|

|

The DELMO Engines

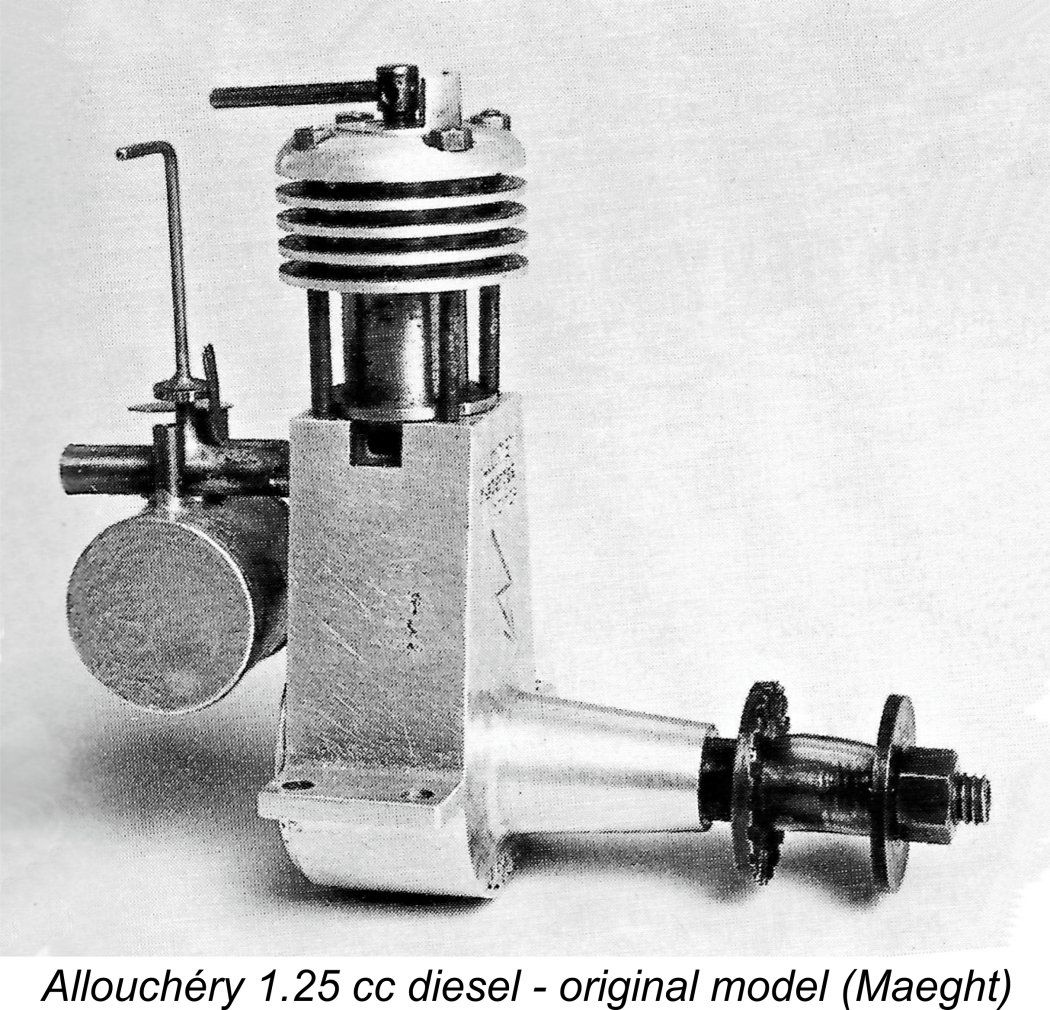

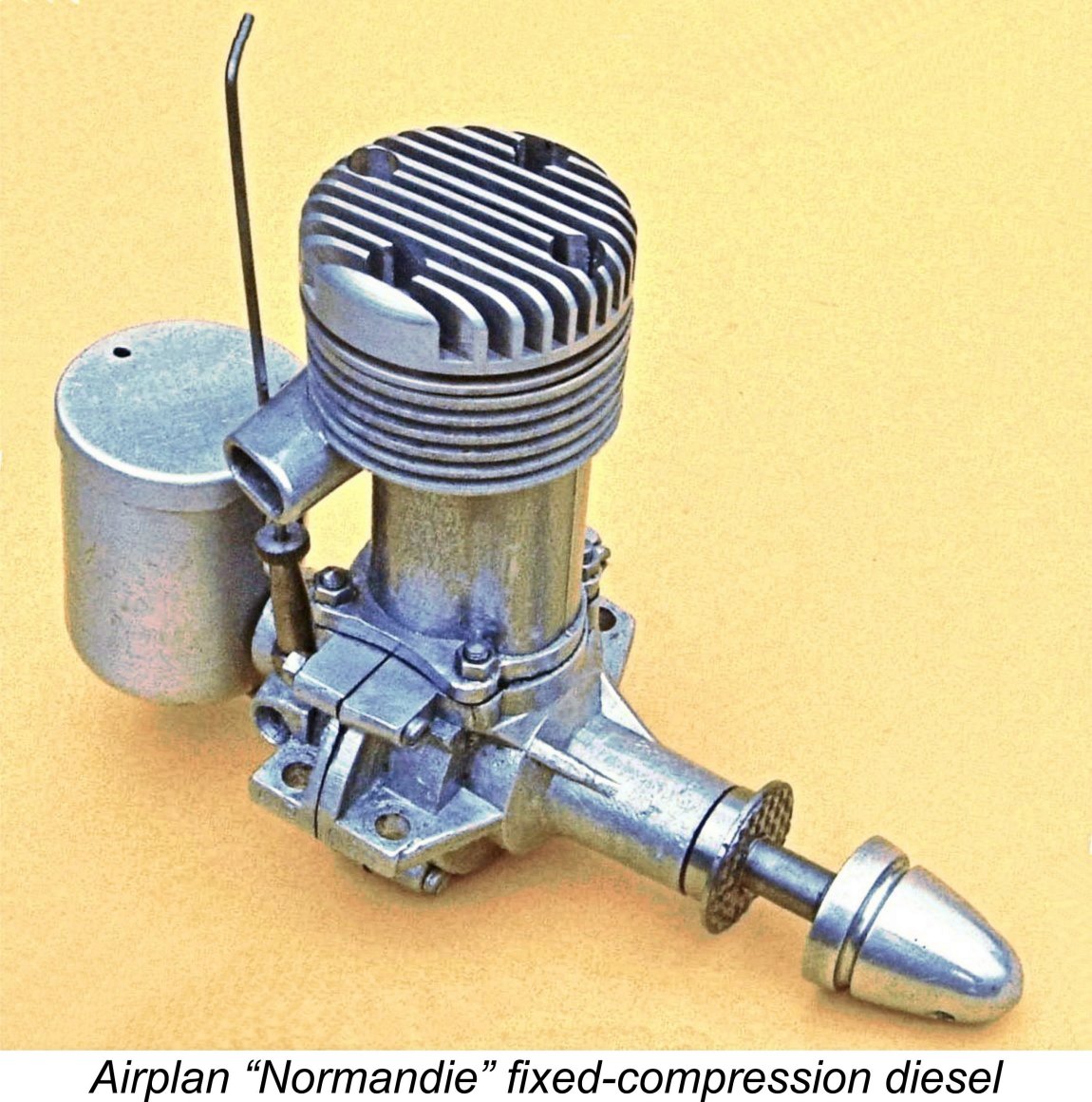

For reasons which are unclear, accessible information about engines from those early years in France appears to be in relatively short supply, at least in the English language. This is a great pity, because the history of French model engine development is every bit as interesting as that of parallel efforts in other countries. We Anglophones have been missing out ............ In particular, the focused development of the model diesel engine in France preceded British and American efforts along those lines by a good three years, giving the French a commanding early lead in this field. Consequently, at the time when the first British commercial model diesels appeared in mid 1946, no fewer than 11 French manufacturers (including our subject DELMO) were already offering model diesels! Some of these firms had been active for up to five years at that point in time. Another very good reason for any true model engine enthusiast to take an interest in French designs is the unquestionable fact that in general their quality was of the very highest order. The products of pioneering French manufacturers such as Micron, Airplan, Allouchéry, DELMO, R.E.A., Fulgur, Maraget-Météore and Bosmorin (to name just a few) were all built to the very highest standards - no early British-style “garden shed” offerings here! It Quite apart from that, a surprising number of French model engines exhibited a remarkable ability on the part of their designers to “think outside the box”. The talented designer of the DELMO engines was no exception to this, as we shall see. The general excellence of the early French model diesels was such that some of them exerted a strong influence upon British and American designers during the early post-WW2 period. Well-known engines such as the Airstar, Mills 1.3 Mk. I and Owat from Britain as well as the Drone and Mite from America all had French design origins. Having made the above statements, honesty compels me to freely acknowledge the fact that I possess very little first-hand knowledge of French model engines despite owning a number of examples from different manufacturers. Engines from that country were not imported into Britain to any great extent during the period when I was cutting my modelling teeth there, nor were French engines the subject of more than passing references in the contemporary English-language modeling media.

Like every other model engine reference work of my acquaintance (doubtless including this website!), Maeght's publication is not free from error. Nevertheless, no-one having even a peripheral interest in the fascinating history of model engine development and manufacture in general, and in France in particular, can afford to be without a copy. Although now out of print, copies of the book periodically become available both through Amazon France and eBay France, which is how I obtained my copy. However, the book is not cheap – typically you’ll pay somewhere around 65 euros (US$80.00). Well worth it, though – what price knowledge?? There’s no other equivalent publication. In a very real sense, this is the French equivalent of Tim Dannels’ invaluable “American Model Engine Encyclopedia” (AMEE). I freely acknowledge having drawn extensively upon this outstanding work when carrying out the research for this article. I have also used a number of illustrations from the book, all of which are acknowledged in the captions. My sincere thanks to Adrien Maeght and his colleagues! Another invaluable source of information about the DELMO venture is the series of highly informative commentaries which appear in Michel Rosanoff’s outstanding model engine history thread on the Retroplane forum. Although presented in French, the information on this forum may easily be rendered into comprehensible English using current translation software. Many high quality images of very rare French engines appear on this site, along with a good deal of information about engines from other I freely acknowledge having consulted Michel’s outstanding work frequently during the preparation of this article. I’ve also used a number of images extracted from that thread, with Michel’s kind permission. Now, having listed my sources with my grateful acknowledgement, it’s time to look into the background leading up to the introduction of the DELMO engines. Those who are already familiar with this material are invited to skip to the following sections at this point. The rest of you, read on ………… Background

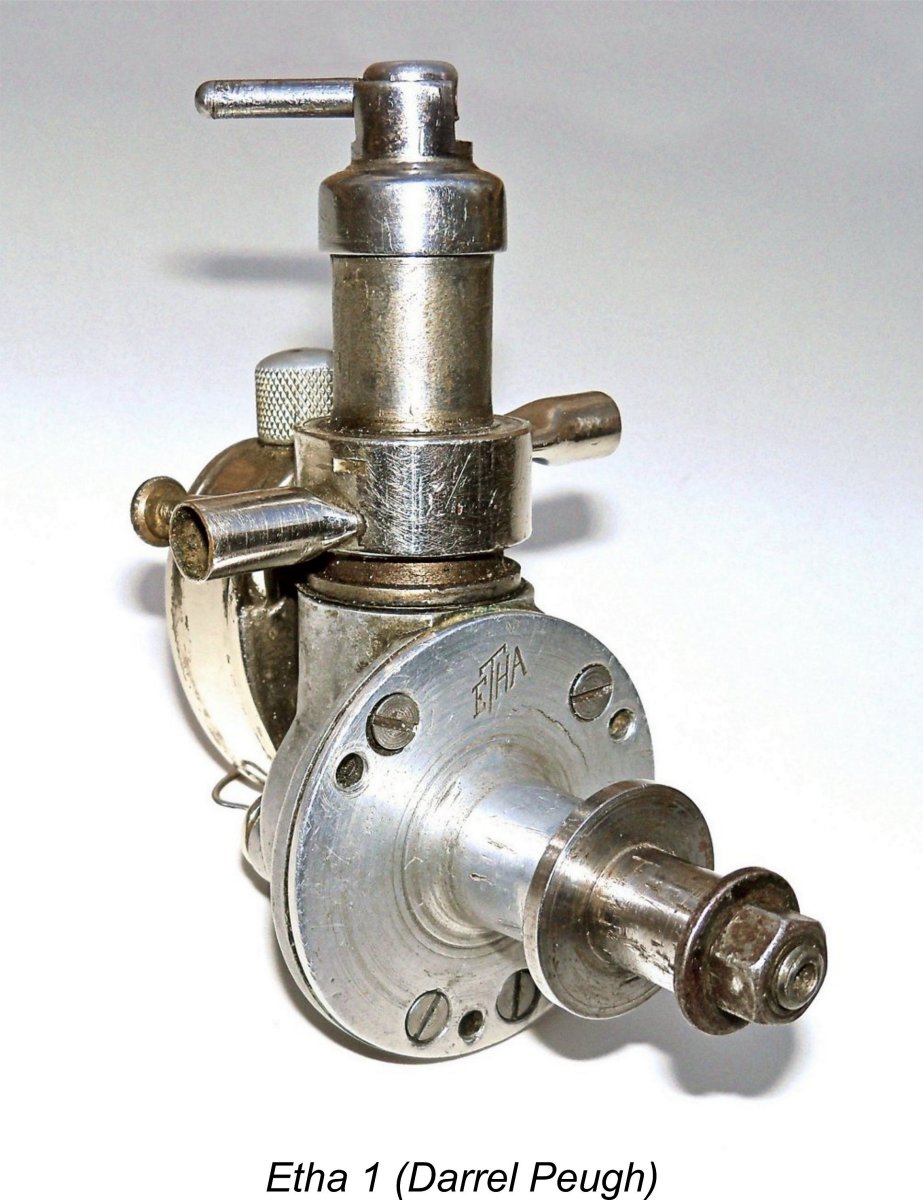

It seems that the demonstration did not elicit offers of instant riches, but Thalheim did produce “full size” ETHA (Ernst Thalheim) two-stroke stationary engines in accordance with the customer’s particular requirements. These included single-cylinder farm engines, an inline multi-cylinder 500 cc (30 cuin.) boat engine rated at 20 HP and a 106 cc (6.5 cuin.) boxer twin-cylinder engine reportedly used in a light aircraft (perhaps a power-assisted glider?). A range of 12 “model” size ETHA’s ranging from 0.4 cc to 25 cc were also individually constructed to custom order over the subsequent decade. These were most likely marketed as table-top curios for the mechanically minded, much like miniature steam engines. At this stage, Thalheim does not appear to have had any strong interest in the field of powered model aircraft.

