|

|

The History of MOKI Regular readers of this website may recall a number of my articles on classic British and European racing engines, including the Rowell engines from Scotland, the ETA, Nordec and Ten-Sixty-Six motors from England and several European marques such as the Czech MVVS and Vltavan models, the Italian Super Tigre racing designs, the Danish Mikro 5 cc model, the Hungarian Alag and VT racers and the French Allouchéry 5 cc design. This article will focus on another famous name in the history of model racing engines - the MOKI marque from Hungary.

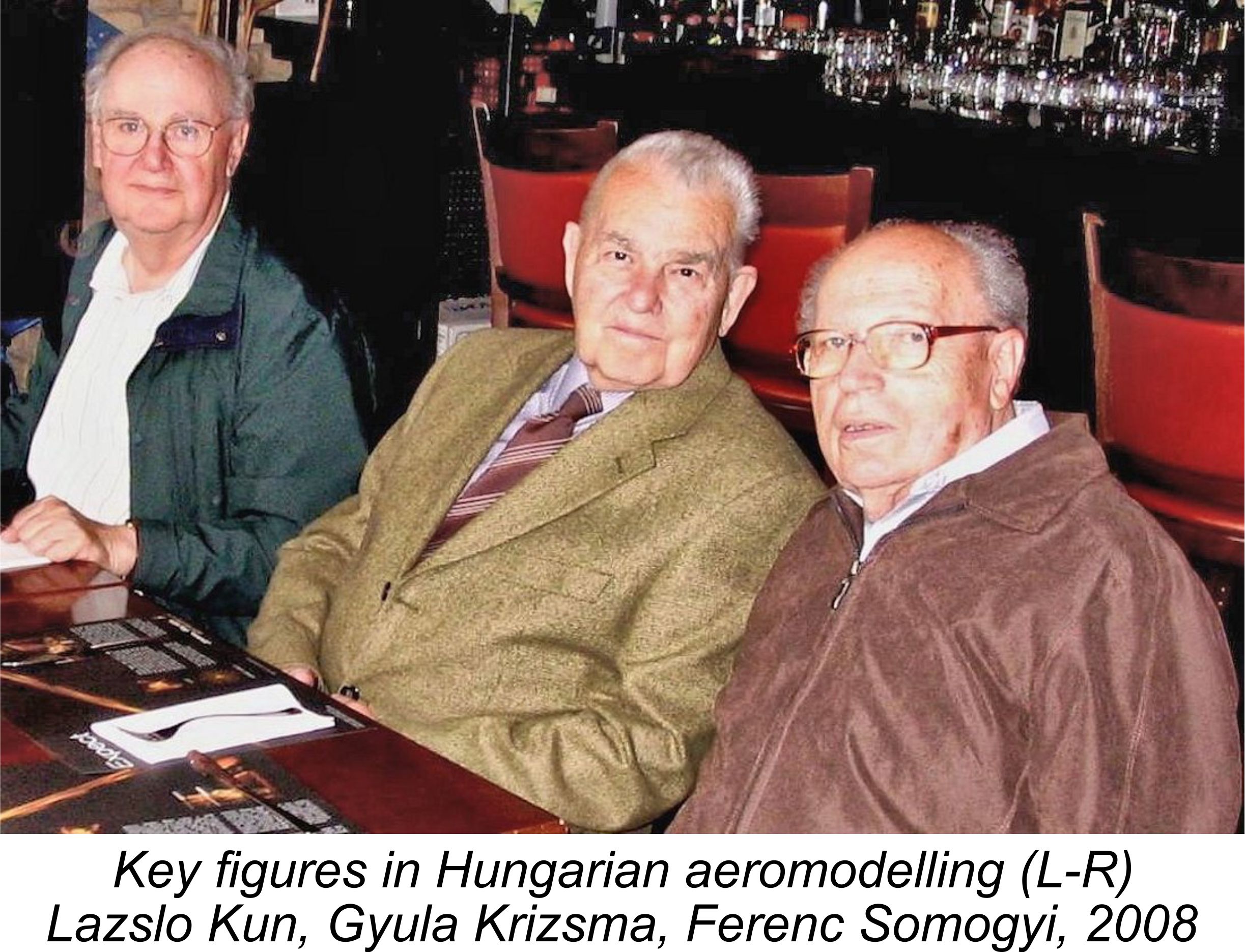

We saw in that article that the MVVS concern was established by the Communist government then in power as a political initiative for the express purpose of providing competitive racing engines to the very small number of competitors who were judged to be sufficiently skilled to get the best out of them, thus enhancing the prestige of the Communist state. At the outset, there was no thought of engaging in the commercial production of model engines, although that did in fact develop later as the only viable means of funding the ongoing activities of the MVVS workshops on a sustainable basis. The telling of the MVVS story inevitably required me to make reference to the slightly later parallel initiative on the part of the Hungarian government under the title MOKI. I noted that this venture was extremely successful, to the point that the Hungarian team was able to use their MOKI-powered models to wrest the World Control-Line Speed Championship away from the previously all-conquering Czech MVVS squad in 1958 as well as repeating this success in several later years. Clearly, a venture having this kind of impact upon the international modelling scene deserves our full attention from a historical standpoint! However, I knew that I was woefully under-qualified to write this story – I would need a lucky break. On the principle that all things come to him who waits, I waited ……. and waited! Eventually, I was fortunate enough to hear from a Hungarian resident and former keen modeller, Mr. Ferenc Somogyi, who kindly wrote to me to correct a number of errors that had crept into my separate article on the Hungarian Alag and V.T. engines. The necessary corrections had to be incorporated into a comprehensive re-write of the Alag article which appears elsewhere on this website. Returning to the matter at hand, it turned out that Somi (as he liked to be called by his family and friends) Somi was actively involved in the Hungarian model movement during the entire period in which MOKI rose to prominence, thus having intimate first-hand knowledge of both the designs and personalities involved. In his professional career, Somi was the chief of the diesel engine department at the Ganz MÁVAG Wagon and Locomotive Factory. Accordingly, his primary focus following his graduation from the Budapest University of Technology and Economics in 1953 was the development of railway diesel engines. Some idea of the passage of time may be gained from the fact that in July of 2013 Somi received his Diamond Diploma from the University, marking 60 years since his graduation! It's sad to have to record Somi's passing on July 1st, 2020 at the grand old age of 91 years.

During the early 1950's,

Somi soon commenced his career as a team manager by managing the Hungarian team which competed in the 2nd annual International People's Democratic States contest at Vrchlabi, Czechoslovakia in September 1955. The attached photograph shows In later years, Somi served as the Hungarian Speed Team Manager at the 1980 World Championships at Czestohova, Poland; the 1982 World Championships at Oxelösund, Sweden; the 1983 European Championships at Utrecht, Holland; the 1984 World Championships at Chicopee, USA; the 1985 European Championships at Manchester, England; and the 1987 World Championships at Nyköping, Sweden. MOKI engines were of course used by the Hungarian team at all of these events. Talk about well-qualified!! This of course is the kind of contact that model engine historians like me dream about - there could be few individuals in a better position to comment upon our present It took a while and a great deal of effort on his part, but eventually the text (in imperfect but completely intelligible English) arrived. I went through it with the Editor’s pencil to re-order the material a little as well as straighten out some of the expressions used, but left the facts well alone! Somi was kind enough to read my edited version of his article and offer a few very helpful suggestions. The text which follows is the result of this collaboration. As if this wasn't enough, Somi also provided images of most of the MOKI engines to which he made reference in the text. It’s really hard to see how he could have done more to help the rest of us gain a complete understanding of the work of MOKI and its talented staff. I am uncertain regarding the identity of the photographers in the cases of most of these images, hence leaving them unattributed. I apologize to anyone who recognizes their own photograhic efforts in this article. However, it's all in the name of knowledge, and no-one's making any money here! Additional help came from a German reader, Dr. Peter Rathke, who has an amazing collection of classic and later MOKI engines which he obtained from an older ex-employee of the MOKI Institution. Upon learning that an article about MOKI was scheduled to appear on this site, Peter very graciously supplied a number of additional images to complement those already provided by Somi. Such splendid co-operation and support from readers goes a long way towards making all this effort worthwhile - thanks, Peter! To sum up …..... what follows is the history of the MOKI venture in words and pictures, told by one who was “there”. I claim no credit whatsoever for this article – I couldn't have written a word of it myself! It is all Somi’s work, with just a little editing on my part (at his request, I might add!) Our indebtedness to Somi for sharing this information with us cannot be overstated. All I can say is - thank you, my friend!! You are missed ........ Background Before turning the pen over to Somi, I feel that in keeping with the other articles on this site a little background is necessary to set the stage. I will therefore do my best to set the scene, after which Somi will take over. Sport flying using both gliders and powered aircraft had apparently been quite popular in Hungary prior to WW2, with a number of very active aero clubs. At that time, Hungary was very much allied with the Axis powers in Europe, relying increasingly upon trade with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy to pull itself out of the Great Depression of the 1930’s. Although reluctant to actually involve itself in all-out war, the country was inexorably drawn into WW2, being directly but perhaps somewhat reluctantly involved on the Axis side in the 1941 invasions of both Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union.

Subsequent negotiations between the Allied powers led to the February 1st, 1946 establishment of the “Second Republic of Hungary”, which was governed by the Hungarian Communist Party under close Russian supervision. However, the imposition of this change in government did not proceed smoothly - it took until August 1949 for the country to finally become stabilized as the Hungarian People’s Republic (Magyar Népköztársaság), a Communist state which was administered by the Socialist Workers’ Party, still under dominating Soviet influence. The Hungarian People’s Republic was destined to survive until October 23rd, 1989, at which point the collapse of the Soviet Union coincided with the completion of an orderly transition to a Western-style democracy designated the Republic of Hungary. Somi refers to this change in regimes at several points in his narrative. The events of the early post-war period had of course left the country’s sport-flying resources in a shambles. Some measure of the importance attached to this activity may be gauged from the fact that steps were taken as rapidly as possible after the war to start rebuilding the sport-flying movement in Hungary. The role of this activity in producing potential military fliers doubtless influenced this decision on the part of the country’s Communist leadership. Until June 1947, the Control Commission of the Allied powers imposed a complete ban on all sport-flying in Hungary. However, immediately upon the lifting of that ban, the Hungarians moved vigorously to re-establish sport-flying on an organized basis. In early 1948 a new organization called Országos Magyar Repülö Egyesület (OMRE - National Hungarian Flying Association) was created to administer all sport-flying activity in Hungary. All existing aero clubs along with all their assets were incorporated into this new organization, and all sport airfields were managed and financed by OMRE in addition. A number of aircraft suitable for sport-flying, both gliders and powered designs, had survived the ravages of war, but repairs and upgrades to these were urgently needed. In addition, a number of partially-constructed aircraft were awaiting completion. On top of this, new aircraft were urgently required to meet the growing needs of the revitalized movement.

In addition to the restoration, maintenance and upgrading of existing aircraft, new designs were also required. To meet this need, a central design office was also established at Budaörs to develop such designs along with all the necessary documentation, restoration and repair programs required. The success of OMRE in meeting its initial goals soon drew government attention to its further potential. A decision was taken that OMRE's activities were worthy of a higher level of Government support. This led to the assets and mandate of OMRE being taken over by a new group called the Magyar Repülö Szövetség (MRSz - Hungarian Aeronautical Association). Part of the MRSz plant at Budaörs, which was then engaged in building new aircraft, was moved to Mátyásföld airport in 1951.

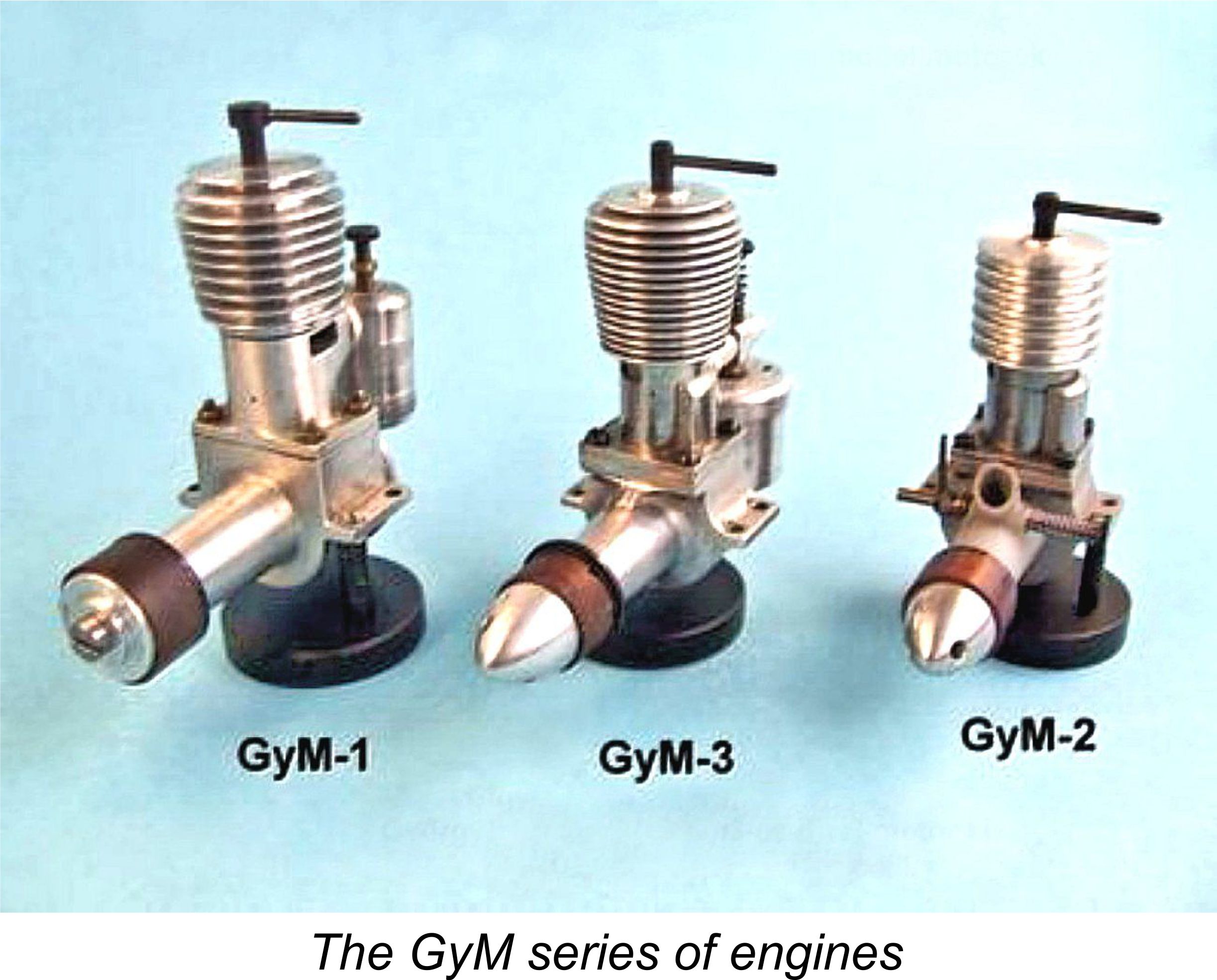

In 1954, military considerations led to the full-sized aircraft side of MRSz being absorbed into the MÖHOSz (Hungarian Voluntary National Defence Association, later to be redesignated the Hungarian Civil Defence Association (MHSz)). At the same time, portions of the Dunakeszi operation were taken over by the Kohó és Gépipari Miniszterium (Ministry of Metallurgical and Mechanical Industry). This latter take-over occurred in March 1955, and the resulting government-run technical facility was designated the Alagi Központi Kisérleti Üzem (AKKÜ - Alag Central Experimental Plant). This was very quickly to become the source of the Alag range of model engines, as we shall see. While all this had been going on in connection with the full-scale sport flying movement in Hungary, participation in model flying activities had grown by leaps and bounds during the early post-war period. This situation naturally led a few individuals to attempt the production of commercial model engine designs in Hungary. However, their efforts fell well short of meeting the full demands of the situation. Even so, those efforts deserve our respectful notice. Among these early manufacturers, we may mention the GyM series of 5 cc diesels designed by Györgyfalvy Dezső (d. 2010) and made in very small numbers in 1950-51 by a single individual whose name is now lost, working alone in a tiny workshop with minimal machine tooling. Another early Hungarian model engine manufacturing venture was the Szegedi Vas és Fémipari Szövetkezet (Szeged Iron and Metallurgical Co-operative), which began to manufacture model engines in 1953 under the direction of the well-known Hungarian free-flight modeler László Hódi. Early products included the 2.3 cc HV-1 sideport diesel and the Meteor 2.5 cc diesel. In 1954, the co-operative initiated production of the Darú 2.3 cc sideport diesel However, these relatively small-scale manufacturing efforts fell short in two major respects. Firstly, production figures were insufficient to meet demand. This had the unhappy effect of limiting the number of individuals who could participate in power modelling and thus gain the skills necessary to potentially represent Hungary at the highest levels of international competition. Secondly, the products of these ventures were very suitable for sport flying but lacked the performance necessary for successful participation in International competition. It soon became clear that there was a need to address both of these issues. To deal with the first issue would require the initiation of the mass production of model engines on a far larger scale. To address this need, the previously-mentioned AKKÜ facilities at Dunakeszi which had been established in March 1955 were immediately turned over to the design and large-scale manufacture of a range of high-quality sport motors under the Alag label. László Kun was appointed as the chief of the model engine department at AKKÜ. Most interestingly, Kun’s assistant was none other than Gyula Krizsma, whom we shall meet again in this article.

