|

|

The Batzloff Triumph Racing Engines

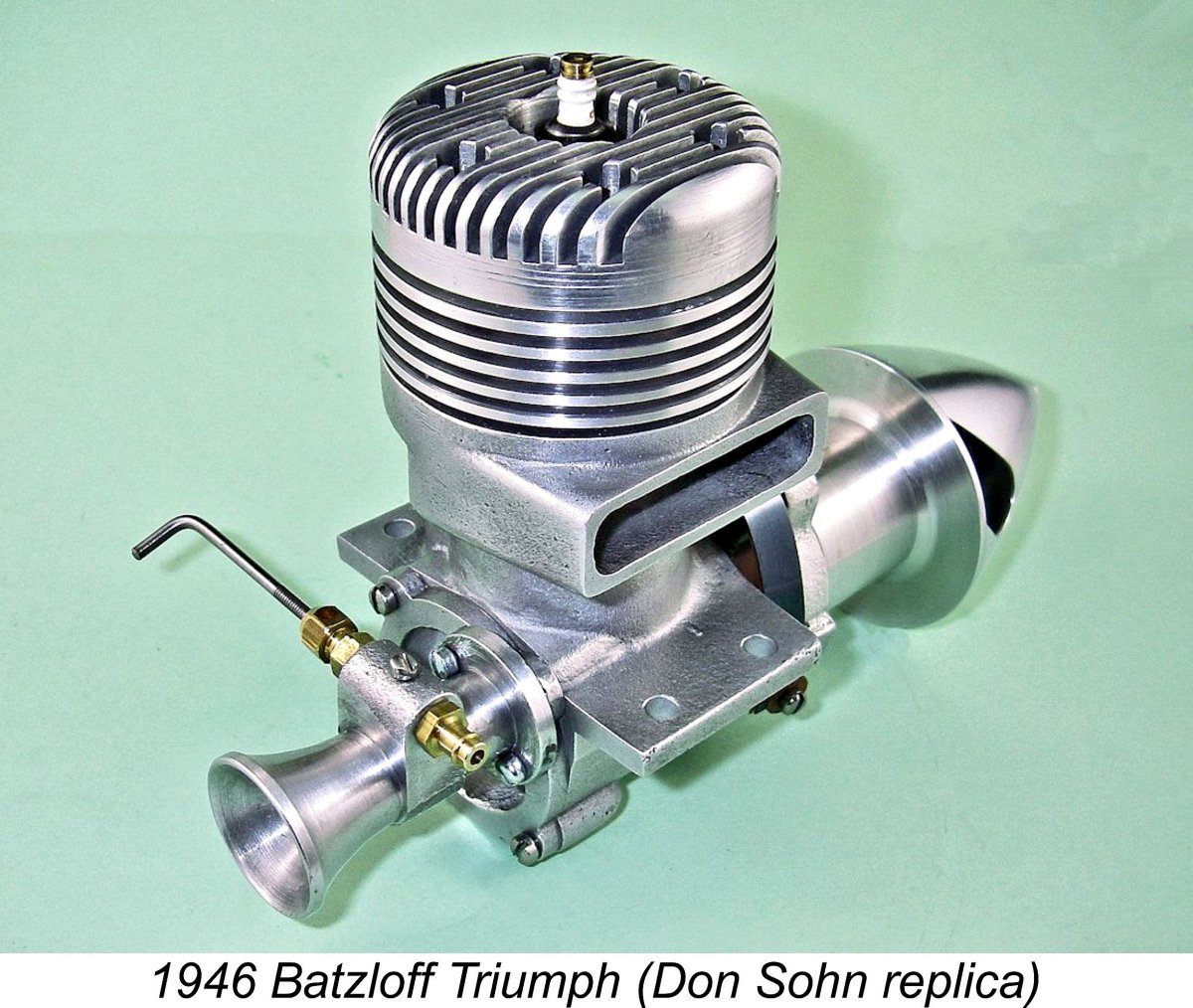

This article will represent yet another addition to my now long-running series of articles on classic big-bore racing engines of the early post-WW2 era. In previous articles I’ve covered such classics as the Hornet 60, the Dooling 61, the Ball 60, the Hassad .60 cuin. series, the Ken 61, the Orr Tornado 65, the Bungay Hi-Speed 600 and the Baab-Fox .604 from the USA as well as the Rowell 60, the Nordec 60 and the Ten-Sixty-Six Conqueror from Great Britain, the Queen Bee 60, Monarch 600 and Banshee .604 from Canada, the Tempest 60 from Australia and the Mamiya 60 RV and Hope Super 60 from Japan. Time now to take a look at two of the more obscure members of this select group - the successive Batzloff Triumph .604 cuin. racing engines. The Batzloff Triumph engines were the products of a small-scale model racing engine development venture which was undertaken by William J. "Bill" Batzloff (1912-1966) of San Diego, California, USA between 1941 and 1947. Bill’s efforts resulted in the appearance of two successive and widely differing model racing engines, both of which were sold locally in very small numbers as the Batzloff Triumph. The use of the same name for both models obscures the fact that they were very different designs, as will soon become apparent. Before getting started, there are several very important acknowledgements which it's my pleasure to make. To begin with, finding an original example of the Batzloff engines today is somewhat akin to running across a mixture of rocking horse droppings and hens’ teeth – not a frequent occurrence! Accordingly, I would have been quite unable to present any useful information on these engines if it wasn’t for my good fortune in acquiring several superb latter-day reproductions of the Batzloff engines made by my valued and mega-talented friend Don Sohn (b. 1934) of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, USA.

