|

|

The E.D. Greenhead Racer

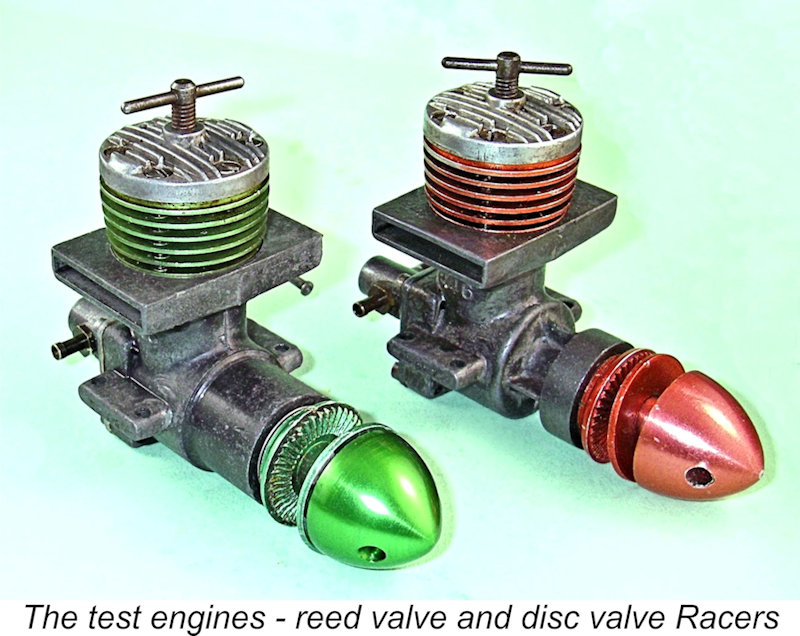

I think that you’d be hard-pressed to find a true model diesel aficionado who was not familiar with the red-jacketed disc rear rotary valve twin ball-race E.D. Racer. That iconic model is one of the best-documented and most widely-used model diesel designs dating from the 1950’s. By contrast, the fact that there was also a green-jacketed reed valve version of the same engine seems to be one of the better-kept secrets handed down to us from the fifties. In this article I’ll attempt to describe the differences between the two models as well as their similarities. I’ll top it off with a comparative bench test of the two variants. Before getting started, I must acknowledge the fact that it would be quite impossible to write with any authority on the subject of any E.D. product without drawing upon the wealth of knowledge and experience of this marque held by my good mate Kevin Richards. Since there’s no question at all that Kevin is the world authority on E.D., I freely admit that I couldn’t have completed this task without his always-valued advice and assistance. Thanks, mate!! I would be most remiss if I did not also thank my valued Aussie mate Gordon Beeby for undertaking yet another diligent search of his magazine collection for references to the reed valve Racer. Although the advertising record of this engine is non-existent, Gordon was able to find a number of media references which did much to shed light on the history of this interesting adaptation. Much appreciated! Now, in order to get things moving, we have to review a little background. Background

Those who have read my earlier article will be aware that E.D. first challenged the 2.5 cc diesel category with their crankshaft front rotary valve 2.49 cc Mk. III model of March 1948. That engine was a useful-enough performer by the standards of its day, although latter-day tests have demonstrated quite conclusively that its designer missed a number of simple and easily-implemented improvements which would have enhanced its performance to a significant degree.

In order to bring an updated model into being, the company turned to the well-known model engineer Basil Miles. Although the earliest E.D. “stovepipe” models, including the Mk. III, seem to have been designed primarily by a fellow named Charlie Cray, it seems all but certain that Cray’s good friend and fellow hydroplane racing club-mate Basil Miles had been associated with the E.D. engines all along in an advisory capacity. Indeed, Miles had reportedly been instrumental in persuading E.D. management to enter the model engine field in the first place.

Accordingly, it appears that the design rights to the early E.D. models designed by Charlie Cray remained with the company, since the engines were designed by their employee. Miles may well have had input to the later variants (the Comp Special and Mk. III) but any such work would have been undertaken in the capacity of an outside consultant – E.D. would have retained ownership of the designs. However, this changed as E.D. began increasingly to turn to Miles to guide the development of their later designs. At some stage, the relationship between Miles and E.D. appears to have developed to the point at which the ownership of the new designs remained with Miles rather than being transferred to E.D. The It’s a little unclear exactly when this arrangement took effect. The design of the 1 cc E.D. Bee Mk. I diesel of mid 1948 certainly bears a strong imprint of Miles’ design style, but his name was never cited as the designer of that model. Nor indeed was it ever mentioned in connection with the 3.46 cc E.D. Mk. IV Hunter which appeared in late 1949. Despite this, it seems all but certain that Basil Miles was actually the primary designer of the Mk. IV. Although E.D. themselves never attached Miles’ name to the Hunter, it appears that the Hunter design originated with Basil, who evidently retained ownership of the design. He is seen in the accompanying image testing one of these engines.

The fact that E.D. never credited Basil Miles with the design of the E.D. Mk. IV Hunter seems to have rankled somewhat with Basil. Accordingly, it would appear that a stipulation of his agreement to design the The new model in question was of course the main subject of this article – the iconic 2.46 cc E.D. Mk. III Racer diesel. Development of this model took place in 1950, with at least one barstock prototype being constructed. As of 2024 the illustrated example of this prototype was in the care of Steve Betney, who supplied the image. The Series 1 version of this disc rear rotary valve masterpiece was introduced in production form in March 1951 to supplant the fading front rotary valve E.D Mk. III which had first appeared in March 1948. The Racer was destined to become one of the most successful and widely-used 2.5 cc diesels of the 1950’s.

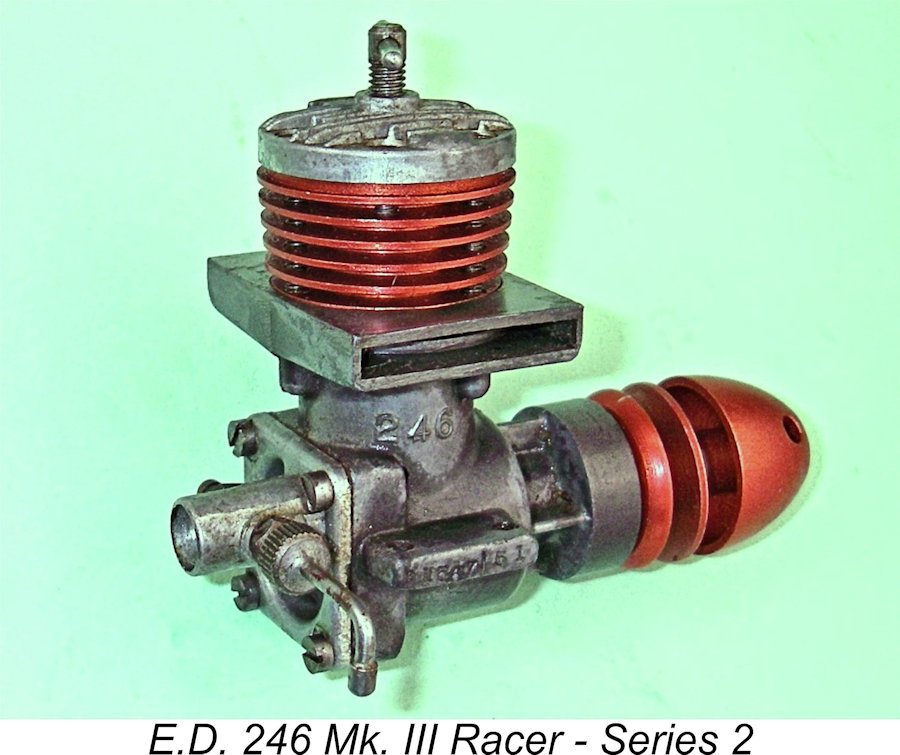

The original Series 1 variant of the E.D Racer featured a main bearing housing which was completely unbraced. This design was presumably found wanting, because a modification which appeared only months later in late 1951 was the addition of stiffening webs to the main bearing housing to produce the Series 2 variant. The engine was otherwise unchanged. This version of the Racer was the subject of a published test by Peter Chinn which appeared in the March 1952 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Chinn was equally unstinting in his praise for the engine, more or less duplicating Sparey’s earlier findings by reporting a peak output of 0.265 BHP @ 13,800 RPM. The E.D. Racer's Contest Record

By contrast, the spark ignition conversions are vanishingly rare, suggesting that the kits didn't attract much market interest. The only example of which I'm aware is owned by Steve Betney, who provided the accompanying image.

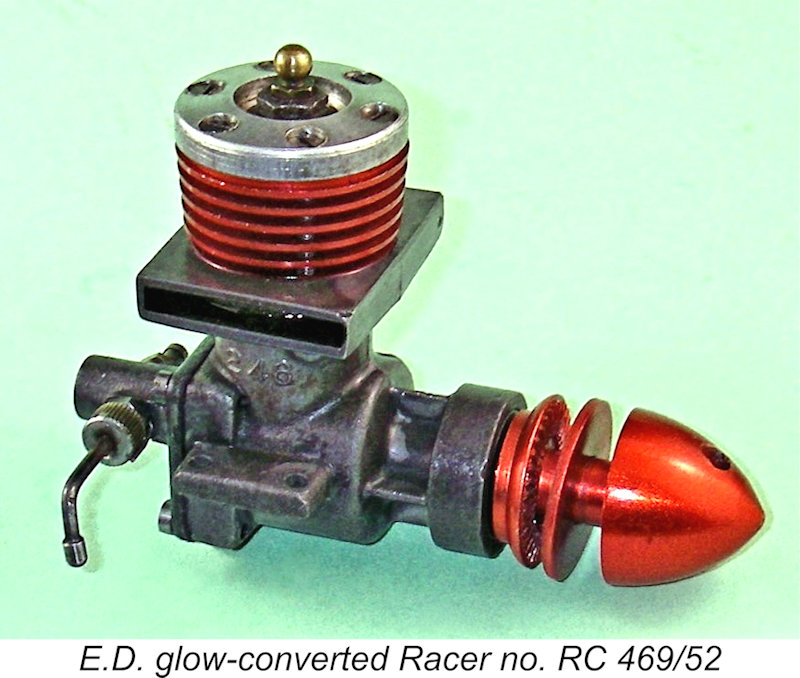

Disc valve glow-plug versions of the Racer achieved considerable success in the control-line speed event. A number of owners had considerable success in tuning them for better performance. The glow-plug unit in my possession which is illustrated below at the left has been very intelligently modified by some previous owner, with very good results - it's a great runner!

