|

|

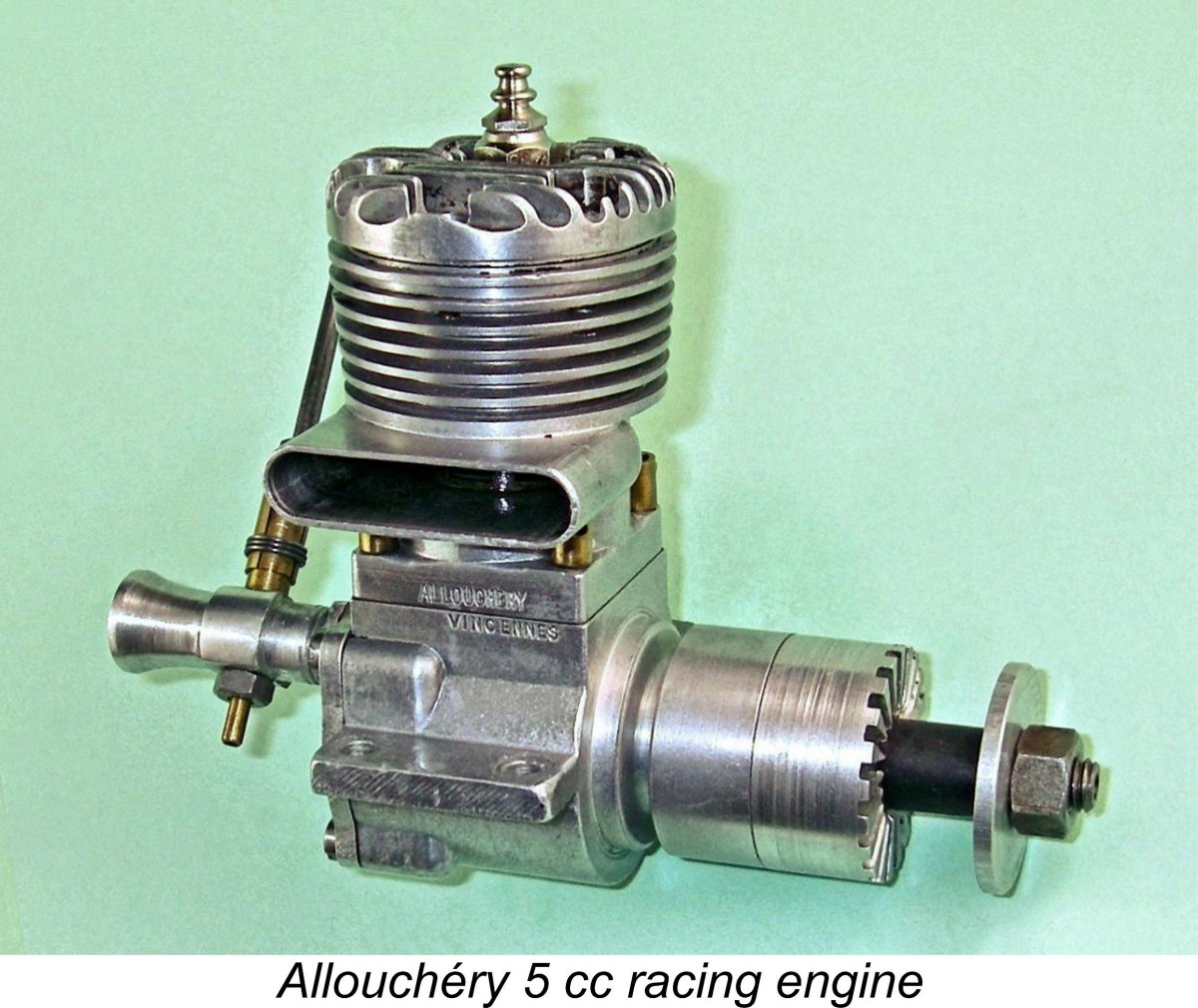

Un Oiseau Rare - the Allouchéry 5 cc Racing Engine

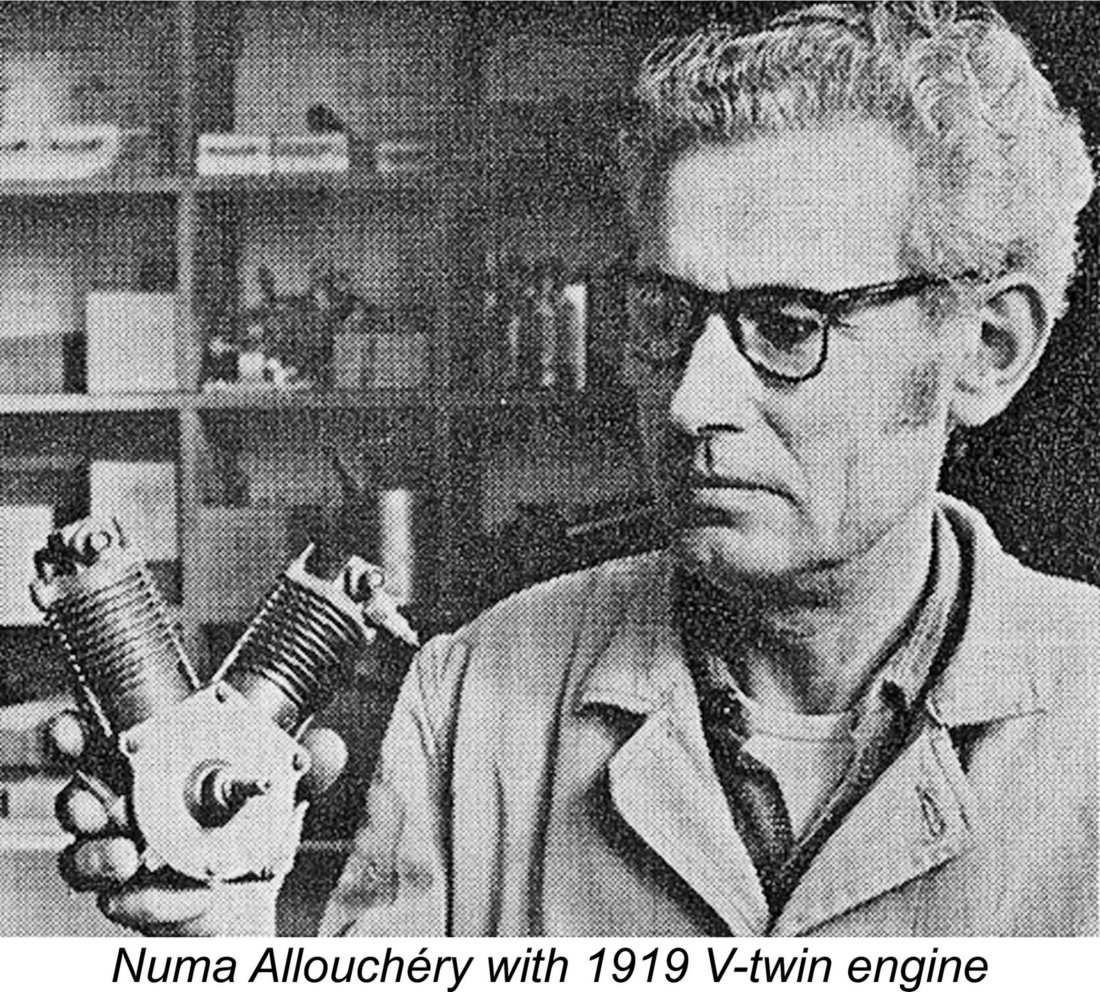

In planning this article, I initially didn’t intend to go into a detailed history of the Allouchéry range. The engines received quite comprehensive photographic coverage in Adrien Maeght's outstanding book ”Les Moteurs Modelés réduits Francais” (French Model Engines). Although by no means free from error, Maeght's book is an essential reference for anyone interested in French model engines. My intention was simply to focus on the 5 cc racing model while recommending that those interested in a broader overview of the range should refer to more comprehensive sources. However, as I considered the matter more closely, it became evident that at least a summary of the marque's history was essential in order to add some context to the forthcoming discussion relating to the dating of our main subject, the Allouchéry 5 cc racing engine. I also uncovered a number of significant errors in the engine's description in Maeght's book. Accordingly, I changed my outline to include the following historical summary of the Allouchéry marque. Believe me, it is relevant! My development of this summary was greatly informed by the information on the range which was posted on the readily-accessible Retroplane model engine forum by the well-known French collector Michel Rosanoff, a highly valued friend and collaborator. My thanks to Maris Dislers, Ken Croft and Pierre Alberola for pointing me to this fascinating resource in the first place, as well as to Michel for making this information freely available and graciously allowing me to use images extracted from his site. The Allouchéry Range - an Overview The Allouchéry range was among the first new model engine marques to emerge in occupied France during WW2, making its market debut in late 1943. It was established by Prosper Allouchéry, who had begun making model engines for his own use and that of a few of his friends as early as 1940 while apparently working full time in the glass-making industry. The positive reception accorded to these units led Allouchéry to decide to put his model engine construction activities on a commercial basis beginning in 1943. He established a workshop at 15 Rue du Levant in the eastern Parisian suburb of Vincennes, near the historic Royal fortress of the Château de Vincennes. Oddly enough, this street appears to have been either built over or renamed - I can find no trace of it today on any map or in any Vincennes street directory.

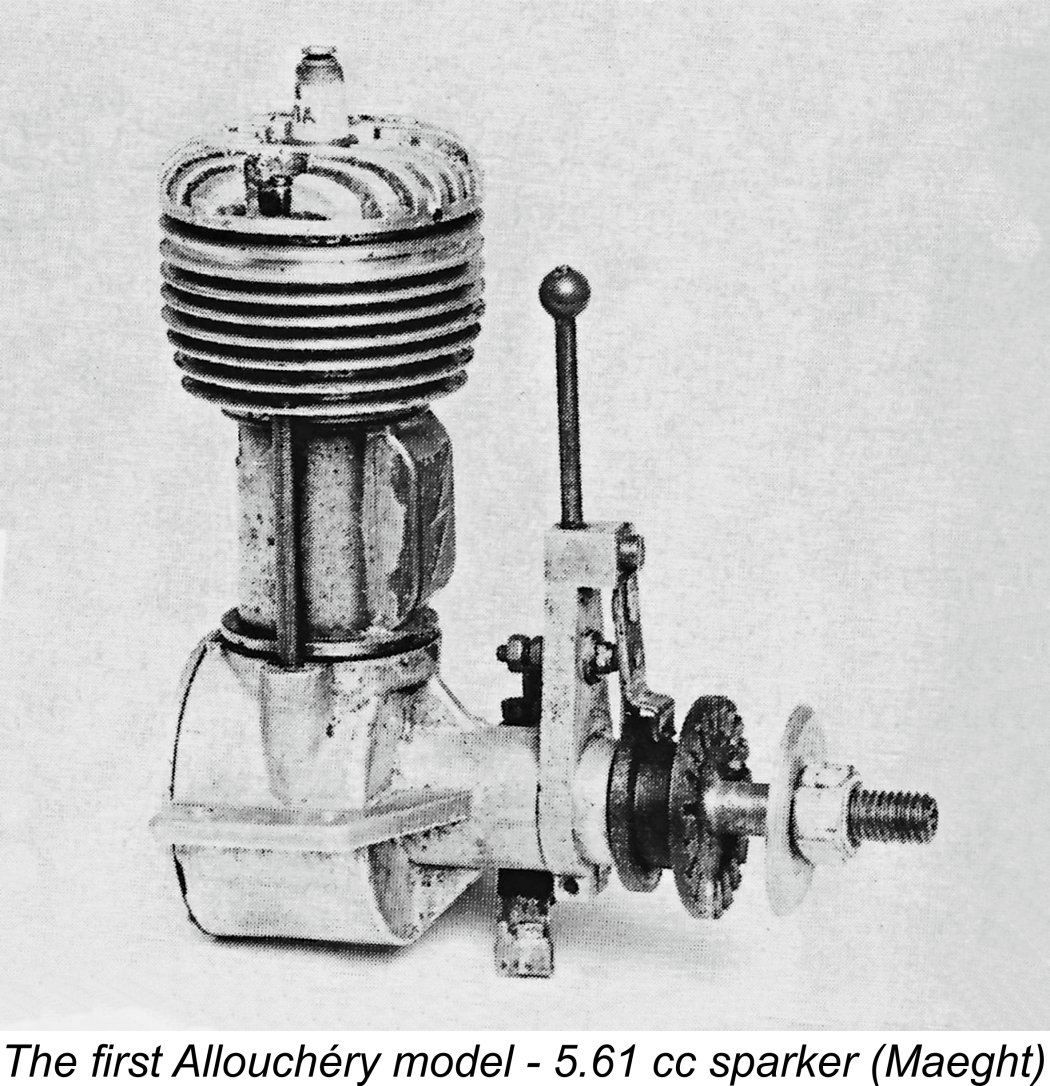

This workshop was tiny, measuring around 3 metres by 4 metres. It was almost certainly housed in Prosper Allouchéry's residence on what was characterized as a quiet street in Vincennes. Despite its small size, the workshop somehow managed to acommodate Prosper Allouchéry, his brother Numa and an assistant, all three of whom worked on the production of the engines. Allouchéry’s first commercial model was a 5.61 cc (0.342 cuin.) crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) spark ignition unit which made its market debut in November 1943. It was a little unusual in that the FRV intake protruded horizontally to the left, thus mirroring the earlier right-hand layout of the American Cannon engines. Although this design was sold in relatively small numbers due to production constraints, its quality and performance ensured a sufficiently positive reception that Prosper Allouchéry was encouraged to embark upon the expansion of the range. He next turned his mind towards the development of a less complex unit in a potentially more popular displacement category.

