|

|

The Classic Taifun Engines

The Taifun model series was instigated by the long-established Johannes Graupner company of Kirchheim unter Teck, a town of modest size located in Baden-Württemberg some 35 km south-east of Stuttgart, West Germany. Founded in Stuttgart in 1930, this company was to go on to become the world's largest manufacturer and distributor of model kits, model engines, R/C equipment and related paraphernalia, for a time at least.

In tackling this task, I have to admit right up front that I’m Friesenegger’s book is another excellent source of information, albeit in German. There's also a fair amount of information to be found in the German-language "Blue Book" by Matthäus Weidner, which was published by the Deutsches Museum. Even so, I’m certain that there will be errors and omissions in what follows. I’ll also be confining my comments to those commercial products of the Graupner/Taifun collaboration which actually achieved market status. I’m aware of a number of prototype models such as the boxer twins, but have no information on them, nor do they really belong in an account of the companies’ commercial activities. Finally, I must apologise in advance for the poor quaity of some of the images with which this article is illustrated. My personal Taifun collection is very far from complete, forcing me to scrounge images wherever they can be found. In my opinion, even a poor-quality image is better than none at all! If better images come to hand in the future, I'll substitute them. With those caveats in mind, here’s the Taifun story as best I’m able to present it on the basis of my current information. Graupner – the Early Years

The Johannes Graupner company was successful right from the start, soon relocating in 1932 to larger premises in Kirchheim unter Teck, some 35 km to the south-east of Stuttgart, where it was to remain for the rest of its existence. The company continued to prosper, allowing it to initiate its attendance at trade fairs in 1934.

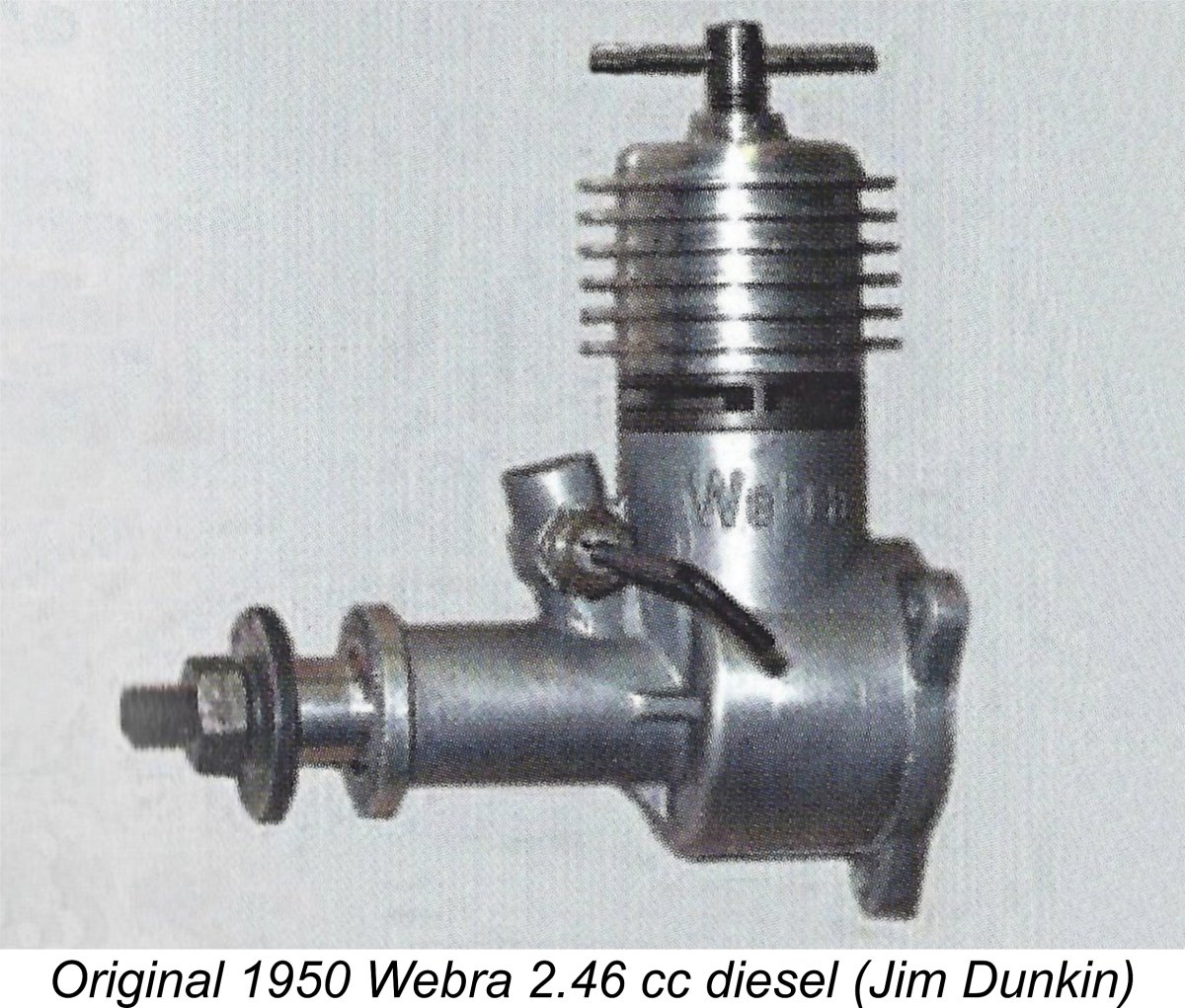

After the sorry interlude of World War II, Johannes Graupner filed successfully for permits to reopen the firm. The first products offered after the re-opening were eighteen different toys as well as craft plans and kitchen utensils. In 1950, plans and accessories for model aircraft were offered for sale, along with model train accessories such as scale buildings and landscape materials. Johannes Graupner followed emerging trends in the model and craft business very closely. He became keenly aware of the growing level of activity among German model enginemanufacturers, most notably the market-leading Webra diesels produced by Fein und Modelltechnik of West Berlin. By 1952 he had made the decision that Graupner would enter the model engine business on its own account. Of course, this represented an entirely new business line requiring a level of precision engineering expertise which the Graupner company didn’t possess in-house. This being the case, they made the completely logical decision to seek outside assistance. To this end, they reached an agreement with a 35-year-old designer/machinist named Hans Hörnlein, who operated a precision machining business at 7917 Lindenstrasse 25 in Vöhringen, West Germany. Under the terms of this agreement, Hörnlein would manufacture a range of model engines exclusively for Graupner, who would undertake the marketing using the trade-name Taifun. Hans Hörnlein had been born on November 2nd, 1917 in Rauenstein, a small town in the Sonneberg district

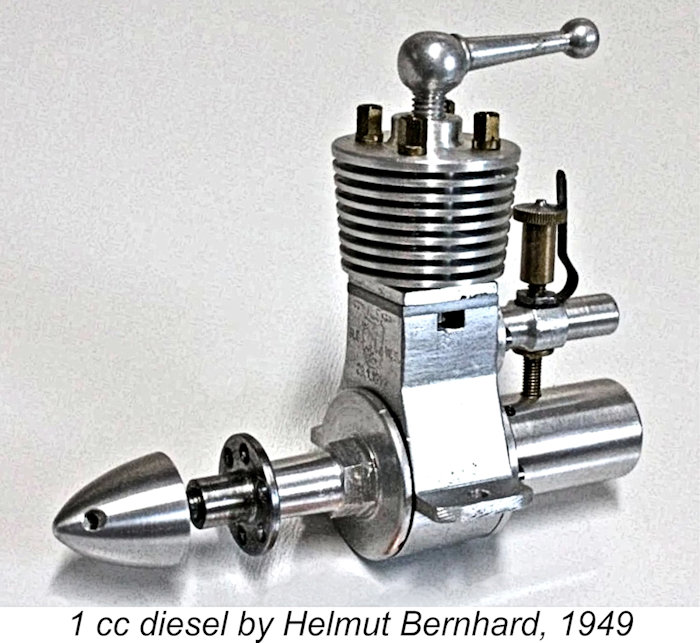

In 1948 Hörnlein assumed ownership of the remaining stocks of engine components from B-H. Kratzsch and began to manufacture the highly-regarded BHK engines on his own account. The two most prominent Kratzsch designs manufactured by Hörnlein were the 4.8 cc BHK-SZ4 and 2 cc BHK-SZ2 sideport diesels. As of the early 1950’s, Hörnlein was already a highly experienced and respected model engine manufacturer.

Now back to our main story............. In 1951 Hörnlein managed somehow to relocate with his family to Vöhringen, West Germany. There must be quite a story there …….. crossing the Iron Curtain was no small challenge at this time! Regardless, Hörnlein resumed the manufacture of model engines at his new location, initially with an independent design called the "HOEMO". This was soon superseded by another design which didn't received a name, at least initially. This latter engine was the initial manifestation of Hörnlein’s “three bolt” design which was destined to launch the famous Taifun range in late 1952. It was the quality of these engines that convinced Graupner of Hörnlein’s ability to manufacture the Taifun model engine range to the required standard. Vöhringen lies some 81 km to the south-east of Kirchheim unter Teck, but this was clearly not seen as a problem by Graupner given the fact that Hörnlein’s role was to be confined to the manufacturing of the engines, which would all be shipped to Graupner for distribution. The arrangement was to prove to be a durable one, surviving until the early 1970’s when Hörnlein disassociated himself from Graupner and went out on his own account with his Profi range. More of that below in its place. Hörnlein wasted no time in fulfilling his side of the bargain. By the autumn of 1952 he had completed the designs of the first-generation Taifun engines and had put six distinct models into series production. These were the relatively rare “three bolt head” Taifun diesels which made their market appearance in late 1952. Let’s look at them first. The Early Taifun Diesels – the “Three-Bolt Head” Models

This design configuration was soon found by experience to be seriously flawed. The problem was the structural integrity of the cylinder hold-down system. The security of the It was found by sad experience that even a moderate crash was often sufficient to fracture these lugs, separating the cylinder from the case. It was also found that the cylinder retaining screws had to be tightened very uniformly to avoid distortion of the cylinder liner.

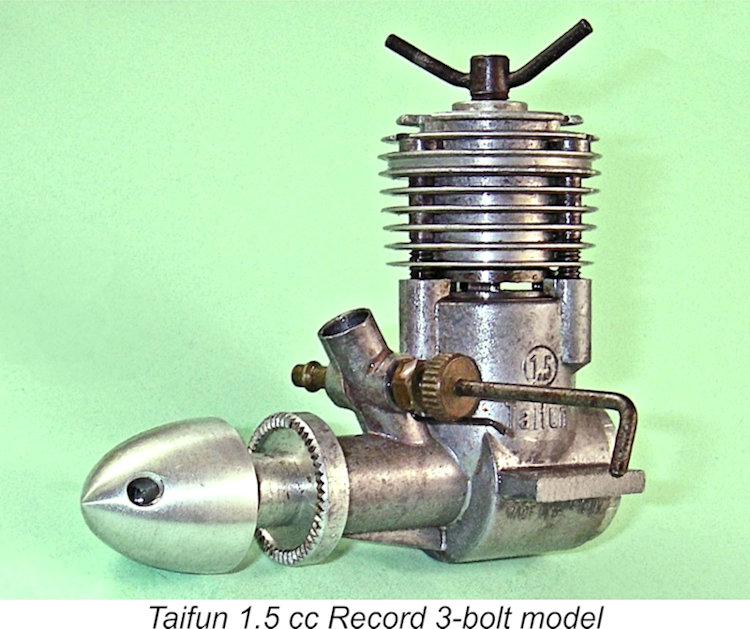

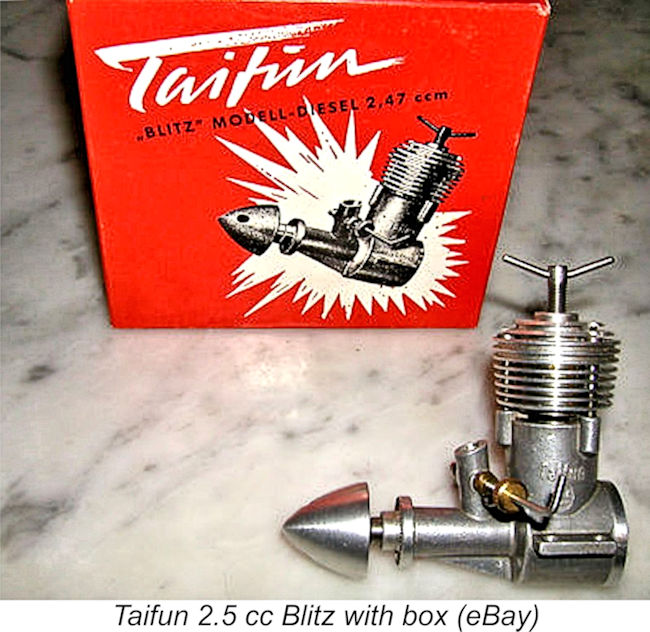

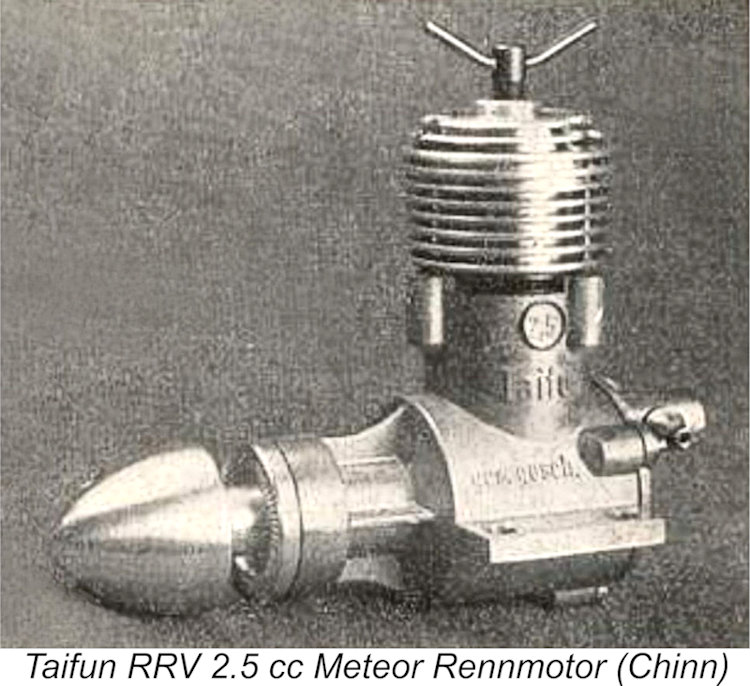

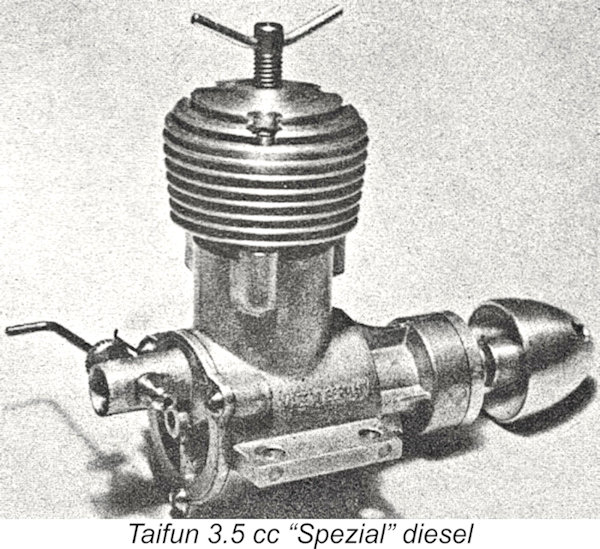

Six distinct models were offered, all of which were given individual names – the 1 cc plain-bearing model was the Taifun “Junior”, the 1.5 cc plain-bearing offering was the Taifun “Record”, the 2.5 cc plain bearing version was the Taifun “Blitz”, the 2.5 cc crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) ball-race model was the Taifun "Meteor", the 2.5 cc disc rear rotary valve (RRV) ball-race model was the “Meteor Rennmotor Spezial” (Meteor Special Racing Engine), and the 3.5 cc unit was an over-bored and up-stroked "Meteor Rennmotor" marketed as the Taifun "3.5 cc Spezial”. Only the latter two models featured RRV induction, the others being FRV designs.

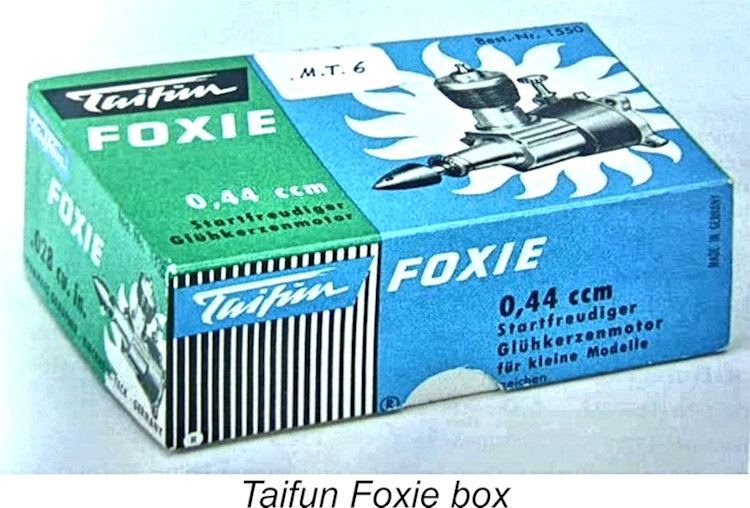

The packaging of these engines was quite eye-catching, with very sturdy boxes which were clearly printed and brightly coloured. The boxes were individually labelled and decorated for the model which they contained - no use was made of a generic box. Each engine was accompanied by a well-written instruction sheet, a substantial beechwood test block and a tommy bar to suit the spinner nut. This high standard of packaging was to be continued throughout the life of the Taifun range.

