|

|

Team Racing at the 1960 World Championship - A Fair Result, or ….?!?

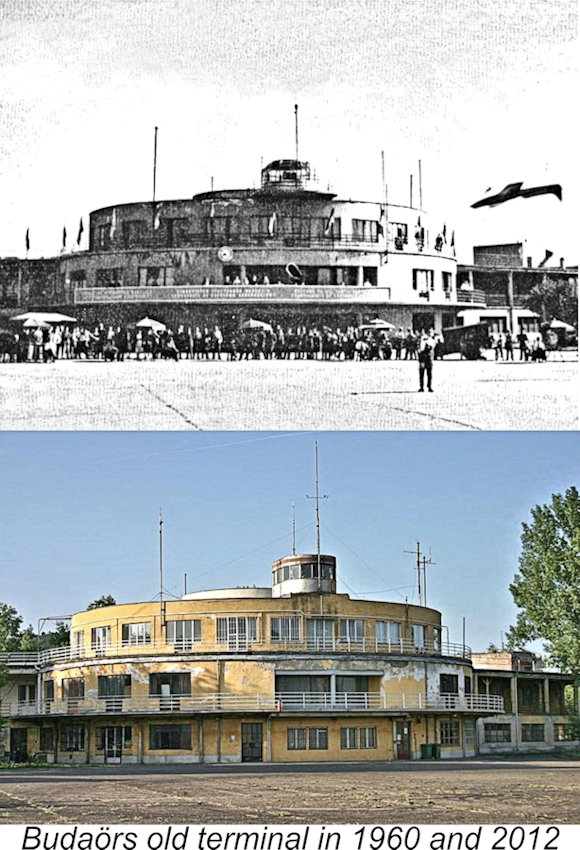

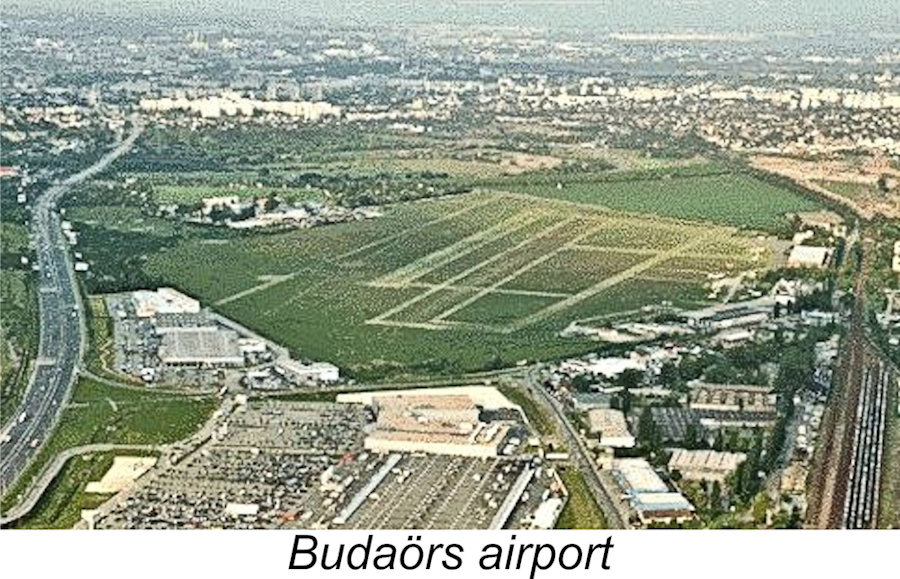

By all accounts, the organization and facilities were superb, but the officiating was quite another story………… In a separate article about the classic Super Tigre models, I wrote at length about the Speed competition which took place at this meeting. Those who have read that article will recall that the results of that competition were sadly marred by a blatant failure to enforce the rules, allowing first place to be awarded to an entrant who had flagrantly and openly broken the rules for all to see. This robbed the true winner (Bill Wisniewski of the USA) of his well-deserved trophy. I've since re-told this story in more detail in a separate article which may be found elsewhere on this website. Unfortunately, the team race event at the same 1960 meeting was also marred by flagrantly inconsistent and seemingly biased application of the rules. This inconsistency resulted in yet another distortion of the results along the same lines as that which marred the outcome of the Speed event. In this article, I’ll recount the equally unhappy story of the 1960 team race contest. A condensed version of this story appeared in the January 2021 issue of "AeroModeller" magazine. The following text expands upon that earlier article, also being more profusely illustrated. I must apologise for the indifferent quality of some of the illustrations, but many of them are all that we have after the passage of over 60 years! For many participants, it was a long trip to Budaörs, a small Hungarian town which was (and still is) in effect a suburb of nearby Budapest. When they arrived, the teams were quite impressed by the facilities laid on by their genial hosts. The event was to take place at Budaörs airport, which had been Hungary’s only international airport from its establishment in 1937 until the 1950 transfer of International services to Budapest Ferihegy International Airport (now Ferenc Liszt International Airport). Thereafter, Budaörs airport served as the home base of the Hungarian Aero Club, becoming Hungary’s main centre for non-commercial pilot training, sport flying, gliding and skydiving. It continues to host such activities right down to the present day.

