|

|

The 1960 World Speed Championship – a Stolen Title

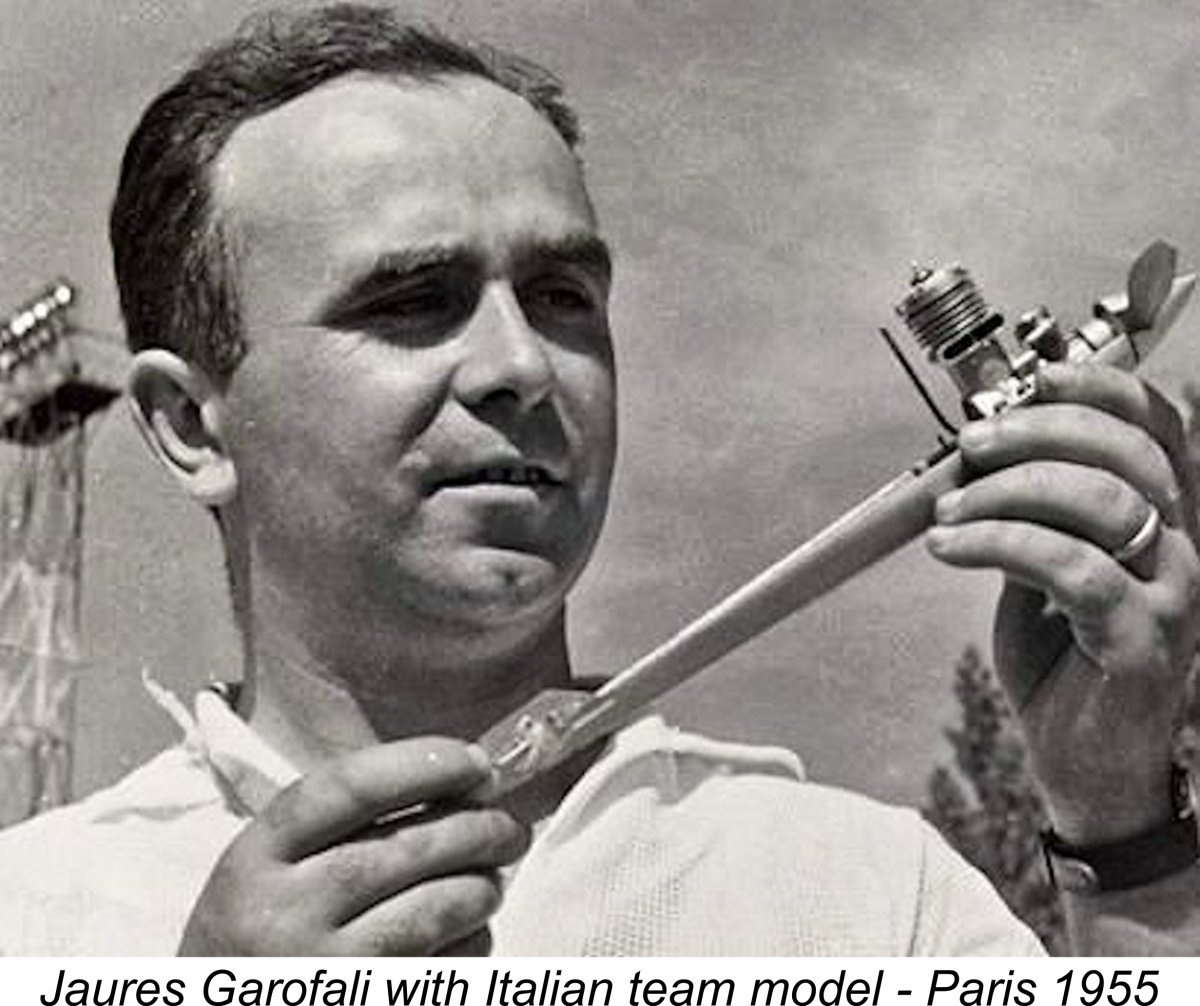

During the 1950’s, the development of high-performance 2.5 cc glow-plug motors suitable for use in the international competitions sanctioned by the FAI proceeded at a rapid pace. A leader in this endeavor was Jaures Garofali, designer and manufacturer of the famous Super Tigre range through his Micromeccanica Saturno company of Bologna, Italy. Beginning in 1950, Garofali pursued a continuous program of development of his 2.5 cc G.20 competition glow-plug design. It was not until 1955 that the FAI adopted the 2.5 cc displacement as the international standard for control-line categories other than stunt. By that time, Garofali had produced the excellent Super Tigre G.20 S model with which to compete. He arrived at the Paris venue for the 1955 World Speed Championship contest fully expecting to win both the individual and team titles.

Despite his best efforts, the pinnacle of success continued to elude Garofali as the 1950’s drew on. The 1956 title went to Ray Gibbs of England using the McCoy 19-based Carter Special powerplant. MVVS ruled the roost in 1957, while the Hungarians took the two top places in 1958 with their new State-sponsored MOKI S-1 motors, with MVVS filling the next three places. Garofali was doubtless becoming more than a little frustrated by this time!

The significance of this result was somewhat tempered by the fact that the powerhouse MVVS works team did not contest this event, being fully occupied in getting a few of their designs into limited series production as they began the transition from a State-sponsored tool-room operation to a commercial manufacturer. In addition, MVVS Director Zdeněk Husička was then recovering from a heart attack. Nevertheless, Super Tigre finally stood at the top of the heap! Having finally got there after years of effort, Jaures Garofali was naturally very keen indeed to stay there. Just how keen was soon to become glaringly apparent!

With a heavy entry list covering all three event categories, it was obviously going to be a crowded three days. However, the organisation was well up to the challenge of making the meeting run very smoothly with minimal hold-ups or delays. Stunt was run on all three days, with the first two rounds of Speed on the first day, the Team Race heats on the second and the third Speed round and Team Race final on the third and final day.

