|

|

An Alan Allbon Masterpiece – the Allbon Bambi By Adrian Duncan with Ron Chernich

Unfortunately, my mate Ron left us in early 2014 without sharing the access codes to his heavily-encrypted site. Consequently, MEN has received no maintenance during the 11 years (and counting) following Ron’s untimely departure and is now exhibiting unmistakable signs of the slow process of deterioration which must inevitably result. Check it out while it’s still there to be checked out, guys!! Everyone's thanks are due to Maris Dislers for bearing the ongoing cost of keeping Ron's site open. I was unwilling to accept the risk of the potential loss of Ron’s efforts to document the Bambi through the decay of MEN, hence the appearance of the present article on my own site. In addition, some further information on the engine has since become available, including the opportunity to conduct a latter-day test of the engine. I wish to make it clear that all of Ron’s information is included in this article, which is as much his work as mine. I’ve simply re-organized and clarified the material somewhat, also adding some further information which has since come to light. Background

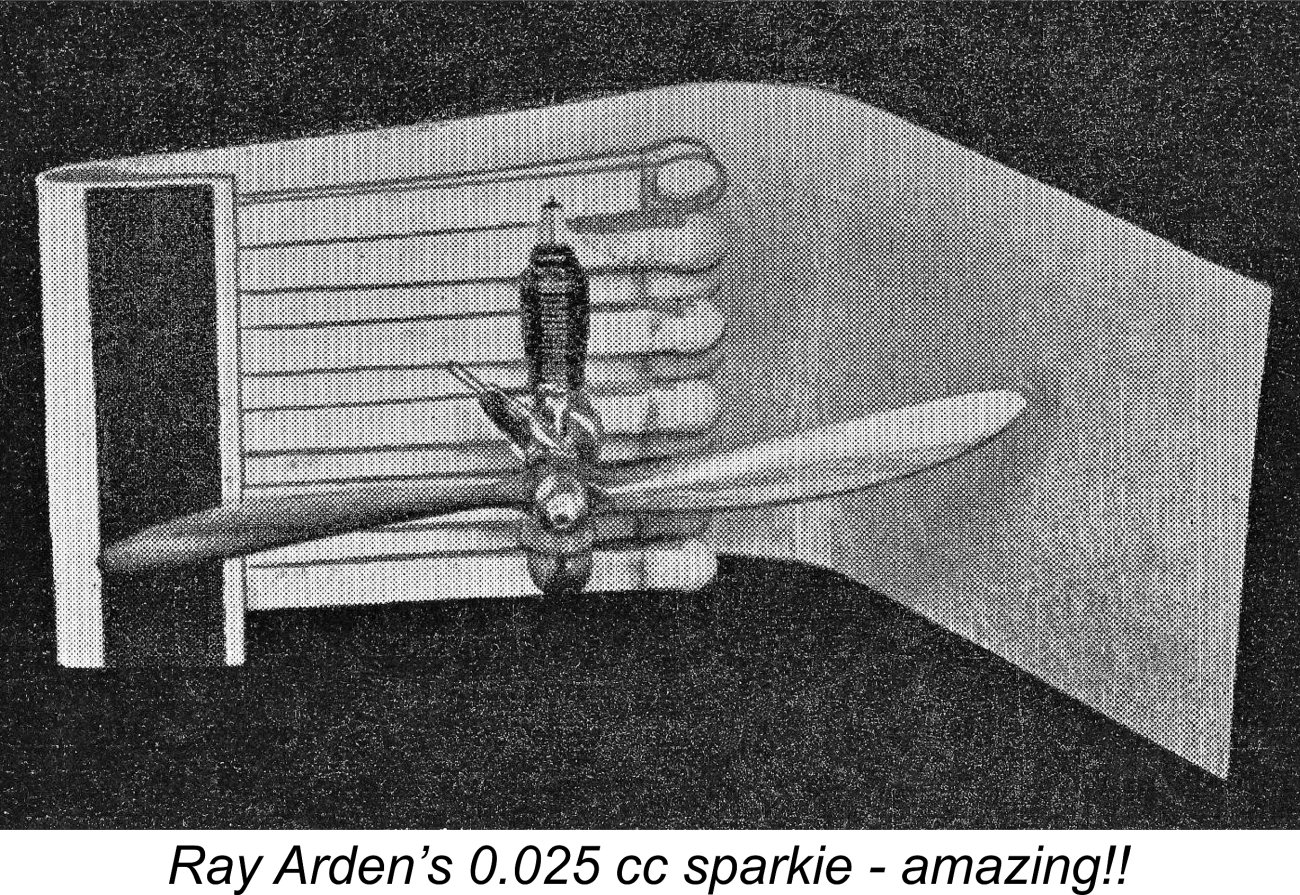

The creation of functional model I/C engines at minimal sizes has always posed an almost irresistible challenge to model engine designers and constructors, who have shown themselves to be endlessly curious to discover just how small a model I/C engine can be built and still operate successfully. The rest of us less talented individuals have cheered from the sidelines and sometimes supported these designers through our purchases of their commercial products. In the past thirty years or so, an amazing variety of tiny sub-miniature model diesels has emerged from the workshops of talented makers from the USA to Russia and all points in between. We tend to take such miniatures for granted, knowing that numerous previous examples have demonstrated the practicality of making diesels down to very small displacements. I suppose that the novelty has worn off to some extent .............. However, it was not always so. Even before the advent of the model diesel allowed modellers to dispense with the heavy, bulky and undependable ignition support systems required by spark ignition engines, the question of just how small a working I/C engine could be made seemed to call for an answer. Because the minimum weight of the required ignition support system was essentially unaffected by The most remarkable of these individuals was undoubtedly the great American model engineer Ray Arden, who made a total mockery of accepted displacement limitations by constructing and demonstrating a successful operating spark ignition motor having a displacement of only 0.0257 cc (0.00157 cuin.)! Bore and stroke were 0.125 in. (3.2 mm) apiece! Having no alternative, Ray made the near-microscopic spark plug himself. One can only stand in awe……………a talent like that doesn’t surface very often! However, it was the advent of the model compression ignition engine (aka “diesel”, an incorrect term with which we’re stuck!) that really turned the attention of model engine designers towards the concept of producing practical sub-miniature I/C powerplants. It might be supposed that the intent was to open up a new field in aeromodelling, but the underlying concept actually seems to have been the simple replacement of rubber motors and their progressively-declining outputs during flight with a small I/C engine, taking advantage of its steady and controllable output during the easily-timed run. Such engines were initially seen primarily as replacements for rubber power in the same types of model. This was a perfectly valid basis upon which to embark upon the development of sub-miniature I/C engines. However, plain old curiosity doubtless played a significant role as well. Once the concept presented itself, it didn’t take long for skilled model engineers in a number of countries to begin to explore the practical lower displacement limits for model diesels. The Early Micro-Diesels

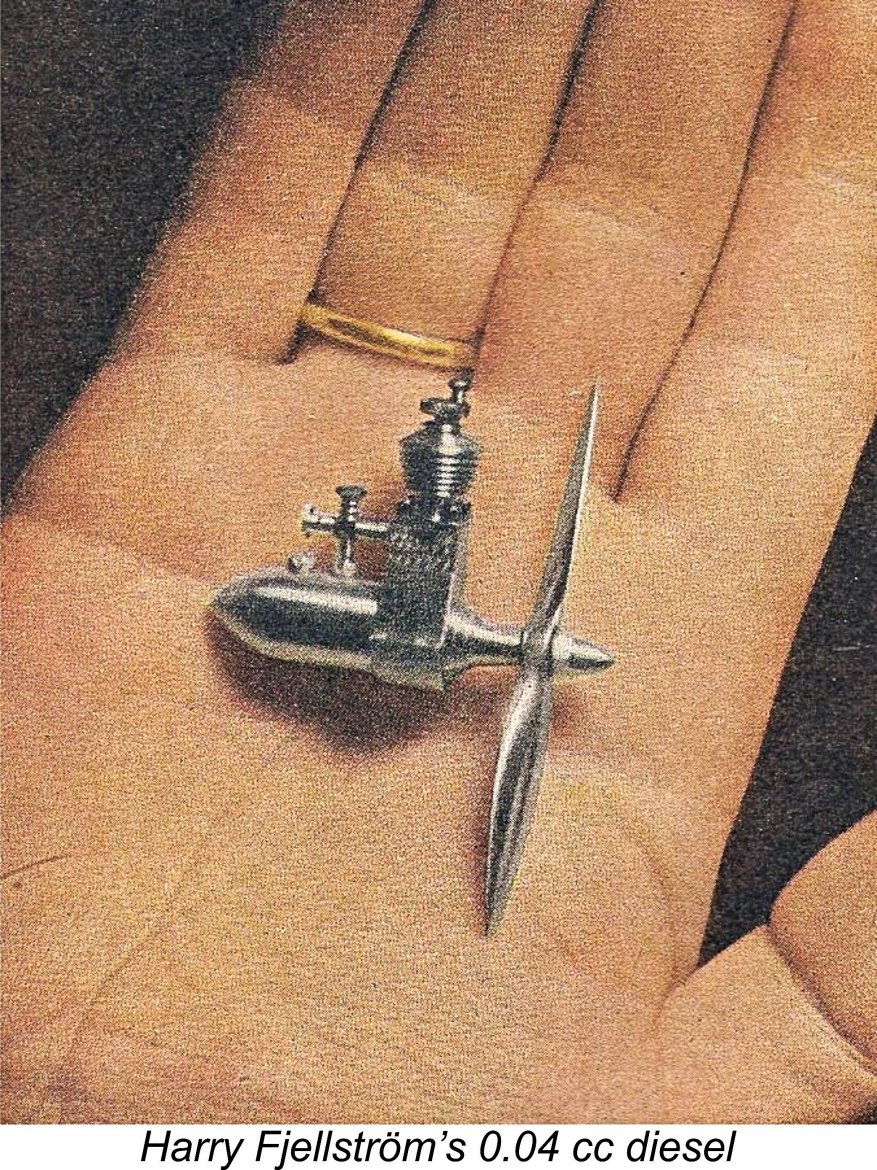

One of the earliest experimenters with the construction of diesel engines having extremely small displacements was the mega-talented Swedish model engineer Harry Fjellström (1910-1996). Beginning in 1945, Fjellström constructed a series of sub-miniature sideport diesels, beginning with a 0.254 cc model and ending up with a truly remarkable unit displacing only 0.040 cc (0.0024 cuin.) which he demonstrated publicly on numerous occasions, to the point that it eventually needed a rebore! Word of Fjellström’s success soon got around, encouraging model engineers from Germany, France, Italy and Britain to have a go for themselves, often with remarkable results. Here we are concerned primarily with a British micro-diesel, so I’ll confine my further comments to British examples of the genre. Those requiring a broader discussion of classic micro-diesel development are referred to my separate article on that subject.

