|

|

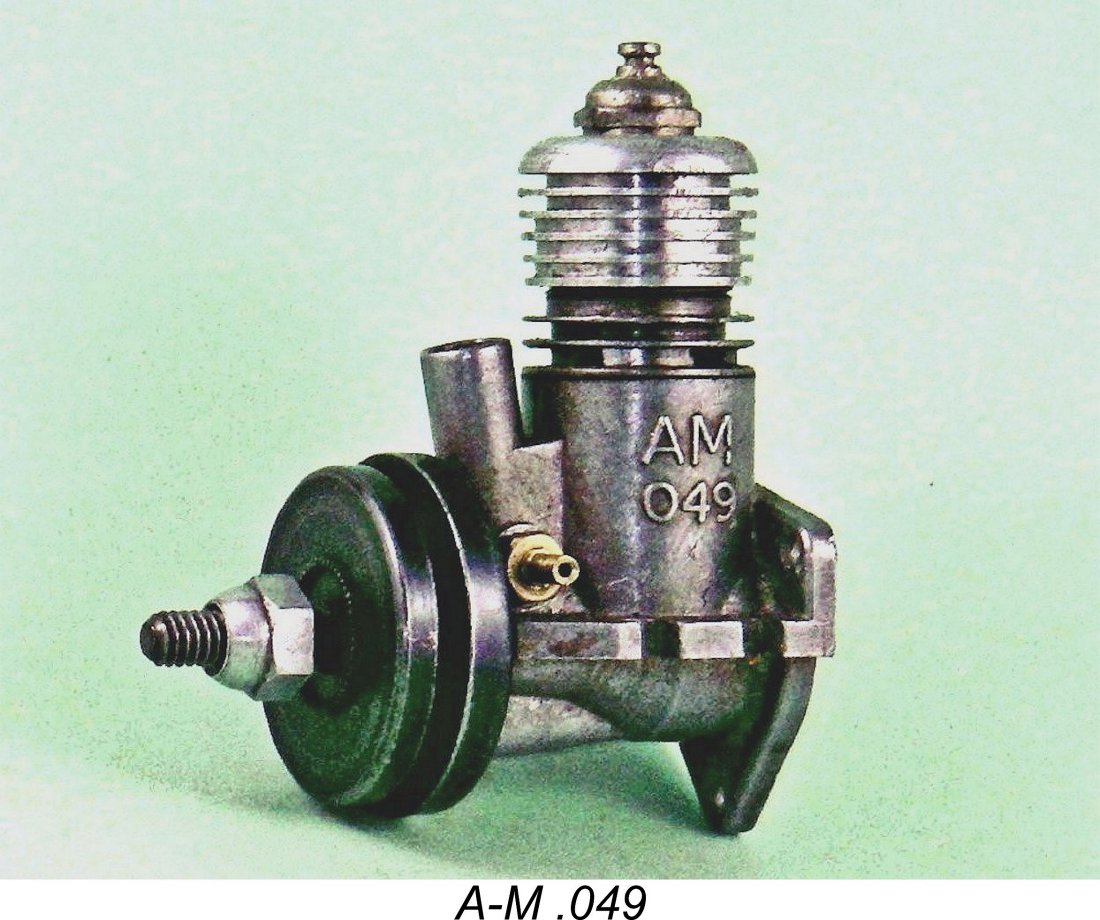

England’s ½A Enigma - the A-M .049

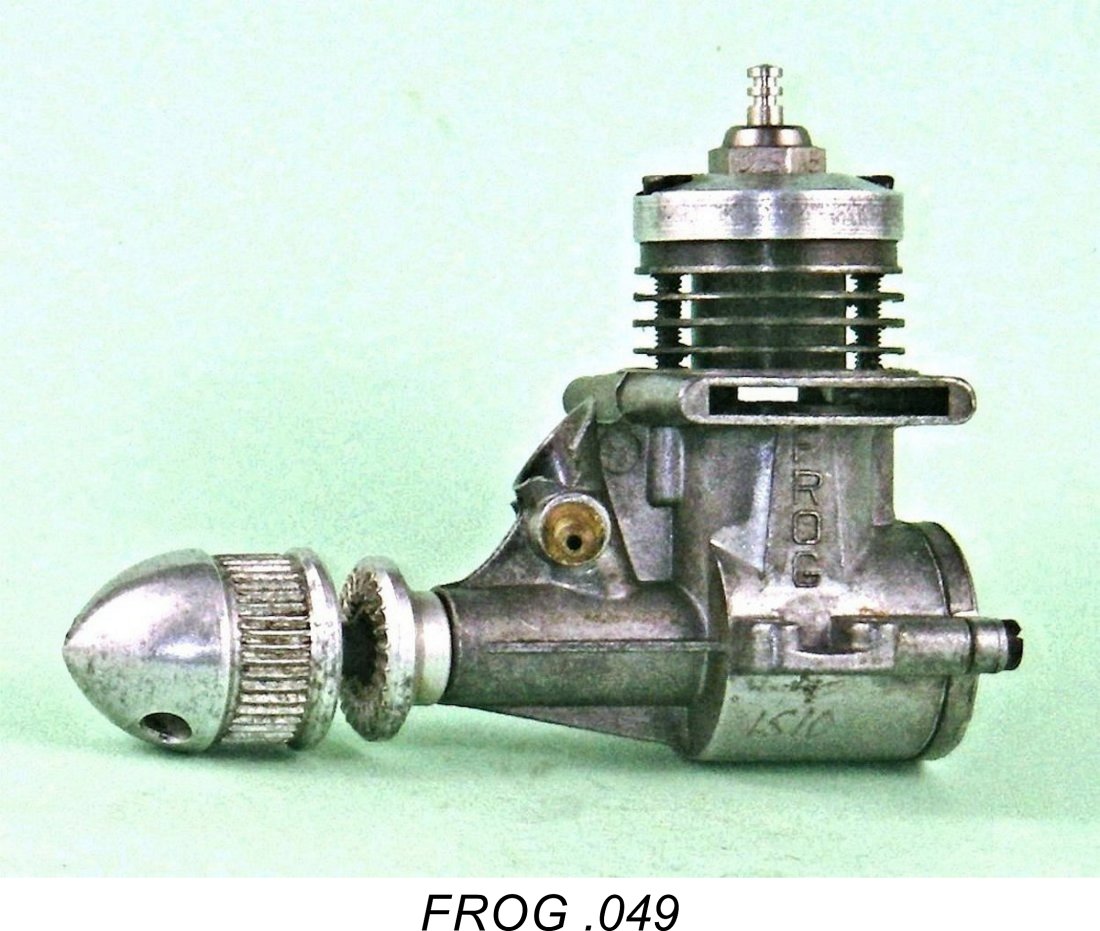

I’ve already covered three of the participants in this particular contest between British manufacturers - the Cobra .049, the FROG .049 and the D-C Bantam. I've also covered the E.D. Pep ½A model which was the sole British diesel to enter the lists against the glowpluggers during this period. To complete my review of this interesting and in retrospect significant episode in British model engine history, it’s now time to turn my attention to one of the less successful contestants in that particular competition between British manufacturers - the Allen-Mercury (A-M) .049. This little motor was presented as a product of the well-established firm of D. J. Allen Engineering and was marketed by Mercury Models under the Allen-Mercury banner. It turns out that it has an interesting story to tell! I've covered the broader story of the Allen-Mercury (A-M) and MERCO engines in a separate article to be found elsewhere on this website.

At the time of which we are speaking, the production facilities of D. J. Allen Engineering were located at 28 Angel Factory Colony, Angel Road, Edmonton, North London. Angel Road is now part of the North Circular Road, having greatly changed since the A-M factory was located there. The former Angel Factory Colony now forms part of the Lea Valley Trading Estate.

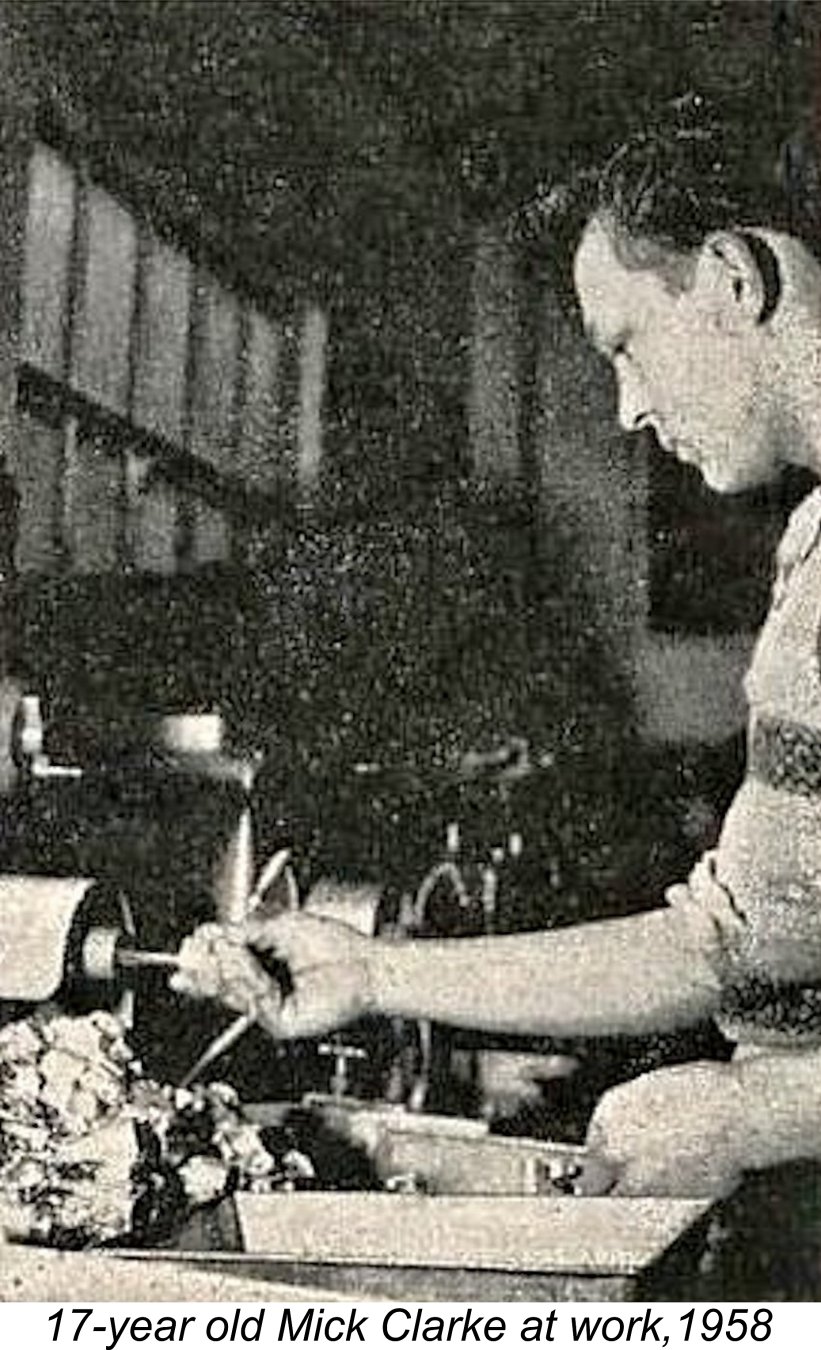

Following the initial publication of this article on MEN in 2011 these doubts were reinforced through the receipt of a wealth of additional first-hand information from reader Mick Clarke, a former West Essex club-mate of Dennis Allen who worked at Allen Engineering during the entire period in which the A-M .049 was marketed. Mick actually entered the company’s employ as a 16-year old apprentice in May 1957, concurrently with the firm’s move into its expanded premises at Angel Factory Colony. He remained with the company until September 1962, shortly before it was re-organized under new ownership in 1963. On the basis of his own first-hand knowledge, Mick was able to comment on a number of matters regarding which I had only been able to speculate in the original text of this article. Happily, he confirmed that almost all of my speculations had been correct! Mick also added some extremely interesting points of clarification regarding both the A-M .049's origins and its production history. Such insights from one who was “there” at the time have a value that cannot be overstated, and my very sincere thanks go out to Mick for his kindness in helping me to present as complete a history of the A-M .049 as possible. With that pleasant duty fulfilled, I’m now in a position to get on with the story. But first, it’s necessary to set the scene by paying a visit to America ……………. Background The ½A (.049 cuin.) glow-plug motor revolution had begun in the USA during the late 1940’s with the K&B, Atwood, Anderson and OK marques leading the way. By the early ‘50’s, ½A engines constituted a significant proportion of the total model engine market in North America. The burgeoning popularity of Ready-to-Fly (RTF) plastic models which were mostly powered by .049 glow-plug engines added greatly to the overall demand for such powerplants. The sheer size of the market for these little motors supported extremely large production volumes, with the economies of mass production at such a large scale allowing them to be sold at remarkably low unit prices by world standards. My good mate Maris Dislers has very ably recounted the saga of the American ½A motors in a separate article to be found elsewhere on this website. Since free flight and control-line modelling predominated at the time in question, this situation brought power modelling within the financial reach of anyone having an interest and a few dollars to spend - no need to invest in expensive R/C gear, complex control hardware, powerful throttle-equipped engines and large airframes! The hobby was both far simpler and more challenging back then - it required commitment, ingenuity, time and skill as opposed to mere money! I'm glad that I cut my modelling teeth back in those days ........ wouldn't have missed it for the world!

