|

|

The AHC Diesel – the One That Never Was

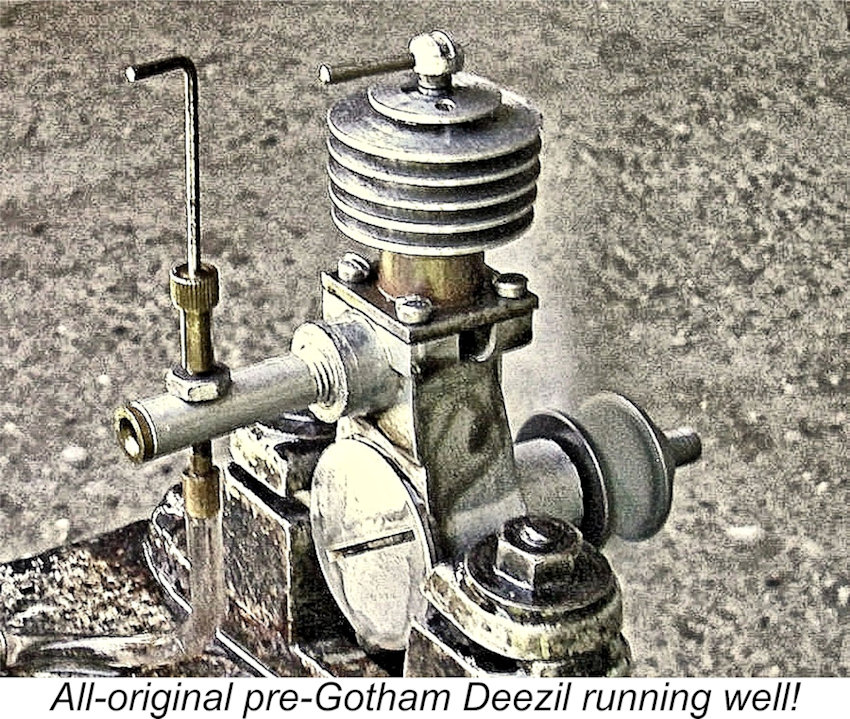

In the case of the Deezil, the engine made it into the marketplace and was sold in very large numbers. However, apart from the very first examples, which were very well made, the vast majority exhibited an appalling disregard for acceptable quality standards – in fact, most of them wouldn’t even run! Consequently, the Deezil enjoys the dubious distinction of being generally regarded as probably the worst commercial model diesel ever inflicted upon the modelling public, and deservedly so, at least in the case of the trashed-down later examples which constitute the majority. By contrast, the AHC diesel failed to make the grade because it never actually achieved full production status. As a result, the AHC has been largely forgotten by the majority of model engine enthusiasts. We are greatly indebted to the now-disbanded Motor Boys International group for going well beyond the mere call of duty to preserve a tangible record of this very elusive engine through the creation of very faithful replicas plus a few interesting derivatives. I’ll take full advantage of their efforts in the following article. For the convenience of my valued readers, when I set about transferring the Deezil and AHC stories to my own website to prevent their loss as the un-maintained MEN site slowly deteriorates, I elected to separate the two models into distinct articles. My revised article on the Deezil appeared on this website in March 2019. I do not intend to repeat most of that information here – those interested in the Deezil are referred to the companion article. It's a fascinating story in its own right, with a few unexpected twists! The present article will focus on the AHC. In The Beginning

1931 was a challenging year for the establishment of a new business based upon the selling of "luxury" items such as modelling goods. The Great Depression was in full swing at the time and an unemployment level of well over 20% along with reduced wage levels meant that discretionary spending in the USA was highly constrained. Nevertheless, the new business weathered the storm and became very successful, eventually blossoming into one of North America's largest retail and world-wide mail order modelling businesses. Few aeromodellers who were active during the Golden Years of the hobby did not deal with AHC at one point or another - I myself was a regular mail-order customer from outside the USA. AHC was established as a joint proprietorship by the four Winston brothers, each of whom had a share in the business. This arrangement was still in effect when America was drop-kicked into WW2 by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941.

Both of the military Winstons survived the war and returned to New York, presumably expecting to resume their involvement with AHC, which was still very much a going (and growing) concern. However, this is where things began to get a bit rocky - the stay-at-homes refused to let them back in! It's not known whether or not there had been any prior understanding, formal or otherwise, that the military brothers would be re-admitted upon their return, but if any such agreement did exist it was not honoured.

Whatever the emotions involved, the outcome of this chain of events was an immediate move by the rejected brothers to develop their own model supply business in direct competition with their AHC siblings. They established the Gotham Hobby Corporation, which traded from premises at 107 E. 126th Street in New York City. It's extremely difficult to resist the conclusion that a desire to beat their brothers at their own game may have played a role in this matter. They subsequently took over the Deezil design which had previously been produced in modest numbers to a very good standard by an unknown maker, progressively trashing it down to the dysfunctional paperweight as which it is best remembered. But that’s another story which has been recounted elsewhere. Returning to our main thread, it’s now time to look at the sequence of events leading to the development, if not the marketing, of the AHC diesel. The AHC Model Engine Lines The AHC diesel was by no means AHC’s initial entry into the model engine field. The company was an early participant in that field, choosing from the outset to compete strictly on the basis of ultra-low prices, with factors such as performance and quality taking a seat in the very back row. The prevailing philosophy appears to have been that if you price an engine low enough, you'll make money because people will buy it by the truckload regardless of any shortcomings. Moreover, if the thing fails to give satisfaction, it will be consigned to the rubbish bin with little concern or recrimination against the makers simply because of the minimal investment which it represents. The main driving force behind the AHC operation appears to have been Bernie Winston. Some years ago, a post appeared on a widely-read modelling forum from an individual who worked at AHC during the late 1940's and early 1950's. He remembered Bernie Winston as a likeable chap who was always very pleasant to interact with but at the same time was not averse to making a buck by whatever legal means lay to hand, including the marketing of basically "junk" engines! He did credit Bernie Winston with being among the pioneers of discount mail-order marketing based on high-volume selling, which is undoubtedly a fair assessment. Another individual posting on a different thread recalled Bernie Winston as being a genuine enthusiast with a sincere interest in the ongoing development of model aviation. Reportedly he bought every book on the subject that he could lay hands upon, taking great pleasure in discussing the topic with all and sundry. This individual also recalled that Bernie was a great guy to get along with, although he admitted that AHC's business strategies perhaps reflected another side of Bernie's character.

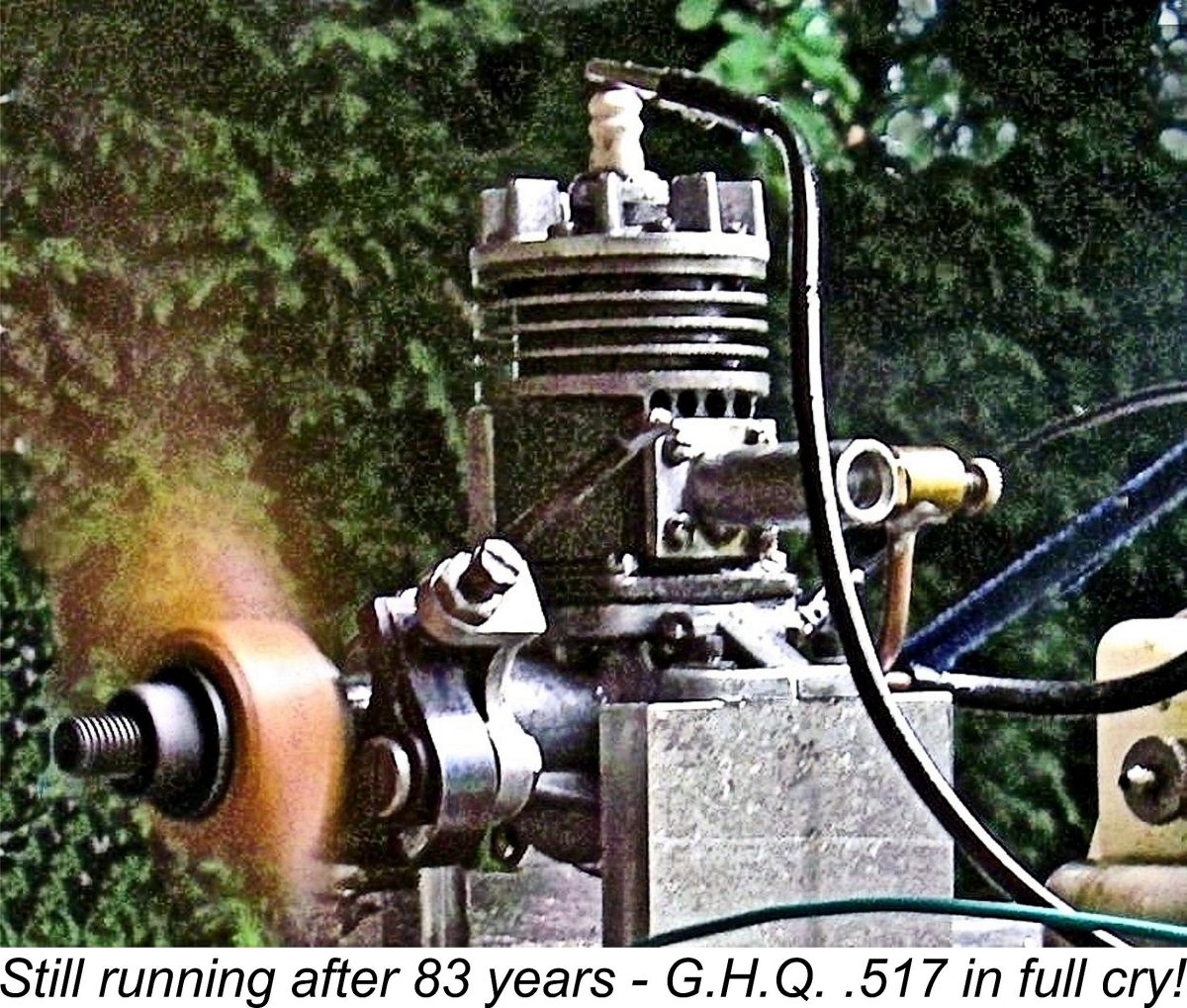

Very few people ever got an unmodified standard latter-day G.H.Q. to run - some significant intervention to correct a number of serious design and construction issues was almost always required. However, a few of the early examples which used left-over Loutrel components did run, albeit at rather dismal levels of performance. I’ve covered the rather sad story of the Loutrel and G.H.Q. models elsewhere.

Following the conclusion of hostilities, AHC wasted no time in expanding their participation in the model engine market with a series of engines which upheld the established G.H.Q. tradition by combining amazingly low prices with a breathtaking absence of quality! In fact, they were so marginally serviceable that they and others like them have acquired the name of "slag engines" among latter-day collectors.

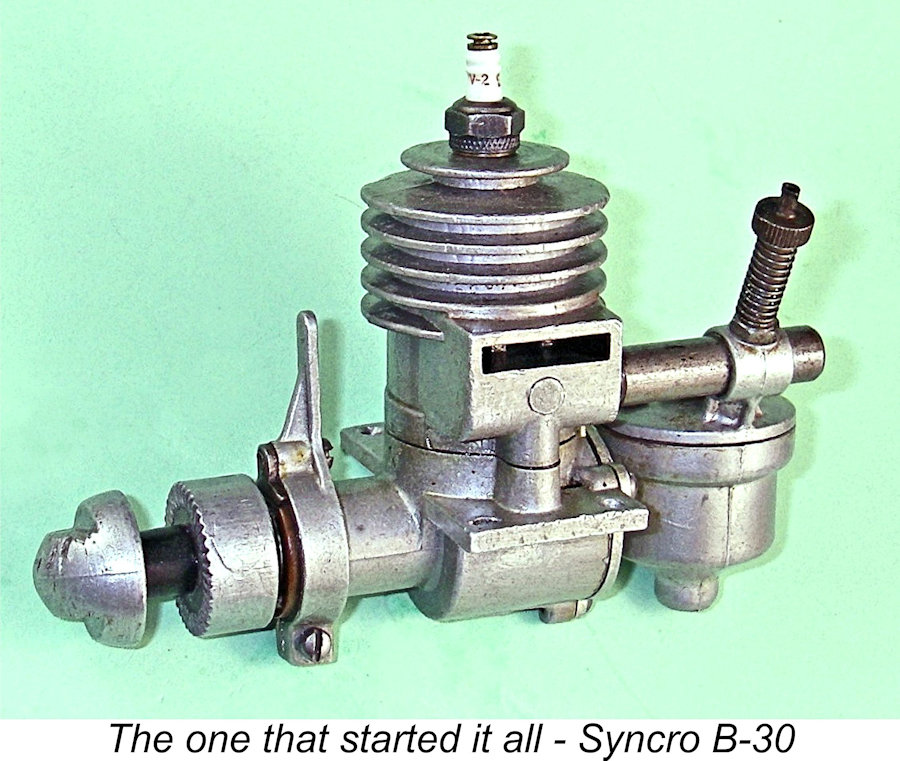

In fairness to AHC, it has to be admitted that they didn't invent the slag engine concept. This unique approach to model engine construction actually had its roots in pre-war Detroit, where the Syncro B-30 slag engine first appeared in 1940. This was soon joined by the 1941 Rogers and Pioneer Brown slag engines from Philadelphia. However, after the war AHC quickly recognized the commercial potential of this highly questionable technology, becoming one of its most prolific exponents.