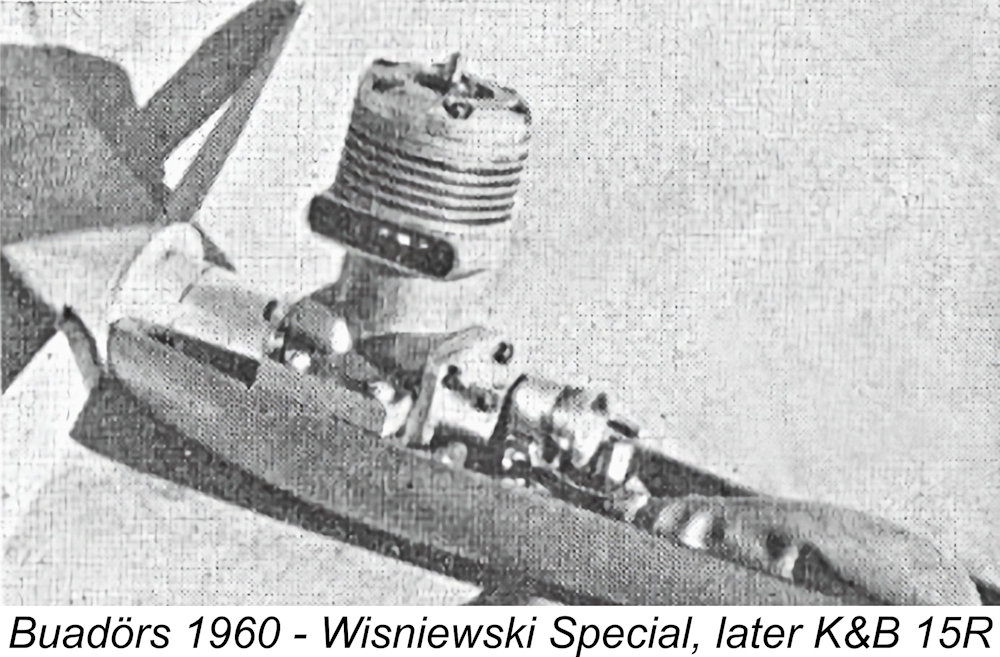

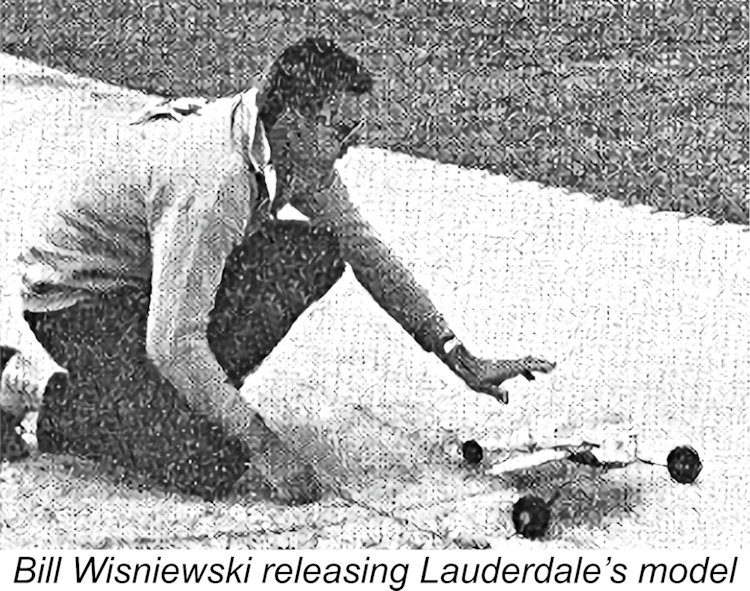

Now all of the top speeds in previous years had been achieved using two-line models. For 1960, the FAI had inspected and approved the monoline systems which had been developed by both the Czechs and Americans. Accordingly, both of these teams brought monoline models to this meeting, as permitted by the prevailing rules. Their models all passed both technical inspection and pull-testing prior to the commencement of the event itself. Despite experiencing some needling difficulties on his first flight, Wisniewski still managed to complete the distance at an average speed of 230 km/hr (142.92 mph) on monoline using a fuel containing the very effective but dangerous (and soon to be rightly banned) tetra-nitromethane along with the carcinogenic nitro-benzene, also soon to be banned. Bill later recalled that this behavior was typical of motors using a fuel having a tetra-nitromethane content – it made the engines almost impossible to needle. They would run like smoke for a few laps and then sag for the rest of the flight, if they didn’t self-destruct! During the brief period when the motor was running at full chat prior to sagging, observers estimated that Wisniewski's "Pink Lady" model was doing close to 257 km/hr (160 mph) with the motor revving to over 20,000 RPM!