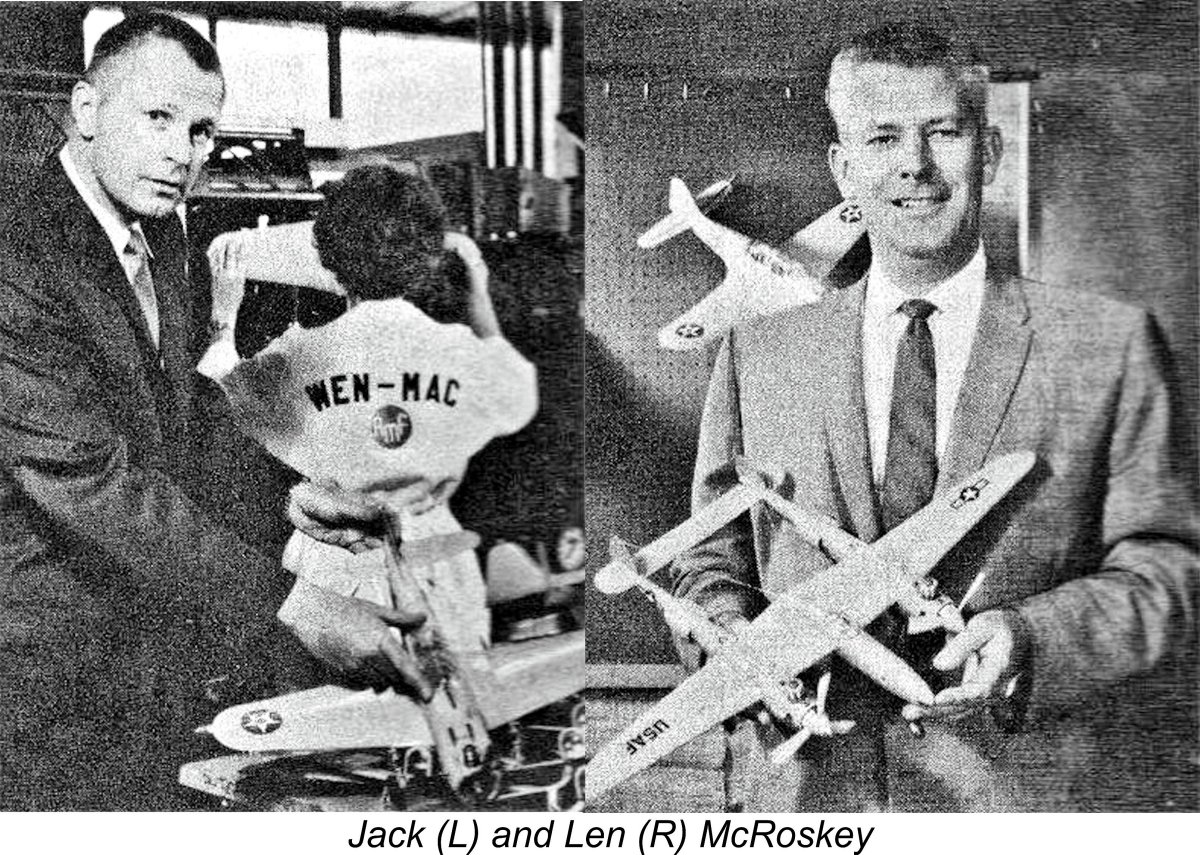

One of the American companies which entered the RTF market during the early 1950’s was the Wen-Mac Corporation of Culver City, California (in effect, a west-side suburb of Los Angeles). This company was established in 1950 by the brothers Len and Jack McRoskey in partnership with Adolph Wenland, hence the Wen-Mac name. Their main product line was a range of plastic RTF model airplanes which initially used engines obtained from outside manufacturers. The Wen-Mac venture was an immediate success. By 1952 sales had grown to the point where the company was obtaining engines in bulk from no fewer than three different manufacturers (OK, Atwood and Anderson) and was still facing a shortfall in supply! The answer was obvious - make their own engines! They initiated this step in 1952 with the involvement of the legendary Atwood had previously marketed a line of highly-regarded larger engines under his own name and had also been closely associated with the early post-war North American marketing efforts of the Japanese O.S. company. Until 1958 Atwood continued to produce a line of basically similar small engines under his own name in competition with the Wen-Mac units before moving into an ill-fated and short-lived live steam venture and then going to work for Cox. The Wen-Mac model empire was built around a compact .049 cubic inch glow-plug motor which was sold by the hundreds of thousands in a bewildering number of different guises. Some of these were sold over the counter as normal “hobby” engines for owners to fit in power models of their own construction, while many others were used to power ready-to-use plastic models of all descriptions, of which Wen-Mac was a major producer on a world scale. Wen-Mac also manufactured fuel for use in their engines.

At this point the reader may be coming to the realization that sorting out the various Wen-Mac models is no easy task! Accordingly, our very sincere thanks are due to the late Tim Dannels for doing just that in his invaluable and highly recommended “American Model Engine Encyclopaedia” (AMEE). Production figures for Wen-Mac were quite astonishing, especially when looked at from a British viewpoint. At one point in the early 1960’s, production of the Wen-Mac .049 exceeded 5000 units per day! Reportedly, 15% of these were randomly selected for inspection and testing, and if a problem showed up the production line was halted until the cause was identified and corrected. To put this into perspective, it’s highly improbable that anywhere near 5,000 examples of the A-M .049 were made in total during the 15 months or so that it was on offer!

While all this was going on in America, modellers from Great Britain had indulged in a brief flirtation with glow-plug motors for general-purpose use in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s but since then had remained steadfastly true to the compression ignition (diesel) engine for all but a few specialized applications, especially in the smaller-displacement categories. The American ½A revolution had a parallel in Britain during 1950-52 when no fewer than four British manufacturers (Allbon, IMA (FROG), E.D. and Elfin) all released half-cc diesels. However, the craze for really small diesels passed relatively quickly and things soon got back to normal.

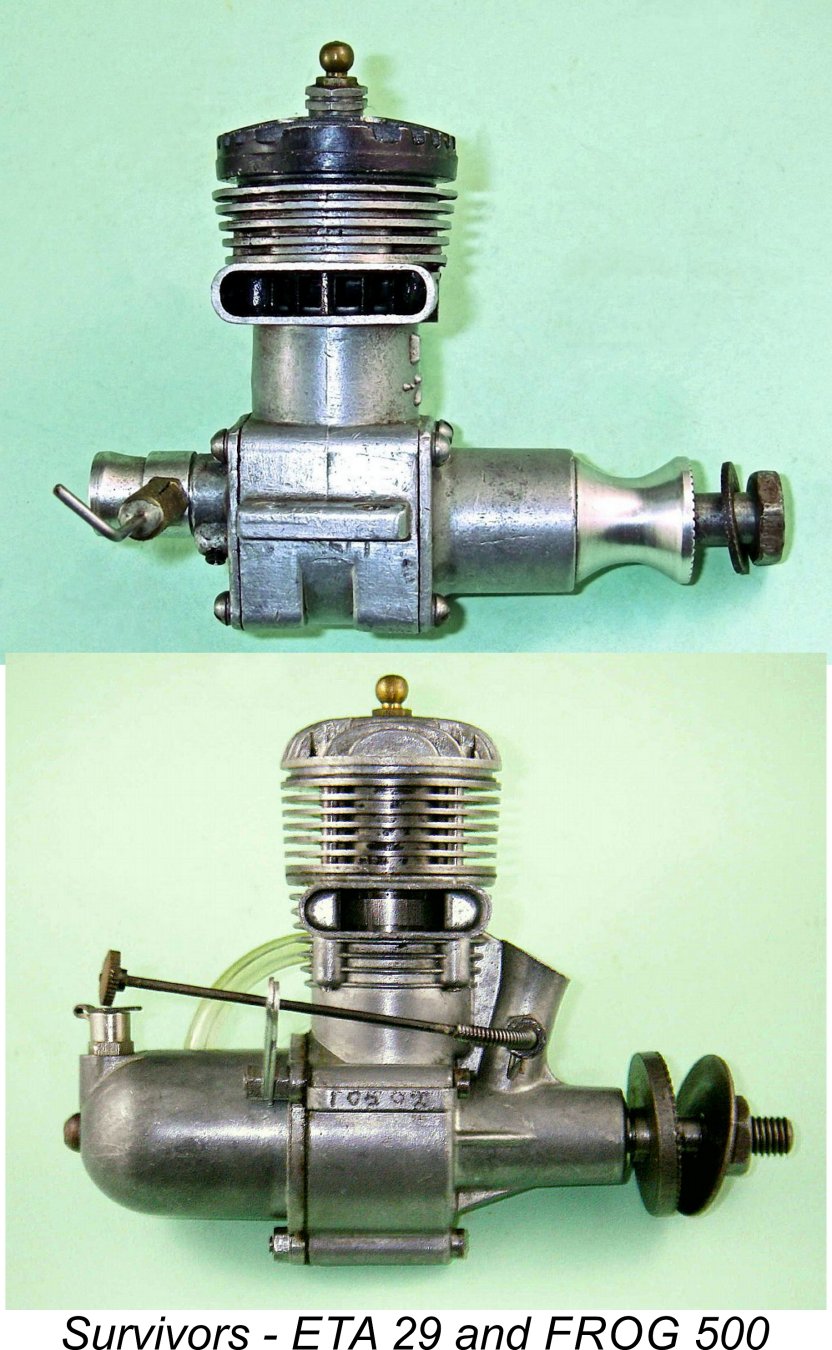

The most durable non-racing survivor of the early British glow-plug era was the trusty old standby FROG 500 of 4.92 cc displacement, which first appeared in late 1949 and deservedly remained a firm favourite among control-line sport and stunt fliers for many years thereafter. E.D. also offered a glow-plug conversion for their 2.46 cc Mk. III of 1948 as well as its 1951 replacement, the E.D. Mk. III Series 2 Racer, although this latter unit didn’t attract much attention since the Racer tended to perform better as a diesel for most purposes. The same was true of the AMCO 3.5 PB diesel, which was also offered for a time in glow-plug form. Apart from the short-lived J.B. glow-plug models and a glow-plug version of the FROG 149 Vibramatic, that was about it for general-purpose British glow-plug motors as the end of the ‘fifties approached - for the most part, diesels still predominated. By 1959 the British model engine industry was stagnating to a certain extent, leaving British modellers ready for something different. In addition, interest in radio control was on the rise. This set the stage for 1959 to become the turn-around year for glow-plug motors in Britain. 1959 - the Year of the Glow-plug in Britain

Moreover, the importation of the excellent glow-plug motors being produced in Japan was on the rise, spurred on by some very positive published test reports and high-profile contest successes. In addition, the popularity of R/C flying was steadily increasing, with British modellers becoming ever more aware of the superior throttling capabilities of glow-plug motors as opposed to diesels. These factors resulted in the British marketplace becoming increasingly receptive to the broader use of glow-plug ignition in place of the previously almost universal diesel.

The major objection in Britain to the use of the mainstream Cox ½A models was their adherence to radial mounting. By the time in question, British modellers had come down firmly in favour of beam mounting as their preference. In addition, the fact that one was more or less forced to use the Cox’s relatively bulky built-on metal tank was widely seen as a disadvantage - British modellers generally preferred to choose their own tank arrangements depending on the application. I can clearly recall the Cox .049 models being criticised on the flying field in very much these terms. In early 1959 a number of British manufacturers evaluated the situation and decided pretty much simultaneously to enter the ½A glow motor market themselves. This led immediately to a virtual replay of the 1950-52 half-cc diesel revolution, albeit this time with ½A glow-plug motors as the contestants. The sole newly-introduced contemporary ½A diesel contender was the ill-fated E.D. Pep, about which much more elsewhere.

The second option was to take the very easy route of producing a simple glow-plug conversion of an established diesel design. This would side-step the bulk of the development and tooling-up costs very nicely, but would probably fall short of producing the optimum results - multiple earlier examples from Allbon, AMCO, J.B., FROG and others had shown that a simple switch from diesel to glow-plug ignition rarely resulted in the best-possible performer. None of the three British manufacturers who entered this particular “competition” in 1959 had any appetite for the costly and time-consuming innovation option. Clearly being uncertain regarding the consumer reception of their glow-plug offerings, they all chose to hedge their bets to the extent possible. Both IMA (FROG) and D-C Ltd. elected to take the second option by producing inexpensive By contrast, Allen-Mercury (A-M) did not have an established diesel design in the appropriate displacement category, so the conversion option was not open to them. However they clearly shared their competitors’ desire to minimize both the time and the costs associated with the development of their own .049 glow-plug model. This ruled out the innovation possibility. Allen-Mercury therefore elected to take the third option, which was to side-step the entire development process at one fell swoop by simply purchasing the rights to an established design which had already been fully proven by others. The design with which they became associated was that of the previously-discussed Wen-Mac .049, then in its seventh year of production. The company which manufactured the A-M range, D. J. Allen Engineering Ltd., had been established in 1954 by Dennis Allen, a prominent West Essex club member who had been a leading control-line stunt flier during the pioneering era in Britain following WW2. Allen had acquired extensive experience with model engines Through his previously-established connection with Nicholls, Allen was able to secure a marketing agreement with Nicholl’s Mercury Models division, resulting in the engines being marketed accordingly under the Allen-Mercury label. The venture was a success from the outset, as fully recounted in a separate article to be found on this website. By 1959 the Allen-Mercury partnership had best-selling diesel models in 1 cc, 1.5 cc, 2.5 cc and 3.5 cc displacements. The A-M .049 thus represented the fifth displacement category into which Allen-Mercury had thrown their hats. As such, it had no predecessor in diesel form. Now there has never been any controversy surrounding the statement that the A-M .049 was a clone of the then-current Wen-Mac .049 - indeed, the promoters stated quite openly that it was marketed by them in Britain under license from the Wen-Mac Corporation. The question which has been asked from time to time, and which I’m asking here yet again, is whether or not it was actually manufactured by D. J. Allen Engineering or whether it was simply an example of “badge engineering” in the form of a Wen-Mac product made expressly to be marketed in Britain by Allen-Mercury and identified as an A-M product simply to give it a “made in England” cachet. It seems best to begin our examination of this question by taking a comparative look at the two models. Description