The illustrated example of the Super Thor "B" is one of the better ones. It has been run (proving that some of them did run!) and still has excellent compression, but I wouldn't bet on it lasting long in service! That said, the Society of Antique Modellers (SAM) has run a number of contests exclusively for models powered by slag engines, with good entries and many successful flights. So not all of these engines were completely useless, at least in the short term.

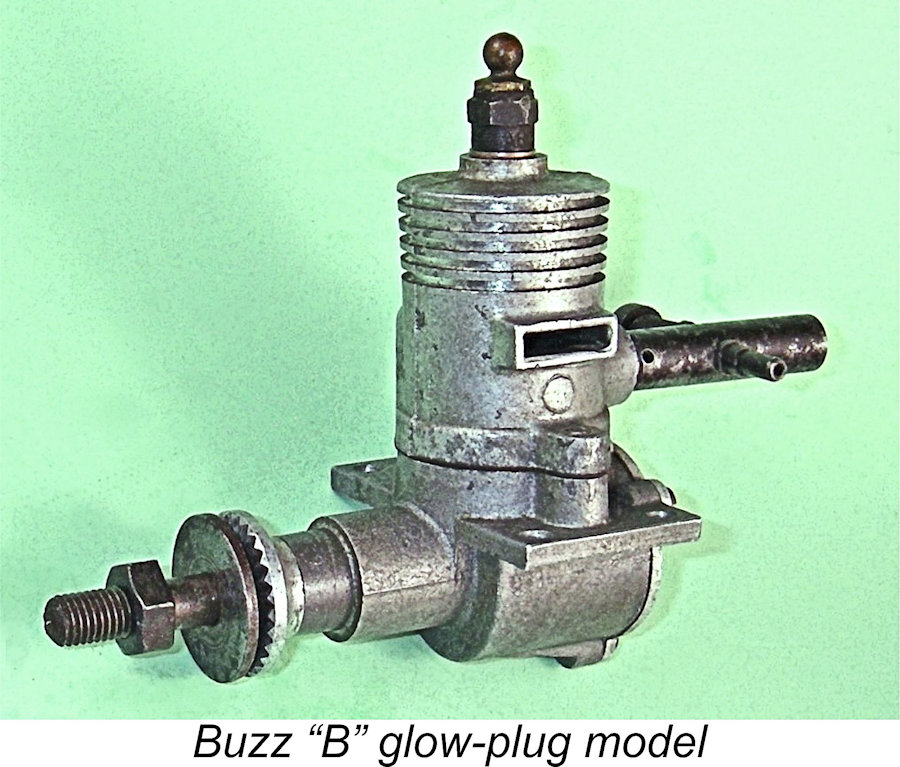

The Buzz engines continued to be manufactured for AHC by Judson. It must be admitted that they displayed somewhat higher overall quality than their predecessors, although they remained true to the slag engine genre. They appeared in four displacement There was also the Buzz CO2 unit, a tiny 0.0052 cuin. engine which ran on compressed carbon dioxide. This was made for AHC by Campus Industries and was essentially identical to the manufacturer's own Campus "Bee" model. The most intriguing model offered by AHC was a .045 cuin glow-plug motor known as the "Glo-Wee". This was advertised in 1949 along with the Buzz glow-plug models, but no examples or images are known to exist today. It appears highly likely that production never got off the ground. We don't even know whether or not it was another slag engine. A detailed article on the slag engines, including the AHC models, will appear on this website in due course. It's actually a fascinating story in its own right! The Genesis of the AHC Diesel Now at last we get down to the central subject of this article! Following the conclusion of WW2, American servicemen returning from the European theatre brought back examples of a new type of model engine which had been developed in Europe during the war years. These engines ran without any ignition support system, a concept which must have really startled a lot of folks! In this manner, the model diesel reached American shores for the first time. As of late 1945 when these engines first showed up in America, the commercial miniature glow-plug was still over 2 years in the future. Accordingly, the diesel offered the sole alternative to spark ignition then available. The great advantage of the diesel principle was the fact that its use eliminated the heavy, parasitic and often unreliable ignition system required by the spark ignition types. A number of American manufacturers quickly recognized the commercial potential of such a power-plant.