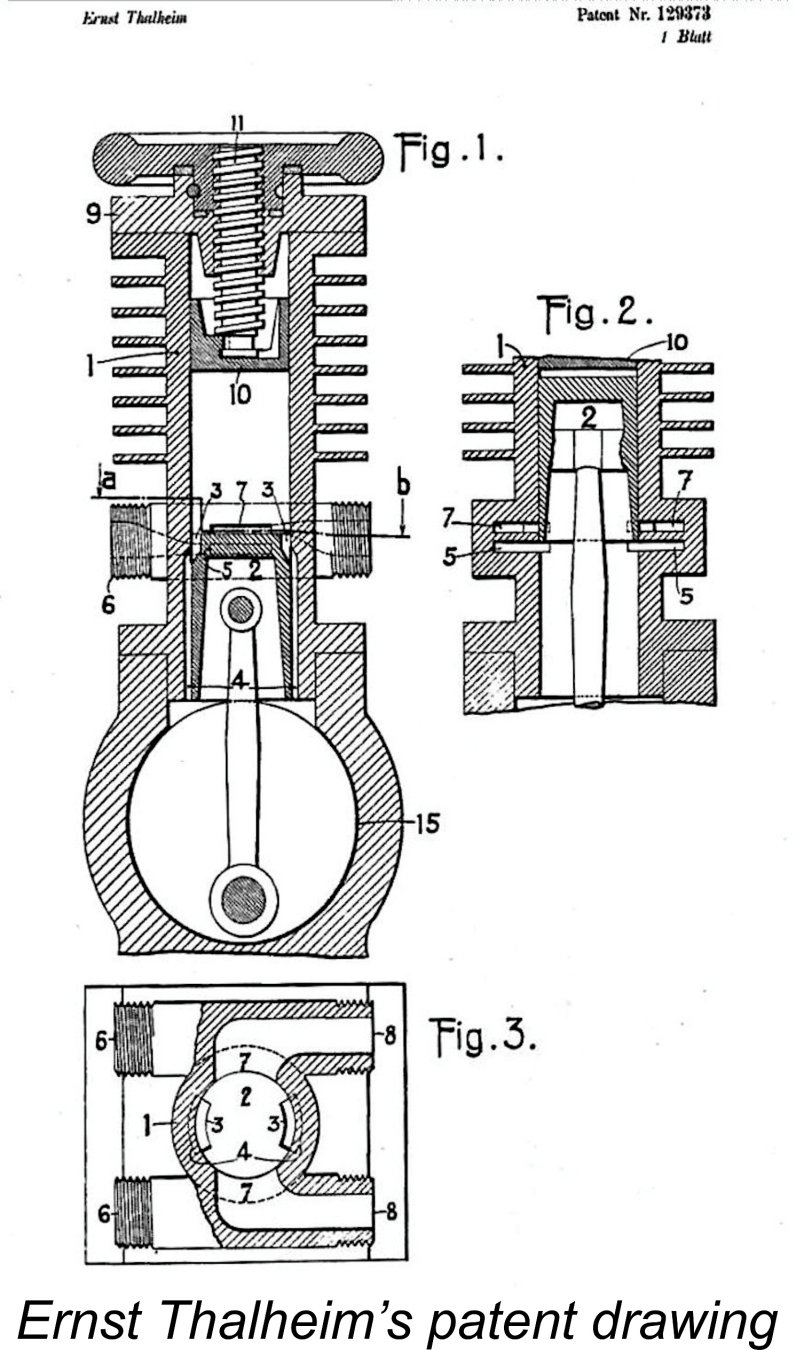

At this point, Thalheim’s creativity seems to have been re-invigorated, leading him to further refine his own engine design concept specifically for model aero applications. Assertions by some that his ETHA 1 and 2 engines dated as far back as 1938 in commercial form are only tentatively substantiated, but the engines were certainly already there when the far better-known 2 cc Dyno-1 from Klemez-Schenk arrived on the market in 1941. A test by Maris Dislers of a replica ETHA 1 diesel may be found elsewhere on this website. Despite the general European preoccupation with the conflict of WW2, news of this emerging new technology somehow filtered through to France (among other countries), setting in motion model 2-stroke diesel developments there. According to Michel Rosanoff, the model diesel concept was first unveiled in France on July 26th, 1942 by two Parisian residents, Pierre Meunier and M. Rietti. They demonstrated an example of the Swiss Dyno in front of an audience of model enthusiasts and journalists from the modelling community and the hobby media. Naturally, both French aeromodelling enthusiasts and engine constructors were greatly intrigued by this new technology, which allowed modellers to dispense with the heavy and undependable spark ignition support systems used up to that point in time. André Gladieux It’s not clear to what extent Thalheim’s patent rights had effect beyond the borders of Switzerland. Perhaps assuming that they did have such effect and that Thalheim would renew his patent beyond its initial expiry date of December 31st, 1942, some of the earliest French engines had fixed compression (which worked well enough for larger low-speed engines, as the American Drone diesels amply demonstrated) or variable compression via an eccentric crankshaft bush. Either approach would neatly circumvent the Thalheim patent. However, for whatever reason Thalheim allowed his patent to lapse. Perhaps he was making his real living from other precision engineering work or was inclined towards a fairly widespread Swiss notion that inventors should not selfishly deny their inventions to others indefinitely. The situation in France at this time was greatly complicated by the fact that much of the French homeland, including the area around Paris, was occupied by German forces during most of the war. Paris itself was occupied on June 14th, 1940, remaining under direct Nazi control until its final liberation by Allied forces on August 25th, 1944. During this unhappy 4-year period, large The ongoing German occupation did not prevent model diesel manufacture in France from really taking off in 1943. Apart from Gladieux with his Micron 5 cc design, a host of other French model diesel designs appeared more or less simultaneously during that year. These included offerings from Allouchéry, Fulgur, Jide, Marquet, Morin and STAB. It’s worth remembering that all of this activity came three years prior to the appearance of the first British production diesels – quite a head start! An interesting observation is the fact that few of these early French models displayed much Dyno influence – the French designers evidently preferred to plough their own design furrow. Another very interesting implication arising from this development is the inescapable recognition that a model engine market of some magnitude must certainly have existed in France during the occupation years. Had this not been the case, it appears inconceivable that so many new French designs would have appeared on the market in 1943 and beyond. It would seem that the German authorities had decided that giving people some freedom to pursue their personal interests would make them less resentful of the occupation.

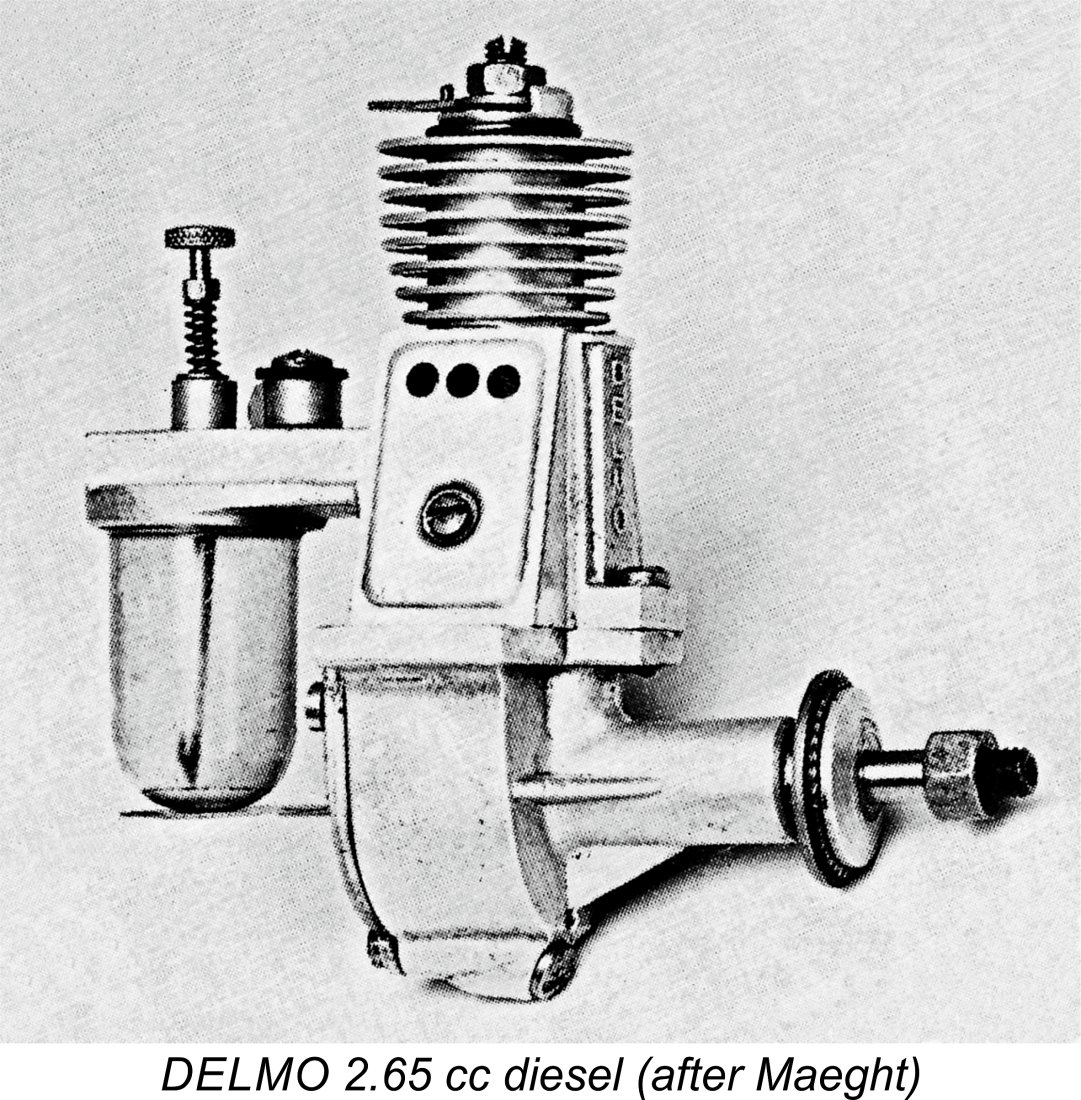

There’s little doubt that although a market for model engines must have existed in occupied France as noted earlier, any such market must surely have been somewhat constrained during the war years. However, as the war drew towards its conclusion following the August 1944 liberation of Paris, things began to move quite rapidly. Established manufacturers like Gladieux moved quickly to increase production, while new manufacturers soon emerged to join the fun. Among the latter was one Maurice Delbrel of Corbeil, a southern suburb of Paris. In 1944, Delbrel embarked upon the development of his own 2.65 cc diesel engine. This brings us to the point at which we're ready to begin our focused survey of the engines produced by Delbrel under his DELMO brand name. But before we do that, let's take a moment to reflect upon the fact that Maurice Delbrel was far more than just a talented designer and constructor of model engines. He was also an enthusiastic practical hands-on aeromodeller. Let's review a few of his achievements in that field. Maurice Delbrel - Aeromodeller

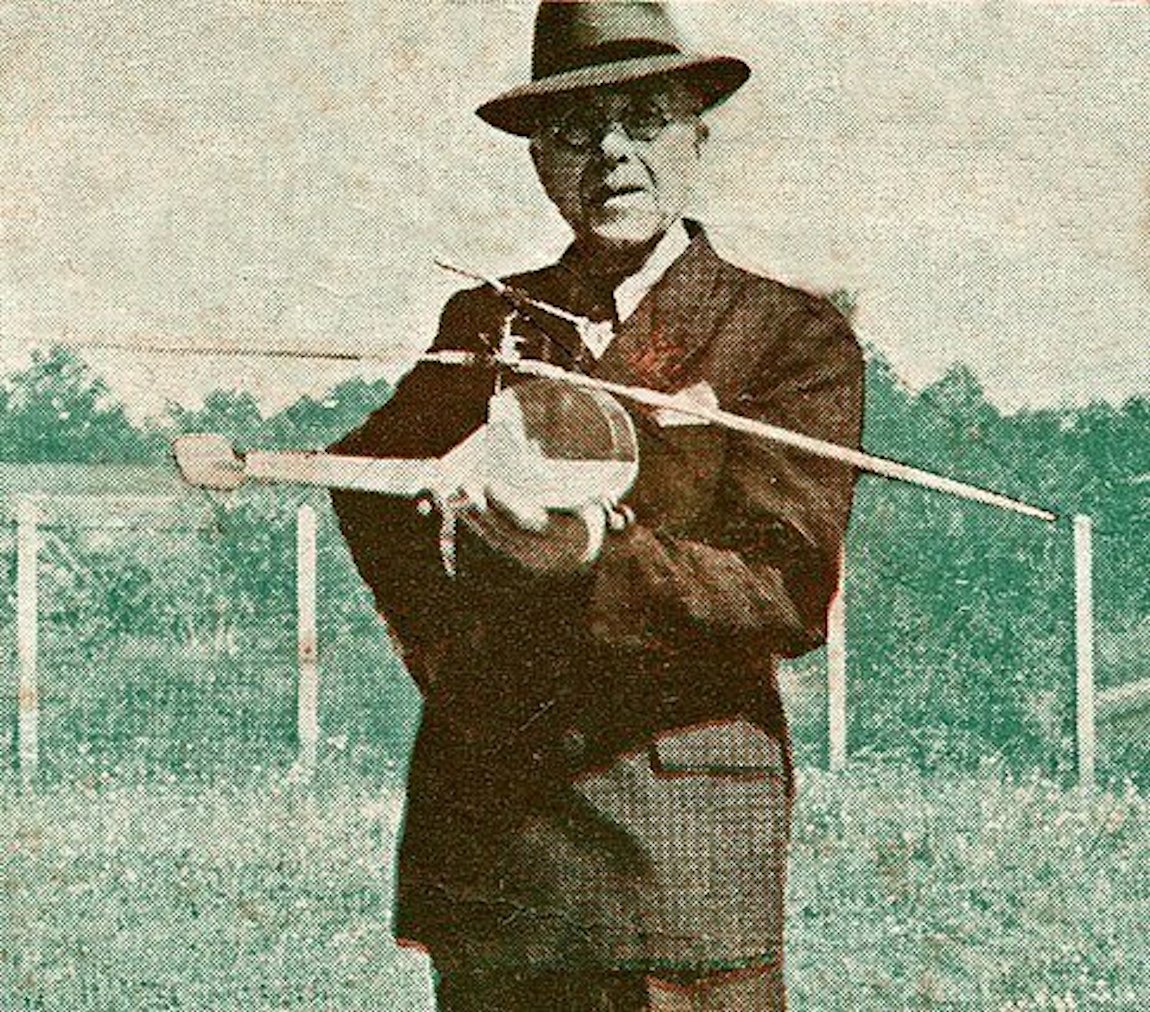

The photograph at the right was taken at the fourth such competition in 1950. It shows Delbrel with two of his models. That on the left is his "DELMO" design which belied its name by being fitted with a 0.9 cc Maraget-Météore diesel engine, while the model on the right is his "Heliplane" design which was Delbrel actually managed to win the fifth helicopter competition in 1951. He is shown in the photo at the left holding the winning model. The contest was apparently held in July 1951 at Evreux. On July 15th 1951, Delbrel established French records for both flight duration and flight distance in the engine-powered helicopter category. His model stayed aloft for 1 min. 24 sec. and covered a linear distance of 524 m. This photograph originally appeared in M.R.A. issue no. 151 for October 1951. It's clear that Delbrel was the very best-qualified kind of person to design and produce model engines - he was a skilled machinist who was also a hands-on user of his own creations. The First Model - the DELMO 2.65 cc Diesel

The first model developed by Delbrel was a 2.65 cc sideport diesel following the basic design of the Dyno but with a number of very distinctive personal touches added. This design underwent its initial testing beginning in the latter part of 1944, with actual series production commencing in the spring of 1945. It’s important for context to remember that WW2 was still ongoing at the time, although the German occupation of Paris had ended. The DELMO 2.65 cc diesel was built up around a pair of well-executed gravity die-castings of notable complexity. The lower casting incorporated the main crankcase and the bronze-bushed main bearing, while the upper casting included the cooling jacket, induction tract with integral tank mount and oil collection chambers, of which more below. These two components were held together by means of two studs with nuts at the sides and a single bolt at the front. A gasket was used at the interface to ensure a seal. Bore and stroke of the DELMO 2.65 cc diesel were 13 mm and 20 mm respectively for a calculated displacement of 2.65 cc (0.162 cuin.). The engine weighed in at a rather porky 220 gm (7.76 ounces). This was 1945, remember………