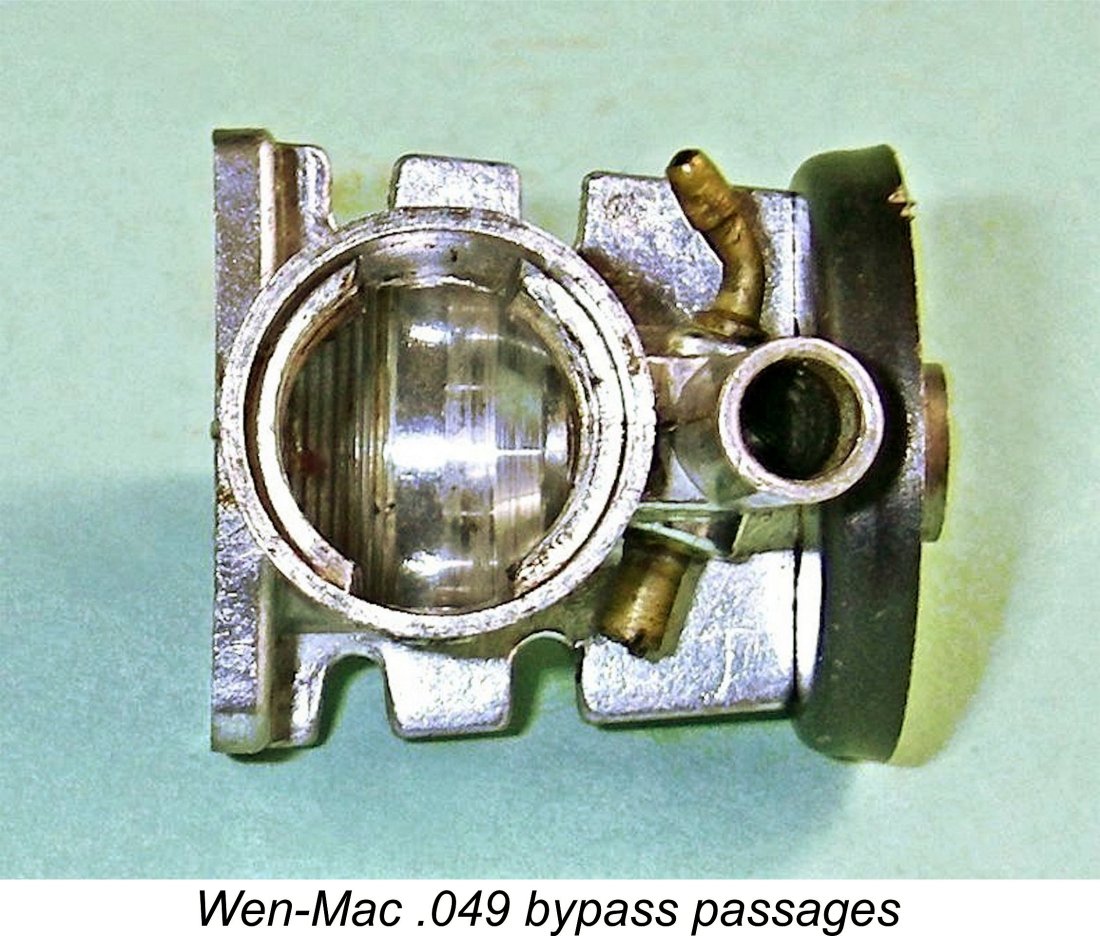

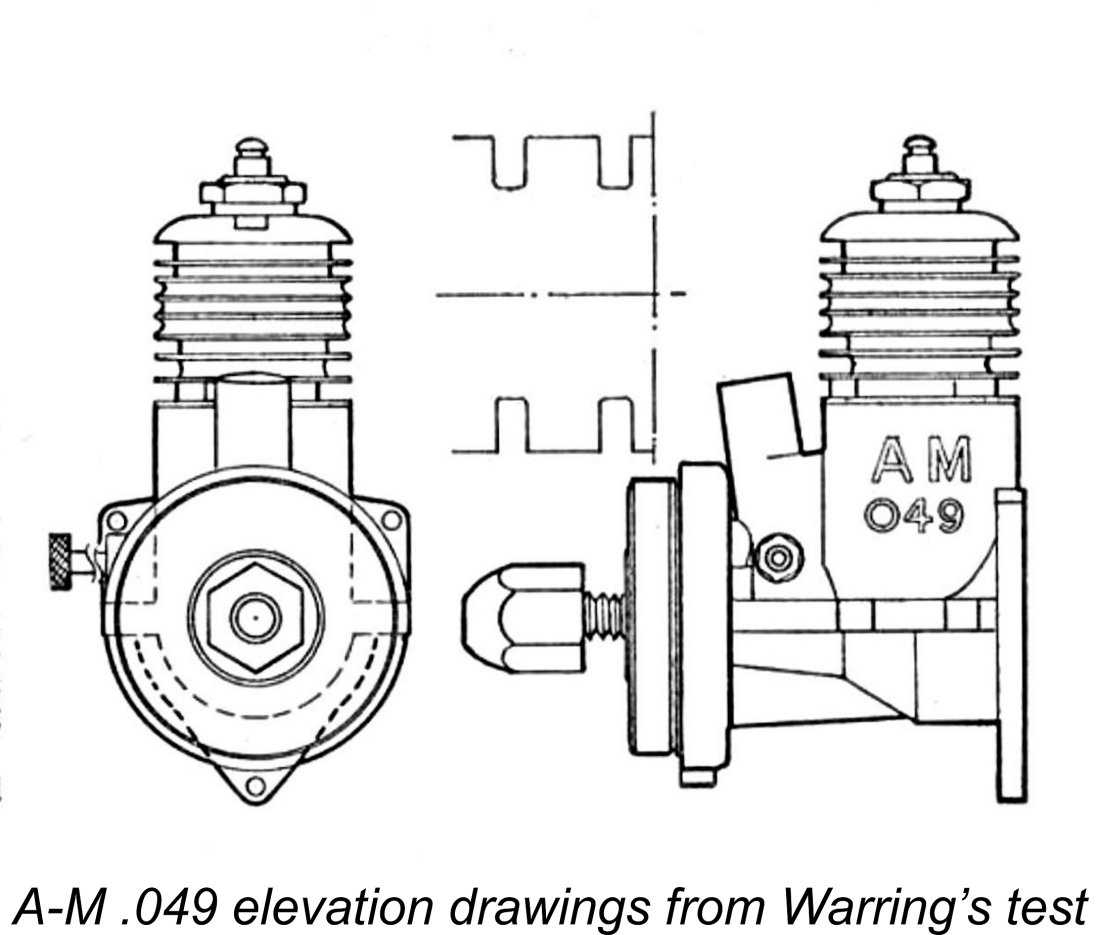

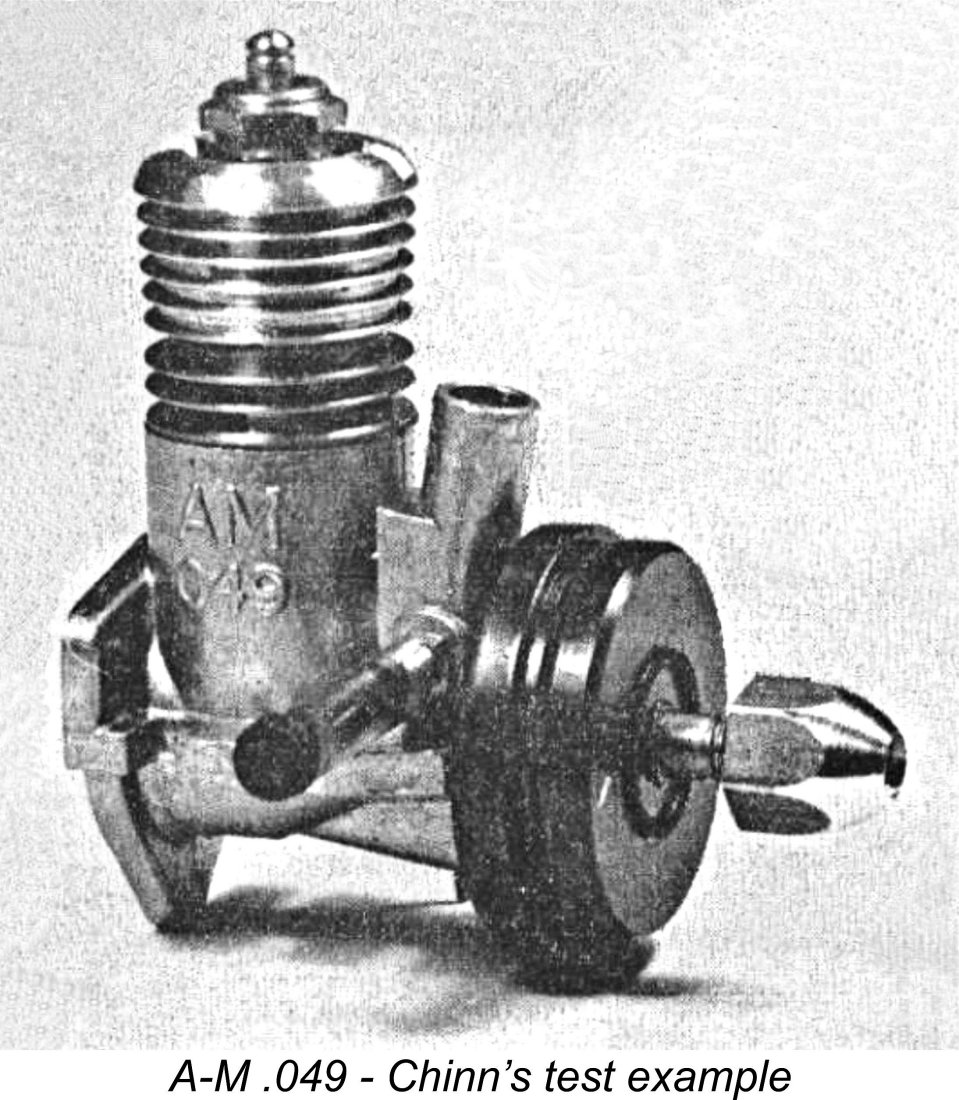

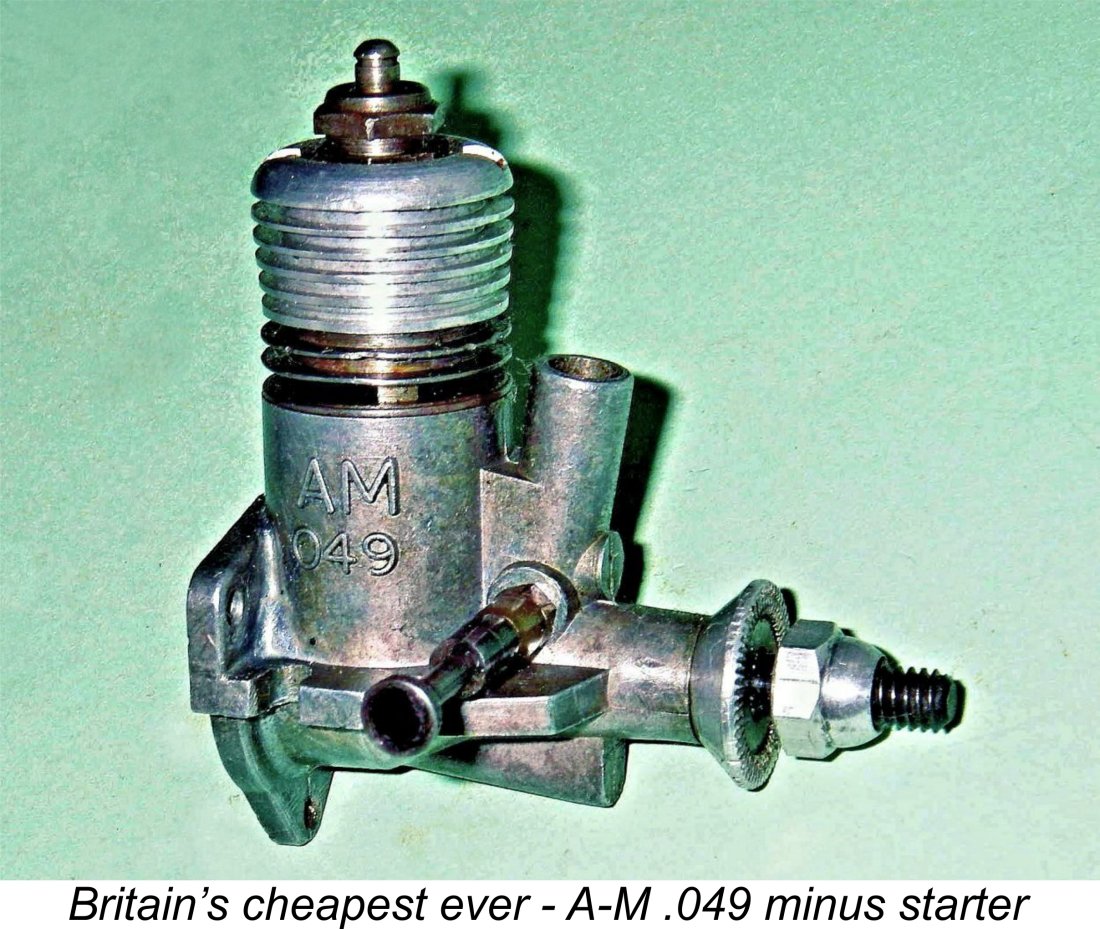

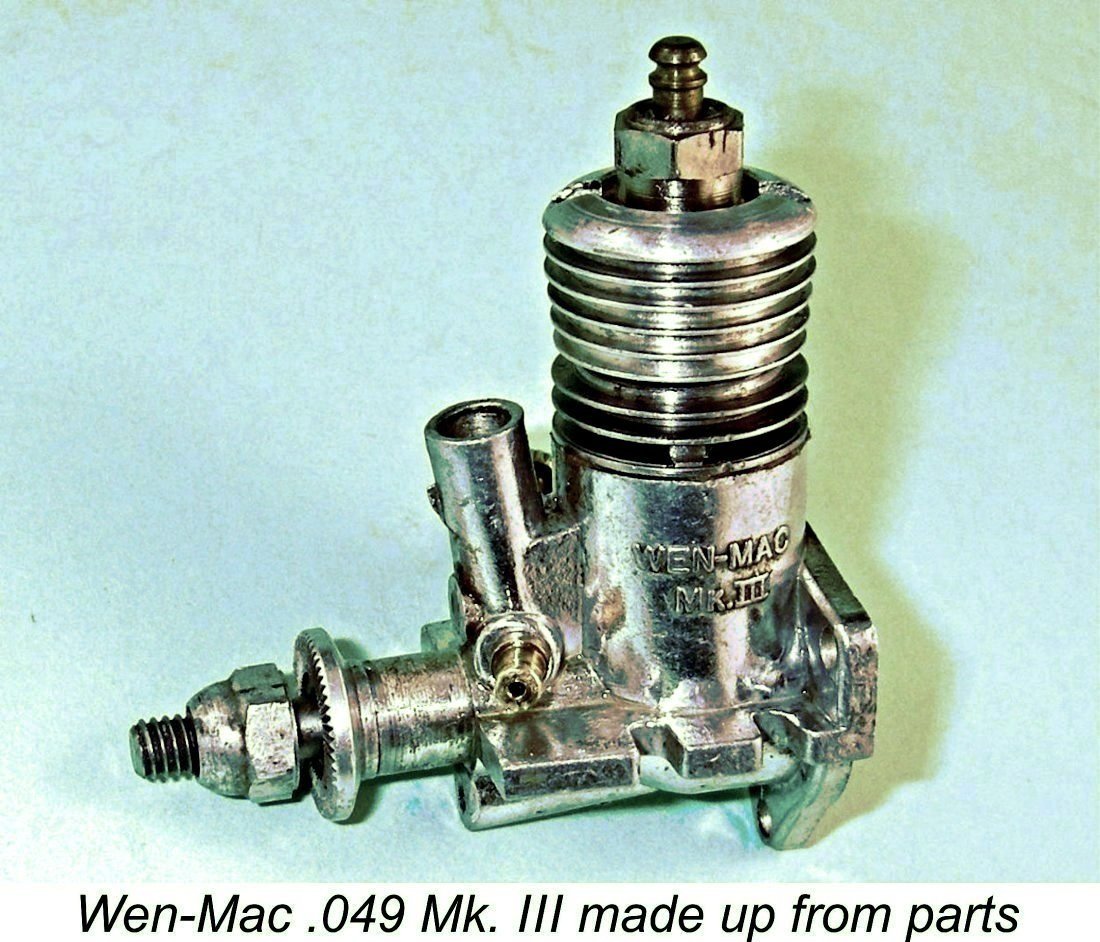

A side-by-side comparison of the A-M .049 with its Wen-Mac counterpart quickly reveals that the A-M version is basically a clone of what Tim Dannels called the 8th model of the Wen-Mac Mk. II engine (Peter Chinn incorrectly described it as a copy of the Wen-Mac Mk. III, which was not introduced by that name until 1961!). In design terms, the Wen-Mac and A-M .049 engines are typical American-style small “sports” glow-plug motors of their day, with pressure die-cast crankcases featuring provision for both radial and beam mounting; screw-in cylinders with reverse-flow scavenging; radial cylinder porting using sawn slots for both transfer and exhaust; crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction; and a ball-and-socket small end on the hardened steel conrod. The Atwood connection is clearly evident, since the cylinder in particular bears an unmistakeable resemblance to that used on earlier Atwood designs such as the 1954 Cadet.

The unhardened leaded steel cylinder (a very "un-British" material) features both exhaust and transfer ports which are formed as The result is that the transfer period is unavoidably restricted even with a relatively early opening of the exhausts. The sole offset to this issue is the fact that the combined area of the transfer ports is very large relative to the engine's displacement. The cylinder screws into the crankcase in the conventional manner. An often-unrecognised downside to this arrangement when used with ports of this type is the fact that the vertical stresses created by the installation thread when tightened are appplied at only three points around the circumference of the cylinder location flange beneath the exhaust ports. In addition, the wedging forces imposed by the cylinder installation threads are unevenly applied to the lower cylinder because of the interruptions of the female threads by the bypass passages. Both of these factors can give rise to distortion of the lower cylinder below exhaust port level. Indeed, such issues are not infrequently encountered with cylinders of this type. The trick is to screw the cylinder into the case only sufficiently tightly to resist any tendency to unscrew during operation. Also make sure that the seating surface on the top of the crankcase is both flat and true.