Memories of the disastrous consequences of unrestrained whipping and high flying at the 1959 Criterium d’Europe team race event at Brussels in Belgium were still fresh. People also recalled the fact that Kjell Rosenlund of Sweden had been disqualified from the final at that meeting because of a tank which was declared to be fractionally oversized during post-race processing (but not when first checked during pre-race processing). What made this appear very suspicious was the fact that the tank used by Nery Bernhard of the host country Belgium was also found to be oversized during post-race processing but was subsequently “declared” to be legal, awarding Bernhard the host-country win. Everyone was hoping for more consistency in 1960. Alas for high hopes …………

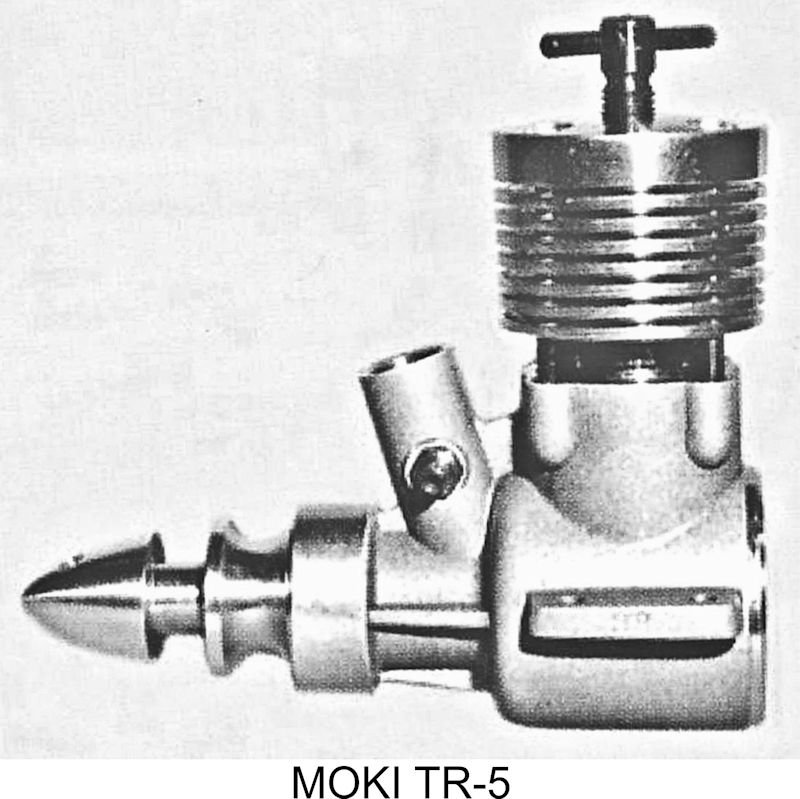

A total of 42 entries were received in the team race category alone. This event was particularly significant in that it saw the first full-fledged participation in international team racing from Eastern European nations. A noteworthy feature of the meeting was the close camaraderie which developed very quickly between the Western and Communist-bloc entrants, who collectively chose to ignore political and Many new engines were now appearing in the hands of top-flight competitors to challenge the established Oliver Tiger supremacy. Apart from the still-dominant Oliver Tiger Mk. III’s, there were several MOKI TR-5 engines (basically Oliver copies) from the host country along with three RITM drum valve diesels from Ukraine, an Oliver-style unit by Paul Bugl of Austria, the ETA 15D Mk. I from Britain (making its first international appearance), the MVVS 2.5 D-TR/1958 from Czechoslovakia (now the There was even a glow-plug powerplant in the shape of a Cox Olympic entry from the Edwards father-and-son team representing the USA. This was the first occasion on which a glow-plug engine had appeared at an international team race With a heavy entry list covering all three event categories, it was obviously Unfortunately, the rather loose wording of the no-whipping rule encouraged some entrants to “bend” the rule by flying left-handed, in which situation it was a simple matter both to whip quite hard and shorten the effective line length without appearing to do so. There was considerable negative comment on this behaviour, but unfortunately the event officials took no immediate action to control it during the heats despite the fact that it clearly contravened the intent, if not the letter, of the rules. Perhaps the most effective users of this technique were the Belgian team of Bernard and Lietzmann - they were certainly the chief beneficiaries. Nery Bernard had long been one of the foremost exponents of whipping, Things got off to a good start for the British team when Ken Long and Les Davy returned a fine time of 4:57 using their new ETA 15D Mk. I. However, British hopes were somewhat dampened by the first attempt by the Rivers-powered team of Mike Smith and Dave Balch. Since they had been regularly turning in times of around 4:40 at home, they were expected to be a powerhouse at this event. However, they could only manage 5:38 in their first heat at Budaörs. The Brits needed a lift, and they got it with Gordon Yeldham and Charley (“Chas”) Taylor's world-class 4:45 using the Steward Special.

