|

|

The J.B. Engines

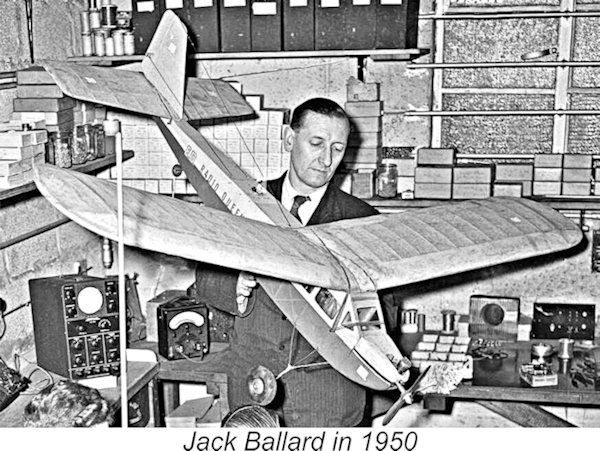

All of this is a great pity, because the engines were very capably designed in many respects, also being extremely well finished and enticingly packaged. Despite their failure to establish themselves in the British marketplace, the manufacturers undeniably showed themselves to be well capable both of producing model engines of real quality and marketing them effectively. The letters of the engines’ trade-name stand for the initials of their instigator, Jack Ballard. Let’s begin by taking a look at the somewhat convoluted background to the introduction of this rather ephemeral range. Background John Edward Ballard was born in November 1904 at Kensington, Greater London. Although his given name was John, he always referred to himself as Jack, which is the name by which he is generally remembered. His grandson John Foster recalled him as having a charming personality, but also as having a tendency to react very forcefully to any disagreement with his own views. He apparently held very strongly Conservative opinions, having a particular antipathy towards trade unions. His views led him to regard John Foster's left-of-centre political opinions very unfavorably! As a result, the two did not get on very well. John Foster's father referred to Ballard's approach to business as ethically questionable, while his elder sister characterized her grandfather as a poor businessman but a very capable salesman. Information regarding Jack Ballard's life and activities prior to WW2 is scanty in the extreme. The 1921 census recorded him as living at home with his parents and younger siblings at 18 Wellington Road, Hampton, Teddington, Surrey, England. An interesting observation is that his father’s full name was also John Edward Ballard. In the 1921 census he was listed as a "glass cutter". This suggests that Ballard had a relatively modest family background. Young John Ballard was correctly stated in this census to be 16 years old, indicating that he had just left school. He was listed as an Electrical Engineer working for the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) at Teddington. An article about the E.D. factory which appeared in the April 1951 issue of "Model Aircraft" stated that Ballard worked at NPL for nine years, being involved in "development work and model experimentation". It’s clear that at age 16 Ballard couldn’t have been legally qualified as a Professional Engineer, which then as now required a formal University or Technical College education. His identification as an “Electrical Engineer” in the census was almost certainly a self-characterization to inflate his status – even at this early age he seems to have held a very high opinion of himself! It actually appears that upon leaving school at 15 he immediately entered the workforce, never proceeding to higher education. Certainly, he never attached any indications of professional qualifications to his name in later years. Ballard spent the WW2 period working in Kingston-upon-Thames as a detail fitter for the Parnall Aircraft Company at their former Nash & Thompson premises. At the war's end, Ballard and many of his fellow employees were made redundant. A number of them joined forces to establish the Electronic Developments (E.D.) company in 1946, with the 42 year old Jack Ballard serving as the company's founding Managing Director. He represented E.D. on the sub-committee set up by the Model Trader’s Association in 1949 to fight the Government decision to impose Purchase Tax on model engines. Their efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, with a late 1950 court ruling confirming the imposition of purchase tax on model engines beginning retroactively in 1949.

It’s possible that some of the other directors may have held Ballard partially responsible for this unhappy situation. Certainly, it appears from reading between the lines that the E.D. management team was rather shaken by dissention during the early 1950’s. One point on which the Board as a whole seems to have disagreed with Ballard was his perception of the need to continue both to update and expand the company’s range and to improve the presentation and marketing of its products. It also seems possible that some aspects of his seemingly forceful and self-assured personal characteristics may have rubbed his fellow Directors the wrong way. While the need to upgrade the company's products and their presentation was likely a valid viewpoint, it was an inescapable fact that the full implementation of such a broad program would require a significant investment of financial resources which the company simply did not have at the time. The loss of the purchase tax argument coupled with E.D.’s failure to make provision for an unfavourable outcome had placed the company in a position in which its financial capabilities were extremely strained. This led to its development programs being under-funded for some time.

Ballard was soon followed by engine designer Basil Miles, who had never been an actual E.D. Director or employee, serving as E.D.'s chief engine designer on some kind of contractual or royalty basis. There were stories going the rounds at the time to the effect that Miles was involved in a personal issue which led to E.D. management deciding that it was necessary for them to sever all official ties with him. Probably best forgotten ................ Whatever the truth of the matter, the severance appears to have been relatively amicable under the surface - Miles continued to design and build engines on his own. One of these designs was actually marketed by E.D. as the 5 cc Miles Special in both diesel and glow-plug forms. Miles also appears to have retained some form of arms-length albeit unpublicized design consultancy with E.D. which lasted until around 1958. Both this ongoing relationship and the quality of Miles' designs confirm that the official parting of the ways was undoubtedly for reasons other than any shortcomings in Miles’ engineering capabilities. I suspect that this matter must have exacerbated existing tensions within the ranks of the E.D. directorate. The next key individual to depart was E.D.’s original radio control guru George Honnest-Redlich, who left to form his own company called Radio & Electronic Products located initially in nearby Mortlake. His company's Reptone radio control gear was very highly regarded. He reportedly became a pioneer in the development of remote-controlled garage door openers! One by one, E.D.'s Old Guard was moving on ...........

However, there was a problem despite the commercial success of these products. Model engine manufacture formed only a relatively small segment of the Anchor Motor Company's business portfolio, to the point that it was actually little more than a sideline undertaken more as a labor of love than anything else. Moreover, the profitability of this aspect of the company's business had become increasingly marginalized by the loss of the Purchase Tax case in late 1950. To compound these issues, as of 1951 the company had become heavily involved in Government contract work, greatly compromising its ability to devote resources to model engine development and manufacture. By April 1952, things had reached a point where model engine production had to be suspended altogether in favour of the far more lucrative Government work.

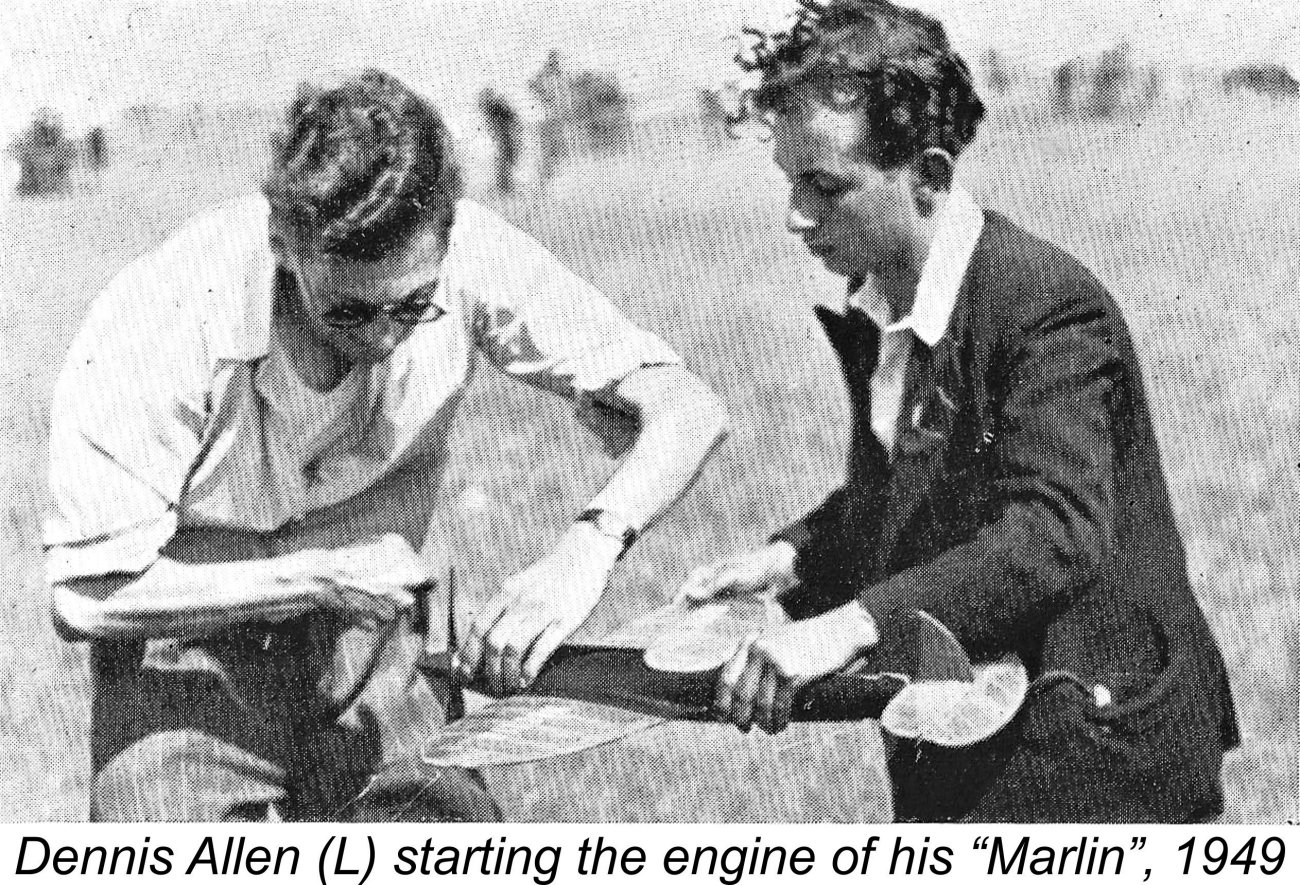

The initial announcement of the take-over appeared in an advertisement which was placed by the new owners in the October 1952 issue of “Model Aircraft”. This announcement included the information that production of the highly-regarded AMCO 3.5 BB would re-commence “shortly”. An identically-worded announcement appeared in the November 1952 issue of the rival “Aeromodeller” magazine. The name of the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. unmistakably suggested a concern with electronics in addition to model engines. This was of course an exact parallel to the business portfolio of the competing E.D. company, which manufactured both engines and radio control equipment. In addition to resuming the production of certain AMCO model engines, the new company also entered the radio control business with its Avionic range of R/C gear. After the AMCO range was taken over by Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering in the latter part of 1952, there was a hiatus in model engine production while the required manufacturing facilities were established at the new location. The company wisely retained Dennis Allen to assist them in getting set up to resume production of the flagship 3.5 cc models.

In addition, Allen had worked as one of the engine repair wizards at Henry J. Nicholl’s famous shop at 308 Holloway Road in London during the period when Nicholls’ Mercury Models division was acting as the trade distributor and service centre for the AMCO engines. He therefore had the opportunity to get to know the original AMCO range very well indeed. Allen had subsequently worked in the model engine field with Alan Allbon, hence bringing a wealth of directly related experience to his new position. Allen's hand was soon greatly strengthened by the addition of his good friend and fellow West Essex club member Len "Stoo" Steward to the staff of the new company. Steward had previously owned the "K" Model Engineering Co. of Gravesend in Kent, hence having a wealth of hands-on model engine manufacturing experience in connection with the various "K" model engines. He was particularly noted for his skill in honing cylinders and lapping pistons to fit. Another notable individual with a proven track record as a model engine designer and constructor who joined the company at this time was Arthur F. Weaver, best remembered today as having designed the delightful Weaver 1 cc sideport diesel for home construction. Weaver was a noted exponent of model car and tethered hydroplane racing, having designed and built a number of his own engines. He was a skilled and highly experienced toolmaker who doubtless contributed a great deal to the further development of the company's design and manufacturing programs. Engineering talent was certainly not lacking at Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering!!

It’s perhaps worth noting here in passing that Warring’s test report gives the name of the new makers as “Aeronautical & Electronic Engineering Co.” This is incorrect – the “&” is where I’ve consistently placed it elsewhere, as confirmed on the boxes. It took a little longer for the AMCO 3.5 PB to re-enter production - as far as I’m presently aware, the initial advertisements for this re-introduced model appeared in June 1953. The engine incorporated a few well-considered modifications to Ted Martin's original Anchor Motor Company design. Dennis Allen was doubtless responsible for these improvements. However, it remained basically the same unit - just a little more durable.