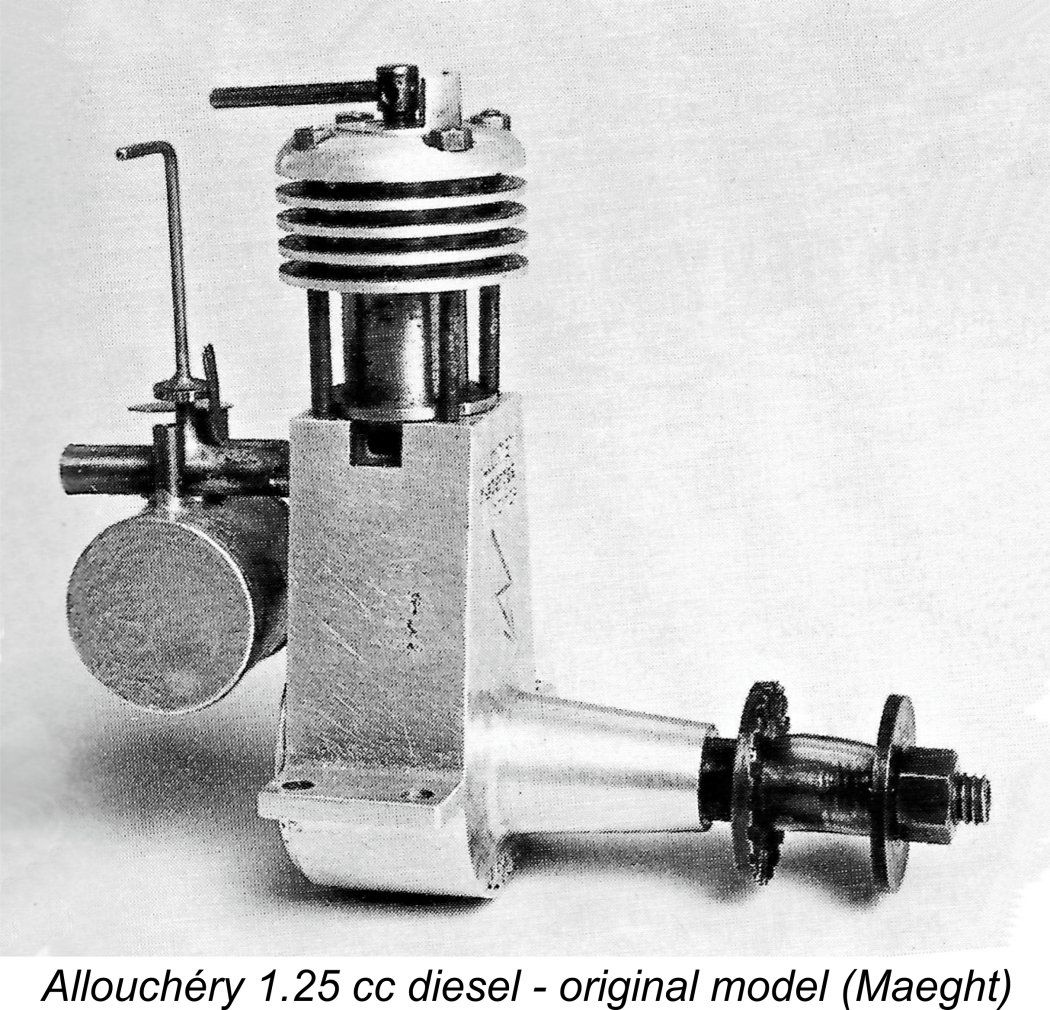

Naturally, both French aeromodelling enthusiasts and model engine constructors were greatly intrigued by this new technology which allowed modellers to dispense with the heavy and undependable spark ignition support systems used up to that point in time. These included Prosper Allouchéry, whose next design was the one that really established him as a significant French manufacturer. This was his soon-to-be-famous 1.25 cc sideport diesel of early 1944. This fine little engine was based in principle upon the iconic 1941 Dyno 2 cc model from Switzerland. In turn, it almost certainly exerted some influence over the design of the Mills 1.3 over in England. The early examples of the Allouchéry 1.25 cc model did not bear the stamped designation "Allouchéry Vicennes" which appeared on the later engines. Michel Rosanoff believes that this inscription appeared on the engines to clearly distinguish them from the STAB 1.25 cc model which appeared in the summer of 1945 (not 1944 as cited in Maeght's book).The STAB was first advertised in September 1945 in both “M.R.A” and "L'air Pour Les Jeunes" magazines. It was around this time that the designation "Allouchéry Vicennes" began to appear on the Allouchéry engines. The apparent influence of the Allouchéry 1.25 cc model on the design of the Mills 1.3 appears not to have escaped Prosper Allouchéry's notice! In the previously-cited French-language article by "R.F.", he is directly quoted as follows: "Generally speaking, small craftsmen should be protected against all manner of sharks who without being technicians themselves loot them without scruple, copy their best models and artificially raise the selling prices. I was recently the victim of this kind of despoilation, but a legal action would take too much time and too much money, with probably an unsatisfactory result ......... .."

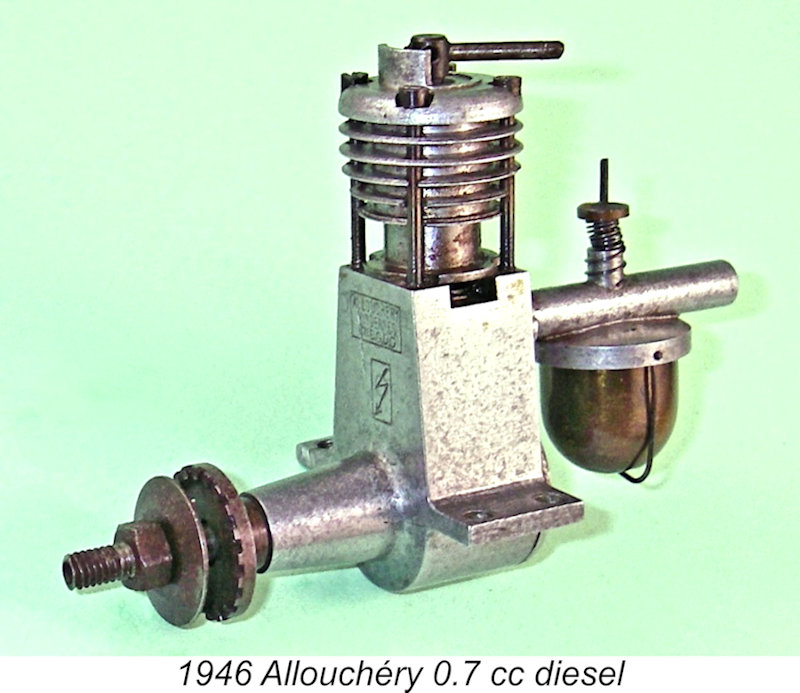

The design was thus available in England to serve as a source of design inspiration, and perhaps it did exert some level of influence..........but really, so what?!? Almost all model engines reflect the designs of their predecessors to some degree - look at all the Dyno clones from a number of countries. The Allouchéry design owed every bit as much to that of the Dyno as the Mills did to the Allouchéry! So Prosper Allouchéry's complaint smacks of the pot calling the kettle black - he seems to have recognized himself that there was actually no basis for a legal challenge to Mills. In my personal view, a far more positive reaction on Allouchéry's part would have been to take the apparent influence of his design on that of the Mills as a compliment - imitation is surely the most sincere form of flattery! An interesting and seemingly unexpected occurrence during the visit reported in R.F.'s article was the appearance at the workshop of then-famous French filmstar and cabaret singer Henri Garat. He had been experiencing problems relating to his extravagant lifestyle, his marital complexities and his use of cocaine, which were eventually to claim his By this time, the range had expanded considerably. The article noted that both 0.7 cc and 3 cc versions of the 1.25 cc design were in simultaneous production. There was also a crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) 4 cc unit, although this was not mentioned - it may have appeared slightly later.

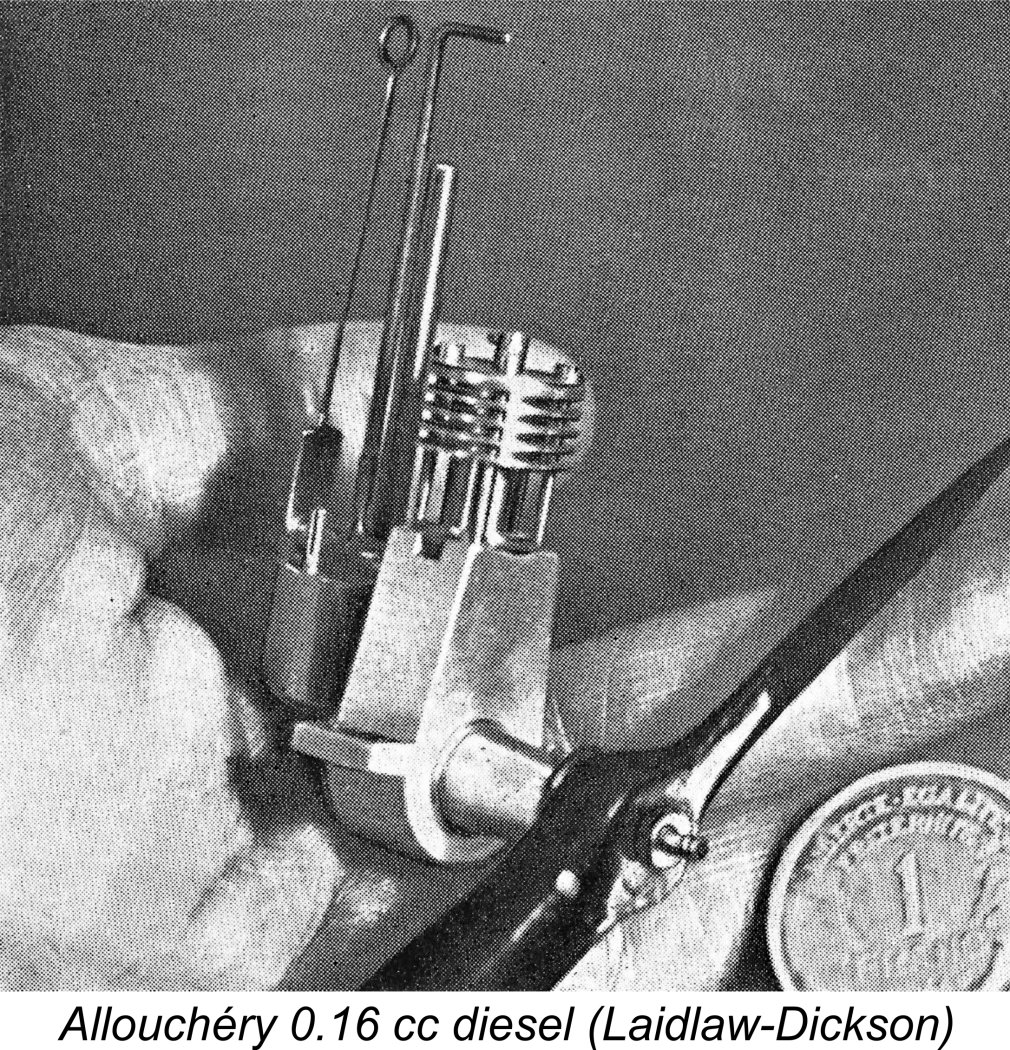

Mention should be made here of the frequently-noted 0.16 cc Allouchéry Éclair model which was touted as the world’s smallest-displacement functional model engine at the time. In reality, as of late 1946 that honour almost certainly belonged to the This tiny powerplant was never one of Allouchéry’s commercially-offered models, being individually constructed in miniscule numbers as a non-commercial “manufacturer’s trade show statement”. It was demonstrated at trade shows to attract attention to the marque, but only a very few examples were ever made as required for demonstration purposes and perhaps as keepsakes for friends. Good luck trying to find one today!! Sadly, from such a promising start Prosper Allouchéry’s designs failed to keep pace with the rapidly evolving model engine development trends of the day. As a result, from the early 1950’s onwards the brand declined as its offerings became ever more outdated. This eventually prompted an almost complete renewal of the range during the years 1954/1955.

