|

|

Now You See it ……….the E.P.C. Moth

The Moth is generally seen today as merely one of a number of early post-WW2 British model diesels from relatively obscure makers that made brief appearances on the market and disappeared without trace very quickly, leaving few surviving examples. As we’ll see, there were undoubtedly some very cogent reasons for the Moth’s failure to make any impression whatsoever on the British model engine market. However, the full story of its inception and marketing is a far more complex and interesting tale than is generally recognized. When I began this article, I honestly wasn't expecting it to contain all that much of substance. How wrong could I be .....?!? At the time of its appearance in 1950 the Moth was already out of date in design terms by at least three years - just one look tells you that! During the very dynamic model engine development period which followed WW2, that was a lot! Consequently, the Moth was a chronic under-performer by 1950 standards. As if that wasn’t enough, it also embodied several major design flaws which more or less guaranteed that it would be both unsatisfactory and short-lived in service. The wonder is not that it failed, but that it was ever released in the first place! All of this is really strange, because the manufacturers appear to have been more than capable. If they could produce the Moth to what was objectively a completely acceptable standard, it seems really surprising that Despite the Moth’s very out-dated design, the manufacturers were clearly preparing to produce the engine in quantity, because they went to the considerable trouble and expense of creating the necessary dies to facilitate the volume production of the high-quality pressure die-castings used in the engine’s construction. It turns out that they had a good reason for anticipating high production volumes. In order to understand how such expectations arose, we need to go back to the very beginning and trace the Moth's hitherto poorly documented origins. But before doing so, I wish to openly acknowledge the fact that it was only the kindness of my valued English friend and colleague Miles Patience that enabled me to write this article at all. If it hadn’t been for the effort that he put into the photographic documentation of an original example of the engine, I couldn’t have even got started on this article! I certainly wouldn't have my own reference example today without his help, for which I'm deeply grateful. I also wish to acknowledge the assistance rendered by my much-appreciated Aussie mates Maris Dislers and Gordon Beeby, who trolled the pages of their respective collections of old magazines in search of references, also coming up with several very helpful suggestions. Thanks, mates!! Now, on with the tale ............. Genesis of the Moth

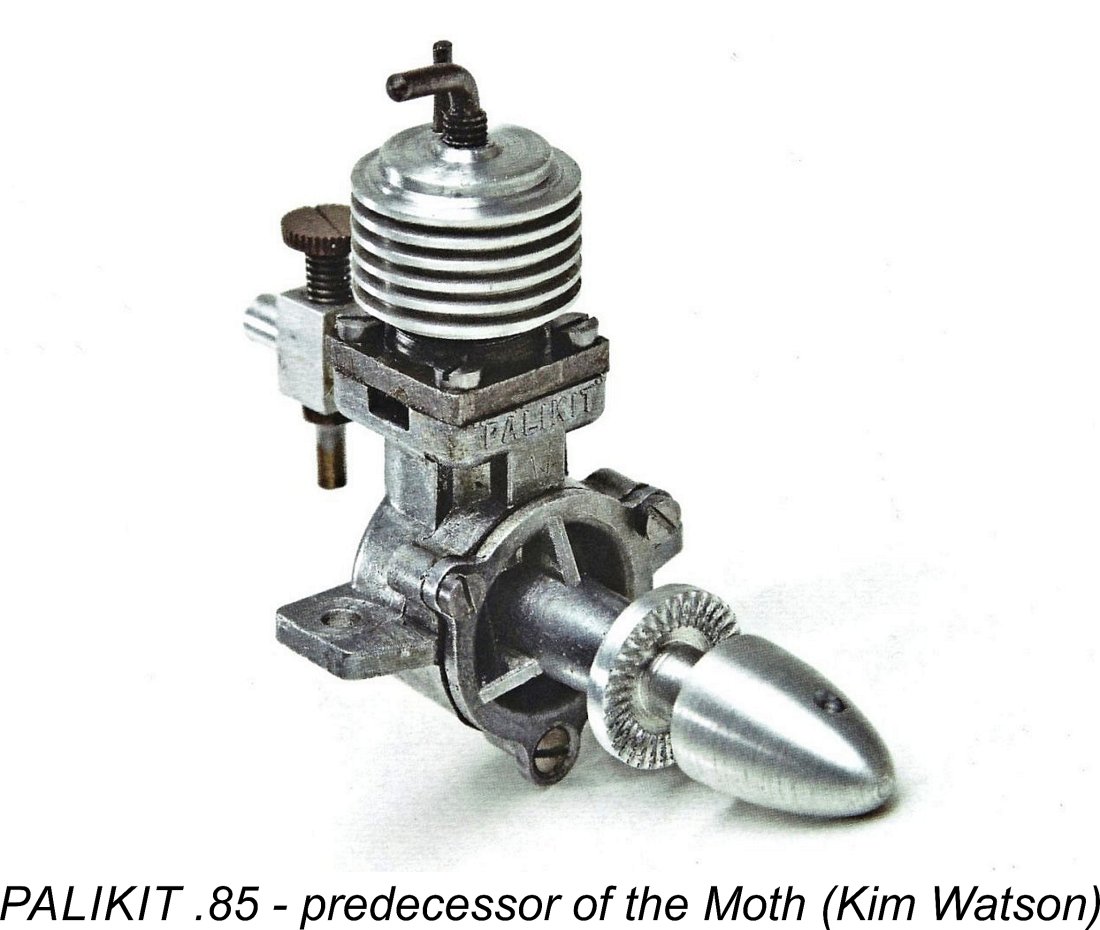

In 1994, John paid a visit to a mega-talented model engineer named Phil Cox who lived in Newark, not far to the north-east of Nottingham. The results of John's visit were written up in the June 1994 issue of MEW. The report focused on a small barstock diesel of 0.85 cc displacement constructed by Phil in 1949. It seems quite likely that when designing this engine, Phil Cox had some familiarity with the terms of British Patent number 633280, for which application had been made on February 14th, 1948 by Horace Herbert Woolley of Leicester. The originality of the concepts set out in this Patent is extremely questionable, since it appears in effect to describe the design of the Swiss-made Buchmann 0.6 cc diesel of 1944! However, it undoubtedly describes the main design features of the E.P.C Moth in some detail. Leicester is no great distance from either Nottingham or Newark, making it entirely possible that Phil Cox and Herbert Woolley were acquainted. My thanks to Gordon Beeby for drawing my attention to this Patent, which was finally issued to Woolley on December 12th, 1949. At the time when he built this little unit, Phil was acquainted with a gentleman named Sammy Diggle who lived in the village of Loudham lying between Nottingham and Newark. Diggle owned a company called Electronic Products Company (E.P.C.) having premises on Cameron Street in Nottingham. Sammy Diggle was evidently a model enthusiast, because he took a close interest in Phil Cox's new home-built 0.85 cc engine. This interest was prompted by the fact that Diggle had ambitions of entering the model engine manufacturing business himself on a commercial scale. He persuaded Phil to lend him the engine for study, a loan which apparently ended up extending to six months! It appears that the design of the E.P.C. Moth had its origins in this loan, although the engine as finally released differed in some key respects from Phil Cox's original. For one thing, the bore and stroke were very different - Phil's little diesel featured "square" internal geometry with nominal bore and stroke both being set at 13/32 in. (0.406 in. - 10.31 mm) for a displacement of 0.861 cc (0.0526 cuin.), while the Moth was a However, there are plenty of similarities. The cylinder design with its screw-on cooling jacket and square installation flange above the exhaust ports looks identical apart from the styling, while the crankcase style, bolt-on front housing and integral backplate are common to both models. The single hole in each mounting lug is also a shared feature, along with the sideport induction. The porting arrangements too appear to have been identical. The E.P.C. premises in Nottingham were located at an address given as Cameron Street, Haydn Road, Sherwood, Nottingham. Cameron Street still exists today (2020) - it’s a short side street leading north off Haydn Road, which is a significant east-west thoroughfare to the north of Nottingham City Centre in the Sherwood district. The address suggests that the company was located at the intersection of these two roads - it may even The reason for the evident expectation of high production figures at the outset may be found in the genesis of the project. It appears that before getting the production program underway, Sammy Diggle had made arrangements with another firm to supply the engines in large numbers for use in a now-forgotten line of plastic ready-to-fly control line models to be sold under the PALIKIT label. Hence at the outset, the Moth was not envisioned as a stand-alone product to be sold on the British model aero engine market in competition with the offerings of other more famous companies. Rather, it was designed and initially produced in fullfilment of a contract with the promoters of the PALIKIT range.

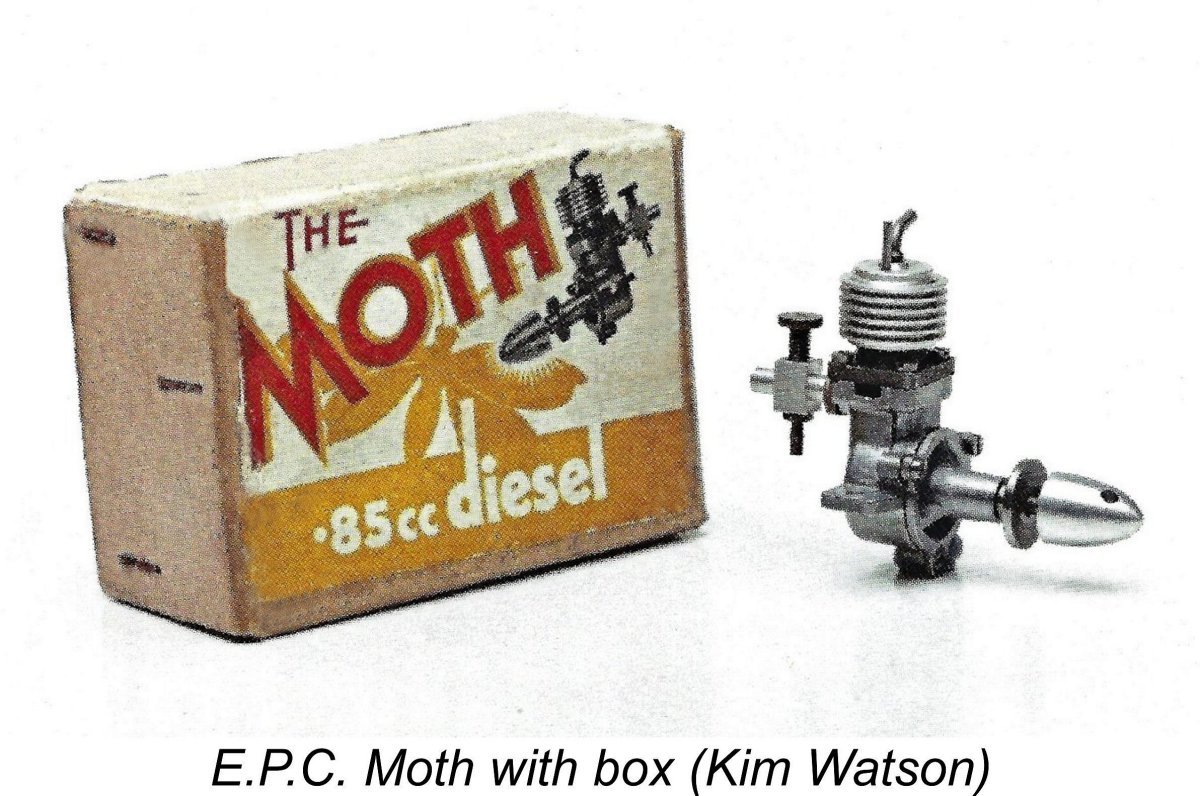

The original examples of the engine manufactured in early to mid 1950 had the name "PALIKIT" cast in relief onto the front face of the upper crankcase. The attached image by Kim Watson shows one of the very rare examples bearing this marking which has somehow survived. The PALIKIT name is clearly visible in the image. Unfortunately, it appears that this arrangement ran onto the rocks fairly quickly when it was found by sad experience that the engines didn't develop enough power to fly the models! Naturally, the PALIKIT promoters refused to accept any more engines from E.P.C., switching instead to the well-established and considerably more powerful E.D. Mk. I Bee as their power source of choice. Other PALIKIT models used Mills powerplants. The Challenger continued to appear in Gamages advertisements up to at least March 1951, albeit being offered by that time without an engine fitted. The buyer was free to choose his own powerlant, although the E.D. Bee continued to be recommended. This probably explains why surviving examples of the Challenger feature both Mills and E.D. engines. This left E.P.C. holding a stock of unused PALIKIT engines for which they now had no buyer. Their immediate response to this situation was to terminate production - it's quite evident that no more examples were produced after the severing of the PALIKIT connection, although some partially-assembled examples may have been completed "on the cheap".