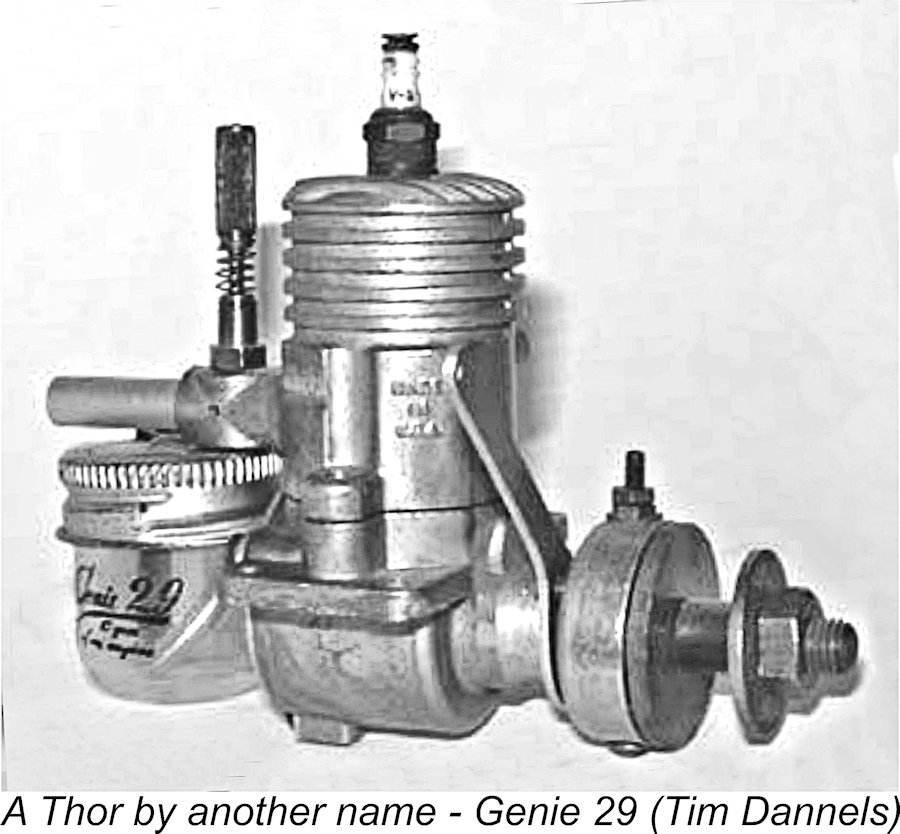

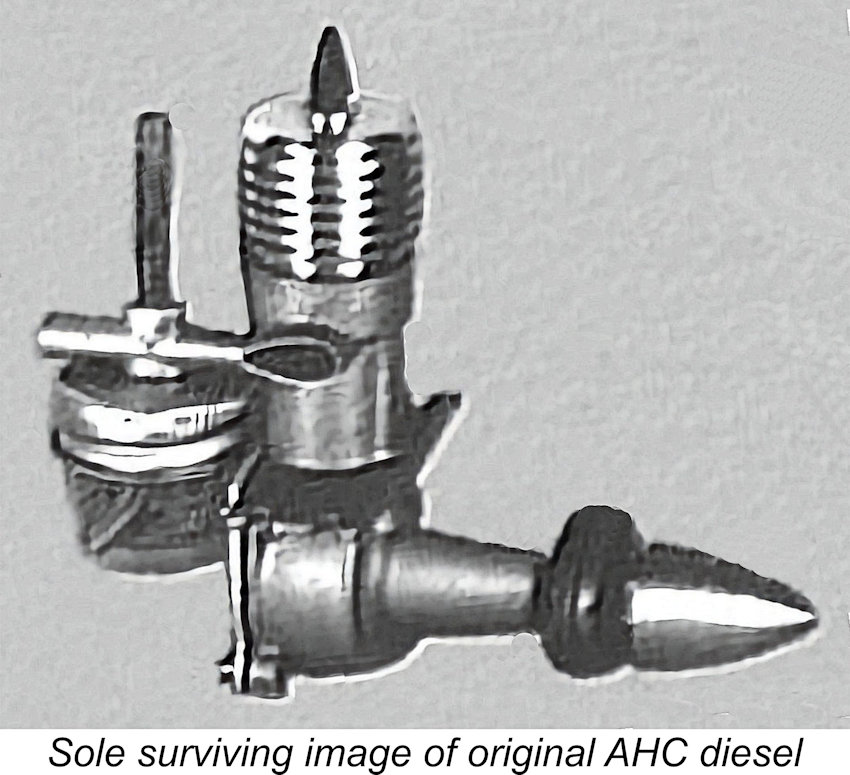

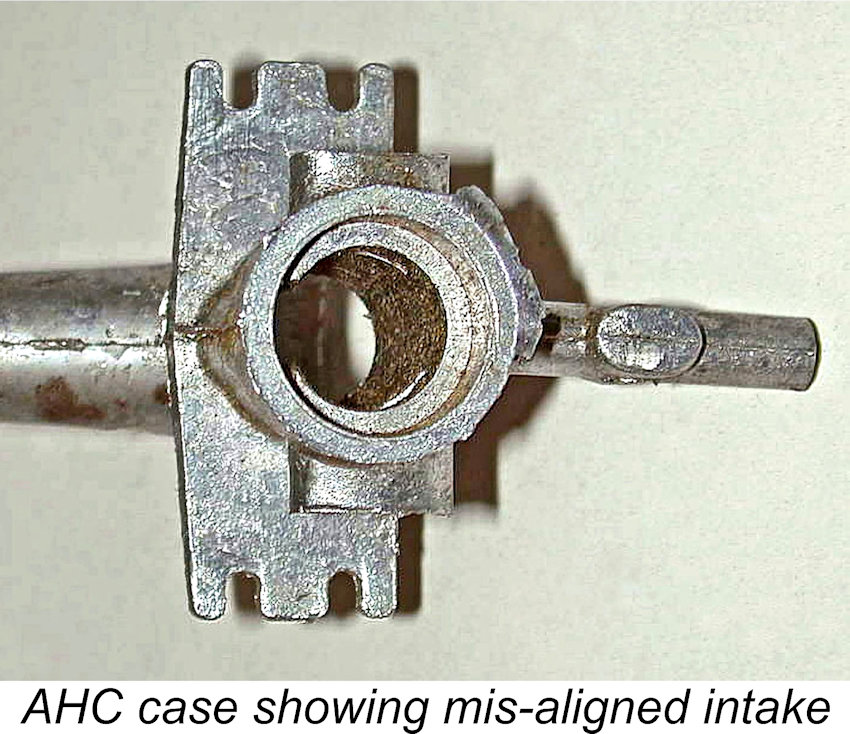

Given Bernie Winston's previously-noted interest in developments connected with model aircraft, AHC must have become aware of diesels as quickly as any of their competitors. It appears likely that they commenced the development of a 0.12 cuin. (2 cc) diesel model at some point in 1946. The design which they came up with was a completely conventional long-stroke side-port compression ignition engine of its period. Its unique features were the complex die-cast crankcase with twin teardrop exhaust stacks; a long and rather delicate integrally-cast venturi; somewhat fragile beam mounting lugs with open-ended mounting holes; and a backplate that was designed to be stamped from 1/16 in. aluminium sheet. According to the AHC entry in Tim Dannel's indispensable “American Model Engine Encyclopedia” (AMEE), the AHC diesel was scheduled for release in production form during 1947. The impending arrival of the engine was duly announced, but for reasons which remain somewhat conjectural it never actually put in an appearance on the market. So far, it's all familiar - there were a lot of still-born model engines which were designed and announced but subsequently disappeared without trace. In the case of the AHC, matters went somewhat further than this. It The sole surviving image of an original AHC diesel prototype shows that this example differed in certain details from the replicas produced years later by Ron Chernich and others. It seems to have used a tank and surface jet needle valve set-up that was borrowed directly from the contemporary Genie 29 slag engine. Apologies for the poor quality of this illustration, but it's the only one that we have! In creating his replicas, no attempt was made by Ron to duplicate the Genie tank setup – hence, his units had no tanks, without which the engine actually looks a little “lost”. They do however use original Genie needles! The example illustrated at the head of this article has a tank made by my mega-talented mate Peter Valicek, of whom more below........ That was as far as the project went in AHC's hands - the project was permanently shelved despite a considerable investment having already been made in dies and castings. Given Bernie Winston's penny-pinching business approach, there must surely have been some compelling reasons for the abandonment of this investment. It's entirely possible that the test results in prototype form showed the engine to be basically uncompetitive in performance terms - latter-day test results certainly support this possibility, as we shall see. However, a number of other factors may well have been involved, as ably documented by the late Roger Schroeder in his article "What Happened to the AHC Diesel?" which appeared in Volume 26, No 4, Issue 148 of the “Engine Collector's Journal". Roger's broad conclusion was that the engine had embodied an assemblage of poor design choices, the recognition of one of which simply highlighted the next in domino fashion. For starters, the cases were cast from the genuine "pot metal", a material of deservedly evil reputation which is both weak and notoriously Over and above the material issue, there's ample evidence that a substantial proportion of the original AHC crankcase castings were seriously flawed even before any attempt was made to cut metal. Many appear to have been removed from the die at such a high temperature that the integrally-cast intake tube warped badly out of line when it cooled. The crankcase in the attached illustration displays this problem. There were also a fair number of cases on which the metal did not flow fully into the cavity which formed the right-hand exhaust stack, leaving that feature incomplete - one of my own replica examples exhibits this flaw. It's actually possible that there were depths of crudity below which even AHC were not prepared to descend! Even if the castings had all been useable and had survived the machining operations, the crankcase design itself left much to be desired in several areas. Firstly, the front face of the crankcase was set too far back to allow the crankweb to be located in the necessary position to align the con-rod centrally on the bore axis viewed from the side. This forced the use of a very thin crankweb. Even so, the con-rod column was still forced to run to the rear of its ideal central location along the bore axis, thus imposing a fore-and-aft rocking couple upon the piston. It would have taken a relatively minor amendment to the pattern to deal with this issue, but as-cast it can't be done. The designer clearly recognized this problem (if indeed he did recognize it!) only after the investment in the 1000 cases had already been made. Consequently, they were stuck with a skinny crankweb along with a rod that was constrained to run off its ideal axis. A further issue affecting the rod was the fact that the as-cast case did not provide sufficient clearance to accommodate the side-swing of the rod around mid-stroke. Ron Chernich found it necessary to use a Dremel tool to create a pair of channels at the sides of the case to provide the necessary swing clearance. The need for the manufacturers to carry out this extra step would have added substantially to manufacturing costs. Even after this was done, the rod was limited to a very minimal lateral column thickness by diesel standards.

The fix was to use a skinny rod with very short bearings - likely a stamped item in the original design. So now we have an excessively skinny rod with too-short bearings that is constrained to run off-line! Worse and worse .......... Years ago, the late George Aldrich showed that the stiffer the rod, the better the performance. The AHC came nowhere near addressing this criterion. Moreover, even the skinny rod with its short bearings presented an assembly challenge. Maris Dislers has suggested a fix for this issue which involves the creation of a small radius on the rear underside edge of the crankpin, as shown in Maris's attached image. Of course, the enforced use of very short rod bearings in turn led to a further problem - the short bearings at both ends meant that only a very minimal amount of wear was required to free the rod to "wobble" out of its correct vertical alignment (viewed from the side). Hence the rod now had a tendency to wander off the vertical in a fore-and-aft direction, creating both excess friction and rapid uneven wear. The issues continued to mount.............

Finally, why they chose to employ an integrally-cast 0.125 in. (3.2 mm) I/D intake tube is quite beyond me - even the 0.140 in. bore (3.5 mm) adopted by Ron in his replicas is totally inadequate for an engine of this displacement. However, it's about all that the casting will accommodate given the fragility of this feature. Once again, there was an easy fix available - either use a larger O/D tube or (preferably) incorporate a cast boss on the rear of the crankcase into which a separate venturi could be threaded. Quite apart from the strength issue, the latter approach would have allowed the use of a venturi of adequate throat area which could easily be replaced in the event of a failure. It would also have had the great benefit of allowing the installation of the gudgeon pin to take place through the induction port after installation of the rod, thus dealing with the rod installation problem mentioned earlier. However, it seems that once again this only became apparent (if indeed it did become apparent!) after the investment in the castings had already been made. Overall, one gets the impression that Bernie Winston (or whoever designed this engine) didn't fully understand either the mechanical or functional principles that govern the operation of a model two-stroke engine. Consequently, the design incorporated a number of barriers to optimum performance and longevity as well as presenting some significant manufacturing challenges. Looked at from this perspective, the abandonment of the project becomes easily understandable. Regardless of the reason(s), the decision not to proceed to series production would normally have been the end of the matter, with no more being heard of the AHC diesel. However, in this instance the work completed up to the abandonment of the project was not lost. The cases were preserved together with a certain amount of design data. These materials passed through a number of hands during the ensuing years, including those of Motor Boy Tim Dannels, long-time editor of the “Engine Collector's Journal”.

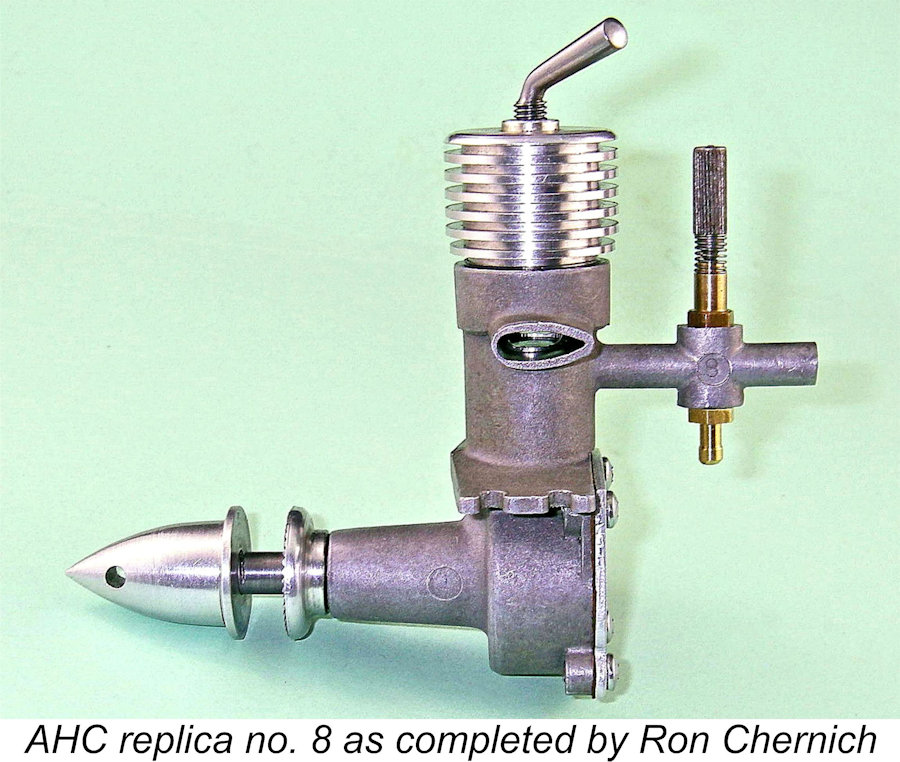

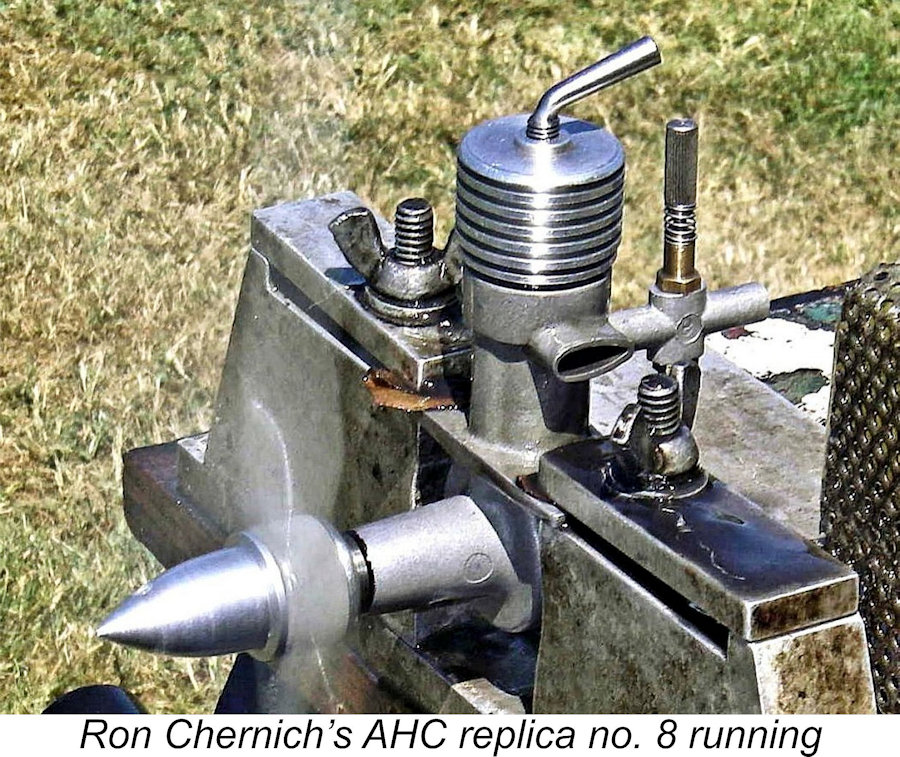

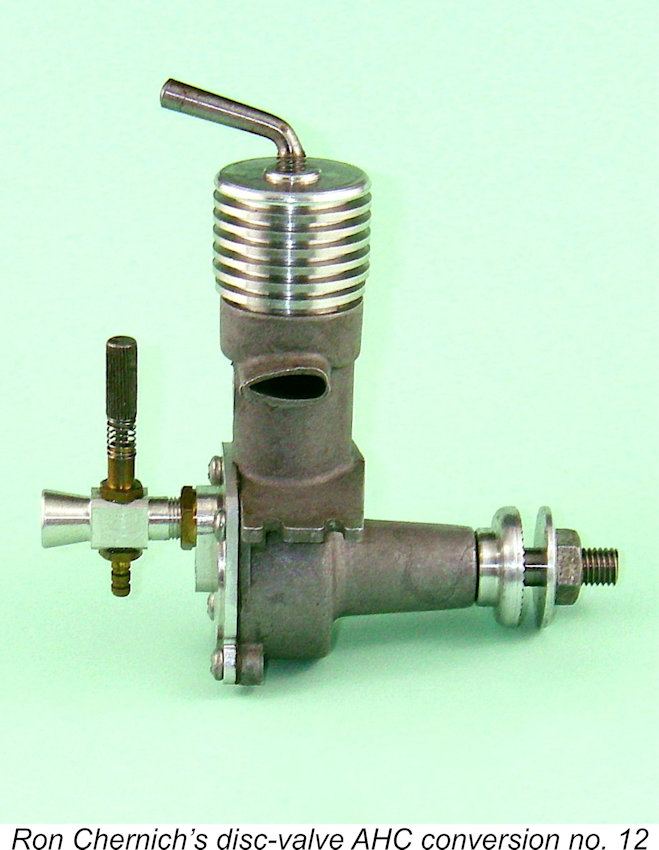

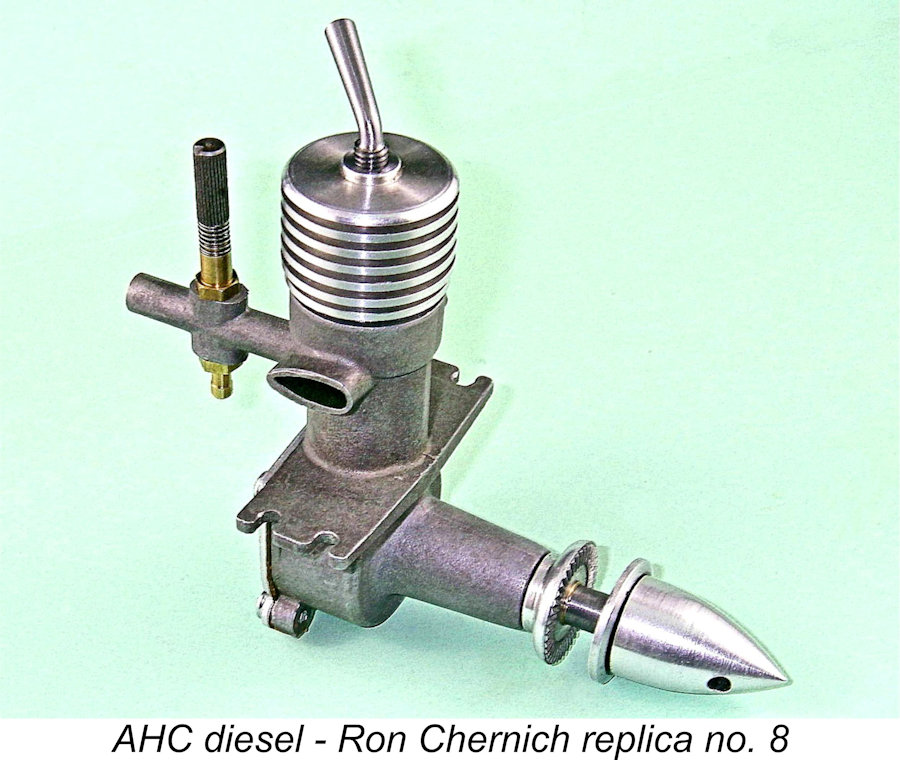

It is entirely thanks to the efforts of Ron and others like him that a fortunate few of us are able to enjoy the unusual experience of handling a classic model engine that never actually appeared on the market in its day! My own example of Ron's replica AHC is a lovely bit of work altogether, reflecting great credit upon Ron's skills. It bears the number 8, indicating its position in the very short series produced by Ron. It does however have one major flaw as a true replica - the record clearly demonstrates that AHC would never have allowed a model engine of this quality to bear their name! Ron described the production of these engines in detail in the AHC Project pages on MEN, as well as that of several experimental models using both RRV and FRV induction (see below). Accordingly, there is no need to repeat any of that material here. My acquisition of this fine replica on eBay placed me in the happy position of being able to test the engine to facilitate an assessment of how the AHC diesel might have fared in the model engine market of 1947 if it had actually made it into production. The AHC Diesel on Test I had no actual figure for the amount of running time which the AHC replica in my possession had received. Builder Ron Chernich advised that he ran all of them on the bench until they would hold a speed above 7,000 rpm on an APC 8x4 GF airscrew - typically around 20-30 minutes. I had no information regarding whether or not any subsequent owner had run the engine further. Regardless, the engine still felt a bit stiff to me, so to be on the safe side and to give the engine a fair chance I elected to give it a further 30 minutes prior to the commencement of the tests.

