines. These are not hard to spot! To begin with, both engines use steel cylinders with integral cooling fins and an alloy cylinder head. The cylinder is attached at its base in both cases, thereby once more freeing the working cylinder walls from hold-down stresses and potential distortion. Both designs employ two points of cylinder attachment located fore and aft. The exhaust stack is located on the left-hand side (looking forward) in both cases.

I'm again fortunate in having a fine example of the glow-plug version of this relatively rare engine on hand for study purposes. As with the KO .29 model, it seems best to begin by pointing out the similarities which lead to the inescapable conclusion that the KO .19 was inspired by the design of the O&R engines. These are not hard to spot! To begin with, both engines use steel cylinders with integral cooling fins and an alloy cylinder head. The cylinder is attached at its base in both cases, thereby once more freeing the working cylinder walls from hold-down stresses and potential distortion. Both designs employ two points of cylinder attachment located fore and aft. The exhaust stack is located on the left-hand side (looking forward) in both cases. The main bearing arrangements are similar as well. Both engines feature a bolt-on front cover which incorporates both the bronze-bushed main bearing and the FRV intake venturi (the O&R did not acquire a roller bearing at the rear of the shaft until mid to late 1949). The front of the cover in both instances is deeply recessed between the stiffening webs and the intake. In both cases too, the front covers are attached to the main casting by three screws. The spraybars are very similar as well. Finally, both designs feature a backplate which is cast integrally with the main casting.

The main bearing arrangements are similar as well. Both engines feature a bolt-on front cover which incorporates both the bronze-bushed main bearing and the FRV intake venturi (the O&R did not acquire a roller bearing at the rear of the shaft until mid to late 1949). The front of the cover in both instances is deeply recessed between the stiffening webs and the intake. In both cases too, the front covers are attached to the main casting by three screws. The spraybars are very similar as well. Finally, both designs feature a backplate which is cast integrally with the main casting. It is this feature which most strongly suggests that the KO .19 design was developed somewhat later than the companion .29 model. Certainly, the revised head allowed for the efficient use of a piston with an upstanding baffle, the head being contoured to suit (visible through the plug hole). The O&R also used a low-profile baffle, but the head could not be contoured to match. Accordingly, the combustion chamber of the O&R at top dead centre was more or less divided by the baffle into two separated compartments, the disadvantage being that the centrally-located plug favoured the timely ignition of only one of these two “compartments”. This would considerably delay the full involvement of the charge in the combustion process.

It is this feature which most strongly suggests that the KO .19 design was developed somewhat later than the companion .29 model. Certainly, the revised head allowed for the efficient use of a piston with an upstanding baffle, the head being contoured to suit (visible through the plug hole). The O&R also used a low-profile baffle, but the head could not be contoured to match. Accordingly, the combustion chamber of the O&R at top dead centre was more or less divided by the baffle into two separated compartments, the disadvantage being that the centrally-located plug favoured the timely ignition of only one of these two “compartments”. This would considerably delay the full involvement of the charge in the combustion process. Another significant engineering change was the means of securing the cylinder to the crankcase. The KO designers clearly wished to retain the benefits of the unstressed cylinder walls which resulted from the attachment of the cylinder at its base rather than through the head. However, it’s equally clear that they didn’t like the O&R approach of using a pair of spot welds fore and aft to achieve this objective. The major downside of the O&R system was the fact that if a new crankcase was required as a result of crash damage, one also had to buy a new piston, cylinder and head. The converse was true if the piston/cylinder required replacement - a new case and head then had to be purchased as well. The same spot weld system was used in a slightly modified form in the contemporary

Another significant engineering change was the means of securing the cylinder to the crankcase. The KO designers clearly wished to retain the benefits of the unstressed cylinder walls which resulted from the attachment of the cylinder at its base rather than through the head. However, it’s equally clear that they didn’t like the O&R approach of using a pair of spot welds fore and aft to achieve this objective. The major downside of the O&R system was the fact that if a new crankcase was required as a result of crash damage, one also had to buy a new piston, cylinder and head. The converse was true if the piston/cylinder required replacement - a new case and head then had to be purchased as well. The same spot weld system was used in a slightly modified form in the contemporary  A further engineering change was the means of securing the front housing to the main crankcase. The O&R design utilized three long bolts which passed from the front right through holes drilled longitudinally through the rather thick engine bearers and an extrusion at the bottom of the case. These bolts were secured at the rear with nuts, an arrangement which allowed for radial mounting of the engine. The KO designers clearly did not feel the need to provide for radial mounting. Accordingly, the three screws which retained the front cover in that design simply threaded directly into tapped holes in the material of the crankcase.