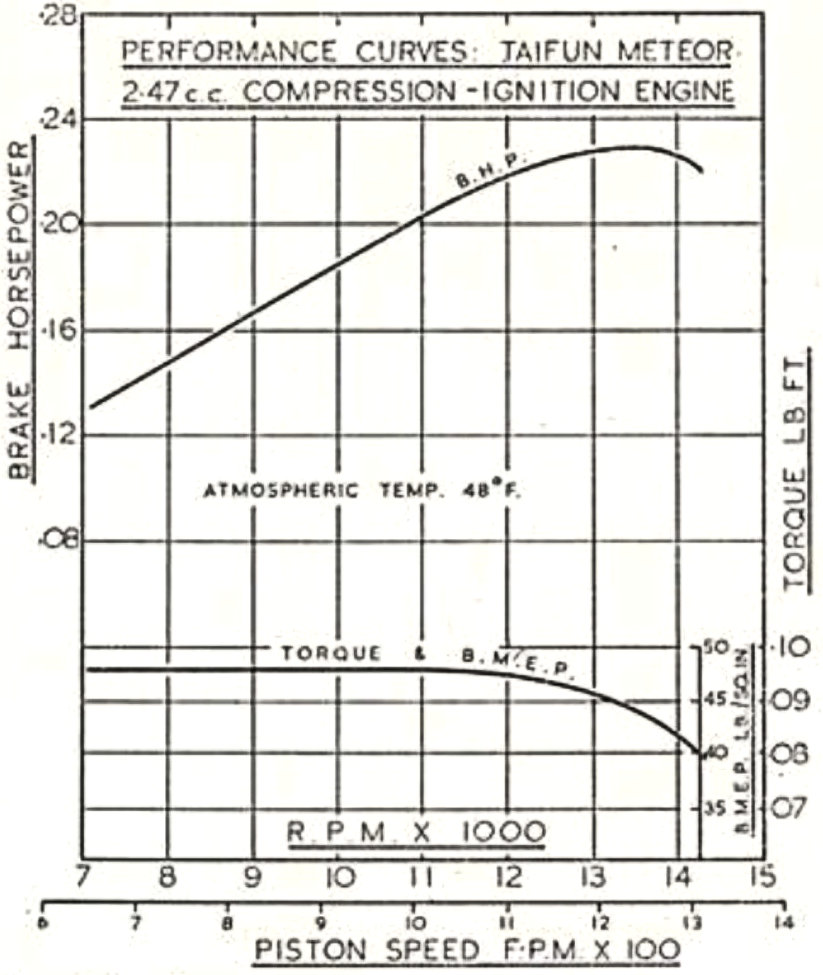

This test was published in the April 1954 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Although unattributed, the report was almost certainly authored by Peter Chinn. The tone of the test report was almost uniformly positive. The engine was said to be “nicely made”, with the quality of the main die-casting drawing particular notice as being “outstandingly good”. The manufacturers were commended for supplying a beechwood test mounting block, a tommy bar for the spinner nut and a length of suitable fuel tubing. Apparently all Taifun motors were supplied with this equipment. In performance terms, starting both hot and cold was said to be “easy”, with no requirement for a preliminary exhaust prime. The engine was found to run without excessive vibration, also being “reasonably smooth running” and exhibiting no tendency to sag when hot.

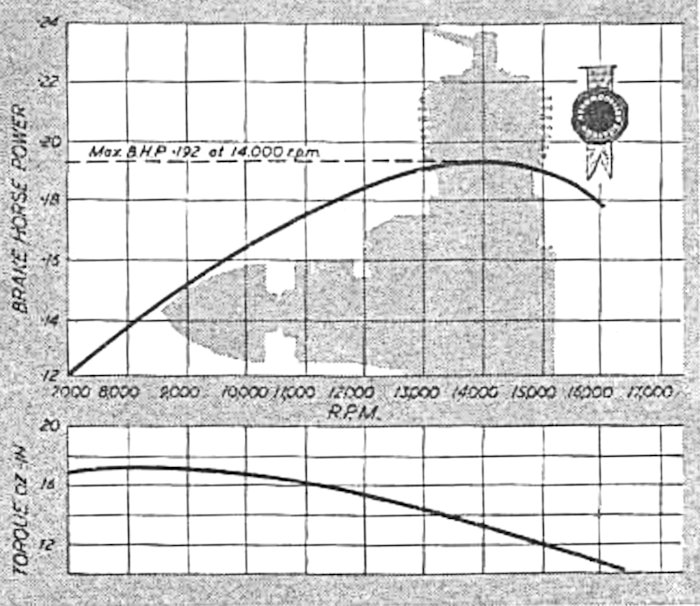

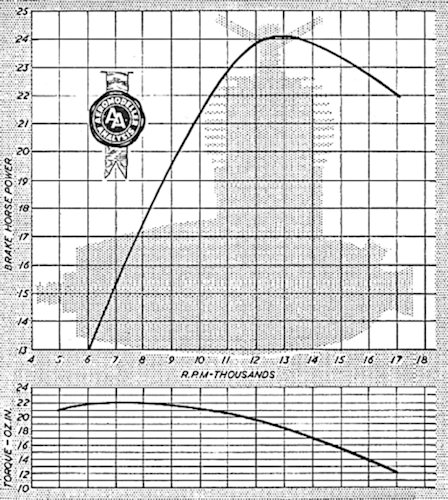

As far as output went, the tester reported a peak of 0.234 BHP @ 13,500 RPM. This fell somewhat short of the manufacturer’s claim of 0.27 BHP @ 14,500 RPM, but the tester felt that a “good” example which was well run in might well approach the claimed figures. A looser contra-piston would probably also have helped in permitting the establishment of an optimized compression setting at any given speed.

While Hans Hörnlein was occupied in wrestling with the “three-bolt head” Taifun diesels, the parent Graupner company was far from idle. In addition to further developing their model kit business and marketing the Taifun engines, they were engaged in the development activities leading up to their entry into the radio control (R/C) field. The first Graupner R/C control systems were developed in 1954 along with Graupner’s first kitted R/C models. Graupner’s very popular “Standard 10” R/C system hit the market in 1955. Meanwhile, Hans Hörnlein had completed work on a range of entirely new designs which were intended to replace the “three-bolt head” models in the Taifun model engine range. Let’s look at these models next. The Second-Generation Taifun Models

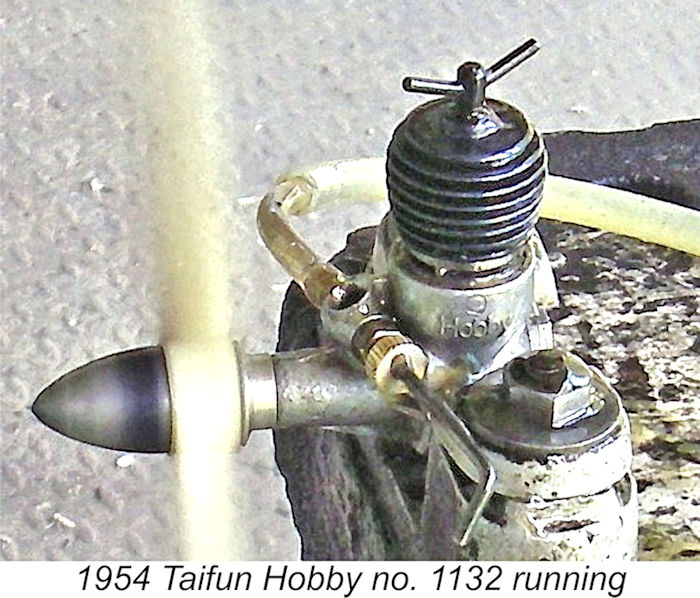

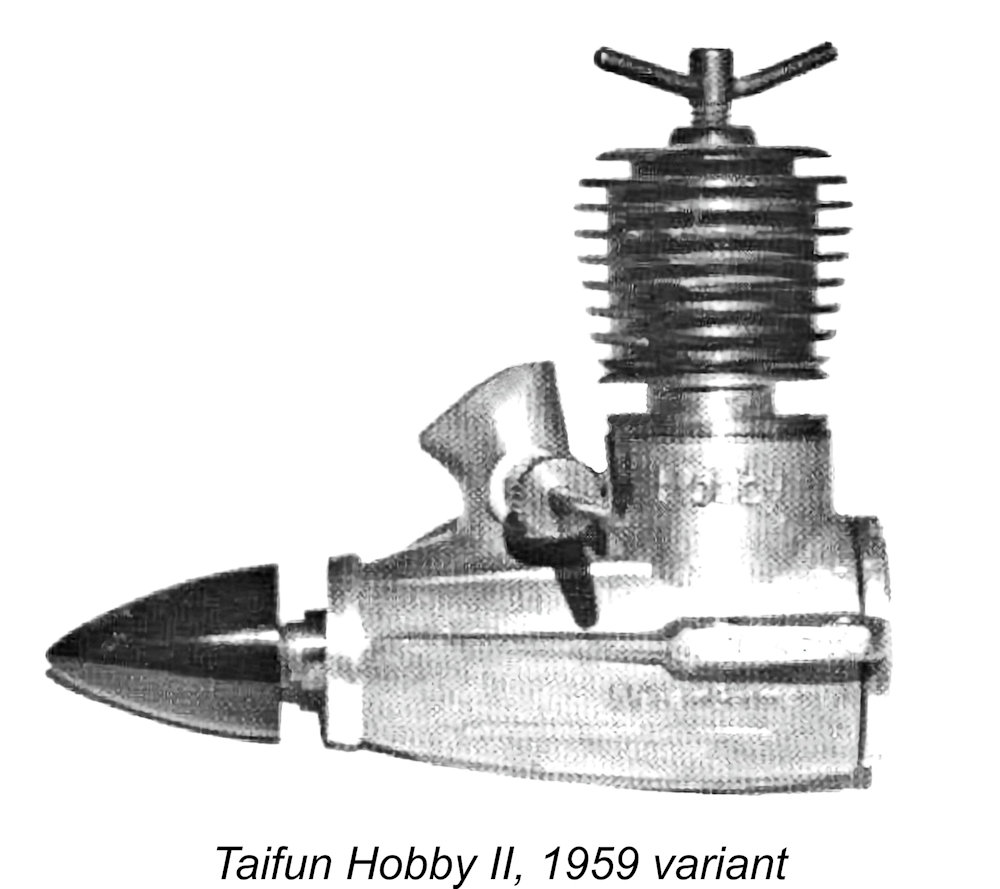

Hans Hörnlein’s initial response to this desire appeared in 1954 in the form of the vastly improved Taifun Hobby 1 cc diesel. This was the first of a series of Taifun model diesels using a screw-in cylinder in place of the former three-bolt system which had been found wanting. The Hobby was a commendably light and compact 1 cc plain bearing diesel using FRV induction. Bore and stroke were 10.67 mm and 10.92 mm respectively for an actual displacement of 0.98 cc. The engine tipped the scales at 63 gm (2.22 ounces).

I've never actually run a full bench test on a Hobby, but I can confirm from personal experience that it is indeed a fine-handling and sweet-running little diesel with a performance that is fully consistent with the figures reported by Warring. It's always been among my favorite 1 cc diesels.

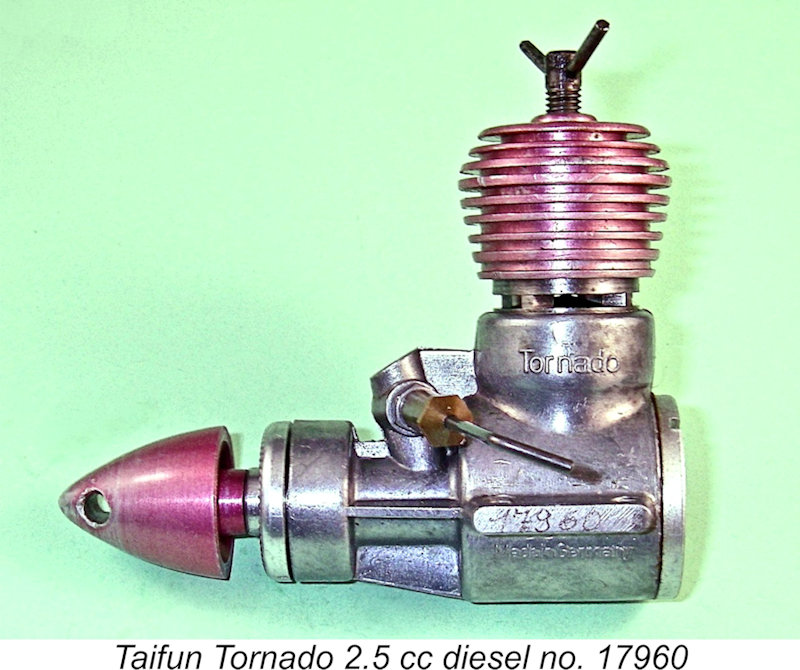

A third new model which appeared at more or less the same time was a revised 2.5 cc plain bearing model called the Rasant which was intended to be a replacement for the Blitz. This was very far from being a straightforward plain bearing version of the Tornado. Although it used the same revised screw-in cylinder design as the Hobby and Tornado, bore and stroke The very light weight and long-stroke geometry of the Rasant seem to indicate that it was intended for use in situations where high torque rather than peak horsepower was the predominant requirement, with light weight as an added bonus. It would have been an excellent powerplant for sport and scale models of all types, particularly free flight designs given its very light weight. Peter Chinn’s “Accent on Power" article in the August 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft” included a summary of the revised Taifun range. Chinn noted that the 1.5 cc Record had been dropped, while the Hobby, Rasant and Tornado had respectively replaced the Junior, Blitz and Meteor models. The Hobby and the Tornado were the subject of a somewhat unusual double test by Ron Warring which appeared in the April 1955 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. Warring began by reporting on the Hobby, which he characterized as “a delightful power unit – right from the moment of first starting”. Starting was very prompt and running was said to be “very consistent”. The engine was cited as being “extremely flexible on the controls”. Vibration levels were found to be “quite low”.

Unfortunately, the larger Tornado model fared rather less well in Warring’s hands. To begin with, the engine had apparently been assembled very much on the tight side, never freeing up completely during the test period. This tightness extended once again to the contra-piston, which was said to have been “almost impossible to adjust” once warmed up. The continued use of a hardened steel contra piston The alloy prop driver was mounted on a taper at the front of the shaft. A further complication arose when it was found that the Tornado’s prop driver was cracked as received. This created serious difficulties when it came to securing the various test airscrews. Despite these difficulties, Warring did succeed in extracting some performance data. Starting was said to be “generally excellent, even with small propellers”. Generous finger choking was found to be sufficient for starting. Once running, the Tornado exhibited a greater sensitivity to fuel formulation than its smaller Hobby brother, displaying a tendency to misfire which could not be completely eliminated using the rather balky compression control.

This impression is borne out by the results of a test which I ran back in 2007 on my own illustrated example of the original Taifun Tornado – engine no. 551. This engine was little used, but was assembled with a nice smooth piston fit and a contra-piston which was fully adjustable at all times. My notes confirm that it started very easily and ran flawlessly, being perfectly straightforward to adjust either hot or cold. The observed prop/RPM figures suggested a peak output of around 0.265 BHP @ 12,800 RPM – far more like what one would expect from an engine of this specification, with perhaps more to come following a little additional running time.

I tuned my flying" example of the Tornado, engine no. 17960, to improve its performance somewhat. This included lightening the piston and creating a little counterbalance on the crankweb. I also modified the crankshaft induction port a little to improve its funtionality. This engine ran very strongly with minimal vibration, serving me well in a number of models. A bench test some years ago implied a peak output of around 0.285 BHP @ 13,500 RPM. The one downside was the very vulnerable original Taifun needle valve, which invariably broke in the first hard crash! I replaced it with a far sturdier P.A.W. assembly, with which it worked very well. This was the usual fate of the externally-threaded needles used in all of the early Taifun models. The Rasant was also the subject of a published test report, although this was one of Peter Chinn's condensed "mini-reports" which appeared from time to time in an attempt to keep up with the large number of new engines then passing through Chinn's hands (how times change!). The report on the Rasant was published in the February 1956 issue of "Model Aircraft". No actual performance data were presented beyond the bare statement that Chinn's testing confirmed the manufacturer's claimed figures of 0.23 BHP @ 12,000 RPM.

The Rasant was also reviewed in the "Logging the Motor Mart" feature which appeared in America in the October 1955 issue of "Flying Models". This review confined itself to a description of the engine together with a few prop/RPM figures. Its main value in a historical context is its confirmation of the fact that the Taifun range was then being distributed in the USA by the Wilshire Model Center of Santa Monica, California. The Graupner company was clearly extending its market reach!

The attentive reader will have noticed the range of anodizing colors applied to the various alloy components used in the second-generation (and later) Taifun engines. Hans Hörnlein's friend and business associate Ronald Valentine recalled that these colors were selected for each model by Mrs. Hörnlein! By 1956 the Taifun engines were selling sufficiently well that steps had to be taken to increase production. To meet this need, a new factory was built during 1956, still located in Vöhringen. The attached illustration of this facility appeared in a 1956 issue of the German magazine "Mechanikus". Thanks to Peter Valicek for providing it! Next Step – the Taifun Hurrikan

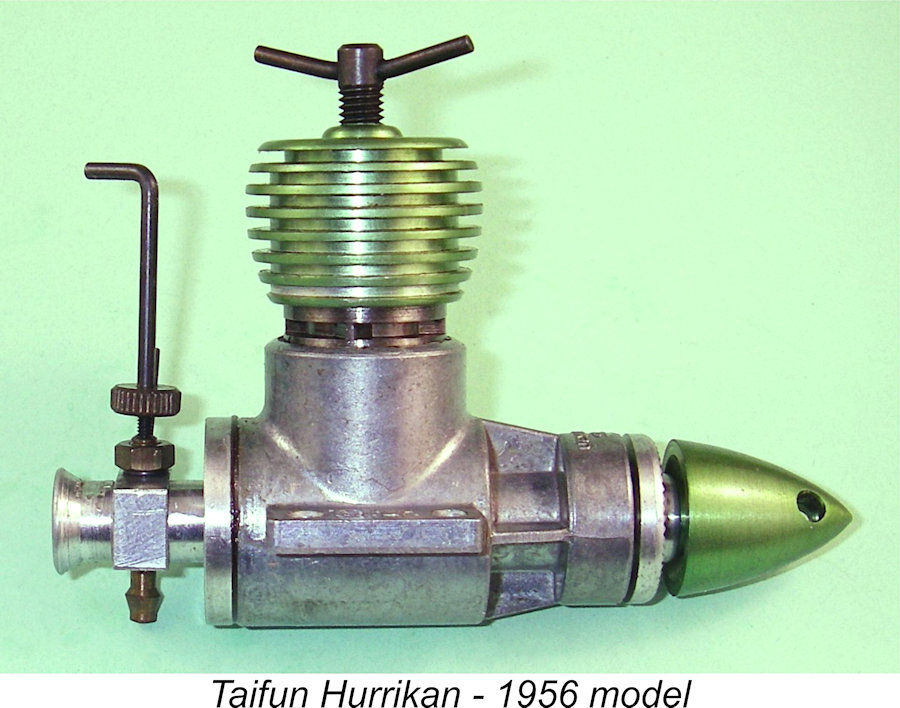

This outstanding engine (one of my personal favorites) represented a wholesale departure from the design of the original Record 1.5 cc model. Once again it used the same revised cylinder configuration as the Hobby, Rasant and Tornado, but now a twin ball-race crankshaft was added to the mix. Hörnlein could have stayed with FRV induction, making the Hurrikan a reduced-scale Tornado, but instead elected to try something quite new in the context of the Taifun range – rear reed valve induction. Of course, reed valve induction itself was nothing new – the Cox range from America had been using it for some years by 1956. It was not even an innovation in a diesel context - Aerol Engineering had employed the arrangement in their well-known Elfin BB series beginning in mid-1954. Reed valve induction had also been applied by E.D. to special team-race versions of their famous 2.46 cc Racer diesel beginning in 1954, culminating in the late 1956 introduction of the reed valve Greenhead Racer. However, the application of this technology represented a major step off the beaten track in a Continental context.