In 1949, Len “Stoo” Steward, who had assumed ownership of Harry Kemp’s operation and re-named the company as the “K” Model Engineering Co., came out with the more advanced radially-ported FRV “K” Hawk Mk. II of only 0.201 cc (0.0122 cuin.) displacement. This was a fine little engine which started and ran very well, as my own tests reported elsewhere have shown. It was probably the best of the early British sub-miniatures.

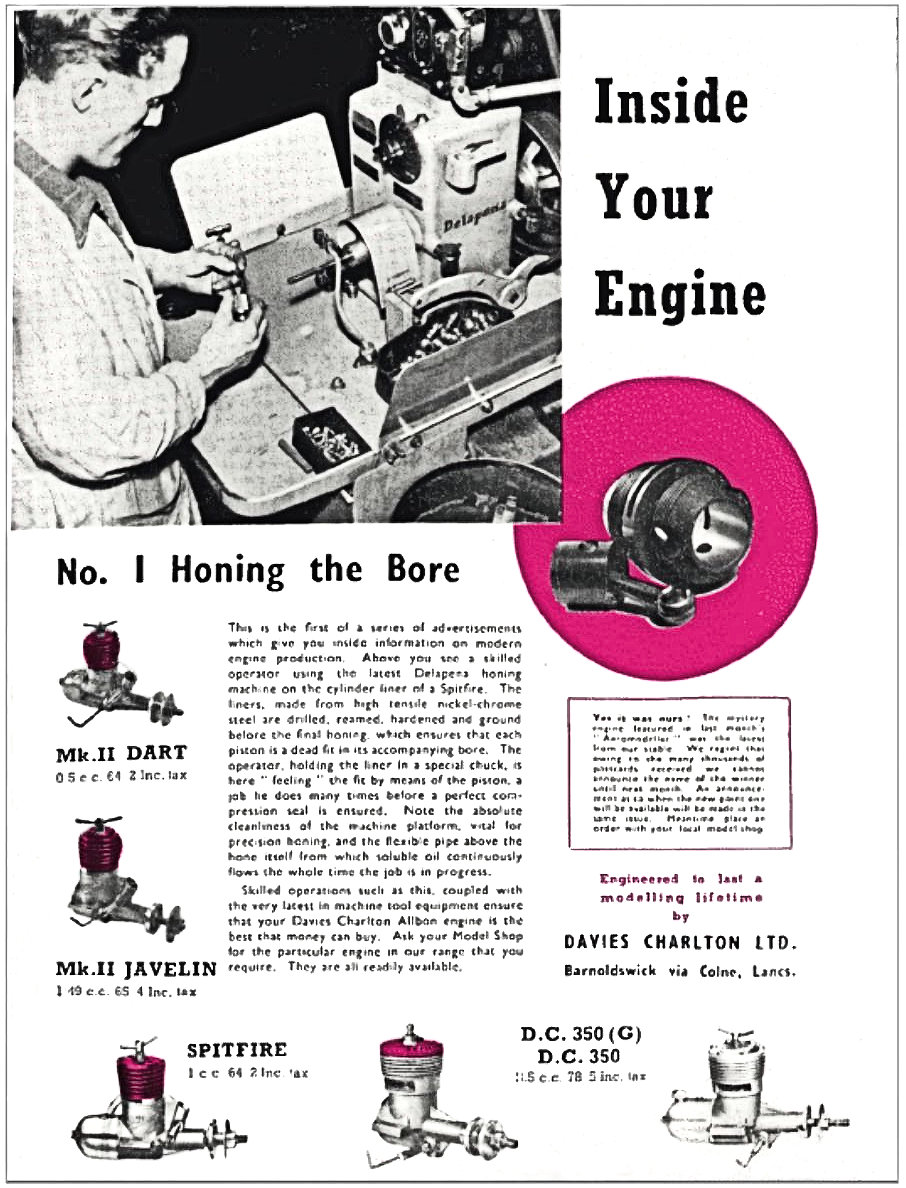

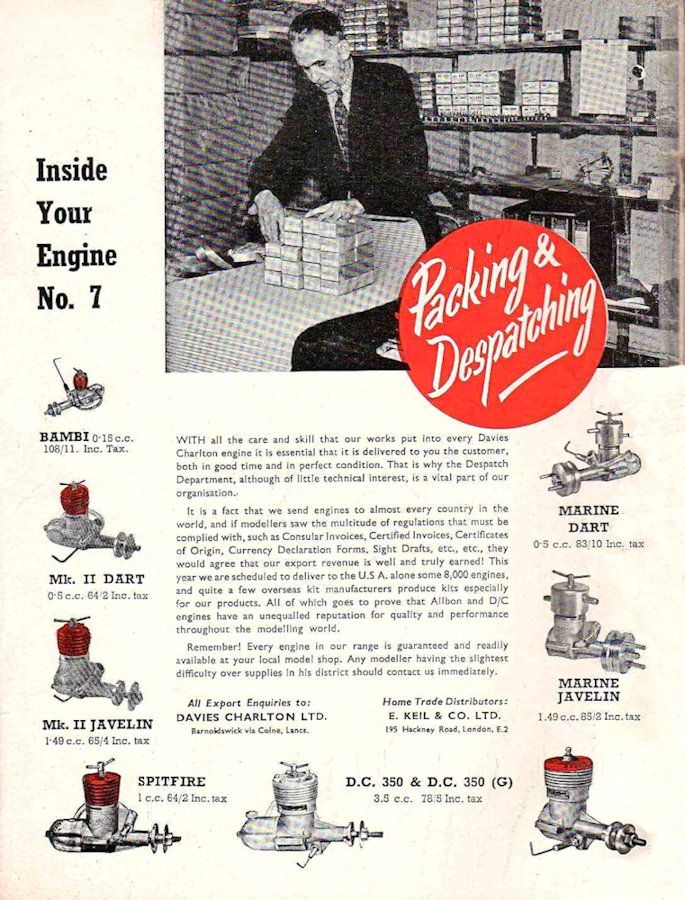

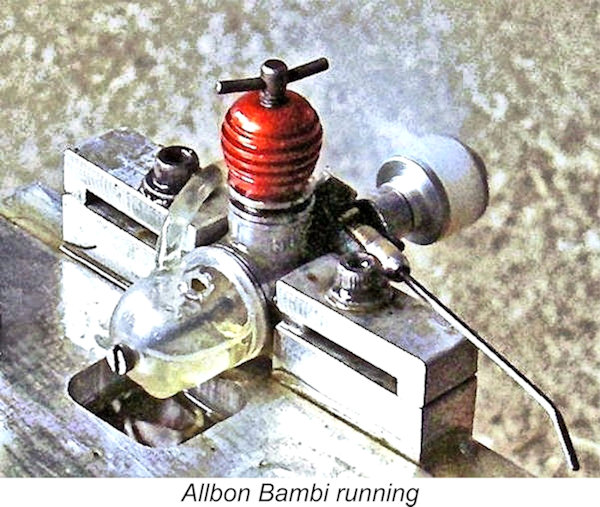

This left the sub-miniature diesel field wide open for another manufacturer to step up to the plate. The designer who took up the challenge was Alan Allbon, whose story has been recounted in detail elsewhere on this website. By the time in question, Allbon was working on what appears to have been a contractual basis with Davies-Charlton Ltd. (D-C Ltd.) at Barnoldswick (pr. "Barlick") in Lancashire. Allbon had already designed several very successful diesels in the shape of the 0.55 cc Allbon Dart, the 1 cc Allbon Spitfire and the 1.5 cc Allbon Javelin. All of these models used the same combination of radial cylinder porting allied to crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction. In mid-1953 Allbon turned his attention towards the exploration of the lower displacement limit to which an engine of this arrangement could be commercially manufactured. The result of Allbon’s deliberations was the appearance of one of the all-time classic British model diesels – the Allbon (D-C) Bambi of 0.15 cc displacement. From this point onwards, I’ll confine my comments to that model. The Allbon (D-C) Bambi – Development and Initial Promotion

Reading between the lines, it seems to be a reasonable conclusion that a combination of Editorial deadlines and development problems led to a period of frenzied activity

