|

|

The Banshee .604 Racing Engine

Now for many years I’d been the frustrated owner of an original box for one of these engines. I can’t even recall how I came by it at this point! The box even retained the instruction leaflet, spare parts list and sundry other paperwork - but sadly no engine, hence my frustration! This documentary evidence was clearly insufficient to serve as the basis for an article on the Banshee, leading me to expect that I would never be able to write such an article given the extreme rarity of the actual engine. However, in late 2022 while idly trolling through the model engine listings on eBay, as I occasionally do, I stumbled quite fortuitously across a listing for one of these engines - the first such listing that I’d ever seen in years of looking! The unit on offer was in very fine as-new condition cosmetically, but the seller stated quite openly that the engine had very poor compression and would require a re-bore prior to any attempt being made to put it into operation. This unfavourable description didn’t bother me at all - I knew people who could fix problems of this kind, besides which I realised that this might be my one and only opportunity to obtain an actual engine to occupy my long-vacant box! Not only that, but I reasoned that the rather discouraging description might well keep the selling price within reasonable limits. So I went ahead and joined the on-line fray.............

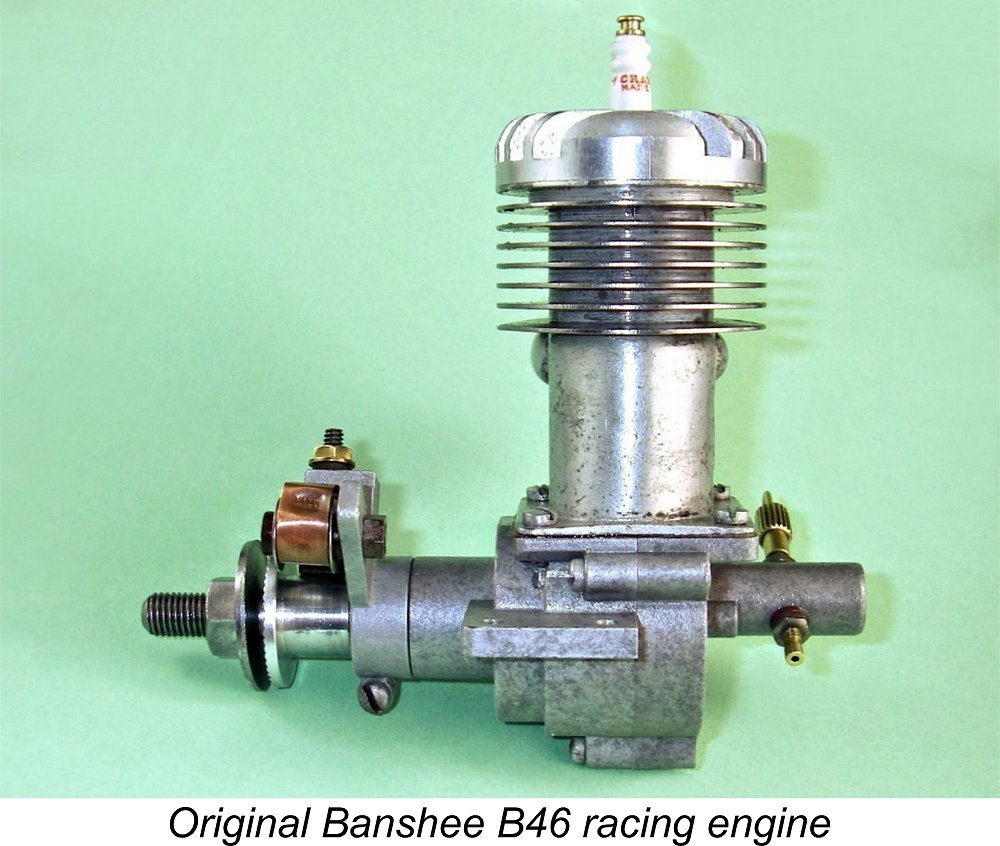

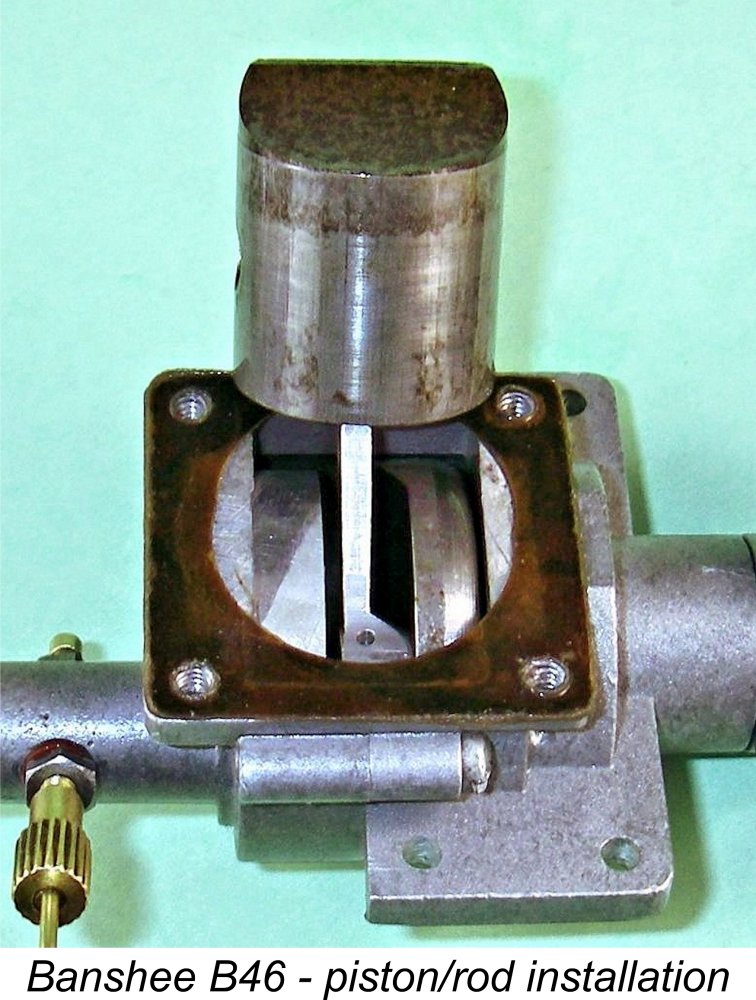

When the engine arrived, it proved to be an example of the B46 variant of the Banshee (see below). It turned out that the seller had been scrupulously honest in his description. The engine was indeed in superb original condition, seemingly unrun and certainly unmounted. However, the piston was significantly undersized for the bore. There was some compression, but probably not enough to run the engine. Someone with more enthusiasm than knowledge had clearly been messing with this example in the past, because the cylinder was installed with the exhaust stack on the left despite the fact that the piston baffle was also on the left, positioning it on the exhaust side instead of on the transfer side where it should be. The head had been oriented to accommodate the incorrectly-positioned piston baffle so that the engine would still turn over. However, the cylinder base gasket had not been re-oriented, causing it to completely block the bypass entry as assembled! Oops .....................I reassembled the components in the correct orientation. It was obvious that the loose-fitting piston had not resulted from operational wear, since its condition was consistent with its being unrun, like the rest of the engine. Someone had evidently taken the original piston from this engine to fit into another example, simply substituting the piston from the other engine and then throwing this example back together with minimal attention being paid to correct assembly. There's a story there, but I'll never know it ............... Regardless, the engine is a fine complete example of this very rare design, and my long-vacant box has finally acquired an occupant! If I ever wanted to run the engine I'd have to make (or have made) a better-fitting piston. For now, this acquisition has placed me in a position to provide an authoritative first-hand description of the Banshee. But before getting into that, let’s have a look at the production history of this very distinctive engine. Production History

