|

|

Michigan Masterpieces - the Orr Engines

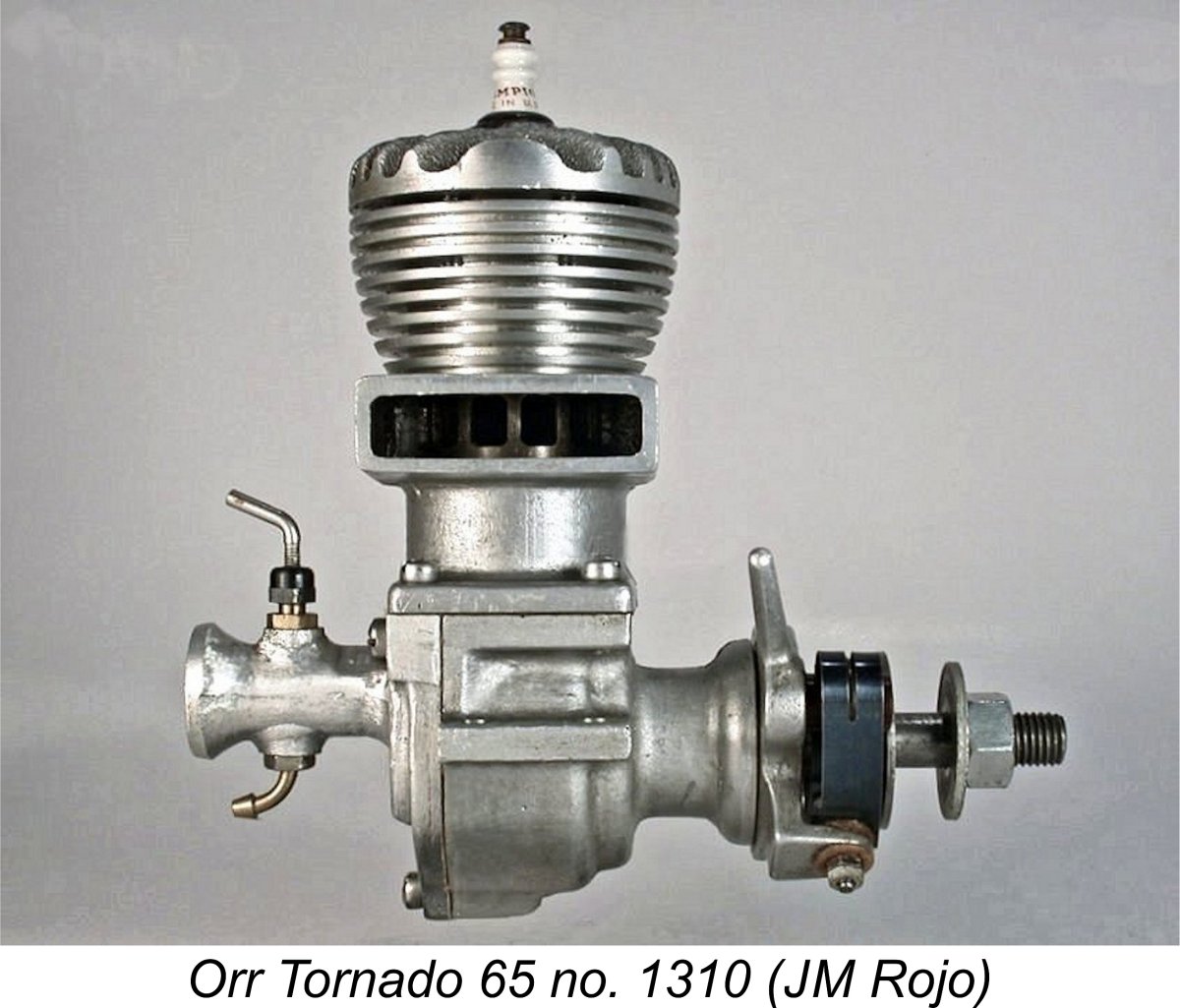

In previous articles I’ve covered such big-bore classic racing engines as the Hornet 60, the Dooling 61, the Ball 60, the Hassad engines, the Batzloff Triumph, the Ken 61, the Bungay Hi-Speed 600 and the Baab-Fox .601 from the USA as well as the Rowell 60, the Nordec 60 and the Ten-Sixty-Six Conqueror from Great Britain, the Monarch 600 and Banshee .604 from Canada, the Tempest 60 from Australia and the Mamiya 60 RV and Hope Super 60 from Japan. Time now to take a look at one of the less widely-known members of this select group - the Orr Tornado .647 cuin. racing engine from Michigan, USA. Before getting started, I'd like to acknowledge a number of individuals without whose help I’d never have got this project off the ground. Anyone having an interest in the Orr engines owes a massive debt to Evan Towne, who undertook a great deal of research on the marque during the 1980’s and early 1990’s when some of those directly involved were still with us. Evan’s findings were published in an article which formed part of issue no. 110 (April 1994) of the late Tim Dannels’ indispensable “Engine Collector’s Journal” (ECJ). It is the major reference upon which the background included in this review is based. If Evan hadn't undertaken his research when he did, much of this information would have been lost forever. My excuse for publishing the present article is that Evan's earlier work is only accessible to those who have (or have access to) a copy of that issue of ECJ. It seems right to me to make that work more widely and readily accessible. Further invaluable research on the Orr engines was subsequently carried out by Dale Jordan, who undertook a survey of ECJ readers and friends to establish the pattern (if any!) of serial numbers and associated features of As always when dealing with an American engine, I’d like to thank my late friend and mentor Tim Dannels for his help in pointing me to the above-referenced source material as well as providing a number of fine images of the Orr engines. Thanks, Tim - couldn’t have done it without you, mate! Finally, I’d like to acknowledge the immense contribution made by my Spanish friend José Manuel Rojo, whose magnificent model engine collection is displayed for all of us to enjoy on José Manuel’s fascinating website. When I first tackled this article, I didn’t own an original example of the Orr Tornado 65 to photograph, so I’m extremely grateful to José Manuel for his gracious permission to use the excellent images available on his site as illustrations for my articles. The attached image of Orr Tornado 65 no. 1310 is just a sample of the quality of his work. Muchas gracias, amigo!! Now, on with the story! As usual, I’ll begin by setting the stage. Background

