|

|

Bronx Bad Boy - the G.H.Q. Spark Ignition Engine

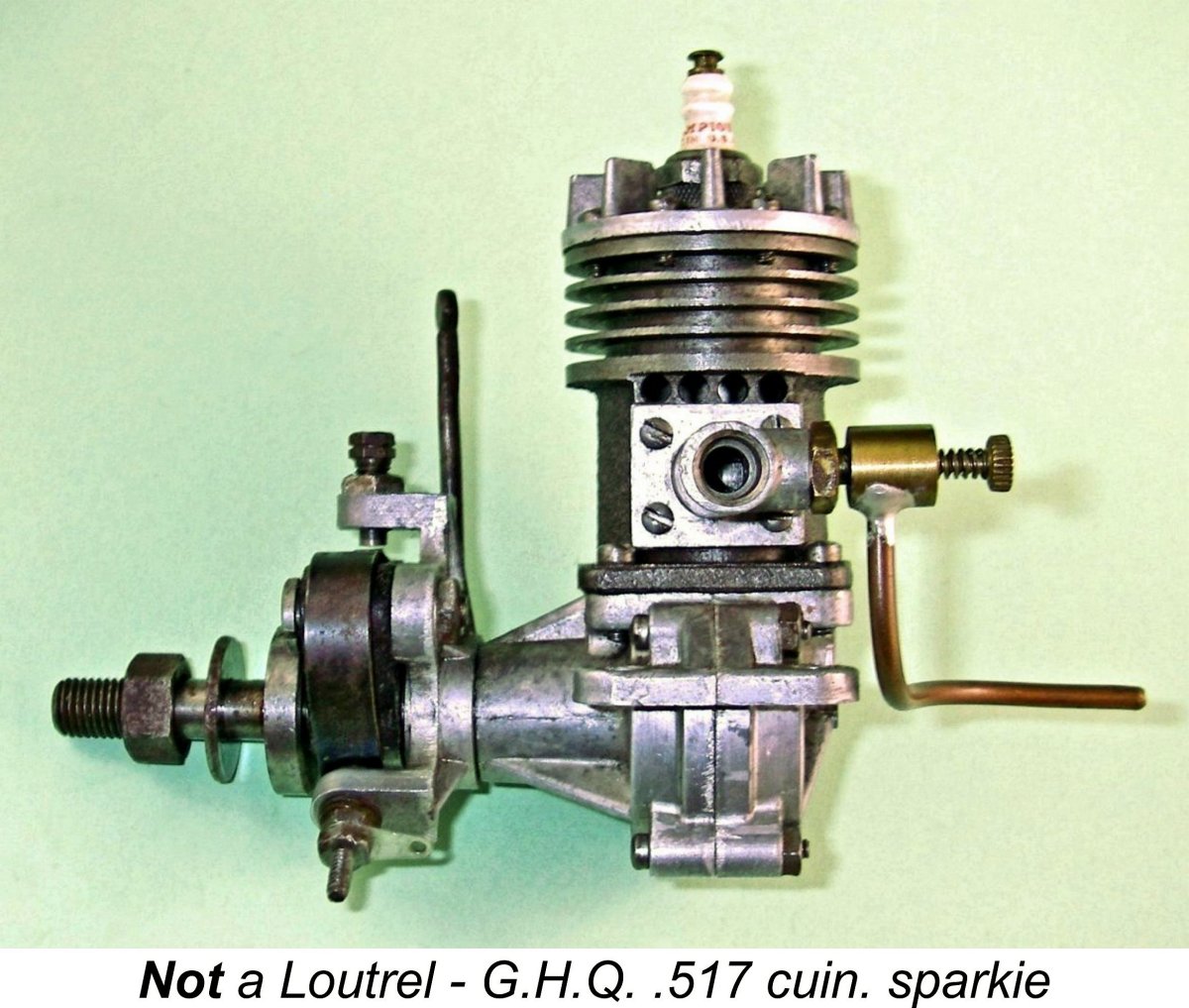

In the model engine world, there’s little debate regarding the unchallengeable right of the infamous American-made Deezil in its later Gotham Hobby rendition to be accorded the title of the “world’s worst” model diesel. Even the much-maligned Milford Mite from England can't compete! Although a few of the early pre-Gotham examples were actually very good engines, as I’ve shown in my separate article on the Deezil, the majority of them certainly lived well down to the engine’s sorry reputation. Despite this, the Deezil remains enduringly popular among present-day model engine enthusiasts, doubtless for the reasons stated above. OK, so we seem to have a secure candidate for the title of the world’s worst model diesel engine. What about the world’s worst spark ignition unit? Setting aside the later "slag" engines, which are in a class of their own, common opinion among old-time modellers and engine enthusiasts alike has it that this particular honor goes to the subject of this article - the infamous G.H.Q. .517 cuin. (8.48 cc) sparkie from New York, USA. Must be something about New York ….. the Deezil came from there as well!! In reality, the connection is as much personal as it is geographic - there’s a close family connection, as we shall see.

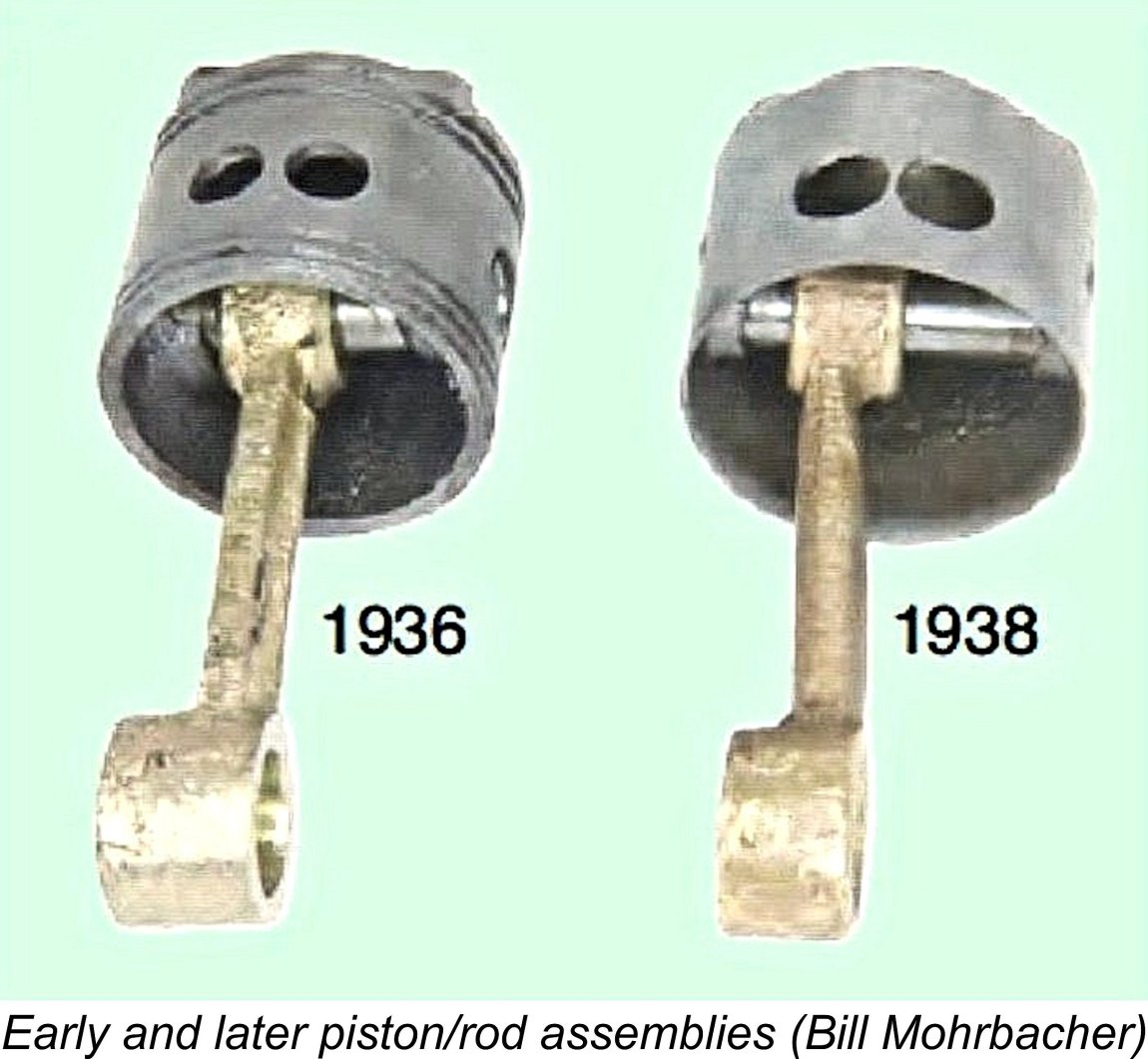

There’s already a fair bit of information out there on the G.H.Q. It was the subject of article no. 28 in the series authored by the late David R. Janson under the general title “Model Engine Designer and Manufacturing Profiles”. This write-up may still be accessed online on the late Ron Chernich’s now-frozen but still invaluable “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. More recently, the G.H.Q. was the subject of a number of articles in Tim Dannels’ indispensable but now discontinued “Engine Collector’s Journal” (ECJ). Issue no. 233 for June 2016 included a collaborative article by Tim and Bill Mohrbacher in which the engine’s construction was discussed in detail. Bill actually went to the trouble of dismantling his 1936 and 1938 engines to show some of the changes which resulted from the later manufacturer’s efforts to cut costs at the expense of quality. More of that below in its place …………..for now, I wish to acknowledge with gratitude the fact that I’ve used a number of illustrations from that article in the present document, with Tim's kind permission. ECJ issue no. 236 for December 2016 carried an additional commentary by long-time G.H.Q. enthusiast David Axler, who has assembled quite a stable of operable G.H.Q. engines and has an amazing amount of knowledge about how to make them run. David regularly flies models powered by these engines, so he knows what he’s talking about! His ECJ article discussed the challenges of getting these things to perform well enough to fly a model. With all of this material already available, why bother to add to the pile by preparing this further article? For four reasons - first, the earlier works did not cover the origins and manufacturer changes involved in any great detail. Secondly, they downplayed the human interest side of the story, including the role of the late Bernie Winston of America's Hobby Center (AHC) fame. Thirdly, no actual testing of the engine was featured. And finally, there's a need for comprehensive and readily accessible online information on these engines. This article will address all of these matters. There's always a human element in the history of any model engine. Like that of the equally infamous Deezil, the story of the G.H.Q. is inextricably entangled with that of Bernard B. “Bernie” Winston of New York. In other articles on this website, most notably that about the Deezil, I’ve recounted the story of how Bernie and his brothers founded the famous America’s Hobby Centre (AHC) store in New York in 1931, as well as the ensuing post-WW2 family split and the manner in which that split prompted the creation of the Gotham Deezil. I do not intend to reprise that material here - interested readers are referred to the Deezil article. For present purposes, it seems best to go back to the beginning and trace the train of events which led up to the production of the G.H.Q beginning in 1936. Origins

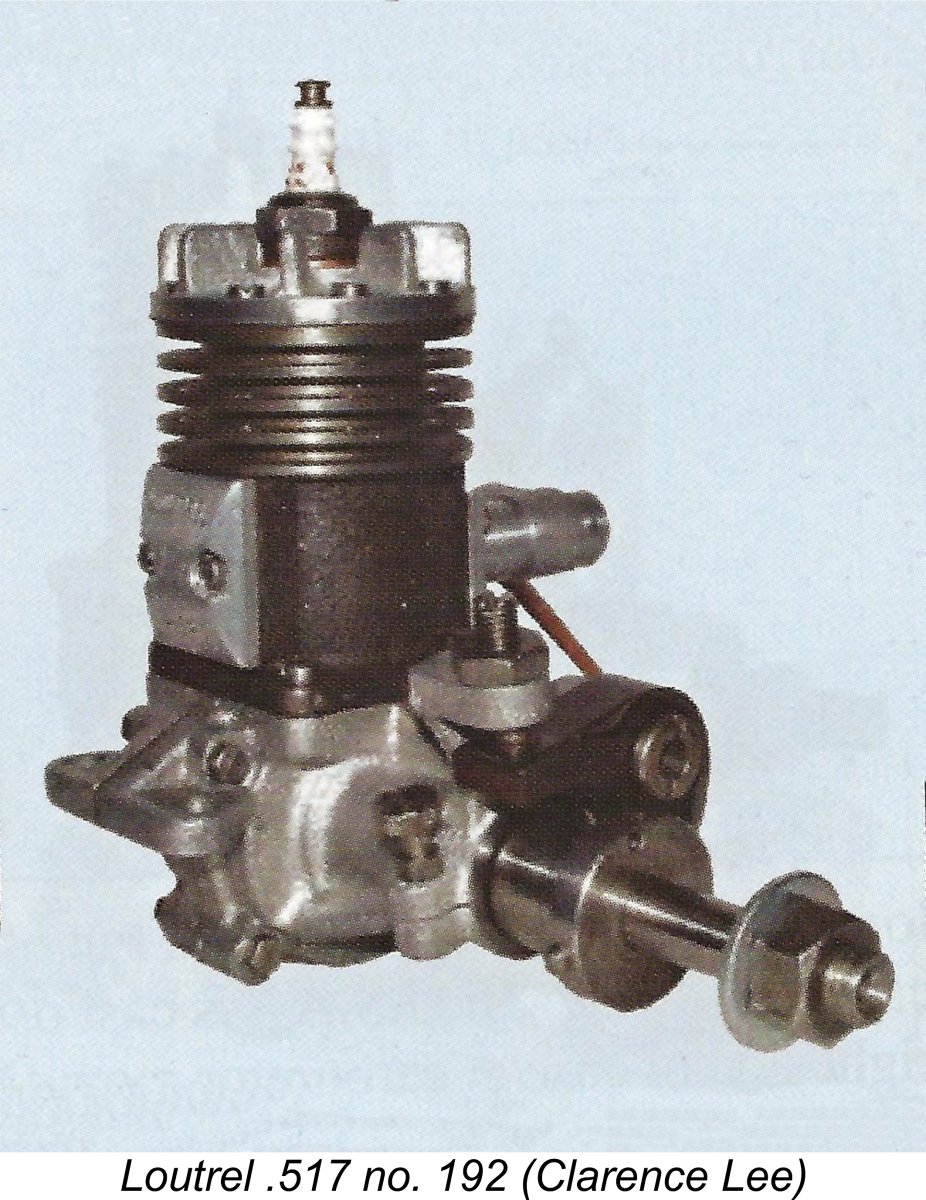

At some later point in time, Loutrel took over the Weiss design outright. He promptly redesigned it to eliminate the rear timer, increased the displacement from .331 to .517 cuin. and put the revised model into production under his own name.

The fact that the cited business address of Loutrel's company lies in Brooklyn rather than the Bronx does not preclude the possibility that the engines were actually made at a different location. The McDonough Street address may have doubled as both Loutrel's residence and business address, with the engines being made elsewhere. There are many precedents for such a division of locales. At this stage, sand-castings were used throughout. Loutrel also made the coils with which the engine was supplied, winding these himself by hand. The engines were supplied in a sturdy cardboard box which included the plug, coil and condenser along with the engine itself, as seen in the eBay image reproduced below.

