|

|

Montreal Masterpieces - the Strato Engines

Canada is definitely not the first country that comes to mind when the subject of commercial model engine manufacturing comes up. In large part this is doubtless due to the combination of two factors – one, Canada's huge geographic area which created a very wide spread among a relatively small population and hence a highly fragmented domestic marketplace; and two, the presence of a ready source of competitively-priced engines which were mass-produced to a high standard immediately south of the border in the USA. The first of these two factors tended to restrict model engine manufacturing in Canada to small-scale ventures located in major population centres which produced limited numbers of engines primarily intended for the local Canadian market in the immediate area of production. The competition from the USA made it very difficult for Canadian manufacturers to compete price-wise in the broader marketplace. Those few who tried certainly deserve our respect! Let’s briefly survey the Canadian model engine manufacturing scene up to the point at which the Strato engines made their appearance. Early Canadian Model Engine Manufacturing Initiatives

The Ajax engines were predominantly marketed through the St. John Model Shop on Portage Avenue in Winnipeg, although a couple were sold in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan and a small number in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The associated brochures specifically cited this engine as “the first motor to be manufactured in Canada”, seemingly confirming its priority.

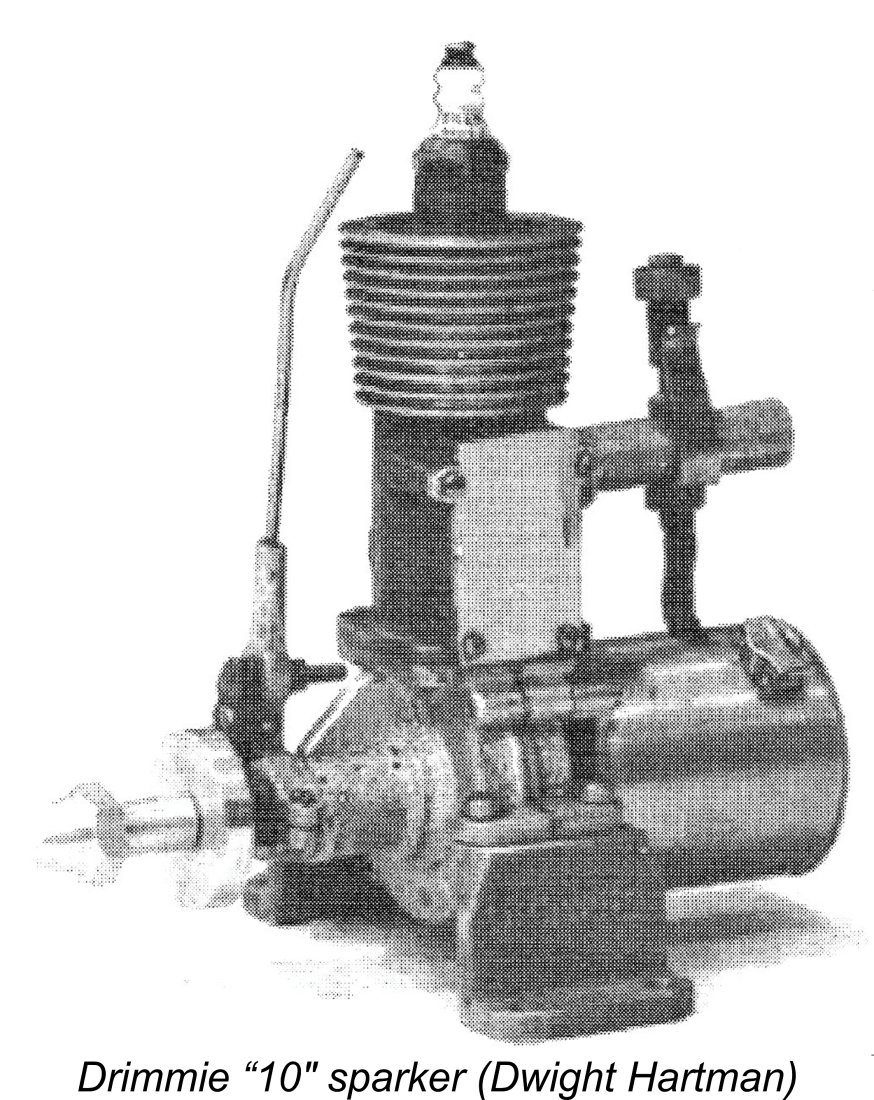

Despite this latter development, an enthusiast named Paul Drimmie of Toronto, Ontario somehow managed to produce a very small number of examples of a 0.607 cuin. (9.95 cc) side-port spark ignition engine called the Drimmie ”10” in 1940. However, this effort ended almost as soon as it had begun, doubtless due to the intrusion of other more pressing national concerns. It seems that Drimmie never resumed model engine manufacture after the war. Despite the impact of the onset of WW2 on Canadian priorities, another Canadian who somehow managed to enter the model engine field at this time was a Montreal resident named Randall Bainbridge. He marketed his products under the Strato Model Engines label. The engines which he produced constitute the central subject of this article. The Strato Range - a Summary Until relatively recently I had no information whatsoever on Randall Bainbridge beyond his name. However, this changed when Tim Dannels’ genealogically-savvy son-in-law Sheldon Jones very kindly agreed to help. Sheldon was able to track down some very useful information on Bainbridge which does much to bring him into focus as an individual as opposed to a mere name associated with an engine. My very sincere thanks to Sheldon!

