|

|

Commercial British Model Engine Fuels of the “Classic” Era

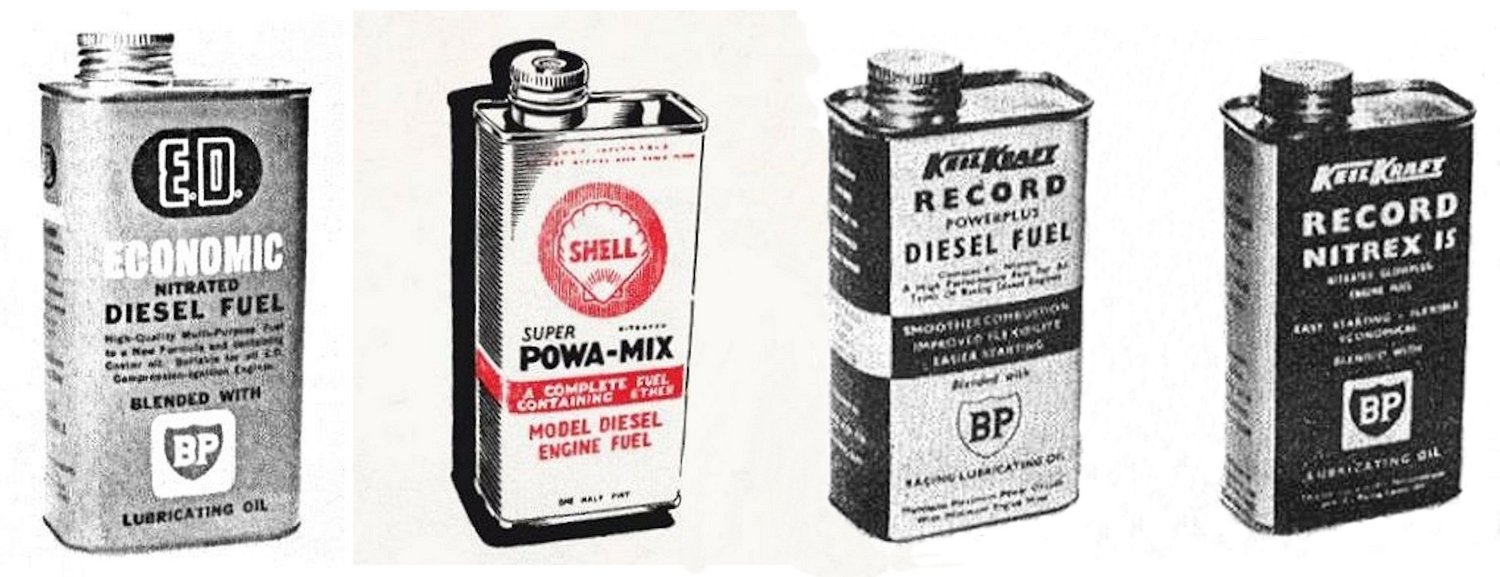

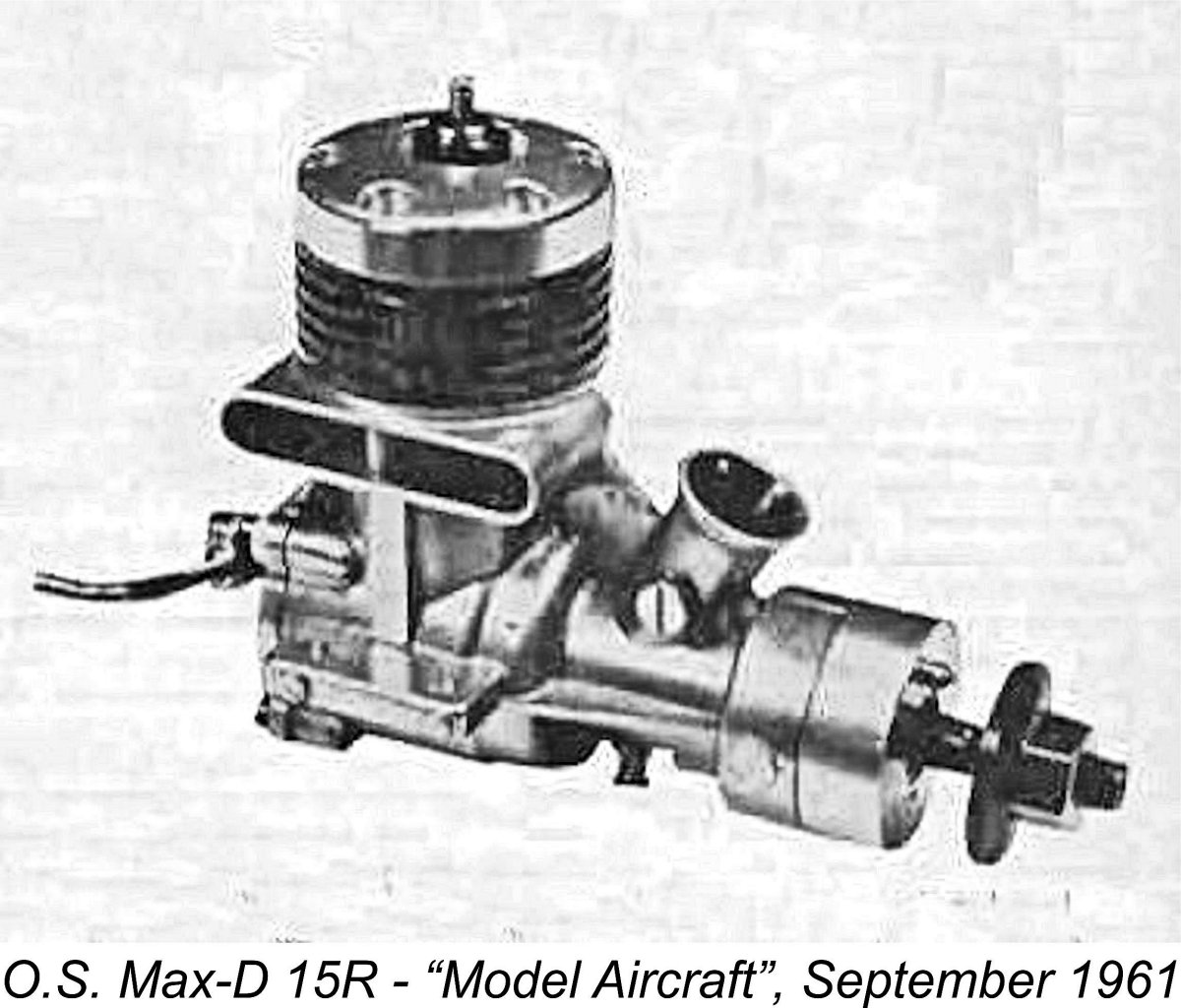

Typically, people seem to want to know when specific fuels first became available, what constituents were included in the blend and in what proportions they were included. The first point is straightforward enough - just follow the advertising and media trails. The issue of fuel composition is less clear-cut - for obvious reasons, competitive pressures induced fuel manufacturers to play their cards close to the chest when it came to releasing the specifics of their commercial fuel formulations. Moreover, fuel compositions tended to change over time. Nonetheless, some details did leak out periodically. It’s clear from the record that the supply of model engine fuels was viewed as a potentially lucrative business in Britain during the “classic” era, which I define as the period up to the early 1970’s when Schnuerle porting pretty much took over from earlier technologies. Unless you’re part of the generation that grew up and started modelling in the 1940's and 1950's, it’s difficult to fully grasp the sheer scale of the aeromodelling market that existed back then. It was a time when you would be hard pressed to find any teenage boy who didn't build model airplanes of one sort or another. Indeed, many Dads were also involved - aeromodelling wasn't just for kids! The fuel side of this market was significant enough for major oil companies like Esso, Shell, BP and Caltex to be openly involved and eager to have their logos displayed on the containers and in the advertisements. The domestic brand-names under which fuels were sold at various times in Britain during this period included Allbon, Mercury, KeilKraft, Shell/FROG, E.D., J.B., Mills, Quickstart and others.

As a result of Gordon’s efforts, he was able to provide me with a significant body of “period” reference material relating to the subject of fuels. I still faced the somewhat daunting challenge of wading through it all to organise the information and assemble it into a readable text, but I couldn’t even have begun to do so without having the results of Gordon’s research at my fingertips. It’s no exaggeration to say that without Gordon’s help, this article would not have been written. Thanks, mate! Here I intend to summarize what can be learned from all relevant sources about the availability and composition of the various commercial fuels, both diesel and glow, which were marketed in Britain during the period with which I am concerned. I’m under no illusions regarding the likely level of interest in this subject - most of my readers are far more interested in engines than in the fuels on which they ran! So I accept that many people won’t bother to plough through this rather specialized material. Even so, I see value in the creation of a reference document in which anyone interested can find out what is known about a particular British commercial fuel from the “classic” era. No-one has to read this stuff, but the information is now assembled and readily accessible for those interested. I’ll begin by briefly summarizing the history of the development of model engine fuels during the pioneering era leading up to the appearance of the first widely-available diesel and glow-plug motors in Britain. Early References

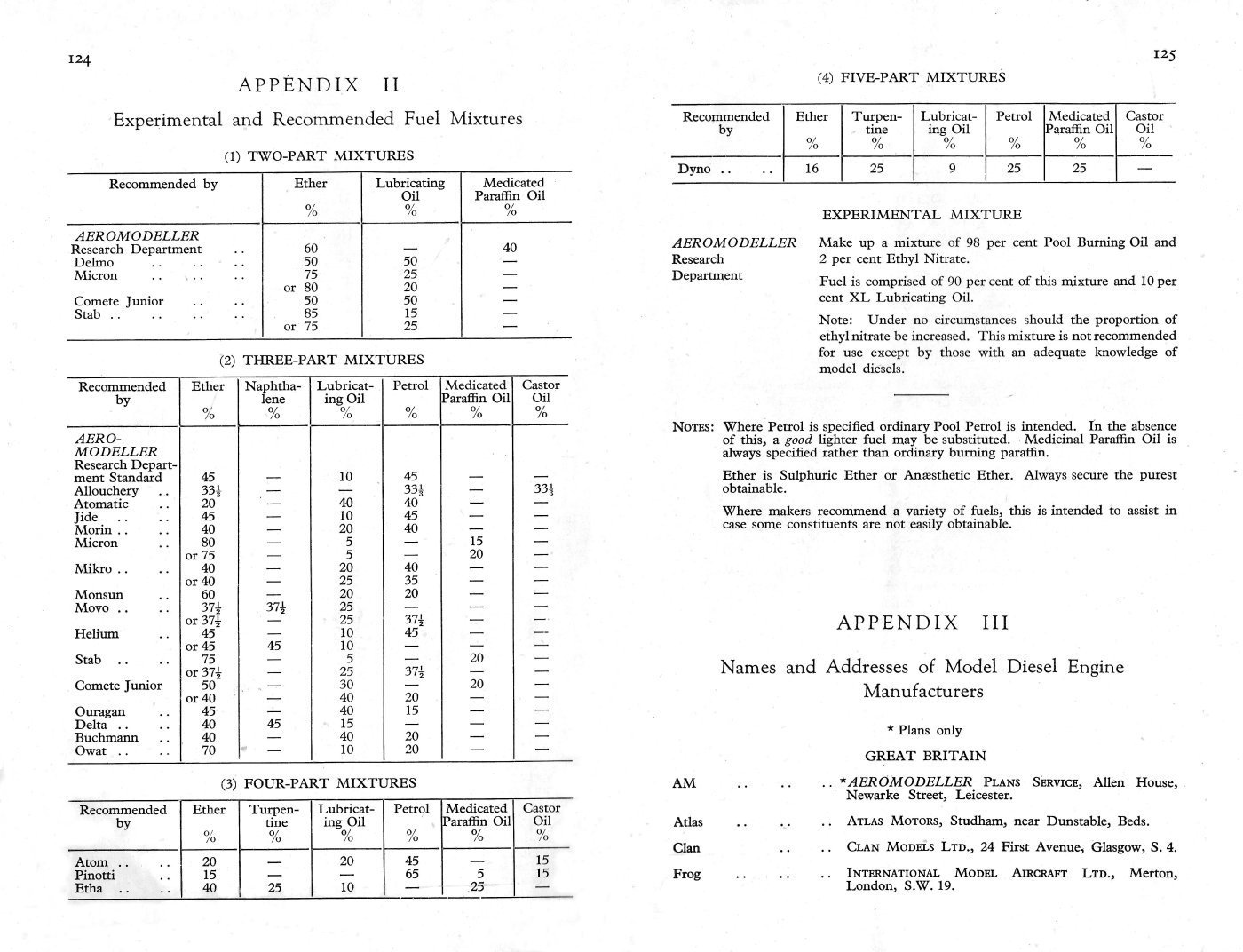

As all-out racing engines began to appear in America during the early 1940’s, it was found that methanol-based fuels provided both more power and improved internal cooling. Consequently the use of such fuels became quite common in contest circles, often in conjunction with castor oil lubricant. However, the average modeller still used plain old white gas and mineral oil - castor oil doesn't mix with gasoline. The first development that raised model engine fuel experimentation to a new level was the late 1930’s appearance in Europe of the compression ignition (aka “diesel”) engine. It was quickly found that the unusually low self-ignition temperature of di-ethyl ether (188 °C) greatly reduced the compression ratio requirements to achieve auto-ignition in the absence of a Because of the British involvement in WW2 from September 1939 onwards, Britain lagged well behind many other European countries when it came to the development of model diesels. It was not until after the mid-1945 conclusion of WW2 that diesel development in Britain really got under way. By that time, model diesels had been in regular use in some other European countries for 3 or 4 years. The Brits had some catching up to do! Perhaps the first publication to provide useful information on model diesels to British power modelling enthusiasts was an in-depth article by Lawrence H. Sparey entitled “The Gen on Diesel Engines” which appeared in the December 1945 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. This article focused on the design, construction and operating principles of model diesels, specifically omitting any discussion of suitable fuels. That topic was treated separately by Squadron Leader Peter Hunt in a subsequent article which was published in the March 1946 issue of the magazine. Hunt recognized the value of ether in the creation of a fuel mixture having a sufficiently low self-ignition temperature for model engine use. However, he viewed high-octane gasoline (referred to by the Brits as "petrol") rather than kerosene as the most appropriate base fuel, with the ether being present solely to initiate combustion. He cited the tendency of ether to detonate rather than burn smoothly, noting that the lubricating oil did much to moderate this tendency. Interestingly enough, he also recognized the need to find a suitable accelerant which would reduce ignition lag, a role which would later be filled by such substances as amyl nitrate, ethyl nitrate, amyl nitrite, iso-propyl nitrate and 2-ethylhexyl nitrate (Amsoil Cetane Boost). At his time of writing, the use of these additives had yet to be developed, but the concept had already presented itself.