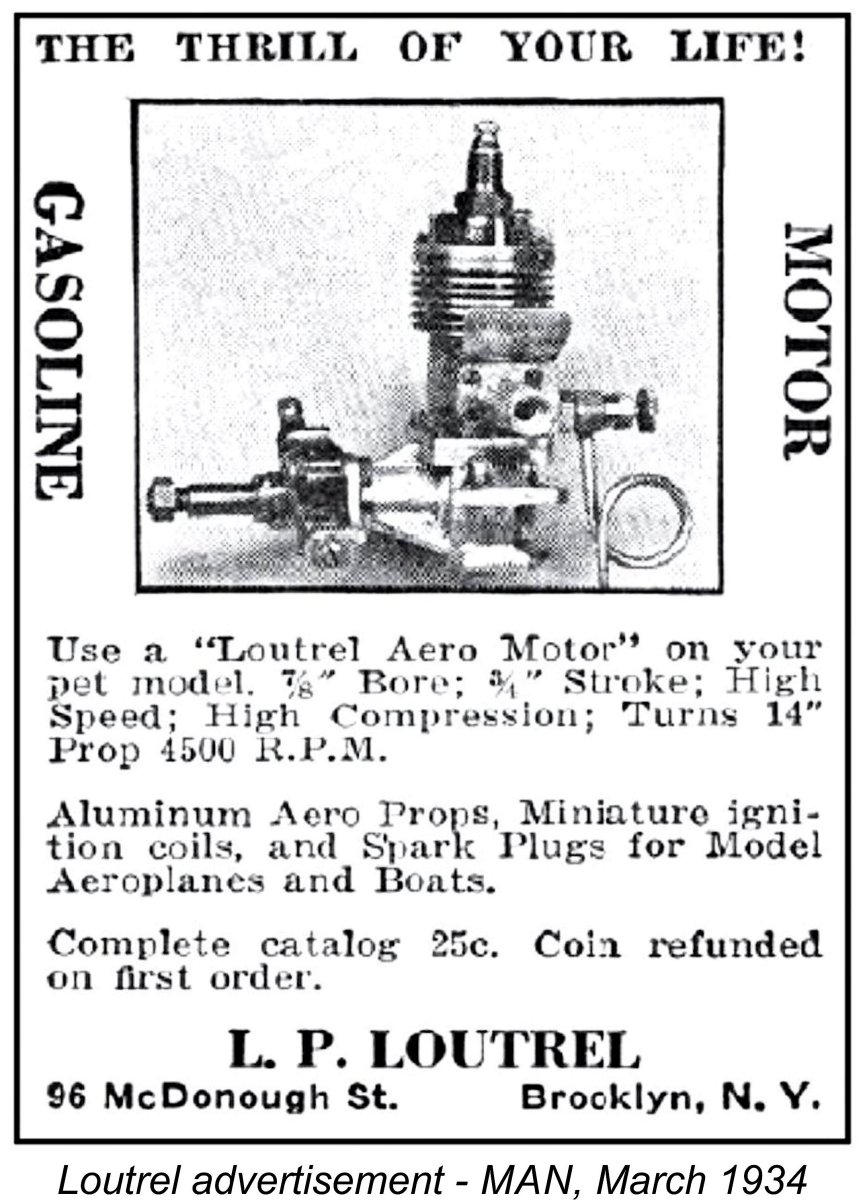

Loutrel advertised the engine in the national modelling media, attracting a considerable amount of sales interest by doing so. The relatively steep asking price of $35 was no deterrent even during these Depression years - there simply weren't any other commercially-available competitors at the time. The Brown Junior B didn't appear in commercial quantities until mid 1934, putting Loutrel well ahead of the pack. The attached advertisement from the March 1934 issue of "Model Airplane News" (MAN) is a typical advertising placement. However, the positive response to these ads created its own set of problems. As time went on, the rate at which By early 1936, this situation had worsened to the point where Loutrel began to look at the alternative of selling the design and associated tooling to another company which might be in a position to produce the engine at a rate which matched demand. Perhaps unfortunately as things turned out, he ended up selling the manufacturing rights, equipment, tooling and goodwill for the Loutrel engine to Bernie Winston, who in 1931 had joined with his three brothers to found what was to become the famous America's Hobby Center (AHC) store at 146 West 22nd Street in New York’s Lower Manhattan area. Whatever one may say about Bernie Winston and his business methods (and a lot can be said!), there's no doubt that he was a genuine model engine enthusiast who kept in touch with the fledgling model engine market and was keen to enter that market himself. He also did much to promote power modelling in the USA through his various publications. As of the mid 1930's, he had become a sincere admirer of Louis Loutrel and his highly regarded engine. Consequently, he was very happy to take Loutrel up on his offer to sell.

Under the terms of the all-cash deal, AHC purchased both the design and the associated manufacturing equipment from Loutrel, along with the goodwill attached to the Loutrel name. It seems likely that AHC simply took over Loutrel's workshop, which evidently continued to operate under its new ownership in its rented accommodation in the Bronx. The agreement also included an undertaking by Loutrel to train AHC’s employees to produce the engine. However, in Bernie’s later recollection (see below) Loutrel proved to be somewhat unreliable in fulfilling this part of the deal, although he did work for AHC for some time, albeit rather sporadically. In hindsight, it’s difficult to avoid the suspicion that Loutrel’s “unreliability” may have been directly related to his early realization that AHC’s intention was to trash his design down to a price, as will be discussed in the following section of this article. He may have been doing as much as possible to disassociate himself from the G.H.Q. saga, seeing it as a source of embarrassment.

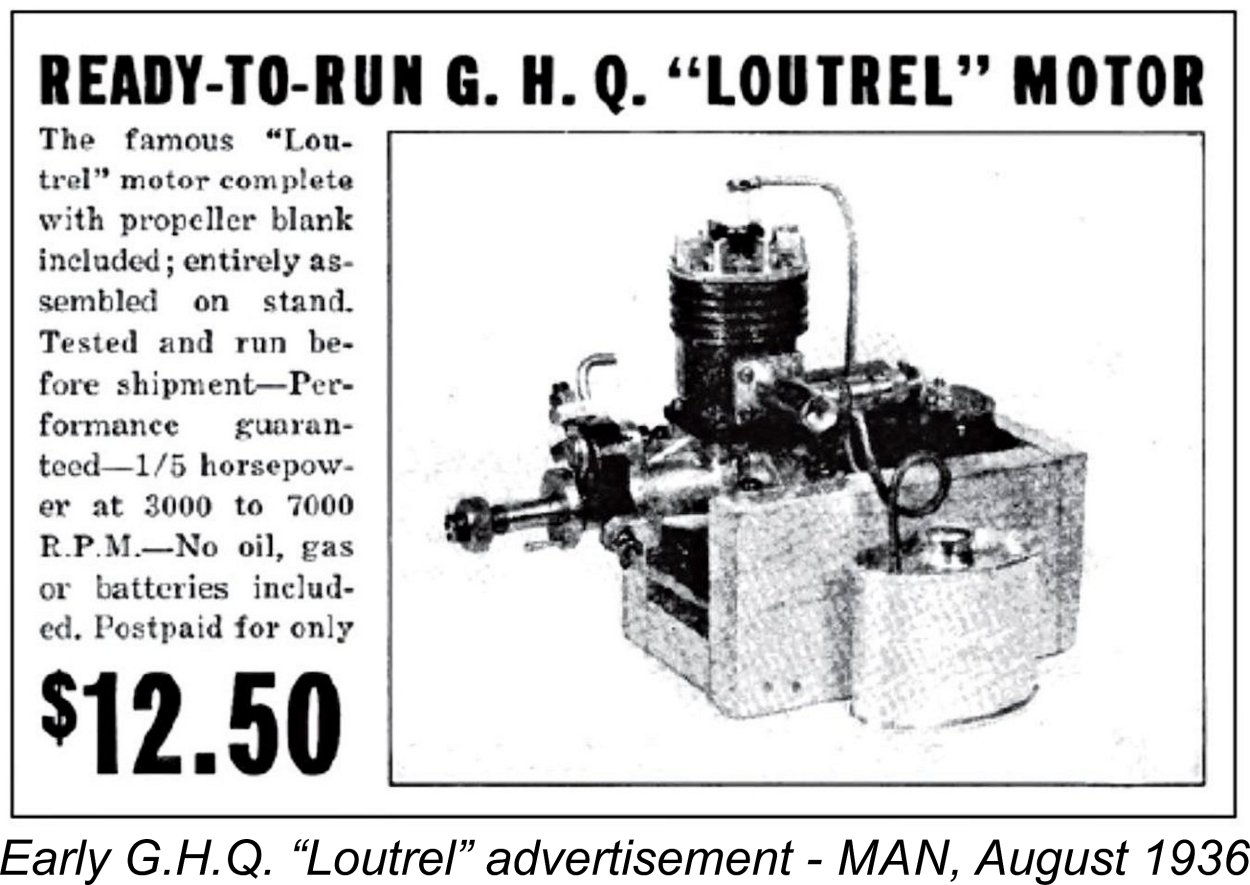

Since this address definitely does lie well within the previously-mentioned area of the Bronx known as “Fort Apache” where Louis Loutrel reportedly made his original engines, it’s quite likely that this was in fact the location of Loutrel’s original workshop facility. If this was indeed the case, Loutrel's formerly-cited McDonough Street location in Brooklyn would have been merely his business address and perhaps his residence. It’s possible and indeed likely that the engines continued to be manufactured at Loutrel's former workshop following the AHC takeover - why go to the trouble and expense of relocating all that machinery and tooling that you've just bought when it's already installed in suitable rented accommodation?!? It’s also revealing to note that the early advertising retained the Loutrel name along with that of the G.H.Q. This was presumably done to cash in on the positive reputation (aka goodwill) established by the Loutrel product - the terms of the sale allowed Bernie Winston to do this. However, by 1937 this connection no longer appeared in the G.H.Q. advertising. Mid 1936 - G.H.Q. Production Commences One of the characteristics that comes through very consistently when considering the career of Bernie Winston is his unswerving dedication to the concept of making a buck by any legal means which came to hand, regardless of the strict morality involved. In keeping with this mindset, his first reaction upon acquiring the Loutrel design and equipment was to investigate ways of cutting production costs. Fair enough, but unfortunately if this meant also cutting back on quality, Bernie was seemingly fine with that! Therein lies the tragedy (if we may call it that) of the G.H.Q. - it started out as a perfectly capable design by Louis Loutrel which was ruthlessly trashed down to a price by AHC with no regard for quality. Two of Bernie’s brothers were to follow exactly the same path with the Deezil after establishing the competing Gotham Hobby business following the post-WW2 family split.

The initial 1936 examples of the engine which were advertised as G.H.Q. “Loutrel” models apparently ran OK for the most part, but that may well have been because they were largely constructed using left-over Loutrel components. Once the cost of producing those components on an ongoing basis became clear, Bernie Winston was characteristically quick to begin seeking ways and means of cutting costs, hence maximizing profits. The first step was to arrange for the production of die-cast alloy components in place of the sand-castings used formerly. Another early cost-cutting measure was the use of automatic machinery to wind the ignition coils, which had previously been made by hand by Louis Loutrel. Both of these were perfectly reasonable changes in production methods.

This should logically have required a change in the relative placements of the exhaust and transfer ports to maintain something approaching a reasonable timing diagram. To what extent this was done is unclear - all that can be said is that images of the Loutrel and G.H.Q engines show no external evidence of any change having been made. A hint that AHC may have anticipated a certain slackening of precision in the piston/cylinder fit is the fact that the revised cast iron pistons featured a set of oil retention grooves at the top and botton of the piston skirt. These grooves would contribute to an improved seal with a slacker-than-optimal piston fit while also enhancing the lubrication of the piston/cylinder working interface. Of course, it didn't stop there. The engine was still advertised as having a cast iron piston as of January 1937, but shortly thereafter the cast iron piston was replaced in its entirety. A revised piston design was adopted which was created from a steel stamping rather than the machined iron casting used previously. One of the casualties of this change was the piston baffle, which was replaced by a completely ineffective “dome” on the piston crown. Despite Bernie’s later claims to the contrary, many surviving examples of this variant show no signs of having been ground or lapped to fit - they just went in as they came. Having handled a few of these later engines, I can certainly attest to their woefully inadequate piston fits. The only positive aspect of this change was a significant reduction in piston weight.