Each reed was a rather intricate and delicate stamping having a continuous circular outer annulus with an internally-protruding "flap" which served as the actual reed. The outer annulus was held against the inner face of the backplate recess by a perforated aluminium alloy backing plate which both protected the reed and limited the amplitude of its motion when in operation. The entire assembly was retained in the backplate by a pressed-on alloy cap which held the reeds and backing plate in position. In terms of longevity, I view this reed design as one of the engine's potential Achilles Heels. Like the equivalent component used in the Elfin reed-valve models, the reed featured small-radius 90-degree corners at the points where the edges of the "flap" intersected with the firmly secured circular outer annulus. These sharp corners would inevitably create cyclic stress concentrations at those points when the reed was flexing as the engine ran - a tailor- I would anticipate that extended use of the engine could well cause the reed to fail at the junction points. That said, I have not encountered any widespread criticism of the Hurrikan on that score. Perhaps the material selection and use of two reeds made the difference. The carburettor arrangements were more or less copied from those seen on the Cox engines from America. A remote needle valve was employed, supplying fuel to the intake venturi through four radially-disposed jet orifices penetrating the intake wall. The intake was thus unobstructed by a spraybar, hence having a perfect venturi configuration. A nice touch was the incorporation of a steel mesh air filter screen. One trick which Hörnlein didn’t miss was the application of sub-piston induction to the Hurrikan’s operating cycle. In my personal opinion, the use of sub-piston induction in a reed valve design is theoretically almost a necessity if maximum performance is to be achieved. Even the best reed valve is inherently more restrictive than a fully-open rotary valve, hence benefiting greatly from the assistance provided by sub-piston In all other respects, the Hurrikan was in effect a downsized Tornado. Bore and stroke were 13 mm and 11.2 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.49 cc. The engine weighed in at 108 gm (3.8 ounces) – a fairly high weight for a 1.5 cc diesel, but perhaps not unreasonable given the use of twin ball races allied to the engine’s very sturdy construction. This weight was about the same as that of the 107 gm Oliver Tiger Cub Mk. I of 1952 and a little less than the 113 gm weight of the Elfin 149 BR. It didn’t take long for the major English-language engine testers of the day to direct their attention to the Hurrikan. First out of the starting gate was Peter Chinn, whose report appeared in the September 1956 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Chinn was clearly quite impressed with the engine, characterizing it as “an out-of-the-rut design” with its combination of reed valve induction, remote needle valve and ball-race crankshaft. He noted that “Taifun engines have always been well-made ……….and the Hurrikan is no exception”. He spent much of the report describing the reed valve induction system in detail.

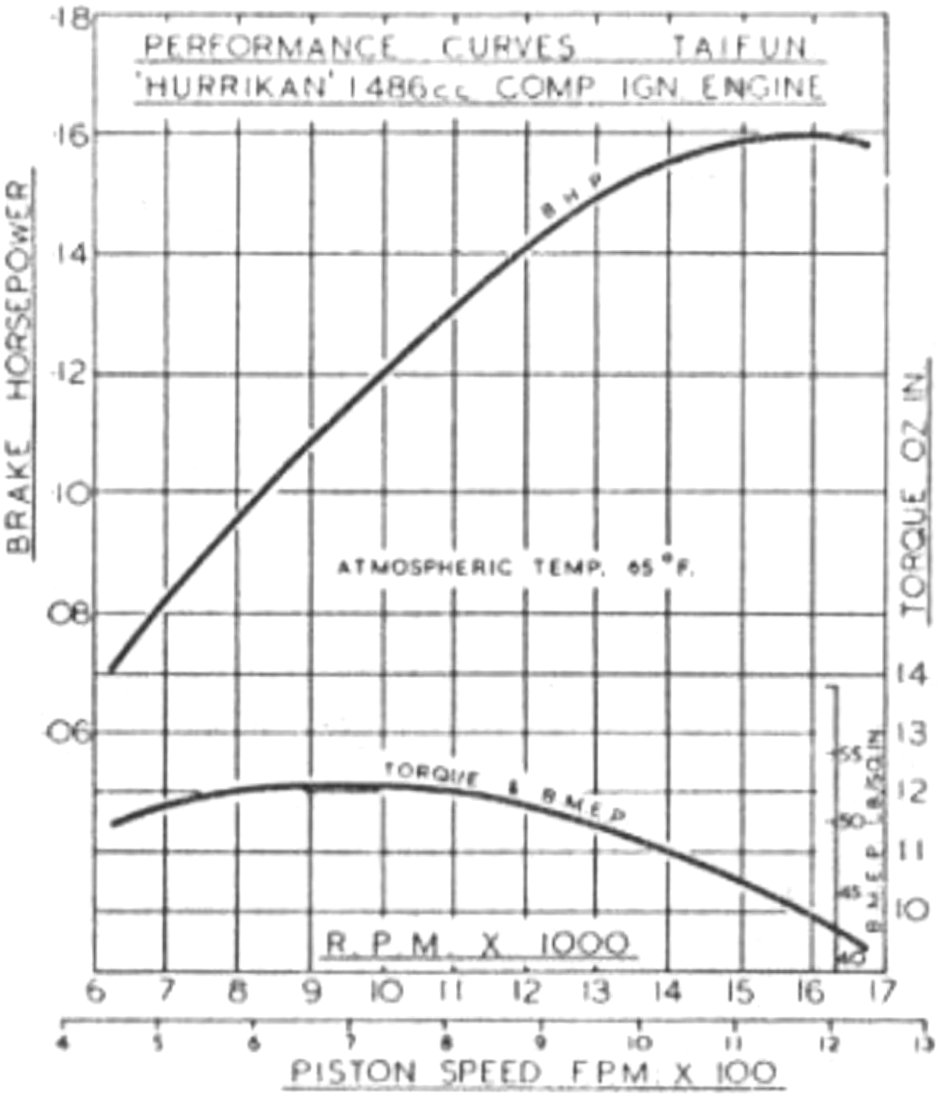

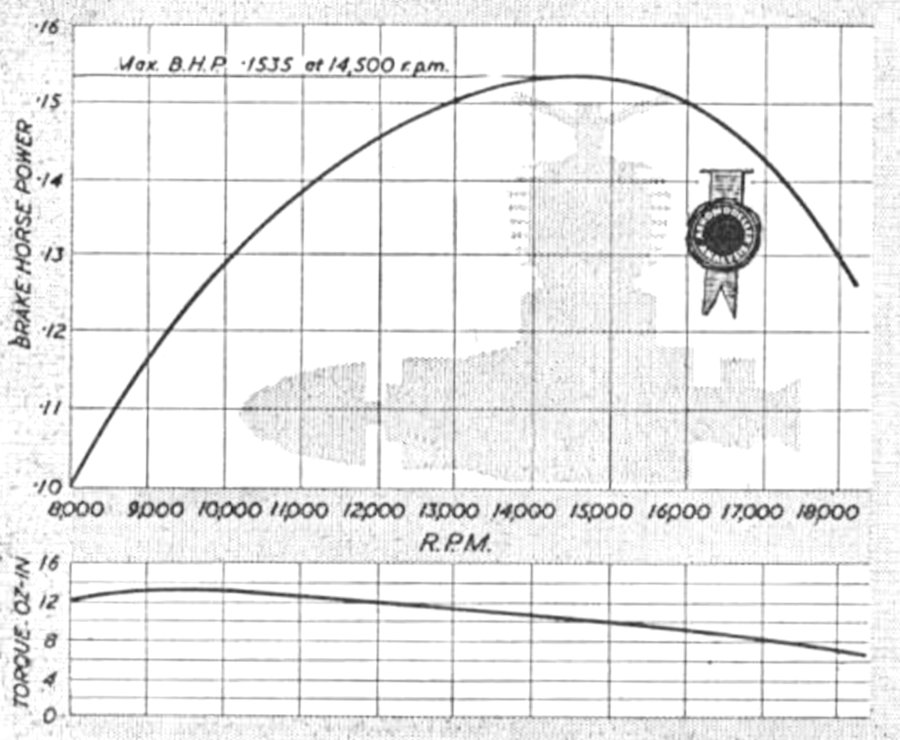

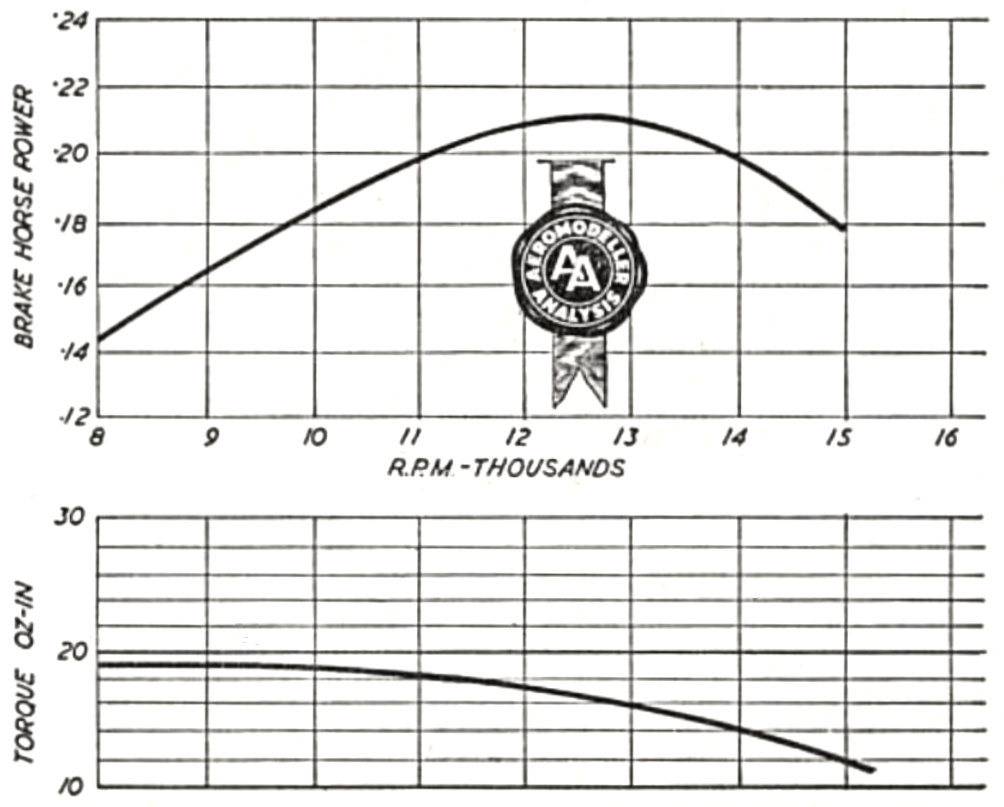

Chinn reported a peak output of 0.159 BHP @ 16,000 RPM, a performance which had only been equaled by two other 1.5 cc diesels in the world at Chinn’s time of writing. He summed up the Hurrikan as “one of the best and most interesting model engines yet seen from Germany”. It took a little longer for Ron Warring of “Aeromodeller” to get around to testing the Hurrikan. His report appeared in the January 1957 issue of the magazine. Warring had access to three examples of the engine, only one of which was completely free from defects. The other two suffered from such issues as poorly-seating reed valves, flawed conrod machining and poorly-cut exhaust ports.

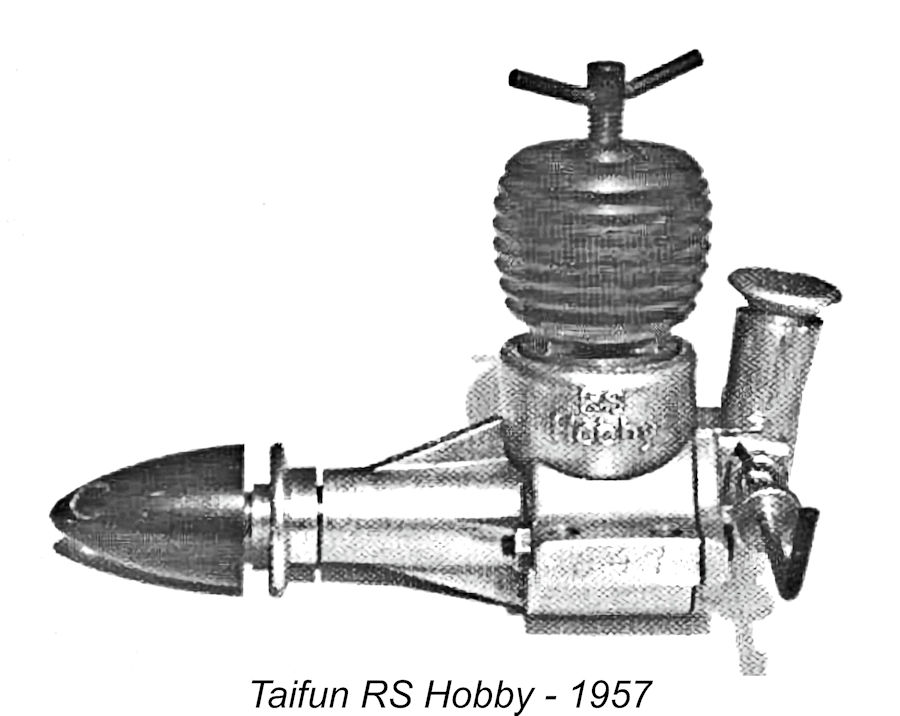

As was so often the case, Warring failed to match the level of performance that had been reported earlier by Chinn, although he came close. He found a peak output of 0.1535 BHP @ 14,500 RPM, which was still a better-than-average performance for a 1.5 cc diesel by the standards of the day. These two test reports must have created a very positive first impression of the Hurrikan in the minds of British aeromodellers. The British distribution of the Taifun range was soon taken up by A. A. Hales and later continued by Ripmax. I recall seeing a number of Taifun engines in use during my own teenage aeromodelling years in England. A False Start - the Taifun RS Hobby Given the success of his new 1.5 cc reed valve model, it was only natural that Hans Hörnlein would attempt to extend the use of the reed valve technology to other displacement categories. His first such attempt was the development of a reed valve version of the FRV 1 cc Hobby, which had proved to be very popular and remained one of the best-performing 1 cc diesels then available.

The reed valve itself was simply a scaled-down version of the assembly used in the Hurrikan, with two reeds and a backing plate being retained by a pressed-on cap. The backplate incorporated a steeply downdraft intake which was obviously intended to minimize the axial length of the engine.

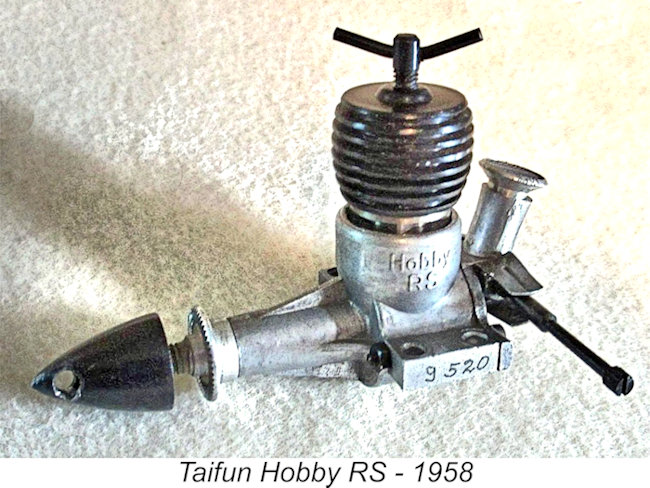

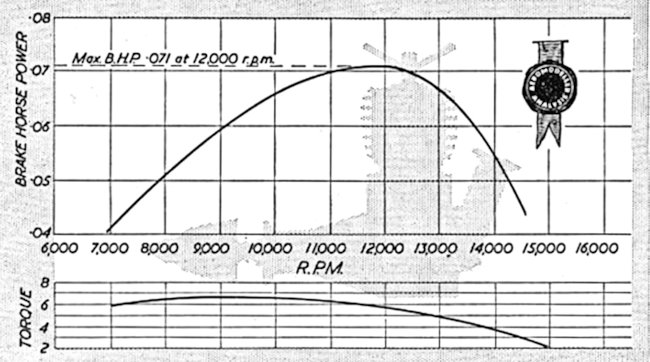

It might be expected that a reed valve Hobby would perform at a relative level compatible with that achieved with the 1.5 cc Hurrikan. However, this was sadly not the case. A test of the Hobby RS by Ron Warring which appeared in the March 1958 issue of “Aeromodeller” made it quite clear that this experiment had fallen some way short of success.

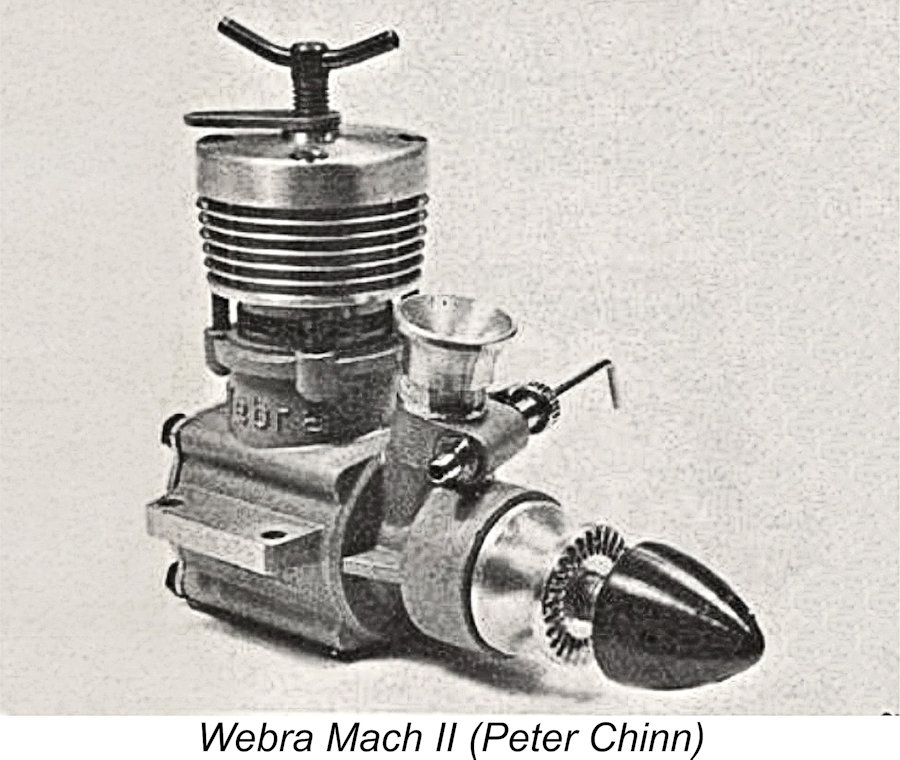

As a result, the Hobby RS experienced rather limited sales success, apparently being withdrawn in early 1959. It remains one of the less commonly-encountered Taifun models today. While all this was going on in Vöhringen, the parent Graupner company was engaged in further expanding its marketing activities. In 1957 they became the official German distributors of the O.S. range. Soon thereafter, they were also appointed as the official German distributors of the Cox range from America. The Next Stage – Enter Günther Bodemann Throughout the 1950’s, one of the most respected names in German model engine design was that of Günther Bodemann, who had been associated with the Webra engines manufactured by Fein und Modelltechnik of Berlin from the initial establishment of that range in the early 1950’s. Among other things, Bodemann had been responsible for the development of one of the most highly-regarded diesels of the mid-1950’s, the 2.5 cc Webra Mach I, as well as its glow-plug Webra 2.5 R companion.