Having done that, the company proceeded to attempt to sell the engines on their own account as E.P.C. Moths - a classic example of "badge engineering"! It is this rendition of the design that is generally recognized today - the PALIKIT connection has been more or less forgotten.

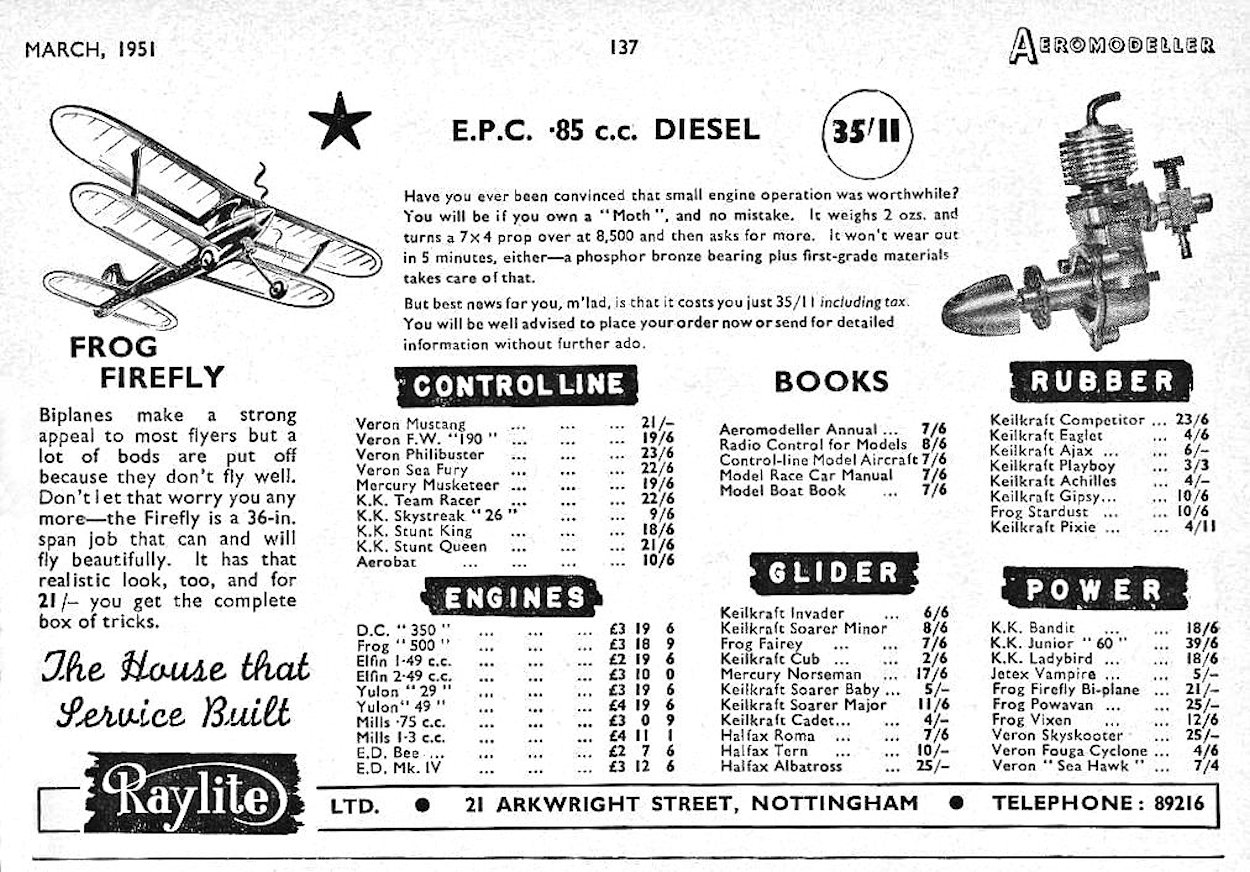

The first Raylite advertisement for the Moth appeared in the March 1951 issue of "Aeromodeller". It is reproduced here at the right. The Moth was prominently featured, complete with a photograph and a fairly detailed write-up. The Moth was also featured in the following month's April issue, as reproduced below at the left, but the heat had been turned down a little - the photograph was still on display, but the write-up was confined to a suggestion that the test of the engine in the February 1951 issue of "Aeromodeller" be consulted. More of that test below ...........

Reviewing the above advertising sequence, it's evident that Raylite made a sincere effort to promote the Moth but quickly found out the hard way that the engine failed to generate any interest from their customer base. It would appear that their efforts to sell off the engines had terminated as of mid 1951. As mentioned earlier, the Moth was also featured by the London-based firm of Ripmax, appearing in all of their advertisements from April through July 1951 inclusive. However, it appears that they met with no better success. As far as I'm aware, the July 1951 listing by Ripmax represented the Moth's final advertising appearance. In all probability, it was at that point that the rest of the unsold engines (of which there may have been quite a few) went into the E.P.C. scrap metal bins. There sems to be little doubt that many more examples were manufactured than have survived. It also appears certain that Sammy Diggle didn't come close to recouping his investment in the engine. The efforts of Raylite and Ripmax were not helped by the fact that the re-badged Moth failed to attract much attention from the contemporary British modelling media. It was included in Peter Chinn’s table of model diesel engines for 1948/1951 which appeared in the May 1951 issue of “Model Aircraft”, although it was not mentioned in Chinn’s accompanying text. As far as we can ascertain, At the time of Sparey's test, the Moth was offered at the remarkably low price of only £1 15s 11d (£1.80), making it not only the lowest-priced engine then on the British market but one of the lowest-priced British engines ever. To me, there has never been any doubt that this was an artificially low figure as opposed to one based on a realistic expectation of profitable production at the standard of quality displayed. I've always found it impossible to imagine anyone envisioning making money on this engine at such a price. Of course, now that we've documented the full circumstances surrounding the genesis of the engine, the explanation is readily elucidated. When the contract with the PALIKIT manufacturers was terminated on the basis of the engine's failure to perform at the required standard, E.P.C was left holding a batch of out-dated and under-performing PALIKIT engines for which no buyer was now in place. It's surely obvious that production of further examples of the engine would have been terminated immediately, although some partially-built examples may have been completed. To complicate the situation, a totally unconnected factor had now entered the picture. This was the onset of the Korean War in June 1950. Britain played a significant military role in this conflict, which was to last until July 1953. This British involvement led to the issuance of war-related Government contracts to a number of suitably qualified technical firms. E.P.C. was reportedly among the firms favoured with such contracts, accordingly finding its production capacity fully absorbed by the renewed military contract work which came its way. There was thus neither time nor incentive for any further model engine production. Despite these changed circumstances, E.P.C. management naturally wished to liquidate as much as possible of their existing inventory of completed model engines and components. They attempted to do so by removing the PALIKIT identification and enlisting the help of Raylite and Ripmax in offering the re-badged engines as E.P.C. Moths at fire-sale liquidation prices. Any recovery of tied-up capital was surely better than none ............ Unfortunately, low price alone was clearly insufficient to overcome the other sales impediments with which the poor little engine was saddled. It's extremely doubtful that many examples were actually sold - a significant proportion of the remaining stocks probably ended up going into the scrap metal bin.

As a result, until very recently I had never encountered an example of this engine in decades of looking. In fact, I’d never even been in touch with anyone who owned an original example at the time, although I did have contact with several former owners. This changed when I heard from Miles Patience that among the engines left by his late father Mike there was a cosmetically excellent original example of the Moth which had formerly been owned for a time by Miles himself. Miles was kind enough to send me some very informative images, which got me well started on writing this article. I was subsequently able to purchase the engine from Miles’ mother, with Miles' blessing and assistance. The ownership history of this particular example is known for some time previously. It first surfaced as part of the Doug Walton collection, although it’s not known when or from whom Doug obtained it. The engine then spent some time with Eric Offen before being acquired by Miles. He later passed it along to his late father Mike, from whose collection it has now come to me. Now, having set the scene, let’s take a look at this very elusive little powerplant. Description

When confronted with an actual example of the Moth for the first time, the first real surprise is to notice how small the engine is for its displacement. The photographs of the engine which are typically published fail to convey this impression because they lack any basis for a realistic estimation of size, generally showing the engine on its own at considerably more than life-size. As the accompanying image will confirm, the Moth is somewhat dwarfed by the smaller-displacement Mills .75! It must be one of the smallest ever engines of its displacement. Looking at it, you'd take it for a 0.5 cc model!

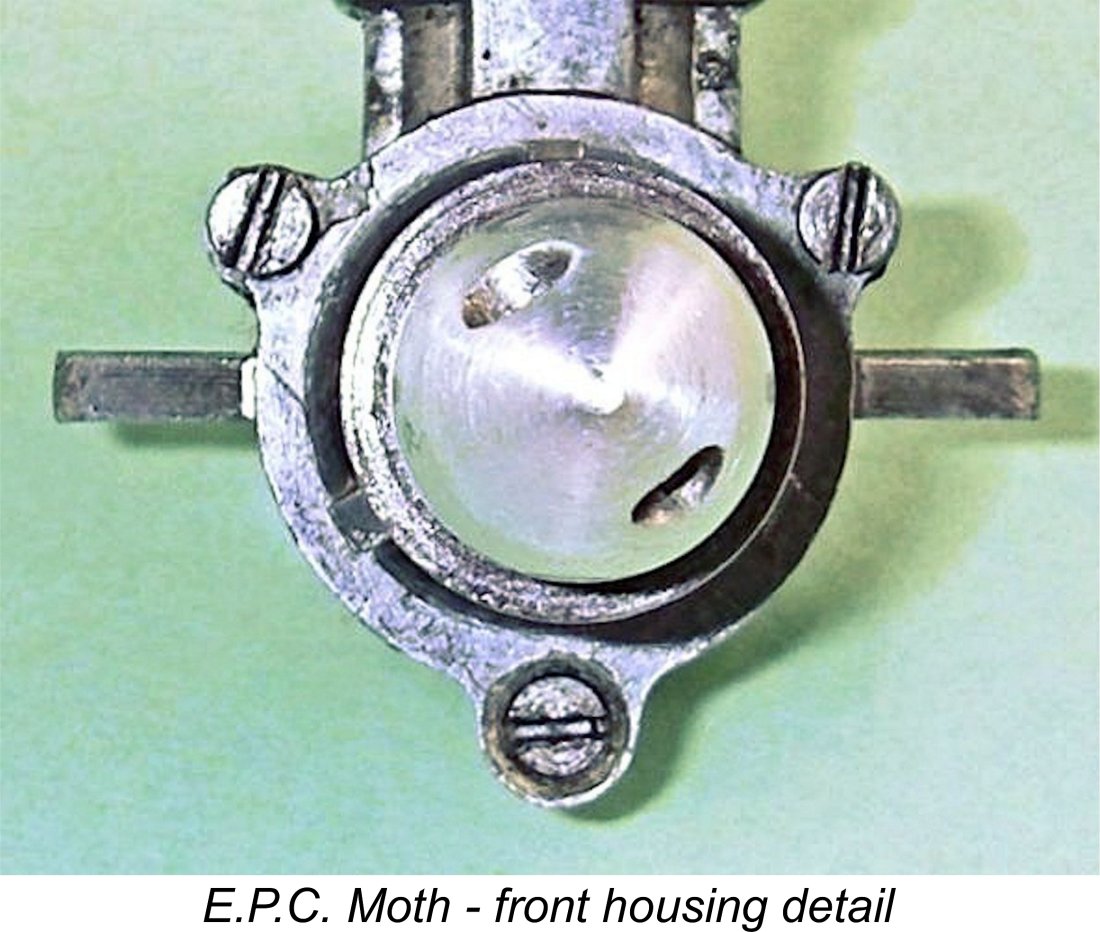

An interesting feature of the front housing is the fact that the lowest of the three "mouse-ear" eyelets for the assembly screws is of considerably larger diameter than the upper two. It is also countersunk and provided with a matching countersink-headed machine screw. As will become apparent, the front housing must be fitted in the correct orientation for the engine to go together properly, and this appears to me to be one way in which the designer ensured that it was correctly fitted. Both Lawrence Sparey's previously-illustrated test engine and the example featured in Raylite's advertising were similarly configured, confirming that this was a standard feature of the Moth. The smoothly finished surface of the front of the cylinder mounting flange at the top of the crankcase casting bears witness to the care with which the original PALIKIT identification was removed. The traces of the removal are clearly visible upon close inspection, but they have been very effectively smoothed over, probably with fine oiled emery paper backed up An interesting observation is the fact that the rear of the main casting bears the inscription “BRIT. PAT No. 633280” along with the “MADE IN ENGLAND” designation. This information is cast in relief onto the rear face of the integral backplate, thus being formed by the die. This of course is none other than the previously-mentioned Patent issued to Herbert Woolley in 1949. The cylinder is very similar to that used in the Mills sideport engines. It is basically of tubular form with a substantial square flange just above exhaust port level. The cylinder is secured to the crankcase using four machine screws which pass through holes drilled through the flange at the corners to engage with tapped holes in the upper crankcase deck, again just like the Mills. The standard of machining displayed in the cylinder is very high, as it generally is throughout the engine.