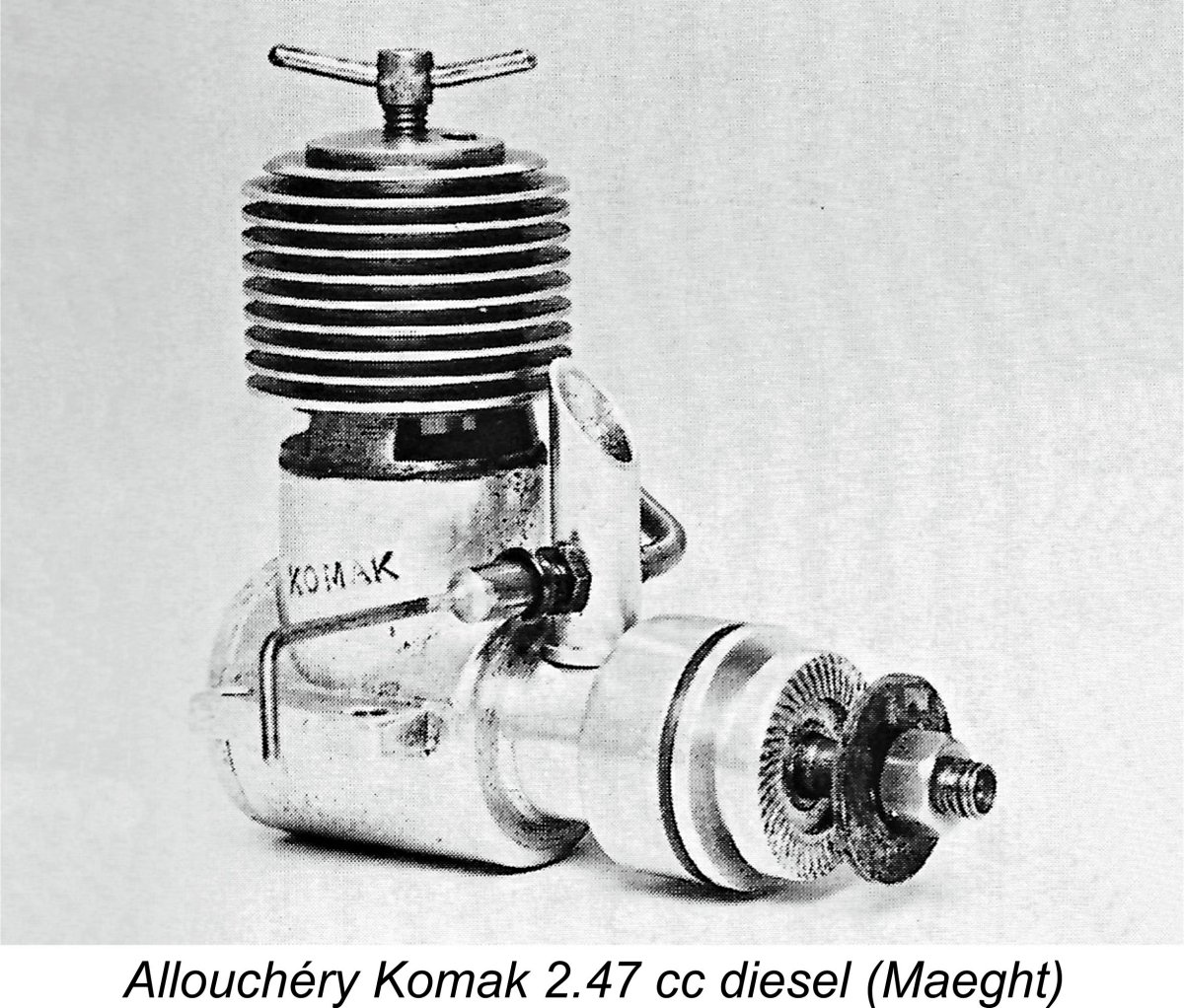

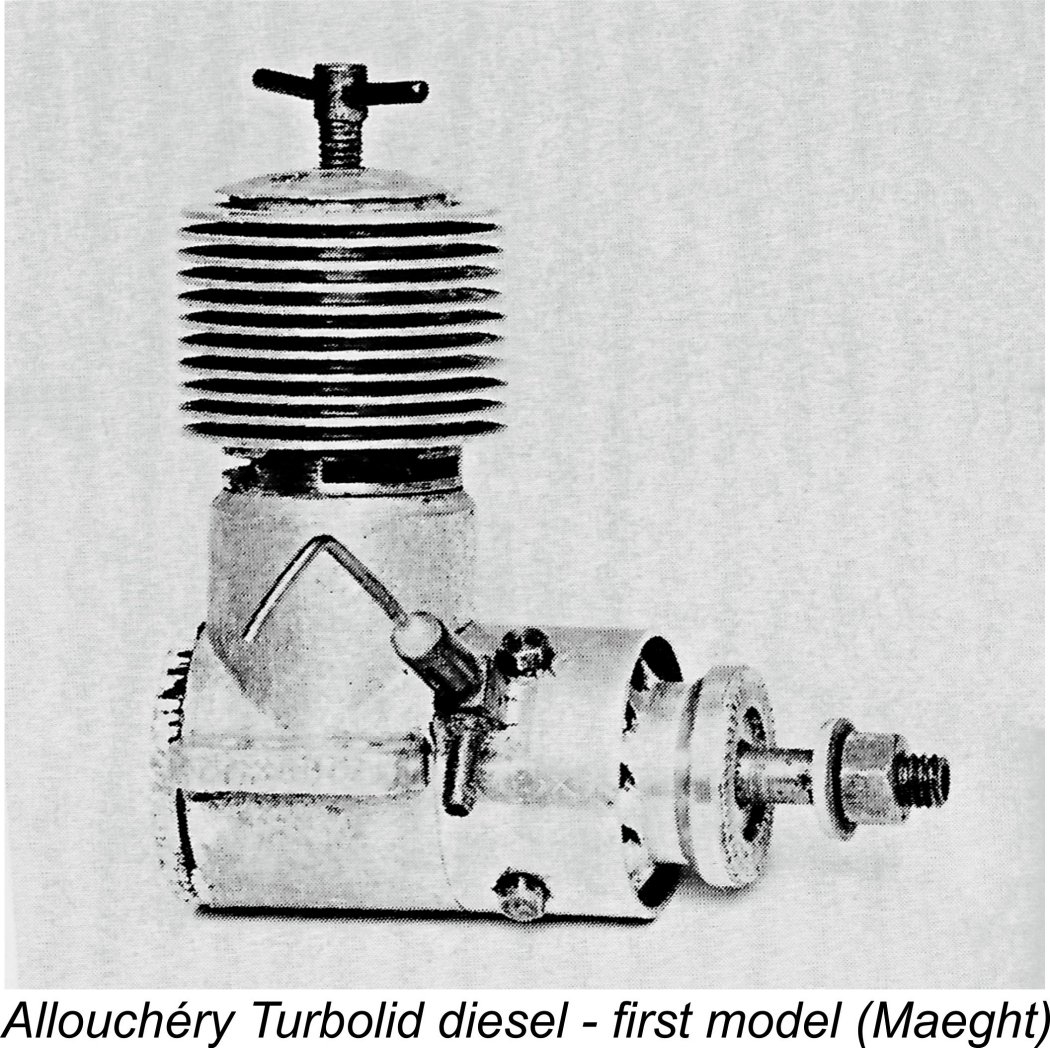

However, Prosper Allouchéry didn’t stop there! He also devised a fascinating turbocharged version of the 2.5 cc Komak called the Turbolid model. This used a prop driver having a set of fan blades at its rear end. These packed pressurized air into an annular space around the crankshaft, from which the FRV intake was supplied. For all its ingenuity, it seems doubtful that this arrangement conferred much in the way of a performance boost.

Noting this state of affairs and in the face of significant foreign competition, Prosper Allouchéry's previously-mentioned brother Numa and Numa's son Serge (Prosper's nephew) both felt that a market niche still existed. It’s abundantly clear that both Numa and Serge Allouchéry shared Prosper's passion for model engines. Indeed, they had both designed and constructed several engines of their own. In 1965 they decided to revive the defunct family business, doing so from a different location at 19 Rue Maison-Rouge in the nearby but quite distinct eastern Paris suburb of Fontenay-sous-Bois. Their first step was to update the now-iconic 1.25 cc diesel. The former bolt-on cylinder head now became spherical and was threaded onto the cylinder. A marine version of t Having got these updated models off the ground, the revived company continued its development program with an updated entry in the 2.5 cc class. This was available in both Sport/Stunt (Super Sport) and R/C (Super Télé) versions. It was also offered with a crankshaft-driven turbocharger setup derived from the original Turbolid model of 1955. The Super Télé variant was presented in the December 1965 issue (no. 320) of M.R.A. magazine. The article stated that production was carried out in very small batches on an artisan basis, with very high standards of quality being maintained. The writer took special note of the impeccable finish. Of course, there was a flip side to this very positive assessment. Engines made in this way cannot be offered cheaply if the makers are to survive economically with a fair monetary return on their time. Although I haven’t found any price quotations, the engines were certainly not cheap, especially for units that had not yet proved themselves. In the face of well-established and sometimes renowned competition, it was difficult to convince dealers to stock the range, even one bearing such a famous name in French modelling circles. For this reason, the majority of sales continued to be direct from the manufacturer to the purchaser. Even so, development was not abandoned, and the range continued to expand. The Allouchéry 5 cc Racing Engine - a False Start? By now the attentive reader will doubtless be asking the question: "Did he forget something? When is he going to get around to his supposed main subject, the Allouchéry 5 cc racing engine?" Fear not, dear reader - that time has come! The reason for my failure to so much as mention this model up to this point in the article is the fact that time and circumstance have combined to throw a great deal of confusion into the elucidation of this engine's time and place in the Allouchéry range. To attempt to unravel the facts, we now have to step back to 1948 to pick up the threads. As of 1948 control line flying was becoming The strong competition which soon developed between modellers in that category naturally stimulated a parallel competition among engine manufacturers. A race for horsepower soon developed. In early 1949, having just introduced his very powerful 10 cc Micron 60 racing model, André Gladieux announced that he was working on a similar design of 5 cc displacement. This duly appeared later in 1949. For his part, Météore designer Jules Maraget announced in advertisements featured in M.R.A. magazine that he was also developing a 5 cc ball-race competition model, which was also to make its debut in 1949. Word also leaked out that JIDE designer Jacques Durand was working on a 10 cc racing model, which eventually reached the market in 1950 under the Vega trade-name.

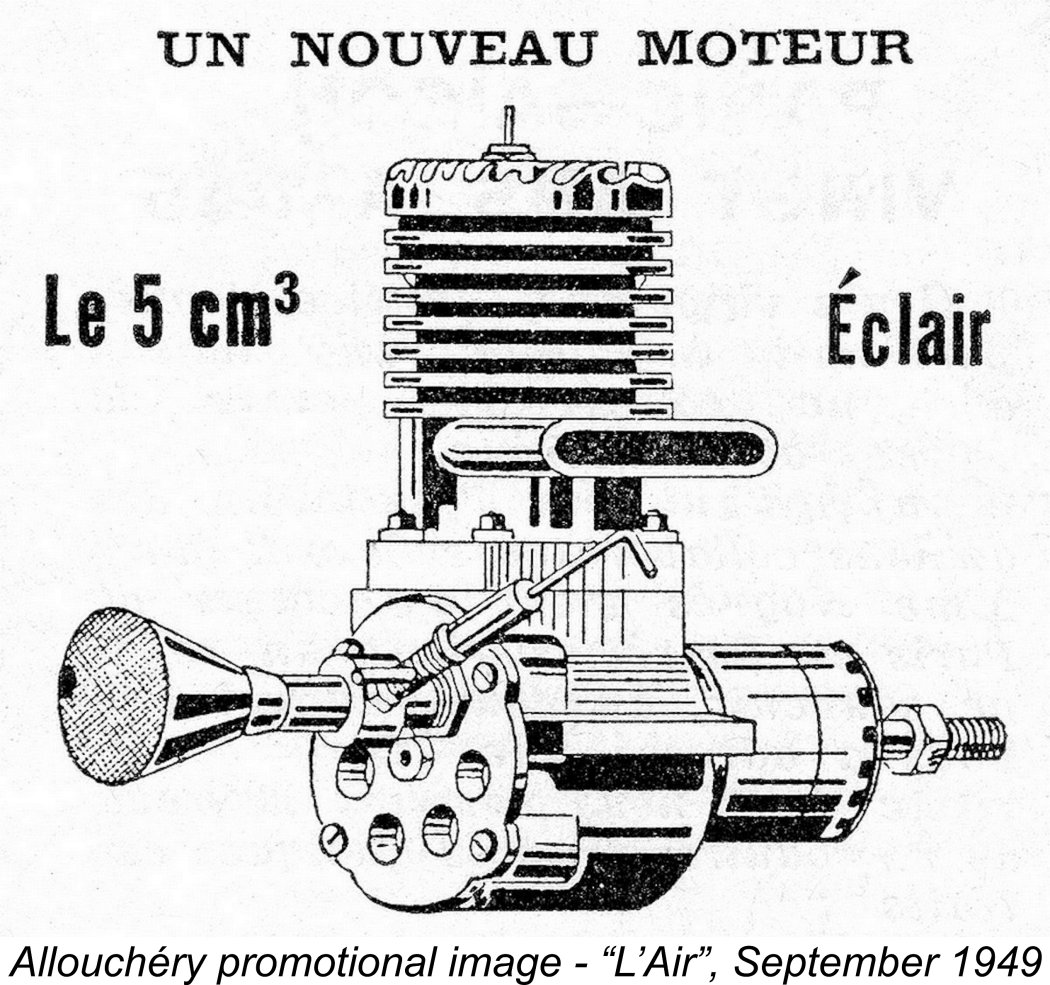

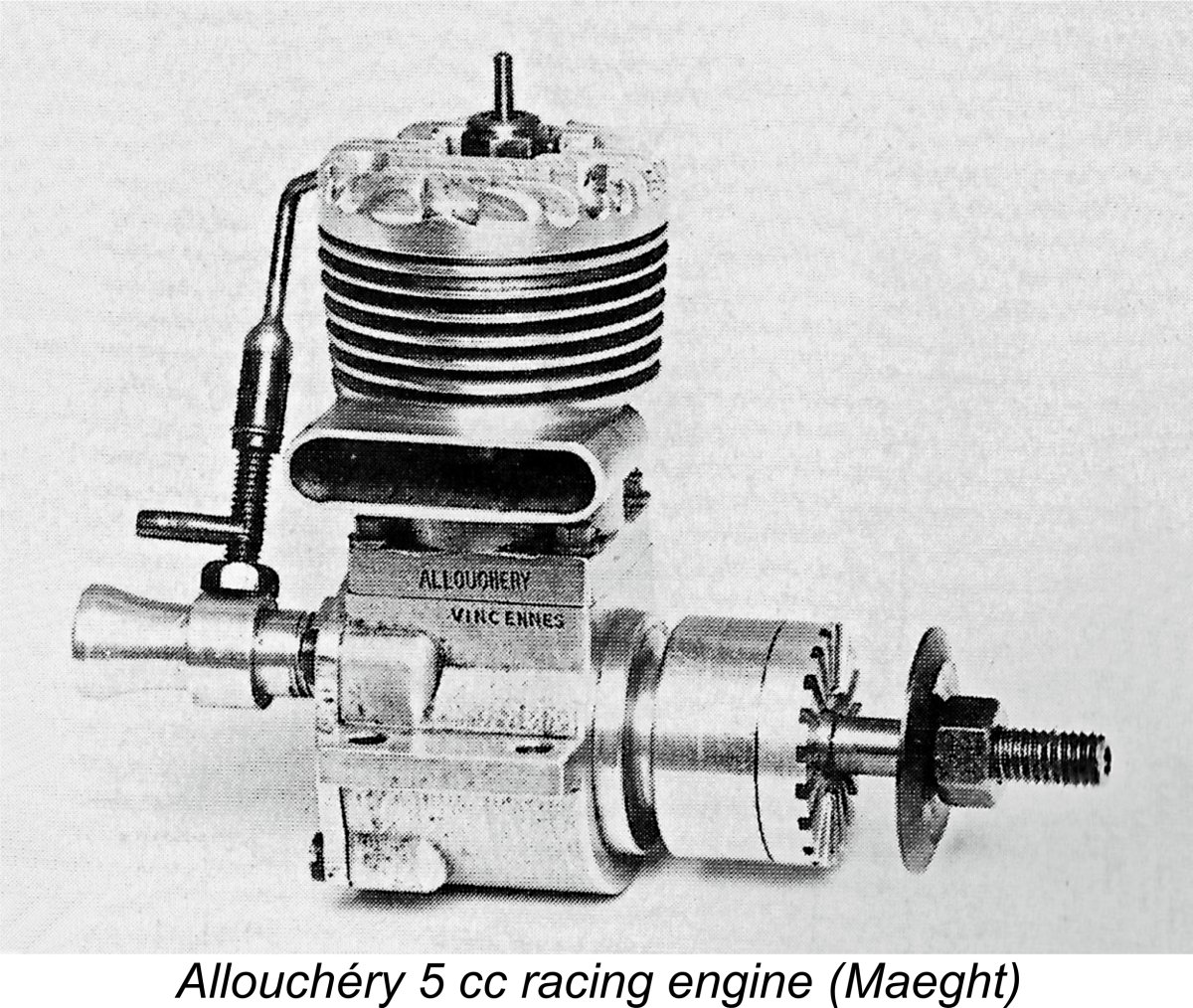

It's highly doubtful that this model ever reached the market in commercial numbers - certainly, it made no further advertising or media appearances at that time. A few examples were apparently seen here and there, but these were almost certainly prototype examples passed out to selected fliers for evaluation in the field. If an Allouchéry 5 cc racing model had been released commercially in late 1949, it would have been in direct competition with the ultra-powerful Micron 29 (0.50 BHP at 14,000 rpm and 8,700 francs) and the Météore 5 cc racing model (8,500 francs), the latter model only being available in very limited numbers. Since the Allouchéry model was never catalogued, we don't have any information regarding its selling price. However, it would presumably have been in the same ballpark as those of the Micron and Météore given their very similar specifications. As matters turned out, the modelling world had to wait until 1966 for the appearance of the first documentary evidence for the actual release of any 5 cc Allouchéry racing glow-plug model. This took the form of a short article in the April 1966 issue of “Air Modeles” magazine, which announced the appearance of a 5 cc Allouchéry racing glow-plug motor having disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction along with a twin ball-race crankshaft. This of course is none other than our subject engine, the development of which had first been announced way back in September 1949! As events were to prove, it was the only glow-plug model ever to be associated with the Allouchéry name. This article also ended up being its second and last appearance in the modelling media apart from its far later inclusion in Adrien Maeght's book.