Wright topped even this performance later in 1954, further raising the British 2.5 cc record to 113.30 mph (182.33 km/hr). Some going for a 1951 radially-ported engine which hadn’t been designed as a glow-plug model in the first place! However, things did not go so well for Wright a year later at the 1955 World Control Line Speed Championships held near Paris, France in early July, 1955. Still using his E.D. Racer glow-plug motor, Wright could only manage a speed of 99.4 mph (159.96 km/hr) at that meeting, good for tenth place. If he had been able to duplicate his best 1954 performance, he would have won handily! From an E.D. publicity standpoint, that blow was softened somewhat by an October 1955 performance by Benny Hansen of Copenhagen, who managed an official speed of 186 km/hr (115.52 mph) in his native Denmark. As well as setting a new Danish 2.5 cc record, this speed would have given Hansen first place at the 1955 World Control-Line Speed Championship, and by a considerable margin. As far as I'm aware, this was the highest speed ever recorded officially by one of these motors, and a very creditable one too. Whichever way you slice it, the Racer in both diesel and glow-plug versions was unquestionably E.D.'s all-time most successful contest engine. The E.D. Racer in Team Racing

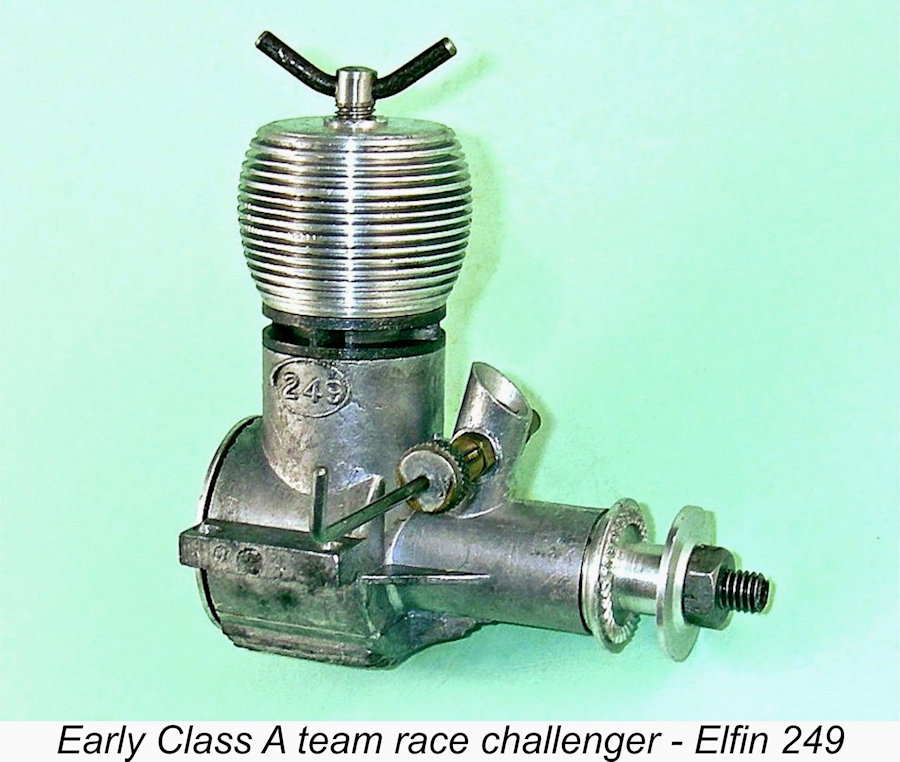

By comparison with the Elfin, the Racer suffered from two disadvantages – it was appreciably heavier, and it was considerably more thirsty. Nevertheless, its durability, superior performance and outstanding handling led to its being increasingly adopted as the 2.5 cc diesel of choice for the Class A team race event. Dick Edmond's Racer-powered Class A team race win at the 1952 British Nationals underscored the engine's status. By the 1953 season the Racer had achieved clear dominance in Class A, setting the standard for some years. Dick Edmonds had switched to Oliver Tiger Mk. II power for the '53 season, winning the British Nationals once more. However, the other two finalists were both using E.D. Racers. Norman Butcher's Racer-powered "Sorcerer's Apprentice" was reportedly the fastest model among the three finalists, but a blocked fuel line put paid to his chances in the final. Although the late 1953 introduction of the Oliver Tiger Mk. III provided some very stiff opposition from the 1954 season onwards, the Racer’s lower price and far greater availability allowed it to maintain a dominant position in the entry lists for the period – many competitors either couldn’t afford an Oliver or couldn't afford to wait for one.

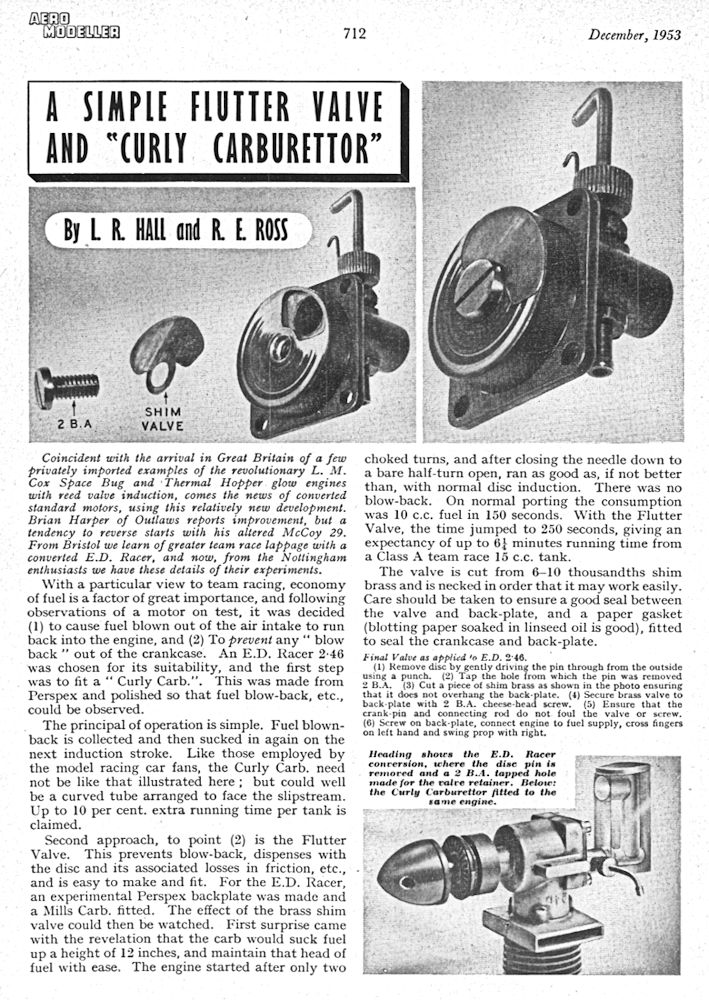

To get around this disability, it became increasingly common for team race entrants to convert their Racers to reed valve induction. With a well-designed reed valve, fuel losses due to blow-back through the induction system were minimized at all practical speeds. As a bonus, the modification also eliminated the friction and viscous drag losses associated with the disc valve. It's clear that considerable experimentation was undertaken by Racer-powered team race competitors during 1953. The modification received a boost from the publication of a "how to" article by L. R. Hall and R. E. Ross which appeared in the December 1953 issue of "Aeromodeller". Their design was very easily implemented, but resulted in a considerable increase in crankcase volume as a result of the elimination of the disc. It also gave rise to some obvious potential for fatigue failures of the reed itself. Even so, the arrangement appears to have worked OK. They claimed a significant improvement in the engine's fuel economy due to the virtual elimination of fuel losses through blow-back. The article mentioned that reed valve experiments had also been undertaken with the McCoy 29 glow-plug motor that was widely used in Class B team racing. However, the problem of re-starting in reverse was an issue with that powerplant. Another interesting inclusion in this article was the so-called "Curly Carb". This was an ingenious if cumbersome arrangement for trapping blown-back fuel and recycling it through the engine.

In his "Model Talk" column in the May 1954 issue of "Model Aircraft", Bill Dean let the cat out of the bag by confirming that Basil Miles was then experimenting with reed valve induction, reportedly with "marked success". Interestingly enough, Miles informed Dean that the reed valve system "would most likely be applied to the Hunter 3.46 as an alternative to the standard disc valve induction". In actual fact, this never happened, at least in production terms. At this point, it's necessary to digress momentarily in order to clarify one matter of considerable importance for the historical record. Aerol Engineering are often credited with having been the first British manufacturer of model diesels to employ the reed valve principle in their Elfin ball-race models which first began to The extent to which E.D. actually produced the reed-valve versions of the Racer in series at this early stage is a little unclear. It appears that their early involvement with reed valve induction was confined to supplying a few examples of reed valve Racers on a field-testing basis – they certainly never advertised such variants. In addition, some owners having the required capabilities doubtless continued to create their own reed valve conversions. One such individual was M. R. Downes of Dereham in Norfolk, who began experimenting with reed valve conversions of the Racer in early 1954. Downes published details of his conversion in a letter to the Editor of "Model Aircraft" which appeared in the magazine's March 1955 issue. The evident acceptance of the reed-valve E.D. Racer was not confined to Britain. Indeed, the engine appears to have enjoyed considerable success overseas. In his "Foreign Notes" column in the November 1954 issue of "Model Airplane News" (MAN), Peter Chinn noted that the then well-known Queensland team race competitor Col Somers had recently entered the fray with an E.D. 2.46 cc Racer diesel which had been converted to reed valve induction. Whether this was a factory unit or a home conversion was not made clear. Regardless, Chinn's informant Arthur Gorrie stated that the model was both fast and economical. At a time when most Aussie competitors were getting around 22 laps to a tank, Somers was reportedly getting up to 40 laps at competitive speeds.

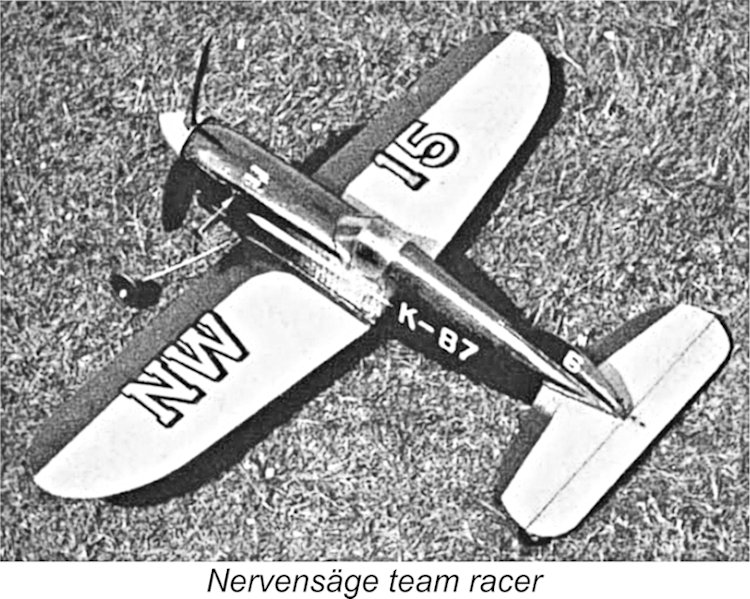

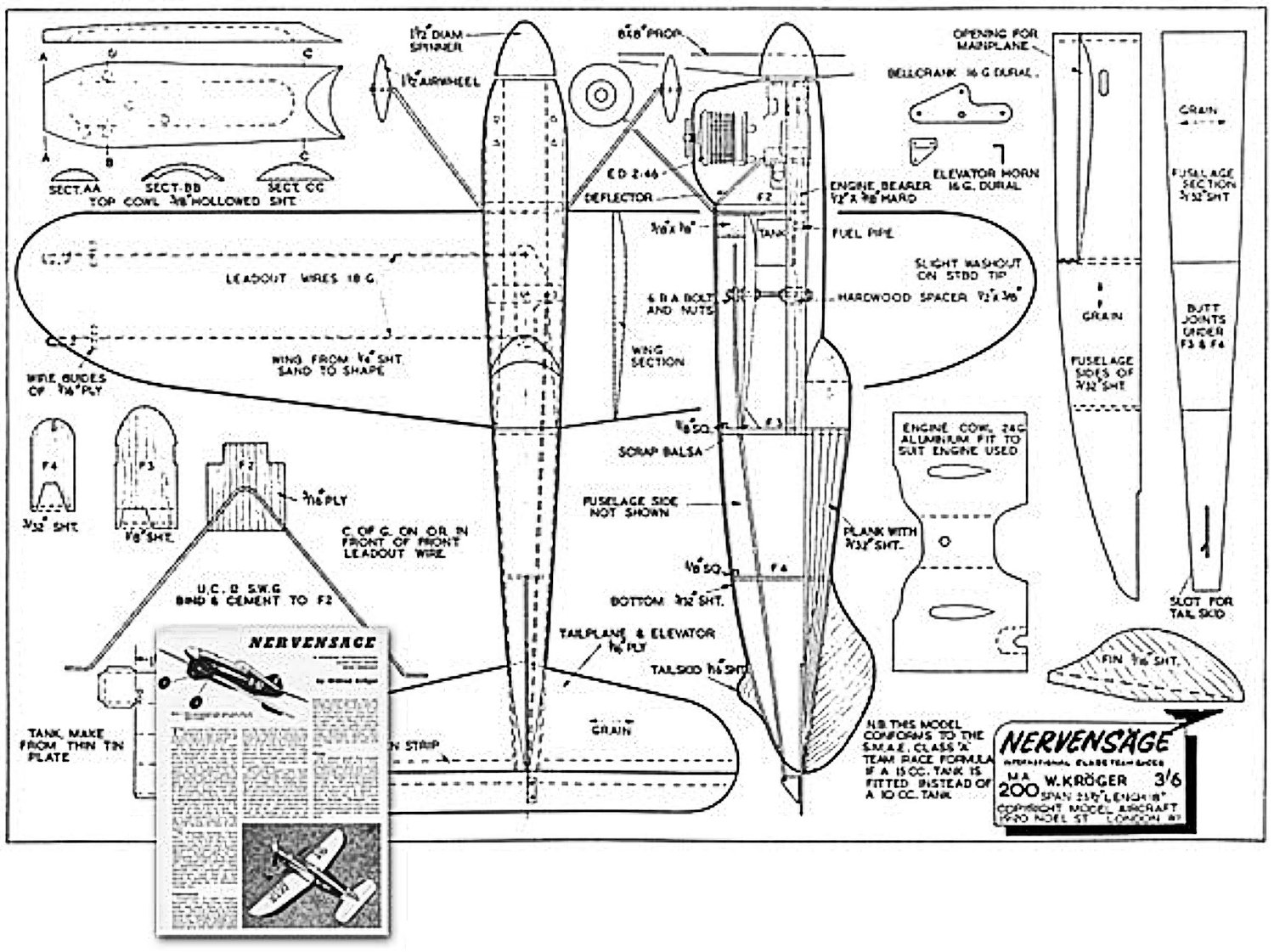

A review of the history of this model/motor combination is quite revealing. The prototype was designed in 1953 according to S.M.A.E. Class A rules, winning every contest in which it was entered during that year apart from a fine second place in the 5th Criterium of Europe meeting held in September 1953 at Soesterberg in Holland. In this contest it was beaten only by H. Longdot of Belgium, who was also using a reed-valve E.D. Racer.