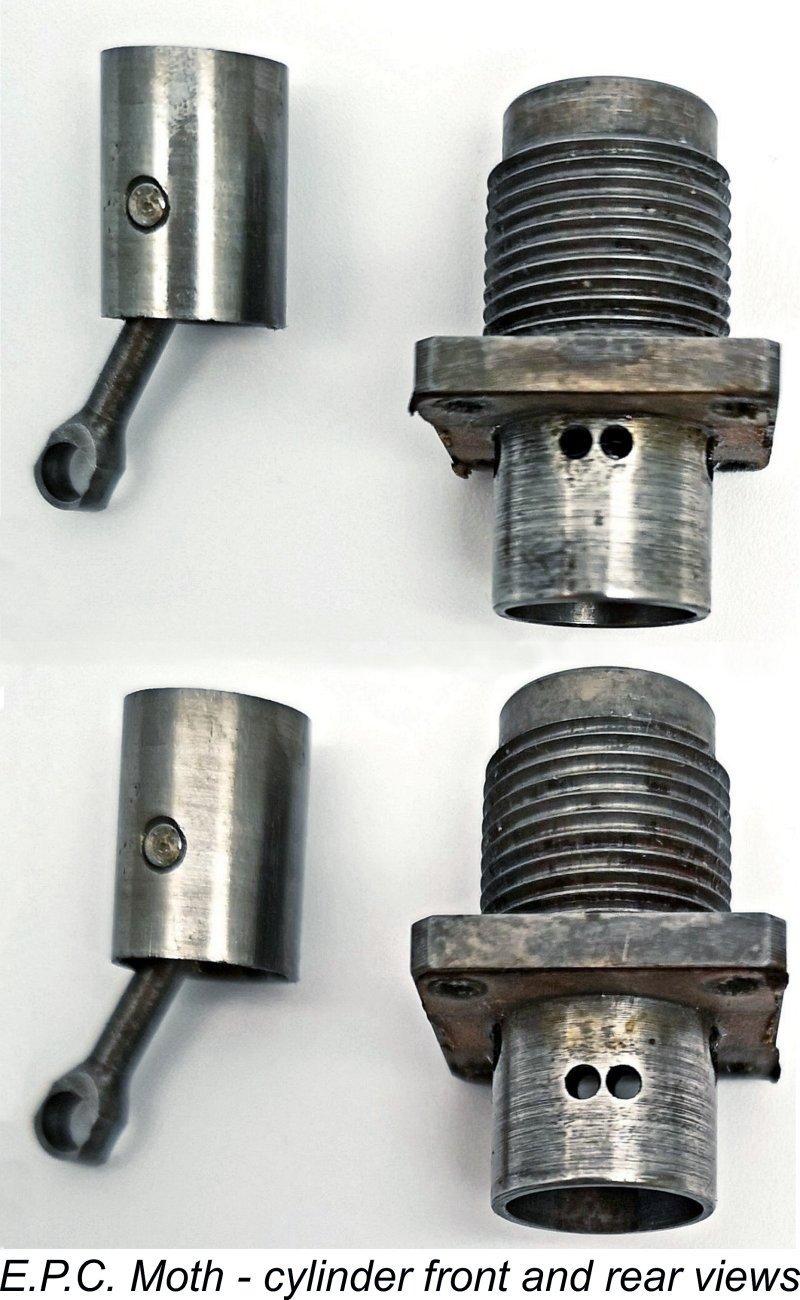

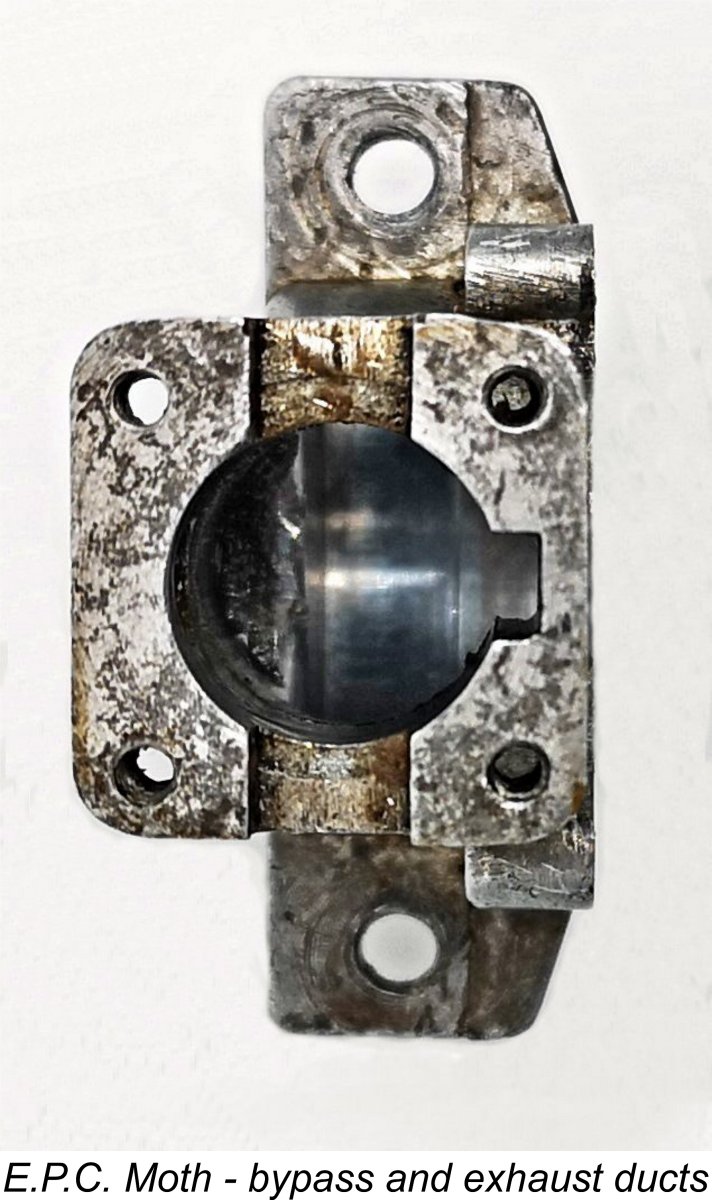

The upper portion of the cylinder is externally threaded to accommodate a cleanly-machined finned screw-on cooling jacket made of light alloy. This accommodates a very basic compression screw formed from a partially threaded bent length of steel rod. A stop pin is inserted into the cylinder head to limit the available range of compression adjustment. The cylinder’s lower portion is a firm push-fit into its installation bore at the top of the crankcase. Because the gasket under the cylinder installation flange is located above the cylinder ports, the crankcase seal is entirely dependent on the closeness of the fit between the lower cylinder and its installation bore in the crankcase. This was a not uncommon design feature in the late 1940’s. The Moth passes this criterion with flying colours. Cylinder porting is about as simple as it could get. Induction and transfer ports are formed as two pairs of drilled holes located fore and aft at appropriate elevations, again exactly like the Mills engines. Two pairs of drilled exhaust ports are provided, one pair on each side. The transfer ports overlap the exhausts almost completely.

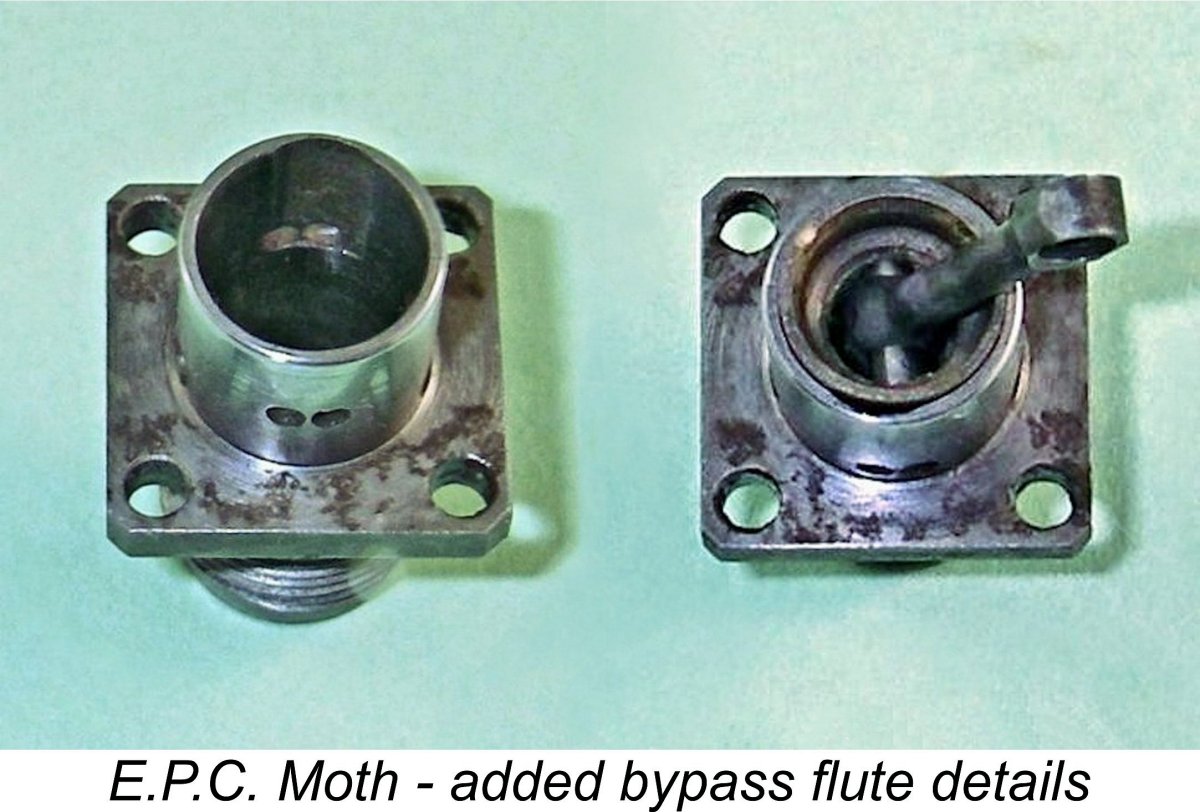

Since the cylinder is hardened steel, this feature was clearly created by grinding. Whoever carried out this work, it required great care and skill since there's very little cylinder wall thickness to play with. That said, the flute in my example was created a little off-line compared to the drilled transfer ports. This suggests that it was very much an afterthought carried out in an "eyeball" setup. However, it is very uniformly contoured to a very precise and consistent depth. It certainly doesn't look like a typical owner's hand-held modification.