It’s a great pity that no-one seems to have taken full advantage of the opportunity that clearly existed to tap into his personal memories while they were still there to be shared. I'm very grateful to Randall Bainbridge's nephew Robert Lejeune for providing a few additional details about Bainbridge's life which were not otherwise available. As of 2024, Robert still had a Strato Super 60 which was given to him years ago by his uncle. He recalled that when his uncle stated that he had made that engine, young Robert was initially skeptical! Although a bricklayer by trade, it's clear that Randall Bainbridge was also an enthusiastic and talented model engineer. The Strato engines produced by Bainbridge consisted of a series of 0.604 cuin. (9.90 cc) models, all of which were constructed between 1940 and 1947 with a break during the midde years of WW2. The majority of these were side-port spark ignition units, although a single prototype diesel appeared near the end of Bainbridge’s involvement with the Strato marque, along with a couple of experimental crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) spark ignition designs. In general, the Strato engines followed the standard design format for general-purpose engines which had evolved in North America during the nineteen-thirties. When considering the Strato venture, it must be remembered that unlike the neighbouring USA, Canada was heavily embroiled in WW2 at the time in question, with a consequent re-focusing of national attention away from hobbies such as aeromodelling as well as a diversion of both materials and precision engineering capacity into war production. The attached poster donated to the Canadian war effort by the Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Company (est. 1928) conveys a sense of the urgency felt at the time. Given this situation, it’s a bit of a matter for wonder that Bainbridge managed to produce any model engines at all under the circumstances! Since he was 27 years old when he produced his first engine in 1940, Bainbridge was definitely of military age. However, he does not seem to have been called up at any time. He may have suffered from some kind of perceived physical disability which rendered him unfit for military service. There is evidence that this was the case, since according to Robert Lejeune he contracted tuberculosis in 1942, spending a year in the Montreal T.B. sanitorium and eventually having a lung removed. Following his recovery and release, he returned to his bricklaying occupation.