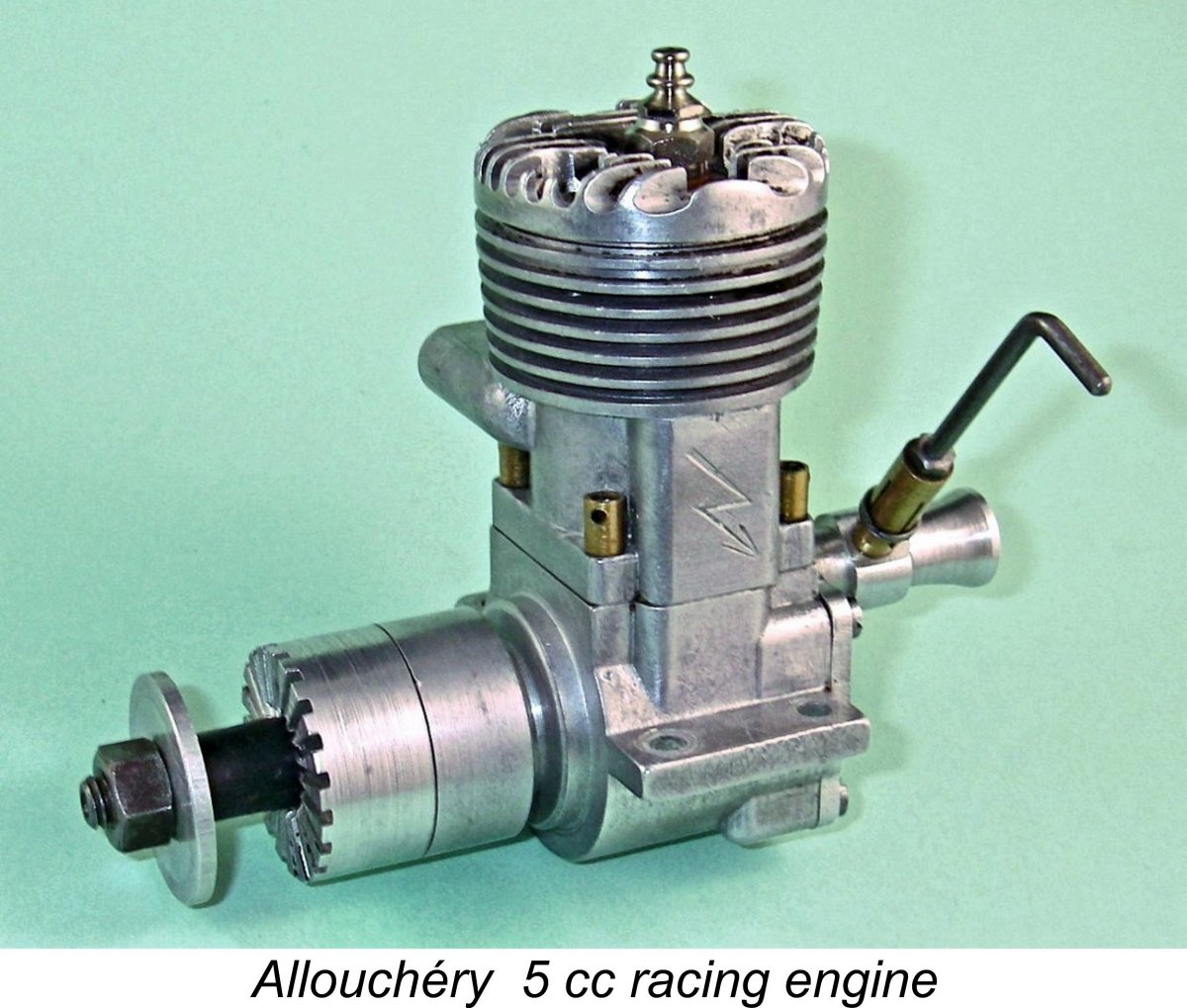

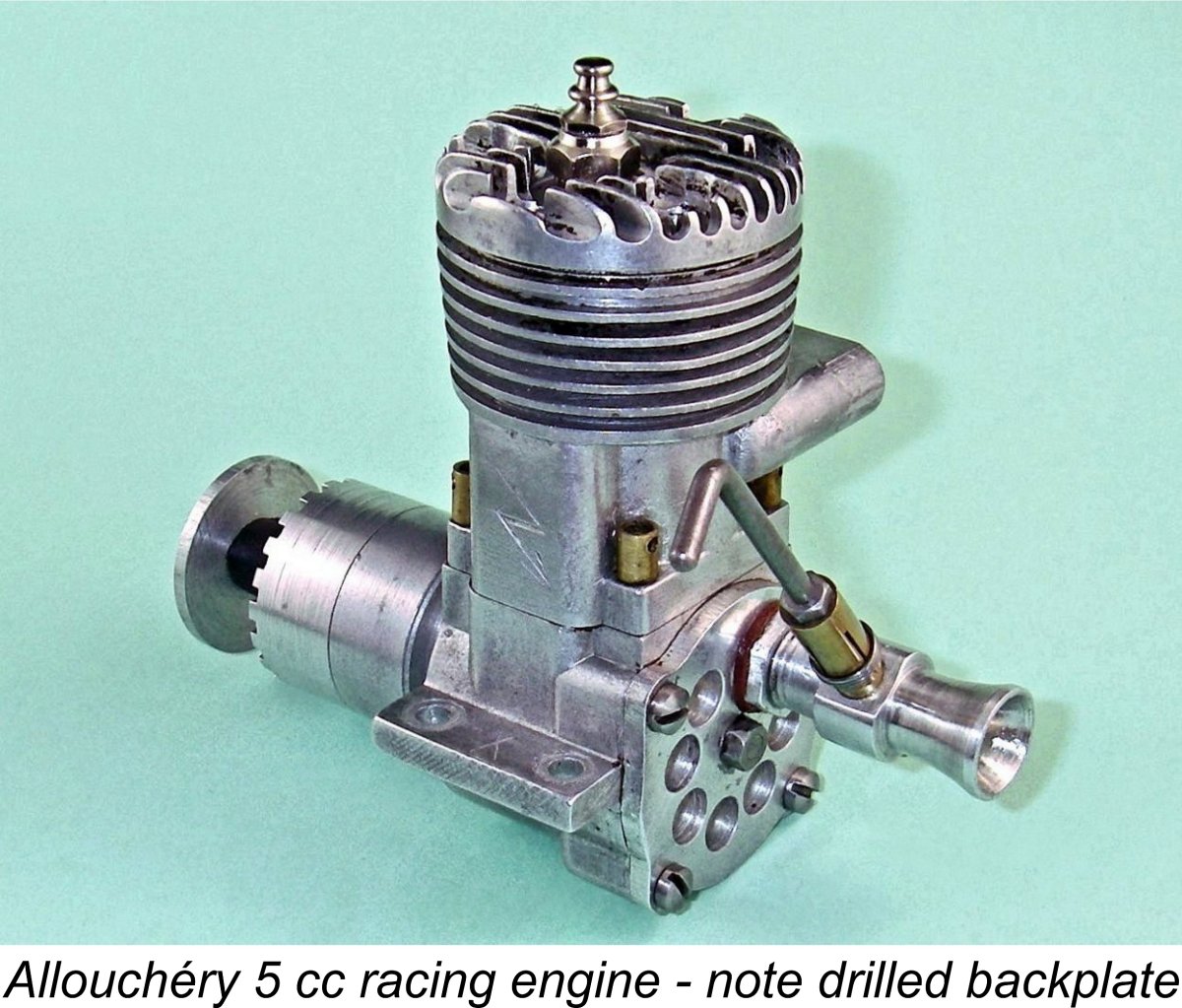

Images of both versions of this engine appear in Adrien Maeght’s previously-cited book, with a date of 1966 attached to each. This is consistent with the date of the article in “Air Modeles” magazine in which the engine was announced. That date has been assigned to the Allouchéry 5 cc racing engine ever since. So where's the dating problem here?!? For me, the event which began to throw some serious doubt on the 1966 date was my extremely fortuitous acquisition and examination of a superb example of this seemingly mega-rare engine. This was an unexpected treat for me personally given my very strong interest in classic racing engines. This beautifully-made unit would grace the collection of anyone interested in the classic model racing engines of the 1950’s and 1960’s. However, this happy situation immediately brought me up short when faced with that 1966 date. For me, the engine itself forcefully reopened the question - exactly when was it actually designed and produced? When I first set out to write this article after examining the engine, I was not aware of the September 1949 "L'Air" reference. Even so, despite the mutually consistent references in the “Air Modeles” article and in Maeght’s book, I simply could not reconcile the design of this engine with a 1966 date! Allow me to try to explain why………… The Dating Issue I’ll start right out by saying that in every respect, the construction of this engine clearly reflects the state of model racing engine design as of the late 1940's rather than 1966. It incorporates such “early classic” features as cross-flow loop scavenging, a ringed aluminium baffle piston, a plug which is offset to The "last man standing" using anything approaching such a mix of attributes was ETA in England with their 29 Mk. VIc model, which had a far better-developed bypass/transfer system as well as a high compression ratio along with a non-metallic disc valve and a surface-jet carburettor feeding a big-bore intake. Even that excellent model (which originated way back in 1949, remember) was approaching the point of being phased out as of 1966. The other piece of evidence which initially created doubt in my mind regarding the date is the fact that the engine is clearly stamped as having been made by Allouchéry in Vicennes. As stated earlier, the manufacture of Allouchéry engines at that location had ended as of 1960. When the range was revived in 1965, the workshop in which the engines were made had been relocated to an address in Fontenay-sous-Bois. Hence at first sight the engine's identification markings are seemingly inconsistent with a 1966 date. However, further research reveals that all of the engines made at Fontenay-sous-Bois continued to be marked with Vicennes as their place of origin. Presumably this was a token of respect for the legacy of company founder Prosper Allouchéry. Whatever the reason, no dating conclusions can legitimately be drawn from this designation. Even so, it was frankly impossible for me to accept the notion that Numa and Serge Allouchéry would have designed and produced this engine from scratch in 1965/66. Apart from the required design work, this would have involved the creation of the necessary dies and tooling - a major undertaking for a small artisan operation. Would the two revivalists really have gone to this amount of trouble to produce a tiny handful of examples of such a woefully outdated design by 1966 standards? I very much doubted it! On the other hand, the assembly of a few examples from components already on hand to take advantage of the retro and collector markets would make complete sense.