This development doubtless had another motivation apart from encouraging a higher level of participation in power modelling. At the time in question, hard currency was in very short supply in Hungary. For this reason, the importation of specialized goods such as model engines from Western countries was impossible. This situation made it inevitable that efforts would be made to initiate the domestic production of Hungarian model engines, both for the use of Hungarian modelers and for export to the West to gain some much-needed hard currency. In order to pursue the latter goal, a trading organization known as ARTEX was established early on for the express purpose of developing export markets for the Alag and other However, these initiatives did little to alleviate the need for leading Hungarian modelers to be supplied with domestically-constructed engines delivering the standards of performance required to bring success at the highest levels of International competition. It was to meet this need, against the background of post-war political and social turmoil leading up to the bloody revolution of 1956, that the MOKI initiative had its beginnings. The long-term success of the MOKI venture may be gauged by the fact that since the inception of the marque, Hungarian modelers have used the resulting engines to amass some two hundred European and World Championship titles in various categories, together with a long list of world records. Many of Hungary's most successful modelers have participated in international competition while at the same time working for MOKI. Perhaps the most famous example is Gyula Krizsma, the 1962 World Control-Line Speed Champion, whom we shall meet again in Somi’s telling of the MOKI story. Speaking of which, let’s now turn the pen over to Somi for a unique insight into the evolution of MOKI! The MOKI Story By Ferenc Somogyi

Apart from these sources, I made reference to the various MOKI catalogues at my disposal. The rest of the information came from the personal knowledge of these matters which I gained through my 60 years of involvement and work in the sport of aeromodelling in Hungary. During the period immediately following the end of WW2, the sport of aeromodelling quickly gained ground in Hungary. The post-war head of the Hungarian Modeling Department was György Benedek, who was internationally known for the “B” aerofoil design for free-flight models. However, Mr. Benedek had to leave when the Communists finally established firm control of the country in 1949, and his expert leadership was replaced by uninformed Communist political appointees. This did nothing to help the Hungarian modelling movement to improve its standards. After the revolution of 1956, the situation changed very much for the better. Rezső Beck (1928 - 2002) became the chief of what had now become the Hungarian Association of Modelers. Mr. Beck was a well-known ealy post-war competitor, subsequently becoming a successful control-line speed flier in the 1950’s. Thanks to his professional knowledge and political influence, he was well able to guide the development of Hungarian aeromodelling, also serving as the Hungarian representative on the FAI Aeromodelling Commission (CIAM). As a control-line speed flier himself, Rezső Beck clearly understood the urgent need for the development of competitive Hungarian competition engines in addition to radio control equipment. Due to the previously-mentioned chronic lack of convertible currency at the time, it was not possible to import either engines or radio control equipment, which would thus have to be developed and manufactured within Hungary itself. It was at Rezső Beck’s suggestion based on this recognition that MOKI (Modell Kisérleti Intézet or Model Experimental Institution) was founded on the 1st of June, 1957. The Institution was overseen by the Hungarian Civil Defence Association (MHSz), which was to retain this role until the change of regimes in late 1989. The Institution was located in a building at Budaörs airport, former home of the OMRE organization to which Adrian made reference earlier. György Benedek was brought back to serve as the head of the Institution, giving it instant credibility. The workshop was initially very small, with only 5 or 6 trained employees using traditional machine tools. The primary task assigned to this Institution was to support aeromodelling in Hungary by designing and producing engines which would be competitive at the International level. A related goal was to enhance the availability of radio control systems and accessories to Hungarian modelers interested in this fast-growing branch of the sport. However, the most immediate need was for competitive racing engines, since the lack of these prevented the successful participation of Hungarian competitors in International competitions. Like the parallel MVVS organization in Czechoslovakia (as it was then), there was no expectation at the outset that MOKI would engage in large-scale commercial production. The goal was to design and produce only the minimal number of hand-built engines needed to supply those few Hungarian modelers judged to be sufficiently skilled to use them successfully in competition. To assist the reader in following the evolution of the MOKI engines, it may be useful at this point to review the identification system applied by MOKI to the various models. Each model was identified by one or two letters signifying its intended purpose, followed by a number to indicate that particular design’s position in the design sequence. The letters used were as follows: S - speed engines TR - team race engines M - stunt engines. D - diesel engines A - car engines C - combat engines P - pylon racing engines RC - engine with throttle carburetors for radio control V - water cooled engines G – spark ignition engines O - engines for miscellaneous applications In order to avoid confusion, it's important to note that during the entire Communist era the numbers asociated with these letters relate to the particular model and not to its displacement. Numerical model identification only became related to the engines' displacements much later in 1990 after the change of regimes. Some of the later S and TR engines also feature a letter A or T after the main identification. These extra letters signify the involvement of László Azor or Imre Tóth as collaborators with Gyula Krizsma in the design of the engines in question. I will discuss the engines generally in the chronological order in which they appeared, including the date(s) of their manufacture and the approximate number of examples made. There are photos of most of the engines mentioned, although many different versions in a given category look almost identical externally.

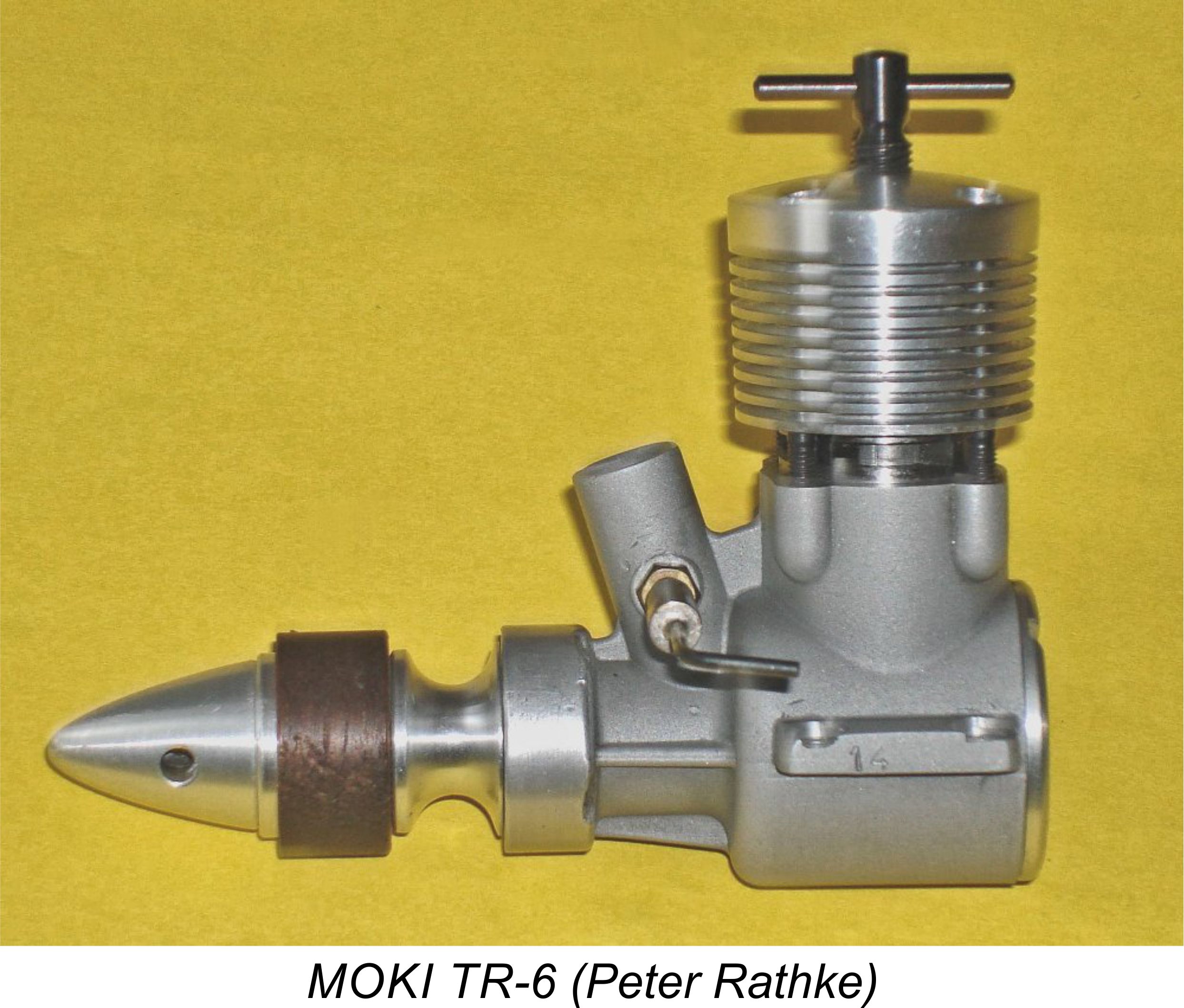

Following these achievements, György Benedek worked together with László Azor on several different prototypes (TR-2 and TR-3), eventually culminating in the 1959 In 1960, MOKI continued its efforts on behalf of the more serious Hungarian team race competitors by producing 150 examples of the MOKI TR-6 team race diesel, which were followed by a further 100 examples in 1961. Clearly the original goal of confining the workshop to the production of very small numbers of “tool-room specials” All of these engines in the TR series up to this point were 2.5 cc diesel models utilizing radial cylinder porting along with crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction. Apart from internal modifications, the various models could be recognized by their differing front housing and backplate configurations as well as by their venturi and carburetion arrangements. Reader Patrick Hardy has provided incontrovertible evidence to the effect that the later examples of the TR-6 were equipped with removable intake venturis, but apart from that the design appears to have remained unchanged. The TR-6 was the final MOKI engine with which György Benedek was associated. After getting the MOKI venture off to a very positive start, Benedek had to leave MOKI in 1960 due to After the departure of György Benedek, the leadership of MOKI was entrusted to Gyula Krizsma, who had gained previous experience with model engine design and manufacture through his involvement with the Alag and Krizsma Rekord engines. Krizsma was also an experienced and very successful control line speed flier. This background qualified him perfectly to take over as leader of the MOKI Institution. During the three decades over which he worked there, he was responsible for the design and production of some 50 distinct engine models! The control-line speed category had been somewhat neglected following the 1958 World Championship success. The 1959 and 1960 World Championship titles had been won by Ugo Rossi using Super Tigre power. To remedy this situation, Gyula Krizsma began his work for MOKI by designing the MOKI S-2 speed engine. In embarking upon this design, Krizsma established the goal of creating a relatively simple yet competitive engine which might do much to popularize speed flying.

This engine may have been simple in terms of its basic construction, but this did not stand in the way of a championship level of performance! Imre Tóth was once again victorious at the 1961 World Control-line Speed Championships using a monoline model powered by a MOKI S-2 powerplant. This was the first year in which the FAI required the use of straight methanol/castor fuel with no nitromethane or other additives. It was at around this point in time that MOKI management took the inevitable decision that the only way to finance the continued activities of the Institution was to focus upon the field of commercial model engine production. A similar decision had already been taken by MVVS in Czechoslovakia, and now MOKI followed suit. In keeping with this new policy, some 400 examples of the MOKI S-2 were made in 1961 for distribution to customers.

In the same year of 1961, the MOKI D-1 made its appearance. This model was basically a diesel version of the MOKI S-2. During this period, MOKI had made very small numbers of several stunt glow-plug motors, the 6 cc MOKI M-1 and the 6.28 cc MOKI M-2. Neither of these models came up to expectations in terms of performance, but by 1961 Krizsma had settled upon a design which he felt would fully meet the needs of control line stunt fliers. This new design, the MOKI M-3, was introduced in 1961.

(Editor’s note – one of these engines too found its way into the hands of “Aeromodeller” engine tester Ron Warring, whose report was published in the March 1963 issue of the magazine. Once again, Warring was most complimentary regarding the quality of the engine’s construction. He reported an output of 0.53 BHP @ 14,000 rpm, which was well in line with measured performance figures for other stunt engines of similar displacement, also being very consistent with the factory claim of 0.55 BHP @ 14,000 rpm – A.D.) I should mention at this point that in 1968 MOKI produced 200 examples of a revised version of this engine having an increased displacement of 7 cc but otherwise very similar. This later model was designated the MOKI M-4. Unfortunately, I was not able to find a good image for this engine. However, it looked very similar indeed to the M-3.

Initially, only 20 examples of this model were produced, one of which was used by Gyula Krizsma in person to win the 1962 World Speed Championship. Following this success, a further 200 examples were manufactured. Imre Tóth later repeated this success in 1965 by becoming the European Speed Champion using the same engine. In both these years, the Hungarians also took the team prize yet again.

Also in 1963, 20 examples of a 1 cc diesel called the MOKI D-3 were made for experimental purposes. This very simple engine featured a plain bearing with FRV induction, along with a cylinder design having twin exhaust ports at the sides. The finned cylinder head and the back plate were both threaded into the crankcase. For unknown reasons, this model never reached series production, and there is no surviving useable photograph of it as far as I am aware.

(Editor’s note - once again, Ron Warring of “Aeromodeller” magazine somehow managed to get his hands on an example of the MOKI S-4. His test report on the engine appeared in the May 1964 issue of the magazine. As usual with MOKI products, both the engineering design and the workmanship embodied in the engine came in for the highest praise. Warring reported an output of 0.60 BHP @ 17,800 rpm on straight FAI fuel, while the use of a fuel containing 50% nitromethane improved this performance to 0.75 BHP @ 18,000 rpm. Although not quite up to the factory claims of 0.67 BHP @ 20,000 rpm on straight fuel and 0.885 BHP @ 19,200 rpm on 50% nitromethane, these were still very impressive figures by the standards of the day – A.D.)

In 1966 the American competitors Bill Wisniewski and Roger Theobald appeared at the World Control-Line Speed Championships (held that year in England) with engines which utilized tuned exhaust pipes in combination with well-developed Schnüerle porting systems. This innovation raised power outputs to the point at which the American team was easily able to secure the first, second and third places in the competition, thus also winning the team prize.