Perhaps significantly, all of the cited fuel mixtures contained ether, although kerosene (which the Brits called paraffin) was beginning to supplant gasoline (petrol) as the base fuel. Equally significantly, the “Aeromodeller” research department had begun to experiment with the use of ethyl nitrate as an ignition improver. By the second half of 1947 when Colonel C. E. Bowden published the first edition of his book entitled “Diesel Model Engines”, matters had progressed even further. Kerosene (aka paraffin) had taken over from gasoline as the “standard” base fuel, while the use of amyl nitrate as an ignition improver had now become more or less standardized. However, a proportion of ether was still considered to be an essential characteristic of any successful model diesel fuel.

Gordon Beeby has proffered the entirely logical suggestion that the marketing of these early diesel fuels that needed ether added by the customer was prompted by the fact that blending the fuel without ether would have allowed it to be supplied by mail order. Fuels containing ether were considered to be too flammable to allow safe transmission through the mail, and with good reason. As model shops proliferated along with well-organised trade distribution networks to supply them, this consideration became largely irrelevant. Of course, it was only a short step from these “partial mixtures” to an over-the-counter commercial fuel that came complete with ether and could be used straight out of the container. We’ll look at the various brands which soon began to appear in the following sections of this article. Meanwhile, the fuel picture was greatly expanded by the November 1947 introduction of the miniature glow-plug in America. The new technology quickly spread to Britain, prompting the development of commercial fuels for these engines - diesel fuels now had to share the hobby shop shelves with their glow-plug equivalents. The methanol-based fuels which had been used for some years in competition spark ignition engines had been found to work very well with glow-plug ignition, so there was no new technology there. The major innovation in the context of glow-plug fuels was the rapid recognition of the benefits of the use of nitro-paraffins such as nitromethane and nitrobenzene in such fuels. Both Ray Arden and the Dooling brothers had commenced experiments with nitromethane (aka nitro) in late 1947, with very positive results. By early 1948, Ray Arden had introduced a revolutionary new fuel called Arden Formula B, containing 37.5% nitro, 37.5% methanol and 25% castor oil. However, this potent-sounding mixture was not available in Britain. Having set the stage for the development of a highly competitive British trade in ready-to-use commercial model engine fuels, we’ll now commence a review of the various brand-names under which such fuels appeared. To make the information on specific fuels more readily accessible, I’ve chosen to deal with the various fuel brands separately rather than try to develop a single timeline covering all available fuels simultaneously. If you're interested in a particular brand of fuel, just scroll down until you find it. Mercury Fuels It's clear that Henry J. Nicholls, owner of the Mercury brand-name, was quick to appreciate the commercial potential of offering ready-mixed fuels to his customers. In July of 1948 he introduced Mercury Blended Fuels nos. 1 through 5 to “Aeromodeller” readers. In September 1948 the range was expanded to include Mercury no. 6, an etherless ready-mixed diesel fuel. Mercury no. 7 nitro/methanol racing glow fuel made its appearance in October 1949, and the range was completed in April 1950 with the addition of Mercury no. 8, a pre-mixed ether/kerosene castor-based high performance diesel fuel. The 1948 second edition of Colonel Bowden’s previously-cited book included a reference to Mercury no. 6 etherless diesel fuel, stating that it was best for fully run-in and completely freed-up engines. Henry J. Nicholls himself made a similar comment on Mercury no. 6, stating that it "....runs rather hotter than etherised fuel. It is better to "run in" a new engine on etherised fuel..." He also stated his view that etherless fuel was unsuitable for really small motors. These comments appear to have created a somewhat negative impression in the minds of the fuel-buying public, because the September 1948 issue of “AeroModeller” carried a Mercury advertisement claiming that Mercury no. 6 had been “improved” to make it suitable for running in a new engine. It’s unclear how this was achieved. Perhaps it included an increase in the oil content. This advertisement also stated that Mercury no. 6 was a blend of 6 components, none of which was ether, nor did any ether have to be added.

The two grades of glow fuels were cited as “Mercury Competition Glow Plug Blue Label” and “Mercury Racing Glow Plug Magenta Label”. The first blend was cited as being suitable for engines having compression ratios up to 8 to1. It reportedly used a gasoline base as opposed to methanol, also featuring Esso Racerlube mineral oil. The second formula was more conventionally methanol-based and used castor oil lubricant. It was intended for use in engines having compression ratios over 6.5 to 1. The major modelling periodicals of the day shied well clear of publishing any head-to-head comparative analyses of different commercial fuels. Doubtless this strategy was adopted to minimise any possibility of upsetting a major advertiser. A detailed two-part article on the subject of model engine fuels appeared in the March/April 1950 issues of “Aeromodeller” magazine, without reviewing any specific brands of fuel. This article essentially confined itself to a detailed summary of the state of knowledge relating to model engine fuels as it then stood. It makes it clear that the properties, function and effectiveness of the various constituents were quite well understood by that time. This article seems to have prompted a further reaction from Mercury. Both the July and August 1950 issues of “Aeromodeller” included full-page Mercury ads in which the full range of fuels now being offered under the Mercury label were listed. These were as follows:

Later information confirmed that no. 3 required the addition of ether, as had been the case with the earlier Mills and Shell fuels mentioned previously. No. 6 was an etherless fuel, at least at this stage. The 1951 third edition of Col. Bowden’s previously-cited book includes the following comment (possibly a hold-over comment from the 1948 edition): “Mercury No 6, "All-in-One", requires no ether to be added, and does not have ether incorporated. I seldom use any other fuel for all but the baby motors, because it saves so much trouble, and there is no ether to evaporate." The “trouble” to which the Colonel was referring was evidently the need to add ether to the mix prior to use. He was clearly harking back to the “add ether” fuels from Shell and Mills. This is confirmed by another comment in the same book. This comment definitely dates back to 1948, since it refers to the “new” Mercury no. 6. "As an instance of a non-etherised fuel, the new "Mercury No. 6" has been blended by the Anglo-American Oil Company and starts very well. The fuel is composed of six components and literally does not function correctly if any one of the ingredients is not included. It has a lower fuel consumption than a normal etherised fuel, and I have found it starts a diesel engine surprisingly easily, producing outstanding power. I use it a great deal because of the trouble in obtaining ether."