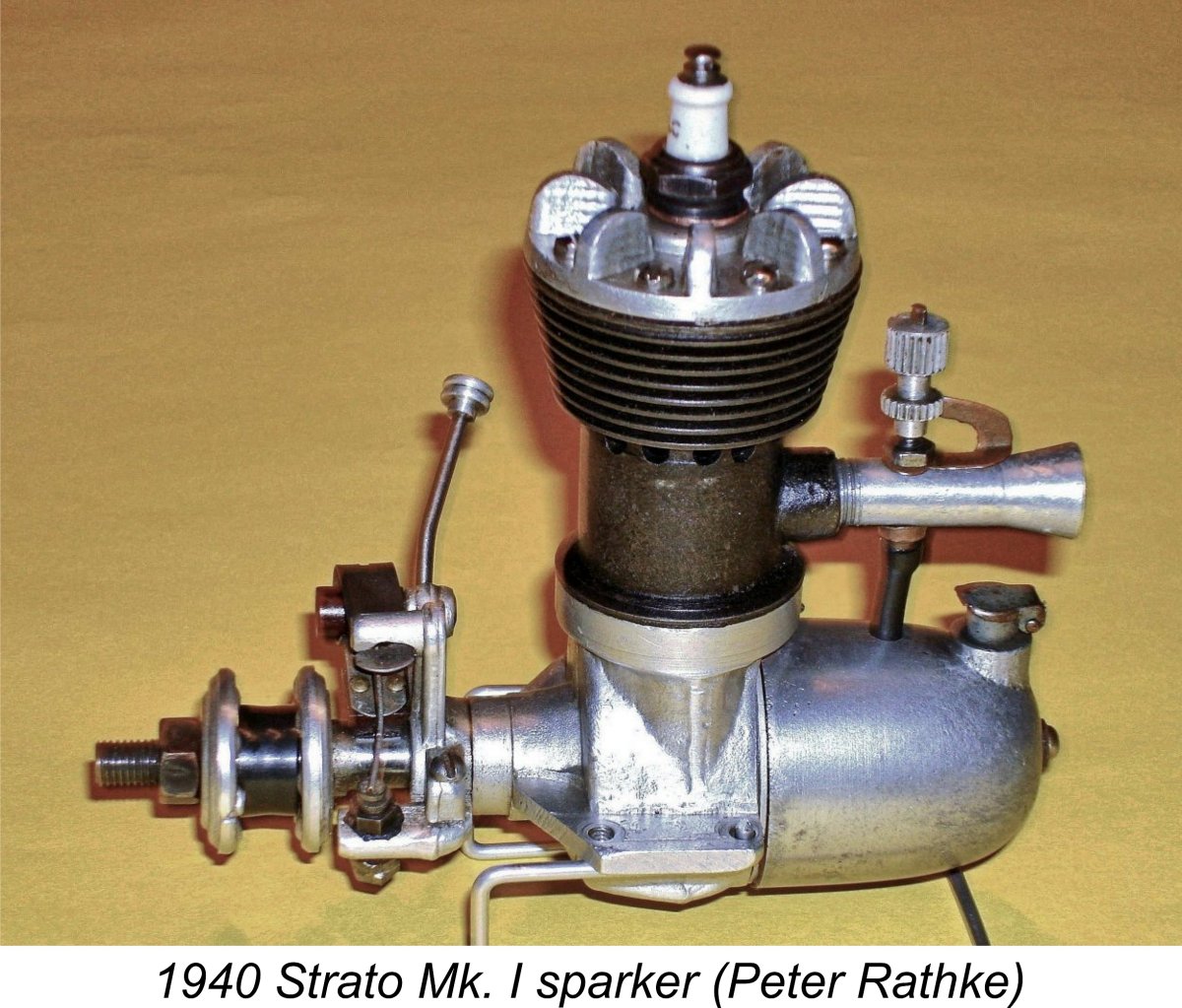

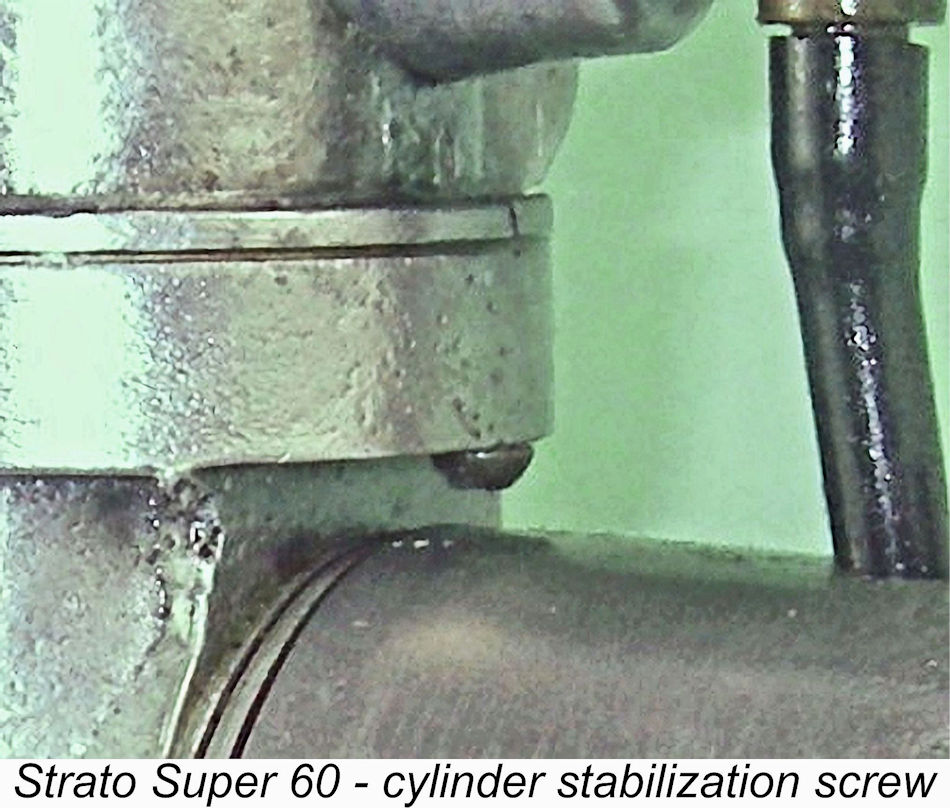

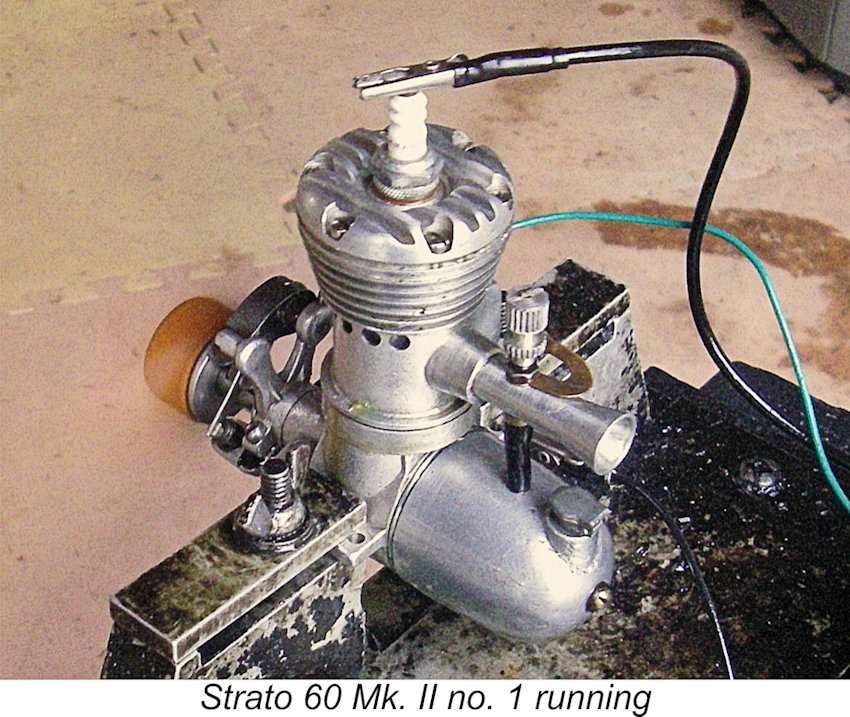

The first Bainbridge design to appear was the Strato Mk. I sparker of 1940. It was a .604 cuin. (9.90 cc) side-port unit having a very heavy screw-in cast iron cylinder with integral fins along with a sand-cast crankcase. A noteworthy feature was its radially-finned cast alloy cylinder head, reminiscent of that seen on the infamous G.H.Q. unit from 1930’s America (as was the cast iron cylinder). Somewhat unusually for its date of manufacture, it was a short-stroke design, having bore and stroke dimensions of 0.9375 in. (23.81 mm) and 0.875 in. (22.22 mm) respectively. My thanks to my good friend and colleague Peter Rathke for providing the attached image. The design was such that the screw-in cylinder had to be correctly aligned with the intake at the rear and the exhaust ports at the left side. This alignment had to be maintained at all times following assembly. A typical indication of the level of care and attention to detail which Bainbridge applied to his engines was the way in which he approached the very common problem of a screw-in cylinder The screw-in cylinder was correctly aligned when fully tightened through the trial-and-error use of brass shims of varying thicknesses between the cylinder location flange and the upper crankcase deck. A hole was formed in this shim. Matters were arranged so that the two holes in the engine and the hole in the shim were in perfect alignment when the cylinder was fully tightened. A small bullnose machine screw was inserted from below into the tapped hole in the upper crankcase and screwed home. The unthreaded bullnose protruded through the shim into the hole in the cylinder flange. It should be obvious that this prevented any radial movement of the cylinder in its installation thread. A very effective solution! The main drawback of the Strato Mk. I was its weight – all of 15 ounces (425 gm) exclusive of the ignition support components. That’s a lot for a simple plain bearing side-port unit of this displacement! After only some 10 examples had been built and presumably sold, a somewhat lighter Mk. II model was The cylinder head now sported linear fore-and-aft fins in place of the former radial arrangement. There were also performance-related changes to the engine’s porting dimensions and timing. The various changes reduced the engine's weight to a somewhat more rational checked figure of 10.8 ounces (306 gm) complete with timer, plug and tank. About 8 examples of this second variant were manufactured before production seemingly ground to a temporary halt, likely due to the ongoing exigencies of wartime. It would appear that Bainbridge found himself short of either the free time or the materials (perhaps both) to permit him to continue. In any event, one is forced to wonder who Bainbridge's customers would have been at the