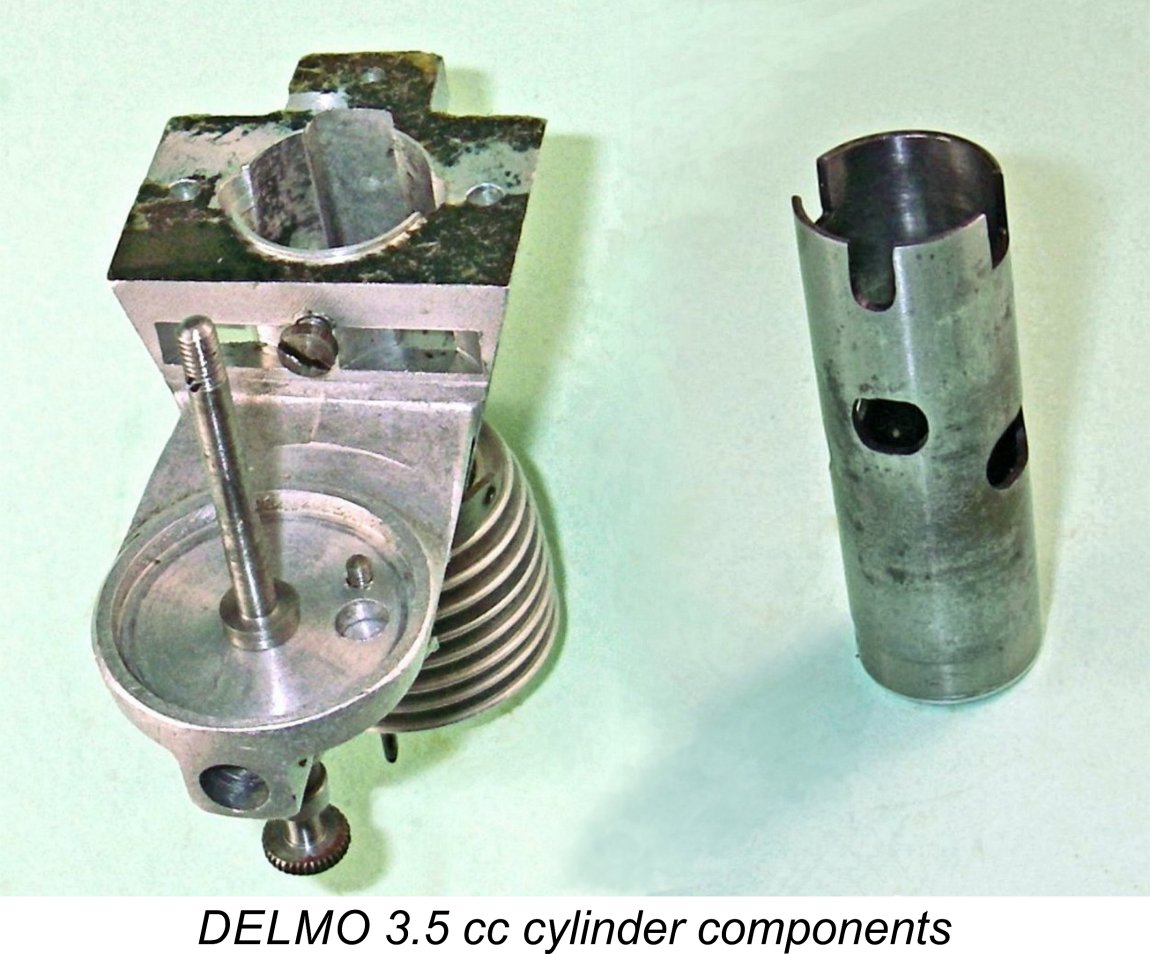

Since there was nothing to prevent the relatively loosely-fitted liner from rotating in its installation bore inside the upper cylinder casting, a slot was included at the bottom rear edge of the liner below the induction port. This slot aligned with a small screw inserted from the rear. The screw both prevented the liner from rotating in its installation bore and limited the maximum downward movement of the liner, thus in turn limiting the maximum possible compression setting. Good insurance against ham-fisted would-be operators! The attached images are of my own 3.5 cc model (see below), but the 2.65 cc version was identically constructed in all respects.

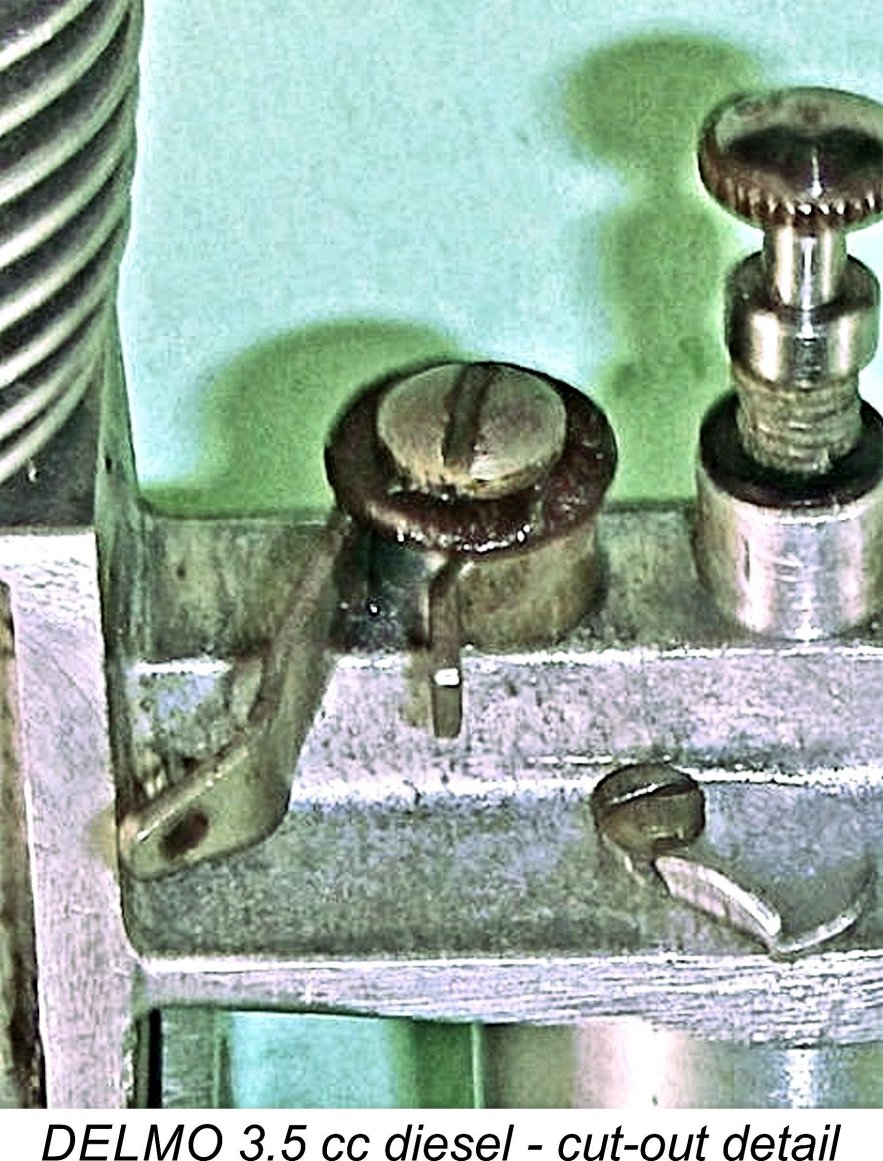

The way in which this very clever system was to be used is readily apparent. The operator slackened off the locknut and found the correct compression setting for starting by making adjustments with the comp screw alone, using a screwdriver to gain purchase. Once the appropriate compression setting for starting was established, the lock-nut could be used to secure the lever in a position which allowed some “headroom” in either direction. The lever position could be finalized following the completion of several test runs. It could also be very easily changed if different conditions made this necessary. Another clever design feature! The final touch was the provision of a steel wire circlip which was located in a groove at the top of the cylinder head and engaged with the compression lever to create the required resistance to turning during operation. The loose fit of the liner in the cooling jacket would necessitate such a measure - the engine would never retain its compression settings otherwise.

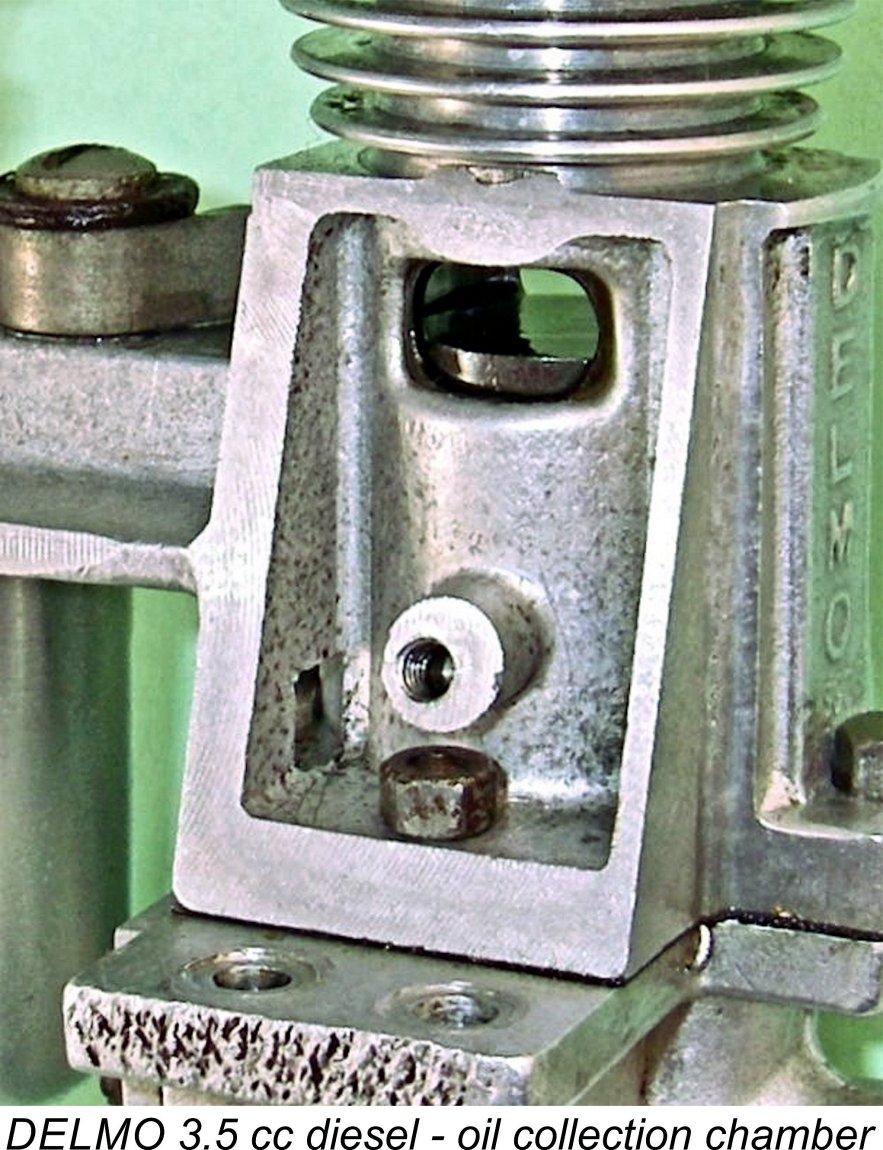

Another highly individualistic feature was the provision of a pair of oil collection chambers on either side of the engine at and below exhaust port level. These were intended to catch much of the excess oil discharged from the exhaust ports during operation. They drained through two openings at the rear just above the backplate, thus keeping much of the oil out of the slipstream where it would be dispersed all over both model and operator. The downside would have been the tendency for oil to accumulate inside the model’s fuselage. Exhaust gas was discharged through three holes drilled in each of the two detachable cover plates which sealed these chambers. Quite apart from their oil-collection function, one would expect these chambers to provide a degree of effective silencing of the exhaust note. Another neat touch was the provision of a crankcase drain plug at the base of the main crankcase. This faced forward for easy access when the engine was mounted in the model - a thoughtful arrangement. It is plainly visible in a number of the attached images.

As an alternative, Delbrel used a supplementary air intake located between the venturi throat and the cylinder induction port. The idea was that the opening of this extra intake would lean out the mixture by reducing suction, causing the engine to first slow down and then stop. This more progressive shut-down would lessen the probability of the model stalling at shut-down. We'll have a chance to test this theory later. I hope I’ve shown that the DEMO 2.65 cc diesel was a highly individualistic design which did great credit to Maurice Delbrel’s ability to “think outside the box”. In all other respects, the engine was a fairly typical sideport diesel of its day. The flat-topped cast iron piston drove the crankshaft through a steel conrod (although this was changed to aluminium alloy on later models). The one-piece steel crankshaft featured a plain unbalanced crankdisc. Its main journal ran in a well-fitted bronze bushing, while the steel prop driver was very securely keyed by a square section of shaft at the front. A classy-looking aluminium alloy spinner nut completed the shaft assembly. At the rear, the externally-threaded needle valve was tensioned with a coil spring. The tank on the original engines was made of clear translucent material to allow a visual check on the fuel level prior to launch. However, this tank must have proved to be adversely affected by fuel over the longer term because many owners replaced this tank with a metal one for actual service. Initial Marketing Strategy

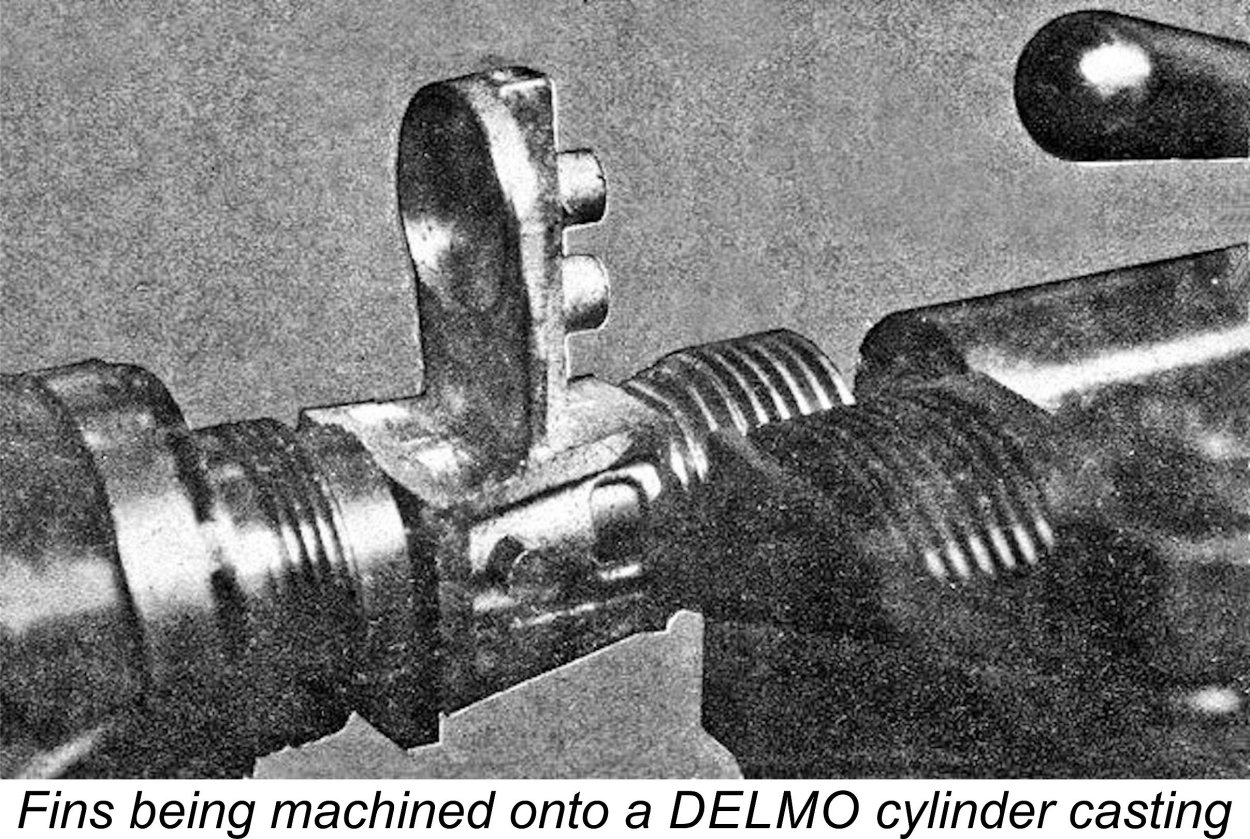

As stated earlier, production of the DELMO 2.65 cc diesel commenced in the spring of 1945. Production numbers were somewhat restricted at first due to the adverse economic conditions prevailing in France immediately following the conclusion of WW2. The engines were both extremely well made and highly dependable. Moreover, they reportedly delivered excellent flight performances in the hands of such French experts as Ducrot, Guillemard and Chabot. However, performance was relatively unspectacular for an engine of this bulk and weight. The manufacturer claimed an output of only 0.08 BHP @ 5,000 rpm for his 250 gm unit. Despite any such limitations, Delbrel was evidently able to sell his entire relatively small production because the pent-up post-war demand for model engines in France still exceeded the combined production figures for all French manufacturers combined. He seems to have tooled up for series production in a very practical manner, as evidenced by the attached image showing the cooling fins being formed on a cylinder casting using a gang cutter.

“La Source des Inventions” was one of Paris’s oldest and most famous scientific supply houses, having opened its doors in 1907. It was located on Strasbourg Boulevard in Paris. Generations of young people with scientific minds dreamed of owning some of the products sold by this company - if I'd lived in Paris at the time, I'd have been one of them! Model engines were among the early products sold by “La Source”, with steam engines being offered from 1908 onwards. These were joined by compressed air engines in 1920 and finally by petrol engines in 1938. If I had been around at the time, this store would have appeared to be a real-life Aladdin's Cave - you'd never have got me out of there!

