|

|

The O.S. K6 Replica

Although this fine motor was produced in a single limited edition, it was manufactured in substantial numbers, consequently remaining in fairly steady circulation as a collectible today. This being the case, I felt that present and potential future owners might welcome the provision of some relevant on-line information. As many model engine enthusiasts will doubtless know, the production of replicas of certain highly-regarded model engines goes back a surprisingly long way - all the way back to the 1950 Swiss Fischer Castor 2.5 cc replica of the original radial-mount Elfin 249 PB diesel of 1949. Unlike most later replicas, that particular model was not motivated by demand from the collector community (which didn’t exist at that time) but rather by the unavailability of the original Elfin in Switzerland as of 1950. The superb Swiss AMRO replica of the Dooling 61 was similarly motivated. However, the motivation for the production of such replicas changed as time went by. Over the years, the inevitable decrease in the supply of surviving examples of many classic model engines as they became worn out, lost or discarded was accompanied by a simultaneous increase in the number of people having an interest in owning, experiencing or even flying some of these long out-of-production designs. By the time that the early 1970’s rolled around, the interest in both the collecting and flying of vintage and classic model engines had grown sufficiently to exert an influence upon the marketplace.

In consequence, thoughts naturally began to turn towards the notion of producing latter-day replicas of the more highly-sought classic engines which could be made more generally available. By the mid 1980's, the replica concept was in full implementation in Australia and elsewhere for a wide variety of classic model engines which were seen as particularly desirable. Gordon Burford went on to produce other replicas, including his fine Deezil, C.I.E. and Elfin 249 units. In Britain, Dunham Engineering based their entire model engine business portfolio on the production of replicas and retros, as detailed elsewhere.

In 1986 a situation arose which was to raise the bar in terms of a manufacturer re-creating his own earlier product. The famous Osaka-based Japanese manufacturer O.S. reached its 50th anniversary, having been founded in 1936 by then 19 year old Shigeo Ogawa. I’ve summarized the early years of the O.S. enterprise in a separate article about the company’s twin-stack .29 cuin. sparkie.