During this round, a number of pit men were observed momentarily putting one foot over the line while retrieving their models for servicing and re-starting. Although it was technically a contravention of the rules, this behaviour did not affect the outcome in any meaningful way. Hence no-one was protesting and the officials The fun and games really got started in Round 2. Yeldham and Taylor were drawn to fly with Bernard and one of the Italian entries. Shortly before the first pit stop was due, the slower Italian model was touched by Bernard's as he was overtaking very low, breaking the Italian's prop and putting him down and out. Yeldham's motor cut on schedule a few laps later and as pilot Chas Taylor was bringing the model in on the glide Bernard came over again very low, forcing Taylor's model prematurely into the ground. The model consequently rolled under the downed Italian's lines, becoming entangled and wrenching the handle from Taylor's hand. When Bernard landed it was announced that there would be a re-run, which seemed fair enough to all concerned. However, it was then announced that Yeldham and Taylor were out - disqualified for becoming embroiled with the downed Italian! In view of the fact that he had been forced into the ground by Bernard’s low-flying tactics which had also caused the initial Italian crash, this seemed very unfair since Bernard was not penalized in any way despite clearly having caused the entire incident. However, the British team very graciously declined to protest, accepting the ruling. Their first-round time was looking good enough to get them into the final in any case, so they sportingly stood aside to allow Bernard his re-run. A fateful decision, as matters turned out! To reach the final, Bernard had to beat Ken Long’s first-round time of 4:58. In the re-run the Italian crashed within a few laps, leaving Bernard a clear run. He took full advantage, whipping and line-shortening to the max with his left-hand technique to record a time of 4:35 - the fastest time of the meeting, and one only attainable by whipping, etc. using the equipment at his disposal. Again, there was no Dave Balch’s woes continued in the second round, first from a false start and then from a broken prop, ending up with an uncharacteristically dismal time of 6:54. Rosenlund was unable to improve on his first-round time, but even so no-one else could approach the leading times. This left the following day’s final to be fought out between Bernard, Rosenlund and Yeldham, these having set the three fastest heat times by one means or another.

At that juncture, the second heat incident was repeated in every detail - Bernard came up behind Yeldham’s far too low, forcing the British model into the ground at speed. This time, the impact was sufficiently hard to bend the wire monowheel strut backwards, also stopping the engine. Yeldham retrieved the model and attempted to straighten the bent wire, but it was too strong. This provides some indication of the force with which the model had been knocked into the ground. After re-starting the Steward Special, Yeldham released the model, but the misaligned monowheel ran it straight into the circle where it nosed over and stopped, even being out of reach with the retrieval “fishing rod” bamboo cane which team manager Dick Edmonds had brought along for such contingencies (devices of this sort have since been banned). Yeldham and Taylor were out. Having thus disposed of one adversary, Bernard carried on. However, being unable to whip thanks to the right-hand flying requirement, he was unable to keep pace with the clean-flying Rosenlund and Bjork, who retained and extended a convincing lead to the end, setting a time of 4:48 compared to Bernard’s 5:06. The difference between Bernard’s left-hand second heat and right-hand final times clearly demonstrated for all to see how much of his second-round 4:35 time was the result of his left-handed whipping strategy in contravention of the rules. If set in that second heat, his 5:06 final time wouldn’t have even got him into the final …………