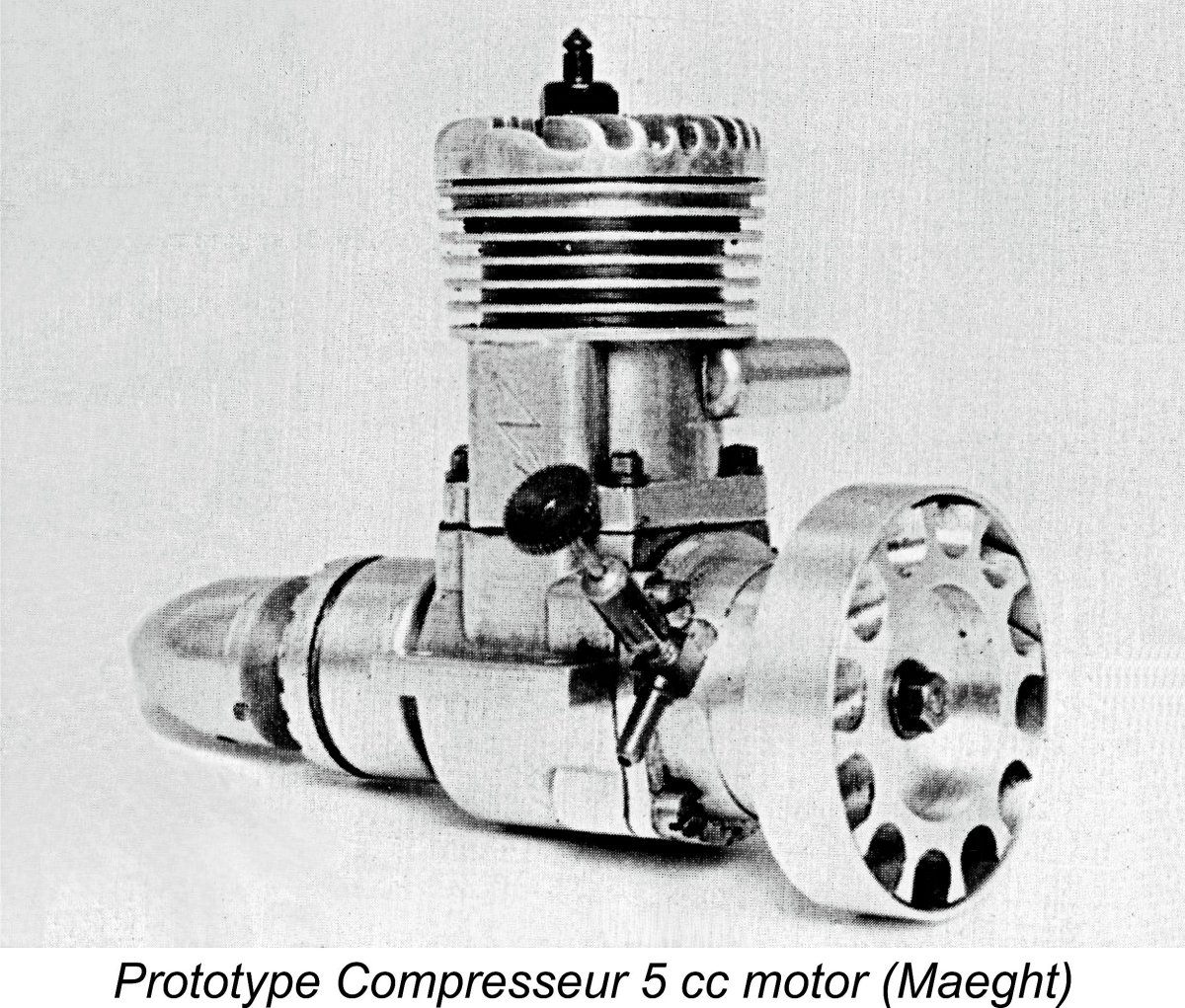

It now appears certain that the design and initial realization of this engine actually date back to 1949 and that it is in fact the very engine on which Prosper Allouchéry was said to have been working at that time. Its key features are uniformly consistent with that date, also matching the September 1949 illustration published in "L'Air" magazine in almost every respect. In my view, the most probable scenario is that Prosper Allouchéry commenced the behind-the-scenes development of this engine in 1948 or 1949, getting as far as creating the required dies and making a sufficient batch of the key components to assemble a handful of test prototypes by mid 1949. It's likely that the performance of the first prototypes fell short of the level required to encourage further development, putting a premature halt to the project. In particular, the engine may have under-performed by comparison with its Micron and Météore competitors. We'll be testing that possibility later. Quite apart from any performance issues, the market appearance of both the Micron and Météore 5 cc racing models in 1949 may have created a not unreasonable perception in Allouchéry's mind that the French 5 cc racing engine market was in danger of becoming saturated. He was thus looking at a design requiring further development which would have been facing very stiff competition in an over-supplied market. Whatever the reason(s), Allouchéry evidently set the rather under-developed 5 cc glow-plug racing design aside to focus on his diesel models, eventually resulting in the previously-mentioned 1954/55 upgrade of those models. He may have intended to come back to the glow-plug model later. However, by the time he was ready to do so, further development by other manufacturers had passed him by, to the point that he would have had to start all over from scratch to come up with a competitive 5 cc racing design. Given the fact that the Allouchéry model engine venture was still struggling in the marketplace, this would have been seen as economically unjustifiable. The abandonment of the project would have left the dies and completed components (and perhaps a few assembled prototypes) available to Prosper Allouchéry's successors. This makes it appear entirely possible that when the manufacture of certain models was resumed in 1965 by those successors, a decision was soon taken to assemble a small batch of these engines using 16 year old components already on hand as a basis. If this scenario is correct, the number of engines completed can probably be counted on the fingers of both hands. All of this having been said, my friend and colleague Michel Rosanoff has suggested that the previously-mentioned turbocharged “Compresseur” model may indeed have been created in 1966. Michel believes that Serge Allouchéry may have constructed this engine to special order for the well-known model engine enthusiast Dr. Marcel Antonetti. Even so, it seems to me to be very likely that the components of the engine on which this model was based, or perhaps even the engine itself, had been produced far earlier. The best way to support my case that the design and original production stages of this engine date from considerably earlier than 1966 was clearly to go through a detailed description of its chief design features. Here goes! Description

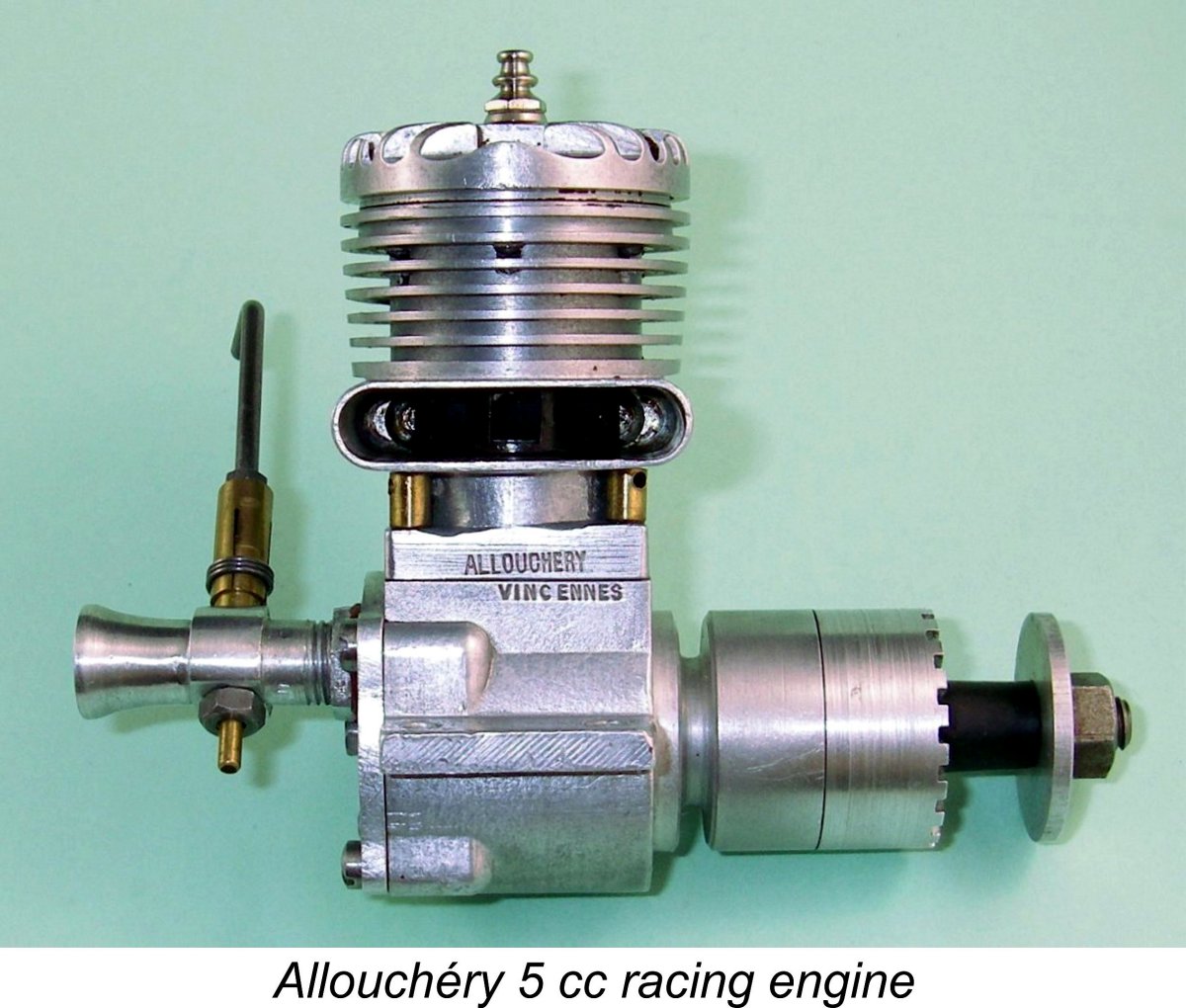

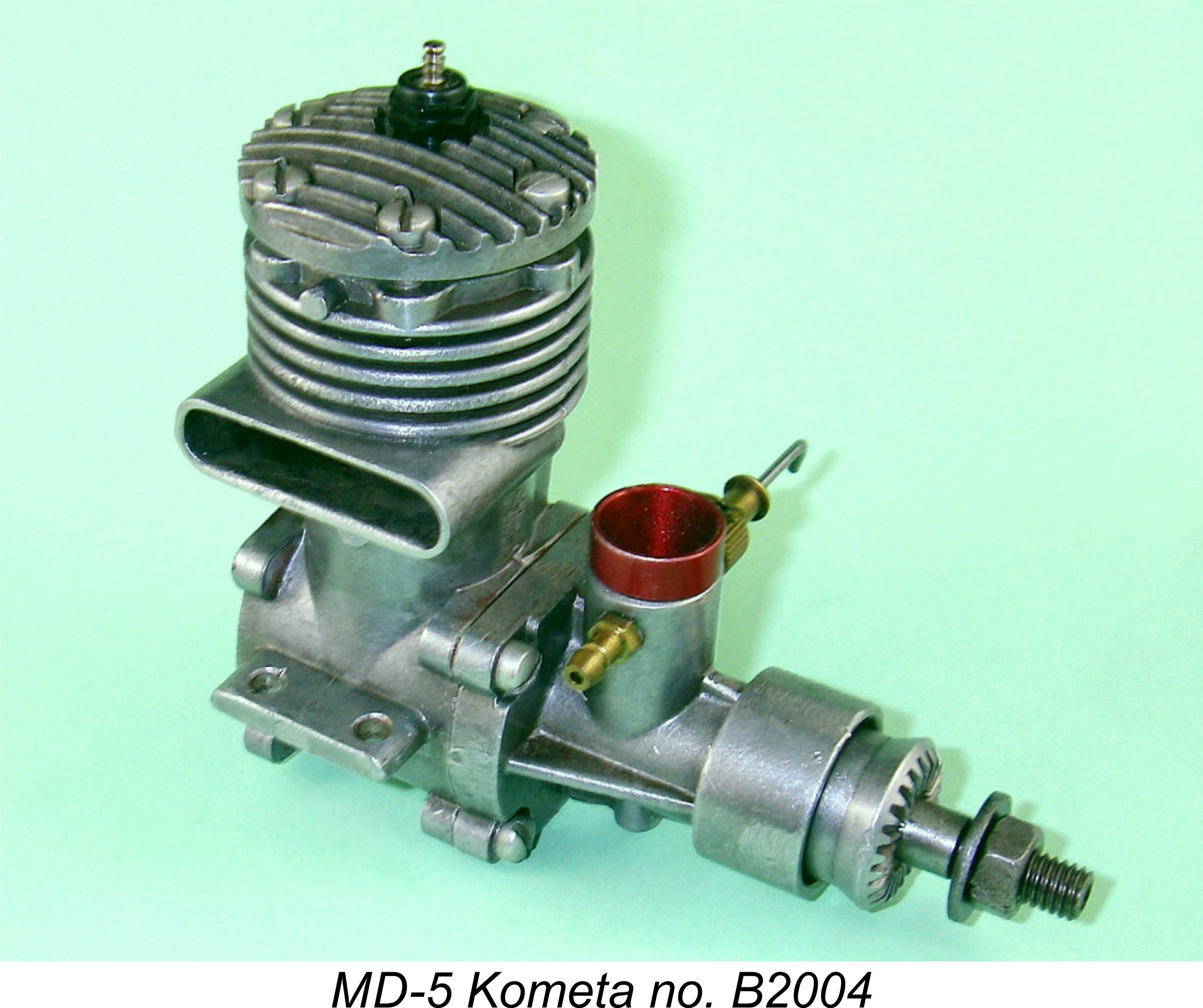

Beginning as usual with the tale of the tape, bore and stroke of the Allouchéry are the Continental standard figures of 19.0 mm (0.779 in.) and 17.0 mm (0.591 in.) respectively for a calculated displacement of 4.82 cc (0.294 cuin.). These are pretty much universal dimensions for 5 cc European racing engines of the early to mid 1950's. The motor weighs in at a not-unreasonable 226 gm (7.97 ounces). But now it gets weird! The above bore and stroke dimensions are in direct conflict with those given in Maeght’s book. The 17 mm stroke cited above for my example has been accurately and repeatedly measured through the plug installation hole, hence undoubtedly being correct. However, Maeght gives a stroke of 19.8 mm in his book, which would make this a long-stroke engine. The bore of my engine has been checked as closely as possible without dismantling it by repeated measurements taken through the exhaust. While these measurements are admittedly somewhat imprecise, a lengthy series of bore dimensions successively obtained in this way averages right around the 19 mm figure - certainly nowhere near the 15 mm given by Maeght. Indeed, Maeght gives a (probably accurate) bore of 19.0 mm for the prototype turbocharged “Compresseur” version of the same engine (see above) while repeating the clearly incorrect 19.8 mm figure for the stroke.