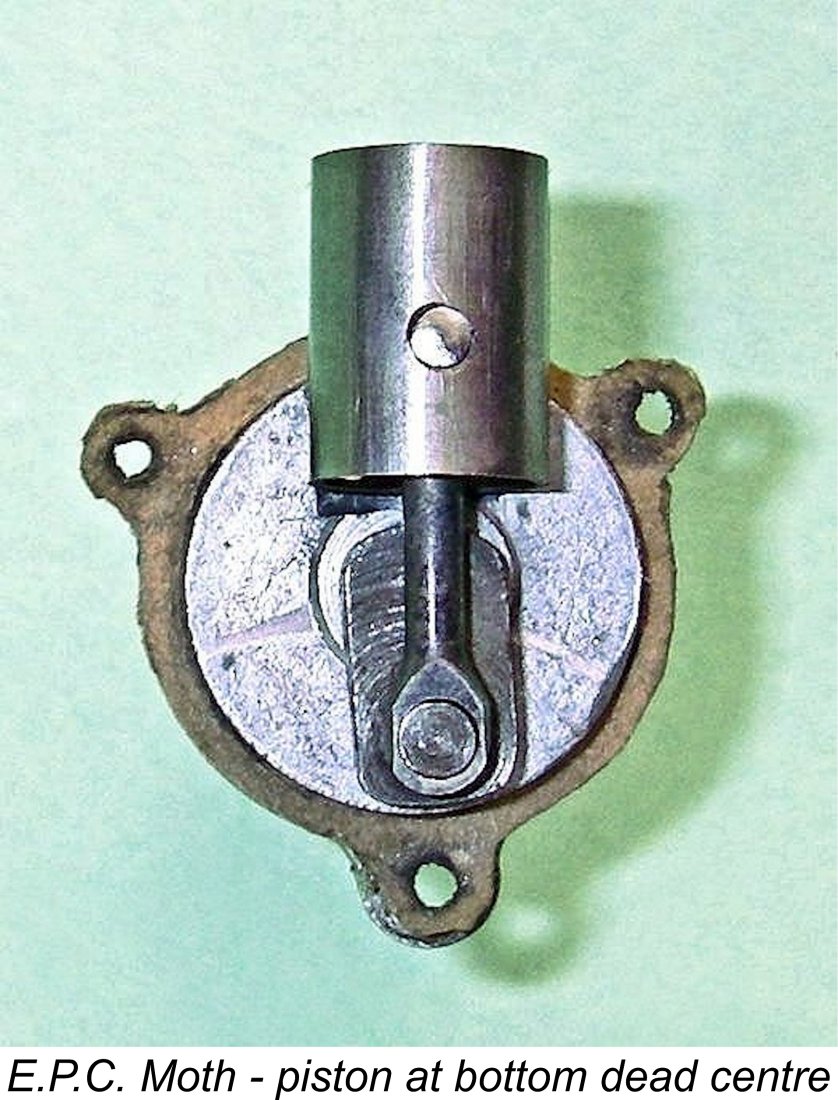

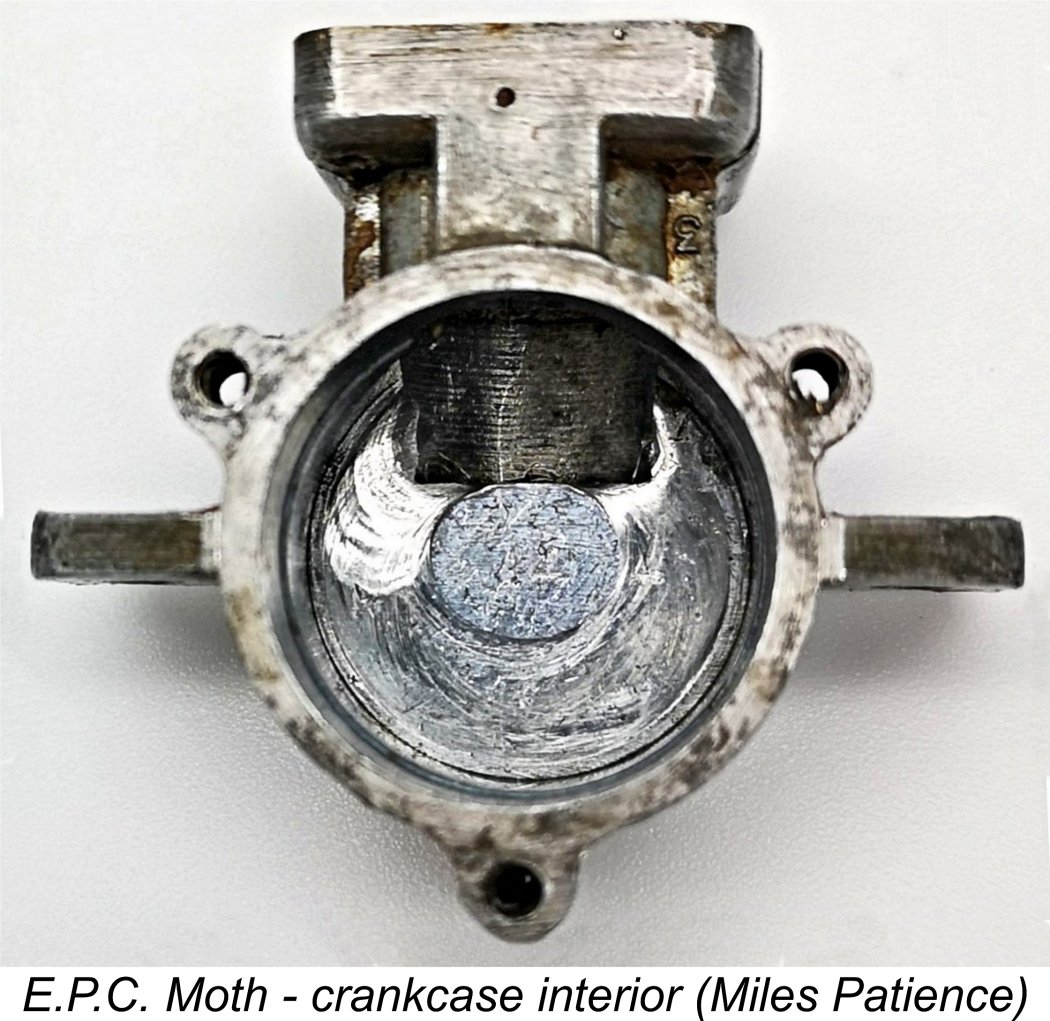

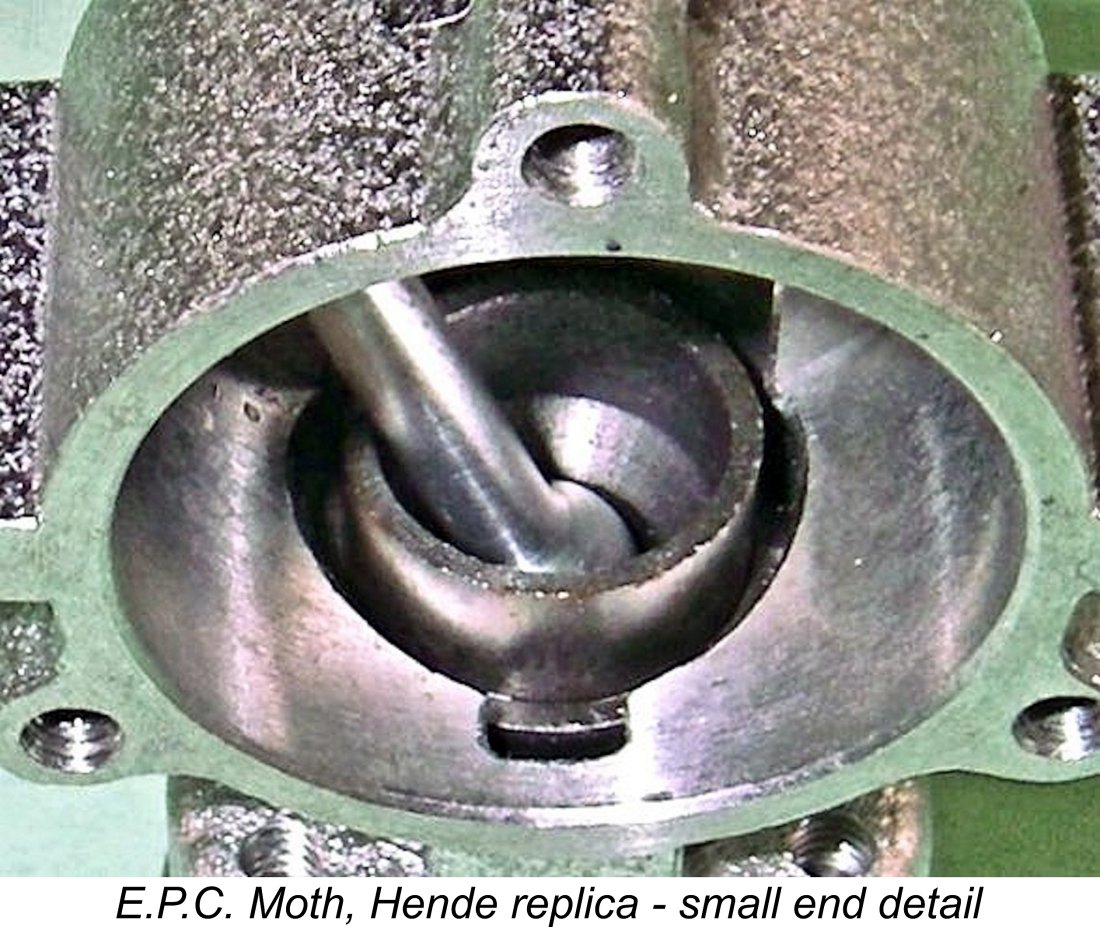

As originally designed, in the absence of the seemingly added-on bypass flute, the twin transfer ports are supplied by a bypass passage formed in the inner crankcase wall at the front. As previously noted, they overlap the exhaust almost completely. Unlike the Mills engines, there is no step in the piston crown. The exhaust ports discharge through a pair of channels formed in the upper crankcase deck, one on each side. The twin induction ports are supplied from an internally threaded boss which accommodates the intake venturi. Both piston and contra-piston are very nicely made out of hardened steel. The contra-piston appears to be perfectly fitted. The working piston fit is a little on the slack side, as it has to be with a steel-in-steel combination if nipping up when hot is to be avoided. However, there appears to be ample compression for starting and running. The very well-machined and unusually short connecting rod is made of mild steel which is case-hardened following machining. Such rods have a tendency to cause undue wear on their gudgeon pins and crankpins - a suitable high-strength light alloy is a superior choice, especially if bronze bushings can be fitted into the bearings. Other issues with the rod design will be discussed below in their place. Moving on downwards, we get to the strangest design feature incorporated into the Moth. This is the crankshaft, which not only lacks any form of counterbalance but also lacks so much as a crankdisc! The crankpin is carried by a simple throw in the form of a rectangular-section crank arm.