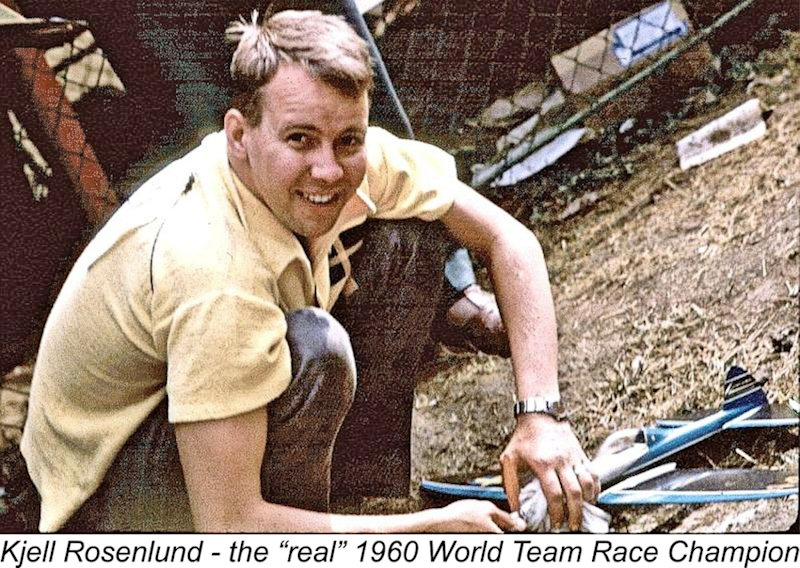

Meanwhile the post-event celebrations had been going on, with official congratulations to a pair of worthy winners as well as official photographs and even a radio interview. It was only after all of these festivities had been completed that Rosenlund and Bjork were informed that they had been disqualified from the final, leaving Bernard to accept the uncontested “win”. Kjell freely admitted having put one foot over, keeping the other well back. However, he noted correctly that others had been doing the same thing throughout the meeting without penalty. The watching officials had seen nothing meriting any action on their part. This being the case, did Rosenlund’s action really constitute an infringement meriting his disqualification? He had done nothing that others had not done without penalty and had no more entered the circuit than he would have done by reaching out an arm! More to the point, the incident had no bearing whatsoever on the outcome of the race given the handsome 18 second margin by which Rosenlund and Bjork won. Needless to say, this very unpopular and manifestly unjust ruling resulted in heated discussion among those in attendance. Everyone (no doubt including Bernard) knew who had really won the event, and Bernard’s acceptance of the trophy under these circumstances was widely seen as doing him no credit at all, especially considering that his equally questionable win in 1959 had come after he was found to have used an oversized tank but was still awarded the trophy while Rosenlund was disqualified for the exact same offence. The British team members were so incensed that they lodged a formal protest against Bernard for causing Yelham’s model to crash contrary to Rule 4.10.14, now 4.3.8.2 b). Unlike the Belgian protest of Rosenlund’s clear-cut win, the well-founded British protest was ignored. As had been the case in 1959, a powerful smell of fish pervaded the air ........... The subsequent Editorial by Norman Butcher (who had attended the meeting) which appeared in the November 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft” accurately reflected the general response to this incident, pulling no punches in doing so. After praising the organization very highly, Butcher continued his commentary with the following statement: "Unfortunately, full enjoyment of the meeting was marred by the unsporting behaviour of some competitors and the incomprehensible, inexact, contradictory, ambiguous, inept and, as it seemed to us, in some cases defititely biased decisions arrived at by F.A.I. officials and even the jury! Constant behind-the-scenes wrangling, protests and "bombshell" rule interpretations were extremely distasteful to all modellers who consider our hobby a sport where, given an equal chance, the best man wins". After characterising Rosenlund’s win as “fair, clean and very convincing”, Butcher categorized the Belgian protest as “to say the least, shattering”, also expressing the view that “(The fact) that such a protest should be accepted leaves us speechless”. Strong words indeed! After noting the official indifference to the far better-founded British protest against Bernard and then commenting on the equally dismal officiating in the Speed event, the writer made the following statements: “We are strongly of the opinion that all countries who consider aeromodelling a worthwhile sporting hobby should seriously consider whether the expense of sending teams to World Championships, where situations such as we have just described (may arise), is justified". "We have no wish to labour our point, but for years weaknesses of F.A.I. administration have been apparent to us; also, on the part of certain officials, a national bias which is deplorable. In the past these things have been glossed over or ignored by all model magazines, but the incredible happenings in Hungary have, as far as we are concerned, proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back. The time has come to stand up, not only for the rights of the average flier, but far more importantly, for the future and integrity of international competitions”. "When F.A.I. officials realize that they are there to represent the contest flier, not to act as little tin dictators, the biggest hurdle will be crossed".