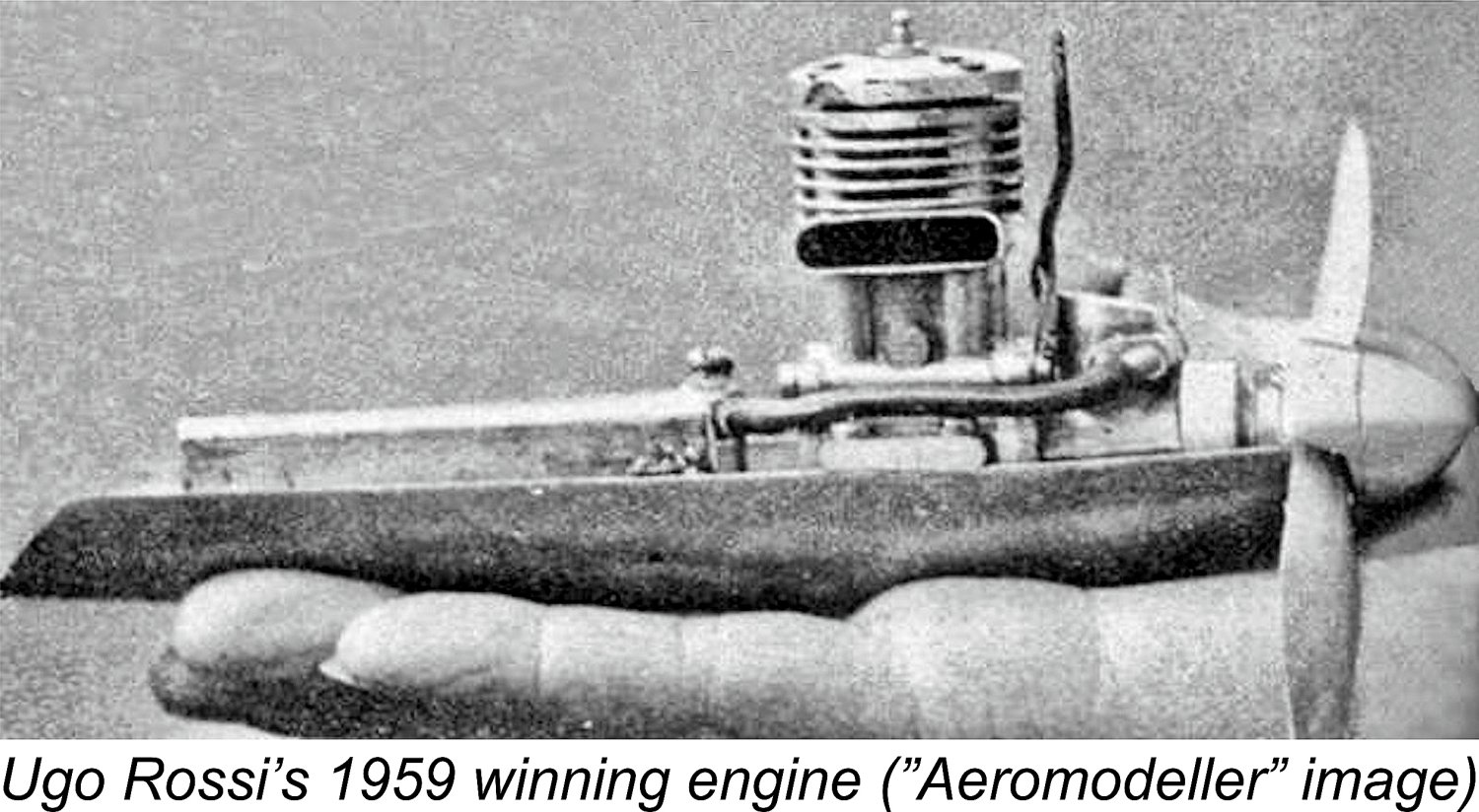

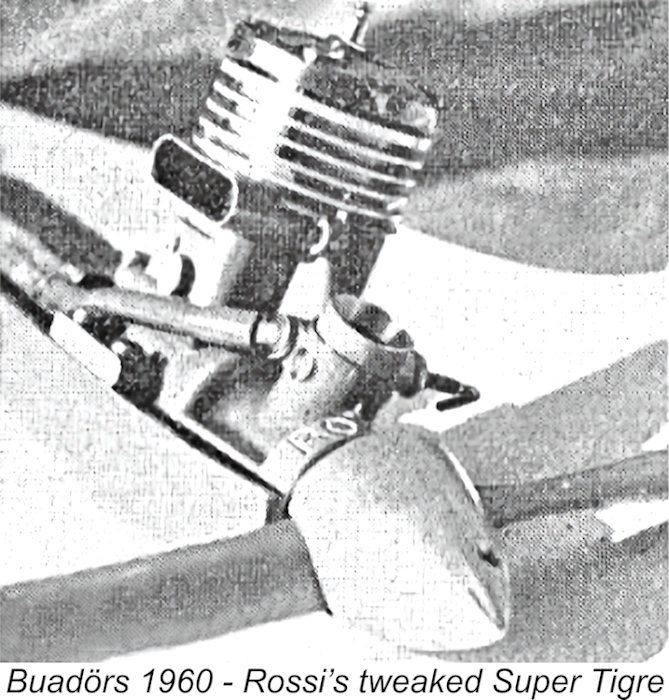

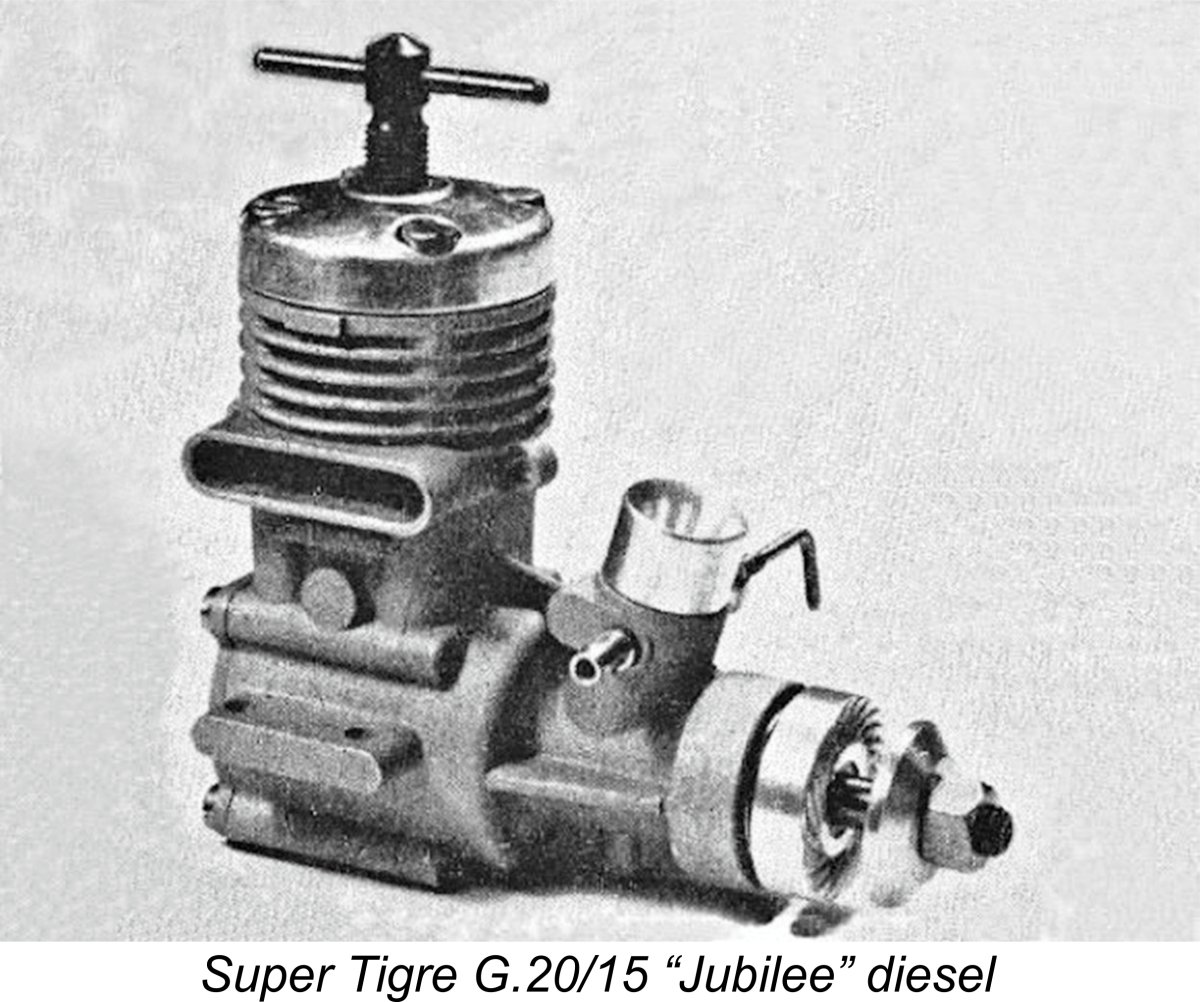

The MVVS-powered Czech team elected to fly their two-line models in the first round, with both Pech and Kočí returning identical (and very creditable) speeds of 213 km/hr (132.35 mph). Ugo Rossi’s first-round speed flying very fairly without whipping or line-shortening was an even more creditable 219 km/hr (136.08 mph). The first round concluded with the Americans occupying the first three places. To rub salt into the wound, one of them (Lauderdale) was using an Italian motor! Sadly, this situation brought out the worst in the Italian team, whose need to win evidently sank their sense of fair play and sportsmanship without trace. Recognizing immediately that their two-line models powered by works-tuned prototypes of what would become renowned as the Super Tigre G.20/15V “Jubilee” could not match the American speeds without assistance, the Italians immediately protested the Americans’ use of monoline despite the previously-noted fact that it had been formally accepted by the FAI well in advance of the meeting and had been inspected and approved by event officials at Buadörs prior to the first round. The fact that this protest was only lodged after the first round instead of at the outset revealed its motivation all too clearly. If you can’t beat a competitor fair and square, search for ways to eliminate him!! The Italian argument was evidently based on the idea that as "sole users" of the monoline technology at this event, whether legal or not, the Americans were playing on a tilted field. Incredibly, this absurd protest was initially upheld, giving an unsavory appearance of the fix being in. A number of teams at the meeting registered their strong disagreement with the ruling, to the extent that several threatened to withdraw if the ruling was upheld. However, it was left to the Czech team to directly underscore its unfairness by bringing out their own previously-approved monoline models for the second round, thus making the point that the technology was available to all, including the Italians if they so chose, and that the Americans did not in fact have a monopoly on the technology, even at this meeting. To further underscore the point, their switch did not improve their second-round speeds sufficiently to threaten the Americans. As a result of this very sporting action by the Czechs, the use of monoline at the meeting was reinstated, since the Czech action had demolished the “monopolistic” basis for the Italian protest and the only alternative would have been to disqualify both the Americans and the Czechs on non-existent grounds. The threat of withdrawal by several other teams doubtless played a part in influencing this decision, since if the ruling had been Wisniewski’s 230 km/hr speed stood up through the first two rounds, appearing to be more than good enough to win. Lauderdale switched to a Craig Asher Howler 15 for the second round, but this proved to be unduly sensitive in terms of the needle setting, although it was clearly very powerful. He was only able to record a second-round speed of 174 km/hr (108 mph) with the engine running lean and sagging throughout most of the flight. By virtue of energetic whipping during his second-round flight, Rossi improved to 227 km/hr. However, this was still short of the best speeds recorded by the Americans and Czechs. By now the Italian team were clearly prepared to do anything to avoid enduring yet another international meeting without a win. Having failed to persuade the officials to disqualify Wisniewski, and having then found that even strenuous whipping (which was allowed under the rules) couldn’t better Wisniewski’s mark, they resorted to outright cheating. Ugo Rossi’s third flight was marked by a degree of model assistance so extreme that Rossi was actually wrapping his lines around his own shoulder, thus shortening them, as the attached image from “Model Aircraft” clearly shows. Incredibly, his speed of 236 km/hr (146.65 mph) produced in this manner was allowed to stand as the winning mark despite having been produced by flagrant line-shortening in clear contravention of the rules.

The British team lodged an official protest on this basis, but this was ignored by the officials without response. The impression of the fix being in was now so marked as to taint the entire meeting, especially when considered along with the equally dismal failure of the team race officials to enforce the rules for that event (see below). When the dust settled, the upshot was that Rossi had not won the title - it had been awarded to him by the FAI Jury in direct contravention of the rules which they were supposed to enforce. When coupled with the equally dismal and biased officiating in connection with the parallel team race event (see below), the impression of the fix being in was now overwhelming, with the sporting reputations of Italy, Belgium (in the team race event) and the FAI in tatters. This view of the matter was reinforced by the clear general recollection that Ugo Rossi's brother Cesare had been disqualified from the second round of the 1958 meeting for line-shortening using an outrigger attached to the handle, while Czech team member Kočí had also been disqualified in 1958 for using exactly the same line-shortening technique that Ugo Rossi used in 1960! If Kočí's action was illegal in 1958, then why wasn't Rossi's identical action just as illegal in 1960?!? Given the 1958 precedent, the inescapable impression among those at the 1960 event was that the Italians must have received assurances from the FAI Jury in advance that Rossi's third-round tactics would not lead to his disqualification despite their clear illegality. Otherwise, it seemed inconceivable that he would court disqualification by flying in this overtly illegal manner for all to see – he must have known beforehand that any protest would be rejected.