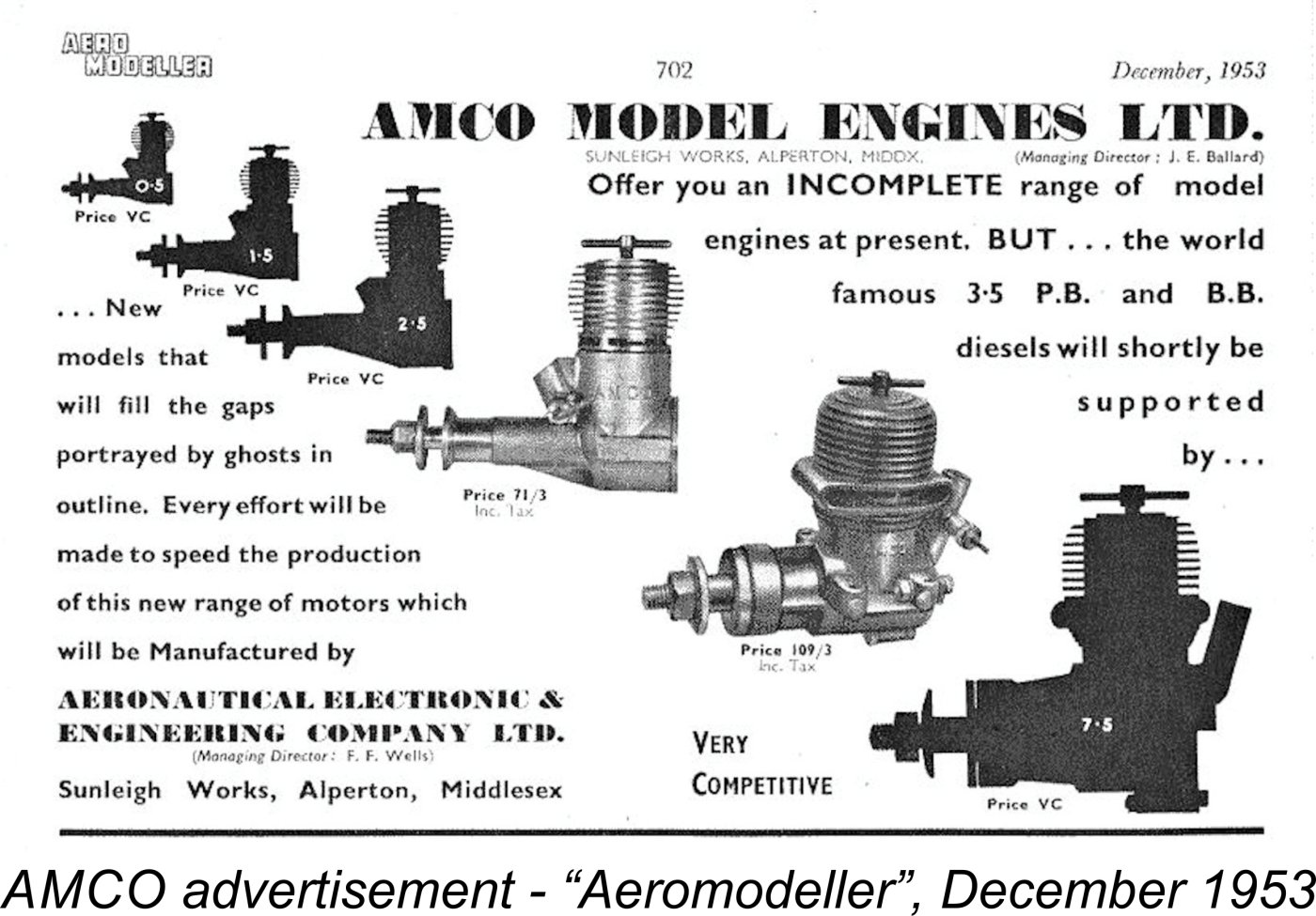

Ballard’s arrival at Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. in mid 1953 came some time after production of the AMCO 3.5 BB had resumed and more or less concurrently with the re-introduction of the AMCO 3.5 PB. Accordingly, Ballard had little or nothing to do with either re-introduction, both of which which were implemented or at least set in motion prior to his arrival. At this point, a corporate reorganization took place which seems to shed considerable light upon Ballard's character. Having been a Managing Director at E.D. for some 7 years, Ballard was evidently unwilling to accept what he would have seen as a "demotion" from a parallel position with his new employer. However, F. F. Wells was equally (and understandably) unwilling to step down from his position as Managing Director of the company which he had worked hard to establish before Ballard came on the scene. The impasse which this situation potentially represented was resolved through the division of the company into two distinct entities. Both the engines and the Avionic radio control gear continued to be manufactured by Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co., which was still led by F. F. Wells as Managing Director. However, a separate entity known as AMCO Model Engines Ltd. was now established to market the engines, with Jack Ballard in the position of Managing Director. The true nature of this split was underscored by the fact that the two companies both remained at the same address - Sunleigh Works, Alperton, Middlesex. It's clear that in reality the split was only on paper - all of its business activities remained under one roof. This reorganization of the company seems to me to imply a certain element of self-centredness and self-importance on Ballard's part - his joining the company was evidently conditional upon his being immediately placed in a managerial position which preserved the status which he had achieved with E.D. If the company had to be split to achieve this, so be it ..............one wonders what Ballard brought to the venture that constituted a sufficient inducement to persuade Wells to agree to his terms.

The proposed new models included shaft valve units in the .55 cc, 1.5 cc and 2.5 cc displacement categories. Their advertising profiles suggested that these models were to be based to a significant degree upon the design of the AMCO 3.5 PB. There was also a 7.5 cc version of the disc rear rotary valve (RRV) 3.5 BB model. A 5 cc RRV model was later added to this "phantom" lineup. However, none of these models appear to have reached the series production stage, and I am presently unaware of any surviving examples of any of them other than a few prototypes of a somewhat re-designed 1.5 cc model, of which more anon. At this stage, Dennis Allen was still involved with the technical side of Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering's model engine development and manufacturing programs. While working on the various design improvements which are reflected in the later versions of the AMCO 3.5 PB, Allen had not confined his attention to the AMCO models - in his spare time he had been working with his good friend Len Steward to develop a design for a new lightweight 2.35 cc plain bearing diesel which he believed to have considerable commercial potential. According to an unattributed article about the Allen-Mercury (A-M) enterprise which appeared in the June 1958 issue of “Model Aircraft”, Allen offered this design to his employers, who were not interested. He reportedly also offered the design to E.D., who likewise declined. These rejections had far-reaching consequences for all concerned, since Allen’s unswerving belief in his new design led him to seek other avenues for getting it into production. Over the years since he had worked for Henry J. Nicholls, Allen had maintained his close personal ties with Nicholls and Mercury Models. In the first half of 1954 this association resulted in Allen’s departure from Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. to commence independent model engine manufacture in cooperation with Nicholls under the Allen-Mercury (A-M) banner. Len Steward also left Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. at the same time to become closely involved in Allen's new venture on the technical side, while Nicholls presumably assisted with start-up funding. Ballard's associated company thus lost two of its most capable and experienced model engine experts at one stroke.

As it was, the new model was manufactured by Allen’s own company, D. J. Allen Engineering of Edmonton in North London and was marketed by Mercury Models, hence the name. A significant case of opportunity lost as far as Jack Ballard was concerned ………… The very over-square bore and stroke of the AMCO 3.5 must surely have influenced Allen when designing the later 3.5 cc A-M 35 (released in 1955), since he adopted exactly the same bore and stroke for that engine. So despite its different porting system, the AMCO 3.5 PB may thus quite legitimately be seen as very much the “parent” or prototype of the A-M 35. I love connections ……….

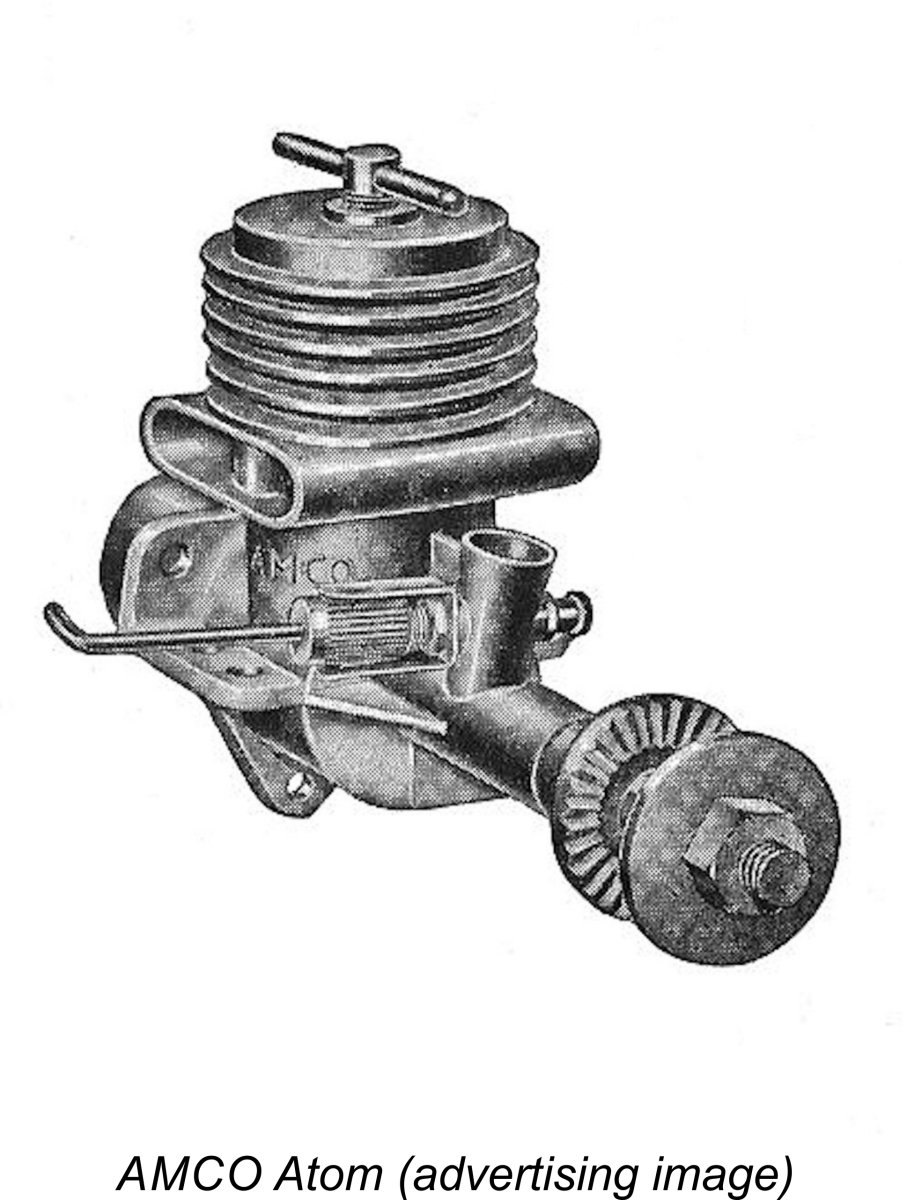

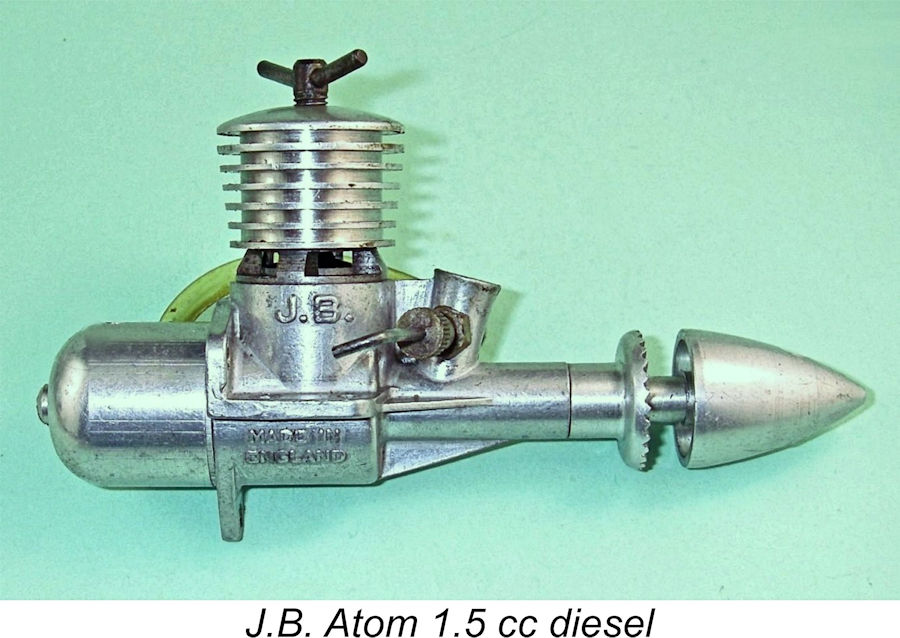

Presumably as a consequence, AMCO production appears to have sputtered thereafter, finally ending altogether in early 1955 - the last advertisement for the AMCO engines of which I’m presently aware appeared in February of that year. Oddly, this final advertisement announced the release of a new version of the 3.5 BB with removable exhaust stacks! Little more was heard of this ultra-rare variant, of which only a few examples exist today to prove that it did at least reach the production stage. Now we get to the heart of the matter! In April 1954, AMCO Model Engines Ltd. had announced a new 1.5 cc AMCO engine called the Atom, which had presumably been conceptually developed by Dennis Allen prior to his departure at around that time. Jack Ballard seems to have made a practise of issuing premature announcements, and this one was no exception - as of October 1954 we find him apologising for the delay in getting the Atom out to the model shops! This apology was repeated in December of 1954. It seems highly likely that Allen’s and Steward's earlier departures had a great deal to do with this ………. A few examples of the AMCO Atom were undoubtedly made before AMCO production ceased in March of 1955, since one or two are known to exist today in private collections. Still, this remains undoubtedly the rarest AMCO model of them all. However, the 1.5 cc Atom design did not die as a result of the cessation of AMCO production! It was destined to resurface in October 1955, albeit then produced by a totally different manufacturer. Enter J.B.

This decision was likely prompted by the ongoing production problems with the other AMCO models, including the 1.5 cc Atom which had been prematurely announced by Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. and AMCO Model Engines Ltd. the better part of a year earlier in April 1954. Ballard may have felt (with some justification) that the existing companies had squandered too much of their credibility by this time, making a name change imperative. However, he was evidently reluctant to abandon the development work which had gone into the Atom.