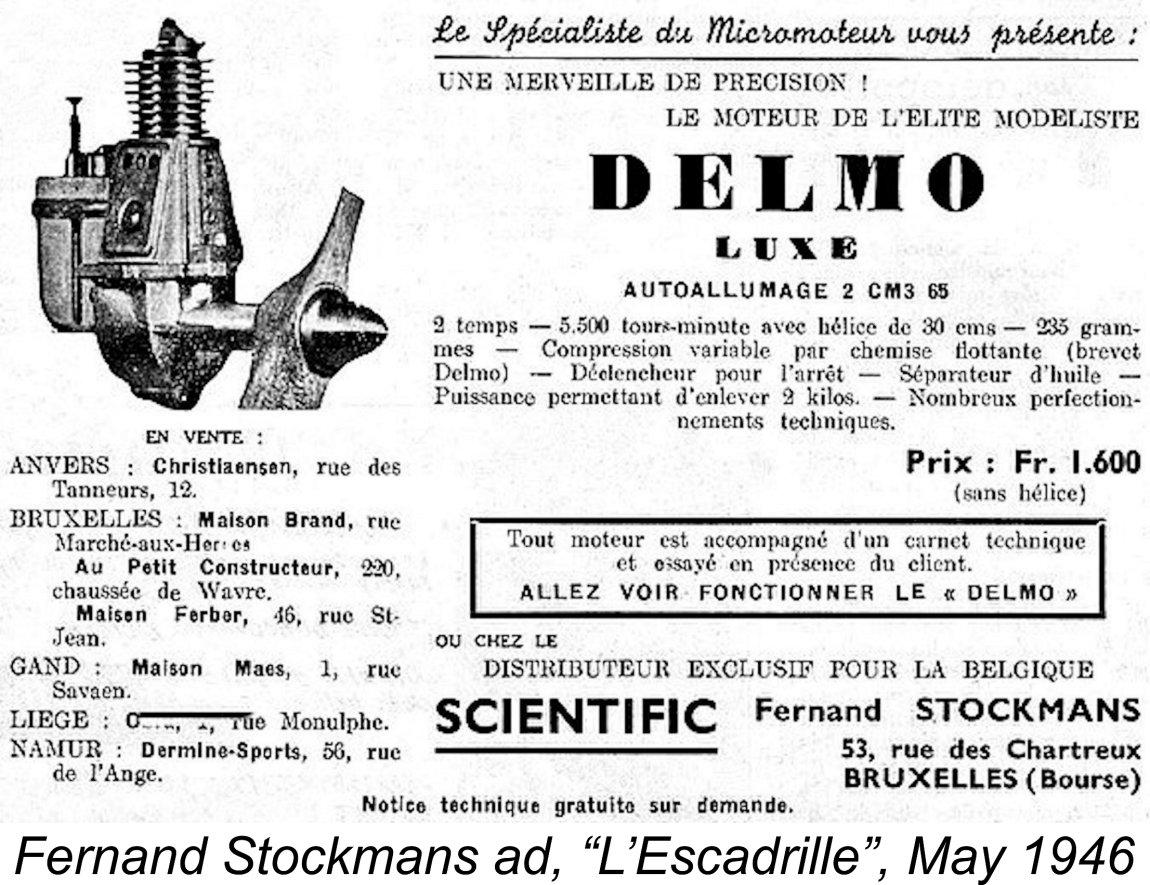

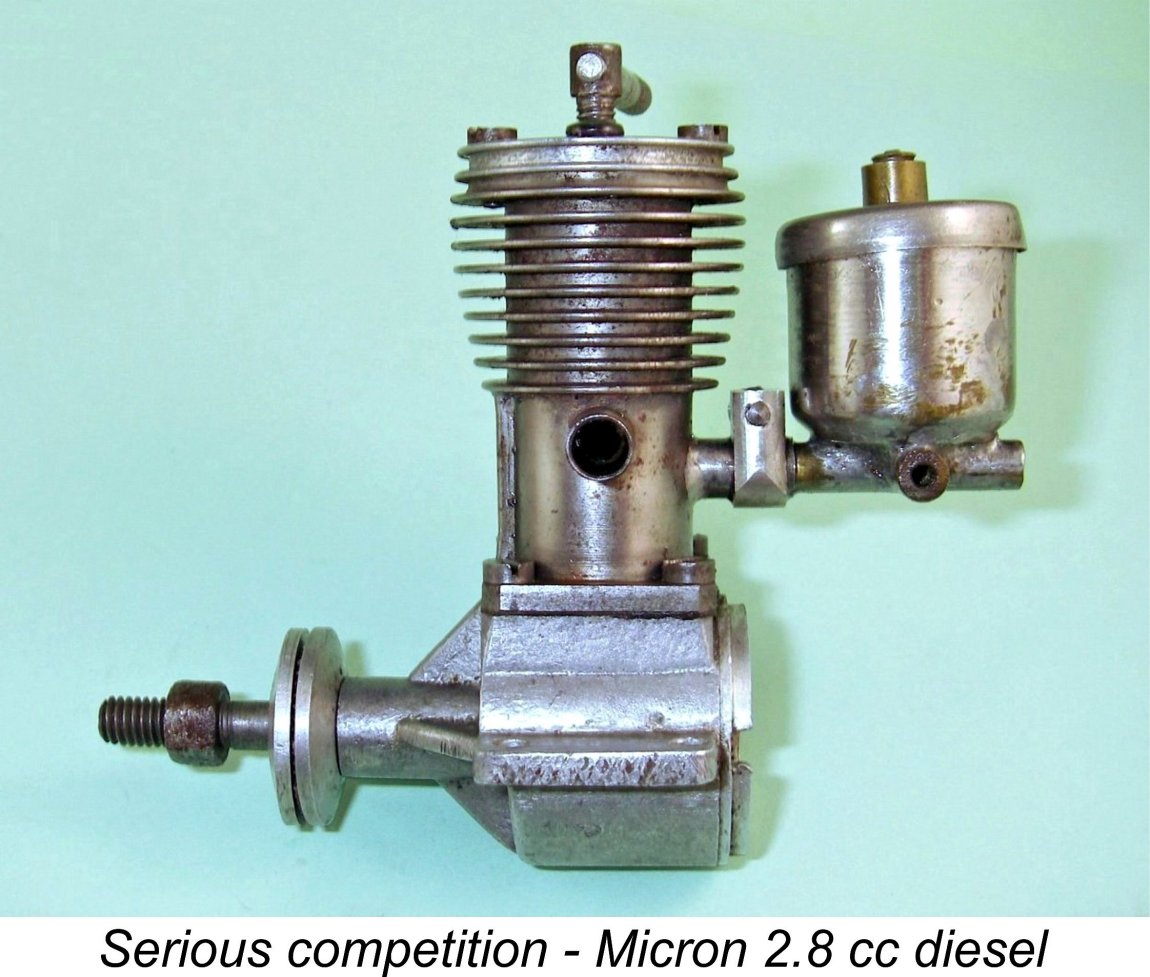

Incidentally, we'll be hearing from M.R.A. magazine again throughout this article. Its full name translates to "The Model Airplane". It seems to have been in effect the French equivalent of "Aeromodeller". It was still in publication as of the late 1990's. Although export opportunities were very limited at the time, Delbrel did negotiate a distribution agreement with the Belgian firm of Fernand Stockmans Scientific of 53 Rue des Chartreux in Brussels. This firm was advertising the DELMO 2.65 cc diesel as of May 1946 in the pages of Belgium's "L'Escadrille" magazine. A number of dealers were cited in various Belgian locations. In addition to the aero version of the DELMO, a water-cooled model boat variant was marketed from the start. This was most likely inspired by the success of the earlier R.E.A. 5 cc spark ignition marine model. It was the first French model marine diesel engine and may have been one of the first such engines in the world. It went Unfortunately, the DELMO engines continued to trail their competitors both in terms of power-to-weight ratio and price. As of the summer of 1946, “La Source” was selling the DELMO 2.65 cc models at 2,700 francs for the aero version and 2,900 francs for the marine version. By comparison, the Micron 2.8 cc was priced at 2,500 francs and the Ouragan 3.36 cc sold for 2,100 francs. The high price of the DELMO models accurately reflected their quality, but their relative price was a sales imediment nonetheless, at least in the context of the French market. The prevailing exchange rates at the time were approximately 260 francs to the US dollar and 780 francs to the British pound. The cost of the aero version of the DELMO 2.65 was thus the equivalent of some US$10.38 or £3.46 - quite competitive if international trading restrictions did not preclude such activity at the time, even with shipping costs thrown in. No wonder that a fair number of servicemen returning to England or the USA snapped up a few examples of the various French models on their home-bound way through Paris! In terms of its power-to-weight ratio, the DELMO 2.65 cc diesel's claimed output of only 0.08 BHP @ 5,000 rpm for its 250 gm weight did not compare favourably with the 0.09 BHP developed by the 140 gm Micron 2.8 cc model or the output of 0.11 BHP claimed by the Fargeas brothers for their for their 215 gm Ouragan model of 3.36 cc displacement. Sooner or later, something would have to be done about this imbalance, particularly since in the absence of any export opportunities Delbrel was competing directly with his lower-priced competitors in the French domestic market. It was inevitable that he would eventually have to react to this situation if he wished to remain in business. The Next Step - the DELMO 3.5 cc Model