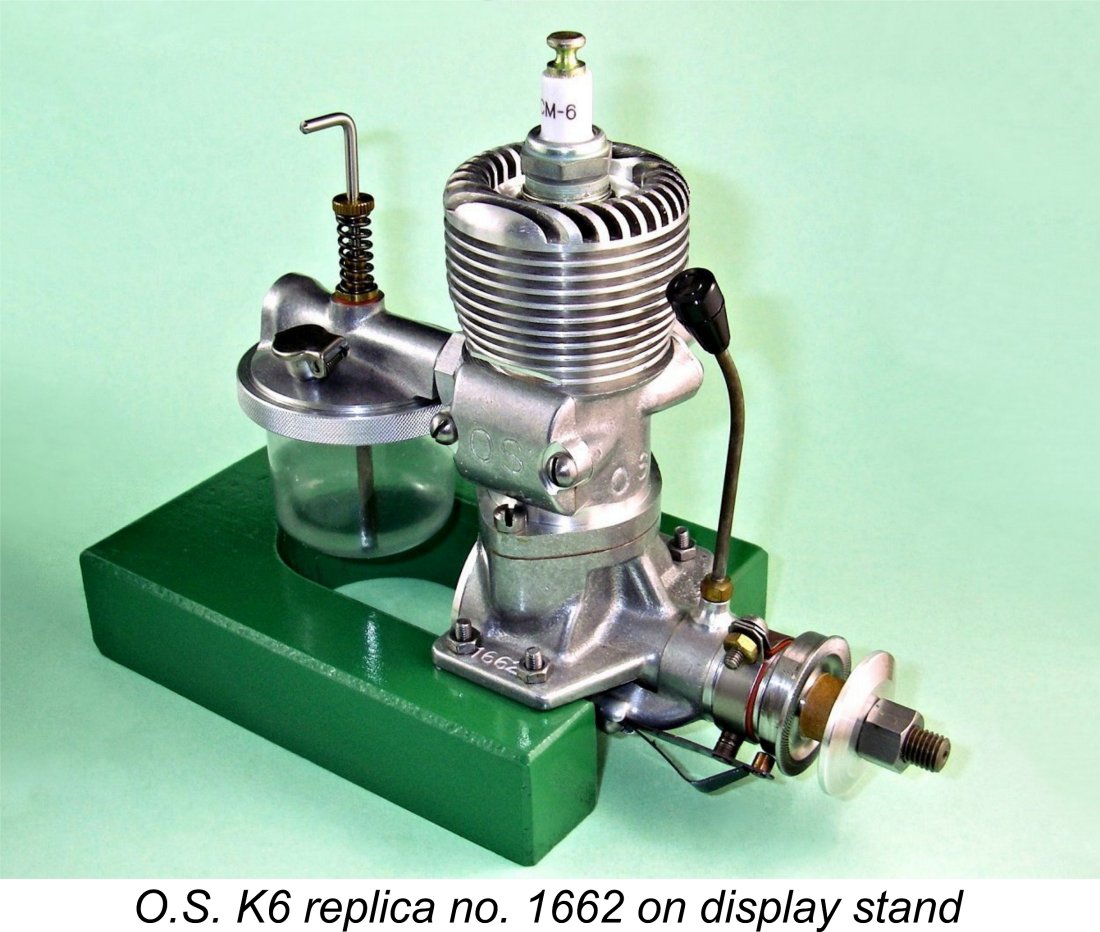

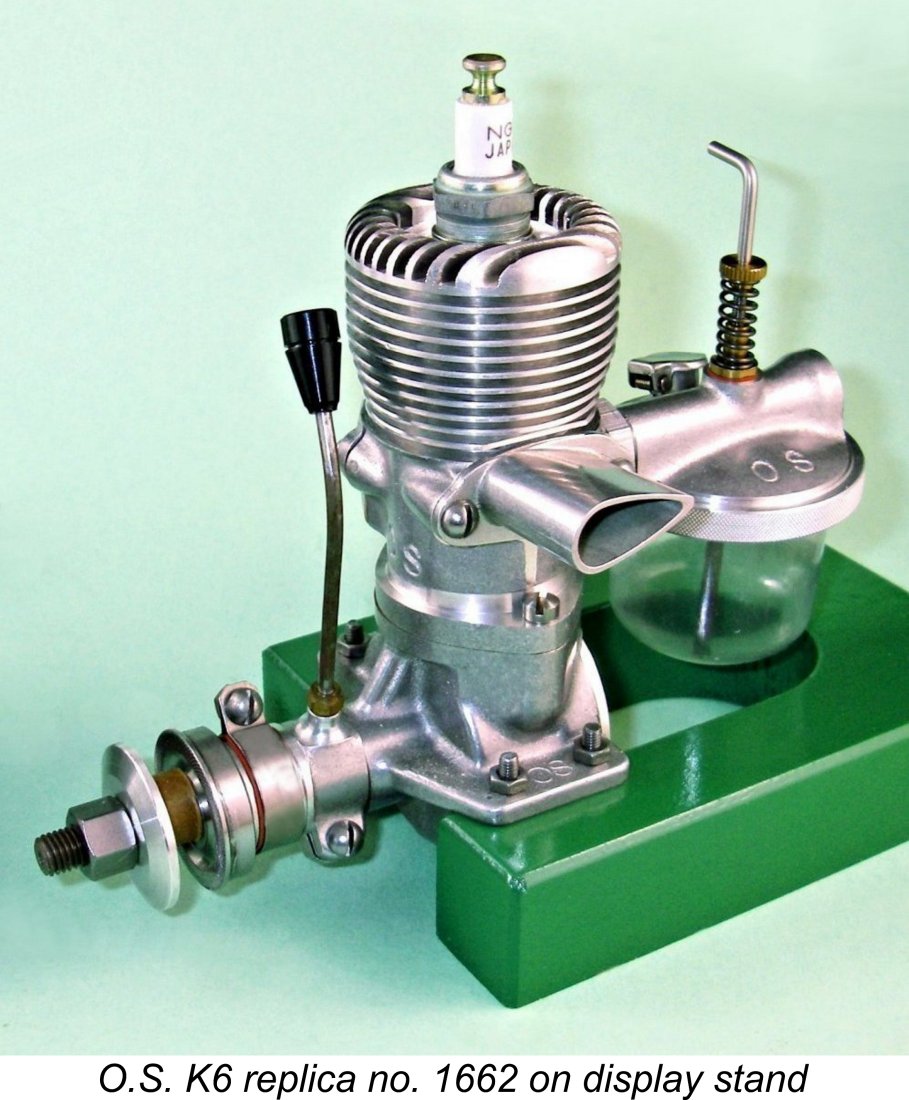

The engine was also the subject of a fairly detailed review by Peter Chinn which appeared in the June 1988 issue of "Model Airplane News". Although this article was very informative as regards the engine's construction, it didn't include any data on the engine's performance and handling - unusual for a Peter Chinn review. I'll attempt to make up this deficiency later in this article. As befitted a limited-edition commemorative offering, the sparkling quality of the overall O.S. K6 replica package shone through in all respects - no detail was overlooked. Most importantly, the quality of the engine itself was nothing short of superb - all aspects of its production were executed to the very highest standards. To complement this, the engine came comprehensively packaged in a sturdy high-quality period-labelled cardboard box complete with green-painted wooden display stand, NGK 10 mm spark plug, ignition coil, condenser, wiring, full English-language instructions and a facsimile of the original Japanese-language booklet that accompanied the original 1940 Type 6 engine. Description