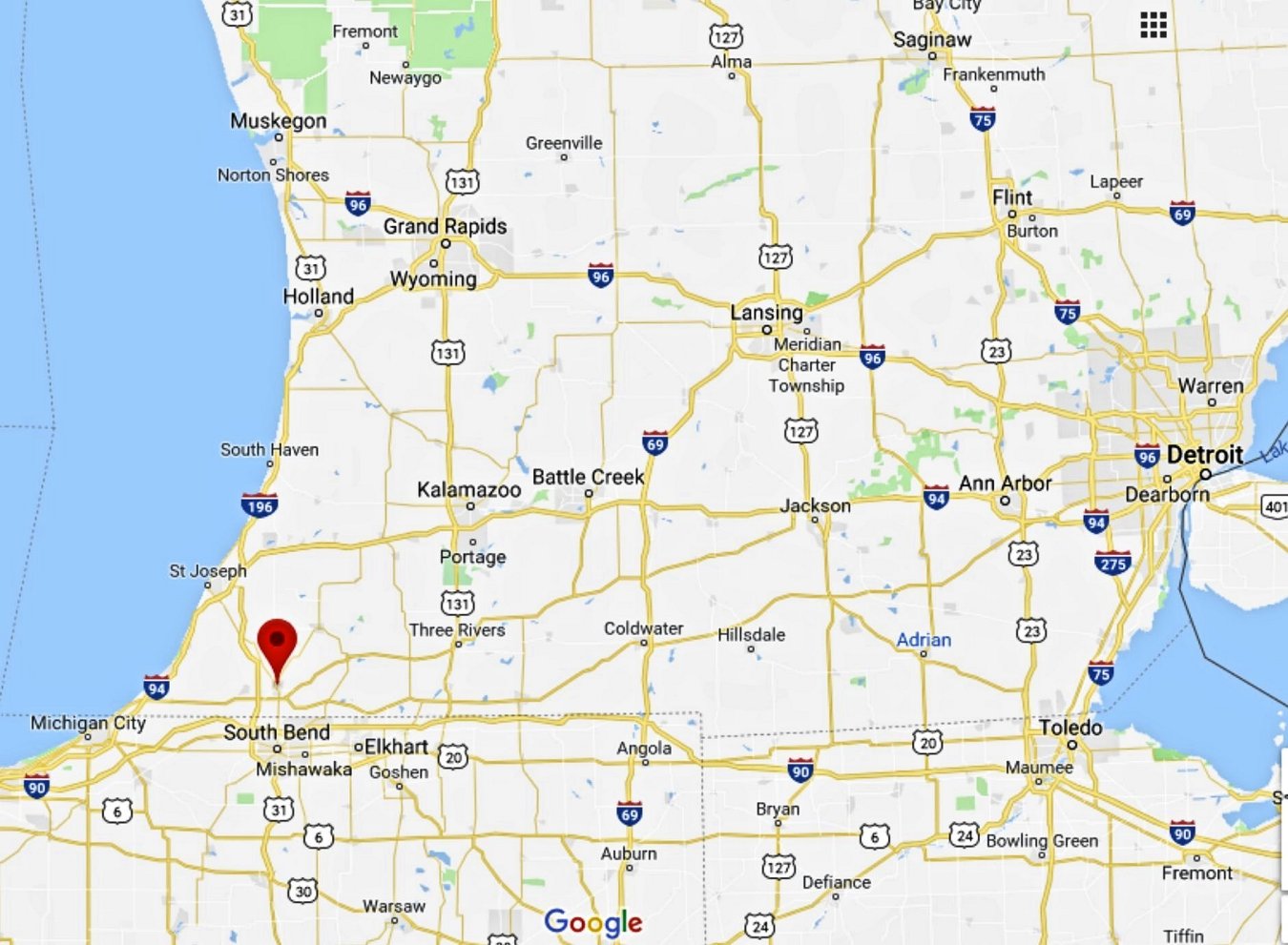

During the WW2 years, Fred worked at the Studebaker plant in South Bend, Indiana where he was involved in the production of the Studebaker US6 truck and the Weasel tracked cargo and personnel carrier for the US military. However, his passion for modelling was unabated, and while working for Studebaker he conceived the idea of designing a model engine of his own and somehow arranging for its production after the war. Money was in short supply, so Fred went to his father to persuade him to float some start-up funding for the venture. In this he was successful. Fred seems to have taken advantage of the September 1944 decision by the US War Production Board to release sufficient material and manufacturing capacity for non-military purposes such as model engine manufacture. His initial design materialized in early 1945 while the war was still ongoing. It would appear that at this stage Fred was not specifically focusing upon designing a full-blown racing engine, because his first design was a fairly conventional .604 cuin. (9.90 cc) crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) model which was mainly distinguished by its twin ball-race crankshaft. The sand-castings were produced by a local foundry.

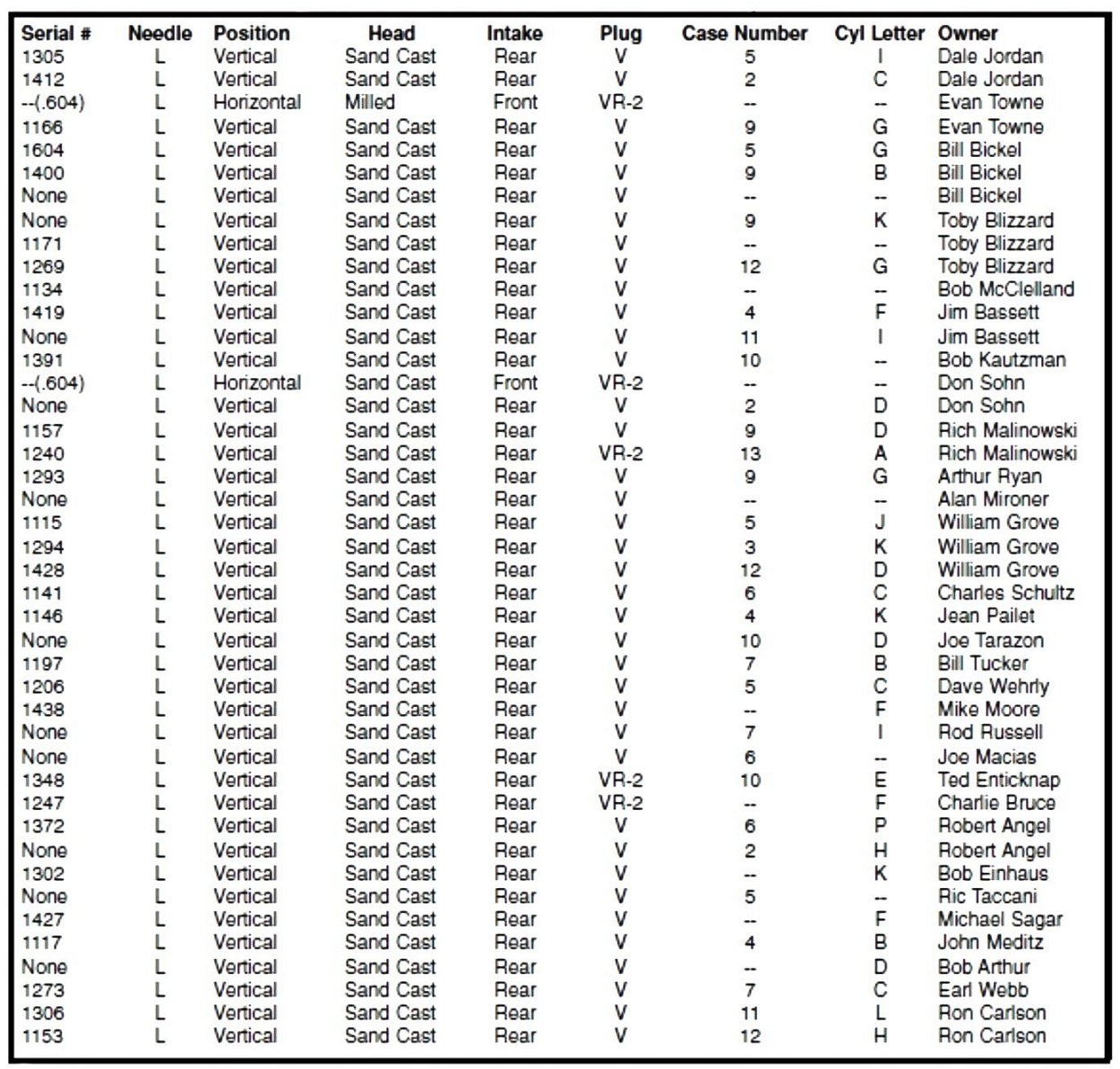

The Orr 60 prototypes ran OK but did not perform up to Fred’s expectations. As it stood, the engine looked like being just another general-purpose unit, of which there were already many excellent examples on the market. Fred formed the view that a complete redesign was required if the engine was to be put into production. It was also necessary to identify a specific target market niche which the engine could fill. The decision was soon taken to design an all-out racing engine of the type which had been pioneered during the pre-war years by Ray Snow of the Hornet company of Fresno, California. Almost all of the then-current large racing engines were manufactured and primarily distributed in the racing hotbed of California, so there appeared to be a market niche open to a quality racing engine produced in the Eastern United States. Recognizing that he lacked the production capacity to develop and manufacture model engines in commercial quantities, Fred went looking for a company that would assist with the engine’s development and produce the finished design for him. He eventually established a relationship with a firm called Modern Engineering Products Co. of Niles, Michigan. This company was owned by Paul Dreher, whose brother Merle was also involved in the business in the capacity of chief engineer. Niles was conveniently located in southern Michigan adjacent to the State border, only a very short distance to the north of South Bend, Merle Dreher was a fully qualified mechanical engineer with prior experience in the railroad industry gained while working for Fairbanks-Morse. Fred discussed his proposed model engine with Merle, saying that he wanted more power than his .60 cuin. FRV prototypes were able to deliver. The two men subsequently worked together on the design of the engine. Engines of .65 cuin. displacement were permitted in certain Class C competitions in America at the time. To take full advantage of the prevailing rules, the displacement of the new design was increased to .647 cuin. Disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction was incorporated, with a twin ball-race shaft and ultimately a third ball-race for the disc valve bearing. The result was one of the all-time classic model racing engines of the early post-WW2 era - the Orr Tornado 65. Once the design was finalized, the creation of the necessary tooling, jigs and fixtures to facilitate series production as well as the creation of a start-up inventory of castings required an investment of some $65,000 - a really significant sum in those days. Goes to prove the old adage that to make a small fortune from model engine manufacture, one needs to start with a large fortune! Once again, Fred’s well-heeled father was persuaded to step in to provide financial support for the project. Fred was evidently a talented self-promoter! Two distinct variants of the Orr Tornado 65 are known. There has been a rather widely-held perception that both of these were production units, but in reality the first variant was a prototype which was individually constructed in very small numbers and was never advertised. Dale Jordan’s previously-mentioned survey captured a total of some 45 examples of the engine, thus providing a considerable amount of data on the various configurations in which the engine appeared. What follows is a summary description of the two main variants, bearing in mind that certain details were almost certainly introduced successively rather than all at once. In addition, owners may have made their own modifications. Accordingly, examples which differ in detail from the following descriptions and illustrations may very well be encountered. The Orr Tornado 65 - Description of Variants