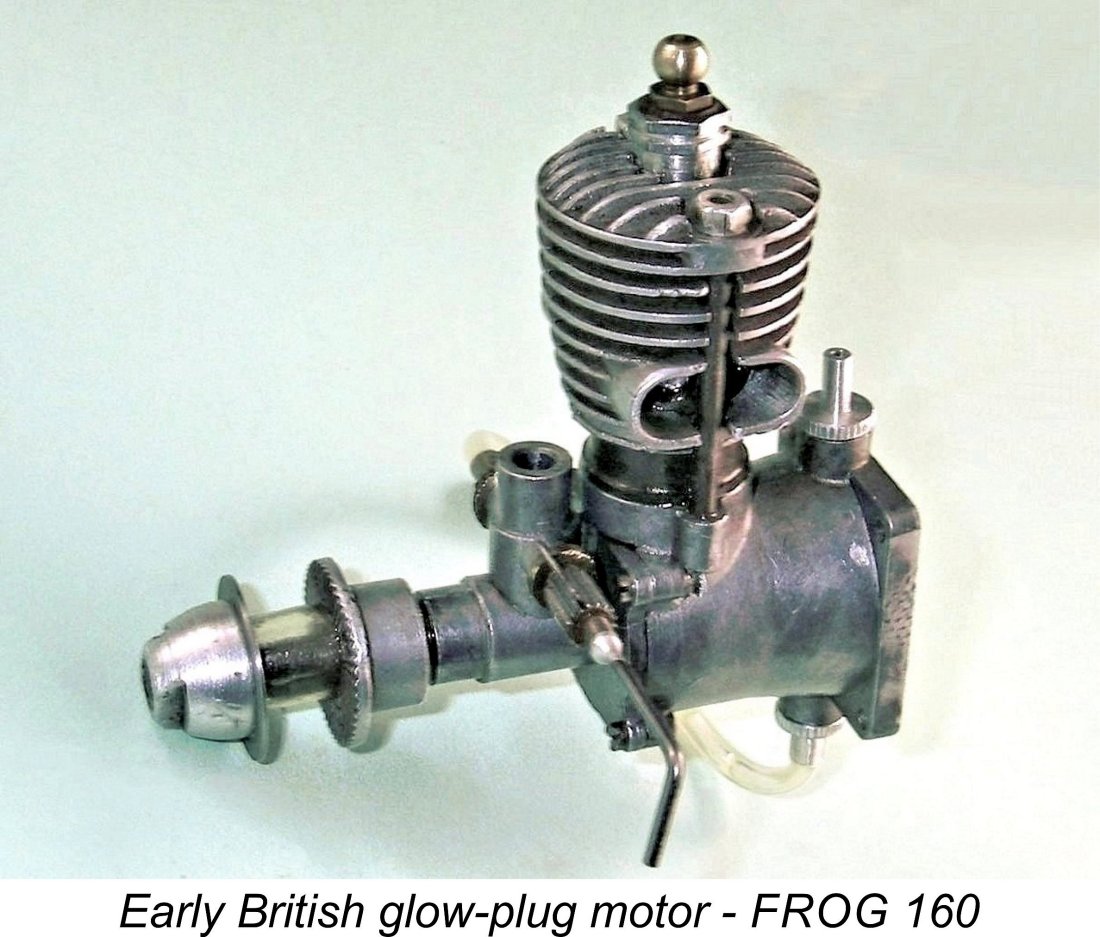

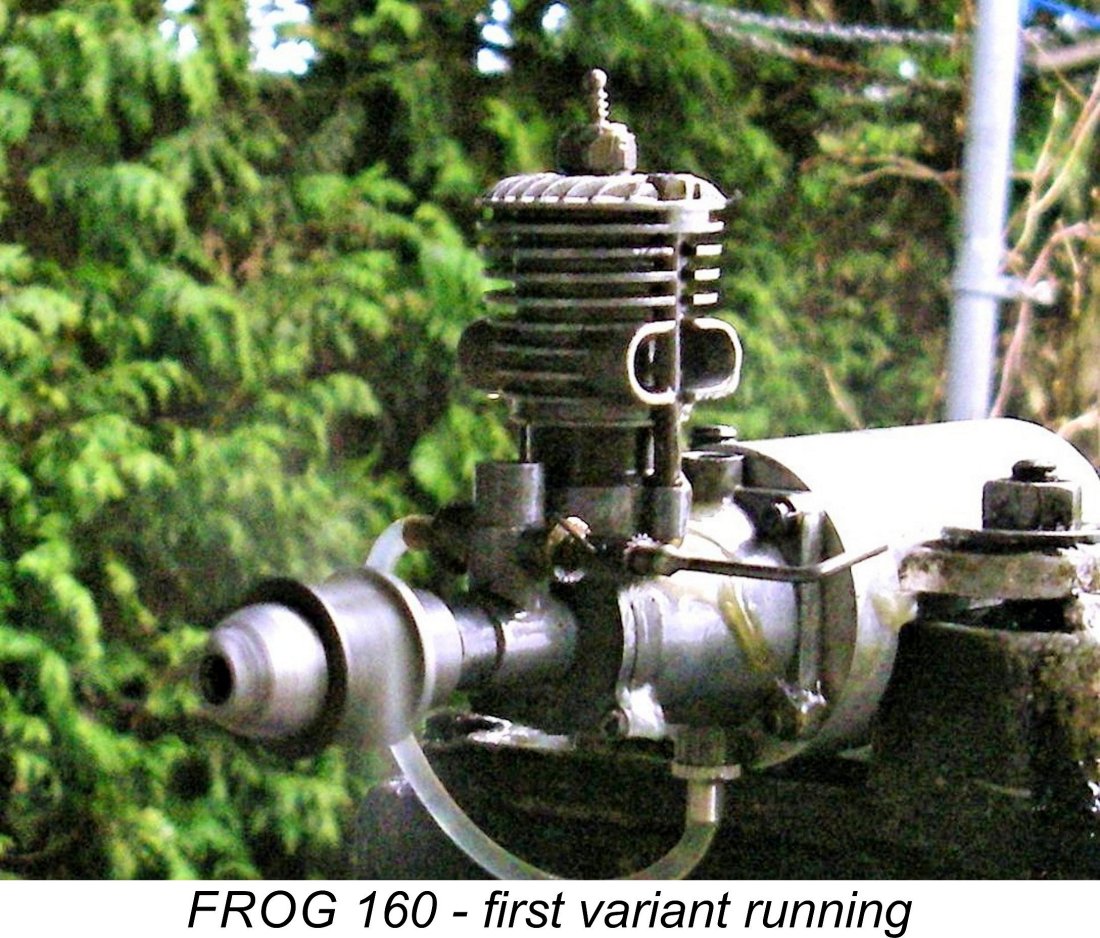

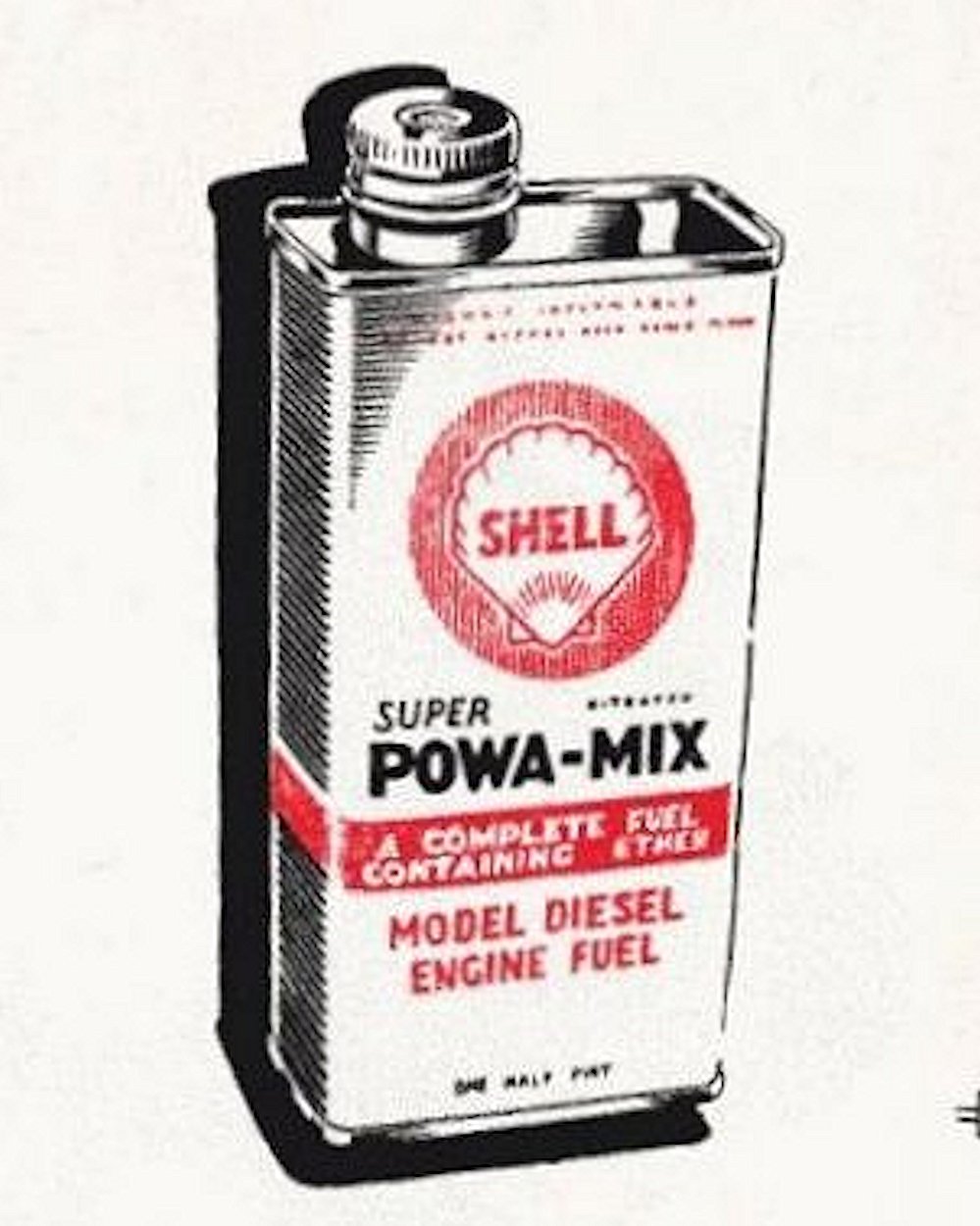

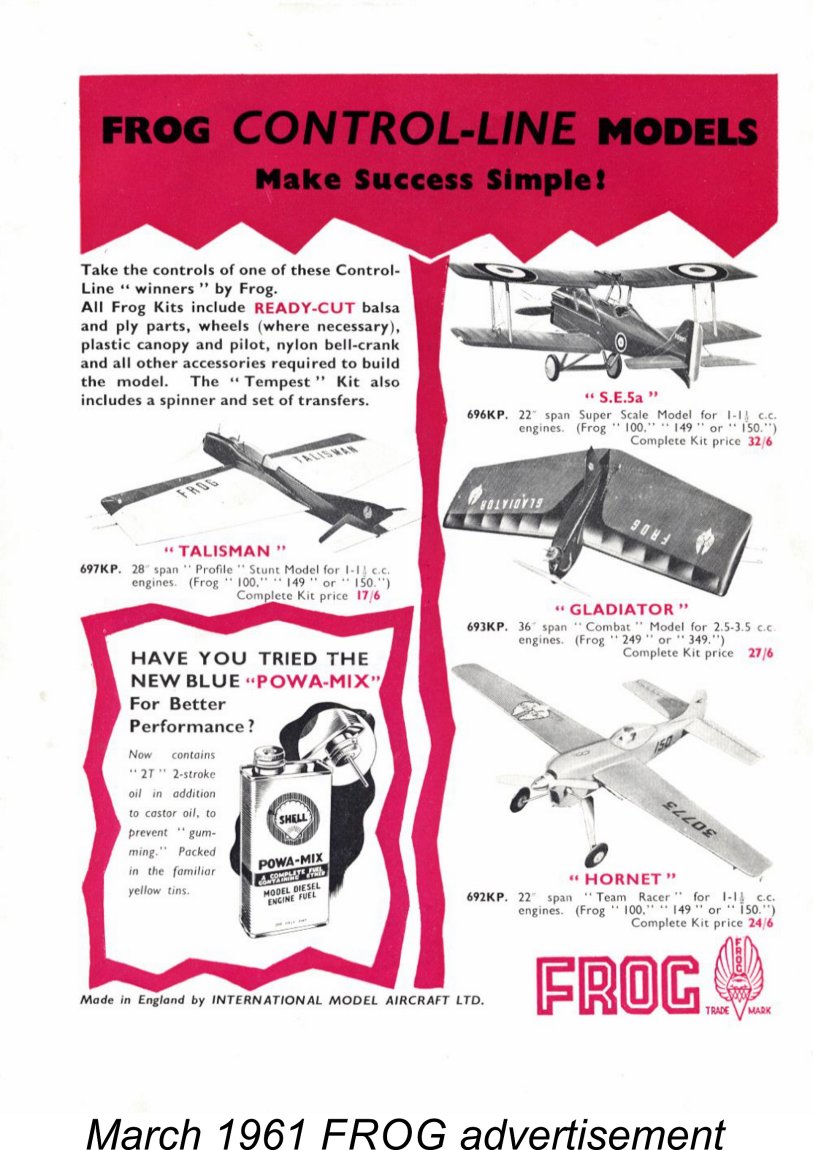

That said, at least one other company (International Model Aircraft - FROG) actively promoted it’s Powa-Mix etherless fuel mixture from mid 1951 onwards (see below). This seems to have had limitations which were recognized even by the manufacturer - the August 1952 “Aeromodeller” test of the FROG 50 made specific reference to the manufacturer’s own statement that etherless fuels were not suitable for that engine on account of the increased compression setting required. Colonel Bowden evidently shared the opinion that such fuels were unsuitable for use in the smaller engines. This makes it clear that while etherless fuel mixes were not an unknown concept, the limitations of such fuels were clearly recognized. Certainly, they never really caught on back in the day - Shell/FROG and Mercury were the only brands under which such fuels were ever offered commercially. Nonetheless, the increasing difficult of obtaining ether in recent years has resulted in renewed interest in the possibility of creating an effective etherless diesel fuel. This has led to a great deal of speculation and experimentation regarding the possible constituents of such a fuel. No hints were ever dropped on this topic back in the day. Perhaps the best clues may be found in the late Brian Winch’s 2017 articles in “AeroModeller” and “Airborne” magazines. It seems likely that the etherless blends used a light naphtha or light gas oil with an auto ignition temperature of around 220-240 °C, somewhat higher than the corresponding figure of 188 °C for ether and hence requiring a higher compression setting, at least for starting. It would also tend to make the engine run hotter, in accordance with the previously-quoted comment from Henry J. Nicholls. That said, Gordon Beeby has had a measure of success with an etherless fuel containing 3 parts of kerosene, 1 part of “Shellite” naphtha and 2 parts of Coolpower Blue synthetic oil. It seems that etherless fuels are at least a viable possibility, although I’d feel more comfortable with a lubricant other than synthetic oil in a diesel application. I also wonder if an ignition improver would enhance an etherless fuel like that tried by Gordon. Room for experimentation there! Regardless, Gordon's well-substantiated opinion is that if you still have access to ether-based fuels, experimentation with etherless blends probably isn't worth the bother. Colonel Bowden’s previously-cited comment that Mercury no. 6 was an etherless fuel containing 6 components, all of which had to be present, raises the possibility that other combinations of additives were used to enhance the usability of such fuels. Kerosene, lubricating oil …… and 4 other essential components! What could they have been? Information is frustratingly scanty - relatively little effort seems to have been expended in pursuing the etherless fuel concept once the distribution of ether fuels ceased to be a problem.

Development work was in fact continuous. In April 1953 a new formulation called Mercury no. 6R was both advertised and described in the “Trade Notes” feature of that month’s “Aeromodeller”. The “R” signified the fact that this was touted as a “racing” variant of Mercury no. 6. It reportedly contained a proportion of Redex mineral-based upper cylinder lubricant, perhaps to minimize the formation of castor oil gum. It may or may not have continued to be an etherless fuel - no information was provided on this issue. 1953 also provided several indicators in relation to the actual composition of a few commonly-used Mercury fuels. The July By December 1953 the number of Mercury fuels available to the British modeller had expanded to 9. The use of different colours for the labels had been maintained. The list now consisted of the following:

Ether was also available separately from Mercury.