At this distance in time, it’s a little difficult to discern the motivation for this move on either side. Hans Hörnlein had clearly demonstrated his capabilities as a model engine designer, leading one to wonder why he felt that the addition of Bodemann to his company’s engineering staff was warranted. It’s possible that he was becoming too involved with the production of the engines and the associated business matters to find sufficient time to remain involved as their primary designer. His company may also have become increasingly invoved with contract precision engineering work for others. Finally, there may have been some attraction to the idea of depriving the rival Webra manufacturers of their star designer! From Bodemann’s standpoint, there’s no evidence to suggest that he had fallen out with his former employers – indeed, he was to return to Webra in 1962 after the company had passed into the sole ownership of Martin Eberth. Apart from any financial inducement, perhaps he simply wanted a change, or maybe he wanted a break from living in West Berlin behind the infamous Berlin wall. Regardless of the reason(s) for Bodemann’s move, his influence was not long in making itself felt. Let’s look at the next-generation Taifun engines which resulted from Bodemann’s involvement. The First Bodemann-influenced Taifuns

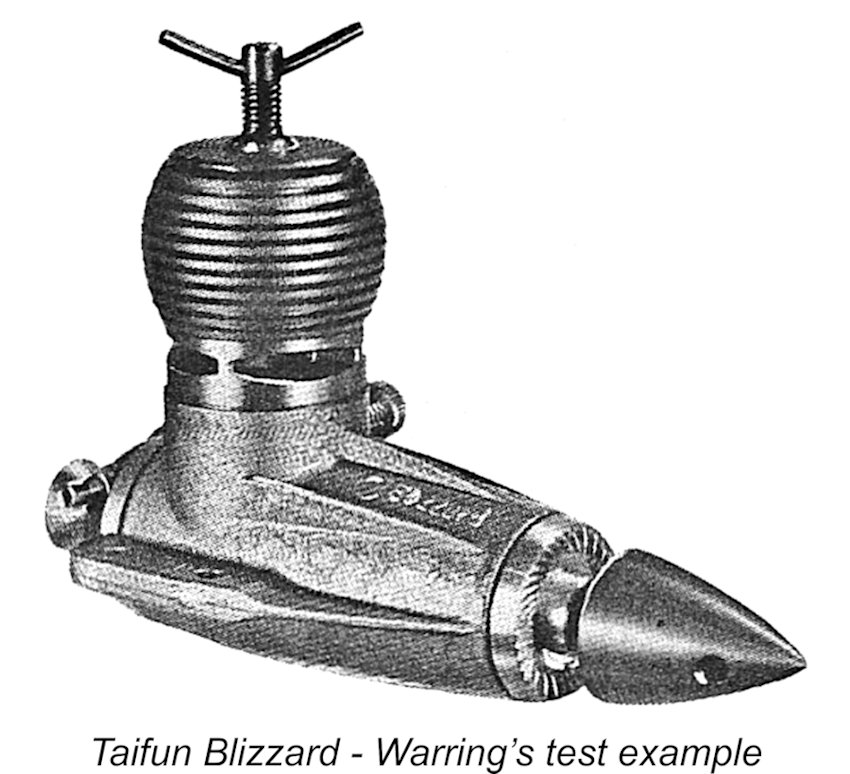

Setting aside its very “futuristic” appearance, the Blizzard was in effect an enlarged version of the established Hurrikan with a few internal modifications along with a comprehensively re-styled exterior. Bore and stroke were 15 mm and 14 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.47 cc, while the engine weighed in at 170 gm (6 ounces exactly).

A welcome change seen on the Blizzard was the fitting of an entirely new fuel needle. Although it provided very fine fuel mixture control, the externally-threaded needle used previously had shown itself to be extremely vulnerable to The exhaust port belt through which the four exhaust slots were cut was now quite a bit thicker than the equivalent feature in the earlier models. The exhaust ports on the earlier examples were cut with a Vee-profile cutter which created an "expanding" port configuration - illustrated engine number 1490 is of this type. The ports featured on the later examples exemplified by illustrated engine number 14304 reverted to a conventional saw cutter.

Quite apart from its futuristic general styling, maximum use was made of colour to enhance the Blizzard’s appearance - Mrs. Hörnlein was kept busy! The cooling jacket, spinner nut and carburettor dome of the earliest examples were all anodized blue, although the color of the cooling jackets on the later examples was changed to red or a reddish shade of pink. The blue colour was retained all along for the spinner and carburettor dome. As if this wasn’t enough, the crankcase received a coat of mottled blue-gray stove enamel. This latter treatment was omitted on some of the later examples like engine number 14304 illustrated here. The result was a striking-looking engine that really stood out from the crowd. Like all of the Taifun engines, the Blizzard was very well made. But how did it stack up in terms of performance? The model engine testers of the day were keen to find out!

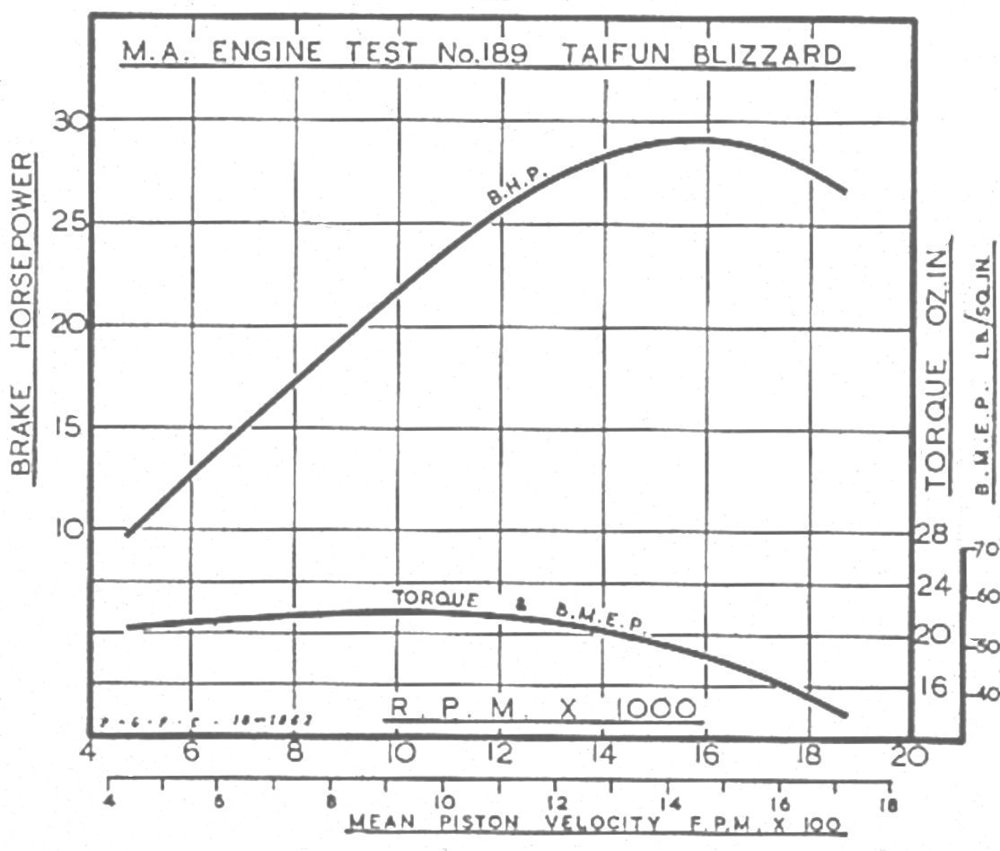

Despite this shortcoming, Warring found a peak output of 0.242 BHP @ 13,000 RPM. One might have hoped for more from this design……. A reduction in piston weight and a counterbalanced crankshaft would doubtless have worked wonders!

Chinn was equally complimentary regarding the Blizzard’s handling qualities, stating that “starting and handling qualities were really excellent”. Starting was said to be easy, hot or cold, on both large and small props. Control response also came in for favourable comment. Chinn was particularly appreciative of the fact that the Blizzard was “entirely free of the high-speed misfire that plagues many contest-type diesels at speeds above about 14,000 RPM”. On the downside, Chinn echoed Warring’s criticism regarding the engine’s tendency to vibrate, although he commented that this was somewhat less marked at the higher speeds tested. Once again, he cited the heavy piston and lack of counterbalance as being the probable causes of this behavior. Despite this failing, Chinn was able to report a peak output of 0.290 BHP @ 16,000 RPM, a considerable improvement on the figures reported by Warring. Not a world-beating performance by 1963 standards, but a reasonably respectable showing nonetheless.

This may reflect the possibility that my own example is better freed-up than Chinn's example was. Alternatively, I may just have a good 'un - such better-than-average engines invariably crop up in any series of quantity-manufactured engines. The one point which I can confirm is the engine's pronounced tendency towards excessive vibration - Warring and Chinn were perfectly correct in making that comment.

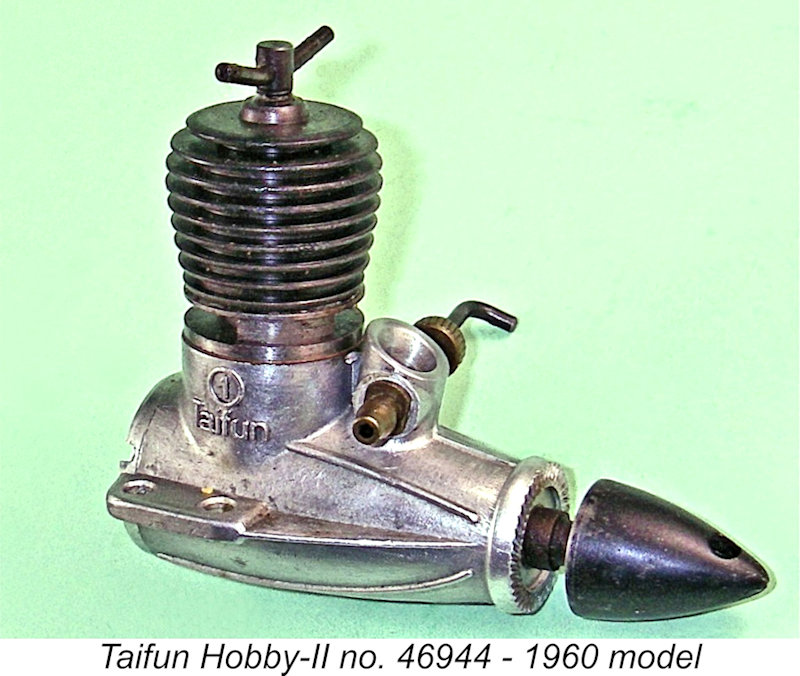

The cylinder of the Hobby now featured only two exhaust apertures, thus widening the intervening columns of metal to accommodate the overlap of the greatly enlarged bypass/transfer flutes which underpinned Bodemann’s design. The porting was now identical to that used in the twin bypass Cox engines. The bore was slightly reduced to 10.4 mm, with an increased stroke of 11.5 mm for an unchanged displacement of 0.98 cc. The engine was thus an even longer-stroke design than its predecessor. The bore reduction was probably implemented to provide more metal in which the revised overlapping bypass flutes could be formed.

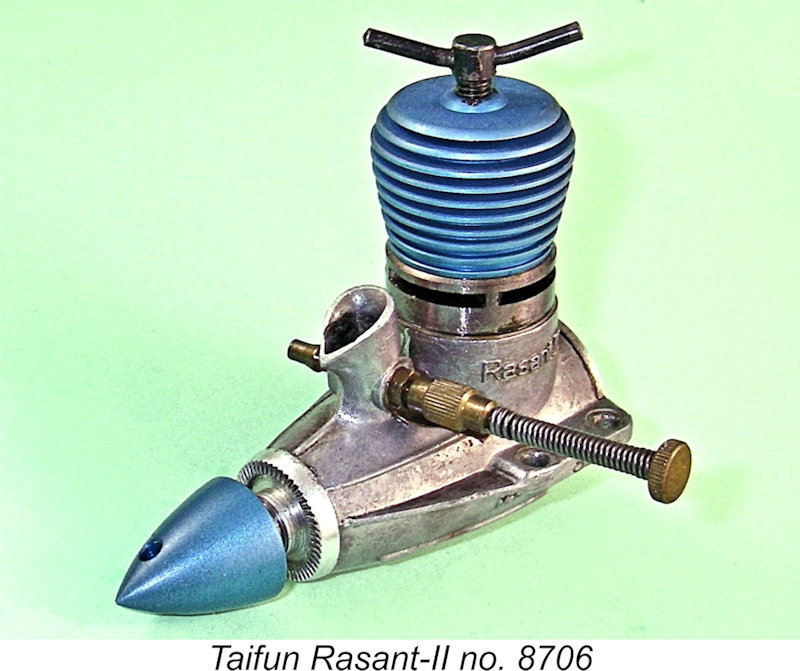

As far as I’m aware, neither the Rasant-II nor the Hobby-II were ever the subject of published tests in the English-language modelling media. Although I’ve never tested a Hobby-II, I would expect it to show a measurable performance improvement over the original Hobby, particularly in terms of torque development. Some years ago I tried a series of test props on my example of the Rasant-II, engine no. 8706. Although The “tea-pot” version of the Hobby-II didn’t last long, production being confined to the year 1959. By 1960 the crankcase die had been changed to eliminate the “tea-pot” intake in favour of a conventional circular intake. Otherwise, the engine continued unchanged. I have no knowledge of whether or not a similar modification was implemented for the Rasant-II. However, I admit that for me at least the "tea-pot" intake had a certain charm............... 1960 – Taifun Enters a New Era – Almost! In 1960, a decision was taken that Hörnlein’s company would become engaged in a new field of model engine manufacture, namely that of glow-plug engine production. Graupner had apparently become convinced that the future lay with glow-plug engines, but there doesn’t appear to have been much in the way of firm direction regarding the form that the initial Taifun glow motors should take.

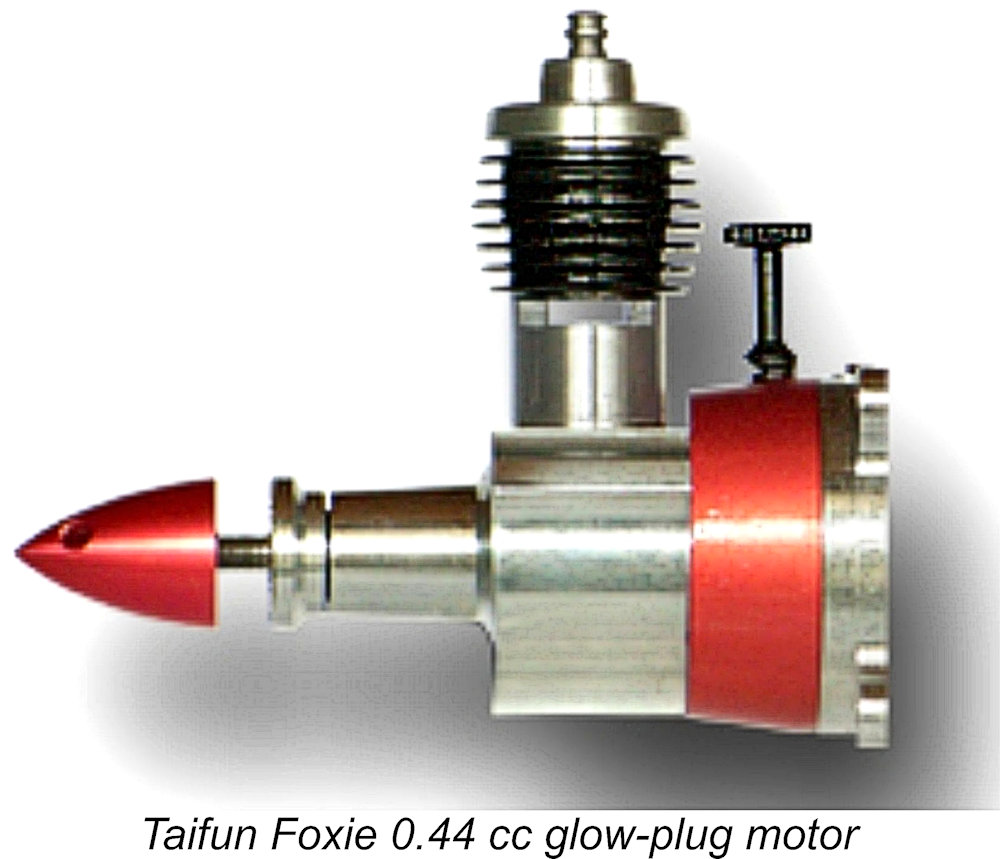

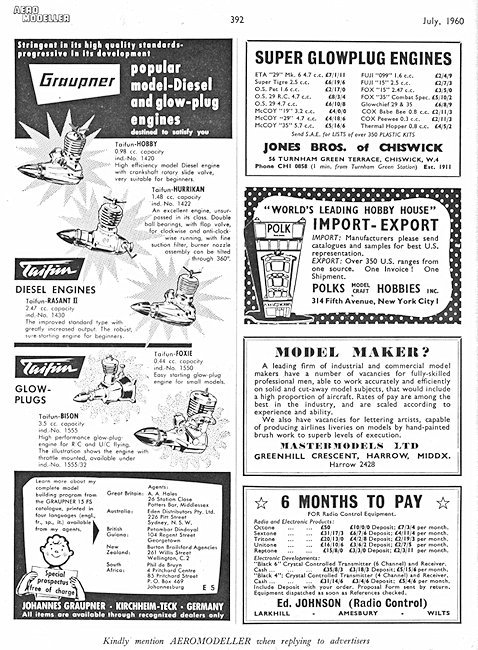

The Foxie was a cute little 0.44 cc glow-plug motor which looked at first glance to be a lot like one of the radially-mounted Cox reed valve models. Like the Cox engines, it used a glow head as opposed to a conventional glow plug. The original prototype example of the Foxie was apparently constructed using Cox Babe Bee components as a basis. However, appearances can be deceptive – the Foxie was actually a disc rear rotary valve (RRV) design. The engine was fully machined from barstock material, no castings being used. Bore and stroke dimensions were 8.0 mm and 9.0 mm respectively for a displacement of 0.44 cc. The Foxie weighed only 35 gm (1.23 ounces). The designers claimed a peak output of 0.04 BHP @ 18,000 RPM.