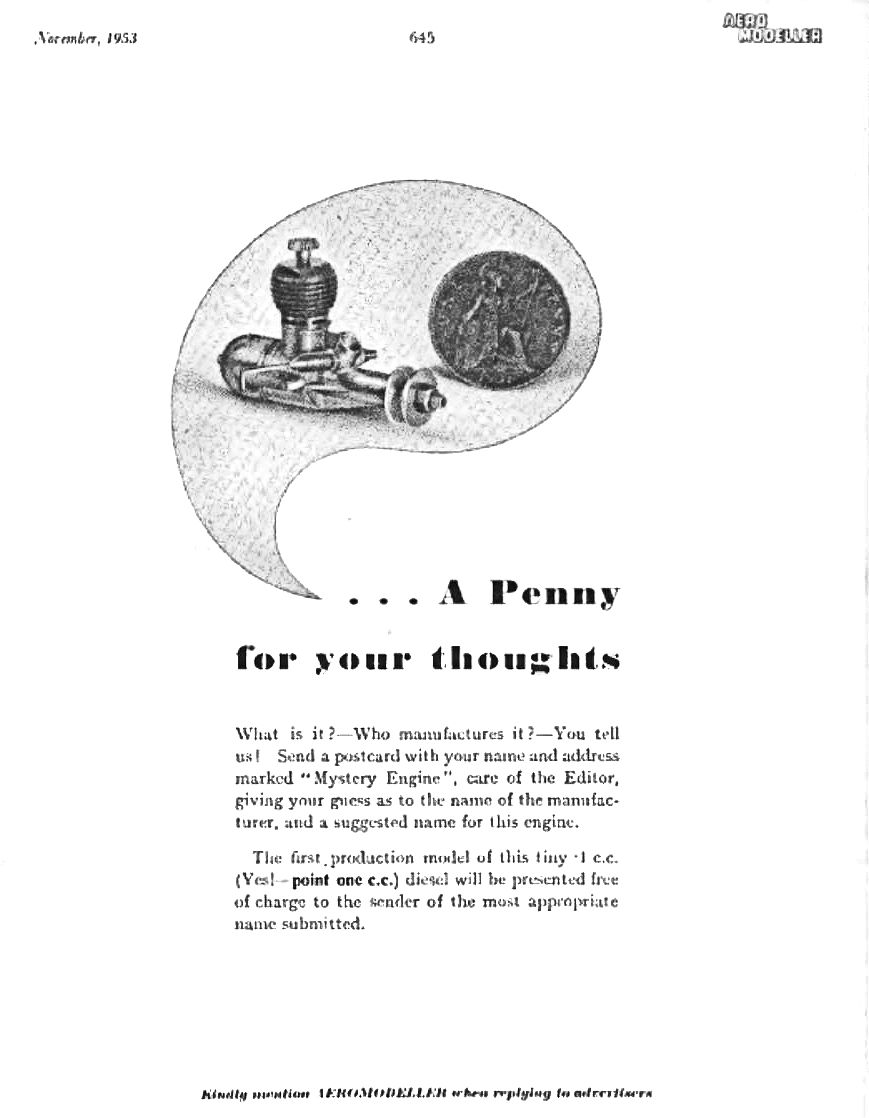

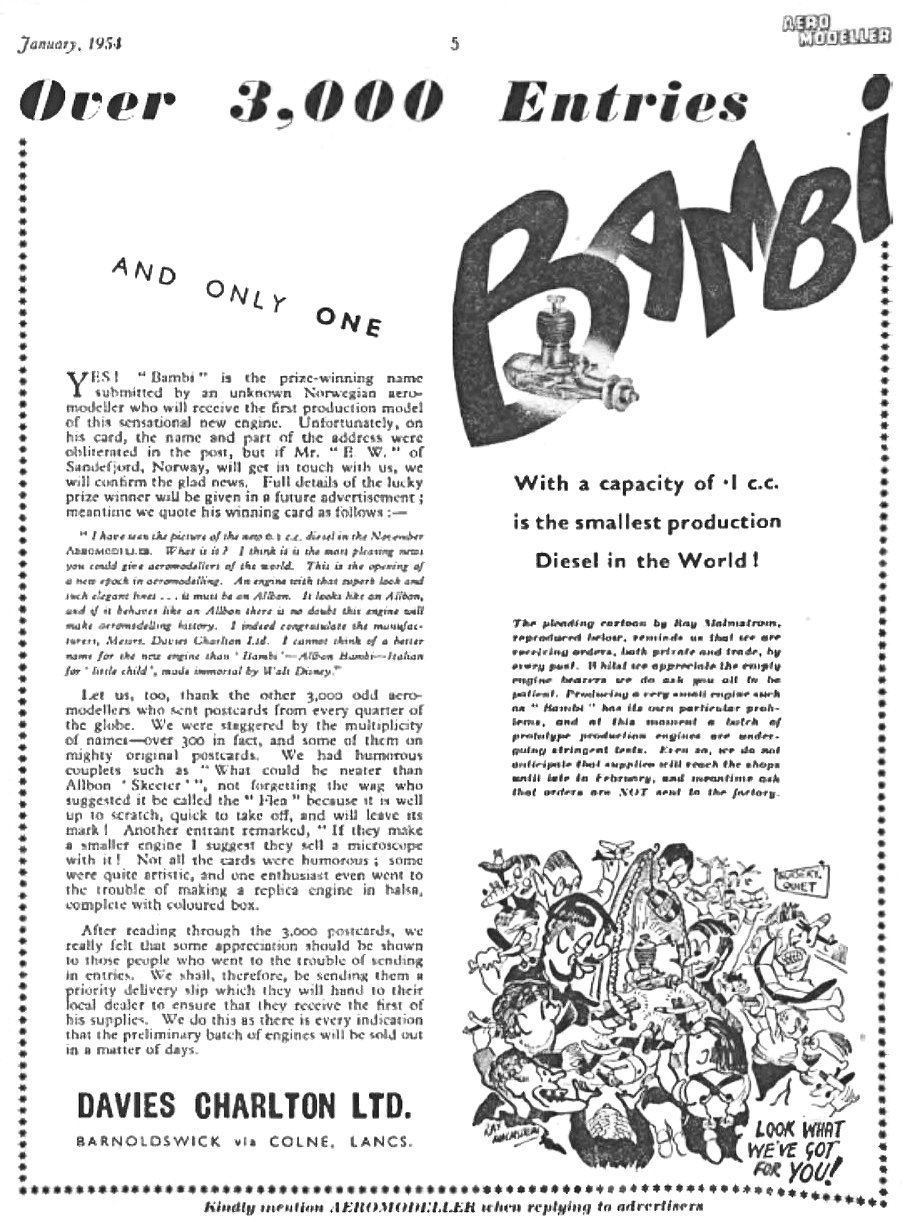

D-C Ltd.’s follow-up in the December 1953 issue would leave today's marketing graduates weeping. Splurge on a full-page add to kick-off the promotion, generate over 3000 responses from all over the planet, and then follow-up with a postage stamp notice in small print under the red-spot on the page admitting responsibility for the engine, but nothing more! However, given the small, closed market The grand announcement of the “Name the Engine” competition result appeared in the January 1954 issue in roughly the same page location of the magazine as the earlier placements. Once again, this announcement took the form of a full-size placement by “Aeromodeller” itself. It was far more "busy" than the last, being accompanied by a Ray Malmström cartoon. Here we find that the name “Bambi” had been selected, along with an acknowledgement of the Walt Disney connection (no (tm) attribution - try that today!). We also learn that the "response was overwhelming" but the winner's name and address had been lost! Oops ………..All we learn is that he was a Norwegian!

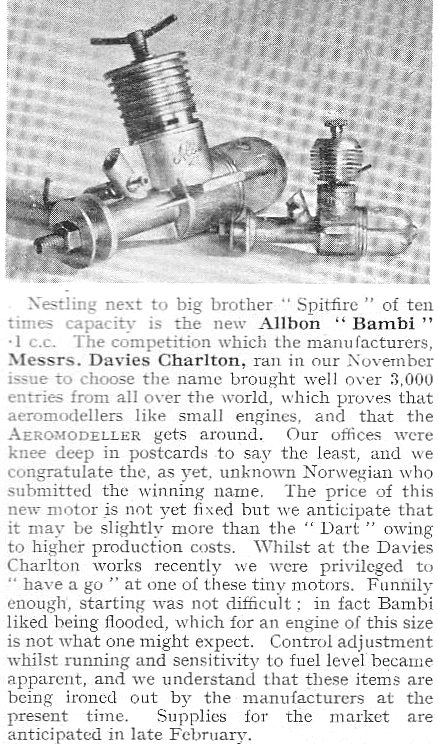

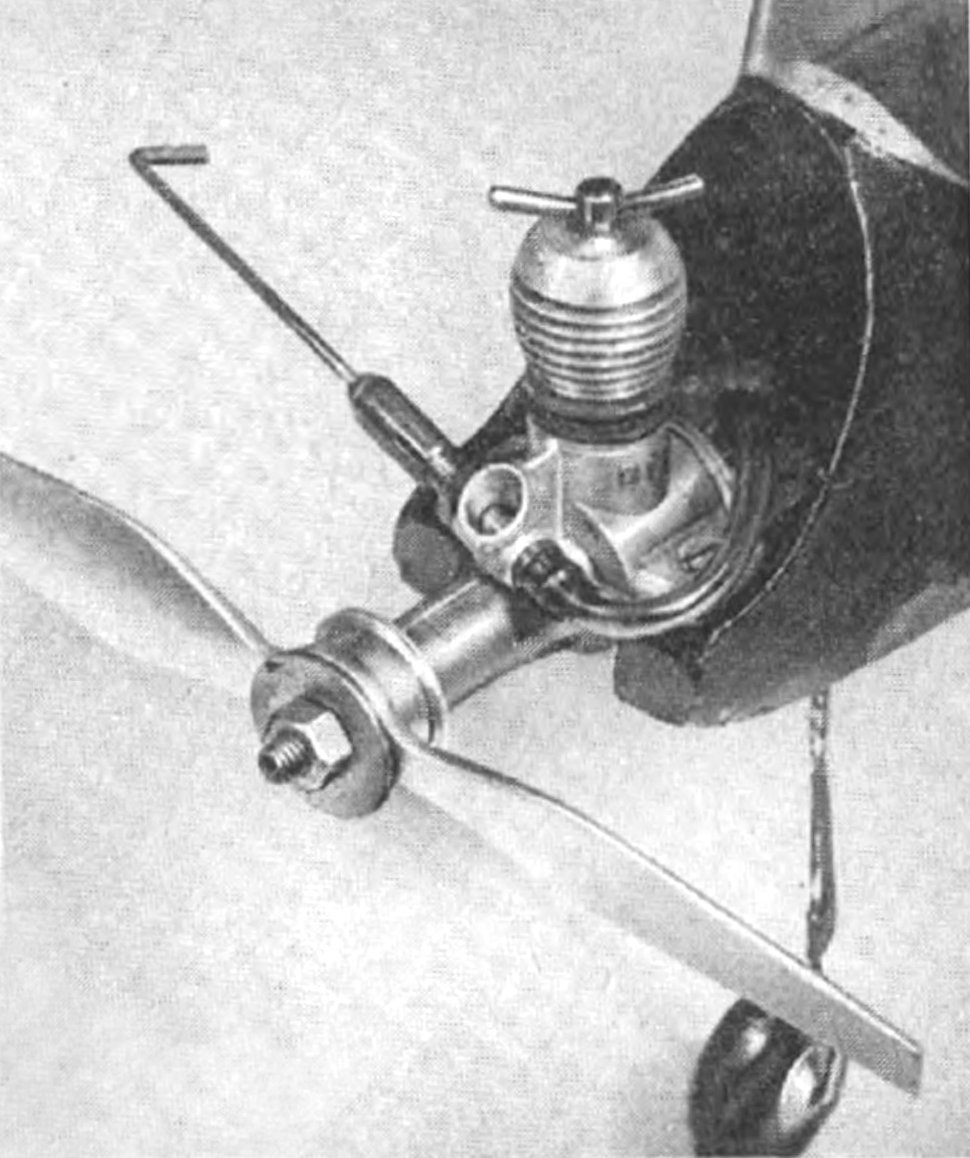

The "Trade Notes" article offered another dribble of pre-production information by suggesting that readers could look forward to a late February trade release. The engine pictured was still one of the prototypes with the pocket-watch style crown-wheel compression screw and the un-knurled prop driver with a 3/16 in. central boss.

The text went on to state that all this was now in the past and that the engine was now "..the production Bambi, bored out to 0.13 c.c., with revised porting..." (emphasis mine). In the accompanying photo (below right), the Moreover, the cited displacement of 0.13 cc is still less than the 0.15 cc displacement of the final production variant. Look closely and you'll also see a spacer behind the prop, and a tapered rear face on the prop driver, another feature absent on production engines. All of this suggests that this was yet another pre-production engine in reality.