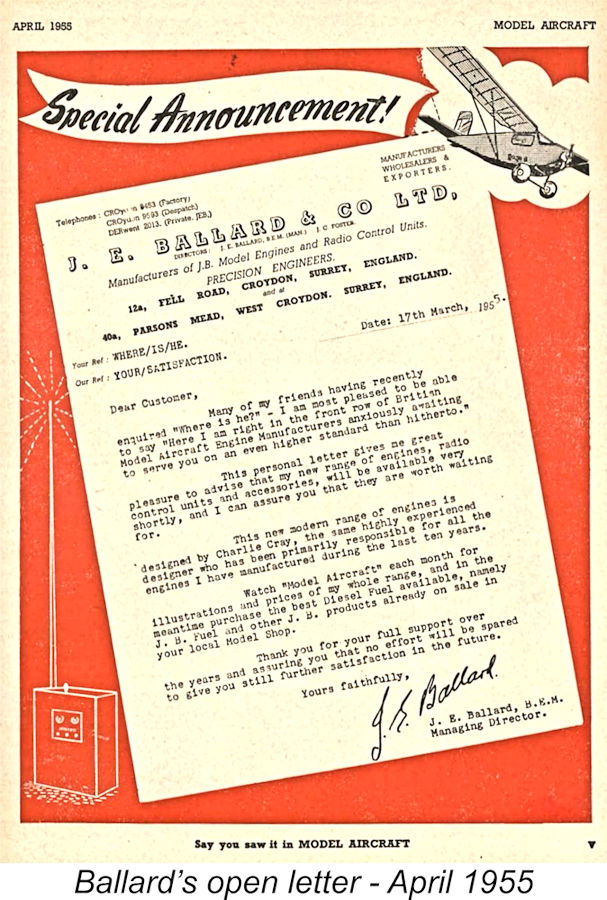

The April 1955 advertisement actually took the form of an open letter dated March 17th, 1955 to prospective customers. It’s interesting to note Ballard’s comment in this letter that the designer of his forthcoming new line of engines was Charlie Cray, “the same highly experienced designer primarily responsible for all the engines manufactured by me (Ballard) during the past ten years”. I’m sure that Basil Miles of E.D. Racer fame, AMCO designer Ted Martin and Martin's successor Dennis Allen would all have been extremely surprised to read this……………although Charlie Cray had undoubtedly been involved in the design of the early E.D. "stovepipe" models marketed during the early stages of Ballard's tenure at E.D. - the Mk. II, Comp Special and Mk. III.