The three transfer slots are supplied in turn from the annular gallery. This arrangement was similar to that used in the OK Cub engines and was also employed on a far more timid scale in the competing Davies-Charlton Bantam .046 cu. in. model, of which much more in a separate article. The screw-on aluminium alloy cooling jacket also doubles as the cylinder head. It is threaded for a short-reach plug and seals to the cylinder with a gasket. The backplate too is a screw-in item of aluminium alloy which seals with a gasket. The A-M engines were not provided with tanks, although some examples were nonetheless fitted with centrally-tapped backplates suitable for tank mounting. Several variants of the Wen-Mac engine were The piston and conrod are both of hardened steel. The conrod engages with the piston through a ball-and-socket bearing at the upper end, the ball section of the rod being retained in place by a small circlip placed internally around the open end of the socket. The major disadvantage of this arrangement is the fact that a loose connection cannot be re-set. Both engines use a one-piece hardened steel crankshaft with a distinctive conical side profile to the front of the unbalanced full-disc crankweb. Journal diameter is 0.218 in., with a central gas passage of 0.125 in. diameter. Induction is through a round port drilled into the shaft and having a diameter of 0.137 in. This port draws mixture from a downdraft tubular venturi of substantial length. The venturi throat has an internal diameter of 0.177 in. (4.5 mm), while the spraybar is waisted to a diameter of 0.098 in. (2.5 mm) over the length which traverses the venturi throat. Reference to Maris Dislers' invaluable Choke Area Calculator confirms that when applied to an engine of this displacement, this combination will generate adequate suction with consistent operation at all speeds above 13,200 rpm. Based upon published test results, we would expect the engine to be operated at or above this speed for best results, making these dimensions appear reasonable enough, if a little on the "borderline" side. The brass spraybar is internally threaded to accommodate the externally-threaded blued steel needle. The Wen-Mac spraybar is pressed into the venturi and is angled to the rear on the right-hand side, keeping the fingers reasonably well clear of the prop disc. On the A-M, the spraybar is a push-through item which is set at right angles to the engine’s axis and secured with a 6 BA nut. This allows assembly from either side of the engine at the cost of placing the fingers uncomfortably near the prop disc while adjusting the mixture. The A-M needle is tensioned by a piece of plastic fuel tubing which fits over the end of the spraybar and grips an expansion on the needle body. A rather Mickey-Mouse solution, it must be said - a small coil spring as used on the Wen-Mac version would have been far better. In service, the plastic tubing would undoubtedly harden under the action of the fuel, hence requiring regular replacement. The patented Wen-Mac Rotomatic starter which was fitted to both Wen-Mac and A-M models is an extremely ingenious device, if rather physically intrusive and also completely unnecessary given the almost casual ease with which these engines can be hand-started. It consists of two steel housings in the form of shallow “dishes” arranged face to face, the rearmost of which is riveted to the crankcase by a pair of screwed plugs while the other is pressed onto a splined section of the shaft forward of the main journal. This front housing incorporates the prop driver and turns with the prop. These two components contain both a coil “clock” spring and a clutch mechanism to allow for the one-way engagement of that spring.

This steel sleeve in turn engages with a “clutch” device contained in the front (rotating) housing. As supplied, this clutch device is permanently sealed within the front housing, but I took an unserviceable example apart (not a reversible process!) to display its internal features. The Rotomatic clutch works in the same manner as the clutch featured in the earlier pull-cord recoil starter developed by Wen-Mac, which was fully described by Peter Chinn in the “Latest Engine News” feature in the February 1959 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The principle is simple enough. The clutch device includes a stamped centrally-perforated flat steel plate which engages with two opposing flats machined into the front end of the central steel sleeve to which the coil spring is attached. The steel plate and sleeve are thus constrained to turn as one at all times. As previously noted, the sleeve is mounted independently of the shaft, only turning along with the steel plate when the coil spring is activated. The accompanying image shows the sleeve without an attached spring (which was broken as usual - see below!). The steel plate has a pair of wedge-shaped cutaways on its outer edge. Two small steel-plate “rollers” having the same thickness as the steel plate itself are positioned within the front housing in the steel plate’s cutaways as seen in the attached image. The entire assembly is secured in place using a further circular steel “washer” which is permanently swaged into position.

When the prop is released, the spring naturally spins the prop in the direction of engine rotation, with the rollers remaining wedged under the accelerative force generated by the spring. However, the rollers are released as soon as the spring tension is relieved, leaving the front housing and prop free to turn on their own with the steel plate and rollers remaining stationary inside, still attached to the non-rotating steel sleeve. Ingenious!! This setup has the advantage that there’s no fiddling about hooking the end of the starter spring to the prop or to an external cam plate - one just rotates the prop backwards for a turn or so and then releases it. The disadvantages are that it adds a considerable degree of complexity and hence cost as well as a great deal of excess bulk at the front of the engine. It’s also disproportionately heavy, contributing 0.6 ounces (17 gm) to the 1.76 ounce (50 gm) weight of the engine - some 34% of the total. It has the added disadvantage of restricting the length of beam mounts if these are to be used. Finally, the fact that the steel plate and rollers remain stationary within the front housing while the engine is running must inevitably contribute some frictional and viscous drag power losses to the system. Quite apart from all of this, the other really bad thing about this unit is the fact that it invariably failed in service after a relatively short period of use! This was a widely-acknowledged problem at the time - an article about spring starters in the 1960 issue of “Aeromodeller Annual” highlighted this issue. The failure always occurred in the spring itself at the point where it was attached to the central steel sleeve. The only fix was the fitting of a new spring/sleeve combination, which would have been a challenge for many owners given the fact that one had to remove the pressed-on rotating portion of the starter to gain access to the spring. Most people probably didn’t bother because the engines were so easy to hand-start anyway! However, this explains why almost all “experienced” starter-equipped Wen-Mac and A-M .049’s encountered today have broken springs. The A-M .049 on Test

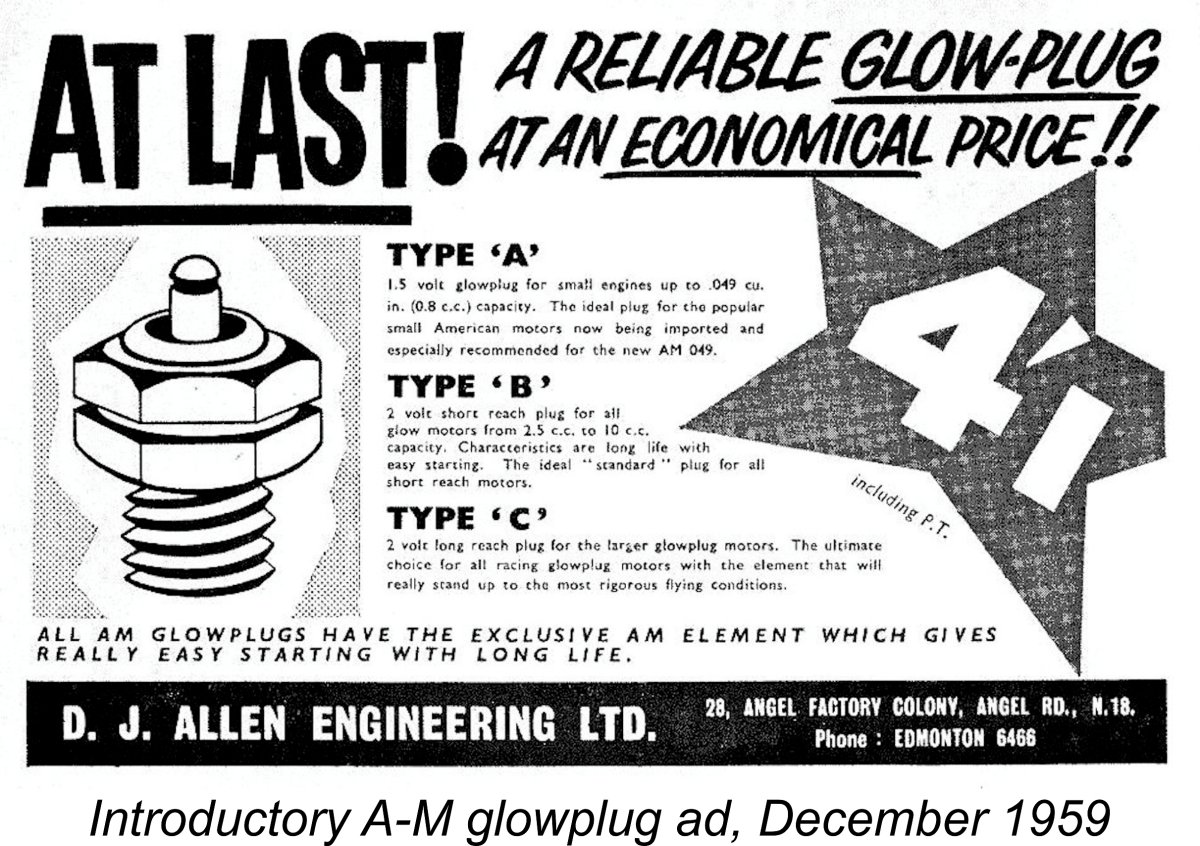

The introduction of the A-M .049 quickly triggered another addition to the business lines pursued by D. J. Allen Engineering Ltd. This was the manufacture of the very compact A-M glow-plugs in competition with the then recently-introduced K.L.G. Miniglow X plugs. As far as I can determine, the A-M plugs were first advertised in December of 1959. The A-M .049 engines were fitted with these plugs as supplied. It seems worth noting at this point that glow-plug manufacture was to remain a primary focus for Dennis Allen for many years thereafter. Although he sold his interest in D. J. Returning to late 1959, the A-M .049 was one of the subjects of an unusual triple engine test by Ron Warring which appeared in the January 1960 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. This test featured three of the four contenders in the British ½A glow-plug sweepstakes. The only one missing was the Cobra .049, the appearance of which was delayed until later in 1960. Warring's very positive test report on the Cobra was finally published in the October 1960 issue of “Aeromodeller”. In his report on the A-M .049, Warring stated that the new engine was “basically the American “Wenmac” motor, with certain material modifications consistent with British practise”. One of my tasks here will be to test this statement. The report also identified D. J. Allen Engineering as the “manufacturers” of the A-M .049 - another point which I’ll subject to close scrutiny.

Warring commented in particular upon the engine’s better-than-average torque development and its consequent ability to turn larger-than-normal props for a glow-plug motor of its displacement. Present-day experience (see below) bears out his comments completely - the A-M is indeed a quite sturdy performer for a 1959 ½A glow-plug engine of its rather utilitarian design. Warring noted that starting was perfectly straightforward without the starter, reinforcing my earlier comment that the starter was quite unnecessary. He did however criticize the engine directly on several points. Firstly, he noted quite correctly that the use of beam mounting was seriously compromised by the protruding radial-mounting flange on the rear of the main casting. The presence of this flange required that the beam mount bearers be notched for clearance. This issue could not be resolved by filing of the case since that would remove part of the backplate sealing surface. Because of this inconvenience as well as that imposed by the presence of the starter, Warring considered that the engine as supplied was set up primarily for radial mounting, not the preferred system in Britain at the time. An issue not mentioned by Warring was that even if radial mounting were to be used, the presence of the starter creates significant difficulties in gaining direct access to the heads of the radial mounting screws - the driver has to be applied at an angle. Basically, the presence of the starter was an impediment to mounting regardless of whether one used the radial or beam approach. In addition, Warring criticised the location of the needle valve control, which he rightly stated to be far too near the airscrew for comfort and safety. He also expressed some justifiable reservations about the use of plastic tubing for tensioning the needle.

A further test of the A-M .049 by Peter Chinn appeared in the April 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Chinn again stated quite clearly that the A-M was “made in England by arrangement with the Wen-Mac Corporation of Los Angeles”. Like Warring before him, Chinn was quite impressed with the engine, although he too criticised the use of plastic tubing to tension the needle valve and also had trouble with the starter, the spring of which failed in the manner described above after only about 100 uses! Despite this problem, Chinn characterized the A-M .049 as “a likeable little engine” and as the most powerful of the three British ½A glow engines tested by him up to that point (the others being the FROG .049 and the D-C Bantam). Using a fuel containing 15% nitro, he obtained a peak output of 0.052 BHP @ 14,300 rpm, a very comparable result to that obtained by Warring in his earlier test. He described the running qualities as “even” and praised both the engine’s ease of handling and its low price. The A-M .049 thus came through its baptism of fire at the hands of the professional testers with (mostly) flying colors and with its British manufacturing origin being staunchly upheld. Let’s now turn our attention to the latter issue. The A-M and Wen-Mac .049’s Compared I noted earlier that the A-M .049 is basically a clone of what Tim Dannels called the 8th model of the Wen-Mac Mk. II engine. This variant featured a long intake venturi and was supplied both with and without the patented Wen-Mac Rotomatic starter. It appeared in 1959, which is consistent with the introductory date for the A-M .049. A later version of the same model appeared in 1960 as the 11th variant of the Mk. II Wen-Mac .049. This had a large “V” cast onto the right side of the case but was otherwise unchanged. It is one of these latter models which is featured in the accompanying illustrations - I don’t have an example of the previous version. The previously-presented images should have reinforced the similarities between the Wen-Mac and A-M models. But what about the differences? Warring hinted at modifications to the material specification to conform to British practise. Where are these changes to be seen? As it happens, direct comparison of multiple examples of both engines in my possession reveals no evidence whatsoever of any departures in material specification between the two models, apart from the use of a small aluminium spinner nut on the A-M in place of the steel hex nut seen on the Wen-Mac! It’s also possible that a different casting alloy was used for the crankcase, but in my book that hardly constitutes a meaningful change - it's still die-cast alloy! Generally speaking, the material specification set out in the description provided earlier applies equally to both units. One is forced to wonder whether Warring had access to an example of the Wen-Mac for comparison purposes or if he was simply taking someone else’s word for it ………….. either way, his claim is unsubstantiated by direct examination. It’s worth noting that the normally meticulous Chinn made no reference to any such differences. So are there any differences?? Well, as it happens, there are a few. Firstly, the A-M’s crankcase casting clearly comes from a modified set of Wen-Mac Mk. II version 8 dies - the basic shape is identical, but the engine’s A-M .049 name is cast in relief onto the crankcase on both sides in place of the Wen-Mac identification. Moreover, the A-M's radial mounting holes are drilled to clear 8 BA screws (2.2 mm O/D), while the Wen-Mac is drilled to clear 3-48 fasteners (2.51 mm O/D). Consequently, the A-M mounting holes will not accommodate 3-48 fasteners, although they are drilled at an identical spacing. A further difference is that the A-M crankcase is left in its as-cast state with crisp, sharp edges, while the Wen-Mac cases appear to have been tumbled to soften the edges and then chemically brightened. The A-M’s finish is far more characteristic of typical British productions than that in evidence on the Wen-Mac cases. As noted earlier, it’s quite possible that a different casting alloy was used.