Bore and stroke of this model were 0.9375 in. (23.81 mm) apiece for a calculated displacement of 0.647 cuin. (10.60 cc). This may seem like a rather odd displacement to European readers accustomed to a 10 cc limit, but in fact at the time in question engines of up to 0.65 cuin. were allowed in certain American Class C competitions (and incidentally also in Australian Class D events). The Orr design team took full advantage of this, as did a number of others. The engine’s structural layout was very similar to that of the Hornet 60 which was the dominant racing engine at that time. The cylinder was a separate casting which was attached to the crankcase using four screws. This allowed it to be assembled with the exhaust stack on either side. The backplate was also a separate detachable sand-cast component which featured the intake venturi cast in unit. Two of the cylinder retention screws threaded into tapped holes in the top of the backplate, making it necessary to detach the cylinder if the backplate had to be removed for servicing. This early variant of the engine featured a horizontal needle valve. In keeping with most other large racing engines of the period, an open-frame automotive-style timer was employed in place of the enclosed unit featured on the earlier 60 FRV model.

As a result of these issues becoming apparent, very few of the above units were produced, and it was never advertised. Fred later recalled that most of those examples that were completed were given to local kids! The second and far better-known Orr Tornado model appeared in 1946, still featuring sand-cast components. This version was basically very similar to the earlier model apart from its use of a vertical needle valve and the addition of a ball-race to the bearing for the rear disc valve. In addition, the pattern for the crankcase was reconfigured to provide additional strength. The name Orr 65 was boldly cast in relief onto the bypass. The open-frame timer was retained.

An interesting point arising from a review of Dale's table is the fact that the cases and cylinders of most (but apparently not all) examples were marked with their own identification codes which were quite distinct from the serial numbers. Cylinders bore a letter code in the range A - K, while cases were numbered in the range 1 - 13. It seems likely that these markings indicated different casting or machining batches, but we can't be certain - they seem to be randomly distributed among the serial numbers. My friend Alistair Bostrom now owns listed engine no. 1134 (formerly owned by Bob McClelland) which bears the cylinder letter G and the case number 9, both of which are missing in Dale's table. I now own unlisted engine no. 1220, which displays the cylinder letter J and the case number 1 - another omission from the table. Bore and stroke were unchanged from the earlier version at 0.9375 in. (23.81 mm) apiece for an identical calculated displacement of 0.647 cuin. (10.60 cc). The engine weighed a reported 13.5 ounces (383 gm) minus ignition support equipment. My original example no. 1220 weighs in at a checked 14.3 ounces (405 gm), still commendably light for a big-bore spark ignition racing engine of the period. This highlights a significant difference in the design philosophy behind the Orr Tornado 65 by comparison with other contemporary big-bore racing engines. As of 1946, the majority of such engines were designed for use in tethered and rail-guided model racing cars, then very popular in the USA. In that application, weight was not really much of an issue since no power was required to generate lift. What mattered was peak power output and structural durability. By contrast, the Orr was clearly designed primarily for aircraft service, in which application weight was of far greater concern since power required to generate lift is not available to generate speed. This of course reflects the fact that Fred Orr was an aeromodeller first and last.

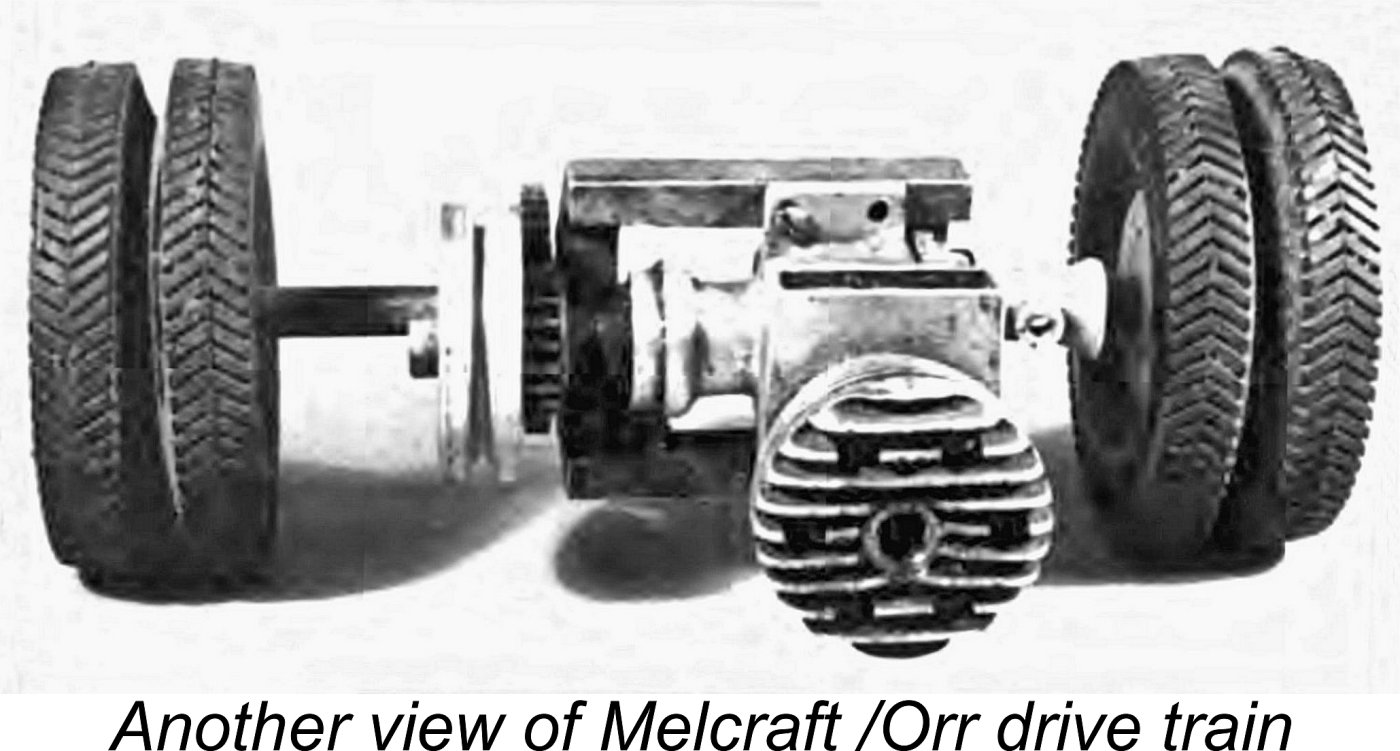

Interestingly enough, the Melcraft car appears to have been specifically designed around the Orr Tornado 65! It's possible that there may have been a relationship of some kind between the two Mels and their fellow Michigan-based model engine manufacturer Fred Orr. Alternatively, it may simply have been a case of using the locally-available product for convenience. Regardless, the design featured a horizontally-mounted motor which drove the wheels through spur gearing. A cast aluminium alloy pan was used, with a carved balsa-wood top which could be custom-finished by the owner.