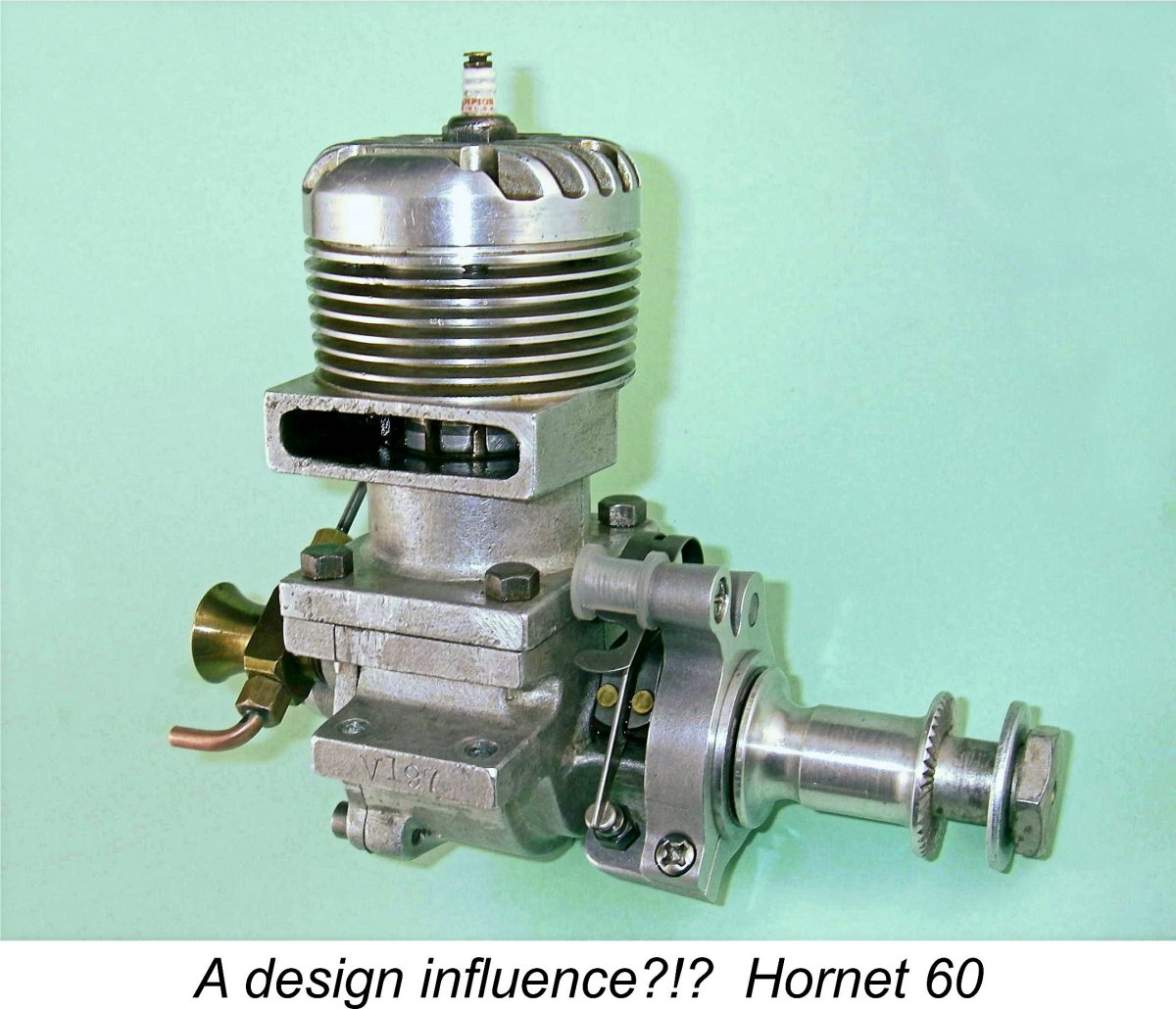

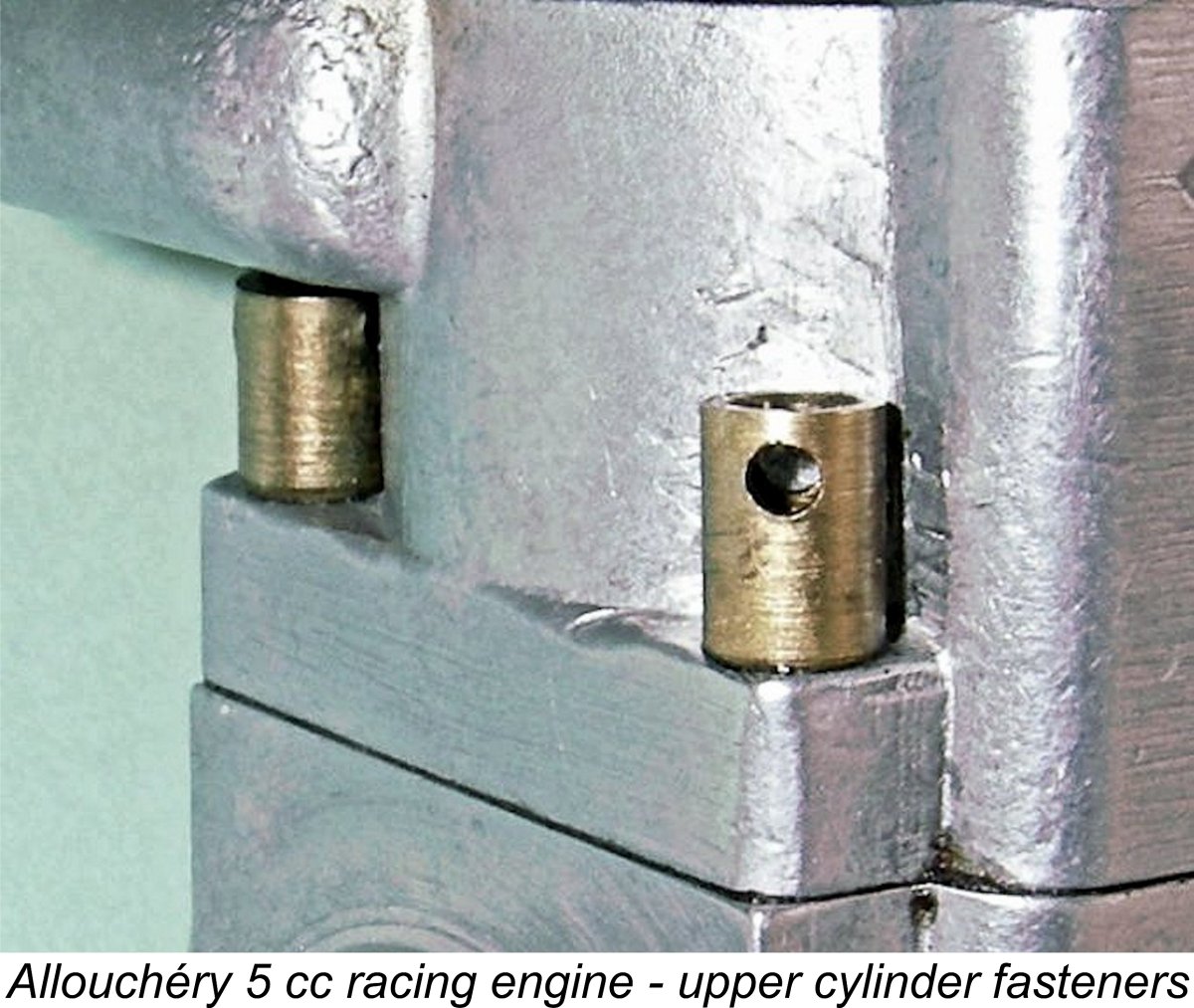

It’s abundantly clear that Maeght's reported figures for the 5 cc glow-plug models were not checked against an actual example, nor were the resulting displacements calculated - an incompatible figure of 5 cc was cited in both instances. I’m happy to stick with my confirmed 19.0 x 17.0 figures and a 4.82 cc displacement - after all, these dimensions were widely employed by other European racing engine manufacturers of the period such as Micron, Météore, Super Tigre, Typhoon and others. The Allouchéry follows the lead of the Hornet 60 in using a separate upper cylinder casting which incorporates the cooling fins, exhaust stack and bypass passage in a single component. This well-executed gravity die-casting is secured to the lower crankcase by four internally-threaded brass tubes which engage with studs threaded into the upper crankcase and protruding The reason for the use of these unusual fasteners is plain enough - there’s insufficient lateral space and vertical access to permit the use of conventional nuts. Even so, this undeniably tidy arrangement would make dismantling and re-assembling the engine a bit of a pain. Apart from checking that all four fasteners were tight, I was happy to forgo the pleasure! Beginning at the top, the cylinder head is a clean gravity die-casting which is secured by 6 slot-head screws. The cooling fins are cast in unit with the component rather than being machined. Since I elected not to dismantle the engine beyond the removal of the backplate, I have no information regarding the configuration of the combustion chamber. All that I can report is that the volumetrically measured compression ratio is a relatively modest 7:1. As seen in an earlier image, the vertically oriented ¼-32 long reach glowplug is considerably offset towards the transfer side of the cylinder, being actually located directly above the baffle. This is a definite throw-back As stated earlier, the upper cylinder is a cleanly-formed gravity die-casting which includes the cooling fins, bypass passage, exhaust stack and bottom location flange in a single unit. The cylinder cooling fins are machined into the casting rather than being cast. The bypass is unusually small by racing engine standards, even by those of the late 1940's. The cylinder liner appears to be of conventional drop-in form. It is provided with conventionally-bridged transfer and exhaust ports. There are six exhaust apertures, but only three transfer openings. The latter feature is pretty much dictated by the very narrow bypass passage. This arrangement follows the pattern of the early Hornet 60 models - the use of four or more transfer openings became the norm quite early on. Again, this feature is strongly suggestive of a date far earlier than 1966. The piston is a nicely-produced casting in light alloy. It is equipped with two well-fitted piston rings which provide an excellent compression seal. A transverse wedge-shaped baffle is incorporated into the crown. Again, this piston design is a clear indication of a date considerably earlier than 1966 - by that year, no-one was introducing new racing engines based on this technology. The piston drives the crankshaft through a nicely machined alloy conrod.

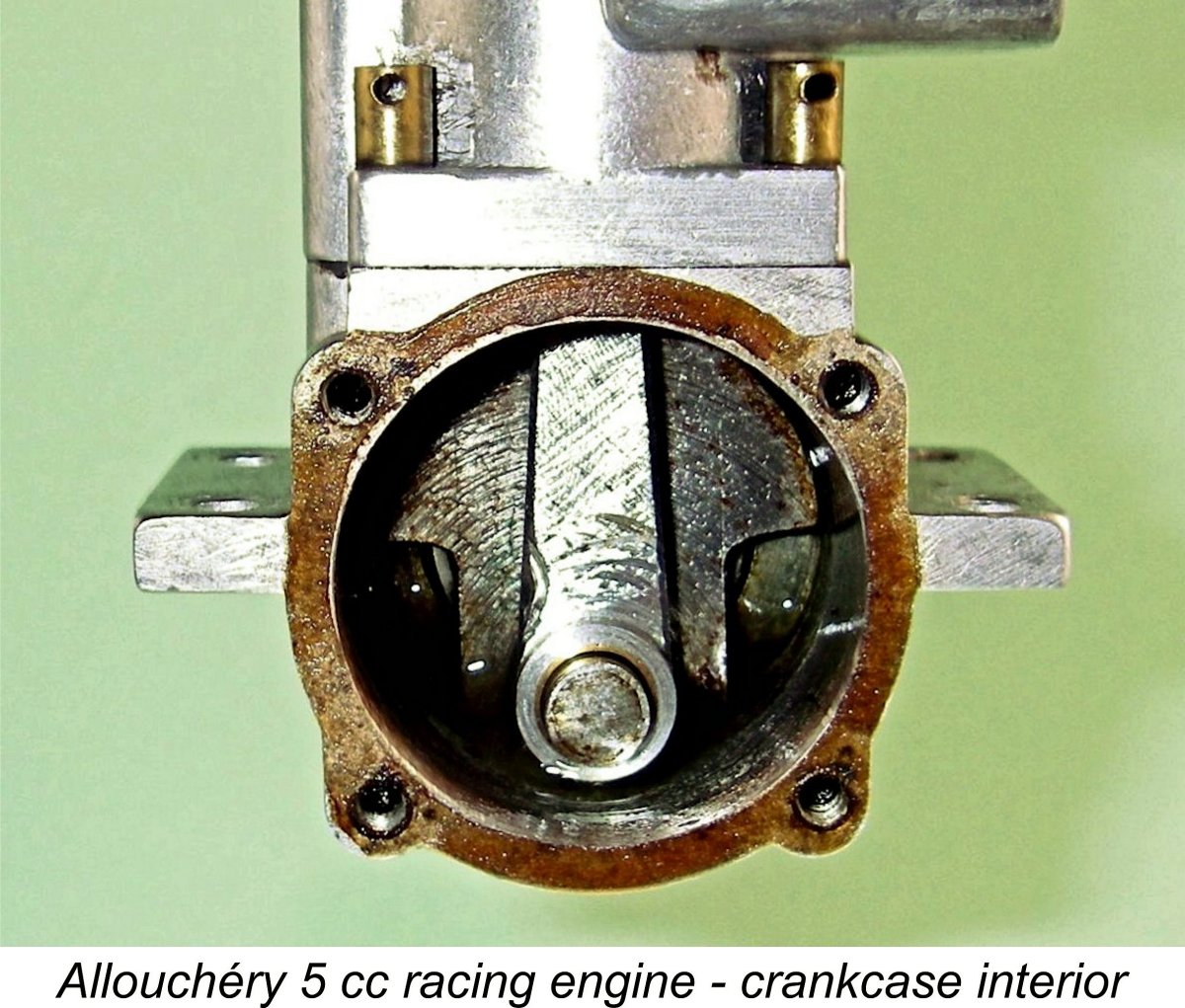

The main crankcase is once again a well-produced gravity die-casting. It incorporates the main bearing housing in unit. The crankshaft has a heavily counterbalanced crankweb very reminiscent of the style featured in certain E.D. models. It runs in two ball bearings of a size which cannot be determined given my unwillingness to dismantle the engine down to the shaft. The bearings are notably free-running, seemingly indicative of their being high-quality components. At the front, the rather massive prop driver is beautifully matched to the front bearing housing. The driving face is rather unusually provided with milled radial grooves rather than the more usual knurling for improved grip. It must be said that the diameter of the prop driver is considerably greater than that of most racing engines - yet another indication of an early date. A conventional nut and washer are used to secure the prop.

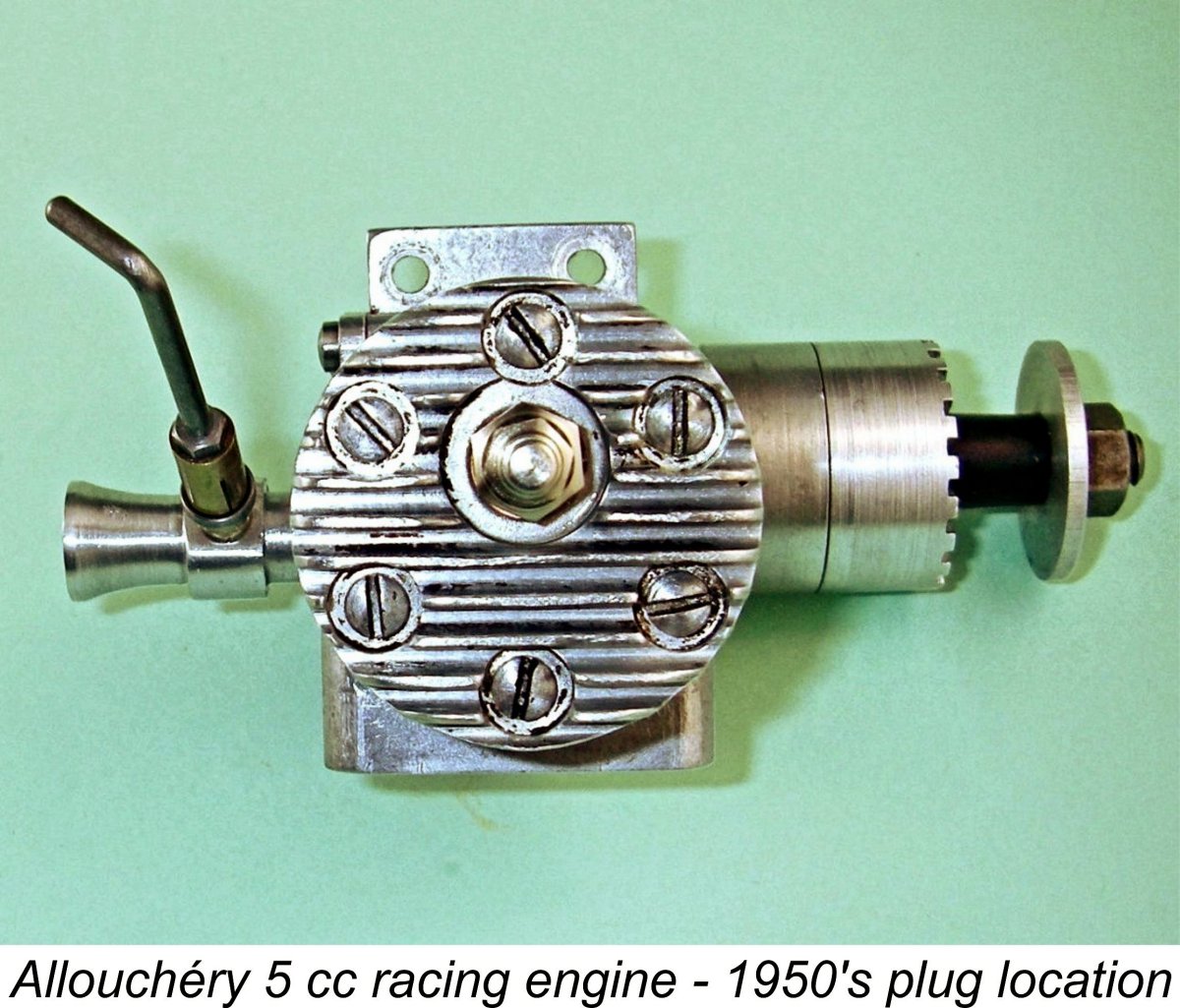

Induction timing is fairly conventional by 1950’s standards. The port opens at around 45 degrees after Bottom Dead Centre (ABDC) and closes at 40 degrees ATDC for a total induction period of 175 degrees. The intake venturi is a separate component which threads into the backplate and is secured by a lock-nut. A quality touch is the provision of a fibre gasket under the lock-nut to prevent any leakage. The needle valve assembly appears to be a standard Micron component, presumably obtained directly from Micron. Assuming that these engines were assembled in 1966 from previously-manufactured components, it appears that no needle valve assemblies were available, leading to the use of an available proprietary component from a local manufacturer to simplify production.