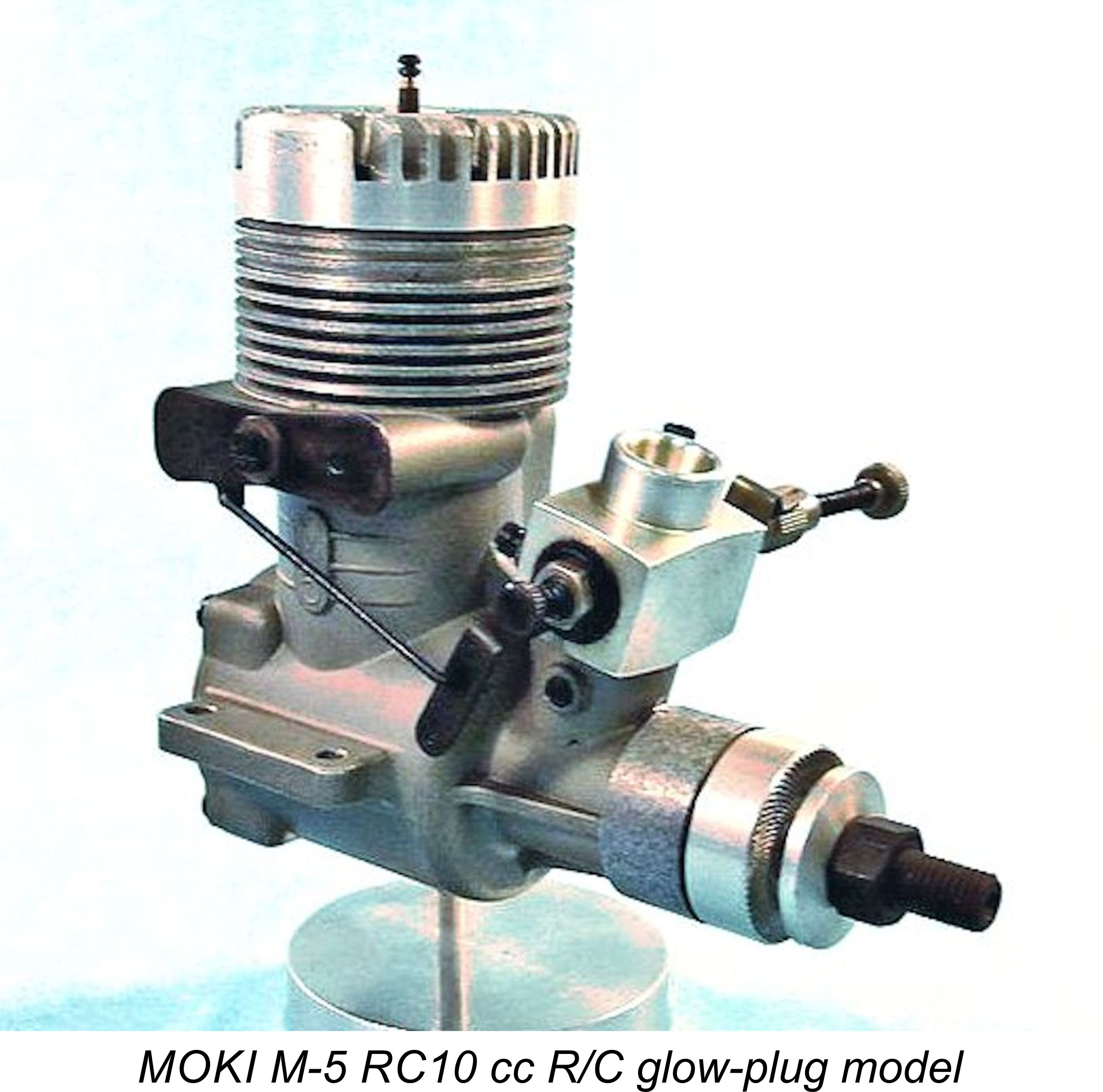

A very few examples of a diesel version of this engine were produced in 1967 under the name MOKI S-6 TD. Apart from the different cylinder head, this version was identical to the glow-plug model. Only ten examples were produced - a throwback to the early days of MOKI. While Krizsma and Tóth were busy developing the S-6 T and S-6 TD, László Azor was hard at work designing the MOKI TR-7 A team race diesel, of which 200 examples were made A major change came in 1970 with the introduction of the first MOKI engine which was specifically targeted at the export market. This was MOKI’s first purpose-built R/C engine, the 10 cc MOKI M-5 RC glow-plug unit. This engine was exported on the basis of an exchange of goods rather than cash to get The M-5 RC featured FRV induction along with cross-flow loop scavenging. The main bearing housing was cast integrally with the crankcase, while the shaft was supported by two ball races. A steel cylinder liner was used along with a twin-ringed aluminium alloy deflector piston. The earlier examples like that illustrated featured an exhaust baffle which was connected to the carburetor control arm.

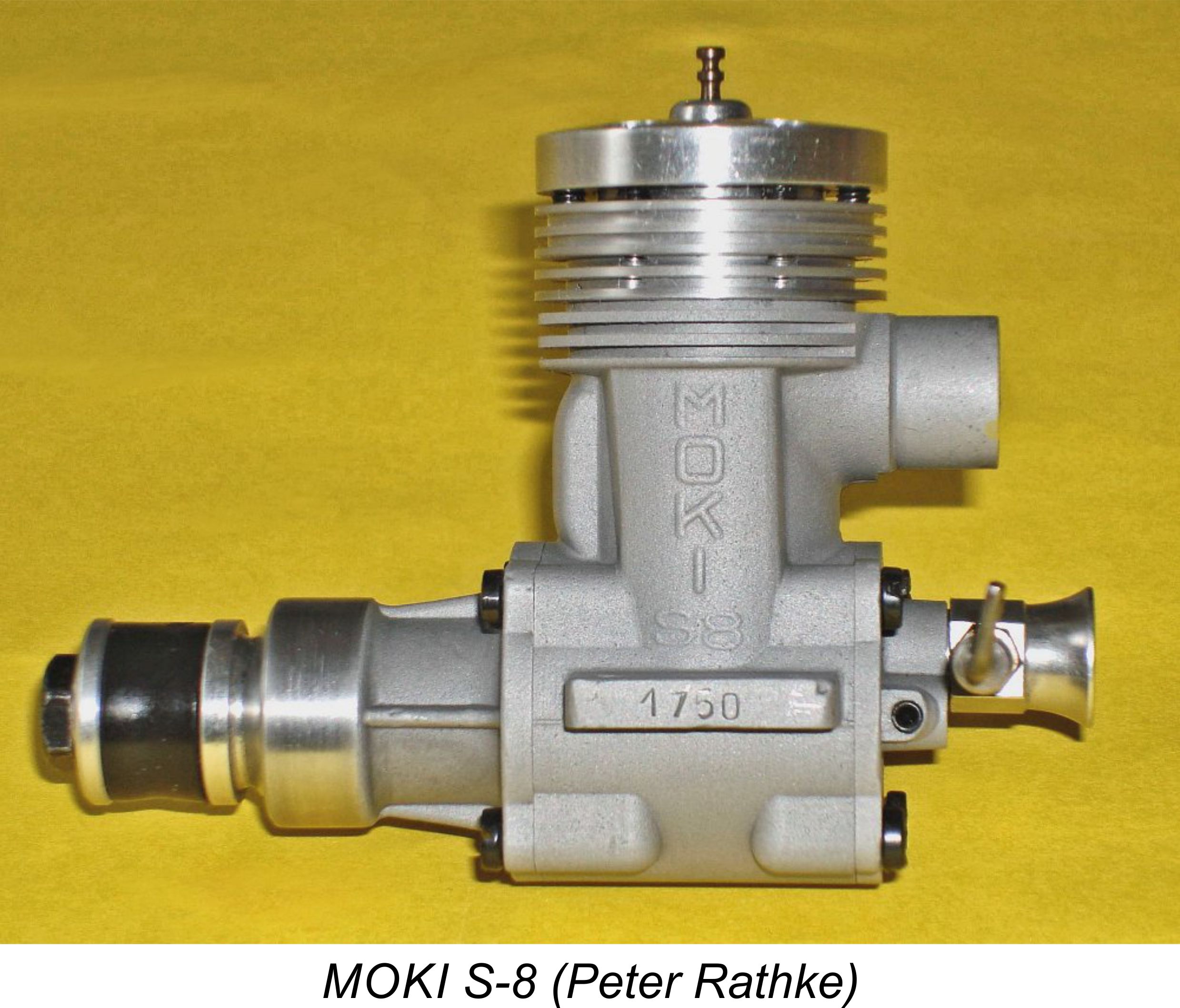

The FRV version of the MOKI S-8 was designated the MOKI S-8 F. Both variants were 2.5 cc glow-plug motors featuring Schnüerle porting with rear exhausts arranged for connection to a tuned pipe. The claimed maximum output of this motor without tuned pipe was 0.62 BHP @ at 27,000 rpm, while the addition of a tuned pipe raised this claim to 0.94 BHP @ 28,000 rpm.

In 1978 MOKI re-developed their previously-noted 1975 MOKI M-7 RC design into a rear exhaust form. 200 examples of this 10 cc engine were produced under the MOKI M-8 RC name. In addition, 100 examples of a water-cooled marine version of this engine were manufactured as the MOKI M-8 V.

It’s worth mentioning at this point that this engine continued to receive attention from the manufacturers for some time. In 1989, a revised version named the MOKI M-9 m was developed specifically for export. 1050 examples of this model were produced. Also in 1989, a further 500 examples of an even larger 30 cc version of the same engine were built under the name MOKI M-9 RC 30 (later to be re-named the MOKI M-180 RC). Returning now to 1983, that year saw the introduction of a new family of 2.5 cc engines which were grouped under the MOKI S-10 label. The designer in this case was Antal Szabadi. These FRV glow-plug motors were built in a number of forms for different purposes.

200 examples each were made of the basic MOKI S-10 RCo and MOKI S-10 RCh standard air-cooled versions, while 50 examples each were made of the water-cooled MOKI S-10 Vo and MOKI S-10 Vh variants. For car applications, 50 examples each of the MOKI S-10 Ao and MOKI S-10 Ah variants with expanded cooling fins were also made. In 1983, a very small series of only 15 examples of a 6.5 cc drum valve front exhaust engine intended expressly for hydroplane racing were produced. Unfortunately, there do not seem to be any photographs or details of this engine.

In 1988, 250 examples of a water-cooled 15 cc glow-plug engine called the MOKI S-14V were made. This engine also had a drum valve intake system with a revised carburetor. It was built both with a ringed aluminium piston and as an ABC unit. After the end of the Communist regime, it continued in production by the successor company under the name MOKI M-90 RC MARINE.

In 1988, MOKI introduced 3 different 6.5 cc glow-plug engines. For Pylon racing, 100 examples of the MOKI S-15 P design were built. The engine was basically very similar to the MOKI S-13 apart from having FRV induction to go with its Schnüerle porting and additional cooling fin area.

In 1989 MOKI produced a new generation 2.5 cc diesel engine, the MOKI TR-9, In 1990, more or less concurrently with the end of the Communist regime, (during which the attentive reader may recall that MOKI had been under the control of the Hungarian Civil Defence Association (MHSz)), the last engine from the original MOKI Institute was produced. The MOKI O-1 was a very simple Schnüerle ported 2.5 cc FRV glow-plug engine built for general purpose use. 300 examples of this engine were produced.

Following the change of regime, the types of engines and their displacements were rendered in cubic inches to be in step with the American market, which by now had become critical to MOKI’s survival. Thus the MOKI C-1 became the M 15 C, the MOKI TR-9 became the M 15 TR, the M-9 RC became the M-150 RC, and so on. During the final era of MOKI, conditions were such that very few engines could be sold on the domestic market. This meant that MOKI was forced to try to survive on the basis of the export market, primarily in the USA. However, the worldwide market for model engines was shrinking rapidly. MOKI soon stopped producing any further racing engines because there was almost no market for them. Naturally, this resulted in a decrease in MOKI production. Following the change in regimes, MOKI production never exceeded 1000 engines per year. One big disadvantage was the fact that the MOKI name was not protected under International law. Both in Germany and the USA, various firms abused the MOKI trade name by applying it to their products. Legal action was taken against the Eberle firm, but without success. In Japan, the MOKI designs were sold under the name Kyoso, while in Germany the names MIH and MARK were both used. None of these engines were genuine MOKI’s.

In 2000, a 22 cc FRV Schnüerle ported glow-plug engine was produced under the name MOKI M-135 RC. This engine was very similar indeed to the other big MOKI designs just described – a design pattern had formed. This model had increased cooling fin area. 2003 saw the start of production of a spark ignition version of the 30 cc MOKI M-180 RC glow-plug model (originally the MOKI M-9 RC 30), designated the MOKI G-180 RC. Apart from the ignition components, the main parts of the engine were very similar to those of the glow-plug version. (Editor's note: Reader Matias Rajkay, who is a friend of Dezsö Orsovai, has contacted me with Dezsö Orsovai's knowledge to point out that this latter statement is technically incorrect. The MOKI factory development team (which was headed up by Dezsö’s son and initially included Gyula Kriszma) put a major effort into the conversion of the glow-plug M-180 RC model, paying particular attention to the maintenance of good thermal stability under the new combustion regime. This effort included a considerably enlarged cooling fin area, a modified cylinder head and needle bearings on both ends of the conrod, along with a consequential slight change in the diameter of the wrist pin and piston bosses. Since the conrod also had to be made slightly wider at the big end to accomodate the needle bearing, the backplate was shimmed to cause it to intrude about 0.5 mm less into the crankcase. The crankshaft also underwent major changes: the glow-plug model accomodated the prop driver hub on a conical forward section, while the spark ignition engine had a cylindrical hole in the prop driver hub, with a Woodruff key used to position the prop driver hub very precisely. This was imperative because the prop driver hub carried the signal magnet for ignition timing. The main crankshaft bearing arrangement was also altered: the glow-plug engines sported open bearings on the front, while the spark ignition versions used shielded bearings. In reality therefore, the only unchanged parts were the head gasket, the piston ring, the cylinder liner and the rear main bearing!)

A major change came later in 2008. After over 50 years, MOKI was finally compelled to leave its premises at Budaőrs airport and moved to a building owned by a mechanical engineering company in Budapest. This signaled the beginning of the end – as the world market for model engines continued to decline, production slowed to a trickle until 2011, when it finally ceased. From that time up to my time of writing (August 2014), there has been no manufacture of MOKI engines in Hungary. Engines bearing the MOKI name are now produced solely by foreign firms using the MOKI trade name to identify their products. The best-known of these firms is the German AIRWORLD company, but its engines are not MOKI products or even MOKI designs. The sole connection with the genuine MOKI range is the use of the name. (Editor's note: Matias Rajkay has also noted that Somi quite understandably appeared to be incompletely informed regarding the marketing situation in Germany. Matias informs us that after Eberle had “stolen” the MOKI brand as mentioned by Somi, the factory attempted to work with several importers to legitimize their presence on the German market. One of these importers ordered a larger batch of 10 cc engines (the M-12 aka M-61 LS model) using the brand name “MIH”. The factory responded to this order by milling away the original MOKI logo from the cylinder and engraving a somewhat strange-looking “M” instead. Hence these MIH engines were in fact products of the MOKI factory. There have been other batches of renamed MOKI's, some of which were equipped with black-anodized cylinder heads. The brand-name “MARK” was applied by the MOKI factory for engines intended for markets in which the “MOKI” name had been misappropriated by others. This brand-name was first introduced in Germany, where the official distributor "Aero-Naut” marketed engines under this name. Matias was involved in selling these engines. All of the engines which he sold were genuine MOKI products which were supplied by the factory in boxes labelled “MARK”. The MARK logo was very similar to the MOKI logo except that it was not green on black, but yellow on black. Over time, more and more markets were converted to the “MARK” brand-name, including the U.S. The main point here is that all of these MARK engines were in fact genuine MOKI products. To facilitate this, the factory changed the dies for the engines - instead of the full name “MOKI”, the cases now bore only a letter "M" on the side, making them suitable for both MOKI and MARK market areas). To summarize, during the Communist era from 1957 to 1990 MOKI completely fulfilled its assigned task of supporting the development of model sport in Hungary. In particular, the Institution created outstanding racing engines for Hungarian competitors, who used those engines to gain consistently excellent results at the European and World Championship levels. Its bartering approach to the export of its engines also enhanced access by Hungarian modellers to R/C equipment from outside Hungary. The failure of MOKI to survive in the challenging business environment of the post-Communist era was not due to any shortcomings in their products but rather to a combination of competition from other firms usurping the unprotected MOKI name coupled with the continual erosion of the world market for model engines. The competition from cheap mass-produced “throwaway” engines from countries such as Taiwan and China did nothing to help. No-one was immune from such challenges, which is why we have now lost so many formerly famous model engine ranges, most recently the iconic Fox marque in America, and are in danger of losing more. It’s a great pity that a firm with such a proud tradition as MOKI had to be among them. Ferenc Somogyi Budapest, August 2014 _______________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan & Somogyi Ferenc, first published February 2015

|

| |

One of my earlier racing engine articles which elicited a good deal of interest was my piece about the

One of my earlier racing engine articles which elicited a good deal of interest was my piece about the  was far more than just another reader commenting on a specific article. He was an 85 year old (in 2014) retired mechanical engineer who was born in 1929. He was generally addressed by his English-speaking colleagues as Francis (an English rendering of Ferenc) but was known to his family and Hungarian friends by his nickname of Somi. At his specific request, I’ve referred to him as Somi throughout this article.