As it was, perhaps five examples were completed by Hörnlein and given to selected modellers for field testing. The balance of the already-manufactured components and boxes for the Foxie remained together but unassembled in the possession of Hans Hörnlein until 2000, when they were acquired by Hörnlein’s friend and former business associate Ronald Valentine, who completed about 200 engines between 2000 and 2006. These used mostly original Taifun parts manufactured back in 1960, although some missing components had to be newly manufactured. The engines completed by Ronald Valentine remain in circulation today, although they are offered for sale relatively infrequently. A number of these engines were constructed as diesels, in which form they ran well. Check this link for a look at one of these engines running! Finally – a Taifun Glow-Plug Model!

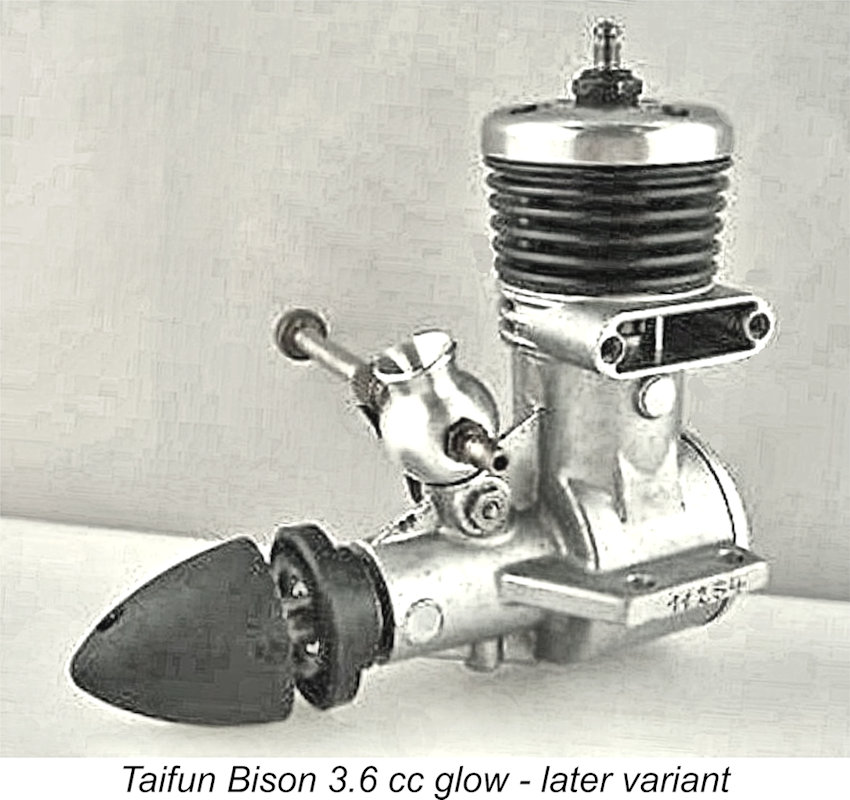

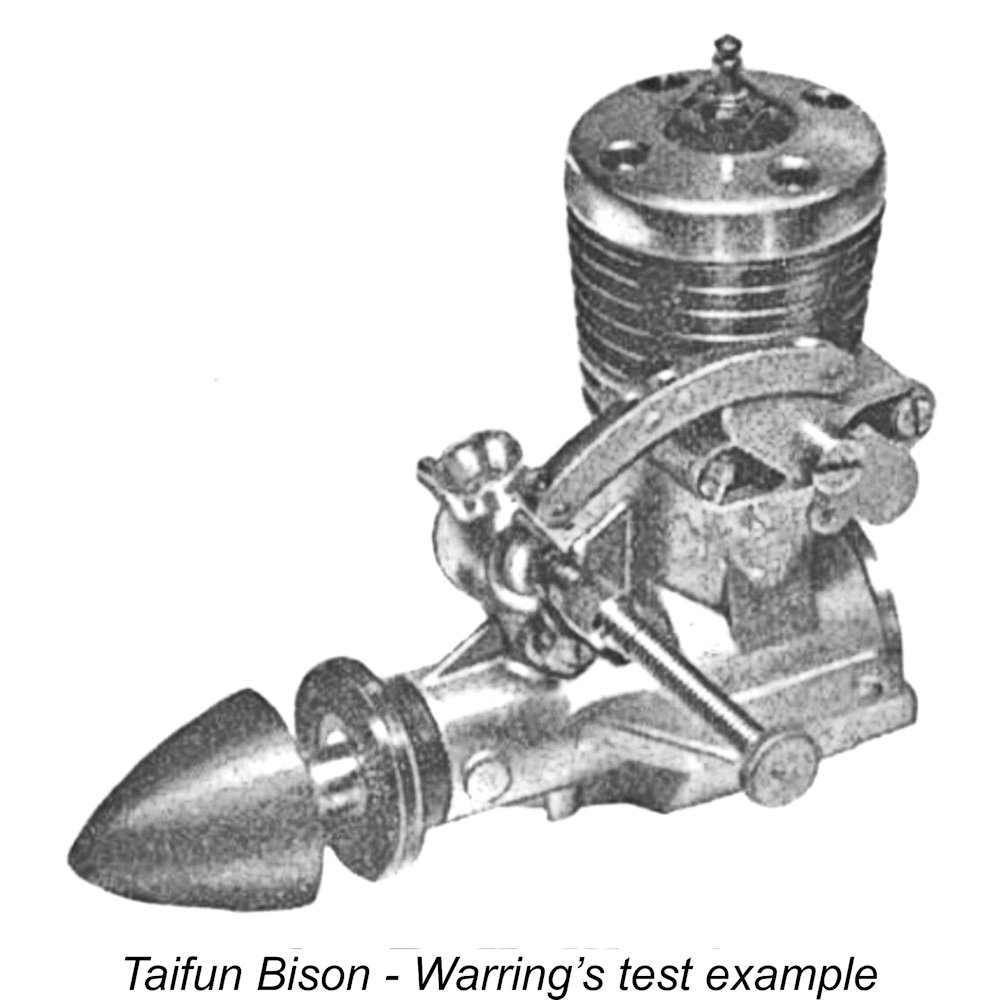

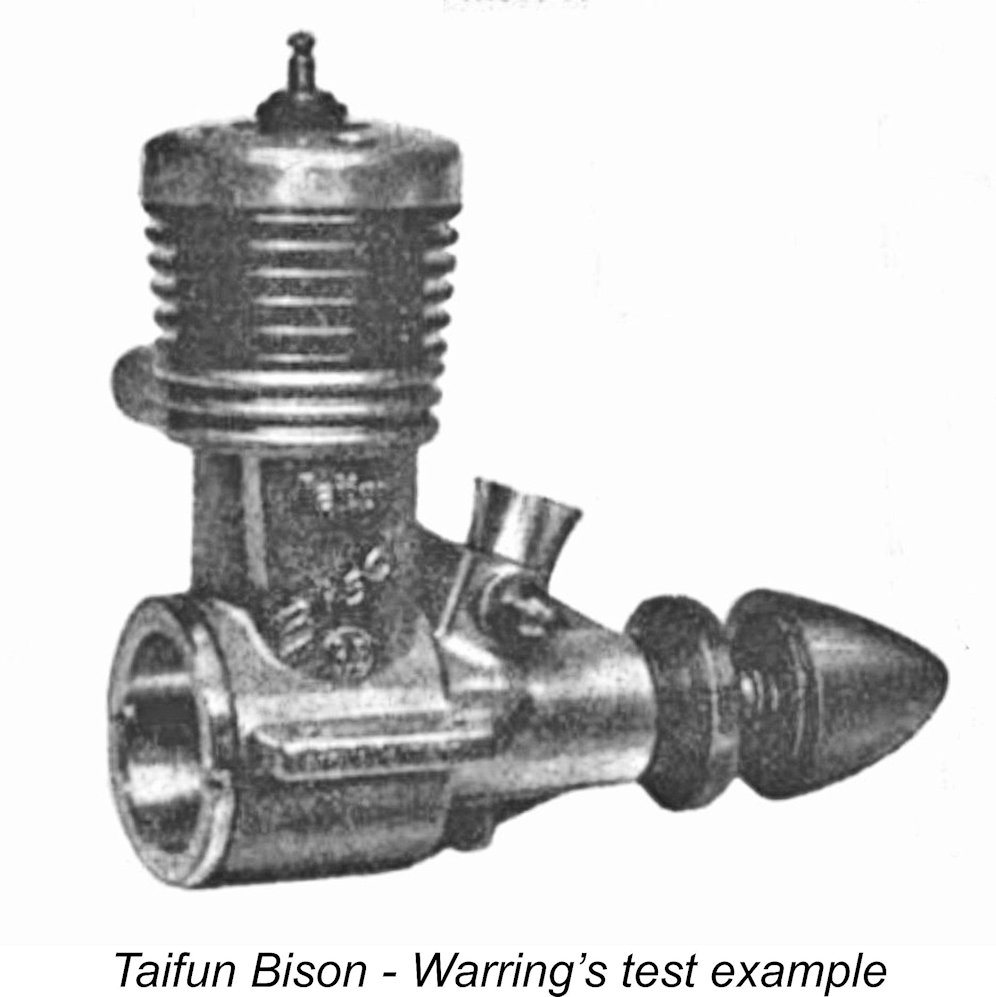

The Bison was a long-stroke plain bearing FRV glow-plug unit of completely conventional design configuration. Bore and stroke were 16 mm and 18 mm respectively for an actual nominal displacement of 3.62 cc. The bare engine weighed 170 gm (6 ounces even).

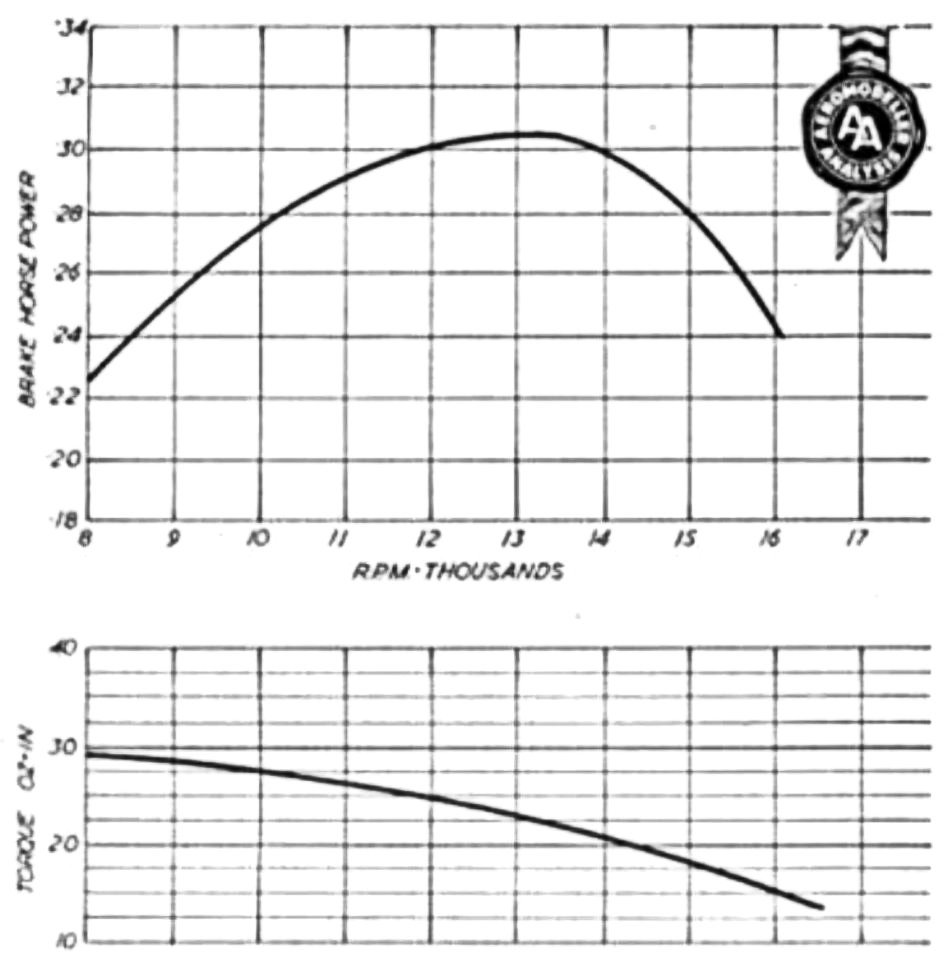

The Bison was the subject of a published test report by Ron Warring which appeared in the June 1961 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. Warring was highly complimentary regarding the standard of the engine’s construction, stating that “workmanship throughout is first class, with an excellent piston-cylinder fit”. The Bison was apparently supplied with both an R/C throttle assembly and a conventional venturi insert for control line or free flight applications. Warring tested the engine in both configurations, finding that the installation of the throttle produced “a penalty of 600 RPM at 10,000 RPM and approximately 1,000 RPM at higher speeds”. Presumably to show the engine in its best light, he only reported performance figures for the engine in un-throttled form.

Once running, Warring found that the Bison’s least attractive attribute was the level of vibration experienced throughout the tested speed range. This was doubtless due to the very heavy piston, for which the counterbalancing applied to the crankweb was clearly inadequate. Once again, a lighter piston would probably have worked wonders ……….why, oh why, didn’t Hörnlein and Bodemann attend to this glaring issue??

Reverting to the standard un-throttled intake and using a fuel containing 7% nitromethane, Warring reported a peak output of 0.304 BHP @ 13,300 RPM for the engine, which he rightly characterized as a “moderate” performance for an engine of this type and displacement. He reminded his readers that these figures applied to the unthrottled version of the engine, commenting that the throttled version might be expected to give “an appreciably lower performance, particularly at the high speed, and probably peaking at around 11,500 – 12,000 RPM”. Overall, it must be said that this constituted a somewhat lukewarm endorsement of the Bison. It can’t have contributed to much in the way of customer enthusiasm! Despite this, the Bison appears to have remained on offer for some years, implying that it must have attracted a reasonable number of customers. R/C Continues to Dominate – the Taifun Zyklon Diesel

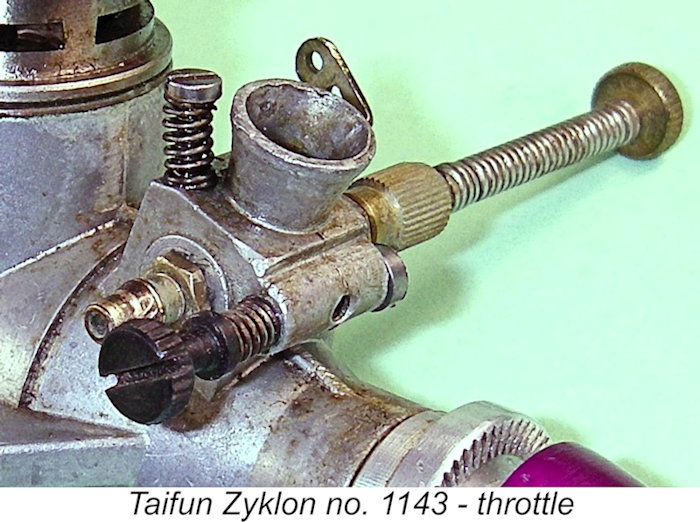

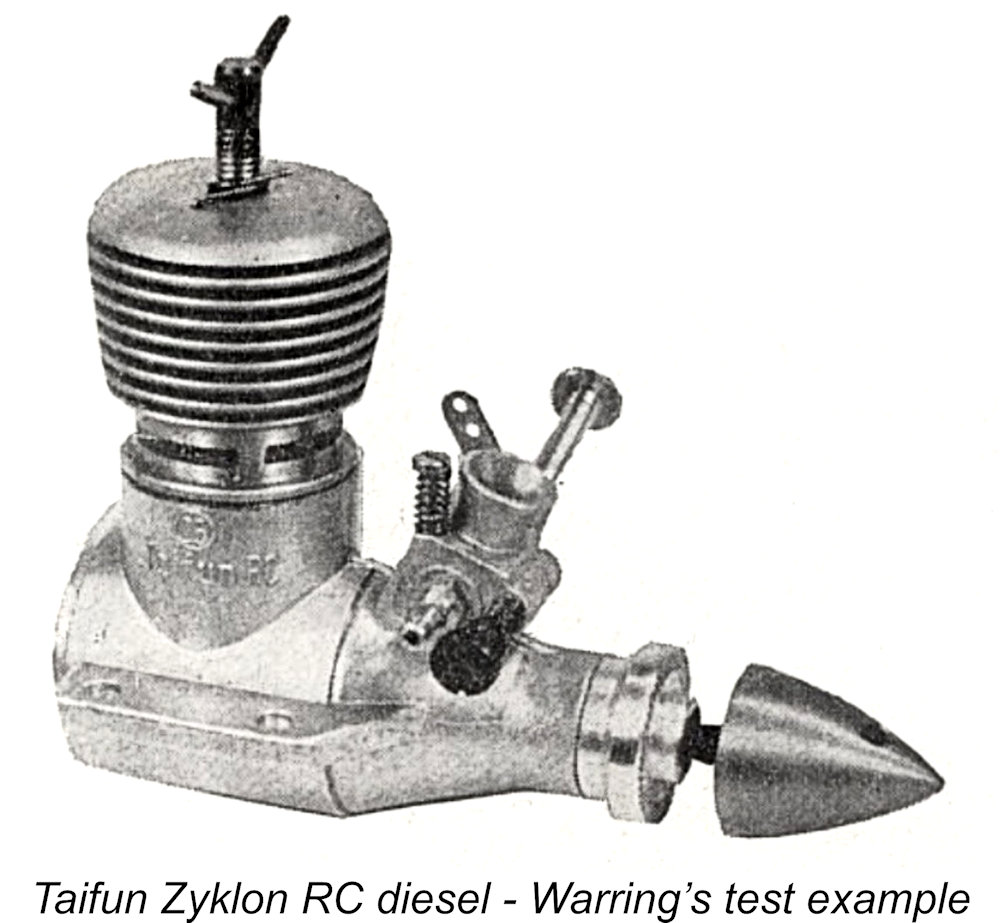

This led to the development of yet another innovation by Hans Hörnlein’s company – a purpose-built 2.5 cc R/C diesel called the Zyklon. This engine appeared in late 1961 or early 1962. No doubt Günther Bodemann had considerable input to this design. At heart, the Zyklon was a completely conventional radially-ported diesel of its era. Nominal bore and stroke were the usual 15 mm and 14 mm respectively for a nominal displacement of 2.47 cc. The engine weighed in at 163 gm (5.75 ounces).