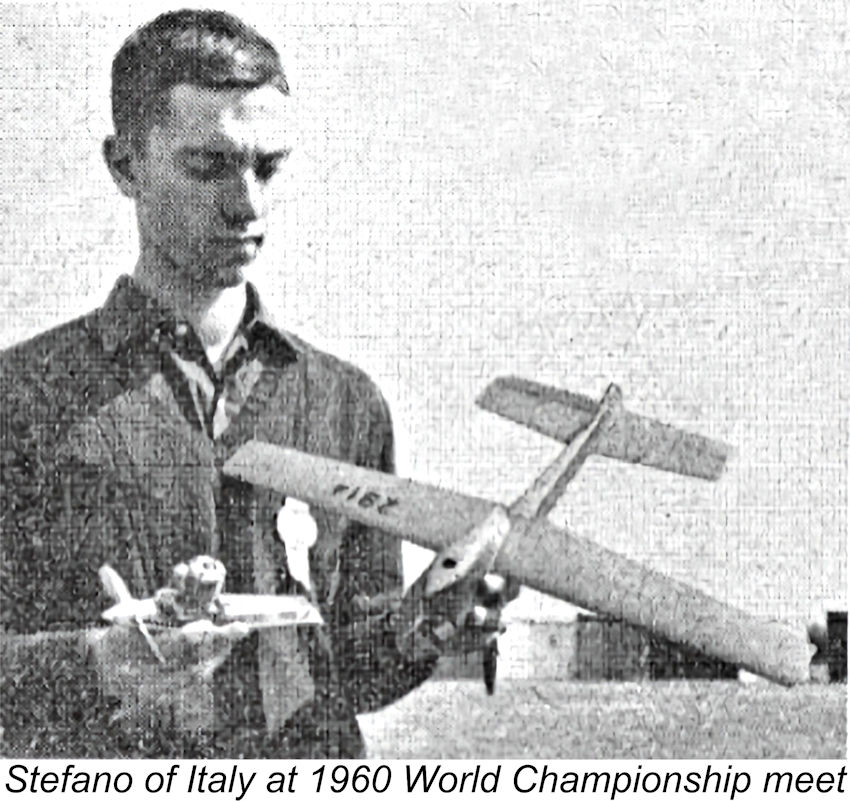

Rossi’s best speed of a very creditable 219 km/hr (136.08 mph) without whipping and line-shortening would have given him seventh place in the final results behind the officially seventh-place Super Tigre entrant, Rossi's clean-flying Italian team-mate O. Stefano with a speed of 220 km/hr (136.70 mph). Stefano’s speed underscored the fact that this was about the best speed As matters transpired, although Ugo Rossi and Super Tigre went into the record books as the winning combination at this event, very few event participants or modelling enthusiasts worldwide recognized this result as legitimate. The widely-held view was that the Italians’ desire to win overwhelmed their sense of fair play and sportsmanship completely on this occasion. This unsavory incident remains the one blot on Jaures Garofali’s otherwise stellar reputation. I have personally always considered the great Bill Wisniewski to be the indisputable 1960 World Speed Champion, and I’m very far from being alone. The fact that Jaures Garofali and his colleagues accepted this “win” as legitimate undoubtedly did far more harm than good to the Super Tigre name as well as besmirching the sporting reputation of Italy, at least in the short term. Rossi slunk away with the trophy but with his reputation in tatters. Perhaps diplomatically, neither he nor his brother Cesare ever again contested a World Championship, instead focusing upon the development of their newly-established Fratelli Rossi engine tuning and speed accessory company of Cellatica which was to evolve into a notable model engine manufacturing business.

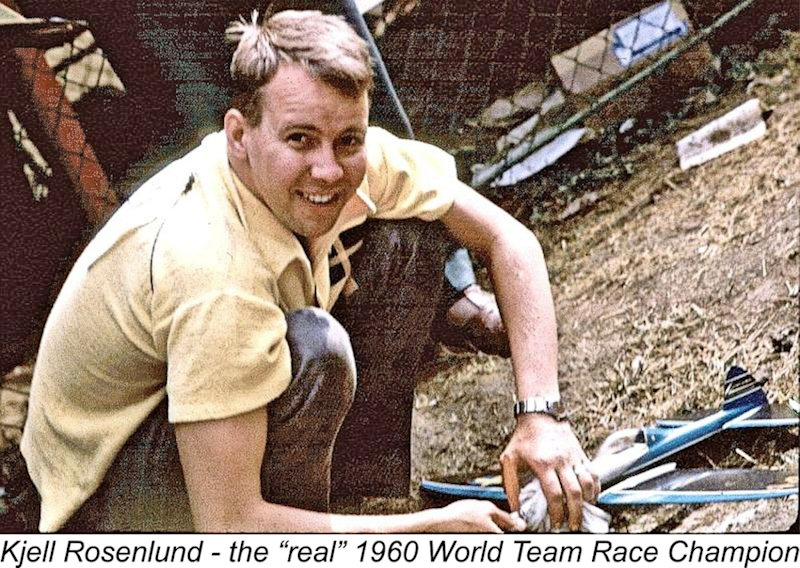

Sadly, the dismal failure of the officials to apply the prevailing rules in a manner which ensured fair play and yielded a worthy winner in the Speed competition was matched by a similar failure with respect to the team race World Championship contest run at the same meeting. A blatant failure to enforce a number of key rules coupled with a complete disregard for the impartial application of those rules that were enforced resulted in the true winners, Rosenlund and Bork of Sweden, In the end, the defining feature of this meeting was undoubtedly the yawning gulf between the superb standard of organization and the dismal failure of the event officials to enforce and interpret the rules consistently in a manner which saw the Championships fairly awarded to the most capable competitors. That after all is what rules are meant to achieve! The most disappointed people at the event must surely have been the Hungarian organizers, who had obviously expended considerable time, energy and money in the pre-contest organization of this event and were rewarded with a standard-setting meeting which was generally acknowledged by everyone in attendance as representing a model of organizational efficiency. The fact that the event officials failed to match their standards must have been a great disappointment to the organizers, who honestly did their very best. My late Hungarian friend Ferenc "Somi" Somogyi was one of those organizers, and he still recalled the general sense of let-down after over 50 years. He shared my firmly-held view that Bill Wisniewski was the true 1960 World Speed Champion. If there are lessons to be learned from this story, they are a) that rules are there to be enforced: b) that they have to be enforced uniformly; and c) if they’re not going to be enforced at a given meeting, that lack of enforcement has to be announced and justified prior to the meeting and then applied consistently to all competitors. If these principles had been followed, both Bill Wisniewski and Kjell Rosenlund would have received the titles and trophies which they richly deserved, while the two competitors who benefited from the officials’ failures wouldn’t even have made the podiums.