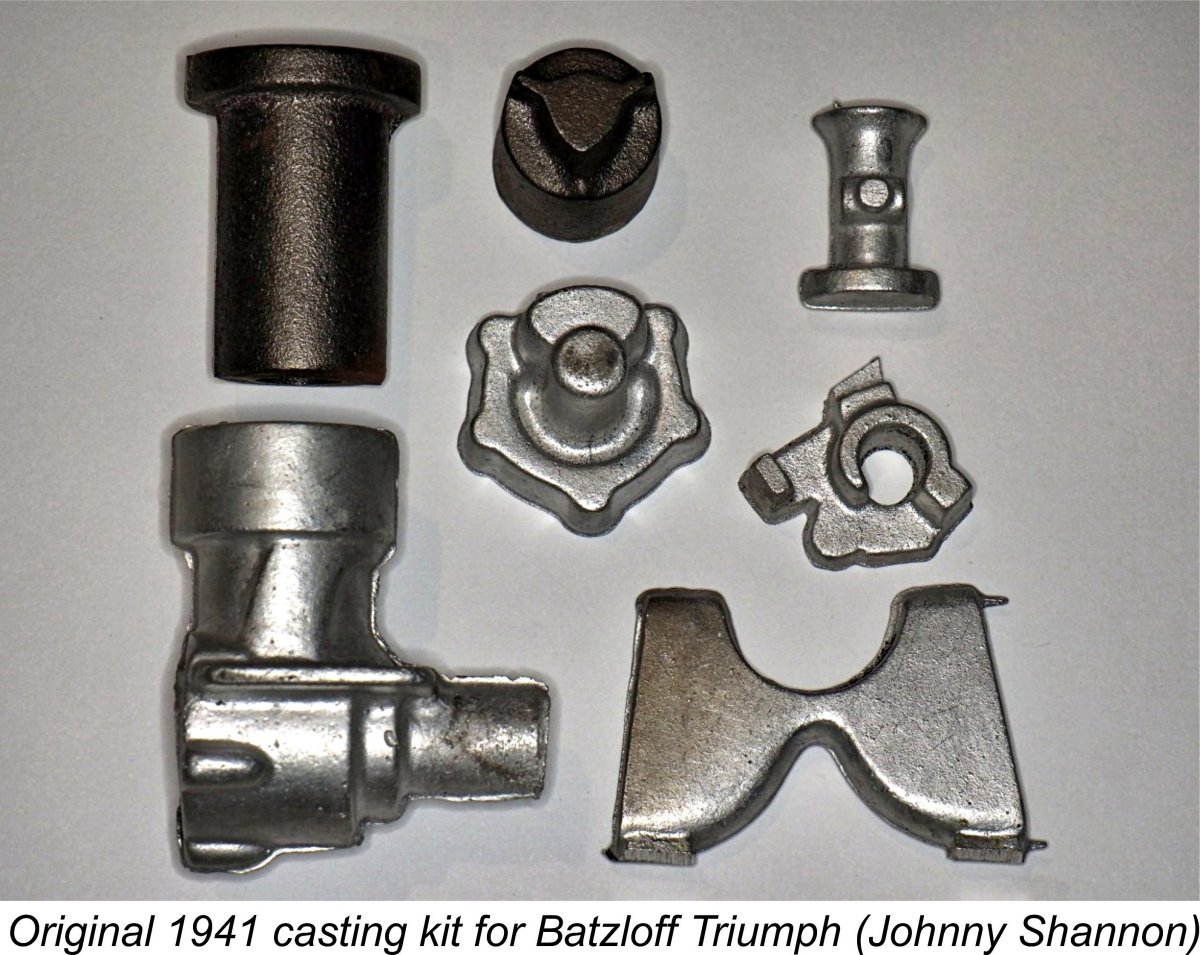

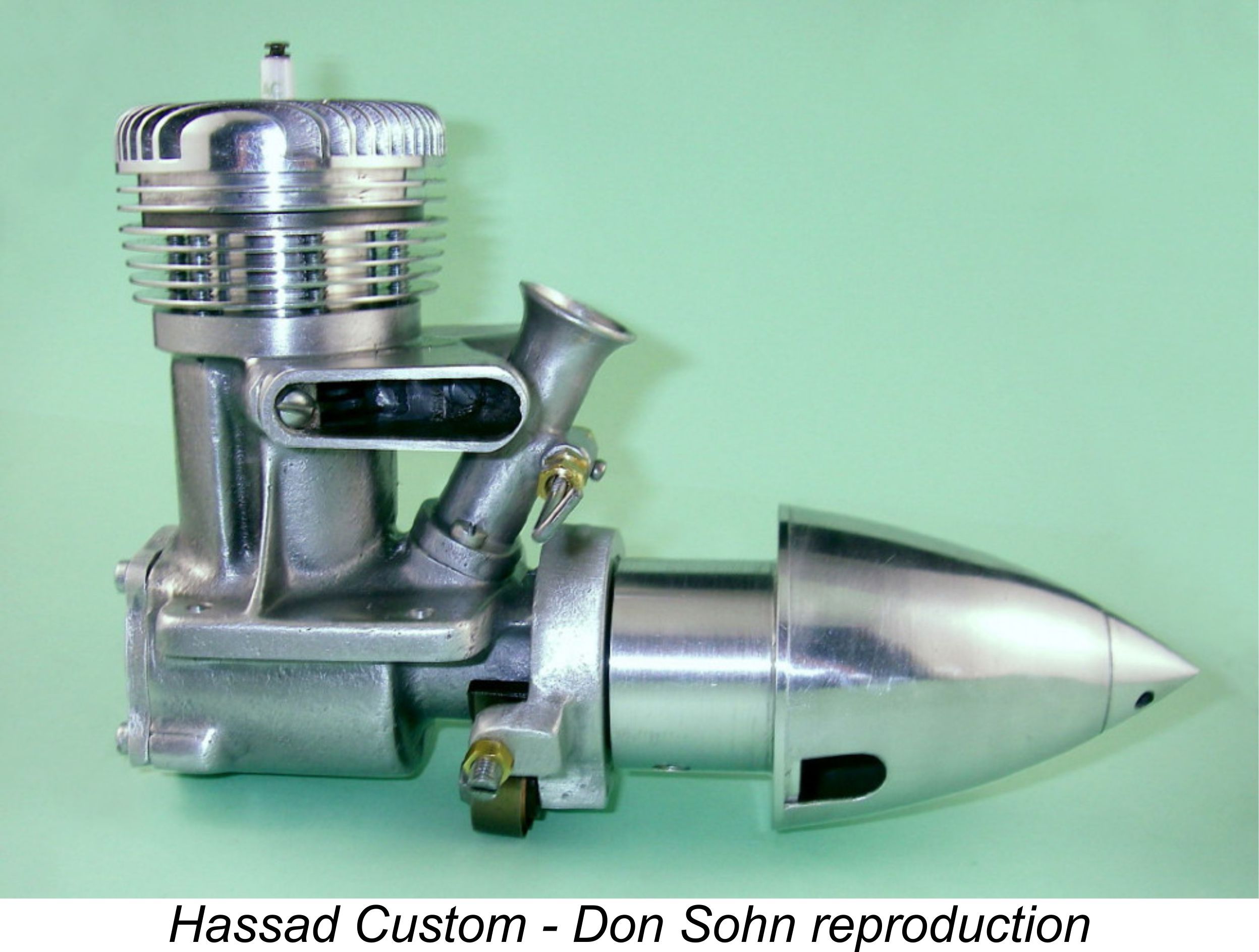

In one of the later sections of my previously-linked article on Ira Hassad, I covered the story of Don’s stellar model engineering career in some detail. Those interested in learning more about Don's work are referred to that article. For now, it will suffice to say that the present-day rarity of original Batzloff engines is such that I would have been quite unable to present first-hand images of either model were it not for the opportunity to examine the fine replicas so painstakingly produced by Don to his usual very high standards. All of the images of Batzloff and Hassad engines which accompany the present article reflect Don’s outstanding work in replicating these engines to an extremely high standard of accuracy and precision. I’m sure that you’ll be as impressed as I have been! Secondly, I wish to thank my valued friend Johnny Shannon of the USA for his support and assistance in the completion of this project. Johnny has taken a personal interest in the life and work of Bill Batzloff and was unstinting in his willingness to share that information with me. Of particular interest was the set of 1941 Batzloff castings which remain in Johnny's possession. Thanks, mate! Now, a little background to get things started ………….. Background