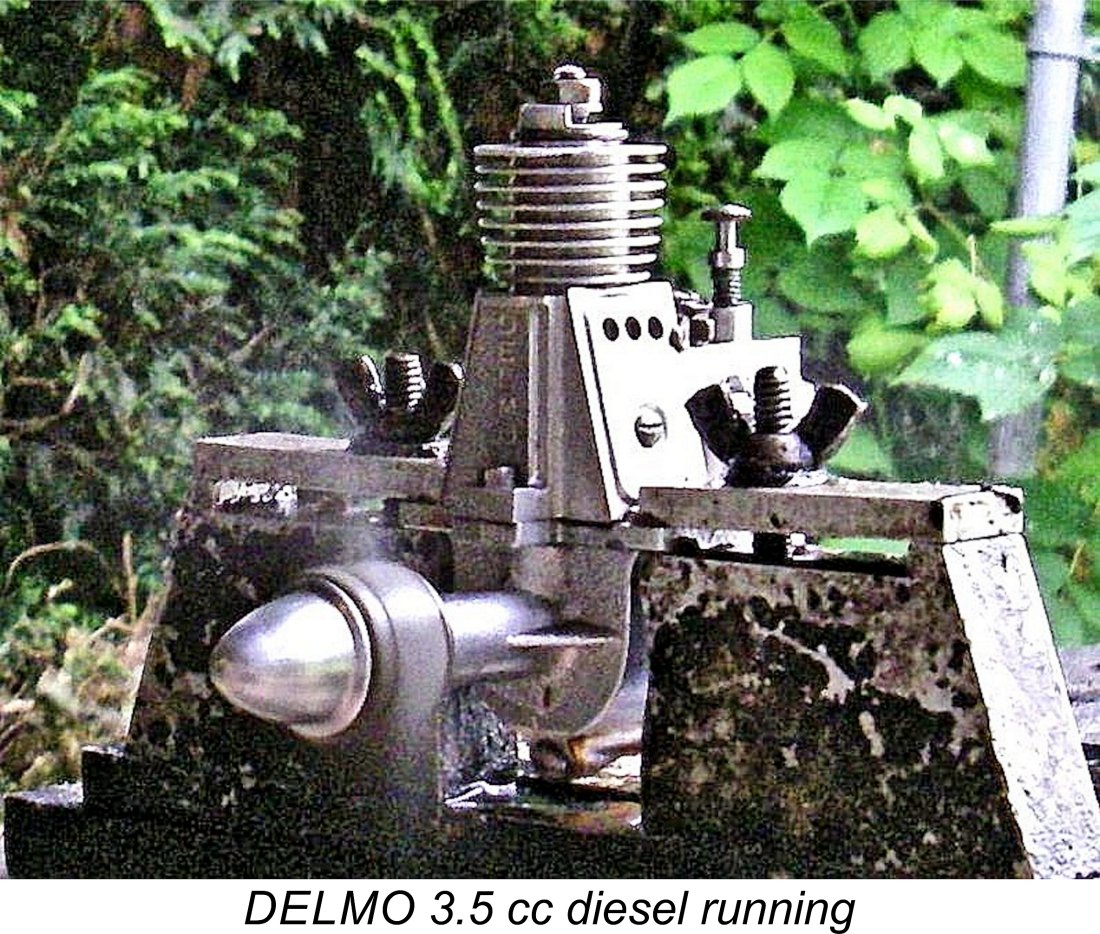

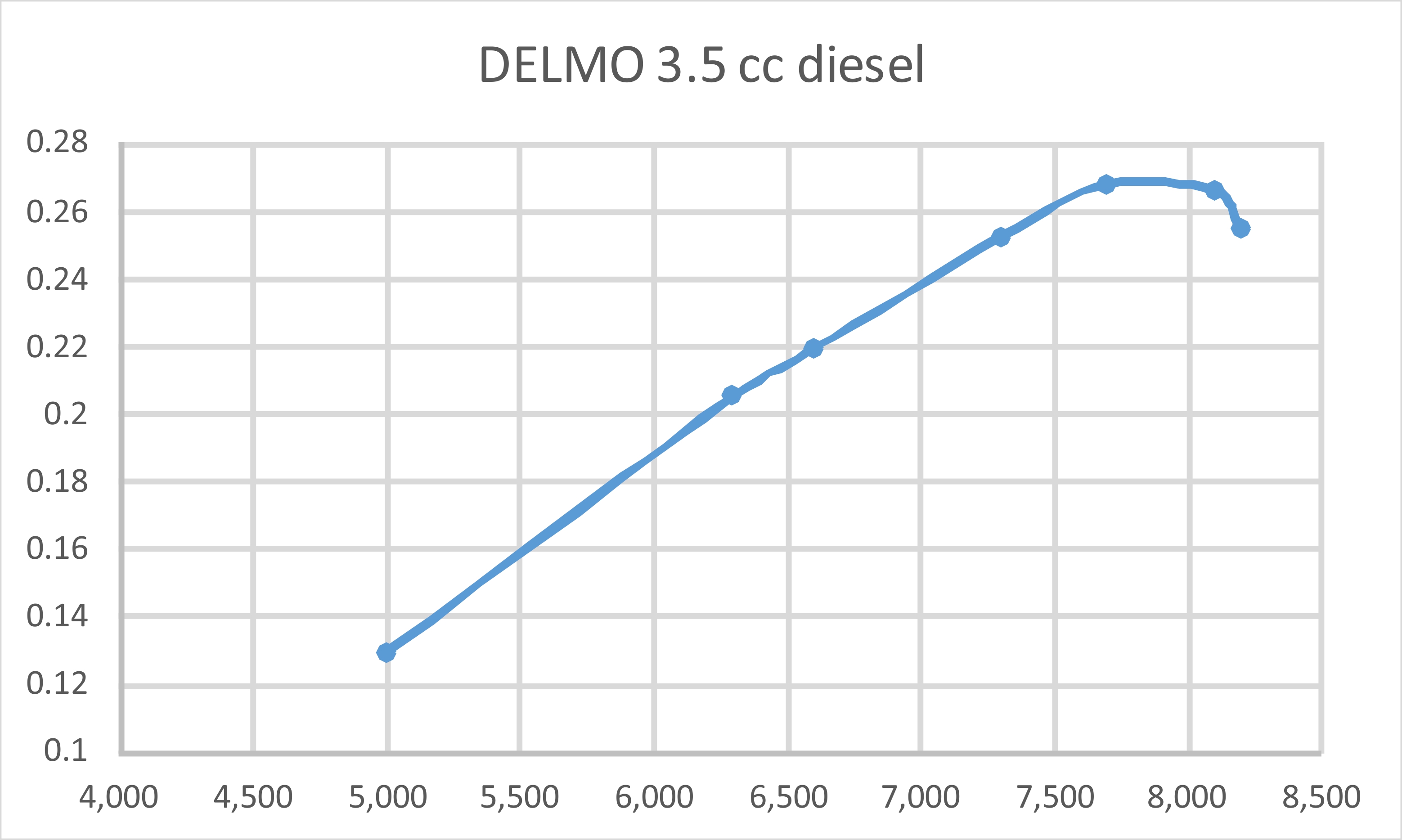

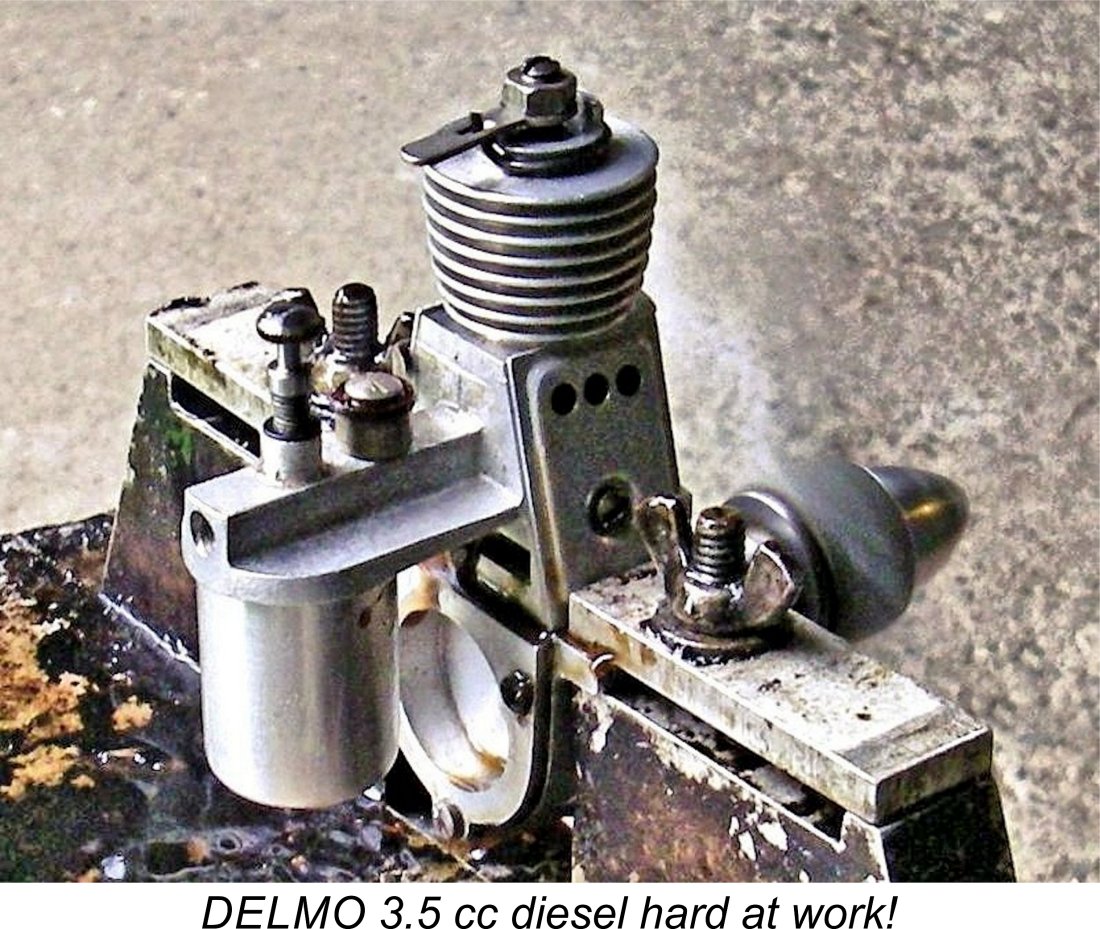

The changes resulted in only a very modest increase in weight from 220 gm to a checked 232 gm. However, the manufacturer claimed a very significantly increased power output to 0.15 BHP @ 5,000 rpm. The engine was stated to be matched to a 30 cm (11.8 in.) diameter propeller of unspecified pitch. A modern APC 12x8 would absorb around 0.130 BHP at that speed, making it appear not unlikely that a somewhat “slower” rendition of this prop size was more or less the correct prop for the engine. Apart from the increased bore, the construction of the rest of the engine followed that of the original 2.65 cc unit exactly. There is thus no need to repeat the earlier description here. My illustrated example of the DELMO 3.5 cc model has a metal tank fitted (like many others) but is otherwise complete and original. Its quality is beyond reproach. Being fortunate enough to have this very nice example of the DELMO 3.5 cc model on hand for examination and test, I had the opportunity to check the manufacturer’s performance claim at first hand. Let’s get right to it! The DELMO 3.5 cc Diesel on Test Although it has clearly seen considerable use in the past, my example of the DELMO 3.5 cc diesel remains in excellent cosmetic and mechanical condition, also seemingly being unmodified in any way. Consequently, it should yield results which are entirely representative of the engine’s true capabilities. Looking back through the log books which I've kept since the 1960’s, I find that I acquired this engine way back in 1987! I ran it briefly at that time using an 11x6 prop. Unfortunately, I didn’t record the speed at which the engine turned this airscrew, merely noting that it started very easily and ran well. I was therefore beginning from scratch on the present occasion. As noted above, the manufacturer appears to have recommended a 12 in. dia. prop of unspecified pitch. Based on the claimed peak output and peaking speed, I decided to begin with a 12x8 APC and see where things went from there. I used an undoped fuel containing 35% ether, 35% kerosene and 30% castor oil. Most early sideport diesels will run very well on such a brew, whch is also very kind to the bore and bearings.

I began with the compression screw lock-nut slackened off, making compression adjustments with a screwdriver which engaged with the slot on the top of the comp screw. Turning the screw down by small increments while flicking, I got to a point at which the engine began to fire. I them tightened the lock-nut so that further compression increases could be applied using the compression control lever. This soon produced a start. It turned out that a port prime was more or less essential for starting. Choking only resulted in a flooded crankcase. The best approach turned out to be to administer no more than two choked flicks and then prime the exhaust. This never failed to result in a start within two or three flicks. I'd rate the engine as an excellent starter. Once running, the DELMO ran absolutely smoothly without missing a beat. Both controls were very responsive and held their settings perfectly. There was also no tendency to sag at any time. Suction appeared to be very good indeed - despite the unusually tall tank, the motor invariably ran the tank out cleanly with very little apparent leaning-out as the fuel level in the tank went down. The one thing that I did notice was the fact that the run-time on a tank seemed to be a little on the short side - the engine appeared to be relatively thirsty. The oil collection chambers worked quite well. Although some oil was still ejected through the holes in the cover plates, much of it ended up draining out of the cylinder base openings at the rear, thus not entering the slipstream in the form of spray. The DELMO turned the APC 12x8 prop at a dead smooth 5,000 rpm - about what I had expected. What I did not expect was the degree to which the engine's output continued to increase as speeds went up! I was frankly astonished by the unexpected performance of this engine. Check out the following data!

I can't help the above figures - they're what I actually saw on test! They're also mutually consistent with one another. Even so, I went back and re-tested a few of the props just to be certain that I hadn't been misreading the tach - same results. A very serious level of torque on display here. I'm happy to repeat the test for any doubter who cares to drop by in the future - the DELMO isn't going anywhere any time soon!

It's pretty clear that in addition to increasing the displacement of the original 2.65 cc model, Maurice Delbrel must have incorporated some very effective internal design changes. The very large cylinder ports doubtless played a part here. There may also have been some port timing amendments The one fly in the ointment turned out to be the cut-out, which was very uncertain in operation. With the mixture fully leaned out it was reasonably effective, causing the engine to slow down and stop over a period of several seconds, just as the designer apparently intended. However, with the needle set even just a little rich, all that the cut-out did was speed the engine up by leaning out the mixture! I would have preferred something a little more positive in action. Even so, with its extremely easy starting, smooth running and outstanding performance by the standards of its day, it's no wonder that the DELMO acquired such a solid reputation among French modellers! An 11x6 prop would appear to be a good choice for free flight, with a fat 10x8 for control line. Further DELMO Developments

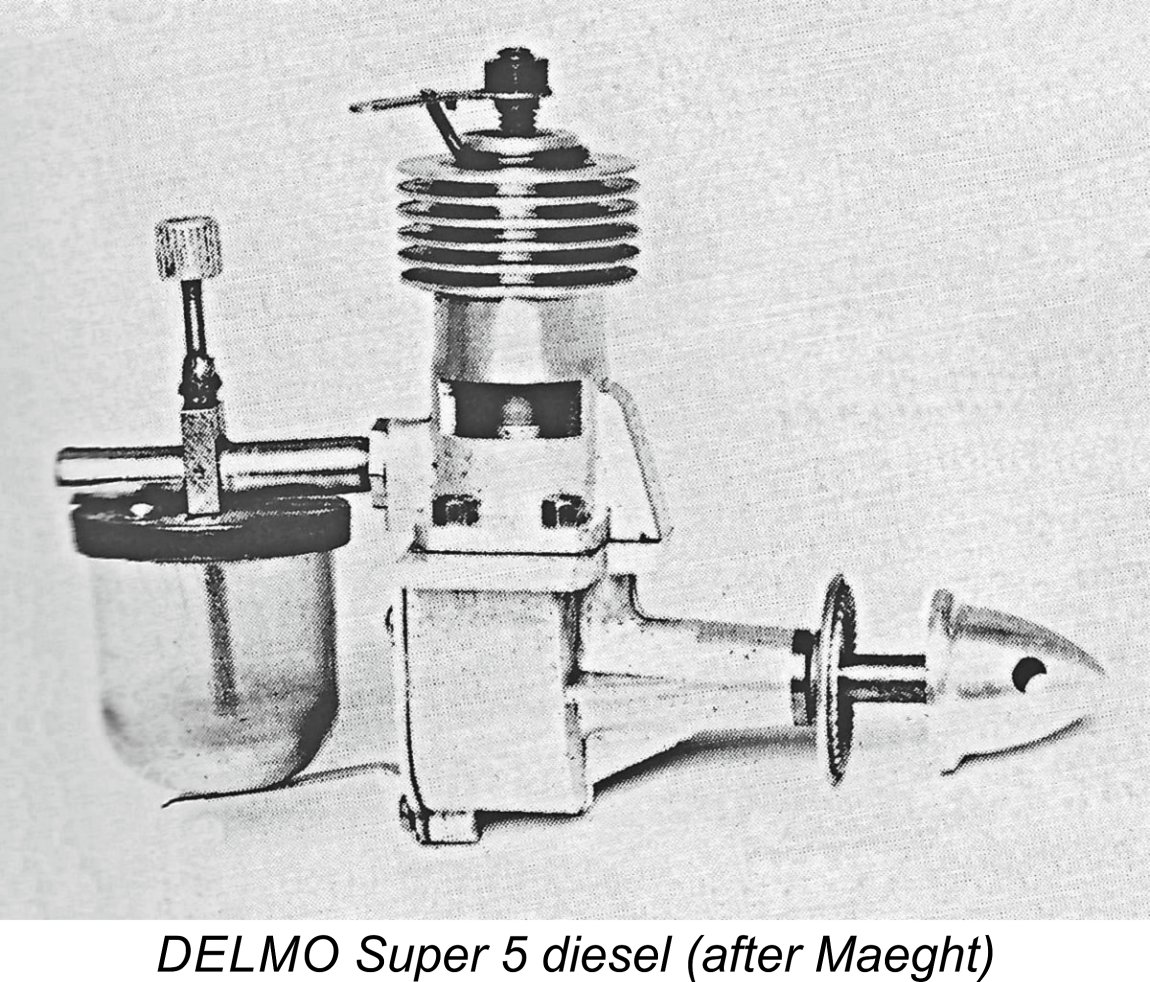

Perhaps the most commonly-voiced criticism of these engines was their excessive bulk and weight. To cite just one comparison, the DELMO 3.5 cc model was some 80 gm heavier than the competing Micron 2.8 cc design. It was noted that at least part of this excessive weight was due to the inclusion of such features as the two oil collection chambers, which many observers considered to be entirely superfluous. By the end of 1946 Delbrel had rightly concluded that it was time to go back to the drawing board and review his entire design, the primary objective being to achieve an enhanced power-to-weight ratio. Presumably for economic reasons he chose to retain the same basic crankcase casting, but everything else was on the table. The new model which finally resulted from these deliberations was the DELMO Super 5 diesel which first appeared in the late spring of 1947.

Along with these changes, the cylinder porting was substantially redesigned. In addition, the boss at the base of the crankcase was machined off - clearly the drain plug was no longer considered necessary. The engine now had a more “classic” look than it had formerly, also being more compact. In fact, the slimming down of the upper casting left the main crankcase casting looking too large! Delbrel decided to take advantage of this by increasing the engine’s displacement to a full 5 cc. He did so in part by increasing the stroke from 20 mm to 22 mm, which required that the internal diameter of the crankcase be increased by the same amount. This reduced the crankcase wall thickness from 3 mm down to only 2 mm. The bore was also increased from 15 mm to 17 mm, the upper casting being reworked to suit. The two main castings were now attached to each other with four fasteners instead of the former three.