As mentioned earlier, the intake venturi is of very modest dimensions even by late 1940’s racing engine standards. The bore at the needle valve location is 6.5 mm, while the spraybar diameter of my example is 3.0 mm. According to Maris Dislers’ extremely useful Choke Area Calculator, this provides a rather restrictive choke area of only 14.399 mm2 and a minimum stable operating speed on suction feed of around 6,200 rpm. We would normally expect a glow-plug engine of this specification to be operated at a far higher speed than this, suggesting that the choke area could undoubtedly have been increased quite considerably with some advantage in performance terms. However, the stated dimensions are about as large as could be accommodated within the rather modest external diameter of the intake tube actually used. All in all, I simply couldn't see this very conservatively-arranged engine as having been designed in 1966. All of the main features described above point to a far earlier design date, probably around 1949/50 or thereabouts. The September 1949 reference in "L'Air" magazine seems to me to confirm this dating beyond any possible doubt. In terms of the number of examples produced, there’s no guidance to be had from serial numbers, since the engines evidently did not bear such numbers. All that can be said with some confidence is that the number completed seems to have been extremely small. The Allouchéry 5 cc “Vitesse” Racing Engine on Test

My example has clearly seen a fair bit of running time, including having been mounted in at least one model. It is therefore well broken in, requiring no preliminary running apart from a shake-down run or two. It remains in first-class mechanical condition, hence being all set to deliver a fully representative performance on the test bench. I wasn’t expecting anything approaching a really stellar performance from this unit, even by late 1940’s standards. Looking at the very narrow bypass with its three transfer apertures as well as the extremely small effective choke area, I was expecting a peak output in the 13,000 - 14,000 rpm range at best. This being the case, I decided to begin the test using an APC 9x5 prop. I also elected to go with a fuel containing 15% nitro and 28% castor oil given the engine’s low compression ratio and extreme rarity.

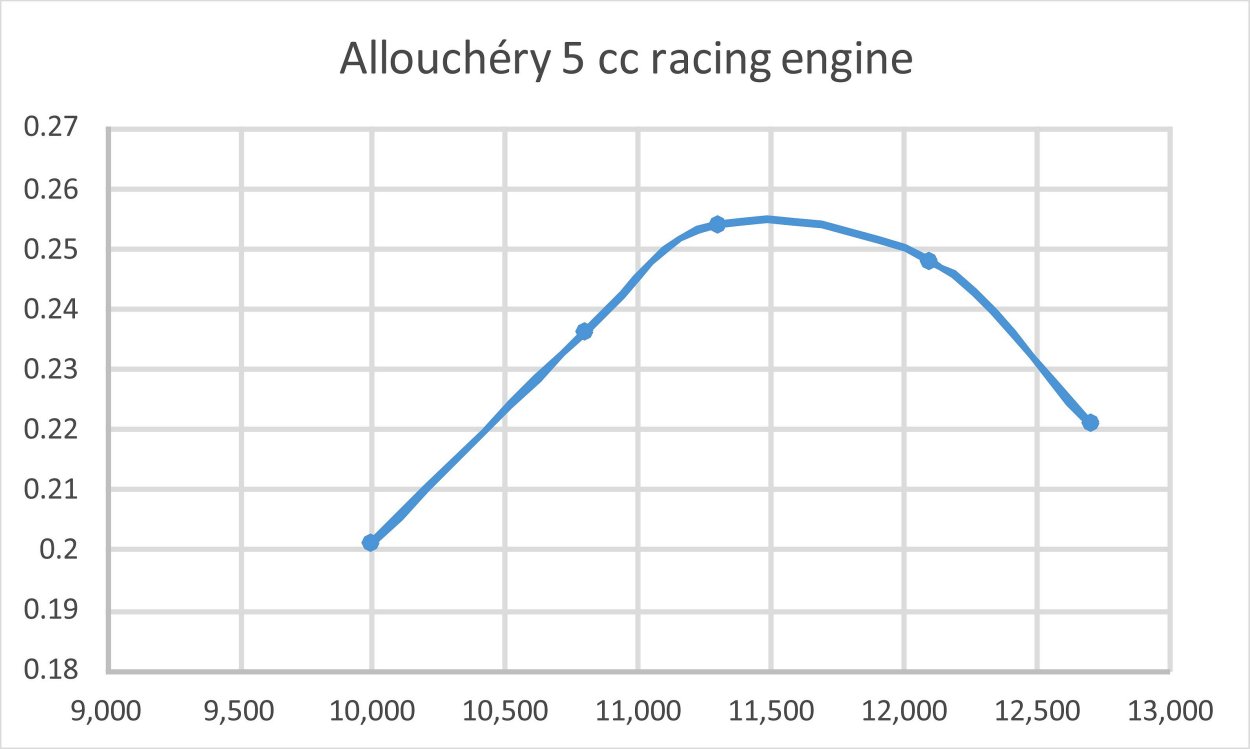

And I wasn't disappointed! After opening the needle some four turns (a pure guess!) and administering a healthy exhaust prime, I lit the plug and flipped the prop. Presto - one instant one-flick start after who knows how many years in storage! The engine started extremely rich - it turned out that only a little over 1 turn of the needle was required for starting. The engine picked up on the fuel line right away and kept right on running quite happily, waiting for me to set the needle. In deference to the engine's long layoff, I let it run fast and rich for around 5 minutes, keeping it just slightly on the rich side of the four-stroke/two-stroke break. I then leaned it out briefly and then stopped it, allowing complete cooling before proceeding to the actual test stage. I had already determined that I would I have to say that this engine was an absolute pleasure to test. It wasn't in the least bit vicious, invariably starting first or second flick following a prime and responding very well indeed to the needle. It turned out that the needle setting for best running was a little on the sensitive side, but the optimal setting was quite well marked. The needle held its settings very securely, in keeping with my previous experience of Micron needle valve assemblies. The engine ran extremely smoothly with never a trace of a misfire when leaned out. It displayed no symptoms of mechanical distress at any time. So far, it all sounds pretty rosy, yes?!? Well, now things turn a little less positive! For all the engine's outstanding starting characteristics and smooth running qualities, it turned out that there simply wasn't much power being developed! The following data were recorded during the test:

Oh dear!! The data imply an output of only some 0.258 BHP @ 11,700 rpm. Even if we assume (as I am) that the design of this engine dates from 1949, that's a pretty marginal performance! I think that we may be seeing here why the engine never seems to have become widely distributed - Prosper Allouchéry must have realized pretty quickly that more development was required to bring the engine to a competitive state. In effect, the design stalled at the prototype stage. Even so, I have to say that there appears to me to be far more potential in the design as it stands than the performance that I measured. I've checked the engine thoroughly for leaks and mechanical issues, finding none. The performance that I measured is therefore not down to any problems with this particular example but to the design itself. To me, the most likely culprit here appears to be the induction system's very small effective choke area. I commented earlier on this design feature. The 14.399 mm2 effective choke area of the intake is about what we would normally expect to see with a high-performance 2.5 cc diesel intended for operation on suction. I have no doubt at all that opening up the intake to something like an 8 mm bore with a 2.5 mm dia. spraybar would unlock a considerably enhanced performance from this unit.

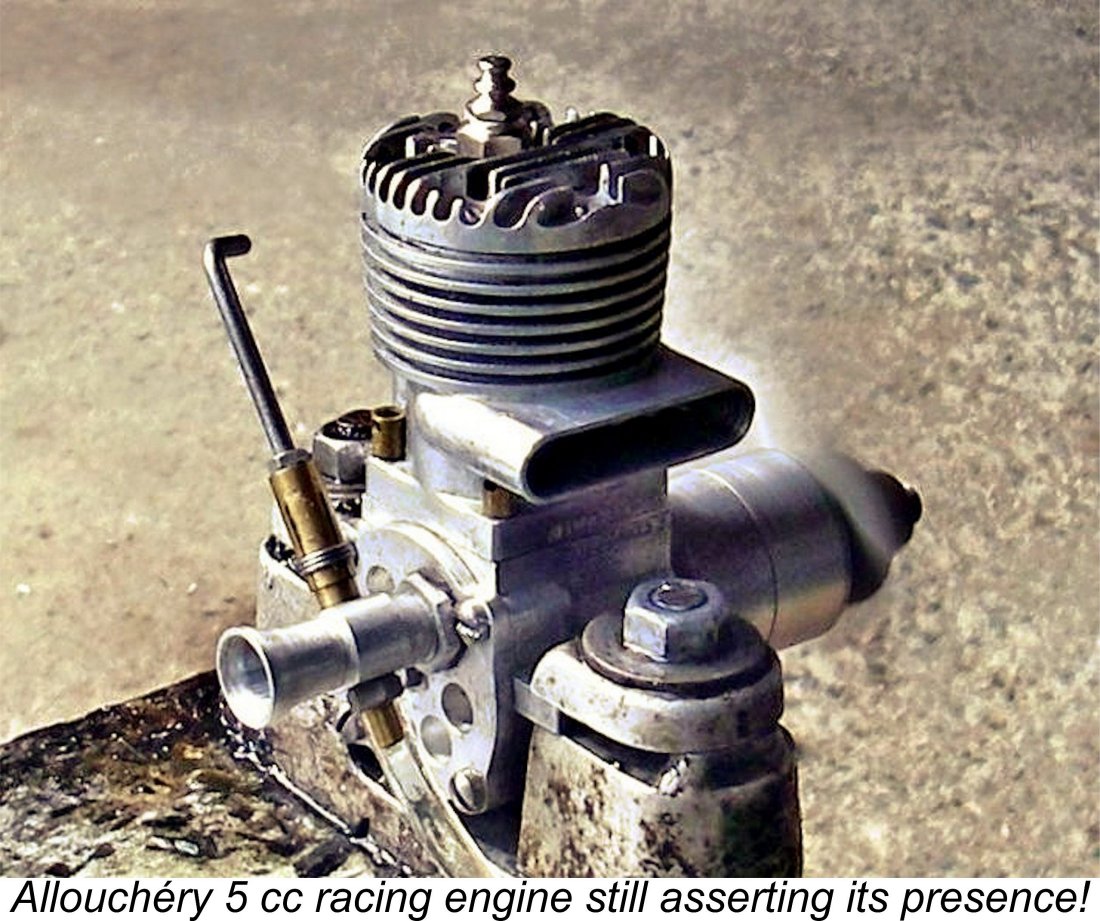

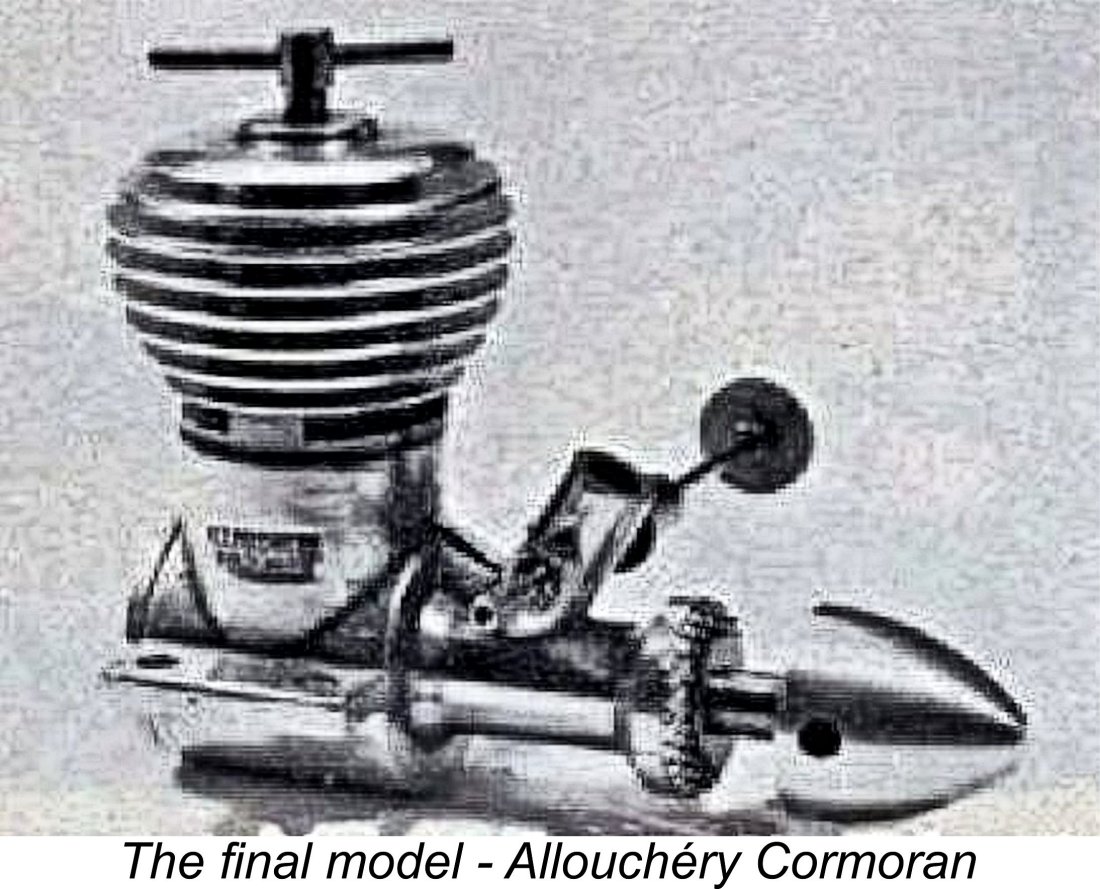

I'd be prepared to bet that fitting an 8 mm dia. venturi to the Allouchéry as it stands and loading up on the nitro would result in a very significant performance improvement. Even sticking with the present 3 mm dia. spraybar, the effective choke area would be increased to 26.84 mm2, an increase of some 86% over the standard area of 14.399 mm2. The minimum stable operating speed on suction fuel feed would be raised to 11,400 rpm, a far more appropriate figure for an engine of this type. The use of a single-jet needle valve as featured on the example illustrated by Maeght would also help very much by eliminating most of the spraybar. However, I have no plans to modify my engine - what would be the point? I think I've done enough to demonstrate that the Allouchéry 5 cc racing engine was a superbly-crafted unit having plenty of promise but being hamstrung by a totally inadequate intake choke area. Given further development, it could have been turned into quite a competitive engine for its time and place! Conclusion It’s abundantly clear that whatever the truth regarding its design and construction dating, the Allouchéry 5 cc “Vitesse” model was produced in very small numbers indeed. Its April 1966 "official" introduction was its one and only appearance in the contemporary modelling media. Moreover, it failed to contribute to the longer-term survival of the Allouchéry marque.