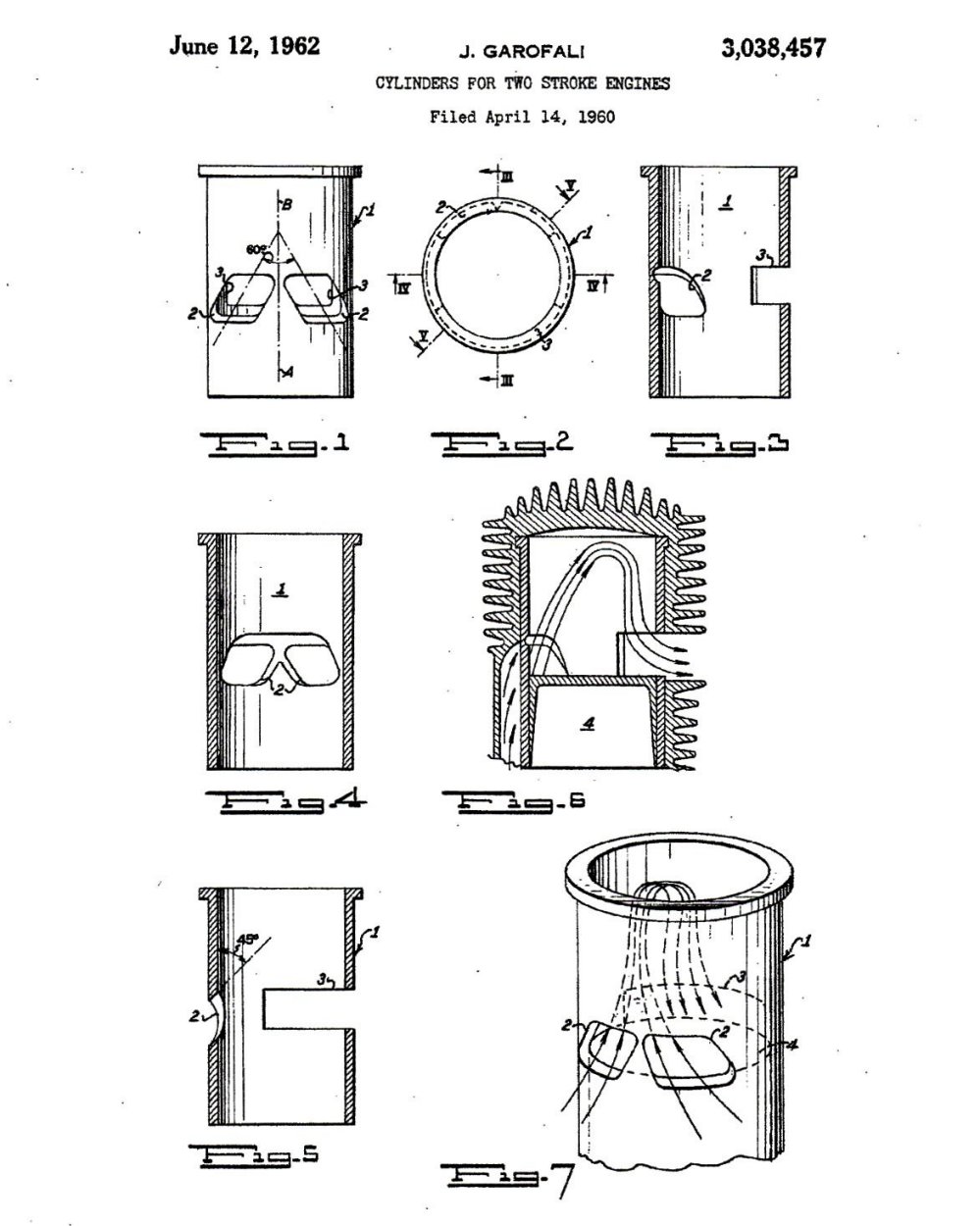

Happily, Johnny was able to throw a good deal of light on this issue. Many years ago, he had been fortunate enough to have had an in-depth discussion with Bill Wisniewski regarding this specific event. Bill was not the most talkative person under most circumstances, probably (in Johnny's opinion) because he was basically a rather shy individual. However, he did have an interesting and somewhat unexpected take on Rossi's "win", which he shared with Johnny. Bill Wisniewski was first and foremost an “engine guy”, working for John Brodbeck of K&B in that capacity. At the 1960 Championship meeting, Bill quickly formed the objectively-considered opinion that the Super Tigre G20/15V "Jubilee", tuned prototypes of which were used both by the Italians and by Bob Lauderdale at the meeting, was intrinsically superior to any baffle piston design, including Bill's own prototype K&B 15R units used at It was immediately clear to Bill that the Jubilee's porting and transfer arrangements together with a perfectly flat-topped baffle-less piston were far more efficient than anything else at the meeting. The accompanying drawing from the Garofali patent shows the essentials of the design very clearly. All things being equal, Bill honestly felt that Super Tigre had the best engine at the event. He evidently recognized that it was only the perfectly legal combination of monoline and tetra-nitromethane that had allowed him to record the speed that he did, thus beating the superior (in his view) Super Tigres. Bill also recognized the fact that even after the Czechs demolished the "monoline monopoly" argument, the Italians still viewed the USA team's use of tetra-nitromethane as a form of “cheating”. It was, of course, absolutely nothing of the kind - at the time in question there were no fuel restrictions. The "cheating" perception evidently arose because only the US entrants had access to tetra-nitro at the meeting. The Italian view of course flew directly in the face of Pech's third-round achievement in almost matching Wisniewski's best speed without the use of that additive. Once again, the Czechs had demolished the Italian argument (if one discounts the completely unsubstantiated possibility that the Americans had supplied them with tetra-nitro for their use in the third round). In reality, it appears highly unlikely that the Czechs used tetra-nitro at any stage of the competition. This is because the use of tetra-nitro was at best a mixed blessing. Speaking years later to Johnny Shannon, Bill recalled that it made the engines next to impossible to set. They ran like smoke for a few timed laps and then went irretrievably lean or blew up! This explained why no American entrant was able to record a clean run throughout the timed distance in any of the three rounds. In reality, the Americans were working against the handicap of using tetra-nitro! Bill's speed was achieved in spite of this handicap. This is actually a very strong argument against the possibility of the Czechs having used tetra-nitro in the third round. Its effective use would have required considerable practise/familiarization time, which the Czechs didn’t have. The problem with the “fixing” of the results arose entirely because the Italians were unable to accept the fact that the Americans had achieved the results that they had simply through the application of completely legal leading-edge fuel and flight control technology. That after all is how World Championships are won - find an edge and use it!! The Italians had certainly done so with their ground-breaking new cylinder porting technology. For his part, Bill was able to recognize and acknowledge the merits of the radically different cylinder porting of the Super Tigre G.20/15V as just such an example of leading-edge technology – a sharp contrast to the attitude of his Italian competitors. Yet neither he nor anyone else protested the Italians on the basis that they alone had this technology. By contrast, the Italians were unable to recognize and acknowledge Bill's fuel and flight control technologies in the same light, hence responding to Bill's legally-established speed from the first round by resorting first to an ultimately unsuccessful protest, then to unrestricted whipping in the second round and finally to outright cheating in the third round, apparently with official connivance. They evidently viewed Rossi's line-shortening as an appropriate response to Bill's first-round performance, despite its clear illegality. It seems abundantly clear that the officials at the meeting must have been complicit in this travesty of sportsmanship. Given the fact that Bill's figure had been established in full compliance with the rules (as witness the fact that he was allowed by the officials to retain his "second place"), this was clearly an unacceptable response on the part of the Italians, and one that should have resulted in Rossi's immediate disqualification. Even so, Bill told Johnny that he could understand the Italians' frustration, especially given his own objective opinion that the Italians had the best engines at the meeting. Fair enough, but it's one thing to express frustration in words - it's quite another to express it by cheating. The British protest of Rossi’s final flight was presumably ignored by the FAI because the British team had no representatives who figured in the results, hence being unaffected by Rossi's action in Championship terms. However, there's little doubt that if as the individual most directly affected, Bill had officially protested Rossi's third flight, a disqualification would have resulted - the photographic and eye-witness evidence of Rossi's cheating was (and remains to this day) irrefutable. The fact that Bill refrained from lodging a protest reflects enormous credit upon his sense of sportsmanship - by remaining silent, Bill (not just the FAI) effectively awarded the championship to Rossi. As a die-hard engine man, he appears to have elected to allow what he personally considered to be the best engine to take the title. As an example of sportsmanship, this stands in sharp contrast to that displayed by the Italians.

In Luke's recollection from his direct interactions with the leading speed fliers of the era, the fall-out from the 1960 event (not just in America) was sufficiently serious among the international speed flying community that the entire future of the Championship was threatened for a time. This view was certainly endorsed by the Editorial staff of “Model Aircraft” magazine, which published a bluntly-worded Editorial statement on this contest in its November 1960 issue. After commenting on the inappropriateness of the Rosenlund exclusion from the team race event and noting the fact that Rossi’s winning flight unarguably broke at least two of the FAI’s Code Sportif rules, the writer made the following statement: “We are strongly of the opinion that all countries who consider aeromodelling a worthwhile sporting hobby should seriously consider whether the expense of sending teams to World Championships, when situations such as we have just described can arise, is justified”. The Editorial went on to state: “The incredible happenings in Hungary have, as far as we are concerned, proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back. The time has come to stand up, not only for the rights of the average flier, but far more importantly, for the future and integrity of international competitions”. As history records, the event did survive, but the rules were drastically revised for 1961 to require the use of straight methanol/castor fuel (ending any complaints about tilted playing fields); to explicitly homologate the use of monoline; and to expressly ban whipping outright. All of these measures were clearly intended to prevent a recurrence of the 1960 fiasco. However, despite the general opinion that the 1960 title had been improperly awarded, the official result of that contest was never reviewed and retroactively amended to reflect the true situation - an omission which stands to this day as a black mark on the FAI's record books. It's Luke Roy's personal opinion that the gross mishandling of this contest, including the FAI's inexplicable failure to set the record straight after the fact, had a permanent dampening effect upon the level of interest among US competitors in future FAI Championship event participation. Johnny Shannon’s discussions with Bill Wisniewski provided an interesting technical footnote to this story as well as suggesting another possible reason for Bill electing to allow the result to stand unchallenged. As noted above, Bill was most impressed with the Jubilee porting design, to the point that he very sportingly stood aside to allow it to "win" the contest. The thing that evidently impressed him most was the elimination of the piston baffle, which allowed for the creation of a far more efficient combustion chamber. When he got back to the USA, Bill immediately encouraged his employer John Brodbeck of K&B to try to reach a deal with Jaures Garofali to manufacture the patented cylinder design under license from Super Tigre. It appears that a desire to pave the way for a successful conclusion to such discussions may well have been a major reason for Bill’s allowing the result to stand rather than antagonize the Italians by protesting. If so, the strategy failed. Bill told Johnny that Brodbeck did make very serious and repeated attempts to reach a deal with Garofali, but with absolutely no success. Bill always believed that residual bad blood from the 1960 World Championships was a major factor in blocking any such arrangement. One would think that the Italians would feel some sense of gratitude towards Bill for not protesting Rossi out of the result, as he could easily have done, but seemingly not so ...........

Bill's first move was to complete the development of the production version of his 1960 prototype. This duly appeared in 1961 as the K&B 15R Series 61. Having completed that task, Bill set about developing his own baffle-less unit using cylinder porting borrowed from the two-stroke Luke Roy reckoned that Bill only returned that year in order to show Super Tigre and the others that there was more than one way to skin a 'gator! This provides us with the truly fascinating insight that it may well have been Jaures Garofali's refusal to collaborate with K&B in 1960/61 that led directly to the development of the next-generation Schnuerle-ported model racing engines, and by someone other than Super Tigre at that. Be careful who you wind up - they may return to haunt you!!