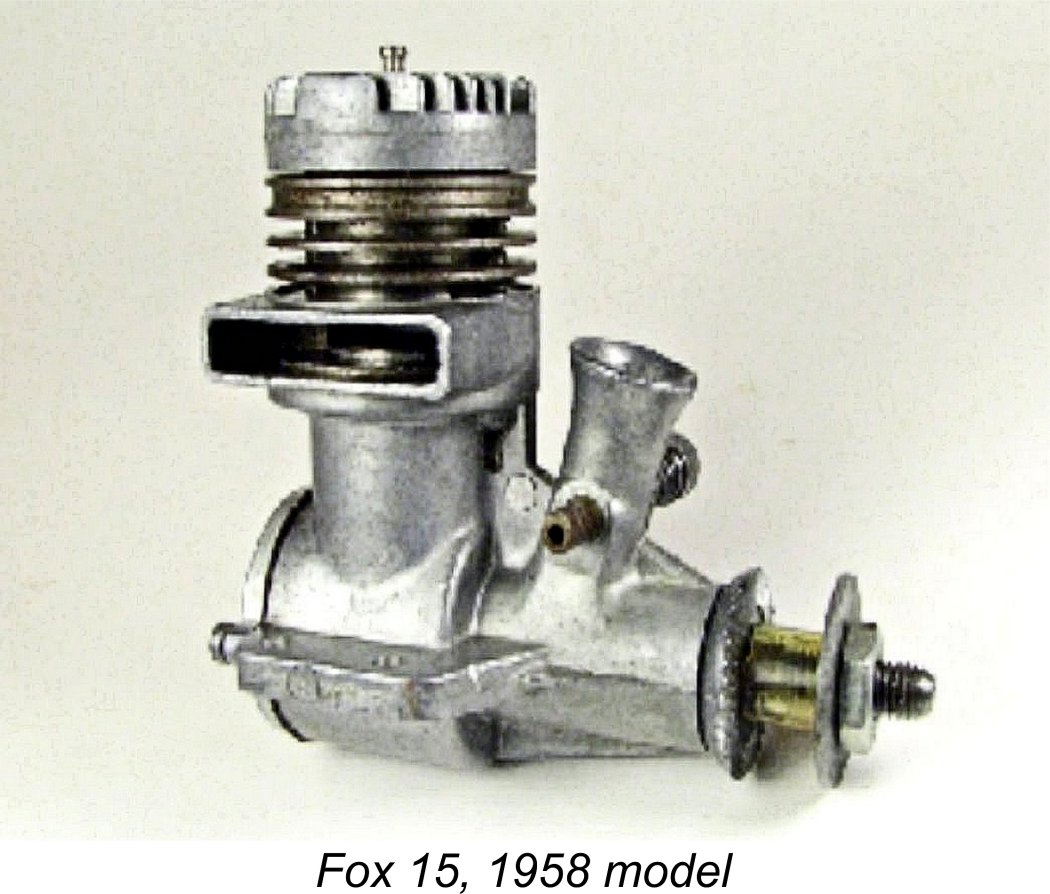

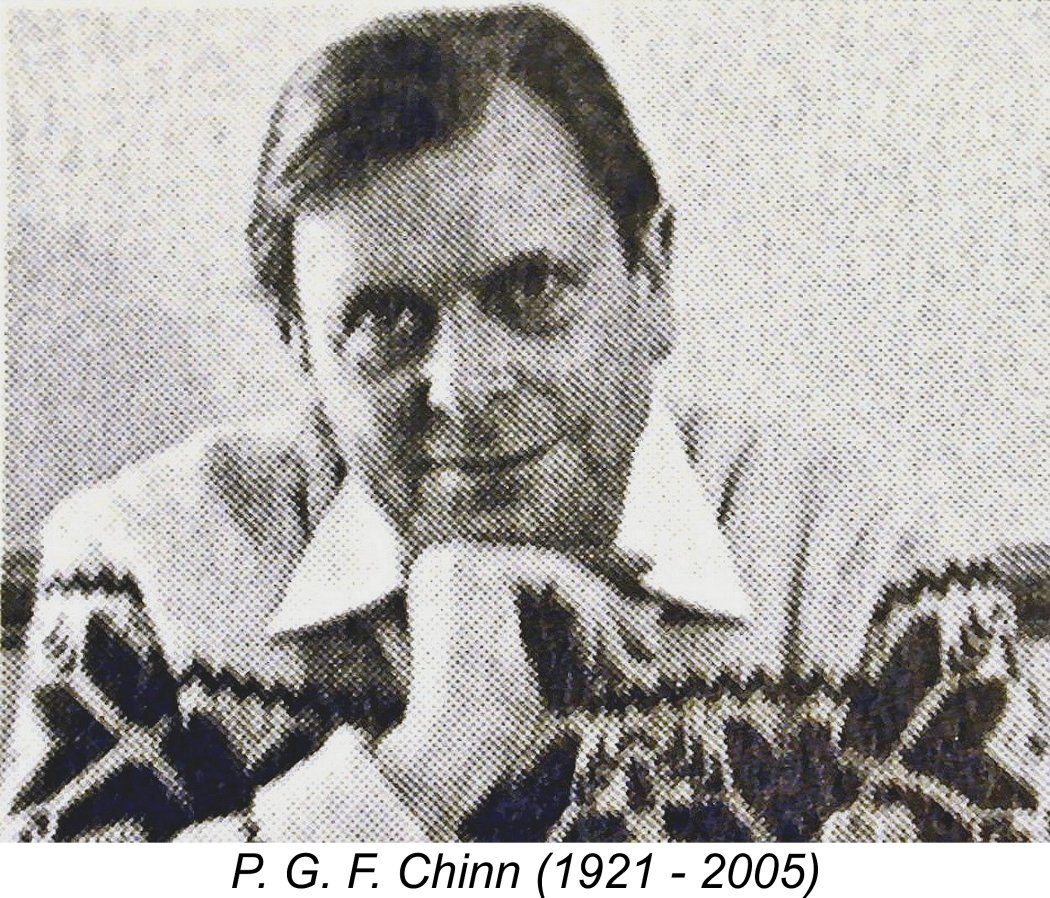

The list of Mercury fuels didn’t remain static in terms of either diversity or formulation. The October 1954 “Aeromodeller” test report on the A-M 25 referred to the forthcoming introduction of Mercury Racing Diesel (RD) fuel containing 40% paraffin, 37% ether, 20% castor oil and 3% amyl nitrite (not nitrate). By comparison with Mercury no. 8, the oil content had been reduced while both the ether and ignition improver contents had been increased. This fuel duly made its appearance, being advertised in the November 1954 issue of “Aeromodeller” and being described in the “Trade Notes” feature of the same issue. A topic which attracted a good deal of attention during this period was that of gum formation. This subject was discussed in some detail in Peter Chinn’s article entitled “Diesel Miscellany” (“Model Aircraft”, January 1955) and again in the February 1958 article in the same magazine entitled “Fuels and How to Make Them”. The brand of commercial fuel involved in creating the described conditions was not named - why risk upsetting a valued advertiser? However, it may be significant that the The gum issue was likely also behind the September 1958 advertising announcement of the appearance of Mercury Super 6 which replaced the former no. 6 blend. Like its Mercury no. 6 predecessor, this was specifically stated to be an all-inclusive “economy” blend requiring no addition of ether. This rather ambiguous statement isn’t much help, since it could mean either that the fuel was etherless or that no ether had to be added because it was already there in the mix as sold! More significantly, Mercury Super 6 was cited as being mineral oil-based - end of gumming problem! The Super 6 blend was highlighted both in the “Trade Notes” column in the December 1958 issue of “Aeromodeller” and also in the “Over the Counter” feature of the February 1959 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The latter article noted the requirement for increased compression with this fuel, possibly implying that it was still an etherless blend. During the period described so far, the rest of the Mercury fuel range had presumably continued more or less unchanged. That said, it seems almost certain that Mercury no. 1 and no. 2 spark ignition blends had fallen by the wayside by this time due to absence of demand. No. 3 had likely also left the stage - by 1958 no-one would have expected to have to add ether. By this time, Castrol had replaced Esso as the oil supplier for Mercury fuels. In December 1958 yet another new Mercury blend was announced. The Mercury advertisement in the December 1958 issue of “Aeromodeller” included a new glow-plug formulation called Mercury 45. Although this can’t be proved, it seems not unlikely that the name stemmed from the fact that this fuel replaced both Mercury no. 4 and Mercury no. 5 glow fuels in the range. Some hint as to the composition of this fuel may be obtained from the July 1964 “Aeromodeller” test of the Fox 15 R/C and the September 1964 test of the Enya 09-II R/C in the same publication. In both cases, the fuel used in the tests was specifically cited as Mercury 45, while the texts of both articles strongly implied The formulation of the established Mercury blends clearly changed over time. For instance, the test report on the Fox 15 which appeared in the July 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller” specified the fuel used as Mercury no. 7 and characterised this fuel as containing 13% nitromethane. It may be recalled that Mercury no. 7 was cited as containing 20% nitro as of mid 1953, so it appears that the nitro content had been reduced. This was almost certainly driven by considerations of both cost and availability of nitro in Britain. A review of the available literature confirms that during the latter part of the 1950’s the supply of nitromethane in Britain more or less dried up. The issue was the subject of some discussion in the “Over the Counter” feature of the February 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”, which provided some useful background information. It seems that laboratory nitromethane had previously been manufactured in Britain. However, the increasing availability of less expensive nitro from America had led to the cessation of British manufacture. All well and good, but at some later point in time the importation of nitro from the USA was embargoed by the various transportation companies, presumably for safety reasons. This left British fuel manufacturers and power modellers without a source of nitro. The article stated that an unspecified alternative source was eventually found, but at a significant increase in the cost of an already-expensive commodity. This explains the efforts of a number of British commercial fuel manufacturers (including Mercury) either to reduce the nitro content in their fuels or to try different additives which might do something to take over the function of the nitro. Unfortunately, one of the alternatives which came into fairly widespread use at this time was nitrobenzene - a truly scary thought, since nitrobenzene is now known to be a powerful carcinogen as well as being highly toxic and readily absorbed through the skin. I have little doubt that more than a few modellers from this era paid heavily for their fun down the road…………… The nitro supply situation in Britain was not eased until late 1962, when an announcement appeared in the “Motor Mart” feature of the December 1962 issue of “Aeromodeller” to the effect that domestic manufacture of nitromethane had then just resumed. The manufacturers were L. Light & Co. Ltd. of Poyle Colnbrook in Buckinghamshire. Accordingly, the nitro supply shortage that had afflicted British power modelling was expected to be alleviated in very short order. The stuff was still expensive - a 1 kg. tin (around 877 cc or 1.5 pints) sold for £2 5s 0d (£2.25). By way of comparison, a half-pint of Record Methanex glow fuel (see below) sold for £0 3s 6d (£0.18). By 1962 the somewhat bewildering array of different fuels available under the Mercury banner had been rationalized to a certain extent. A Mercury advertisement in the January 1962 issue of “Aeromodeller” listed only Mercury no. 6, Mercury no. 8, Mercury RD, a new product called Mercury Marine Diesel and Mercury 45 as being available. Of course, this doesn’t necessarily mean that these were the only Mercury blends then available - it may merely reflect their best-selling fuels at the time. At some point in the mid-1960’s, KeilKraft took over as the major distributor for Mercury fuels, adding them to their existing Record fuel range (see below). This arrangement was highlighted by a large advertisement for Mercury fuels which appeared in the May 1965 issue of “Aeromodeller”. However, things were tapering off somewhat by this time as competing specialist fuel blenders began to assume a leadership role. The advertisements which appeared in the magazine’s March 1967 and November 1967 issues featured only the ever-popular Mercury no. 8. That November 1967 ad appears to have been the final Mercury fuel placement of them all. There’s not much more that we can say about the Mercury fuel range. All that I can personally recall from my own early years in power modelling is that these fuels were quite highly regarded and widely used. They served British power modelling well for 20 years. Shell/IMA/FROG Fuels

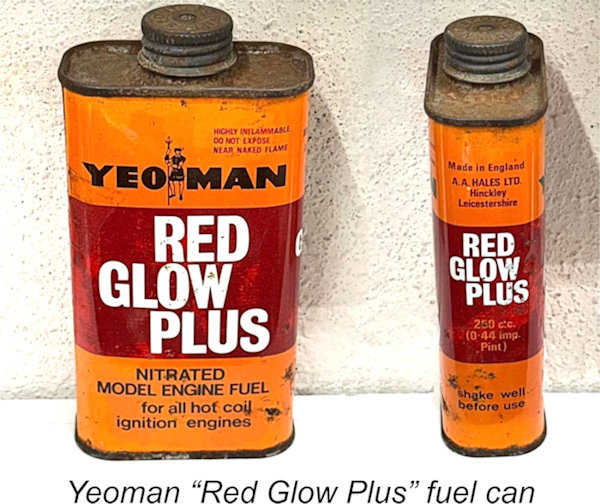

The original Shell/FROG diesel fuel appears to have been a simple blend containing equal parts of kerosene, ether and mineral oil (Castrol XXL was mentioned). At least, this was the manufacturer’s recommended mixture for the “bicycle spoke” FROG diesels of the late 1940’s. It was used in the June 1948 “Aeromodeller” test of the FROG 100 Mk. I. By 1949 Shell/FROG diesel fuel was being marketed under the trade-name “Powa-Mix”. This fuel was used by that name in the October 1950 “Aeromodeller” test of the FROG 100 Mk. II. The companion glow fuel was marketed under the name “Red Glow”. It was used in the In 1951 a revised etherless Powa-Mix formulation using mineral oil was introduced. Some performance information was provided in the “Trade Review” feature of the August 1951 issue of “Aeromodeller”. As discussed previously, etherless fuels were not viewed very positively by many modellers, particularly those using smaller engines, due to their higher-than-normal compression requirements. The etherless Powa-Mix does not appear to have been particularly well received - I recall a lot of older modellers It was doubtless the generally lukewarm reaction that prompted the early 1953 release of a further revised blend under the trade-name Shell/FROG “Super Powa-Mix”. This was a more conventional ether-based nitrated fuel incorporating castor oil. The nitrate content was variously given as 2% or 3% in a number of different published tests of FROG engines. This fuel was apparently further improved in 1955, now being characterised as "super nitrated” and sold in containers which were specifically labelled as "containing ether". IMA and Shell evidently wanted to distinguish this fuel from the earlier etherless Powa-Mix. At some point during the latter part of the 1950’s, the Shell/FROG glow fuel was also uprated to produce a new product called “Red Glow Plus”. Presumably this reflected the addition of some extra power-boosting ingredient(s) such as nitromethane, although there’s no information on the actual composition - Shell and IMA played their cards very close to their chests! This fuel was used in the test of the FROG .049 which appeared in the December 1959 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The January 1960 “Aeromodeller” test of the same engine hinted that Red Glow Plus contained 15% nitromethane, but this is not certain. The formulae for all of these fuels probably changed over time depending upon the price and availability of By the end of the 1950’s, IMA appear to have been marketing four different fuels simultaneously - Powa-Mix diesel, Super Powa-Mix diesel, Red Glow and Red Glow Plus. Advertising for these products appears to have been a bit on the sporadic side, however. All four blends never seem to have appeared together in the same advertisement at any time. In early 1961 Super Powa-Mix was re-formulated yet again. It now contained a proportion of Shell “2T” two-stroke oil along with the castor oil, presumably to reduce its tendency towards gum formation. The new blend was sold under the designation “New Blue Powa-Mix”, still in the trade-mark “Shell yellow” cans. The presence of the two-stroke oil gave the fuel a blue coloration, hence its name. It was used in the test of the FROG 80 Mk. II which appeared in the November 1961 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Somewhat unusually, this test included a brief review of the fuel. When A. A. Hales acquired the FROG line from IMA in 1962, they appear to have maintained the supply of FROG branded fuels. There are Hales advertisements in the late 1960's and early 1970's referring to FROG Super Powa-Mix and FROG Red Glow Plus. Illustrations show that the Shell logo had been removed and replaced with the familiar FROG logo which Hales now owned. That’s about all that I can tell you about the FROG model engine fuels of the classic era. If any reader knows more, don’t be shy! E.D. Fuels

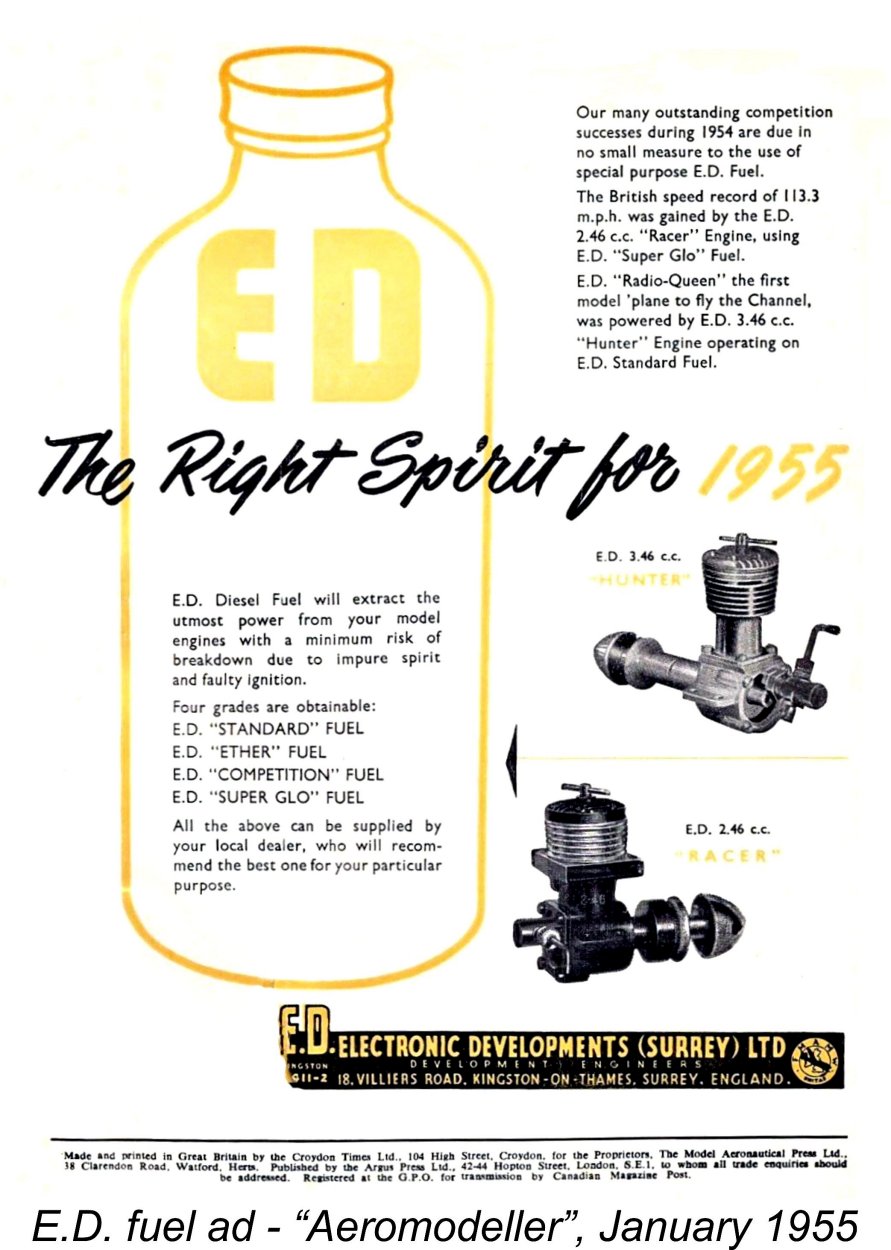

The E.D. “Standard” fuel was said to be suitable for use in engines during their running-in periods, while the E.D. “Competition” fuel was only to be used in well run-in engines. The claim was made that the latter mixture would add as much as 1,000 RPM to an engine’s speed on a given prop - a pretty large claim! Presumably the Standard brew was not nitrated and was heavy on the oil, while the Competition blend had a healthy dose of nitrate along with a lower oil content. Both fuels appear to have contained ether. Amazingly enough by today’s standards, E.D. fuels were sold in glass screw-cap bottles! Careful - don’t drop one! This practise continued throughout the 1950’s - I still recall buying bottles of E.D. diesel fuel from my local hobby shop in 1958! It must be pointed out that E.D. were far from being alone in the use of this type of packaging.