This is not the only difference in the spraybar arrangements. The spraybar on the Wen-Mac is simply pressed into a hole which is drilled through the aforementioned stubs on the sides of the intake, while the A-M spraybar is of conventional British pattern in that it is a slip fit, being retained by a nut in the familiar manner. The thread is 6 BA, seemingly confirming a British origin for these components at least. Another difference in the form of the castings is to be seen very clearly in the above comparative overhead view of the two engines. The beam mounts on the A-M have outer edges which are parallel to the engine’s axis until the front of the crankcase is reached, at which point they taper sharply inwards to form mounting braces for the starter. By contrast, the beams on the Wen-Mac begin to taper immediately in front of the radial mount flange, thus creating far less substantial beam mounts. The clear implication is that A-M expected that at least some of their customers would actually want to try beam-mounting the engine, hence providing somewhat more substantial bearers. The need to notch the bearers to clear the radial mount flange was still there - the accompanying image below at the right should clarify this difficulty. This flange could not be eliminated by filing at the appropriate locations since that would destroy the backplate seal. However, one could work around this issue when building the model.

But apart from this, the two engines are identical! All components are completely interchangeable, to the extent that an A-M piston is a good fit in a Wen-Mac cylinder, and vice versa - I've confirmed this by direct experiment. Even the externally-threaded needles share the same American 1-72 NF thread. Apart from the minor differences in the crankcase castings, the prop mounting thread, the radial mount hole diameter, the spinner nut and the needle valve arrangements, we’re talking in effect about one and the same engine! So who did make the A-M? Let’s turn our attention to that intriguing issue! Who Made the A-M .049? It’s necessary to begin this discussion by recalling the rationale behind Allen-Mercury’s approach of purchasing the rights to an existing design rather than developing their own model from scratch. The intention must surely have been to sidestep the thorny issues of development and tooling-up costs, thus enabling them to sell the engines at a competitive retail price. Unlike International Model Aircraft (IMA - FROG) and Davies-Charlton (D-C) Ltd., A-M did not have an existing ½A diesel model to convert to glow-plug operation. Therefore, if they did not wish to make the considerable investment necessary to produce their own design from scratch, the only alternative open to them was to purchase a license to produce copies of someone else’s existing design. There was also the issue of manufacturing cost. In order for the A-M .049 to be competitively priced, Allen-Mercury must have known in advance that they would have to keep its selling price below £2 - no easy challenge, and one which would require them to adopt any and all available means to reduce the unit manufacturing cost of each component. The design that they chose incorporated structural features that departed significantly from contemporary British practise, certainly bearing no relationship whatsoever to any of A-M’s previous products. It also incorporated a relatively complex spring starter unlike anything that A-M or any other British manufacturer had ever produced. In order to manufacture this engine in its entirety in his own Edmonton factory, Allen would have had to create or purchase a completely different set of tooling, also employing significantly different manufacturing techniques and material specifications. The new model also required a revised crankcase die for its manufacture. If we were to believe that D. J. Allen Engineering actually manufactured this engine, then we would have to believe that having bought the right to produce the existing Wen-Mac design they then incurred the additional expense of creating a revised crankcase die and then setting up an entirely different production line in terms of tooling, materials and manufacturing techniques. This would surely go a very long way towards defeating the original purpose of the exercise, which was to circumvent development and production challenges along with their associated costs to the extent possible. Speaking personally, I have always found it far easier to believe that Allen-Mercury took full advantage of the fact that Wen-Mac was already making what was essentially the same engine in the tens of thousands in America, doing so by simply contracting with them for the manufacture and supply of some modified dies as well as a small batch (by Wen-Mac standards) of components made to Allen-Mercury’s specifications. Since Wen-Mac already had the dies for the Mk. II version 8 model of the Wen-Mac, it would be very easy for them to make a revised set of dies with the changed identification and the revised beam mount profile and spraybar mounting. Of course, this assumes that the crankcases for the A-M were produced in England using modified dies supplied by Wen-Mac. I believe that this was very likely the way that things went - both the finish on the castings and the casting alloy employed undeniably have a far more “British” character than that of their Wen-Mac cousins. Moreover, the previously-noted fact that the A-M's radial mounting holes are drilled to a smaller diameter than their Wen-Mac counterparts undoubtedly supports the suggestion that the A-M crankcases may have been cast and machined in England. There was no impediment to this once the dies were obtained - A-M are known to have contracted out all of their casting production in any case. In the absence of definite proof, the possibility undeniably remains open that the crankcases were produced by Wen-Mac in America to Allen Engineering’s specifications. But either way, some direct involvement from Wen-Mac has always been clearly implied. Quite apart from that, Wen-Mac were already making the rest of the engine’s components by the truckload each and every day. Hence the addition of a few more destined for the A-M version would be easily accommodated at a minimal unit cost - the economies of scale again! All that was necessary was to make a batch of crankshafts using a 5/32 Whitworth thread in place of the usual 8-32 NC (perhaps using threading dies supplied by A-M) and use standard components everywhere else apart from the spraybar. It’s even possible that standard crankshafts may have been supplied, with Allen Engineering simply chasing the standard 8-32 NC thread with a 5/32 Whitworth die.

The fact that the spraybar mounting thread is a very British 6 BA makes it appear very likely that Allen Engineering arranged for the production of the British-style spraybar with its nut mounting in place of the pressed-in design used by Wen-Mac. In common with a number of other British manufacturers, Allen Engineering seem to have contracted out all of their needle valve manufacturing in any case, making it perfectly straightforward to add this spraybar to the shopping list. The retention of the 1-72 needle thread suggests that the needles were supplied by Wen-Mac, but all that would have been required would be the provision of readily-available 1-72 taps to those making the A-M spraybars. The use of a 6 BA spraybar retention thread would have the advantage of making the replacement of a lost nut far easier for British owners. The 90 degree transverse spraybar alignment would allow owners to locate the needle on either side of the engine as dictated by the application. Moreover, this would allow Allen-Mercury to claim quite truthfully (if challenged on the point) that at least some of the manufacturing took place in England! The required American 1-72 taps could easily have been supplied by Wen-Mac as part of the deal. It’s quite likely that the alloy spinner nuts with their British thread were also made in England either by Allen Engineering or by others under contract - such items were not used by Wen-Mac. In addition, it’s entirely reasonable to suppose that Allen Engineering would have undertaken the final assembly of the engines, albeit from components mostly supplied by Wen-Mac. But to believe that they would start making precision components such as cylinders, cooling jackets, pistons, con-rods, crankshafts, backplates, fuel needles and the like which were already being made by others at unit costs which Allen could never dream of matching is surely straining credibility. It is particularly difficult to accept the notion that Allen Engineering would have wished to tackle the manufacture of the Rotomatic starter. Even Warring in his test report characterized this unit as being “an expensive item to produce”. Its production would require the acquisition of expensive stamping equipment which had no application to any other A-M model. Neither for that matter did the starter itself. When retail price was such a critical factor, why would Allen-Mercury take on the task of manufacturing this somewhat specialized and costly unit when it was already available to them ready-made at a far lower unit cost than they could ever hope to achieve? Thankfully, the invaluable first-hand information supplied by former Allen Engineering employee Mick Clarke following the initial publication of this article on MEN renders it unnecessary to speculate any further on this point. Mick was employed by the firm throughout the entire period of their involvement with the A-M .049. He advised that he paid little attention to the A-M .049 since it didn’t interest him personally and he was fully occupied making the four diesel models which were then still very much in production. Those diesel models were still selling very well at the time, and Mick recalled that their manufacture kept the 6 or 7 machine shop staff who were employed at the time fully occupied. In particular, Mick claimed that he never saw any actual manufacturing of parts for the A-M .049 at the Allen Engineering workshops at any time, nor was any special equipment added to the workshop machine tool inventory - he would have noticed it being installed. He was thus absolutely certain that most if not all of the components were manufactured elsewhere, either in England or in the USA. He was able to confirm that the engines were assembled at Allen Engineering from components supplied by others, but that was as far as it went to his first-hand knowledge. He also supplied the interesting information that the assembled .049 engines were not tested before being sent to the distributor!

It’s hard to feel much surprise at this revelation - the A-M .049 was very much an anomaly in the broad scheme of Allen’s production program, hence almost certainly being seen by Allen more as a source of annoyance than anything else! Accordingly, tooling and staffing up to actually manufacture the .049 from scratch on top of the existing diesel production program would have been both a major inconvenience and a serious financial burden with an uncertain return. Allen would never have taken on such a challenge on his own initiative, and Mick Clarke could recall no indications that he did so. Mick confirmed that the components for the .049 arrived already machined from an external source (or sources), merely being assembled at Allen Engineering. He agreed completely with my original assessment that the majority of components almost certainly came from Wen-Mac in America, although the castings might have been produced and finished in England by others, along with a few other parts. The question might reasonably be asked why they stopped there - surely it would have been even easier to simply contract with Wen-Mac for the production in America of a fully-assembled Anglicized badge-engineered version of the engine? The answer to this question is probably twofold. First, there was doubtless a desire to legitimize the claim that the engines were “Made in England”; at least in part. And second, there may well have been tax and import duty savings arising from the importation from America of “spare parts” rather than complete engines. Although it cannot be proved at this time, all the evidence to date overwhelmingly suggests that in early 1959 Henry J. Nicholls decided on his own account that he wished to participate directly in the upcoming British ½A glow-plug revolution through his involvement with the Allen-Mercury marque. He decided for the reasons set out earlier to approach an American manufacturer to see if he could acquire manufacturing rights to an established design. Under this scenario, Nicholls approached the McRoskey brothers to ask if they would be amenable to having Allen-Mercury market what was in effect their existing Wen-Mac .049 Mk. II Rotomatic design under the A-M label. At the time in question, the slogan “Made in England” still carried considerable clout on the home market, and Nicholls would clearly have been anxious to preserve at least the illusion of this through having the engine identified as a British product. For the reasons noted earlier, Dennis Allen would not have been at all keen on the idea of manufacturing this engine from scratch. However, he was evidently amenable to assisting his long-time business partner by undertaking the assembly work and perhaps arranging for the production of the castings plus a few other components. In fact, he may have wished to have some level of involvement in the actual manufacturing to give the “Made in England” concept some credibility. After all, it was his company’s name that would be associated with the engine. Perhaps the casting and finishing of the crankcases, the production of the spraybars and spinner nuts (either by Allen or by others), the chasing of the crankshaft threads and the final assembly met this need, as suggested earlier. The McRoskeys were evidently receptive to this idea - after all, they had nothing to lose and perhaps much to gain if the engine was a success. In effect, they were being offered the chance to undertake a test penetration of the British market under a different name at someone else’s expense. If their design failed, Allen-Mercury would lose whatever “face” was to be lost and would also absorb any financial losses, rather than Wen-Mac. And if it succeeded, not only would Wen-Mac have made a little money but they would have paved the way towards acceptance of their own products in the British market. There was no way that they could lose!! Given the above arguments, it would have been completely logical for Wen-Mac to agree to make the necessary revisions to a few sets of their existing dies to identify the engine with Allen-Mercury instead of At this point someone may be asking - given that the transverse alignment of the spraybar created the difficulties associated with the extreme proximity of the needle control to the propeller disc as noted quite rightly by Warring, why did Allen-Mercury specify this change? The answer must surely be that they wanted to maximize the engine’s control-line potential. Since ½A control line was then very popular among beginning and school-age fliers (like me at the time!) due to the relatively low cost of participation, Allen-Mercury would obviously have been keen to serve that market. The original Wen-Mac’s use of a spraybar that was pressed in and angled to the right in a rearward orientation meant that the needle couldn’t be switched to the left side for conventional sidewinder mounting in a control line application like that of the illustrated KK Firefly. The change to a right-angled transverse spraybar secured by a nut meant that the needle could be placed on either side of the engine at will. It would also facilitate the replacement of that rather vulnerable component if necessary. Apart from this, the engines would be standard Wen-Mac Mk. II units just like a million others. To me, it has always appeared inconceivable that Allen-Mercury would have deliberately incurred the extra expense of tooling up to make the components for these engines when someone in the USA was already doing so at a unit production cost that no British manufacturer could hope to match. There was never any possibility of Allen Engineering tooling up and manufacturing this engine from scratch at a profit when its selling price was only £1 19s 6d (£1.98) including that expensive starter. And indeed, thanks to Mick Clarke we now know that their involvement was limited to the arrangement of the British production of a few components plus the final assembly of the engines, just as I had supposed. It’s actually just possible, if somewhat unlikely, that the above scenario was initiated by Wen-Mac, who might have approached Allen-Mercury with the same suggestion, the long-term idea being to establish their design on the British market under the cloak of a known and respected British manufacturer. But regardless of who approached whom, all of the evidence points to the A-M .049 being basically a Wen-Mac product, perhaps with a British-made spraybar, prop nut and crankcase! It was evidently assembled in Britain using components predominantly supplied by Wen-Mac, but that was as far as the “British manufacture” went. The End of the Line I hope that I’ve convinced you that the A-M .049 was almost certainly just another Wen-Mac product that was assembled in Britain, with a few components actually being made in England to add some credibility to the “Made in England” claim. Whether or not this is true, it’s beyond debate that the engine was sold under the Allen-Mercury banner as a licensed product of Allen Engineering. I’ve also noted that it appeared on the market in late September 1959 and was the subject of very positive tests by Ron Warring and Peter Chinn. What happened next? Well, simply put, not very much and none of it good! Despite Warring’s and Chinn’s positive comments, too many British modellers noted that awkward and very vulnerable needle valve, the inconvenient arrangements for beam mounting and above all, that very bulky, heavy and unnecessary starter. I was one of them, and I recall my own reaction in exactly those terms. I wasn’t interested, and neither was anyone else……….. Not only that, but the Rotomatic starter quickly proved itself to be the engine’s Achilles’ Heel. Mick Clarke actually recalled that the entire first batch of 50 engines sent out from the factory were returned under guarantee with broken starter springs! A return rate of 100% must surely have few if any precedents within the model engine manufacturing industry! In Mick’s recollection, shipments of the engine in that form ground to a halt fairly quickly thereafter, and he didn’t think that very many more Rotomatic models were made - perhaps only a few hundred in total. This certainly goes far towards explaining the engine’s relative rarity today.