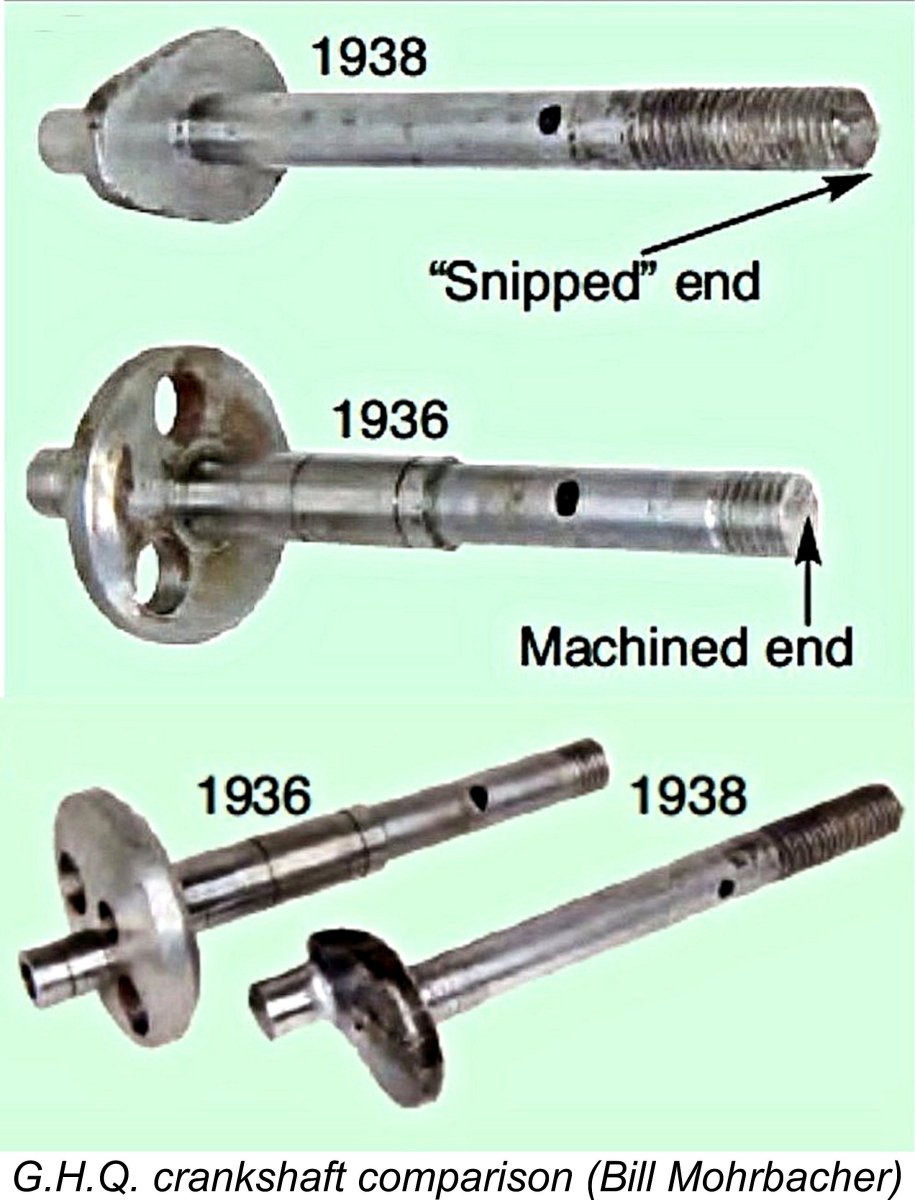

A further change for the worse was a reduction in the main journal diameter of the crankshaft from 3/8 in. to 5/16 in. throughout, along with a considerable deterioration in the quality of its surface finish. This eliminated the shoulder against which the prop driver had previously borne, forcing the taper pin which keyed the prop driver to the shaft (see below) to accept the axial loading resulting from prop tightening as well. The net result of all this cost-cutting was an engine which, while looking a lot like its Loutrel predecessor, exhibited none of the quality of that model. The very poor to non-existent compression seal in most examples, the sub-standard shaft finish, the absence of an effective piston baffle and the inconsistent and mutually incompatible placement of the drilled cylinder ports combined to produce an engine which generally wouldn’t even start, let alone run! By this time, the machine shop in which the G.H.Q. engines were manufactured was reportedly under the management of Bernie Winston's brother Harry. We've already seen that in all probability this machine shop was the very one in which Louis Loutrel had produced his own far superior model. If so, it seems to have gone downhill under Harry Winston's management - several posters on the various modelling forums have claimed (rightly or wrongly) that Harry Winston's machine shop was one of the few in the USA that didn't get a Government production contract following America's entry into WW2 in December 1941. Some unkind souls have speculated that the Government inspectors took one look at the trashed-down G.H.Q. and figured that America's war machine deserved something a little better! The fact that Bernie Winston continued to promote this sorry product so energetically doesn't speak well of his business ethics. All his claims to the contrary, the trashed-down engine was poorly engineered, heavy, ungainly, distinctly “agricultural” looking, poorly finished and fitted and in most cases extremely reluctant to start, let alone run! Anecdotal information from numerous past owners and observers confirms that the majority of the engines would not run at all without skilled and knowledgeable owner intervention. Those few that did run (and there was the odd one!) generally only did so following hours of individual attention involving careful refitting, port cleanup, installation of proper gaskets and so on. Jokes of all types abounded concerning the engine, and deservedly so.

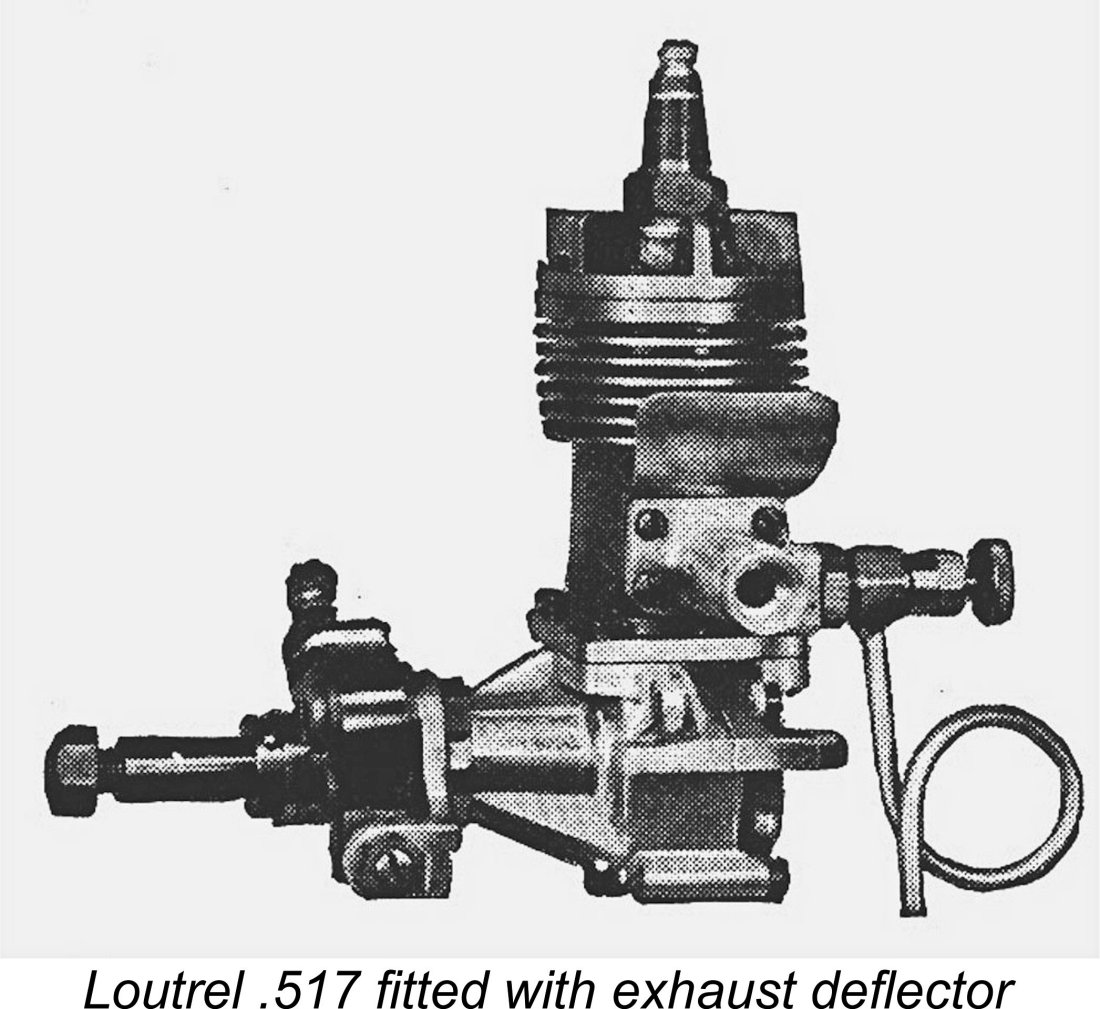

The G.H.Q. was offered both as a complete unit and in kit form. Bernie promoted the engine vigorously, publishing a four-page pamphlet that was a marvel of commentary on the engine, its running instructions, wiring diagram, important operational pointers, parts replacement and available accessories. These included a 14 in. dia. cast metal left-hand pitch prop (which upheld the G.H.Q. tradition by weighing all of 8½ ounces!), a flywheel, spark plug wrench, special "lubro" oil, battery box, coil holders, gauge set, midget switch, running stand, an oval gas tank and an exhaust deflector that was held in place by the top intake manifold retaining screws. All very impressive to read about and giving the impression of a great deal at $9.95 and later $3.95 as a kit. Bernie subsequently delved further The exhaust deflector was an interesting carry-over from the original Loutrel design. The fact that the exhaust was located directly above the intake manifold had the potential to give rise to some "recycling" of exhaust gasses and oil residues back into the intake, with highly detrimental effects upon performance and operational consistency. The accessory deflector directed the exhaust up and away from the intake, completely resolving this problem. It may be clearly seen in the accompanying Loutrel promotional image. Bernie also applied the G.H.Q. name to a range of kits, some of which were specifically claimed to have been designed for the G.H.Q. engine. A number of these are highlighted in the January 1937 advertisement which is reproduced above. An interesting feature of the advertising at this time was the offer to demonstrate an engine to any prospective customer who cared to call. I would be prepared to bet dollars to donuts on the probability that the demonstration engine was one of the earlier Loutrel models with a G.H.Q. bypass cover plate fitted! All of this was apparently entirely in character as far as Bernie Winston was concerned. In a post on a Richard remembered Bernie as “a real nice guy” who was unquestionably a genuine enthusiast as well as being a pioneer in the mail order discount business. However, Richard admitted that “Bernie was not above making a buck through the sale of what he knew to be garbage engines”. AHC’s later “slag” engines like the Thor and Genie immediately spring to mind…………. Bernie’s strategy certainly paid off in financial terms. Despite its many shortcomings, the fact that the G.H.Q. was among the lowest priced engines of them all led to sales running into the tens of thousands - hope evidently springs eternal if the price is right! Or perhaps people simply couldn’t believe that the engine was that bad, hence having to see for themselves! It's been credibly suggested that as many as 100,000 examples may have ended up being made prior to the onset of WW2 (as far as America was concerned).

In addition, Bernie soon began to focus his advertising for the G.H.Q. on non-aeromodelling publications such as "Popular Science" and "Popular Mechanics". The accompanying advertisement from the December 1937 issue of "Popular Science" typifies such placements. These ads reached prospective buyers who were not necessarily connected with the aeromodelling world, or even with each other. However, they were wide open to the idea of owning a novely like a small (by then-current standards) gas engine, especilly if the price was right. As a result of these factors, the engines' shortcomings did not prevent them from reaching the market in large numbers over a considerable period of time. The better-quality 1936 examples, most of which did run, presumably served as amassadors to establish a level of credibility which the later examples did not merit. One way or another, the engine seems to have found many purchasers, most of whom were doubtless extremely disappointed but lacked the technology to spread the word. You'd never get away with this kind of thing in today’s inter-connected world. Even so, many of those 100,000 engines remained unsold at the commencement of America’s involvement in WW2 in December 1941. We shouldn’t be surprised by this - by the time that 1940 rolled around, the reputation of the G.H.Q. had had ample time to become widely disseminated throughout America even without the Internet. Moreover, by that time there were many vastly superior engines readily available to the American public. These factors would inevitably give rise to a considerable slackening in demand for the G.H.Q. despite its very low price. Assuming that production was still on-going, a build-up of unsold inventory was inevitable under these conditions. This led directly to another of the factors that set the G.H.Q. apart from most of its competitors. Although model engine manufacture was officially banned in America during WW2 between early 1942 and late 1944, the G.H.Q. remained available throughout the war. Bernie Winston promoted the idea that actual production continued throughout most of the war, citing his ability to demonstrate "significant sales volume" to the Government as the reason why G.H.Q. was exempted from the ban. This idea has persisted down through the years. However, no sense whatsoever can be made of Bernie’s claim. For one thing, the significant sales volume cited by Bernie almost certainly didn’t exist as of late 1941, for the reasons stated above. Furthermore, the idea that large-scale production of a model engine would be officially encouraged at a time when the associated materials were being re-directed towards the war effort runs directly counter to the intent of the general ban on model engine production. That intent was to divert the associated material (as well as the engineering talents of the manufacturers) into war-related production. Surely it would be the large producers that would be the primary targets of such a ban, since they used the most material and had the greatest production capacity?!? If Bernie's claim was correct, why wasn't Ohlsson & Rice exempted as well? Their sales at this stage undoubtedly put those of G.H.Q. in the shade!

The idea that by this time there had been a change in the production situation is strongly supported by the fact that by the early 1940's the address of the supposedly still-active G.H.Q. manufacturers had changed from the former Bronx location where the engines were most likely made during the 1930's to a far more upmarket address at 40 East 21st Street in New York's Lower Manhattan district. It surely can't be a coincidence that this new location was only a few blocks from the main AHC store at 146 West 22nd Street. This is a highly improbable location for a precision (?) engineering workshop! Indeed, why go to the expense and trouble of moving the G.H.Q. manufacturing equipment from the Bronx to Lower Manhattan, especially at a time when sales must surely have been falling given the ever-increasing competition along with the G.H.Q.'s tattered reputation? Although there’s no direct evidence to prove this, it seems highly likely that manufacture of the engines had ceased by this time and the Lower Manhattan location was simply a business address through which the unsold stocks could be "independently" marketed without publicly tarring AHC with the G.H.Q. brush!

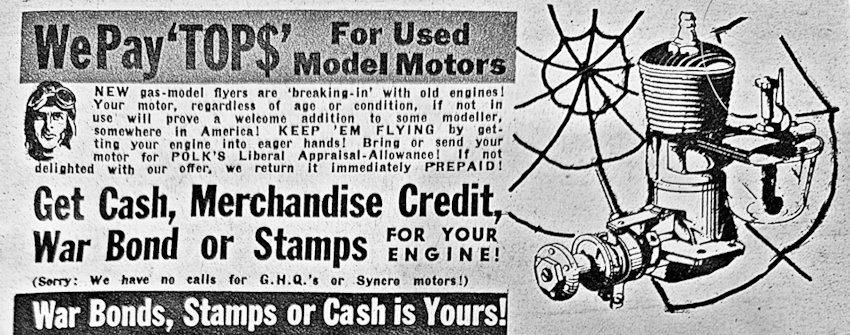

No doubt being somewhat short of model engine-related material as of 1942 due to the production ban, the widely-read magazine “Flying Aces” ran a brief article about the still-available G.H.Q. in the regular "Logging the Motor Mart" feature in their June 1942 issue. This article was a masterpiece of obfuscation - it implied that production of the engine was very much ongoing, with an "improved" 1942 model now on offer. In fact it was almost certainly pre-existing inventory that was being sold. The article also made much of the engine’s supposed "high standard of quality" despite the overwhelming amount of accumulated evidence to the contrary. It must be said that the writer displayed little journalistic integrity here! Perhaps he simply regurgitated information supplied by AHC........ Persuasive evidence of the low regard in which the G.H.Q. was actually held at this time is to be found in the attached advertisement from Polk's Model Craft Hobbies which appeared in the December 1943 issue of "Air Trails". Since the manufacture of new model engines was practically at a standstill at this point in time, Polk's and a few other sales outlets adopted a policy of buying used examples of pre-war engines from individuals who were notusing them and selling them to aspiring modellers who were otherwise unable to obtain engines.