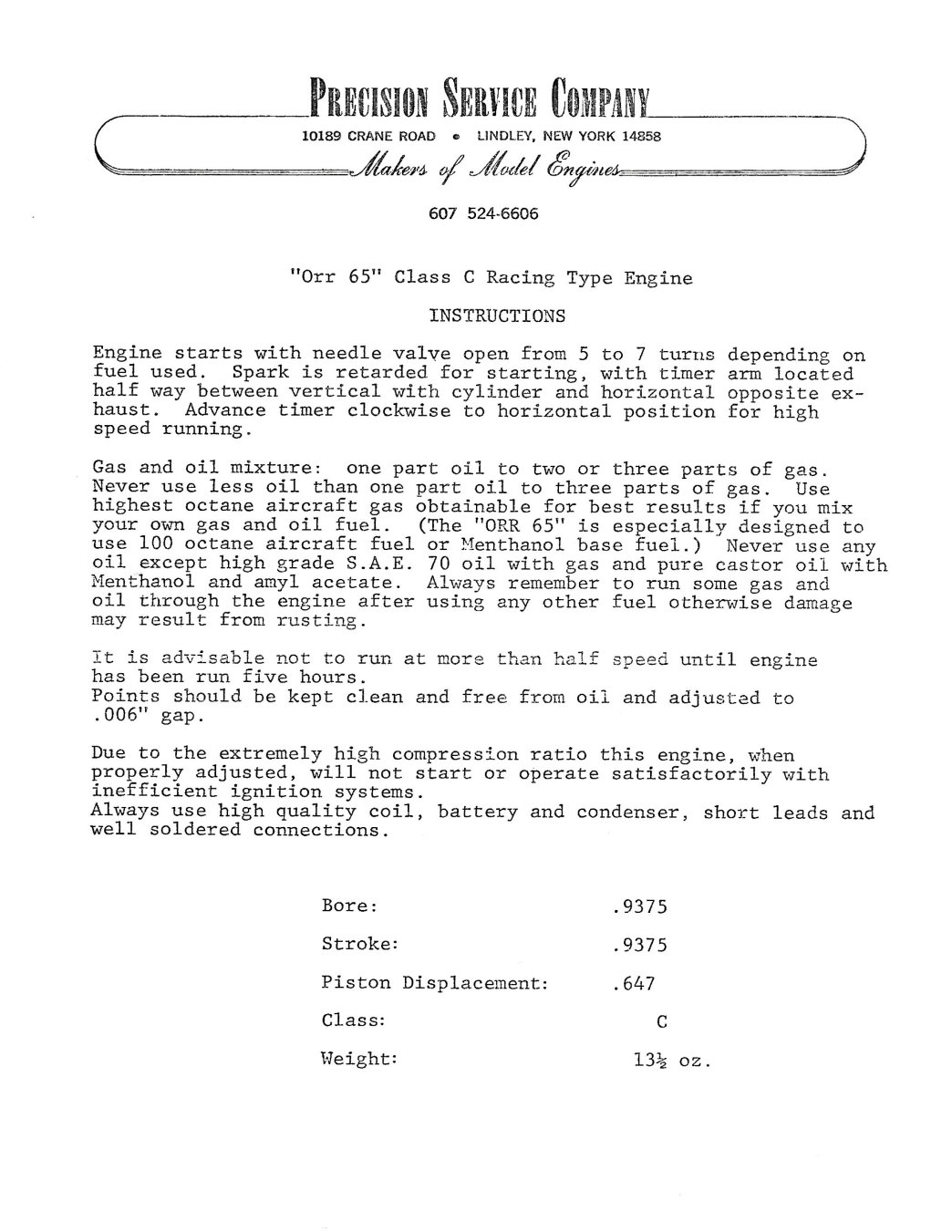

Returning now to the description of the Orr Tornado 65, the compression ratio was a very high 12½ to 1 - among the highest such ratios ever employed by any contemporary designer as far as I’m aware. Given that compression ratio, it comes as no surprise to learn that the Tornado was expressly designed to operate either on 100 octane aviation gasoline with SAE 70 oil or a methanol/castor oil blend with some added amyl acetate. By the end of 1947 that recommendation had been amended to include only the use of the methanol/castor brew. The recommended oil content was a minimum of 25%. All of the engines were apparently tested at the factory before shipment. A standard test airscrew was used, which the engines were expected to turn at 13,000 rpm. Those which failed to do so were further reworked until they met the required standard. The instruction sheet (see below) confirmed that all engines were "run in and tested" before shipment, but then went on to stated that a further 5 hour break-in period was required before the engine could be operated at full speed. If they were "run in", why was this necessary? Even if they weren't run in, this seems excessive to me - a well-fitted engine of this type should not need such a long break-in. However, there it is ……….. On the basis of his own tests, the manufacturer claimed an output of 0.85 BHP @ 13,500 rpm for this model. It has to be said that this is a perfectly believable claim given the engine’s specification. Moreover, it was a quite competitive level of performance by 1946/47 standards, prior to the mid 1947 arrival of the Dooling 61. With careful and well-directed tuning, this performance could doubtless have been improved upon to some degree. Marketing and Publicity