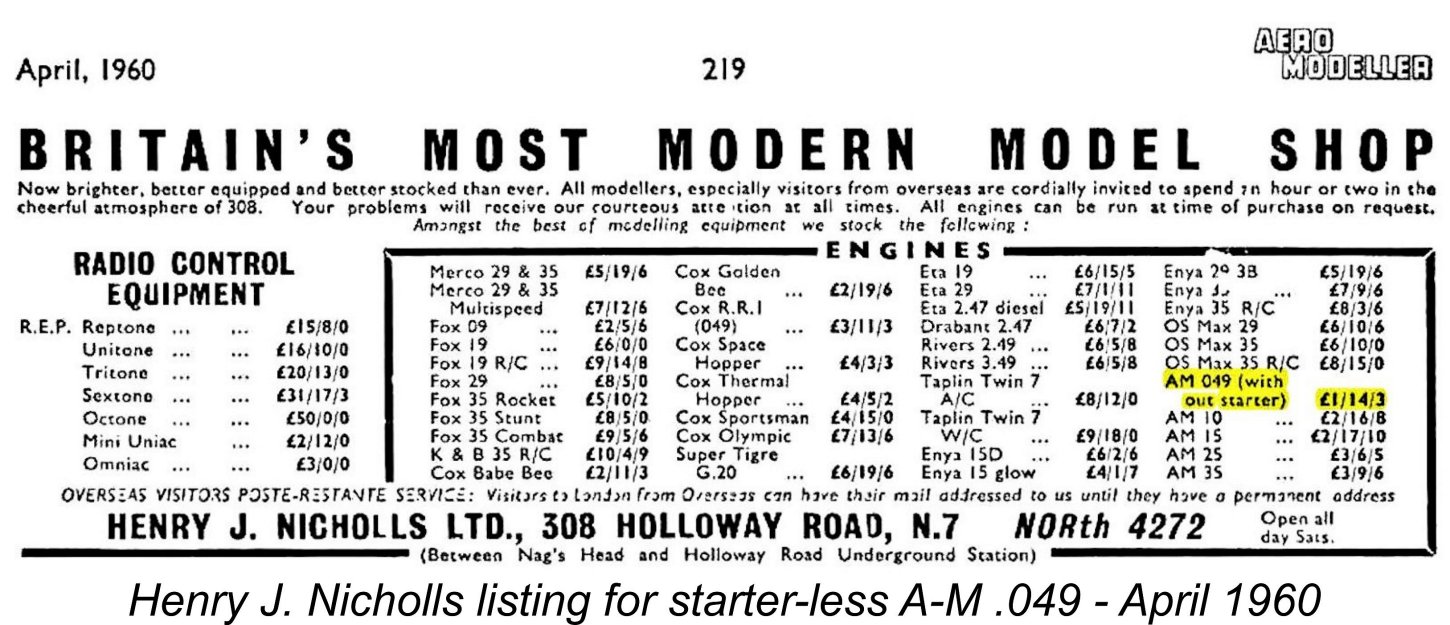

In America, the Wen-Mac hobby versions of the starter-less engines were sold as Wen-Mac Hustlers, but the more or less identical A-M versions were simply offered in Britain as an alternative to the Rotomatic version under the same A-M .049 name. As seen in the advertisement which is reproduced above, these models were being offered for sale by Henry J. Nicholls as early as April 1960, selling for a mere £1 14s 3d (£1.71), thus undercutting the competing D-C Bantam by a princely 7d!! The fact that the engine’s starter-less configuration was specifically highlighted pretty much proves that Nicholls had correctly identified the starter as a major sales impediment, both on account of its weight and bulk and due to its deplorable level of in-service failures. Nicholls had presumably also realized that it was completely unnecessary!

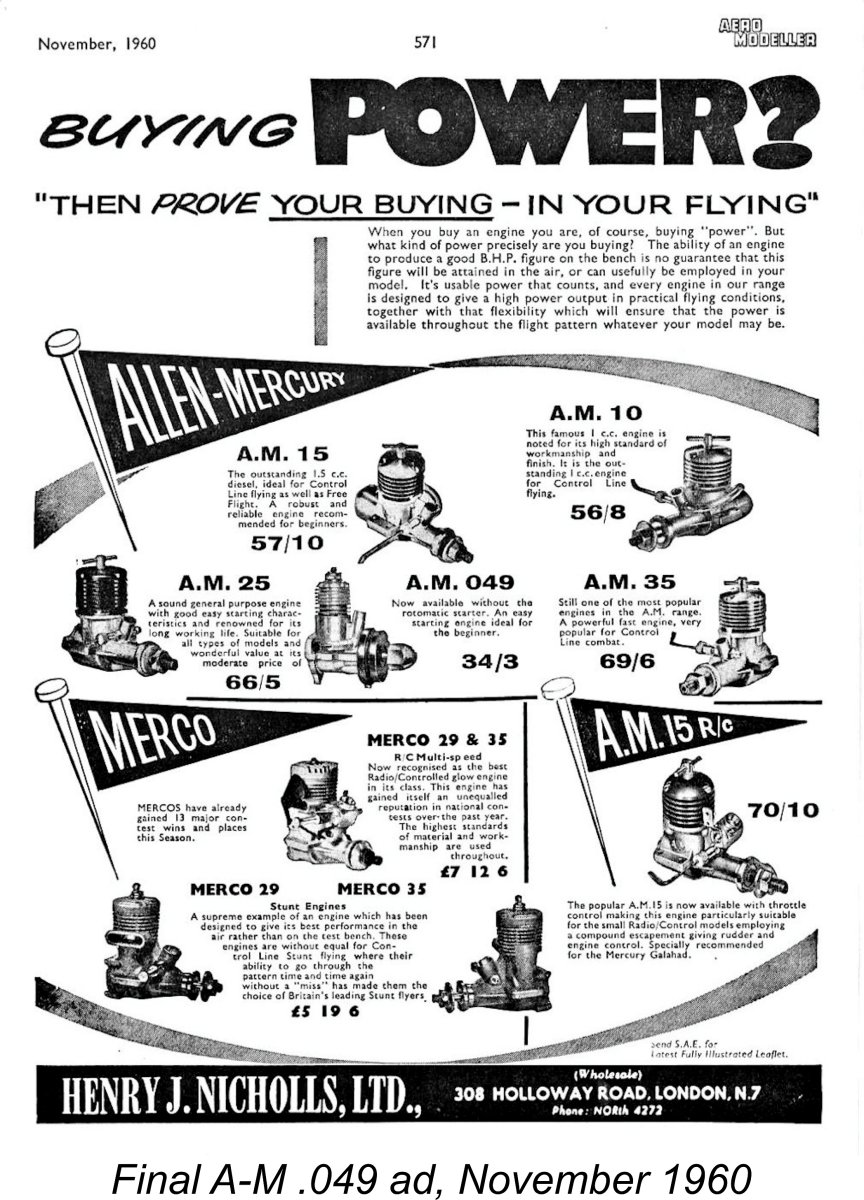

Despite this commendable effort, the damage was done. The A-M .049 found very little success in the British marketplace, being completely overwhelmed by the very successful Davies-Charlton Bantam despite being a vastly superior performer in my own direct experience (see below). It only lasted at most about 15 months on the market, being phased out by the end of 1960. The last Allen-Mercury factory advertisement for the .049 that I can find appeared in November 1960, still highlighting the starter-less variant. Gordon Beeby of Melbourne, Austalia very kindly trolled his Gordon also discovered an interesting piece of information which seems to shed some light upon the final disposition of the residual stocks of the A-M .049. In the report on the 1963 Brighton Trade Show which appeared in the April 1963 issue of "Aeromodeller", mention was made of a new kit model called the Mobo Hovercraft which was unveiled at the show by Jetex manufacturers D. Sebel & Co. This kit was reportedly designed to accommodate "a range of beam or radially-mounted .049 glow engines". Most significantly, the kit was offered at the outset as a package deal at a price of £7 5s (£7.25) complete with A-M .049 powerplant! It would appear that Sebel had bought up the remaining stocks of the engines from Allen Engineering.

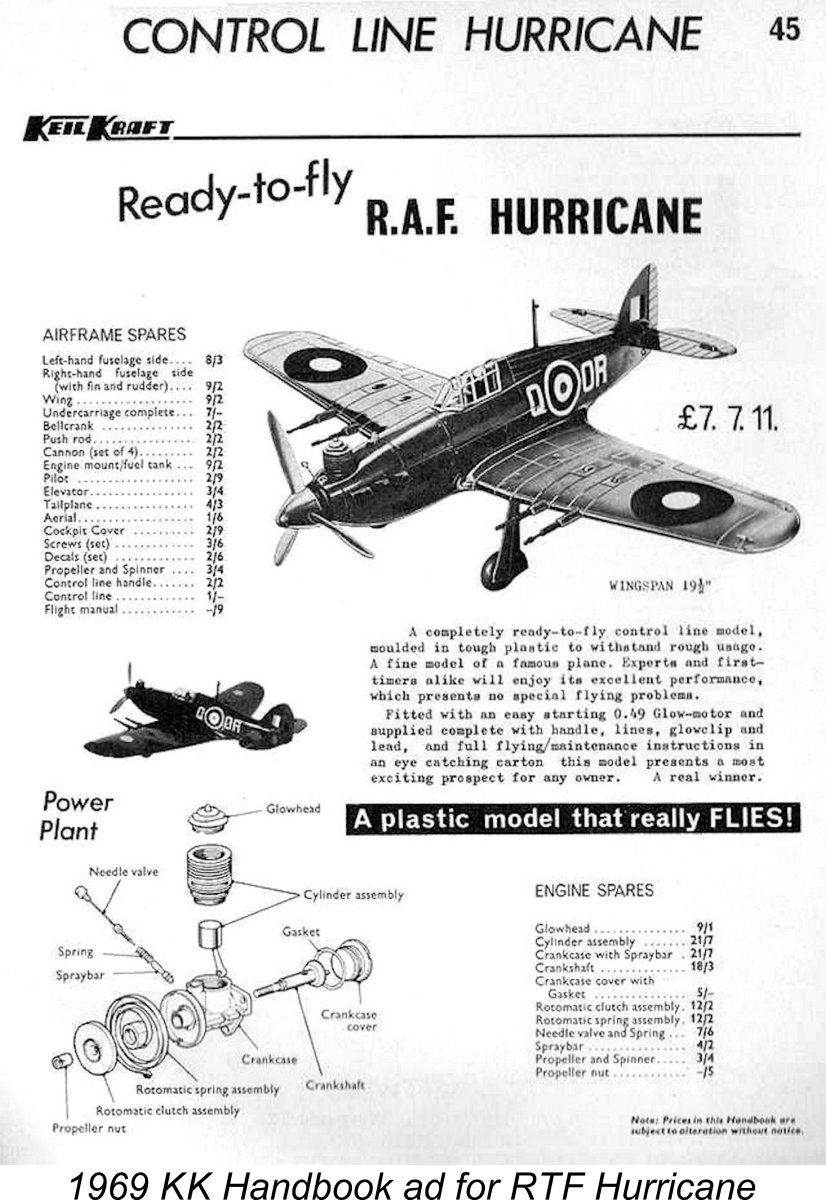

Despite the short market presence of the A-M .049, the “parent” Wen-Mac design did subsequently make a considerable impression on the British market. As of early 1962 the Wen-Mac engines were beginning to appear in British model shops under their own name. The Wen-Mac range gathered further momentum in December 1962 when KeilKraft began importing the Wen-Mac RTF models. These were fitted with American-made examples of the Wen-Mac .049, clearly identified as such. It’s a great pity that the A-M .049 The marketing arrangement between KeilKraft and Wen-Mac was to continue throughout much of the 1960’s. The Wen-Mac .049 and its Testors/McCoy successors were also used to power KeilKraft’s own RTF Hurricane, which lasted well into the 1970’s. So if Wen-Mac had seen the A-M .049 as a vehicle for introducing their product to the British marketplace, it appears that time proved them right, even if Allen-Mercury themselves scarcely benefited! As far as Allen-Mercury were concerned, the failure of the A-M .049 by no means discouraged them from continuing in the glow-plug engine business. On the contrary, they soon expanded their involvement with this type of engine through their taking up the manufacture of the MERCO glow-plug engines in mid 1961. At that time, Dennis Allen remained very much involved with the company, but this changed in 1963 when Allen sold his interest in the business. With the continuing involvement of MERCO’s Ron Checksfield, the company and its successors carried on making the MERCO range as well as revised versions of a number of the established A-M diesels. I’ve related that story in a separate article to be found on this website. Although the Angel Factory Colony no longer exists as such, Mick Clarke reported that the premises in which the A-M and MERCO engines were manufactured were still in existence as of 2011, albeit used for other purposes by that time. Mick also passed on another interesting piece of trivia to the effect that A-M and MERCO were not the only model engine ranges to be manufactured on these premises - apparently the production of components for the far later Kingcat range also took place there, at least for a time. But that’s another story………. A Latter-Day Test After all that I’ve said above about the A-M .049, both good and bad, it seems only fair that I should allow the poor little engine an opportunity to speak for itself! The best way to accomplish this would clearly be to put one into the test stand and see how it stacked up by present-day comparison with other small contemporary British glow-plug units.

As with the other British .049 models which I’ve tested previously, I used a fuel containing 15% nitro and 25% castor oil. Many British ½A fliers of the day (including myself) used KeilKraft Nitrex 15 in their small glow-plug motors, having found that the improved performance fully justified the extra cost of this fuel. Most contemporary users of the A-M .049 would likely have used such a fuel in their engines. My use of a castor-based fuel with plenty of oil was inspired by my awareness of the fact that motors like these having ball-and-socket conrod connections require at least 20% castor oil in the fuel. Joints of this type give rise to extremely elevated unit working pressures between the ball and socket along with relatively high temperatures given the socket's direct connection with the centre of the piston crown. Synthetic oils are far less effective than castor oil in resisting this combination. Indeed, back in the ball-and-socket days the warranties on Cox engines were specifically invalidated if the fuel used was not primarily castor-based. Leroy Cox understood this issue perfectly! After some experimentation, I elected to make up a radial mount rather than try to use the beam mounts for the purposes of this test. The installation of the engine in a conventional test stand was found to create significant difficulties with access to the needle valve. This was due to the fact that the presence of the radial mount flange above the beam mounting lugs prevented the engine from being positioned far enough forward to eliminate interference between the needle and the stand. I decided that avoidance of this problem was the best course of action. The required radial mount was easily created from a piece of extruded high-strength aluminium alloy T-section bar stock.