The most unusual feature of the Zyklon was its R/C carburettor, the body of which was cast integrally with the main crankcase/main bearing casting rather than being a separate insert in the more familiar manner. This made it quite clear that the Zyklon was intended from the outset to be used as an R/C powerplant. The designation “2.5 Taifun RC” was cast in relief onto the right-hand side of the upper crankcase, emphasizing this point.

Another innovation which appeared on the Zyklon was the use of a single-turn spring steel wire locking clip which engaged with the compression screw thread. The clip was prevented from turning by a turned-down end which engaged with a small hole in the top surface of the cooling jacket. Warring found this clip to be very effective, viewing it as a step forward from the usual locking lever.

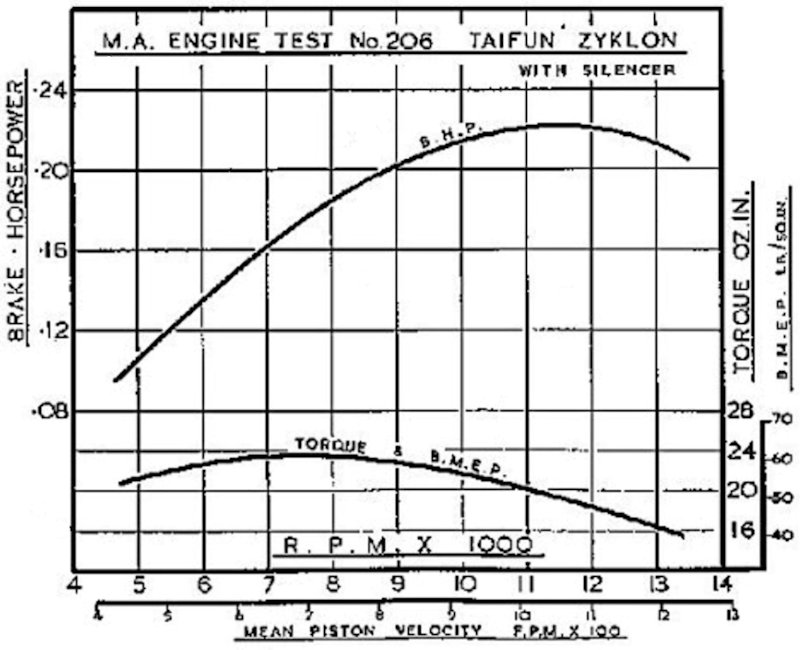

Warring noted that power was “adequate for the job, although rather on the modest side for a modern diesel of this size”. He offset this remark by commenting that with the engine’s modest peaking speed of 12,500 RPM “reasonably large propellers can be used for increased thrust efficiency”. In an R/C context, this is no bad thing. When it came to the operation of the throttle, Warring was rather less complimentary. He commented that despite the thought which had evidently gone into the design of the throttle, “multi-speed performance is strictly limited”. Even with the greatest care in establishing settings, the minimum safe “idling” speed was found to be in the order In terms of ultimate performance, Warring reported an uninspiring peak output of 0.21 BHP @ 12,500 RPM. It’s highly unlikely that this report did much to attract favorable attention to the Zyklon as an R/C powerplant. Despite this, the Zyklon evidently remained in production for some time, becoming the subject of another published test, this time by Peter Chinn, who had now taken over from Ron Warring as the resident engine tester for “Aeromodeller”. Chinn’s report on the Zyklon appeared in the magazine’s August 1965 issue. The main factor which triggered this re-test was the emergence of strict noise control requirements on the part of the Society of Model Aeronautical Engineers (S.M.A.E.), the governing body for British aeromodelling. This led many model engine manufacturers who marketed their products in Britain to develop silencers (aka mufflers) for their engines. Taifun was one of these manufacturers, developing a silencer for the Zyklon. It was primarily to test the effectiveness of this accessory that Chinn conducted his 1965 test. Chinn reprised the description of the engine provided earlier by Warring. He found the engine to be easy to start, with finger-choking alone being the only necessary preliminary. He tried the engine both with and without the silencer, finding that it had very little adverse effect upon performance in the speed range which appeared most appropriate for the engine. His one negative comment was the familiar Taifun complaint that the contra-piston in his In terms of the Zyklon’s throttle response, Chinn had more or less the same experience as Warring before him. He was able to throttle down to 3,500 RPM from a speed of 10,000 RPM, but agreed with Warring that the throttle was best regarded as a two-speed device, with rather indifferent intermediate control. Chinn more or less confirmed Warring’s findings in outright performance terms, finding a peak output of 0.22 BHP @ 11,500 RPM. These figures were obtained with the silencer fitted, whereas Warring had tested the engine in un-muffled form. Despite his various criticisms, Chinn’s summary was generally favourable. He characterized the Zyklon as offering “robust construction, easy handling, a useful power output and adequate throttle control”. He felt that it would be a sound choice for a single-channel operator who needed a reliable two-speed R/C sport engine.

The Zyklon proved to be an excellent starter, also responding very well to both controls. Once adjusted, it ran extremely smoothly. However, I experienced the same issue as Chinn in terms of the contra-piston's tendency to stick in the bore when hot. I also noticed a seemingly significant amount of vibration, doubtless due to the heavy piston. Why it took so long for the Taifun designers to recognize this issue beats me............... Despite this, the engine turned the Tornado 8x6 prop at a dead smooth and steady 10,800 RPM - around 0.256 BHP at that speed. This is well in excess of the outputs reported by both Warring and Chinn at the same speed. I can only assume that my example is another good 'un, either by the luck of the production-line draw or thanks to being better freed up through previous use. Günther Bodemann’s Final Fling with Taifun – the Taifun Orkan

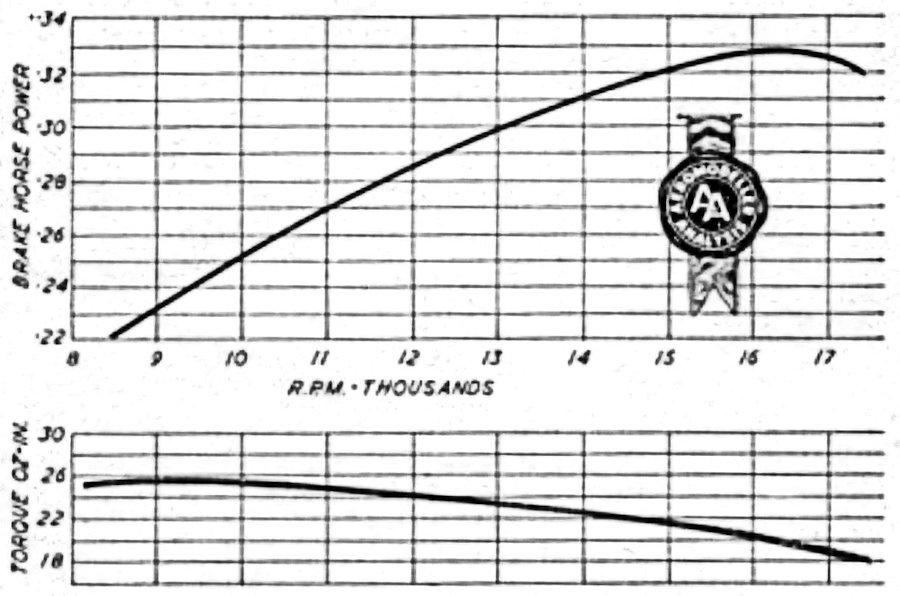

But not before he had completed the design of what many still see as his masterpiece for the Hörnlein company – the Taifun Orkan. This 2.5 cc diesel was really the first Taifun engine which might truly be said to have a genuine “racing” performance. It seems to have appeared in late 1962 or early 1963. The Orkan represented a complete departure from all of the Taifun 2.5 cc diesels which had preceded it. Bore and stroke were the time-honoured 15 mm and 14 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.47 cc. The engine weighed in at 174 gm (6.126 Cylinder porting followed the Oliver pattern almost exactly, including the squared-off upper edges of the transfer ports, which overlapped the exhaust ports almost completely. Uniquely for a Taifun design, the piston was notably light in weight – lesson finally learned! The Orkan featured the neat little spring clip for compression setting retention which had been introduced on the Taifun Zyklon described earlier. The Orkan was the subject of a published test by Ron Warring which appeared in the October 1963 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Warring was generally extremely complimentary in regard to this engine, summarizing it as “a very well-made engine with first-class design and workmanship, and a performance to match”.

Warring reported a peak output of 0.328 BHP @ 16,400 RPM, the latter being a very high figure for a diesel of the period. This level of performance placed the Orkan right near the top of the contemporary 2.5 cc diesel class.

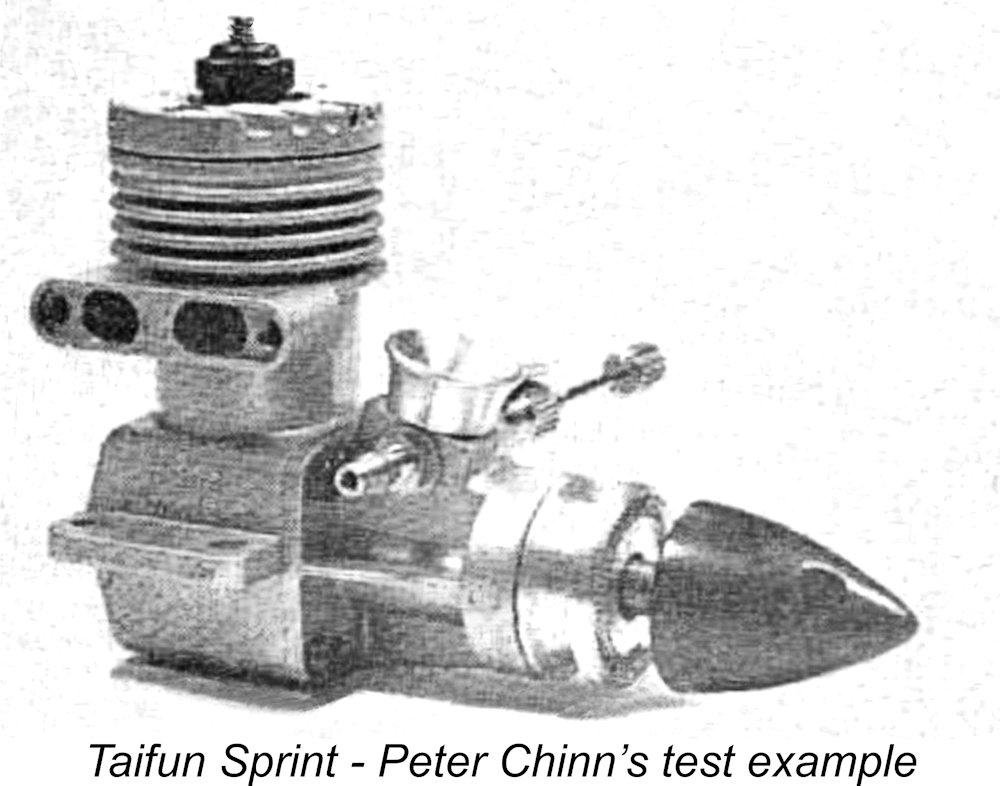

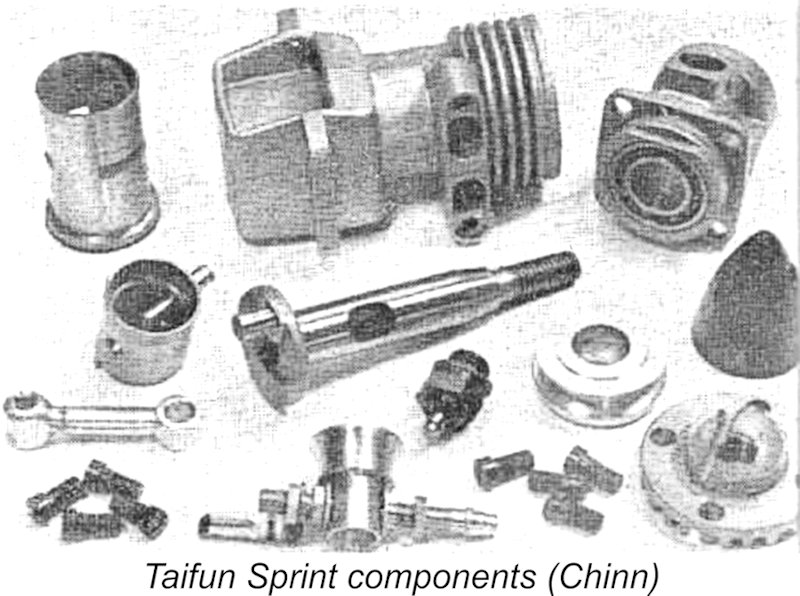

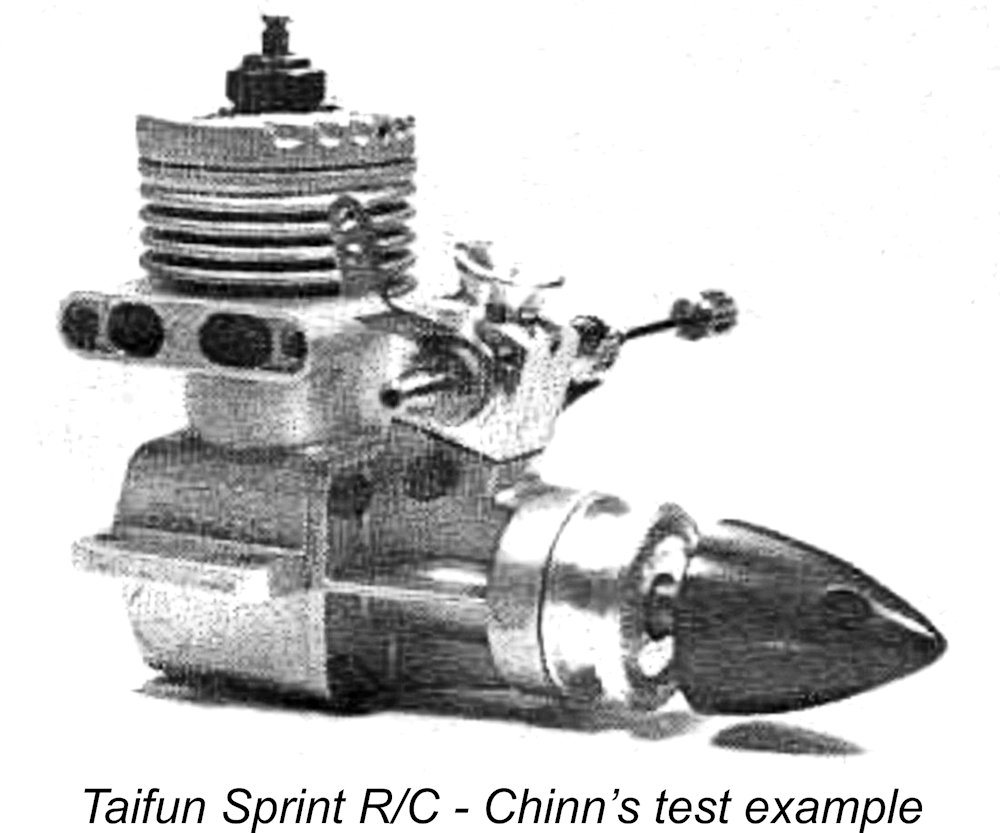

While this was going on, the parent Graupner company was continuing to expand the range and scope of its activities. In 1962, Graupner entered into an association with Grundig, which resulted in the development of their Bellaphon R/C systems. The continued expansion of their business resulted in the construction of a new building in Kircheim unter Teck to accommodate the still-growing company and its business activities. Last Kick at the Can – the Taifun Sprint Glow-Plug Model After the 1962 departure of Günther Bodemann, the pace of development of the Taifun range seems to have stagnated. The 2.5 cc Blizzard was withdrawn in 1963 following the emergence of the Taifun Orkan. Thereafter, no new Taifun models appeared until 1967, when the second and last of the production Taifun glow-plug models made its market debut. This was the 1.79 cc Taifun Sprint, which made its initial appearance at the 1967 Nuremberg Toy Fair.

The Sprint was a basically conventional cross-flow loop scavenged glow-plug motor of its era. It was clearly designed for sport flying as oppose to competition use. Its main departure from the design specifications of its O.S., Webra and Fuji competition was its use of a twin ball-race crankshaft. Bore and stroke of the Sprint were 13.5 mm and 12.5 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.79 cc (0.109 cuin.). The engine turned the scales at a very reasonable 99 gm (3.5 ounces).