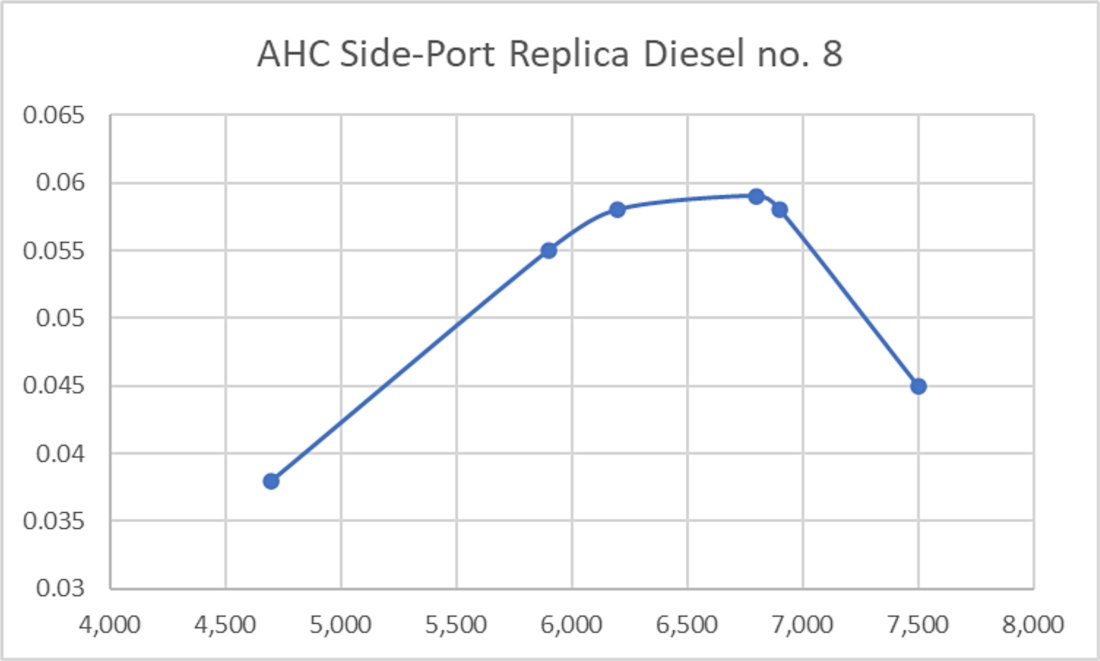

Close inspection of the unit revealed a possible cause for both of these issues. Ron used an original AHC case and Genie jet to make this engine, and it turned out that the jet was considerably too short for the socket into which it screwed. As a result, the jet orifice was set at the base of a "pocket" in the side of the venturi tube rather than being at the surface. This is very far from an ideal situation for a surface-jet needle valve assembly. It's an often-overlooked but absolutely critical fact that so-called air-cooled 2-stroke engines are actually fuel-cooled to a very significant extent. The incoming mixture makes a major contribution to cooling as it passes through the engine, so it's highly desirable that it be at the lowest possible temperature coming in. Carburetion plays an important role here since efficient atomization of the fuel draws the maximum evaporative latent heat out of the fuel, cooling the resultant mixture and thus maximizing the contribution to cooling made by the incoming fuel. It can also improve combustion quite significantly. Present-day team race exponents know all about this, hence their efforts to thermally isolate the spraybar from the rest of the engine. Indeed, Pete Buskell of tuned E.D. Racer fame was well aware of this factor way back in the 1950's - remember his spraybar modifications in “Model Aero Engine Encyclopaedia” aimed at improving fuel atomization? They work ............ Reasoning that improving the AHC replica's carburetion might help with the heating issue, I made a new jet having a longer thread which stopped right at the venturi wall. In place of the squared-off inner end of the standard AHC jet, the tip of the replacement jet took the form of a shallow cone which protruded slightly into the venturi throat. I have found such a design to give excellent carburetion with surface needle valves since it promotes high-speed airflow directly across the jet orifice. Believe it or not as you will, this greatly alleviated the problem - the engine would now needle far better and ran steadily at all speeds. Starting qualities remained outstanding. However, that was the end of the good news. The engine displayed an extremely modest level of performance for a 2 cc diesel, also vibrating to what I would consider to be an excessive degree, particularly at the higher speeds. The data collected were as follows:

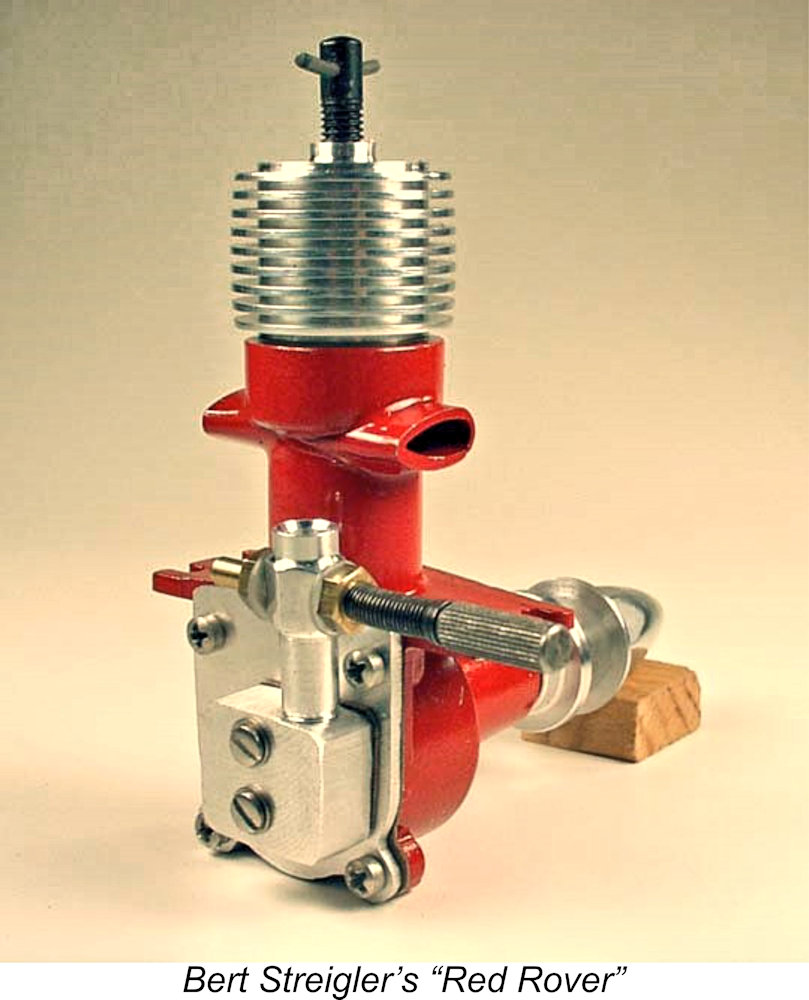

As can be seen, the AHC more or less lived down to my expectations - the engine was pretty much done by around 7,000 rpm. It seemed to peak in the vicinity of 6,500 rpm, at which speed it was making around 0.060 BHP. Most contemporary diesels of half the displacement would equal or exceed this figure, albeit at somewhat higher revs. As an example, a contemporary 1 cc "Bicycle-Spoke" Frog 100 Mk. II tested at the same session managed 7,000 RPM and 0.064 BHP on the same 9x4 APC airscrew which the 2 cc AHC spun at 6,800 RPM. It must also be recalled that the AHC as tested was not in strictly stock condition since, apart from my modified jet, it had the benefit of a substantially-reduced crankcase volume thanks to the fitting of my replacement backplate. Using the original backplate, I doubt that it would have even performed at the level that it did. My personal impression was that this engine is limited primarily by two factors. First, its induction system - it seems to have self-asphyxiation designed into it by virtue of that ultra-skinny venturi. And second, its seemingly chronic tendency towards excessive levels of vibration, about which nothing can really be done. Based on the above figures, it seems clear that the right props to use for flying would be the 10x4 or 9x6. These would allow the engine to reach its peak in the air while staying below the worst of the vibration. They would also shift a fair bit of air at a high level of working efficiency. Propped in this way, the engine would doubtless have been an adequate performer in a small free-flight sports model, although its low power and fragility would have greatly limited its usefulness in control line. The Motor Boys AHC “Fantasy” Engines The now-disbanded Motor Boys International group which evolved among the more dedicated and skilled worldwide associates of MEN Editor Ron Chernich were gifted model engineers possessing enquiring minds. They never confined themselves to simple acceptance of what they found but were always wide open to the “what if” factor. The late and greatly-missed Texan Motor Boy Bert Streigler brokered the original deal that led to the acquisition and distribution of the AHC project to members located in the USA, Australia, Canada and the UK. He also acted as “proof of concept” tester for the original AHC diesel plans upon which my engine no. 8 was based. Email discussion among the group led them to the shared conclusion that the AHC’s performance potential was severely restricted by the physical limitations placed on the engine by the induction arrangements. They began to wonder how the engine might have performed if it had been equipped with a rotary valve.