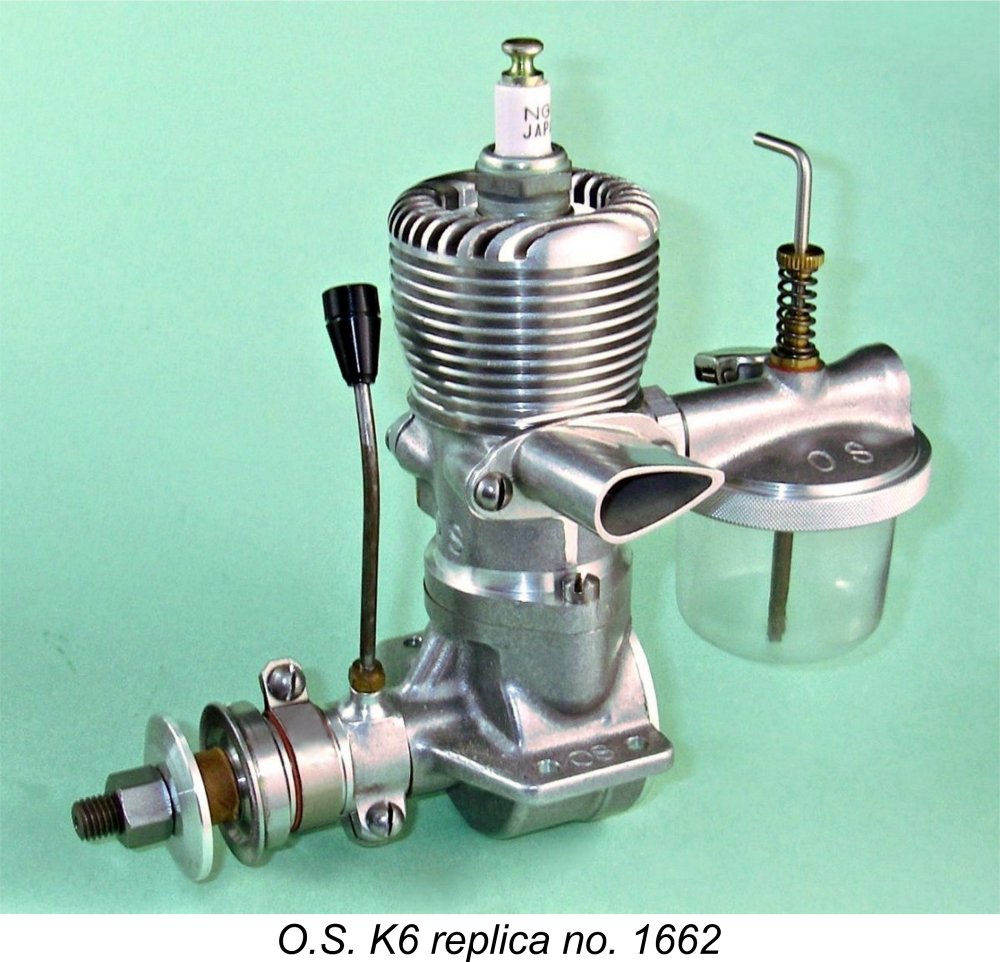

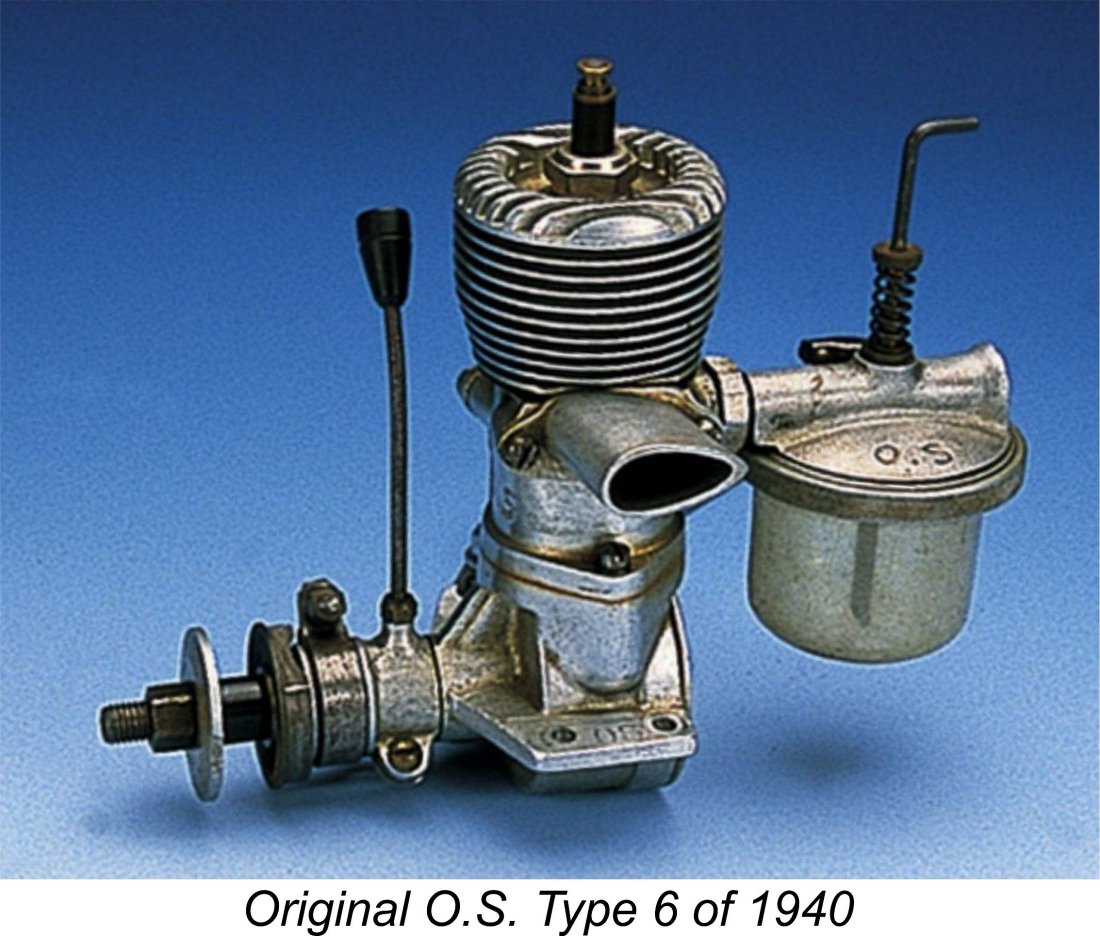

Although it gives an extremely convincing impression of the original engine, the replica displays a number of divergences from the design of the original K6 of 1940, most of them for the better. To start with, the quality of the castings is far higher, as is the general standard of finish. Moreover, the original engine used a composite crankshaft featuring a brazed-in-place crankweb, while the replica employs a seemingly more dependable one-piece component. In both cases, the crankweb was counterbalanced. The upper cylinder unit on the replica is secured to the main crankcase by only two machine screws - the original engine used three screws. The timer on the replica is also different, being of the simple type using a flat leaf spring. The original used a more complex timer design featuring a coil spring. The bypass arrangements too are different - that on the original was cast into the upper cylinder unit, while the replica uses an external bypass sealed by a cover which is secured using two screws. The bore and stroke of the original O.S. Type 6 of 1940 were 23.0 mm and 22.6 mm respectively for a displacement of 9.391 cc (0.573 cuin.). At the time, the use of over-square internal geometry was highly unusual. In the replica, the stroke was rounded up to 23.0 mm, which combined with the unchanged 23.0 mm bore to yield a displacement of 9.556 cc (0.583 cuin.). The replica engine weighs a checked 334 gm (11.8 ounces) as illustrated with timer, plug and tank but without the ignition support system.

The bypass passage is of the external type, being sealed from the atmosphere by a separate cover which is secured by two machine screws. The resulting closed passage is supplied with mixture at its lower end through a piston port which is fully opened at bottom dead centre. The Internally, the lapped ringless cast iron baffle piston acts upon a sturdy forged bronze rod, driving a one-piece steel crankshaft which runs in a bronze bushing. An open "Bunch type" timer, a combined drive washer/cam and an aluminum prop washer with steel prop-nut complete the front of the engine. The bent timer arm has a small plastic control knob fitted for improved grip. At the rear, the machined investment-cast intake includes the tank top in unit. The fuel supply assembly screws into a boss at the rear of the cylinder, being secured by a lock-nut. This allows the engine to be operated in any For the reassurance of latter-day operators, the “modernized” English-language running instructions state (quite correctly) that operation of this engine is essentially the same as that for a glow-plug unit apart from the need to keep the ignition support system connected and use the correct fuel. As readers of my separate article on spark ignition operation will know, this advice is completely sound, as are the balance of the very clear instructions. A full range of entirely appropriate safety warnings and operational hints are included, along with a wiring diagram. The O.S. K6 replica was offered initially at $250 when introduced in 1986. However, a flurry of discount activity in the US market had dropped the price into the $160-$190 range by February 1988. At these prices, the engines were scooped up by collectors, most of whom appear to have kept them as un-run New-in-Box collectibles. Very few of them appear to have been used in models or even bench-run. New un-run boxed examples continue to appear periodically on eBay and elsewhere today, commanding somewhat higher prices even now. I acquired my own New-in-Box example no. 1662 in 2022 through eBay. The O.S. K6 Replica on Test I mentioned earlier that Peter Chinn's June 1998 review of the K6 replica didn't include any test data. During the research phase of this article's preparation, I was somewhat surprised to discover that the O.S. K6 replica had been the subject of a previous test report by others. This appeared in the February 2000 issue of the British "R/C Model Flyer" magazine, the author being an individual who styled himself as "Motormouth". I have no clue as to his real identity.