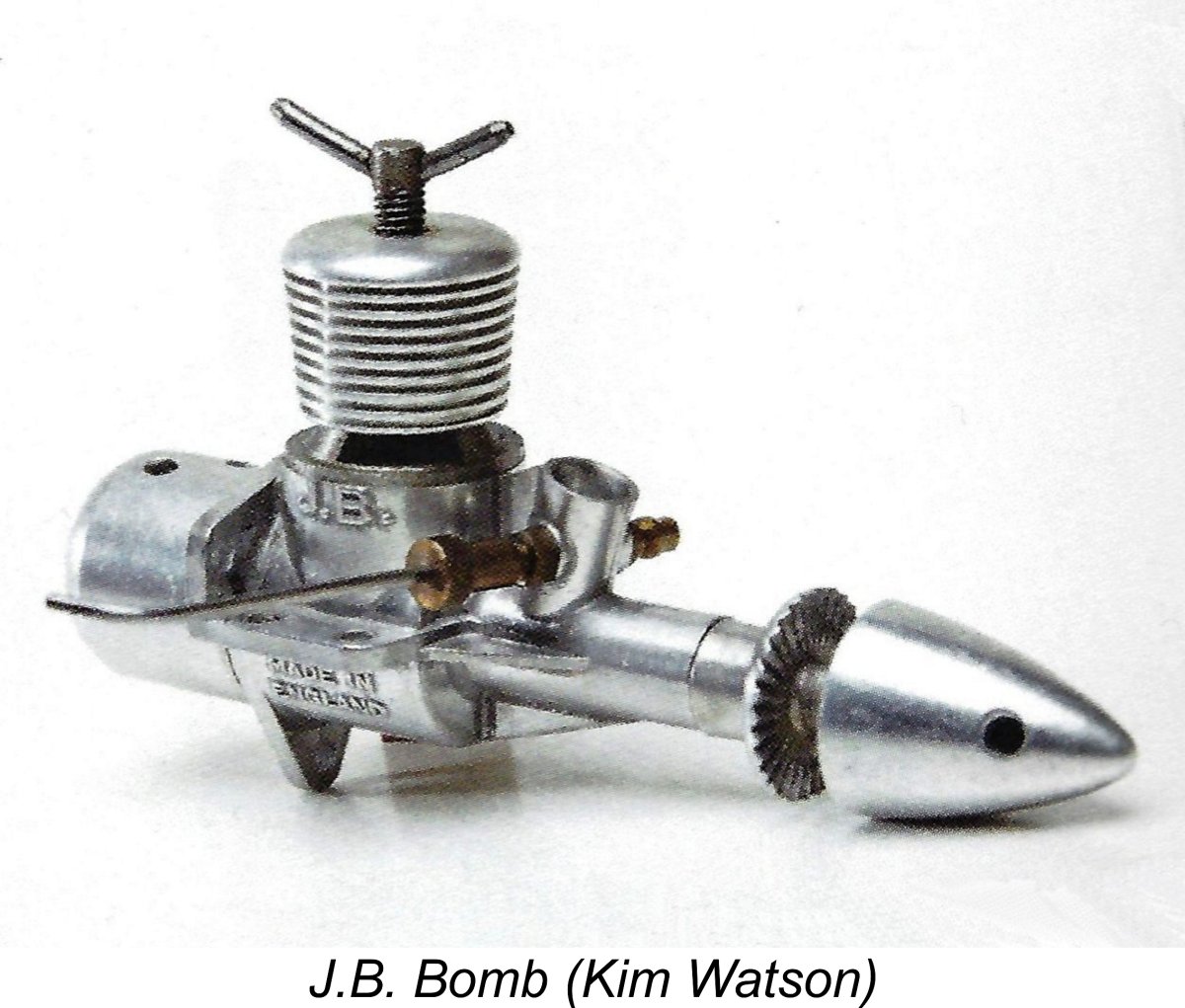

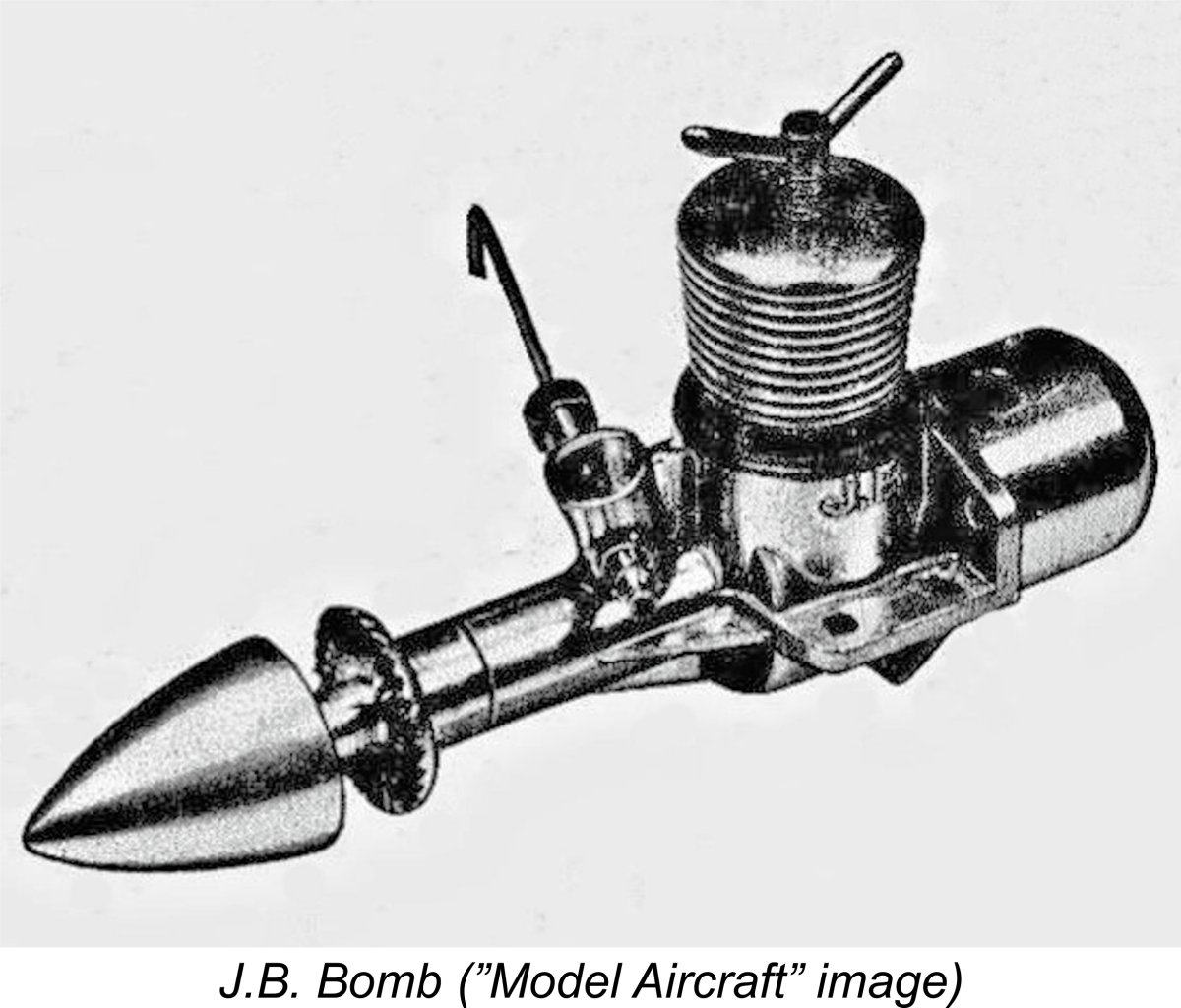

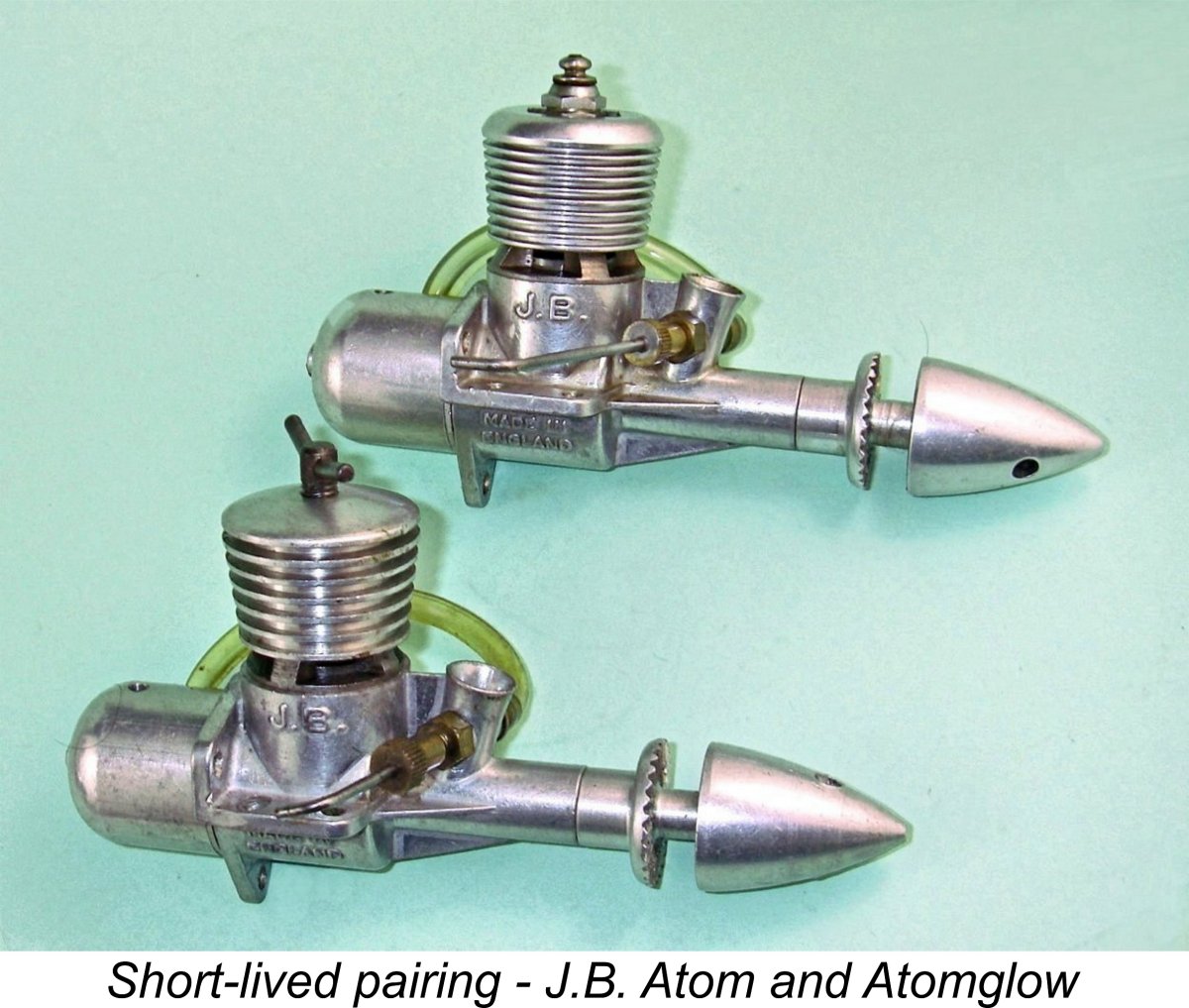

My valued friend and fellow researcher Marcus Tidmarsh was able to clarify this point. He was able to confirm that John Edward Ballard was indeed awarded the British Empire Medal on June 15th, 1945 for "work which had greatly benefited the British Empire while employed as a detail fitter at Parnall Aircraft Ltd." It appears likely that he had come up with an idea which significantly improved either the production efficiency or the functioning of his employer's products, most likely the aerial gun turrets which they manufactured. Ballard's contribution must have been seen as quite significant, because the British Empire Medal is conferred relatively seldom, and then only for truly noteworthy contributions - only 130 of them have been awarded since the honor was first established during WW1. Clearly, the award to Ballard was indicative of a very high perceived value of his contribution, whatever it was. Unfortunately, the conferring of the award may have contributed to an enhancement of his abilities in his own opinion as opposed to that of others, reinforcing an unfortunate personal trait which eventually led to his downfall, as we shall see. An even more interesting observation is the fact that the letterhead names J. C. Foster as the sole Director apart from Ballard himself. John Foster advised that this was the married name of his mother Jaqueline Claudia Foster, née Ballard (Jack Ballard's only daughter), who was 22 years old in 1955 and had no business or technical credentials of any kind. It appears that her name was added to the company's Directors list purely to satisfy the legal requirement that a Limited Company actually have a Board of Directors with at least one Director in addition to the Managing Director. She may not even have been aware that she was so honored – J. E. Ballard & Co. Ltd. may have been in effect a one-man show of which his daughter had no knowledge!! If her name was indeed appropriated in this way, it would certainly explain why John Foster's dad held such a negative view of Jack Ballard's business practises! His wife would have acquired all of the legal exposure which is assumed by any Director without actually participating in the company's operation. Regardless, the first product of the new company was a line of model engine fuels sold under the J.B. banner. These were being advertised by July 1955. At this time, the new company had yet to release an engine under its own name, but this changed in October 1955 with the initial announcement of the company’s first model diesel, the J.B. Atom of 1.5 cc displacement. Ballard subsequently went on to produce both a glow-plug version of the J.B. Atom and a smaller 1 cc version called the J.B. Bomb in both diesel and glow-plug configurations. These three additional models were announced in April of 1956. Let’s take a look at these engines, focusing on their rather unhappy fate in the marketplace and the reasons underlying this outcome. The J.B. Atom and Bomb

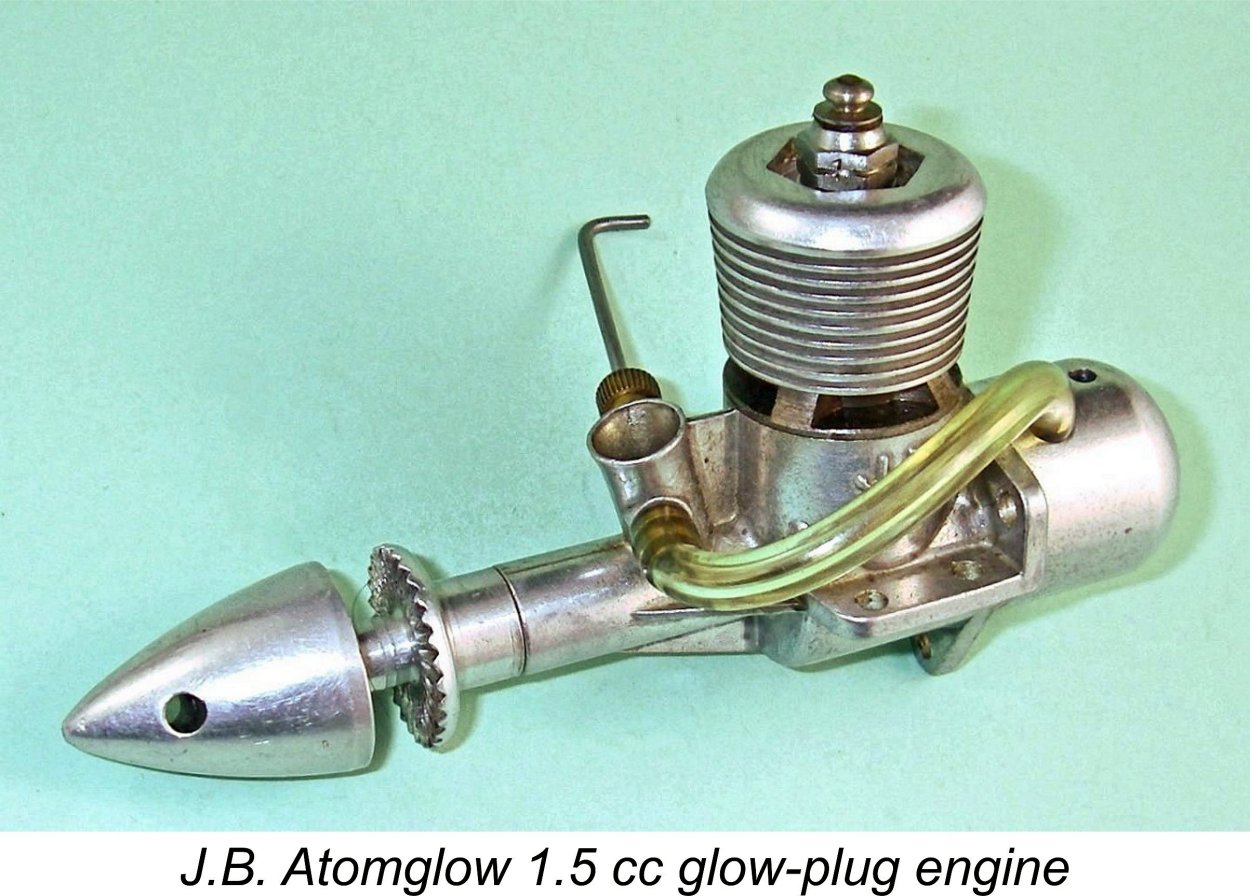

Peter Chinn confirmed this connection in a comment made in his “Accent on Power” column which appeared in the February 1956 issue of “Model Aircraft”. He had previously announced the arrival of the J.B. Atom on the market in his January 1956 column. In his follow-up article in February, Chinn mentioned the earlier still-born AMCO Atom model of 1954, commenting that the then recently-introduced J.B. Atom appeared to be essentially the same engine in a slightly revised form and under a new name. The J.B. Bomb which followed the Atom into the marketplace in April 1956 (see below) was in essence a smaller 1 cc version of the Atom, albeit exhibiting a number of quite significant design departures. I’ll cover those departures in the subsequent section of this article which deals with the published tests of the J.B. engines. The styling, finish, packaging and presentation of the engines were trend-setting for an English production – very much along American lines. This fact supports the previously-voiced notion that Ballard may well have been arguing for a similar approach on the part of E.D. prior to his leaving that company. Both models were basically conventional radially-ported plain bearing FRV diesels of their era. They were built to very good standards, also being unusually well finished in a clearly American-influenced style. The J.B. Atom was Exhaust porting consisted of four rectangular openings of generous dimensions spaced evenly around the circumference of the hardened steel cylinder. Four transfer ports were drilled through the cylinder wall between the exhausts at a 45 degree angle. The transfers overlapped the exhaust almost completely. The transfer ports were supplied with mixture by four bypass flutes cut into the outer cylinder wall. These bypass flutes necessarily interrupted the male cylinder installation thread. There's a bit of a mystery surrounding the engine's cylinder port timing. The generally reliable Peter Chinn stated that the exhaust ports of his tested example opened very early for a generous exhaust period of "over 150 degrees", with the transfers lagging only very slightly behind. All I can I can't explain the discrepancy between Chinn's reported timing figures and my own directly-measured numbers - I can only report it. The one possible explanation that I can think of is that a design change may have been made after Chinn's presumably early example had been manufactured. We know that the gudgeon (wrist) pin carrier retention system was changed (see below), so it is entirely possible that the port timing was altered as well. Another noteworthy feature of the Atom was the fact that the generously-dimensioned gudgeon (wrist) pin was mounted in an aluminium alloy yoke which fitted into the interior of the hardened steel piston, thus trapping the pin entirely within the unbroken piston walls. In the earlier examples, the carrier was retained by a circlip, while later examples featured a carrier which was threaded into the working piston “shell”. This made the replacement of the gudgeon pin and conrod a bit of a chore. The required approach is detailed in a separate article by Dave Causer to be found elsewhere on this website. The conrod was of hardened steel with a relatively short small end bearing. Rods of this material have a well-documented tendency to generate excessive wear on both the gudgeon pin and crankpin bearings, especially if those bearings are short. The use of an ultra-short stroke would exacerbate this effect by increasing the working loads imposed upon the conrod by gas pressure acting upon the larger piston area. An alloy rod would undoubtedly have been a better choice. The crankdisc was counterbalanced, which worked in concert with the very light piston and short stroke to minimize the engine’s potential for vibration. The main crankshaft journal was of generous length, a good feature in terms of shaft stability. It ran in a plain bearing formed in the crankcase material. However, the shafts tended to be fitted considerably more tightly than desirable. This was to prove problematic in service, as we shall see.

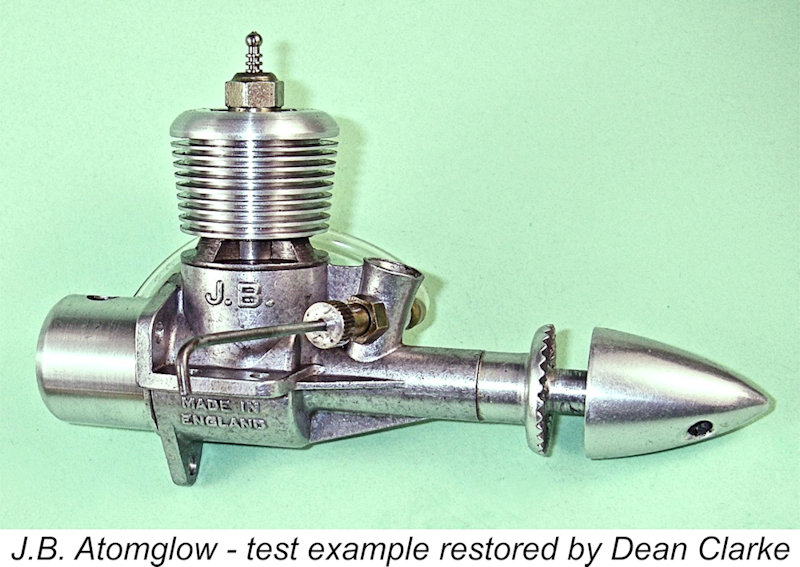

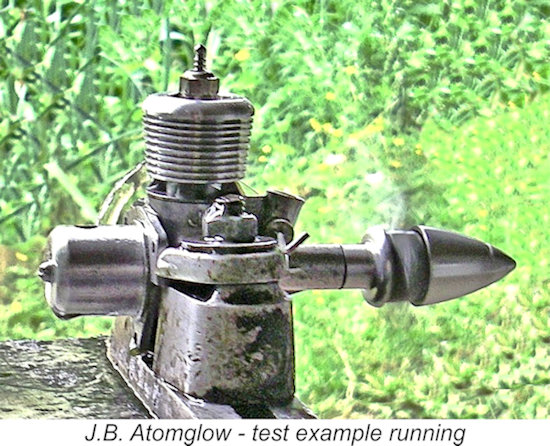

Both the Atom and the Bomb were also offered in glow-plug configuration. I don’t have an example of the J.B. Bombglow model, but I do have a very nice all-original example of the Atomglow. The construction of this model is essentially identical to that of the equivalent diesel version apart from the replacement of the contra-piston with a screw-on cylinder head which was centrally drilled and tapped to accommodate a long-reach glow-plug. Readers of my separate article on compression ratio measurement may recall that I determined the compression ratio of this example of the Atomglow to be a somewhat marginal 7:1. A "hot" plug together with a healthy dose of nitromethane both seem to be implied............. see below for some test impressions of the Atomglow. The Involvement of Charlie Cray As mentioned earlier, Ballard credited the design of the J.B. engines to a chap named Charlie Cray. The J.B. ads refer to Charlie as “England’s most experienced engine designer”, also implicitly crediting him with the design of many of the E.D. models developed during Ballard’s tenure at that company. There’s a reference in several of the ads to Charlie having been written up in the April 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft” magazine, but I've searched that issue from cover to cover looking for any such reference, without success. The only reference to Charlie Cray is that included in the previously-cited introductory J.B. advertisement in that issue. Hardly counts as a write-up!