was far more than just another reader commenting on a specific article. He was an 85 year old (in 2014) retired mechanical engineer who was born in 1929. He was generally addressed by his English-speaking colleagues as Francis (an English rendering of Ferenc) but was known to his family and Hungarian friends by his nickname of Somi. At his specific request, I’ve referred to him as Somi throughout this article. However, beginning in 1944 when he was only 15 years old and WW2 was still going on around him, Somi had become increasingly involved with the Hungarian modelling movement, which had somehow managed to remain active at some level during the war years. Somi participated initially as a competitor and member of the Hungarian Association of Modelers, but later served at various times as a model club president, competition jury member, model engine designer (he designed the

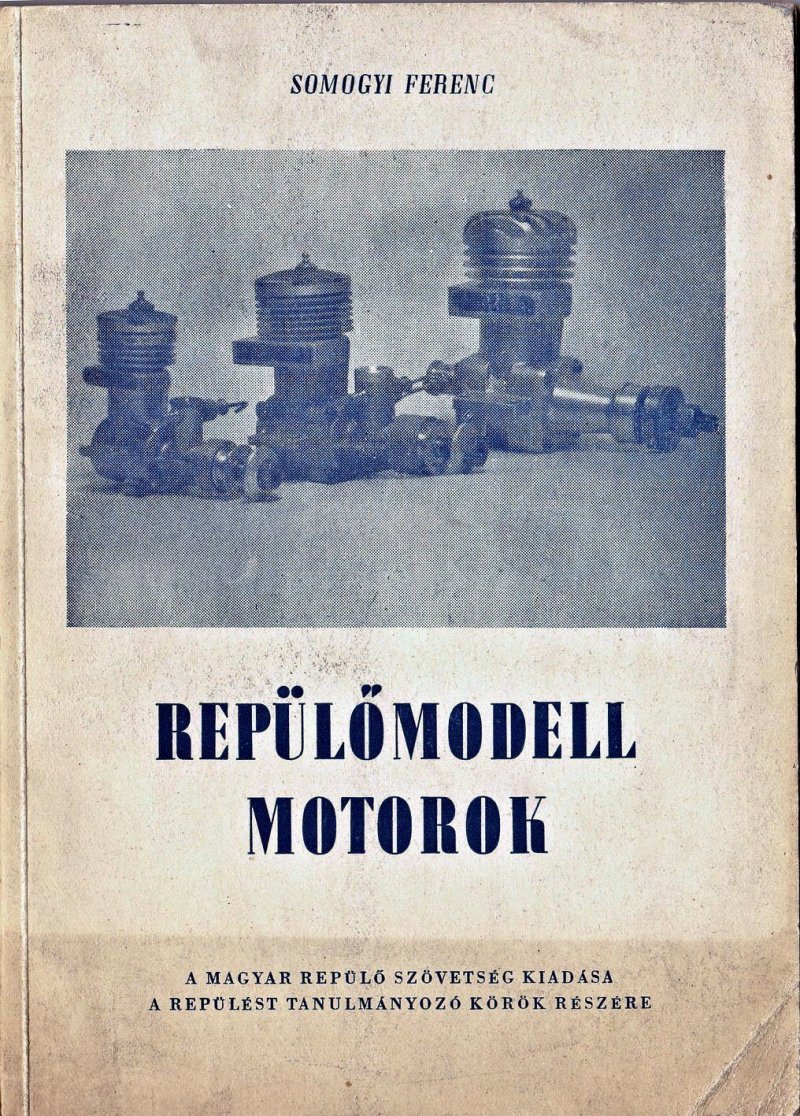

However, beginning in 1944 when he was only 15 years old and WW2 was still going on around him, Somi had become increasingly involved with the Hungarian modelling movement, which had somehow managed to remain active at some level during the war years. Somi participated initially as a competitor and member of the Hungarian Association of Modelers, but later served at various times as a model club president, competition jury member, model engine designer (he designed the  despite the fact that he was still attending University at the time, Somi also somehow found time to become a published author! His Hungarian-language book entitled "Repülömodell Motorok", which translates to "Model Aero Engines", was published in Hungary in 1953 when Somi was 24 years old. An English translation of this pioneering work would be of the greatest interest.

despite the fact that he was still attending University at the time, Somi also somehow found time to become a published author! His Hungarian-language book entitled "Repülömodell Motorok", which translates to "Model Aero Engines", was published in Hungary in 1953 when Somi was 24 years old. An English translation of this pioneering work would be of the greatest interest.  It was at this point in his career that Somi's work on behalf of the Hungarian modelling movement was officially recognized through the presentation to him of a service award from the Hungarian Aero Association. Quite an achievement for a 24 year old University student (Somi graduted in 1953)! However, this was by no means the end - rather, it was merely the end of the beginning!

It was at this point in his career that Somi's work on behalf of the Hungarian modelling movement was officially recognized through the presentation to him of a service award from the Hungarian Aero Association. Quite an achievement for a 24 year old University student (Somi graduted in 1953)! However, this was by no means the end - rather, it was merely the end of the beginning!  Somi (standing at the far right) with various members of the Hungarian team,

Somi (standing at the far right) with various members of the Hungarian team,

Subsequently becoming disenchanted with the direction that the war was taking as well as its economic and social impacts, the Hungarians unilaterally entered into secret peace negotiations with Britain and the USA to end their involvement on the Axis side. The German discovery of these initiatives led to the country being occupied by the Nazis in March 1944. This occupation lasted until April of 1945, by which point Soviet forces had taken over the occupation of the country from the Nazis against strong resistance in which the Hungarian Army played a full part.

Subsequently becoming disenchanted with the direction that the war was taking as well as its economic and social impacts, the Hungarians unilaterally entered into secret peace negotiations with Britain and the USA to end their involvement on the Axis side. The German discovery of these initiatives led to the country being occupied by the Nazis in March 1944. This occupation lasted until April of 1945, by which point Soviet forces had taken over the occupation of the country from the Nazis against strong resistance in which the Hungarian Army played a full part. To implement the required restoration, maintenance and upgrading activities, new workshops were established, among them the OMRE Központi Repülögépjavító Üzem, Budaörs (OMRE Central Aircraft Repair Plant, Budaörs) in June, 1948. The airfield at Budaörs immediately became the central sport-flying airfield for OMRE. It was later to play a central role in the MOKI story, as we shall see.

To implement the required restoration, maintenance and upgrading activities, new workshops were established, among them the OMRE Központi Repülögépjavító Üzem, Budaörs (OMRE Central Aircraft Repair Plant, Budaörs) in June, 1948. The airfield at Budaörs immediately became the central sport-flying airfield for OMRE. It was later to play a central role in the MOKI story, as we shall see. The remaining MRSz plant at Budaörs was relocated in 1952 to a newly-constructed sport flying airfield at Dunakeszi, a town lying just to the north of Budapest but still within the Budapest metropolitan area. This relocated facility was very successful in developing and manufacturing a series of gliders as well as undertaking modifications to powered aircraft to make them suitable for glider towing and flight training purposes.

The remaining MRSz plant at Budaörs was relocated in 1952 to a newly-constructed sport flying airfield at Dunakeszi, a town lying just to the north of Budapest but still within the Budapest metropolitan area. This relocated facility was very successful in developing and manufacturing a series of gliders as well as undertaking modifications to powered aircraft to make them suitable for glider towing and flight training purposes. However, there was a problem facing Hungarians interested in participating in power modelling at this time – a lack of suitable engines! Somi recalled that early post-war Hungarian modelers had a few Czechoslovakian and Soviet engines, but both the quality and performance of these engines were generally sub-standard at this time.

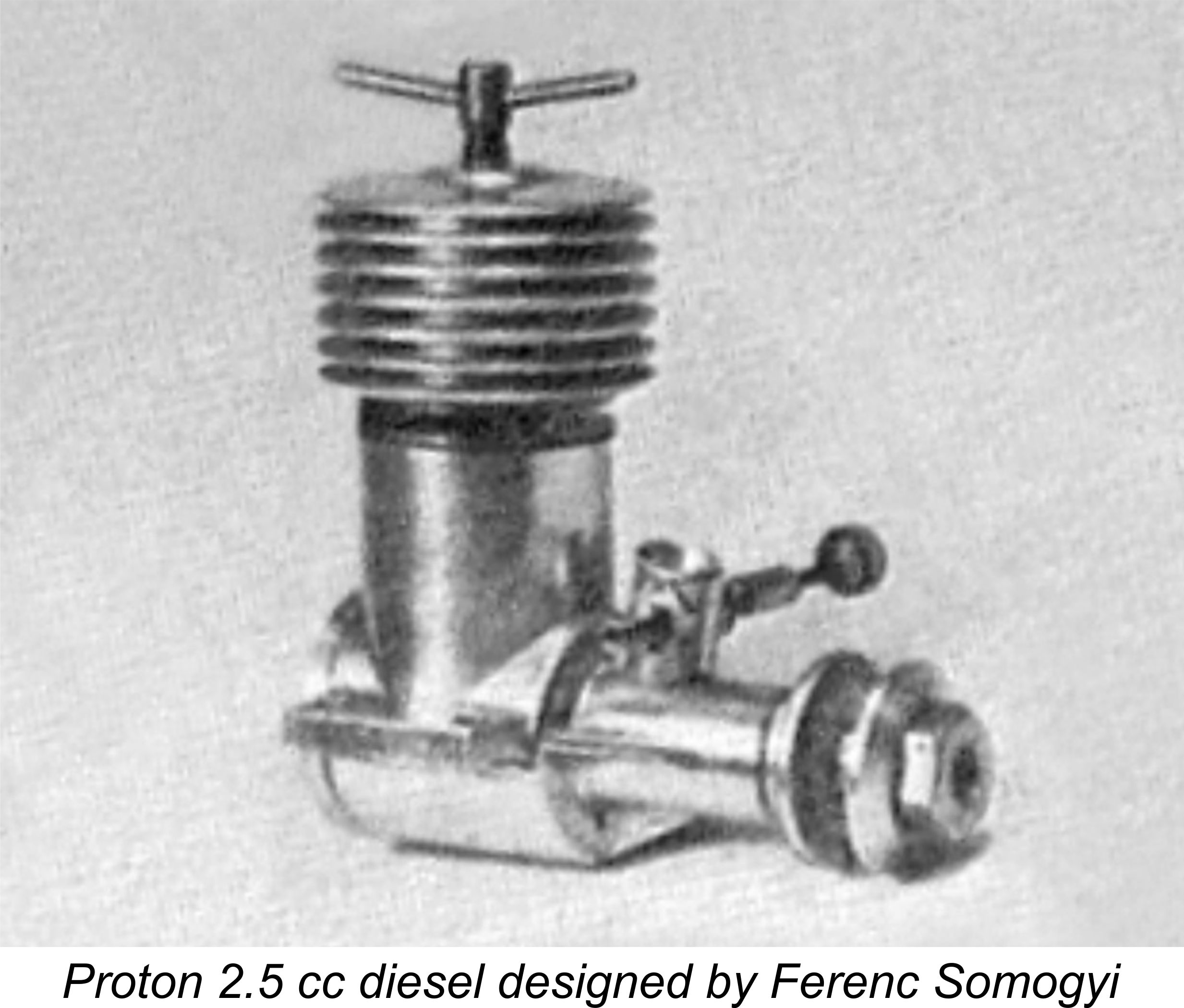

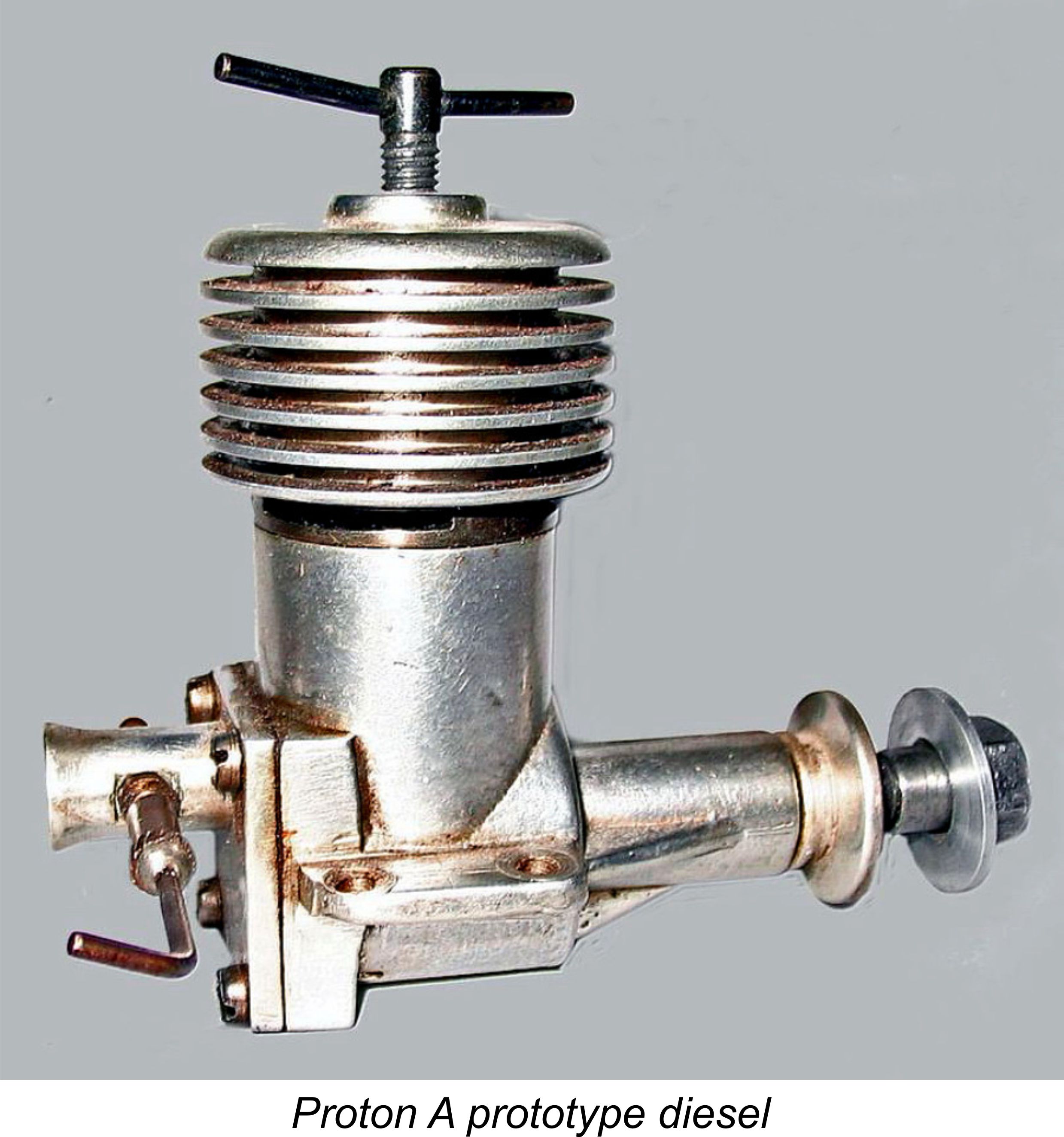

However, there was a problem facing Hungarians interested in participating in power modelling at this time – a lack of suitable engines! Somi recalled that early post-war Hungarian modelers had a few Czechoslovakian and Soviet engines, but both the quality and performance of these engines were generally sub-standard at this time. (a development of the HV-1) and the Proton series of model diesels. The designer of the Proton engines was none other than our Hungarian informant, Ferenc “Somi” Somogyi! This manufacturing venture was located in Szeged, a town situated in southern Hungary.

(a development of the HV-1) and the Proton series of model diesels. The designer of the Proton engines was none other than our Hungarian informant, Ferenc “Somi” Somogyi! This manufacturing venture was located in Szeged, a town situated in southern Hungary.

Hungarian model engine ranges. This organization appears to have been established in 1955, more or less concurrently with the start of Alag and VT production. Both of these ranges as well as the Proton engines were exported by ARTEX for the following 6 or 7 years, with some success.

Hungarian model engine ranges. This organization appears to have been established in 1955, more or less concurrently with the start of Alag and VT production. Both of these ranges as well as the Proton engines were exported by ARTEX for the following 6 or 7 years, with some success. First, I must acknowledge the sources which I used to assist my own memories of the engines and events described in what follows. During the writing of this article, I made reference to the book “MOKI Engines 1957 – 1990” by Zoltán Bimbi and also the book “The History of Model Engine Production in Hungary” by József Gere. In addition, Gyula Krizsma, Dezső Orsovai and István Horváth all graciously helped me out with some details.