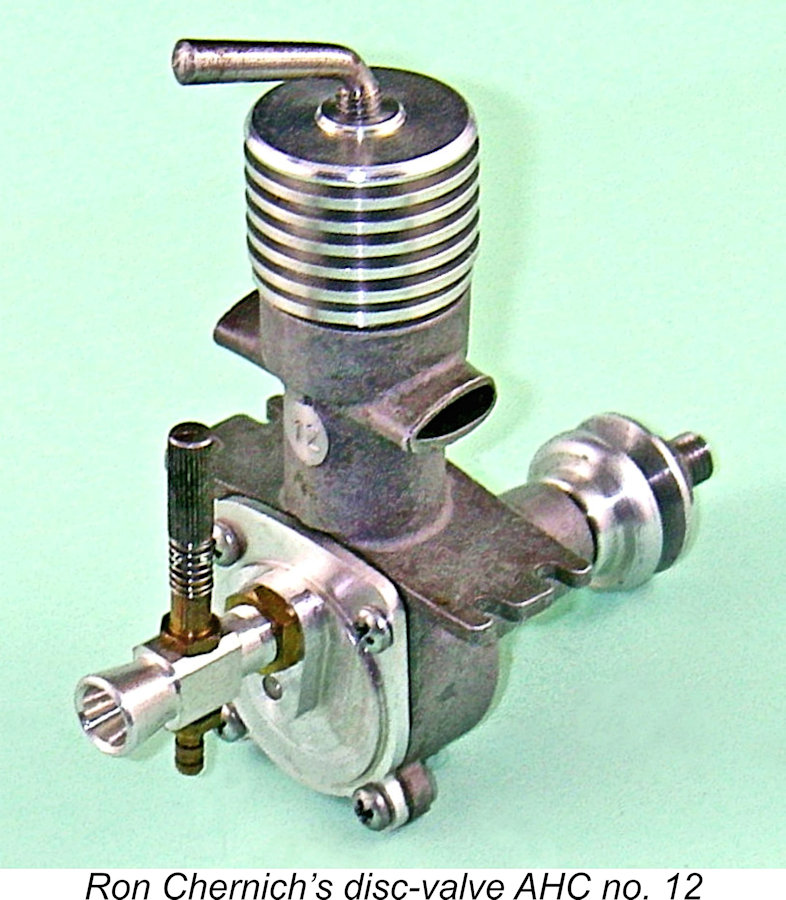

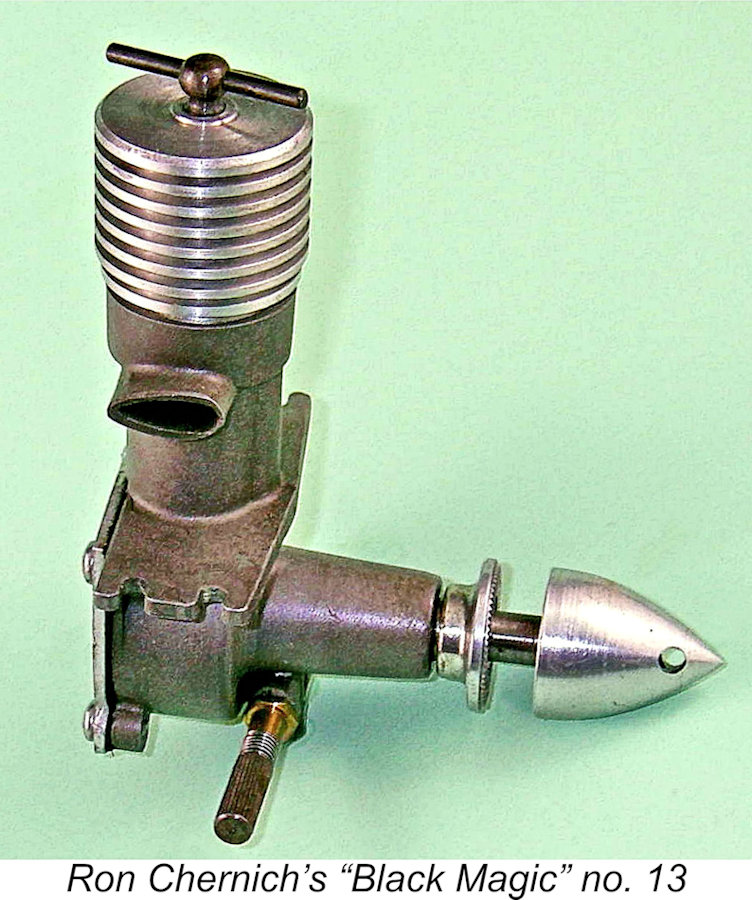

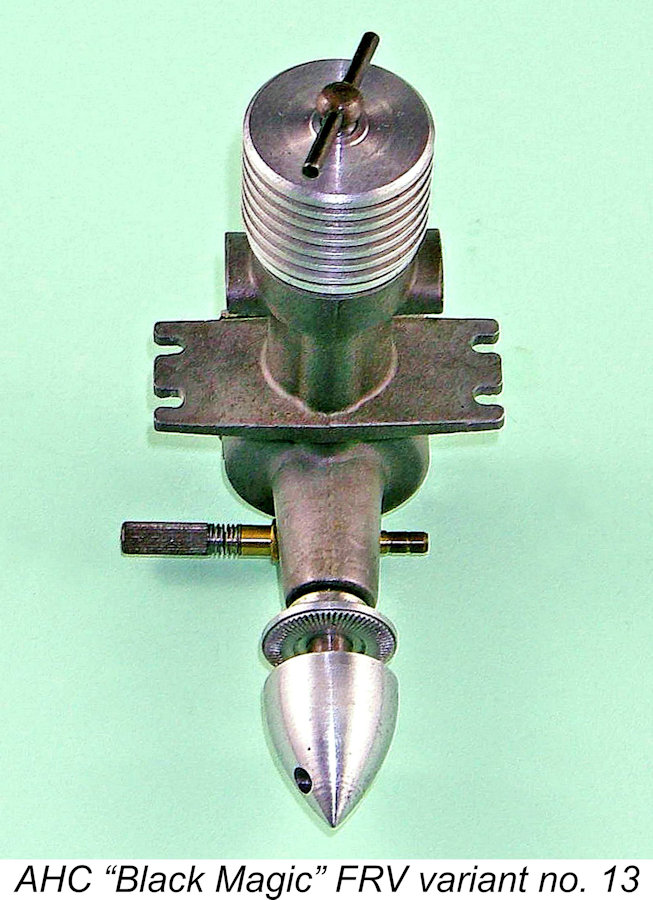

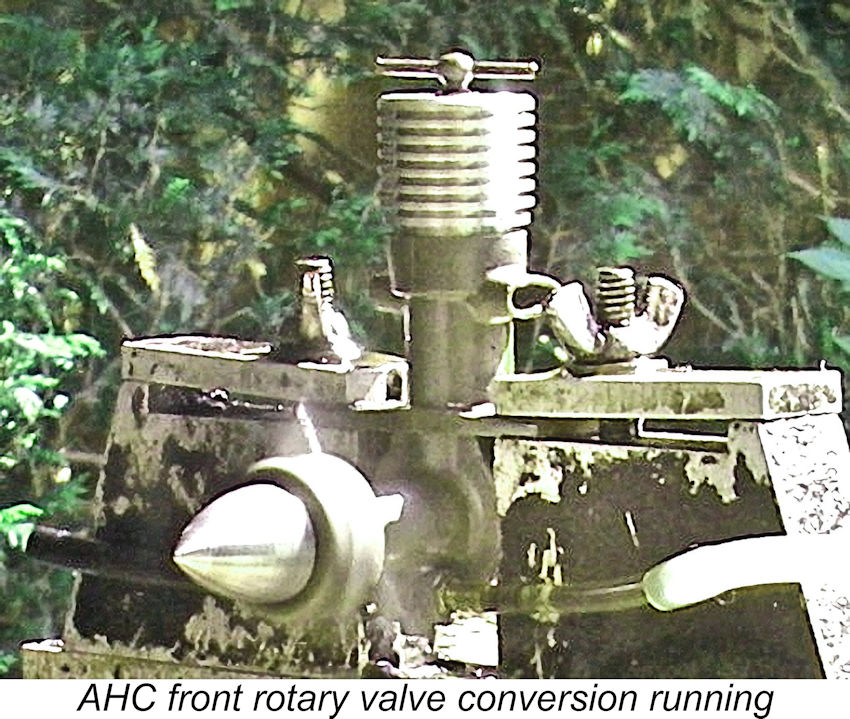

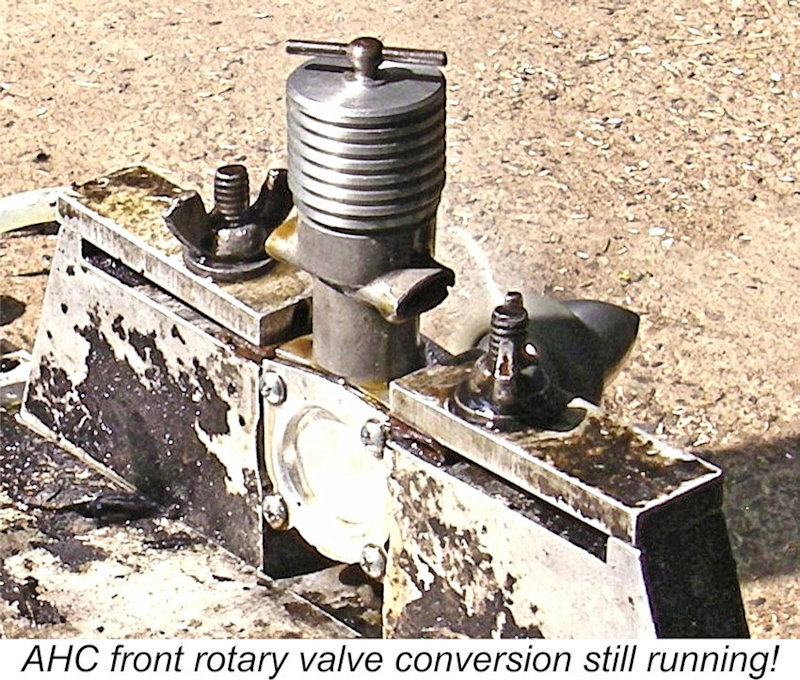

He began by cutting off the delicate venturi (before it fell off, some unkind souls might say) and creating a rear rotary disc valve driven by a small crankshaft extension timed to give 175 degrees of induction from 40 degrees ABDC to 35 degrees ATDC. A vertical downdraft intake was featured in order to minimize the engine's length. Bert applied some heat resistant red paint to the case, probably based on the well-known phenomenon that red cars always go faster (usually while being driven by attractive blond women!). The exhaust and transfer timing were unaltered. The black T-Bar compression screw added to the sporty look. Bert boldly named his creation the AHC “Red Rover” in honour of the classic car used in the original Motor Boys series of books. Bert ran in the engine for 30 minutes on a 9x4 Master prop, then opened it out on an 8x4. The modified engine turned that airscrew at 8,300 RPM, a considerable improvement on the figure obtained for the same prop on Bert’s side-port Ron also tried his own modification to the design, switching from a downdraft intake to a conventional “straight-in” alignment of the induction tube, providing a more direct path for the incoming mixture. This apparently performed just as well as Bert’s prototype had done. Ron was kind enough to pass engine no. 12 of this type along to me - see below. Ron then decided to pursue the concept of crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction applied to the basic AHC design. For reasons which are fully explained in his AHC project pages on MEN, he chose an updraft orientation for the intake. Continuing Bert Streigler’s colour-oriented nomenclature, he christened the FRV model the AHC “Black Magic” variant. Ron put a great deal of thought into the issue of the FRV’s version’s induction timing. Common (but not universal) practice for FRV model engines is to open the inlet about the time that the transfer closes. For the AHC, this occurs at about 57 degrees after bottom dead center (ABDC). Inertia of the gas flow in the inlet along with pressure lag in the crankcase allows induction to continue for some time after top dead center (ATDC). But the AHC is a relatively slow revving engine, meaning that the incoming flow velocity will not be high. Accordingly, to avoid the possibility of blow-back, it was decided to close at only 15 degrees after top dead center (ATDC). Allowing a degree or so between transfer closing and inlet opening gives a total inlet duration of 138 degrees; not all that much more than the 110 degrees provided by the side-port version. However, the end points are skewed to where they should provide far more efficient induction.

After a brief shake-down period on the 10x6 to settle the sliding bearings, the prop was changed to the standard 8x4 APC which Ron had used to test his previous AHC side-port diesels. The modified engine initially turned this prop at 8,800 RPM, although vibration was becoming a real issue. With a more rigid test mount to absorb the vibration, the speed on the 8x4 prop improved to a steady 9,200 RPM – a massive step upwards from the 7,300 RPM achieved by the standard side-port version and a considerable improvement over the 8,300 RPM achieved by the RRV “Red Rover” variant using the same prop. By now, there was absolutely no doubt that what looks like a rather constricted bypass passage is not the limiting factor constraining the potential performance of the basic AHC design – the primary suspect remains the constricted induction system. However, a further factor may be lurking in the weeds! Ron noted that the FRV “Black Magic” version turns considerably faster with significantly less inlet duration than the RRV “Red Rover” variant. This suggested to him that shaft lubrication was a factor which was considerably relieved by the use of FRV induction. These experiments by the Motor Boys demonstrated very clearly that the original side-port AHC is a deeply flawed design. Of course, all single cylinder two-strokes are an assemblage of compromises. As soon as one performance impediment is neutralized, another takes over center court. In the case of the AHC, the Boys proved that the primary limitation is the inability of the side-port induction system to supply sufficient fuel mixture. Both the RRV and FRV versions easily passed the 7,300 RPM offered by the best of the side-ports tested by Bert and Ron on the same 8x4 prop. My example tested in 2011 only managed 7,500 RPM on the same airscrew, as reported above, and that was with the help of my efforts to reduce crankcase volume.