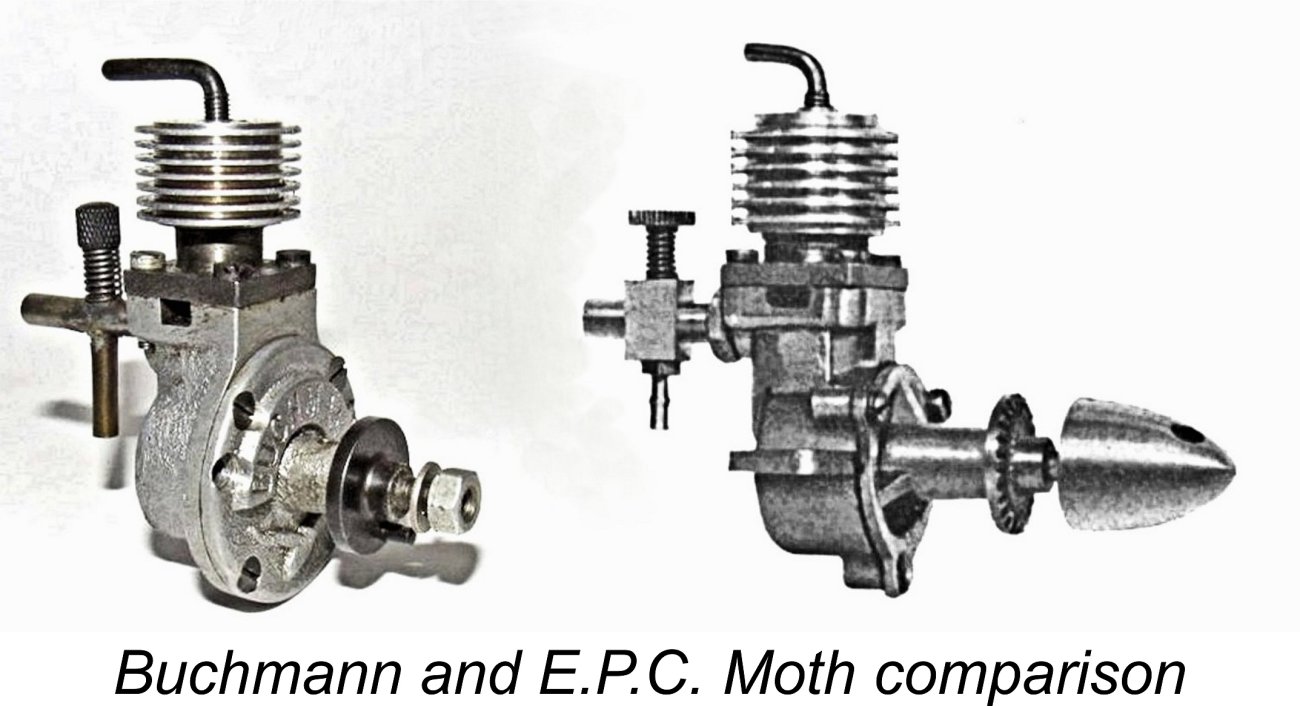

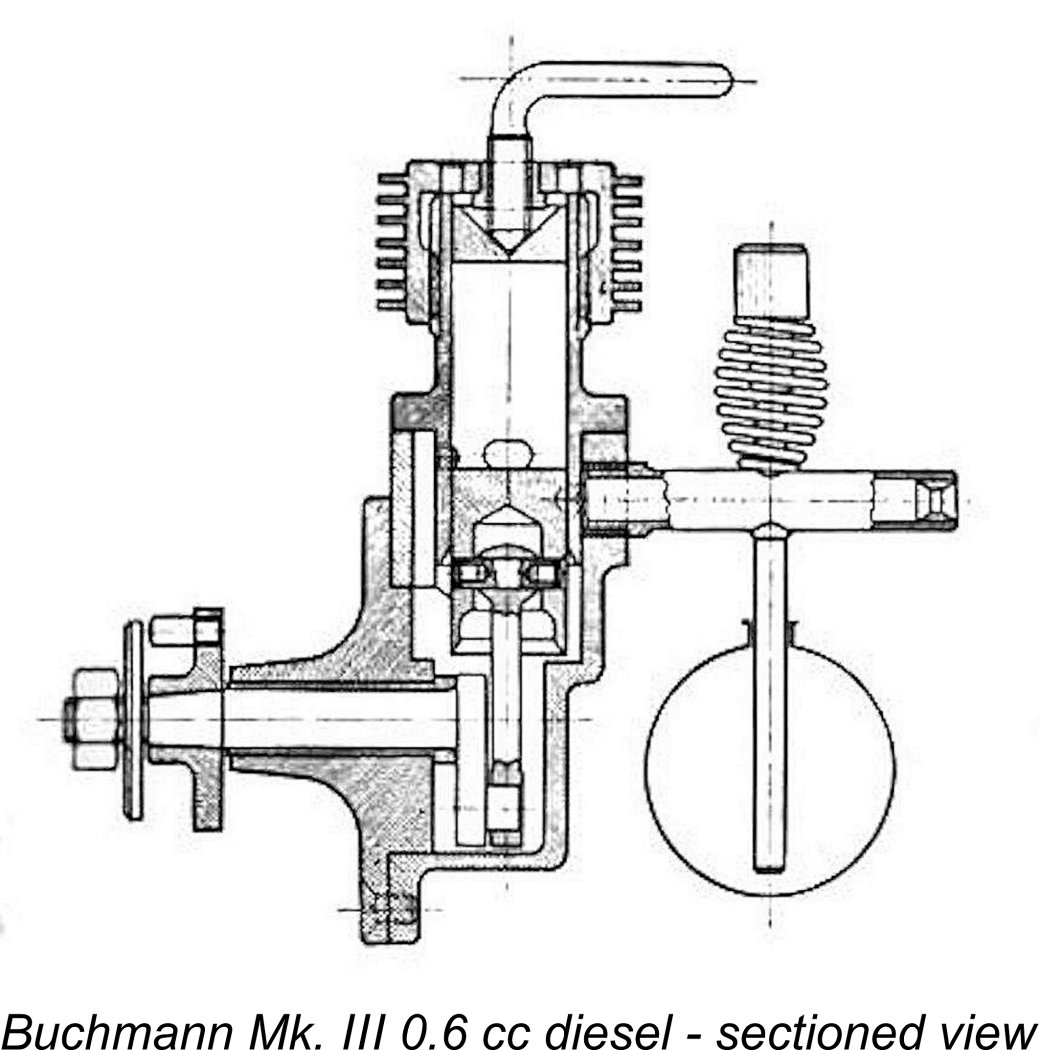

This highly unusual feature is a major factor supporting Maris Dislers’ previously-voiced suspicion that the design of the PALIKIT .85 and its E.P.C. Moth successor were strongly influenced by that of the earlier Swiss-made 0.6 cc Buchmann Mk. III diesel. It’s certainly true that the design and style of the cylinder, cooling jacket, comp screw and upper crankcase are all highly suggestive of Buchmann influence, as the comparative view seen below at the left should confirm. However, the real kicker is the Buchmann’s crankshaft design, which featured an unbalanced crank throw exactly like that seen in the Moth. In fact, apart from the displacement the major difference between the two designs is the switch from radial to beam mounting.

This having been said, it's entirely possible that the design influence of the Buchmann may have been at second hand. The reader will recall that E.P.C. actually developed the design of the original PALIKIT .85 following a lengthy evaluation of Phil Cox's 0.85 cc diesel of 1949. This does not necessarily upset the suggestion that the design drew heavily upon that of the Buchmann. It could simply mean that the design of Phil Cox's home-built model may have been influenced by that of the Buchmann, subsequently being copied at second hand by E.P.C. Engineering. After all, details of the Buchmann had been published in late 1946 in D. J. Laidlaw-Dickson's book "Model Diesels", We have no direct evidence to confirm that the unbalanced crank throw featured in the Moth was derived from a similar configuration in Phil Cox's engine - all we can say is that it seems likely. Whatever the influence, the un-counterbalanced crankshaft appears to have been designed into the PALIKIT/Moth from the outset rather than being a cost-cutting afterthought as might be supposed. The motivations for the design were entirely practical. The arrangement would allow the piston to sit far lower in the crankcase at bottom dead centre, thus minimizing the required vertical height of the engine. Perhaps more significantly, it would minimize the crankcase volume at bottom dead centre, thus increasing crankcase compression with considerable benefit to the transfer process. Indeed, the latter effect formed a major element of the previously-cited Patent taken out by Herbert Woolley. In addition, the fact that there's no crankdisc allows the use of a very long piston skirt with a relatively short rod. At bottom dead centre, the lower edge of the Moth's piston skirt intrudes well into the space which would be occupied by a full-disc crankweb if one was present. The recess in the rear face of the front housing to The use of the unbalanced crank in the Buchmann was apparently similarly motivated, as the previously-reproduced elevation section drawing extracted from Laidlaw-Dickson's 1946 book should make clear. This drawing shows the piston at bottom dead centre. If a full-disc crankshaft were to be used, the engine would require a significantly longer rod together with a shorter piston skirt to keep the piston clear of the crankdisc at bottom dead centre. The engine would have to be made considerably taller to maintain appropriate induction timing. Furthermore, the crankcase compression ratio would be substantially reduced. The only other engine of which I’m presently aware which used a similar unbalanced crank throw design was the DELMO Super 5 diesel from Paris, France which appeared in the spring of 1947. The primary motivation there was weight reduction. However, although the Super 5 enjoyed a period of success as one of France’s leading 5 cc diesels, the arrangement did not survive the test of time. The January 1949 replacement for the Super 5, the DELMO Super 49, featured a conventional fully counterbalanced crankweb. The E.P.C. Moth would doubtless have benefited from the use of a similar component if its internal structure and vertical height had permitted this. The previous discussion of the shortcomings of the Moth's crankshaft design brings us face to face with perhaps the most insidious and yet most fatal design flaw in the engine. It will be appreciated that in order for the assembly to work, the backplate had to be provided The problem which this creates is that during the entire top third of the stroke, when it is most heavily loaded, the conrod big end is completely unrestrained from moving rearwards on the crankpin. This would not be a problem if it was somehow constrained to remain vertically aligned with the crankpin in side view. However, any freedom to move rearwards on the gudgeon pin or tilt relative to the engine's vertical axis would permit the big end to wander off the crankpin to the rear with no restraint from the backplate. The design was perfectly practicable - all that was required was either the use of a screw-in keeper on the crankpin (using a left-hand thread) to keep the big end in position or, more practically, to equip the rod with an elongated and appropriately confined small end bearing which would both limit any tendency for the rod to move rearwards within the piston and also keep it in vertical side-view alignment with the cylinder axis and the crankpin. Unfortunately, neither course was adopted in the Moth - there's no big end keeper, while the small end bearing is very short, being of the classic "dog bone" pattern. It can be seen clearly in the image below.