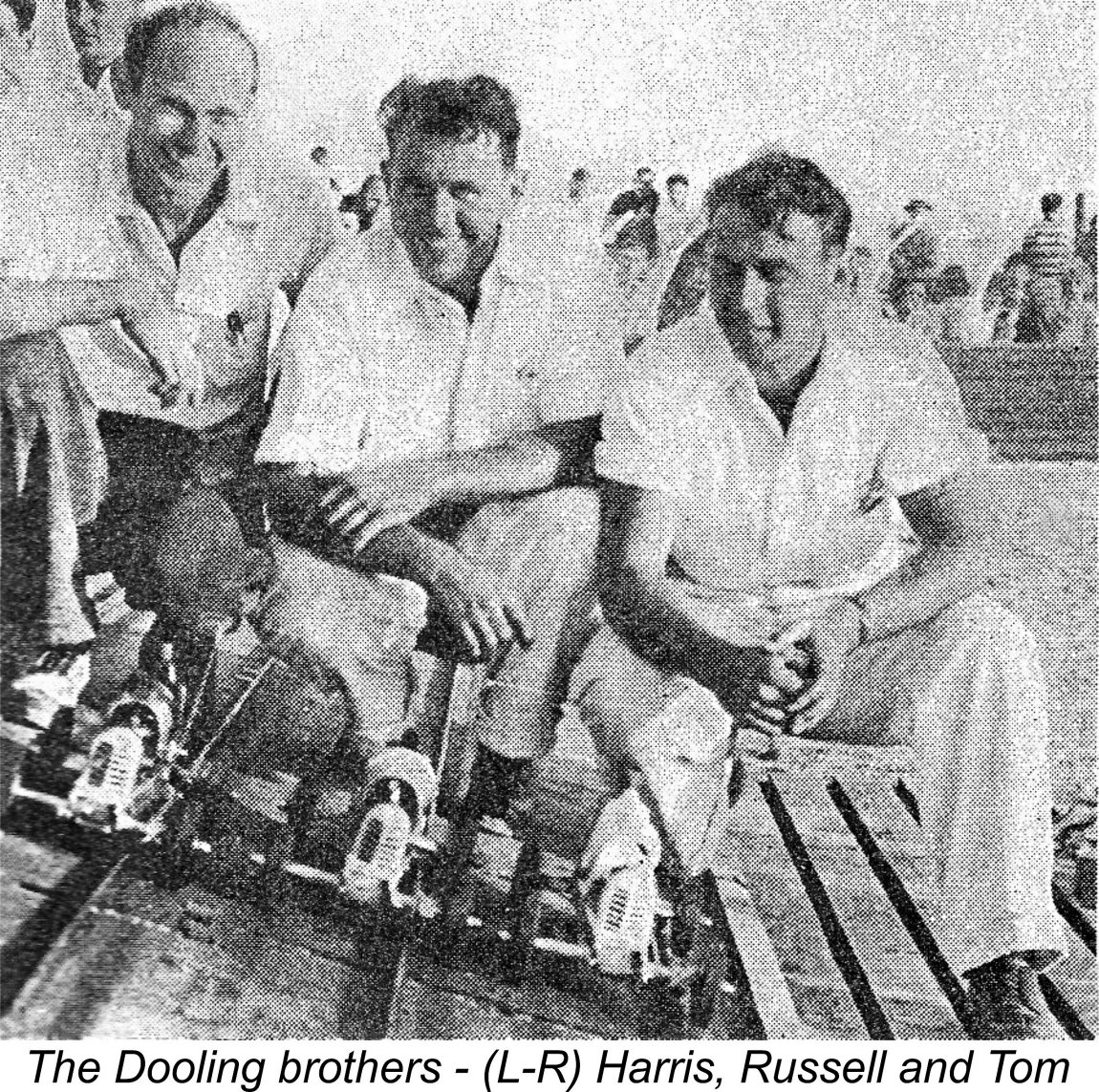

Despite the fact that the Great Depression was still in full swing at the time, the Brown was developed quite rapidly and was quickly challenged by a number of rival products, predominantly manufactured in the USA. A number of constructors both in the USA and elsewhere paid it the very high compliment of producing virtual clones, including the makers of the little-known Winner engine in far-away Australia and the manufacturers of the AMM-1 in Iron-Curtain Russia. The Brown's influence had a long reach! Prior to 1937, the majority of model engines were used to power large free flight model aircraft. like the Brown Junior-powered Australian model shown in the image below. Since these models were generally uncontrolled following launch (R/C was very much in its infancy), attempts to achieve high speeds would have been potentially hazardous, to say nothing of the difficulty of obtaining accurate speed measurements. However, the human race being the competitive species that it is, the above limitations did not prevent contests for power model During these early stages of powered model aircraft development, performance-oriented competitions were based strictly upon flight duration. The first priority was simply to get the model into the air within the allocated time limit, and the second was to keep it up there as long as possible on a given engine run. Since allowable running time was then considerably greater than it is today, all-out engine power was less critical at this stage than ease of starting, overall dependability and consistency in operation. Light weight was also an important factor. Although tethered hydroplane racing was taking place during this period, its popularity did not match that of model aircraft. Moreover, most consistently successful hydro practitioners tended to make their own specialized powerplants. There was thus little stimulation for the commercial development of all-out model racing engines at this stage. As a result of this situation, those engine designers having an interest in developing high performance powerplants found their attention drawn towards other forms of power modelling in which the As matters turned out, it was the three Dooling brothers of Los Angeles who jointly possessed both the required imagination and the necessary skills to jump-start this then-new branch of the modelling hobby, which they did beginning in 1937. In a separate article to be found on the late Ron Chernich’s highly-recommended “Model Engine News” (MEN) website, I’ve covered the story of the Dooling brothers’ central role in the establishment of model car racing and their later development of the iconic Dooling 61 racing engine. The initial efforts of the Dooling brothers were sufficiently impressive that a number of other Los Angeles-area residents were quickly attracted to the new form of model competition. It wasn’t long before there were enough operational cars in the greater Los Angeles area that unofficial model car race meetings began to take place on an abandoned lot in Los Among those attracted to this activity was Ira J. Hassad (1915–1981), who was then working for Major Corliss C. Moseley at his Aircraft Industries plant located at Grand Central Terminal in Glendale, California, some 12 miles to the north of downtown Los Angeles. At this time, Hassad was involved in the manufacture of the famous Baby Cyclone engine which had been designed by Bill Atwood and was being produced in significant numbers by Moseley’s company. However, Hassad was becoming increasingly drawn to the idea of striking out on his own. In 1939 at age 24, he left Moseley to rejoin his former colleague Bill Atwood at the Automatic Screw Machine Company on Gage Avenue in Los Angeles, which had been making Baby Cyclone parts under contract to Moseley. At this time, Atwood was getting production going on the Phantom, Torpedo and Bullet series, hence needing all the experienced help that he could get.