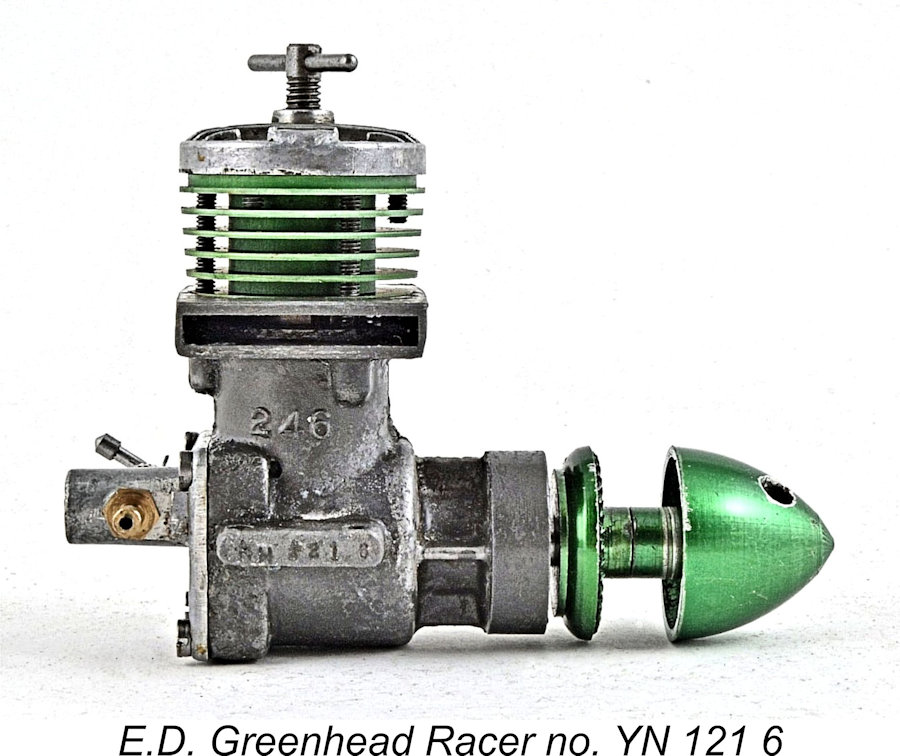

The designer of the Nervensäge claimed that the lappage potentially achievable using these reed valve Racers could be as much as double that attainable using the standard disc-valve variant. The model was An 8x8 FROG plastic airscrew was used with this engine. If latter-day tests are anything to go by (see below), such a load would have restricted the engine's operating speed quite significantly, although fuel consumption would have been much improved. It was clearly seen as being worthwhile to sacrifice speed for range. With a rotary valve engine like the standard Racer or the Webra, range with a 10 cc tank was typically around 25 laps, but with a well-adjusted reed valve Racer the range could be extended to some 40 laps. This allowed the model to complete the 120 lap 10 km final on only two pit stops as opposed to the three or even four stops required by the rotary valve opposition. The consequent advantage was often sufficient to offset any shortfall in model speed. This extra range allowed the reed valve Racer to remain competitive far longer than one might have expected. Even as late as 1956, all of five years after the Racer's introduction, that year’s Criterium of Europe meeting at Etterbeek featured an exciting final in which the winning Dutch team's reed-valve E.D. By 1956 all this success had persuaded E.D. management that the reed valve Racer was well worthy of inclusion on the production books, even if only at a rather modest level and on a special-order basis. The photographically-attested existence of reed valve Racer no. YN 121 6 confirms that limited numbers of this model were undoubtedly being produced by the factory as of December 1956. The reed valve Racer offered no performance advantage over the standard disc valve model – its sole edge lay in its significantly lower fuel consumption resulting from the virtual elimination of fuel losses through induction blow-back. As a result, its appeal was pretty much confined to the team race community, many of whom could not afford an Oliver but could stretch to the cost of the E.D.

Oddly enough, although they never promoted the reed valve Racer in any way, the company's spare parts service did recognize the existence of this model. Kevin Richards reported that components relating specifically to the reed valve Racer were included in E.D.'s spare parts catalogue from 1957. The reed valve E.D. Racers sold by the company in ready-to-run form were supplied in standard E.D. Racer boxes. The boxes used for these engines were distinguished from those used for the standard disc-valve models solely by having a strip of green green adhesive tape fixed to the rear top edge of the box.

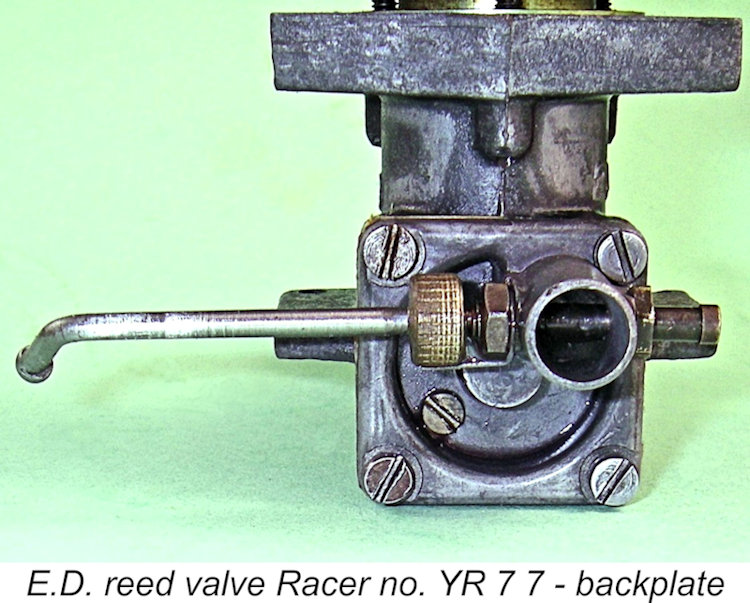

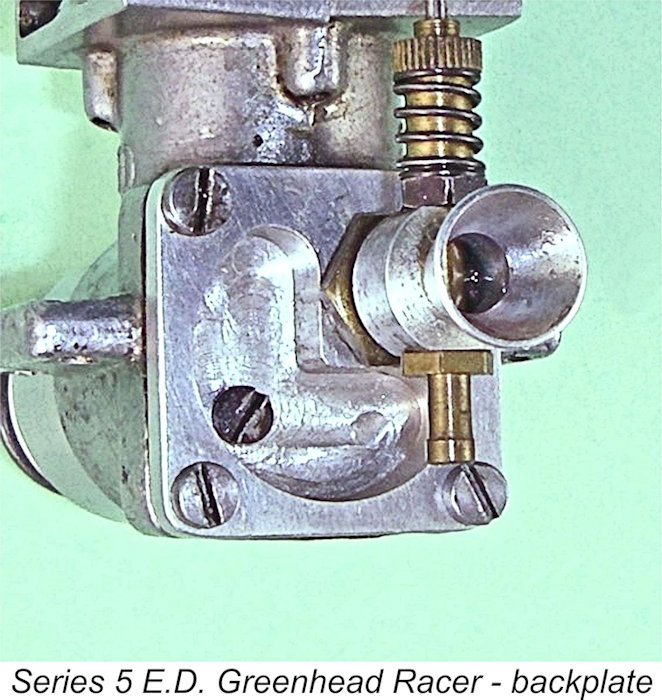

The reed valve used in the Greenhead Racer (as I will call it henceforth) and in the later Fury 1.46 cc derivative was a very practical and well thought-out design. Assuming that Basil Miles was justified in asserting his ownership of the Racer design and his right to approve any and all changes to that design, he must surely be credited with the design of the E.D. reed valve. The reed valve backplate started life as a standard disc valve component. However, the central boss was left undrilled since the installation of the disc valve bearing pin was no longer required. Instead, a hole was drilled The provision of means for limiting the deflection of the reed was a very good idea. There were a number of contemporary reports to the effect that the reeds used in many of the “home-made” reed valve set-ups had very short lives, sometimes even failing during the pre-race warm-up. Looking at some of the published designs, I find it hard to be surprised at this! In all other respects, the Greenhead Racer was identical to its familiar Redhead disc valve companion, hence requiring no detailed description here. In fact, if it wasn’t for the green-anodized components, the reed valve Racer would be externally indistinguishable from its disc valve progenitor unless one looked very attentively at the backplate. The E.D. Greenhead Racer - Serial Numbers The issue of originality of a given example of the E.D. Greenhead Racer is settled decisively by the serial numbers attached to the respective models. The disc valve units bear serial number sequences which begin with the model identification letter R, while the original factory-produced reed valve examples bear sequences which begin with the letter Y. This is a sure-fire way to distinguish between a factory reed valve Racer and an owner conversion of a disc-valve model. They do exist ……… As always, I'm greatly indebted to my good mate Kevin Richards for the provision of the vast majority of the serial numbers in my current database. The reported numbers of which I'm currently aware are as follows: YN121 6 - Series 2 braced magnesium case - December 1956 YA 167/7 - Series 3 large-diameter main bearing magnesium case - January 1957 YE188/7 - Series 3 large-diameter main bearing magnesium case - May 1957 YE 50/8 - known only from a factory-stamped box - May 1958 YE 71/8 - glowplug conversion - Series 3 unbraced large-diameter main bearing magnesium case - May 1958 YF33/8 - Series 3 unbraced large-diameter main bearing magnesium case - June 1958 YJ 7/8 - Series 4 aluminium unbraced large-diameter main bearing - September 1958 YN8/8 - Series 4 aluminium unbraced large-diameter main bearing - December 1958 YB19/9 - Series 4 aluminium unbraced large-diameter main bearing - February 1959 YN 3/9 - glowplug conversion - Series 4 aluminium unbraced large-diameter main bearing - December 1959 YF 8/A - Series 4 aluminium unbraced large-diameter main bearing - June 1960

During the writing of this article I approached my good mate Kevin Richards to get his take on these anomalies. Kevin began by stating his opinion that the 0 in Peter Valicek's number was actually a poorly-struck 8 or 9 - E.D. never began their batch numbers with a 0. If Kevin's right, that was one hell of a batch by reed valve Racer standards! With respect to the R batch letter, Kevin commented that he had seen a few other E.D. engines displaying this letter, but confirmed that E.D. never intentionally used it in their batch sequences. He was quite sure that this letter was intended to be a B or perhaps an E, and the chap who did the striking suffered from poor eyesight! It appears likely that the same chap did the striking on both engines, since they appear to be from the same batch. While not representing a sufficiently large sample to support any authoritative estimate of production figures, these numbers do confirm that the Greenhead Racer was produced almost continuously in modest numbers from late 1956 through to mid-1960 as a minimum. A small but steady demand is undoubtedly indicated. Even with the seemingly modest monthly batch numbers, the total number produced must surely have run into the multiple thousands. It remains a complete mystery why E.D. didn't promote this model! The major remaining question requiring an answer is – how well did it perform? Let’s find out! The Greenhead and Redhead Racers Compared