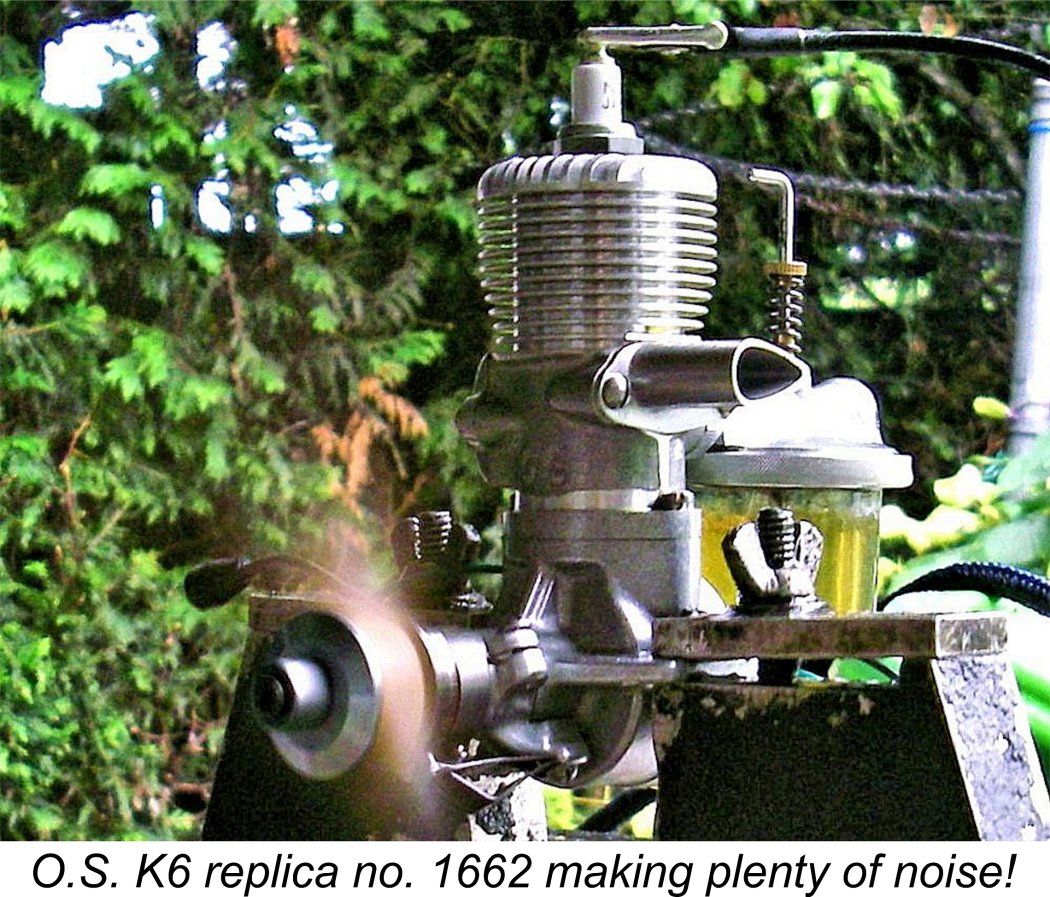

This report represented a very worthy effort to document the O.S. K6 replica. I'm grateful to my good mate Maris Dislers for bringing it to my attention. Its only drawback was (and remains) the fact that it is only accessible to those who have access to a copy of the relevant issue of the magazine. This being the case, I felt that the publication of my own independent evaluation would have value. There is a school of thought which says that pristine examples of desirable collectible engines should not be run, since that has a negative impact upon their “value”. Well, I suppose that depends on the basis upon which you assign a “value” to a given engine. If your definition of ”value” is confined to the price which someone else might be willing to pay you for that engine, then I suppose that being un-run might add something to the figure. However, confining yourself to assigning a value to the engines in your collection solely on the basis of their potential resale value appears to me to be missing the main point of model engine collecting. It reduces the activity to the level of a financial investment rather than a hobby based upon a consuming interest amounting to a passion. I freely admit to being firmly in the “passion” camp myself! For me, an engine’s value very much includes both what it represents and what it can do! Moreover, I actually place a higher value on an engine that has shown that it can run than one which might run but has yet to prove it! That being the case, I had absolutely no qualms about setting up my un-run New-in-Box example of the O.S. K6 replica (engine no. 1662) in the test stand to give it a chance to do what it was designed to do - make some noise burning a little gasoline while swinging a substantial airscrew! OK, so it would no longer be a brand-new un-run example - so what?!? I would derive far more pleasure from experiencing its operational qualities than I could ever get from simply staring at it sitting on a shelf or storing it out of sight in a box! Allowing for airborne pickup, the recommendation of a 12x6 prop suggests that the engine should peak at a slightly higher speed than that which it could achieve on the bench using a 12x6. Accordingly, I elected to begin with a Top Flite 12x6 Power Point wooden prop fitted. Since I don't have any torque absorption data for that prop, I also planned to try a 12x6 APC, for which I do have a reasonably dependable figure. I also intended to try a 12x5 Zinger in the expectation that the engine might turn this a little faster, thus more closely approximating airborne rpm on a 12x6. However, I had no intention of subjecting this engine to a full test - all I was looking for was a very rough estimate of its performance using the recommended airscrew.

The instructions specified the use of a 12x6 wood airscrew with this engine. In keeping with the plastic tank, the recommended fuel was a 4:1 mixture of gasoline and mineral oil - the use of methanol would have dire effects upon that tank! The manufacturers actually stated that this ratio could be diluted to 5:1 once the engine was fully broken in. Despite this advice, I elected to use my usual spark ignition blend of 75% Coleman Camp Fuel (white gas equivalent) and 25% SAE 60 mineral oil (AeroShell 120), of which I had an ample supply on hand ready mixed. Set up in the test stand with a Larry Davidson SSIGNCO transistorized spark ignition support system and a full tank of fuel, the O.S. looked and felt all ready to go. It seemed a little tight, evidently requiring some running-in, but it didn't present any issues which might affect starting and running. I set the needle at 3 turns open, gave it a few choked turns, switched on the ignition and got down to it. The engine turned out to be a very prompt starter, with no prime being necessary at any time. I immediately found that at 3 turns the mixture was way too rich. It turned out that around 2¼ turns was about right for running slightly rich around the four stroke/two-stroke break. Given the engine's clear need for a break-in period prior to being turned loose, I kept it running in rich slightly retarded mode, only leaning it out briefly and advancing the spark momentarily to take some speed readings. I had no intention of giving it a full break-in since I wasn't planning to fly it myself.

The engine turned the 12x6 Top Flite Power Point prop at around 5,000 rpm but seemed to be a little unhappy doing so - it evidently didn't like that airscrew. I don't have any torque absorption data for that prop, but experience has demonstrated it to be a rather "slow" 12x6. A switch to a significantly "faster" 12x6 APC got the engine up to 6,200 rpm, exactly the same figure achieved on this prop by our mate "Motormouth". This implied an output of around 0.200 BHP at that speed. A slightly faster Zinger 12x5 wood prop was turned at 6,300 rpm for an approximate output of 0.195 BHP, clearly implying that the peak lay right around 6,200 rpm. I therefore concur with "Motormouth's" estimate of a peak output of around 0.200 BHP @ 6,200 rpm. Overall, I found the O.S. K6 replica to be an extremely well-made and user-friendly engine. It was a fitting memento of Shigeo Ogawa's first 50 years as a model engine manufacturer. Summary and Conclusion