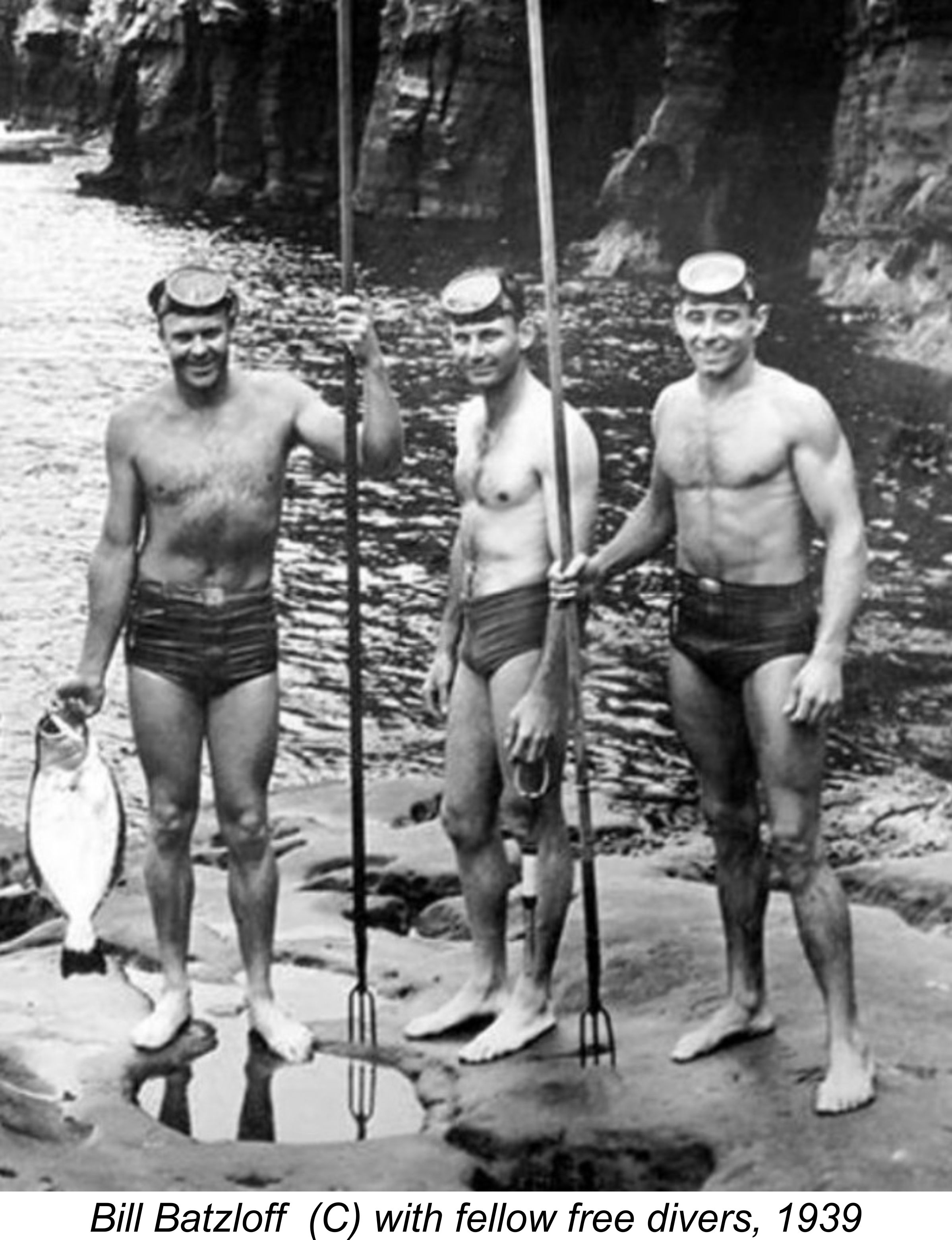

This engine was unique among contemporary racing engines in featuring a twin-stack front exhaust layout and a plain bronze-bushed main bearing without ball races. It represented Hassad’s rejection of what was to become the “standard” racing engine format established in 1939 by the Hornet 60. It actually proved to be superior to the pre-war Hornet in rail-guided car racing, in which its greater torque in the 12,000-13,000 rpm range helped it to accelerate the car out of the turns. As a result, it was extremely popular with exponents of rail-guided car racing, enabling Ira to sell all that he could produce, and at a good price too. As a testament to the engine's popularity, the accompanying photograph at the right However, in tethered cable car racing where the runs were not interrupted by changes in track radius and associated friction, the higher peak horsepower of Ray Snow's disc rear rotary valve (RRV) Hornet 60 gave it a commanding edge. It was thus a bit of a stand-off between the FRV and RRV induction systems at this stage. While all this had been going on in Los Angeles, San Diego resident Bill Batzloff had been pursuing an activity which was totally unrelated to modelling, namely free diving. Batzloff had been born in 1912 in Ohio, but in 1921 when he was nine years old his family had moved to the San Diego area, where he grew up and spent the rest of his life. At some indeterminate point in time after leaving school, he went to work as a research diver and In 1934 (long before the advent of SCUBA) at the age of 22, Bill joined a small group of pioneering free-diving enthusiasts who had formed the legendary San Diego Bottom Scratchers free-diving club in 1933. This club was so excusive that in its first 15 years of existence only 9 individuals (including Bill) managed to pass its initiation test! This first entailed diving to a depth of at least 30 feet and bringing up 3 abalone in a single dive. The next two qualification dives were made to 20 feet from which a wannabe had to bring up a large lobster. If he managed these challenges, he then had to bring up a horn shark tail first - barehanded! It should come as no surprise to learn that the club roster never at any time exceeded 19 members! The club survived all the way down to 2005, when it was voluntarily disbanded by the few remaining members. Perhaps it’s small wonder that from time to time Bill Batzloff sought relief from the challenges of free diving by engaging in other less stressful activities! Although we have no information on Batzloff’s technical qualifications, it appears that among other things he was a skilled machinist. It’s unclear how he became involved with model car racing as a hobby, but by 1940 he seems to Batzloff was soon using Hassad engines in his own model cars and working with Hassad on their further development. Evidently the distance of over 100 miles which separated their homes was no impediment to their evolving relationship. Batzloff actually used one of Hassad’s engines at the 1941 US National model rail car championships in Chicago, a meeting at which Ira himself finished second, competing against the best in the country using his own engine. According to contemporary reports, Ira would have won that event with a new National record had it not been for a high-tension wire which broke while his car was leading the final race, thus spoiling what should have been a winning run at record speed. It seems to have been at about the same time in 1941 that Batzloff came up with a concept for a significantly modified version of the basic Hassad design. This engine was destined to appear in very small numbers under the name of the Batzloff Triumph. It was sold mainly locally by Batzloff under the Batzloff Racing Engines label. Let’s have a look at this initial version of the Batzloff Triumph. The 1941 Batzloff Triumph