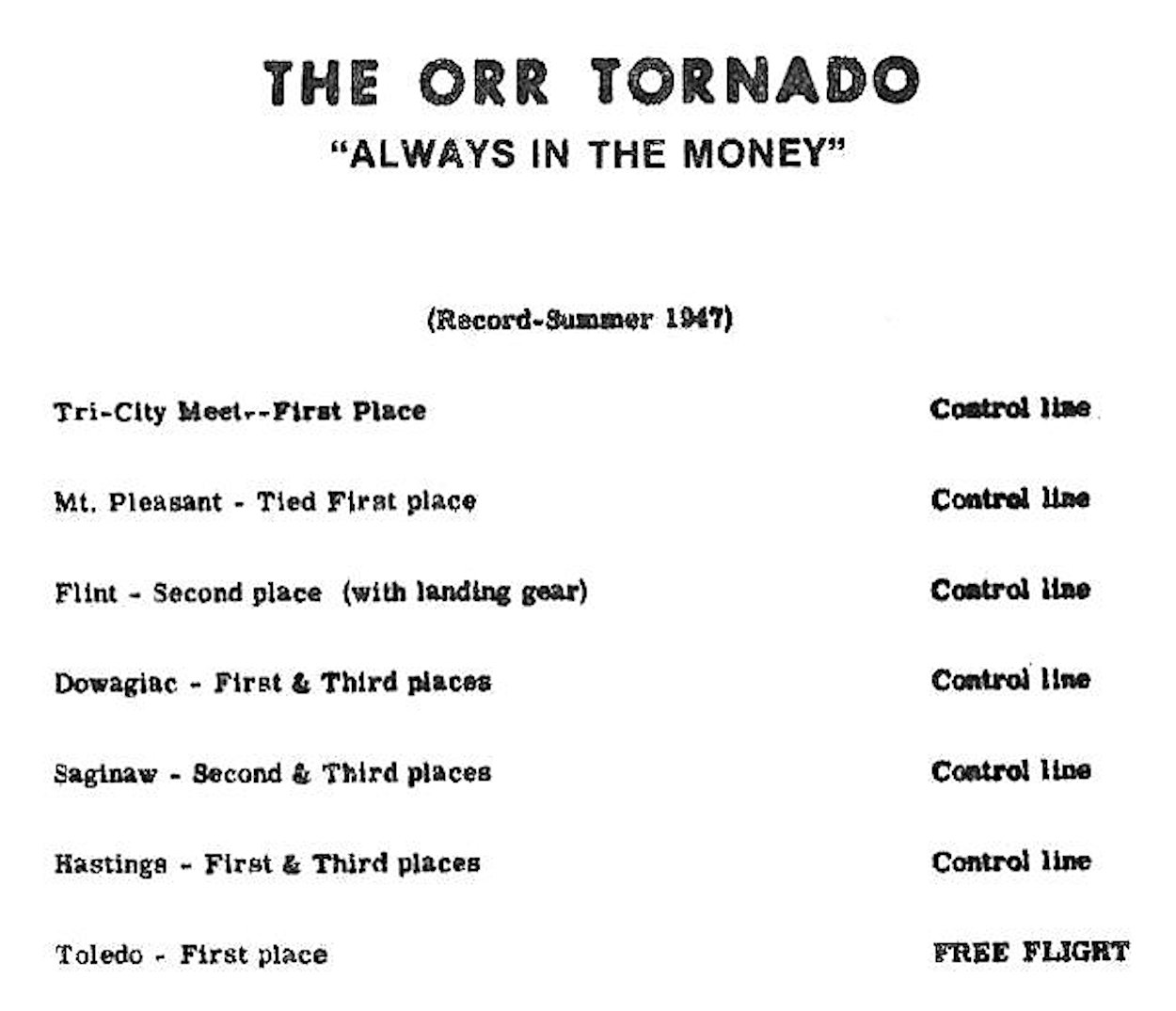

The advertisements identified the manufacturer as Orr Engines Inc. of 425 South Grand Avenue, Lansing, Michigan. This was actually the address of Fred Orr’s father. Since Lansing lies a considerable distance to the north-east of Niles, where the engines were actually made, this would appear to be a reflection of Orr Senior’s not unreasonable desire to maintain close oversight of his substantial investment in his son’s venture. According to his nephew Bob Orr, himself a modeller of considerable talent, Fred Orr was a master modeller whose creations reportedly put Bob’s own well-constructed efforts to shame. Fred drew upon these talents to put his money where his mouth was, promoting the Tornado by personally entering a number of contests using the engine in his own models and winning at least one of them. Fred kept close track of the engine’s competition successes both in his own hands and in those of others, as witness the attached results summary for the It's also noteworthy that the majority of the cited contest locations lie in the State of Michigan, with one contest apiece taking place in nearby Illinois and Ohio respectively. The inference to be drawn from this is that the engine found most of its purchasers in and immediately adjacent to its home State. Its geographic marketing reach thus appears to have been relatively limited despite the broader promotional efforts of its manufacturers. This did not prevent the Orr from attracting some attention from the contemporary national modelling media. Its first such appearance came with its inclusion in the article entitled “Latest Model Motors” by Edward G. Ingram which appeared in the April 1947 issue of “Model Airplane News”. Since the relevant portion of this article provides many details of the engine’s construction, it seems worth reproducing here in full, as follows: “Designed to operate on high octane aviation gasoline, outstanding features of the Orr 65 racing engine (a product of a Michigan manufacturer) include high power output to weight, the provision of a ball bearing rotary disc valve - an innovation in model engine design - and an alloy steel crankshaft supported on two ball bearings. The manufacturer states that the rating of 0.85 hp at 13,500 rpm was obtained through comparative tests with other engines, use of propellers of various pitches and a tachometer, and that additional data will be supplied when further tests are completed. The engine has a bare weight of 13½ ounces. Contributing to the high power output is the high compression ratio of 12½ to 1 and the provision of two rings on the aluminium alloy piston to minimize gas leakage and insure high compression. It is reported that after a four hour test at full power the engine showed no sign of failure or falling off in output. Like several other makes of model engines intended for use in racing cars and boats, as well as for model planes, sand castings are used extensively in the construction of the Orr 65, this method of fabrication being employed for the cylinder, cylinder head, crankcase and piston. While engines made from sand castings tend to be slightly heavier than those constructed from die-castings, the manufacturer of the Orr appears to have aimed at keeping the weight low through compact design, the crankcase in particular being unusually small for an engine that is somewhat larger in displacement than most Class C engines. Low engine weight is not so important in engines for model cars and boats where the main object is to attain maximum power to piston displacement, but it is a desirable characteristic for airplane engines when it can be achieved without loss of efficiency and reliability. One component of the Orr engine that is not sand-cast is the connecting rod, which is a 24S-T aluminum alloy forging with an Oilite bronze bearing mounted in the lower end. The cylinder, which is bolted to the crankcase, is supplied with a Meehanite iron liner. Both bore and stroke of the cylinder are 15/16 in., which makes the displacement .647 cu. in. The cylinder head is lapped to the cylinder to insure a good fit, and is attached with screws.”

At some point in 1947 a distribution agreement appears to have been reached with a firm called Precision Service Company of 10189 Crane Road, Lindley, New York. This company styled itself as “Makers of Model Engines”, although they certainly didn’t make the Orr! Their instruction sheet for the examples that they distributed (reproduction attached) was simply a re-print of the original Orr instruction leaflet, with their own letterhead added at the top. The engine was listed in the tables associated with the article entitled “Model Motors for 1948” by Edward G. Ingram which appeared in “Model Airplane News” for January 1948. The only design change reflected in those tables was a switch to 17S-T aluminum alloy for the forged conrod. The associated text read as follows: “An examination of one of the latest Orr 65 racing engines reveals excellent workmanship and good appearance. The important design features of this engine, which include a ball bearing rotary disc valve, were described in a past article, but it is hoped that some information about its performance can be furnished in the near future.” This is the last media reference to the Orr engines that I can discover. Despite the engine’s worthy qualities, it was of course competing against the “big name” West Coast brands such as Hornet and McCoy, offering no performance advantage over either of those models. And there was worse to come - the mid 1947 release of the Dooling 61 had set the entire model racing engine world on its ear by establishing a new performance standard which none of its competitors could match.

There is some confusion regarding the actual number of Orr Tornado 65 engines manufactured in total. The original plan had been to produce an initial run of 5,000 engines, but in the event this figure was never approached. Fred Orr later recalled that only some 200 or so examples were completed and tested at the Niles factory. Against this figure is the fact that the serial numbers for these engines started at 1000 and went up to a presently-known high of 1604, implying that at least 604 engines were in fact completed one way or another. To further confuse matters, a number of seemingly original units have also turned up bearing no serial numbers at all! The previously-mentioned survey by Dale Jordan captured some 45 original examples owned by various ECJ readers. The serial numbers for these engines ran from a low of 1115 up to the 1604 high figure. These include numbers in the 1100, 1200, 1300, 1400 and 1600 ranges, implying that the numerical sequence was continuous. If this reading is correct, the true number manufactured was somewhat over 600 examples. However, it’s entirely possible that by no means all of these engines were made at the Niles factory. The end of Orr production at that facility was by no means the end of the Orr story! The Aftermath