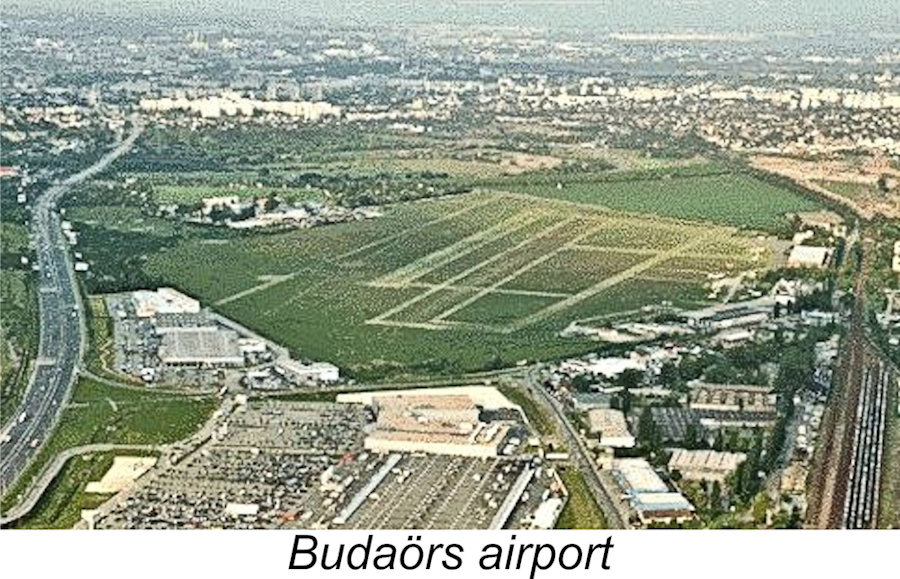

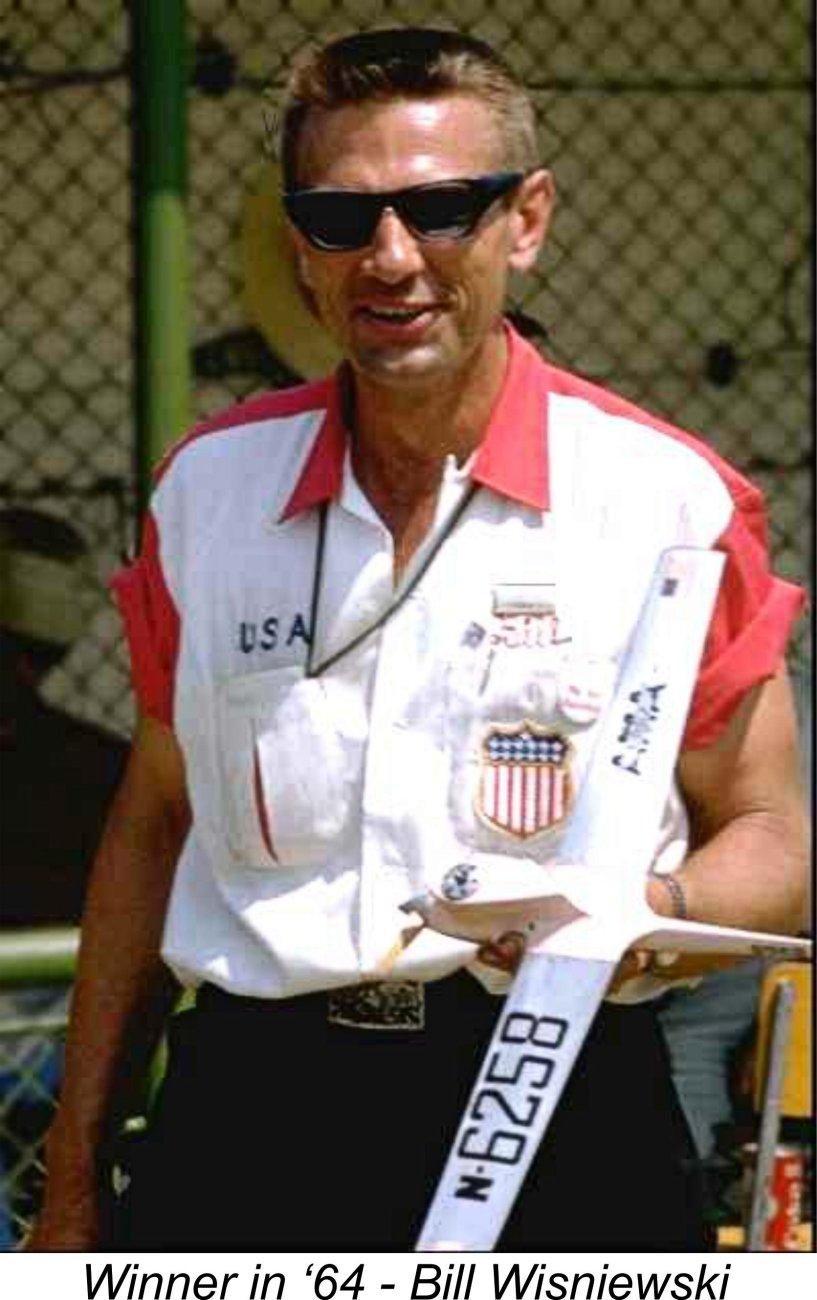

It's ironic to note that both Garofali and the Rossi brothers were among those who gladly adopted this innovation from the very man whom they had unapologetically cheated out of a title in 1960 and with whom they had been unwilling to share their technology. Bill capped this off with a fine second-place World Championship finish in 1968 behind his compatriot Arnie Nelson. As I said earlier, true greatness will not be denied, and the memory of true greatness will never fade ............... The superb facilities at Budaörs were to be used once again for the 1964 event at which Bill Wisiniewski finally won the Speed title that had been denied to him in 1960. That event was happily largely free from controversy As of 2023 the 86-year old Budaörs terminal was still in existence, although it had been closed to the public. It is listed as a protected historical monument along with the adjacent original 1937 main hangar, part of which is visible at the left in the accompanying image. The airliner parking apron on which the 1960 and 1964 stunt competitors displayed their abilities is still there, as are the somewhat crumbling and overgrown remains of the two paved circles used in 1960 and again in 1964 for the team race and speed events. I bet that it would be impossible for any true enthusiast to stand in front of that old building and not conjure up the sound of a model engine working at full stretch, or catch a faint scent of burning ether or nitro on the breeze .................. ___________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2023