There have been persistent and in some cases quite credible reports over the years that a significant number of additional G.H.Q. engines were made by various high school shop classes during WW2 as a training exercise relating to the preparation of young people to participate in the technical support activities relating to the war effort. This actually has the ring of truth about it. By Bernie Winston’s own account, he ran one of these training schools himself, with classes taking place every Saturday on the top floor of the AHC premises. Presumably these exercises were based upon the construction of the engine from the kits sold by AHC - Bernie would never have missed a trick like that! Because of the large inventory of unsold engines that had accumulated over the years, as well as ever-increasing sales resistance as more people became aware of their shortcomings and turned to their far superior competitors, it took until around 1948 for the G.H.Q. to finally disappear from the market. It appeared in published listings of model engines for that year, but disappeared thereafter. The engine thus enjoyed a market presence of some 12 years - far beyond its deserts in terms of quality and performance. Even if it had consistently run well within its design limitations, it would have stood no chance whatsoever in the glow-plug dominated marketplace which resulted from Ray Arden’s November 1947 introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug. An interesting post-script to this story surfaced in the June 1987 issue of "Model Builder" magazine, when regular engine reviewer Stu Richmond took the G.H.Q. as his retrospective subject. His review was especially noteworthy for reprinting a portion of a letter from Bernie Winston himself. It must be recalled that this letter was written decades after the events which it describes, creating the possibility that some of Bernie's stated recollections may have become a little clouded by time. This might explain some of the apparent inconsistencies. The relevant section appears below, preceded by Stu's lead-in to the letter. “Normally this is as much space as this column gets each month, but I struck gold when research yielded a letter to me directly from Bernie Winston, who runs America's Hobby Center, Inc., 146 West 22nd Street in New York City. Bernie Winston's business owned the G.H.Q factory! With his permission, I share parts of his great and interesting letter with you as follows: "The original G.H.Q. engine had been developed from an engine made at that time by a model engineer, Mr. Redfield. Louis Loutrel changed it so that it could be produced commercially. The engines were made in a rented storefront factory in the area of the Bronx known as “Fort Apache” (most likely located at 854 East 149th Street in the Bronx, as noted earlier - A.D.). We purchased the manufacturing equipment from Loutrel after he demonstrated his engine under all conditions. We paid him an all-cash deal upon his promise to train our men to produce the engine. He worked for us for some time, but he was very unreliable. However, by that time we had arranged for die-cast aluminum parts. The spark coils that he had made by hand were made for us by automatic machinery for far less than any on the market at that time. The die-cast parts were also far better than any on the market at that time. Most other engines were then made with sand-cast parts. We started production about 1935-36 and ended about 1944, since I had been notified of my induction into the Army. We had enough engines on hand to last quite a while. The government had given only two engine manufacturers allotments of critical materials needed for production, including tungsten (for ignition points) and cast iron for other parts. These allotments were based on proof of sales volume that we were able to produce. As far as we know, only Herkimer (O.K.) had sufficient proof as we had. While we produced on a steady basis, we turned to a lightweight, stamped piston (a revolution in engineering) ground to concentricity extremely accurately. We also developed a drop-forged crankshaft that was ground very accurately on the bearing surface. While some of the tooling still exists in our basement, the dies for casting were destroyed after 15 years of non-use. One of the differences (humorous or otherwise) was that the G.H.Q. ran and was designed to run in the opposite rotation of the engines of today. We did fall behind in production at one point when a good many of our employees (a group of motorcyclists who parked their machines in an entry way of the building) were discovered to be filling their empty tool boxes with our equipment. It took quite a while to retrain new employees (about 20) to handle the work. It is rather difficult to reconstruct the many incidences, problems, and financial intricacies that evolved so long ago. We were the first to use a Hutto honing machine, a Sunnen honing machine, and others that we had to view in other manufacturing fields and adapt to model engine manufacturing. For example, we had a neighbor who was a trumpet manufacturer and used the Hutto honer with great success. We bought one and received our schooling from the neighbor in the most difficult problem of honing a cast-iron cylinder with the problems of variable metals, bypass holes and exhaust port already made while the entire honing operation was being bathed in a cooling flood of pouring oil during the process. In those days we ran a school on the top floor of our store every Saturday..... we tested engines and taught modellers who brought their own engines. We never failed to run any engine." Given the fact that very few surviving unmodified examples of the latter-day G.H.Q. appear to be operable, one is forced to wonder about the veracity of the final statement in Bernie Winston’s letter! I’ve certainly handled a few G.H.Q.’s which would have resisted his best efforts! One is also forced to wonder how AHC managed to use that state-of-the-art honing equipment to produce so many poorly-fitted engines …………. Finally, it’s noteworthy that Bernie maintained what appears to be the fiction that the engine remained in production more or less throughout WW2. All that aside, now that we’ve traced the engine’s history, let’s turn to a closer look at the engine itself. Description

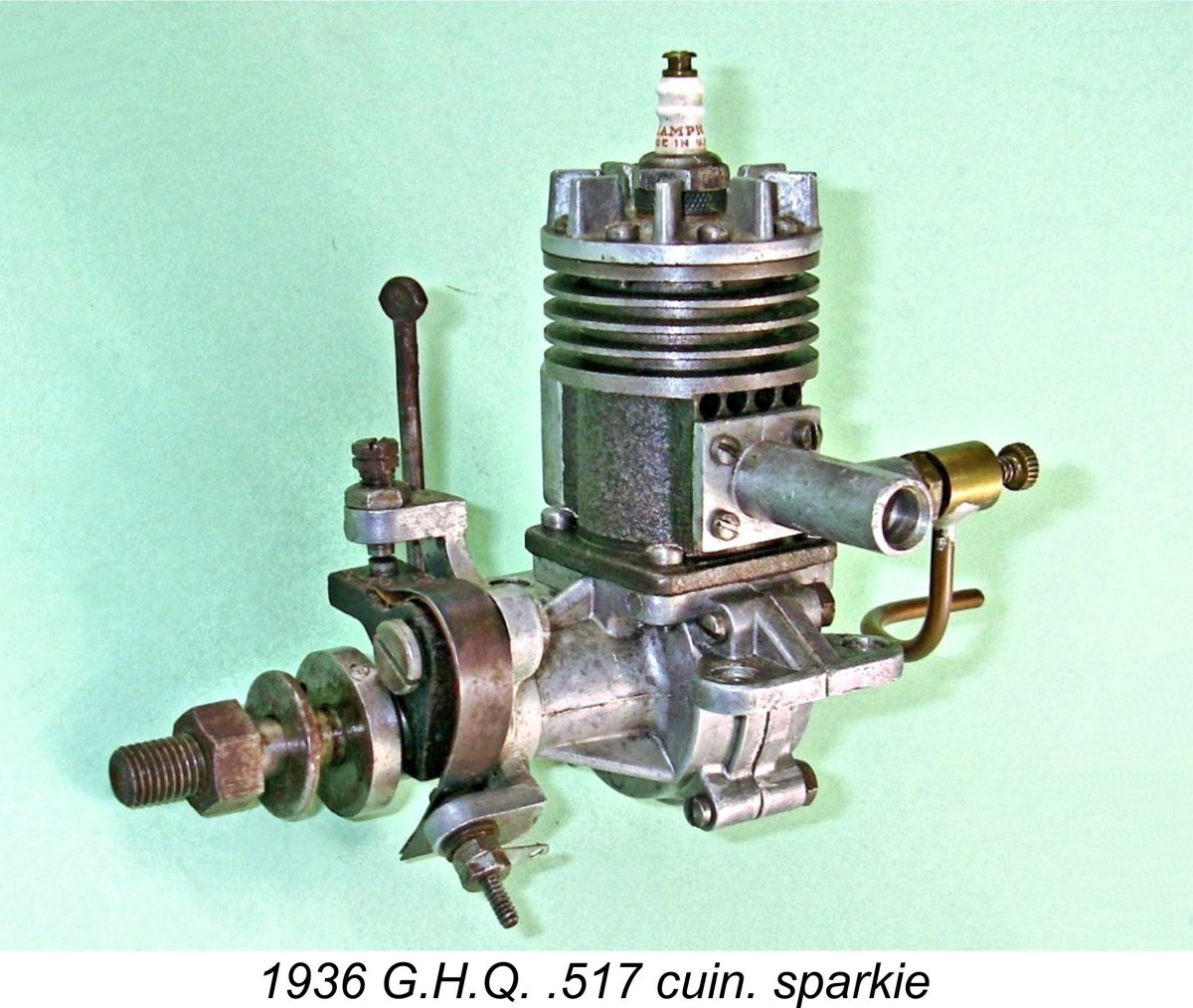

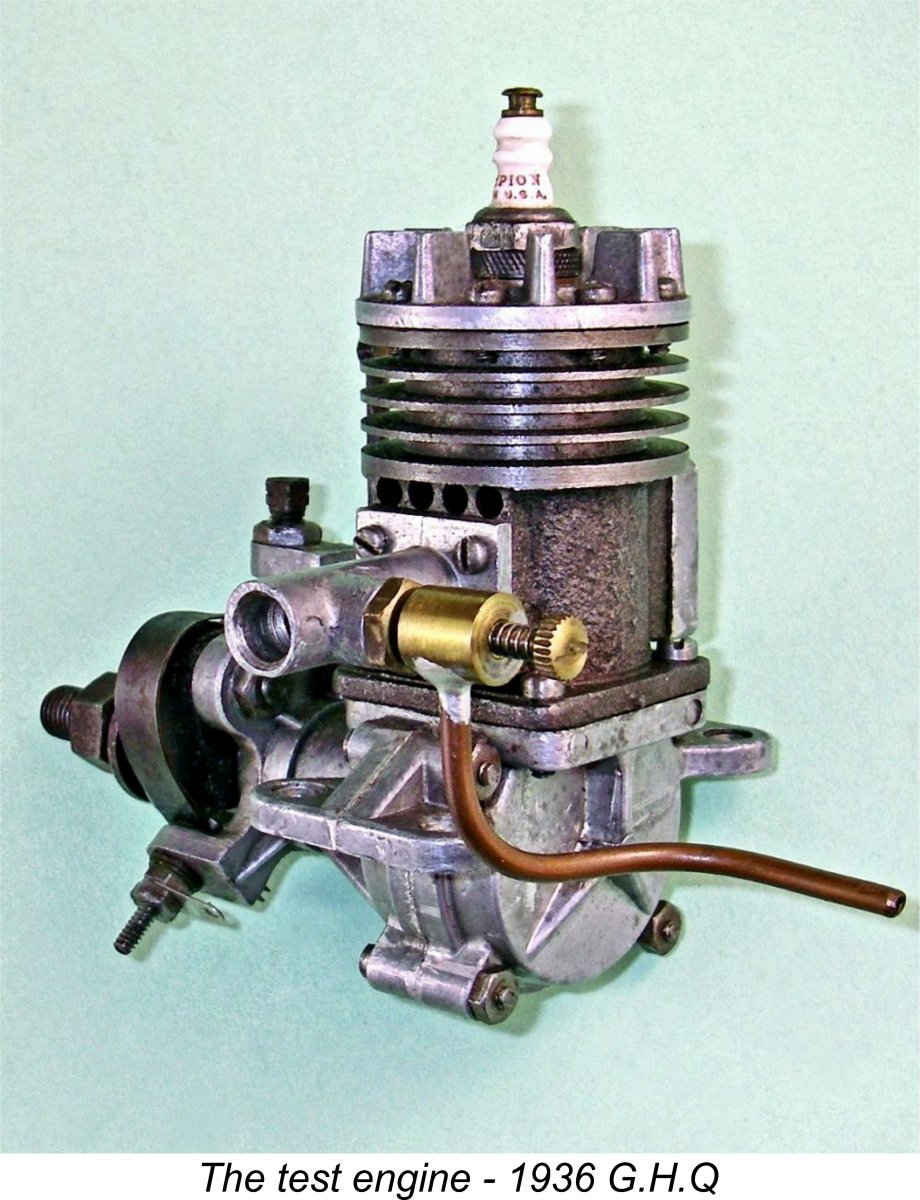

The G.H.Q. engine was a .517 cuin. (8.48 cc) displacement spark ignition motor. Its displacement was derived from nominal bore and stroke dimensions of 15/16 in. (23.81 mm) and ¾ in. (19.05 mm). Checked weight of my example with plug but minus prop, tank and ignition support system is a whopping 13.55 ounces (384 gm). The G.H.Q. was a sideport model having the exhaust located directly above the intake, which was rather unusually placed at the left side of the cylinder. While heavy, awkward and ugly looking, it encompassed many then-fashionable features such as an automotive timer, cast iron cylinder, radially finned head, two-piece vertically-split diecast aluminum case with beam mounts, strengthening webs on the mounting beams and the rear crankcase half, a spring-tensioned needle and a soldered copper fuel line. Starting at the top, eight screws secured the radially-finned cast aluminum head to the cylinder. A centrally-located 3/8-24 Champion spark plug was fitted as standard. The underside of the head on my example is completely plain, with no provision being made to accommodate the piston baffle. The volumetrically measured compression ratio of my example is 5.5:1, a figure which is very much on the low side even by mid 1930’s sparkie standards. This is the first parameter that helps to explain the engine’s reportedly mediocre performance. While this is a high enough compression ratio for a spark ignition engine to run, one can’t expect much in the way of performance, especially given the very inefficient combustion chamber shape.

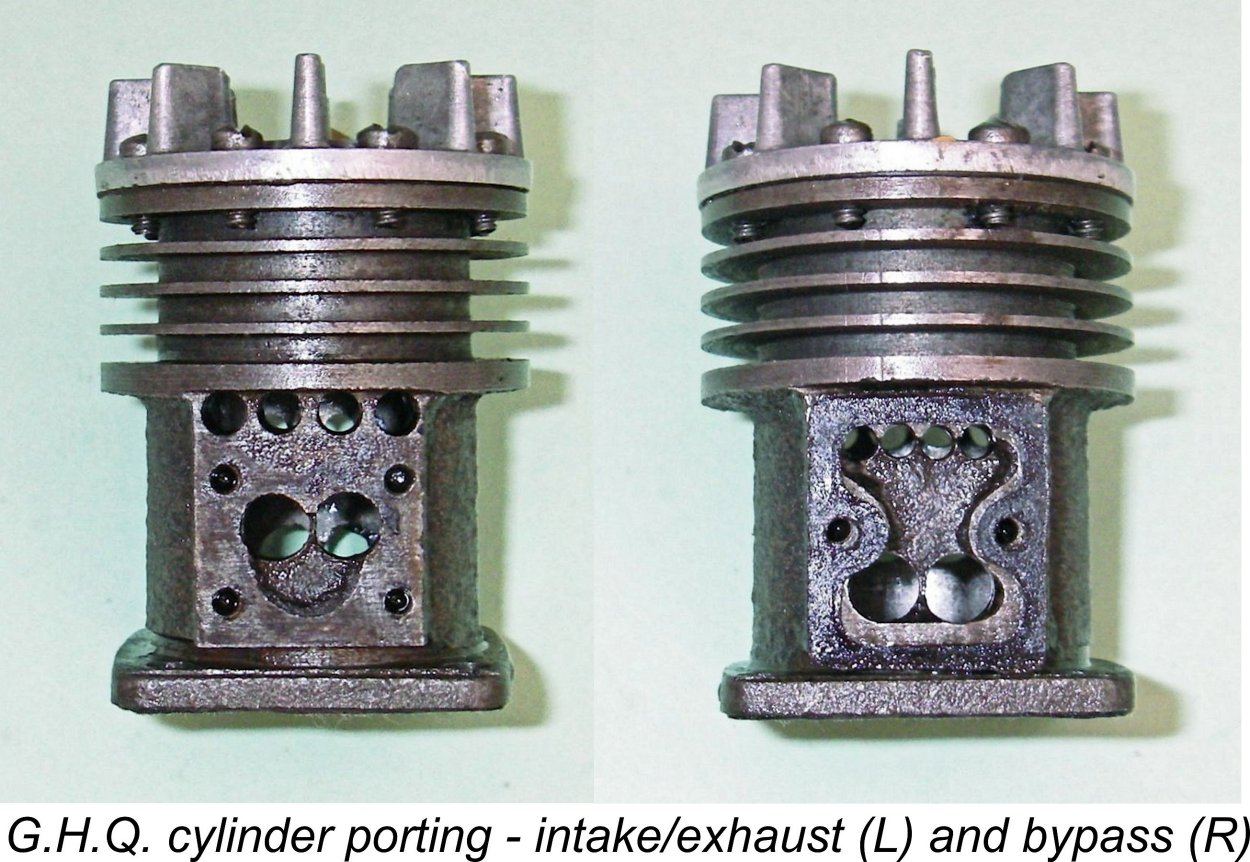

Measurement of the engine’s port timing reveals further evidence to suggest somewhat lacklustre performance expectations. The exhaust ports open at only 95 degrees after Top Dead Centre for a remarkably long exhaust period of 170 degrees - quite inappropriate for a low-speed spark ignition engine like this. The transfer ports open only 15 degrees later for a transfer period of 140 degrees. These look far more like racing engine numbers than those for a low speed sparkie! The transfer situation is further exacerbated by the fact that the previously-mentioned piston ports which supply the lower bypass only start to open about 10 degrees before the transfers. This means that when the transfer ports open, the skirt ports through which they are supplied are well under half way open. The resulting constriction at the bypass entry point will greatly inhibit the power of the initial “puff’ of mixture when the transfer ports first open. An obvious fix would be to extend the piston skirt ports downward so that the lower bypass ports are fully exposed or nearly so when the transfers first open. On the other side of the cylinder, the induction ports open at around 55 degrees before Top Dead Centre for a rather long 110 degree induction period. Once again, this appears to be well in excess of requirements for a low-speed motor of this type - it would almost certainly perform better with a lesser induction period.