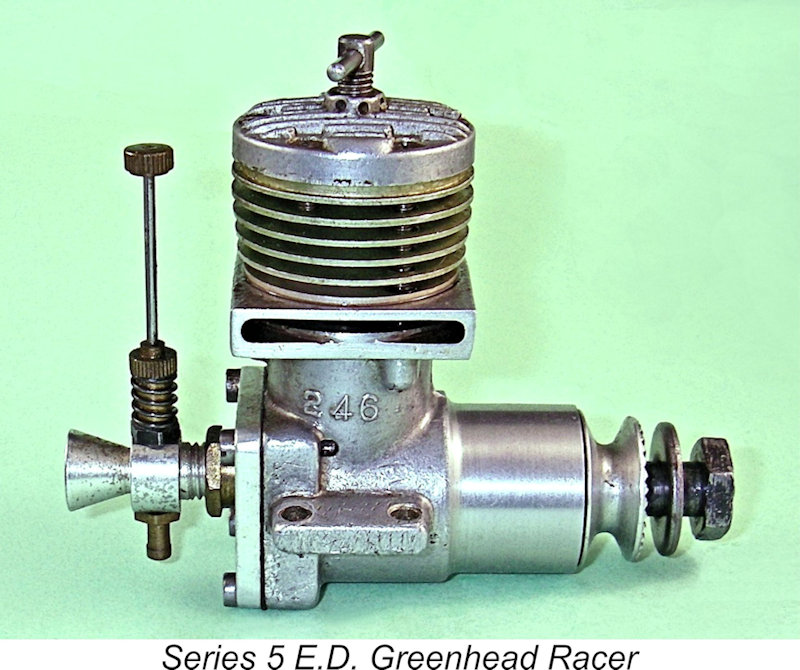

Both engines feature magnesium alloy castings – the switch to aluminium alloy castings apparently came later in early 1958. However, the disc valve example retains the webbed main bearing housing which was first introduced in November 1951, while the reed valve model features the large-diameter unbraced cylindrical main bearing housing which was introduced in early 1957. It appears that there was some overlap between the case styles, since left-over stocks of the braced cases evidently continued to be built up into complete engines even after the revised case first appeared.

I was also very interested in gaining some impression of the two engines' relative rates of fuel consumption, since it was this criterion which prompted the production of the reed valve Racer in the first place. To derive some information on that topic, I provided myself with a classic 10 cc metal fuel tank which would allow me to time a run using the same amount of fuel in each case. My planned approach was to run a tank through the engine in order to establish the optimal setting and get the engine good and hot, then re-fill the tank and re-start the hot engine at running settings. I would then time the second run. This would more or less duplicate the conditions encountered during a team race event.

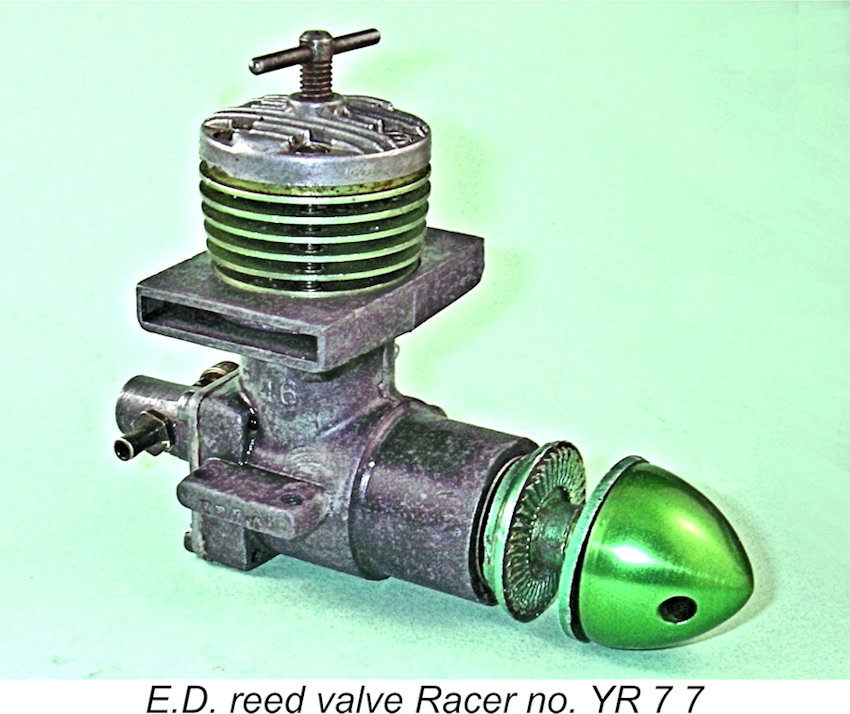

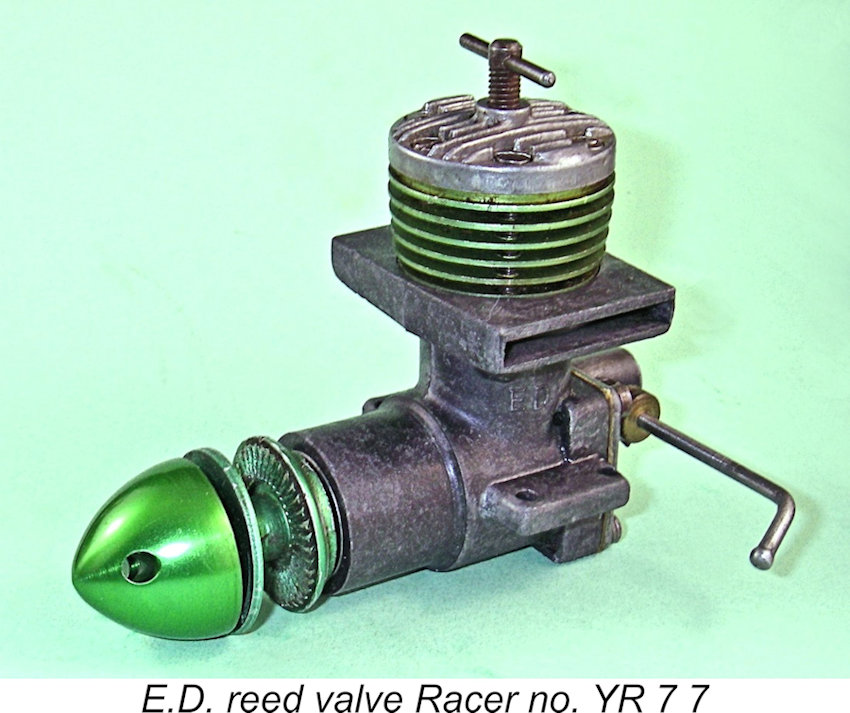

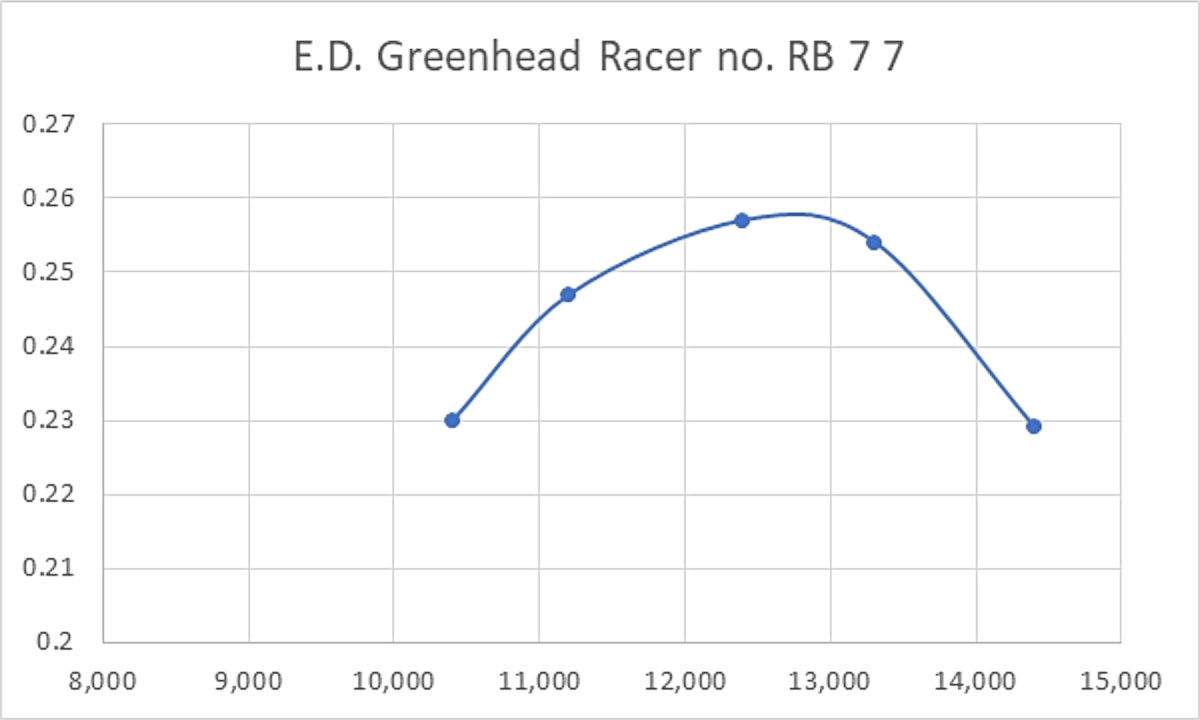

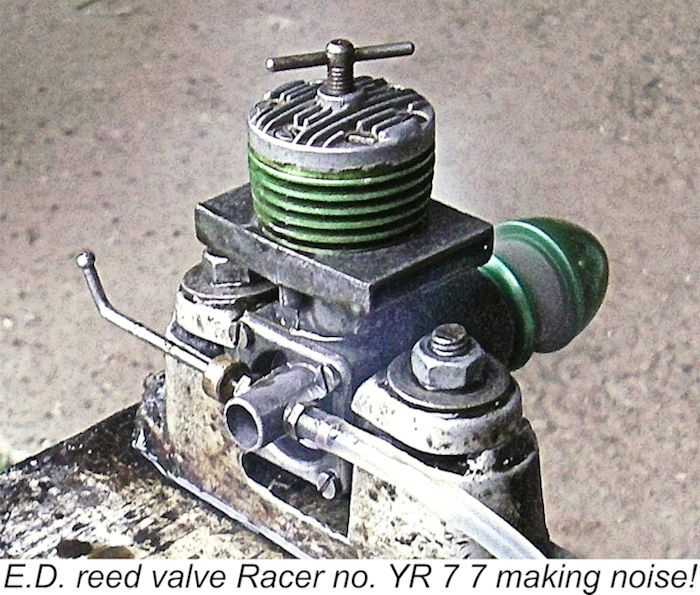

After obtaining figures for all five of my selected props, I ran the timing test on my 10 cc test tank, making a couple of timed runs. It turned out that the tank was a poorly-constructed accessory - experimentation showed that over 1 ml of fuel remained in the tank even Then it was the turn of Greenhead Racer no. YR 7 7 which was presumably intended to be numbered YB 7 7. This engine handled just as well as its disc valve companion, starting easily and running very smoothly at all times with minimal vibration. It actually surprised me by showing little or no tendency to start backwards - the classic bugbear of the reed valve motor. During the entire test period it only made one reverse start when I inadvertently got it a little too wet. The only handling characteristic of note was the usual reed valve tendency to exhibit a slightly delayed response to adjustments of the needle valve. I ran the same suite of five test props on the Greenhead, also conducting the timed tank runs as before using the APC 8x4 prop. The results were quite instructive, as represented in the data below.