|

| |

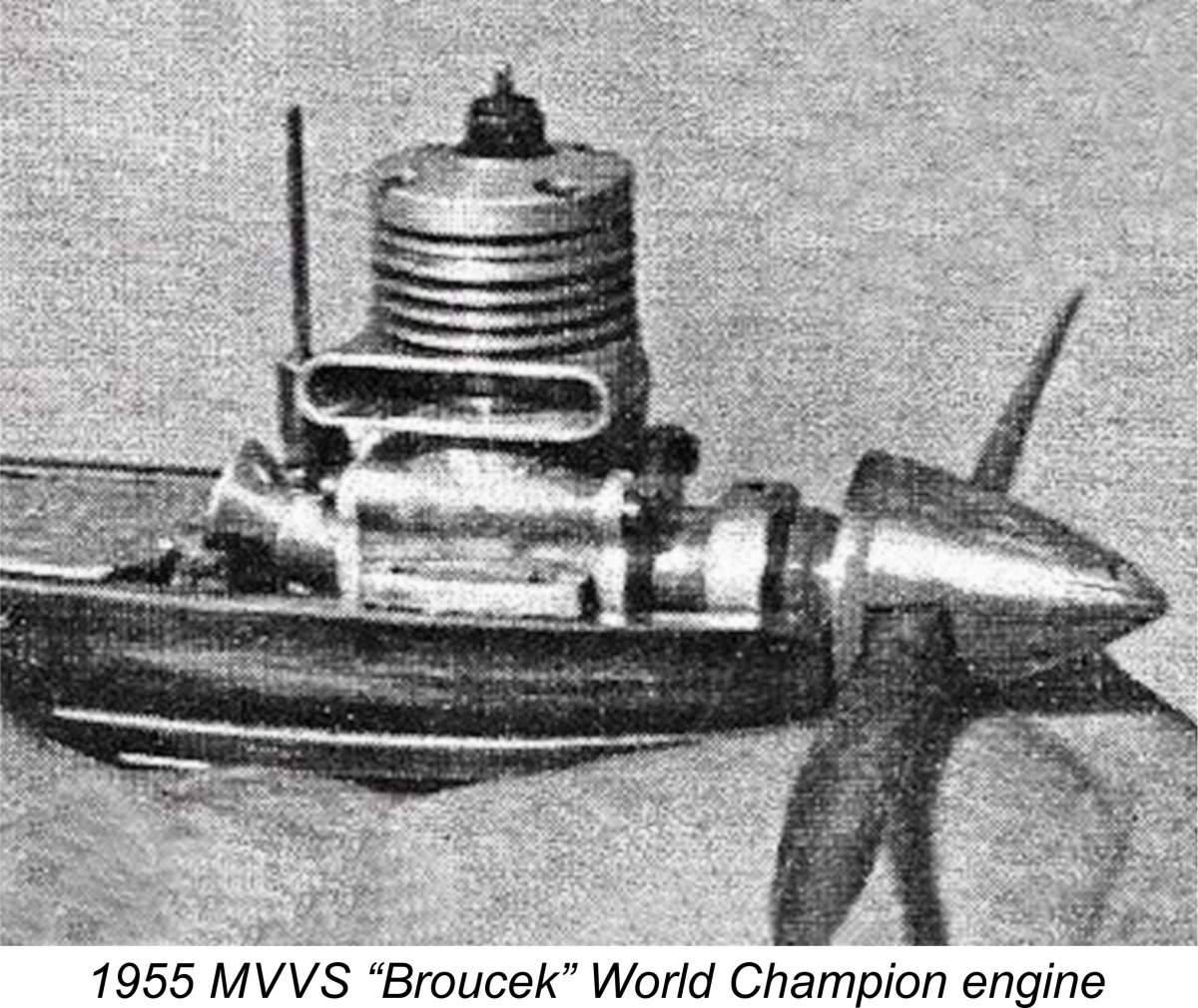

Unfortunately for Garofali, that 1955 competition coincided with the appearance of the first State-sponsored competition “specials” from the other side of the Iron Curtain. That first World Championship flown using 2.5 cc powerplants was won by the Czech competitor Josef Sladký using the SK-25 “Broucek” (Poppet) prototype motor which had been designed and constructed by himself and his compatriot Luboš Kočí at the MVVS workshops in Brno. Garofali had to console himself with second place to go along with the team trophy.

Unfortunately for Garofali, that 1955 competition coincided with the appearance of the first State-sponsored competition “specials” from the other side of the Iron Curtain. That first World Championship flown using 2.5 cc powerplants was won by the Czech competitor Josef Sladký using the SK-25 “Broucek” (Poppet) prototype motor which had been designed and constructed by himself and his compatriot Luboš Kočí at the MVVS workshops in Brno. Garofali had to console himself with second place to go along with the team trophy.

The 1960 World Speed Championship event was held on September 8

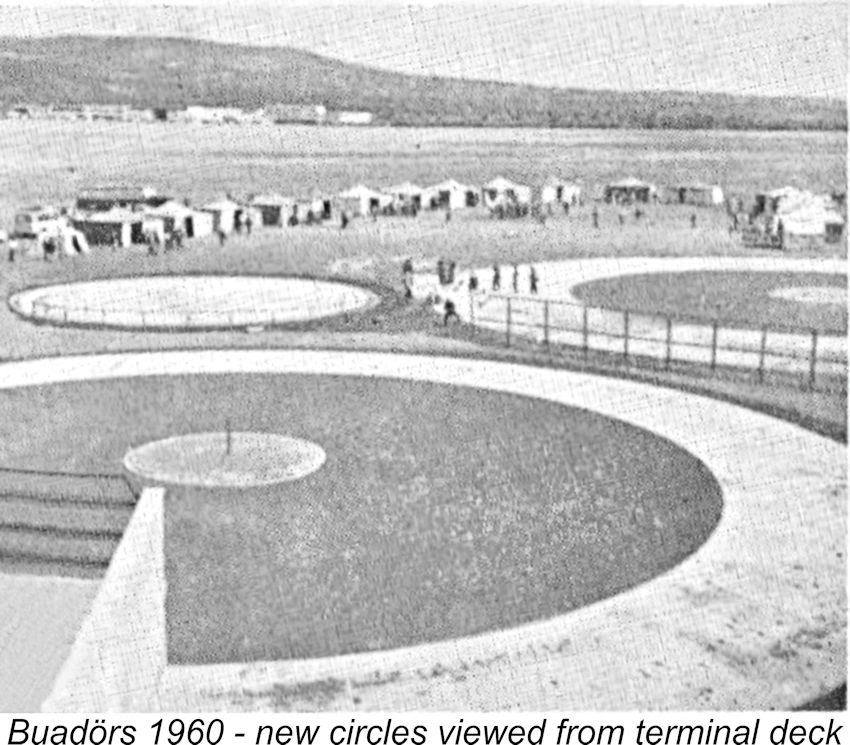

The 1960 World Speed Championship event was held on September 8 Although no longer used for its original purpose, the former main terminal building of 1937 had been given over to the use of model aircraft organizations who had access to the field. For the 1960 event, the building had been re-decorated and arranged to serve as a dining room for the 250-odd individuals in attendance. Two new superbly-paved team race/speed circles had been laid out adjacent to the terminal building complete with safety netting, electrically-controlled team race lap clocks operated by the lap counters, a timekeepers' box, etc. The smaller circle visible in the accompanying view is a tether car track. There was ample space adjacent to the circles to accommodate the tent "pit workshops"

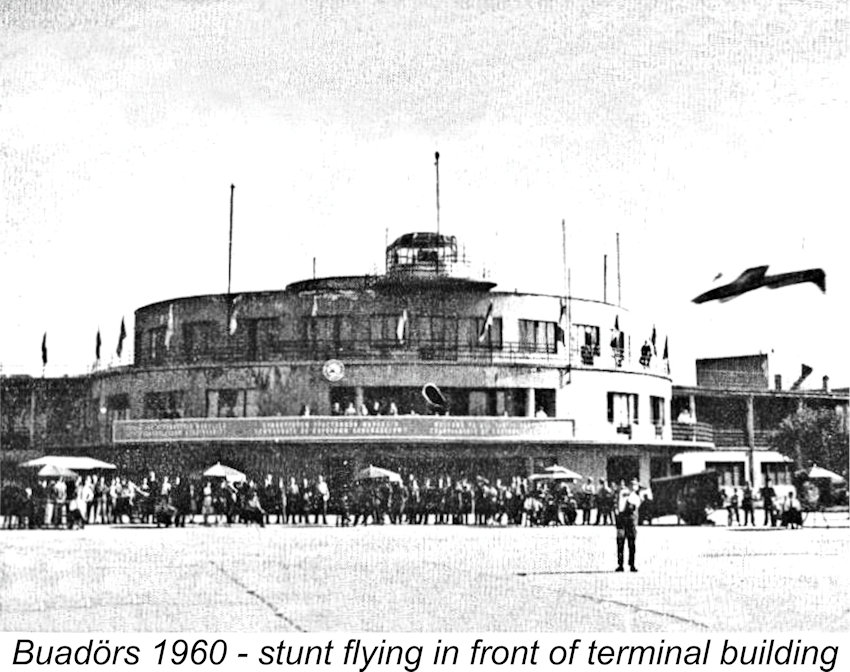

Although no longer used for its original purpose, the former main terminal building of 1937 had been given over to the use of model aircraft organizations who had access to the field. For the 1960 event, the building had been re-decorated and arranged to serve as a dining room for the 250-odd individuals in attendance. Two new superbly-paved team race/speed circles had been laid out adjacent to the terminal building complete with safety netting, electrically-controlled team race lap clocks operated by the lap counters, a timekeepers' box, etc. The smaller circle visible in the accompanying view is a tether car track. There was ample space adjacent to the circles to accommodate the tent "pit workshops"  of the competitors, as seen in the image. The concrete apron formerly used to park visiting airliners in front of the terminal was available throughout the meeting for the use of the Stunt competitors. Nothing was lacking for a great contest!

of the competitors, as seen in the image. The concrete apron formerly used to park visiting airliners in front of the terminal was available throughout the meeting for the use of the Stunt competitors. Nothing was lacking for a great contest! There were 28 entries in the Speed competition, each of whom was entitled to three attempts. A highlight was the long-anticipated arrival on the World Championship scene of the legendary American speed fliers represented by Bill Wisniewski, Jim Nightingale and Bob Lauderdale. They were equipped with Wisniewski’s remarkable 2.5 cc specials which were soon to be developed into the K&B 15R series of commercial 2.5 cc racing engines. After their absence the previous year, the Czechs returned in force with their improved

There were 28 entries in the Speed competition, each of whom was entitled to three attempts. A highlight was the long-anticipated arrival on the World Championship scene of the legendary American speed fliers represented by Bill Wisniewski, Jim Nightingale and Bob Lauderdale. They were equipped with Wisniewski’s remarkable 2.5 cc specials which were soon to be developed into the K&B 15R series of commercial 2.5 cc racing engines. After their absence the previous year, the Czechs returned in force with their improved  Jim Nightingale of the USA was right behind Wisniewski with a first-round monoline speed of 227 km/hr (141.05 mph), while Bob Lauderdale recorded a very competitive figure of 222 km/hr (138 mph), again using monoline. Interestingly enough, for this round Lauderdale used a modified example of the brand new Super Tigre G.20/15V “Jubilee” motor which he had somehow obtained. Well-tweaked prototypes of this motor were of course used by all of the Italian entrants - the example used by Ugo Rossi was self-tuned and displayed the Rossi name on its front bearing housing.