time in question when other priorities predominated. Thanks to the kindness of its former owner Peter Rathke, I was privileged to become the owner of engine number 1 of this very rare variant. Although this example appears to have been unused since its long-ago factory test run, it felt quite free when turned over, albeit with outstanding compression. This being the case, I saw no harm in setting it up in the test stand to give it a chance to do what it was designed to do.

The Strato 60 proved to be an extremely easy engine to start. I found that finger choking alone was a bit uncertain when the engine was cold - a small prime was helpful. Once that was given, starting took only one or two flicks if the needle was anywhere near right. In deference to its near-new condition, I kept the engine rich with slightly retarded ignition timing. In this condition, running was very smooth indeed - I was quite impressed! A very brief leaned-out spot check following a couple of runs showed a speed of 5,400 rpm on the 14x4 test prop. Not very fast, but a lot of air was being shifted! The engine would doubtless do a little better than this if fully run in and set more precisely.

This model was basically similar to the Mk. II but featured further modifications to the porting arrangements to improve performance. Evidence of such changes is to be seen in the larger exhaust apertures featured on the Mk. III variant. This was also the first rendition of the engine to feature the classy little brass "STRATO SUPER 60" plate attached to the bypass. Some 20 examples were reportedly manufactured in 1944/45, presumably all finding buyers. The illustrated example is no. 8 of this series. The various changes increased the engine's weight very slightly to 11.0 ounces (312 gm).

Like its Mk. II predecessor, the Strato "Super" 60 Mk. III proved to be an instant starter and a very smooth runner. The 14x4 Top Flite wood prop which I used once more seemed to suit it very well - I saw 5,600 rpm during a cautious and very brief spot-check and am certain that the engine would beat this if properly run in and more carefully adjusted. Although the previously-mentioned stiffness was clearly holding the engine back, I got the impression that it would develop into a user-friendly powerplant having a more than adequate performance by the standards of its day. Moreover, it seems sturdy enough to outlast a succession of owners. Overall, I was quite impressed! A significant assembly challenge inherent in the designs of all three Strato models produced up to this point was their previously-mentioned use of screw-in cylinder assemblies. The layout was such that the cylinder had to end up in a specific orientation when tightened, with the intake pointing to the rear and the exhaust ports on the left. Inspection of a number of examples confirms that this was achieved through the selective use of shims to secure the correct orientation.