This price doubtless reflected the higher cost of maintaining tolerances as the engine displacement was reduced. The company’s cylinder lapping wizard at the time, Arthur Firth, later recalled that the piston/cylinder fit on the Bambi was “a bugger to get right!”. The influence which this challenge had upon manufacturing costs is reflected in the fact that the price given for a replacement piston/ The ad clearly cited the displacement as 0.15 cc, confirming that the so-called “production” model that “Aeromodeller” had seen in May was still evolving at that time. Note also the prominent "D-C" cast into the crankcase on both sides. In a series of ads, D-C Ltd. drew a careful distinction between D-C and Allbon engines, with the Bambi clearly being presented as one of the former. Today though, long-time modellers and collectors (like me!) generally call it the "Allbon Bambi", and we'll see a possible explanation for this later. Writing in the rival “Model Aircraft” magazine, Peter Chinn noted the fact that the Bambi was originally intended to be a 0.1 cc engine, being cited as such in the initial advertisement reproduced above. He This still made the Bambi the smallest-displacement engine ever to enter commercial series production, a record which it held until the November 1991 debut of Dennis Allen's remarkable little 0.1 cc AE .1 diesel, which remained in production until around February 1996. The Bambi weighed less than 20 gm complete with tank and fuel tubing. The assertion in the factory instruction sheet that starting procedure was ...exactly the same as for larger diesels." is open to some dispute, unless you consider the "team race start" procedure to be “normal”! Experience shows that the “Aeromodeller” starting recommendations are entirely appropriate. Set the prop at "10 to 4", get just a little fuel into the engine and don’t so much flick the prop as hit it after checking that you’re not in a hydraulic lock condition or anywhere close to it. Hitting the prop in that condition would be fatal to a Bambi! When cold, the Bambi seems to like being started rather "wet", with the compression backed off, advancing slowly to the desired running setting. After that, it will usually restart on the first flick (or clobber), with no change to the settings. The needle is un-critical and you do get the chance to open it again after going too lean (some engines just stop abruptly at this point). By late 1954 the Bambi was being distributed in the USA by American Telasco of Huntington, New York, selling for a price of $24.95. This was over 5 times the price of a normal .049 glow-plug motor - only the McCoy 60 matched this price in the contemporary America's Hobby Center (AHC) catalogue! The distributors were clearly pricing the Bambi on the basis of its novelty value - you really had to be under the spell of its unprecedentedly tiny size to be prepared to pay that much for one. The Bambi on Test

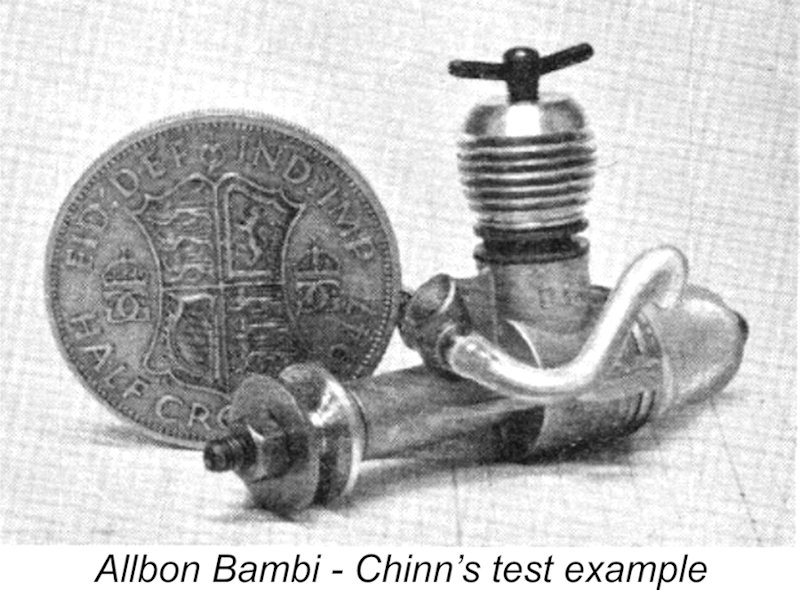

Despite “Aeromodeller’s” apparent involvement in the development and testing of the Bambi, the rival English aeromodelling magazine “Model Aircraft” beat “Aeromodeller” to press with their "official" review of the Bambi. Peter Chinn’s test appeared in June 1954.

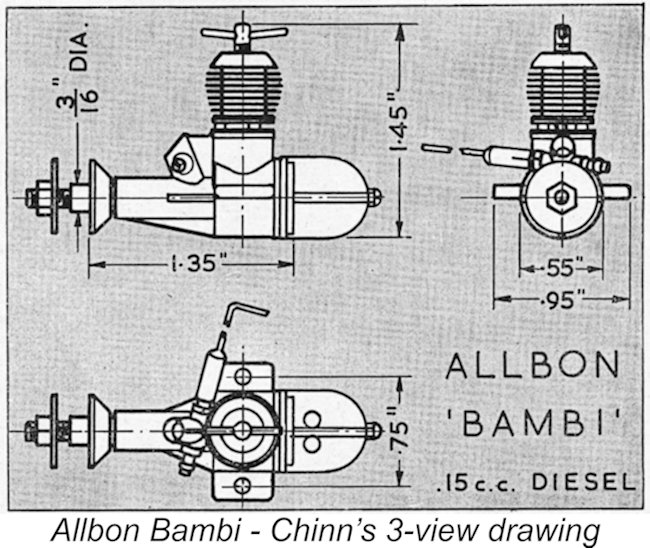

The dimensioned three-views which accompanied this review clearly showed a 3/16 in. dia. boss protruding from the centre of the plain un-knurled prop driver - a feature which was apparently confined to early examples of the engines. In addition, the example tested by Chinn appears to have a plain un-anodized 8-fin cooling jacket. These features are undoubtedly indicative of the test engine's very early position in the Bambi's production sequence, since almost all regular production models featured red-anodized 6-fin cooling jackets. Unusually, Chinn refrained from publishing a full power curve, confining himself to an estimate of an output of perhaps 0.010 BHP @ 12,000 rpm. The point was emphasized that both Chinn and the manufacturers were in agreement that the Bambi was not an engine for a beginner.

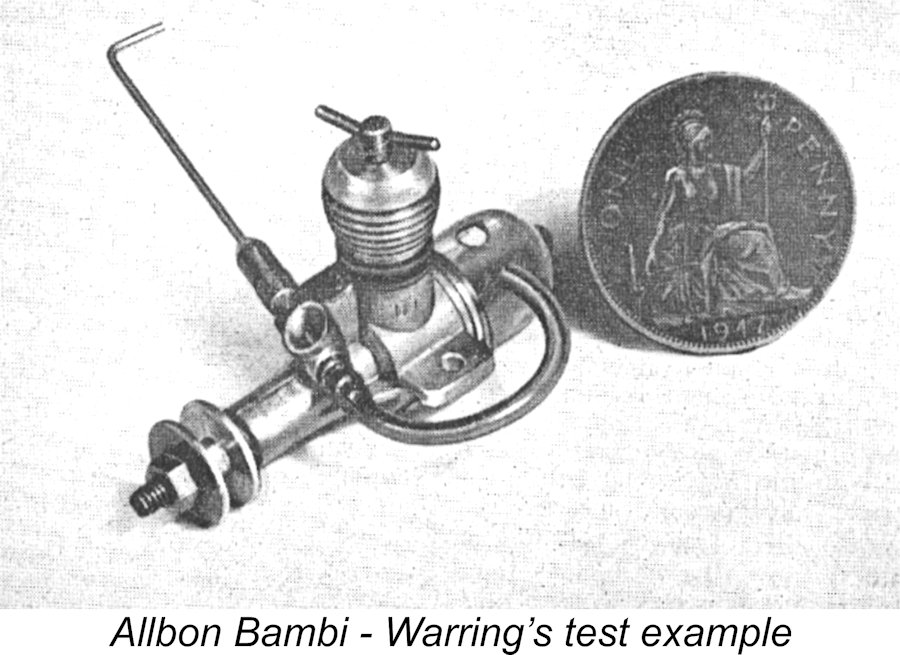

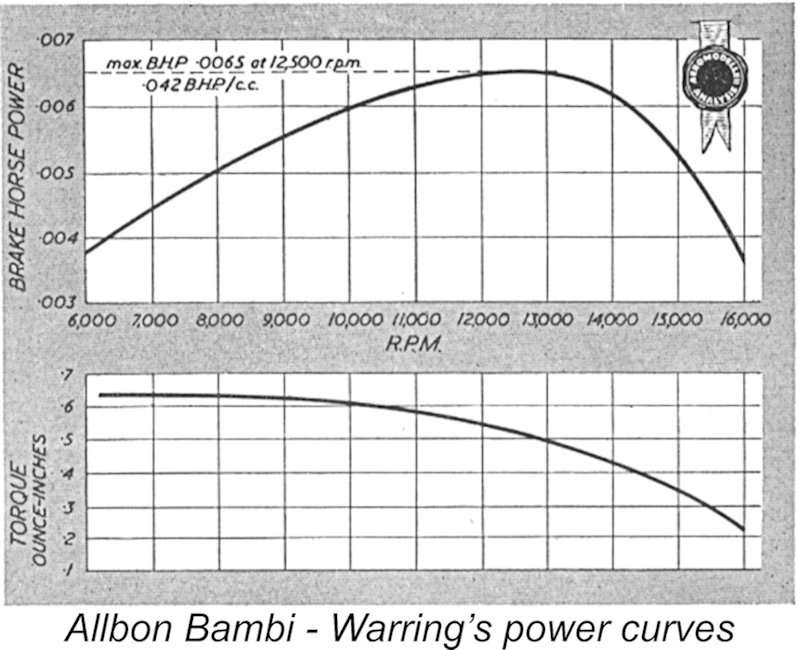

This test report is noteworthy for two reasons. First, the subject was once again headlined as the Allbon Bambi, even though all Davies-Charlton ads clearly identified it as a D-C engine. Second, this review was to have been the first of a new series employing an eddy-current dynamometer for torque measurement. This high-tech device was intended to replace the equipment bequeathed to engine testers by our old friend Lawerence H. Sparey when noise complaints in his North London residential area forced him out of the post of chief engine tester for “Aeromodeller” – a story unto itself! The problem was that with only one-half of one inch-ounce of torque, there was just no way that the Bambi was going to spin the dyno rotor!

The review noted the development progression from 0.10 cc to 0.15 cc as Chinn had done earlier. It also included Warring’s recommended starting procedure as outlined previously. In an admirable example of typical British understatement, Warring noted that "...we would hesitate to recommend a Bambi for a relatively inexperienced modeller..".