Apart from its weight, another major criticism of this piston is the unusually low height of the transfer-side baffle. Because of the very long transfer period, this baffle descends well below the transfer ports at and around Bottom Dead Centre, leaving the transfers facing directly across to the exhausts with no interposing baffle. We would expect short-circuiting of incoming mixture straight out the exhaust to be rather a chronic problem with this motor, once again dampening our performance expectations. At least a reasonable attempt appeared to have been made to fit this cast iron piston to the bore. My example has an adequate, if not perfect, compression seal when oiled. However, beginning in 1937 after the left-over Loutrel components were used up, a stamped steel item having only a rudimentary suggestion of a baffle was substituted. Although it was far lighter, little or no effort appears to have been made to establish a proper fit. As a result, the fit of the revised component was generally very poor indeed, although the odd one did sneak through with a useable fit. It seems to have been this change which resulted in most of the engines refusing to run - both the very poor fit and the absence of any effective baffle militated against such a happy outcome. The cast iron cylinder was secured to the two-part lower crankcase with four screws. The vertically-split crankcase was held together by four nut-and-bolt combinations aligned fore and aft. The rear half of the crankcase incorporated the well-braced integrally-cast backplate, while the front half incorporated the main bearing housing.

Later engines from 1937 onwards featured a reduced main journal diameter of only 5/16 in. This crankshaft was a forging which was rather roughly finished. It had a revised “pear-shaped” crankweb which was far more marginally counterbalanced. This was made possible by the use of the significantly lighter stamped steel piston mentioned earlier. These later engines also incorporated a far skimpier conrod and (later still) a bronze wrist pin, presumably both representing cost-cutting measures. A good indication of which shaft is fitted to a given example is the condition of the forward face of the threaded portion on which the prop is mounted. The earlier 3/8 in. journal component has a nicely machined end with a countersunk center for alignment during machining. The end of the later 5/16 in. dia. component looks as if it has been simply cut off using a set of metal shears!

The cam was formed as a flat in the rear portion of the steel prop driver. It’s important to note that this driver was keyed to the shaft using a tapered steel pin (visible in the attached image) which passed through both the driving disc and the shaft itself. Anyone not realizing this and attempting to pull the driver off the shaft will inevitably do some damage……….. As the above crankshaft comparative image shows, the 1936 engines with their 3/8 in. dia. main journals retained a shoulder at the point where the shaft diameter stepped down to 5/16 in. dia. This took the axial loading on the prop driver caused by tightening the prop. The later engines with their shafts formed at 5/16 in. dia. throughout had no shoulder, leaving the poor little prop driver keying pin to take that loading in addition to resisting the engine’s torque. A guaranteed recipe for early failure .............

The measured bore of the venturi throat is 0.205 in. (5.21 mm). Reference to Maris Dislers’ invaluable Choke Area Calculator confirms that this provides an intake area of 21.319 mm2 in the absence of a spraybar. The minimum speed at which an engine having a displacement of .517 cuin. (8.48 cc) should run using this carburettor while maintaining at least marginal suction is 5,154 rpm. This leads one to suspect that carburetion might prove to be a bit suspect with this engine. The 14 in. dia. cast aluminum prop which was offered as an accessory was very roughly finished. The makers claimed that the engine would turn this prop at 4,500 rpm. The prop had a left-hand pitch for operation in a clockwise direction viewed from the front. This likely led to the legend that the G.H.Q. would only run in that direction. In fact, provided the timer is set appropriately, the engine will run perfectly well in either direction - like any sideport unit not having a Desaxe (laterally offset) cylinder, there’s no structural or operational impediment. All of this having been said, let’s really take a flier here by seeing if we can get one of these brutes to run! The G.H.Q. on Test

Despite the very “odd” port timing documented earlier, the engine sucks and “pops” healthily when flicked over without a plug. An immersion test confirmed that there were no leaks from the crankcase. On the basis of an electrical test, as outlined in my companion article on spark ignition operation, the timer was found to be functioning perfectly. The original Champion plug too proved to be in perfect working condition. The engine thus appeared to have all of the assets required for a successful attempt to actually run it. I could find no reason why it should not do so, although frankly I wasn't expecting much in the way of performance. I was further encouraged by the knowledge that at least one or two examples of the original G.H.Q. have previously demonstrated their ability to run. One of them was written up in “AeroModeller” magazine a few years ago. Moreover, a YouTube video of one of Bill Mohrbacher's G.H.Q. units actually running may be seen here. If those engines could run, so perhaps could mine…………… Reference to contemporary data tables reveals that the recommended prop for the G.H.Q. was a 14x8 item. Not having such a prop on hand, I was forced to use a Top Flite 14x6 wood prop which was the closest thing that I had lying about. For some reason, it just seems more appropriate to test a sparkie on a wood prop ………. This prop should come close to approximating airborne RPM on a 14x8. The original fuel recommendation for the engine was revealing! It would appear that Bernie Winston was well aware of the shortcomings in precision which many of these engines embodied. Recommended fuel was only 2 parts of white gas to one part of SAE 70 oil - an unusually “oily” mixture which would contribute to improved compression seal with a relatively loosely-fitted piston. The clincher was the fact that the injection of a few drops of straight oil into the cylinder was said to result in greatly improved starting. This was pretty much an open admission by Bernie that a somewhat loose piston/cylinder fit might be expected with these engines!

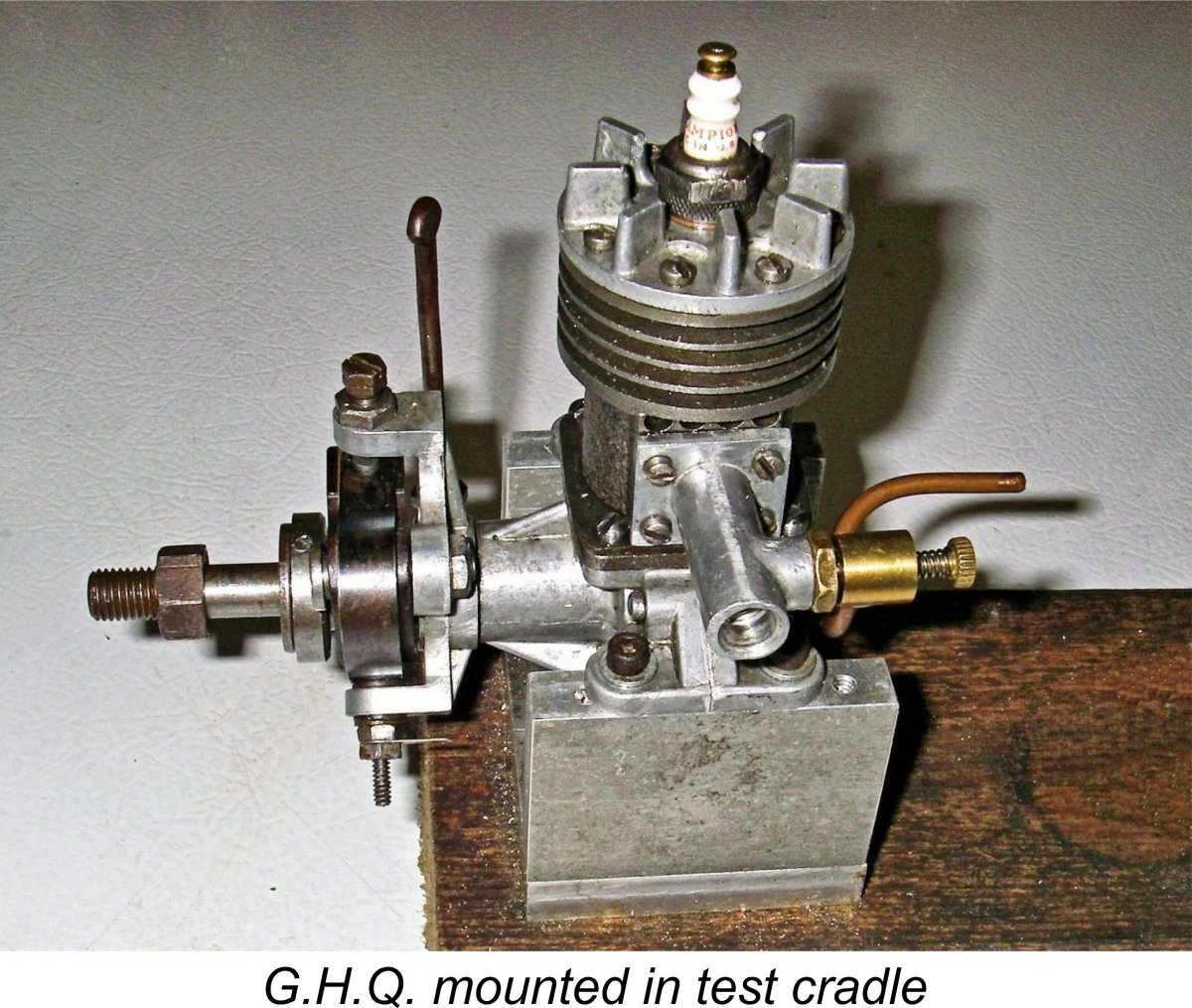

Mounting the engine proved to be a challenge. The presence of the wide central gussets in the middle of the upper mounting lug surfaces precluded the use of my usual universal test stand. I ended up bolting the engine into a custom-made cradle stand which I had created some years ago to test the Bungay Hi-Speed 600 racing engine, drilling and tapping the required extra holes in that component to suit. If you plan to run a G.H.Q., please don't file the mounting lugs to make it fit in your stand - conservation is important! With the 14x6 prop fitted and fuel in the tank, I hooked up the Larry Davidson spark ignition support system (see my related article here) and was all set. I opened the needle one turn, administered a small exhaust prime, switched on the ignition and began flicking (I don't own an electric starter). The unusually low compression ratio was very apparent to the flicking finger, although compression seal with the very “oily” fuel was more than adequate.

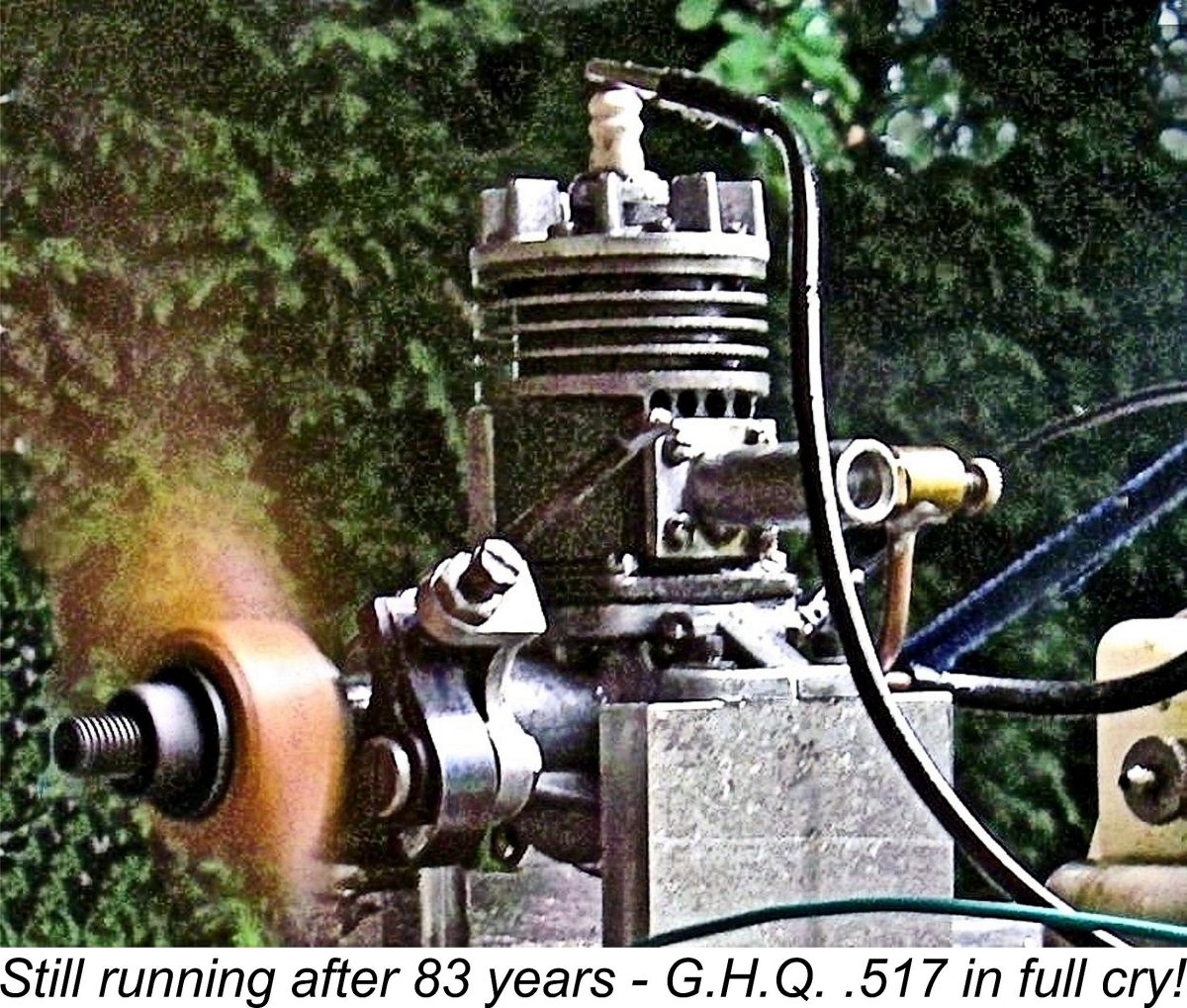

Once running, I was able to fine-tune the needle and advance the timer a little to get a pretty good approximation of a smooth run. There was evidence that carburetion was a bit on the marginal side, as predicted by the calculations summarized earlier. The engine exhibited a slight tendency to “hunt”, while the needle setting for best results proved to be ultra-sensitive. The difference between the four stroke/two stroke break and the engine starving out and stopping was only a fraction of a turn of the needle. This is likely down to the very wide-angle taper on the needle as well as the surface jet arrangement in what appears to be an oversized intake venturi. If I run the engine again in the future, I'll use a fine-thread remote needle valve in the fuel line. The amount of smoke thrown out of the exhaust bore out my prediction that short-circuiting of incoming mixture would be an issue - my nose told me that a lot of unburned fuel was included in the exhaust stream. Even so, liquid exhaust residues remained perfectly clear throughout. As expected, vibration levels were also very noticeable, to the point that I decided not to push the engine past the 4,000 - 5,000 RPM range. A video clip of this engine running may be viewed here.