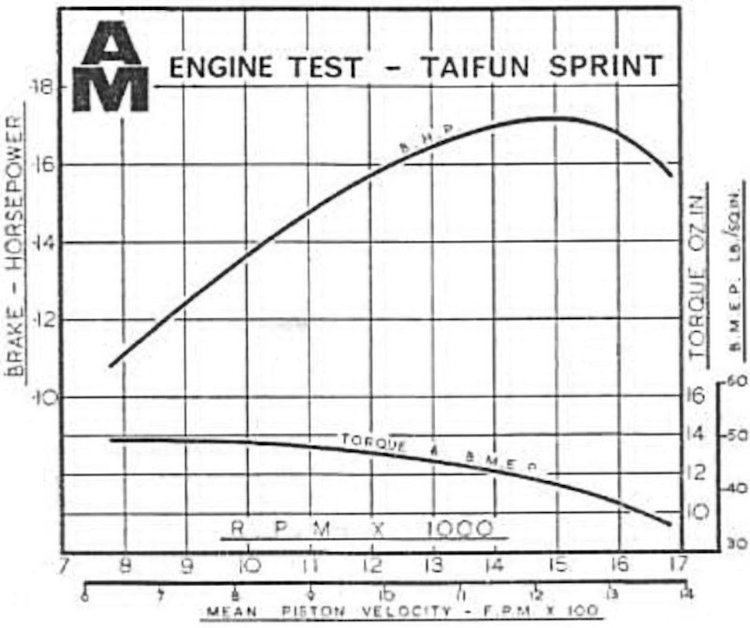

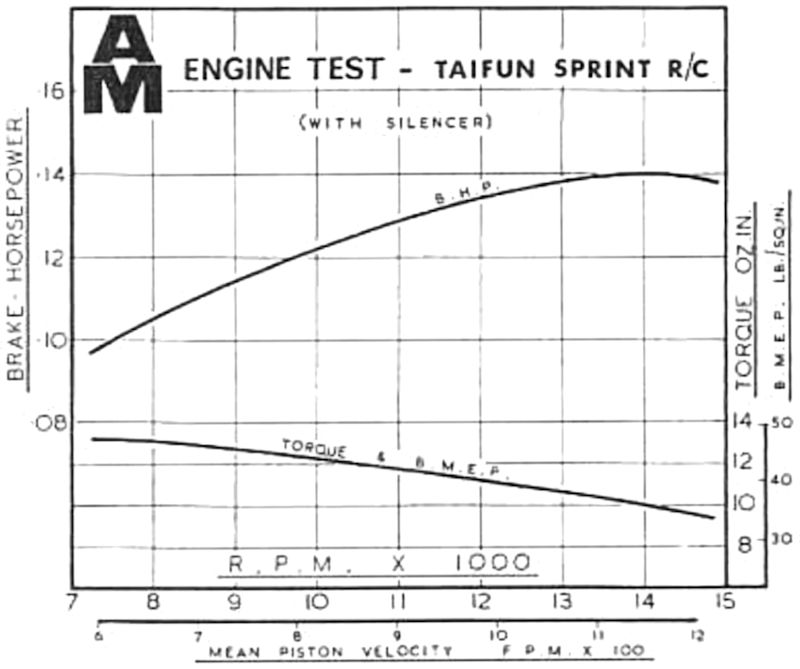

This first test focused upon the unthrottled version of the engine. Chinn described the engine in considerable detail, summarizing the Sprint as “a well-made, nice-handling motor of very good performance”. He found it to be very easy to start, also commenting that it displayed “no unpleasant characteristics whatsoever” during operation.

A greater impact upon performance was felt to result from the Sprint’s use of a 4.5 mm I/D venturi in conjunction with a 2.8 mm dia. spraybar. Chinn believed quite reasonably that this combination would have a considerable adverse effect upon performance. To prove his point, he tried the engine with the venturi insert removed, opening the choke diameter out to 7 mm. Although no actual torque measurements were taken in this configuration, the enhanced prop/RPM figures implied around a 35% increase in peak power output. Point made, I think …………

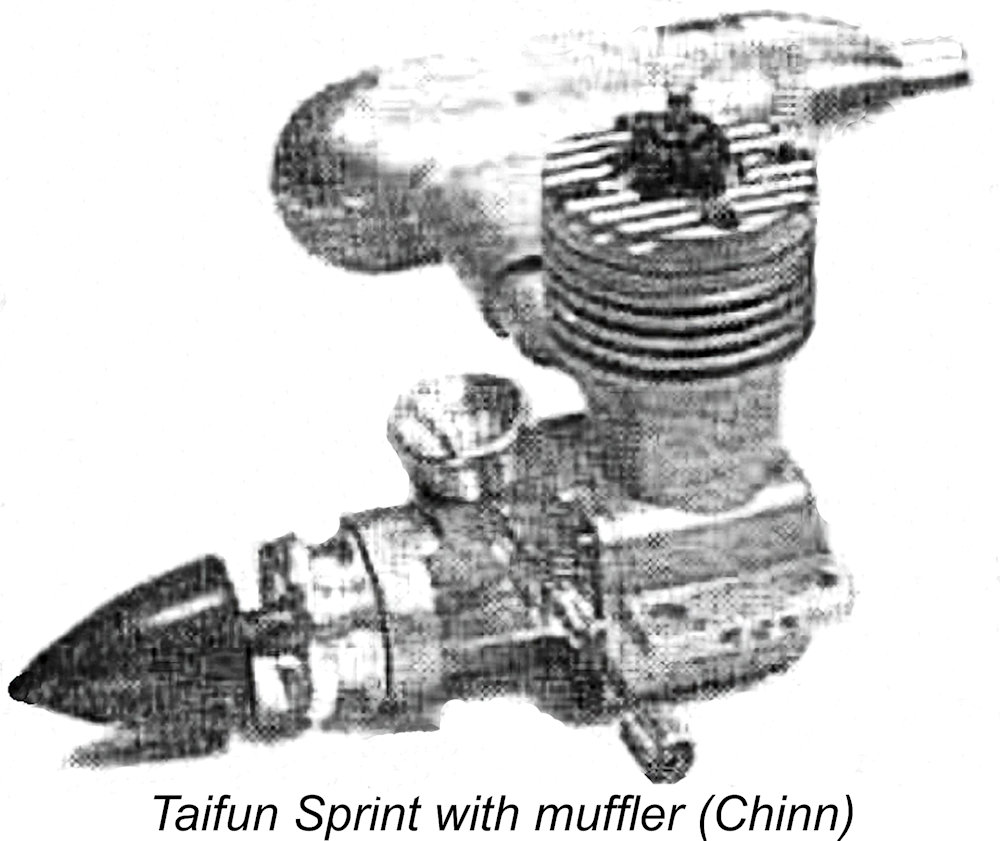

Chinn began by recalling his findings in connection with the standard unthrottled version of the engine some two years earlier. He then turned his full attention to the R/C model. He described the throttle in considerable detail, commenting that the Sprint R/C “throttled really well”. In support of this statement, he reported that using an 8x4 Tornado nylon prop with a fuel containing 5% nitromethane and with the silencer fitted, the engine could be throttled from its fully open speed of 9,900 RPM all the way down to a reliable 2,200 RPM. Starting was said to be very good, with no requirement for an exhaust prime – priming through the intake or by finger choking proved to be adequate. Chinn made no comment on the engine’s The Sprint proved to be the final new model engine to appear under the Taifun brand name. Reading between the lines, it would appear that the parent Graupner company was rapidly losing interest in continuing to develop and promote their long-established model engine “house brand”. They had too many other fish to fry by this time, added to which the sun was clearly beginning to set on the diesels which had constituted the backbone of the Taifun range from the very beginning. As a result, although the range limped on into the 1970’s, it faded progressively in prominence. As far as I’m presently aware, the last Taifun engines were sold in 1976, after which the range disappeared into history. The engines sold during the final few years were almost certainly New Old Stock – manufacture had very likely ceased by 1973. Hörnlein’s Last Stand - the Profi engines One individual who clearly read the writing on the wall was of course Hans Hörnlein. Not wishing to go down with the sinking ship, Hörnlein formally ended his association with Graupner in 1973, intending to strike out on his own with a comprehensively revised range of engines. Since Graupner owned the Taifun name, Hörnlein was not free to use it, choosing instead to continue his operations under the Profi (Ger. Professional) trade-name. He continued to operate from his long-time location at 7917 Lindenstrasse 25 in Vöhringen, West Germany.

The Profi engines were entirely machined from bar stock to very high standards. They were offered in a wide range of displacements - .10, .15, .20, .40, .61, and .74 cuin. All of them were FRV glow-plug models constructed to a common design owing nothing to the Taifun engines which had preceded them. They featured Schnuerle cylinder porting and twin ball bearings along with a silencer system which could be adjusted for its noise reduction effect through the use of inserts. All examples were produced between 1975 and 1977, with approximately 10,000 engines being manufactured during this limited production period. These units were truly beautiful engines with their black cylinder heads, natural-finish polished aluminum cylinders, gold anodized lower cases and black "noses". Somewhat reminiscent of the earlier Cox engines in some ways. Among consumers, the .40 and .61 cuin. models emerged as the most popular choices.

This first ad pictured the 40F and the 6lF R/C with a breakdown of the unique Profi adjustable silencer. The engines were priced from $140 to $180 for the .61 and .74 and were never discounted in the US hobby shops that were fortunate enough to stock them for sale. However, despite their quality they don’t appear to have fared well in the US market. The final ad in MAN appeared in July 1976. A "new" Profi 20 R/C for "aircraft, cars and boats" made just two advertising appearances, in March and April of 1977, before the Profi range seemingly disappeared forever. It’s clear that Hans Hörnlein's single attempt to market his own line of model engines was simply not a success for whatever reason. In 1978 Hörnlein entered into some kind of agreement with the prominent model helicopter manufacturer Dieter Schlüter, for whom he apparently manufactured some special helicopter engines. I have no knowledge of Hörnlein's subsequent activities, nor do I know the extent (if any) to which his German Profi line and the later Profi engines from Ukraine were connected. The Graupner Company – the Later Years It remains for me to summarize the later history of the Graupner company following its disassociation with the Taifun model engine range in the early 1970’s. By that time the company had become a world leader in the development and production of R/C models and equipment, in addition to its distribution activities in connection with the products of other companies. The company maintained its leading position into the early years of the present millennium, still operating from its long-established base at Kirchheim unter Teck, Germany. However, at this point it began to feel the pinch arising from the increasing competition from Asia. When the 2.4 GHz digital transmission technology entered the R/C world beginning in 2005, Graupner reacted too slowly, failing to keep up with its competitors and quickly losing its leadership. The increasing Asian dominance and the various offshore copycat companies with their low prices didn't help Graupner's market position either. As a result, the company became over-extended, eventually entering bankrupcy in 2012. SJ Ltd. of South Korea acquired the Graupner company from receivership, taking over the company with all of its patents, designs, brands and products. SJ Ltd. now changed its name, becoming Graupner Co. Ltd. The original German firm, now a subsidiary, was renamed to Graupner/SJ GmbH, becoming the distributor of its own brands under the control of its parent company. However, the South Korean company also failed to revitalize the Graupner product lines, eventually closing its production facility in Shenzen, China with all development and production to be continued in South Korea at a location near Seoul. Of more significance, the company wound up its distribution chain as well, focusing instead on direct trading. This made the German subsidiary company redundant. Consequently, in 2019 the German Graupner Company announced that it was closing down after 89 years. The company founded by Johannes Graupner in 1930 had been part of the model industry since the beginning, surviving both World War II and the Cold War, but it could not survive the changing market conditions affecting the R/C model industry in the new millennium. Graupner USA in turn announced that they would be shutting down on February 25th, 2020. This shut-down took place as scheduled, although the same people made an attempted come-back as Control Hobbies a few weeks later. Sadly, they didn’t last long either, quickly fading into obscurity. Conclusion

As a closing remark, I should draw your attention to a very informative video which covers the Graupner story from its beginnings up to 2005. Well worth a look! ___________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2025 |

| |

There can be few die-hard model diesel engine aficionados who are not familiar with the name Taifun. This trade-name was applied to a high-quality range of German-made model engines, predominantly diesels, which c

There can be few die-hard model diesel engine aficionados who are not familiar with the name Taifun. This trade-name was applied to a high-quality range of German-made model engines, predominantly diesels, which c

The Graupner company was founded by Johannes Graupner in 1930 in Stuttgart-Wangen when he took over the premises of a former employer. His company operated initially

The Graupner company was founded by Johannes Graupner in 1930 in Stuttgart-Wangen when he took over the premises of a former employer. His company operated initially  In 1935, the company diversified, entering the model aircraft market by introducing its first model glider under the Graubele trade-name. In 1938, the first building plans and materials for scale ship and boat modelling were produced.

In 1935, the company diversified, entering the model aircraft market by introducing its first model glider under the Graubele trade-name. In 1938, the first building plans and materials for scale ship and boat modelling were produced.

The first Taifun diesels were built to a more or less common basic design, although there was some variation in the main bearing and induction configurations. Perhaps most notably, they all featured slip-on alloy cooling jackets which retained the steel cylinders and were secured to the crankcase with three machine screws. These screws passed downward through holes in the cooling fins to engage with tapped holes which were incorporated into three vertical lugs at the top of the case between the exhaust ports.

The first Taifun diesels were built to a more or less common basic design, although there was some variation in the main bearing and induction configurations. Perhaps most notably, they all featured slip-on alloy cooling jackets which retained the steel cylinders and were secured to the crankcase with three machine screws. These screws passed downward through holes in the cooling fins to engage with tapped holes which were incorporated into three vertical lugs at the top of the case between the exhaust ports.

This was a great pity, because the engines were otherwise very well designed and constructed, with good performances by the standards of their day and very low weights for their displacements and specifications. They were produced in four displacements – 1 cc, 1.5 cc, 2.5 cc and 3.5 cc.

This was a great pity, because the engines were otherwise very well designed and constructed, with good performances by the standards of their day and very low weights for their displacements and specifications. They were produced in four displacements – 1 cc, 1.5 cc, 2.5 cc and 3.5 cc. All models used the same porting arrangements consisting of sawn radially-disposed slits. The transfer slits were located below the exhaust port belt which located the cylinder vertically. They were supplied through a bypass formed by the gap between the outer wall of the lower cylinder and the inner wall of the cylinder installation bore in the crankcase. Identical to the system used by the E.D. Racer, for example. This arrangement precluded the provision of any porting overlap, forcing a relatively long blow-down period with a limited transfer duration.

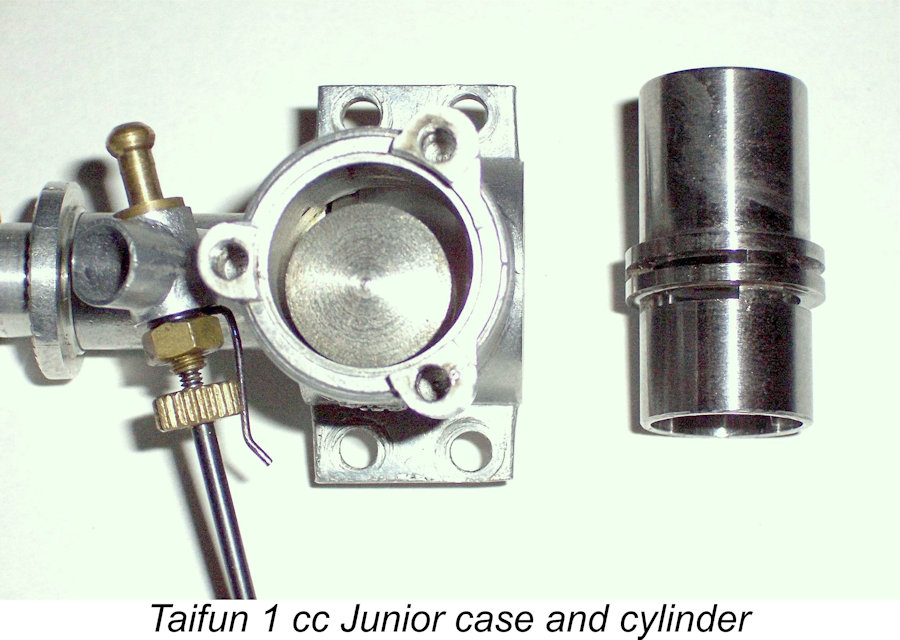

All models used the same porting arrangements consisting of sawn radially-disposed slits. The transfer slits were located below the exhaust port belt which located the cylinder vertically. They were supplied through a bypass formed by the gap between the outer wall of the lower cylinder and the inner wall of the cylinder installation bore in the crankcase. Identical to the system used by the E.D. Racer, for example. This arrangement precluded the provision of any porting overlap, forcing a relatively long blow-down period with a limited transfer duration.  For unknown reasons, the 1 cc Taifun Junior was manufactured in relatively small numbers. It is one of the rarer Taifun models today – good luck finding one! The 2.5 cc Blitz and 3.5 cc Spezial were also manufactured in relatively modest numbers. The other three models were made in somewhat greater numbers, although none of them are particularly common today. To a large extent, this is because the problems mentioned above resulted in their production being terminated in 1954 after less than 18 months. I’ll examine the subsequent models in their place below.

For unknown reasons, the 1 cc Taifun Junior was manufactured in relatively small numbers. It is one of the rarer Taifun models today – good luck finding one! The 2.5 cc Blitz and 3.5 cc Spezial were also manufactured in relatively modest numbers. The other three models were made in somewhat greater numbers, although none of them are particularly common today. To a large extent, this is because the problems mentioned above resulted in their production being terminated in 1954 after less than 18 months. I’ll examine the subsequent models in their place below. One event that must have created something of an upheaval at Graupner at this time was the sudden death in 1953 of company founder Johannes Graupner. His place at the head of the company was taken by his son Max Graupner, who continued the firm’s operations under the Johannes Graupner name. The parent company’s change of management doesn’t appear to have affected the agreement with Hans Hörnlein in any way – he carried on as before. The Graupner company made its first appearance at the prestigious

One event that must have created something of an upheaval at Graupner at this time was the sudden death in 1953 of company founder Johannes Graupner. His place at the head of the company was taken by his son Max Graupner, who continued the firm’s operations under the Johannes Graupner name. The parent company’s change of management doesn’t appear to have affected the agreement with Hans Hörnlein in any way – he carried on as before. The Graupner company made its first appearance at the prestigious  As far as I’m aware, the only example of the “three-bolt head” series to be the subject of a published test in the English language was the 2.47 cc twin ball-race disc-valve Taifun Meteor “Rennmotor Spezial” (Special Racing Motor). This model featured bore and stroke dimensions of 15 mm and 14 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.47 cc. It weighed in at a fairly substantial 175 gm (6.2 ounces)

As far as I’m aware, the only example of the “three-bolt head” series to be the subject of a published test in the English language was the 2.47 cc twin ball-race disc-valve Taifun Meteor “Rennmotor Spezial” (Special Racing Motor). This model featured bore and stroke dimensions of 15 mm and 14 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.47 cc. It weighed in at a fairly substantial 175 gm (6.2 ounces) Response to the needle valve was characterized as being “smooth and progressive”, with mixture settings being held securely. However, the compression control was found to be less user-friendly. The steel contra-piston was fitted too tightly, seizing in the bore as soon as the engine warmed up a little. While not a major problem in service with the same prop and fuel, where running compression adjustments are generally not required, this made the testing of the engine more challenging than it would have been otherwise. This is actually a not-uncommon characteristic of diesels fitted with steel contra-pistons unless these are perfectly fitted at the outset.

Response to the needle valve was characterized as being “smooth and progressive”, with mixture settings being held securely. However, the compression control was found to be less user-friendly. The steel contra-piston was fitted too tightly, seizing in the bore as soon as the engine warmed up a little. While not a major problem in service with the same prop and fuel, where running compression adjustments are generally not required, this made the testing of the engine more challenging than it would have been otherwise. This is actually a not-uncommon characteristic of diesels fitted with steel contra-pistons unless these are perfectly fitted at the outset.  While not delivering a stellar performance by early 1954 standards, the tested engine did give a reasonably good account of itself, being at least on par with a number of British 2.5 cc diesels of the same period. This report undoubtedly served the Graupner cause by creating a positive initial impression of the Taifun range. The report also acknowledged the existence of the 3.5 cc “Spezial” model, which was a bored and stroked version of the disc-valve Meteor "Spezial Rennmotor".