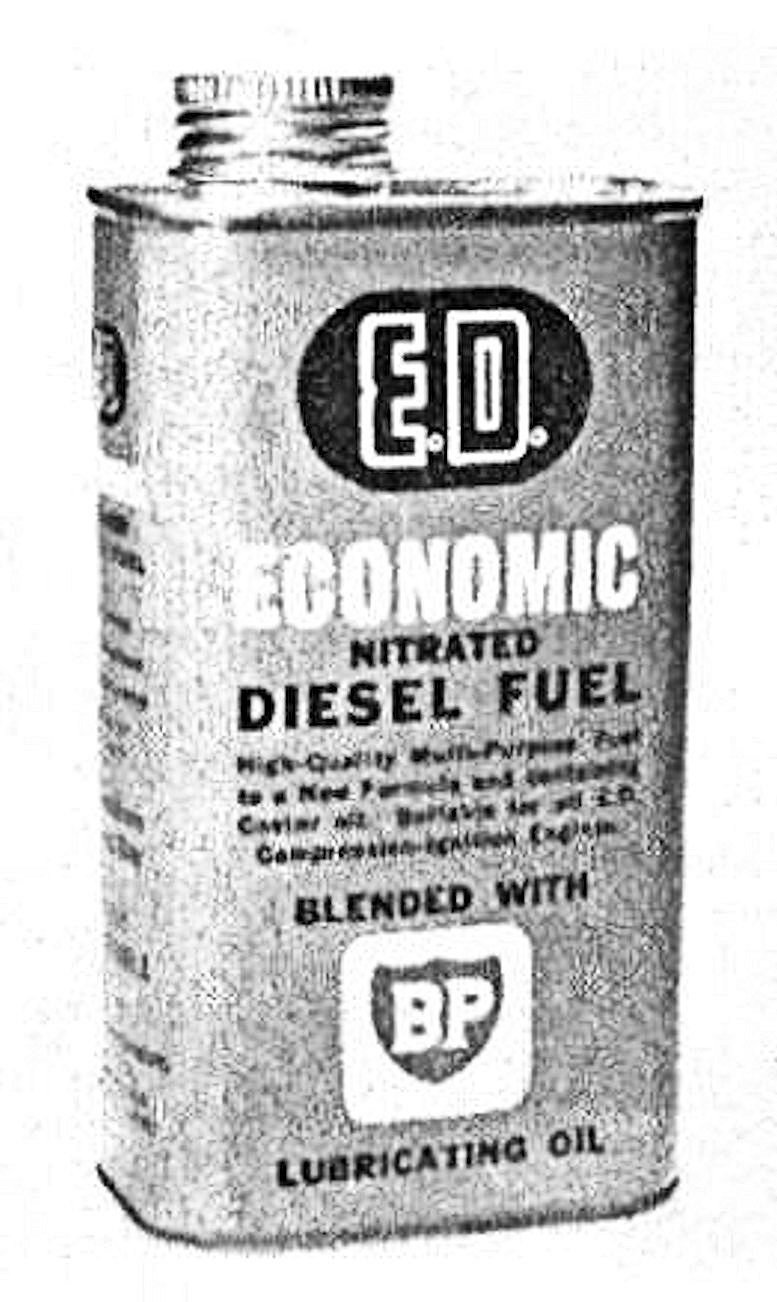

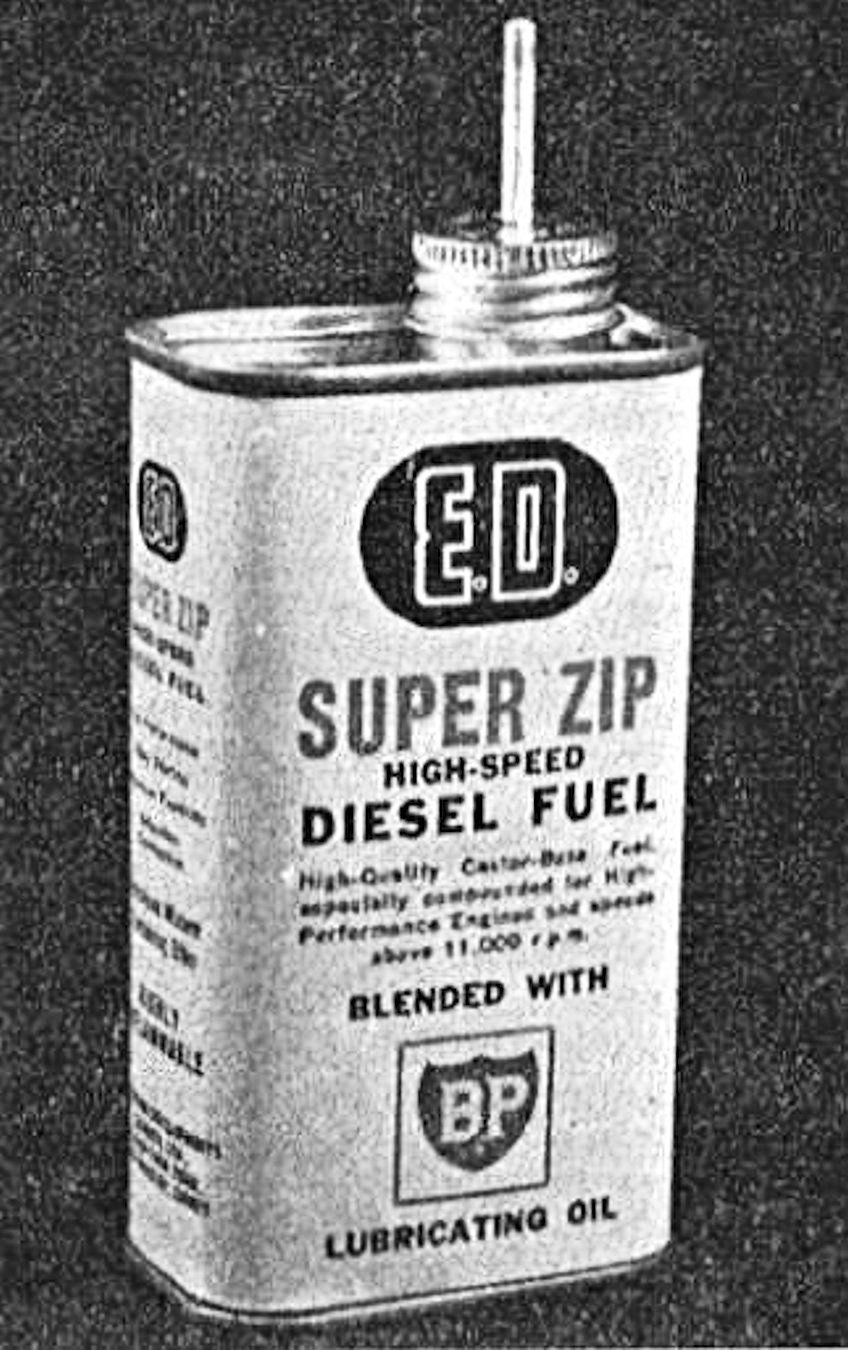

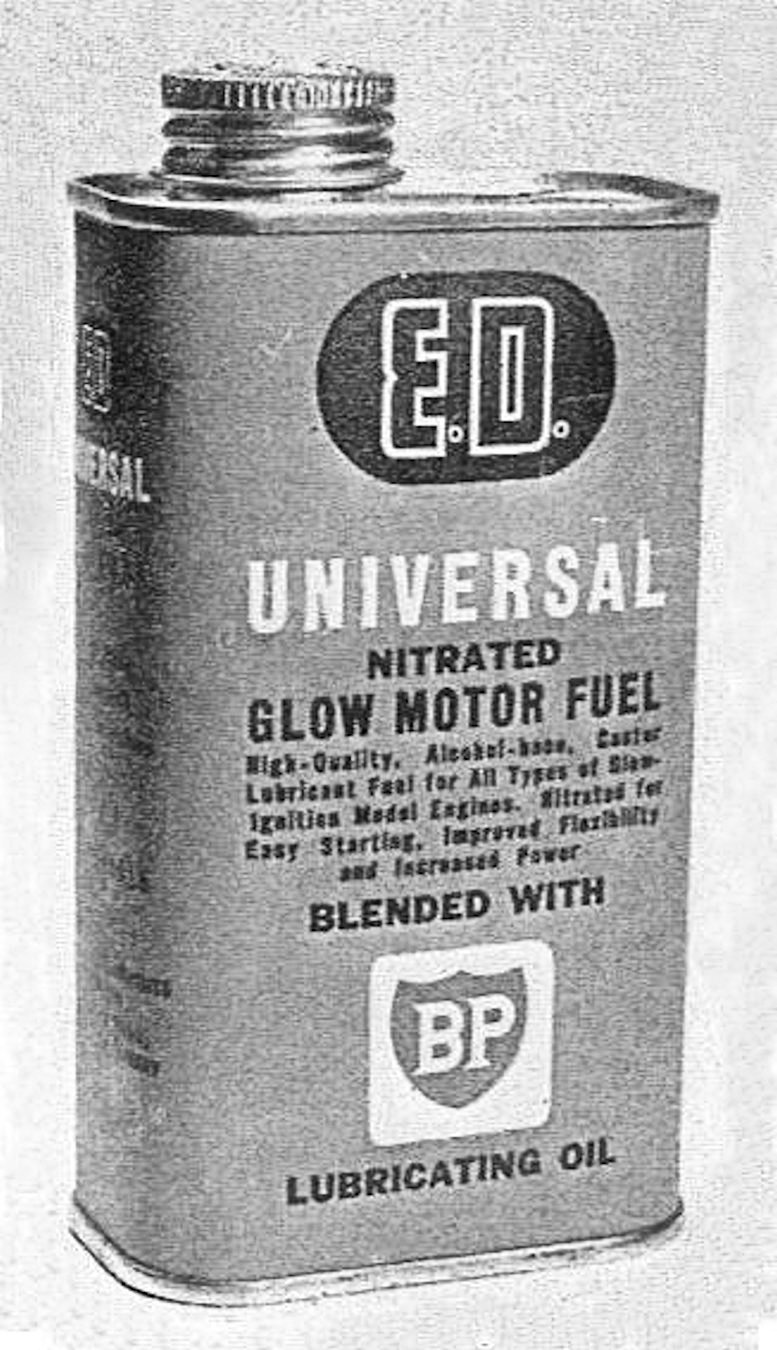

The E.D. fuels continued to be available into the early 1960’s. The E.D. “Standard” diesel fuel was re-formulated and re-named E.D. “Economic” in 1960. Also in the spring of 1960, yet another new high-performance E.D. diesel fuel made its appearance. This was E.D. “Super Zip”, a heavily nitrated blend which was intended to complement the newly introduced E.D. Super Fury and similar high-speed contest diesel engines. A review of this fuel appeared in the “Over the Counter” feature in the December 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Once again, no specific information was made available on its The final new fuel blend introduced by the original E.D. company was a castor-based blend marketed as E.D. Universal Nitrated Glow Motor Fuel. A review of this product appeared in the “Over the Counter” feature of the December 1961 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Very little information on this fuel’s composition was provided. However, one important piece of information was the fact that the then-current nitromethane shortage in Britain (discussed earlier) had forced the use of “another additive of the nitro-paraffin group”. The content of this was characterised as “not excessive”, allowing the fuel to be used for running-in purposes. It is to be hoped that this fuel didn’t utilize the highly carcinogenic nitrobenzene as its additive! More likely it was something along the lines of nitropropane, which was used at the time by a number of British fuel manufacturers as a nitro alternative. It was less effective than nitromethane, but at least it was available ……….. The disastrous fire of April 1962 which effectively put an end to the activities of the “original” E.D. company also ended that company’s involvement in the model fuel business. KeilKraft “Record” Fuels

Many of the KeilKraft fuels were identified by the inclusion of the name “Record” in their designations. The basis for this designation appears to be poorly understood - it has often been viewed as a mere promotional term, but was actually far more than that. It stemmed from the name of an earlier brand of fuel from which the KeilKraft range evolved. A very informative history of the development of these blends appeared in the March 1959 issue of “Model Aircraft”.

Material supply problems restricted output for a number of years, eventually forcing the termination of Powerplus manufacture. In 1956 the situation was relieved by a new manufacturer taking over, with KeilKraft becoming the sole distributors and Peter Chinn continuing to act in an advisory capacity. The ongoing venture was undertaken with the support of the BP petroleum company, whose name appeared on the labels along with those of KeilKraft and Record. The actual manufacturers of the fuels were never identified - they almost certainly weren’t KeilKraft. The first national advertisements for KeilKraft fuels appeared in the February 1958 and March 1958 issues of “Model Aircraft” and “Aeromodeller” respectively. A fairly detailed review of the KeilKraft diesel fuels appeared in the February 1959 issue of “Model Aircraft” in their “Over the Counter” column. The two blends mentioned were KeilKraft Nitrated Diesel Fuel and Keilkraft Record Competition diesel fuel. The latter blend reportedly contained 3% amyl nitrate while the former had only 1%. The other fuel constituents were adjusted accordingly.