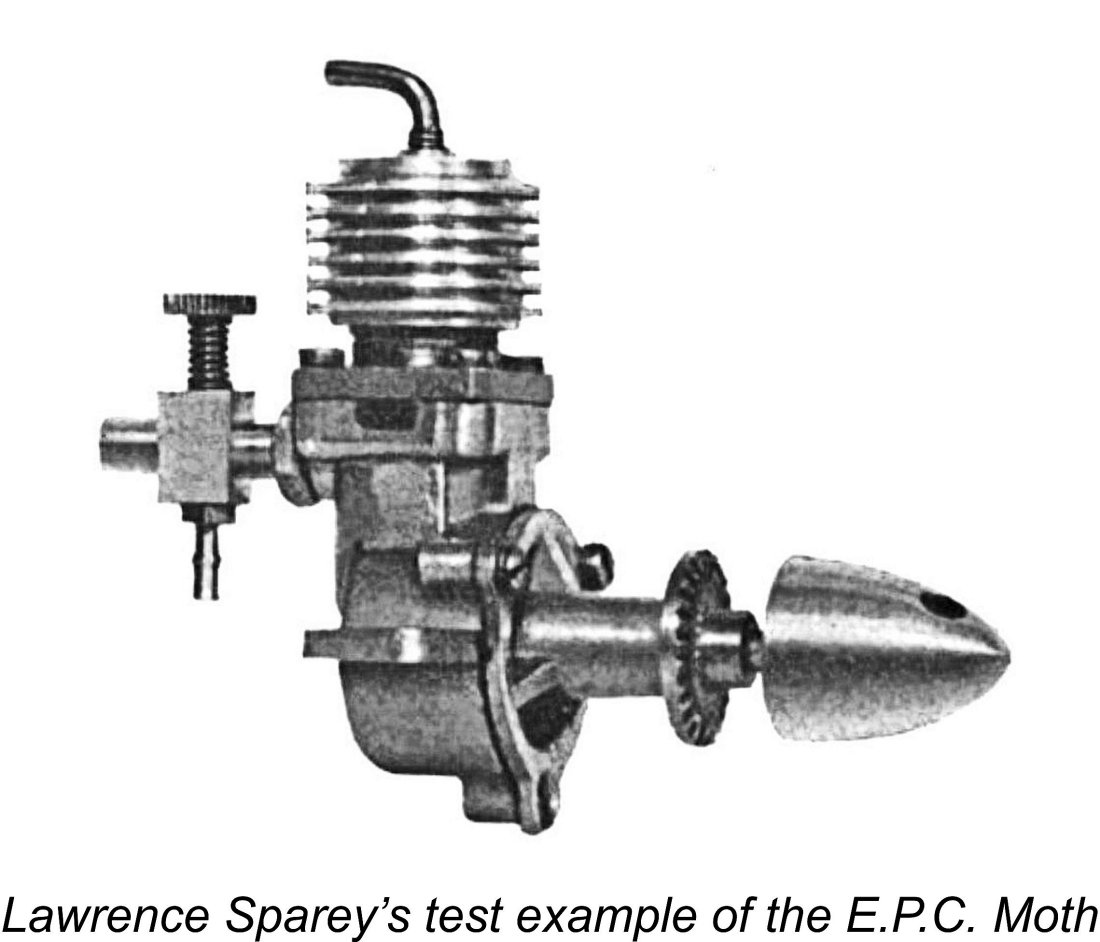

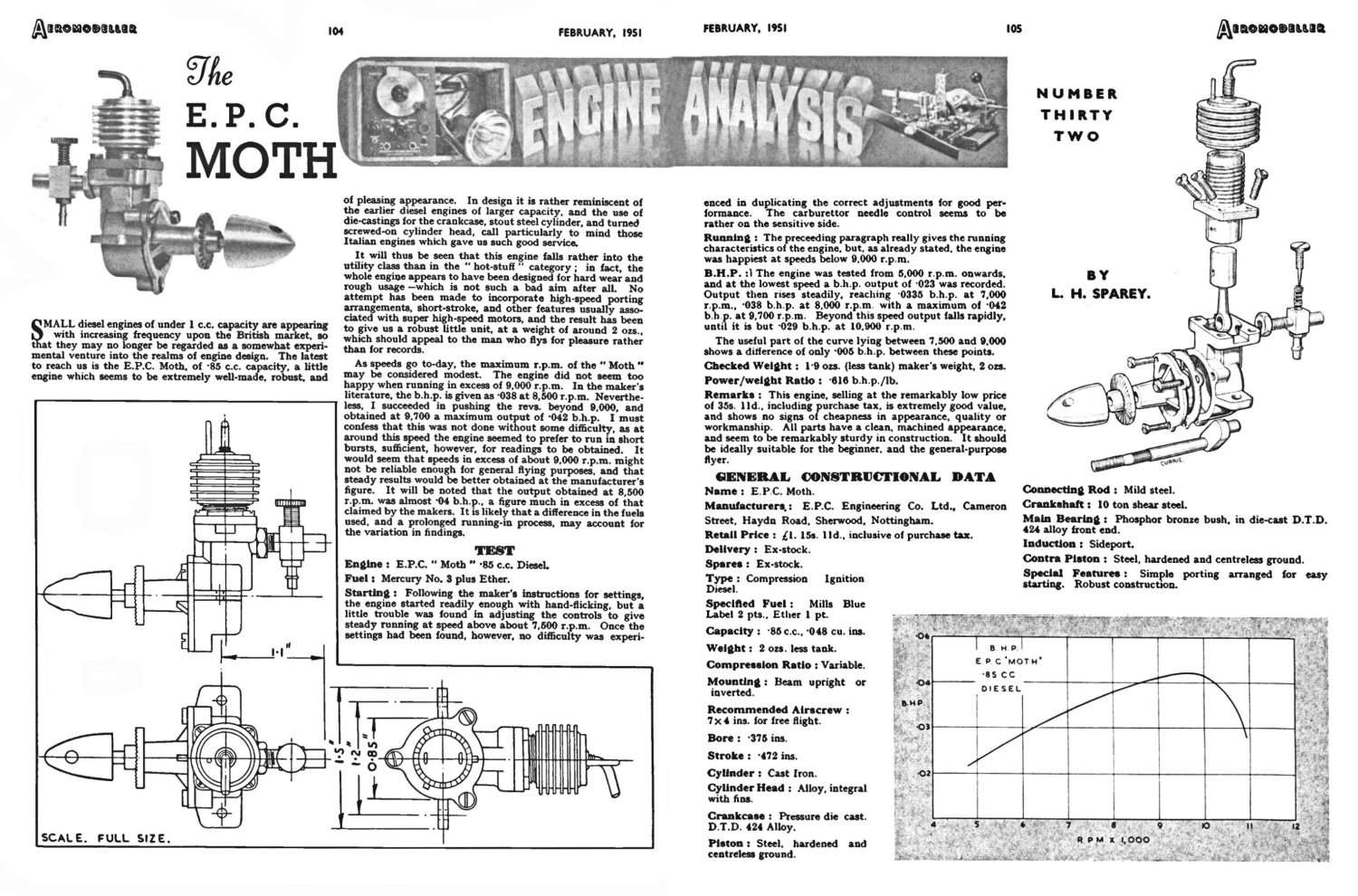

It's really quite surprising that the Moth designer couldn't see this issue coming. The engine obviously needed a full-width conrod small end bearing to resist both tilting and rearward movement. A large-diameter ball end would have really helped, as appears to have been used in the Buchmann 0.6 cc model. In the absence of such a small end bearing design, I wouldn't give this engine much chance of surviving more than an hour or two of running before the erosion of the lower backplate became chronic. My example has clearly done enough running to reach a problematic state. I won't be running it again with this rod fitted. Thankfully, the rest of the Moth's design is essentially straightforward, with no more surprises. At the front, the crankshaft runs in a phosphor bronze sleeve. A light alloy or steel prop driver is mounted onto a splined length of the front of the crankshaft, with a large aluminium alloy spinner nut being employed for prop attachment. The prop driver in Miles Patience's images is installed in reverse, an issue which was easily corrected after I received the engine. At the rear, the intake venturi is a screw-in light alloy component having a square-section portion in the middle to accommodate the needle valve and fuel supply spigot. The assembly screws into the induction boss at the rear of the upper crankcase and is secured in the desired orientation with a lock-nut. It would seem that fuel tanks When the PALIKIT contract failed, E.P.C. went to the additional expense of having sturdy attractively-decorated cardboard boxes made up in which to try to sell off the remaining engines as E.P.C. Moths. As recorded earlier, these efforts were unsuccessful. Setting aside the design quirks already mentioned, the Moth appears to have been manufactured to a more than acceptable standard - this is not one of your basic garden shed productions but is rather the product of a very capable manufacturer. It was the underlying design rather than any manufacturing deficiencies which let it down. Having examined the engine and its components, Miles Patience formed the opinion that the manufacturers ran out of incentive at some point. As we've seen, his insight was well founded! The company evidently started out with big ideas, investing a considerable amount of time and money in the creation of the crankcase and front housing dies to facilitate the large-scale production which they had good reason to anticipate at that stage. They also appear One indicator of this may be the progressive simplification of the prop driver. The original PALIKIT model illustrated earlier had a very well-machined deeply-serrated component made from light alloy. The previously-illustrated example tested by Sparey (likely a "good one") had a similar prop driver. However, the presumably later example now in my posession has a greatly simplified plain steel prop driver. Note that in the accompanying component view this prop driver is fitted in reverse, an issue which I later corrected. It's quite evident that the manufacturers set out to create a high-quality product with the expectation of selling it in quantity to PALIKIT at a rational price which would represent an appropriate return on their investment in time and money. The failure of the engine to perform at the required level scuppered the PALIKIT contract, leaving E.P.C. to rush the completion and re-badging of their now-surplus inventory to allow it to be sold directly on its own. Now, having looked at the engine itself, let’s see what can be done to learn something about its running characteristics. The E.P.C. Moth on Test The makers reportedly claimed an output for the Moth of 0.038 BHP @ 8,500 rpm. This was a very sub-standard performance by 1950 standards - a Mills .75 would easily beat these figures, as would a 0.55 cc Allbon Dart or an AMCO .87. It's scarcely a matter for wonder that the engine proved unequal to the task of flying the plastic PALIKIT control line model! As far as I can tell, the only person to check the manufacturer's claim was Lawrence H. Sparey, whose previously-mentioned test report on the engine appeared in the February 1951 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. My New Zealand friend Steve Haisworth wrote in to tell me that the exact same test report appeared in the March 1951 issue of "Aeromodeller's" sister pubication "Model Maker", sending me a scan as proof of his information.

Sparey praised the engine’s design and construction very highly, characterizing the Moth as “extremely well-made, robust and of pleasing appearance”. He conceded that the engine was something of a throw-back in design terms, bearing a strong resemblance to “the earlier diesel engines of larger capacity”. He found that it particularly called to mind “those Italian engines which gave us such good service”. In performance terms, Sparey stated that the Moth fell into “the utility class rather than in the “hot stuff” category”. None of the features associated with the high-speed engines which were then very much in vogue (short stroke, high-speed porting, rotary valve, etc.) were incorporated into the design, the result being what Sparey charitably described as “a robust little unit, at a weight of around 2 ounces, which should appeal to the man who flies for pleasure rather than for records”.

Sparey concluded by making the statement that “This engine, selling at the remarkably low price of 35s 11d, including purchase tax, is extremely good value and shows no signs of cheapness in appearance, quality or workmanship”. He felt that it should appeal to beginners and general-purpose fliers alike. Reading this extremely laudatory review, one can’t quite avoid a nagging suspicion that “the fix was in”! One statement by Sparey which enhances this impression is his characterisation of the measured output at 8,500 rpm of 0.040 BHP as being "much in excess of that claimed by the makers". Really?!? It's hard to see a figure of 0.040 BHP as being "much in excess" of the maker's claimed 0.038 BHP at the same speed! However, an even more persuasive piece of evidence is Sparey’s noteworthy failure to so much as mention the Moth’s chief design failing, which was that completely un-counterbalanced crankshaft coupled with its long stroke and heavy piston. One begins to wonder if Sparey was a friend of the manufacturer (Sammy Diggle) and was doing what he could to help him out?!? In operation, the absence of a crankdisc with its accompanying dampening mass plus the complete absence of any counterbalancing would be a guaranteed set-up for giving rise to excessive levels of vertical vibration and bearing stress, particularly at the higher speeds. You wouldn’t even have to run the engine to figure this out. It’s really hard to believe that Sparey would not have experienced severe vibration during the test, particularly at the speeds above 9,000 rpm at which he claimed to have run the engine. However, he makes no mention at all of the Moth’s vibration characteristics, although he generally did so in other tests. Sparey seems to have been falling over himself to present the Moth in a far more favourable light than it really merited. This omission from what purported to be an objective test of the engine is really difficult to explain …….. indeed, the fact that the test appeared at all seems a little surprising given the number of clearly superior designs in the testing line-up at the time. There’s an untold story here ………….let's have a speculative go at telling it! The best potential explanation for this that I can come up with is the idea that the manufacturer (Sammy Diggle) may have been a friend or at least an acquaintance of Sparey’s. Diggle understandably wished to liquidate his considerable investment in the engine to the extent possible without going to the extra expense of advertising it - why throw good money after bad?!? If this was indeed the situation (and I hasten to remind the reader that it’s no more than uncorroborated speculation), then Diggle may have completed any unfinished engines on the cheap and then turned to Sparey for advice and assistance in getting rid of them, at the same time bringing in Raylite on the marketing side. Sparey may have agreed to help out by publishing a positive test of the Moth in “Aeromodeller” magazine to stimulate some interest, following it up with the same test being repeated verbatim in the March issue of "Model Maker". This would represent free publicity of the best and broadest kind, spread over a two-month period. Moreover, Diggle had Raylite doing his advertising for him for free! This notion would explain why Sparey seems to have been the only contemporary model engine commentator to pay any attention whatsoever to the Moth. Moreover, his review contained nothing to offset the impression that the Moth was in current production at the time of his review, which he must surely have known that it wasn't if this scenario is correct. No-one was going to take an interest in an engine which was in its death-throes in reality, so why bring that matter up?!?! A desire to help a friend out of a jam would also explain Sparey’s failure to mention the crankshaft imbalance issue. In his defence, it must be said of Sparey that he told no lies in his review - he was merely economical with the truth! It wasn't what he said - it was what he didn't say!