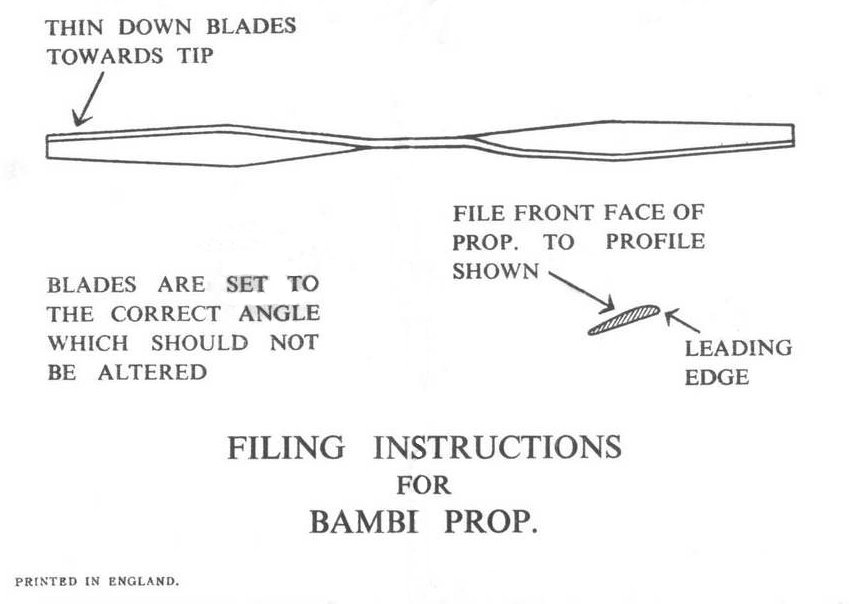

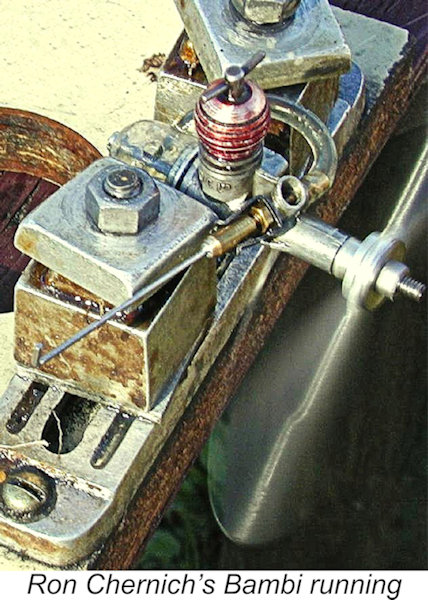

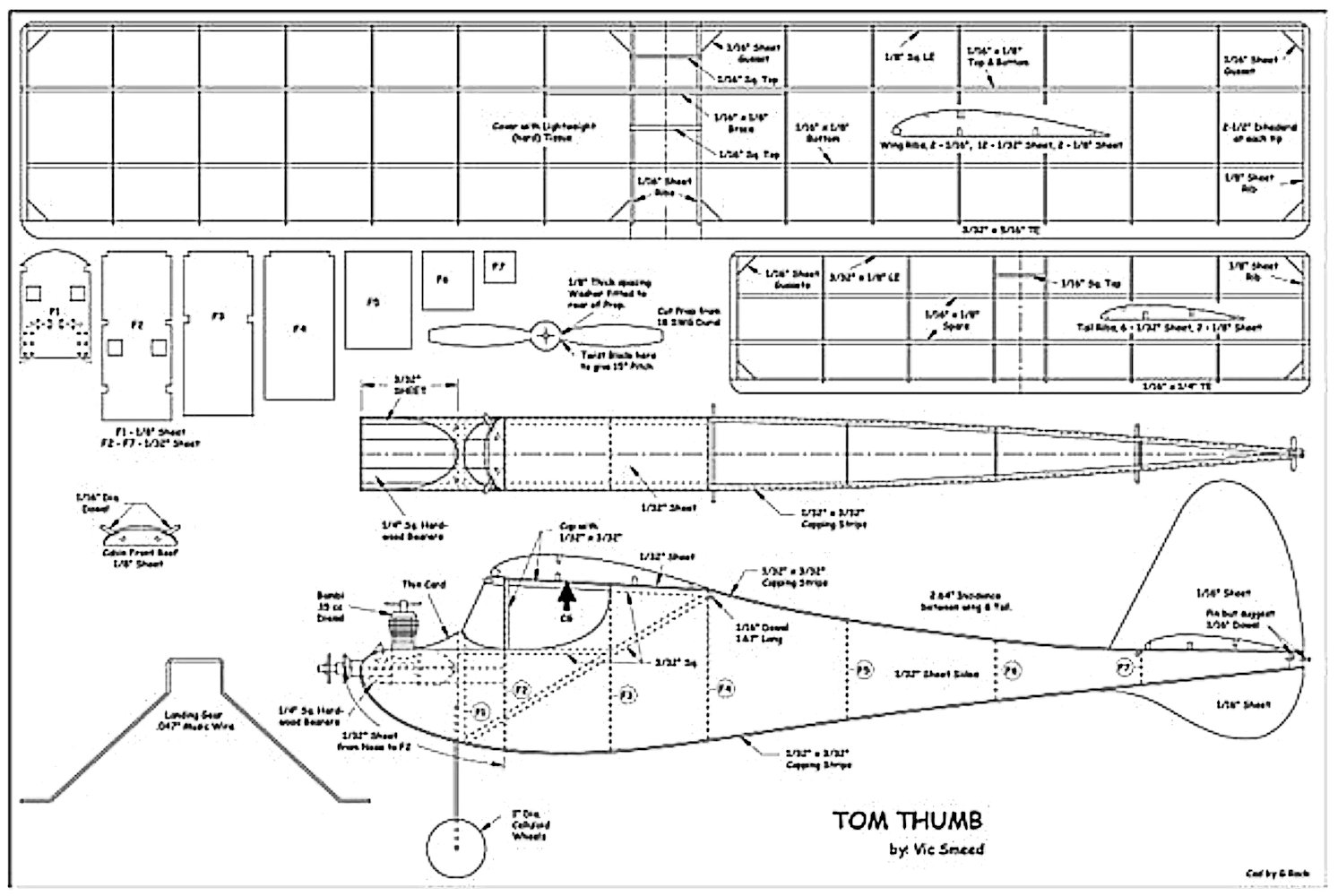

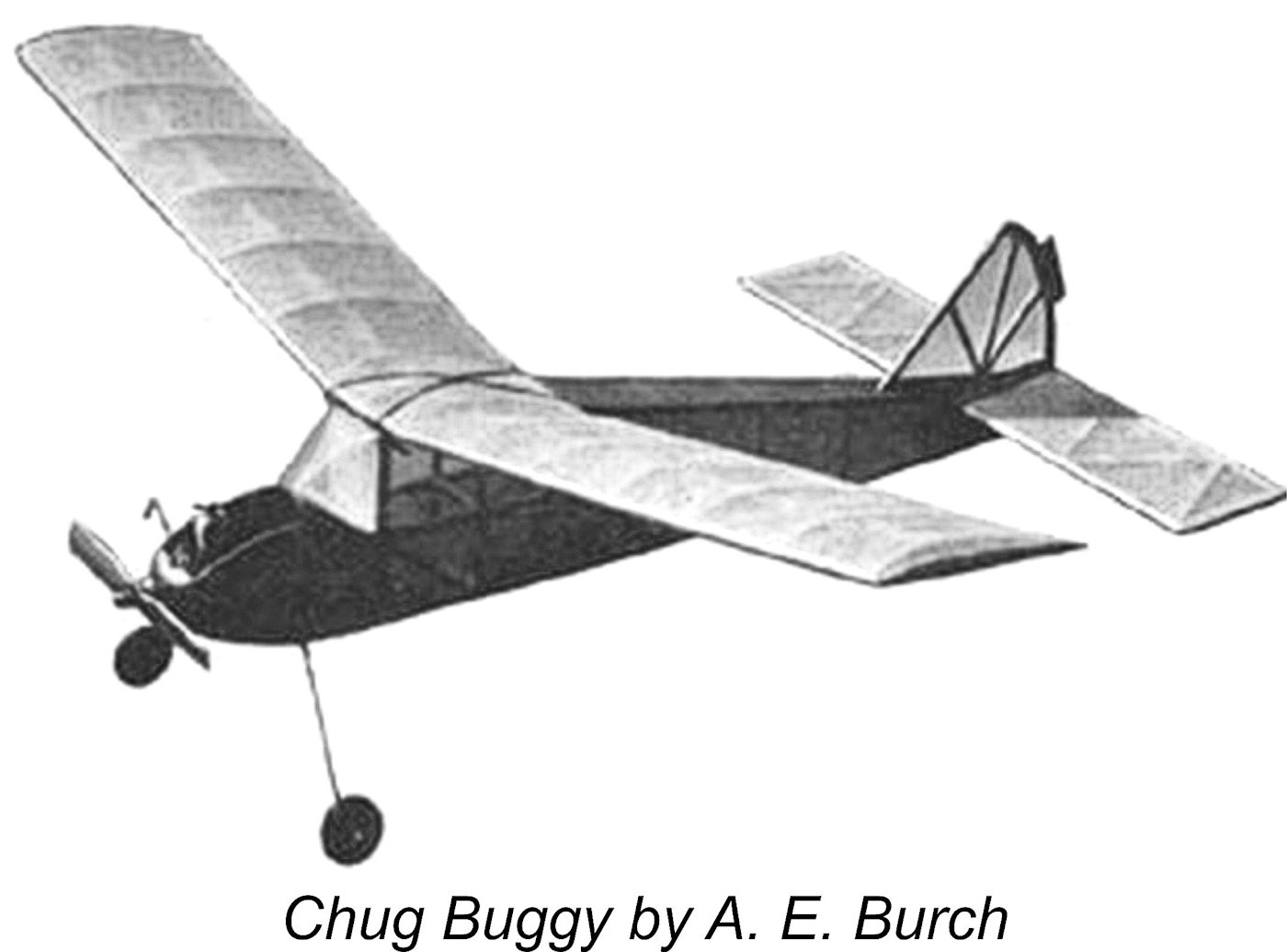

The plan is significant in that it shows the airscrew configuration that the “Aeromodeller” staff testers had finally settled upon as optimum for the engine: about 4 in. diameter and 3/8 in. wide at the half-blade points. This airscrew was made from Not to be out-done, "Model Aircraft" published a plan for a simple 24 in. wingspan cabin model called the "Chug Buggy" in their June 1954 issue alongside Peter Chinn's test of the Bambi. This was designed by A. E. Burch, who had apparently been working on it for some time in anticipation of the Bambi's appearance - the original prototype example had been powered by a 0.201 cc K Hawk Mk. II diesel. Finally, a review and test of the Bambi for American enthusiasts appeared in the February 1955 issue of "Flying Models". This review focused on the engine's construction and handling characteristics, pretty much echoing the comments of the earlier British testers. It presented a few prop/RPM figures but did not attempt any estimate of the engine's power output. My own testing of a fine example of the Bambi which had been expertly rebored by my talented mate Dave Jones of Hervey Bay, Queensland, Australia has confirmed that the Bambi is indeed a perfectly useable little engine. Once the right compression and needle valve settings have been established, the engine starts quite readily. Injection of a single drop of fuel into the intake works very well in lieu of a port prime, and it’s best to follow Warring’s recommendations by “hitting” the prop over compression in team-race style to achieve quick results (first checking to make sure that you’re not in or close to a hydraulic lock!). If you do this, the Bambi invariably starts in very short order and is very easy to adjust for best performance, albeit displaying a certain sensitivity to the needle setting. Peter Chinn actually commented upon this latter characteristic.