The KeilKraft diesel fuels were accompanied by a couple of glow fuels which were marketed as “Record” blends. The previously-cited March 1959 review focused on two blends - Record Methanex and Record Super Nitrex. Both were methanol and castor oil based. Methanex was intended for running in and general purpose use, containing 30% castor oil and only 3% nitromethane. Super Nitrex contained no less than 30% nitromethane, hence being the most heavily nitrated glow fuel yet offered in Britain. It was intended for all-out high performance applications. Its oil content was not disclosed. The label specifically stated that Record Super Nitrex should not be used in new engines. It also noted that apart from all-out racing applications, the fuel was intended to be “tamed” somewhat for normal use by being mixed with a proportion of Methanex. At some point in 1959 KeilKraft decided to spare their customers the need to mix Methanex and Super Nitrex by releasing an intermediate grade called Record Nitrex 15. As the name suggests, this blend contained 15% nitromethane along with 25% castor oil. Another change which took place in 1959 was a slight amendment of the formulation of Keilkraft Record Competition diesel fuel. The nitrate content was raised from 3% to a somewhat intimidating 4%. The new blend was re-branded as Record Powerplus Diesel Fuel. It’s not clear whether or not the inclusion of a proportion of mineral oil was maintained.

A two-page KeilKraft advertisement appeared In the January 1960 issue of “Aeromodeller” which provided a limited amount of information on all grades of fuel then available from KeilKraft. These included:

The “Over the Counter” feature in the February 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft” included some commentary on KeilKraft Record fuels. After discussing the previously-mentioned nitromethane shortage which had confronted British fuel manufacturers, the article noted the various efforts to find a substitute additive, concluding that there was no equally effective alternative to nitromethane. The more expensive nitromethane then being obtained from another undisclosed source had forced a significant price increase for both Record Methanex and Record Super Nitrex. The same article noted the then-recent addition of Record Nitrex 15 to the range as well as the increased amyl nitrate content of Record Powerplus diesel fuel.

The blend which resulted from the mixing of the two fuels reportedly included 10% polypropylene oxide, which was incorrectly characterized as a lubricant (it isn’t). This must have come from the Nitrex-70, since Record Super Nitrex didn’t contain propylene oxide. The blend which resulted from the apparent mixing of equal parts of Nitrex-70 with Record Super Nitrex says that the former blend must also have included 20% propylene oxide. So where was the room for the castor oil or equivalent in Record Nitrex-70?!? This is an extremely puzzling reference! Neither Gordon Beeby nor I can find any advertising or other media references to KK Record Nitrex-70. This suggests that it was never actually marketed, instead being supplied to selected users as a fuel enhancer in return for the attendant publicity for the KK branded Record fuels. Equally puzzling is the fact that the highest proportion of nitro that can be used in a two-stroke engine fuel is a little over 60% - the essential lubricating oil fraction won’t dissolve in straight nitro, so room must be left in the mix for an additional solvent fraction which is sufficient to get the oil into solution. This would have been the actual role of the polypropylene oxide. There also has to be room in the blend for the lubricating oil.

So the KK fuel couldn’t have been 70% nitro if it was in fact a complete fuel in itself - the oil wouldn’t have dissolved. I suspect that KK Nitrex-70 was actually a fuel additive rather than a complete fuel. It may well have contained 70% nitro and 20% propylene oxide, leaving 10% for an oil fraction (a small enough fraction to dissolve in this mix). Such a fraction would have been necessary, since the combination of the Nitrex-70 with Record Super Nitrex would reduce the oil content in the mix to potentially harmful levels unless the Nitrex-70 contributed at least some oil. Mixing it at a 50/50 ratio with Record Super Nitrex would have produced exactly the nitro and propylene oxide proportions recorded in the test report. The KeilKraft fuels continued to be advertised sporadically throughout the 1960’s. The frequency of advertisements actually increased somewhat in the 1970’s, with the range now evidently stabilized at four alternative blends. These were:

The last-named fuel had evidently appeared during the late 1960’s or early 1970’s, while Record Super Nitrex and Powerplus diesel fuel had apparently been discontinued. We haven’t been able to locate any information regarding the formulation of Economy Glow fuel, but it was presumably a no-nitro brew for non-competition use. It may have been in effect an FAI fuel. Peter Chinn used Nitrex 15 in his test of the D-C Wasp which appeared in the June 1971 issue of "Aeromodeller". In his later "Engine Test Review" article on the Wasp, he stated that at that time Nitrex 15 had contained 13% 2-nitropropane, which he cited as being roughly equivalent to 10% nitromethane. It appears that alternatives to nitromethane were still being pursued, presumably for economic reasons. In the late 1970’s a wave of new commercial fuels began to appear from specialist manufacturers such as Model Technics, Irvine Glow Fuels and Helimix. At this point, advertising for KeilKraft fuels ceased. Of course, this doesn’t necessarily mean that supply did not continue - merely that the fuel was no longer advertised. Allbon/D-C and Quickstart Fuels

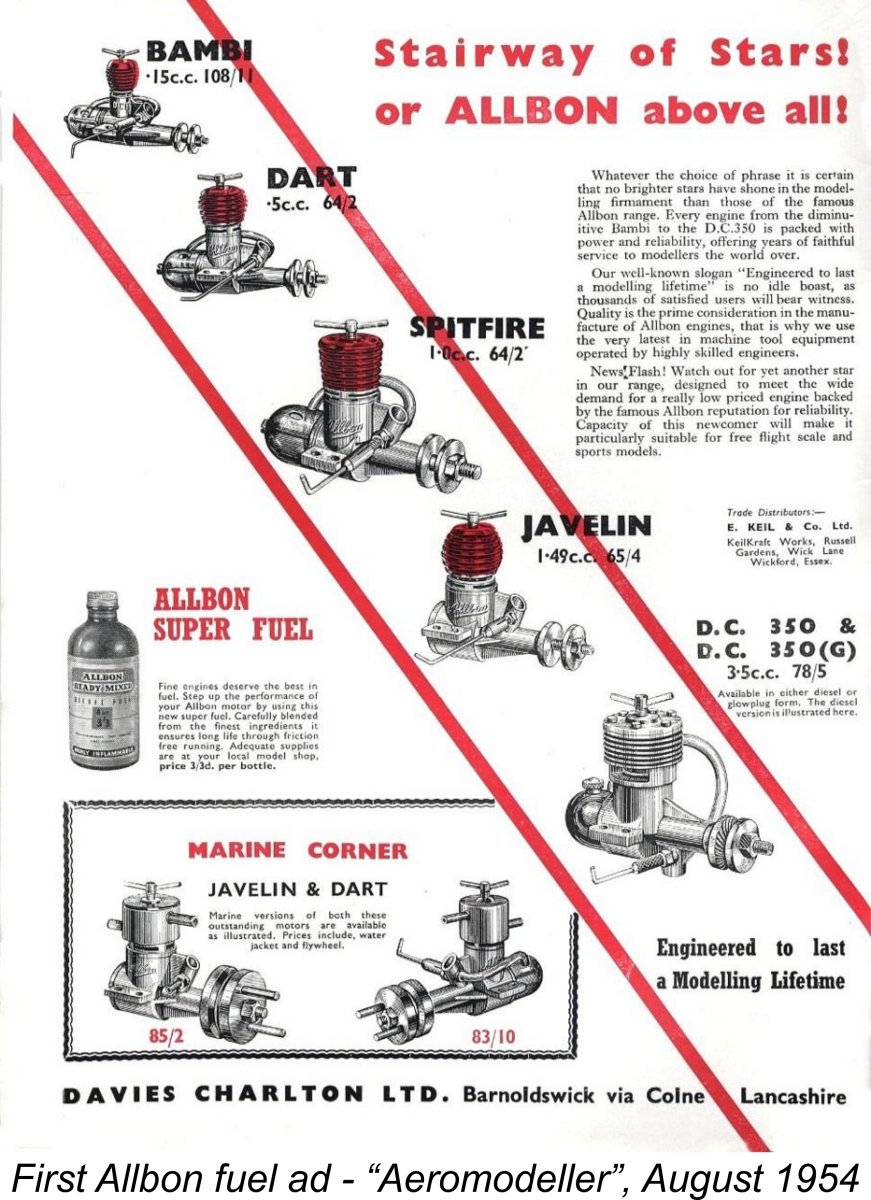

The August 1954 “Aeromodeller” test report on the Bambi stated that “the special diesel fuel marketed by Davies-Charlton proved the best, and its recommendation by the manufacturers is endorsed by our tests”. This certainly sounds like a fuel that was tailored to the requirements of the Bambi. Peter Chinn’s test of the Bambi appeared somewhat earlier in the June 1954 issue of “Model Aircraft”. It appears that the D-C fuel mentioned in the “Aeromodeller” test was not yet available, because Chinn used The first advertisements for Allbon ready-mixed diesel fuel appeared in the August 1954 and September 1954 issues of “Aeromodeller” and “Model Aircraft” respectively. From the outset, it was marketed under the overarching designation “Allbon Super Fuel”. Like other commercial British fuels at the time, it was sold in glass screw-cap bottles. No information seems to be available regarding composition beyond the notation that it was a “five part blend”. If there’s any basis to my deduction that the fuel was developed with the Bambi in mind, it likely contained a higher-than-usual ether content along with a small proportion of amyl nitrate. The blend used by Peter Chinn in his test precisely reflects this view. The fact that it was a five-part blend suggests that it used a combination of mineral and castor oils - kerosene, ether, castor oil, mineral oil, amyl nitrate. Whatever its composition, this fuel must have been highly regarded, since it seems to have become one of the standard fuels used in published diesel engine tests during the mid to late 1950's. It would have been an excellent fuel for the small diesels that were then very popular - such engines really like high ether contents.

It’s interesting to note that the fuel continued to be sold under the Allbon name even though Alan Allbon was no longer associated with D-C Ltd. I’ve discussed the possible implications of this in my separate article on the history of D-C Ltd. The fuel continued to be marketed as Allbon Ready Mixed right up to its final advertising appearance in April 1958.

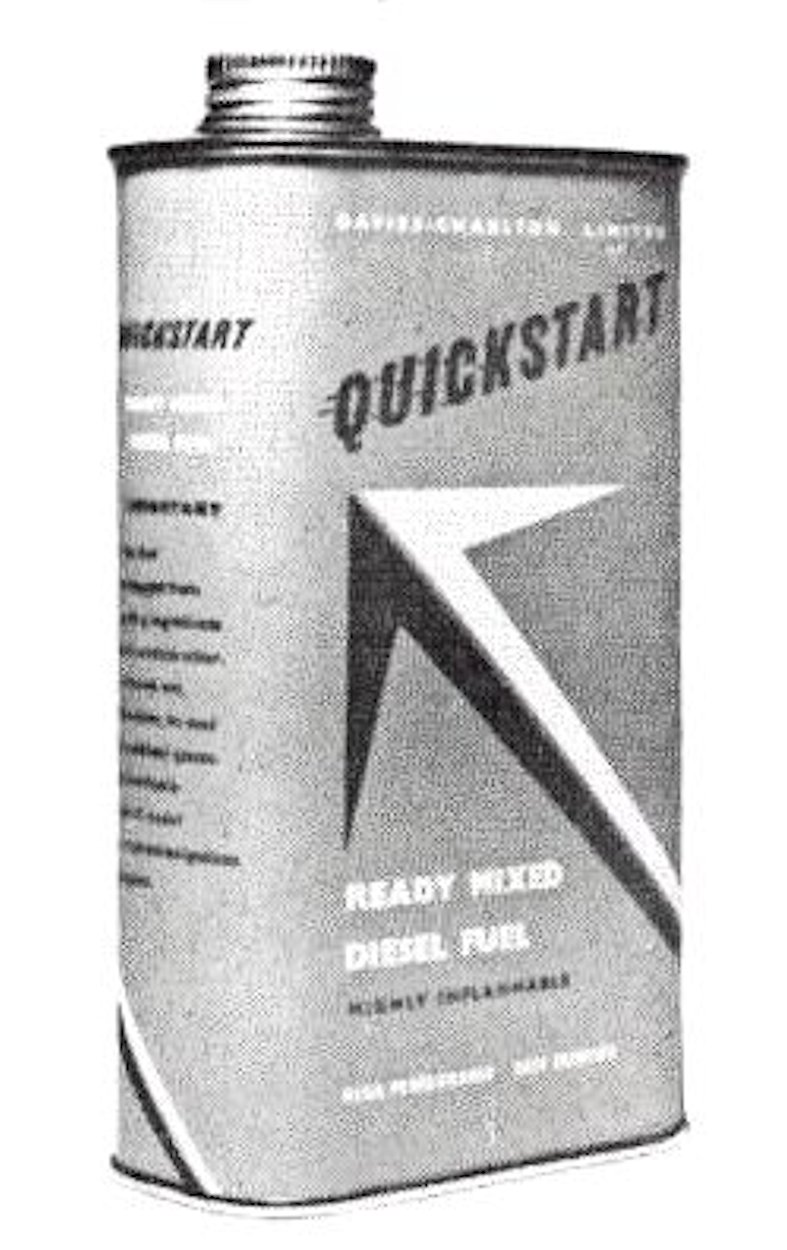

Both diesel and glow fuels were offered under the Quickstart name. A fairly detailed review of these fuels appeared in the “Over the Counter” feature of the August 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The Quickstart diesel fuel was said to be mineral oil-based and to perform in a fully satisfactory manner. The castor-based Quickstart glow fuel was described as containing 10% of a nitro-paraffin other than nitromethane, probably nitropropane in the opinion of the reviewer. The British nitromethane shortage was still biting! As of January 1961 a revised formulation of Quickstart diesel fuel was being advertised. It appears that the original mineral oil-based blend had been found wanting, because the fuel was now specifically stated to be blended with pure castor oil. The fuel was said to contain amyl nitrate, although the percentage was not specified. The Quickstart fuels continued to be featured in D-C advertising right into the 1970’s. No further changes in composition were announced during this period. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the compositions didn’t change - merely that any changes were unannounced. Miscellaneous Minor Fuel Brands The above text includes information on the major commercial suppliers of model engine fuels to the British market during the “classic” era - those which many old-timers like myself will remember. However, there were others. Some of them barely got past the initial advertising stage, while others appear to have enjoyed only short-term periods of production, probably being sold in specific geographical areas or through specific outlets. Here’s a partial listing - doubtless there were others.