This much appears to have been quite widely known among aficionados of Canadian model engines. However, for a fact-hound like me, the devil’s in the details! In that regard, I was once again assisted immeasurably by Sheldon Jones, who is the son-in-law of my good mate Tim Dannels. Sheldon is an expert at tracking down obscure genealogical information, having assisted me previously in this capacity. He was able to dig up a good deal of information on George Molson Barrett.

London was then a modest-sized town of some 50,000 residents lying some 200 km (120 miles) south-west of Toronto in the direction of Detroit, Michigan. It has since grown to a population of well over 400,000 inhabitants. George seemingly remained in London right through to the WW2 years and beyond. When WW2 broke out in September 1939 as far as Canada was concerned, he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), which doubtless reflects his evident interest in model aviation. At some point he became a qualified engineer, achieving certification both as a Registered Professional Engineer (P.E.) and a Certified Manufacturing Engineer (C.Mfg.E.). He was thus extremely well qualified to design and build the Banshee racing engine.

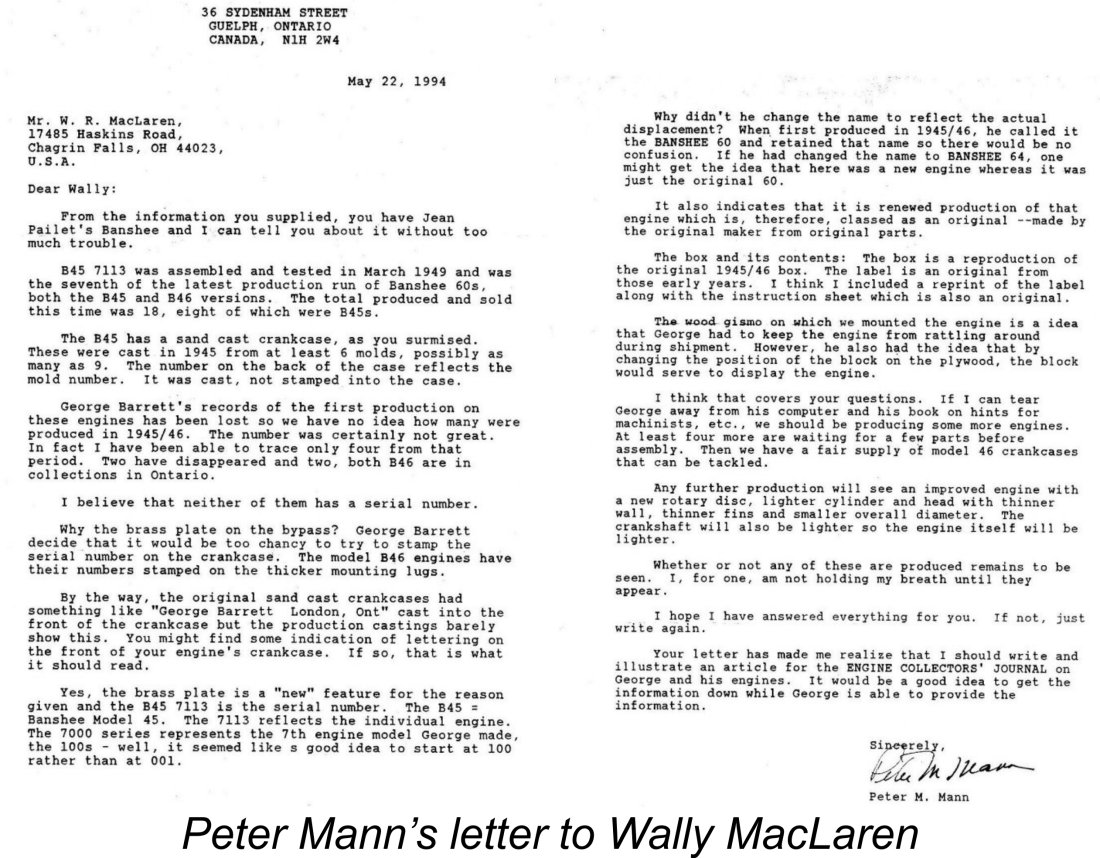

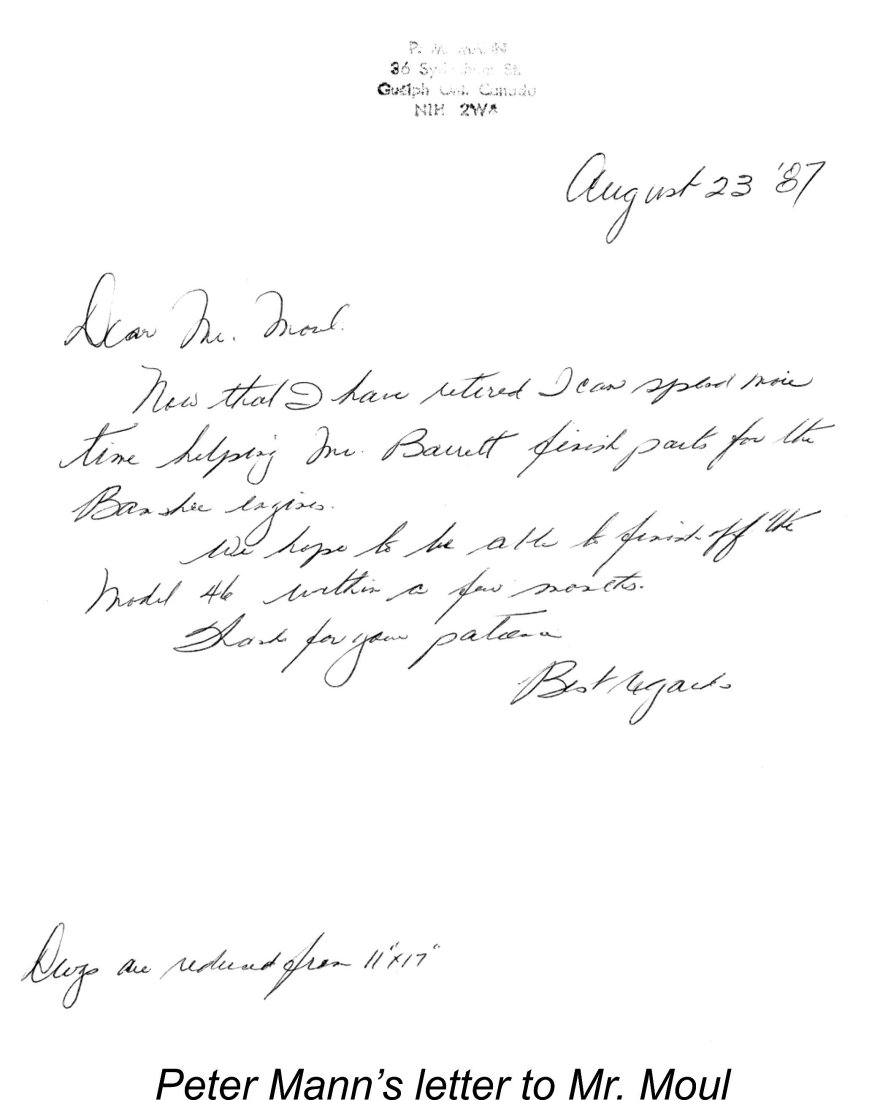

Peter Mann was a close friend and colleague of George Barrett, having assisted him in the reproduction of the Banshee 60 Model 46 during the 1980’s (see below). The letter is extremely informative in providing some clarification regarding a number of matters associated with the Banshee’s production. For one thing, it confirms that production of the original engines did indeed begin in 1945. Although the engine's true displacement calculated from its cited (and checked) bore and stroke of 0.950 in. (24.13 mm) and 0.900 in. (22.86 mm) respectively was 10.45 cc (0.638 cuin.), making it a 64 in reality, the displacement always quoted by the maker was .604 cuin. Evidently Wally MacLaren had queried this clear inconsistency, receiving a somewhat vague response from Peter Mann, who suggested that it was to avoid some form of confusion among prospective buyers of the engine. There were actually two distinct variants of the Banshee. For his own record-keeping purposes, George Barrett referred to these as the B45 and B46 models - the numbers presumably refer to the year of the variant’s introduction. The original B45 examples from 1945 used sand-cast crankcases which were produced from at least 6 different patterns - possibly as many as 9. The mounting lugs of this model were relatively thin - the later B46 model used castings produced from permanent molds which featured significantly thicker lugs as well as a few other detail changes.