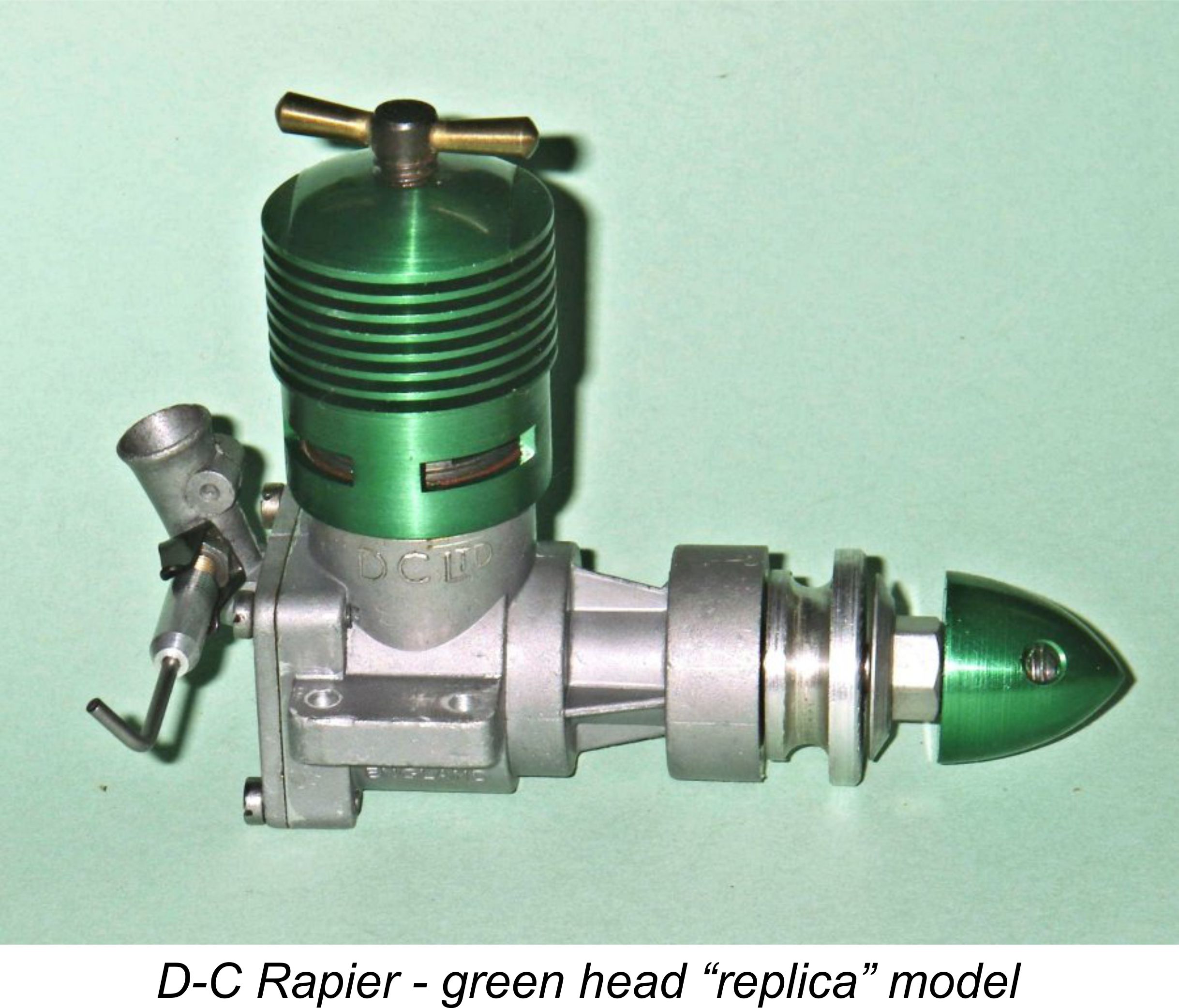

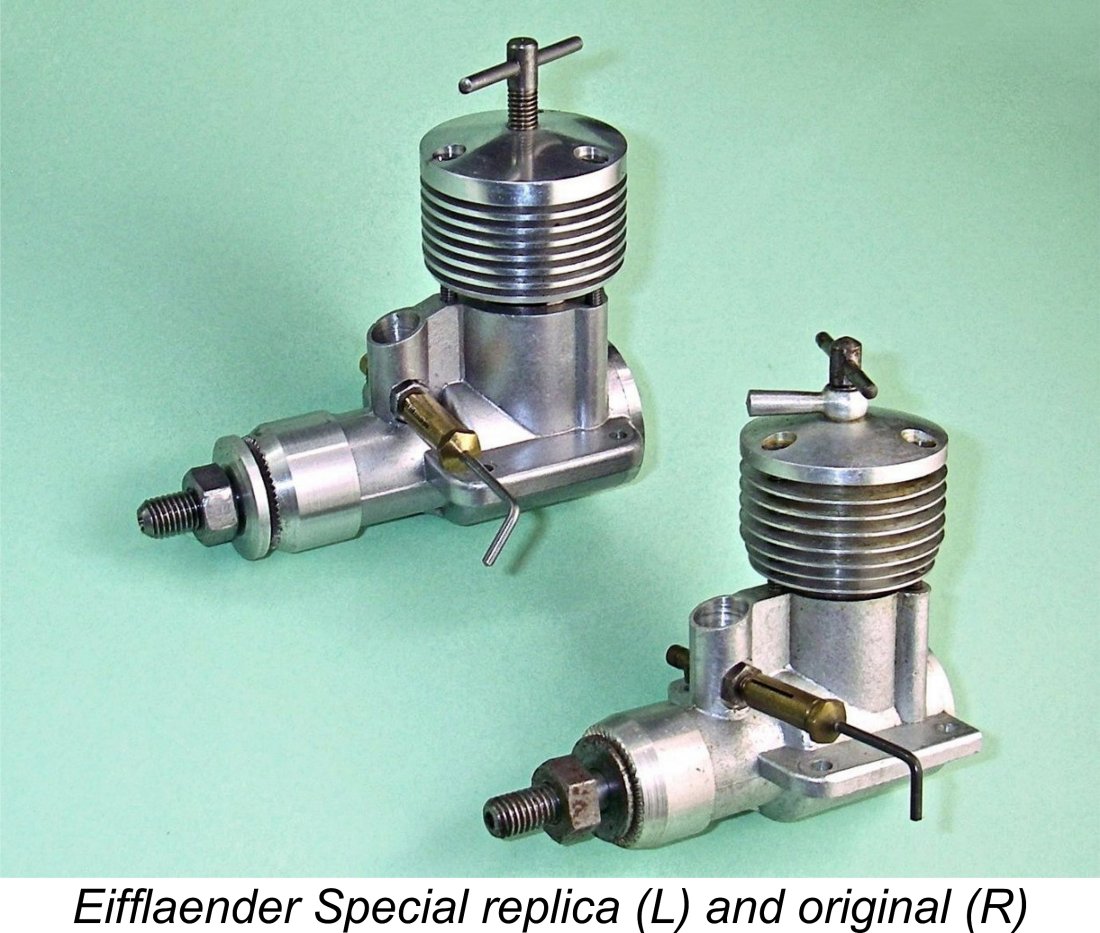

During the mid 1990’s, the iconic English firm of Progress Aero Works (P.A.W.) of Macclesfield offered a near-replica of their original commercial offering, the Eifflaender Special of 1958. Like its D-C Rapier predecessor mentioned earlier, this wasn’t an exact replica, but it was certainly close enough to give a very good impression of its classic progenitor.