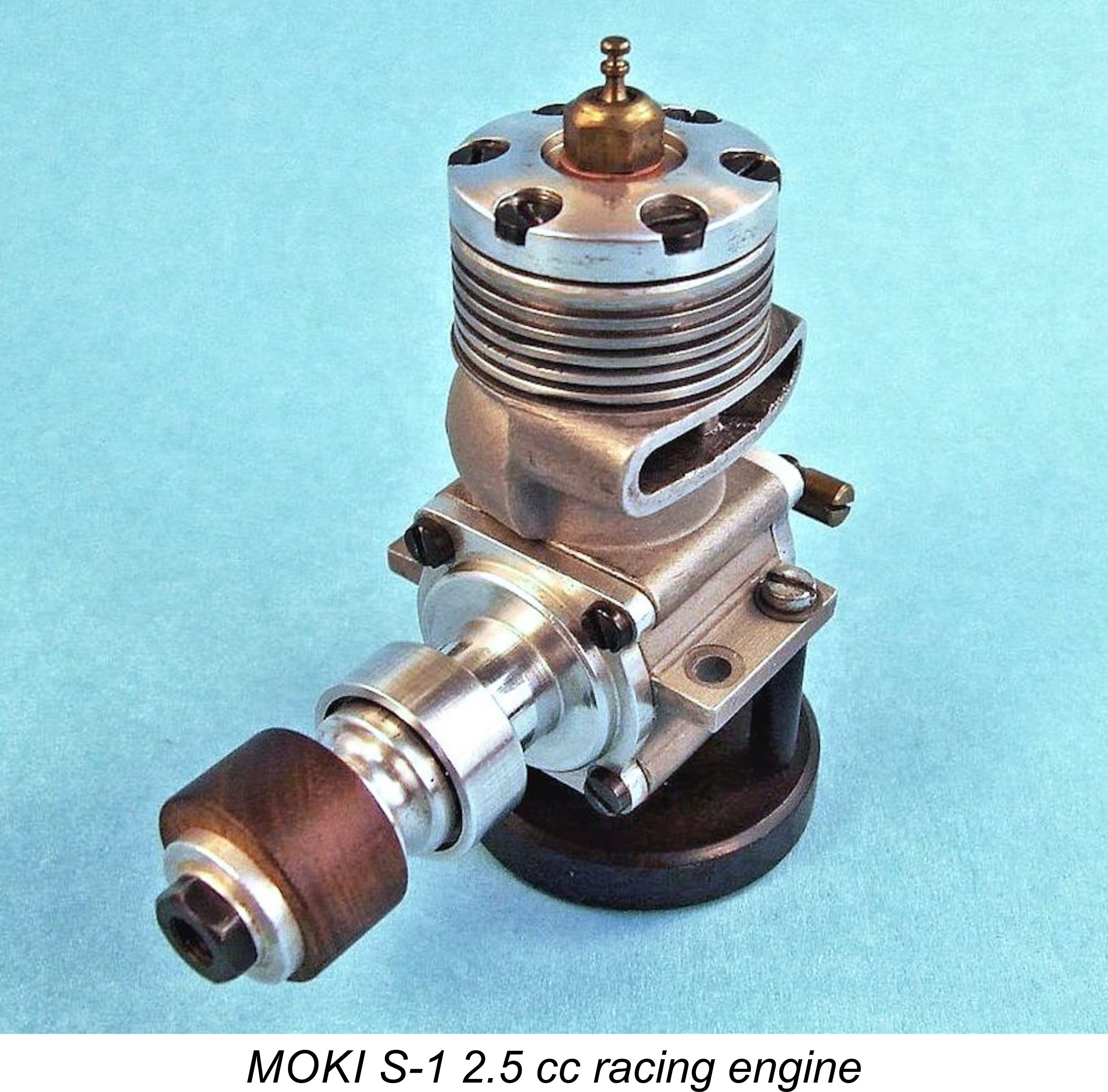

First, I must acknowledge the sources which I used to assist my own memories of the engines and events described in what follows. During the writing of this article, I made reference to the book “MOKI Engines 1957 – 1990” by Zoltán Bimbi and also the book “The History of Model Engine Production in Hungary” by József Gere. In addition, Gyula Krizsma, Dezső Orsovai and István Horváth all graciously helped me out with some details. The first model produced by MOKI was the MOKI S-1 glow-plug racing engine, which was designed by György Benedek. This 2.5 cc engine was designed expressly for control-line speed competition. It featured disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction with Dooling-style bypass porting utilizing extremely large piston ports, very like the competing (and very successful)

The first model produced by MOKI was the MOKI S-1 glow-plug racing engine, which was designed by György Benedek. This 2.5 cc engine was designed expressly for control-line speed competition. It featured disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction with Dooling-style bypass porting utilizing extremely large piston ports, very like the competing (and very successful)  Only ten examples of the MOKI S-1 were individually produced in 1958. The production of such a small number allowed for an ultra-high level of precision along with extensive testing. The resulting engines were used by the Hungarian team to take the team prize at the 1958 Control-Line Speed World Championships at Brussels, Belgium, with MOKI employee Imre Tóth taking top individual honors and Rezső Beck finishing second. Naturally, these results at the very first attempt made the MOKI name famous overnight. They also gave the established teams from Super Tigre and MVVS something to think about!!

Only ten examples of the MOKI S-1 were individually produced in 1958. The production of such a small number allowed for an ultra-high level of precision along with extensive testing. The resulting engines were used by the Hungarian team to take the team prize at the 1958 Control-Line Speed World Championships at Brussels, Belgium, with MOKI employee Imre Tóth taking top individual honors and Rezső Beck finishing second. Naturally, these results at the very first attempt made the MOKI name famous overnight. They also gave the established teams from Super Tigre and MVVS something to think about!!  MOKI’s second design was a team race diesel, the MOKI TR-1. This 2.5 cc crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) engine looked a lot like the Oliver Tiger Mk. III which was then the top team-race motor worldwide. Like the MOKI S-1, this model too was designed by György Benedek - Gyula Krizsma had yet to become associated with the MOKI venture. Twenty examples of this engine were produced in 1958. Another MOKI employee, László Azor, achieved fourth place at the 1958 World Team Race Championships using this engine. Once again, the name MOKI was beginning to mean something in the modelling world!

MOKI’s second design was a team race diesel, the MOKI TR-1. This 2.5 cc crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) engine looked a lot like the Oliver Tiger Mk. III which was then the top team-race motor worldwide. Like the MOKI S-1, this model too was designed by György Benedek - Gyula Krizsma had yet to become associated with the MOKI venture. Twenty examples of this engine were produced in 1958. Another MOKI employee, László Azor, achieved fourth place at the 1958 World Team Race Championships using this engine. Once again, the name MOKI was beginning to mean something in the modelling world!  production of 50 examples of the MOKI TR-4 team race diesel for distribution to promising Hungarian team race competitors. This model had a bolt-on main bearing housing. In the same year, MOKI produced an additional 20 examples of a further refined design, the MOKI TR-5, for the use of the national team members. This model returned to the Oliver pattern of having the main bearing housing and intake venturi cast integrally with the crankcase.

production of 50 examples of the MOKI TR-4 team race diesel for distribution to promising Hungarian team race competitors. This model had a bolt-on main bearing housing. In the same year, MOKI produced an additional 20 examples of a further refined design, the MOKI TR-5, for the use of the national team members. This model returned to the Oliver pattern of having the main bearing housing and intake venturi cast integrally with the crankcase. strictly for the use of national team members had been abandoned by this time, just as it had been over in Czechoslovakia at MVVS. From this point on, MOKI engines became increasingly available to modelers on a commercial basis, a trend which was reflected in the ever-increasing numbers produced. This was the only way to make the venture financially sustainable.

strictly for the use of national team members had been abandoned by this time, just as it had been over in Czechoslovakia at MVVS. From this point on, MOKI engines became increasingly available to modelers on a commercial basis, a trend which was reflected in the ever-increasing numbers produced. This was the only way to make the venture financially sustainable.

The resulting design was a 2.5 cc twin ball-race FRV glow-plug engine featuring a front bearing housing and intake venturi both cast integrally with the main crankcase. A plain lapped cast iron piston without rings was employed in a steel cylinder, with an unusually well-developed transfer system being featured. A simple threaded backplate was used, while the cylinder head was retained by four screws.

The resulting design was a 2.5 cc twin ball-race FRV glow-plug engine featuring a front bearing housing and intake venturi both cast integrally with the main crankcase. A plain lapped cast iron piston without rings was employed in a steel cylinder, with an unusually well-developed transfer system being featured. A simple threaded backplate was used, while the cylinder head was retained by four screws.  (Editor’s note – one of these engines somehow found its way into the hands of Ron Warring, the resident engine tester for the English “Aeromodeller” magazine. Warring’s

(Editor’s note – one of these engines somehow found its way into the hands of Ron Warring, the resident engine tester for the English “Aeromodeller” magazine. Warring’s  Externally it looked exactly like the glow-plug model except for the cylinder head. This engine was one of the increasingly rare “factory specials” – only 20 examples were made for the use of selected fliers. One of these engines was used by the Hungarian team of Azor and Kuhn to finish in third place at the 1961 World Team Race Championships. MOKI’s success at the highest levels was continuing unabated!

Externally it looked exactly like the glow-plug model except for the cylinder head. This engine was one of the increasingly rare “factory specials” – only 20 examples were made for the use of selected fliers. One of these engines was used by the Hungarian team of Azor and Kuhn to finish in third place at the 1961 World Team Race Championships. MOKI’s success at the highest levels was continuing unabated!  The M-3 was a 6 cc glowplug engine, of which 300 examples were produced. It was a basically conventional FRV plain bearing loop-scavenged stunt motor with a side-stack exhaust. The front bearing and intake venturi were cast integrally with the crankcase, which was sealed at the rear with a screw-in backplate. The cylinder liner had integrally-machined cooling fins, with a cylinder head which was secured using bolts which threaded into the crankcase.

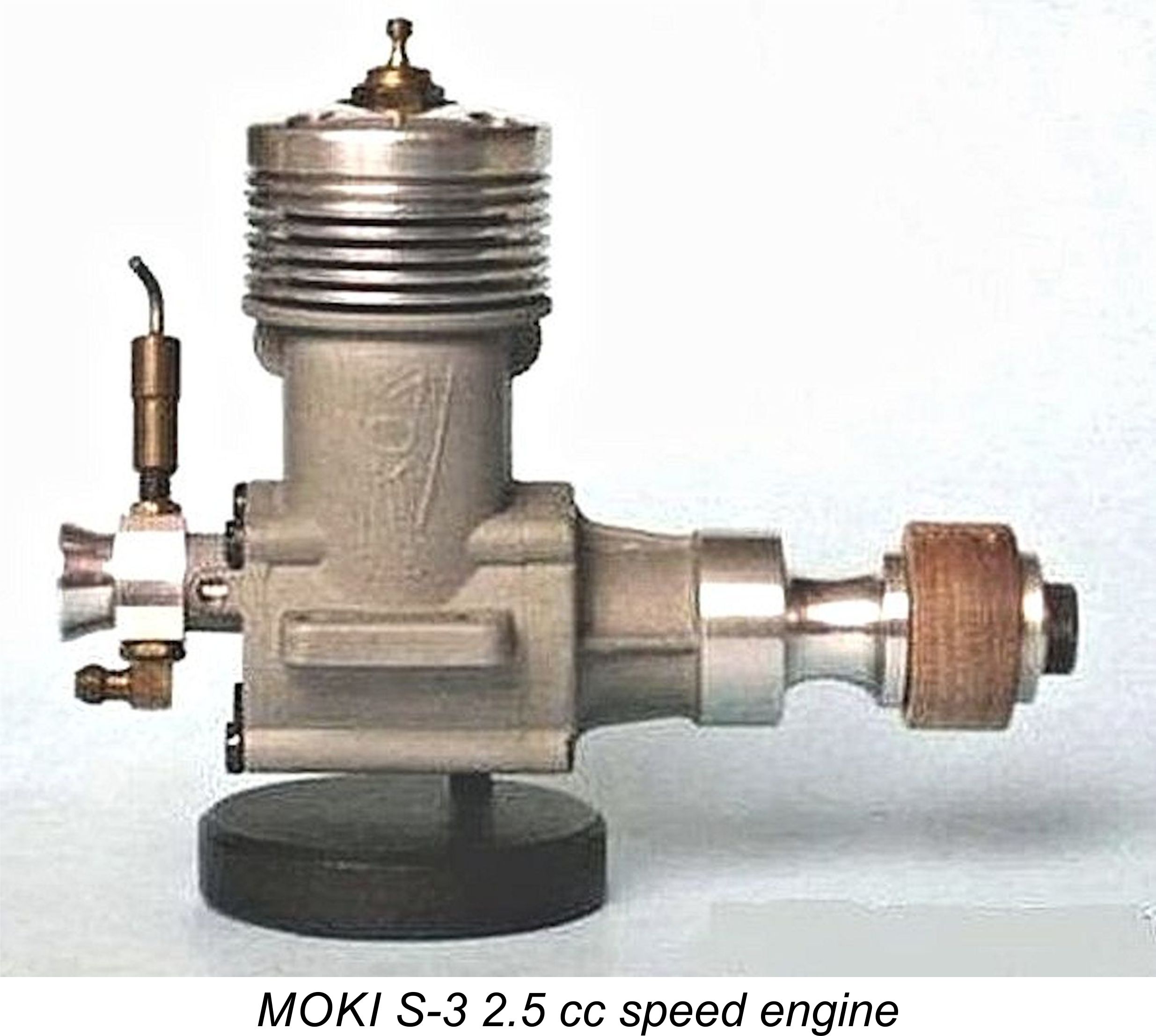

The M-3 was a 6 cc glowplug engine, of which 300 examples were produced. It was a basically conventional FRV plain bearing loop-scavenged stunt motor with a side-stack exhaust. The front bearing and intake venturi were cast integrally with the crankcase, which was sealed at the rear with a screw-in backplate. The cylinder liner had integrally-machined cooling fins, with a cylinder head which was secured using bolts which threaded into the crankcase.  Returning now to 1961, the success of the MOKI S-2 in the 1961 World Championships inspired Gyula Krizsma to make further efforts in the control line speed field. The result of his work was the 1962 appearance of the MOKI S-3 speed engine. This 2.5 cc twin ball-race glow-plug motor featured RRV induction using a disc valve as well as a detachable front housing. The venturi and needle valve assembly could be removed from the backplate as a unit. The factory claimed that this engine produced 0.408 BHP @ 20,300 rpm on straight FAI fuel, which improved to 0.538 BHP @ 21,000 rpm using a fuel containing 50% nitromethane.