It appears that production of both variants continued somewhat sporadically through to 1949. At some point along the way Barrett began to assign serial numbers to the engines. Wally Maclaren’s example which had prompted his inquiry to Peter Mann bore the serial number B45 7113, which appeared on a brass plate fixed onto the bypass. Peter stated that the brass plate was used on the B45 units because George Barrett lacked confidence in the ability of the lightly-constructed B45 cases to withstand the stresses of having serial numbers stamped on them without distorting. The more heavily-constructed B46 models during this period had their numbers more conventionally stamped on their very substantial mounting lugs. Peter was able to shed some light on the serial numbering system applied to these engines. The B45 (or B46) naturally referred to the variant in question. The 7 which started the actual number apparently reflected the fact that this was the 7th model engine design which George Barrett had originated, speaking to his considerable experience in engine-building prior to embarking upon the Banshee project. Presumably the Banshee was the first such design which he viewed as warranting series production. The last three digits are the actual serial number. The latter sequence was started at 100, making Wally’s engine the 13th example of the B45 model which had been completed since the application of serial numbers began. It was Peter’s understanding that this particular example was part of a batch of some 18 engines which were assembled in 1949. Of these, 8 were apparently B45 models, the balance being B46 examples. These figures amply underscore the Banshee’s present-day rarity! It seems highly unlikely that the total number produced exceeded 50 units of both models together. Wally’s engine had originally been sold to one Jean Pailet. It also seems unlikely that production of the original Banshee at any level continued past 1949. George Barrett remained very active in the engineering field, taking out a surprising number of patents during subsequent years. Among many other things, he seems to have spent a good deal of time working on improved versions of a hydraulic motor which he had developed. However, the story doesn’t end in 1949 by any means! The Banshee has another noteworthy claim upon our interest - it was the subject of a "collector's re-issue" by its original manufacturer, over 40 years after its original release! The only other manufacturer to produce a comparably retrospective model was the O.S. company of Osaka, Japan, which issued a limited edition near-replica of its own 1940 Type 6 sparkie in 1986 as a commemorative release to mark the company’s first 50 years in the model engine business. A review of the superb O.S. K6 replica appears elsewhere on this website.