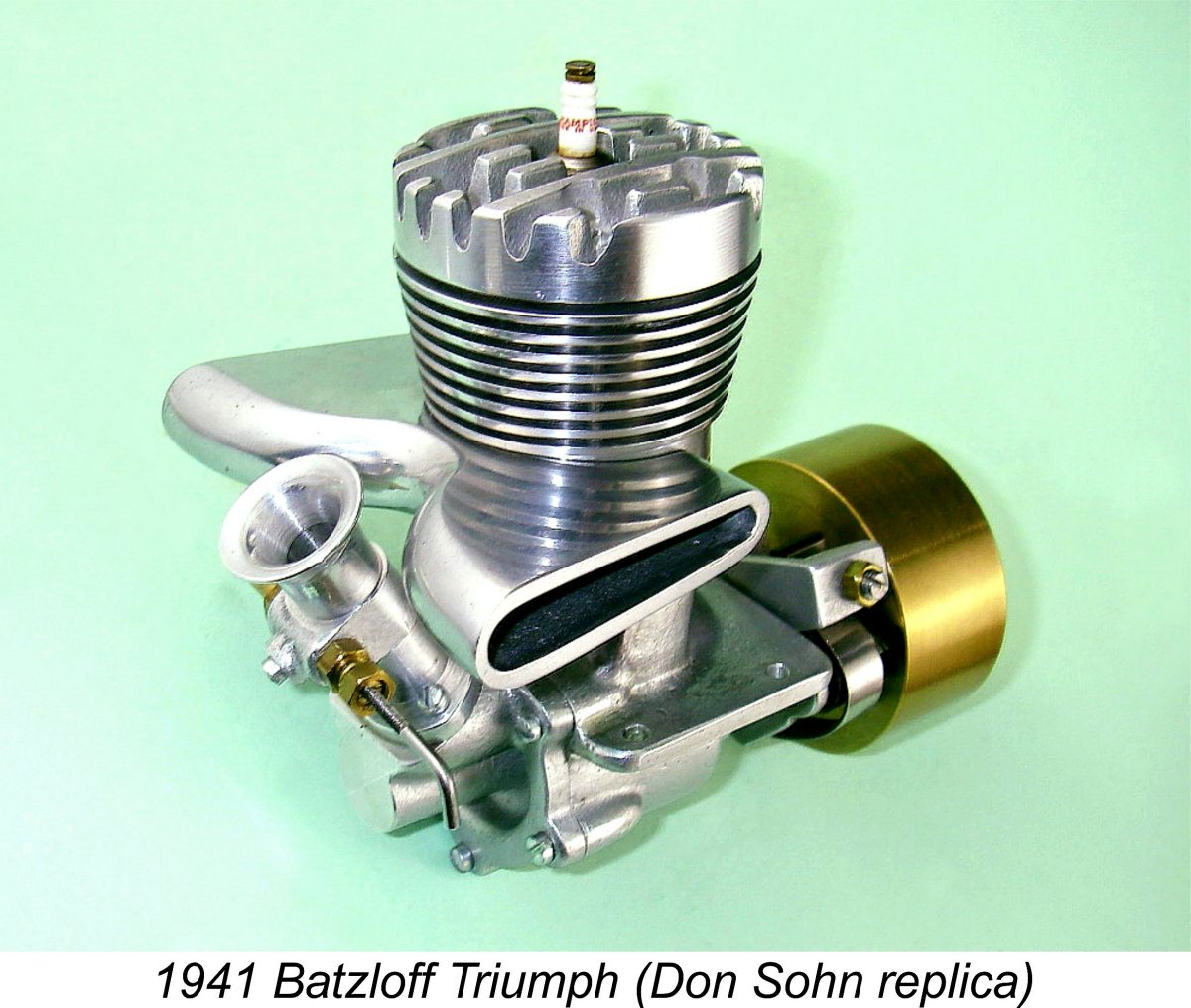

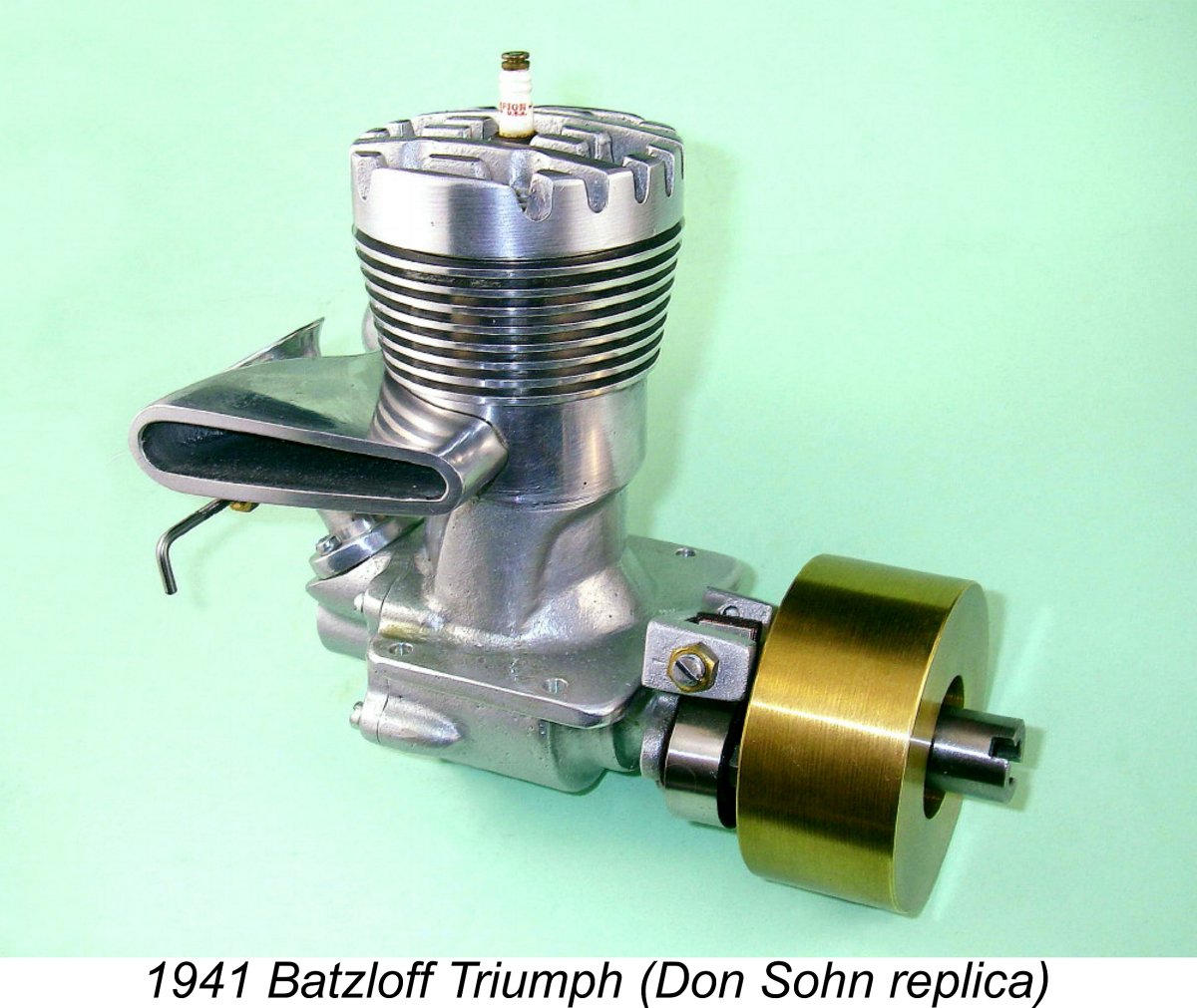

Taking my lead from Tim Dannels' generally-authoritative "American Model Engine Encyclopedia" (AMEE), I have elected to attach the Batzloff Triumph designation to this engine. There's no doubt at all that Batzloff himself adopted this name at some point in time. If authoritative additional evidence should ever come to light, I am of course more than willing to correct my identification. The 1941 Triumph was a very clear reflection of Bill Batzloff’s views regarding potential improvements to the basic Hassad design. Although several of these changes seemed entirely logical, it would appear that Ira Hassad did not share Batzloff’s views since he did not adopt any of the changes himself, leaving Batzloff to produce the castings and machine the finished engines himself under his own name. Bore and stroke of the Triumph were 0.937 in. (23.80 mm) and 0.875 in. (22.22 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 0.6034 cuin. (9.89 cc). These figures essentially duplicated the corresponding dimensions of the trend-setting Hornet 60 which had first appeared in 1939. The Triumph reversed the Hassad layout by using a rear drum valve instead of FRV induction. The operating principle was of course identical, the difference being that the drum valve did not have to do double duty by transmitting the engine’s torque in addition to controlling the induction cycle. This arrangement allowed the designer to take far greater liberties in terms of induction port size and associated timing without introducing any undue structural weakness. In fact, it allowed the drum valve unit to be machined from light alloy, thus saving some weight. The alloy drum rotated in a bronze bushing at the rear – a good wearing combination provided the initial fit was reasonably precise. The layout also permitted the use of a crankshaft which was not weakened by any need to incorporate induction porting into its design. A 0.375 in. dia. main journal was used. The Triumph retained the lapped baffle piston and spectacular twin exhaust stacks of the contemporary Hassad model. However, the stacks were placed at the rear of the cylinder instead of at the front, thus keeping them in the same orientation relative to the induction system as in the Hassad models. This placed the “hot” exhaust side of the cylinder facing into the slipstream when the engine was mounted in the usual orientation in car or hydroplane service with the flywheel towards the rear of the vehicle. This would tend to promote more uniform cylinder temperatures around its circumference. The slight angle towards the flywheel at which the discharge ends of the stacks are cut suggests that this was the anticipated mounting orientation. However, Batzloff didn't stop there. Apart from the change in the induction arrangements and exhaust orientation, the Triumph incorporated a few additional features which set it well apart from its Hassad progenitor. One substantial change was the addition of a single ball-race at the rear end of the crankshaft. The front of the shaft was supported in a closely-fitted bronze bushing. The Hassad design utilized a bronze bushing for the entire main journal, without the inclusion of a ball-race.