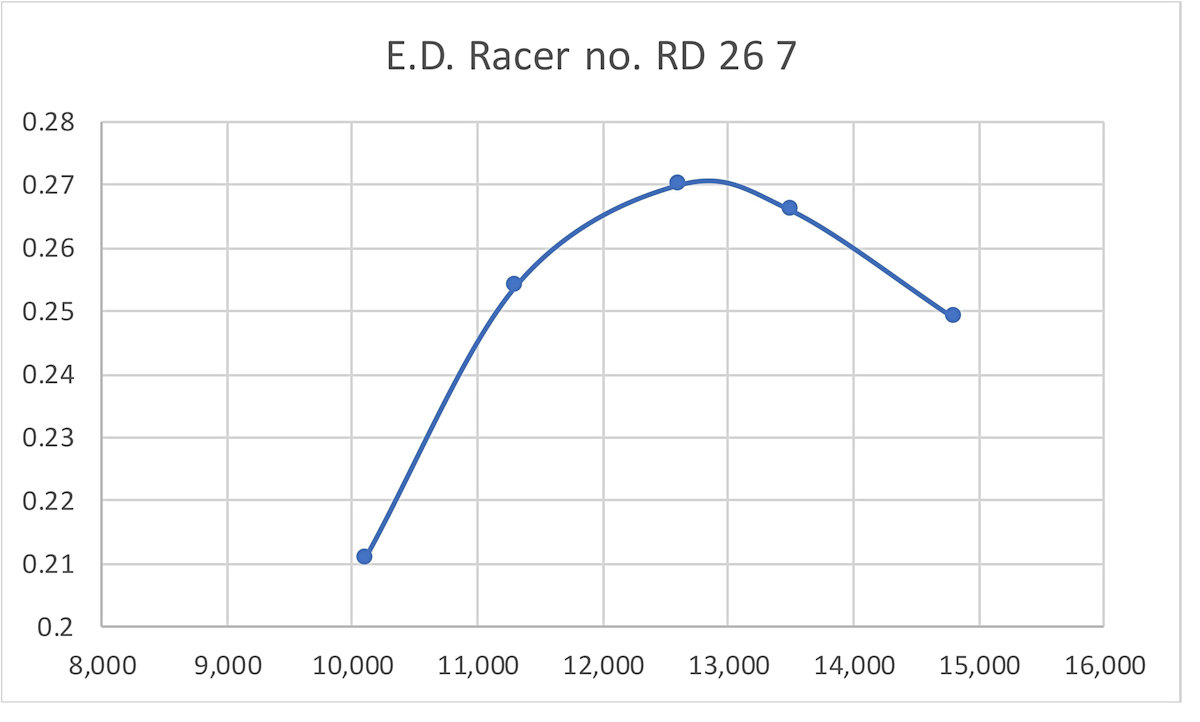

As the above data confirm, the two engines performed at surprisingly comparable levels! The disc valve model slightly outperformed its reed valve companion, developing around 0.271 BHP @ 12,900 RPM as opposed to the reed valve model's 0.258 BHP @ 12,800 RPM. We would expect this, since if the reed valve model had out-performed the disc valve model, E.D. would almost certainly have switched to it as their main offering. As it was, the reed valve model gave relatively little away to its disc valve counterpart.

Still, the conditions were the same for both engines, so the playing field was level! In the fuel consumption sweepstakes, it was no contest - the reed valve Racer won hands down! Following a hot restart at running settings on a full tank, the disc valve example managed a run time of 61 seconds using this tank and fuel, while the reedy stretched its run out to 79 seconds. Not perhaps as great an advantage as some of the published claims might lead us to expect, but there's no question that the virtual elimination of blow-back using Basil Miles' excellent reed valve design really paid dividends in terms of fuel economy. Moreover, the difference would be even more marked at lower speeds, at which the disc valve model would be significantly more prone to blow-back. All of this makes it pretty clear why the reed valve Racer achieved the wide acceptance that it did among team race competitors of the early to mid-1950's. It gave away nothing in terms of handling and very little in terms of performance, while delivering a level of fuel economy that few if any competing 2.5 cc diesels could match. The Series 5 E.D. Greenhead Racer

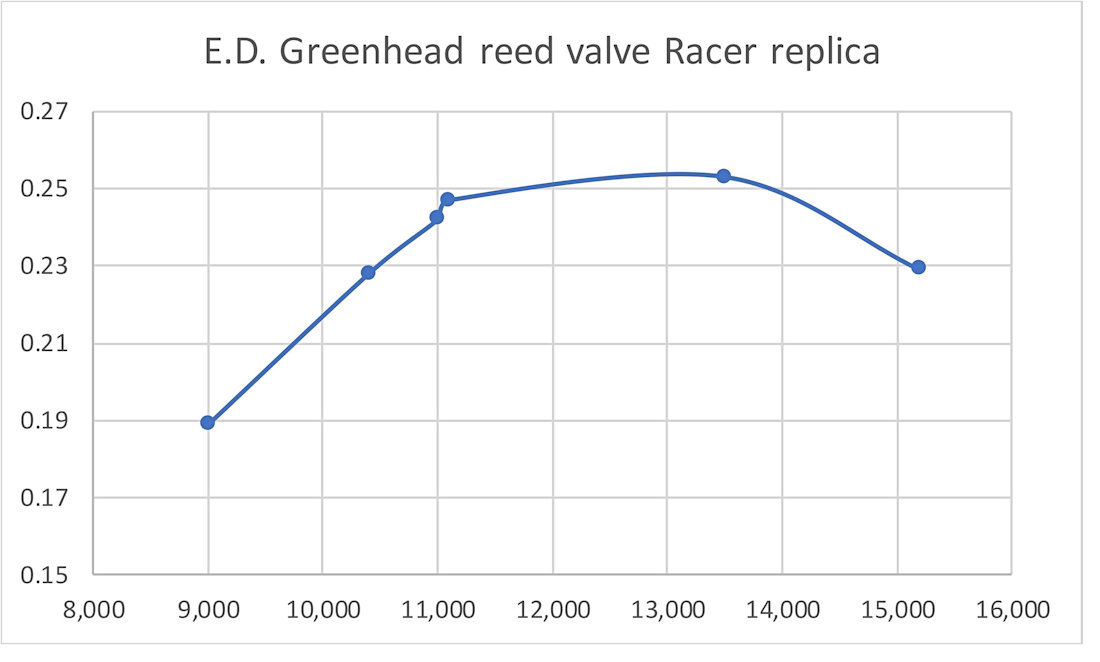

At the time, I didn't know what to make of this engine! I assumed that it represented someone’s unfinished attempt to create a reed valve Racer from a collection of parts! The absence of a serial number seemed consistent with this impression. The engine was in excellent condition mechanically speaking, with minimal bearing wear and outstanding compression. Being curious to Not having an original Greenhead Racer on hand at the time, I used the components of an E.D. Fury as my design guide, merely scaling them up to suit. The backplate was fully machined from aluminium alloy barstock, as were the internal keeper plate and the intake venturi. The reed was made from hardened and tempered 3 thou steel shim stock. The needle valve assembly was an original E.D. combination which I happened to have in my spare parts bin. To my immense gratification, this system turned out to work very well indeed right out of the starting gate! The replica Greenhead Racer (as I viewed it at the time) started very easily and ran flawlessly, with more than adequate suction and a very positive response to both controls. The following data were measured on test.

Obviously, I was missing a few test props back in the day – I missed the peak by a mile! However, the above figures seem coherent enough, suggesting that the re-created E.D. Greenhead Racer developed somewhere around 0.258 BHP @ 12,700 RPM - pretty much identical to the measured performance of the original reed valve Racer tested above. I’d rate that as a pretty successful project! The mystery of this engine's origins was finally solved years later when I consulted E.D. guru Kevin Richards for advice during the preparation of this article in early 2024. It turned out that Kevin had a complete example of my odd-ball Racer, complete with un-numbered aluminium alloy case, shortened stacks, green jacket, reed valve backplate assembly and bobbin prop driver. The aluminium case with shortened stacks identifies the Series 5 Racer, which dates from the final year or so prior to the disastrous arson fire of April 29th, 1962, which caused some very severe damage to the E.D. premises at Island Farm Road in West Molesey, ultimately hastening the downfall of the "original" E.D. company. Kevin's understanding was that a few Series 5 reed valve Racers were made up after 1962 using residual components left over from earlier production. My engine was clearly intended to be one of those presumably rare models, but they evidently ran out of reed valve backplates! It's nice to know that my engine has a genuine E.D. pedigree! There can't be many of these variants in circulation. The Series 5 Greenhead Racer was by no means the last hurrah of the reed valve in club-level FAI team racing. My mate Chris Coote recalled that during his years as a keen FAI team race competitor in the 1960's and 1970's he tried a steel shim reed valve conversion of his ETA Elite using a Cox intake assembly. Power apparently suffered somewhat, but the range on a 7 cc tank went up from 25 laps to 40 laps, although a design error resulted in periodic fatigue failures of the reed. Chris later tried a mylar reed in his 1.5 cc MK-17 used in mini-Goodyear, pushing for 50 laps on a 10 cc tank. The ability of the reed valve to reduce fuel consumption had not diminished! The Later Years

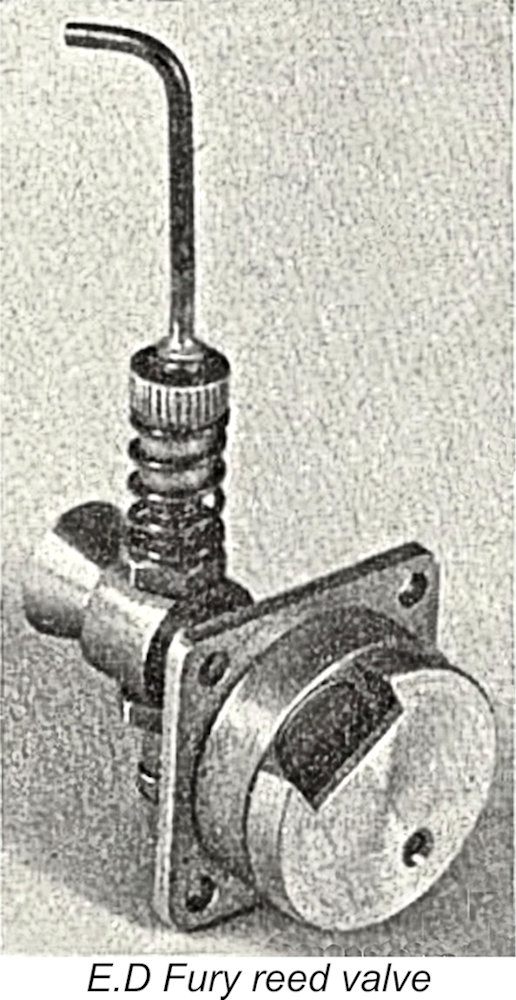

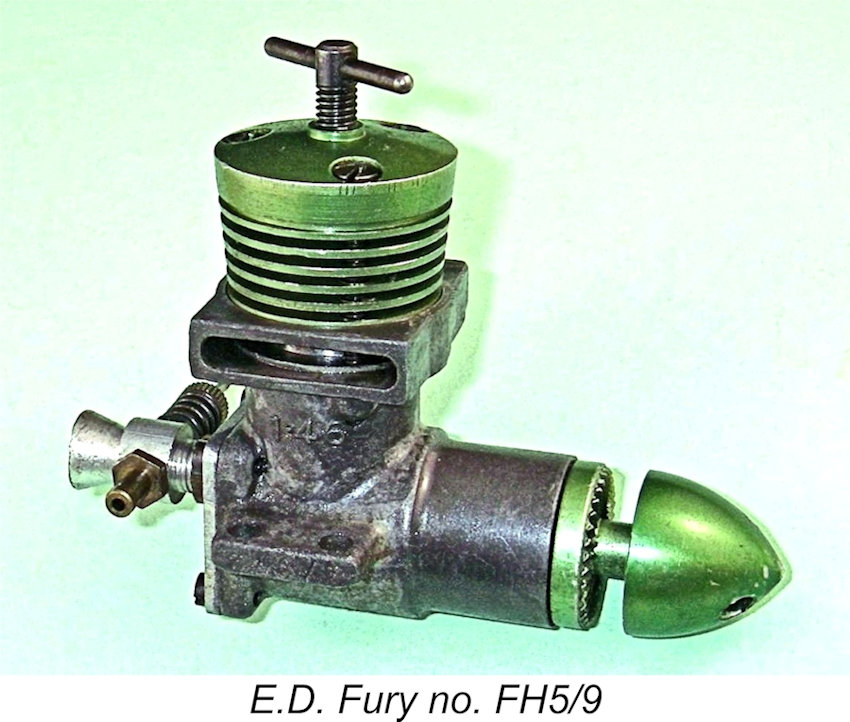

Accordingly, E.D. management decided that a reed valve 1.5 cc diesel based upon the very successful Greenhead Racer design might prove to be a competitive ½A team race engine. Even if it did not yield a truly competitive performance, it should serve its owners well as a sports engine. The 1.46 cc twin ball-race reed valve E.D. diesel that appeared in early 1958 was known as the Fury. To all intents and purposes, it was simply a scaled-down E.D. Greenhead Racer. Most examples even retained the green-anodized cooling jacket, prop driver and spinner of the Fury’s larger relative, although a few early examples were marketed with plain un-anodized components.