Interestingly enough, a search of E.D. corporate records by my valued friend and colleague Kevin Richards has revealed that Miles appears never to have held any official position within the E.D. company at any time, either as a Director or as an employee in a managerial or technical capacity. It seems likely that his role was always that of a design consultant. Furthermore, the first E.D. model engine design to which Miles’ name was officially attached was the E.D. Mk. III Racer of March 1951. Prior to that, it appears that he had at least an advisory role in the 1949 design of the 3.46 cc E.D. Mk. IV, with which he is pictured in the attached illustration. Based upon some later comments made to friends and associates, Miles himself certainly viewed the Mk. IV as his design. However, the E.D. engines produced prior to 1949 display little architectural evidence of any design involvement on Miles’ part when compared with his own known productions from that era. Those early models were doubtless attributable to Charlie Cray, at least in part. So Cray did indeed have a fair helping of model engine design experience, just as claimed by Jack Ballard. However, it can't be denied that he rather dropped the ball when designing the J.B. engines! But in some rather unexpected ways ………and perhaps he had help!! Ron Warring’s test published in the April 1956 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine sets out the story very comprehensively. The engines were intentionally set up very tight to ensure “good compression” and ”tight bearings” - those fallacious tests of an engine’s worth in the eyes of the uninformed. This may have been a manufacturing criterion which was imposed upon Charlie by Jack Ballard ............ Even so, this might have been OK with an appropriate material specification. However, the company chose to use hardened steel working components throughout! I have to say that Charlie Cray is the prime suspect here ........he was probably influenced at least in part by his previous use of hardened steel conrods in the early E.D. models for which he had been at least partially responsible. In particular, the choice of hardened steel for both the piston and cylinder of the J.B. engines meant that no amount of running-in would relieve the piston/cylinder fit in the normal way. As previously mentioned, the fit of the main bearing was also tight to the point that “hot spots” often developed, and the very long bearing used meant that this would take tens of hours to free up. The use of a steel conrod with an unsupported and hence “wandering” small end also created undue wear on the crankpin and gudgeon pin, with inevitable consequences as far as engine life went – the rod and its bearing pins were shot long before the piston was even close to freeing up! By insisting on working to ultra-tight fits and also using hardened components throughout, the manufacturers created an engine that suffered from excessive friction and would never free up properly. This inevitably prevented the poor old Atom from ever developing the power that the design could have produced. They also used a rod assembly that would wear out very rapidly, long before the rest of the engine was even broken in properly.

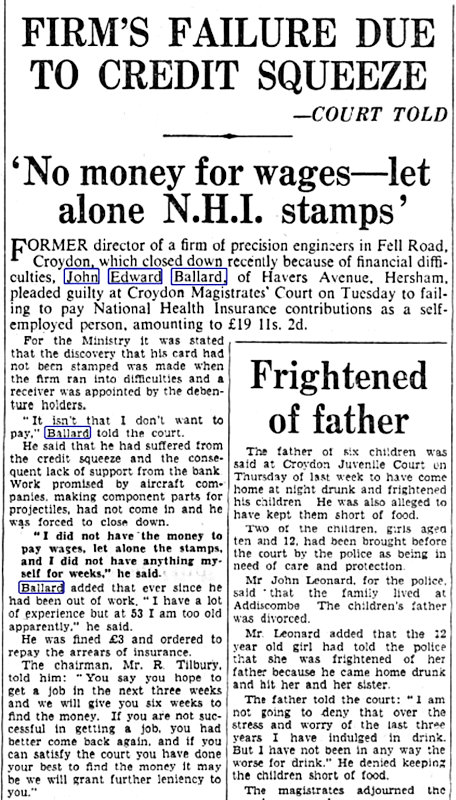

As it was, Peter Chinn’s test of the Atom in the February 1956 issue of “Model Aircraft” in effect damned the engine with faint praise, especially in performance terms, while Ron Warring's more openly negative test report on the Atom in the April 1956 issue of “Aeromodeller” (unfortunately coinciding with the expansion of the range) probably settled the issue. See below for further discussion of these tests. The company continued its promotional efforts throughout the balance of 1956. However, their efforts both at home and abroad evidently failed to achieve sufficient sales success to justify continued production. The actual manufacture of the J.B. engines appears to have been terminated around the end of 1956 - the last J.B. advertisement that I’ve been able to find (seen at the left) appeared in the January 1957 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Characteristically, even at this point Ballard was still promising the appearance of "new radio relays and engines", none of which ever appeared. A sad end to a worthy effort having great potential.......... My good mate Gordon Beeby undertook a search for J.B. advertisements which confirmed that the engines did reach at least a few overseas markets. Gordon found that they were advertised in "Aeromodeller" Gordon also found irrefutable evidence to prove that the company made efforts to penetrate the American market with their glow-plug models. During the latter half of 1956 their advertising began to invite inquires to an entity called J&B Corporation of 112 Myrtle Avenue, Brooklyn, New York. Presumably they were hoping that the American styling and packaging of the engines might attract attention in the USA. This company did get as far as placing the advertisement seen at the right in the June - October 1957 issues of "Model Airplane News" (MAN). It's worth recalling that this was some months after the appearance of the final advertisement in the British modelling media - manufacture had undoubtedly ceased by this time. This was a clear case of trying to liquidate unsold inventory on the American market. Even more unexpectedly, Gordon found that the J.B. Atomglow was actually listed years later as a "sale" item by America's Hobby Center (AHC) of New York. These ads ran in various American magazines from January through August 1963, some 6 years after manufacture had ceased! Presumably these engines were New Old Stock obtained on the cheap by AHC from the residue of the former J&B Corporation operation in Brooklyn. So what became of Jack Ballard, I hear some of you ask? Since I've always seen the human interest stories associated with model engines to be just as fascinating as the model engines themselves, I was as keen as anyone to know the answer to that question. Unfortunately, nothing was known of Jack Ballard's subsequent activities until May 2025, when I was delighted to hear from his grandson, John Foster, who had just read my articles on his grandfather's various companies, incuding this one. John commented that all that I'd written about Jack Ballard appeared to fit the man that John remembered, warts and all. He provided some very useful information on Jack Ballard's later years, to which which my valued friend and fellow researcher Marcus Tidmarsh was able to add a great deal of facinating detail through his painstaking in-depth research into Jack Ballard's business activities. For completeness of the record, I'll summarize this information here, with my sincere thanks to John and Marcus for making this possible. Jack Ballard - the Later Years There appear to have been several underlying reasons for the failure of J. E. Ballard & Co. One of those reasons may actually have related to his patently false public claim that Charlie Cray had designed “all of the engines manufactured by (Ballard) during the last ten years”, which doubtless rubbed a few people the wrong way, and for good reason. His seemingly forceful and self-centred approach to his involvement in business may also have given rise to a measure of inter-personal friction. I suspect that even before he made the Charlie Cray claim, pretty much everyone in the trade was already looking at him somewhat askance given his shaky track record, and this was the final straw – a lot of people in the trade probably decided to have as little to do with him as they could. It appears that Ballard's own character may have told against him in other ways. He seems to have been a person who held an unwarrantably high opinion of his own business abilities. This led him into making a series of trade announcements and business commitments which he proved unable to honor. It's a wise man who knows his own limits and conducts himself within those limits - Jack Ballard doesn't appear to have been such an individual. However, the over-riding issue was undoubtedly the fact that the J.B. engines were quickly revealed to be woefully sub-standard performers. This almost certainly resulted in the cancellation of anticipated orders from distributors and retailers. Ballard had evidently been counting on receiving plenty of large orders for his attractively styled and innovatively packaged products to establish a cash flow for his new company. The failure of sufficient orders to materialize would have left him with an increasingly serious cash flow shortfall and a burgeoning debt load. Moreover, the lack of orders would have left him with highly limited options for selling his engines, causing a progressive inventory build-up. Understandably, the banks were unwilling to underwrite further operations under these circumstances. By mid 1956 Ballard’s company was really struggling, facing a serious cash flow shortfall. There was a clear need to upgrade the company's products, but the cash flow was insufficient to support the development of the required improvements. Marcus Tidmarsh confirmed that in order to secure some necessary working capital, Ballard took out a £2,000 loan from a company called New British Garden Estates Ltd. As collateral, he offered "Leasehold land with buildings and garages erected in part thereof situated between Fell Road and Park Lane, Croydon, Surrey" - presumably the site of the J.B. manufacturing facilities. J. E. Ballard & Co. Ltd. received these funds on July 20th, 1956. This loan only delayed the inevitable – in fact, it probably made things worse by increasing Ballard’s debt load while unwarrantably extending the life of a failed company. The continuing lack of orders soon forced a cessation of production, almost certainly by late 1956 - the record shows that J. E. Ballard & Co. had ceased advertising in the model engine field by early 1957, although Ballard was evidently still making efforts to liquidate previously-manufactured assets. At this point, his workforce would have been laid off and were doubtless expecting to be paid out. There were other creditors in addition, most notably New British Garden Estates Ltd. Marcus Tidmarsh observed that in the normal course of events, Owner/Directors of companies were paid in the form of dividends derived from company profits. This form of payment imposed a far lower tax burden, also obviating the requirement to make National Health Insurance (N.H.I.) payments. However, in this case there were no profits and hence no dividends. The only way that Jack Ballard could legally take money out of the company was by doing so as a self-employed private contractor. But in this case, there was a legal requirement to make N.H.I. payments.

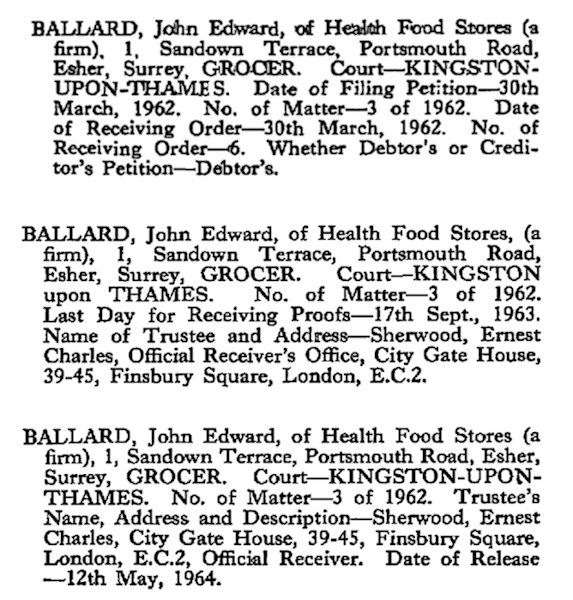

Of course, there were other creditors who were not being paid. Claims were made against the company, but Ballard was unable to meet them – he was too deeply in debt. Consequently, his creditors called in the official Receivers at some point in 1958. The Receivers quickly discovered Ballard’s failure to meet his legally-required personal N.H.I. obligations, accordingly determining that the situation had legal ramifications. Consequently, they informed the legal authorities, who took Ballard to court on a charge of failure to pay N.H.I. contributions as a self-employed person in accordance with legal requirements. His case came up in October 1958. Fortuitously, Marcus had preserved a scan of the summary of the court proceedings which was published in the October 31st, 1958 issue of the Croydon Advertiser newspaper. This summary is reproduced here at the left. The cited £19 11s 2d (£19.56) figure for the arrears may sound trivial to us, but in terms of purchasing power in 1958 it was equivalent to well over £1000 in today's currency. Although the media report did not name the company involved, it did name John Edward Ballard as the defendant, giving his age of 53 correctly. It also confirmed that the defendant’s former precision engineering company was located on Fell Road. This makes it absolutely clear that the company involved was indeed J. E. Ballard & Co. and the defendant was Jack Ballard personally. Ballard pleaded guilty and was given six weeks to pay off the shortfall. In his defense, he claimed that promised orders from “aircraft companies” for parts for “aerial projectiles” had not happened, seemingly referring in a rather obscure way to shortfalls in the anticipated orders for the model aero engines that his company had been manufacturing. This left him without funds to meet such obligations as wages owed or indeed anything else. He also stated that he could not get a job because despite having considerable experience, he was seen as being too old at age 53. This amounted to an admission that he was unable to pay – hardly surprising given the circumstances. The Court ordered him to make the payment regardless, also fining him £3. They gave him six weeks to settle up, but were very lenient with him on that score, stating that as long as he could show that he had made genuine efforts to find work which would allow him to settle up, they might show leniency if he returned unsuccessful after the six weeks, throwing himself upon the mercy of the Court. I imagine that this was exactly what he did, although the record is silent on the ultimate outcome of this particular case. The “guilty” outcome of his court appearance for this offence would have legally debarred Ballard from holding a Director’s position in any future company. He made no attempt to become involved with any such company, doubtless lacking the means to do so in any event. Instead, he opened a shop known as “Health Food Stores” at 1 Sandown Terrace, Portsmouth Road, Esher, Surrey. This was just a single small shop - what we would probably call a corner shop today. It sold confectionery and groceries. Ballard could legally be the owner of such an establishment, but could not be a Director of any associated company – his conviction in the earlier 1958 court case would have precluded that.