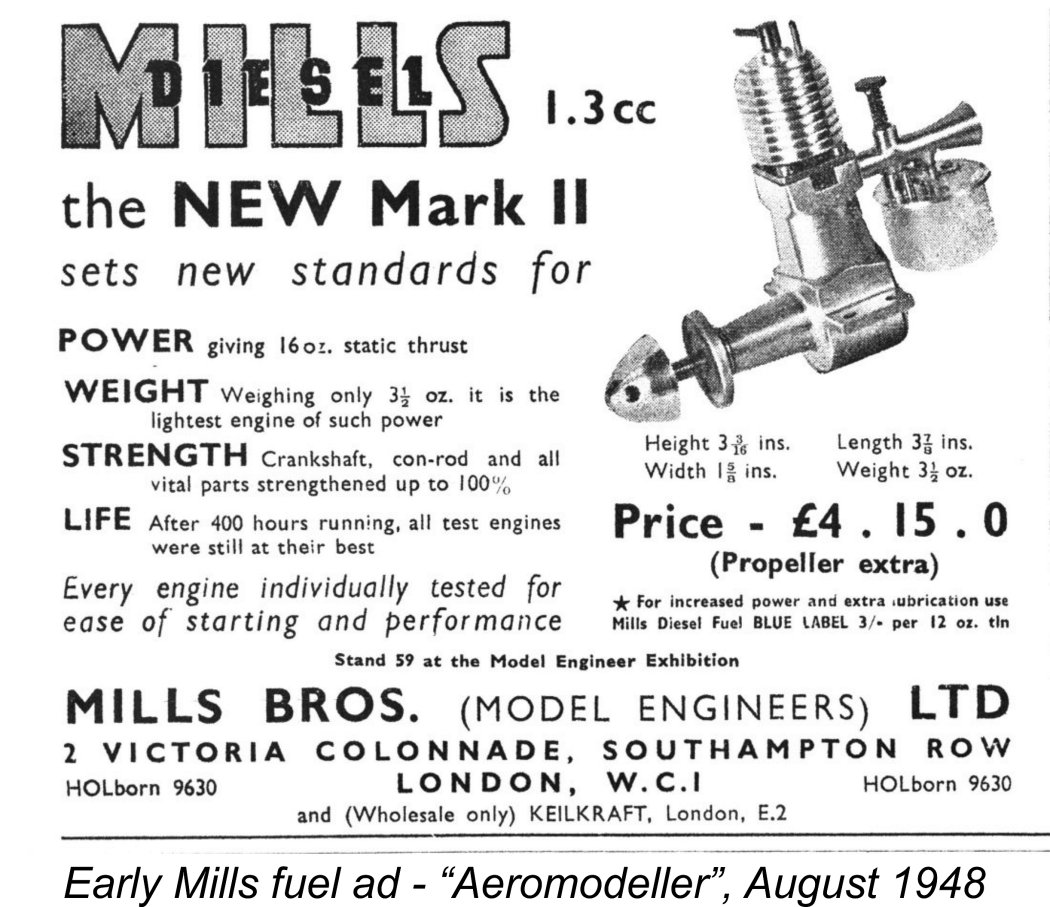

The original 1947 Mills diesel fuel was an incomplete mixture requiring the addition of ether by the customer. However, such fuels were pretty much out of fashion by 1950. Despite this, Mills Brothers continued to advertise their glass-bottled “Mills Blue Label” fuel into 1951. It appears that by this time the fuel was a complete blend containing ether, since the 1950/51 Mills Bros. advertising stated that the customer could get his originally 3 shilling (15p) bottle refilled at his local dealer for only 2s 6d (13p). This sounds to me like a ready-mixed fuel - nothing was said about any need to add ether, besides which how could one add ether to a full bottle?!? Whatever the truth regarding the ether situation, the last advertisement that I can find for this fuel appeared in the June 1951 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Caledonia Model Co. - this was a Glasgow hobby shop run by the prominent Scots modeller George Leask, who had been instrumental in founding the Scottish Aeromodellers Association in 1944, also becoming its first Chairman. This association is still going strong today.

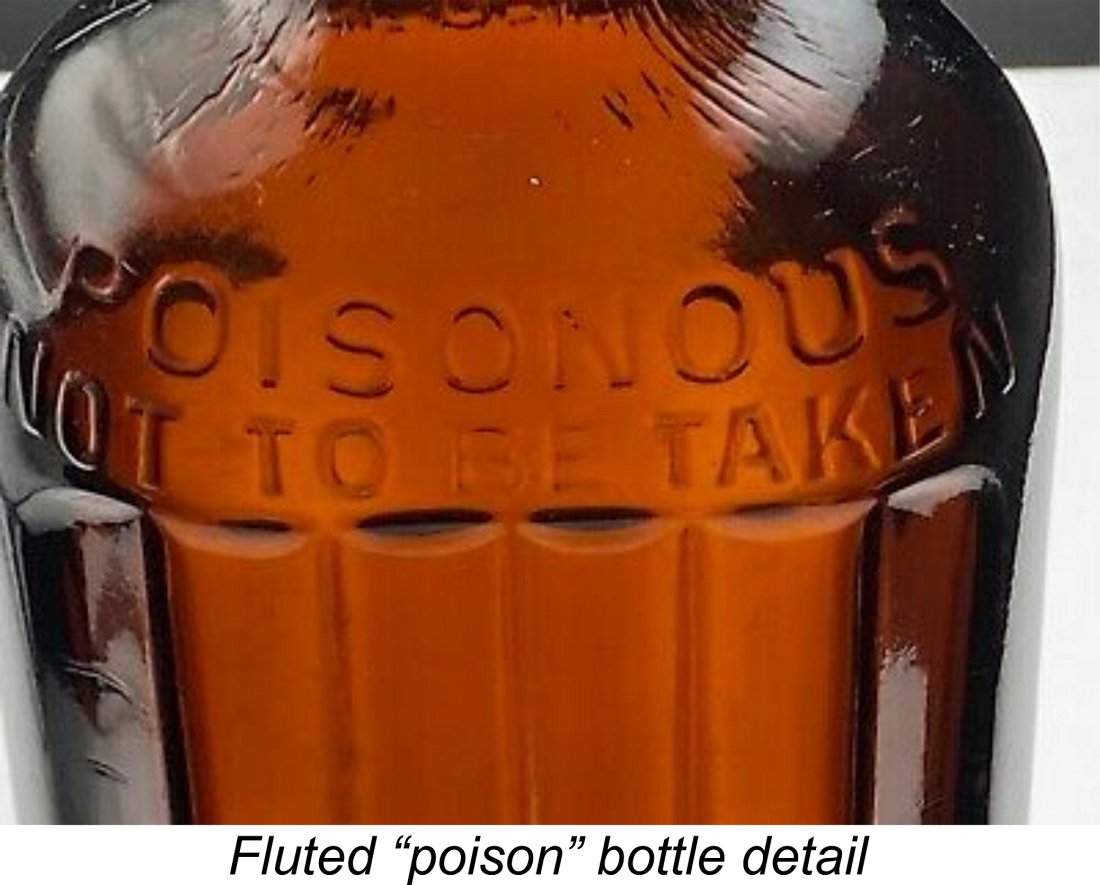

The Caley fuel was sold in fluted “poison” bottles with labels which carried a simplified one-colour “tartan” pattern. It continued to be advertised nationally into 1952 and possibly beyond, long after the Caledonian engines had gone out of production. Despite the national advertising, its market seems to have been essentially confined to its native Scotland. Even so, it remained on sale for at least 6 years, indicating that many Scottish modellers must have found it to be completely satisfactory. Roadway Models - a South London model shop located in New Malden, Surrey, very close to the E.D. factory at Kingston-on-Thames. It's interesting to note that the three advertised fuels followed the marketing pattern of the contemporary Mercury fuels very closely by assigning label colours to each fuel. The "Green Label" diesel fuel was an "add ether" blend, while the more costly "Red Label" diesel brew came ready-mixed. One suspects that the two fuels were essentially the same, the only difference being that the Red Label blend had the ether already added. The "Blue Label" glow-plug fuel was specifically stated to be blended with nitrobenzene. Given the now-recognized health issues associated with nitrobenzene, a few modellers must have paid a high price for their use of this fuel. All that can be said in the company's defence is that these health implications were very poorly understood at the time. Beginning in January 1955, a fuel identified as R-M was used in a number of "Aeromodeller" diesel engine tests during the balance of the year (sometimes in comparison with Mercury 8 and Allbon diesel fuel). Tests of the Elfin 149 BB, the Webra 1.48 Record and the Webra 0.8 Piccolo provide examples. Gordon Beeby was unable to find any contemporary advertisements for this fuel. However, it seems most unlikely that it's the RM fuel advertised in 1950 by Roadway Models. From November 1955 onwards, R-M fuel was no longer mentioned in "Aeromodeller" tests, being supplanted by Mercury RD fuel. It seems possible that tester Ron Warring was supplied in late 1954 with some pre-release Mercury RD for testing before it was named and launched onto the market under the RD banner. R-M may simply have been an abbreviation for "Racing Mercury".

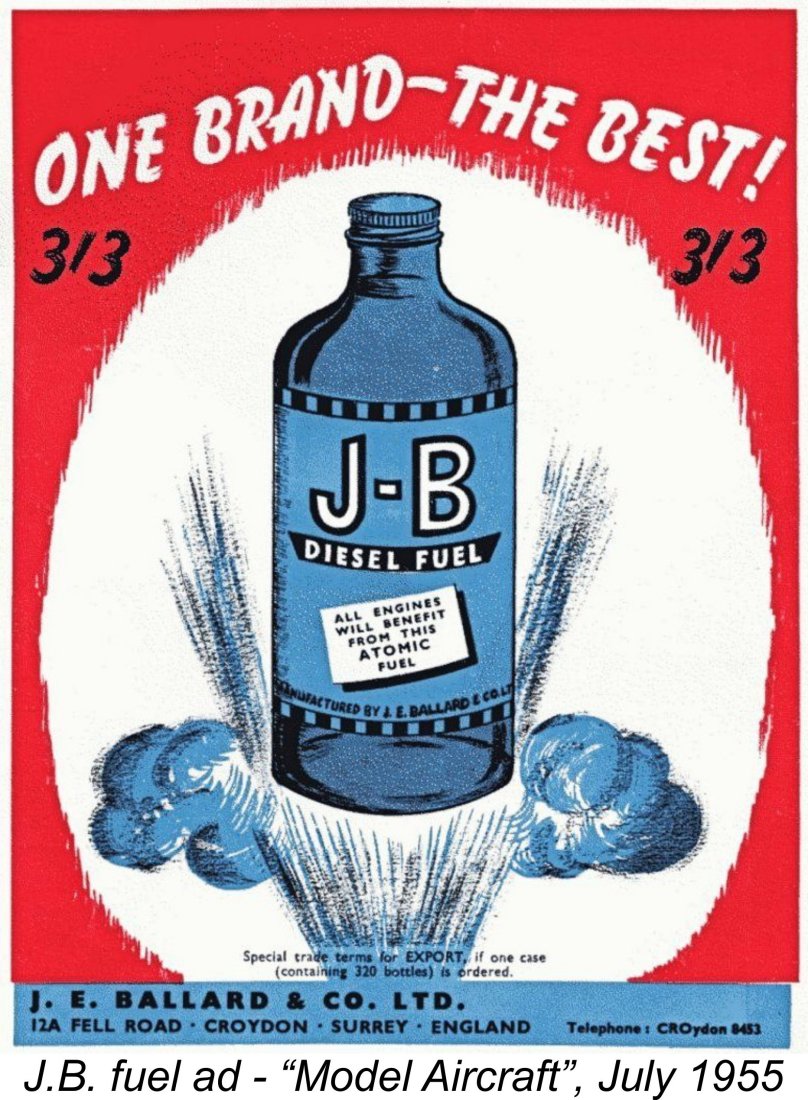

In October 1954 the release of Britfix diesel fuel was announced. A review of this new product was included in the “Trade Notes” feature of the December 1954 issue of “Aeromodeller”. The fuel was neatly packaged in a metal oil-can container complete with spout. Tests by magazine staff had shown that while the claim of improved starting was perhaps unjustified, less compression was required for running. Engine performance using this fuel was reportedly “on a par with the best”. The Britfix fuel was quite widely advertised from late 1954 through 1955, but disappeared thereafter. Presumably the contemporary competition from well-established major brands like E.D., Shell/FROG, Allbon and Mercury was too much to overcome. J-B “Atomic” fuel - the initial product of the ill-fated J-B enterprise established by former E.D. Managing It appears that when Ballard left the AMCO manufacturers to start his own J-B venture, he took the “Atomic” fuel line with him. From the start, his intention was to market a line of diesel and glow-plug engines under the J-B banner. However, a series of undefined problems delayed the release of these models. In an attempt to generate some interim cash flow, Ballard introduced the J-B “Atomic” bottled diesel fuel in mid 1955, later adding J-B “Atomic” glow fuel to the range. Both were extensively advertised throughout the regrettably short life of the company. The J-B engines finally appeared beginning in late 1955. They were fundamentally sound designs which were very attractively presented. However, they were not a success, chiefly due to some errors of judgment in the material selection which led to several unfavourable test reports. The company folded in early 1957. I’ve recounted the rather sad history of the J-B range in a separate article to be found on this website. The engines had far greater potential than their material selection allowed them to show.

Oddly enough, the Skyleada fuel never appears to have been advertised - at least, we have been unable to locate any advertisements. It would seem that its presence on the market was very brief indeed.