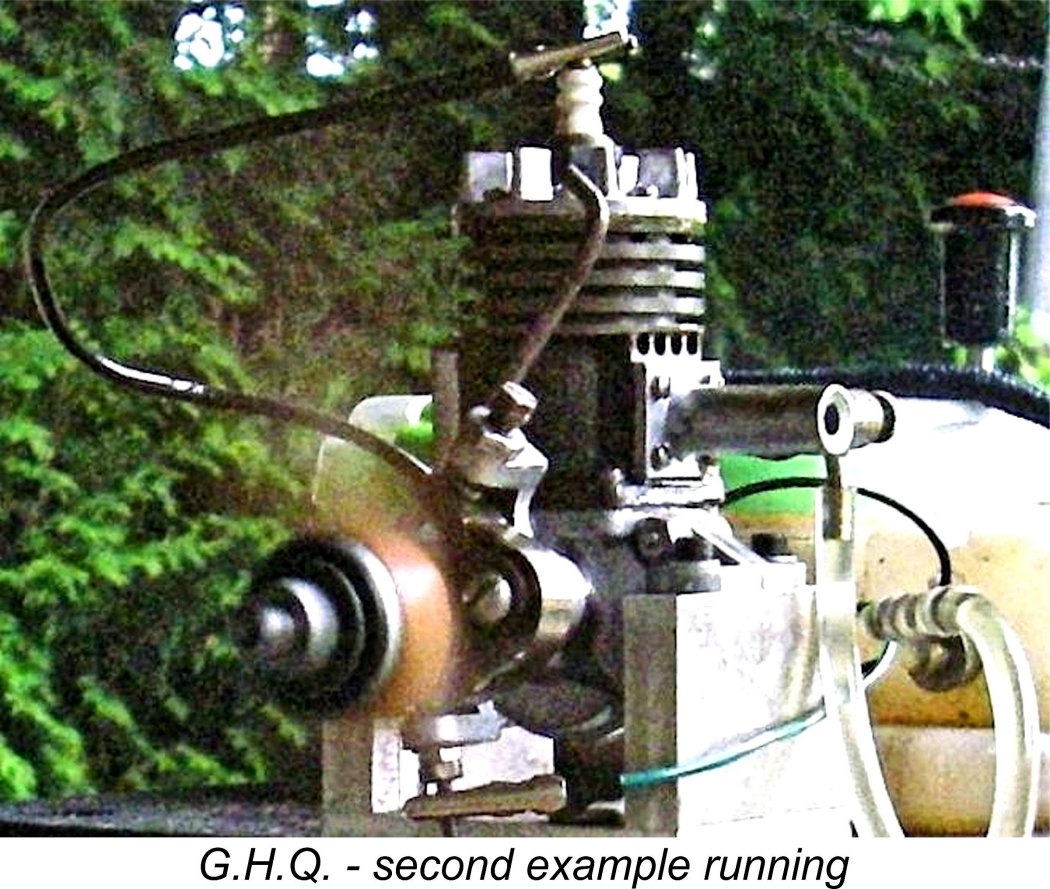

I can see that some examples of the engine might do a little better than this, perhaps even approaching the manufacturer’s claim. The previously-cited YouTube video of Bill Mohnrbacher's G.H.Q. running shows it turning a 13x5 Master airscrew at 5,100 RPM, proving that the engine was indeed capable of beating 5,000 rpm if lightly loaded. However, that's a far lighter load than the 14x6 APC using which I got my best speed of 4,300 RPM. Some time after publishing this article, I acquired a second example of the G.H.Q. featuring a properly fitted cast iron piston. This one was actually better-fitted than my original test example, having a very acceptably-secure compression seal. I set it up in the test stand, finding it to be an excellent starter and a good The fitting of an exhaust deflector like that supplied with the original Loutrel might improve performance a little by minimizing any short-circuiting of exhaust gas. However, I’d have to concede that as they stand, my two tested examples are very good starters and acceptable runners, but lack anything like the power which their very considerable weight would justify. That having been said, there are a few obvious modifications that I would make if I was planning to try flying these engines (which I’m not). Firstly and most importantly, I would make a new closely-fitted piston from Meehanite bar stock. This piston would have a higher crown both to delay the opening of the exhaust and transfer ports and to increase the compression ratio to around 7.5:1. It would also have a higher baffle, which might require me to create the necessary baffle clearance by milling an appropriately-located slot into the underside of the head. I would also have a slightly longer piston skirt to delay the opening of the induction ports by around 10 degrees of crankshaft rotation. Finally, I would lap the new piston to a closer fit in the bore, improving the compression seal. Secondly, I would add a small-bore tubular extension to the fuel jet to bring the discharge point from the venturi wall out to the axial centreline of the venturi. This would likely do much to improve the engine’s carburetion - it would both place the discharge point in the zone of maximum gas velocity and reduce the seemingly excessive intake area a little. Thirdly, I would make a replacement needle having a far finer taper. This would hopefully facilitate the fine adjustment of the fuel mixture during operation. An alternative would be to use a remote needle valve in the fuel line. Fourthly, I would relocate or extend the two piston skirt ports downwards to have them fully uncover the lower bypass entry ports when the transfer ports begin to open. This should greatly improve the transfer phase of the engine’s operating cycle. And finally, I would externally chamfer the lower outer edges of the four small transfer ports in the outer cylinder wall to encourage them to discharge more vertically into the cylinder. This might well improve scavenging somewhat, an improvement which is definitely needed. Taken together, I would expect these modifications to increase peak power output substantially. However, I plan to leave my all-original examples alone. I have no plans to fly the things, but I have proved that both engines start and run OK as they stand. I’m perfectly happy to settle for that! The G.H.Q. in Later Years

Examples in “new” condition still command quite healthy prices from those avid fellows who "just want one” to display as a curio. The oval gas tank and propeller are very hard to locate and original parts to finish an incomplete engine are non-existent. As Bernie Winston said in his 1940 Model Gas Engine Handbook, "your G.H.Q. is a simple mechanical device. When all operating factors are present, it will run". But to get them all "present" is a real chore - things like adequate compression tend to go AWOL! For all the wrong reasons this engine was a legend in its own time, a status which it retains today.

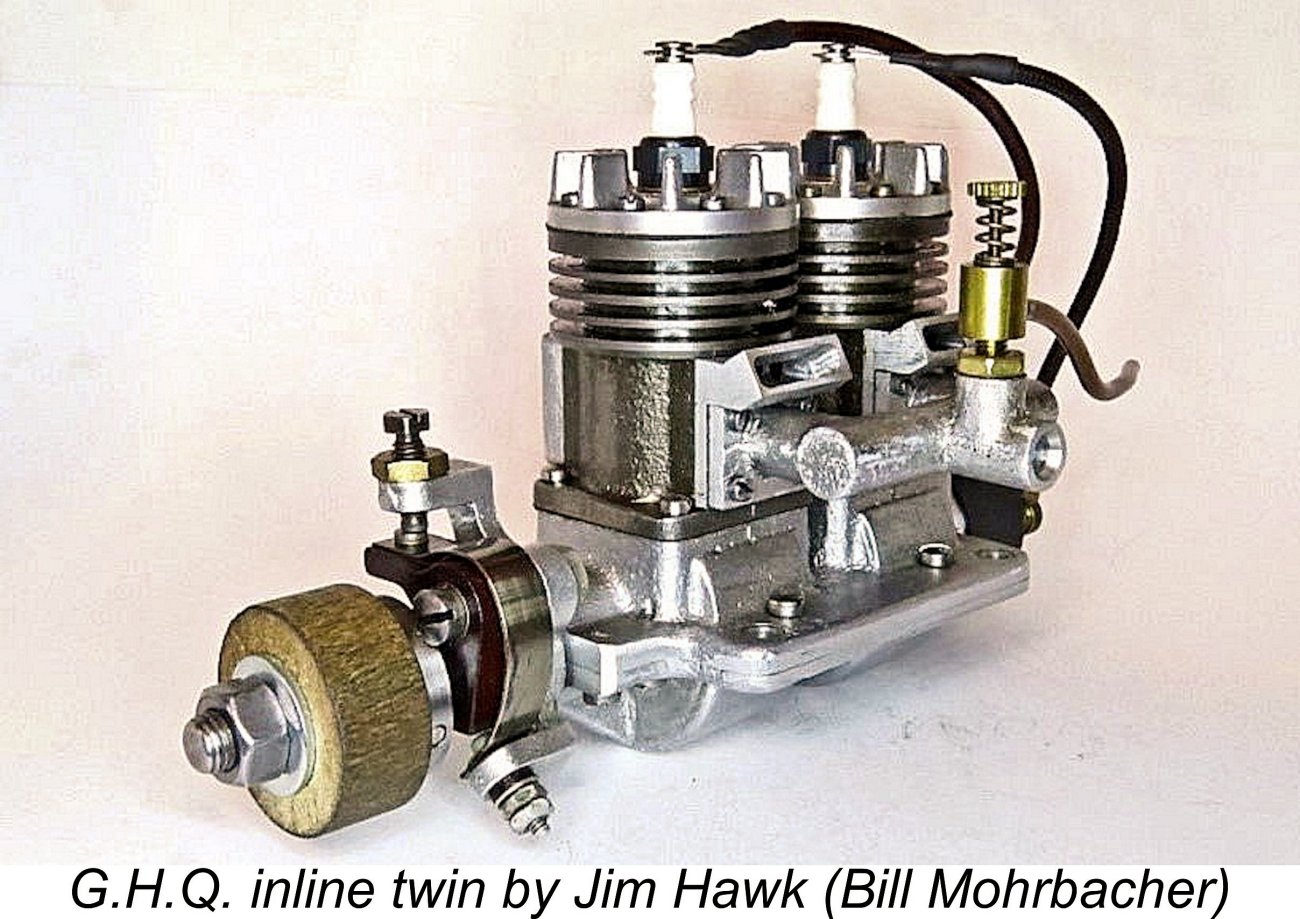

In the early 2000’s, master engine builder Jim Hawk constructed a small number of very interesting multi-cylinder engines based upon the G.H.Q. This project actually has some historical basis in the form of a crankcase pattern for a four-cylinder unit that was reportedly recovered many years ago from the building which had formerly housed the G.H.Q. operation. Although there’s no evidence that a four-cylinder model was ever actually produced by G.H.Q., it appears that serious consideration may have been given to such a project. We’ll never know for sure, but it’s undoubtedly possible that Jim may have carried a still-born factory project through to completion over 80 years later.

This prompted Jim to simplify things by building a couple of inline twins which were based upon the sawn-off front half of a four-cylinder casting. Note the beautiful angled exhaust stacks featured on the twin. Apparently all of Jim’s creations ran well, as demonstrated at a number of MECA gatherings. Congratulations must go out to Jim for this fascinating venture into the realm of “might have been”! A full article about the project by David Zwolak and Jim Hawk appeared in MECA Bulletin 317 - my thanks to David for bringing this to my attention.

There are also several examples of the G.H.Q. flying in England, as reported in "AeroModeller" magazine. However, I have no knowledge regarding whether or not they are doing so following owner intervention. All I know is that they do run well enough to fly a model. Conclusion Having previously written about the Deezil, I must confess to having experienced a certain sense of déjà vu when writing up the present text! The stories of the Deezil and the G.H.Q. follow a remarkably similar pattern, going from a competently-designed and well-made initial rendition to a woeful apology for an engine that was ruthlessly trashed down to a price by a later manufacturer, with no regard for customer satisfaction. Moreover, the same group of individuals - the Winston family - were involved in both cases.

And finally, there’s the infamous latter-day variant of the engine which resulted from the ruthless trashing down of the design by AHC to minimize costs and thereby maximise profits through mass sales, regardless of quality. This is the variant most commonly encountered today. Many if not most of these engines wouldn’t so much as run as supplied, and those that did generally lacked sufficient power to fly a model. It is this variant of the engine which has given rise to the “legend” of the G.H.Q. as arguably the worst commercially-produced spark ignition engine ever to be inflicted upon the American model engine marketplace. It must be said that it appears to richly deserve this epithet! However, as with the Deezil we have to bear in mind that they weren’t all that bad! The original Loutrel and the early 1936 G.H.Q. “Loutrel” models were perfectly good runners which could certainly persuade a model to stagger into the air as long as one’s performance expectations weren’t set too high. By the standards of its day, the G.H.Q. was a basically sound if rather overweight design which had the misfortune to fall into the wrong hands, to the lasting detriment of its reputation. We shouldn’t allow this circumstance to justify the complete dismissal of the engine - it undoubtedly has its redeeming qualities! The fascination with the concept of the “world’s worst” has ensured that the G.H.Q. remains a sought-after collector’s item today. As a bonus, if you manage to get one of the early examples with the cast-iron piston, properly-formed rod and large-diameter shaft, you’ll be getting an engine which will confound many observers by giving a reasonable account of itself on the bench and perhaps (dare I say it?) in a model! Go on - I dare you!! ____________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2019

|

| |

There’s a certain cachet about any given item which enjoys the reputation of being the “world's worst” of its kind. Paradoxically, such a label actually adds to the attraction of the item because it stirs peoples’ curiosity regarding whether or not the object in question was really as bad as its reputation suggests! There’s also the hope that one may get lucky and stumble across the one acceptable example that breaks the pattern. Finally, the title of "world's worst" unquestionably sets the item apart from all the rest. All of these factors tend to result in such items being seen as attractive curios for any collection despite their shortcomings.

There’s a certain cachet about any given item which enjoys the reputation of being the “world's worst” of its kind. Paradoxically, such a label actually adds to the attraction of the item because it stirs peoples’ curiosity regarding whether or not the object in question was really as bad as its reputation suggests! There’s also the hope that one may get lucky and stumble across the one acceptable example that breaks the pattern. Finally, the title of "world's worst" unquestionably sets the item apart from all the rest. All of these factors tend to result in such items being seen as attractive curios for any collection despite their shortcomings. The G.H.Q. has really taken it on the chin over the years, being commonly cited as one of the worst model engines of any type ever released onto the American market. By widespread reputation, very few of them would run at all without significant owner intervention to sort out the engine’s many problems. One of my goals in writing this article is to give myself an excuse to see for myself just how bad this engine really was!!