While not delivering a stellar performance by early 1954 standards, the tested engine did give a reasonably good account of itself, being at least on par with a number of British 2.5 cc diesels of the same period. This report undoubtedly served the Graupner cause by creating a positive initial impression of the Taifun range. The report also acknowledged the existence of the 3.5 cc “Spezial” model, which was a bored and stroked version of the disc-valve Meteor "Spezial Rennmotor".  As mentioned earlier, the original Taifun 1 cc model, the Taifun Junior, had been made in very small numbers, evidently being viewed as unworthy of continued production. Nonetheless, Graupner clearly want to have a model in this very popular beginner/sport displacement category.

As mentioned earlier, the original Taifun 1 cc model, the Taifun Junior, had been made in very small numbers, evidently being viewed as unworthy of continued production. Nonetheless, Graupner clearly want to have a model in this very popular beginner/sport displacement category. The externally-threaded screw-in steel cylinder was made quite thick below the exhaust port belt, allowing the use of four internal flutes in the cylinder walls to serve as both bypass and transfer ports. Exhaust chores were handled as before by four sawn slits machined into the exhaust port belt. The bypass flutes terminated some distance below the exhaust ports, once again restricting the transfer period significantly. A black-anodized screw-on cooling jacket topped the cylinder. The rest of the engine was quite conventional, warranting no detailed description here.

The externally-threaded screw-in steel cylinder was made quite thick below the exhaust port belt, allowing the use of four internal flutes in the cylinder walls to serve as both bypass and transfer ports. Exhaust chores were handled as before by four sawn slits machined into the exhaust port belt. The bypass flutes terminated some distance below the exhaust ports, once again restricting the transfer period significantly. A black-anodized screw-on cooling jacket topped the cylinder. The rest of the engine was quite conventional, warranting no detailed description here. Another new Taifun model introduced at this time was the 2.47 cc Tornado, a twin ball-race FRV diesel which was clearly intended to replace the earlier three-bolt Meteor. This model used the same revised screw-in cylinder design as that seen on the companion Hobby, but featured a twin ball-race crankshaft. Bore and stroke were the Continental standard 15 mm and 14 mm respectively. The engine weighed 144 gm (5.08 ounces), a very modest figure for a 2.5 cc twin ball-race diesel and a considerable reduction from the 175 gm (6.2 ounces) of its RRV Meteor Rennmotor predecessor.

Another new Taifun model introduced at this time was the 2.47 cc Tornado, a twin ball-race FRV diesel which was clearly intended to replace the earlier three-bolt Meteor. This model used the same revised screw-in cylinder design as that seen on the companion Hobby, but featured a twin ball-race crankshaft. Bore and stroke were the Continental standard 15 mm and 14 mm respectively. The engine weighed 144 gm (5.08 ounces), a very modest figure for a 2.5 cc twin ball-race diesel and a considerable reduction from the 175 gm (6.2 ounces) of its RRV Meteor Rennmotor predecessor.  dimensions were amended significantly. The Rasant was a long-stroke engine featuring bore and stroke dimensions of 14 mm and 16 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.46 cc. It weighed in at a very light 106 gm (3.74 ounces), making it one of the very lightest 2.5 cc diesels of them all.

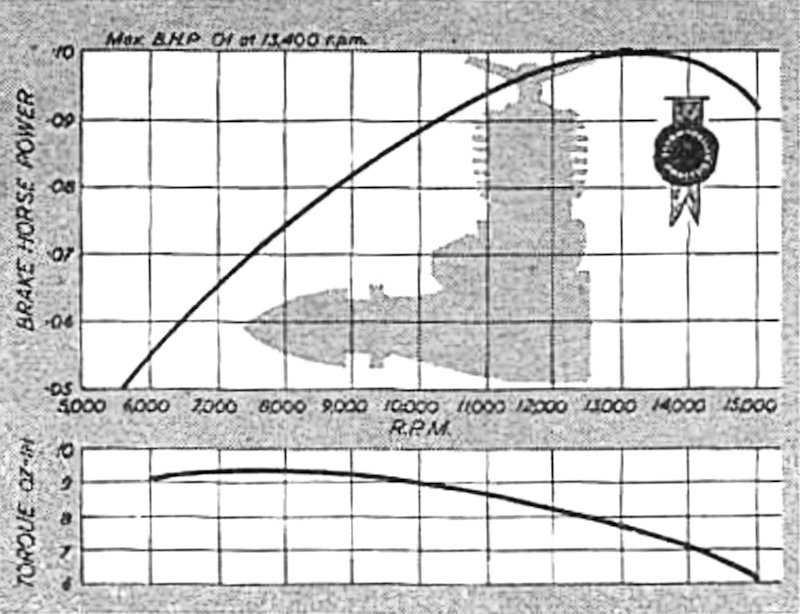

dimensions were amended significantly. The Rasant was a long-stroke engine featuring bore and stroke dimensions of 14 mm and 16 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.46 cc. It weighed in at a very light 106 gm (3.74 ounces), making it one of the very lightest 2.5 cc diesels of them all. In terms of performance, Warring characterized the Hobby as being “quite a high speed and exceptionally powerful engine.” While admitting that the test example was probably still not completely run-in when tested, he reported a peak output of exactly 0.100 BHP @ 13,400 RPM. This was indeed an outstanding performance for a 1 cc diesel of 1954 vintage – the even more powerful

In terms of performance, Warring characterized the Hobby as being “quite a high speed and exceptionally powerful engine.” While admitting that the test example was probably still not completely run-in when tested, he reported a peak output of exactly 0.100 BHP @ 13,400 RPM. This was indeed an outstanding performance for a 1 cc diesel of 1954 vintage – the even more powerful  doubtless contributed to this behavior, since contra-pistons of this material have a well-known tendency to seize in steel bores unless perfectly fitted. Regardless, this made it “impossible to secure precise adjustment for this engine”. As a result, Warring cautioned that the reported performance data should be viewed as “not necessarily the best that this engine can produce”.

doubtless contributed to this behavior, since contra-pistons of this material have a well-known tendency to seize in steel bores unless perfectly fitted. Regardless, this made it “impossible to secure precise adjustment for this engine”. As a result, Warring cautioned that the reported performance data should be viewed as “not necessarily the best that this engine can produce”.

The models just described had replaced the original Taifun Junior, Blitz and Meteor respectively. However, the 1.5 cc displacement category had been unrepresented in the Taifun range since the withdrawal of the 1.5 cc three-bolt Record in 1954. This changed with a vengeance in mid-1956 with the appearance of a completely revised 1.5 cc diesel – the famous Taifun Hurrikan.

The models just described had replaced the original Taifun Junior, Blitz and Meteor respectively. However, the 1.5 cc displacement category had been unrepresented in the Taifun range since the withdrawal of the 1.5 cc three-bolt Record in 1954. This changed with a vengeance in mid-1956 with the appearance of a completely revised 1.5 cc diesel – the famous Taifun Hurrikan. The reed valve used by Hörnlein in the Hurrikan bore a strong resemblance to that used earlier by Aerol Engineering. Interestingly, two reeds were used in each engine, having thicknesses of 0.003 in. and 0.005 in. respectively. These reeds were stamped from hard brass rather than the more usual copper-beryllium.

The reed valve used by Hörnlein in the Hurrikan bore a strong resemblance to that used earlier by Aerol Engineering. Interestingly, two reeds were used in each engine, having thicknesses of 0.003 in. and 0.005 in. respectively. These reeds were stamped from hard brass rather than the more usual copper-beryllium. made recipe for metal fatigue failure.

made recipe for metal fatigue failure.  induction. Perhaps even more importantly, the feature has the great advantage of "releasing" the reed from crankcase pressure effects well before top dead centre is reached, thus giving the reed plenty of time to snap back into place on its sealing annulus before the sub-piston induction closes on the power stroke and crankcase pressurization begins.

induction. Perhaps even more importantly, the feature has the great advantage of "releasing" the reed from crankcase pressure effects well before top dead centre is reached, thus giving the reed plenty of time to snap back into place on its sealing annulus before the sub-piston induction closes on the power stroke and crankcase pressurization begins. In performance terms, Chinn described the handling characteristics of the engine as “quite satisfactory”, although starting was apparently “not exactly first-flick”. Both controls were said to be “satisfactory in operation”, with settings being held securely at all speeds. Running qualities were said to be good, with running being “quite remarkably smooth” in the engine’s preferred 13,000 – 16,000 RPM range. Chinn cautioned potential users that the Hurrikan was definitely a high-speed engine which should not be operated at speeds below 12,000 RPM.

In performance terms, Chinn described the handling characteristics of the engine as “quite satisfactory”, although starting was apparently “not exactly first-flick”. Both controls were said to be “satisfactory in operation”, with settings being held securely at all speeds. Running qualities were said to be good, with running being “quite remarkably smooth” in the engine’s preferred 13,000 – 16,000 RPM range. Chinn cautioned potential users that the Hurrikan was definitely a high-speed engine which should not be operated at speeds below 12,000 RPM. Despite these production shortcomings, Warring was clearly just as impressed with the Hurrikan as Chinn had been. He stated that “starting characteristics throughout were excellent”, with finger-choking alone being the only necessary preliminary to an instant start. He had nothing but praise for the engine’s running characteristics, particularly at the top end, describing its performance at the upper end of the speed range as “quite fantastic”.

Despite these production shortcomings, Warring was clearly just as impressed with the Hurrikan as Chinn had been. He stated that “starting characteristics throughout were excellent”, with finger-choking alone being the only necessary preliminary to an instant start. He had nothing but praise for the engine’s running characteristics, particularly at the top end, describing its performance at the upper end of the speed range as “quite fantastic”. Hörnlein’s efforts resulted in the mid-1957 appearance of the Taifun RS Hobby, in essence a reed valve version of the well-established Hobby of 1954. This engine used the same piston/cylinder configuration as the FRV Hobby (which continued in production), but featured a new crankcase casting and crankshaft along with a comprehensively-revised backplate which accommodated the reed valve.

Hörnlein’s efforts resulted in the mid-1957 appearance of the Taifun RS Hobby, in essence a reed valve version of the well-established Hobby of 1954. This engine used the same piston/cylinder configuration as the FRV Hobby (which continued in production), but featured a new crankcase casting and crankshaft along with a comprehensively-revised backplate which accommodated the reed valve. It appears that the casting die for the crankcase somehow became damaged after only about 500 examples of the RS Hobby had been produced. Consequently, this variant is among the rarer Taifun engines today. The manufacturer took advantage of the need to rework the die to make a few changes, notably a reduction in the external diameter of the upper crankcase into which the cylinder screwed. While he was at it, he also changed the engine’s cast-on identification from the RS Hobby to the Hobby RS.

It appears that the casting die for the crankcase somehow became damaged after only about 500 examples of the RS Hobby had been produced. Consequently, this variant is among the rarer Taifun engines today. The manufacturer took advantage of the need to rework the die to make a few changes, notably a reduction in the external diameter of the upper crankcase into which the cylinder screwed. While he was at it, he also changed the engine’s cast-on identification from the RS Hobby to the Hobby RS. Warring did what he could for the manufacturer. He stated that “starting and general running characteristics were found to be very good”. However, he could only report a peak output of 0.071 BHP @ 12,000 RPM, well below reported figures for the FRV Hobby. This led him to express the view that the Hobby RS was “disappointing in power output, for the whole design looked far more promising than the result actually achieved”.

Warring did what he could for the manufacturer. He stated that “starting and general running characteristics were found to be very good”. However, he could only report a peak output of 0.071 BHP @ 12,000 RPM, well below reported figures for the FRV Hobby. This led him to express the view that the Hobby RS was “disappointing in power output, for the whole design looked far more promising than the result actually achieved”.  Given Bodemann’s long-standing association with the Webra range, it caused quite a stir in the German modelling community when in 1958 Bodemann left the employ of Webra bosses Martin Bragenitz and Martin Eberth to go to work for Hans Hörnlein’s company at Vöhringen. This represented a major relocation for Bodemann, since Vöhringen is located some 650 km south of Berlin.

Given Bodemann’s long-standing association with the Webra range, it caused quite a stir in the German modelling community when in 1958 Bodemann left the employ of Webra bosses Martin Bragenitz and Martin Eberth to go to work for Hans Hörnlein’s company at Vöhringen. This represented a major relocation for Bodemann, since Vöhringen is located some 650 km south of Berlin. The first new Taifun model to appear following the arrival of Günther Bodemann was a completely new model, the 2.47 cc reed-valve Taifun Blizzard. This model introduced a completely new Taifun crankcase style which imparted a somewhat bullet-like streamlined appearance to the engines. It appeared in late 1958, implying that Bodemann had wasted no time in getting to work.

The first new Taifun model to appear following the arrival of Günther Bodemann was a completely new model, the 2.47 cc reed-valve Taifun Blizzard. This model introduced a completely new Taifun crankcase style which imparted a somewhat bullet-like streamlined appearance to the engines. It appeared in late 1958, implying that Bodemann had wasted no time in getting to work.  The Blizzard featured a twin ball-race crankshaft allied to a reed valve of identical design to that used so successfully on the Hurrikan but less so on the Hobby RS. Apart from the crankcase configuration, the main observable difference was that the remote needle valve was now carried in a dome-shaped alloy housing instead of the angular Cox-style fitting used on the original Hurrikan. An identical change was made to the Hurrikan’s carburettor at the same time, although the Hurrikan’s crankcase continued unchanged.

The Blizzard featured a twin ball-race crankshaft allied to a reed valve of identical design to that used so successfully on the Hurrikan but less so on the Hobby RS. Apart from the crankcase configuration, the main observable difference was that the remote needle valve was now carried in a dome-shaped alloy housing instead of the angular Cox-style fitting used on the original Hurrikan. An identical change was made to the Hurrikan’s carburettor at the same time, although the Hurrikan’s crankcase continued unchanged.

Ron Warring of “Aeromodeller” wasted no time in going into print with a

Ron Warring of “Aeromodeller” wasted no time in going into print with a  The one fly in the ointment was the engine’s marked predilection towards the development of excessive vibration throughout the speed range. This was doubtless due to the use of a very heavy piston along with a crank-disc which was completely un-counterbalanced. It’s a little surprising that a designer of Bodemann’s calibre would have let this pass – vibration is a massive power robber.

The one fly in the ointment was the engine’s marked predilection towards the development of excessive vibration throughout the speed range. This was doubtless due to the use of a very heavy piston along with a crank-disc which was completely un-counterbalanced. It’s a little surprising that a designer of Bodemann’s calibre would have let this pass – vibration is a massive power robber. It was left to Peter Chinn of “Model Aircraft” to set the record straight. Somewhat oddly, Chinn waited until January 1963 to publish his

It was left to Peter Chinn of “Model Aircraft” to set the record straight. Somewhat oddly, Chinn waited until January 1963 to publish his  Just out of curiosity, I put my own early Blizzard number 1490 into the test stand and gave it a few runs on an APC 8x6 airscrew. This is a used but cosmetically perfect example which is extremely well freed up. The engine proved to be a very easy starter and a superb runner. On the APC 8x6 prop it managed 11,700 RPM, indicating an output of some 0.282 BHP at that speed. This is well in excess of the 0.25 BHP which Chinn's test example developed at the same speed.

Just out of curiosity, I put my own early Blizzard number 1490 into the test stand and gave it a few runs on an APC 8x6 airscrew. This is a used but cosmetically perfect example which is extremely well freed up. The engine proved to be a very easy starter and a superb runner. On the APC 8x6 prop it managed 11,700 RPM, indicating an output of some 0.282 BHP at that speed. This is well in excess of the 0.25 BHP which Chinn's test example developed at the same speed.

The cylinders of both models were also changed. The Rasant-II received the same heavier cylinder with modified port timing that had been featured on the Blizzard. This meant that the former long-stroke geometry was now abandoned, the engine featuring the same 15 mm bore and 14 mm stroke as the Blizzard. Presumably this standardization of cylinders represented a quite rational production economy measure.

The cylinders of both models were also changed. The Rasant-II received the same heavier cylinder with modified port timing that had been featured on the Blizzard. This meant that the former long-stroke geometry was now abandoned, the engine featuring the same 15 mm bore and 14 mm stroke as the Blizzard. Presumably this standardization of cylinders represented a quite rational production economy measure. Naturally, there was a price to pay for the adoption of the new cylinder designs. The weight of the Rasant-II was increased to 144 gm (5.08 ounces) from the Rasant-I’s figure of 106 gm (3.74 ounces), while the Hobby-II turned the scales at 90 gm (3.17 ounces) – an increase of 27 gm over the original Hobby’s weight of 63 gm (2.22 ounces). These increases were clearly seen as an acceptable trade-off for the improved performances of the two models.

Naturally, there was a price to pay for the adoption of the new cylinder designs. The weight of the Rasant-II was increased to 144 gm (5.08 ounces) from the Rasant-I’s figure of 106 gm (3.74 ounces), while the Hobby-II turned the scales at 90 gm (3.17 ounces) – an increase of 27 gm over the original Hobby’s weight of 63 gm (2.22 ounces). These increases were clearly seen as an acceptable trade-off for the improved performances of the two models.

The initial result of this decision was the development by Hörnlein and Bodemann of a small glow-plug engine to be called the Taifun Foxie. It appears that the decision to develop this engine may have been taken by Hörnlein and Bodemann following insufficient consultation with their Graupner associates.

The initial result of this decision was the development by Hörnlein and Bodemann of a small glow-plug engine to be called the Taifun Foxie. It appears that the decision to develop this engine may have been taken by Hörnlein and Bodemann following insufficient consultation with their Graupner associates. So far, so good, and the manufacture of components for the Foxie commenced, along with the production of a batch of boxes for the engine. Components and boxes for some 250 examples were apparently completed. Graupner actually got as far as including the Foxie in their “Aeromodeller” advertising placement of July 1960 as seen below at the left.

So far, so good, and the manufacture of components for the Foxie commenced, along with the production of a batch of boxes for the engine. Components and boxes for some 250 examples were apparently completed. Graupner actually got as far as including the Foxie in their “Aeromodeller” advertising placement of July 1960 as seen below at the left. However, it was at this point that Graupner suddenly developed a severe case of cold feet – they decided belatedly that they weren’t interested in marketing the Foxie after all! This attitude may have resulted from a perception that the visual similarity of the Foxie to the Cox models would have an adverse effect upon sales of each brand, since the two Graupner brands (Taifun and Cox) would be competing against each other. Alternatively, the engine may have under-performed, or manufacturing costs may have been found to be uneconomically high. We’ll never know …………….