The attached London Gazette notices located by Marcus Tidmarsh tell the story. The first refers to the initial court appearance; the second advises claimants who the official Receiver is, where he is to be contacted and by when any one owed money must apply; and the final one defines when the receivership ended. It took over two years for the full process to be completed, naturally putting an end to the business. Unfortunately for Ballard, his troubles were far from over at this point. Marcus Tidmarsh confirmed that oddly enough, J. E. Ballard & Co. Ltd. was still in existence, although it was not active. It would seem that in addition to his failure to meet his own personal N.H.I. obligations and deal with his creditors relating to the Health Food Stores business, Ballard had also fallen into arrears in his scheduled loan repayments to New British Garden Estates Ltd. with respect to the earlier loan taken out by J. E. Ballard & Co. Ltd. On May 19th, 1962, New British Garden Estates Ltd. raised an insolvency case against J. E. Ballard & Co. Ltd. for failure to make agreed repayments. An official Administrative Receiver was appointed by the Court. Marcus discovered that there were actually three charges registered against Ballard's company, in the amounts of £2,000, £2,000 and £3,000 - a total of £7,000. In terms of purchasing power, this amount was equivalent to several million pounds in today's money. The Administrative Receiver was somehow able to recover one of the £2,000 charges in full, but was unable to secure the balance of the outstanding charges from the company’s remaining assets. Such money as was recovered would have been distributed proportionally among the three claimants unless one of them was the Crown, which always had first dibs. Normally in such cases, the Administrative Receiver will then have the company struck off, at which point it ceases to exist. However, this did not happen in this case, implying that the Administrative Receiver thought that there was some kind of remaining asset of potentially high value, albeit one that was proving very difficult to liquidate. This may have been the model engine design rights and associated tooling, for example. Amazingly enough, this situation dragged on for decades! Marcus confirmed that Ballard’s company J. E. Ballard & Co. Ltd. remained in existence in Administrative Receivership until August 13th, 2019 with the outstanding charges still registered against it. At that point, the Administrative Receiver finally gave up and had the company struck off as insolvent, with the minimum legally required notice. More and more, I begin to see the validity of Ballard’s grand-daughter’s characterization of her grandad as “a poor businessman, but a good salesman” as well as John Foster’s comment about him possessing great personal charm. He seems to have had limited professional qualifications, but was clearly highly adept at “selling himself” to others despite this. Unfortunately, his business capabilities evidently fell well short of matching his own self-characterization of those abilities – the succession of business failures which dogged him prove that. I’ve always assumed that his parting company with E.D. in 1953 was due to disagreements regarding that company’s future directions, but it now appears that the split may simply have reflected dissatisfaction among the Directors regarding his performance as Managing Director. His forceful "my way or the highway" approach to decision-making may well have caused dissention among the Board members. He may actually have been voted out!! Following the failure of his two businesses, Ballard worked for Decca Radar for some years, albeit as an employee. He seems to have "concealed" some of his assets from the Administrative Receiver, perhaps by transferring those assets into the ownership of some other person whom he trusted (his wife?!?). However he managed it, he remained sufficiently flush in the 1960's to pay for John Foster's sister (Ballard's grand-daughter) to attend a private convent school for a time. Unfortunately, that eventually came to an end, presumably because Ballard's money was running out. He ended up living in somewhat reduced circumstances in a council flat in Surbiton. His financial situation worsened to the point that John Foster's mother (Jack Ballard's daughter Jaqueline) would often have to provide food to keep him going. Despite these vicissitudes, Ballard retained his interest in model airplanes, continuing to fly them for some years on Epsom Downs. We may legitimately conclude that he was a genuine enthusiast whose career in the model trade was stunted to a significant degree by certain personality traits to which I've alluded. Ballard lived on well into his '80's, finally passing away in October 1990 at Kingston-upon-Thames just shy of his 86th birthday. Ironically enough, John Foster stated that he died of a heart attack immediately after collecting a £500 winning horse racing bet at a local bookmaker. John could never decide if his passing on such a high was a good way to go or an unlucky one, as he finally won after a succession of failures but did not get to enjoy the proceeds! Time now to return to our consideration of the engines produced by the ill-fated J.B. venture .......... The J.B. Engines on Test The first published test of a member of the J.B. range was Peter Chinn’s previously-mentioned report on the 1.5 cc J.B. Atom which appeared in the February 1956 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Reading between the lines of this report, one gets a definite impression that Chinn was expecting considerably more than he got from this then-new design. Chinn began by describing the engine in some detail. His test unit was one of those which featured a circlip to retain the gudgeon pin yoke inside the piston. The engine was apparently quite free-running, in contrast to many other examples which tended to be supplied quite tight. Even so, Chinn commented that despite the fact that it had been supplied by the factory, his test unit appeared to be “not a particularly good example”. As evidence of this, he cited the fact that the needle valve assembly was out of register as supplied, the result being that it was unable to supply a sufficiently lean mixture for all-out running. Incidentally, this seems to prove that the engines were not test-run at the factory, otherwise this fault would surely have come to light. In terms of its starting qualities, Chinn reported that an exhaust prime and a small injection of fuel into the intake venturi were aids to starting from cold. He noted that his example exhibited a small air leak beneath the cylinder installation flange, and he commented that the addition of a soft copper gasket might be a useful modification for the manufacturers to consider. Once running, the engine proved to be “reasonably free from vibration” over the tested speed range from 6,000 to 12,000 rpm. Both controls were found to be fairly sensitive for best performance, although the engine was apparently “easy to adjust” despite this. It’s interesting to note that apart from the comments summarized here, Chinn refrained from actually characterizing the engine’s starting and running qualities in his text. The implication is that he found neither characteristic to be in any way notable.

This widely-read test report cannot have helped the J.B. cause in any way. And there was worse to come in the form of Ron Warring’s subsequent test report on the J.B. Atom which appeared in the April 1956 issue of the rival “Aeromodeller” magazine. Warring began by noting that while the engine was extremely finely finished and exhibited a well thought-out design layout, it “lacked the performance to go with it”. He cited both the excessively close tolerances and the inappropriate material selection as the primary causes of this unhappy situation. Warring ended up trying two different examples of the engine. The first of these was excessively tight, and no amount of running would ease this due to the use of a hardened piston/cylinder combination and an over-tight main bearing. The second example was apparently significantly better, accordingly being used for the balance of the test. The examples reviewed by Warring both featured the screw-in gudgeon pin yoke which seems to have replaced the circlip design fairly early on. Given the figures taken from direct measurement of my own examples, it's possible that the cylinder port timing had also been amended from the figures reported earlier by Chinn, but Warring was silent on the subject of port timing, hence not providing any resolution of this issue. He did confirm that both of his examples retained the hardened piston/cylinder combination and hardened steel conrod which had also been features of Chinn's example. In connection with the latter feature, Warring noted that one of the tested engines had developed considerable wear on the gudgeon pin after only a few hours’ running. That having been said, Warring did manage to find a few positive comments. He characterized the better of his two test engines as “delightful to handle, easy starting, consistent running and as powerful as any engine in its class” with the clearly-stated proviso that the latter comment applied strictly to the engine’s use as “a low speed engine for sports flying”. If used in a higher-speed context, the engine’s performance fell well short of meeting then-current standards. On the positive side, Warring did include the comment that the engine was "substantially free from vibration at all speeds". Overall, he did his best for the manufacturer. In performance terms, Warring more or less confirmed Chinn’s earlier findings, reporting a peak output of 0.090 BHP @ 10,700 rpm. The lower power figure is likely a reflection of the evident fact that Warring's test unit was tighter than Chinn's example. In the hands of both testers, the engine was clearly done by 11,000 rpm, hence fully justifying Warring’s comments regarding the engine’s forte (if it could be said to have one!) of performing best at low speeds.

This did not prevent Peter Chinn from publishing a very positive test of the 1 cc J.B. Bomb in the June 1957 issue of “Model Aircraft”, at which time the engines were evidently still available from the stocks of several dealers. By this time, however, it’s almost certain that the company was simply liquidating their unsold inventory. Chinn must surely have been aware of this situation, making it seem possible that he felt bad about the role that his earlier test of the Atom had undoubtedly played in adversely affecting the market tenure of the J.B. range. He may well have wanted to leave some kind of positive comment on the J.B. marque, if only for posterity. The J.B. Bomb fared much better in Chinn’s hands than the poor old Atom had done. He began by stating that “in both handling characteristics and specific power output”, he found the Bomb to be “markedly superior to its larger bore brother”. Chinn then described the changes which had resulted in the smaller rendition of the basic J.B. design. These were actually far more significant than might be supposed, to the extent that the Bomb was a completely distinct design as opposed to being merely a down-sized Atom. The engine used the same crankcase and crankshaft as the larger Atom, the reduced displacement being achieved entirely through a bore reduction from 13.69 mm (0.539 in.) to 11.18 mm (0.440 in.). This combined with the unchanged 10.16 mm (0.400 in.) stroke to yield a displacement of 0.997 cc (0.0608 cuin.) and a more “normal” bore/stroke ratio of 1.100 to 1. Weight was relatively little changed at 85 gm (3 ounces) complete with back tank.

A highly significant change was a switch to a Meehanite cast iron piston in place of the hardened steel component used in the Atom. A further positive step was the use of a ball-and-socket small end on the hardened steel conrod in place of the screw-in gudgeon pin yoke of the larger engine. This eliminated the unconfined "wandering" of the conrod small end which had bedevilled the earlier Atom design. Overall, the Bomb was a significantly different design from its larger relative - far more than just the displacement had been changed. Having described the engine, Chinn proceeded to an evaluation of its performance. He characterized its starting as “quite good” and actually at its best on the lighter loads tested. Both controls were stated to be “entirely satisfactory”. In contrast to his experience with the larger Atom, Chinn found that the Bomb displayed an “ability to run at speeds well into the ‘teens without appearing “busy””. This was a slightly convoluted way of saying that running at high speed didn’t faze the engine one bit! This ability to operate comfortably at high speed was reflected in the engine’s measured peak output, which was recorded as 0.090 BHP @ 14,900 rpm - almost the same output as previously reported for the larger Atom, albeit at a far higher speed. Although not quite up to the standard of contemporary 1 cc designs such as the A-M 10, the FROG 100 Mk. II, the David-Andersen 1 cc model, the Super Tigre G.25 or the Barbini B.38, this was still a pretty good “average” performance for a 1 cc diesel of its era, albeit at a higher than average speed. It certainly topped the contemporary British E.D. Bee Series 2 and Allbon Spitfire models. Overall, a very positive endorsement on Chinn’s part. It’s too bad that the larger Atom so signally failed to match its smaller brother. If it had, the J.B. story would doubtless have ended quite differently. As far as I’m aware, neither of the J.B. glow-plug models was ever the subject of a published test. However, if the track record of glow-plug conversions of radially-ported diesels such as those produced by Allbon, E.D., AMCO and FROG is anything to go by, one wouldn't expect them to deliver miracles of performance. See below for a test of this impression. The J.B. Design Re-Evaluated I have five complete J.B. 1.5 cc engines on hand – two Atom diesels and three Atomglow models. The previously-illustrated examples of each model are both LN and appear to have had very little running.

He had also turned some metal off the top of the crankcase where the cylinder seats when screwed in – why beats me, since the sub-piston induction and cylinder port timing both become truly ridiculous with the lower cylinder. In his defence, the possibility must be recognized that the case is from a 1 cc Bomb (see above), although I’m not in a position to confirm or refute this possibility. It's certainly a total mis-match for the Atom cylinder with which the engine was received. The working components had obviously done some running prior to this, since the conrod small end bearing and gudgeon pin were completely shot. However, the crankpin was thankfully OK. The engine was otherwise complete and original – it even retained its spinner and tank as well as its original needle valve assembly.