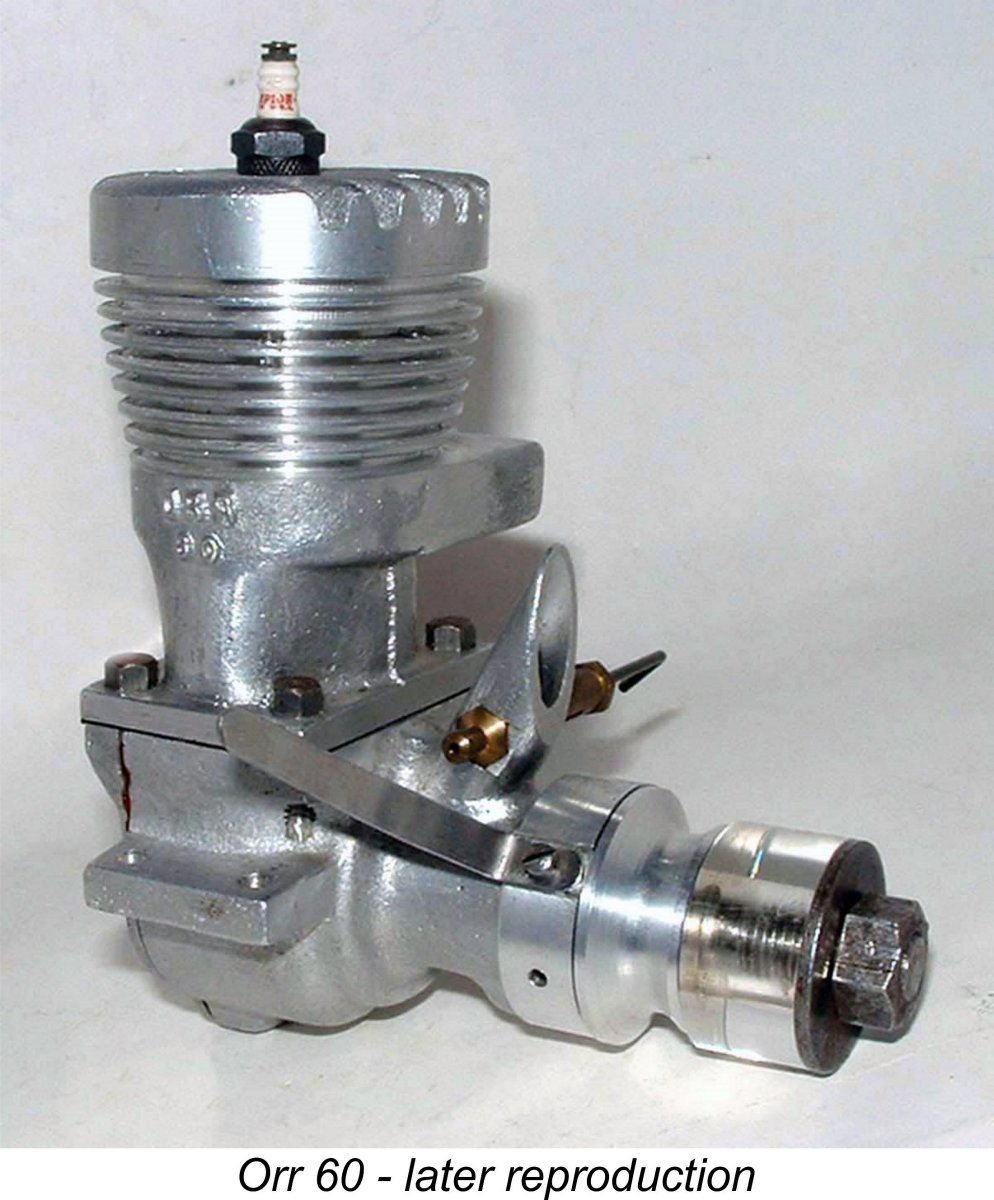

Fred Orr also ended up with a sizeable inventory of Tornado castings and components. When Fred’s nephew Bob Orr was released from military service, the two of them got together to construct a mobile machine shop which they drove to area model contests both to sell such examples of the Orr Tornado as they were able to complete from components on hand and to offer on-the-spot repair services for a range of makes, including the Orr. In this way, they were eventually able to pay off the original loan from Fred’s father, although there was very little left over for themselves afterwards. The examples of the Orr Tornado that bear no serial numbers may well be among those that were produced by Fred and Bob in the manner just described. Bob Orr stated that he never added serial numbers to these later engines, although some of the higher serial numbers may have been added by Fred without Bob’s knowledge. This could help to at least partially explain both the un-numbered examples and the apparent discrepancy between Fred’s recollection that only around 200 engines were completed at the Niles factory and the observed serial numbers. When it was found to be no longer possible to interest anyone in purchasing these engines (no collector scene back then!), Bob ended up storing a sizeable inventory of parts in his home. In the 1960’s, the remaining Orr stocks passed into the hands of Glen Warwashana. With the help of a machinist friend, Glen ended up producing and selling around 70 more Orr Tornado 65’s and even a few Orr Twins. After passing through a few more hands, the residue of the Orr project ended up in the hands of Art DeKalb. By this time all of the major castings were gone, but Art was able to utilize the facilities of a foundry at which he worked to produce a series of casting kits for the engine. Both Tornado 65 and 60 FRV casting sets were produced. The pattern for the 60 FRV model had been damaged, hence requiring repair. The restored pattern produced a flared intake venturi as opposed to the straight-sided component used on the original 60 prototypes. A combined total of around 150 sets of these casting sets were eventually sold. There's no way of knowing how many of these were actually completed by their purchasers or how they were marked. Fred Orr passed away on October 6th, 1979. The world had lost a master modeller and a dedicated model engine designer. The Larry Jenno Replicas

These near-replicas were serial-numbered in a J-xxx pattern to clearly distinguish them from the originals. However, the major and most obvious difference was the method used to produce the castings. The Jenno replica featured matte-finished investment castings as opposed to the sand-castings of the originals. The edges on all castings were much sharper, as one would expect with high-quality investment castings, of which Larry Jenno was a master. There’s no possibility of mistaking one type of casting for the other. The Jenno replica’s vertical needle valve had a round control knob as opposed to the original bent wire configuration. The cylinder fin profile was more sharply tapered, and the top of the cylinder head had a flatter profile. Otherwise, the engine was remarkably true to the original. I have one of these replicas available for future testing if I ever get around to it (see below). The Don Sohn Replicas

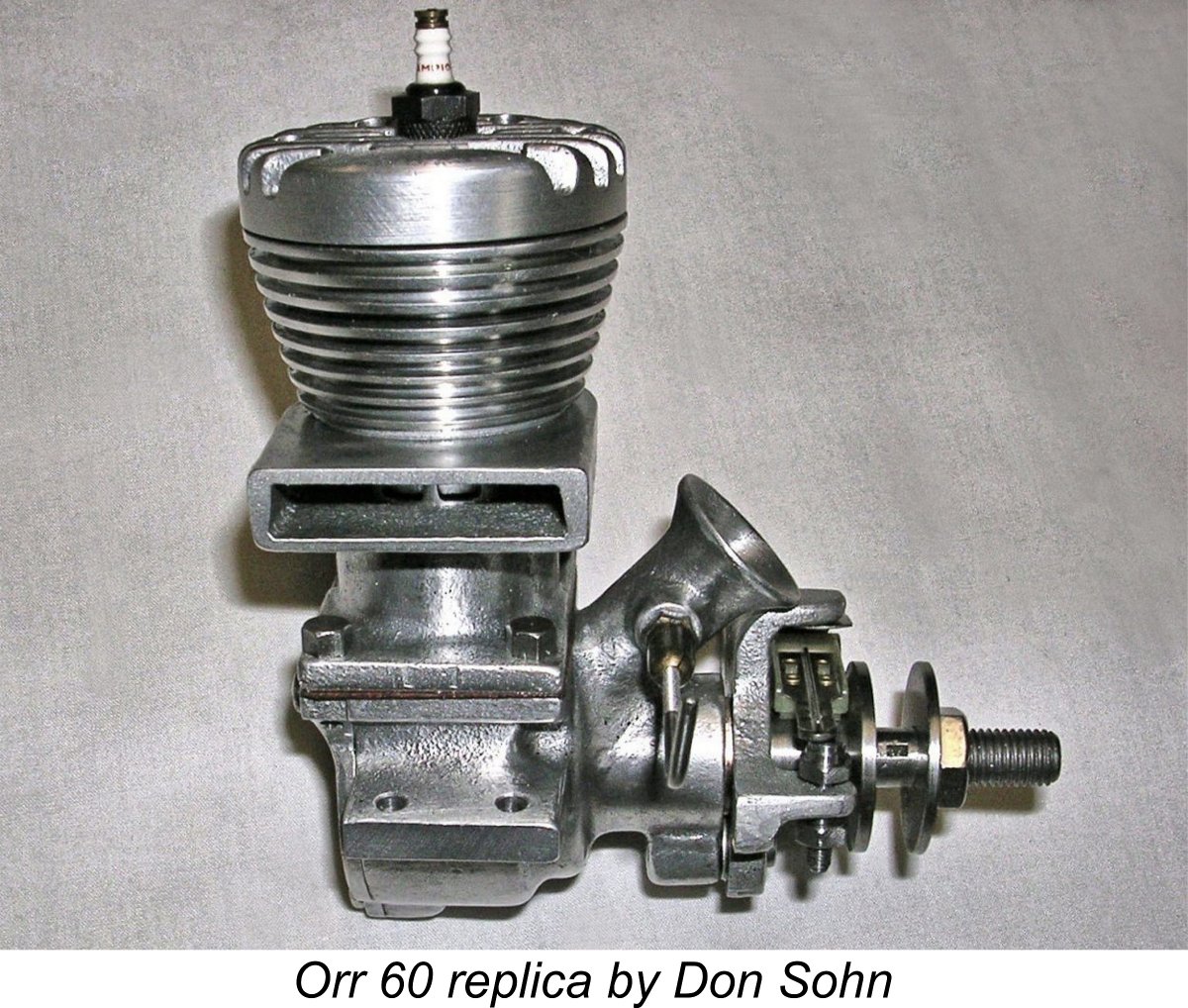

Don’s rendition of the RRV Orr 65 appears to have been very faithful to the original, right down to the use of sand-castings throughout. However, his version of the FRV Orr 60 differed significantly from the original in that the front of the main casting was amended to incorporate a flared intake venturi and an open-frame timer. In this, it followed the configuration established by Art DeKalb’s casting kits for the Orr 60. These engines were constructed to Don's usual very high standards. I have no doubt that they would run very well if anyone cared to give them a try. So how well did the Orr Tornado run in reality? A fair question, the answer to which will have to wait until the poitical turmoil which threatened us all at the time of writing has run its course. If I'm able to run a test in the future, I will add the results to this article. Conclusion I hope that you've enjoyed this look at one of the less prominent but nonetheless worthy racing engines of the late 1940's. The failure of the Orr 65 to gain a substantial foothold in the broader US racing scene of the period had far more to do with the engine's limited marketing reach than it did with any glaring deficiencies in the motor's design. A major contributing factor as time went by was also the manufacturer's lack of resources to continue to develop the engine in the face of the ever-improving opposition from other more prominent makers. Still, that doesn't alter the fact that this was a very well thought-out and finely executed model racing engine! So hats off to Fred Orr and his colleagues - they did Michigan proud!! _____________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published October 2022

|

| |

This article will add yet another chapter to my now long-running series of reviews of big-bore racing engines of the early post-WW2 era. This was indeed a "golden era" in the history of model racing engine development, and the legendary powerplants which resulted from the very fierce competition then prevailing in a variety of power modelling categories have always attracted my strong personal interest.