Jim Nightingale of the USA was right behind Wisniewski with a first-round monoline speed of 227 km/hr (141.05 mph), while Bob Lauderdale recorded a very competitive figure of 222 km/hr (138 mph), again using monoline. Interestingly enough, for this round Lauderdale used a modified example of the brand new Super Tigre G.20/15V “Jubilee” motor which he had somehow obtained. Well-tweaked prototypes of this motor were of course used by all of the Italian entrants - the example used by Ugo Rossi was self-tuned and displayed the Rossi name on its front bearing housing.

The defensive argument made by the Italians was that whipping was not banned (which was unfortunately true at this stage). Maybe, but that wasn’t the point - we're not talking about whipping here! Rossi was so far ahead of his model that he was actually shortening his flight circle radius, thus clearly meriting instant disqualification since his model didn't cover the required distance.

The defensive argument made by the Italians was that whipping was not banned (which was unfortunately true at this stage). Maybe, but that wasn’t the point - we're not talking about whipping here! Rossi was so far ahead of his model that he was actually shortening his flight circle radius, thus clearly meriting instant disqualification since his model didn't cover the required distance.

(and a very creditable one) that the Super Tigres could produce on two lines without a “helping hand” (or in Rossi’s case a line-shortening shoulder).

(and a very creditable one) that the Super Tigres could produce on two lines without a “helping hand” (or in Rossi’s case a line-shortening shoulder). The Hungarian organizers had prepared special trophies of their own to be presented to the speed and team race winners. They showed their opinion of the official results very clearly by presenting the speed trophy to the Americans, "contrary to announcement" according to the "Aeromodeller" report. Perhaps diplomatically, the trophy was accepted by the acting manager of the American team, Phil Edwards, rather than by Bill Wisniewski!

The Hungarian organizers had prepared special trophies of their own to be presented to the speed and team race winners. They showed their opinion of the official results very clearly by presenting the speed trophy to the Americans, "contrary to announcement" according to the "Aeromodeller" report. Perhaps diplomatically, the trophy was accepted by the acting manager of the American team, Phil Edwards, rather than by Bill Wisniewski!

Setting all controversy aside, it would seem that Jaures Garofali had indeed made great strides during the development of the modified Super Tigre G.20/15V used by the Rossi brothers. A production version of this engine appeared more or less concurrently in the shape of the

Setting all controversy aside, it would seem that Jaures Garofali had indeed made great strides during the development of the modified Super Tigre G.20/15V used by the Rossi brothers. A production version of this engine appeared more or less concurrently in the shape of the  Subsequent to the original publication of this article, my valued friend and colleague Johnny Shannon of Texas was kind enough to contact me with some fascinating new information relating to this incident. I’ve always wondered why Bill Wisniewski didn’t protest the manifestly unjust result given his very clear grounds for doing so, and was keen to seek insights into this aspect of the matter.

Subsequent to the original publication of this article, my valued friend and colleague Johnny Shannon of Texas was kind enough to contact me with some fascinating new information relating to this incident. I’ve always wondered why Bill Wisniewski didn’t protest the manifestly unjust result given his very clear grounds for doing so, and was keen to seek insights into this aspect of the matter. the meeting which retained their baffle pistons. It took a certain largeness of mind to recognize and accept such a view of one's competitor.

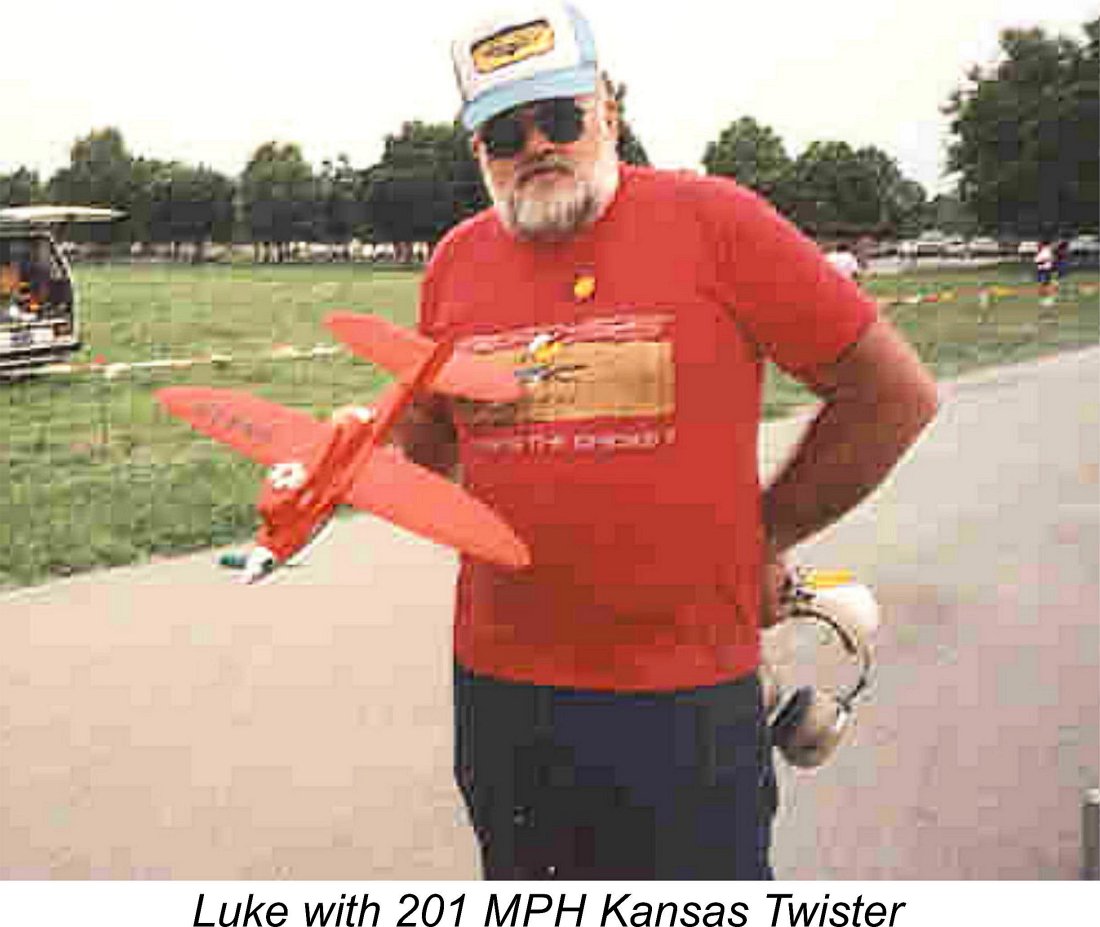

the meeting which retained their baffle pistons. It took a certain largeness of mind to recognize and accept such a view of one's competitor.  Following the initial publication of this article, I also had a very interesting exchange with my valued friend Luke Roy of

Following the initial publication of this article, I also had a very interesting exchange with my valued friend Luke Roy of  Of course, the really great ones don't allow incidents of this nature to dampen their enthusiasm or impede their progress, and none were greater than Bill Wisniewski! Taking the view that "if you can't join 'em, beat 'em!", Bill’s answer to the 1960 World Championship fiasco was to get right back down to work. In Luke's opinion, K&B's failure to reach an agreement with Super Tigre was directly responsible for goading Bill into developing his own alternative porting arrangement which allowed the elimination of the piston baffle. If Super Tigre wouldn't share their technology, Bill would develop his own!

Of course, the really great ones don't allow incidents of this nature to dampen their enthusiasm or impede their progress, and none were greater than Bill Wisniewski! Taking the view that "if you can't join 'em, beat 'em!", Bill’s answer to the 1960 World Championship fiasco was to get right back down to work. In Luke's opinion, K&B's failure to reach an agreement with Super Tigre was directly responsible for goading Bill into developing his own alternative porting arrangement which allowed the elimination of the piston baffle. If Super Tigre wouldn't share their technology, Bill would develop his own!

Bill repeated this feat in 1966 at Swinderby in England using his TWA powerplant with which he won the title once again while unleashing the technology of tuned pipes upon the modelling world and unselfishly sharing the new technology in doing so - another stark contrast to Garofali's attitude. For a spectator's description of the impact which Bill's performance at this meeting had on the observers, check out

Bill repeated this feat in 1966 at Swinderby in England using his TWA powerplant with which he won the title once again while unleashing the technology of tuned pipes upon the modelling world and unselfishly sharing the new technology in doing so - another stark contrast to Garofali's attitude. For a spectator's description of the impact which Bill's performance at this meeting had on the observers, check out