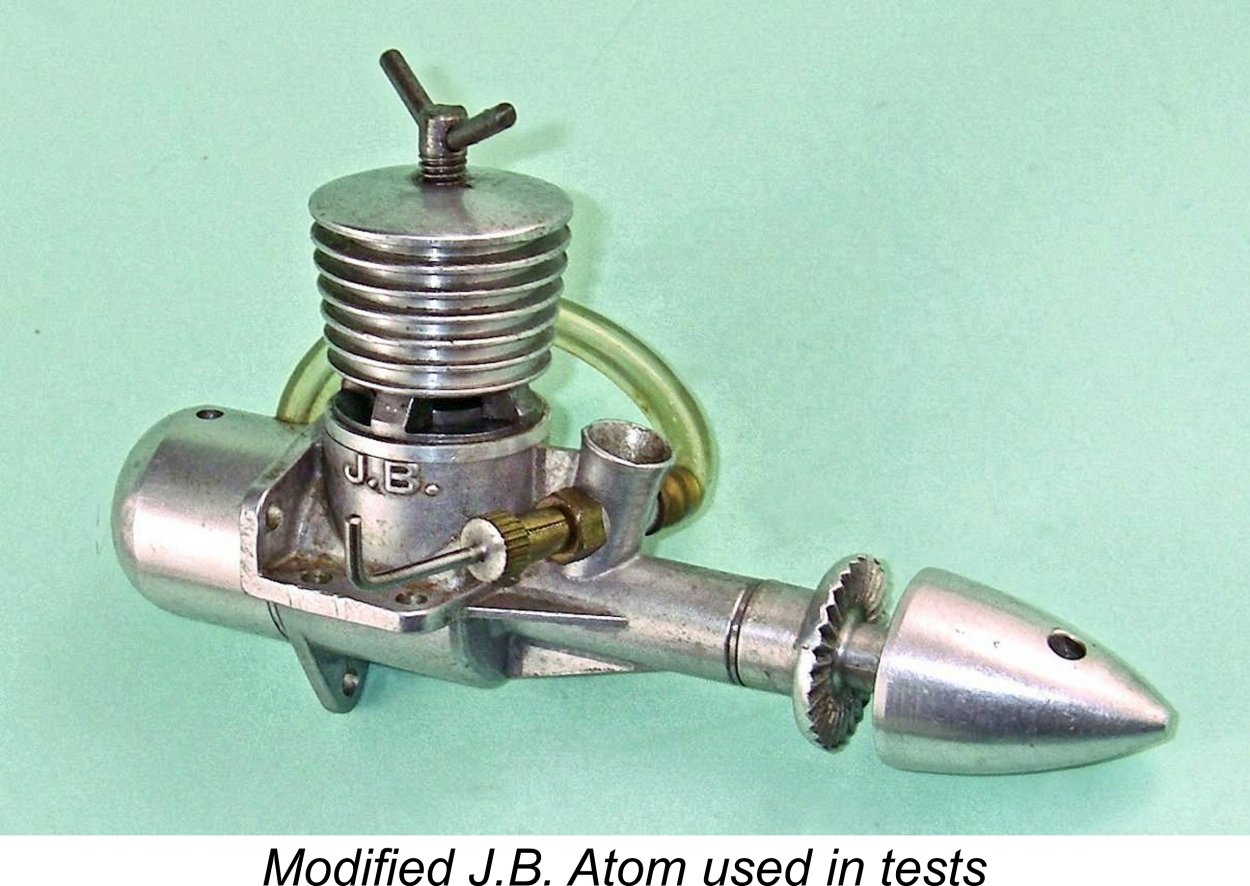

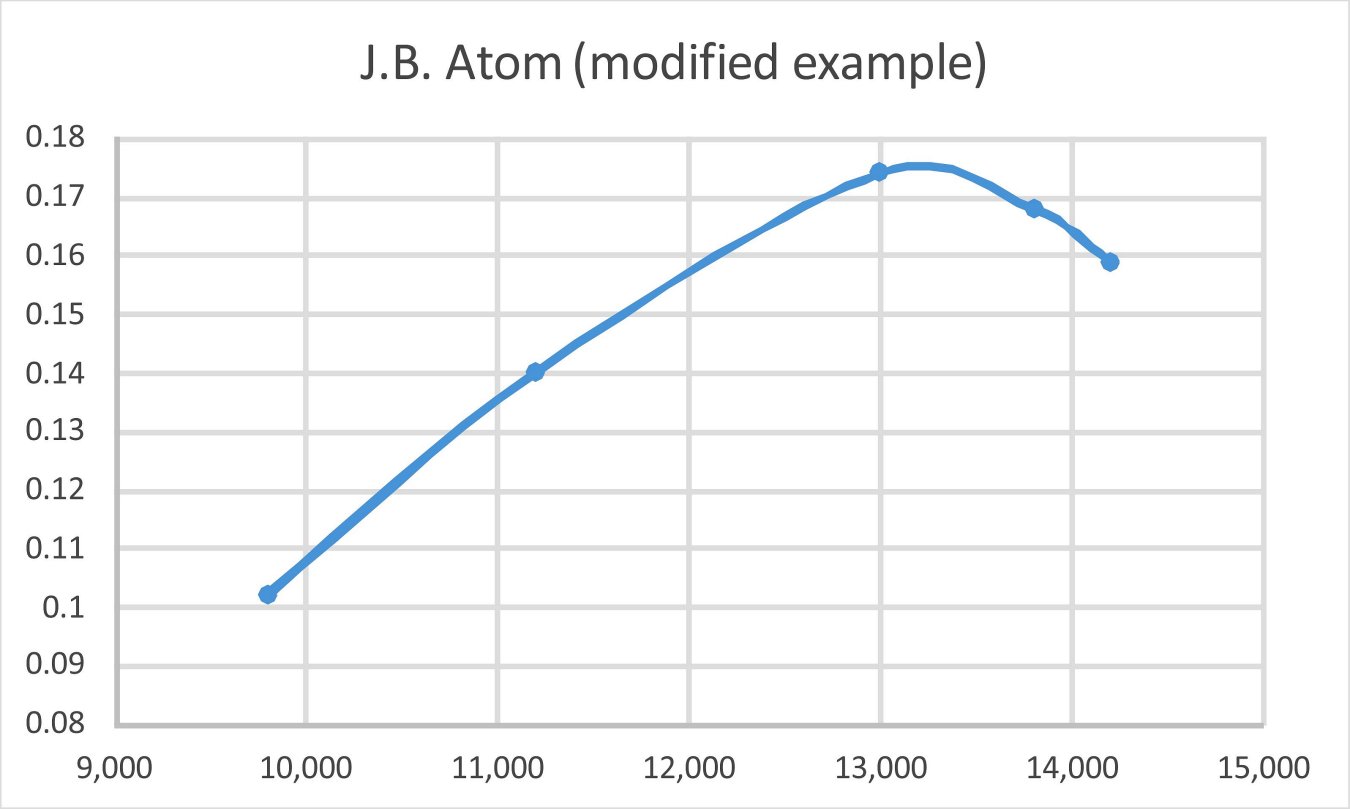

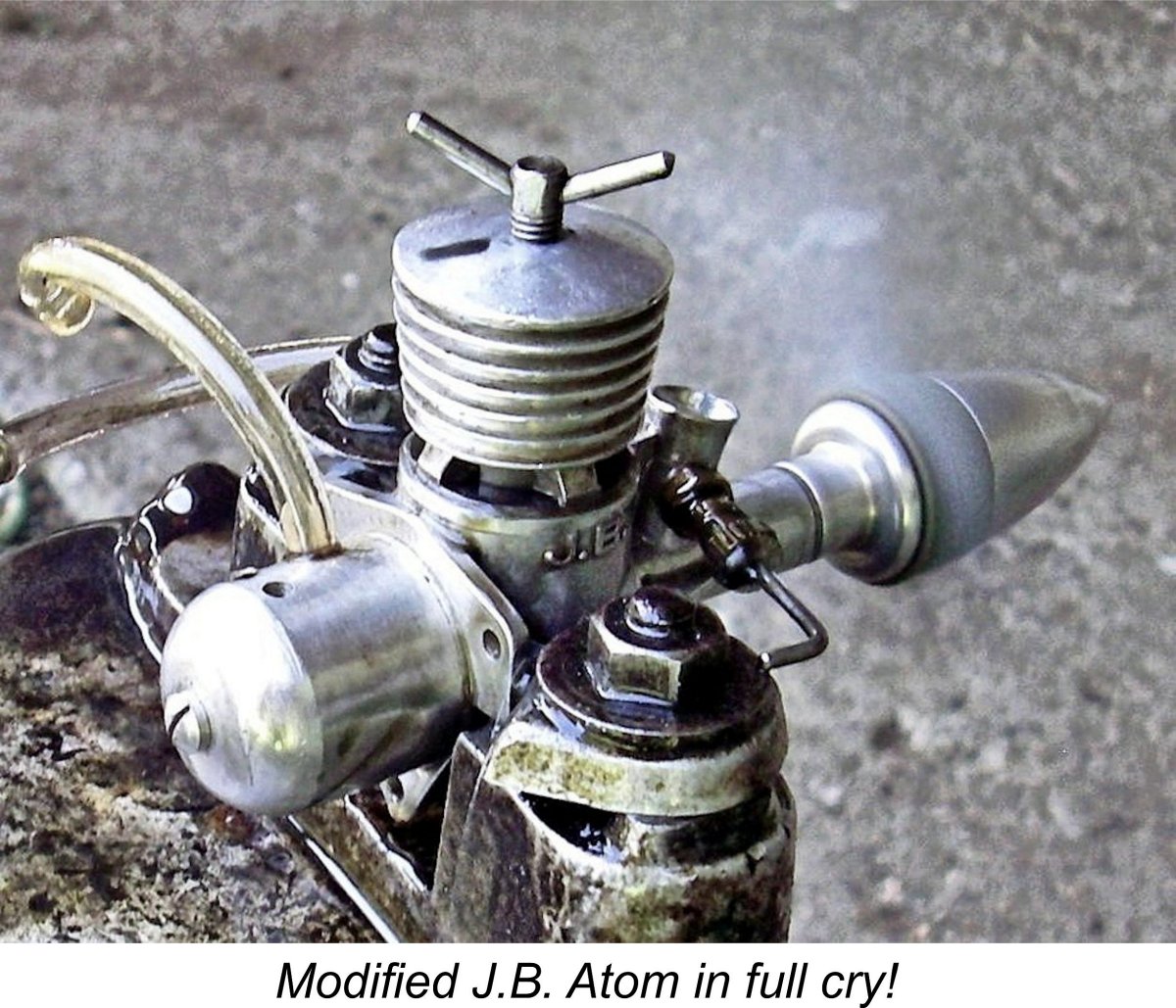

The result was a J.B. Atom that was correctly fitted and amenable to optimizing the fits by running-in using standard procedures. I did this, with quite impressive results! The re-fitted and fully run-in engine was no ball of fire, but it ran far better than the contemporary published tests would have led anyone to believe. It was also an absolute breeze to start. Finally, it seemed set for a long working life. This was great, but there was the potential for even more – I previously noted that the cylinder port timing as measured from my original and unmodified example was extremely conservative (ports open late and remain open for a relatively short time). I had duplicated these figures with my new spacer, but felt that the engine might benefit from a somewhat less conservative configuration. I therefore tried using a thicker spacer under the cylinder to further raise the deck height and thus increase the port opening period to give an exhaust period of a more rational 130 degrees, with a corresponding increase in the transfer period. Although some of the sub-piston induction period was thereby lost, the results were very positive – the engine began performing well up to the best mid-fifties 1.5 cc diesel standards! As you'd expect, starting was not quite as good, but torque development was greatly enhanced. This work was carried out some years ago, soon after I acquired the engine. I recently re-tested this example to confirm my earlier notes. As before, the modified Atom started quite easily with a small prime, its only vice being a certain tendency towards viciousness on the 7 inch and smaller props. This is probably a reflection of the ultra-short stroke. Once going, the engine proved itself to be very responsive to the controls, hence being easy to set. Both controls held their settings perfectly at all speeds. Running qualities were outstanding - never a missed beat and no tendency to sag. Vibration levels appeared to be minimal, presumably thanks to the very light piston and rod that I had made for the engine. The measured prop/rpm figures were quite remarkable in light of the engine's lacklustre showings in the hands of the contemporary testers. The following data were obtained on test.

The implied output is around 0.176 BHP @ 13,300 rpm. This would have put the Atom right up there among the top performers of its day - in fact, in terms of mid-range torque development it would have been among the very best. A quite remarkable performance for such a short-stroke engine! This is an astonishing result, although we should remember that the Atom has what amounts to Oliver porting along with sub-piston induction, both of which ought to encourage pretty free breathing. In addition, the tested example is well run in and perfectly fitted as well as having its cylinder port timing extended and its shaft fit freed up.

If it had been released with the standard material specification and structure of my “restoration”, particularly with the modified timing that I tried, the Atom would have taken its place among the more respected British engines of the mid-1950’s and the J.B. company would likely have gone on to far greater things. Quite apart from its good performance potential, the engine’s very attractive appearance and presentation would have ensured a very favorable reception. One wonders why the company failed to see this for themselves …….. but the fact is that the previously-summarized “Aeromodeller” test of April 1956 probably doomed the engine irretrievably. Ron Warring was clearly struggling to find good things to say about the Atom, but the review speaks for itself regardless ……. I wouldn’t have bought one after reading that! The actual manufacture of the J.B. range appears to have ended in late 1956. I’ve always wondered what subsequently became of Charlie Cray, who disappeared from modelling history at this point ………… does any reader know?!? His experiences with the J.B range must surely have left an extremely bitter taste in his mouth - so near and yet so far............... The J.B. Atomglow on Test

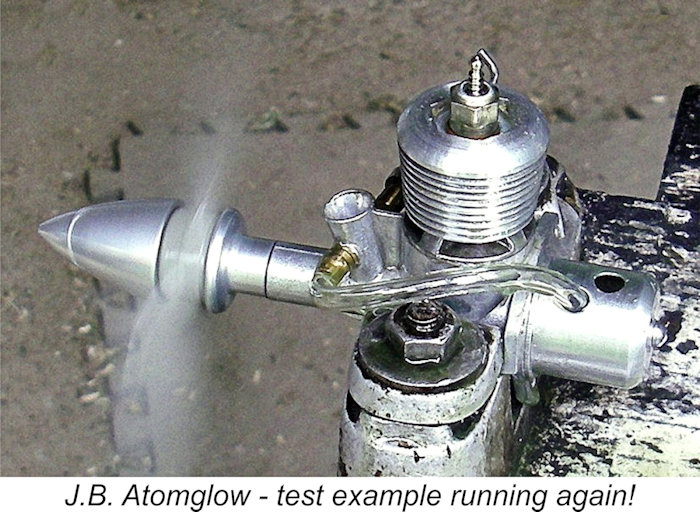

The steel rod set-up appears adequate to meet the somewhat lesser stress demands of the glow-plug version. Compression ratio of my test example is unusually low at a measured 6.5:1, and the engine clearly needs some nitro to run well. A few test runs carried out some years ago demonstrated that the engine started and ran just fine, but seemed pretty lacking in power. No doubt it would do better with a raising spacer under the cylinder to advance the port timing. But then you’d have to find a way to re-establish the compression ratio …………………. Two of my three examples of the Atomglow are little-used all-original examples. It was these examples that I had tried earlier, with modest results. However, my third example arrived more recently in rather sad shape with a totally clapped-out rod and a crankshaft which had been inexpertly modified by someone and had promptly cracked during operation, scoring the main bearing. I sent it down to my good mate Dean Clarke of Cre8tionworx Engineering in New Zealand, who carried out his usual superb restoration of the poor abused little beastie. His efforts are documented here. He supplied a new original case, crankshaft and spinner nut, also re-finishing the bore and making a new lightweight cast iron piston with a conventional alloy rod and gudgeon pin. This put the engine back into better-than-new condition, simply begging for a few test runs. As stated earlier, no test of either of the J.B. glow-plug models was ever published. This left it down to me to boldly go where no tester has gone before! Given the engine's very low compression ratio, I decided to use a "hot" glow-plug along with a fuel containing 15% nitro. Even so, I wasn't expecting miracles of performance from this unit.