A Cox 4½x2 works very well indeed with the Bambi as a flight prop, turning at around 10,000 rpm on the ground - about 0.0066 BHP at that speed. This is quite consistent with Warring’s test figures. A Cox 4½x2 cut down and trimmed to 4x2 runs at around 11,400 rpm on the bench - about 0.0076 BHP at that speed. I'd guess that my test engine probably develops around 0.0078 BHP @ 12,000 rpm - fractionally over the 50 BHP/litre mark. That having been noted for the record, the Bambi's peak output is really of little significance - the main point is that it's a perfectly useable little engine which handles far better than its reputation might suggest and would undoubtedly do a very creditable job of flying a small lightweight free flight model. It's by no means as difficult to start as some people seem to believe - once the needle setting is established, it's actually as easy as any other diesel. It just requires extra care in handling due to the very small size of the working components.

Setting aside the issue of practicality, I suspect that most purchasers of the Bambi were attracted as much as anything else by its novelty value - it had an undeniably narrow range of potential applications in real world aeromodelling. It was never a big seller, being produced in modest batches from May 1954 until mid 1959. Its high price doubtless told against its sales potential - you had to be well and truly smitten by its novelty value to be prepared to fork out for one. Unfortunately, accurate production figures are impossible to generate since D-C engines never carried serial numbers. Based upon the apparent number of survivals, it’s estimated very roughly that perhaps 6,000 examples were made at most during the Bambi's 5-year production period - a very low total by D-C standards, but quite a high figure for a micro-diesel of the era. A fair number of those that were produced survive today in quite reasonable condition - the surviving examples generally seem to have experienced very little use, while their novelty appeal saved them from being casually discarded. We latter-day enthusiasts are the beneficiaries of this happy outcome! Model Designs for the Bambi My sincere thanks are due to my valued mate Gordon Beeby for his invaluable assistance in compiling the following section of this article. Gordon's customary trolling of the contemporary media record turned up a number of items which Ron and I had missed. Thanks, mate!

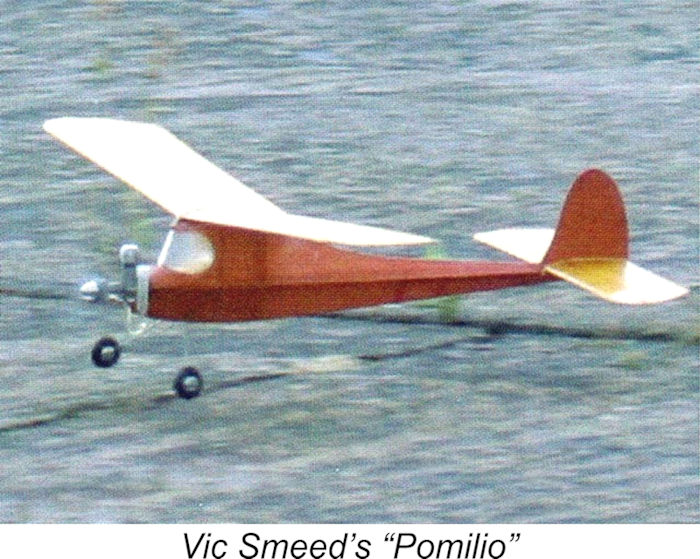

As previously stated, a competing design expressly intended for the Bambi was Vic Smeed’s 22 in. wingspan “Tom Thumb”, which was published in the June 1954 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Other designs for the Bambi were not long in following. A few of these appeared as free full-sized plans in the respective magazines. These included As far as I can discover, the only other contemporary plan published by any magazine for a model designed expressly for the Bambi was a 22¾ in. wingspan free flight scale rendition of the “Luton Minor” designed by Walter E. Mooney. This was published in the June 1958 issue of "Aeromodeller" as an addition to the catalogue of the Aeromodeller Plans Service (Plan no. FSP 697).

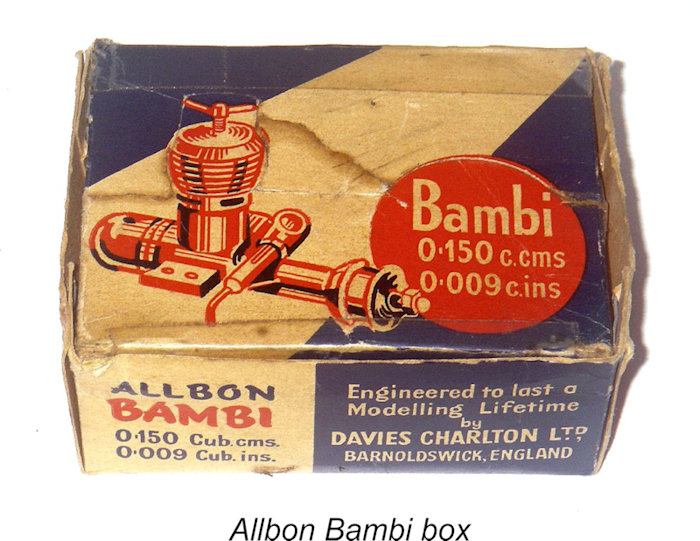

Only one kit designed specifically for the Bambi ever appeared on the market. This was the aforementioned KeilKraft “Dandy”, a free flight sport model boasting an awe-inspiring 21 in. (53 cm) wing span. The first advertisement for this kit appeared in KeilKraft's regular position on the rear cover of the April 1955 issue of “Aeromodeller” (right). The kit appeared again in the KeilKraft ad for the following month, but as far as I can tell this was its final appearance. Clearly the kit failed to inspire any sales attention. Notice in the bottom left corner of the advertisement that KeilKraft identified themselves as the sole UK Distributor for D-C Engines. This provides a clue as to why they might go to the effort of kitting a design for an expert-level engine, requiring expert attention to weight during construction, followed by expert level balance and trimming. Finally, the reader should recall my earlier comment to the effect that tiny diesel engines were initially seen as replacements for rubber power in more or less the same types of model. The "Model News" feature of the March 1956 issue of "Aeromodeller" made specific reference to the increasing popularity of Bambi-powered conversions of models originally intended for rubber power. Small scale model kits from Veron, Keilkraft and Skyleada were cited as being particularly suitable for such conversions, the main criterion apparently being that the selected model should have ample dihedral for stability. End of the Road D-C ads continued to appear on the inside front cover page of every “Aeromodeller” issue (except December) into the 1980's. However, throughout its comparatively short production life, the appearance of the Bambi in these ads was highly irregular. It seems likely that the unsuitability of the Bambi for control-line and R/C applications, coupled with the perceived trickiness of handling such a small engine, resulted in relatively low sales figures, leading D-C Ltd. to target their marketing spend where the return was better. In April 1956, the price of the Bambi was reduced to £3 19s 6d (£3.98), bringing it more into line with the other D-C engines in the sub-one cc range (the 0.76 cc Merlin having been added in October 1954 at a price of only £2 7s 6d (£2.38). The price of the Bambi was further reduced in February 1959 by a massive 2s to £3 17s 6d (£3.88). The final demise of Bambi production/promotion appears to have occurred in mid-1959. The last D-C ad for the Bambi that I was able to locate in the British model press appeared in the June 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller”, although supplies to retailers probably held out somewhat longer. Coincidentally, this final ad Whatever the truth, the formal announcement of the termination of Bambi production finally came in the "Over the Counter" feature in the April 1960 issue of "Model Aircraft", to be followed in May 1960 by a similar announcement in the "Motor Mart" feature in "Aeromodeller". However, it seems almost certain that Bambi production had ended some time previously, with the company attempting to liquidate its residual unsold stocks of the engine through its final advertisements. The Bambi box shown here may provide a clue as to why the engine was colloquially known as the "Allbon Bambi" - it's clearly identified as such on the box, even though D-C Ltd. is cited equally clearly as the manufacturer. Alan Allbon had severed his connection with Davies-Charlton Ltd. in 1955, eventually moving in 1959 from the Isle of Man back to his old stomping grounds in England. There he formed a new partnership, announcing the short-lived but very well-made 0.55 cc Allbon-Sanders A-S 55 diesel. Davies-Charlton soldiered on for another twenty-four years - their last ad appeared in the May 1983 issue of “Aeromodeller”. I’ve recounted the full history of the Davies-Charlton enterprise in a separate article which may be found elsewhere on this website. There are two codas to the Bambi story. First, in 1982 considerable thought was given to the possibility of a revival of the Bambi. Doubtless the company was hoping to take advantage of the revival of interest in the engine among the growing model engine collecting community.

However, the company was advised by its outside pressure die-casting contractor that the long-disused Bambi pressure dies had suffered water damage and needed refurbishing at a cost of over £1500. Considerations of the consequent unit manufacturing cost along with less-than-optimistic long-term sales projections combined to make the project appear uneconomic, causing it to be shelved in early 1982. Russia supplies the second coda to the Bambi story with a reproduction that appeared briefly in the late 1990's. By all reports, this engine was if anything superior to the originals in fits, finish, start-ability and performance. The asking price was over US$100, but the collector market had then become quite inured to figures like this, with original Bambis in reasonable condition then fetching around US$250. Conclusion The Bambi may not have made a lot of money for its manufacturer, but it certainly provided them with a publicity boost, even if it was relatively short-lived. That doesn’t alter the fact that between them, Alan Allbon and the staff at D-C Ltd. had produced one of the classic commercial sub-miniature diesels, and one of which they could be justly proud. It remains a sought-after collectible today and a nice little powerplant which is great fun to run. All things considered, one of the true classics and certainly a “must have” for serious collectors of classic British sports diesels! ___________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First edition by Ron Chernich published on MEN July 2003 This revised edition published November 2025 |

| |

In this article, I’ll share what I know about the smallest-displacement model diesel ever to go into mass production – the Allbon (D-C) Bambi of 0.154 cc (0.0091 cuin.) displacement. This article represents a re-organization and augmentation of an earlier piece about the Bambi which appeared on the late Ron Chernich’s wonderful “

In this article, I’ll share what I know about the smallest-displacement model diesel ever to go into mass production – the Allbon (D-C) Bambi of 0.154 cc (0.0091 cuin.) displacement. This article represents a re-organization and augmentation of an earlier piece about the Bambi which appeared on the late Ron Chernich’s wonderful “ There’s an undeniable fascination attached to working mechanisms of all kinds which are created to be as small as possible while still performing the same functions as their larger-scale relatives. For those of us who take an interest in model internal combustion (I/C) engines, this is particularly true.