It’s worth pausing here to recall once more that the vast majority of these engines were snapped up by collectors. A few of them doubtless saw service in the hands of aficionados of old-time modelling, but even those examples would doubtless have been well cared for. The manufacturers actually anticipated this situation, since they stated quite explicitly that their usual repair and spare parts services would not be available for this engine given its limited edition replica status. Clearly they were not expecting these engines to receive much actual use. Despite this, the K6 replica would doubtless have given excellent service in the field if anyone had cared to give it a try. My point is that the majority of those 2,000 engines are almost certainly still with us, most of them in perfect condition. This being the case, anyone having an interest in acquiring an example should be able to find one without too much trouble, just as I did. And if you like old-time sparkies manufactured to a truly superb standard, I guarantee that you won’t be disappointed! ________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2022

|

| |

In this article I’ll provide a few observations on an engine which has been deservedly viewed as a desirable collectible but which has seldom appeared on the flying field in actual service. I’ll present a condensed review of the superb O.S. K6 Replica spark ignition engine, of which a single batch of 2,000 examples was produced in 1986.

In this article I’ll provide a few observations on an engine which has been deservedly viewed as a desirable collectible but which has seldom appeared on the flying field in actual service. I’ll present a condensed review of the superb O.S. K6 Replica spark ignition engine, of which a single batch of 2,000 examples was produced in 1986.  Now it must be borne in mind that this was in the days before eBay – the acquisition of an original example of any classic model engine was very much a matter of luck and circumstance. Basically, you had to somehow identify and then contact an individual who owned the desired engine and was willing to sell it or trade it to you. Moreover, you had to get in there first before any other similarly-motivated individuals did so! The

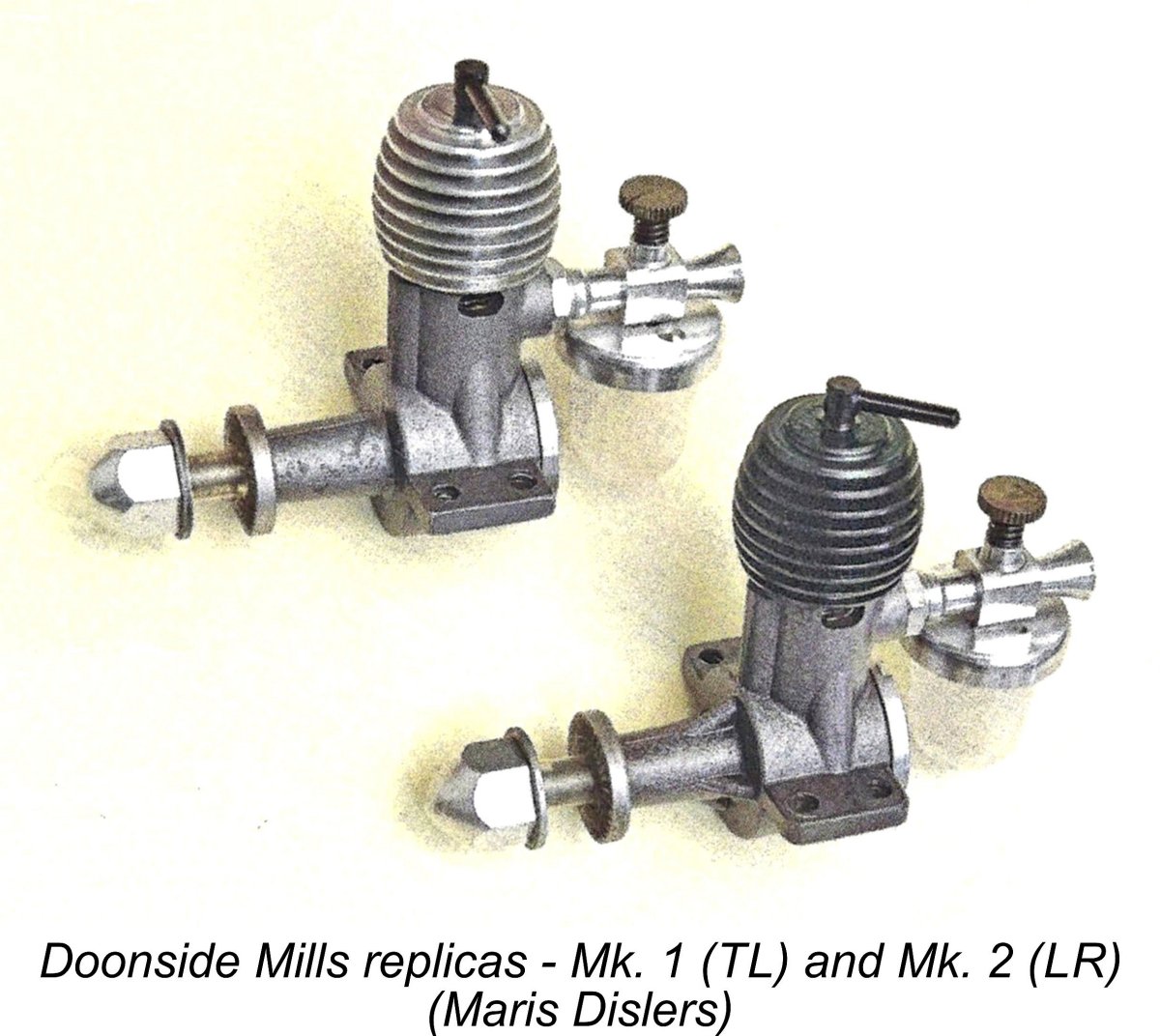

Now it must be borne in mind that this was in the days before eBay – the acquisition of an original example of any classic model engine was very much a matter of luck and circumstance. Basically, you had to somehow identify and then contact an individual who owned the desired engine and was willing to sell it or trade it to you. Moreover, you had to get in there first before any other similarly-motivated individuals did so! The  Australia took a leading role in jump-starting the replica movement with the 1974 release of the Doonside Mills engines which were manufactured by

Australia took a leading role in jump-starting the replica movement with the 1974 release of the Doonside Mills engines which were manufactured by

One of the early products of the O.S. company was the 1940 Type 6 unit of 0.57 cuin. (9.39 cc) nominal displacement. It’s pretty clear that, for whatever reason, Shigeo Ogawa retained a very high regard for this engine down through the years, because it was that design which was selected by the company for a 1986 limited edition reproduction to mark the 69 year old Ogawa’s 50 years as a model engine manufacturer. A production run of 2,000 examples was duly completed. As far as I’m able to ascertain, this was the first time that a major manufacturer had created a replica of one of its own pioneering models.