Another significant change from the Hassad design was the configuration of the bypass passages. The Batzloff design featured twin bypass passages, one on each side, to supply a pair of transfer ports cut into the flywheel side of the cylinder wall. This was in contrast to the Hassad model, which utilised a single large bypass bulge at the rear to supply the transfer ports. This change was forced upon Batzloff by the fact that what used to be the unobstructed lower point of entry to the Hassad's bypass was now occupied by the crankweb and the rear ball race. Perhaps incidentally, the arrangement also exerted some directional influence on gas flow during the transfer process, since the incoming mixture now entered the transfer ports from the sides rather than vertically. Shades of Enya and MVVS in later years ........... Reviewing the above description, it becomes apparent that the 1941 Batzloff Triumph was far more than a “back-to-front” Hassad model, as it has sometimes been characterized - it was in fact a completely distinct design bearing only a superficial resemblance to the Hassad model. Taking into account the improved induction potential of the drum valve, the addition of the ball-race and the more advanced transfer arrangements, I would objectively expect this engine to have a somwhat higher performance potential than that of the basic Hassad offering. It's actually a pity that the onset of WW2 put a premature end to its career before it really had a chance to show what it could do. One somewhat odd feature of the 1941 Batzloff which was unrelated to performance was the fact that it was timed for “reverse” rotation. Don Sohn has confirmed that he copied this feature exactly when constructing his fine reproductions, so there’s no doubt at all regarding this fact. The drum valve is timed so that the engine runs in a clockwise direction when viewed from the flywheel end. The idea behind this feature was most likely to utilize the engine’s torque to create a tendency for the car (or hydroplane) to turn to the left. This would reduce the vehicle’s resistance to turning in what would be the normal direction for tethered or rail-guided racing. Power not required to overcome turning resistance would then be available to generate speed - a very logical concept. Bill Batzloff appears to have put a lot of thought into this design!

Batzloff also apparently made perhaps a dozen complete engines to custom order before production was curtailed by the onset of WW2 (as far as the USA was concerned) in December 1941. It’s highly unlikely that the total number produced, either as castings or complete engines, reached anywhere near three figures. The complete unit illustrated above is one of five superb examples constructed from his own replica castings by Don Sohn, whose invaluable assistance in the preparation of this article has already been acknowledged. It was supplied by Don in its original flywheel-equipped car version as illustrated. Although some examples may have been converted to aero configuration, it’s pretty well certain that all of the originals were used in model car applications, although one or two may have served as tethered hydroplane powerplants. As noted earlier, America’s entry into WW2 in December 1941 put an end to model racing engine development for the next few years. However, one positive result on a strictly inter-personal level was the fact that Ira Hassad was relocated to San Diego in order to apply his engineering talents to war-related research projects. He spent the war years working for the US Navy as a machinist at their “Sound Lab” located at Fort Rosecrans Naval Base at Point Loma near San Diego. He later told his son Jim (b. 1949) that he was primarily engaged in making prototype parts for sonar systems, which at that time represented a top secret technology. In undertaking this work, Ira had in fact become a colleague of his friend Bill Batzloff, who was working at the same time on different aspects of the same development program through his ongoing employment at the nearby Scripps Institute of Oceanography in San Diego. The situation doubtless facilitated the further cementing of the friendship between the two men. Jim Hassad recalled his father speaking "kindly" of Bill Batzloff in later years. Interestingly enough, Jim tells us that Ira Hassad's interest in miniature engines pretty much evaporated during the war. He became very interested in Germany’s prewar Grand Prix racing car developments with their Auto-Union and Mercedes models, spending much of his personal time during this period reading extensively and taking classes on related subjects such as internal combustion engine supercharging. This was to stand him in good stead later on when he switched his full attention to high-performance full-sized automobiles. More of that elsewhere........... The 1946 Batzloff Triumph

By 1946 Ira had established himself in premises located at 1427 Garnet Street in San Diego, trading under the company name of Hassad Experimental Machinists. Here he produced the individually hand-crafted Hassad Custom .61, a true masterpiece once again featuring FRV induction and a twin-stack front exhaust, but now with a twin ball-race crankshaft. Evidently his pre-war H.R.E. experiment (of which more elsewhere) had failed to convince him to follow the general trend by switching to RRV induction. According to Clarence Lee, who knew Ira Hassad personally, the Custom was actually designed by Bill Batzloff, whose enthusiasm for model engines had by no means diminished at this stage. However, the engine was manufactured by Hassad, as the name suggests. This division of responsibilities is almost certainly a reflection of Ira's fading interest in model engines, although their manufacture It’s apparent from a review of his post-war activities going forward to 1948 that Ira Hassad remained a staunch advocate of the FRV system of induction as well as his unique front exhaust twin-stack scavenging layout. However, Bill Batzloff evidently wasn’t totally convinced. After helping Ira to get the Custom .61 up to production standard, Batzloff went his own way once more, working independently at his own pace on a completely different design which closely followed the configuration established by the Hornet and early McCoy 60 RRV models. It seems pretty clear that Batzloff's "day job" at the Scripps Institute left him with insufficient free time to engage in a serious series production effort in concert with Ira. He appears to have been content to pursue his model engine activities on his own account as time permitted.