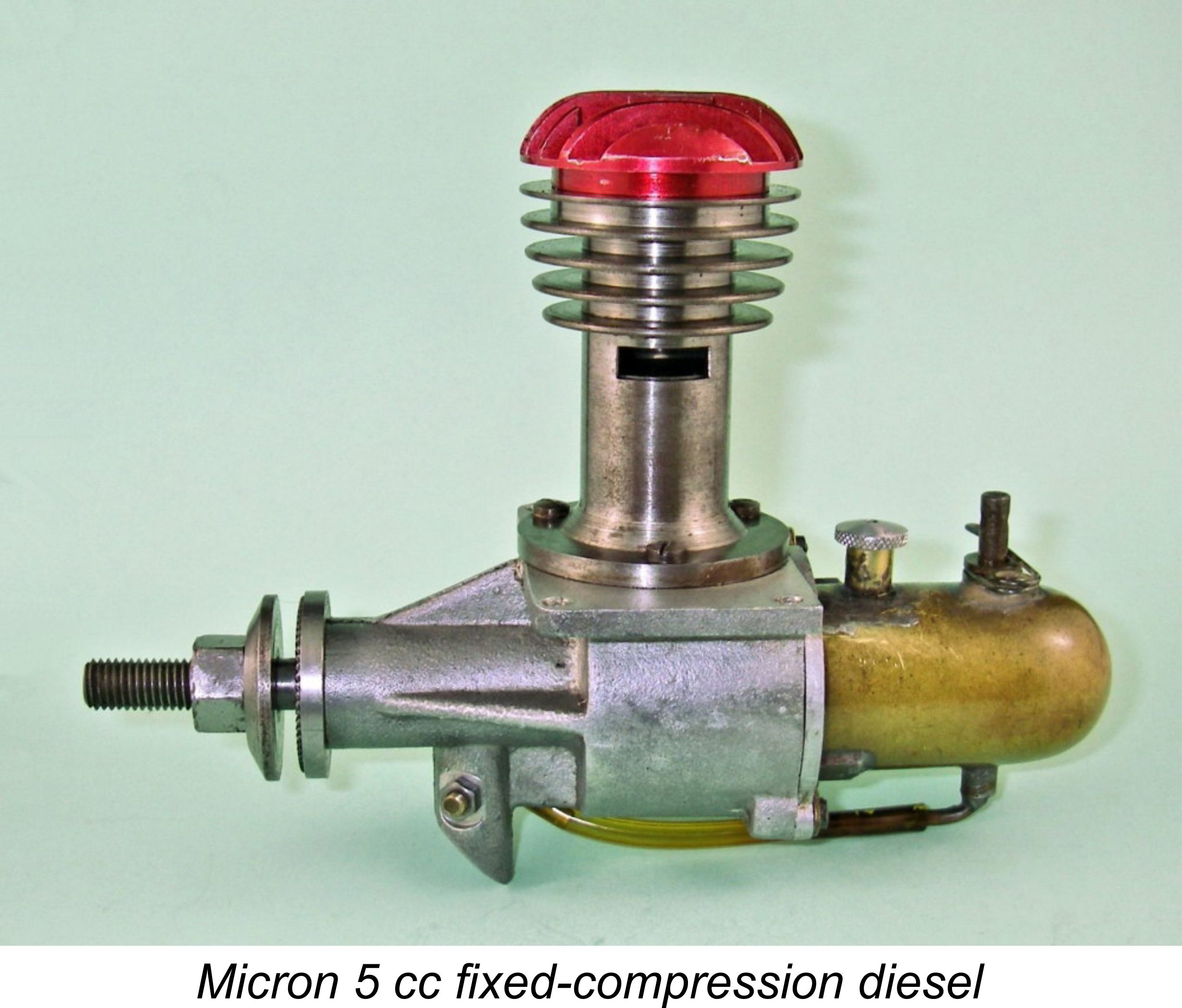

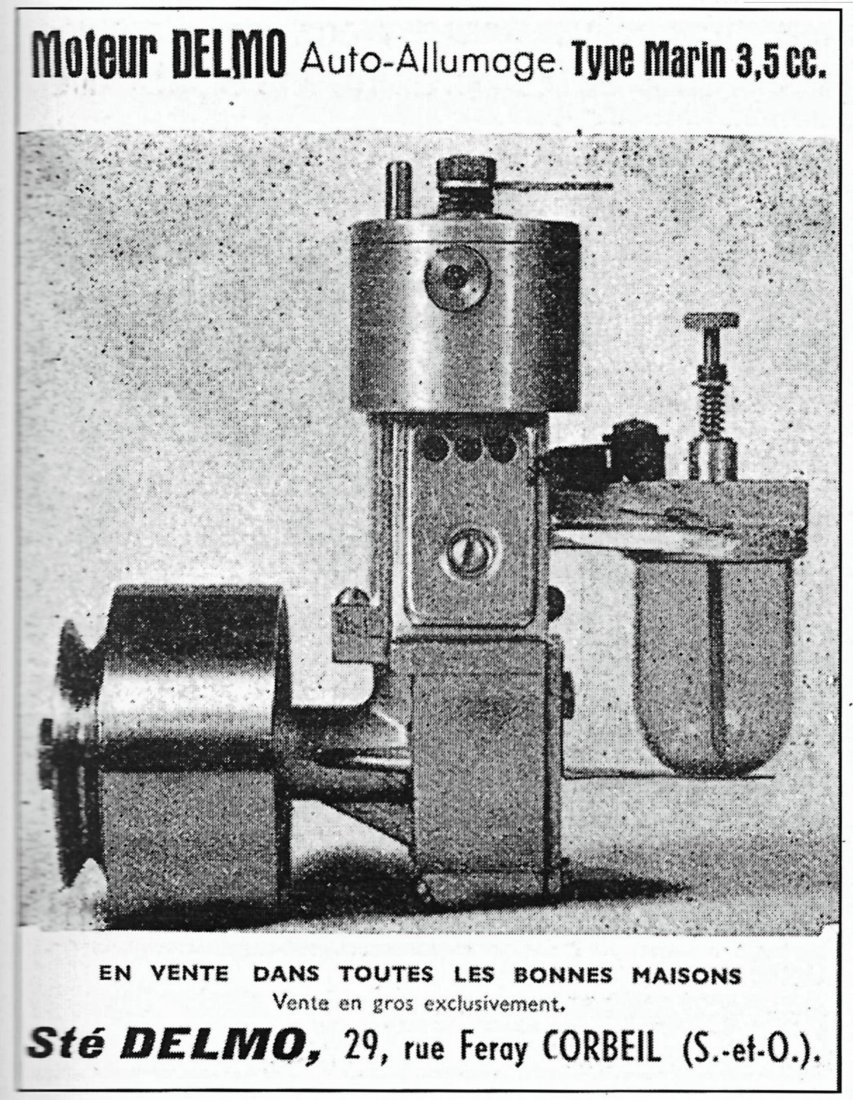

One would expect vibration from this unit to be pretty significant! This was apparently not viewed as a problem in free flight service because the operating time on each flight was short, but in control line applications things were different. The engine runs were far longer and the excessive vibration inevitably led to faster wear. A return was made to a steel conrod to better absorb the elevated reciprocating stresses. The fuel supply system was also slimmed down considerably, while the former cut-out arrangement was abandoned. All of these modifications reduced the weight of the engine to 175 gm (6.17 ounces), 57 gm less than the checked weight of the 3.5 cc model. This may not sound like much, but it’s important to remember that we are now speaking of a 5 cc engine which was competing in a different competition category with other 5 cc engines. One of the most successful 5 cc engines of the day was the previously-mentioned Micron 5 cc diesel, and that model weighed 180 gm, slightly more than the competing DELMO. Moreover, the Super 5 was found on test to develop some 0.270 BHP @ 9,000 rpm, now using a 25 cm (9.8 in.) diameter airscrew, thus outperforming its Micron competitor. In fact, Delbrel’s all-new design had the best power-to-weight ratio of any French 5 cc unit then on the market! Quite a turn-around, even if it had taken a switch to a different competition category to achieve it! As previously mentioned, the new model appeared in the late spring of 1947, replacing the former 3.5 cc model. For a while it was the go-to choice for discerning French modellers looking for a powerful and well-made 5 cc engine. Unfortunately it was also the most expensive French 5 cc diesel on the market. In an economic environment which was still recovering from WW2, this was a significant factor in influencing peoples’ buying decisions. The DELMO Super 5 sold for 2,700 francs at “La Source des Inventions”, which also offered the Like its smaller predecessors, the Super 5 was initially marketed with a lightweight clear plastic fuel tank. However, a tankless version more suitable for control line use was quickly introduced. Oddly enough, a water-cooled marine version of the 5 cc model didn’t appear until 1948, with the 3.5 cc marine model continuing in production. This was presumably a strategy intended to use up 3.5 cc components already on hand. Even when a marine version of the Super 5 finally appeared in 1948, the 3.5 cc marine model remained on offer as an alternative. The attached advertisement from M.R.A. magazine is one of the very few advertisements placed by Delbrel himself during his career as a model engine manufacturer. Media coverage of the new model was relatively weak, largely due to the manufacturer's general policy of not placing his own advertisements in the modelling media of the day - the attached 3.5 cc marine diesel advert is a rare exception. This was presumably for economic reasons. Delbrel seems to have been relying on the distributors such as “La Source” to promote his engines for him. Indeed, their listings constitute our best source of information today in the absence of any manufacturer's advertisements or media commentary.

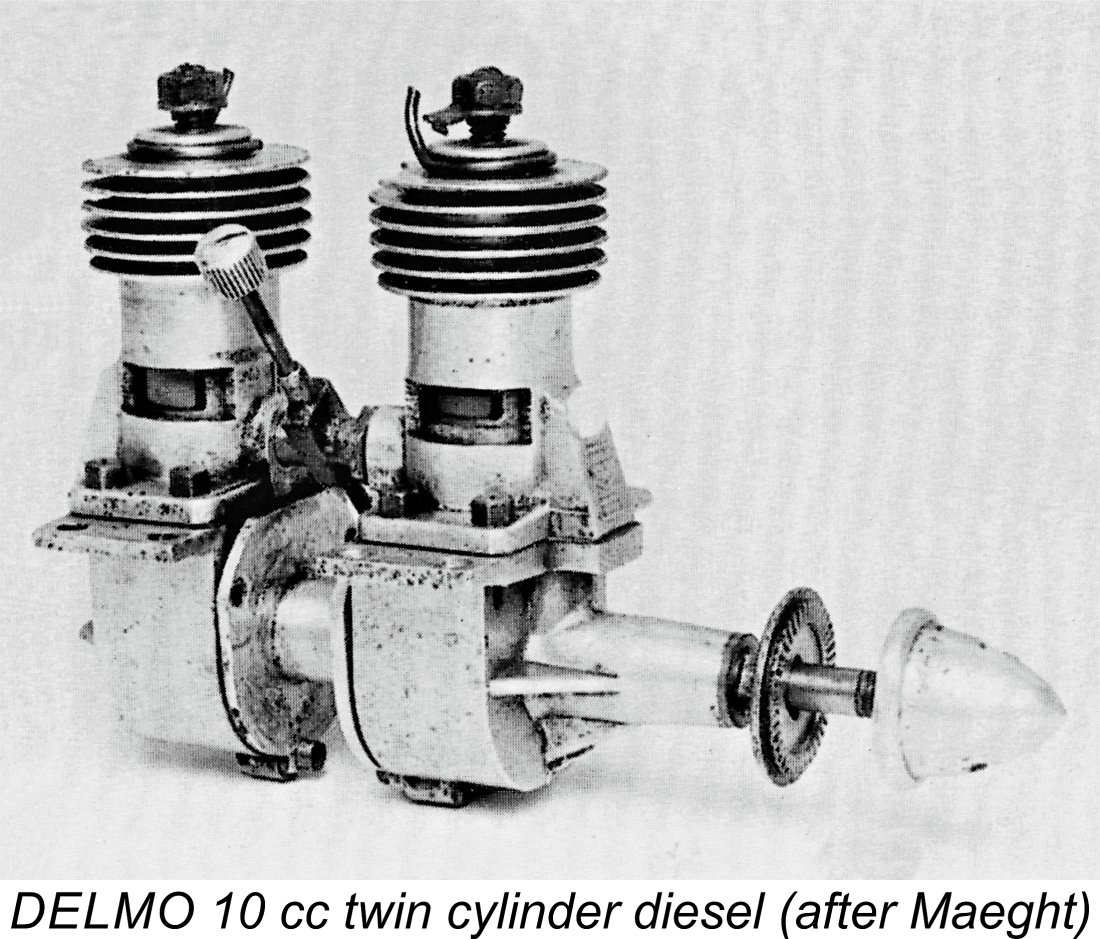

Preliminary tests revealed that the engine ran well, with relatively little vibration. We might expect this given the alternate firing arrangement adopted. On the strength of these results, a 10 cc version of the same basic design was constructed using twinned Super 5 components. The 10 cc model weighed 400 gm (14.10 ounces). A published report on this engine by Jaques Morisset, one of the leading French model engine commentators of the day, appeared in the March 6th, 1948 issue of the periodical “Les Ailes” (Wings). Morisset judged the engine to be an easy starter with excellent needle valve control response and very low levels of vibration. He found the establishment of optimum compression settings in both cylinders to be perfectly straightforward. Using a fuel consisting of 50% ether and 50% oil, the engine reportedly On the strength of this favorable test, the twin was soon put into production. Initially only the 10 cc model was offered. Again, this engine was not advertised by the manufacturer - we are forced to rely on the advertisements from “La Source des Inventions” for our information. “La Source” seems to have been the main distributor of the DELMO engines all along. Sales of the twin were evidently pretty slow. This cannot be viewed as a surprise when we consider that the 10 cc twin initially sold for a whopping 8,560 francs - a ton of money in the context of the prevailing economic conditions in France. For context, the Micron 10 cc model sold for 3,200 francs, while the R.E.A. 10 cc offering carried a price tag of 2,995 francs. Moreover, the DELMO twin soon acquired a new challenger in the form of the Micron 60, which immediately became the most powerful French engine while also being both lighter and easier to use than the DELMO. Delbrel carried on regardless, adding the original 7 cc version of the DELMO twin to the range in 1950 alongside the 10 cc twin and the Super 49, of which more below. By this time, both models of the twin sold for the same price of 10,180 francs. The Crowning Achievement - the DELMO Super 49 As of 1948, control line flying was becoming increasingly popular in France. It had first reached France in 1946 but had taken a few years to catch on. The most popular category at the outset was speed - people were drawn to the opportunity to operate models at hitherto-impractical speeds under full restraint and control.

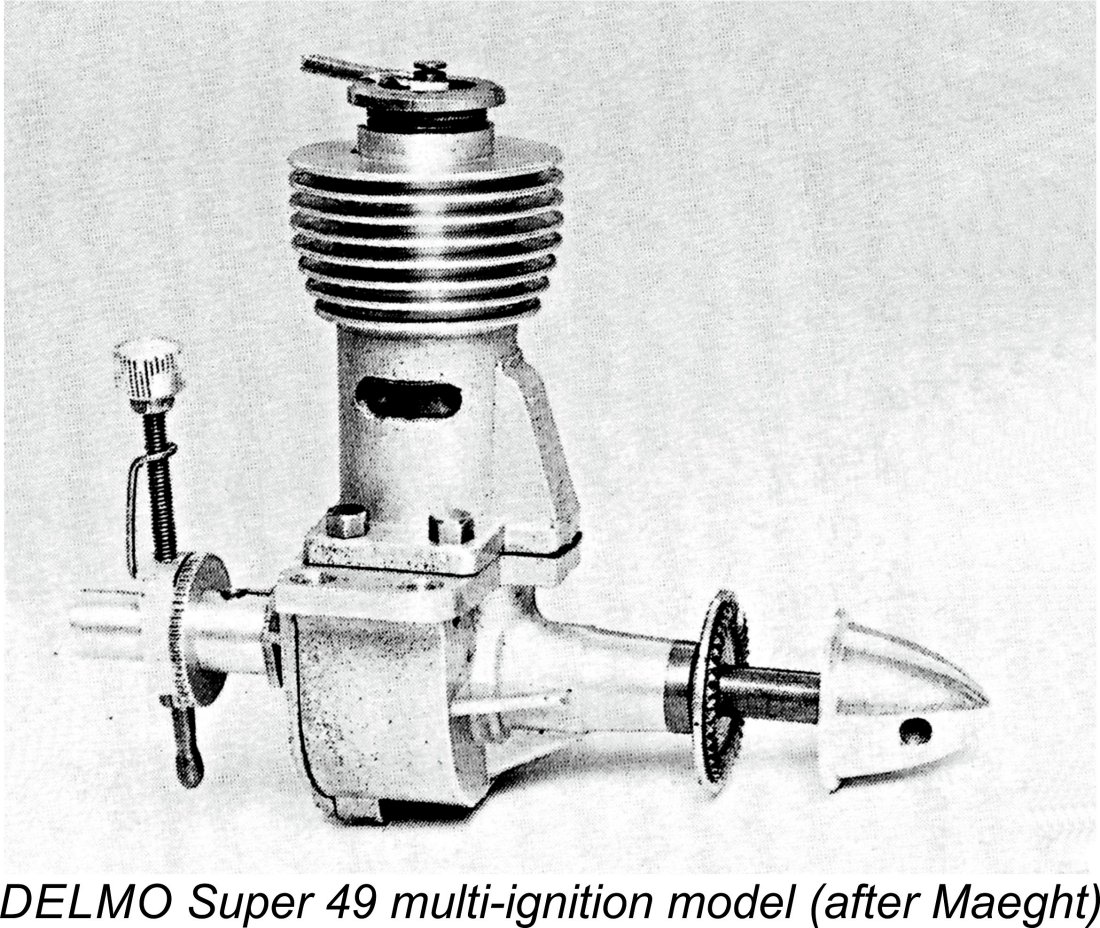

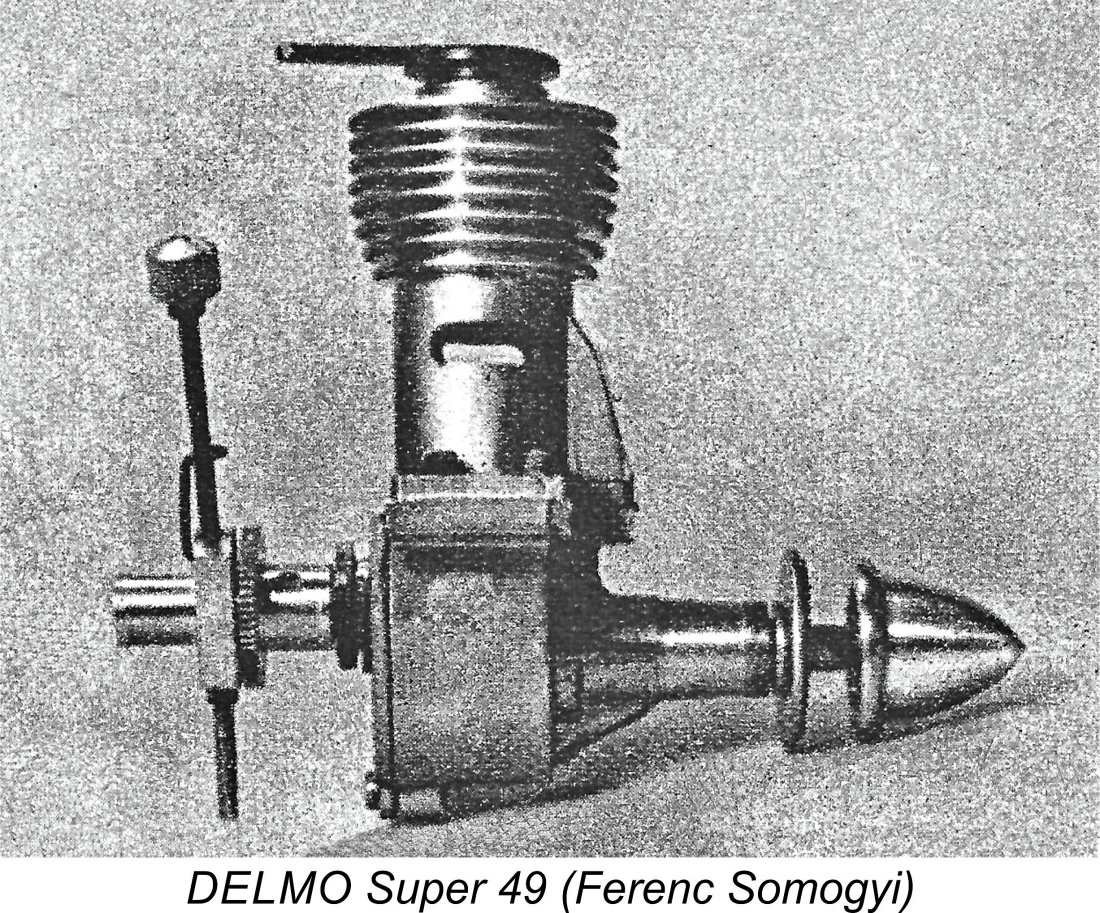

These rumors encouraged Maurice Delbrel to turn his attention back from the twins to a renewal of his efforts to identify further improvements to his 5 cc Super 5 model. In January 1949 the result of his efforts appeared in the form of perhaps his most original design, the DELMO Super 49.