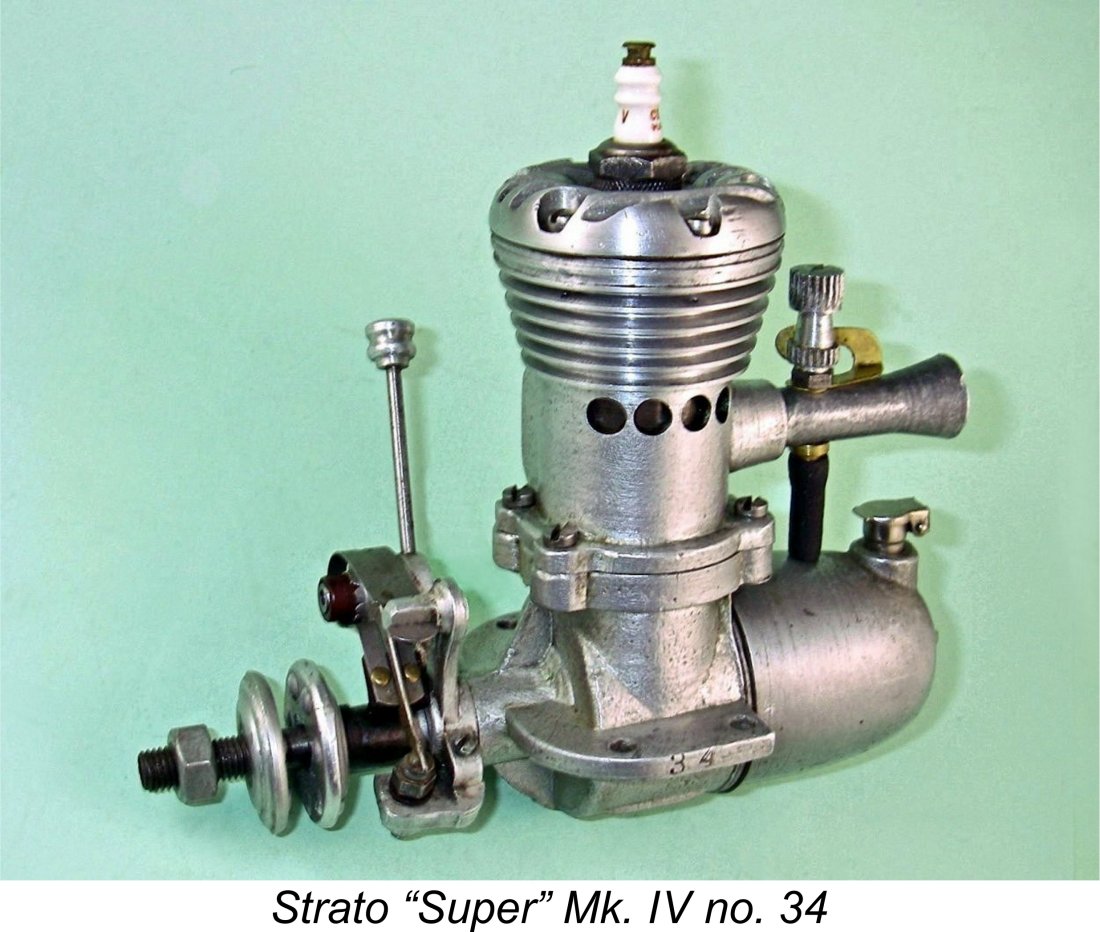

The final Strato design to make a commercial appearance was seemingly designed specifically to address this assembly issue. It took the form of the Strato “Super” 60 Mk. IV which made its debut in 1946. This was yet another .604 cuin. spark ignition side-port unit which featured a completely revised set of castings and a different method of assembly using bolts instead of screw-in components. End of assembly problem! Most of these engines such as illustrated engine no. 34 featured metal tanks, but a few later examples sported plastic items. The various changes reduced weight very slightly to 10.7 ounces (303 gm).

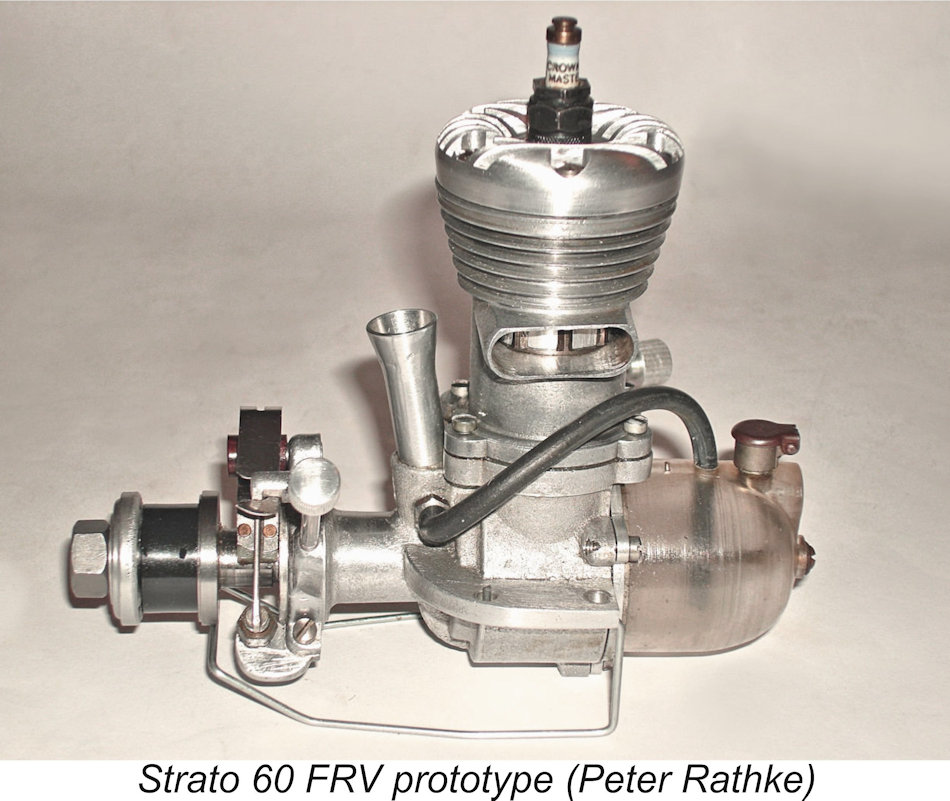

Bainbridge evidently enjoyed tinkering with different design concepts. Towards the end of his involvement with model engine manufacture, he produced at least two crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) spark ignition units and a single fixed compression side-port 0.604 cuin. The FRV design was presumably envisioned as the Strato Super 60 Mk. V, but it appears never to have actually reached the marketplace. Remarkably enough, two examples of this unit have survived down through the years. The example owned by my friend and colleague Peter Rathke is shown at the right. Apart from the use of FRV induction, another innovation featured in this engine is a twin-ringed light alloy piston running in a cylinder having bridged ports. There are two transfer apertures and four exhaust openings. Equally remarkably, the sole example of the Strato diesel that was ever produced also still survives in perfect condition, once again in the possession of Peter Rathke. In essence, it's a fixed compression diesel version of the Strato Super 60 Mk. IV with the timer omitted.