The G.H.Q. has really taken it on the chin over the years, being commonly cited as one of the worst model engines of any type ever released onto the American market. By widespread reputation, very few of them would run at all without significant owner intervention to sort out the engine’s many problems. One of my goals in writing this article is to give myself an excuse to see for myself just how bad this engine really was!! The G.H.Q. had its origins in a couple of earlier designs by others. In early 1931, a certain Mr. Redfield who worked for the Weiss Mfg. Co. of Torrington, Connecticut designed a .331 cuin. (5.42 cc) engine having its timer mounted at the rear. Weiss only sold plans and castings for this engine, but a Brooklyn-based machinist named Louis P. Loutrel took it upon himself to sell assembled engines built to the Weiss design as well as kits for home construction which included the plans, castings and other required materials. He did so under the company name of Loutrel Specialty Co. of 96 McDonough St., Brooklyn, New York.

The G.H.Q. had its origins in a couple of earlier designs by others. In early 1931, a certain Mr. Redfield who worked for the Weiss Mfg. Co. of Torrington, Connecticut designed a .331 cuin. (5.42 cc) engine having its timer mounted at the rear. Weiss only sold plans and castings for this engine, but a Brooklyn-based machinist named Louis P. Loutrel took it upon himself to sell assembled engines built to the Weiss design as well as kits for home construction which included the plans, castings and other required materials. He did so under the company name of Loutrel Specialty Co. of 96 McDonough St., Brooklyn, New York.  According to Bernie Winston, the Loutrel engines were made in a rented storefront workshop in the notorious 41

According to Bernie Winston, the Loutrel engines were made in a rented storefront workshop in the notorious 41 By all accounts, the Loutrel was a very well-made engine which performed in a fully satisfactory manner by the standards of its day. It was undeniably a rather “agricultural” looking unit, besides which it suffered from the marked disadvantage of having an all-up weight of over 14 ounces minus prop, tank and ignition support system. However, it must be recalled that the engine had very little competition during the early 1930’s, hence possessing a high novelty appeal. As a result, its drawbacks didn't represent a major sales barrier at the time.

By all accounts, the Loutrel was a very well-made engine which performed in a fully satisfactory manner by the standards of its day. It was undeniably a rather “agricultural” looking unit, besides which it suffered from the marked disadvantage of having an all-up weight of over 14 ounces minus prop, tank and ignition support system. However, it must be recalled that the engine had very little competition during the early 1930’s, hence possessing a high novelty appeal. As a result, its drawbacks didn't represent a major sales barrier at the time.

The sale seems to have been consummated by June 1936, when the G.H.Q. “Loutrel” was first advertised by that name in “Model Airplane News” (MAN). It’s interesting to note that at this stage Bernie Winston kept AHC well in the background. In the 1930’s advertising going up to at least 1938, the makers of the engine were cited as the G.H.Q. Model Airplane Co. of 854 East 149

The sale seems to have been consummated by June 1936, when the G.H.Q. “Loutrel” was first advertised by that name in “Model Airplane News” (MAN). It’s interesting to note that at this stage Bernie Winston kept AHC well in the background. In the 1930’s advertising going up to at least 1938, the makers of the engine were cited as the G.H.Q. Model Airplane Co. of 854 East 149 Obviously Bernie wished to apply a name of his own choosing to the version of the engine produced at the behest of AHC. He chose to call it the G.H.Q. on some basis which was unfortunately not recorded, immediately beginning to sell it by that name as AHC’s “house engine”. To this day we do not know what the initials stand for, but suspect "Gas Head Quarters" - a name which definitely has a Winstonian ring to it. Others less kindly disposed have suggested such names as “Grossly Horrible Quality”, "Goes Highly Questionably" and similar, for reasons which will become clear as we proceed!

Obviously Bernie wished to apply a name of his own choosing to the version of the engine produced at the behest of AHC. He chose to call it the G.H.Q. on some basis which was unfortunately not recorded, immediately beginning to sell it by that name as AHC’s “house engine”. To this day we do not know what the initials stand for, but suspect "Gas Head Quarters" - a name which definitely has a Winstonian ring to it. Others less kindly disposed have suggested such names as “Grossly Horrible Quality”, "Goes Highly Questionably" and similar, for reasons which will become clear as we proceed! However, things went downhill from there! The next step was to eliminate the costs associated with casting, machining and fitting the lapped cast iron baffle pistons which formed part of the original Loutrel design. The original Loutrel pistons featured a highly unusual twin-baffle arrangement with baffles on both transfer and exhaust sides and the cylinder porting located to suit. The first casualty was the exhaust side baffle, a change which would have resulted in far earlier opening of the exhaust ports.

However, things went downhill from there! The next step was to eliminate the costs associated with casting, machining and fitting the lapped cast iron baffle pistons which formed part of the original Loutrel design. The original Loutrel pistons featured a highly unusual twin-baffle arrangement with baffles on both transfer and exhaust sides and the cylinder porting located to suit. The first casualty was the exhaust side baffle, a change which would have resulted in far earlier opening of the exhaust ports.  A revised and far skimpier conrod was used with this piston. The wrist pin was also later changed from a well-fitted ground steel tube with brass end pads to a solid bronze component. Other casualties included the piston bosses, which were now far less substantial. The oil retention grooves which had charactertised the cast iron pistons were also omitted.

A revised and far skimpier conrod was used with this piston. The wrist pin was also later changed from a well-fitted ground steel tube with brass end pads to a solid bronze component. Other casualties included the piston bosses, which were now far less substantial. The oil retention grooves which had charactertised the cast iron pistons were also omitted.  Bernie’s persistence in the face of such shortcomings was apparently entirely in keeping with his character - figuring that there was a buck to be made regardless, he pressed on undaunted! He did however hedge his bets to some degree by keeping the AHC connection at arm’s length, continuing to market the engine under the trade-name of G.H.Q. Motors Inc. of 854 East 149

Bernie’s persistence in the face of such shortcomings was apparently entirely in keeping with his character - figuring that there was a buck to be made regardless, he pressed on undaunted! He did however hedge his bets to some degree by keeping the AHC connection at arm’s length, continuing to market the engine under the trade-name of G.H.Q. Motors Inc. of 854 East 149

The following description will necessarily focus upon the single example of the subject motor in my own possession. As will become clear as we proceed, this appears to be one of the better-quality examples made in 1936 shortly after the take-over by AHC, when Louis Loutrel was still involved to some extent.

The following description will necessarily focus upon the single example of the subject motor in my own possession. As will become clear as we proceed, this appears to be one of the better-quality examples made in 1936 shortly after the take-over by AHC, when Louis Loutrel was still involved to some extent.  The cylinder was a massive iron casting with cooling fins turned integrally. All ports were formed by drilling. There were two relatively large overlapping holes for the induction port, with four smaller holes arranged in a row directly above them to serve as the exhaust ports. The twin induction ports were supplied through a die-cast bolt-on manifold, with a fibre gasket being used to seal. No exhaust stack was fitted, although a brass exhaust deflector plate was available as an accessory, as mentioned earlier.

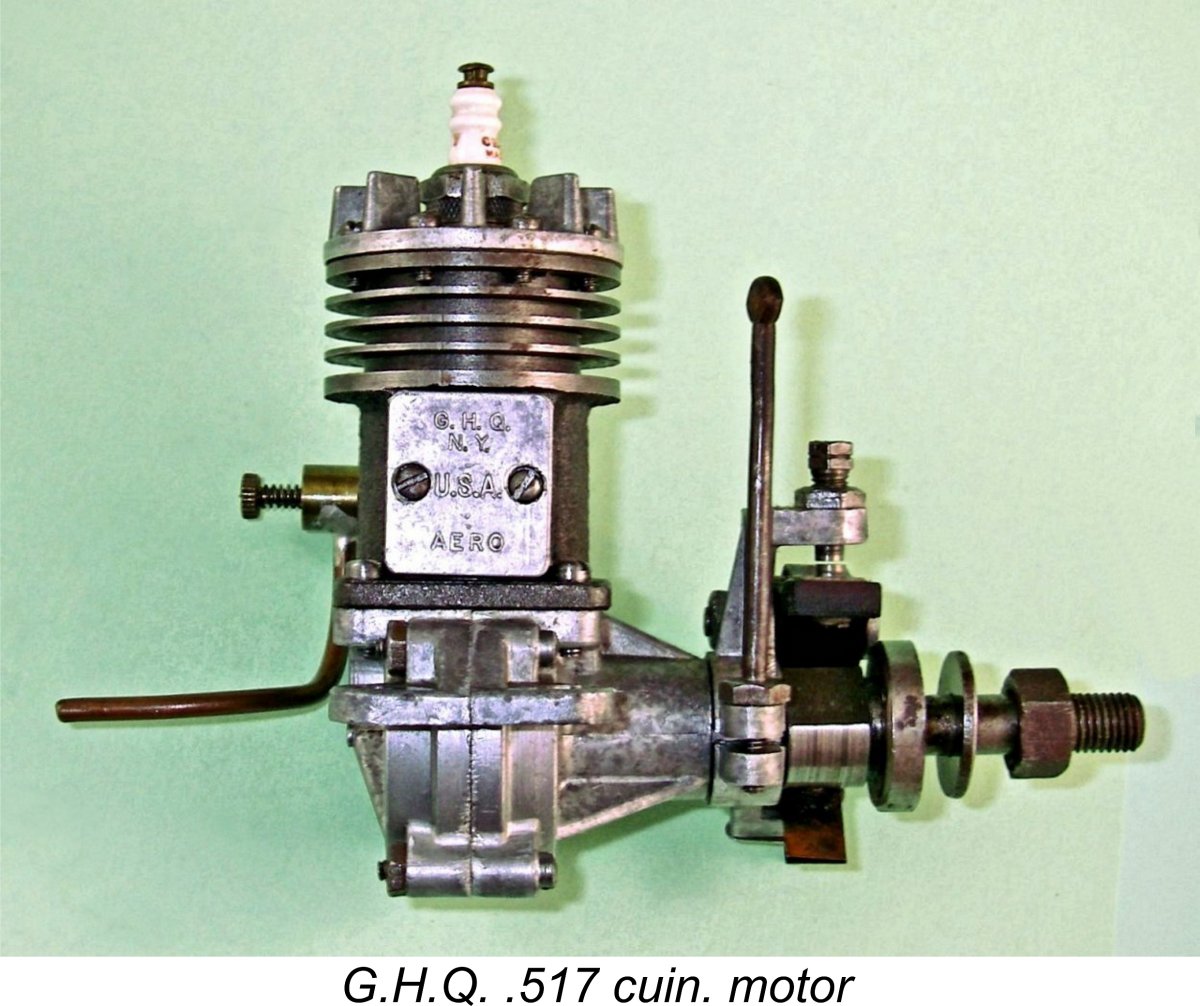

The cylinder was a massive iron casting with cooling fins turned integrally. All ports were formed by drilling. There were two relatively large overlapping holes for the induction port, with four smaller holes arranged in a row directly above them to serve as the exhaust ports. The twin induction ports were supplied through a die-cast bolt-on manifold, with a fibre gasket being used to seal. No exhaust stack was fitted, although a brass exhaust deflector plate was available as an accessory, as mentioned earlier.  On the other side of the cylinder, the bypass passage was open to the atmosphere as cast, being sealed by a die-cast cover plate which was secured with two screws, again with a fibre gasket to seal. This cover plate has the characters “G.H.Q. / NY / U.S.A. / AERO” neatly cast in relief onto its outer surface. The bypass arrangements are interesting in that there is no direct access from the crankcase to the bypass entry. Rather, the lower end of the bypass passage is supplied through two larger holes which align with similarly-sized piston ports drilled through the piston skirt on the bypass side. The transfer ports at the top consist of a row of four smaller holes similar to those provided on the opposite side for the exhaust.

On the other side of the cylinder, the bypass passage was open to the atmosphere as cast, being sealed by a die-cast cover plate which was secured with two screws, again with a fibre gasket to seal. This cover plate has the characters “G.H.Q. / NY / U.S.A. / AERO” neatly cast in relief onto its outer surface. The bypass arrangements are interesting in that there is no direct access from the crankcase to the bypass entry. Rather, the lower end of the bypass passage is supplied through two larger holes which align with similarly-sized piston ports drilled through the piston skirt on the bypass side. The transfer ports at the top consist of a row of four smaller holes similar to those provided on the opposite side for the exhaust. The early models dating from 1936 used a cast iron baffle piston similar to that featured in the original Loutrel but lacking the Loutrel's exhaust-side second baffle. This was machined from a casting which formed the very substantial bosses along with the rest of the component. It was lapped to an acceptable if not outstanding fit in the bore. Oil retention grooves were provided at top and bottom of the outer piston wall. My own example is fitted with such a piston, which weighs all of 20 gm (0.71 ounces)! One might reasonably expect vibration levels to be high ……….