Like Ugo Rossi in the Speed event, Bernard slunk away from the meeting with the trophy but with his (and Belgium’s) sporting reputation in tatters as far as most observers were concerned. One wonders how he really felt inside and what he thought his “win” proved. Rosenlund's stoic acceptance of his clearly biased disqualification totally shamed the attitude of his adversary. Coming on top of his disqualification from second place at the previous year’s Criterium d'Europe on equally dubious grounds, this must have been doubly hard to bear. However, Rosenlund refused to stoop to the same level as his opponent. In any case, everyone knew who the real champion was - everything but the trophy belonged to Rosenlund and Bjork. Only the Belgians and the FAI officials recognized Bernard as the 1960 World Team Race Champion. Perhaps the defining feature of this meeting was the yawning gulf between the superb standard of organization and the dismal failure of the event officials to enforce and interpret the rules consistently in a manner which saw the Championships fairly awarded to the most capable competitors. That after all is what rules are meant to achieve! The Hungarians had obviously expended considerable time and energy in the pre-contest organisation of this event and were rewarded with a standard-setting meeting which was a model of organizational efficiency. The fact that the event officials failed to match their standards must have been a great disappointment to many of the organizers, who honestly did their very best. My late Hungarian friend Ferenc "Somi" Somogyi was one of those organizers, and he still recalled the general sense of let-down after over 50 years. If there are lessons to be learned from this story, they are a) that rules are there to be enforced: b) that they have to be enforced uniformly; and c) if they’re not going to be enforced at a given meeting, that lack of enforcement has to be applied consistently to all competitors. If these principles had been followed, Bernard would have been disqualified both from his second heat and from the final (which he wouldn’t even have made if disqualified from the second heat), while Rosenlund’s well-deserved win would have been allowed to stand. In both cases, justice would have been well served.

It’s nice to be able to report that in 1961 Rosenlund and Bjork finally achieved their very well-deserved and unfairly denied Championship title with a fine 4:40 time The superb facilities at Budaörs were to be used once again for the 1964 event. That event was happily largely free from controversy of the kind which had marred the international debut of that fine venue. The Hungarian organizers must have breathed a sigh of relief! Kjell Rosenlund and Bork returned to Budaörs for that 1964 event, finishing 9th on that occasion while still using their beloved Oliver Tiger. This was the team's final appearance at a World Championship meeting. As of 2023 the old terminal was still in existence, although it had been closed to the public. It is listed as a protected historical monument along with the adjacent original main hangar. The airliner parking apron on which the 1960 stunt competitors displayed their abilities is still there, as are the somewhat crumbling and overgrown remains of the two paved circles used in 1960 and again in 1964 for the team race and speed events. I bet that it would be impossible for any true enthusiast to stand in front of that old building and not conjure up the sound of an engine working at full stretch, or catch a faint scent of burning ether or nitro on the breeze .................. ___________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, BC, Canada First published here December 2023 |

| |

1960 was a big year for international team racing. For the first time, the major annual international event in Europe was to be accorded full World Championship status by the FAI. This first-ever official FAI Control Line World Championship meeting was held at Budaörs, Hungary on September 8

1960 was a big year for international team racing. For the first time, the major annual international event in Europe was to be accorded full World Championship status by the FAI. This first-ever official FAI Control Line World Championship meeting was held at Budaörs, Hungary on September 8 First-rate accommodations were provided at three of Budapest’s best hotels, with buses laid on to transport teams to the contest venue.

First-rate accommodations were provided at three of Budapest’s best hotels, with buses laid on to transport teams to the contest venue. Although unused for its original purpose, the former main terminal building had been given over to the use of model aircraft organizations who had the use of the field. For the 1960 international event, the building had been re-decorated and arranged to serve as a dining room for the 250-odd individuals in attendance. Two new superbly-paved circles had been laid out beside the terminal building complete with safety netting, electrically-controlled team race lap clocks operated by the lap counters, a timekeepers' box, etc. These circles are still to be seen in the accompanying latter-day aerial photo of the old terminal area. The third smaller circle is a tether car track which was constructed at the same time.