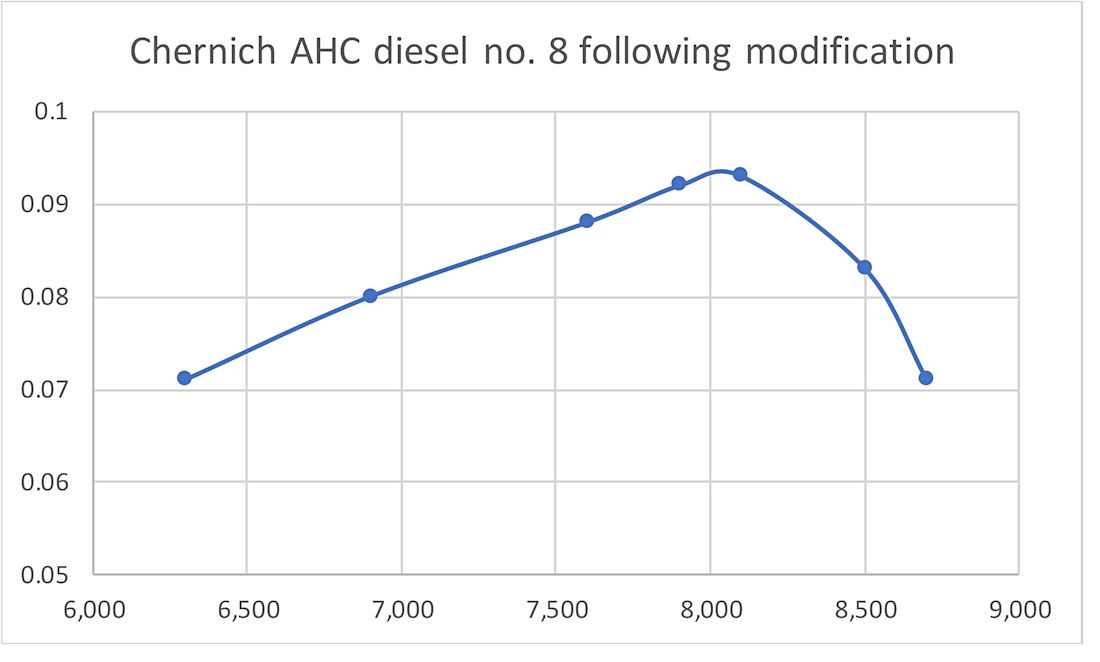

Ron assessed the balance factor as being rather difficult to address. The crankweb is only 1/8 in. thick and already cut away to the max in order to provide some illusion of counterbalance. Thickening it is not really practical due to the geometry involved. Looks as if the AHC is stuck with a poor balance factor ………….. On the basis of these experiments, it appeared that the FRV “Black Magic” version represents the peak of performance for any AHC derivative. Careful attention to propeller balance might reduce the vibration and add a few RPM, but over 9,000 rpm on an 8x4 prop from such a long-stroke engine is nothing to sneeze at in any case. Ron considered the FRV “Black Magic” to be a success despite the vibration issue. He intended to make a few more of them, but I don’t know if he ever did so or how many he did make. It's quite clear from the above litany that the original side-port AHC diesel was a non-starter as a commercial offering. The Winstons must have realized immediately upon testing the prototype that they had an under-performing bone-shaker on their hands which also presented some production challenges. Small wonder that they abandoned the project rather than throwing good money after bad. A Latter-Day Comparative Test Preparing the revised text of this article reminded me of some unfinished business which I had set aside for far too long. Shortly before his untimely death in early 2014 (which he saw coming), Ron had sent me examples of both his “straight-in” RRV “Red Rover” variant and the FRV “Black Magic” version of the AHC which he had made himself. These previously-illustrated engines bore the numbers 12 and 13 respectively. It was Ron's wish that I would put these units through their paces in direct comparison with the side-port example no. 8 already in my possession. The considerable effort involved in setting up my own website following Ron’s demise distracted me, and I’m ashamed to admit that it took me until 2023 to finally get around to fulfilling Ron’s desire. The reawakened ambition to get this done prompted me to get the three engines on to the work bench for a full examination. The RRV and FRV examples seemed to be in fine fettle, all ready to go. However, my side-port example seemed to have slightly “soft” compression Accordingly, in early 2023, prior to undertaking the transfer of this article from MEN to my own website, I sent my example of the side-port AHC over to my good mate Peter Valicek of the Netherlands. Apart from the apparent need to address the somewhat leaky piston/cylinder fit, I asked Peter to check the engine out very thoroughly. I had the results of my earlier testing already in hand. Accordingly, in making this request I authorized Peter to make any improvements that he deemed necessary in order to optimize its performance. If the engine had been further developed back in the day, efforts would certainly have been made to improve it. I was looking for the engine's potential if development had proceeded. Going over the engine with a critical eye, Peter found a number of matters warranting attention.

The crankshaft was found to be a slightly loose fit in its bearing. Obviously, Peter could do nothing about this. It would almost certainly have an impact upon the working life of the conrod bearings, but it shouldn’t affect running in the short term. Peter found that the unhardened shaft ran in a cast iron bushing. An unhardened shaft in a cast iron bushing is not considered to be an ideal combination, but there it is!

The idea of a hole in the centre of the shaft with exit holes is a good one in theory, but it has its limitations. The trouble is that when the engine runs, the oil is flung outwards away from the central hole by centrifugal force, so very little oil gets into the hole and along to the bearing. It’s still a good idea to have a small groove at the top of the thrust bearing in the case to allow oil to flow down by gravity to the rear of the bearing where the load is highest. Upon its return from Peter’s extremely capable care, I lost no time in setting up the rebuilt engine in the test stand to run it in. The loose main bearing and consequent projected accelerated wear on The rebuilt AHC proved to be just as easy a starter as it had been prior to Peter's rebuild. It liked a small prime when cold, but started when hot with just a couple of choked flicks. Response to the controls was excellent, although the Genie needle valve was rather a "wobbly" fit. That said, it held its settings just fine once these were established. The engine ran the tank out cleanly every time. During the break-in, I kept the needle a little rich with reduced compression, although I leaned the engine out all the way for the final few seconds, after which I allowed complete cooling before going for a restart. This put the engine through a series of full-range heat cycles - probably the most important element of a good iron-and-steel break-in. After the break-in was done, I got into the main testing sequence, beginning this process with an APC 10x4. Starting remained excellent at all times, with very smooth running on all props. The one fly in the ointment was the vibration issue - although Peter had made the replacement piston as light as possible, the engine still generated increasingly-detectable levels of vibration as speeds climbed. By the time that 7,600 RPM was reached using the APC 9x5, vibration levels had become unacceptable in my personal view, at least when envisioning the engine mounted in a model as opposed to a very heavy and rigid test stand. Despite this handicap, the engine turned in a really excellent performance, as demonstrated by the following data:

As can be seen, the modified AHC performed at a level which far outstripped the figures achieved for the same engine in unmodified form. It appeared to develop a peak output of around 0.093 BHP @ 8,100 RPM as opposed to the 0.060 BHP @ 6,500 RPM implied by the data for the unmodified engine. The Now before we get too carried away, we have to remember that everything is relative! This is still a pretty lacklustre performance for a 2 cc side-port diesel of the era. While it more or less matches the performance of, say, an E.D. Mk. II "Pennyslot" or a Majesco "22", it lags well behind the E.D. Comp Special which appeared in late 1947. In standard unmodified form, it was no contest - all of the contemporary 2 cc designs handily outperformed the stock AHC. Even in modified form, the AHC was well short of being a star performer!

Still, Peter's modifications to the "stock" AHC diesel have demonstrated very clearly that the engine had potential. Further development to deal with a few residual issues which even Peter couldn't fix, including a more appropriately-proportioned main casting to allow for improvement of the balance factor and conrod alignment as well as a more appropriately-dimensioned intake, might have resulted in a very useful side-port diesel for sport-flying applications.

This example had been set up a little on the tight side as built. I had given it some running time upon receiving it from Ron, but it still felt a little "sticky" to me. For this reason, I felt that it required a bit of a break-in prior to the test. I decided to follow the same procedure that I had applied to the modified side-port variant by giving the RRV model a further 30-minute break-in prior to testing.

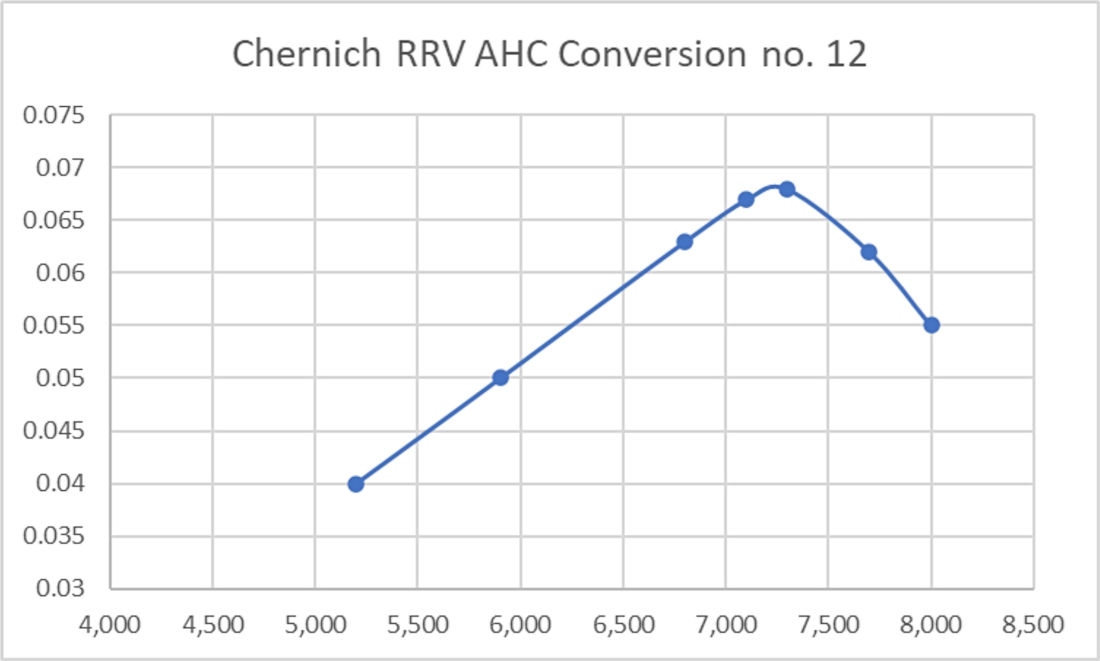

Once the break-in was complete, I ran the same set of test props that I had used for the side-port test, also using the same fuel. The engine continued to start and run very well, with no mechanical problems being encountered. The following data were recorded:

Somewhat surprisingly, this variant performed at a level which represented only a very modest improvement over the stock unmodified side-port version. It lagged far behind the modified side-port example created by Peter Valicek. It appeared to develop some 0.068 BHP @ 7,300 RPM - a little better than the stock side-porter's 0.060 BHP @ 6,500 RPM, but not greatly so. The vibration issue was still very much in evidence - when mounted in a model, it's unlikely that the engine's full potential could be utilized in any case. I can't see it being useable in a model above 6,500 RPM or thereabouts. To me, this result says that the constricted entry into the bypass passage must do much to limit the engine's ability to actually use the extra fuel mixture which the RRV induction system should theoretically provide. Peter Valicek's modification to the bypass entry of the side-port version would doubtless be equally effective here. A larger intake venturi bore would also improve matters to a significant extent. But in view of the vibration problem, it's likely that any further performance enhancement would be wasted - the vibration issue would prevent it from being fully utilized. Admittedly, the RRV engine was still detectably tighter than its side-port compatriot, even despite the break-in to which it had been subjected. If freed up to a comparable extent, it would doubtless do a little better than this. Even so, on this showing the modified side-porter remained the one to beat!

A problem with the updraft intake on this example is that fact that when set up in a conventional test stand the needle valve is completely inaccessible. I got around this by slipping the end of a length of plastic tubing over the control knob to serve as a flexible extension. This would not be a problem in a model installation, since design measures could easily be incorported to allow full access. Once again, I began with a 9x4 APC airscrew fitted. Apart from the need to provide a needle valve control extension (which can be seen in the image below at the right), it was also necessary to ensure that the fuel level in the tank stayed below the needle valve to prevent loss of Provided this was done, the engine proved to be just as easy to start as its prececessors, also showing a healthy willingness to spin the test prop at a most encouraging rate. For the first couple of runs I kept it a little rich and under-compressed, just to be on the safe side. However, during the brief leaned-out periods with which I concluded each run, the prop was spinning at upwards of 8,000 RPM, beating anything achieved by the other tested units on that prop, including the modified sideporter. Since the engine seemed to be completely freed-up, hence not requiring any further running-in, I proceeded to test it on the same set of airscrews used for the other engines. The results were quite impressive, as follows:

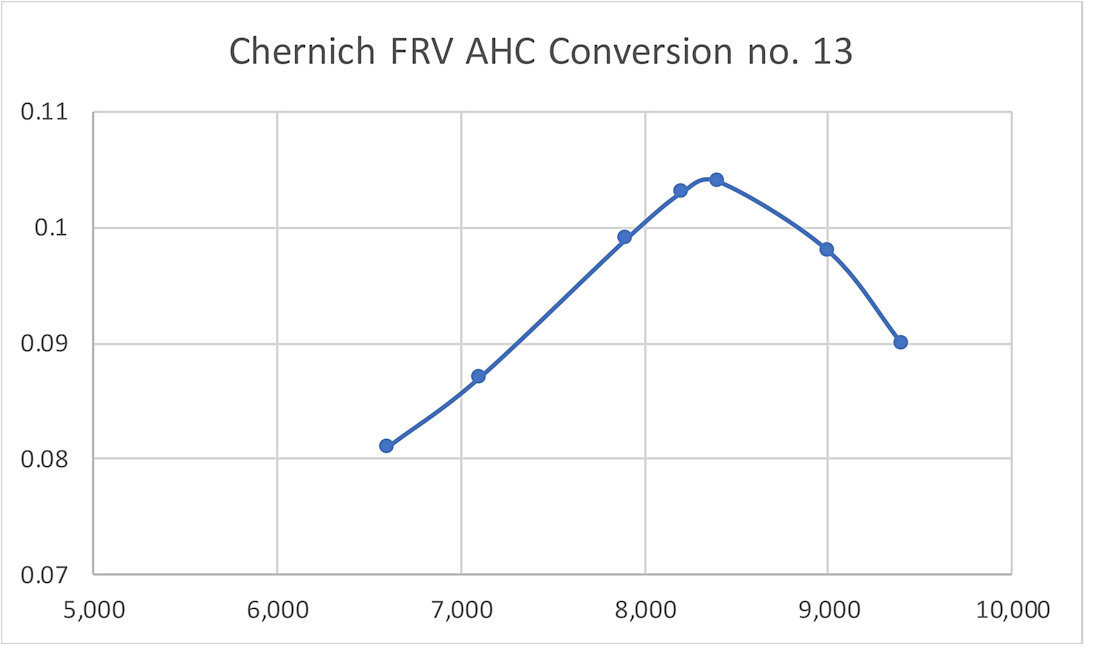

The FRV "Black Magic" version of the AHC diesel fully justified creator Ron Chernich's claim that it was the best of the various AHC variants tried by the Motor Boys. Its performance put even that of Peter Valicek's modified AHC side-port unit in the shade! It developed around 0.104 BHP @ 8,400 RPM, making it the undisputed champion of this series of tests.