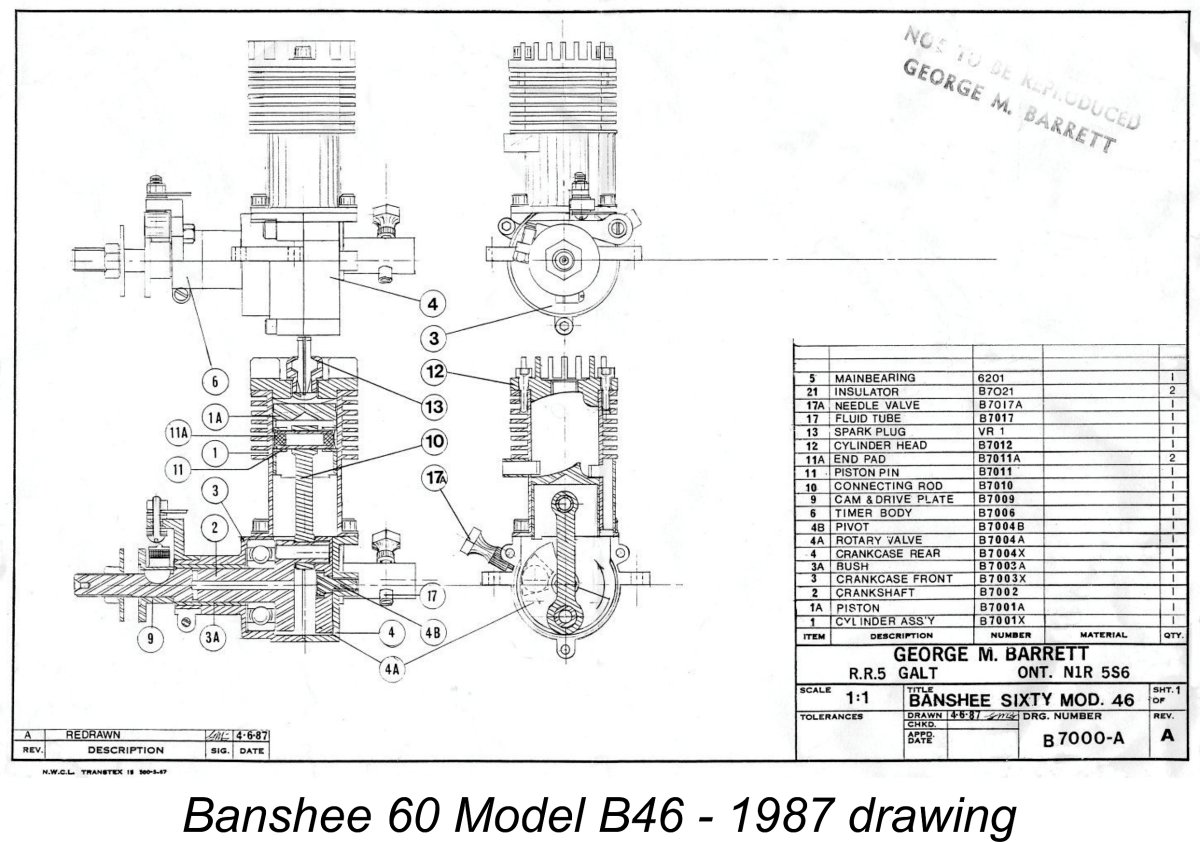

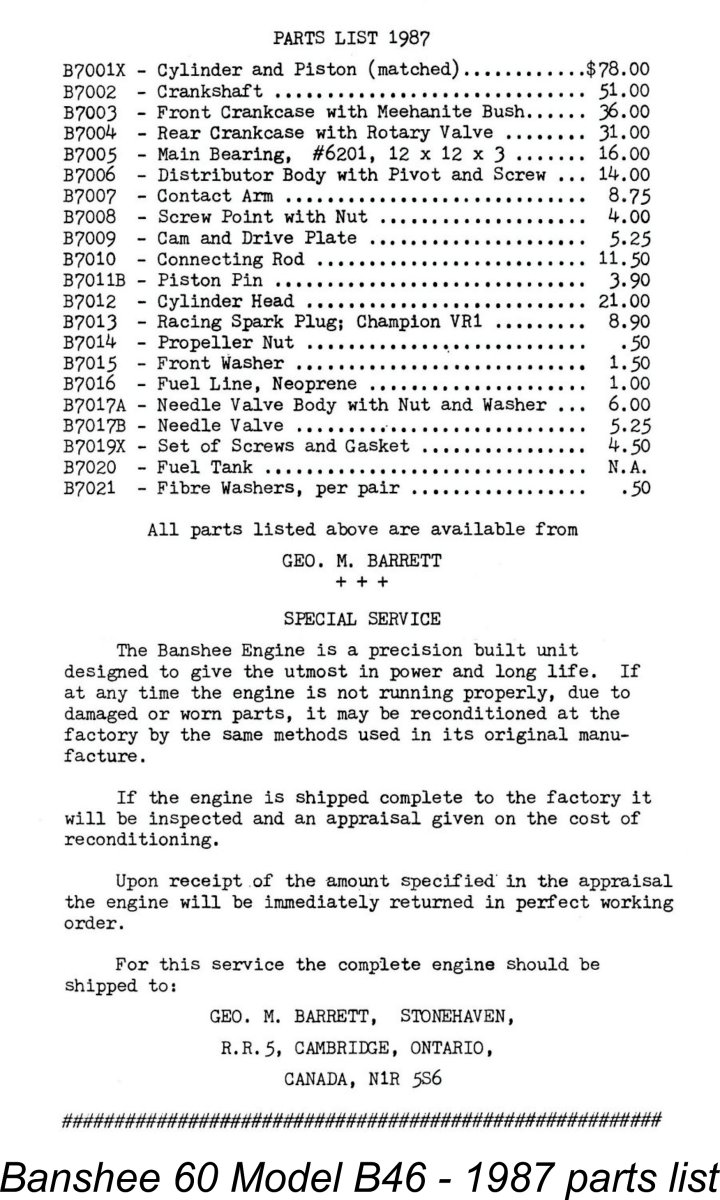

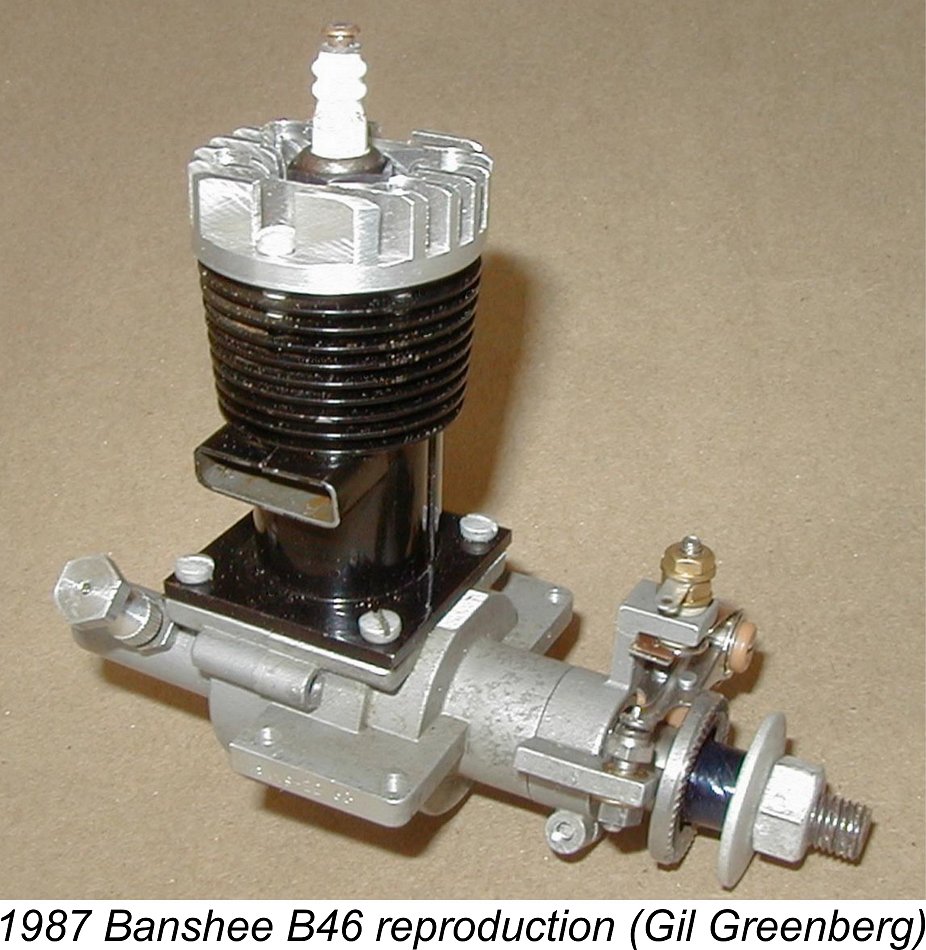

The Banshee Sixty Model 46 actually represented a resumption of production of the B46 model rather than the creation of a “replica”, since the original manufacturer remained responsible and the same design was followed. Moreover, many original parts left over from the original production sequence of the 1940’s were used in its construction, along with some newly- The reproduction concept appears to have been instigated in the first half of 1987 - the attached general arrangement drawing which was prepared and signed by Barrett personally is dated June 6th, 1987. This drawing was part of the contents of the box in which my example of the original Banshee is now housed. Barrett also produced an updated 1987 spare parts list for the Banshee, as reproduced at the right. My box also contained a copy of a letter dated August 23rd, 1987 from Peter Mann to a certain Mr. Moul. It appears that Moul had ordered an example of the Banshee reproduction and was becoming concerned over the delay in receiving his engine. George Barrett (who was 66 years old by this time) had evidently been having some difficulty in completing the planned run of these units.