Although unused for its original purpose, the former main terminal building had been given over to the use of model aircraft organizations who had the use of the field. For the 1960 international event, the building had been re-decorated and arranged to serve as a dining room for the 250-odd individuals in attendance. Two new superbly-paved circles had been laid out beside the terminal building complete with safety netting, electrically-controlled team race lap clocks operated by the lap counters, a timekeepers' box, etc. These circles are still to be seen in the accompanying latter-day aerial photo of the old terminal area. The third smaller circle is a tether car track which was constructed at the same time.  The concrete apron in front of the terminal building which had formerly been used to park visiting airliners was available for use by the stunt fliers, leaving the two specially-prepared paved circles free for use by others. Nothing was lacking for a great contest!

The concrete apron in front of the terminal building which had formerly been used to park visiting airliners was available for use by the stunt fliers, leaving the two specially-prepared paved circles free for use by others. Nothing was lacking for a great contest!

ethnic divisions completely. Some of our present-day leaders could learn from their example!

ethnic divisions completely. Some of our present-day leaders could learn from their example! Czech Republic) and a one-off British prototype called the “Steward Special” which had been designed and constructed by Len Steward of

Czech Republic) and a one-off British prototype called the “Steward Special” which had been designed and constructed by Len Steward of  event. The engine didn’t disgrace itself by any means, matching the range but not the speed of the best diesel models. Moreover, the pit work of "Pop" Edwards was first class. He carried the starting battery in his pocket with the leads running down his arm to contacts on thumb and forefinger, while a stout leather glove on his starting hand enabled him to stop the reed valve motor if it started backwards. The pair were ultimately rewarded with a very creditable 5:38 best heat time, good for 14

event. The engine didn’t disgrace itself by any means, matching the range but not the speed of the best diesel models. Moreover, the pit work of "Pop" Edwards was first class. He carried the starting battery in his pocket with the leads running down his arm to contacts on thumb and forefinger, while a stout leather glove on his starting hand enabled him to stop the reed valve motor if it started backwards. The pair were ultimately rewarded with a very creditable 5:38 best heat time, good for 14

Apart from a few such exceptions, times were a little disappointing all round, with few teams matching their typical “home” times and only three entrants getting down into the 4 minute bracket in this round - Long, Yeldham and Kjell Rosenlund of Sweden, whose Oliver-powered 4:39 was the fastest heat in this round. Nery Bernard’s Ollie was drastically under-compressed and could only manage 6:18, while none of the MOKI-powered Hungarians could break 5 min on their home turf.

Apart from a few such exceptions, times were a little disappointing all round, with few teams matching their typical “home” times and only three entrants getting down into the 4 minute bracket in this round - Long, Yeldham and Kjell Rosenlund of Sweden, whose Oliver-powered 4:39 was the fastest heat in this round. Nery Bernard’s Ollie was drastically under-compressed and could only manage 6:18, while none of the MOKI-powered Hungarians could break 5 min on their home turf.

The team race final was the last event of the entire meeting and certainly served up a healthy dose of both excitement and controversy. The officials had finally responded to the complaints about left-handed flying, forcing Bernard to fly right-handed. All three entrants got immediate starts, putting things on an even footing. Rosenlund had a very slight speed advantage, but it was still anyone’s race. At the 22 lap mark, with the first pit stops approaching, Rosenlund was a lap ahead of second-place Yeldham, who had a slight lead over Bernard.

The team race final was the last event of the entire meeting and certainly served up a healthy dose of both excitement and controversy. The officials had finally responded to the complaints about left-handed flying, forcing Bernard to fly right-handed. All three entrants got immediate starts, putting things on an even footing. Rosenlund had a very slight speed advantage, but it was still anyone’s race. At the 22 lap mark, with the first pit stops approaching, Rosenlund was a lap ahead of second-place Yeldham, who had a slight lead over Bernard. The two Swedes had won the Championship fair and square……… or so everyone believed. However, it was now that sporting ethics were displaced by ruthless expediency. Someone associated with the Belgian contingent had noted one of Kjell's feet momentarily crossing over the line while retrieving the model during his second pit stop (at which point he was six laps ahead). A protest of the result was lodged by the Belgians.

The two Swedes had won the Championship fair and square……… or so everyone believed. However, it was now that sporting ethics were displaced by ruthless expediency. Someone associated with the Belgian contingent had noted one of Kjell's feet momentarily crossing over the line while retrieving the model during his second pit stop (at which point he was six laps ahead). A protest of the result was lodged by the Belgians. This was a pretty direct challenge to the FAI from an influential source - clean up your act or risk the future of the World Championships.

This was a pretty direct challenge to the FAI from an influential source - clean up your act or risk the future of the World Championships.