The early models dating from 1936 used a cast iron baffle piston similar to that featured in the original Loutrel but lacking the Loutrel's exhaust-side second baffle. This was machined from a casting which formed the very substantial bosses along with the rest of the component. It was lapped to an acceptable if not outstanding fit in the bore. Oil retention grooves were provided at top and bottom of the outer piston wall. My own example is fitted with such a piston, which weighs all of 20 gm (0.71 ounces)! One might reasonably expect vibration levels to be high ………. Early models (including my own example) had tubular steel wrist pins with brass end pads along with a very sturdy cast bronze conrod with substantial stiffening ribs. The well-machined steel crankshaft on these early models had a main journal diameter of

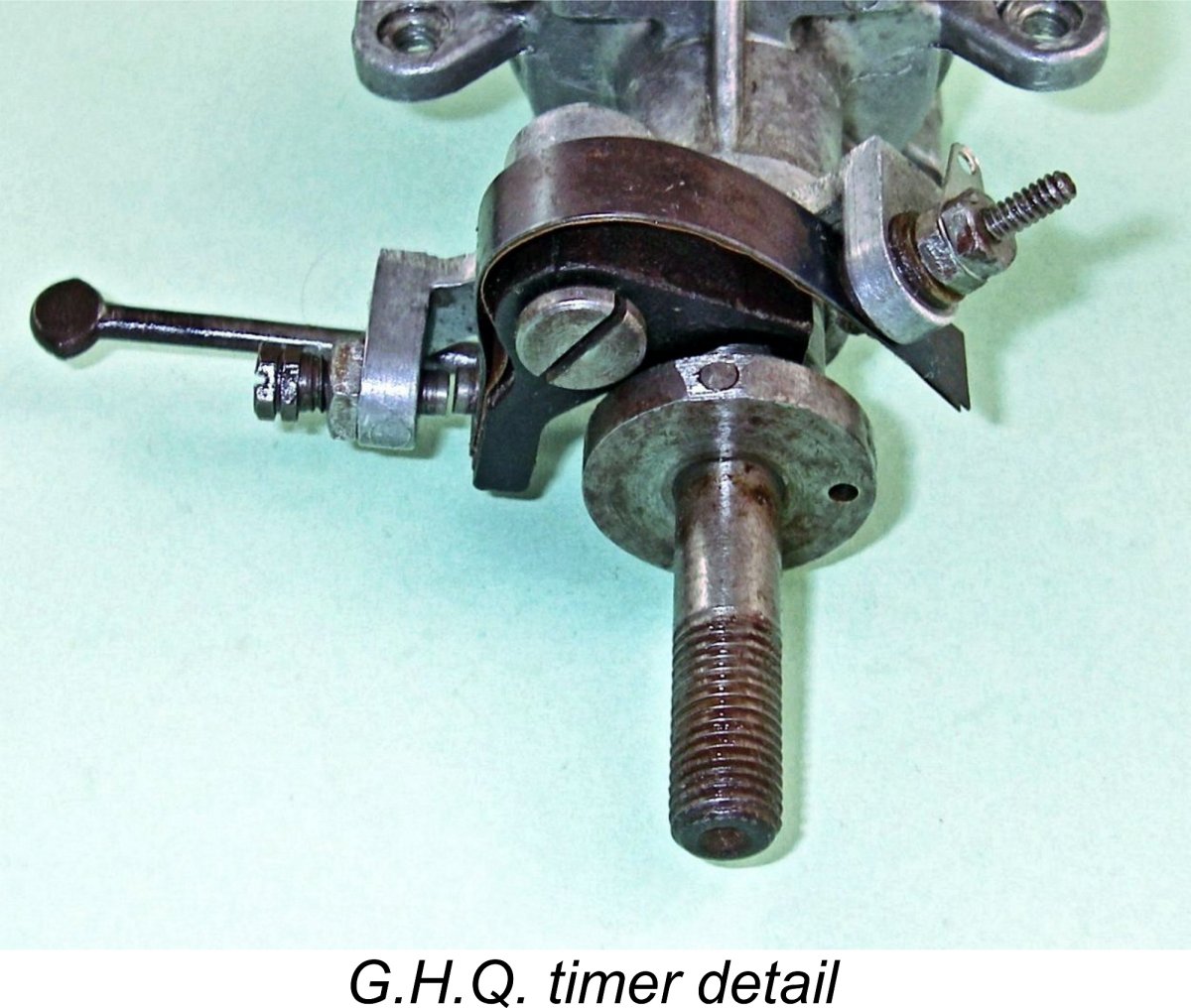

Early models (including my own example) had tubular steel wrist pins with brass end pads along with a very sturdy cast bronze conrod with substantial stiffening ribs. The well-machined steel crankshaft on these early models had a main journal diameter of  A well-made automotive timer having ample provisions for fine adjustment was fitted to the engine. This timer provided a dwell period (the angle of shaft rotation during which the points are closed) of only some 45 degrees - likely quite appropriate for an engine of this specification since it should allow ample real time on each revolution for complete coil saturation. With such a short dwell period, battery drain would be relatively low.

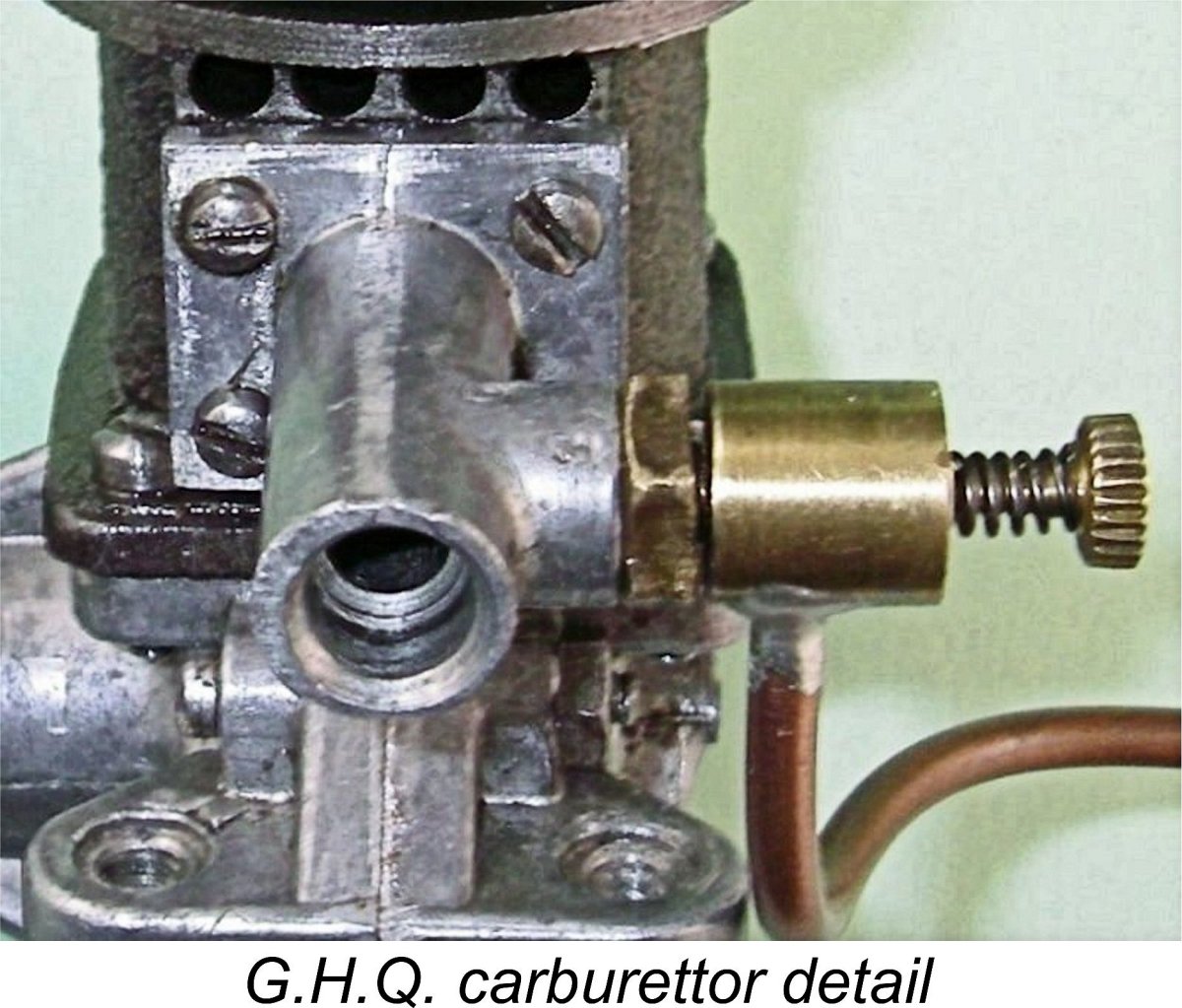

A well-made automotive timer having ample provisions for fine adjustment was fitted to the engine. This timer provided a dwell period (the angle of shaft rotation during which the points are closed) of only some 45 degrees - likely quite appropriate for an engine of this specification since it should allow ample real time on each revolution for complete coil saturation. With such a short dwell period, battery drain would be relatively low.  Fuel mixture control was provided by a needle valve of somewhat unusual configuration. A brass fuel jet was threaded at a right angle into the side of the cast light alloy intake manifold, with the delivery nozzle extending a very little way into the venturi throat from the side. This jet was secured in position by a lock nut. The copper fuel line entered the outer body of this component from the side at right angles, and fuel metering was accomplished using a spring-tensioned needle which was aligned co-axially with the fuel nozzle. A look at the accompanying illustrations should clarify this description. The engines were supplied with an extended length of copper fuel line which could be trimmed or bent into any desired shape to conform to the fuel supply arrangements used.

Fuel mixture control was provided by a needle valve of somewhat unusual configuration. A brass fuel jet was threaded at a right angle into the side of the cast light alloy intake manifold, with the delivery nozzle extending a very little way into the venturi throat from the side. This jet was secured in position by a lock nut. The copper fuel line entered the outer body of this component from the side at right angles, and fuel metering was accomplished using a spring-tensioned needle which was aligned co-axially with the fuel nozzle. A look at the accompanying illustrations should clarify this description. The engines were supplied with an extended length of copper fuel line which could be trimmed or bent into any desired shape to conform to the fuel supply arrangements used. The sole example of the G.H.Q. that I’ve retained over the years in my own collection appears to be one of the better early examples dating from 1936. This opinion is based upon the fact that it has a sturdy well-ribbed bronze conrod (as opposed to the puny rod fitted from 1937 onwards) and a full-disc counterbalanced crankweb. It also incorporates a reasonably well-fitted cast iron baffle piston which provides a more than adequate compression seal for starting and running. In addition, it features a centre in the front end of the nicely finished

The sole example of the G.H.Q. that I’ve retained over the years in my own collection appears to be one of the better early examples dating from 1936. This opinion is based upon the fact that it has a sturdy well-ribbed bronze conrod (as opposed to the puny rod fitted from 1937 onwards) and a full-disc counterbalanced crankweb. It also incorporates a reasonably well-fitted cast iron baffle piston which provides a more than adequate compression seal for starting and running. In addition, it features a centre in the front end of the nicely finished  Wishing to give the old beastie every chance, I brewed up a small batch of fuel containing 2 parts of Coleman camp fuel (naptha - a white gas equivalent) to one part of SAE 60 mineral oil (I use AeroShell 120). This should be a close approximation of the manufacturer’s recommended blend. Some may quibble about my use of SAE 60 oil instead of the recommended but now hard-to-get SAE 70 lubricant, but advances in lubricant technology since 1936 have resulted in today's premium SAE 60 aero-grade oil being a far superior lubricant to any SAE 70 product that was available back then.

Wishing to give the old beastie every chance, I brewed up a small batch of fuel containing 2 parts of Coleman camp fuel (naptha - a white gas equivalent) to one part of SAE 60 mineral oil (I use AeroShell 120). This should be a close approximation of the manufacturer’s recommended blend. Some may quibble about my use of SAE 60 oil instead of the recommended but now hard-to-get SAE 70 lubricant, but advances in lubricant technology since 1936 have resulted in today's premium SAE 60 aero-grade oil being a far superior lubricant to any SAE 70 product that was available back then.  Somewhat to my surprise, I didn't have to flick for long! The 83 year old G.H.Q. proved to be a remarkably easy starter. It turned out that a couple of choked flicks were often the only preliminaries to a prompt start, although I did occasionally have to resort to a small exhaust prime when choking alone failed to produce any results. However, the engine may be fairly described as a very good starter, retaining this characteristic throughout my testing.

Somewhat to my surprise, I didn't have to flick for long! The 83 year old G.H.Q. proved to be a remarkably easy starter. It turned out that a couple of choked flicks were often the only preliminaries to a prompt start, although I did occasionally have to resort to a small exhaust prime when choking alone failed to produce any results. However, the engine may be fairly described as a very good starter, retaining this characteristic throughout my testing. The best that I could get out of the G.H.Q. on the Top Flite 14x6 wood prop was a rather disappointing 4,100 RPM. This does not provide any support for the manufacturer’s claim that the engine would turn a 14x8 prop at 4,500 RPM. I did a little better using a somewhat more efficient APC 14x6, on which I saw 4,300 RPM. However, this only equates to around 0.092 BHP at that speed - not even close to the 0.200 BHP claimed by the manufacturer. The engine was moving a fair bit of air and might conceivably get a model into the air, but not much more than that.

The best that I could get out of the G.H.Q. on the Top Flite 14x6 wood prop was a rather disappointing 4,100 RPM. This does not provide any support for the manufacturer’s claim that the engine would turn a 14x8 prop at 4,500 RPM. I did a little better using a somewhat more efficient APC 14x6, on which I saw 4,300 RPM. However, this only equates to around 0.092 BHP at that speed - not even close to the 0.200 BHP claimed by the manufacturer. The engine was moving a fair bit of air and might conceivably get a model into the air, but not much more than that. runner within the limitations imposed by the G.H.Q.'s antiquated design. In performance terms it more or less exactly duplicated the numbers measured during the earlier test. If nothing else, this experience proved that the performance put up by my initial test subject was no fluke!

runner within the limitations imposed by the G.H.Q.'s antiquated design. In performance terms it more or less exactly duplicated the numbers measured during the earlier test. If nothing else, this experience proved that the performance put up by my initial test subject was no fluke!  In spite of all the negative commentary recorded above, the "charm" of this engine is such that "good" examples (if one may use that term!) remain much coveted collectibles. Rather like the infamous Deezil in that respect! There’s something irresistible about the “world’s worst” in any field - if the G.H.Q. was really the world’s worst spark ignition motor, every collector’s shelf should have one as a conversation piece if nothing else! Moreover, it’s a documented fact that some of them did run - one can always hope to get lucky, as I did!

In spite of all the negative commentary recorded above, the "charm" of this engine is such that "good" examples (if one may use that term!) remain much coveted collectibles. Rather like the infamous Deezil in that respect! There’s something irresistible about the “world’s worst” in any field - if the G.H.Q. was really the world’s worst spark ignition motor, every collector’s shelf should have one as a conversation piece if nothing else! Moreover, it’s a documented fact that some of them did run - one can always hope to get lucky, as I did!

The pattern eventually came into the possession of George Helmer, who made some 8-10 castings from it. Most of these were passed along to Jim Hawk, who subsequently produced both twin cylinder and four-cylinder models using G.H.Q. cylinders in both instances. Four or five examples of the four cylinder model were constructed, but the production of the four-throw crankshaft was found to be a rather onerous task.

The pattern eventually came into the possession of George Helmer, who made some 8-10 castings from it. Most of these were passed along to Jim Hawk, who subsequently produced both twin cylinder and four-cylinder models using G.H.Q. cylinders in both instances. Four or five examples of the four cylinder model were constructed, but the production of the four-throw crankshaft was found to be a rather onerous task.

In parallel with the evolution of the Deezil, there are in essence three distinct versions of the basic G.H.Q. design. First, there’s the Loutrel .517 cuin. model, which was a very well executed albeit heavy design which performed well enough to attract considerable interest, to the point that Louis Loutrel was unable to keep up with demand. Secondly, there’s the 1936 G.H.Q. manufactured immediately following the take-over of the design by AHC. This appears to have followed the original Loutrel design fairly closely, even using some Loutrel parts in the early stages. Many if not most of these were capable if not spectacular performers. My two test engines are examples of this variant.

In parallel with the evolution of the Deezil, there are in essence three distinct versions of the basic G.H.Q. design. First, there’s the Loutrel .517 cuin. model, which was a very well executed albeit heavy design which performed well enough to attract considerable interest, to the point that Louis Loutrel was unable to keep up with demand. Secondly, there’s the 1936 G.H.Q. manufactured immediately following the take-over of the design by AHC. This appears to have followed the original Loutrel design fairly closely, even using some Loutrel parts in the early stages. Many if not most of these were capable if not spectacular performers. My two test engines are examples of this variant.