I have no information regarding whether or not the delivery schedule suggested by Peter Mann was actually met, nor can I report on the number of such units completed. All that I can say is that a few examples definitely did reach buyers - Gil Greenberg, Darrell Peugh and Paul Knapp all owned examples, and there must surely have been more. However, the number cannot have been large - examples are very rarely encountered today. According to Peter Mann, George Barrett was still very much on deck as of May 1994, spending a great deal of time at his computer working on a book containing hints to machinists, among other topics. The production of further examples of the Banshee was still contemplated at that time - evidently some B46 cases remained unused. However, Peter expressed doubts that these engines would ever materialize, and George Barrett settled the matter quite decisively by passing away on December 8th, 1995 in Toronto at the age of 76. That’s about all that I’ve been able to learn about the production history of the Banshee. It’s time now to proceed to a description of the engine itself. The following comments are necessarily based for the most part upon an examination of my own engine, supplemented by such information as can be derived from an inspection of available images of other examples. Description

Beginning as usual with the tale of the tape, the bore and stroke of the Banshee were 0.950 in. (24.13 mm) and 0.900 in. (22.86 mm) respectively for a displacement of 10.45 cc (0.638 cuin.). At the time of the engine’s production, powerplants of up to 0.649 cuin. (10.64 cc) were permitted in many big-bore competition classes in North America. The designer clearly took full advantage of this, although oddly enough he always cited the incorrect displacement of .604 cuin. on both the box label and the instruction sheet despite giving the bore and stroke dimensions correctly. The engine weighed in at a checked 441 gm (15.56 ounces) complete with plug - a fairly typical figure for a classic racing engine of this displacement.

At first sight this feature might appear a little odd for a racing engine, but in reality there was sound reasoning behind it. The fact was recognized quite early on that the contribution of front ball-races to classic model engine performance was relatively small, since they were located at the more lightly-loaded end of the shaft (assuming that the prop was well balanced). The major exception to this principle would be in the case of engines intended for car or hydroplane service, where the weight of the flywheel and/or the reactive forces generated by gearing may impose a significant lateral loading on the front of the shaft. Gyroscopic precession may also develop substantial lateral loads in engines used in tethered applications.

In fact, the contribution of the front race has the potential to be negative unless great care is taken during construction. The two bearings have to be in perfect alignment in order to work together efficiently. The noted English diesel engine designer "Gig" Eifflaender of P.A.W. fame used to quip that a single ball-race engine might be 10% faster than its plain bearing equivalent, but a twin ball-race version of the same engine could be up to 3% slower! For many years Eifflaender practised what he preached by sticking with single ball-race shafts in his iconic P.A.W. diesels.

The precision of the die-castings on the B46 model is remarkable - the joint between the two castings is barely perceptible, although it is visible in the side view at the left as well as the right-side view presented earlier. There's no visible evidence of a gasket, leading one to suspect that the joint is sealed by metal-to-metal contact, perhaps with some kind of sealant. It was my uncertainty regarding this point that greatly contributed to my reluctance to disturb the engine beyond the previously-mentioned re-orientation of the cylinder and head. Speaking of which, the light alloy head appears to have been machined from barstock, in defiance of the instruction leaflet's claim that it was a casting. Perhaps some were ..........regardless, the head is nicely formed internally to accommodate the piston crown contours, also being centrally drilled and tapped to accommodate a 3/8-24 spark plug. The head is secured to the cylinder with six slot-head machine screws. Once again, there's no sign of a gasket, making it appear likely that reliance was placed upon a metal-to-metal joint. This is consistent with the leaflet's comment that it was lapped to fit the cylinder.