Although the example from Mike Patience’s collection and now in my care certainly showed evidence of wear and tear, Miles did give it a go before sending it along to me. Having examined the condition of the engine's interior and grasped its design shortcomings, I actually wish that he hadn't done so - more of the backplate chewed away! However, what's done is done! Miles was good enough to record the results of his efforts on this video clip. The run is so short because that’s as long as the thing would run, for whatever reason. Accordingly, Miles was unable to extract any meaningful performance figures. The rather abrupt manner in which the engine stops suggests that the stoppage was brought about by the wandering rod hanging up on the backplate shelf - the casting shows clear evidence of this having occurred. I certainly won't be attempting any more running myself unless I bestir myself to make a new properly designed rod! However, at least we get to see one run, however briefly! The E.P.C. Moth Replicas

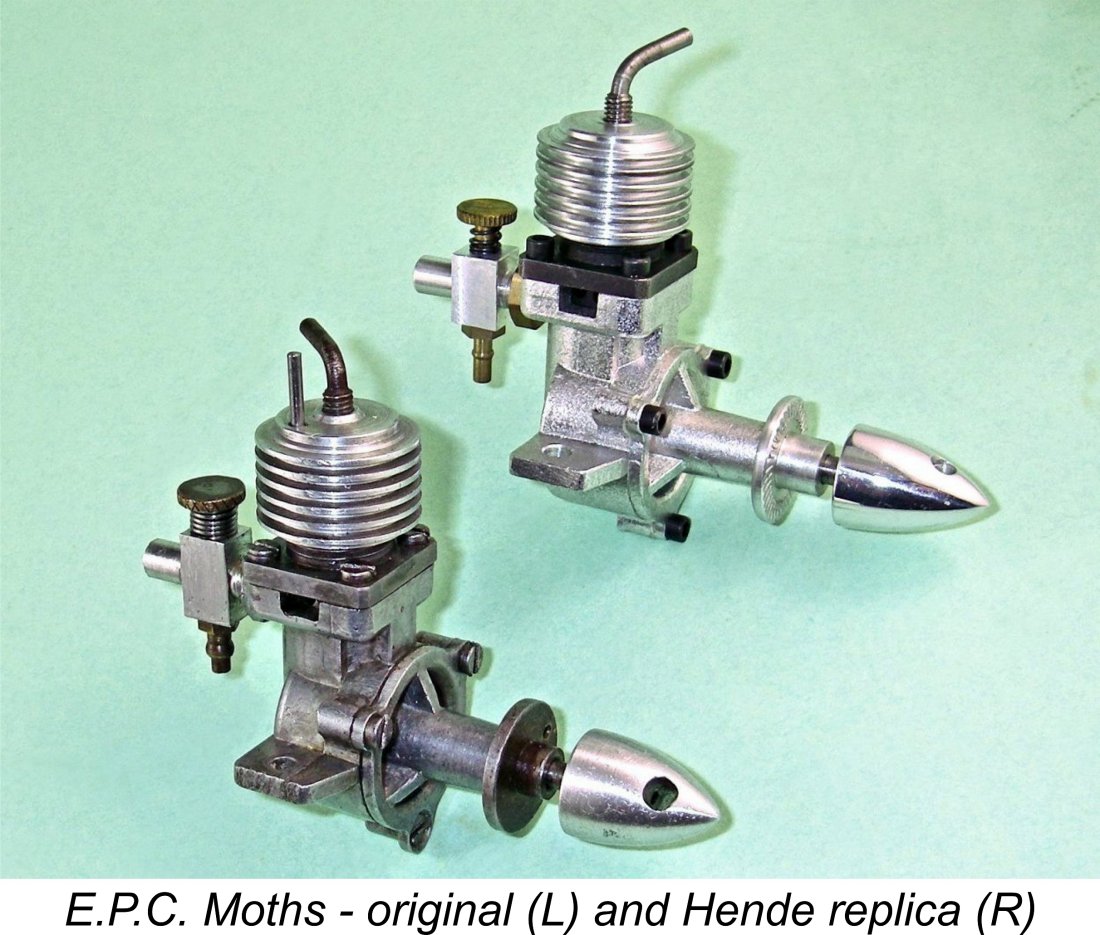

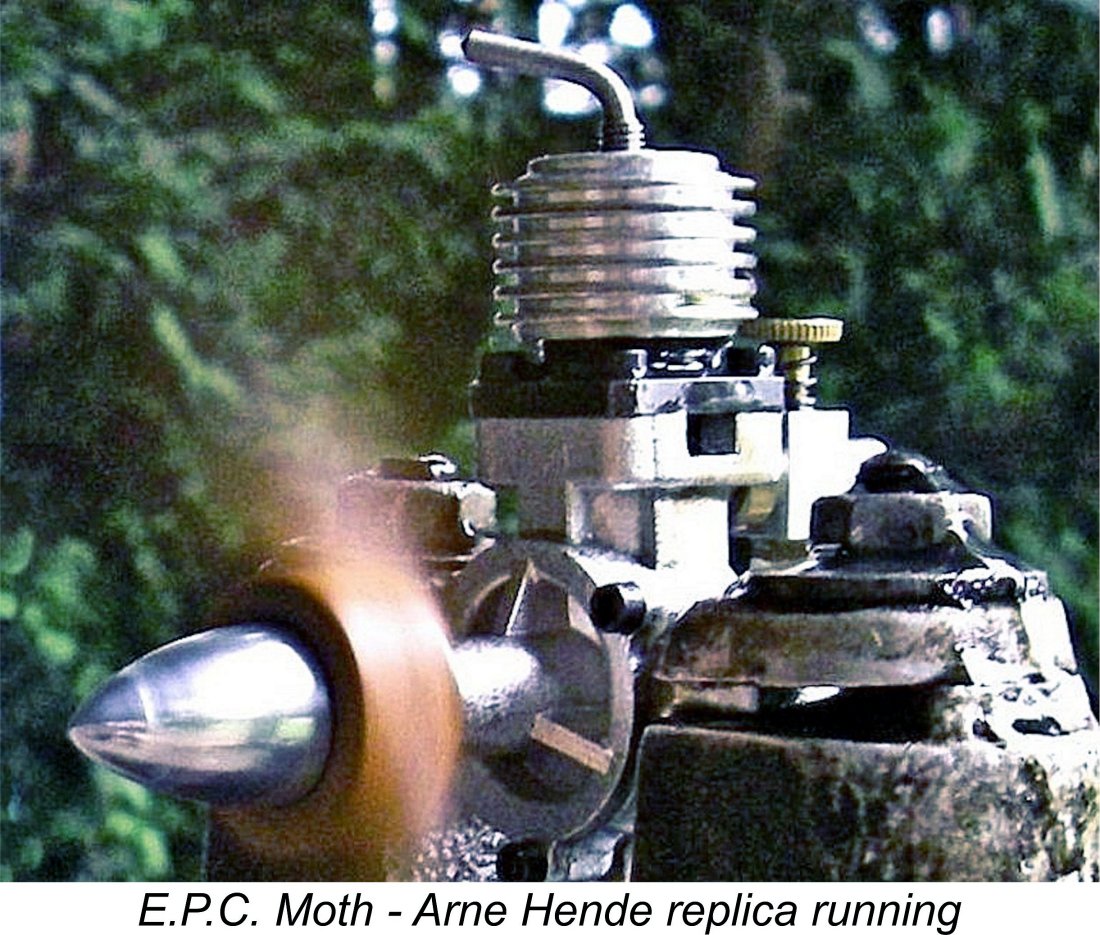

I was fortunate enough to acquire a mint boxed example of the Hende replica for evaluation during the preparation of this article. The engine is constructed to Arne Hende's usual very high standards. A little unusually, it does not bear a serial number. As can be seen in the attached comparison image, the Hende replica is extremely faithful to the original in terms of its Internally, it's a somewhat different story. As was so often the case, Arne refined the internal design of the replica to address some of the original Moth's design shortcomings. He built his replicas to be used! The un-balanced crank throw is retained, as it has to be for the engine's assembly. However, the cutaways in the rear of the main crankcase and the front housing to accommodate the piston at bottom dead centre have been reduced in diameter to the absolute minimum required. This both reduces the period around top dead centre during which the con-rod big end is free to move rearwards and reduces crankcase volume a little.

With this revised con-rod design, I would expect the Hende replica to be a reliable runner which should wear very well. Arne always designed his replicas to be used, and this one's no exception. The condition of the crankcase interior and the feel of the engine combined to confirm that the replica had not been test-run. I elected to set this previously-unrun example up in the test stand just to see how it fared in operation. Some readers might be thinking that this was a bad move, since it turned a brand-new unrun boxed example of the Hende replica into a bench-run boxed example. My response is - so what?!? All engines should at least be test-run, which is all that I planned to do. In any case, a replica that can't be run does very liittle for me! Why bother ..............?!?

The Hende replica proved to be a very easy starter, presumably reflecting the characteristics of the originals. After the first run it never needed a prime - a few choked flicks were all that it required. Very like a Mills, in fact! Running characteristics were very good once the settings had been established. One fly in the ointment here was a very sensitive needle valve - a not uncommon characteristic of engines using surface jet needle valves. The other issue was the fact that despite the engine's very smooth running characteristics when leaned out, there simply wasn't much power! Admittedly, this example was making its first-ever runs, making it very likely that performance would improve somewhat with a full break-in. However, any such improvement would probably be relatively minimal given the first-class fits and finishes with which the Hende replica was supplied. As matters stood, I confined myself to twelve minutes of slightly rich and undercompressed running in 3 minute runs on the 8x4 to settle the components down a little, leaning out for the final 20 seconds or so to subject the engine to the necessary full-range heat cycles. After that, I took a spot-check leaned-out reading at the end of a two-minute slightly rich run on each prop tested. The replica managed 6,300 rpm on the Top Flite 8x4 - around 0.027 BHP. A switch to an APC 7x6 got the Moth up to 6,600 rpm (c. 0.029 BHP) while an APC 7x5 improved the speed to 7,400 rpm (around 0.032 BHP). That was as far as I was prepared to push the still running-in engine. Leaned-out running on the two slower props was very smooth, with vibration levels remaining within acceptable limits. However, while running was just as smooth on the 7x5, vibration was beginning to assert itself to a noticeable extent. At the claimed peak of 8,500 rpm I would expect vibration to become a significant issue.

Looking at the indicated levels of performance, it's no wonder that the unit failed to power the PALIKIT models to an acceptable standard. The thing would barely blow the froth off a pint of beer! It would certainly do an OK job of flying a small free flight sport model, especially given its very light weigh, but control line would have been strictly off limits. Even so, the Hende replica showed itself to be an easy starting, smooth running and durable little engine which was a real pleasure to run. Anyone wishing to actually run a Moth today would do well to track down one of these replicas - there’s probably far more chance of finding one of Arne's gems than an original, since the number produced by Arne very likely exceeded that of the surviving originals by some margin. Arne built these engines to be run, and I'm sure he'd be pleased if more of us did so! Apart from the unsold original examples that probably ended up in the metal recycling bin back in 1951, many of the originals that were sold were probably discarded once their operating shortcomings became apparent - their very low price would have encouraged owners to view them as "disposable" engines. Moreover, their perceived resale value would probably have been nil. By contrast, the Hende replicas are highly prized and completely servicable collector's items, almost all of which will have survived in new or little-used condition. However, you’ll pay for the privilege of ownership…...... Having been so complimentary regarding the Hende replica based upon my own experience, I must now share some comments which were received from my friend Dave Causer following the original appearance of this article. Dave had bought an Arne Hende replica of the Moth a few years previously. When trying this engine, he ran into what is evidently a residual weakness of the design. He found that after a couple of runs he was having to screw the compression progressively further down to achieve smooth running. On subsequent investigation, he found that the gudgeon pin had a diameter of only 1.5 mm (fractionally less than the original engine's 1/16 in. / 1.59 mm diameter) and had bent under the applied operating stresses. Dave reamed the conrod and piston to accommodate a 2 mm diameter pin. He would have liked to go a bit bigger but there wasn't sufficient meat on the little end. However, this modification restored the engine's performance (such as it was!). It's unclear if all of the Hende replicas are similarly configured, but if so this would seem to be a weak point in the design. I can only comment that my example did not exhibit any signs of such behaviour during the 20 minutes or so of running that it received at my hands. Dave was well able to confirm the engine's underwhelming performance! He agreed completely with my assessment that it would have been completely useless in a control line model, but would have been fine in a small free flight sport model like a Tomboy. The Hende replica was not alone. Ivan Prior's I. P. Engineering company produced a small batch of 10 equally fine replicas of the Moth, also during the 1990's. As you'd expect from the relative numbers produced, these are far less common than the Hende renditions, actually being if anything less commonly encountered than the originals. Good luck trying to find one ......... Summary