There’s an undeniable fascination attached to working mechanisms of all kinds which are created to be as small as possible while still performing the same functions as their larger-scale relatives. For those of us who take an interest in model internal combustion (I/C) engines, this is particularly true. reductions in engine displacement, considerations of overall power-to-weight ratio led to the .099 cuin. (1.63 cc) displacement being generally viewed by commercial manufacturers of spark ignition engines as the practical lower limit for actual use in the field. However, a few mega-talented model engineers produced experimental one-off working sparkies at far smaller displacements, just to see if they could!

reductions in engine displacement, considerations of overall power-to-weight ratio led to the .099 cuin. (1.63 cc) displacement being generally viewed by commercial manufacturers of spark ignition engines as the practical lower limit for actual use in the field. However, a few mega-talented model engineers produced experimental one-off working sparkies at far smaller displacements, just to see if they could! In a separate article to be found elsewhere on this website, I’ve summarized the development history of the

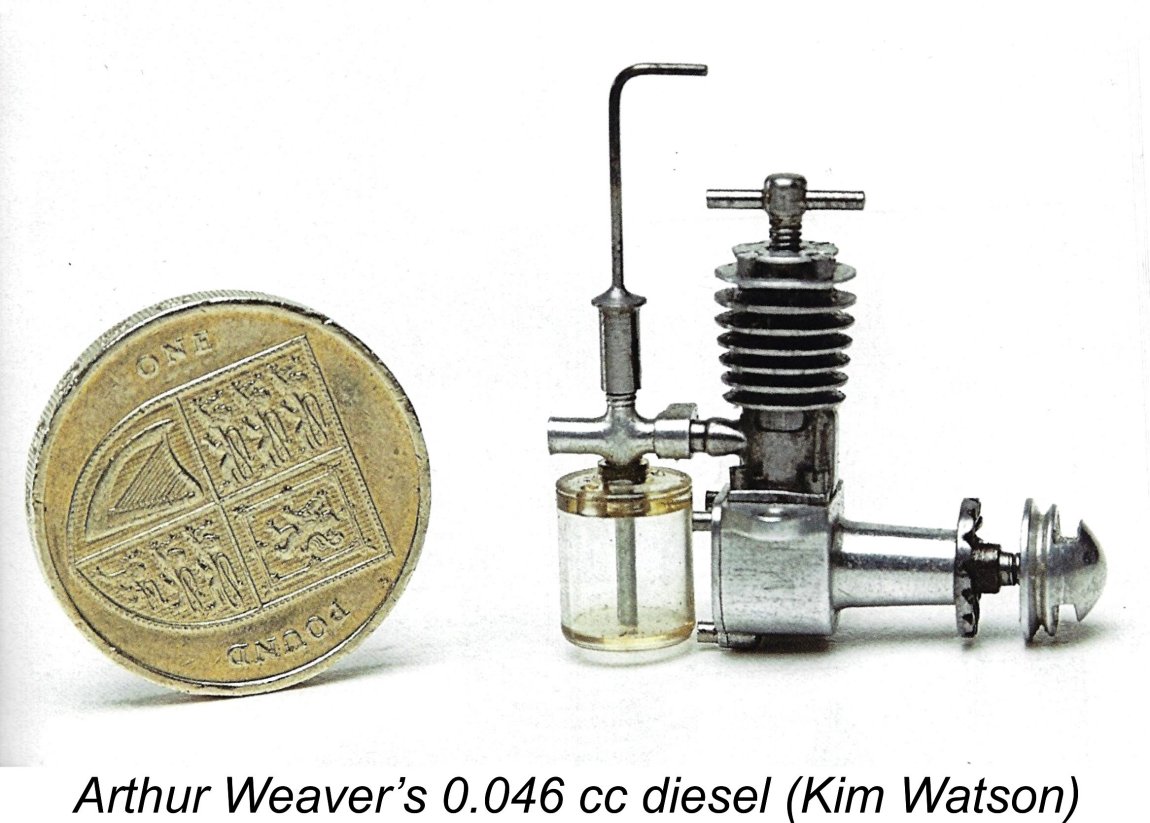

In a separate article to be found elsewhere on this website, I’ve summarized the development history of the  During the latter half of the 1940’s and the early 1950’s, a number of talented British model engineers experimented with the construction of very small diesel engines. These individuals included H.H. Groves (0.173 cc - 1946); R. Trevithick (0.251 cc - 1946); Arthur Weaver (0.046 cc - 1948); and R.G. Cameron (0.15 cc – 1952). Even Arnold Hardinge of Mills Brothers had a go, producing two 0.2 cc mini-Mills diesels in prototype form in 1948. All of these engines were sideport diesels which reportedly ran well. However, none of them ever entered series production.

During the latter half of the 1940’s and the early 1950’s, a number of talented British model engineers experimented with the construction of very small diesel engines. These individuals included H.H. Groves (0.173 cc - 1946); R. Trevithick (0.251 cc - 1946); Arthur Weaver (0.046 cc - 1948); and R.G. Cameron (0.15 cc – 1952). Even Arnold Hardinge of Mills Brothers had a go, producing two 0.2 cc mini-Mills diesels in prototype form in 1948. All of these engines were sideport diesels which reportedly ran well. However, none of them ever entered series production. The honour of being the first British micro-diesel to enter series production on a commercial basis was the 0.193 cc

The honour of being the first British micro-diesel to enter series production on a commercial basis was the 0.193 cc  However, the initial enthusiasm for micro-diesels was not to last. In large part, this was due to the fact that control-line flying was becoming dominant in the British aeromodelling field (how times change!), with increasing attention being paid to the development of R/C flying, then still in its pioneering phase. Neither of these disciplines were well-matched to the use of micro-diesels. By mid-1951 all of the commercial British sub-miniatures mentioned above had been withdrawn or abandoned for one reason or another. Indeed, by that time neither the "K" Model Engineering Co., makers of the Hawk Mk. II nor Kalper manufacturers Seymour, Hylda & Co. were still in existence.

However, the initial enthusiasm for micro-diesels was not to last. In large part, this was due to the fact that control-line flying was becoming dominant in the British aeromodelling field (how times change!), with increasing attention being paid to the development of R/C flying, then still in its pioneering phase. Neither of these disciplines were well-matched to the use of micro-diesels. By mid-1951 all of the commercial British sub-miniatures mentioned above had been withdrawn or abandoned for one reason or another. Indeed, by that time neither the "K" Model Engineering Co., makers of the Hawk Mk. II nor Kalper manufacturers Seymour, Hylda & Co. were still in existence. Development work on the Bambi commenced in the second half of 1953. Although the development of this engine was kept pretty much under wraps as far as the public were concerned, the staff of “Aeromodeller” magazine were clearly made privy to the secret at an early stage, becoming closely involved with the engine’s field testing. They knew that this would be a “special” engine, hence laying plans for a special media launch while development was still ongoing.

Development work on the Bambi commenced in the second half of 1953. Although the development of this engine was kept pretty much under wraps as far as the public were concerned, the staff of “Aeromodeller” magazine were clearly made privy to the secret at an early stage, becoming closely involved with the engine’s field testing. They knew that this would be a “special” engine, hence laying plans for a special media launch while development was still ongoing. behind the scenes for all concerned. It all started in November 1953 when the accompanying full page placement (left) appeared in the front advertising section of “Aeromodeller”, showing an image of the engine without naming either the engine or its manufacturer. This placement was quite distinct from the regular D-C advertisement, which appeared elsewhere in the magazine, evidently being placed by the magazine itself. The “Aeromodeller” ad invited readers to identify the engine's manufacturer and suggest a name. The only technical information included was the mystery engine’s displacement, which was quoted as 0.10 cc.

behind the scenes for all concerned. It all started in November 1953 when the accompanying full page placement (left) appeared in the front advertising section of “Aeromodeller”, showing an image of the engine without naming either the engine or its manufacturer. This placement was quite distinct from the regular D-C advertisement, which appeared elsewhere in the magazine, evidently being placed by the magazine itself. The “Aeromodeller” ad invited readers to identify the engine's manufacturer and suggest a name. The only technical information included was the mystery engine’s displacement, which was quoted as 0.10 cc. The identification of the manufacturer should not have posed any significant challenge given the strong family resemblance to the 0.55 cc Allbon (D-C) Dart. Even so, the competition was necessarily run from “Aeromodeller's” editorial office, as inviting people to send their cards and letters to D-C Ltd. would have been a dead give-away!

The identification of the manufacturer should not have posed any significant challenge given the strong family resemblance to the 0.55 cc Allbon (D-C) Dart. Even so, the competition was necessarily run from “Aeromodeller's” editorial office, as inviting people to send their cards and letters to D-C Ltd. would have been a dead give-away! and the relative innocence of the times, it probably didn’t matter all that much. Besides, the competition had been initiated under the auspices of “Aeromodeller” magazine rather than D-C Ltd., so it was really the magazine’s responsibility to present the final announcement while maintaining an air of impartiality.

and the relative innocence of the times, it probably didn’t matter all that much. Besides, the competition had been initiated under the auspices of “Aeromodeller” magazine rather than D-C Ltd., so it was really the magazine’s responsibility to present the final announcement while maintaining an air of impartiality. In the same January 1954 issue, the “Trade Notes” column carried the official press release for the Bambi (right). Once again, we are told that the winner of the competition - an un-named Norwegian - had been selected by D-C Ltd., and that the engine would thenceforth be known as the Allbon Bambi. Oops! While the case of the D-C Spitfire says Allbon, the embossing on the Allbon Bambi clearly says D-C Ltd! So either the attachment of the Allbon name to the engine was a tribute by D-C to the designer, or it was a mistake that “Aeromodeller” was to repeat later when they published a review of the engine.