Another interesting feature not found in other Strato models was the addition of a drain valve at the bottom of the crankcase. This was undoubtedly aimed at facilitating the clearing of a flooded engine, since this could not be accomplished in the more conventional way by reducing compression and running off the excess. My thanks again to Peter Rathke for providing the attached image. Sadly but perhaps inevitably, Bainbridge found that with his very limited production capacity based upon individual construction to very high toolroom standards he could not compete either in price or performance terms with mass-produced American-built .60 cuin. alternatives such as the Ohlsson & Rice, Atwood, Herkimer (OK) and Super Cyclone units which became increasingly available in Canada following WW2. After some 40 examples of the Mk. IV sparker had been manufactured (I own engine no. 37), Bainbridge finally abandoned the model engine field in early 1947. His subsequent activities are completely undocumented. It seems clear that Bainbridge's model engine production had never at any time been on a scale which would have supported him financially. He must surely have had other full-time employment all along, approaching the manufacture of model engines on a part-time basis as a labour of love. Unfortunately, I have been unable to track down any information regarding his parallel activities. Bainbridge’s Canadian Successors

At the conclusion of WW2, Bainbridge’s lead was quickly followed by others. Among the first into the fray was Sammy Crystal of Toronto, who introduced the Merlin Super “B” 0.232 cuin. (3.80 cc) sparker in 1945 under the auspices of his Merlin Miniatures company. This well-made and lightweight engine appeared in three successive variants between 1945 and 1947. It was manufactured in considerable numbers, latterly being produced in whole or in part in New York City. Production of the Merlin "Super B" seems to have ended in late 1947 or early 1948, presumably as a result of the arrival of the commercial miniature glow-plug in late 1947. There's no evidence that a glow-plug version of the engine was ever developed.

The final commercial offering from the Salonen brothers was a glow-plug version of the Queen Bee 29 which appeared in early 1948 shortly after Ray Arden’s late 1947 introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug. It seems to have remained in limited production until early 1950, when all manufacture ceased.

Perhaps the best-known and longest-lasting name in Canadian model engine manufacturing history is the Hurricane series which was manufactured between 1944 and 1950 in Toronto, Ontario, initially by Murray “Ray” Hunter’s Production & Tool Company located on Adelaide Street East in Toronto, but later by Ray Hunter himself. The company’s original design, the late 1944 Hurricane, was a 0.244 cuin. (4.0 cc) FRV spark ignition model which was almost identical to the 1942 Dreadnaught .24 from Oakland, California with a few very minor detail alterations. Apparently this model was originally to be called the “Whirlwind”, but this choice of name was amended to “Hurricane” just as production was getting underway. A few boxes were actually produced bearing the “Whirlwind” name.

This was simply a straightforward glow-plug conversion of the final Super Hurricane sparker. It was basically the same engine with the timer omitted and a metal tank replacing the former plastic item. It was a very serviceable powerplant which performed well by the standards of its day. However, it did not sell in sufficient numbers to ensure the survival of the Hurricane marque – production seems to have ended at some point in 1950.