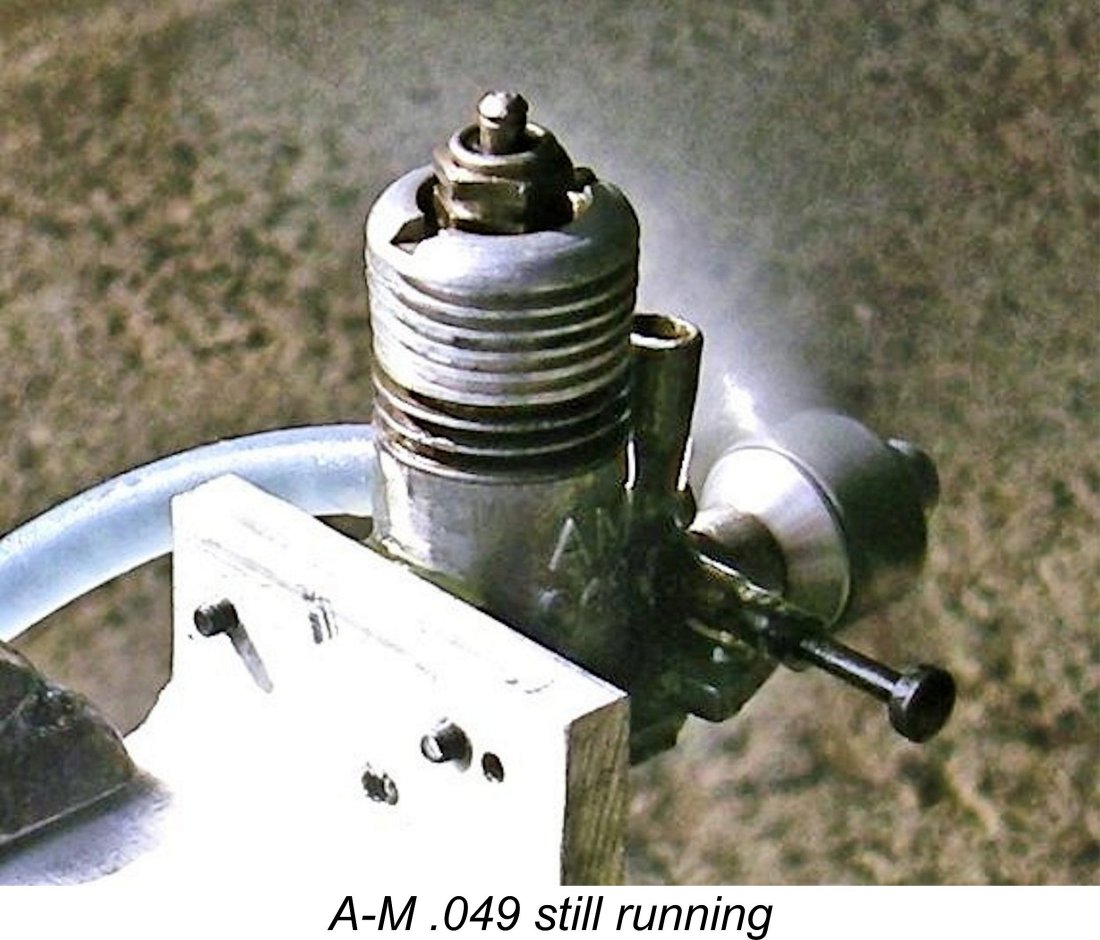

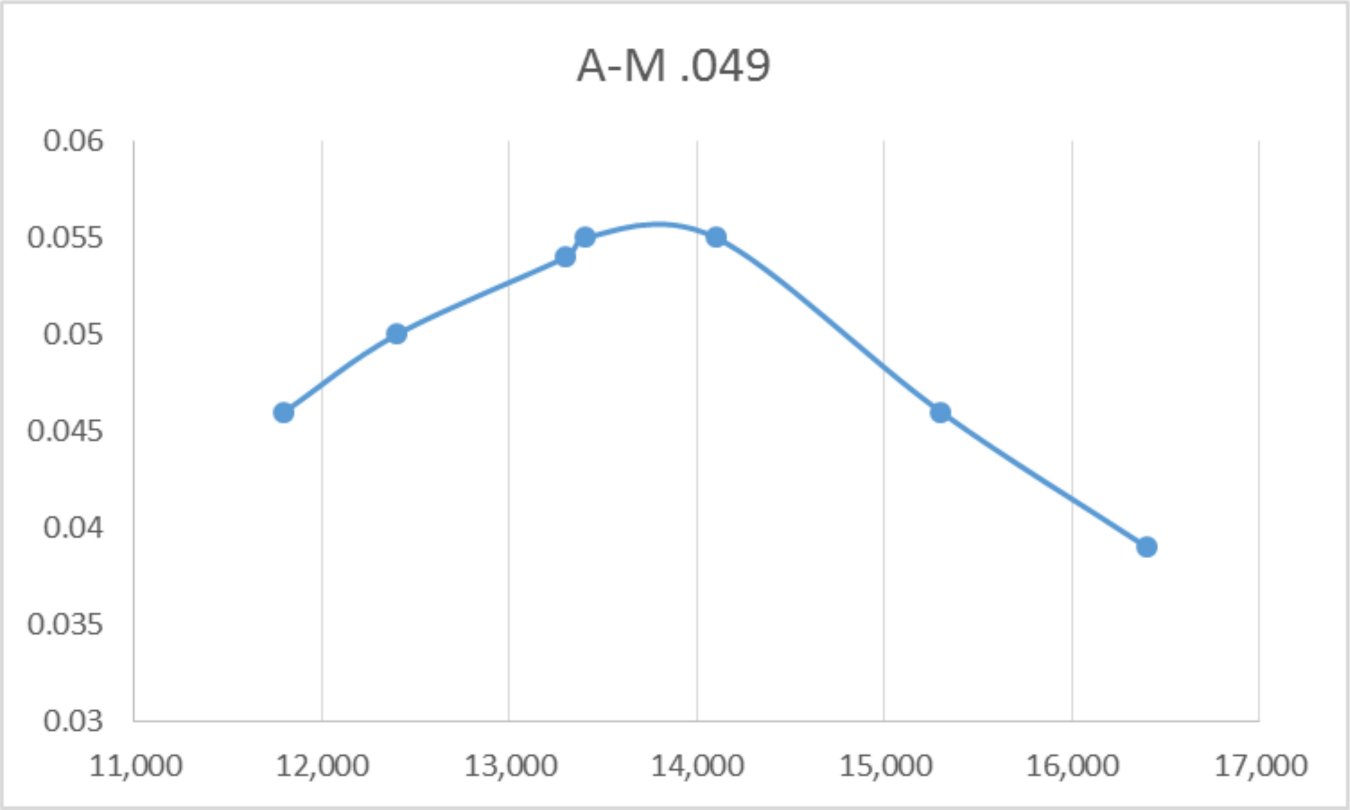

Once running, the proximity of the needle valve to the prop disc became very apparent. It was necessary to exercise great care in making adjustments if skinned fingers were to be avoided. The one saving grace was the fact that the needle operated very smoothly and held its settings very dependably at all speeds. Indeed, the engine needled very well, making the establishment of an optimum setting for each prop very straightforward. Suction appeared to be more than adequate over the tested range of speeds. Running was absolutely smooth and consistent throughout the test. The A-M seemed to be very happy at all tested speeds, displaying no problematic behavior of any kind. It delivered quite a sprightly performance, as witness the following data.

As can be seen, the little A-M was found to develop around 0.056 BHP @ 13,800 rpm on the 15% nitro fuel used in this test. These results correspond quite well with the previously-cited performance figures reported by both Ron Warring and Peter Chinn using a similar proportion of nitro. It's interesting to note that my starterless unit did in fact develop slightly more power than the starter-equipped examples tested by my two predecessors. There's little doubt in my mind that the drag imposed by the starter during operation would rob the engine of some power.

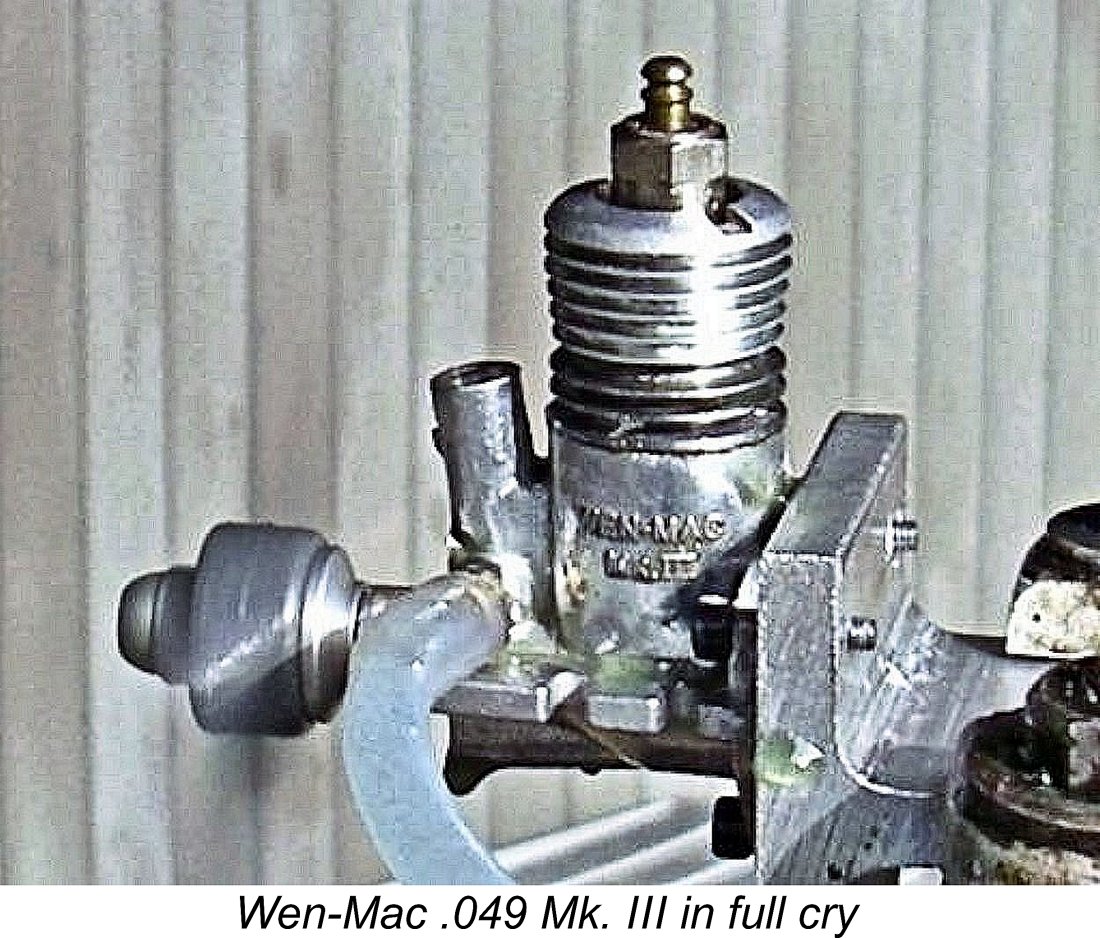

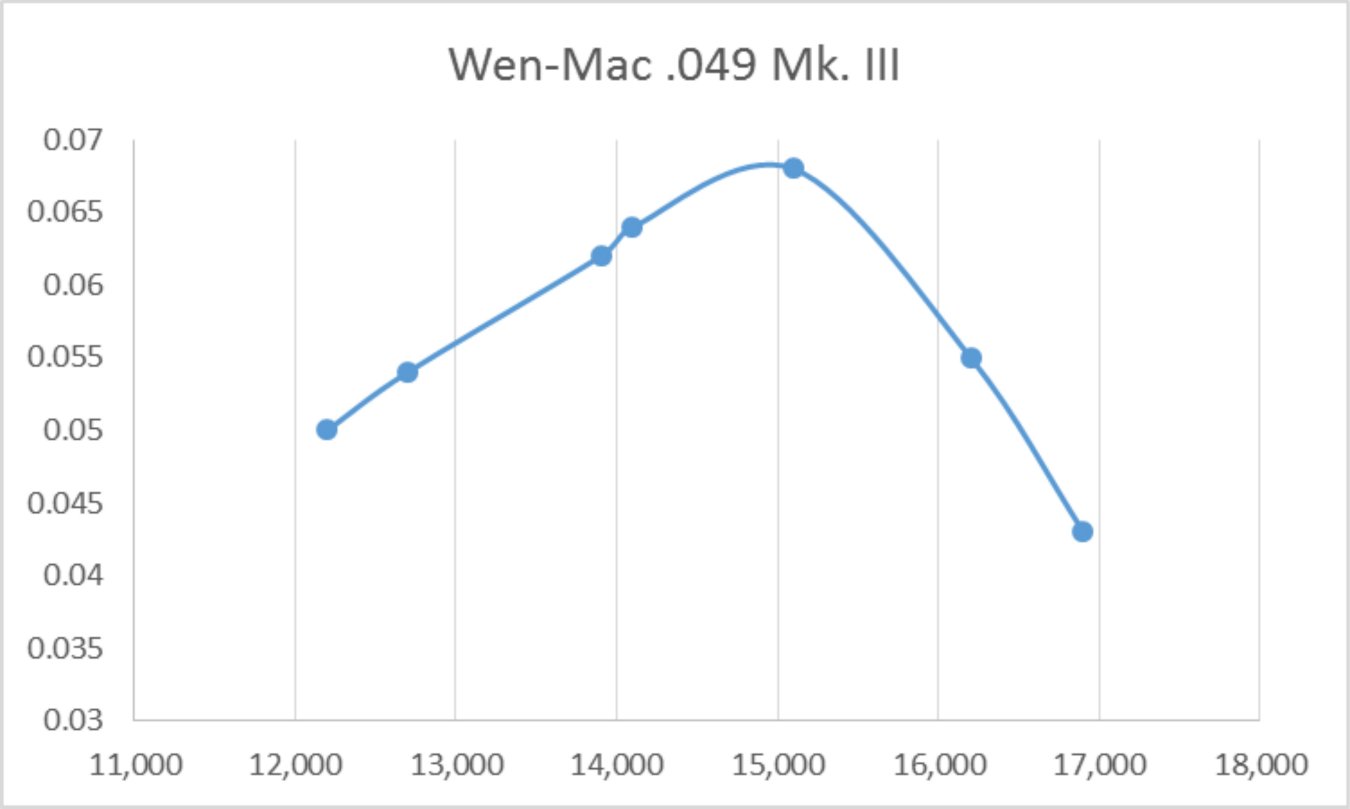

Just for a bit of fun (we all need more of that these days!), I ransacked my ½A parts stash and came up with enough original Wen-Mac components in good condition to make up a very nice complete Mk. III example of that engine in first class operating condition. The reconstituted unit has no starter, hence being more or less in Hustler mode, which is fine with me - that's how it should have been released in the first place! I thought that it would be fun to see how this Wen-Mac example stacked up against the A-M rendition. Since neither was handicapped by the operating drag of the The engine may have been created from a set of previously disassociated parts, but that didnt stop it from performing at a more than acceptable level. It started and ran just as well as its A-M counterpart. As before, a healthy prime was required, but once that was given the engine was a consistent one or two flick starter. The angled-back needle valve was much appreciated for keeping the fingers well away from the prop disc, while the coil spring needle tensioning arrangement is both effective and clearly far more durable than the plastic tubing used on the A-M. The Wen-Mac needled every bit as well as its competitor, also running absolutely smoothly at all speeds tested with no signs of distress at any time. As expected, the Wen-Mac Mk. III outperformed its A-M rival by some margin using the same fuel containing 15% nitro. The following data tell the story.

The above figures show that the Wen-Mac Mk. III developed around 0.069 BHP @ 14,900 rpm. I'd put the additional output down to the larger bypass passages incorporated into the Mk. III crankcase. The test engine also had a piston/cylinder fit which was pretty much perfect. I must admit to having been very impressed with my "bitsa" Wen-Mac! Both the A-M original and the "parts drawer" Wen-Mac came through their quite arduous test sessions with flying colours. Neither engine showed any evidence of mechanical distress at any time either during the test or upon post-test inspection. The glow-plugs in both engines also survived the testing in good working order. Overall, a very satisfactory test session! Summary and Conclusion

As recorded by both contemporary testers of their day, these little engines are actually very respectable performers if you can just ignore that dratted Rotomatic starter! Better yet, try one of the later starter-less versions. If it had been offered from the outset in that form, the engine might well have fared a lot better in the marketplace than it did. In performance terms it was certainly head and shoulders above the competing ½A glow-plug models from FROG and D-C- Ltd. Among its British ½A glow-plug competitors, only a good example of the later Cobra .049 of August 1960 could give it a run for its money. So keep your eyes peeled and you may come up with an example of one of the less successful and now largely forgotten products of the British model engine industry. And perhaps one that is unique in not being a British product at all!! Just be aware that if you do find one, it will probably have a broken spring inside that dratted Rotomatic starter!! Even so, you'll find it to be a surprisingly useful performer! _______________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN March 2011 This revised edition published here June 2021 |

||

| |

In my companion article on the

In my companion article on the  The

The

By 1959, when the A-M .049 story begins, the Wen-Mac .049 had appeared in no fewer than 12 distinct variants. The three earliest models were all simply designated as Wen-Mac .049’s, but in 1955 a further modified variant appeared which was designated the Mk. II Wen-Mac .049. As of 1959 this Mk. II version had progressed through no fewer than 9 distinct variants of its own, all identified on the case as Mk. II’s.