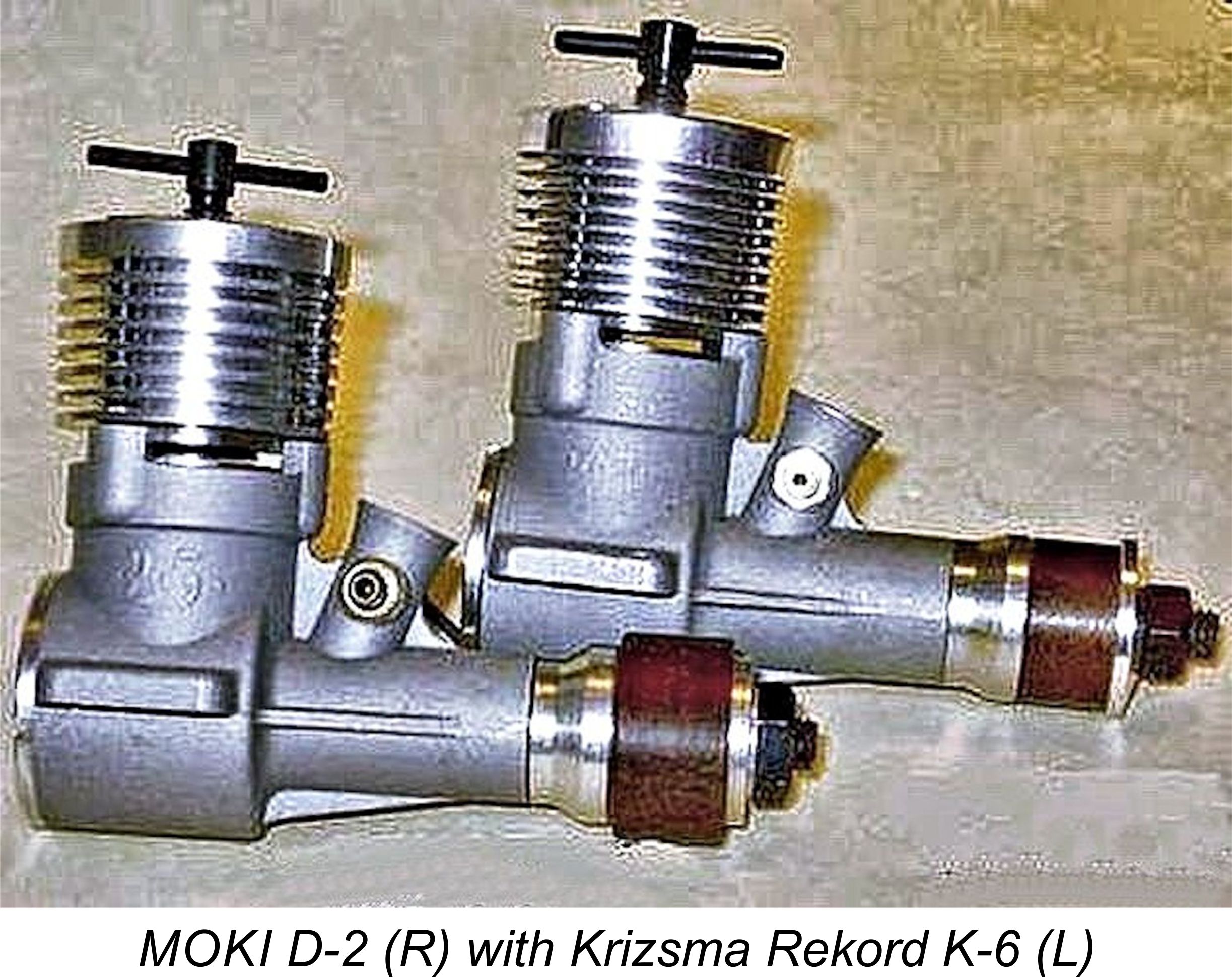

Returning now to 1961, the success of the MOKI S-2 in the 1961 World Championships inspired Gyula Krizsma to make further efforts in the control line speed field. The result of his work was the 1962 appearance of the MOKI S-3 speed engine. This 2.5 cc twin ball-race glow-plug motor featured RRV induction using a disc valve as well as a detachable front housing. The venturi and needle valve assembly could be removed from the backplate as a unit. The factory claimed that this engine produced 0.408 BHP @ 20,300 rpm on straight FAI fuel, which improved to 0.538 BHP @ 21,000 rpm using a fuel containing 50% nitromethane. For the use of beginning control line stunt fliers, the MOKI D-2 was designed in 1963. This was a simple 2.5 cc plain bearing diesel engine having radial cylinder porting to go with FRV induction. The crankcase casting was based on that of Gyula Krizsma’s earlier K-6 design. Some 600 examples of this engine were manufactured, primarily as a commercial venture.

For the use of beginning control line stunt fliers, the MOKI D-2 was designed in 1963. This was a simple 2.5 cc plain bearing diesel engine having radial cylinder porting to go with FRV induction. The crankcase casting was based on that of Gyula Krizsma’s earlier K-6 design. Some 600 examples of this engine were manufactured, primarily as a commercial venture.  1963 was a busy year for MOKI, since in that year the workshop also produced a 5 cc glow-plug speed engine called the MOKI S-4. This engine followed the design pattern established by the 2.5 cc MOKI S-3. It featured RRV induction, a bolt-on front housing and a cast iron piston which was lapped into the steel cylinder.

1963 was a busy year for MOKI, since in that year the workshop also produced a 5 cc glow-plug speed engine called the MOKI S-4. This engine followed the design pattern established by the 2.5 cc MOKI S-3. It featured RRV induction, a bolt-on front housing and a cast iron piston which was lapped into the steel cylinder. The MOKI S-4 was followed in 1965 by a 10 cc glowplug speed unit called the MOKI S-5. This engine too was patterned and constructed along very similar lines to the MOKI S-3 mentioned earlier. The factory claimed a seemingly rather conservative output of 1.0 BHP @ 17,000 rpm for this model - one would expect an engine of this specification to do better! Both the S-4 and S-5 were not only popular among control-line speed fliers – they also found great favor with Hungarian model car and hydroplane racers, being used to win European championships for Hungary in both categories.

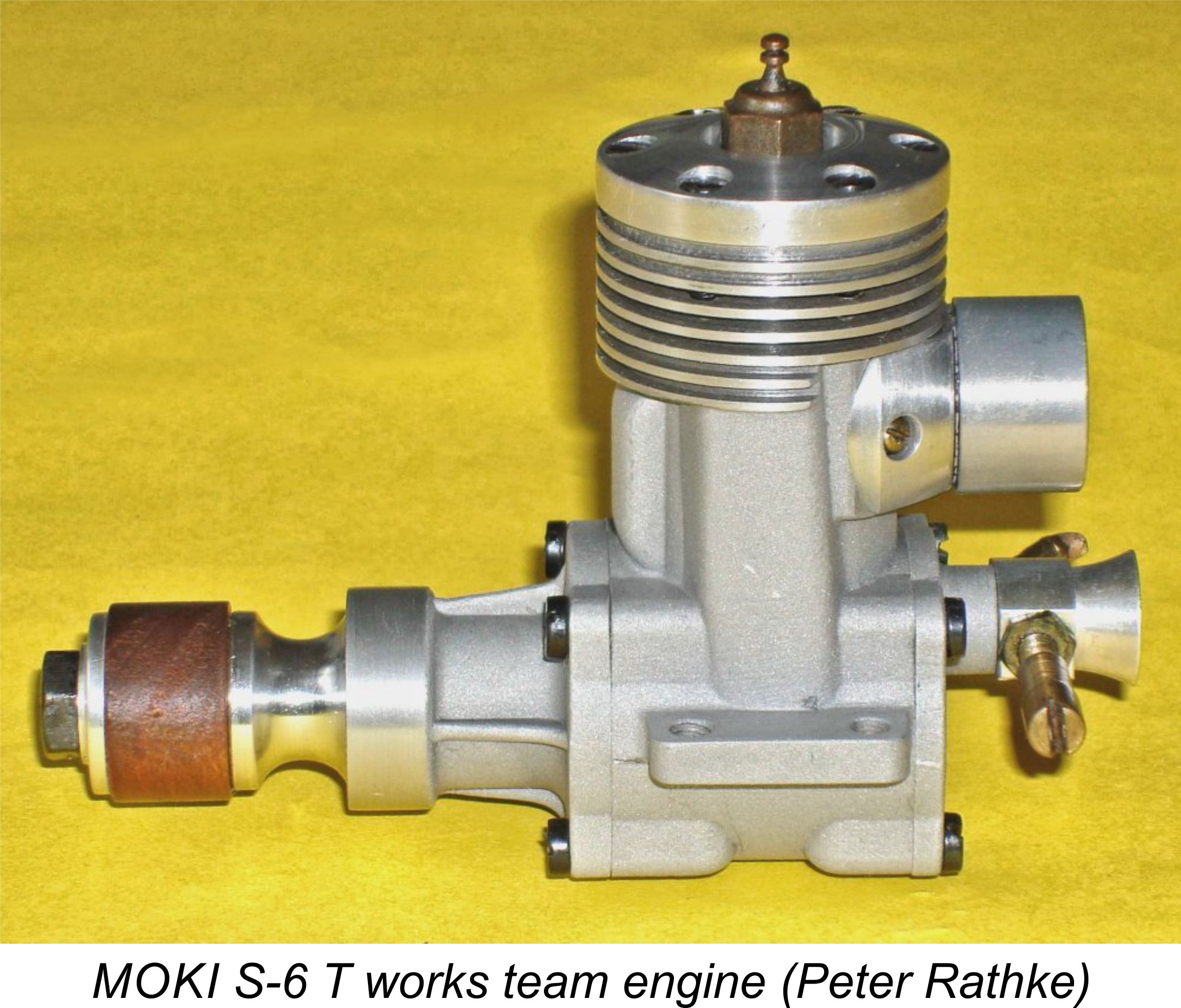

The MOKI S-4 was followed in 1965 by a 10 cc glowplug speed unit called the MOKI S-5. This engine too was patterned and constructed along very similar lines to the MOKI S-3 mentioned earlier. The factory claimed a seemingly rather conservative output of 1.0 BHP @ 17,000 rpm for this model - one would expect an engine of this specification to do better! Both the S-4 and S-5 were not only popular among control-line speed fliers – they also found great favor with Hungarian model car and hydroplane racers, being used to win European championships for Hungary in both categories. It was immediately clear that tuned pipes were now a necessity to win at the international level. MOKI responded to this challenge very quickly despite the fact that a lot of experimental work was required to optimize the design of the tuned pipe and the associated engine porting. Despite this challenge, ten examples of MOKI’s first tuned pipe speed engine, the MOKI S-6, were produced by late 1966. Bill Wisniewski’s truly commendable willingness to share his hard-won knowledge about tuned pipes must have helped, but even so this was a remarkable achievement. This design was later modified by Krizsma in collaboration with Imre Tóth to produce the MOKI S-6 T, of which 200 examples were produced in 1967 in a number of variants.

It was immediately clear that tuned pipes were now a necessity to win at the international level. MOKI responded to this challenge very quickly despite the fact that a lot of experimental work was required to optimize the design of the tuned pipe and the associated engine porting. Despite this challenge, ten examples of MOKI’s first tuned pipe speed engine, the MOKI S-6, were produced by late 1966. Bill Wisniewski’s truly commendable willingness to share his hard-won knowledge about tuned pipes must have helped, but even so this was a remarkable achievement. This design was later modified by Krizsma in collaboration with Imre Tóth to produce the MOKI S-6 T, of which 200 examples were produced in 1967 in a number of variants. The MOKI S-6 and S-6 T were 2.5 cc glow-plug engines featuring Schnüerle porting, RRV induction using a rear disc valve, a lapped cast iron piston and a steel cylinder. They had a rear exhaust port which was fitted with a tubular stack to facilitate the connection to a tuned pipe. The S-6 T was an immediate success, with Imre Tóth becoming the 1967 European Champion and the similarly-equipped Hungarian team taking the team prize as well. The MOKI S-6 T was greatly appreciated by Hungarian competitors, who enjoyed considerable International success using the engine in the car and hydroplane fields as well as aircraft. Claimed output for this engine was 0.77 BHP @ 27,500 rpm on straight fuel, increasing to 0.85 BHP @ 29,000 rpm on nitrated fuel.

The MOKI S-6 and S-6 T were 2.5 cc glow-plug engines featuring Schnüerle porting, RRV induction using a rear disc valve, a lapped cast iron piston and a steel cylinder. They had a rear exhaust port which was fitted with a tubular stack to facilitate the connection to a tuned pipe. The S-6 T was an immediate success, with Imre Tóth becoming the 1967 European Champion and the similarly-equipped Hungarian team taking the team prize as well. The MOKI S-6 T was greatly appreciated by Hungarian competitors, who enjoyed considerable International success using the engine in the car and hydroplane fields as well as aircraft. Claimed output for this engine was 0.77 BHP @ 27,500 rpm on straight fuel, increasing to 0.85 BHP @ 29,000 rpm on nitrated fuel. It is worth noting for the record at this point that since their first appearance in 1958, MOKI engines had now won the World and/or European Control Line Speed Championships in five of the ten years in which they had competed. No other marque could boast such a record!

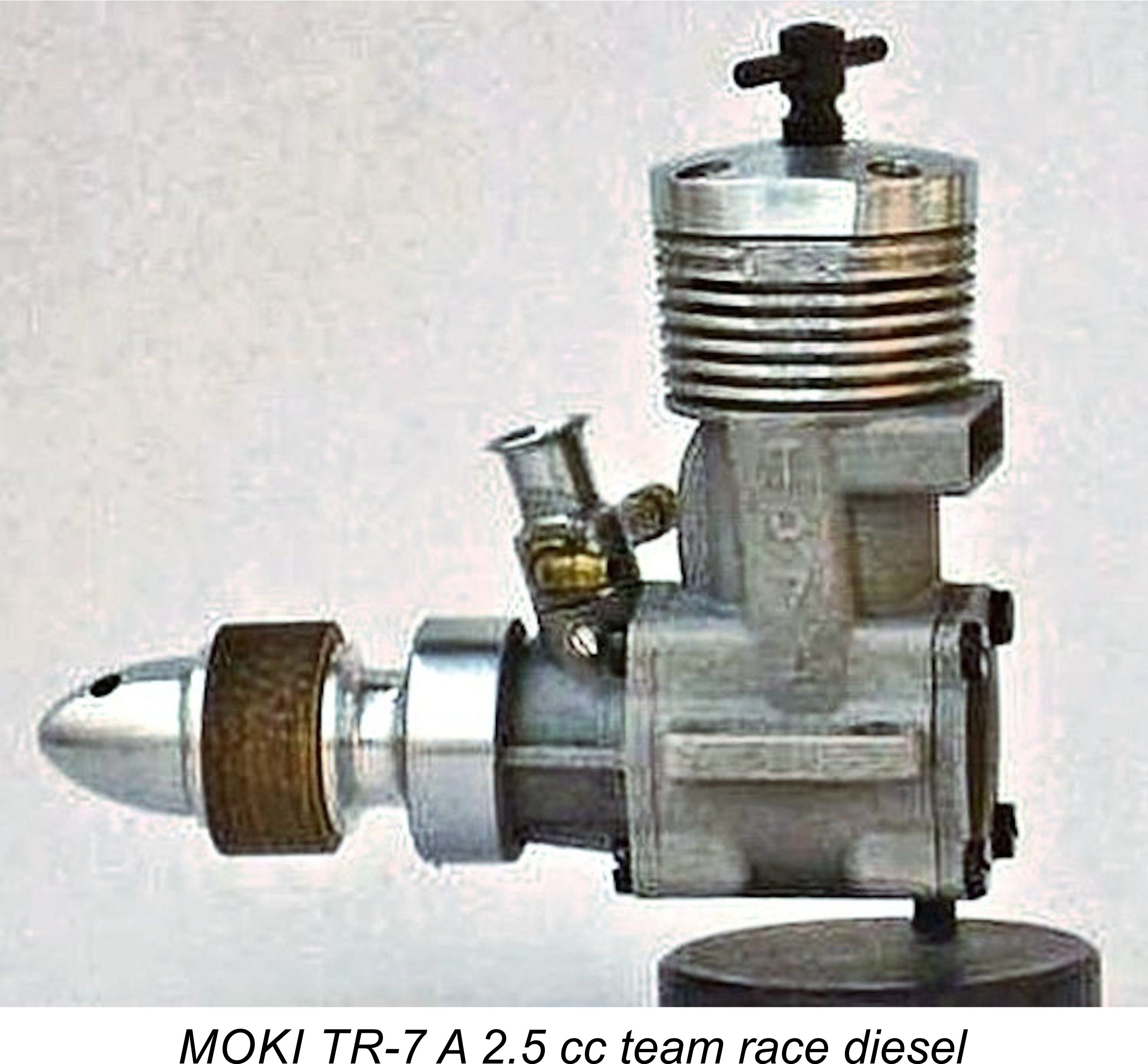

It is worth noting for the record at this point that since their first appearance in 1958, MOKI engines had now won the World and/or European Control Line Speed Championships in five of the ten years in which they had competed. No other marque could boast such a record!  in 1967. The construction of this 2.5 cc engine deviated significantly from that of the earlier TR engines. The new design featured FRV induction, Schnüerle porting and a rear exhaust with rectangular stack. Both the front bearing housing and the backplate were secured to the crankcase with bolts. The venturi and carburetor were a separate unit which was removable from the front housing. The cooling fins on the cylinder and cylinder head were flattened on both sides to facilitate mounting in a team racer.

in 1967. The construction of this 2.5 cc engine deviated significantly from that of the earlier TR engines. The new design featured FRV induction, Schnüerle porting and a rear exhaust with rectangular stack. Both the front bearing housing and the backplate were secured to the crankcase with bolts. The venturi and carburetor were a separate unit which was removable from the front housing. The cooling fins on the cylinder and cylinder head were flattened on both sides to facilitate mounting in a team racer.