A further engineering change was the means of securing the front housing to the main crankcase. The O&R design utilized three long bolts which passed from the front right through holes drilled longitudinally through the rather thick engine bearers and an extrusion at the bottom of the case. These bolts were secured at the rear with nuts, an arrangement which allowed for radial mounting of the engine. The KO designers clearly did not feel the need to provide for radial mounting. Accordingly, the three screws which retained the front cover in that design simply threaded directly into tapped holes in the material of the crankcase. Other departures from the O&R design which were carried over from the larger KO model included the aerofoil-section exhaust stack and the tall forward-raked un-braced intake venturi with its open end chamfered at a sharp forward angle to catch the slipstream. The OK-style needle valve assembly was also carried over from the KO .29. The O&R .19 had no tank, but the KO .19 featured a tank which was of an identical pattern to that used on the KO .29.

Other departures from the O&R design which were carried over from the larger KO model included the aerofoil-section exhaust stack and the tall forward-raked un-braced intake venturi with its open end chamfered at a sharp forward angle to catch the slipstream. The OK-style needle valve assembly was also carried over from the KO .29. The O&R .19 had no tank, but the KO .19 featured a tank which was of an identical pattern to that used on the KO .29. Despite the obvious design influence exercised upon the KO .19 by its O&R contemporary, the two were in fact quite distinct designs. Which was the more successful in performance terms? My only indication of this factor comes from a spot test which I ran on an O&R .19 glow-plug model for my mate Maris Dislers. Using straight 75/25 methanol/castor FAI fuel, the O&R turned an APC 8x4 at 9,300 RPM - a very poor showing, almost certainly due to the engine's ridiculously low compression ratio of less than 5 to 1. It could barely keep going with the plug disconnected.

Despite the obvious design influence exercised upon the KO .19 by its O&R contemporary, the two were in fact quite distinct designs. Which was the more successful in performance terms? My only indication of this factor comes from a spot test which I ran on an O&R .19 glow-plug model for my mate Maris Dislers. Using straight 75/25 methanol/castor FAI fuel, the O&R turned an APC 8x4 at 9,300 RPM - a very poor showing, almost certainly due to the engine's ridiculously low compression ratio of less than 5 to 1. It could barely keep going with the plug disconnected.

I've noted in other articles that the .099 class seems to have been extremely important in the context of the Asian market, occupying much the same position in that market as the .049

I've noted in other articles that the .099 class seems to have been extremely important in the context of the Asian market, occupying much the same position in that market as the .049

The manufacture and further development of the company’s R/C equipment continued throughout this period, with the R/C product line becoming increasingly dominant by comparison with the engines. Following the company’s entry into the proportional R/C field, the trade-name KO PROPO was applied to their R/C products, but the registered company name remained unchanged throughout. Ownership of the company remained within the Kondo family as well.

The manufacture and further development of the company’s R/C equipment continued throughout this period, with the R/C product line becoming increasingly dominant by comparison with the engines. Following the company’s entry into the proportional R/C field, the trade-name KO PROPO was applied to their R/C products, but the registered company name remained unchanged throughout. Ownership of the company remained within the Kondo family as well. The Kondo Model Company produced the quaintly-named .12 cuin. “Mighty .12” glow-plug motor in both control-line and R/C forms. Early examples of this model actually retained the KO identification cast in relief onto the crankcase, but this was dropped from later products. Even at this late date, the designers were still attached to the long-stroke concept - the “Mighty .12” featured bore and stroke measurements of 13.50 mm and 13.80 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.97 cc (.12 cuin. exactly). The engine was a compact and well-made unit having a quite attractive appearance. However, it offered nothing special in the way of features or performance. Consequently, it does not appear to have remained long on the market.

The Kondo Model Company produced the quaintly-named .12 cuin. “Mighty .12” glow-plug motor in both control-line and R/C forms. Early examples of this model actually retained the KO identification cast in relief onto the crankcase, but this was dropped from later products. Even at this late date, the designers were still attached to the long-stroke concept - the “Mighty .12” featured bore and stroke measurements of 13.50 mm and 13.80 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.97 cc (.12 cuin. exactly). The engine was a compact and well-made unit having a quite attractive appearance. However, it offered nothing special in the way of features or performance. Consequently, it does not appear to have remained long on the market. During the period discussed in this article, the KO PROPO equipment was not readily available outside of the Asian market. However, all of this changed in 2007 with the establishment of an American subsidiary,

During the period discussed in this article, the KO PROPO equipment was not readily available outside of the Asian market. However, all of this changed in 2007 with the establishment of an American subsidiary,