This article will add yet another chapter to my now long-running series of reviews of big-bore racing engines of the early post-WW2 era. This was indeed a "golden era" in the history of model racing engine development, and the legendary powerplants which resulted from the very fierce competition then prevailing in a variety of power modelling categories have always attracted my strong personal interest.

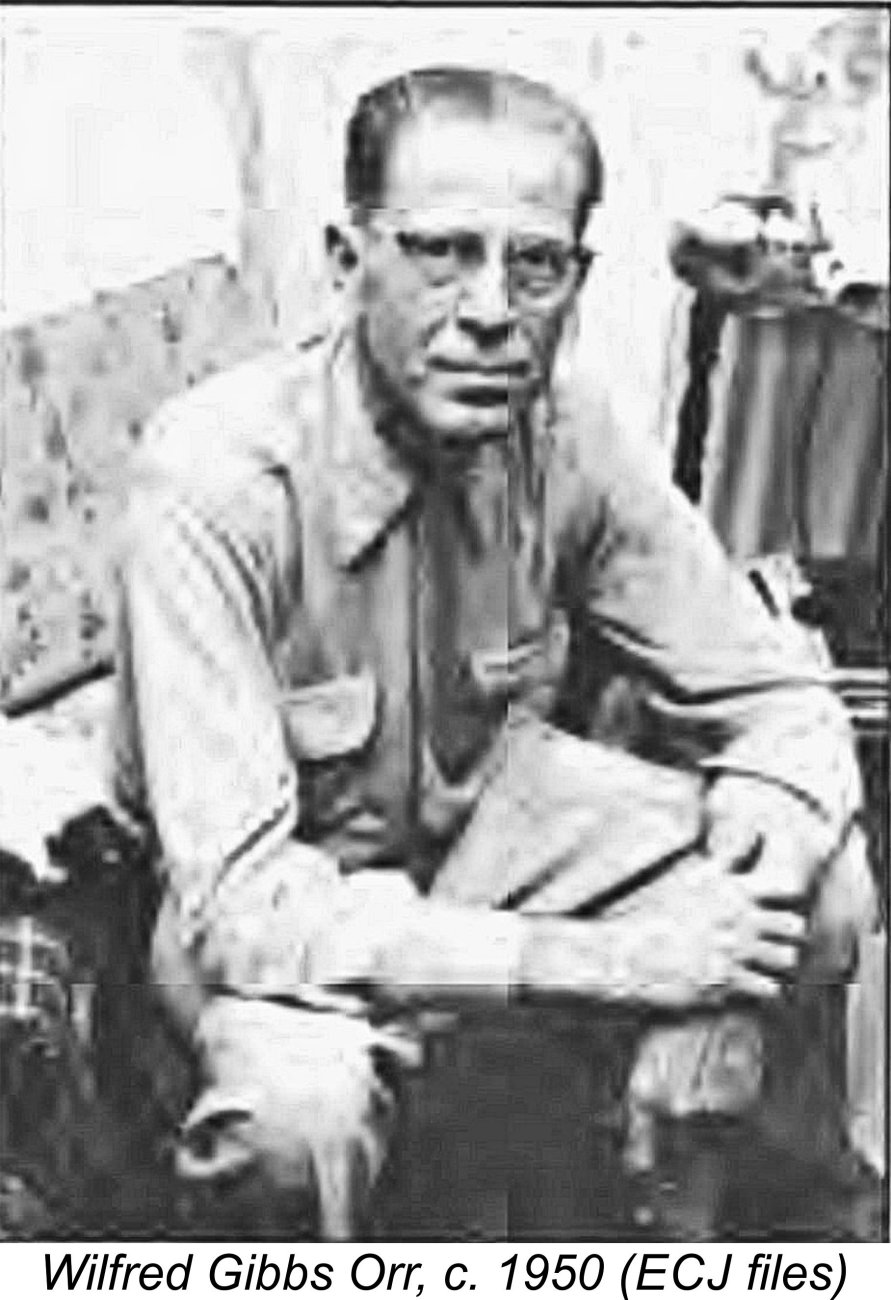

The Orr engines were the brainchild of a gentleman named Wilfred Gibbs Orr (always known as “Fred” as opposed to the more usual “Wilf”), who was the son of the founder and operator of the Wolverine Insurance Company of Lansing, Michigan, USA. Fred was a lifelong modeller of considerable ability and enthusiasm. Although he worked in other fields and moved around quite a bit, he always maintained a small hobby shop wherever he went, sometimes in his garage! These didn’t make him rich, but they kept him in close contact with the modelling hobby that he loved.

The Orr engines were the brainchild of a gentleman named Wilfred Gibbs Orr (always known as “Fred” as opposed to the more usual “Wilf”), who was the son of the founder and operator of the Wolverine Insurance Company of Lansing, Michigan, USA. Fred was a lifelong modeller of considerable ability and enthusiasm. Although he worked in other fields and moved around quite a bit, he always maintained a small hobby shop wherever he went, sometimes in his garage! These didn’t make him rich, but they kept him in close contact with the modelling hobby that he loved.