Even at what appeared to be its peaking speed of 8,400 RPM, the level of vibration was basically unmanageable. My impression was that the vibration issue would prevent the engine from being used effectively in a model at any speed over 6,500 RPM, even with a very firm mounting. This would accommodate the original unmodified side-port version, which peaked at around 6,500 RPM and could be propped for a ground speed of around 5,500 RPM. However, it effectively negated the benefits resulting from the various modifications described earlier, since those modifications pushed the engine's peak into a speed range in which it was not really useable in practical terms. Frustrating!! The AHC Replicas

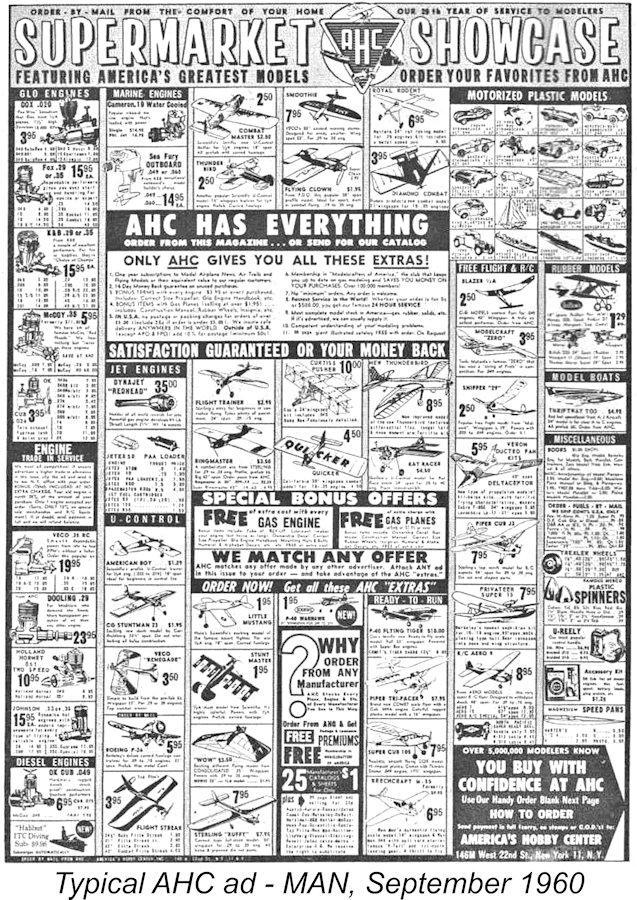

A number of individual examples of this engine have been completed in various parts of the world by home constructors who were granted access to cases and drawings. Both the late Bert Streigler (USA) and the late Russell Watson-Will (Australia) produced outstanding examples. There may well have been others in addition. At the time of writing in 2023, my good mate Peter Valicek was planning to make a couple more examples using original cases which he had acquired. There are still unused cases floating around ……………. The closest thing to date to a series production effort in connection with the AHC was the short run of replicas produced by MEN’s talented Editor, the late Ron Chernich. As described earlier, Ron's side-port variants are as faithful a series of replicas of the AHC original as anyone could produce today given the absence of any original prototypes. We are fortunate that Ron documented this project very thoroughly in a separate series of articles on MEN. As far as I'm aware, there have been no subsequent attempts to produce a series of AHC replicas. The Aftermath The fact that the AHC diesel never made it into production had absolutely no observable effect upon the fortunes of AHC. The business continued to be spearheaded by Bernie Winston and his brother, with control later passing to Bernie's son Marshall in the early 1970's. According to a number of postings on various modelling forums, Marshall lacked his dad's affability and approachability, which seems to have put off quite a few in-store customers. Regardless, the company carried on right through the Golden Era of aeromodelling and beyond, offering their world-wide mail order service as well as maintaining a storefront retail operation at their original address in New York City. At their peak, they added a second storefront location in New York as well as establishing branch offices in Chicago and Los Angeles. They offered all types of models and related equipment at discount prices, running detailed multi-page adds in all the major American model magazines. I was an avid reader of those ads myself, placing orders fairly regularly. They offered many items which I couldn't get locally.

Some native New Yorkers have defended the business, claiming that impressions of the above kind were mainly due to out-of-town visitors being unfamiliar with the legendary New York "attitude" towards customers and out-of-towners. However, most of AHC's business was conducted by mail order, with modellers all over the world being supplied in this way. I myself was a regular customer in the 1960's and 1970's, placing my orders from the Canadian West Coast. I must say that I never had any reason to complain - the prices were indeed very competitive and delivery was generally quite prompt within the limits of then-available mail services. I suspect that for every face-to-face customer who felt himself to have been poorly treated there were hundreds of satisfied mail order customers like myself. In fact, it was probably the changing face of the modelling hobby that determined the eventual fate of AHC. As time went by, fewer and fewer people remained willing or able to build their own models, preferring to have their fun delivered in a box with only minimal assembly required. In addition, R/C became by far the dominant form of model aircraft operation. Both of these factors naturally raised the cost of participation in the hobby, which thus became an activity open only to those with means as opposed to those with interest and ability. Generally, this meant individuals who had finished their education and were out in the workforce with spare cash to spend - the impecunious but very numerous youngsters (like myself in the late ‘50's and early ‘60's) who formerly made up a sizeable proportion of aeromodelling participants and who maintained their interest into adulthood more or less disappeared, taking the future expansion prospects of the hobby along with them. Basically, there were no more aeromodellers - there were merely model fliers who were willing and able to pay for the privilege. Aeromodelling had degenerated from a hobby to an activity ............ As a result of all this, the market for the broad range of modelling goods which had propelled AHC to the heights progressively dried up. The company kept going through the 1970's and 1980's – the late MEN Editor Ron Chernich actually visited their 22nd Street location in 1970 and lived to tell the tale (it was daytime!). In addition, the mail order business was maintained. However, an ever-shrinking customer base coupled with a decrease in the range of modelling goods for which demand existed created a continuing erosion of business conditions. Much of AHC's accumulated unsold stock was apparently purchased during the 1990's by a chap named Curtis Mattikow, who also acquired the residual warehouse inventory of the legendary hobby dealer and wholesaler Elmer Roth (d. 1981) of Salem, Oregon at around the same time. This disposal of assets was insufficient to save the AHC company, which filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in September 2000. This was not the end of the road, however. Under the bankruptcy laws of the United States, filing for Chapter 11 protection allows reorganization of the protected company. This appears to have been the route taken by AHC. The company (or perhaps a successor) carried on for a time at the 22nd Street location before relocating to a new address at 8300 Tonnelle Avenue, North Bergen, New Jersey. According to its website, the company was still in business at that location in 2011 under the ownership of a New Jersey company called Jaryl International Inc. The precise relationship of this operation to the original company was unclear, but there was no doubt that it still used the original AHC "shield" emblem and claimed to be a direct descendant of the original company. It appears to have subsequently ceased operations - I could no longer find it as of 2023. Conclusion

We'll never know what an original AHC diesel might have been like because the engine never reached the production stage. We thus have no way of assessing the standards which would have been applied to its manufacture. We can only hope that they would have been somewhat higher than those applied to the rival Deezil, although the contemporary AHC slag engine series gives us reason to doubt that it would have been so! Regardless, the efforts of Ron Chernich, Bert Streigler and the other Motor Boys have demonstrated quite conclusively that while the engine was certainly no barn-burner, a well-made example would have been a very useable engine indeed for sport flying, with plenty of development potential. The AHC undoubtedly had what it took to provide its owners with a relatively painless introduction to diesel operation and could have performed quite adequately in a sport flying context. This being the case, it might have done much to advance the cause of the model diesel in the USA if it had been developed and manufactured to appropriate standards. We’ll never know …………… ___________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published September 2023

|

||

| |

In an

In an  The development of the AHC diesel was instigated by America’s Hobby Center (AHC) of New York City. This business was founded in 1931, being established as a distribution and retail outlet for model goods of all kinds. It traded from premises located at 146 West 22

The development of the AHC diesel was instigated by America’s Hobby Center (AHC) of New York City. This business was founded in 1931, being established as a distribution and retail outlet for model goods of all kinds. It traded from premises located at 146 West 22

AHC began its direct involvement with the model engine market in 1936, when the company took control of the development and marketing of the competently-executed pioneering

AHC began its direct involvement with the model engine market in 1936, when the company took control of the development and marketing of the competently-executed pioneering  The machining work involved in the manufacture of the G.H.Q. was reportedly carried out at a machine shop run by Harry Winston. Several posters on the various modelling forums have claimed (rightly or wrongly) that Harry Winston's machine shop was one of the few in the USA that didn't get a Government production contract following America's entry into WW2 in December 1941! Some unkind souls have speculated that the Government inspectors took one look at the G.H.Q. and figured that America's war machine deserved something a little better! This may possibly explain at least in part why the G.H.Q. remained available throughout WW2 and beyond.

The machining work involved in the manufacture of the G.H.Q. was reportedly carried out at a machine shop run by Harry Winston. Several posters on the various modelling forums have claimed (rightly or wrongly) that Harry Winston's machine shop was one of the few in the USA that didn't get a Government production contract following America's entry into WW2 in December 1941! Some unkind souls have speculated that the Government inspectors took one look at the G.H.Q. and figured that America's war machine deserved something a little better! This may possibly explain at least in part why the G.H.Q. remained available throughout WW2 and beyond.

By late 1946 several American manufacturers had begun to market diesel models, with more soon to follow. A number of these early American designs possessed considerable merit by any standard - the

By late 1946 several American manufacturers had begun to market diesel models, with more soon to follow. A number of these early American designs possessed considerable merit by any standard - the  seems that the project actually reached the early stage of production with the creation of the required die and the manufacture of almost 1000 crankcase castings. Moreover, AHC appear to have completed several engines, presumably to serve as prototypes for testing purposes.

seems that the project actually reached the early stage of production with the creation of the required die and the manufacture of almost 1000 crankcase castings. Moreover, AHC appear to have completed several engines, presumably to serve as prototypes for testing purposes. difficult to machine and thread properly. It's not unlikely that machining difficulties presented themselves during the prototype production phase, quite possibly resulting in the spoiling of an unacceptable proportion of castings.

difficult to machine and thread properly. It's not unlikely that machining difficulties presented themselves during the prototype production phase, quite possibly resulting in the spoiling of an unacceptable proportion of castings. Assembly was another matter that was not accommodated by the design. The arrangement of the upper crankcase casting is such that the piston and rod have to be installed as an assembly - you can't fit the piston following rod installation. However, the available space severely limits the rearward movement of the assembly for installation, so you have to tilt the rod to slip the big end over the crankpin. This makes installation with a closely-fitted big end bearing of adequate length impossible.