The 2.46 cc Racer continued to sell well in its red-jacketed disc valve form, also continuing to be offered as a special-order item as a reed valve model. In early 1958 the material used in the main castings was changed from magnesium alloy to aluminium alloy, but apart from that the engines continued basically unchanged. The reed valve variant seems to have finally disappeared altogether in mid 1960, but the disc valve model continued right up to the end of the “original” E.D. company based in West Molesey and even beyond. After several changes of ownership, the E.D. marque came into the possession of Ken Day, the nephew of one of the original company’s founding Directors. Day relocated the operation to an address in Surbiton, subsequently resuming production of a number of models, including the disc valve Racer. The activities of Day’s company were by no means confined to model engine production - they also engaged in precision engineering sub-contract work for others. Reader David Lloyd recalled working for a company located in West Molesey which had contracted with Ken Day for some precision engineering work. David had to go to Surbiton to meet with Ken Day for the purpose of sorting out some kind of problem. While there, he was shown the small separate workshop in which the E.D. engines were manufactured as something of a side-show!

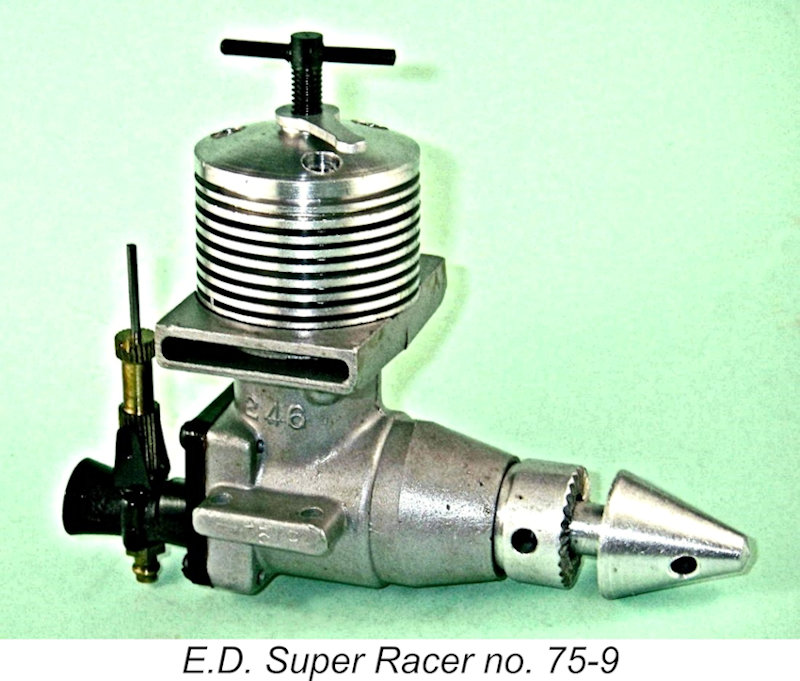

Kevin Lindsey was very much focused on increasing the power-to-weight ratio of the Racer. He held the opinion that Basil had missed an obvious trick that could improve incoming fuel mixture flow by effectively straightening out its path through the engine. Accordingly, one change that he made was to rotate the backplate 90 degrees clockwise and make a new disc with the drive pin hole moved 90 degrees to match. With this and a few other changes, Kevin appeared to have succeeded in extracting a modestly increased specific output from the Super Racer if published test figures were anything to go by (0.281 BHP @ 13,900 RPM). Basil’s most strenuous objection to Lindsey’s design changes was reserved for his adoption of a relocated intake venturi. Contrary to Lindsey’s opinion, Basil had been well aware of the potential gas flow benefits of this option but had discarded the idea because of his recognition that the incoming fuel mixture served multiple purposes. Among these was its role in cooling and lubricating the heavily-loaded crankpin and con-rod big-end bearing. Kevin’s modification undeniably increased power by a small amount but tended to starve the big end bearing Although he was quite unhappy with what had been done to his Racer design without his knowledge or consent, Basil Miles recognized that the situation was very much a fait accompli, since too many examples had already been sold prior to Miles becoming aware of what had been done. However, he did take action with respect to the Hunter, as recorded earlier. His intervention led to Alan Greenfield being brought in to oversee the required modifications to that design. Alan was later to assume ownership of the E.D. marque, a state of affairs which continues to this day (2024). The revised versions of the E.D. Racer survived well into the 1980’s while the Super Hunter and Super Otter stayed the course even longer. As a result of the combined efforts of the original E.D. company; Ken Day’s Surbiton-based operation; and Alan Greenfield’s latter-day efforts, the Racer ended up enjoying a production life of over 30 years – a remarkable record for a British diesel dating back to 1951! The engine continues to be valued today both as a collector’s item and as an excellent powerplant for vintage model sport-flying. Way to go, Basil Miles!! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published June 2024 |

||||

| |

In this article I’ll present a review and test of one of the less familiar model engines developed by

In this article I’ll present a review and test of one of the less familiar model engines developed by  In a

In a  As it was, by 1950 a number of competing 2.5 cc diesels which out-performed the Mk. III to a considerable degree had reached the market. Most notable of these were the

As it was, by 1950 a number of competing 2.5 cc diesels which out-performed the Mk. III to a considerable degree had reached the market. Most notable of these were the  My friend Marcus Tidmarsh has pointed out that the engines produced by E.D. seem to have fallen into two categories – those in effect designed “in house” by E.D. staff and those designed by an outside consultant. Charlie Cray seems to have been an E.D. employee, while Kevin Richards’ in-depth research has shown that Basil Miles was never an E.D. employee at any time – he was not one of the original working shareholders in the company, nor did he ever hold an official position of any sort at E.D. His design work for the company must therefore have been carried out on some kind of a contractual basis.

My friend Marcus Tidmarsh has pointed out that the engines produced by E.D. seem to have fallen into two categories – those in effect designed “in house” by E.D. staff and those designed by an outside consultant. Charlie Cray seems to have been an E.D. employee, while Kevin Richards’ in-depth research has shown that Basil Miles was never an E.D. employee at any time – he was not one of the original working shareholders in the company, nor did he ever hold an official position of any sort at E.D. His design work for the company must therefore have been carried out on some kind of a contractual basis.

Basil certainly held this view himself – when reminiscing years later with his good friend Alan Greenfield, he recalled his anger at discovering what Ken Day (later owner of the E.D. marque) and Kevin Lindsey had done to the E.D. Hunter design to create the original exhaust-throttled versions of the E.D. “Super Hunter” and “Super Otter” designs of the mid-1960’s. As far as he was concerned, their modifications were a botch-up of his design. He reminded Ken Day that the Hunter was his design, claiming to have documentary evidence to support this. Under these documented terms, any design changes had to be approved by Basil, and such approval had not been sought. At Basil’s insistence, Alan Greenfield became involved at this point to oversee the finalization of the two designs to Basil’s requirements.

Basil certainly held this view himself – when reminiscing years later with his good friend Alan Greenfield, he recalled his anger at discovering what Ken Day (later owner of the E.D. marque) and Kevin Lindsey had done to the E.D. Hunter design to create the original exhaust-throttled versions of the E.D. “Super Hunter” and “Super Otter” designs of the mid-1960’s. As far as he was concerned, their modifications were a botch-up of his design. He reminded Ken Day that the Hunter was his design, claiming to have documentary evidence to support this. Under these documented terms, any design changes had to be approved by Basil, and such approval had not been sought. At Basil’s insistence, Alan Greenfield became involved at this point to oversee the finalization of the two designs to Basil’s requirements.

The new model was the subject of a

The new model was the subject of a  With these two very positive endorsements to get it off to a good start, the Racer proved to be a strong and steady seller for many years, passing through a few more relatively minor variations as time went by. The Racer was always sold as a diesel, but both glow-plug and spark ignition conversion kits were made available. The glow-plug conversions seem to have been quite popular, to judge by their present-day survival rates. Interestingly enough, a few examples of the reed valve Racer were converted to glow-plug operation, presumably by their owners using the conversion components which were available from E.D.

With these two very positive endorsements to get it off to a good start, the Racer proved to be a strong and steady seller for many years, passing through a few more relatively minor variations as time went by. The Racer was always sold as a diesel, but both glow-plug and spark ignition conversion kits were made available. The glow-plug conversions seem to have been quite popular, to judge by their present-day survival rates. Interestingly enough, a few examples of the reed valve Racer were converted to glow-plug operation, presumably by their owners using the conversion components which were available from E.D. Along the way, the engine accumulated an outstanding contest record both at the National and International levels. This was particularly true in the control line stunt event, which was then dominated in Europe by small-displacement diesels as opposed to the larger glow-plug motors which ruled the roost in the USA. The Racer powered the Gold Trophy winners at the British National Championships in every year from 1953 to 1957 inclusive, also picking up wins at the World Control-Line Stunt Championships in 1954 and 1956 just for good measure. Quite a run of success! In the capable hands of Pete Buskell, the engine also proved to be a formidable competitor in the international free flight contest arena.

Along the way, the engine accumulated an outstanding contest record both at the National and International levels. This was particularly true in the control line stunt event, which was then dominated in Europe by small-displacement diesels as opposed to the larger glow-plug motors which ruled the roost in the USA. The Racer powered the Gold Trophy winners at the British National Championships in every year from 1953 to 1957 inclusive, also picking up wins at the World Control-Line Stunt Championships in 1954 and 1956 just for good measure. Quite a run of success! In the capable hands of Pete Buskell, the engine also proved to be a formidable competitor in the international free flight contest arena. Perhaps the most notable achievements with the glow-converted Racer were those of British speed ace Pete Wright, who began by establishing a new FAI Class I (2.5 cc) World Control-Line Speed Record of 165.136 km/hr (102.61 mph) at an international meeting held in 1952 at Namur in Belgium. Wright later went on to set a new British 2.5 cc speed record at an amazing 111.3 mph (179.11 km/hr) at the 1954 British National Championships. For context, it's worth noting that this speed would have been good enough to secure second place a year later at the 1955 World Control-Line Speed Championships, only fractionally behind Josef Sladký's winning speed of 111.84 mph (179.98 km/hr) using his State-sponsored MVVS tool-room special engine at that event.