One of the early products of the O.S. company was the 1940 Type 6 unit of 0.57 cuin. (9.39 cc) nominal displacement. It’s pretty clear that, for whatever reason, Shigeo Ogawa retained a very high regard for this engine down through the years, because it was that design which was selected by the company for a 1986 limited edition reproduction to mark the 69 year old Ogawa’s 50 years as a model engine manufacturer. A production run of 2,000 examples was duly completed. As far as I’m able to ascertain, this was the first time that a major manufacturer had created a replica of one of its own pioneering models.

The K6 replica is a largely faithful re-creation of the original O.S. Type 6 of 1940. Like its progenitor, it is a single-cylinder two-stroke plain bearing spark ignition motor featuring side-port induction along with cross-flow loop scavenging and a side-stack exhaust.

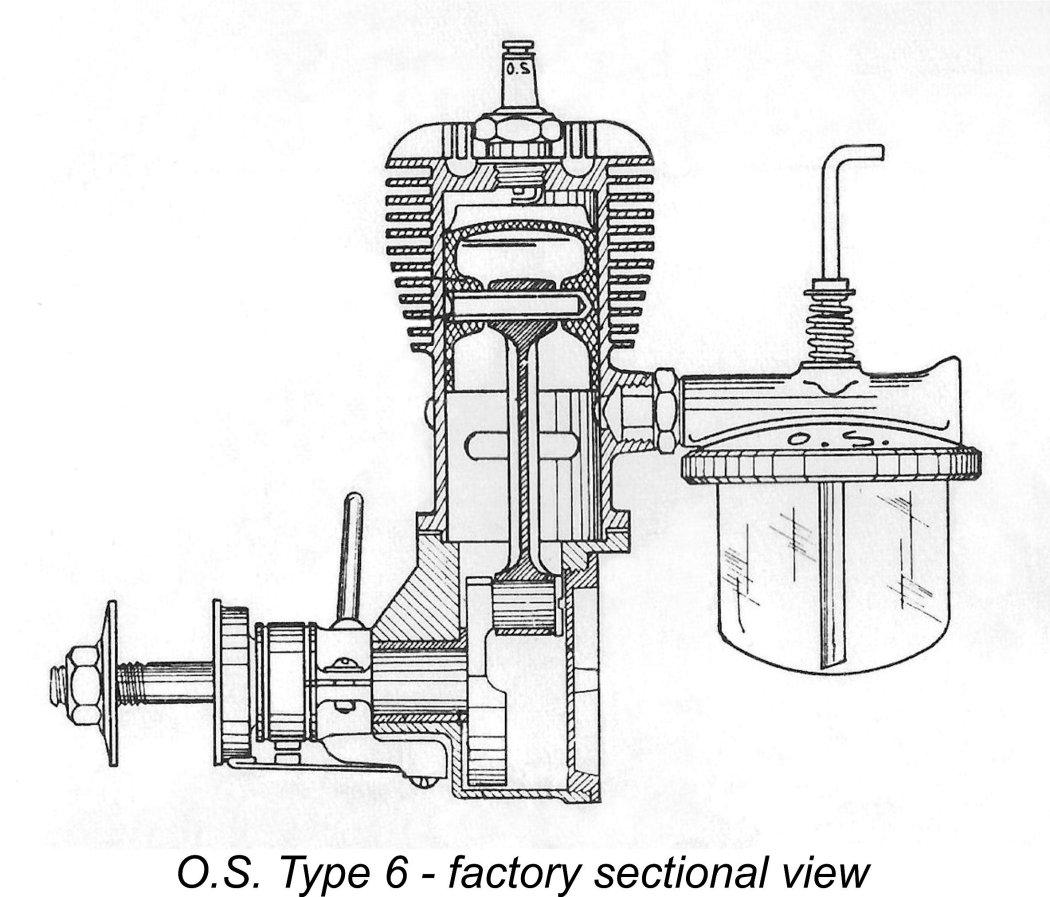

The K6 replica is a largely faithful re-creation of the original O.S. Type 6 of 1940. Like its progenitor, it is a single-cylinder two-stroke plain bearing spark ignition motor featuring side-port induction along with cross-flow loop scavenging and a side-stack exhaust. The K6 replica is built up around separate high-quality upper and lower main investment castings which are fastened together with two large machine screws, one on each side. Integrally-cast beam mounts and a screw-in backplate are features of the main crankcase, while the one-piece cylinder casting includes the cylinder head in unit, with both barrel and head fins being machined into the casting. A very thin-walled ferrous liner is inserted into the upper casting from below. This appears to be blind-bored, because it is topped by an internally-threaded spigot which protrudes through the head to accommodate the plug. The accompanying sectioned view from the original 1940 Japanese-language instruction leaflet seems to confirm this impression.

The K6 replica is built up around separate high-quality upper and lower main investment castings which are fastened together with two large machine screws, one on each side. Integrally-cast beam mounts and a screw-in backplate are features of the main crankcase, while the one-piece cylinder casting includes the cylinder head in unit, with both barrel and head fins being machined into the casting. A very thin-walled ferrous liner is inserted into the upper casting from below. This appears to be blind-bored, because it is topped by an internally-threaded spigot which protrudes through the head to accommodate the plug. The accompanying sectioned view from the original 1940 Japanese-language instruction leaflet seems to confirm this impression.

desired mounting orientation using the standard tank. The needle valve is tensioned by a coil spring. A Gits cap is incorporated to serve as the fuel filler. The plastic tank is secured to the top by an internally threaded knurled ring.