In 1971 the growing popularity of really large R/C models led MOKI to introduce its largest glow-plug model up to that time, the 25 cc MOKI-M6 RC. This model was basically very similar to the earlier MOKI M-5 RC just described, although the front bearing housing of the larger model was later made removable. 600 examples of this design were manufactured.

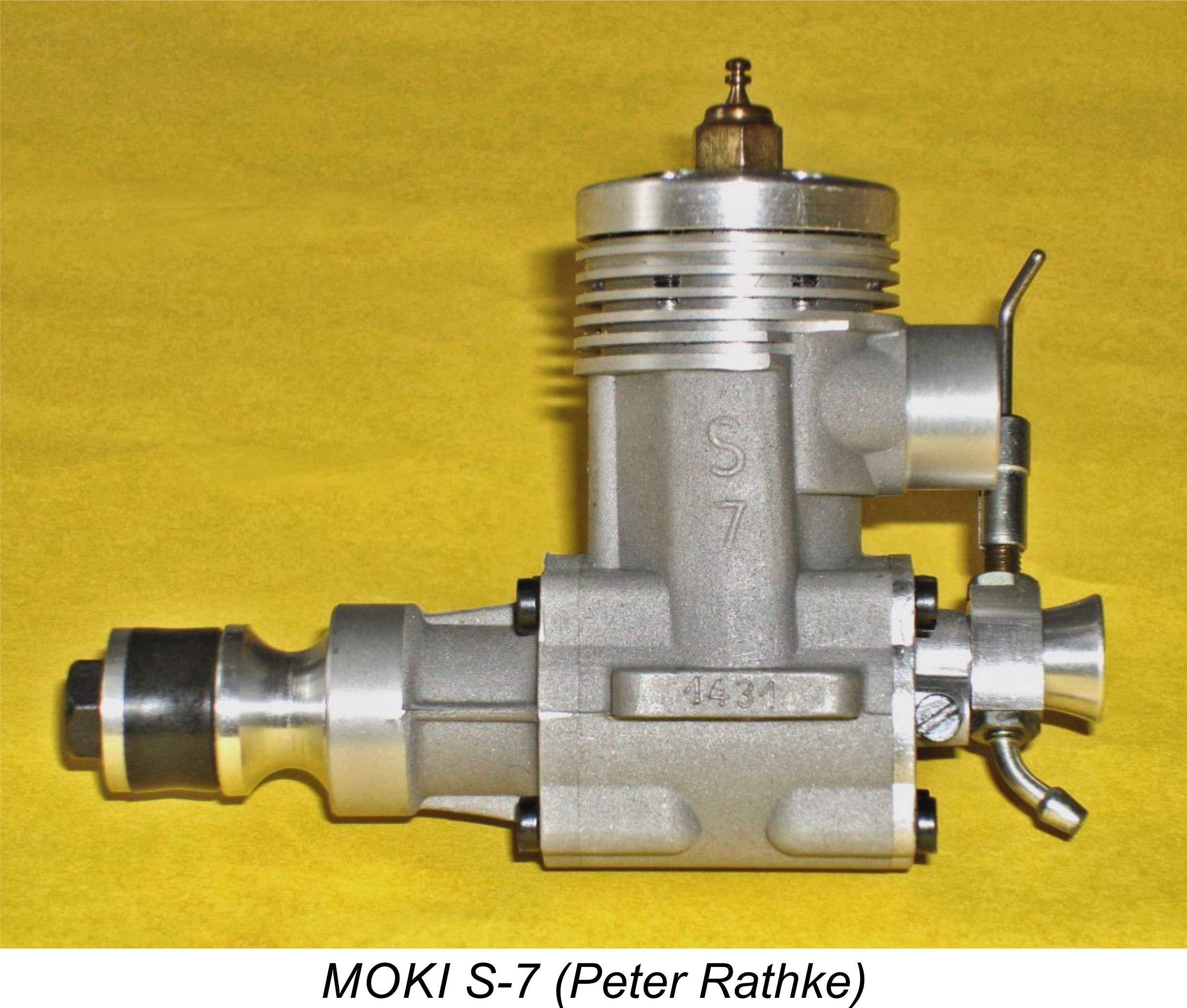

In 1971 the growing popularity of really large R/C models led MOKI to introduce its largest glow-plug model up to that time, the 25 cc MOKI-M6 RC. This model was basically very similar to the earlier MOKI M-5 RC just described, although the front bearing housing of the larger model was later made removable. 600 examples of this design were manufactured. As we would expect from a man with his credentials, Gyula Krizsma retained a strong interest in speed engines. In 1973 he introduced the MOKI S-7 speed motor of 2.5 cc displacement. This engine was built both in FRV and RRV versions, with 150 examples of each version being produced. Both versions featured Schnüerle porting with rear exhausts having a connection for a tuned pipe. Both the main bearing housing and the backplate were secured to the crankcase with bolts. In 1974 twenty examples of a diesel version of the FRV MOKI S-7 were produced under the name MOKI S-7 D.

As we would expect from a man with his credentials, Gyula Krizsma retained a strong interest in speed engines. In 1973 he introduced the MOKI S-7 speed motor of 2.5 cc displacement. This engine was built both in FRV and RRV versions, with 150 examples of each version being produced. Both versions featured Schnüerle porting with rear exhausts having a connection for a tuned pipe. Both the main bearing housing and the backplate were secured to the crankcase with bolts. In 1974 twenty examples of a diesel version of the FRV MOKI S-7 were produced under the name MOKI S-7 D. In 1973, seeking to expand the range of its commercial market potential, MOKI produced 450 examples of a 2.5 cc diesel engine bearing the name MOKI Sport D. These were built specifically for beginners and sport fliers. The very simple engines featured plain bearings with FRV induction and Schnüerle porting. In 1975, 450 examples of a glow-plug version of this engine were manufactured under the name MOKI Sport 1. Apart from the different ignition systems, the diesel and glow-plug models were identical.

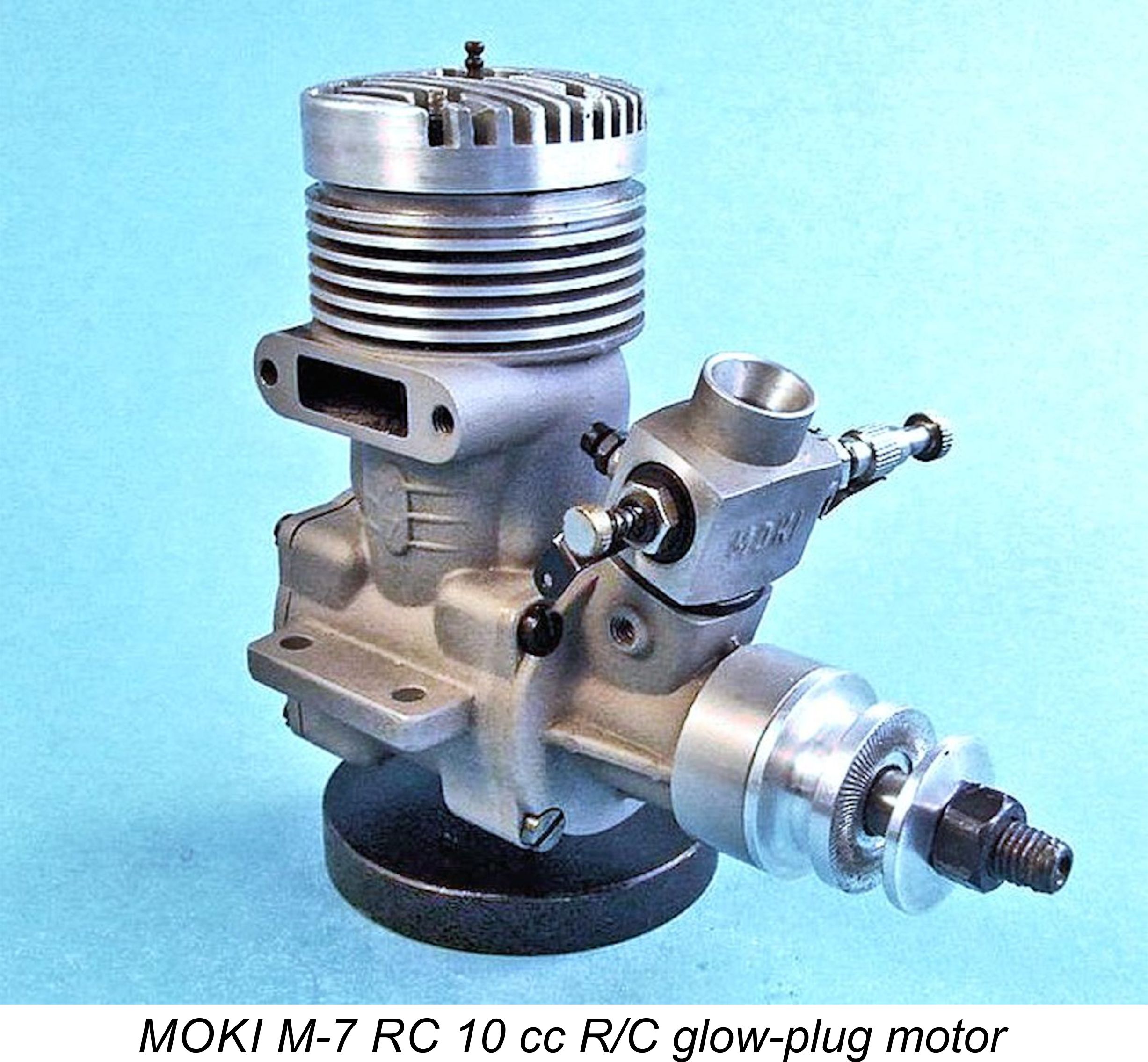

In 1973, seeking to expand the range of its commercial market potential, MOKI produced 450 examples of a 2.5 cc diesel engine bearing the name MOKI Sport D. These were built specifically for beginners and sport fliers. The very simple engines featured plain bearings with FRV induction and Schnüerle porting. In 1975, 450 examples of a glow-plug version of this engine were manufactured under the name MOKI Sport 1. Apart from the different ignition systems, the diesel and glow-plug models were identical. Also in 1975, a further development of the MOKI M-5 RC from 1970 appeared as the MOKI M-7 RC. This eventually earned the distinction of becoming the MOKI model of which the greatest number was produced. MOKI ended up making 6759 examples, mainly for export. The MOKI M-7 RC was a 10 cc glow-plug engine with FRV induction, Schnüerle porting, a side-stack exhaust and a twin ball-race shaft. The engine was produced both with a steel liner/ringed alloy piston combination and in an ABC version. In 1976, 200 examples of a water cooled version for marine use were constructed as the MOKI M-7 V.

Also in 1975, a further development of the MOKI M-5 RC from 1970 appeared as the MOKI M-7 RC. This eventually earned the distinction of becoming the MOKI model of which the greatest number was produced. MOKI ended up making 6759 examples, mainly for export. The MOKI M-7 RC was a 10 cc glow-plug engine with FRV induction, Schnüerle porting, a side-stack exhaust and a twin ball-race shaft. The engine was produced both with a steel liner/ringed alloy piston combination and in an ABC version. In 1976, 200 examples of a water cooled version for marine use were constructed as the MOKI M-7 V. The MOKI S-8 was a further development of MOKI’s speed engine series which appeared in 1975 in both FRV and RRV variants, just like its S-7 predecessor. 150 examples of each variant were produced. These relatively low numbers of course reflect the fact that the market for racing engines was even then in the process of shrinking rapidly. The R/C market was becoming dominant, and engines for that purpose were getting bigger!

The MOKI S-8 was a further development of MOKI’s speed engine series which appeared in 1975 in both FRV and RRV variants, just like its S-7 predecessor. 150 examples of each variant were produced. These relatively low numbers of course reflect the fact that the market for racing engines was even then in the process of shrinking rapidly. The R/C market was becoming dominant, and engines for that purpose were getting bigger! In 1976, 50 examples of a completely revised high performance 10 cc R/C glow-plug engine were produced as the MOKI S-9 RC. This was a Schnüerle ported RRV engine with an R/C carburetor. It featured a rear exhaust with provision for the attachment of a tuned pipe. Both ringed piston and ABC versions were manufactured. In this same year, 50 examples of a water-cooled marine version were produced as the MOKI S-9 V. Apart from the water cooling, this was very similar to the air cooled version.

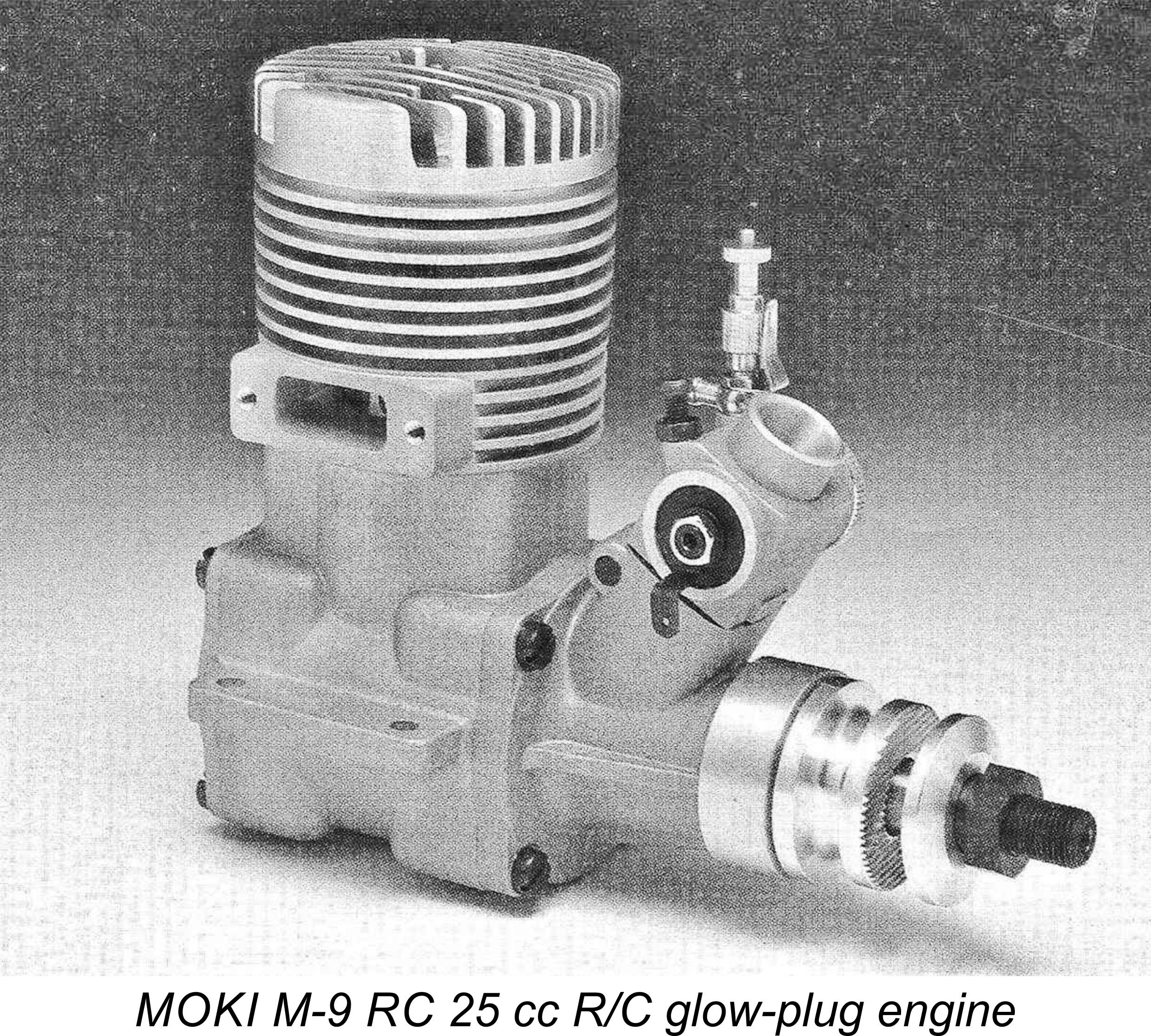

In 1976, 50 examples of a completely revised high performance 10 cc R/C glow-plug engine were produced as the MOKI S-9 RC. This was a Schnüerle ported RRV engine with an R/C carburetor. It featured a rear exhaust with provision for the attachment of a tuned pipe. Both ringed piston and ABC versions were manufactured. In this same year, 50 examples of a water-cooled marine version were produced as the MOKI S-9 V. Apart from the water cooling, this was very similar to the air cooled version. By this time, the R/C market was totally dominant and engines were still getting bigger! In 1981, 1000 examples of the 25 cc MOKI M-9 RC glow-plug engine were manufactured. This model was later renamed the MOKI M-150 RC. The engine featured FRV induction with a side-stack exhaust.