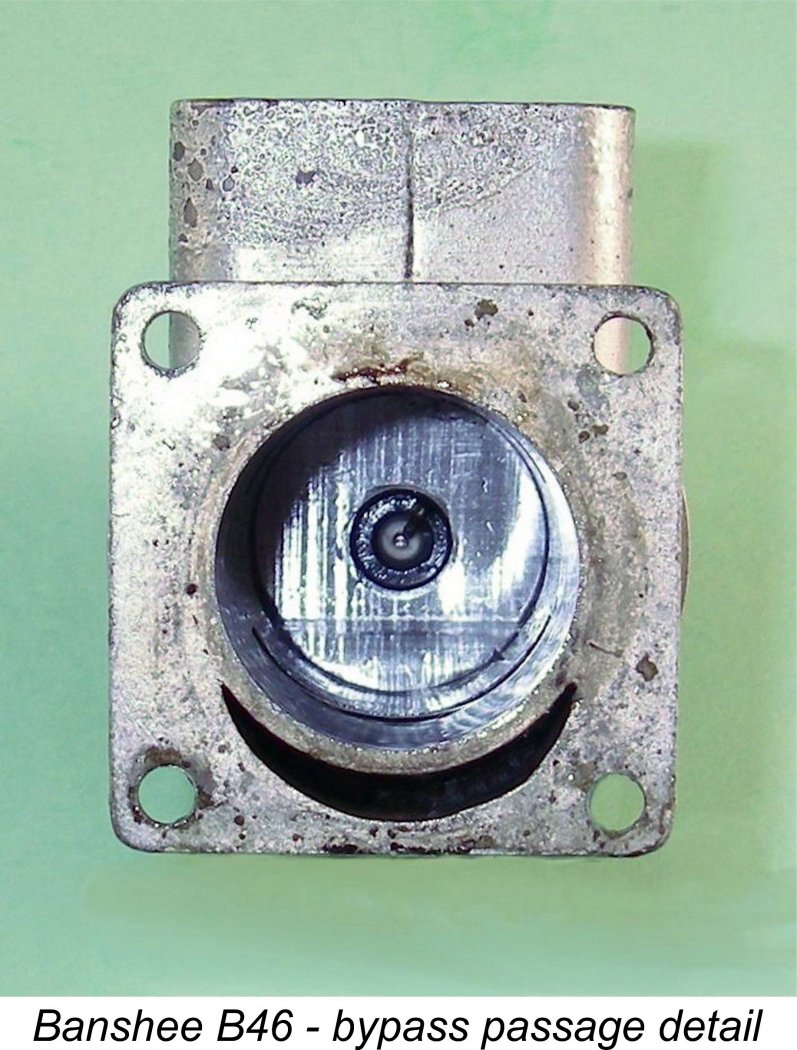

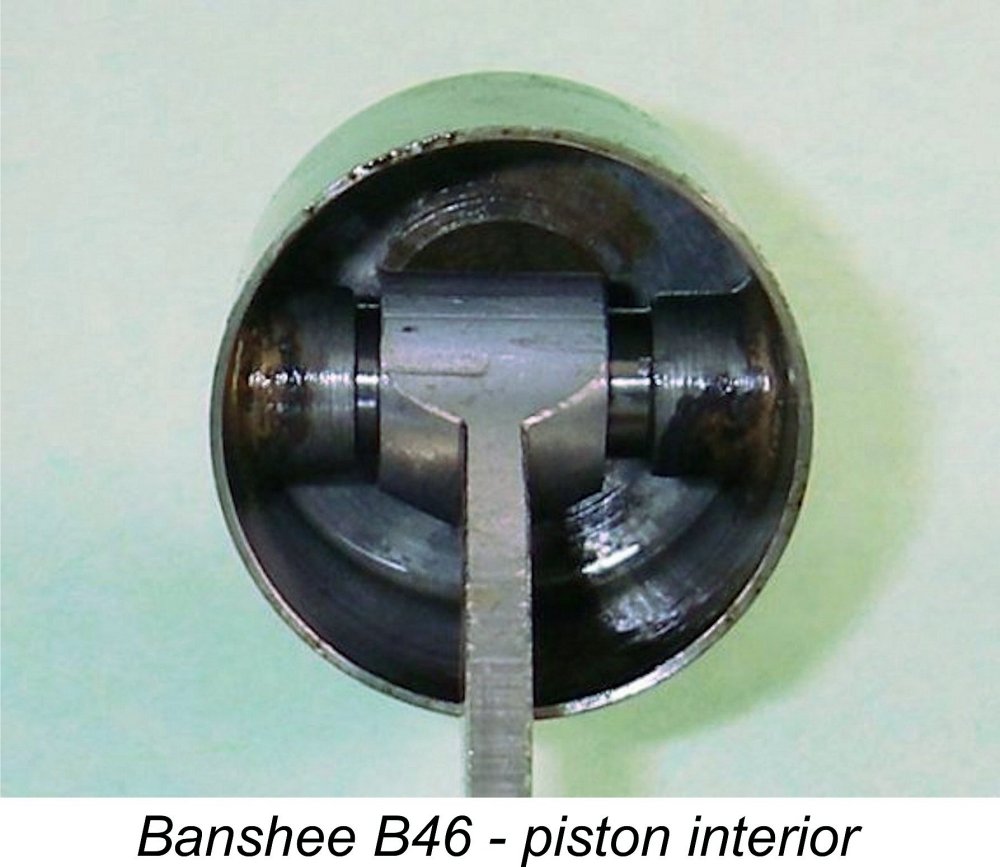

The bypass passage created through the brazing-on of the sheet metal outer wall is relatively modest in area. I would actually expect this to be the limiting design feature in all-out performance terms. That said, it would contribute to relatively high transfer gas velocities. Perhaps it was this The piston is a composite component made from steel. It has extremely thin walls - a good measure for lightness. The very substantial bosses are brazed into the working shell. A tubular steel gudgeon (wrist) pin is The piston drives the crankshaft through a conrod which is machined from an aluminium alloy forging. Although seemingly rather skinny for a racing engine of this displacement, the fact that the conrod is a forging should enhance its strength somewhat. Moreover, reciprocating weight appears to have been relatively low.

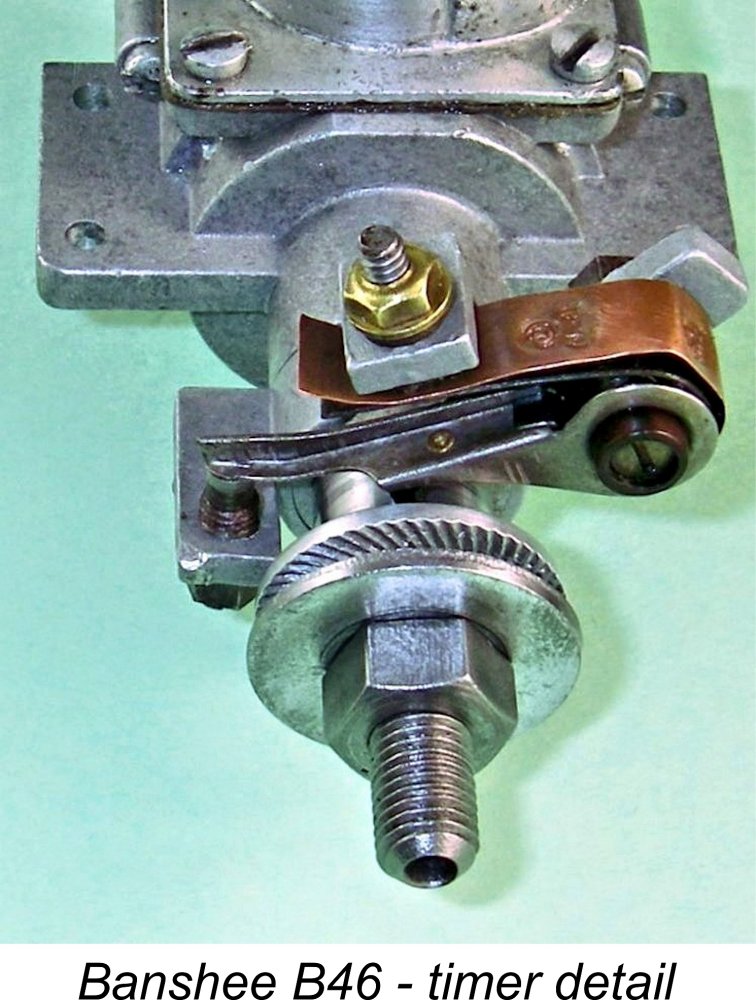

The timer is a very well-made component of the automotive type which had become more or less standard on racing engines of the period. It is activated by a cam formed at the rear of the steel prop driver, which is locked to the shaft using a Woodruff key. A check of my illustrated example using a continuity tester proved that it was operating perfectly, with a dwell period (points closed) of around 70 degrees - probably adequate albeit rather short by later racing engine standards. The prop is secured with a conventional nut-and-washer combination.