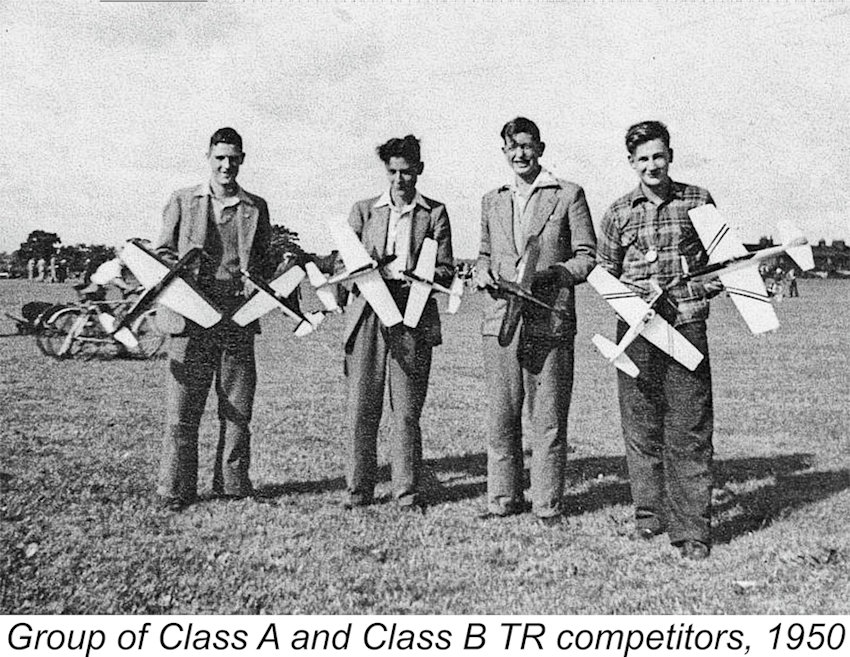

Perhaps the most notable achievements with the glow-converted Racer were those of British speed ace Pete Wright, who began by establishing a new FAI Class I (2.5 cc) World Control-Line Speed Record of 165.136 km/hr (102.61 mph) at an international meeting held in 1952 at Namur in Belgium. Wright later went on to set a new British 2.5 cc speed record at an amazing 111.3 mph (179.11 km/hr) at the 1954 British National Championships. For context, it's worth noting that this speed would have been good enough to secure second place a year later at the 1955 World Control-Line Speed Championships, only fractionally behind Josef Sladký's winning speed of 111.84 mph (179.98 km/hr) using his State-sponsored MVVS tool-room special engine at that event. An event which was growing steadily in popularity during this period was control-line team racing. As of 1950 the Society of Model Aeronautical Engineers (S.M.A.E.), the then-current ruling body for British aeromodelling, had established two classes for this event – Class A for engines of up to 2.5 cc displacement, and Class B for 5 cc motors. The latter category was ruled by 5 cc glow-plug motors like the

An event which was growing steadily in popularity during this period was control-line team racing. As of 1950 the Society of Model Aeronautical Engineers (S.M.A.E.), the then-current ruling body for British aeromodelling, had established two classes for this event – Class A for engines of up to 2.5 cc displacement, and Class B for 5 cc motors. The latter category was ruled by 5 cc glow-plug motors like the  The main Achilles’ Heel of the Racer in a team-race context continued to be its relatively poor fuel economy by comparison with that achieved by the competing Oliver Tiger. In order to maintain a competitive pit stop schedule, it was necessary to operate the engine at speeds some distance below the peak, thus sacrificing model speed. However, operation at such speeds naturally increased the proportion of fuel lost due to induction blow-back. A classic vicious circle!

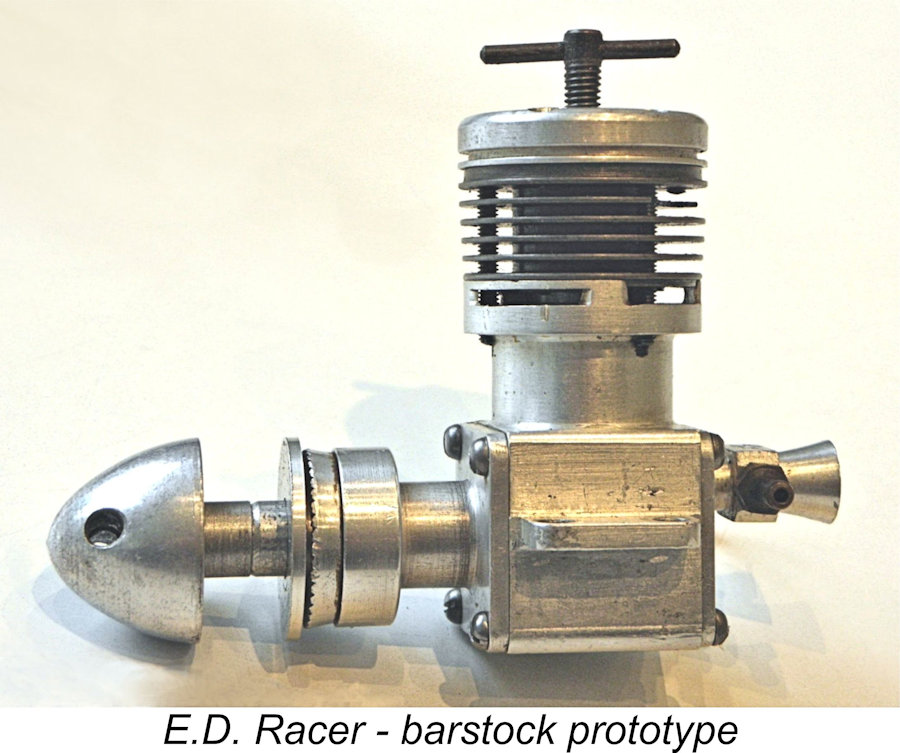

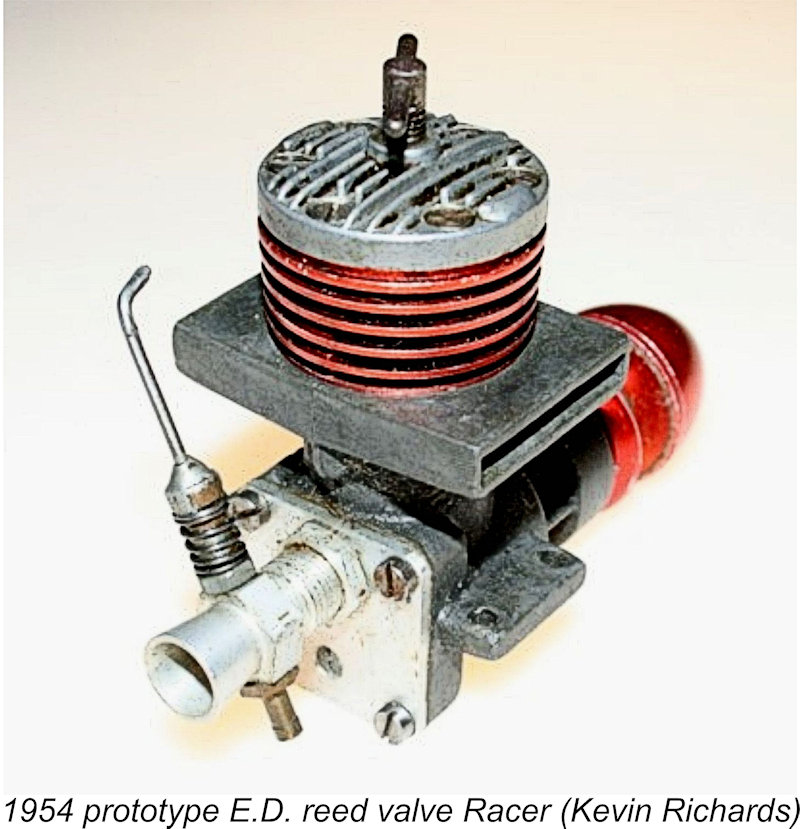

The main Achilles’ Heel of the Racer in a team-race context continued to be its relatively poor fuel economy by comparison with that achieved by the competing Oliver Tiger. In order to maintain a competitive pit stop schedule, it was necessary to operate the engine at speeds some distance below the peak, thus sacrificing model speed. However, operation at such speeds naturally increased the proportion of fuel lost due to induction blow-back. A classic vicious circle!  The potential effectiveness of the reed valve modification in a team racing context was just as apparent to E.D. as it was to their team race customers. Kevin Richards was able to confirm that E.D. had their own reed valve prototype running at the factory by early 1954 - as of 2024, he still had the prototype engine in his possession. This unit is a barstock reed valve conversion of a standard red-jacketed Series 2 E.D. Racer, using an E.D. Mk. IV Hunter intake assembly. Note that the intake is at the top of the backplate rather than 45 degrees clockwise as in the production models. Of course, the reed valve will work regardless of how the backplate is oriented.

The potential effectiveness of the reed valve modification in a team racing context was just as apparent to E.D. as it was to their team race customers. Kevin Richards was able to confirm that E.D. had their own reed valve prototype running at the factory by early 1954 - as of 2024, he still had the prototype engine in his possession. This unit is a barstock reed valve conversion of a standard red-jacketed Series 2 E.D. Racer, using an E.D. Mk. IV Hunter intake assembly. Note that the intake is at the top of the backplate rather than 45 degrees clockwise as in the production models. Of course, the reed valve will work regardless of how the backplate is oriented.

Despite the challenge posed by the Oliver Tiger Mk. III from early 1954 onwards, the reed valve E.D. Racers remained in widespread use, earning favourable mention several times in the published "Club News" features during 1954. They continued to achieve some notable contest successes, particularly on the Continent. The January 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft” carried the plans for the “

Despite the challenge posed by the Oliver Tiger Mk. III from early 1954 onwards, the reed valve E.D. Racers remained in widespread use, earning favourable mention several times in the published "Club News" features during 1954. They continued to achieve some notable contest successes, particularly on the Continent. The January 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft” carried the plans for the “

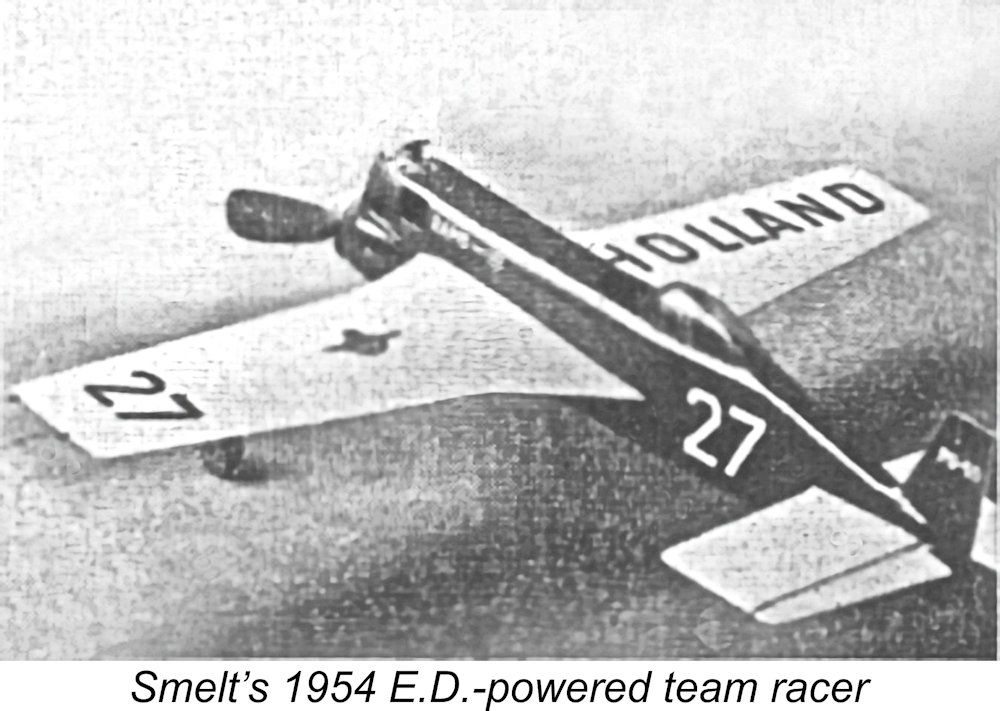

Racer outran the Olivers used by the two British teams who finished second and third as well as the fourth-place Oliver-powered Dutch entry. At the finish, the entire four-model field was covered by 9 seconds! According to the "Aeromodeller" report on this event which appeared in the June 1956 issue of the magazine, Smelt's winning entry was powered by an "ancient coke-filled clack valve E.D."! Perhaps the coke made all the difference ...............