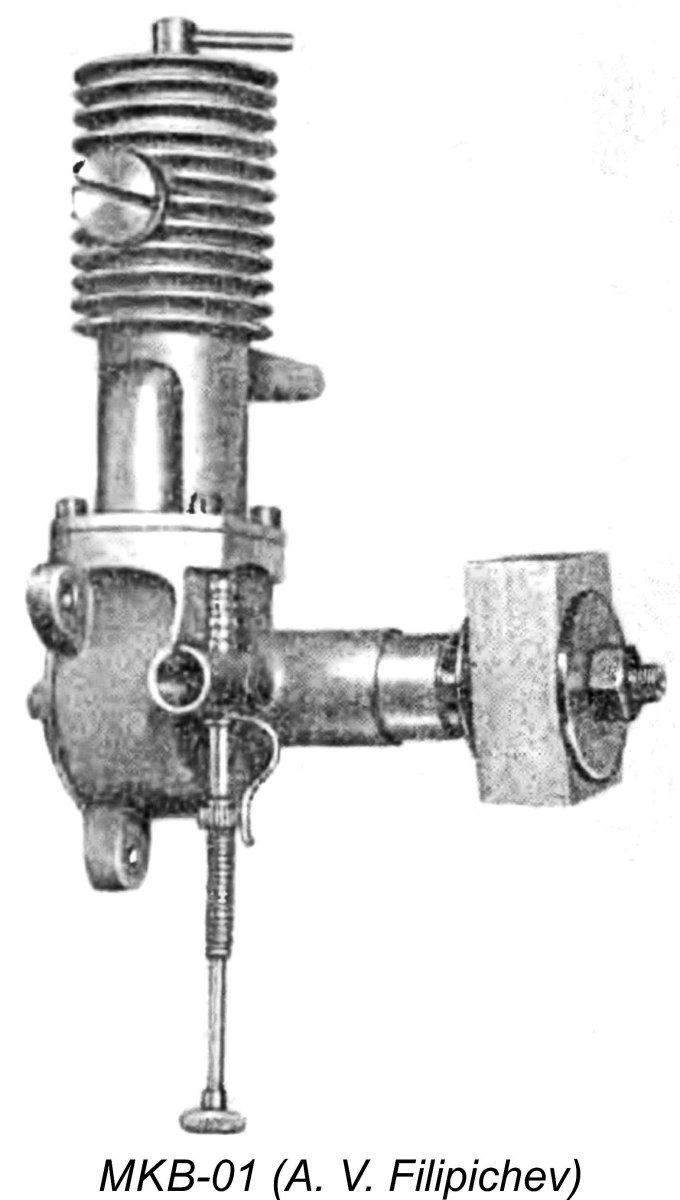

The only other remotely comparable multi-ignition unit of which I’m aware was V. I. Petukhov’s earlier MKB-01 diesel/spark ignition design from 1947 Russia. However, that design only ever appeared in prototype form and was never widely reported. Petukhov's 4.4 cc unit achieved its multi-ignition capability by very different means, using a plug inserted from the side of the cylinder independently from the contra-piston. It is shown in the attached image in diesel form without a timer and with the plug installation hole blanked off by an alloy machine screw. This very different arrangement implies that Delbrel's design for his Super 49 was indeed his own independent development - it's very doubtful that he ever so much as heard of Petukhov's earlier experiment. The Super 49 featured a centrally-located threaded hole in the middle of the upper plug which sealed the cylinder liner, into which the glow-plug was installed. Presumably the plug could be replaced by a machine screw if diesel-only operation was planned. The compression screw was now a large-diameter externally-threaded thin-walled steel cylinder which surrounded the plug and adjusted compression by moving the liner up or down as before. An extremely ingenious arrangement, it must be said! It appears that the concept of a multiple ignition "The heat generated by compression clearly influences the running of an engine equipped with a glow plug. A French manufacturer is currently studying the adaptation of his 5 cc compression ignition engine to glow plug operation, still with variable compression. The key to solving the problem may lie there.” This is presumably an early reference to M. Delbrel’s efforts coming well prior to the January 1949 market release of the Super 49. Seemingly the word had leaked out prematurely............ Interestingly enough, the claimed peak power output was little changed. However, that power was now released at a far lower speed, implying very much improved torque development and a consequent ability to swing a far larger prop. The claimed output of the Super 49 was 0.25 BHP @ 6,000 rpm as opposed to the claimed 0.27 BHP @ 9,000 rpm for the Super 5.

Also present on the market at the time was the Bonnier 5 cc model, which was very similar to the Micron 5 cc diesel but sold at only 2,600 francs. There were also very limited numbers of the Météore 5 cc racing model at 8,500 francs and the Allouchéry 5 cc model. The price for the latter model is unknown because it was never advertised, but it must lie around the prices of the competing Météore and Micron 29 units, since these three engines all featured the same configuration - glow-plug ignition, rear intake and crankshaft rotating on two ball bearings. Jules Maraget also offered his Météore 5 cc model in a Sport version (lapped ringless piston and a plain bearing). At 4,300 francs it was the cheapest French 5 cc glow-plug model. The situation as of the January 1949 market launch of Delbrel’s new Super 49 designs seemed promising enough. The Super 49 diesel replaced the Super 5 diesel while the multi-ignition version offered the inducement of its innovative specification. However, as the new decade of the 1950’s came around, things became complicated, especially for the 49 multi-ignition model, which was really just a variable compression glow-plug unit. In 1950 Micron introduced the Micron 28 glow-plug model (0.29 BHP @ 9,000 rpm and 170 gm), while 1951 saw the appearance of the R.E.A. 5 cc Compact glow-plug unit (0.35 BHP @ 10,600 rpm and 170 gm. These were two formidable competitors which sold at a lower price and which were easier to use and install because of their FRV induction. The 1953 catalog of "La Source des Inventions" listed the two aero versions of the Super 49 at the same price of 6,600 francs. At the same time, the Micron 28 and 5 cc diesel were priced respectively at 6,000 and 6,200 francs. The R.E.A. 5 cc model sold for 5,070 francs. For the “marine” versions, the situation was less unbalanced, but the demand was still weak. The DELMO Super 49 marine model at 7,200 francs lay between the R.E.A. 5 cc at 6,200 francs and the Micron 5 cc marine version at 8,500 francs. As matters unfolded, 1953 was to be the final year during which DELMO engines were marketed by the famous Parisian store which had been the main distributor of the brand from the beginning. Following the withdrawal of "La Source", the slow-selling twins were finally dropped from the range, but the Super 49 carried on for a while. End of the Line

The last engines were delivered in the spring of 1956, after which Maurice Delbrel decided to wind up his business. Fortunately for owners of DELMO engines, an annoucement appeared in the French modelling media in May 1956 to the effect that Micron dealers would continue to provide after-sales service. I have no idea how long this service continued to be provided. So ended a venture which had seen the development of a whole series of very well-made model engines bearing the unmistakably original design stamp of their talented creator, Maurice Delbrel. I hope that I've convinced a few of you that here is a fellow model engine enthusiast well worthy of our respectful remembrance! _______________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published November 2020

|

||

| |

This article adds another installment to my series of articles on this website about French model engines. Elsewhere I've covered the

This article adds another installment to my series of articles on this website about French model engines. Elsewhere I've covered the

Fortunately, an excellent reference source is readily available to anyone having an interest in this subject. This is the invaluable ”

Fortunately, an excellent reference source is readily available to anyone having an interest in this subject. This is the invaluable ”

The growing availability of proven spark ignition engines from America and the German Kratmo company in the mid to late 1930’s ignited Swiss interest in powered models. Perhaps some saw the potential of Thalheim’s unusual little engines, if their power-to-weight ratios could be improved.

The growing availability of proven spark ignition engines from America and the German Kratmo company in the mid to late 1930’s ignited Swiss interest in powered models. Perhaps some saw the potential of Thalheim’s unusual little engines, if their power-to-weight ratios could be improved.

Another point which merits our notice is the apparent emergence of a French “house style” of model diesel based on the use of fixed compression. There’s little or no doubt that the French designers were first in the field when it came to investigating this approach to the design and operation of model diesels. As noted previously, this may well have been a response to the perceived possibility that Ernst Thalheim might renew his patent regarding variable compression by vernier and contra-piston. Whatever the reason, Maeght tells us that of the seven marques listed above as having released diesels in 1943, no fewer than four featured fixed compression as a design standard, at least at this early stage.

Another point which merits our notice is the apparent emergence of a French “house style” of model diesel based on the use of fixed compression. There’s little or no doubt that the French designers were first in the field when it came to investigating this approach to the design and operation of model diesels. As noted previously, this may well have been a response to the perceived possibility that Ernst Thalheim might renew his patent regarding variable compression by vernier and contra-piston. Whatever the reason, Maeght tells us that of the seven marques listed above as having released diesels in 1943, no fewer than four featured fixed compression as a design standard, at least at this early stage. In terms of his aeromodelling activities, Maurice Delbrel's particular interest was in the design and operation of rotary-wing model aircraft. He was evidently a leading member of a like-minded group of French enthusiasts who began holding major competitions for rotary-wing model aircraft in 1947.

In terms of his aeromodelling activities, Maurice Delbrel's particular interest was in the design and operation of rotary-wing model aircraft. He was evidently a leading member of a like-minded group of French enthusiasts who began holding major competitions for rotary-wing model aircraft in 1947.

Delbrel established his workshop at 29 Rue Feray in Corbeil. This may well have also been his residence. He traded under the name DELMO, representing Delbrel Moteurs.

Delbrel established his workshop at 29 Rue Feray in Corbeil. This may well have also been his residence. He traded under the name DELMO, representing Delbrel Moteurs.

The compression control was also very unusual. The arm was a separate stamped steel component which was threaded onto the actual compression screw and was secured by a lock nut. The lever’s range of movement was limited to around 240 degrees by an integrally-machined protrusion at the front of the cylinder head. Because the required compression setting would undoubtedly vary considerably with different fuels, props and atmospheric conditions, the lock-nut could be released to allow the compression screw to be adjusted independently from the arm. A screwdriver slot was provided in the upper end of the comp screw for this purpose. Hopefully the attached image will make this arrangement clear.

The compression control was also very unusual. The arm was a separate stamped steel component which was threaded onto the actual compression screw and was secured by a lock nut. The lever’s range of movement was limited to around 240 degrees by an integrally-machined protrusion at the front of the cylinder head. Because the required compression setting would undoubtedly vary considerably with different fuels, props and atmospheric conditions, the lock-nut could be released to allow the compression screw to be adjusted independently from the arm. A screwdriver slot was provided in the upper end of the comp screw for this purpose. Hopefully the attached image will make this arrangement clear.  The downside of the moving liner arrangement for compression adjustment was the fact that changing the compression setting in this way also changed the cylinder port timing. Increasing the compression by moving the liner downwards reduced both the exhaust and transfer periods while also increasing the induction period. For a low-speed engine like the DELMO, this probably wasn’t that big a deal. We’ve seen this issue before in connection with the eccentric bearing system for compression adjustment as featured on the

The downside of the moving liner arrangement for compression adjustment was the fact that changing the compression setting in this way also changed the cylinder port timing. Increasing the compression by moving the liner downwards reduced both the exhaust and transfer periods while also increasing the induction period. For a low-speed engine like the DELMO, this probably wasn’t that big a deal. We’ve seen this issue before in connection with the eccentric bearing system for compression adjustment as featured on the  The final noteworthy feature was the type of cut-out employed. During the spark ignition era, engine runs had generally been limited by some form of timed ignition switch. With a diesel, this was not possible, leading to the use of some kind of fuel supply shut-off instead. The conventional approach was to simply stop the supply of fuel to the venturi throat. However, Delbrel had noticed that this general caused the engine to stop very abruptly. If it did this with the model in a full-power steeply-climbing attitude, the result would often be a stall.

The final noteworthy feature was the type of cut-out employed. During the spark ignition era, engine runs had generally been limited by some form of timed ignition switch. With a diesel, this was not possible, leading to the use of some kind of fuel supply shut-off instead. The conventional approach was to simply stop the supply of fuel to the venturi throat. However, Delbrel had noticed that this general caused the engine to stop very abruptly. If it did this with the model in a full-power steeply-climbing attitude, the result would often be a stall.

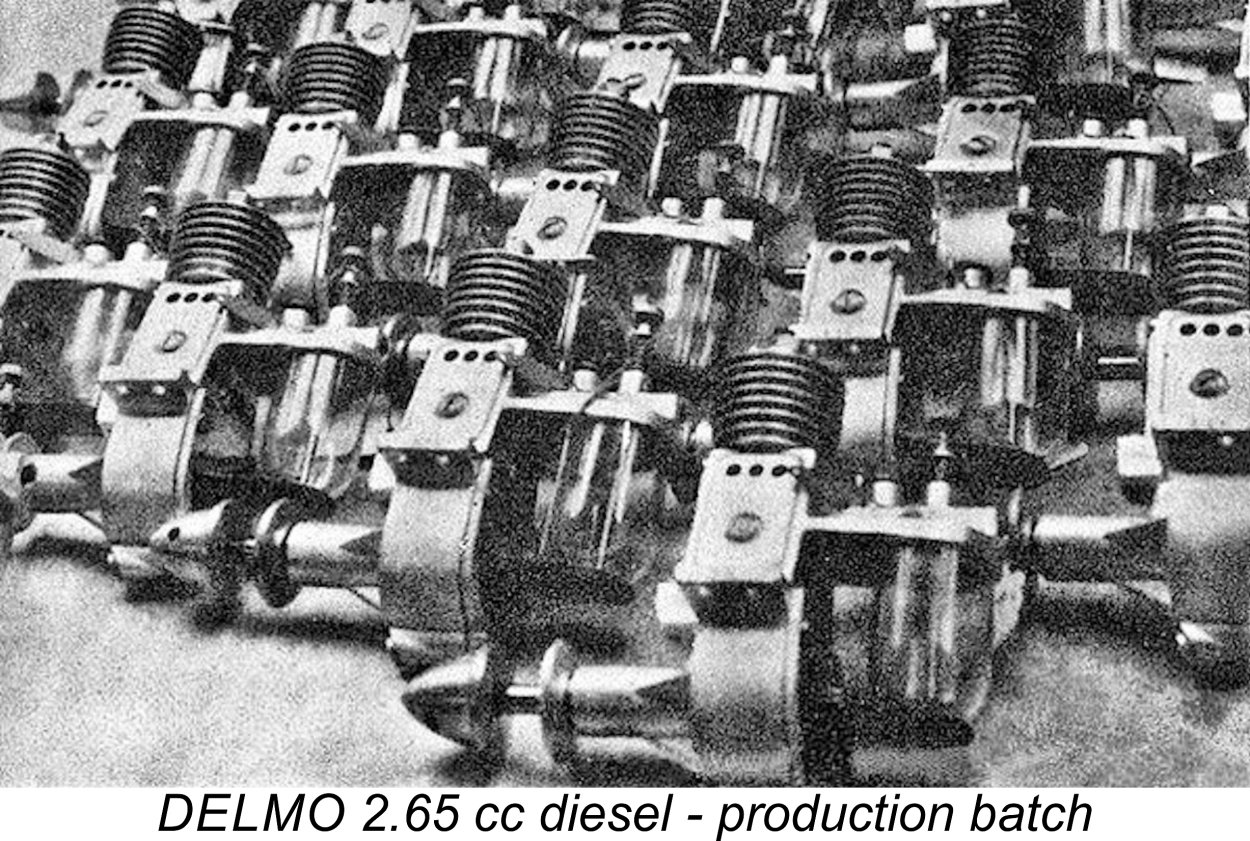

The economic situation had improved somewhat by the end of the summer of 1945, to the point that major Paris-based model sales outlets like CEKO and “La Source des Inventions” began to market the DELMO engines. By this time, Delbrel had made good progress towards matching his production figures to demand, as witness the attached image showing a batch of completed engines.