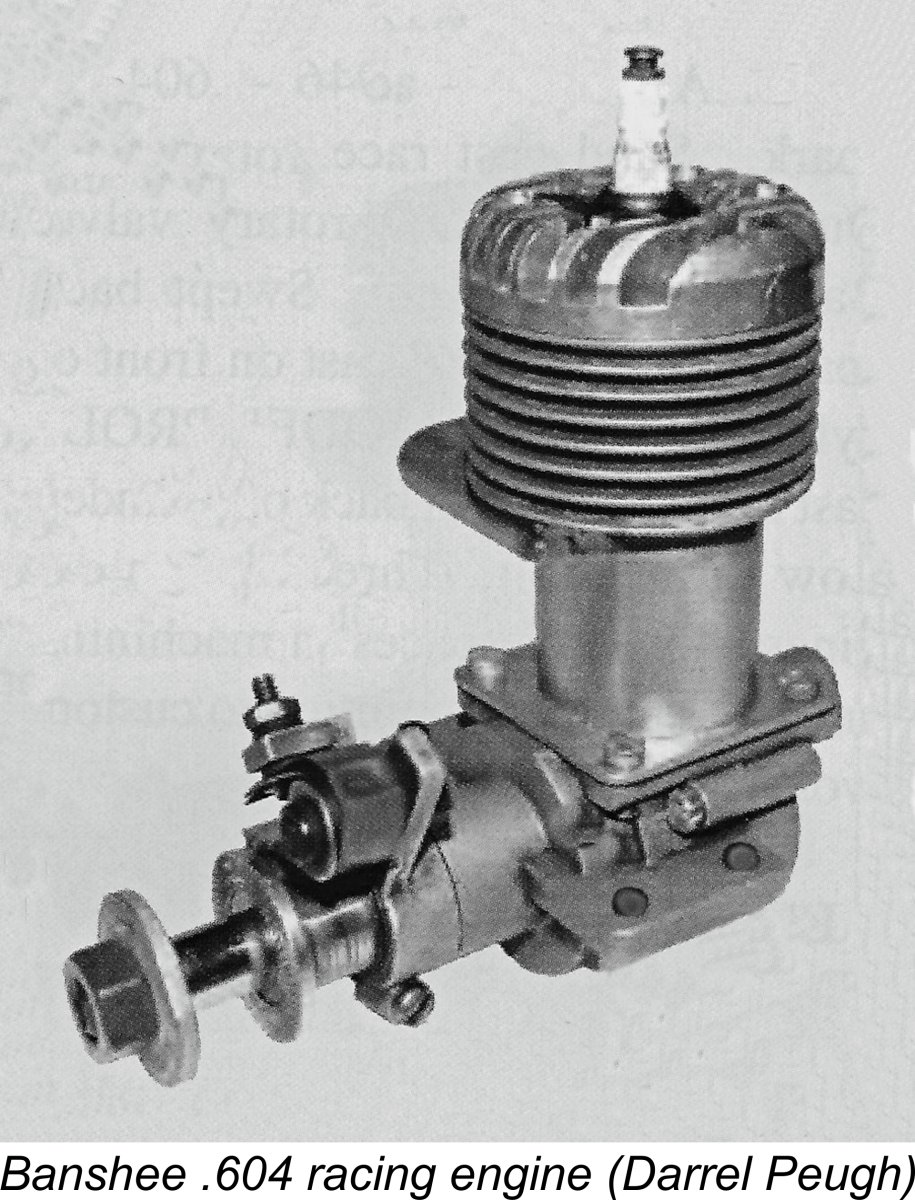

For a North American racing engine, the Banshee was unusual in featuring only a single ball race at the rear of the crankshaft. The rest of the shaft was carried in a bronze bushing. Although the absence of a front ball race may seem a little odd in a racing engine context, there was actually sound reasoning behind it. Check out my companion article on the Mamiya range from Japan for a full discussion of this issue. The Banshee has one other claim upon our interest - it was the subject of a limited "collector's re-issue" by its original manufacturer in 1987, over 40 years after its original release! Both surviving original parts and some re-manufactured components were used in the creation of this reproduction. Examples are extremely rare today.

There were a few very small-scale Canadian productions which scarcely seem to qualify for inclusion in a listing of commercial products. A very few examples each of several different CANUCK models were produced in the late 1940's by Lionel Gay and Keith Wooley using the facilities of the AVRO full-scale aircraft plant at Malton, Ontario, where they both worked. Both .049 and .35 cuin. models were made, albeit in far less than commercial numbers - perhaps 12 examples of the .049 and a couple of .35's. Much later, there were also a few high quality team race diesels made by Brian Fairley in a variety of styles. Some of these even bore a maple leaf emblem. But those are later stories, to be told elsewhere by others ……………… Conclusion I’d like to finish up by returning the attention of my readers to the Strato range which effectively got the ball rolling in Canada back in the pioneering era. Examples of this range are in very short supply today - after all, Randall Bainbridge only appears to have produced a total of some 80 engines during the six years or so during which he was active in the model engine field. That said, if you ever get a chance to experience one of these fine products, I strongly recommend that you take advantage of the opportunity! Anyone who appreciates fine model engineering is bound to be impressed! ___________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published May 2023 |

| |

Here I’ll focus on another of the fine model engine ranges which appeared in my adopted country of Canada during the pioneering and classic eras. I already dealt with the

Here I’ll focus on another of the fine model engine ranges which appeared in my adopted country of Canada during the pioneering and classic eras. I already dealt with the  Although a few individual model engines were undoubtedly made in Canada by talented hobby machinists during the pre-WW2 period leading up to September 1939, there seems to be only one record of any commercial-scale series production being undertaken in Canada during those years. This relates to the Ajax .359 cuin. (5.88 cc) spark ignition model which was manufactured in Winnipeg, Manitoba in 1938 and 1939 by one Arthur Jaques following some successful prototype testing in 1937. No prizes for guessing the origin of the Ajax name ………… Apologies for the poor quality of the attached image extracted from a surviving brochure, but it's the only one that exists!

Although a few individual model engines were undoubtedly made in Canada by talented hobby machinists during the pre-WW2 period leading up to September 1939, there seems to be only one record of any commercial-scale series production being undertaken in Canada during those years. This relates to the Ajax .359 cuin. (5.88 cc) spark ignition model which was manufactured in Winnipeg, Manitoba in 1938 and 1939 by one Arthur Jaques following some successful prototype testing in 1937. No prizes for guessing the origin of the Ajax name ………… Apologies for the poor quality of the attached image extracted from a surviving brochure, but it's the only one that exists! According to research carried out by Paul Knapp with the late Arthur Polson and published by Tim Dannels in

According to research carried out by Paul Knapp with the late Arthur Polson and published by Tim Dannels in

developed having revised crankcase and cylinder castings produced in light alloy from permanent molds with thin cylinder liners.