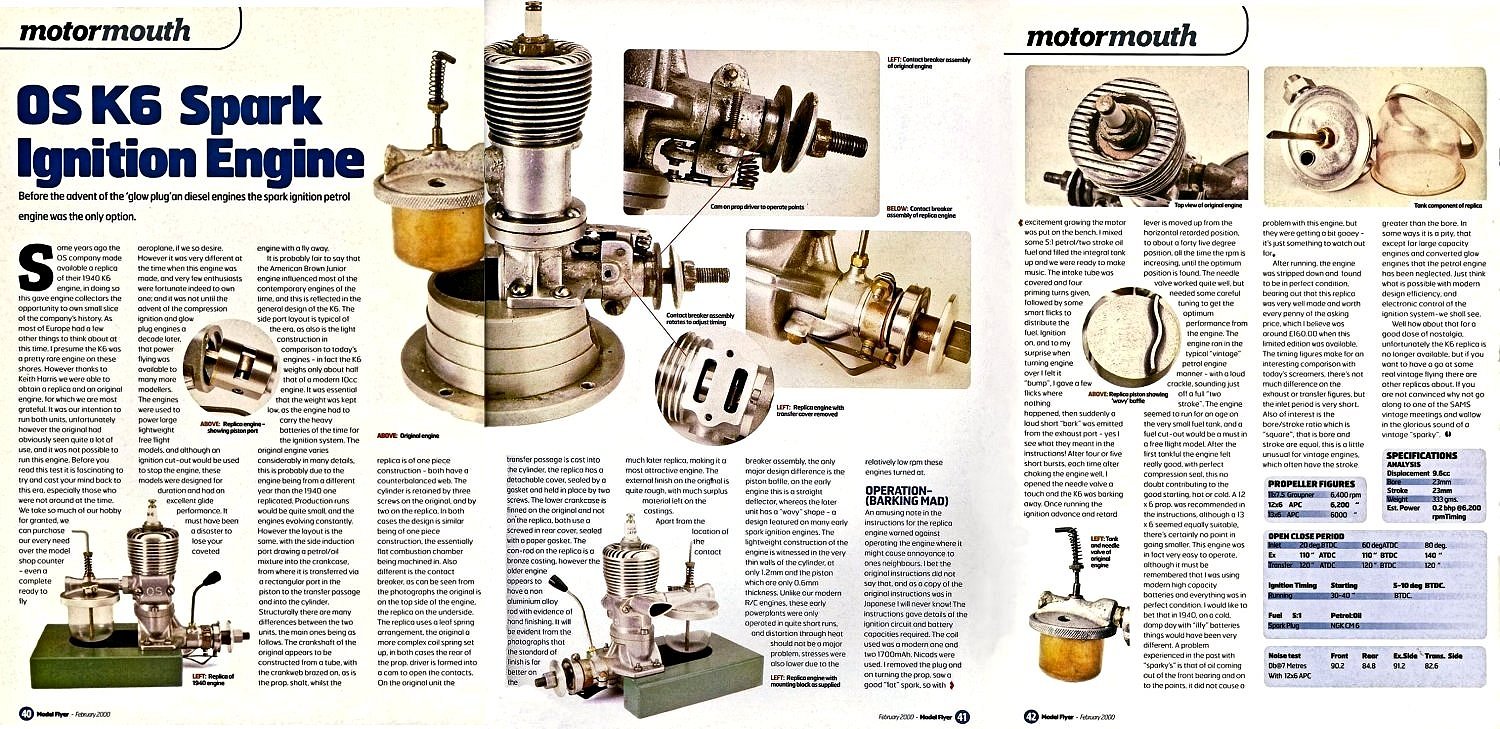

desired mounting orientation using the standard tank. The needle valve is tensioned by a coil spring. A Gits cap is incorporated to serve as the fuel filler. The plastic tank is secured to the top by an internally threaded knurled ring. The report included a quite detailed structural comparison between the replica K6 and a non-operational original example to which the writer had access. In common with Chinn's earlier review, the article was extremely complimentary regarding the standards to which the replica was constructed and finished, considering it to be significantly better than that exhibited by the original. Starting was found to be perfectly straightforward, while running qualities were well up to acceptable standards for a design dating from 1940. An estimated peak output of 0.200 BHP @ 6,200 rpm was cited - a not unreasonable performance for a 1940 design.

The report included a quite detailed structural comparison between the replica K6 and a non-operational original example to which the writer had access. In common with Chinn's earlier review, the article was extremely complimentary regarding the standards to which the replica was constructed and finished, considering it to be significantly better than that exhibited by the original. Starting was found to be perfectly straightforward, while running qualities were well up to acceptable standards for a design dating from 1940. An estimated peak output of 0.200 BHP @ 6,200 rpm was cited - a not unreasonable performance for a 1940 design.  As noted earlier, the English-language instructions with the replica were worded very specifically to provide reassurance to latter-day users that operation of the K6 was basically the same as operation of a glow-plug motor apart from the need for the ignition system to remain connected while the engine was running. To a modeller of “classic” vintage like myself, it was amusing to note the other difference cited by the manufacturer, namely that the un-muffled engine was loud!! Owners were advised to choose their operating locations accordingly!

As noted earlier, the English-language instructions with the replica were worded very specifically to provide reassurance to latter-day users that operation of the K6 was basically the same as operation of a glow-plug motor apart from the need for the ignition system to remain connected while the engine was running. To a modeller of “classic” vintage like myself, it was amusing to note the other difference cited by the manufacturer, namely that the un-muffled engine was loud!! Owners were advised to choose their operating locations accordingly! A couple of rich runs with the 12x6 prop seemed to smooth things out a little, encourging me to lean the engine out briefly to see how it was performing at this early stage in its working life. It immediately became apparent that the needle valve setting was very sensitive - the amount of needle movement required to go from four-stroking to a lean cut-out was very small. It would definitely be smart to set this engine a little on the rich side when in use in a model. In his review, "Motormouth" had characterized the engine as running "in a typical vintage petrol engine manner - with a loud crackle, sounding just off a full two-stroke". My experience confirmed this observation completely. Trying for a smooth full two-stroke generally just stopped the engine. Set a little rich, running was steady and dependable.

A couple of rich runs with the 12x6 prop seemed to smooth things out a little, encourging me to lean the engine out briefly to see how it was performing at this early stage in its working life. It immediately became apparent that the needle valve setting was very sensitive - the amount of needle movement required to go from four-stroking to a lean cut-out was very small. It would definitely be smart to set this engine a little on the rich side when in use in a model. In his review, "Motormouth" had characterized the engine as running "in a typical vintage petrol engine manner - with a loud crackle, sounding just off a full two-stroke". My experience confirmed this observation completely. Trying for a smooth full two-stroke generally just stopped the engine. Set a little rich, running was steady and dependable.  The O.S. K6 replica was the first truly notable reproduction of one of their own long-discontinued pioneering models by a “name” manufacturer, but it wasn’t the last. In fact, a little-known example originating in my adopted country of Canada actually followed hard on its heels in 1987 when George Barrett, the original manufacturer of the very rare

The O.S. K6 replica was the first truly notable reproduction of one of their own long-discontinued pioneering models by a “name” manufacturer, but it wasn’t the last. In fact, a little-known example originating in my adopted country of Canada actually followed hard on its heels in 1987 when George Barrett, the original manufacturer of the very rare

I’m sure that there are other examples which I’ve overlooked, but suffice it to say that no manufacturer has ever reached as far back into its own past as the O.S. company when bringing one of their own early models back to life. The original production run of 2,000 engines sold out pretty quickly in the 1980’s, and deservedly so.

I’m sure that there are other examples which I’ve overlooked, but suffice it to say that no manufacturer has ever reached as far back into its own past as the O.S. company when bringing one of their own early models back to life. The original production run of 2,000 engines sold out pretty quickly in the 1980’s, and deservedly so.