Yeoman - this was the trade-name used by the A.A. Hales company of Hinckley in Liecestershire in connection with the marketing of their well-known kits - anyone remember the "Dixielander", the "Scorcher" and the "Bantam Cock"? At some point in time they began to market a line of model engine fuels under the Yeoman name. As far as I'm presently aware, these Yeoman fuels were never advertised. I suspect that these brews were simply re-labelled FROG blends dating from Hales' take-over of responsibility for the FROG model engine range beginning in early 1963. Certainly, the Yeoman glow fuel continued to carry the "Red Glow Plus" designation used formerly by IMA in connection with their nitrated FROG glow fuel blend. At present, that all that I'm able to say regarding these fuels. Revmor - I'm including this one purely because it's such a great name for a model diesel fuel! This was an "add ether" blend like the early Shell and Mills fuels. I'm very grateful to Martin Dilly for drawing my attention to this aptly-named brew! The Revmor diesel fuel was marketed by the A. E. Peters hobby shop in West Wickham, a community lying between Bromley and Croydon about 12 miles SE of central London. It was sold in glass bottles having corrugations to indicate that the contents were poisonous. John Blount, a school-mate of Martin's and a future member of several British F1D teams, helped to mix the contents and fill the bottles. Apart fom the fuel, Peters also offered a couple of their own kits. They had a few small advertisements in the Model Aeronautics/Model Planes Annual series of "books" (not called "magazines" due to paper restrictions at the time) that Bill Dean and Ron Warring produced for Ian Allan in the late 1940's. Conclusion I hope that the above account has shown that British power modellers of the “classic” era (like myself) were well served by British fuel producers. Those companies appear to have worked hard to provide useful products for the use of their customers. At various times I remember using Mercury, KeilKraft, E.D, Quickstart and FROG fuels with complete satisfaction. Some were better than others with particular engines, but all worked well enough to provide plenty of enjoyable power modelling. The nitromethane supply crisis of the late 1950’s and early 1960’s posed a significant challenge for British suppliers of glow fuels which the companies concerned worked hard to overcome. A few of their remedies such as the use of nitrobenzene may have created health problems down the road for some of their customers, but they can’t be blamed for that - the general health implications and carcinogenic properties of nitrobenzene were still not fully appreciated at the time. By 1962 or thereabouts, the importation of American glow fuels from producers like Cox and K&B had commenced. In addition, the relative popularity of diesels was now in decline as the glow-plug motor continued its take-over of the market. The latter change was mainly due to the superiority of glow-plug powerplants for the R/C applications which were becoming dominant. These evolving market conditions probably explain why, although some of them hung on for a fairly long period thereafter, all of the cited “classic” British fuel manufacturers had faded away by the mid-1970's, to be replaced by specialist manufacturers such as Model Technics, Irvine Glow Fuels and Helimix. These fine companies continued the tradition of providing excellent fuels for use by the British power modelling community. _____________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published May 2022 |

| |

Over the years, a guy like me attracts a lot of questions on all kinds of topics relating to model engines of the “classic” era. One such topic is the production history and composition of the many and various model engine fuels which were commercially available in Britain during that era. People see these fuels referred to by name in published engine tests or advertisements of the period and wonder what was in them. This interest is entirely understandable, since their composition could have had a considerable influence upon the published test results.

Over the years, a guy like me attracts a lot of questions on all kinds of topics relating to model engines of the “classic” era. One such topic is the production history and composition of the many and various model engine fuels which were commercially available in Britain during that era. People see these fuels referred to by name in published engine tests or advertisements of the period and wonder what was in them. This interest is entirely understandable, since their composition could have had a considerable influence upon the published test results. Sorting all of this out is a challenging exercise, and one which I would probably never have tackled on my own. However, I had help! When I mentioned this topic to my friend and colleague Gordon Beeby of Australia, he took it upon himself to undertake a search through his extensive collection of “period” aeromodelling publications, notably “Aeromodeller” and “Model Aircraft”. He also took advantage of sources such as the

Sorting all of this out is a challenging exercise, and one which I would probably never have tackled on my own. However, I had help! When I mentioned this topic to my friend and colleague Gordon Beeby of Australia, he took it upon himself to undertake a search through his extensive collection of “period” aeromodelling publications, notably “Aeromodeller” and “Model Aircraft”. He also took advantage of sources such as the  Prior to the onset of WW2, there was no market for commercial model engine fuels in Britain. The spark ignition engines which were the only option at the time ran on white gas (straight gasoline with no additives) and mineral-based motor oil, both of which were readily and cheaply available at any garage. Everyone simply mixed their own fuel - the only variables were the brand, grade and percentage of the oil used.

Prior to the onset of WW2, there was no market for commercial model engine fuels in Britain. The spark ignition engines which were the only option at the time ran on white gas (straight gasoline with no additives) and mineral-based motor oil, both of which were readily and cheaply available at any garage. Everyone simply mixed their own fuel - the only variables were the brand, grade and percentage of the oil used. point ignition source. Nevertheless, even at this early stage some experimenters like

point ignition source. Nevertheless, even at this early stage some experimenters like  By late 1946 the development of model diesel fuels had progressed to the point where in his excellent little book “

By late 1946 the development of model diesel fuels had progressed to the point where in his excellent little book “

Nicholls didn’t overlook the developing British market for glow fuel. By 1949, Col. Bowden was able to include a comment on Mercury glow fuels in his companion book “

Nicholls didn’t overlook the developing British market for glow fuel. By 1949, Col. Bowden was able to include a comment on Mercury glow fuels in his companion book “ The issue of etherless fuels will come up again in this discussion, so I might as well deal with it here. None of the contemporary published articles or commentaries relating to diesel fuels and their constituents discussed etherless fuels. The general view seems to have been that ether was a required constituent of any effective diesel fuel.

The issue of etherless fuels will come up again in this discussion, so I might as well deal with it here. None of the contemporary published articles or commentaries relating to diesel fuels and their constituents discussed etherless fuels. The general view seems to have been that ether was a required constituent of any effective diesel fuel.

We previously saw that Mercury no. 6 was an etherless fuel, at least at the outset. In this context, a comment which appeared in the August 1954 “Aeromodeller” test report on the just-released

We previously saw that Mercury no. 6 was an etherless fuel, at least at the outset. In this context, a comment which appeared in the August 1954 “Aeromodeller” test report on the just-released

that the fuel was a straight methanol-castor blend. This seems to confirm that Mercury 45 was basically a straight fuel for general-purpose use - essentially an FAI fuel. The non-FAI competition modeller could still get Mercury no. 7 glowplug fuel containing nitromethane.

that the fuel was a straight methanol-castor blend. This seems to confirm that Mercury 45 was basically a straight fuel for general-purpose use - essentially an FAI fuel. The non-FAI competition modeller could still get Mercury no. 7 glowplug fuel containing nitromethane. I previously mentioned the Shell part-mixed fuel which had appeared in 1947 but required the addition of ether. At some point in late 1947 Shell reached an agreement with International Model Aircraft (IMA), manufacturers of the FROG range, to market Shell fuels under the FROG banner. This gave Shell the great advantage of having their fuel marketed by a well-established player in the model trade with a high level of “name” recognition, a world-wide distribution network at their disposal and an advertising program specifically focused upon the modelling community.

I previously mentioned the Shell part-mixed fuel which had appeared in 1947 but required the addition of ether. At some point in late 1947 Shell reached an agreement with International Model Aircraft (IMA), manufacturers of the FROG range, to market Shell fuels under the FROG banner. This gave Shell the great advantage of having their fuel marketed by a well-established player in the model trade with a high level of “name” recognition, a world-wide distribution network at their disposal and an advertising program specifically focused upon the modelling community. August 1949 “Aeromodeller” test of the

August 1949 “Aeromodeller” test of the

E.D. were of course one of Britain’s earliest volume manufacturers of model engines, beginning with their

E.D. were of course one of Britain’s earliest volume manufacturers of model engines, beginning with their

It seems clear from the advertising record that the E.D. company was far more focused on its model engine and radio control product lines than it was on selling fuel. Nonetheless, development of the product line did continue - by early 1955 the advertised range consisted of four blends, as follows.

It seems clear from the advertising record that the E.D. company was far more focused on its model engine and radio control product lines than it was on selling fuel. Nonetheless, development of the product line did continue - by early 1955 the advertised range consisted of four blends, as follows.

The famous firm of KeilKraft were relative latecomers to the model engine fuel supply business. They were not model engine manufacturers, being primarily involved in the model trade as kit and accessory manufacturers as well as distributors for a number of well-known firms involved in the trade. It’s perhaps an indication of the strength of the model engine fuel market that in the mid 1950’s they felt it to be worthwhile to become involved with that branch of the trade on their own account.

The famous firm of KeilKraft were relative latecomers to the model engine fuel supply business. They were not model engine manufacturers, being primarily involved in the model trade as kit and accessory manufacturers as well as distributors for a number of well-known firms involved in the trade. It’s perhaps an indication of the strength of the model engine fuel market that in the mid 1950’s they felt it to be worthwhile to become involved with that branch of the trade on their own account. It appears that the development of the Record fuel line by that name was actually an initiative by none other than the late

It appears that the development of the Record fuel line by that name was actually an initiative by none other than the late  The comment was also made that while both fuels were castor-based as regards lubrication, they both contained a proportion of mineral oil. This was intended to combat the previously-mentioned gumming tendencies which had drawn a good deal of commentary over the previous few years. From the outset, all KeilKraft fuels were sold in cans, reportedly at the suggestion of former “Model Aircraft” Managing Editor Eddie Cosh.

The comment was also made that while both fuels were castor-based as regards lubrication, they both contained a proportion of mineral oil. This was intended to combat the previously-mentioned gumming tendencies which had drawn a good deal of commentary over the previous few years. From the outset, all KeilKraft fuels were sold in cans, reportedly at the suggestion of former “Model Aircraft” Managing Editor Eddie Cosh.

Limited quantities of nitromethane did somehow remain available during this period. The test report on the

Limited quantities of nitromethane did somehow remain available during this period. The test report on the  As evidence, consider the fact that the fuel initially used in the record-breaking American

As evidence, consider the fact that the fuel initially used in the record-breaking American  Davies-Charlton (D-C) Ltd. seem to have entered the model engine fuel market at around the same time as the June 1954 release of the ground-breaking 0.16 cc Allbon Bambi diesel. It seems very likely that the development of their own blend arose from a need to provide a suitable fuel for use in the tiny Bambi developed for D-C Ltd. by

Davies-Charlton (D-C) Ltd. seem to have entered the model engine fuel market at around the same time as the June 1954 release of the ground-breaking 0.16 cc Allbon Bambi diesel. It seems very likely that the development of their own blend arose from a need to provide a suitable fuel for use in the tiny Bambi developed for D-C Ltd. by  his own blend consisting of 40% ether, 30% kerosene, 30% castor oil and 2% amyl nitrate added to the overall mix. It seems likely that the special Allbon fuel marketed by D-C Ltd. would not have departed too far from this formula - really small diesels generally require higher-than-normal ether contents.

his own blend consisting of 40% ether, 30% kerosene, 30% castor oil and 2% amyl nitrate added to the overall mix. It seems likely that the special Allbon fuel marketed by D-C Ltd. would not have departed too far from this formula - really small diesels generally require higher-than-normal ether contents.

In 1959 D-C Ltd. commenced a fairly comprehensive re-branding of their products using the “Quickstart” trade-name. Among other products, they released a re-designated line of model engine fuels under the Quickstart label. The first advertisement for these fuels appeared in the October 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller”, while their appearance drew commentary in the “Over the Counter” feature of the April 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”.

In 1959 D-C Ltd. commenced a fairly comprehensive re-branding of their products using the “Quickstart” trade-name. Among other products, they released a re-designated line of model engine fuels under the Quickstart label. The first advertisement for these fuels appeared in the October 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller”, while their appearance drew commentary in the “Over the Counter” feature of the April 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”.  Mills Brothers - this famous company is of course best known for its iconic series of model diesel engines. However, as we saw right at the start of this article, the company was also one of the first to offer model diesel fuel on a commercial basis. Their Mills “Blue Label” fuel was first offered in 1947 and was nationally advertised from mid 1948 onwards. It was evidently tailored for use in the sideport diesels manufactured by Mills Bros., hence probably containing little or no amyl nitrate.

Mills Brothers - this famous company is of course best known for its iconic series of model diesel engines. However, as we saw right at the start of this article, the company was also one of the first to offer model diesel fuel on a commercial basis. Their Mills “Blue Label” fuel was first offered in 1947 and was nationally advertised from mid 1948 onwards. It was evidently tailored for use in the sideport diesels manufactured by Mills Bros., hence probably containing little or no amyl nitrate.

In 1950 Roadway Models advertised a line of fuels under the RM brand-name, presumably derived from their own initials.

In 1950 Roadway Models advertised a line of fuels under the RM brand-name, presumably derived from their own initials.  Britfix - a company which was very familiar to British modellers in the 1950’s for the range of quality adhesives that they offered - I used them myself. The name remains alive today, albeit now under the ownership of Humbrol.

Britfix - a company which was very familiar to British modellers in the 1950’s for the range of quality adhesives that they offered - I used them myself. The name remains alive today, albeit now under the ownership of Humbrol.

Skyleada - this was an old-established company best known for its model aircraft kits. In early 1958 it released its "Spitfire" Diesel Fuel completely without fanfare. This product was reviewed in the “Over the Counter” feature of the July 1958 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Based upon a three-month period of use, the reviewer formed the opinion that it was a castor-based blend with a modest amyl nitrate content. It evidently didn’t offer any startling performance increase over other well-known brands, also requiring a slightly higher compression setting than with other more heavily nitrated fuels. However, it definitely outperformed un-nitrated mixtures.

Skyleada - this was an old-established company best known for its model aircraft kits. In early 1958 it released its "Spitfire" Diesel Fuel completely without fanfare. This product was reviewed in the “Over the Counter” feature of the July 1958 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Based upon a three-month period of use, the reviewer formed the opinion that it was a castor-based blend with a modest amyl nitrate content. It evidently didn’t offer any startling performance increase over other well-known brands, also requiring a slightly higher compression setting than with other more heavily nitrated fuels. However, it definitely outperformed un-nitrated mixtures.

Oddly enough after such a high-profile advertising introduction, this proved to be the one and only advertisement for the Veron range of fuels! Either production problems reared their ugly heads or the line was bought out pre-emptively by another company - we don’t know.

Oddly enough after such a high-profile advertising introduction, this proved to be the one and only advertisement for the Veron range of fuels! Either production problems reared their ugly heads or the line was bought out pre-emptively by another company - we don’t know.