By this time, the R/C market was totally dominant and engines were still getting bigger! In 1981, 1000 examples of the 25 cc MOKI M-9 RC glow-plug engine were manufactured. This model was later renamed the MOKI M-150 RC. The engine featured FRV induction with a side-stack exhaust. This series represents the first deviation from the model identification system whch had been applied quite rigorously up to this point. The S designation had previously been reserved for all-out speed engines. However, the S-10 models were produced in a wide variety of configurations for widely-differing purposes. There were air and water cooled versions for aero, car and marine applications, with both side and rear exhaust systems being featured on different variants. Moreover, the engines were produced in both ringed piston and ABC versions. Confusing!!

This series represents the first deviation from the model identification system whch had been applied quite rigorously up to this point. The S designation had previously been reserved for all-out speed engines. However, the S-10 models were produced in a wide variety of configurations for widely-differing purposes. There were air and water cooled versions for aero, car and marine applications, with both side and rear exhaust systems being featured on different variants. Moreover, the engines were produced in both ringed piston and ABC versions. Confusing!!  1984 saw the start of production of the MOKI S-12 speed engine, which turned out to be MOKI’s final design for control line speed flying. This 2.5 cc unit featured FRV induction, Schnüerle porting and a rear exhaust which could be fitted with a tuned pipe if desired. At this time, only a relatively short series of 500 examples was produced. However, after the end of the Communist regime in late 1989, this engine was re-introduced by MOKI’s successor company, remaining in limited production for some time in both FRV and RRV variants.

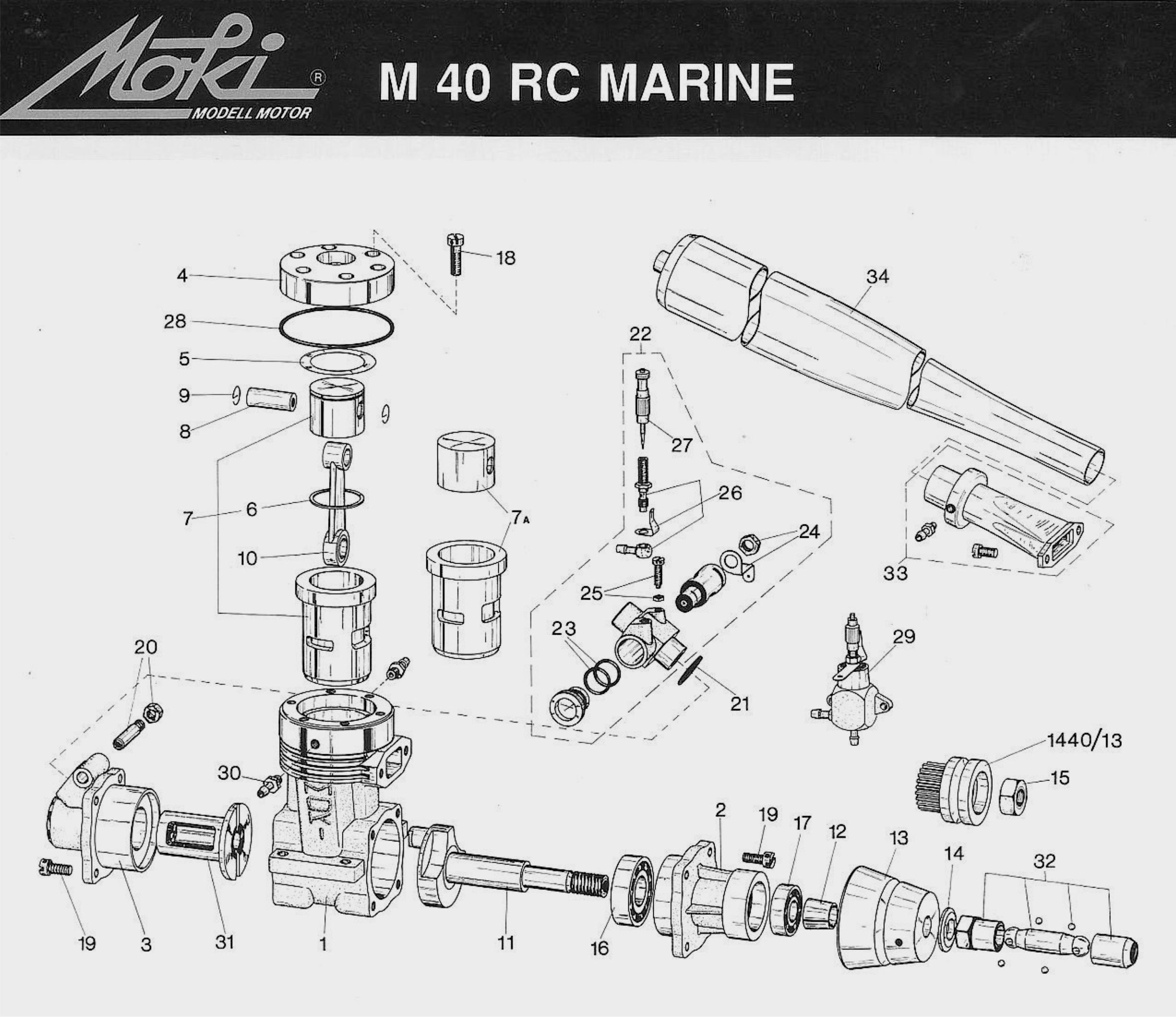

1984 saw the start of production of the MOKI S-12 speed engine, which turned out to be MOKI’s final design for control line speed flying. This 2.5 cc unit featured FRV induction, Schnüerle porting and a rear exhaust which could be fitted with a tuned pipe if desired. At this time, only a relatively short series of 500 examples was produced. However, after the end of the Communist regime in late 1989, this engine was re-introduced by MOKI’s successor company, remaining in limited production for some time in both FRV and RRV variants. In 1985, 55 examples of a water-cooled 6.5 cc glow-plug engine named the MOKI S-13 V were built. The engine had a drum valve intake system, implying that it probably evolved from the undocumented 1983 design mentioned earlier. After the change of regime in 1989, MOKI’s successor company made similar engines under the name MOKI M-40 RC MARINE. The details of this engine can be seen on the attached drawing.

In 1985, 55 examples of a water-cooled 6.5 cc glow-plug engine named the MOKI S-13 V were built. The engine had a drum valve intake system, implying that it probably evolved from the undocumented 1983 design mentioned earlier. After the change of regime in 1989, MOKI’s successor company made similar engines under the name MOKI M-40 RC MARINE. The details of this engine can be seen on the attached drawing. To meet the needs of Hungarian control-line stunt fliers, 200 examples of an 8.5 cc FRV glow-plug engine were produced in 1987 as the MOKI M-10. Apart from its far smaller displacement, the engine was very similar in design terms to the MOKI M-9. The exhaust stack was arranged to accept a matching muffler.

To meet the needs of Hungarian control-line stunt fliers, 200 examples of an 8.5 cc FRV glow-plug engine were produced in 1987 as the MOKI M-10. Apart from its far smaller displacement, the engine was very similar in design terms to the MOKI M-9. The exhaust stack was arranged to accept a matching muffler. This engine was also produced in two water-cooled versions intended for high-performance model boats. 200 examples of the MOKI S-15 V and 100 examples of the MOKI S-15 Vd were built. Both engines featured drum valve induction, R/C carburetors and short venturis. However, the exhaust stack of the S-15 V was at the rear, at the same end of the engine as the intake. The engine drove the load through a pulley or gear at the flywheel end, drive thus being indirect. By contrast, the S-15 Vd had direct drive from the flywheel, with the exhaust stack at the crankshaft end of the unit. Both engines were equipped with tuned pipes.

This engine was also produced in two water-cooled versions intended for high-performance model boats. 200 examples of the MOKI S-15 V and 100 examples of the MOKI S-15 Vd were built. Both engines featured drum valve induction, R/C carburetors and short venturis. However, the exhaust stack of the S-15 V was at the rear, at the same end of the engine as the intake. The engine drove the load through a pulley or gear at the flywheel end, drive thus being indirect. By contrast, the S-15 Vd had direct drive from the flywheel, with the exhaust stack at the crankshaft end of the unit. Both engines were equipped with tuned pipes. In 1988, 400 examples of a long-stroke 10 cc FRV glow-plug engine named the MOKI M-12 LS were produced. This Schnüerle-ported engine featured a rear exhaust stack and a twin ball-race crankshaft.

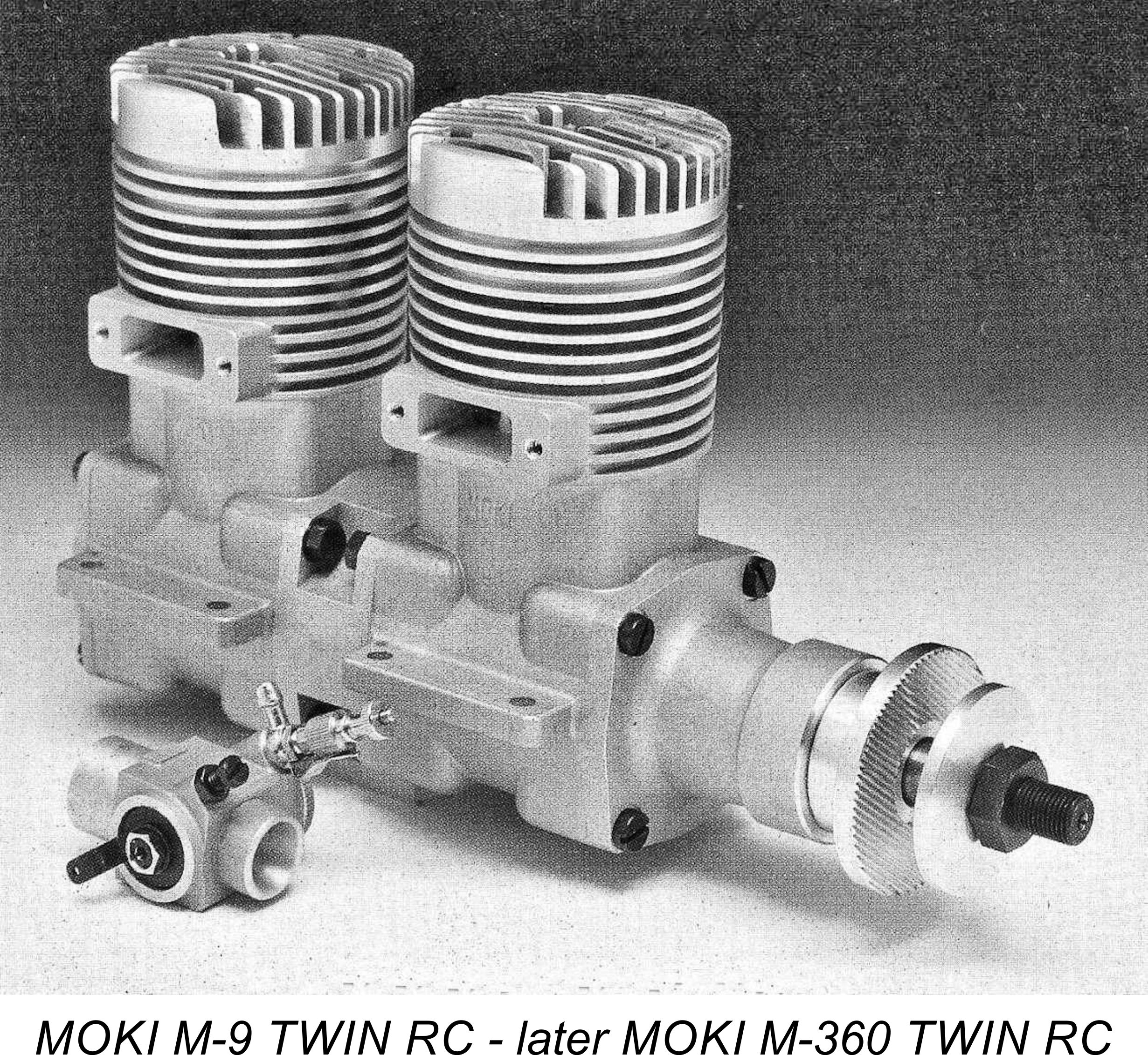

In 1988, 400 examples of a long-stroke 10 cc FRV glow-plug engine named the MOKI M-12 LS were produced. This Schnüerle-ported engine featured a rear exhaust stack and a twin ball-race crankshaft. In 1989, the MOKI workshops produced 300 examples of a 60 cc in-line twin-cylinder glow-plug engine called the MOKI M-9 TWIN RC. The components of the MOKI M-9 m RC engine were used for this production. Later the designation was changed to the MOKI M-360 TWIN RC. A version of this engine with electronic spark ignition was sold at a later date.

In 1989, the MOKI workshops produced 300 examples of a 60 cc in-line twin-cylinder glow-plug engine called the MOKI M-9 TWIN RC. The components of the MOKI M-9 m RC engine were used for this production. Later the designation was changed to the MOKI M-360 TWIN RC. A version of this engine with electronic spark ignition was sold at a later date. Also in 1989, MOKI produced 200 examples of a 2.5 cc glow-plug engine expressly designed for use in F2D control-line combat models under the designation MOKI C-1. This motor was basically a tuned-up version of the previously-mentioned MOKI Sport 1 engine, which had first appeared in 1975.

Also in 1989, MOKI produced 200 examples of a 2.5 cc glow-plug engine expressly designed for use in F2D control-line combat models under the designation MOKI C-1. This motor was basically a tuned-up version of the previously-mentioned MOKI Sport 1 engine, which had first appeared in 1975.

At the change of regime, the MHSz was liquidated without a legal successor. Its MOKI property passed to the Hungarian Model Association, which directed the further activities of MOKI. In the new capitalist era, no further assistance was forthcoming from the State - the venture had to survive on its own. Accordingly, the Institute was converted into a commercial business under the name MOKI Ltd., with Dezső Orsovai becoming the managing director. German and American businessmen were involved with the business for a time as well.

At the change of regime, the MHSz was liquidated without a legal successor. Its MOKI property passed to the Hungarian Model Association, which directed the further activities of MOKI. In the new capitalist era, no further assistance was forthcoming from the State - the venture had to survive on its own. Accordingly, the Institute was converted into a commercial business under the name MOKI Ltd., with Dezső Orsovai becoming the managing director. German and American businessmen were involved with the business for a time as well. Despite these problems, the "real" MOKI carried on. In 1994, the MOKI M-210 RC engine was produced in relatively small numbers, mainly for export to the USA, where very large R/C models were attracting an ever-increasing amount of attention. This FRV glow-plug engine had a displacement of 35 cc. The production of such large engines in small numbers is not efficient – it is very difficult to detect an economic incentive. I

Despite these problems, the "real" MOKI carried on. In 1994, the MOKI M-210 RC engine was produced in relatively small numbers, mainly for export to the USA, where very large R/C models were attracting an ever-increasing amount of attention. This FRV glow-plug engine had a displacement of 35 cc. The production of such large engines in small numbers is not efficient – it is very difficult to detect an economic incentive. I In 2008, production began of a 23 cc model in both glow-plug and spark ignition versions. The main version was the glow-plug model designated as the MOKI M-140 RC, while the spark ignition variety was termed the MOKI G-140 RC. The main components of both engines were the same as those of the MOKI M-150 RC engine (originally the MOKI M-9 RC) apart from the bore being smaller.

In 2008, production began of a 23 cc model in both glow-plug and spark ignition versions. The main version was the glow-plug model designated as the MOKI M-140 RC, while the spark ignition variety was termed the MOKI G-140 RC. The main components of both engines were the same as those of the MOKI M-150 RC engine (originally the MOKI M-9 RC) apart from the bore being smaller.