To summarize, the Moth started out life in early to mid 1950 as a proposed powerplant for use in plastic ready-to-fly control line models. It was to be manufactured in quantity to a quite high standard under contract to another firm. When that contract was terminated due to the engine's failure to achieve the required level of performance, the manufacturer attempted to recover as much as possible of his investment by re-naming the unit as his own product, re-packaging it and marketing it at a fire-sale liquidation price. Despite the evident intervention on his behalf by Lawrence Sparey and the involvement of Raylite, this effort failed. Many of the original engines doubtless ended up in the scrap bin. Reviewing the engine’s previously-discussed shortcomings, it’s no surprise at all that the Moth failed in the marketplace, sinking without trace very quickly. Most of them probably went into the aforementioned scrap bin. Surviving original examples are few and far between today, and any that do survive probably never get run. Indeed, they probably shouldn't be run - the ill effects of the very poor conrod design will manifest themselves quite rapidly in all probability. For the running experience, you have to turn to a replica, assuming that you can find one. I'm pretty confident of my ability to turn my original example into a dependable runner. I'd have to make a new rod (probably of high-strength light alloy) having an extended small end bearing to keep the big end in line with the crankpin at all times. The engine would almost certainly run just fine with that modification aboard. But then it wouldn't be original, would it? For now, I'm electing to keep it original, even though it isn't really in running condition. Just a personal choice ................if I ever experience an uncontrollable urge to run a Moth, there's always the Hende replica! Anyway, there you have it - a far more complete record than I ever expected to be able to compile about one of England’s less glorious failures in the model diesel field! Despite its short and unhappy history, the E.P.C. Moth is an interesting element of Britain’s model engine heritage, and one which deserves not to be forgotten! ____________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published October 2020 |

| |

In this article, I’ll summarize what is known or can be deduced about one of the most ephemeral, enigmatic and (it must be said) fatally flawed model diesels ever to appear in England. I’ll be reviewing the almost forgotten saga of the short-lived E.P.C. Moth 0.85 cc diesel from Nottingham, England. If you blinked twice, you missed this one!

In this article, I’ll summarize what is known or can be deduced about one of the most ephemeral, enigmatic and (it must be said) fatally flawed model diesels ever to appear in England. I’ll be reviewing the almost forgotten saga of the short-lived E.P.C. Moth 0.85 cc diesel from Nottingham, England. If you blinked twice, you missed this one!

We are extremely fortunate in having access to some first-hand information on this topic thanks entirely to the much-appreciated efforts of former "Model Engine World" (MEW) publisher John Goodall. My sincere thanks are due to Kevin Richards for pointing me towards this invaluable source!

We are extremely fortunate in having access to some first-hand information on this topic thanks entirely to the much-appreciated efforts of former "Model Engine World" (MEW) publisher John Goodall. My sincere thanks are due to Kevin Richards for pointing me towards this invaluable source!

The engines were marketed on E.P.C.'s behalf by the well known Raylite firm, also of Nottingham, as well as the London-based Ripmax company. The effort to sell off the re-badged engines was not helped by the fact that the Moth never appears to have been nationally advertised by the manufacturers, nor did it appear in any model shop listings apart from those few placed by Raylite and Ripmax. Its distribution seems to have been largely confined to its native Nottingham, although a few were doubtless sold in London by Ripmax.

The engines were marketed on E.P.C.'s behalf by the well known Raylite firm, also of Nottingham, as well as the London-based Ripmax company. The effort to sell off the re-badged engines was not helped by the fact that the Moth never appears to have been nationally advertised by the manufacturers, nor did it appear in any model shop listings apart from those few placed by Raylite and Ripmax. Its distribution seems to have been largely confined to its native Nottingham, although a few were doubtless sold in London by Ripmax.  By May 1951 the engine had been demoted to a similar status to that of the other engines offered by Raylite - it was listed, but there was no photograph. It would appear that Raylite's enthusiasm was waning ...... indeed, by June 1951 it had waned completely, since the engine was no longer even listed. Raylite's listing of the Moth in their May 1951 advertisement was thus their final mention of the engine.

By May 1951 the engine had been demoted to a similar status to that of the other engines offered by Raylite - it was listed, but there was no photograph. It would appear that Raylite's enthusiasm was waning ...... indeed, by June 1951 it had waned completely, since the engine was no longer even listed. Raylite's listing of the Moth in their May 1951 advertisement was thus their final mention of the engine.

The E.P.C. Moth (as I will call it from now on) was a more or less conventional-looking 0.85 cc long-stroke sideport diesel of the early post-WW2 period. At the time in question, British model engine designers still preferred to work in fractions of an inch despite invariably expressing displacements in cc …… go figure! Nominal bore and stroke of the Moth were 3/8 in. (0.3750 in. / 9.52 mm) and 15/32 in. (0.4687 in. / 11.90 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 0.05177 cuin. (0.848 cc). The engine weighed a checked 55 gm (1.94 ounces) - remarkably light for its displacement.

The E.P.C. Moth (as I will call it from now on) was a more or less conventional-looking 0.85 cc long-stroke sideport diesel of the early post-WW2 period. At the time in question, British model engine designers still preferred to work in fractions of an inch despite invariably expressing displacements in cc …… go figure! Nominal bore and stroke of the Moth were 3/8 in. (0.3750 in. / 9.52 mm) and 15/32 in. (0.4687 in. / 11.90 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 0.05177 cuin. (0.848 cc). The engine weighed a checked 55 gm (1.94 ounces) - remarkably light for its displacement.

When it comes to the issue of the cylinder material, Lawrence Sparey threw a bit of confusion into the mix by stating in the text of his February 1951 test report that the cylinder material is steel. However, in the table of specifications he cited the cylinder material as being cast iron!! Having now inspected an example for myself, I can confirm beyond doubt that the material is indeed hardened steel.

When it comes to the issue of the cylinder material, Lawrence Sparey threw a bit of confusion into the mix by stating in the text of his February 1951 test report that the cylinder material is steel. However, in the table of specifications he cited the cylinder material as being cast iron!! Having now inspected an example for myself, I can confirm beyond doubt that the material is indeed hardened steel.  An intriguing observation at this point is the presence in my example of a shallow internal flute on the inner wall of the cylinder at the transfer location. It's not unlikely that this represents an attempt by the manufacturers to address the power deficiency issue identified by the engine's planned PALIKIT buyer by enhancing its bypass capacity. However, it could also be an owner modification.

An intriguing observation at this point is the presence in my example of a shallow internal flute on the inner wall of the cylinder at the transfer location. It's not unlikely that this represents an attempt by the manufacturers to address the power deficiency issue identified by the engine's planned PALIKIT buyer by enhancing its bypass capacity. However, it could also be an owner modification.

The result is that the rod is free to move rearwards within the piston, as seen in the accompanying image. Worse, as soon as a little small end wear develops, allowing the rod to tilt out of vertical alignment in side view, it will inevitably do so under the loads imposed first by the completion of the compression stroke and then by the start of the power stroke. At those points of maximum loading, the rod will seek relief by tilting out of alignment to the degree allowed by the very short small end bearing. There's clear evidence in my own example that it has already done so to the extent that it has been chewing away at the material of the backplate - the image above at the right shows this very clearly. With the relatively short small end bearing actually used, it wouldn't take much wear for this to reach problematic levels.

The result is that the rod is free to move rearwards within the piston, as seen in the accompanying image. Worse, as soon as a little small end wear develops, allowing the rod to tilt out of vertical alignment in side view, it will inevitably do so under the loads imposed first by the completion of the compression stroke and then by the start of the power stroke. At those points of maximum loading, the rod will seek relief by tilting out of alignment to the degree allowed by the very short small end bearing. There's clear evidence in my own example that it has already done so to the extent that it has been chewing away at the material of the backplate - the image above at the right shows this very clearly. With the relatively short small end bearing actually used, it wouldn't take much wear for this to reach problematic levels.

to have done an excellent job with the machining quality of the crankcase, cylinder, piston and conrod. However, at some point they seem to have switched to a policy of rushing the rest of the production. This presumably coincided with the severing of the PALIKIT connection.

to have done an excellent job with the machining quality of the crankcase, cylinder, piston and conrod. However, at some point they seem to have switched to a policy of rushing the rest of the production. This presumably coincided with the severing of the PALIKIT connection.

Sparey found the engine to be quite straightforward to hand-start. He noted that control settings became rather critical at speeds above 7,500 rpm, the needle in particular being somewhat sensitive. At speeds above 9,000 rpm the Moth would not run continuously, but rather in short bursts. Sparey felt that the engine would be best propped for the manufacturer’s 8,500 rpm figure, at which speed he measured an output of 0.040 BHP, thus confirming the manufacturer’s claim. I must say that I’m at a loss to explain the high-speed behavior described by Sparey ………..

Sparey found the engine to be quite straightforward to hand-start. He noted that control settings became rather critical at speeds above 7,500 rpm, the needle in particular being somewhat sensitive. At speeds above 9,000 rpm the Moth would not run continuously, but rather in short bursts. Sparey felt that the engine would be best propped for the manufacturer’s 8,500 rpm figure, at which speed he measured an output of 0.040 BHP, thus confirming the manufacturer’s claim. I must say that I’m at a loss to explain the high-speed behavior described by Sparey ……….. Quite apart from the vibration issue, the severe imbalance incorporated into the engine’s design would inevitably subject the main bearing to elevated surface loadings around its full inner circumference as well as un-dampened pounding. This undoubtedly explains why the main bearing in the illustrated example shows some evidence of wear - it wouldn’t take much running to get it to that state. The obvious fix would appear to be to make a new shaft having a counterbalanced full-disc crankweb, but the vertical height of the engine does not permit this, as discussed earlier - a comprehensive re-design would be required.

Quite apart from the vibration issue, the severe imbalance incorporated into the engine’s design would inevitably subject the main bearing to elevated surface loadings around its full inner circumference as well as un-dampened pounding. This undoubtedly explains why the main bearing in the illustrated example shows some evidence of wear - it wouldn’t take much running to get it to that state. The obvious fix would appear to be to make a new shaft having a counterbalanced full-disc crankweb, but the vertical height of the engine does not permit this, as discussed earlier - a comprehensive re-design would be required.

The designer of the Hende replica clearly appreciated the problems potentially arising from rearward movement or tilting of the con-rod. He followed my earlier suggestions completely, first by making the replica's rod out of high-quality light alloy and then by greatly enlarging the diameter of the ball at the small end to create a significantly longer tilt-resistant small end rod bearing. Finally, the piston interior is machined to create just enough space for the small end and no more, thus effectively eliminating any possibility of rearward movement. This is the E.P.C. Moth as it could and should have been constructed at the outset.

The designer of the Hende replica clearly appreciated the problems potentially arising from rearward movement or tilting of the con-rod. He followed my earlier suggestions completely, first by making the replica's rod out of high-quality light alloy and then by greatly enlarging the diameter of the ball at the small end to create a significantly longer tilt-resistant small end rod bearing. Finally, the piston interior is machined to create just enough space for the small end and no more, thus effectively eliminating any possibility of rearward movement. This is the E.P.C. Moth as it could and should have been constructed at the outset. I used a Top Flite wood 8x4 prop, which I judged to be a suitable load for allowing the engine to make a few break-in runs. Since I wasn't planning to carry out a complete break-in, I elected to content myself with taking speed readings during the final leaned-out burst following a slightly rich and undercompressed break-in run, as descibed in my companion article on

I used a Top Flite wood 8x4 prop, which I judged to be a suitable load for allowing the engine to make a few break-in runs. Since I wasn't planning to carry out a complete break-in, I elected to content myself with taking speed readings during the final leaned-out burst following a slightly rich and undercompressed break-in run, as descibed in my companion article on  The trend of these figures suggested that the engine was going to come fairly close to the claimed 0.038 BHP @ 8,500 rpm, but certainly not more. Not wishing to put any more running time on this now LNIB example, I terminated the test at this point, feeling that I'd done enough to confirm the rather low performance of this design. The Hende replica remained in perfect condition at the end of the session.

The trend of these figures suggested that the engine was going to come fairly close to the claimed 0.038 BHP @ 8,500 rpm, but certainly not more. Not wishing to put any more running time on this now LNIB example, I terminated the test at this point, feeling that I'd done enough to confirm the rather low performance of this design. The Hende replica remained in perfect condition at the end of the session.