That's about as far as I can go in describing this engine. There are undoubtedly a number of minor variations, as we might expect with a low-production custom-built engine like this one. Several different head profiles are encountered, while the exhaust stacks vary between round-ended (like my engine) or rectangular. In addition, the needle valve alignment differs between examples. Some are mounted vertically, while others (like mine) are set at an angle to the right. However, the basic design appears to have remained quite consistent apart from the use of two distinct crankcase castings, as mentioned earlier. Summary and conclusion

Barrett refrained from making any specific performance claim, not even providing any airscrew recommendations. He confined himself to the statement that the engine had a practical speed range of 3,000 to 15,000 rpm. Why anyone would contemplate running this engine at anywhere near the lower figure has me beat! Still, the Banshee stands as a testimonial to the skill and enthusiasm of its creator George Barrett. It would have represented real competition to its contemporary Canadian-made rival, the Monarch 600 from not-so-distant Scarborough, just the other side of Toronto. The beautifully-made FRV Queen Bee 60 racing unit might have given both of them some serious domestic competition, but that engine never got beyond the prototype stage. As it is, the Toronto-area makers of the Banshee and Monarch models gave Canada a classic racing engine heritage of which she can be proud. Full marks to George Barrett for bringing his very individualistic design to fruition! I hope that you've enjoyed becoming acquainted with George and the fine engine that he created! ___________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published March 2023

|

| |

In an article which appeared on this website in February 2018, I wrote about the 10 cc

In an article which appeared on this website in February 2018, I wrote about the 10 cc  A fair number of my fellow enthusiasts bid on the engine, but no-one was willing to go to the wall for this one despite its rarity. I ended up winning the auction with a bid of US$257, which I considered to be a not unreasonable price to pay for an engine of this rarity, especially given the fact that I already had the original box and papers to go with it!

A fair number of my fellow enthusiasts bid on the engine, but no-one was willing to go to the wall for this one despite its rarity. I ended up winning the auction with a bid of US$257, which I considered to be a not unreasonable price to pay for an engine of this rarity, especially given the fact that I already had the original box and papers to go with it! The Banshee .604 spark ignition racing engine is yet another almost-forgotten product of the Canadian model engine manufacturing industry, such as it was. This disc rear rotary valve (RRV) unit was first made in 1945 in very small quantities by George Molson Barrett, trading as Barrett Engines of London, Ontario. The engines were distributed by Modelcraft Hobbies Ltd. of Toronto. Production of the original model appears to have continued somewhat sporadically until 1949.

The Banshee .604 spark ignition racing engine is yet another almost-forgotten product of the Canadian model engine manufacturing industry, such as it was. This disc rear rotary valve (RRV) unit was first made in 1945 in very small quantities by George Molson Barrett, trading as Barrett Engines of London, Ontario. The engines were distributed by Modelcraft Hobbies Ltd. of Toronto. Production of the original model appears to have continued somewhat sporadically until 1949. George M. Barrett was born on November 30

George M. Barrett was born on November 30 Tim Dannels was kind enough to share the contents of his own Banshee files with me to assist in the preparation of this article. Among the material preserved in Tim’s files was a letter dated May 22

Tim Dannels was kind enough to share the contents of his own Banshee files with me to assist in the preparation of this article. Among the material preserved in Tim’s files was a letter dated May 22 Unfortunately, George Barrett’s records for the original production of these engines had been lost by 1994 - all that Peter Mann was able to say was that the number produced was not large. As of his time of writing, he had been able to trace only four surviving units from that early period. Two of these had subsequently vanished from sight, while the other two resided in collections in Ontario. The latter two examples were B46 units, neither of which displayed a serial number. My own recently-acquired example is a early B46 model which also doesn't bear a serial number. Given the passage of almost 30 years, it's entirely possible that my engine is one of the un-numbered examples identified by Peter Mann.

Unfortunately, George Barrett’s records for the original production of these engines had been lost by 1994 - all that Peter Mann was able to say was that the number produced was not large. As of his time of writing, he had been able to trace only four surviving units from that early period. Two of these had subsequently vanished from sight, while the other two resided in collections in Ontario. The latter two examples were B46 units, neither of which displayed a serial number. My own recently-acquired example is a early B46 model which also doesn't bear a serial number. Given the passage of almost 30 years, it's entirely possible that my engine is one of the un-numbered examples identified by Peter Mann.  The Banshee reproduction was designated as the Banshee Sixty Model 46 by George Barrett, who had relocated to Cambridge, Ontario by this time. Thanks to the efforts of Sheldon Jones, I was able to make contact with George Barrett's niece Wendy Willard, who clarified the circumstances surrounding this relocation. Apparently it dated all the way back to 1948 or thereabouts, when George's parents bought the Cambridge property. There were two houses on the property - the smaller original house and a subsequently-added larger residence. A separate mechanical workshop was also located on the property. George's parents lived in the big house, while George and his family occupied the smaller house. The workshop became George's domain.

The Banshee reproduction was designated as the Banshee Sixty Model 46 by George Barrett, who had relocated to Cambridge, Ontario by this time. Thanks to the efforts of Sheldon Jones, I was able to make contact with George Barrett's niece Wendy Willard, who clarified the circumstances surrounding this relocation. Apparently it dated all the way back to 1948 or thereabouts, when George's parents bought the Cambridge property. There were two houses on the property - the smaller original house and a subsequently-added larger residence. A separate mechanical workshop was also located on the property. George's parents lived in the big house, while George and his family occupied the smaller house. The workshop became George's domain. manufactured components. In particular, it seems that the reproduction engines were based upon original B46 cases left over from the original production period.

manufactured components. In particular, it seems that the reproduction engines were based upon original B46 cases left over from the original production period.

For the most part, the Banshee was a fairly typical North American big-bore racing engine of the early post-WW2 era. It featured disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction along with cross-flow loop scavenging, a lapped baffle piston, a sturdy automotive-style timer and a relatively high compression ratio of 10:1. It was specifically intended for operation on “racing fuels”, which by the standards of the day meant a methanol/castor oil or Avgas/mineral oil blend. With that compression ratio, operation on regular gasoline might be somewhat problematic.

For the most part, the Banshee was a fairly typical North American big-bore racing engine of the early post-WW2 era. It featured disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction along with cross-flow loop scavenging, a lapped baffle piston, a sturdy automotive-style timer and a relatively high compression ratio of 10:1. It was specifically intended for operation on “racing fuels”, which by the standards of the day meant a methanol/castor oil or Avgas/mineral oil blend. With that compression ratio, operation on regular gasoline might be somewhat problematic. The Banshee’s most significant departure from the “normal” racing engine design layout was its use of only a single ball-race at the rear of the crankshaft instead of the more usual twin ball-races. The portion of the shaft forward of the ball-race was carried in a bronze bushing.

The Banshee’s most significant departure from the “normal” racing engine design layout was its use of only a single ball-race at the rear of the crankshaft instead of the more usual twin ball-races. The portion of the shaft forward of the ball-race was carried in a bronze bushing. A ball-race at the loaded (rear) end of the shaft does far more to absorb loads, offset friction losses and minimize wear than a front race. In addition, the need to accommodate a second ball-race inevitably adds extra weight and bulk to the engine while contributing relatively little to its performance. Finally, the extra ball race represents an increase in cost and complexity for a minimal return. It's very likely that the thinking behind this design decision followed the above lines. A number of notable manufacturers of classic racing engines adopted the single ball-race approach in the 1950’s, including

A ball-race at the loaded (rear) end of the shaft does far more to absorb loads, offset friction losses and minimize wear than a front race. In addition, the need to accommodate a second ball-race inevitably adds extra weight and bulk to the engine while contributing relatively little to its performance. Finally, the extra ball race represents an increase in cost and complexity for a minimal return. It's very likely that the thinking behind this design decision followed the above lines. A number of notable manufacturers of classic racing engines adopted the single ball-race approach in the 1950’s, including  The rest of the engine is relatively conventional in functional terms, although it does embody a few individualistic structural details. The main such feature is the construction of the crankcase. This is laterally split vertically immediately aft of the beam mounting lugs. The front casting incorporates the main bearing, ball race housing and beam mounting lugs in a single unit. The rear casting includes both the backplate and the induction tube in unit. The two castings are held together by three machine screws inserted from the front and engaging with threads formed in the rear casting.