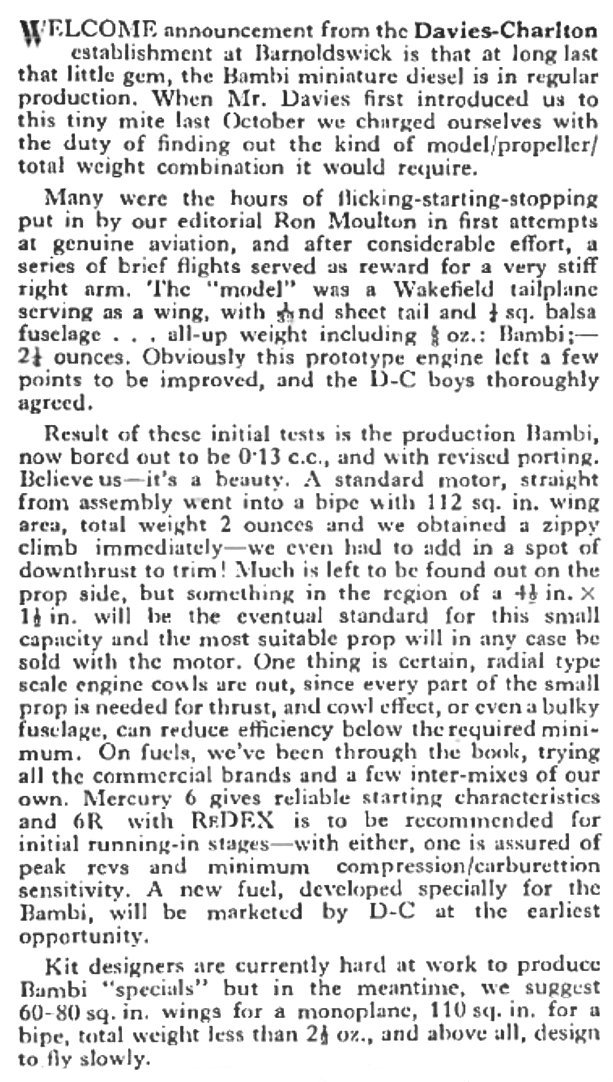

In the same January 1954 issue, the “Trade Notes” column carried the official press release for the Bambi (right). Once again, we are told that the winner of the competition - an un-named Norwegian - had been selected by D-C Ltd., and that the engine would thenceforth be known as the Allbon Bambi. Oops! While the case of the D-C Spitfire says Allbon, the embossing on the Allbon Bambi clearly says D-C Ltd! So either the attachment of the Allbon name to the engine was a tribute by D-C to the designer, or it was a mistake that “Aeromodeller” was to repeat later when they published a review of the engine. Despite the suggestion of a late February release of the Bambi, all went very quiet for the next three months. It wasn’t until May 1954 that the engine got another media mention, once again in “Trade Notes” (left). Reading between the lines here, we can infer that the gestation had been a troubled one, with some frenzied testing and development being carried out both at D-C and by “Aeromodeller” staffer Ron Moulton. Apparently the flight-tested prototype provided "...brief flights served as reward for a very stiff right arm." In other words, the prototype Bambi could not sustain so much as a powered glide!

Despite the suggestion of a late February release of the Bambi, all went very quiet for the next three months. It wasn’t until May 1954 that the engine got another media mention, once again in “Trade Notes” (left). Reading between the lines here, we can infer that the gestation had been a troubled one, with some frenzied testing and development being carried out both at D-C and by “Aeromodeller” staffer Ron Moulton. Apparently the flight-tested prototype provided "...brief flights served as reward for a very stiff right arm." In other words, the prototype Bambi could not sustain so much as a powered glide! engine now sported a conventional Y-style comp screw tommy-bar along with the metal prop devised by “Aeromodeller” staff ("tweak pitch for maximum climb"). It's hard to say from the black and white magazine picture, but it appears that the cooling jacket may be plain aluminum. It certainly has eight fins, while production engines had six.

engine now sported a conventional Y-style comp screw tommy-bar along with the metal prop devised by “Aeromodeller” staff ("tweak pitch for maximum climb"). It's hard to say from the black and white magazine picture, but it appears that the cooling jacket may be plain aluminum. It certainly has eight fins, while production engines had six. The production version of the Bambi first appeared in D-C’s advertising in June 1954 (left). Rather surprisingly given all of the fanfare which had attended its development, the engine’s initial appearance was a very restrained and low-key affair. Perhaps the comparatively high cost of the engine was a factor given that the January “Trade Notes” entry had suggested that the price "...might be slightly more than a Dart..." This turned out to be an understatement - although the price was reduced some years later, the initial retail price was cited as £5 8s 11d (£5.45) including tax. By contrast, the Dart was offered at a price of only £3 4s 2d (£3.21). The Bambi was definitely not a low-priced engine!

The production version of the Bambi first appeared in D-C’s advertising in June 1954 (left). Rather surprisingly given all of the fanfare which had attended its development, the engine’s initial appearance was a very restrained and low-key affair. Perhaps the comparatively high cost of the engine was a factor given that the January “Trade Notes” entry had suggested that the price "...might be slightly more than a Dart..." This turned out to be an understatement - although the price was reduced some years later, the initial retail price was cited as £5 8s 11d (£5.45) including tax. By contrast, the Dart was offered at a price of only £3 4s 2d (£3.21). The Bambi was definitely not a low-priced engine! cylinder assembly was the same as the complete price for a

cylinder assembly was the same as the complete price for a

Naturally, such a tiny engine quickly attracted the attention of the resident engine testers of the day - people were curious to learn if it was just a gimmick or was actually a useable model powerplant. Both Peter Chinn and Ron Warring of “Model Aircraft” and “Aeromodeller” respectively answered this question very clearly, stating that while it needed a bit of knowing to get the starting technique down pat, once the right approach was mastered and the control settings established it was as easy to start as any other small diesel, also running very well indeed. Latter-day experience bears out this assessment completely.

Naturally, such a tiny engine quickly attracted the attention of the resident engine testers of the day - people were curious to learn if it was just a gimmick or was actually a useable model powerplant. Both Peter Chinn and Ron Warring of “Model Aircraft” and “Aeromodeller” respectively answered this question very clearly, stating that while it needed a bit of knowing to get the starting technique down pat, once the right approach was mastered and the control settings established it was as easy to start as any other small diesel, also running very well indeed. Latter-day experience bears out this assessment completely.  Chinn’s review also named the engine as the Allbon Bambi, possibly due to a desire on Chinn’s part that his friend Alan Allbon (rather than D-C Ltd.) should receive the credit due to him for the engine’s design. Chinn also noted the displacement progression from 0.1 cc to 0.136 cc and finally to 0.154 cc. He indulged in a degree of overkill in terms of decimal precision to give the bore as 0.2188 inch (7/32 in. to 4 decimal places), with the stroke at 0.250 inch. The weight was given as 5/8 oz. (17.2 gm).

Chinn’s review also named the engine as the Allbon Bambi, possibly due to a desire on Chinn’s part that his friend Alan Allbon (rather than D-C Ltd.) should receive the credit due to him for the engine’s design. Chinn also noted the displacement progression from 0.1 cc to 0.136 cc and finally to 0.154 cc. He indulged in a degree of overkill in terms of decimal precision to give the bore as 0.2188 inch (7/32 in. to 4 decimal places), with the stroke at 0.250 inch. The weight was given as 5/8 oz. (17.2 gm).  Ron Warring went a little further in his

Ron Warring went a little further in his  Accordingly, Warring was forced to use some kind of reaction beam torque measurement system to extract his torque/RPM figures, which must necessarily be regarded as somewhat speculative. On the basis of these figures, he published a power curve which reflected a measured output of around 0.0065 BHP @ 12,500 rpm.

Accordingly, Warring was forced to use some kind of reaction beam torque measurement system to extract his torque/RPM figures, which must necessarily be regarded as somewhat speculative. On the basis of these figures, he published a power curve which reflected a measured output of around 0.0065 BHP @ 12,500 rpm. In their June 1954 issue, “Aeromodeller” had published plans for a Vic Smeed free flight model called the "

In their June 1954 issue, “Aeromodeller” had published plans for a Vic Smeed free flight model called the "

Experience shows that the engine peaks at somewhere around 12,000 rpm, at which speed the best flight performance is reportedly obtained. As long as it’s propped to stay at or slightly below this speed in the air, the engine has plenty of power to fly a small lightweight free flight model like the “

Experience shows that the engine peaks at somewhere around 12,000 rpm, at which speed the best flight performance is reportedly obtained. As long as it’s propped to stay at or slightly below this speed in the air, the engine has plenty of power to fly a small lightweight free flight model like the “ A word of warning in the latter context - do not be tempted to try an electric starter on a Bambi (or indeed on any other sub-miniature diesel)! Protection of the tiny working components requires you to constantly check that you're nowhere near a hydraulic lock condition. Only a finger can provide the required continual feedback. One of my acquaintances ignored this advice and ended up with a broken crankshaft - the engine hydraulic-locked and stopped, but the starter and prop didn't! I had another Bambi through my hands which had suffered a broken wrist pin from the same cause. I've also heard of several Ronald Valentine miniatures which have suffered failures due to the use of electric starters. Steer well clear!! A lightweight spring starter is a far safer proposition, although the engine is an easy hand-starter once the settings are established.

A word of warning in the latter context - do not be tempted to try an electric starter on a Bambi (or indeed on any other sub-miniature diesel)! Protection of the tiny working components requires you to constantly check that you're nowhere near a hydraulic lock condition. Only a finger can provide the required continual feedback. One of my acquaintances ignored this advice and ended up with a broken crankshaft - the engine hydraulic-locked and stopped, but the starter and prop didn't! I had another Bambi through my hands which had suffered a broken wrist pin from the same cause. I've also heard of several Ronald Valentine miniatures which have suffered failures due to the use of electric starters. Steer well clear!! A lightweight spring starter is a far safer proposition, although the engine is an easy hand-starter once the settings are established.

announced yet another price reduction to £3 15s 6d (£3.78) along with price adjustments to all the other engines in the D-C range as well. Sadly, this was clearly insufficient to save the Bambi. It's highly likely that actual production had ceased as of mid-1959.

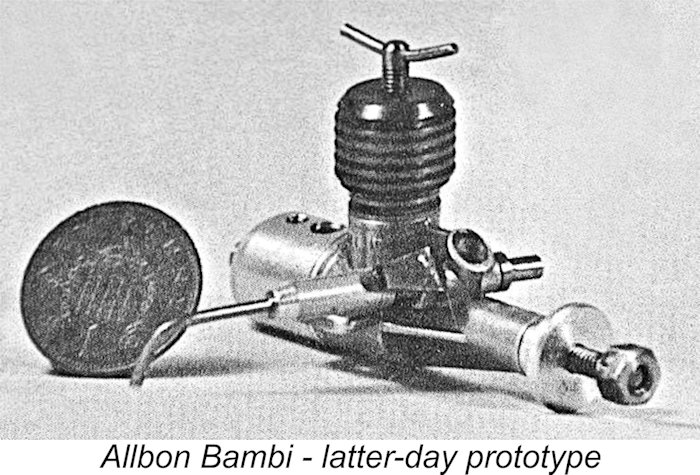

announced yet another price reduction to £3 15s 6d (£3.78) along with price adjustments to all the other engines in the D-C range as well. Sadly, this was clearly insufficient to save the Bambi. It's highly likely that actual production had ceased as of mid-1959.  From surviving correspondence between former Davies-Charlton Production Manager and later Managing Director Bill Callow and the late David Owen, it appears that the company did manage to make a new mold for the gravity die-casting of prototype Bambi crankcases at their own facility, producing a few prototypes of the revived Bambi such as the one pictured here (taken from Mike Clanford's well-known

From surviving correspondence between former Davies-Charlton Production Manager and later Managing Director Bill Callow and the late David Owen, it appears that the company did manage to make a new mold for the gravity die-casting of prototype Bambi crankcases at their own facility, producing a few prototypes of the revived Bambi such as the one pictured here (taken from Mike Clanford's well-known