By 1959, when the A-M .049 story begins, the Wen-Mac .049 had appeared in no fewer than 12 distinct variants. The three earliest models were all simply designated as Wen-Mac .049’s, but in 1955 a further modified variant appeared which was designated the Mk. II Wen-Mac .049. As of 1959 this Mk. II version had progressed through no fewer than 9 distinct variants of its own, all identified on the case as Mk. II’s.  The Wen-Mac company continued to manufacture RTF models and engines in its own right until 1968, in which year it was acquired by the Testor Corporation, the owners of the McCoy trade name. Testors continued production of updated versions of the Wen-Mac engines under the

The Wen-Mac company continued to manufacture RTF models and engines in its own right until 1968, in which year it was acquired by the Testor Corporation, the owners of the McCoy trade name. Testors continued production of updated versions of the Wen-Mac engines under the  Glow-plug ignition was accepted in Britain as being superior only in the larger displacements (over 3.5 cc) and for specialized purposes such as all-out speed competition and Class B team racing. This had allowed the British-made

Glow-plug ignition was accepted in Britain as being superior only in the larger displacements (over 3.5 cc) and for specialized purposes such as all-out speed competition and Class B team racing. This had allowed the British-made  The early 1959 introduction of the excellent

The early 1959 introduction of the excellent  In the smaller displacement categories, the importation to Britain of the

In the smaller displacement categories, the importation to Britain of the  Now there were three potential pathways to entry into this market - innovate, convert or copy. The first option involved the development of an all-new design from scratch - an expensive proposition, albeit the approach with perhaps the greatest potential.

Now there were three potential pathways to entry into this market - innovate, convert or copy. The first option involved the development of an all-new design from scratch - an expensive proposition, albeit the approach with perhaps the greatest potential.

going back to his days as the head of Henry J. Nicholls’ engine repair service in the late 1940’s. He had subsequently worked for

going back to his days as the head of Henry J. Nicholls’ engine repair service in the late 1940’s. He had subsequently worked for  I may as well start right out by saying that the A-M and Wen-Mac .049 models are very similar indeed. Except where specifically noted, the following description applies equally to both models.

I may as well start right out by saying that the A-M and Wen-Mac .049 models are very similar indeed. Except where specifically noted, the following description applies equally to both models.  Quoted bore and stroke of the Wen-Mac are 0.420 in. (10.67 mm) and 0.360 in. (9.14 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.817 cc (O.0499 cuin.). This is just within the American ½A class displacement limit of 0.050 cuin. Ron Warring published supposedly measured figures for the A-M .049 of 0.421 in. (10.69 mm) and 0.364 in. (9.24 mm) respectively for a very slightly larger displacement of 0.829 cc (0.506 cuin.) which is just over the US ½A limit. However, the discrepancies are small enough that they may be merely incidental or may relate to the measuring techniques used. In practical terms, my own hands-on experiments have proved that major working components from the two engines are both indistinguishable and directly interchangeable.

Quoted bore and stroke of the Wen-Mac are 0.420 in. (10.67 mm) and 0.360 in. (9.14 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.817 cc (O.0499 cuin.). This is just within the American ½A class displacement limit of 0.050 cuin. Ron Warring published supposedly measured figures for the A-M .049 of 0.421 in. (10.69 mm) and 0.364 in. (9.24 mm) respectively for a very slightly larger displacement of 0.829 cc (0.506 cuin.) which is just over the US ½A limit. However, the discrepancies are small enough that they may be merely incidental or may relate to the measuring techniques used. In practical terms, my own hands-on experiments have proved that major working components from the two engines are both indistinguishable and directly interchangeable.

The coil spring is contained in the rearmost steel housing. Its outer end is hooked onto the lip of the stationary housing, while the inner end is attached to a tubular steel sleeve mounted on a suitably machined portion of the front of the main bearing housing, thus being left free to rotate independently of the crankshaft. It should be clear that rotating the steel sleeve on its bearing will wind the attached coil spring.

The coil spring is contained in the rearmost steel housing. Its outer end is hooked onto the lip of the stationary housing, while the inner end is attached to a tubular steel sleeve mounted on a suitably machined portion of the front of the main bearing housing, thus being left free to rotate independently of the crankshaft. It should be clear that rotating the steel sleeve on its bearing will wind the attached coil spring. When the prop is wound backwards (to the left in the earlier image, which shows the assembly from the rear), the rollers become wedged between the steel plate and the lip of the rotating housing so that the steel plate and the central sleeve with its attached spring are constrained to move with the housing, thus winding the spring as the prop is turned backwards.

When the prop is wound backwards (to the left in the earlier image, which shows the assembly from the rear), the rollers become wedged between the steel plate and the lip of the rotating housing so that the steel plate and the central sleeve with its attached spring are constrained to move with the housing, thus winding the spring as the prop is turned backwards.  The A-M .049 was announced somewhat prematurely in a full-page advertisement from Henry J. Nicholls which appeared in the July 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller”. The ad stated that the engine would be available “soon”. In the event, "soon" turned out to be three months! It was late September before examples actually began to appear in the model shops, at which time the engine also began to be featured in Allen-Mercury’s regular advertising. It sold for a most competitive price of £1 19s 6d (£1.98), although this was soon to be undercut by the D-C Bantam at only £1 14s 10d (£1.74).

The A-M .049 was announced somewhat prematurely in a full-page advertisement from Henry J. Nicholls which appeared in the July 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller”. The ad stated that the engine would be available “soon”. In the event, "soon" turned out to be three months! It was late September before examples actually began to appear in the model shops, at which time the engine also began to be featured in Allen-Mercury’s regular advertising. It sold for a most competitive price of £1 19s 6d (£1.98), although this was soon to be undercut by the D-C Bantam at only £1 14s 10d (£1.74).

Warring was very complimentary about the engine’s handling and performance, finding a peak power output of 0.052 BHP @ 14,000 rpm, a very good figure for a sports glow-plug .049 in 1959 and one which matched or exceeded the performance of several contemporary small diesels of generally similar displacement and weight. When one considers that the engine weighs only 1.16 ounces (33 gm) without the starter, the reported power-to-weight ratio is actually pretty impressive. The fuel used to obtain these figures contained 15% nitromethane - a fairly typical ½A fuel in Britain at the time, where KeilKraft Nitrex 15 was a favoured fuel for these little engines.

Warring was very complimentary about the engine’s handling and performance, finding a peak power output of 0.052 BHP @ 14,000 rpm, a very good figure for a sports glow-plug .049 in 1959 and one which matched or exceeded the performance of several contemporary small diesels of generally similar displacement and weight. When one considers that the engine weighs only 1.16 ounces (33 gm) without the starter, the reported power-to-weight ratio is actually pretty impressive. The fuel used to obtain these figures contained 15% nitromethane - a fairly typical ½A fuel in Britain at the time, where KeilKraft Nitrex 15 was a favoured fuel for these little engines.

In terms of the casting itself, the installation stubs cast onto the sides of the intake venturi for the spraybar are differently oriented - as mentioned earlier, the Wen-Mac spraybar is angled back to the right (looking forward in the direction of flight), while the A-M spraybar is set at right angles to the engine’s axis. This orientation on the A-M is actually a retrograde step in one respect because it is this feature which brings the needle valve control so perilously close to the propeller disc.

In terms of the casting itself, the installation stubs cast onto the sides of the intake venturi for the spraybar are differently oriented - as mentioned earlier, the Wen-Mac spraybar is angled back to the right (looking forward in the direction of flight), while the A-M spraybar is set at right angles to the engine’s axis. This orientation on the A-M is actually a retrograde step in one respect because it is this feature which brings the needle valve control so perilously close to the propeller disc.  The only other difference that I can find is that the prop mounting thread on the A-M is

The only other difference that I can find is that the prop mounting thread on the A-M is One piece of direct evidence strongly supporting this notion is the previously-mentioned fact that some examples of the A-M .049 have backplates which are centrally tapped to accommodate a back tank, even though such tanks were never fitted to the A-M as supplied or even offered as an optional accessory. This is easily explained if the backplates were simply taken from Wen-Mac stock in America, since Wen-Mac did produce a number of variants of the Wen-Mac .049 which were fitted with back tanks. Conversely, there was no reason at all for Allen Engineering to manufacture such backplates since they never offered tanks for these engines at any time.

One piece of direct evidence strongly supporting this notion is the previously-mentioned fact that some examples of the A-M .049 have backplates which are centrally tapped to accommodate a back tank, even though such tanks were never fitted to the A-M as supplied or even offered as an optional accessory. This is easily explained if the backplates were simply taken from Wen-Mac stock in America, since Wen-Mac did produce a number of variants of the Wen-Mac .049 which were fitted with back tanks. Conversely, there was no reason at all for Allen Engineering to manufacture such backplates since they never offered tanks for these engines at any time.  Mick also believed from his personal interactions at the time that the A-M .049 did not owe its existence to any initiative on the part of Dennis Allen, but was in fact the result of negotiations between Allen’s long-time partner Henry J. Nicholls of Mercury fame and the Wen-Mac Corporation. Allen’s role was evidently confined to making arrangements for a few components to be manufactured in England as well as undertaking the final assembly of the engines in accordance with the deal negotiated between Nicholls and Wen-Mac.

Mick also believed from his personal interactions at the time that the A-M .049 did not owe its existence to any initiative on the part of Dennis Allen, but was in fact the result of negotiations between Allen’s long-time partner Henry J. Nicholls of Mercury fame and the Wen-Mac Corporation. Allen’s role was evidently confined to making arrangements for a few components to be manufactured in England as well as undertaking the final assembly of the engines in accordance with the deal negotiated between Nicholls and Wen-Mac.

Wen-Mac and also to make certain other minor modifications in accordance with Allen-Mercury’s specifications. These included the use of a British prop mounting thread, the extension of the mounting beams and the transverse alignment of the spraybar, which would be used in conjunction with a conventional nut fixture for the spraybar.

Wen-Mac and also to make certain other minor modifications in accordance with Allen-Mercury’s specifications. These included the use of a British prop mounting thread, the extension of the mounting beams and the transverse alignment of the spraybar, which would be used in conjunction with a conventional nut fixture for the spraybar.  To their credit, Allen-Mercury doubtless heard the criticisms and tried to deal with the starter issue at least. They quickly came up with a batch of engines that were not fitted with the Rotomatic starter. Interestingly, these were not converted from previously-manufactured Rotomatic models - there was no provision for the mounting of a starter, nor was the case machined to provide a bearing for the starter sleeve. The starter-less units were clearly produced in a separate series.

To their credit, Allen-Mercury doubtless heard the criticisms and tried to deal with the starter issue at least. They quickly came up with a batch of engines that were not fitted with the Rotomatic starter. Interestingly, these were not converted from previously-manufactured Rotomatic models - there was no provision for the mounting of a starter, nor was the case machined to provide a bearing for the starter sleeve. The starter-less units were clearly produced in a separate series.  This actually makes this version of the A-M .049 the cheapest ready-to-run model engine ever offered to the British public by a British manufacturer. Ironically, the only lower-priced engine ever offered to the British public by any manufacturer was the basically identical American-made starter-less Hustler version of the Wen-Mac .049, which was offered briefly during the early 1960’s at a price of only £1 9s 6d (£1.48). These starter-less units were far more useable engines than the Rotomatic models, being both lighter at only 1.16 ounces and far more amenable to either beam or radial mounting due to the absence of the starter.

This actually makes this version of the A-M .049 the cheapest ready-to-run model engine ever offered to the British public by a British manufacturer. Ironically, the only lower-priced engine ever offered to the British public by any manufacturer was the basically identical American-made starter-less Hustler version of the Wen-Mac .049, which was offered briefly during the early 1960’s at a price of only £1 9s 6d (£1.48). These starter-less units were far more useable engines than the Rotomatic models, being both lighter at only 1.16 ounces and far more amenable to either beam or radial mounting due to the absence of the starter.

The Mobo Hovercraft was advertised in the May and June 1963 issues of "Aeromodeller" but seems to have faded away thereafter - evidently it was not a sales success. Most interestingly, the three engines listed in the advertisements as being suitable were the A-M .049, the

The Mobo Hovercraft was advertised in the May and June 1963 issues of "Aeromodeller" but seems to have faded away thereafter - evidently it was not a sales success. Most interestingly, the three engines listed in the advertisements as being suitable were the A-M .049, the

For the purposes of this test I elected to use the later starter-less variant of the engine. For one thing, it was easier to mount given the absence of the completely unnecessary Rotomatic starter. For another, I was convinced that the inevitable friction and viscous drag generated by the starter during operation would have some degree of adverse impact upon the measured performance. The starter-less version was free from any such handicap, allowing the engine to deliver its best-possible performance. I considered it quite likely that the starter-less engine would exceed the performance figures reported by Warring and Chinn.

For the purposes of this test I elected to use the later starter-less variant of the engine. For one thing, it was easier to mount given the absence of the completely unnecessary Rotomatic starter. For another, I was convinced that the inevitable friction and viscous drag generated by the starter during operation would have some degree of adverse impact upon the measured performance. The starter-less version was free from any such handicap, allowing the engine to deliver its best-possible performance. I considered it quite likely that the starter-less engine would exceed the performance figures reported by Warring and Chinn.  As usual when testing a classic .049 glow-plug motor, I began with an APC 6x3 prop. The engine showed itself to be an instant starter provided a fairly healthy prime was administered. Throughout the test, it invariably started on the first or second flick following a prime. The complete absence of any requirement for a starter of any kind was more than amply demonstrated. If you couldn't hand-start this one, you should probably find a different activity - model engines are not for you ..........!

As usual when testing a classic .049 glow-plug motor, I began with an APC 6x3 prop. The engine showed itself to be an instant starter provided a fairly healthy prime was administered. Throughout the test, it invariably started on the first or second flick following a prime. The complete absence of any requirement for a starter of any kind was more than amply demonstrated. If you couldn't hand-start this one, you should probably find a different activity - model engines are not for you ..........!

starter, the comparison would be fair. The Mk. III crankcase has somewhat larger bypass passages, creating an expectation that it might out-perform its A-M rival. Still, only one way to find out for sure..................

starter, the comparison would be fair. The Mk. III crankcase has somewhat larger bypass passages, creating an expectation that it might out-perform its A-M rival. Still, only one way to find out for sure..................

As a result of its rather lacklustre sales history, the A-M .049 is actually among the rarer small British model