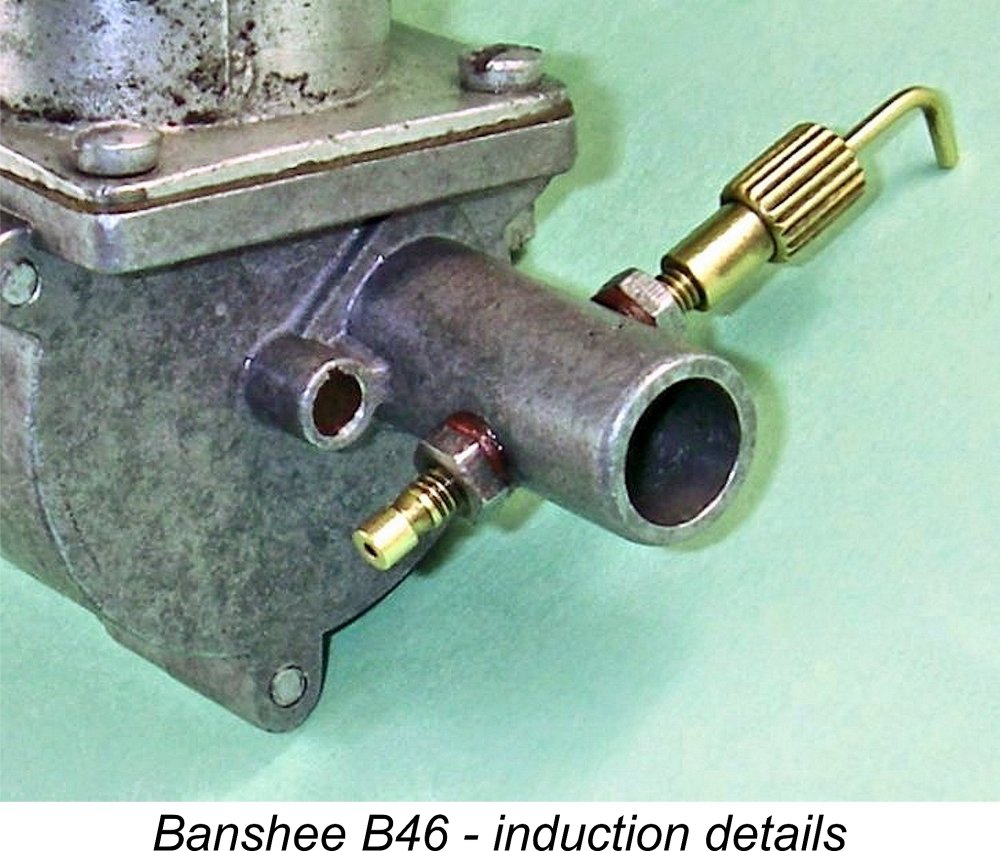

The rest of the engine is relatively conventional in functional terms, although it does embody a few individualistic structural details. The main such feature is the construction of the crankcase. This is laterally split vertically immediately aft of the beam mounting lugs. The front casting incorporates the main bearing, ball race housing and beam mounting lugs in a single unit. The rear casting includes both the backplate and the induction tube in unit. The two castings are held together by three machine screws inserted from the front and engaging with threads formed in the rear casting.  The thin-walled cylinder is machined from solid steel bar. The cooling fins are machined integrally with the cylinder itself, while both the bypass channel and exhaust stack are sheet brass components which are neatly brazed onto the cylinder’s surface. A square flange is brazed onto the base of the cylinder, which is secured to the crankcase by four machine screws passing through holes at the corners of the base flange to engage with tapped holes in the upper crankcase casting. A fibre gasket is used at this joint to ensure a seal. It was this gasket that was incorrectly installed on my example as received, creating a complete blockage of the bypass passage.

The thin-walled cylinder is machined from solid steel bar. The cooling fins are machined integrally with the cylinder itself, while both the bypass channel and exhaust stack are sheet brass components which are neatly brazed onto the cylinder’s surface. A square flange is brazed onto the base of the cylinder, which is secured to the crankcase by four machine screws passing through holes at the corners of the base flange to engage with tapped holes in the upper crankcase casting. A fibre gasket is used at this joint to ensure a seal. It was this gasket that was incorrectly installed on my example as received, creating a complete blockage of the bypass passage.  Following the completion of brazing operations, the cylinders of the earlier examples like my illustrated B46 example were nickel or cadmium plated. At some later point during the engine's original

Following the completion of brazing operations, the cylinders of the earlier examples like my illustrated B46 example were nickel or cadmium plated. At some later point during the engine's original

employed - another measure seemingly aimed at minimising reciprocating weight. This pin is retained in its bosses through the use of small circlips formed from bronze wire - a very forward-looking provision.

employed - another measure seemingly aimed at minimising reciprocating weight. This pin is retained in its bosses through the use of small circlips formed from bronze wire - a very forward-looking provision.  The very substantial crankshaft is machined in one piece from a steel billet. It features a crankdisc which is quite heavily counterbalanced. The crankpin is extended to drive the aluminium alloy rotary valve disc. This disc is provided with a wedged-shaped cutaway to time the opening and closing of the induction system appropriately.

The very substantial crankshaft is machined in one piece from a steel billet. It features a crankdisc which is quite heavily counterbalanced. The crankpin is extended to drive the aluminium alloy rotary valve disc. This disc is provided with a wedged-shaped cutaway to time the opening and closing of the induction system appropriately.

Given my example's excessively leaky piston/cylinder fit, I'm unable to comment on the engine's performance. Looking at the design objectively, I wouldn't expect it to be a world-beater - the skinny bypass passage appears to me to represent an impediment to really high performance. We might see something like 0.600 BHP @ 12,500 rpm - I wouldn't expect much more. The dwell period of 70 degrees appears inadequate to accommodate speeds much higher than this.

Given my example's excessively leaky piston/cylinder fit, I'm unable to comment on the engine's performance. Looking at the design objectively, I wouldn't expect it to be a world-beater - the skinny bypass passage appears to me to represent an impediment to really high performance. We might see something like 0.600 BHP @ 12,500 rpm - I wouldn't expect much more. The dwell period of 70 degrees appears inadequate to accommodate speeds much higher than this.