Sadly, things did not improve as 1967 drew on. During the summer, while the French modelling world was reverberating with joy over the second place taken by Pierre Marot at the fifth World Championship for R/C aerobatics held at Ajaccio, Corsica, the death knell sounded for the Allouchéry marque. The final advertisement appeared in the July 1967 issue of "M.R.A." magazine, after which the company quietly closed its doors after only two years of renewed activity. But not before leaving us with some superbly-made engines to attest to the abilities of the Allouchéry family! The 5 cc “Vitesse” glow-plug model is a most worthy representative of the skill of its makers. The fact that its origins remain somewhat shrouded in uncertainty actually adds to its appeal as far as I’m concerned! _________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published April 2022 |

||

| |

This article sees us return to France after quite a long absence to take a look at a little-known racing engine from that country. We’ll be examining the very rare Allouchéry 5 cc “Vitesse” (Speed) racing glow-plug motor, which bears the distinction of having been the only glow-plug design ever announced by the once-famous pioneering Allouchéry company of Paris.

This article sees us return to France after quite a long absence to take a look at a little-known racing engine from that country. We’ll be examining the very rare Allouchéry 5 cc “Vitesse” (Speed) racing glow-plug motor, which bears the distinction of having been the only glow-plug design ever announced by the once-famous pioneering Allouchéry company of Paris.

life in 1959 at the age of only 57 years. In 1944 he had gone to Switzerland to undergo a lengthy detoxification treatment, following which he had become an avid follower of aeromodelling and a staunch advocate of the Allouchéry model engine range. He was planning another trip to the USA, on which he intended to take along some Allouchéry engines plus a completed Allouchéry-powered model which had been built by the world record holder H. Varache. He believed that these would amaze the Americans!

life in 1959 at the age of only 57 years. In 1944 he had gone to Switzerland to undergo a lengthy detoxification treatment, following which he had become an avid follower of aeromodelling and a staunch advocate of the Allouchéry model engine range. He was planning another trip to the USA, on which he intended to take along some Allouchéry engines plus a completed Allouchéry-powered model which had been built by the world record holder H. Varache. He believed that these would amaze the Americans!

Of more direct relevance to our main subject, the 1949 rumour mill also circulated the story that Prosper Allouchéry was then working on his own 5 cc racing glowplug model. Confirmation of this came in the form of an illustrated announcement in the September 1949 issue of "L'Air" magazine (issue no. 631) of "un nouveau moteur" - the 5 cc Éclair model. The illustration proves unarguably that this was the Allouchéry 5 cc “Vitesse” (Speed) racing glow-plug motor which forms my main subject.

Of more direct relevance to our main subject, the 1949 rumour mill also circulated the story that Prosper Allouchéry was then working on his own 5 cc racing glowplug model. Confirmation of this came in the form of an illustrated announcement in the September 1949 issue of "L'Air" magazine (issue no. 631) of "un nouveau moteur" - the 5 cc Éclair model. The illustration proves unarguably that this was the Allouchéry 5 cc “Vitesse” (Speed) racing glow-plug motor which forms my main subject.

the transfer side, a relatively low compression ratio, a very small bypass passage with only 3 transfer openings in the cylinder wall, an aluminium alloy disc valve, a relatively small-diameter intake venturi and a spraybar carburettor system. All of these features were in common use as of 1949. By contrast, by 1966 NO-ONE was introducing new 5 cc racing glow-plug motors combining such an array of features.

the transfer side, a relatively low compression ratio, a very small bypass passage with only 3 transfer openings in the cylinder wall, an aluminium alloy disc valve, a relatively small-diameter intake venturi and a spraybar carburettor system. All of these features were in common use as of 1949. By contrast, by 1966 NO-ONE was introducing new 5 cc racing glow-plug motors combining such an array of features. When I first received the engine from its seller, my late good mate Tim Dannels, I included a request for enlightenment from knowledgeable readers in the Editorial which accompanied the October 2019 issue of this website. I was delighted to receive immediate responses from my valued friends and colleagues Ken Croft and Maris Dislers. Apart from drawing my attention to the information available on the previously-cited

When I first received the engine from its seller, my late good mate Tim Dannels, I included a request for enlightenment from knowledgeable readers in the Editorial which accompanied the October 2019 issue of this website. I was delighted to receive immediate responses from my valued friends and colleagues Ken Croft and Maris Dislers. Apart from drawing my attention to the information available on the previously-cited  The Allouchéry 5 cc “Vitesse” racing engine is a basically conventional early classic-era design featuring cross-flow loop scavenging, a twin-ringed light alloy baffle piston, a twin ball-race crankshaft and disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction. In every key respect it follows the classic racing engine design layout which had been established in America and elsewhere by the close of the 1940’s. If I had to pick a classic model racing engine which most closely suggested the design of the Allouchéry 5 cc model, I’d unhesitatingly choose the American

The Allouchéry 5 cc “Vitesse” racing engine is a basically conventional early classic-era design featuring cross-flow loop scavenging, a twin-ringed light alloy baffle piston, a twin ball-race crankshaft and disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction. In every key respect it follows the classic racing engine design layout which had been established in America and elsewhere by the close of the 1940’s. If I had to pick a classic model racing engine which most closely suggested the design of the Allouchéry 5 cc model, I’d unhesitatingly choose the American  It's indisputably evident that both sets of figures given by Maeght for basically the same engine are incorrect. The 15.0 x 19.8 mm bore/stroke figures for the normally-aspirated engine yield a calculated displacement of only 3.50 cc, while the 19.0 x 19.8 figures cited by Maeght for the experimental “Compresseur” variant work out to a displacement of 5.61 cc. They are in fact the bore and stroke measurements given for the 5.61 cc spark ignition model which was the very first Allouchéry offering (see above).

It's indisputably evident that both sets of figures given by Maeght for basically the same engine are incorrect. The 15.0 x 19.8 mm bore/stroke figures for the normally-aspirated engine yield a calculated displacement of only 3.50 cc, while the 19.0 x 19.8 figures cited by Maeght for the experimental “Compresseur” variant work out to a displacement of 5.61 cc. They are in fact the bore and stroke measurements given for the 5.61 cc spark ignition model which was the very first Allouchéry offering (see above).  from matching holes in the upper cylinder installation flange. These threaded tubes are actually one of the most unusual features of the design. They have small 1.5 mm dia. holes drilled transversely across their upper sections to allow them to be tightened using what amounts to a small 1.5 mm dia. tommy bar.

from matching holes in the upper cylinder installation flange. These threaded tubes are actually one of the most unusual features of the design. They have small 1.5 mm dia. holes drilled transversely across their upper sections to allow them to be tightened using what amounts to a small 1.5 mm dia. tommy bar.

Cylinder port timing is quite aggressive, being fairly typical of racing engines of the late 1940's and early 1950’s. The exhaust opens 105 degrees after Top Dead Centre (ATDC) for a total exhaust period of 150 degrees. The transfer ports open only some 7 degrees later, hence overlapping the exhaust almost completely. Total transfer period is a generous 136 degrees. There is a very short period of supplementary sub-piston induction around top dead centre, but no more than around 16 degrees in total.

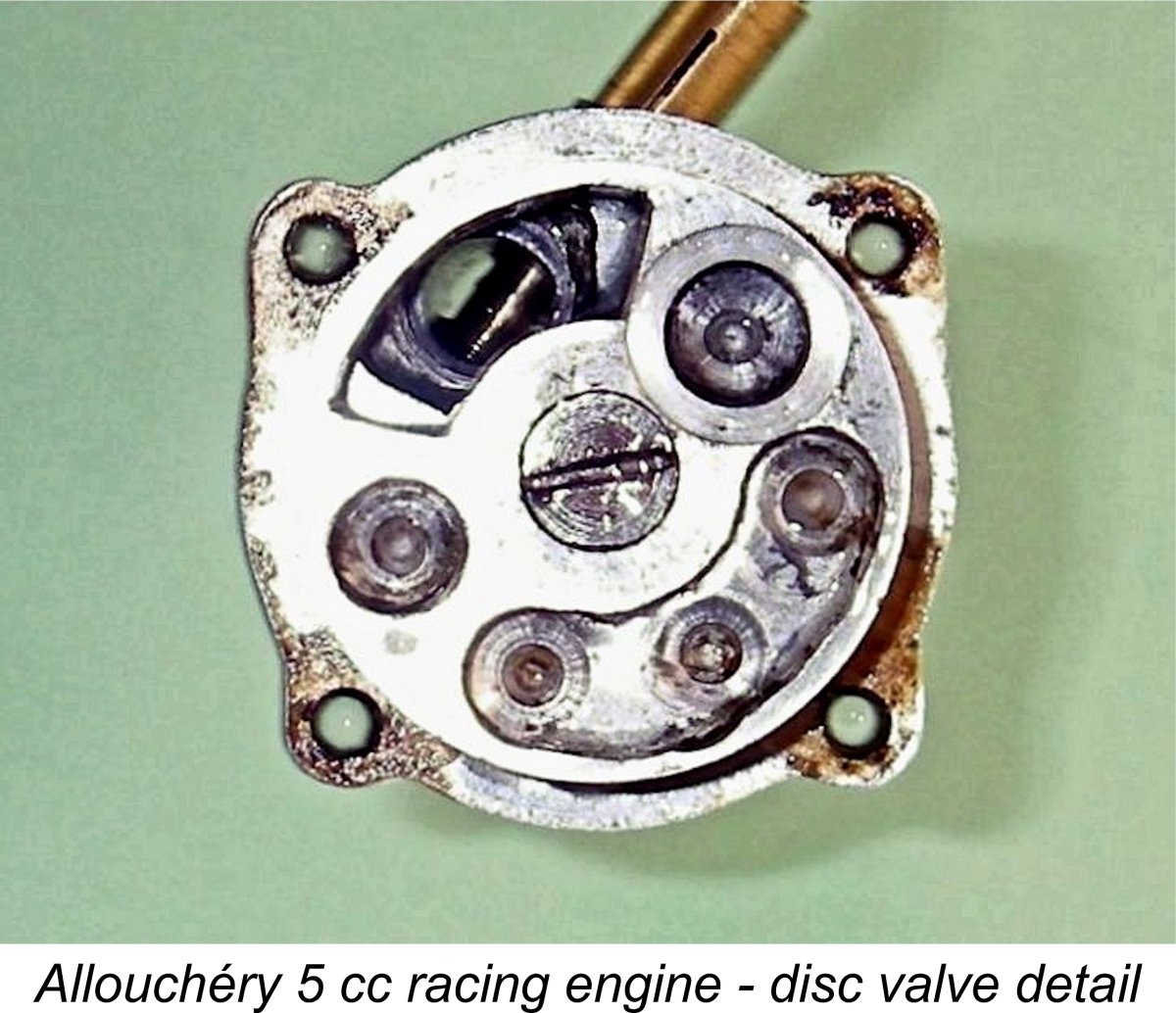

Cylinder port timing is quite aggressive, being fairly typical of racing engines of the late 1940's and early 1950’s. The exhaust opens 105 degrees after Top Dead Centre (ATDC) for a total exhaust period of 150 degrees. The transfer ports open only some 7 degrees later, hence overlapping the exhaust almost completely. Total transfer period is a generous 136 degrees. There is a very short period of supplementary sub-piston induction around top dead centre, but no more than around 16 degrees in total. The backplate is machined from another well-produced gravity die-casting. It is attached to the crankcase using four slot-head screws and is extensively drilled externally, presumably to save weight. A cast-in kidney-shaped induction window is formed in the front face of this component. The disc valve is of light alloy, a material which had fallen into general disfavour for this application by the mid 1950’s. It is mounted on a closely-fitted central steel pin which is secured against rotation using an external lock-nut at the rear.

The backplate is machined from another well-produced gravity die-casting. It is attached to the crankcase using four slot-head screws and is extensively drilled externally, presumably to save weight. A cast-in kidney-shaped induction window is formed in the front face of this component. The disc valve is of light alloy, a material which had fallen into general disfavour for this application by the mid 1950’s. It is mounted on a closely-fitted central steel pin which is secured against rotation using an external lock-nut at the rear.

Having dealt with the dating issue, at least to my own satisfaction, we still want to find out how well the Allouchéry 5 cc “Vitesse” model ran! Only one way to find out - give it a go!

Having dealt with the dating issue, at least to my own satisfaction, we still want to find out how well the Allouchéry 5 cc “Vitesse” model ran! Only one way to find out - give it a go!

For some hard evidence in support of my views, I can refer to my previously-reported testing of the

For some hard evidence in support of my views, I can refer to my previously-reported testing of the  Following the 1966 release of this model, the company did make one final effort to remain in the model engine business. In early 1967, the revived range finally attracted some notice in the foreign modelling press. Peter Chinn mentioned the range in his “Latest Engine News” feature in the January 1967 issue of “

Following the 1966 release of this model, the company did make one final effort to remain in the model engine business. In early 1967, the revived range finally attracted some notice in the foreign modelling press. Peter Chinn mentioned the range in his “Latest Engine News” feature in the January 1967 issue of “