developed having revised crankcase and cylinder castings produced in light alloy from permanent molds with thin cylinder liners.  The instruction leaflet confined itelf to a statement that the Strato 60 delivered 7,000 - 8,000 rpm on 14 - 15 in. dia. props of unspecified pitch. I had a Top Flite 14x4 wood prop which I thought should suit the engine well. Set up in the stand with that prop fitted, the Strato Super 60 Mk. II looked and felt great! A timer function check showed that the timer was working perfectly. Setting it in an appropriate starting position, I hooked up the

The instruction leaflet confined itelf to a statement that the Strato 60 delivered 7,000 - 8,000 rpm on 14 - 15 in. dia. props of unspecified pitch. I had a Top Flite 14x4 wood prop which I thought should suit the engine well. Set up in the stand with that prop fitted, the Strato Super 60 Mk. II looked and felt great! A timer function check showed that the timer was working perfectly. Setting it in an appropriate starting position, I hooked up the  As the eventual outcome of the war became increasingly clear, limited model engine production resumed in the USA in August 1944 when the US War Production Board decided to release sufficient material and manufacturing capacity for non-military purposes to allow this to happen. Randall Bainbridge took advantage of the concurrent relaxation of wartime restrictions in Canada to resume small-scale model engine production at this time with the Strato “Super” 60 Mk. III.

As the eventual outcome of the war became increasingly clear, limited model engine production resumed in the USA in August 1944 when the US War Production Board decided to release sufficient material and manufacturing capacity for non-military purposes to allow this to happen. Randall Bainbridge took advantage of the concurrent relaxation of wartime restrictions in Canada to resume small-scale model engine production at this time with the Strato “Super” 60 Mk. III.  Thanks once again to the kindness of Peter Rathke, I was able to acquire this particular example as well. Just for fun, I set it up in the test stand to give it a few runs. It was clearly unrun apart from its factory test, hence feeling quite stiff when turned over and clearly being in need of a considerable amount of running-in time. Since I wasn't planning to fly the engine, I had no intention of running it in - I merely wanted to experience its handling and running qualities at first hand. Accordingly, I planned to keep the ignition timing a little retarded, along with a somewhat rich needle.

Thanks once again to the kindness of Peter Rathke, I was able to acquire this particular example as well. Just for fun, I set it up in the test stand to give it a few runs. It was clearly unrun apart from its factory test, hence feeling quite stiff when turned over and clearly being in need of a considerable amount of running-in time. Since I wasn't planning to fly the engine, I had no intention of running it in - I merely wanted to experience its handling and running qualities at first hand. Accordingly, I planned to keep the ignition timing a little retarded, along with a somewhat rich needle.

Having run its two predecessors with no difficulty, I felt quite comfortable in giving one of my Strato Super 60 Mk. IV units a run or two. Engine number 18 appeared to be reasonably well freed up, although it remained unmounted. I decided to give that example a chance to display its handling and running qualities. So into the test stand it went, fitted with the same 14x4 Top Flite wood airscrew that its companions had turned so effectively. It turned out to be just as user-friendly as its predecessors, starting very easily and running smoothly. On a brief spot check, it turned the 14x4 prop at 5,700 rpm - the fastest yet. Mind you, the three test engines were very close to one another - the very small differences may be incidental. Moreover, none of the three was operating at its best given the fact that they all required a fairly extended break-in period which I saw no point in giving them.

Having run its two predecessors with no difficulty, I felt quite comfortable in giving one of my Strato Super 60 Mk. IV units a run or two. Engine number 18 appeared to be reasonably well freed up, although it remained unmounted. I decided to give that example a chance to display its handling and running qualities. So into the test stand it went, fitted with the same 14x4 Top Flite wood airscrew that its companions had turned so effectively. It turned out to be just as user-friendly as its predecessors, starting very easily and running smoothly. On a brief spot check, it turned the 14x4 prop at 5,700 rpm - the fastest yet. Mind you, the three test engines were very close to one another - the very small differences may be incidental. Moreover, none of the three was operating at its best given the fact that they all required a fairly extended break-in period which I saw no point in giving them.  diesel as experiments, although these never saw series production at any level.

diesel as experiments, although these never saw series production at any level.

Out on Canada’s West Coast, the

Out on Canada’s West Coast, the

Two further minor variants of the Hurricane 24 followed in 1945, along with a very few examples of a short-lived .198 cuin. spark ignition design which followed a generally similar design layout. In January 1946 the first of three successive “Super Hurricane 24” variants appeared with their “trademark” streamlined cooling fin profile. These Super Hurricane .24 cuin. spark ignition models remained in production into 1948, hence being manufactured in substantial numbers. However, their run came to an end in early 1948 with the advent of Ray Arden’s commercial miniature glow-plug. The consequent general switch by North American modellers to the new form of ignition forced the introduction of the Hurricane 24 “Hot Top” glow-plug model.

Two further minor variants of the Hurricane 24 followed in 1945, along with a very few examples of a short-lived .198 cuin. spark ignition design which followed a generally similar design layout. In January 1946 the first of three successive “Super Hurricane 24” variants appeared with their “trademark” streamlined cooling fin profile. These Super Hurricane .24 cuin. spark ignition models remained in production into 1948, hence being manufactured in substantial numbers. However, their run came to an end in early 1948 with the advent of Ray Arden’s commercial miniature glow-plug. The consequent general switch by North American modellers to the new form of ignition forced the introduction of the Hurricane 24 “Hot Top” glow-plug model. A far less well-known Canadian product was the

A far less well-known Canadian product was the  Another small-scale but still noteworthy Canadian effort was the

Another small-scale but still noteworthy Canadian effort was the