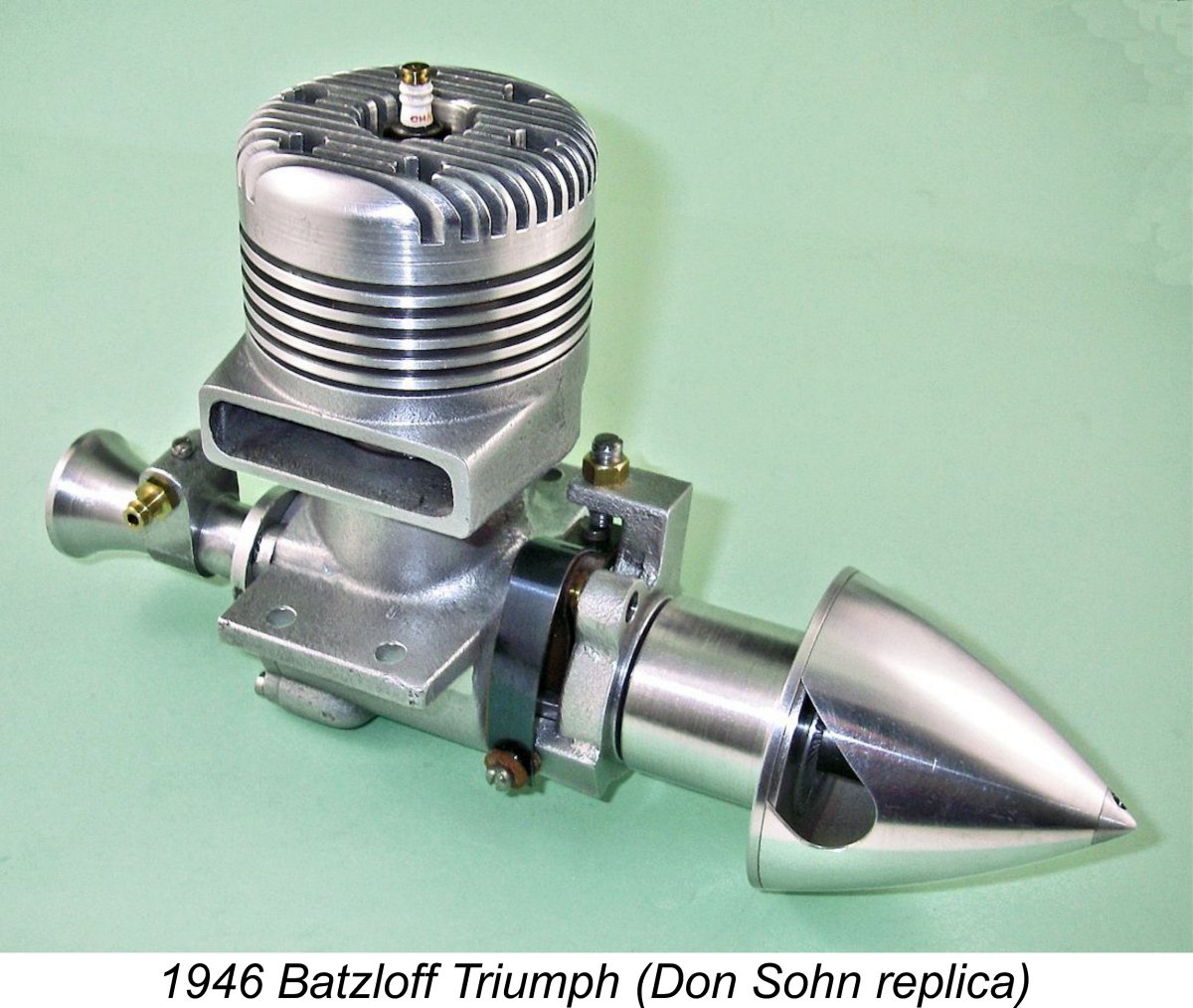

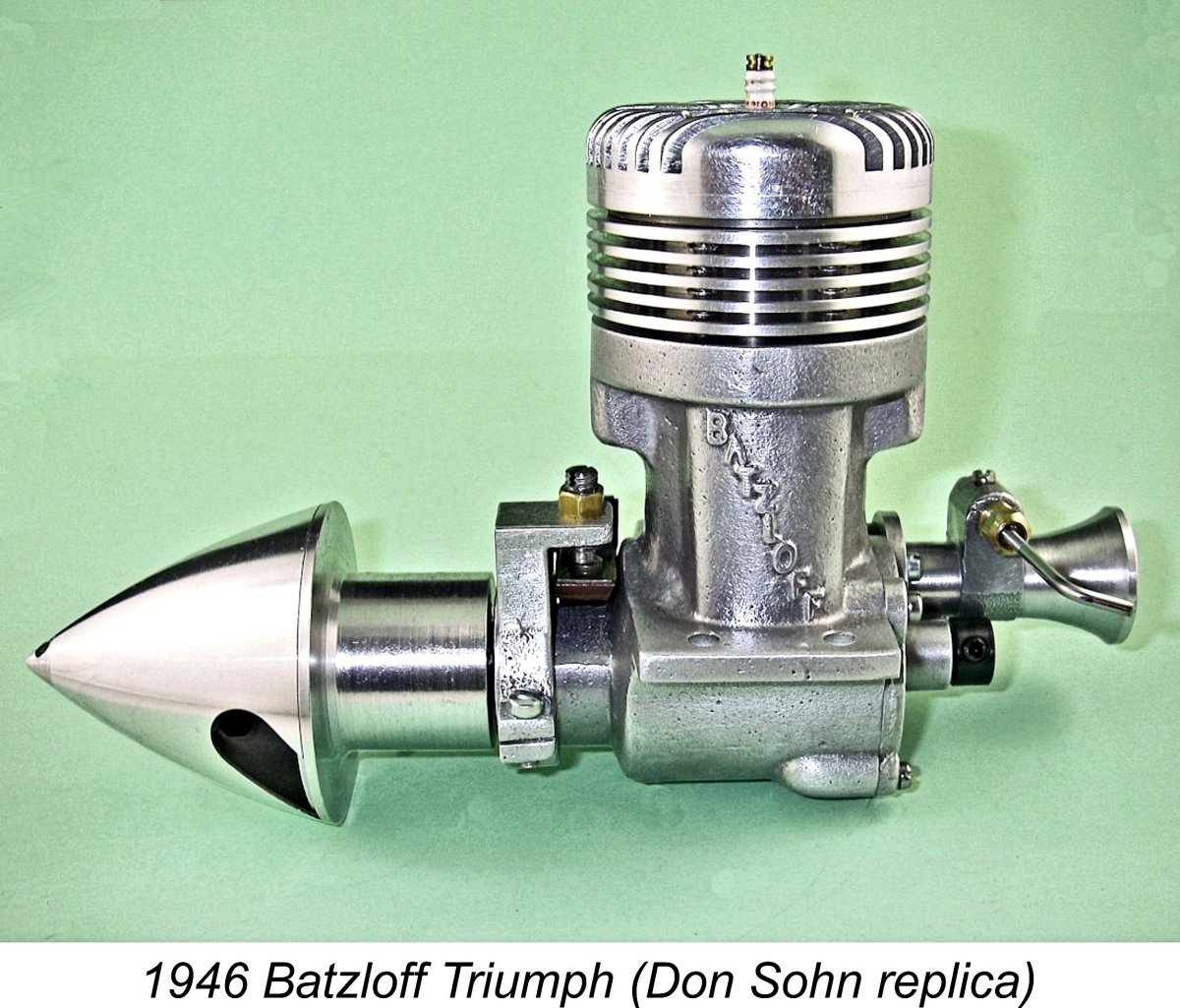

Bill Thompson later reported in the pages of ECJ that the plans for this engine were dated 7-3-46, confirming the engine’s year of introduction. Batzloff also made a very few complete engines, presumably for his own use and that of his friends. The total number sold cannot have been large. That said, at Bill Thompson’s time of writing Bob Murphy of San Diego was able to confirm that at least three original examples of this model still existed in San Diego to his first-hand knowledge. They are out there! The 1946 version of the Batzloff Triumph was a completely revised design bearing almost no relationship to the pre-war model described earlier. It featured disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction along with cross-flow loop scavenging and a conventional side-stack exhaust instead of the twin-stack front exhaust seen on all of the Hassad designs up to that point in time. A ringed light alloy baffle piston was now employed along with a twin ball-race crankshaft. Basically, Batzloff appeared to be switching his allegiance to the Hornet design school as opposed to that pioneered by Ira Hassad. The one throw-back Hassad feature was the form of the intake venturi. This retained the typical long throat of the Hassad designs along with Ira’s trademark fuel jet arrangement with remote needle. Why change a good thing??