Racer outran the Olivers used by the two British teams who finished second and third as well as the fourth-place Oliver-powered Dutch entry. At the finish, the entire four-model field was covered by 9 seconds! According to the "Aeromodeller" report on this event which appeared in the June 1956 issue of the magazine, Smelt's winning entry was powered by an "ancient coke-filled clack valve E.D."! Perhaps the coke made all the difference ............... Even so, the reed valve model was never advertised at any time. It was kept available as a buyer’s option for some years, seemingly being finally withdrawn in mid to late 1960. During its four-year period of availability, it was never the subject of a published test report, nor could Gordon Beeby find any specific reference to the factory product in the contemporary modelling media. In addition, it appears never to have been listed by any of the nationally-advertising retail outlets, presumably remaining a “special-order” item direct from E.D. throughout. As a result, relatively few contemporary modellers were even aware of its existence! I was one of them ………..

Even so, the reed valve model was never advertised at any time. It was kept available as a buyer’s option for some years, seemingly being finally withdrawn in mid to late 1960. During its four-year period of availability, it was never the subject of a published test report, nor could Gordon Beeby find any specific reference to the factory product in the contemporary modelling media. In addition, it appears never to have been listed by any of the nationally-advertising retail outlets, presumably remaining a “special-order” item direct from E.D. throughout. As a result, relatively few contemporary modellers were even aware of its existence! I was one of them ………..

The two numbers which do not fit into any recognized E.D. serial numbering sequence are Peter Valicek's engine no. YR 047 and my own illustrated unit no. YR 7 7. The batch letter R does not conform to the standard E.D. format which represents the month of production using letters from A to N for January to December, with I and L being omitted for various reasons. Both engines feature magnesium cases incorporating the large-diameter Series 3 main bearing housing. They both evidently date from the same batch in 1957.

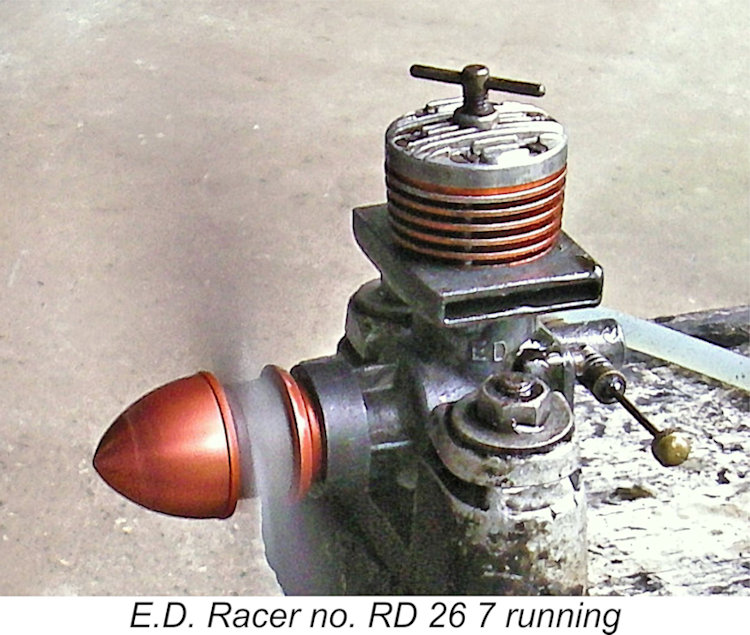

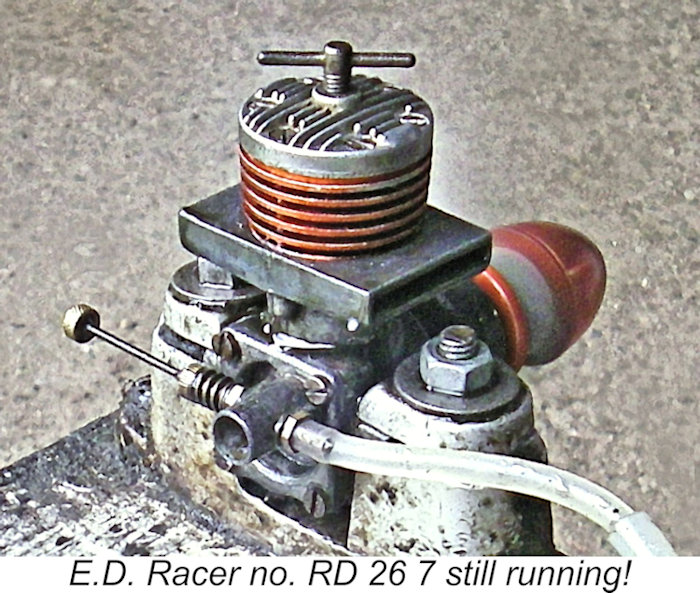

The two numbers which do not fit into any recognized E.D. serial numbering sequence are Peter Valicek's engine no. YR 047 and my own illustrated unit no. YR 7 7. The batch letter R does not conform to the standard E.D. format which represents the month of production using letters from A to N for January to December, with I and L being omitted for various reasons. Both engines feature magnesium cases incorporating the large-diameter Series 3 main bearing housing. They both evidently date from the same batch in 1957.  I’m unusually well-equipped to provide an answer to the performance question, since I have nice used but complete and original examples of both the disc valve and reed valve Racers which were manufactured in 1957 only a few months apart. The disc valve model bears the serial number RD 26 7, making it the 26

I’m unusually well-equipped to provide an answer to the performance question, since I have nice used but complete and original examples of both the disc valve and reed valve Racers which were manufactured in 1957 only a few months apart. The disc valve model bears the serial number RD 26 7, making it the 26 In undertaking this comparative test, I was more interested in the comparative performance levels of the two models rather than their absolute performance figures. I therefore planned to keep testing time down to a minimum by focusing on airscrews which allowed the engines to run at and around their respective peaking speeds. I selected a suite of five props which experience told me should bracket the peak nicely. I used an oily fuel containing ether, kerosene and castor oil in 35/35/30 proportions, adding 1½% ignition improver. Not the strongest-running fuel, but kind to the engines. In any event, it was relative rather than ultimate performance in which I was interested.

In undertaking this comparative test, I was more interested in the comparative performance levels of the two models rather than their absolute performance figures. I therefore planned to keep testing time down to a minimum by focusing on airscrews which allowed the engines to run at and around their respective peaking speeds. I selected a suite of five props which experience told me should bracket the peak nicely. I used an oily fuel containing ether, kerosene and castor oil in 35/35/30 proportions, adding 1½% ignition improver. Not the strongest-running fuel, but kind to the engines. In any event, it was relative rather than ultimate performance in which I was interested.  First up was the standard disc valve Racer no. RD 26 7. I've had a lot of experience with these engines, having used them with great satisfaction over a period of many years. This example was actually a little tight, having evidently seen little previous use. However, it did not disappoint, starting up promptly and running very smoothly indeed. Settings were easy to establish, while vibration levels remained quite modest at all speeds.

First up was the standard disc valve Racer no. RD 26 7. I've had a lot of experience with these engines, having used them with great satisfaction over a period of many years. This example was actually a little tight, having evidently seen little previous use. However, it did not disappoint, starting up promptly and running very smoothly indeed. Settings were easy to establish, while vibration levels remained quite modest at all speeds.

So what about fuel consumption? Here the comparative tests using my somewhat under-capacity tank were quite revealing. The very "oily" fuel that I used for this test cannot be viewed as an economical brew, since only 70% of it was actually fuel! A team race competitor would use far less oil and more kerosene. In addition, I conducted these fuel consumption tests using an APC 8x4 prop which had the engines running at speeds which were fractionally above their peaking speeds on the bench. Even in the air they would not turn nearly as fast on the parasitic 8x8 props typically used on these engines at the time in team race applications. Their consumption using less oily fuels with higher kerosene contents and running at lower speeds would obviously be much improved.

So what about fuel consumption? Here the comparative tests using my somewhat under-capacity tank were quite revealing. The very "oily" fuel that I used for this test cannot be viewed as an economical brew, since only 70% of it was actually fuel! A team race competitor would use far less oil and more kerosene. In addition, I conducted these fuel consumption tests using an APC 8x4 prop which had the engines running at speeds which were fractionally above their peaking speeds on the bench. Even in the air they would not turn nearly as fast on the parasitic 8x8 props typically used on these engines at the time in team race applications. Their consumption using less oily fuels with higher kerosene contents and running at lower speeds would obviously be much improved.  There’s a pre-script to this story which is well worth including! Many years ago now, I acquired a green-jacketed E.D. Racer which was built up around an aluminium alloy case featuring the large-diameter unbraced main bearing housing and having shortened stacks along with an unanodized bobbin prop driver. There was no serial number. As received, the engine lacked a backplate assembly. However, the green jacket implied that it had been a reed valve model, a view which was confirmed by the fact that its crankshaft had a shortened crankpin.

There’s a pre-script to this story which is well worth including! Many years ago now, I acquired a green-jacketed E.D. Racer which was built up around an aluminium alloy case featuring the large-diameter unbraced main bearing housing and having shortened stacks along with an unanodized bobbin prop driver. There was no serial number. As received, the engine lacked a backplate assembly. However, the green jacket implied that it had been a reed valve model, a view which was confirmed by the fact that its crankshaft had a shortened crankpin.  find out how a reed valve Racer might have performed, I decided to restore this unit as closely as possible to what appeared to be its intended configuration. To that end, I made a complete reed valve backplate assembly. If those 1953 team racers could do it, so could I!

find out how a reed valve Racer might have performed, I decided to restore this unit as closely as possible to what appeared to be its intended configuration. To that end, I made a complete reed valve backplate assembly. If those 1953 team racers could do it, so could I!

The success achieved by the reed valve Racer in Class A team racing seems to have convinced E.D. management that a 1.5 cc model using the same technology might fare equally well in the ½A team race category which had been introduced by the S.M.A.E. to cater to the increasingly-popular 1.5 cc engines which were in wide circulation. As of 1957, E.D.’s only entry into this displacement category had been their disc valve

The success achieved by the reed valve Racer in Class A team racing seems to have convinced E.D. management that a 1.5 cc model using the same technology might fare equally well in the ½A team race category which had been introduced by the S.M.A.E. to cater to the increasingly-popular 1.5 cc engines which were in wide circulation. As of 1957, E.D.’s only entry into this displacement category had been their disc valve  Unfortunately, the performance of the Fury fell sufficiently far below that of most of the competition that contest modellers weren’t interested. On test, the Fury was found to develop peak outputs of 0.1315 BHP @ 14,000 RPM (

Unfortunately, the performance of the Fury fell sufficiently far below that of most of the competition that contest modellers weren’t interested. On test, the Fury was found to develop peak outputs of 0.1315 BHP @ 14,000 RPM ( At some point during the mid-1960’s the well-known competition aeromodeller Kevin Lindsey was brought in to help Day in the upgrading of the E.D. designs. I already summarized Basil Miles’ reaction to Lindsey’s modifications applied to the 3.46 cc Hunter design. According to Alan Greenfield, who knew Basil very well, he was equally unimpressed with the design changes which had been made to the Racer to create its supposedly superior Super Racer descendant. These changes had been made without Miles’ knowledge or consent in his capacity as the owner of the Racer design.

At some point during the mid-1960’s the well-known competition aeromodeller Kevin Lindsey was brought in to help Day in the upgrading of the E.D. designs. I already summarized Basil Miles’ reaction to Lindsey’s modifications applied to the 3.46 cc Hunter design. According to Alan Greenfield, who knew Basil very well, he was equally unimpressed with the design changes which had been made to the Racer to create its supposedly superior Super Racer descendant. These changes had been made without Miles’ knowledge or consent in his capacity as the owner of the Racer design.  of oil and cooling airflow. This could result in big end seizures and consequent conrod breakages as well as accelerated big end wear. Although cases of such failures proved to be quite rare, they did happen. They had been virtually unknown prior to this change.

of oil and cooling airflow. This could result in big end seizures and consequent conrod breakages as well as accelerated big end wear. Although cases of such failures proved to be quite rare, they did happen. They had been virtually unknown prior to this change.