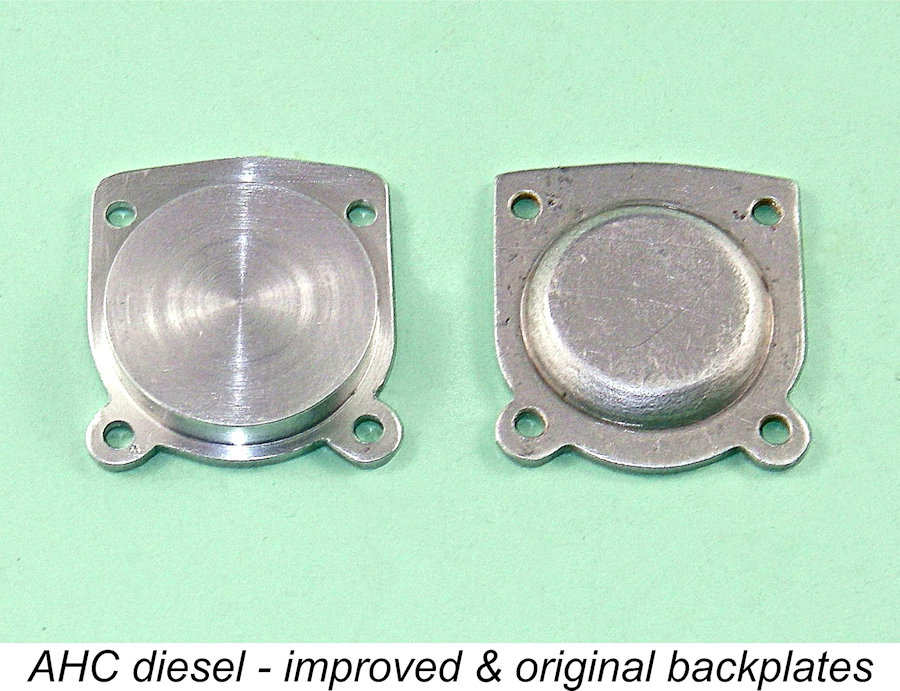

Assembly was another matter that was not accommodated by the design. The arrangement of the upper crankcase casting is such that the piston and rod have to be installed as an assembly - you can't fit the piston following rod installation. However, the available space severely limits the rearward movement of the assembly for installation, so you have to tilt the rod to slip the big end over the crankpin. This makes installation with a closely-fitted big end bearing of adequate length impossible.  The use of a thin stamped aluminium backplate was also a poor design decision since it left a very sizeable gap between the inner front face of the backplate and the rear of the crankpin as well as creating a substantial annular space around the inwardly-protruding boss of the stamped backplate. This in turn created a lot of unnecessary dead space in the crankcase, thus impairing the engine's pumping efficiency by reducing its base compression ratio. It also left the con-rod big end free to work its way off the crankpin if it felt like doing so. I made a replacement backplate for my example which significantly decreased the crankcase volume.

The use of a thin stamped aluminium backplate was also a poor design decision since it left a very sizeable gap between the inner front face of the backplate and the rear of the crankpin as well as creating a substantial annular space around the inwardly-protruding boss of the stamped backplate. This in turn created a lot of unnecessary dead space in the crankcase, thus impairing the engine's pumping efficiency by reducing its base compression ratio. It also left the con-rod big end free to work its way off the crankpin if it felt like doing so. I made a replacement backplate for my example which significantly decreased the crankcase volume.  The late MEN Editor Ron Chernich was among those fortunate enough to acquire a stash of cases from Tim along with what remained of the design details. This was a happy occurrence since Ron was sufficiently skilled and dedicated to generate a set of CAD drawings and complete a short production run of this mega-rare engine using original AHC cases and needle valve components. The bore and stroke of Ron's replicas are 0.468 in. (11.89 mm) and 0.680 in. (17.27 mm) respectively for a displacement of 1.92 cc (0.117 cuin). The replica engine weighs 129 gm (4.55 ounces) without tank.

The late MEN Editor Ron Chernich was among those fortunate enough to acquire a stash of cases from Tim along with what remained of the design details. This was a happy occurrence since Ron was sufficiently skilled and dedicated to generate a set of CAD drawings and complete a short production run of this mega-rare engine using original AHC cases and needle valve components. The bore and stroke of Ron's replicas are 0.468 in. (11.89 mm) and 0.680 in. (17.27 mm) respectively for a displacement of 1.92 cc (0.117 cuin). The replica engine weighs 129 gm (4.55 ounces) without tank. Ron had warned me that his AHC replicas had a tendency to run hot. I thought this a little surprising given the low-tech design of the engine, but initial tests confirmed Ron's advice completely. Although the engine was very easy to start, never needing a prime at any time, it proved difficult to establish an optimum needle setting and the engine sagged quite markedly when warmed up. After stopping, it felt quite a bit hotter than I'd generally expect an engine of this specification to feel. This may have been partially due to residual stiffness, although this was insufficient in my view to be a major cause for the overheating.

Ron had warned me that his AHC replicas had a tendency to run hot. I thought this a little surprising given the low-tech design of the engine, but initial tests confirmed Ron's advice completely. Although the engine was very easy to start, never needing a prime at any time, it proved difficult to establish an optimum needle setting and the engine sagged quite markedly when warmed up. After stopping, it felt quite a bit hotter than I'd generally expect an engine of this specification to feel. This may have been partially due to residual stiffness, although this was insufficient in my view to be a major cause for the overheating.

Never averse to trying something “different”, Bert Streigler set about seeing how the AHC case could be adapted to a different induction scheme. Two basic possibilities presented themselves; front crankshaft rotary and rear induction. From the rear, several variations were possible: rotary valve (disk or drum), reed valve and "clack" valve. Bert chose to give the rear rotary disc valve a try.

Never averse to trying something “different”, Bert Streigler set about seeing how the AHC case could be adapted to a different induction scheme. Two basic possibilities presented themselves; front crankshaft rotary and rear induction. From the rear, several variations were possible: rotary valve (disk or drum), reed valve and "clack" valve. Bert chose to give the rear rotary disc valve a try. model. It’s clear that the “Red Rover” configuration provided the basic engine with the fuel/air mix it needed to realize the capability of the rest of the engine. Ron Chernich subsequently built several examples of the “Red Rover” (including a few missing the red paint!).

model. It’s clear that the “Red Rover” configuration provided the basic engine with the fuel/air mix it needed to realize the capability of the rest of the engine. Ron Chernich subsequently built several examples of the “Red Rover” (including a few missing the red paint!). On test, Ron’s FRV “Black Magic” version of the AHC started second flick! It was fitted a little on the loose side, appearing very willing to rev out right away - even with the 10x6 APC break-in prop, it was turning over 7,000 RPM set rich with the compression backed off. There was no trouble choking the updraft venturi and no problem with "siphoning" while stopped.

On test, Ron’s FRV “Black Magic” version of the AHC started second flick! It was fitted a little on the loose side, appearing very willing to rev out right away - even with the 10x6 APC break-in prop, it was turning over 7,000 RPM set rich with the compression backed off. There was no trouble choking the updraft venturi and no problem with "siphoning" while stopped. The next limitation in line seemed to be shaft lubrication. The RRV variant was timed for 175° of inlet duration, yet the FRV version easily topped it by at least 900 RPM with an inlet duration of only 138°. All versions of the AHC were found to run hot. Using instrumentation of dubious accuracy, namely carefully calibrated burnt pinkies, Ron found that the journal of the side-port and RRV variants seemed to get as hot as the head. The FRV induction system resolves this issue, supplying ample oil and cooling to the bearing and passing the limiting factor on to the next problem area – the AHC is very badly balanced internally.

The next limitation in line seemed to be shaft lubrication. The RRV variant was timed for 175° of inlet duration, yet the FRV version easily topped it by at least 900 RPM with an inlet duration of only 138°. All versions of the AHC were found to run hot. Using instrumentation of dubious accuracy, namely carefully calibrated burnt pinkies, Ron found that the journal of the side-port and RRV variants seemed to get as hot as the head. The FRV induction system resolves this issue, supplying ample oil and cooling to the bearing and passing the limiting factor on to the next problem area – the AHC is very badly balanced internally. following its earlier running in my hands. I was very keen to ensure that since the RRV and FRV versions of the engine had been optimized by their constructor, the same should apply to the side-port model.

following its earlier running in my hands. I was very keen to ensure that since the RRV and FRV versions of the engine had been optimized by their constructor, the same should apply to the side-port model. One point that was clarified by Peter’s inspection was the approach taken by Ron to the supply of lubricant to the main bearing. The shaft had a small hole drilled centrally part-way through it from the rear. On the journal surface at the point of termination, a small groove was formed. This communicated with the central drilling through two opposing small holes. These were clearly intended to supply oil to the journal at that location, with the groove providing a measure of local storage for the oil.

One point that was clarified by Peter’s inspection was the approach taken by Ron to the supply of lubricant to the main bearing. The shaft had a small hole drilled centrally part-way through it from the rear. On the journal surface at the point of termination, a small groove was formed. This communicated with the central drilling through two opposing small holes. These were clearly intended to supply oil to the journal at that location, with the groove providing a measure of local storage for the oil.

Even the

Even the  Turning now from what may be considered as the "fantasy" side-port AHC diesel model, we have to examine the other two "fantasy" engines which were available for test. First up in this category was Ron Chernich's RRV version of the AHC, engine no. 12.

Turning now from what may be considered as the "fantasy" side-port AHC diesel model, we have to examine the other two "fantasy" engines which were available for test. First up in this category was Ron Chernich's RRV version of the AHC, engine no. 12.  No sooner decided than done! The engine went into the stand with an APC 9x4 prop fitted and embarked upon its break-in, being kept a little rich and under-compressed apart from a final leaned-out burst to complete the full-range heat cycles which are so essential to the

No sooner decided than done! The engine went into the stand with an APC 9x4 prop fitted and embarked upon its break-in, being kept a little rich and under-compressed apart from a final leaned-out burst to complete the full-range heat cycles which are so essential to the

Finally it was the turn of FRV "Black Magic" engine no. 13. I had run this one too when I first received it from Ron. It had clearly been assembled far less tight than its RRV companion - it felt all ready to go right away. I decided to give it a couple of shake-down runs and then get straight into the testing.

Finally it was the turn of FRV "Black Magic" engine no. 13. I had run this one too when I first received it from Ron. It had clearly been assembled far less tight than its RRV companion - it felt all ready to go right away. I decided to give it a couple of shake-down runs and then get straight into the testing.  fuel by gravity while preparing for a start. As usual with updraft-intake engines, finger-choking had little effect - any fuel drawn in simply dripped out of the intake. A small port prime was required to elicit a response from the engine.

fuel by gravity while preparing for a start. As usual with updraft-intake engines, finger-choking had little effect - any fuel drawn in simply dripped out of the intake. A small port prime was required to elicit a response from the engine.

Mind you, all was far from perfect. Even though the engine was very firmly secured in a heavy and solidly-mounted test stand, it was apparent that vibration was a definite issue. In

Mind you, all was far from perfect. Even though the engine was very firmly secured in a heavy and solidly-mounted test stand, it was apparent that vibration was a definite issue. In  Returning now to historical reality, we've already seen that the original side-port AHC diesel never reached the series production stage - only a few prototypes appear to have been produced by AHC, and none of these are known to have survived. As a result, any AHC diesel which may be encountered today will be a replica. Do not allow yourself to be bamboozled by an unscrupulous seller!

Returning now to historical reality, we've already seen that the original side-port AHC diesel never reached the series production stage - only a few prototypes appear to have been produced by AHC, and none of these are known to have survived. As a result, any AHC diesel which may be encountered today will be a replica. Do not allow yourself to be bamboozled by an unscrupulous seller!  Customer impressions of the AHC operation seem to vary widely. There are many stories about their seeming lack of business ethics as epitomized by the G.H.Q. and slag engine eras. A commonly-expressed view among those who actually visited their store is that while their prices were good, in-store customer service was non-existent. Staff were allegedly known to pressure customers into buying the items on which the store had the highest profit margin, whether or not they best met the customer's needs. It's also been claimed that they had a tendency to flagrantly exaggerate the attributes of certain items just to make a sale.

Customer impressions of the AHC operation seem to vary widely. There are many stories about their seeming lack of business ethics as epitomized by the G.H.Q. and slag engine eras. A commonly-expressed view among those who actually visited their store is that while their prices were good, in-store customer service was non-existent. Staff were allegedly known to pressure customers into buying the items on which the store had the highest profit margin, whether or not they best met the customer's needs. It's also been claimed that they had a tendency to flagrantly exaggerate the attributes of certain items just to make a sale. As far as I’m aware, the only examples of the AHC known to be in existence today are the replicas produced by the Motor Boys and their associates/successors as well as a few more examples made by talented enthusiasts such as my mate Peter Valicek. Since there are very few of those, the chances of having an opportunity to acquire one are probably rather small. However, if you do find one (as I did on eBay), it will be a top-quality product which will be a pleasure to run. I wouldn't recommend flying one, though - the engine is pretty fragile and its chances of surviving any kind of meaningful contact with terra firma are minimal! And then there's that vibration ..............plus the power output is very much on the marginal side.

As far as I’m aware, the only examples of the AHC known to be in existence today are the replicas produced by the Motor Boys and their associates/successors as well as a few more examples made by talented enthusiasts such as my mate Peter Valicek. Since there are very few of those, the chances of having an opportunity to acquire one are probably rather small. However, if you do find one (as I did on eBay), it will be a top-quality product which will be a pleasure to run. I wouldn't recommend flying one, though - the engine is pretty fragile and its chances of surviving any kind of meaningful contact with terra firma are minimal! And then there's that vibration ..............plus the power output is very much on the marginal side.