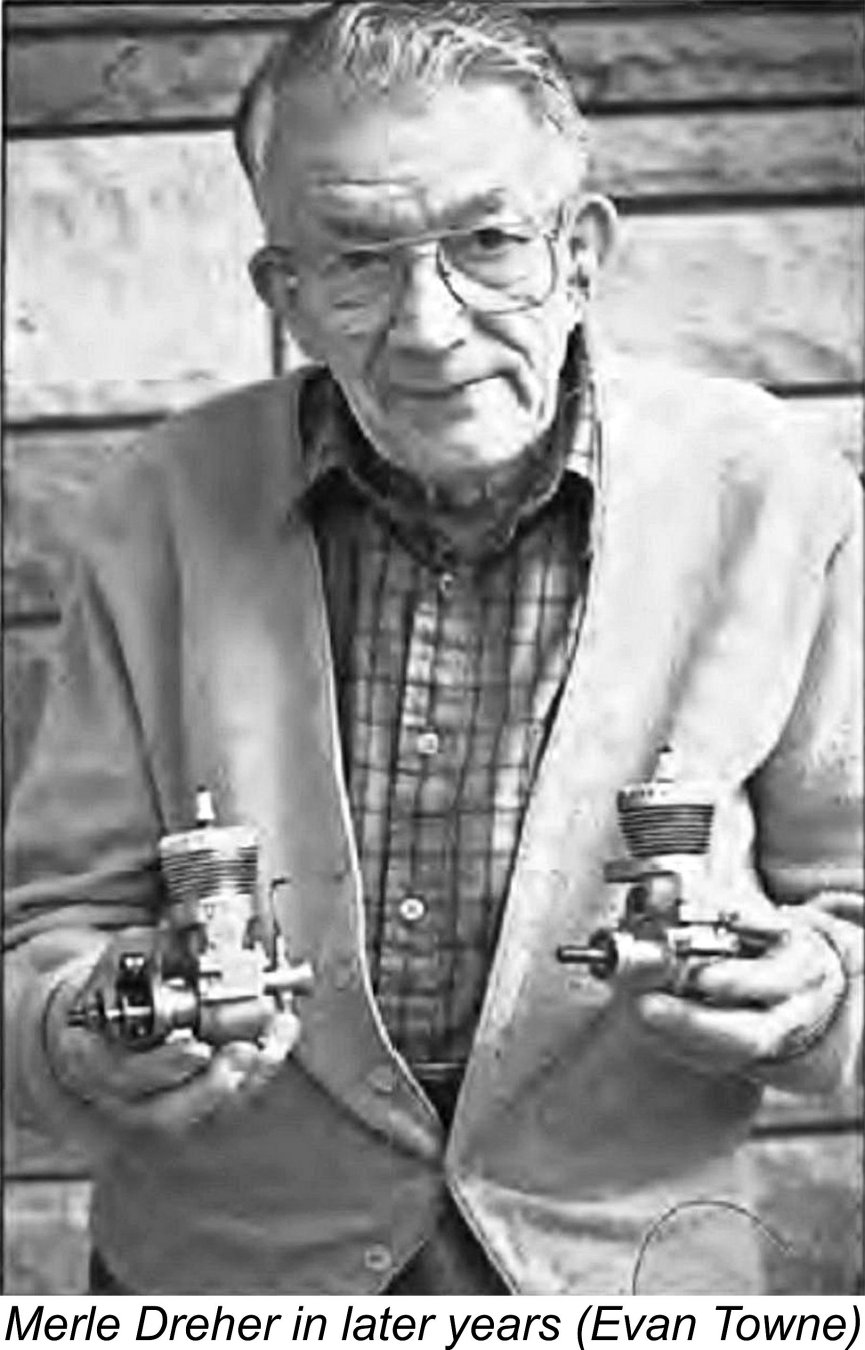

The first Orr Tornado model of late 1945 was a .647 cuin. (10.60 cc) disc rear rotary valve (RRV) twin ball-race spark ignition racing engine built around a sand-cast crankcase. The actual casting used was simply a modified version of the component used in the original .60 cuin. FRV prototype. A twin-ring light alloy piston was featured along with a forged alloy connecting rod having a bronze bushing at the big end. The cylinder liner was machined from Meehanite cast iron. The illustrated example from ECJ files is being held by Merle Dreher.

The first Orr Tornado model of late 1945 was a .647 cuin. (10.60 cc) disc rear rotary valve (RRV) twin ball-race spark ignition racing engine built around a sand-cast crankcase. The actual casting used was simply a modified version of the component used in the original .60 cuin. FRV prototype. A twin-ring light alloy piston was featured along with a forged alloy connecting rod having a bronze bushing at the big end. The cylinder liner was machined from Meehanite cast iron. The illustrated example from ECJ files is being held by Merle Dreher.  The horizontal needle valve was soon found to interfere with the mounting arrangements in a normal racing engine installation, although why this should be is not quite clear - many other large racing engines had horizontal needles. However, a far more serious issue was the fact that the .60-sized crankcases proved to be somewhat prone to stress-induced fatigue failures when applied to a more powerful .65 cuin. racing model. It was clear that the case had to be redesigned for greater strength.

The horizontal needle valve was soon found to interfere with the mounting arrangements in a normal racing engine installation, although why this should be is not quite clear - many other large racing engines had horizontal needles. However, a far more serious issue was the fact that the .60-sized crankcases proved to be somewhat prone to stress-induced fatigue failures when applied to a more powerful .65 cuin. racing model. It was clear that the case had to be redesigned for greater strength.  Both

Both That having been said, there is some evidence that the Orr did see service as a car engine. Over on the other side of the State of Michigan in Saginaw near Lake Huron, a pair of Mels (Mel Schmidt and Mel Bluemlein) had been producing the

That having been said, there is some evidence that the Orr did see service as a car engine. Over on the other side of the State of Michigan in Saginaw near Lake Huron, a pair of Mels (Mel Schmidt and Mel Bluemlein) had been producing the  The Melcraft car venture was not a success. In early 1947 the new model was taken to a major model show, complete with its Orr 65 powerplant, but no orders were received. The two Mels looked for a “sales handle” to excite prospective customers, coming up with a rather radical driving axle featuring dual tyres on each side. This was touted as a means of improving traction. However, even this didn’t raise enough sales interest to justify continued production - in fact, all that it seems to have produced among serious car buffs was a certain sense of amusement along with comments about truck racing! Only around 200-300 examples of the Melcraft car ended up being produced, not all of which were sold.

The Melcraft car venture was not a success. In early 1947 the new model was taken to a major model show, complete with its Orr 65 powerplant, but no orders were received. The two Mels looked for a “sales handle” to excite prospective customers, coming up with a rather radical driving axle featuring dual tyres on each side. This was touted as a means of improving traction. However, even this didn’t raise enough sales interest to justify continued production - in fact, all that it seems to have produced among serious car buffs was a certain sense of amusement along with comments about truck racing! Only around 200-300 examples of the Melcraft car ended up being produced, not all of which were sold. Although Fred Orr’s promotional budget was not large, the Orr Tornado 65 was promoted nationally, with advertisements appearing sporadically in the major modelling publications. The first national advertisement for the engine appeared in the October 1946 issue of “Model Airplane News” (MAN). The initial selling price was $37.50, but the prevailing competition quickly forced a reduction to $35 even to match the McCoy and Hornet offerings. The company adopted the slogan “Always in the Money” for the engine.

Although Fred Orr’s promotional budget was not large, the Orr Tornado 65 was promoted nationally, with advertisements appearing sporadically in the major modelling publications. The first national advertisement for the engine appeared in the October 1946 issue of “Model Airplane News” (MAN). The initial selling price was $37.50, but the prevailing competition quickly forced a reduction to $35 even to match the McCoy and Hornet offerings. The company adopted the slogan “Always in the Money” for the engine.

Production of the Orr 65 continued at some level through 1947, as witness the previously-cited summer 1947 contest results summary included with the late 1947 promotional literature associated with the engine. A string of top 3 places in both control line and free flight competitions were cited.

Production of the Orr 65 continued at some level through 1947, as witness the previously-cited summer 1947 contest results summary included with the late 1947 promotional literature associated with the engine. A string of top 3 places in both control line and free flight competitions were cited.

Advertisements for the Orr Tornado 65 continued to appear sporadically until at least April 1948, as witness the MAN placement reproduced earlier. However, it must surely have become clear by this time that in the absence of any further development the engine had no commercial future. At this stage, Paul Dreher wanted out, but Merle Dreher was convinced that some of the investment in the engine could be recovered by making up kits of finished parts and selling them unassembled and un-run for home assembly. In the end, Paul sold the remaining finished engines along with some finished castings, unfinished castings, components, jigs, fixtures and tooling for what Merle later recalled as being a “paltry” sum. Merle saved a few sets of components to allow him to make up a small handful of engines for family members. He is seen in later years in the attached image holding production and prototype examples of the Tornado.

Advertisements for the Orr Tornado 65 continued to appear sporadically until at least April 1948, as witness the MAN placement reproduced earlier. However, it must surely have become clear by this time that in the absence of any further development the engine had no commercial future. At this stage, Paul Dreher wanted out, but Merle Dreher was convinced that some of the investment in the engine could be recovered by making up kits of finished parts and selling them unassembled and un-run for home assembly. In the end, Paul sold the remaining finished engines along with some finished castings, unfinished castings, components, jigs, fixtures and tooling for what Merle later recalled as being a “paltry” sum. Merle saved a few sets of components to allow him to make up a small handful of engines for family members. He is seen in later years in the attached image holding production and prototype examples of the Tornado.  In 1994-95, Larry Jenno of Las Vegas, Nevada, produced just over 100 examples of a near-replica of the Orr Tornado 65 RRV production model. Initial deliveries took place in December 1994 and continued into 1995. The engines sold at the time for US$295.

In 1994-95, Larry Jenno of Las Vegas, Nevada, produced just over 100 examples of a near-replica of the Orr Tornado 65 RRV production model. Initial deliveries took place in December 1994 and continued into 1995. The engines sold at the time for US$295.  In 1997 the respected maker Don Sohn (a good friend of mine whose work has often appeared in these pages) produced a very few sand-cast replicas of both the Orr 65 and 60 models. Only around 5 examples of each model were produced.

In 1997 the respected maker Don Sohn (a good friend of mine whose work has often appeared in these pages) produced a very few sand-cast replicas of both the Orr 65 and 60 models. Only around 5 examples of each model were produced.