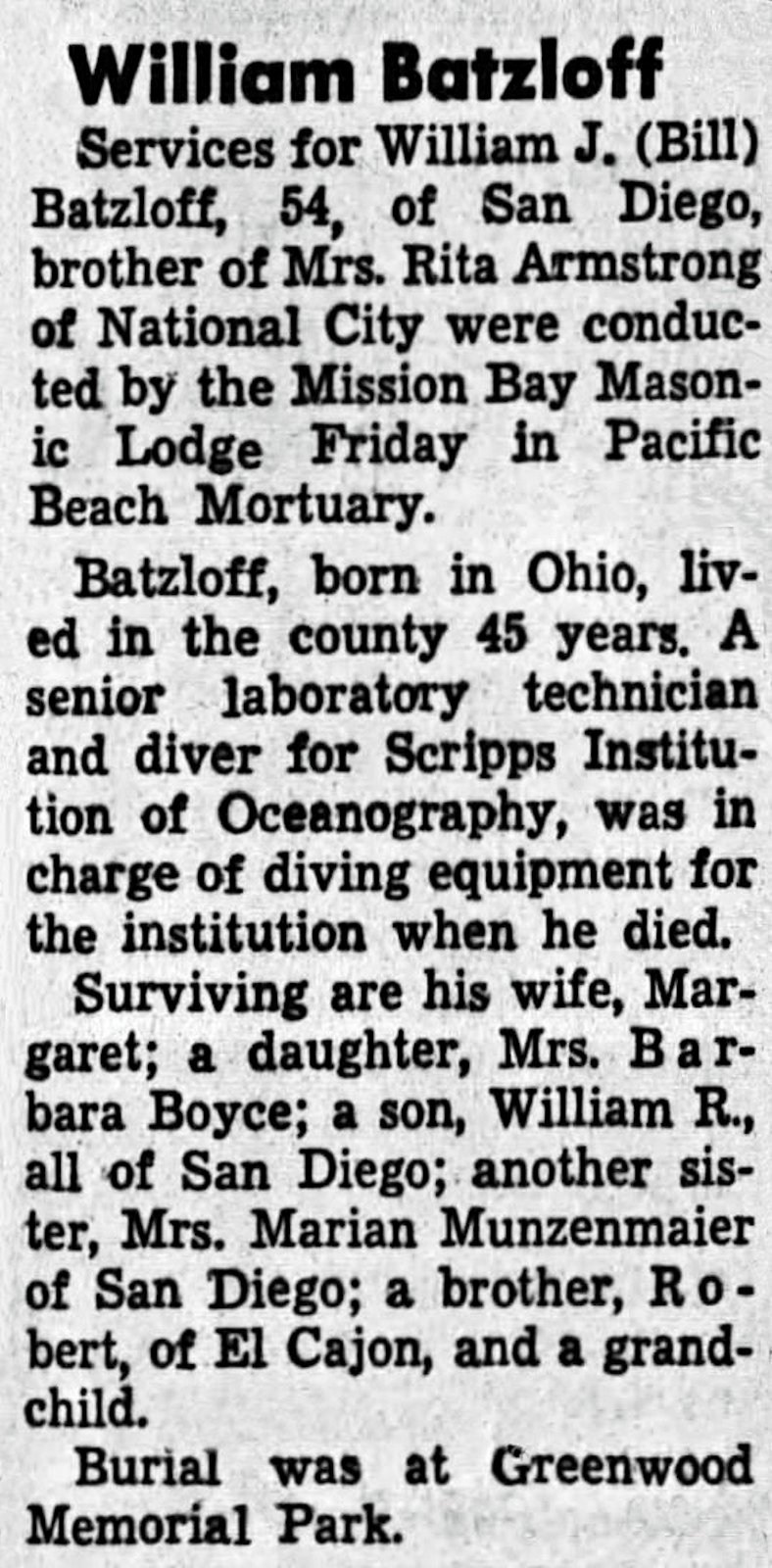

The illustrated example of the 1946 Batzloff Triumph is one of a small number of outstanding reproductions built by Don Sohn. It is in aero configuration, reflecting the increasing importance of that market area at the time. However, there can be little doubt that many if not most of these engines were used in car service. It’s presently unclear how long Bill Batzloff continued to offer the post-war Triumph, but it’s unlikely that the engine survived for long against the combined marketing might of Hornet, McCoy, Ball and (later) Dooling. I’d be really surprised to learn that the engine remained on offer past 1947. After he ceased working on model racing engine development, Bill Batzloff appears to have returned to the diving world as his main preoccupation, as indeed it may have been all along. He continued to work for the Sadly, Bill Batzloff died rather prematurely in 1966 at the age of only 54 years while still working at the Scripps Institute. According to information obtained by Johnny Shannon, he actually passed away in a doctor's waiting room while awaiting an examination. The attached obituary notice appeared in the August 7th, 1966 edition of the Chula Vista Star-News. Batzloff was buried at Greenwood Memorial Park in San Diego. Conclusion The Batzloff Triumph engines stand as an interesting testament to one enthusiast's evolving vision of what might constitute a successful racing engine at the respective times of release of his two designs. Being separated in time by some five years, it’s only to be expected that the passage of time as well as changes in the modelling landscape would influence changes in their designer’s thinking. The Batzloff engines illustrate this point very well indeed. In this context, it's interesting to note that as of 1941 Batzloff continued to see Ira Hassad's somewhat individualistic design approach as representing the most promising development pathway to follow. His 1941 design represented a very sincere and logical attempt to improve upon the basic Hassad formula. However, by 1946 Bill had clearly read the writing on the wall and was already able to foresee the eventual dominance of the RRV side-stack designs represented by the Hornet, McCoy and (later) Dooling engines among others. In achieving this recogntion, he was well ahead of his friend Ira, who only conceded to the RRV concept with his very last model racing engine, the one-off Hassad Barstock Special prototype of the late 1940's. I have yet to try running either of my Don Sohn replicas. If I ever get around to doing so, I will add the results to this article. In the meantime, I hope you’ve enjoyed this testament to the design abilities of one of the largely forgotten model racing engine designers of the pioneering era! _________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published September 2019

|

| |

Regular visitors to this site have met Don before in my articles about

Regular visitors to this site have met Don before in my articles about  Although a limited number of small I/C engines potentially suitable for model use had been offered for sale in various parts of the world from 1909 onwards, the 1931 introduction of the 0.601 cuin. (9.85 cc) Brown Junior spark ignition motor in the USA is generally considered to mark the first step towards the true commercial-scale series manufacture of model engines worldwide. The first dozen or so engines were individually constructed by

Although a limited number of small I/C engines potentially suitable for model use had been offered for sale in various parts of the world from 1909 onwards, the 1931 introduction of the 0.601 cuin. (9.85 cc) Brown Junior spark ignition motor in the USA is generally considered to mark the first step towards the true commercial-scale series manufacture of model engines worldwide. The first dozen or so engines were individually constructed by

All well and good, but by now Ira had become interested in the emerging and rapidly expanding sport of model car racing, finding himself tempted by the challenge of developing his own all-conquering race car engine. He was undoubtedly aware of the front-running Hornet 60, but thought that he could do better. In September 1939, using a $300 loan from close friend and

All well and good, but by now Ira had become interested in the emerging and rapidly expanding sport of model car racing, finding himself tempted by the challenge of developing his own all-conquering race car engine. He was undoubtedly aware of the front-running Hornet 60, but thought that he could do better. In September 1939, using a $300 loan from close friend and

There is actually a degree of uncertainty regarding the correct name for this engine. My friend Johnny Shannon owns an original casting set for this model (see below) which came to him in an unlabelled and very "experienced" box containing a note designating the engine as the Batzloff Racer. Of course, this note could have been written by an unknown previous owner at any time prior to Johnny acquiring the castings. This means that the name on the note cannot be regarded as authoritative - we don't know when and by whom the name was written, or on what authority the name was applied.

There is actually a degree of uncertainty regarding the correct name for this engine. My friend Johnny Shannon owns an original casting set for this model (see below) which came to him in an unlabelled and very "experienced" box containing a note designating the engine as the Batzloff Racer. Of course, this note could have been written by an unknown previous owner at any time prior to Johnny acquiring the castings. This means that the name on the note cannot be regarded as authoritative - we don't know when and by whom the name was written, or on what authority the name was applied.

Following the conclusion of WW2, Ira Hassad remained in San Diego. Although his interest in model engines had waned considerably, he still had a living to make. He therefore returned at least for a time to the activity which he knew so well, namely the manufacture of high-performance model racing engines.

Following the conclusion of WW2, Ira Hassad remained in San Diego. Although his interest in model engines had waned considerably, he still had a living to make. He therefore returned at least for a time to the activity which he knew so well, namely the manufacture of high-performance model racing engines.

In 1946 Batzloff finalized his new design and began to offer it as a set of castings and plans. His new design featured bore and stroke dimensions of 0.937 in. (23.80 mm) and 0.865 in. (21.97 mm) for a calculated displacement of 0.597 cuin. (9.78 cc). The bore was the same as the previous model, but the stroke had been fractionally reduced.

In 1946 Batzloff finalized his new design and began to offer it as a set of castings and plans. His new design featured bore and stroke dimensions of 0.937 in. (23.80 mm) and 0.865 in. (21.97 mm) for a calculated displacement of 0.597 cuin. (9.78 cc). The bore was the same as the previous model, but the stroke had been fractionally reduced.