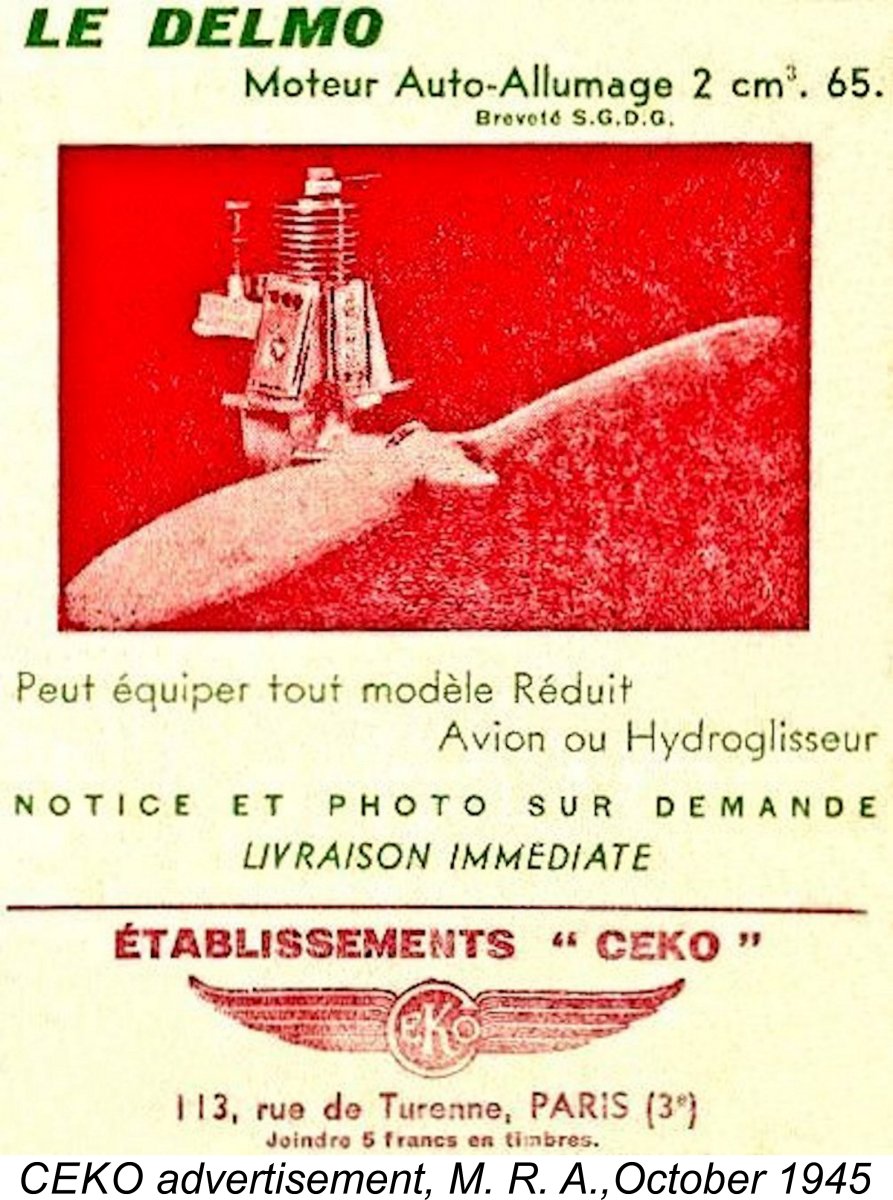

The economic situation had improved somewhat by the end of the summer of 1945, to the point that major Paris-based model sales outlets like CEKO and “La Source des Inventions” began to market the DELMO engines. By this time, Delbrel had made good progress towards matching his production figures to demand, as witness the attached image showing a batch of completed engines.  "La Source" was not the only French distributing house to pick up the DEMLO marque, at least initially. Another major outlet was "Établissements CEKO" of 113 Rue de Turenne, also in Paris. Somewhat strangely, CEKO did not advertise its selling price for the engine, instead stating that a description and photograph would be supplied upon request. They began with a very plain business-card style advertising placement in the September 1945 issue of "Le Modèle Réduit d'Avion" (M.R.A.) magazine, going on to place a relatively large colour advertisement in the October 1945 issue.

"La Source" was not the only French distributing house to pick up the DEMLO marque, at least initially. Another major outlet was "Établissements CEKO" of 113 Rue de Turenne, also in Paris. Somewhat strangely, CEKO did not advertise its selling price for the engine, instead stating that a description and photograph would be supplied upon request. They began with a very plain business-card style advertising placement in the September 1945 issue of "Le Modèle Réduit d'Avion" (M.R.A.) magazine, going on to place a relatively large colour advertisement in the October 1945 issue.

In June of 1946 Delbrel took his first step towards parity with his competitors by increasing the displacement of his 2.65 cc diesel to 3.5 cc. He accomplished this entirely through an increase in the bore from 13 mm to 15 mm, keeping the same 20 mm stroke. The revised figures yielded a calculated displacement of 3.53 cc (0.216 cuin.). My own illustrated example is one of these models.

In June of 1946 Delbrel took his first step towards parity with his competitors by increasing the displacement of his 2.65 cc diesel to 3.5 cc. He accomplished this entirely through an increase in the bore from 13 mm to 15 mm, keeping the same 20 mm stroke. The revised figures yielded a calculated displacement of 3.53 cc (0.216 cuin.). My own illustrated example is one of these models.  I had lost the compression setting as a result of having partially dismantled the engine to inspect it internally. This being the case, I set the compression by "feel" using the central compression screw with its slot head. Filling the tank, I set the needle at 2 turns open, primed the cylinder and got stuck in.

I had lost the compression setting as a result of having partially dismantled the engine to inspect it internally. This being the case, I set the compression by "feel" using the central compression screw with its slot head. Filling the tank, I set the needle at 2 turns open, primed the cylinder and got stuck in.

The DELMO 2.65 cc diesel and its 3.5 cc successor were very worthy efforts of which Maurice Delbrel could be justly proud. They certainly did great credit to his design and manufacturing capabilities. However, Delbrel was acutely aware that he couldn’t stop with the 3.5 cc model - a greater effort was needed if he was to compete with his rivals for sales and contest success.

The DELMO 2.65 cc diesel and its 3.5 cc successor were very worthy efforts of which Maurice Delbrel could be justly proud. They certainly did great credit to his design and manufacturing capabilities. However, Delbrel was acutely aware that he couldn’t stop with the 3.5 cc model - a greater effort was needed if he was to compete with his rivals for sales and contest success.  The system of compression adjustment using a blind-bored moveable liner was retained in the new model, although the former extrusion which had limited the range of movement of the compression control arm was eliminated from the cylinder head. The upper casting was substantially revised, with the two oil collection chambers being dispensed with along with the former rather massive integrally-cast induction tube, tank top and cut-out mounting boss. In addition, a greatly enlarged bypass bulge now appeared at the front of the upper casting.

The system of compression adjustment using a blind-bored moveable liner was retained in the new model, although the former extrusion which had limited the range of movement of the compression control arm was eliminated from the cylinder head. The upper casting was substantially revised, with the two oil collection chambers being dispensed with along with the former rather massive integrally-cast induction tube, tank top and cut-out mounting boss. In addition, a greatly enlarged bypass bulge now appeared at the front of the upper casting.  Delbrel was clearly single-minded in his approach to the quest for lower weight. The crankshaft was hollow, with the crankweb being machined away to the extent possible, creating what would appear to be a seriously unbalanced configuration. A similar design was employed in the British

Delbrel was clearly single-minded in his approach to the quest for lower weight. The crankshaft was hollow, with the crankweb being machined away to the extent possible, creating what would appear to be a seriously unbalanced configuration. A similar design was employed in the British

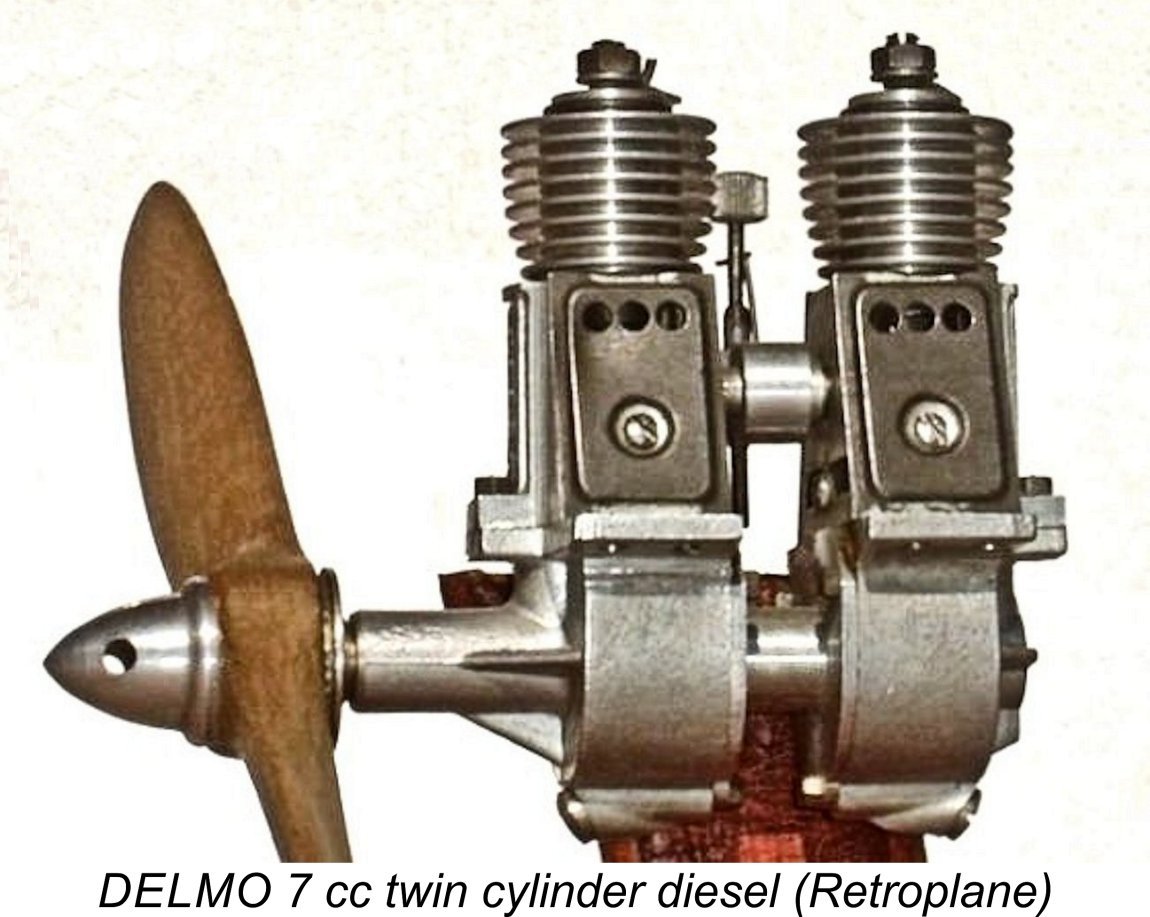

The old 3.5 cc aero model did have a brief stay of execution by being redeveloped into one of Delbrel’s rarest but most famous creations - his 7 cc in-line twin cylinder diesel of the latter part of 1947. The original prototype was created by assembling two 3.5 cc cylinder/crankcase assemblies back to back using a newly-created centre section. This allowed the prototype to be created using a maximum of pre-existing components.

The old 3.5 cc aero model did have a brief stay of execution by being redeveloped into one of Delbrel’s rarest but most famous creations - his 7 cc in-line twin cylinder diesel of the latter part of 1947. The original prototype was created by assembling two 3.5 cc cylinder/crankcase assemblies back to back using a newly-created centre section. This allowed the prototype to be created using a maximum of pre-existing components.

The strong competition between modellers in that category naturally stimulated a similar competition among engine manufacturers. Essentially, it became a race for power. André Gladieux, who had just introduced his 10 cc Micron 60, now announced that he was working on a similar design of 5 cc displacement. For his part, Météore designer Jules Maraget announced in advertisements featured in M.R.A. magazine that he too was developing a 5 cc ball-race model. Finally, it was learned that both JIDE designer Jacques Durand and

The strong competition between modellers in that category naturally stimulated a similar competition among engine manufacturers. Essentially, it became a race for power. André Gladieux, who had just introduced his 10 cc Micron 60, now announced that he was working on a similar design of 5 cc displacement. For his part, Météore designer Jules Maraget announced in advertisements featured in M.R.A. magazine that he too was developing a 5 cc ball-race model. Finally, it was learned that both JIDE designer Jacques Durand and  Although the bore and stroke of 17 mm and 22 mm respectively were carried over from the Super 5, the new model bristled with design innovations. Induction was now by a rotary disc valve - another innovation as far as Maurice Delbrel was concerned. This change was motivated in part because this form of induction was far better suited to high-speed operation, but also because it allowed the use of a smaller-diameter crankshaft than would be possible if FRV induction was adopted, thus saving weight. The crankshaft was now supported by a ball bearing at the rear. It also featured a counterbalanced crankweb.

Although the bore and stroke of 17 mm and 22 mm respectively were carried over from the Super 5, the new model bristled with design innovations. Induction was now by a rotary disc valve - another innovation as far as Maurice Delbrel was concerned. This change was motivated in part because this form of induction was far better suited to high-speed operation, but also because it allowed the use of a smaller-diameter crankshaft than would be possible if FRV induction was adopted, thus saving weight. The crankshaft was now supported by a ball bearing at the rear. It also featured a counterbalanced crankweb.

Although highly original, the multi-ignition model was inherently more complex to construct, with a consequently higher selling price. This led to the Super 49 being offered in both multi-ignition and diesel-only variants. In addition, watercooled marine versions of both types were offered from the outset. The aero models were sold at 4,950 francs for the multi-ignition version and 4,600 francs for the diesel. These prices lay between those of the ultra-powerful Micron 29 (0.50 BHP at 14,000 rpm and 8,700 francs) and the Micron 5 cc diesel (0.22 BHP at 5,500 rpm and 4,150 francs). Although the power of the latter seemed close, the Super 49 had the advantage of being lighter at 200 gm against 285 gm. At the time of making a choice, this could weigh in the balance for certain model makers.

Although highly original, the multi-ignition model was inherently more complex to construct, with a consequently higher selling price. This led to the Super 49 being offered in both multi-ignition and diesel-only variants. In addition, watercooled marine versions of both types were offered from the outset. The aero models were sold at 4,950 francs for the multi-ignition version and 4,600 francs for the diesel. These prices lay between those of the ultra-powerful Micron 29 (0.50 BHP at 14,000 rpm and 8,700 francs) and the Micron 5 cc diesel (0.22 BHP at 5,500 rpm and 4,150 francs). Although the power of the latter seemed close, the Super 49 had the advantage of being lighter at 200 gm against 285 gm. At the time of making a choice, this could weigh in the balance for certain model makers. The loss of his main distributor left Delbrel in a very shaky situation from a business standpoint. Without advertising in the modelling media, with a glow-plug version attracting minimal demand and with a growing disaffection among model makers towards large diesels, the following few years saw the production of Delbrel's one remaining offering, the DELMO Super 49, steadily decrease.

The loss of his main distributor left Delbrel in a very shaky situation from a business standpoint. Without advertising in the modelling media, with a glow-plug version attracting minimal demand and with a growing disaffection among model makers towards large diesels, the following few years saw the production of Delbrel's one remaining offering, the DELMO Super 49, steadily decrease.