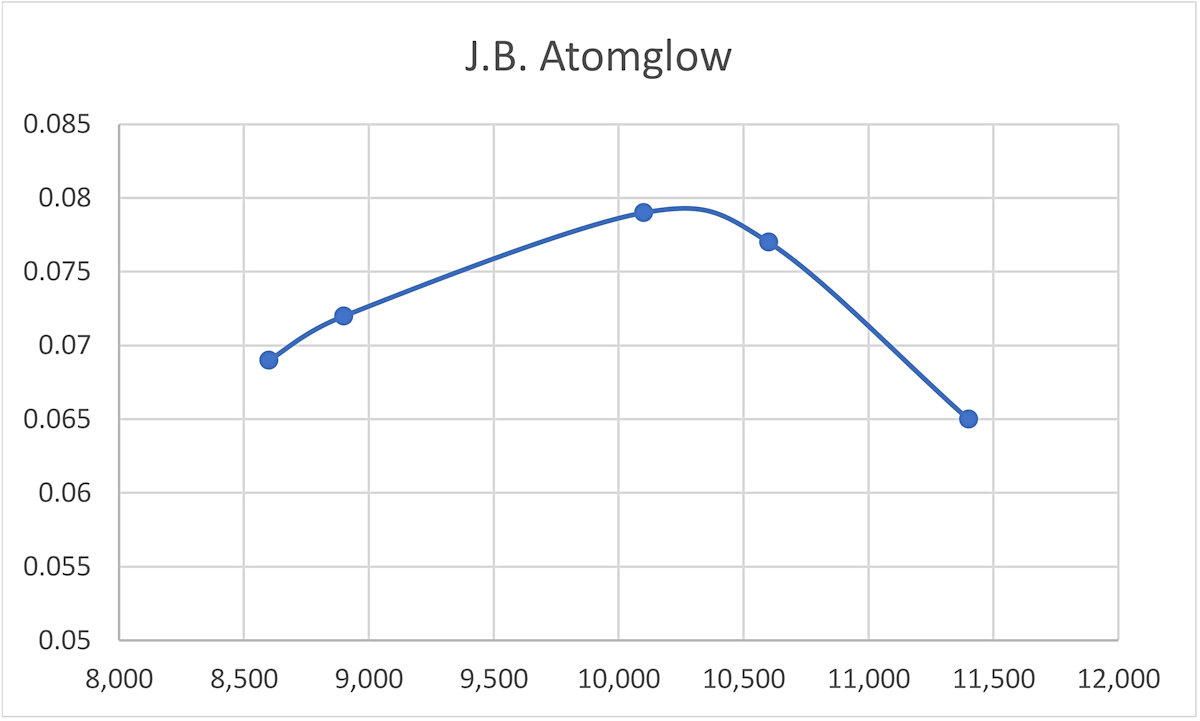

The engine started very promptly indeed following the administration of a port prime plus a few drops of fuel down the intake. Unfortunately, "fairly fast" turned out to be only around 9,000 RPM on a rich needle - it was already apparent that this engine was not going to set any performance records! Despite this discouraging indication, I stuck to my plan, putting around 30 minutes on the engine in 4-minute runs, leaning out briefly right at the end to put the piston/cylinder components through a few complete heat cycles. The engine maintained its excellent starting characteristics throughout. At the end of this period of break-in running, the engine felt superb - clearly all ready for testing. For this stage of the process, I switched to the engine's own back tank, which provided ample running time to permit a slightly rich warm-up followed by a re-set of the needle to obtain peak RPM for each prop. In this way the break-in continued while I was securing the required prop-RPM data. My somewhat modest performance expectations were amply fulfilled! The engine ran smoothly enough at all speeds up to 10,500 RPM, but at that point a misfire crept in which couldn't be eliminated with the needle valve - a classic symptom of under-compression in a glow-plug motor. It became clear that the engine really didn't want to run much above 11,000 RPM - at that speed, it had evidently out-run the ignition timing imposed by its relatively modest compression ratio. The following data were recorded:

Based upon the above figures, the Atomglow appeared to develop a peak output of around 0.080 BHP @ 10,300 RPM. This is actually not that far below the rather unflattering figures established by Ron Warring for the J.B. Atom diesel. Moreover, the above findings are consistent with the fact that both Ron Warring and Peter Chinn found that the Atom was pretty much I have little doubt that an increase in the compression ratio to around 8 to 1 would do wonders for the performance of the Atomglow. As it is, the engine's performance falls well below the standards expected of a 1.5 cc engine by 1956. The engine is a fine handling unit which would have been extremely beginner-friendly and would probably have a good working life in glow-plug configuration, but those qualities would not have sufficed to secure a place for it in the model engine marketplace of 1956. In any case, such considerations were probably moot - matters probably never got as far as that. British aeromodellers had yet to fully embrace glow-plug powerplants as of the mid-1950's, and the unfavorable test reports on the Atom diesel would doubtless have translated into a high level of market resistance towards the Atomglow. It's unlikely that many people even bothered to give the engine a try. Anyone who did so would almost certainly have been quite disappointed ............. Conclusion

The fact that the J.B engines failed to realize upon this potential is more down to a few poor choices in terms of material selection and fitting tolerances than anything else. The choice of an absurdly low compression ratio did absolutely nothing for the performance of the Atomglow. I suspect that Jack Ballard’s seemingly characteristic impatience may have got the better of him, leading to a premature release of the Atom and Atomglow before their flaws had become fully apparent. A more focused and lengthy field testing program would surely have revealed most of the flaws identified by Ron Warring, allowing for their correction prior to the engine's release. As it was, the fact that Ballard had acquired a track record of announcing new designs that never materialized may have overcome his better judgment by making him over-anxious to avoid yet another seeming example of the same unhappy syndrome. It’s also very likely that he faced a cash flow problem, hence needing to get some product out there to generate revenue. In hindsight, all of this is a great pity, because the surviving examples prove that the company had the ability to produce model engines to very acceptable standards. With further development prior to release, the J.B. range might well have achieved a significant presence in the British model engine market. As it is, we’re left with a relatively small number of examples of the work of the J.B. company to remind us of what might have been. I hope you’ve enjoyed this retrospective look as one of the British model engine manufacturing industry’s most significant, lamentable and (in hindsight) avoidable failures. ______________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published May 2018 Updated January 2020 Second update June 2025 - personal info on Jack Ballard, Atomglow test |

||

| |

In this article, I’ll summarize the rather sad history of one of England’s less well-remembered model engine ranges – the J.B. marque. This short-lived series was extremely well made, attractively presented and aggressively marketed, but the engines suffered from some fundamental material selection and production flaws which led to their rapid eclipse in the highly competitive British model engine market of the mid 1950’s. The range was only advertised for some 16 months, from October 1955 until January 1957. Good examples are quite rare today.

In this article, I’ll summarize the rather sad history of one of England’s less well-remembered model engine ranges – the J.B. marque. This short-lived series was extremely well made, attractively presented and aggressively marketed, but the engines suffered from some fundamental material selection and production flaws which led to their rapid eclipse in the highly competitive British model engine market of the mid 1950’s. The range was only advertised for some 16 months, from October 1955 until January 1957. Good examples are quite rare today.

It was at this point that significant changes began to take place among those responsible for the management of the company and the development of its products. The first overt symptom of the

It was at this point that significant changes began to take place among those responsible for the management of the company and the development of its products. The first overt symptom of the  While all of this was going on, events had been unfolding elsewhere that would have a bearing on our story. Beginning in August 1947 the Chester-based Anchor Motor Company had quickly become a significant player in the British model engine manufacturing market, first with the company’s excellent little

While all of this was going on, events had been unfolding elsewhere that would have a bearing on our story. Beginning in August 1947 the Chester-based Anchor Motor Company had quickly become a significant player in the British model engine manufacturing market, first with the company’s excellent little  The AMCO name, goodwill, designs, tooling, parts and dies were offered for sale, eventually being purchased by a newly-formed London-based company, the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. of Alperton, Middlesex (near Ealing). The managing director of this company was a certain F. F. Wells, about whom I have been unable to uncover any specific information.

The AMCO name, goodwill, designs, tooling, parts and dies were offered for sale, eventually being purchased by a newly-formed London-based company, the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. of Alperton, Middlesex (near Ealing). The managing director of this company was a certain F. F. Wells, about whom I have been unable to uncover any specific information.  There could have been no better choice than Allen to step into the shoes of

There could have been no better choice than Allen to step into the shoes of

Ballard quickly drew up a characteristically ambitious plan for a major expansion of the AMCO range, as reflected in the company’s advertisement in the December 1953 issue of “Aeromodeller”. This advertisement also highlighted the division of the company into the two previously-mentioned business entities.

Ballard quickly drew up a characteristically ambitious plan for a major expansion of the AMCO range, as reflected in the company’s advertisement in the December 1953 issue of “Aeromodeller”. This advertisement also highlighted the division of the company into the two previously-mentioned business entities.  Allen’s first diesel under his own name, the Mk. I

Allen’s first diesel under his own name, the Mk. I  The above chain of events makes it clear that Allen’s association with Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. must have ended at some point in the first half of 1954. Allen's departure was likely the major catalyst in derailing Jack Ballard’s ambitious plans for expansion of the AMCO range - his departure plus that of Len Steward seems to have left a major void in the company's engineering department that was never filled.

The above chain of events makes it clear that Allen’s association with Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. must have ended at some point in the first half of 1954. Allen's departure was likely the major catalyst in derailing Jack Ballard’s ambitious plans for expansion of the AMCO range - his departure plus that of Len Steward seems to have left a major void in the company's engineering department that was never filled.  At some point during the latter part of 1954, Jack Ballard clearly decided that AMCO Model Engines Ltd. was not a long-term winning proposition. Accordingly, the time was right to make a further move. He prepared the ground for such a move by forming yet another new company, this time under his own name. J. E. Ballard & Co. Ltd. came into existence on December 22

At some point during the latter part of 1954, Jack Ballard clearly decided that AMCO Model Engines Ltd. was not a long-term winning proposition. Accordingly, the time was right to make a further move. He prepared the ground for such a move by forming yet another new company, this time under his own name. J. E. Ballard & Co. Ltd. came into existence on December 22

We’ve seen that the all-new J.B. Atom appeared on the market in October 1955 after a lengthy period of development. But was it in fact all-new?!? Not at all - in reality the J.B. Atom was nothing more than a somewhat revised and re-branded AMCO Atom, the previously-mentioned still-born mid-1954 product of the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co.!

We’ve seen that the all-new J.B. Atom appeared on the market in October 1955 after a lengthy period of development. But was it in fact all-new?!? Not at all - in reality the J.B. Atom was nothing more than a somewhat revised and re-branded AMCO Atom, the previously-mentioned still-born mid-1954 product of the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co.!

Unfortunately, the pattern was repeated – the business ran into debt problems relatively quickly. One suspects that Ballard was prone to living beyond his means! A number of creditors took him to court in 1962, after which a Receiver was appointed. In the subsequent proceedings, Ballard was referred to as a “grocer”.

Unfortunately, the pattern was repeated – the business ran into debt problems relatively quickly. One suspects that Ballard was prone to living beyond his means! A number of creditors took him to court in 1962, after which a Receiver was appointed. In the subsequent proceedings, Ballard was referred to as a “grocer”.  In performance terms, the Atom was a clear disappointment. According to the power curve which was included with the test report, Chinn measured a peak output of around 0.102 BHP @ 10,700 rpm, a very sub-standard set of figures for a 1.5 cc diesel by the standards of the day. Although Chinn refrained from saying so, a number of previously-tested 1.5 cc units had exceeded both of these figures by a significant margin. Chinn’s disappointment is implied by the fact that he did not quote these numbers in the actual text of his report, also avoiding making any performance comparisons with other competing models. This is typical of Chinn’s test reports, especially those involving new British engines – if he couldn’t find anything positive to say, he generally said nothing …………

In performance terms, the Atom was a clear disappointment. According to the power curve which was included with the test report, Chinn measured a peak output of around 0.102 BHP @ 10,700 rpm, a very sub-standard set of figures for a 1.5 cc diesel by the standards of the day. Although Chinn refrained from saying so, a number of previously-tested 1.5 cc units had exceeded both of these figures by a significant margin. Chinn’s disappointment is implied by the fact that he did not quote these numbers in the actual text of his report, also avoiding making any performance comparisons with other competing models. This is typical of Chinn’s test reports, especially those involving new British engines – if he couldn’t find anything positive to say, he generally said nothing …………  Taken together, these two test reports in effect damned the engine with faint praise, especially in performance terms. In particular, Warring’s more openly negative test report on the Atom probably ended the company’s chances of success in the marketplace. As mentioned previously, the J.B. range was unable to weather the unfavourable publicity which these two reports combined to generate, disappearing from the market in early 1957.

Taken together, these two test reports in effect damned the engine with faint praise, especially in performance terms. In particular, Warring’s more openly negative test report on the Atom probably ended the company’s chances of success in the marketplace. As mentioned previously, the J.B. range was unable to weather the unfavourable publicity which these two reports combined to generate, disappearing from the market in early 1957.  The number of exhaust and transfer ports was reduced from four to three apiece, no doubt in deference to the smaller bore circumference. The greater thickness of the lower cylinder wall resulting from the reduced bore combined with the same male cylinder installation thread allowed the use of internally-cut bypass flutes in place of the former drilled transfer ports with external flutes. The cylinder port timing was also modified by lowering the cylinder in the crankcase through the skimming of some material off the top of the crankcase. Presumably the piston skirt length was adjusted appropriately.

The number of exhaust and transfer ports was reduced from four to three apiece, no doubt in deference to the smaller bore circumference. The greater thickness of the lower cylinder wall resulting from the reduced bore combined with the same male cylinder installation thread allowed the use of internally-cut bypass flutes in place of the former drilled transfer ports with external flutes. The cylinder port timing was also modified by lowering the cylinder in the crankcase through the skimming of some material off the top of the crankcase. Presumably the piston skirt length was adjusted appropriately.  One of my two Atom diesels is highly significant insofar as it has provided me with the opportunity to evaluate the potential of the design in considerable depth. As received, it had been the subject of an assault upon its structure by someone who hadn’t a clue what he was doing! He’d started to grind one of the exhaust ports for reasons which escape me, thankfully stopping before the timing was affected, and had managed to mar the bore slightly but significantly in the process. It may have been this that caused him to give up before more damage was done!

One of my two Atom diesels is highly significant insofar as it has provided me with the opportunity to evaluate the potential of the design in considerable depth. As received, it had been the subject of an assault upon its structure by someone who hadn’t a clue what he was doing! He’d started to grind one of the exhaust ports for reasons which escape me, thankfully stopping before the timing was affected, and had managed to mar the bore slightly but significantly in the process. It may have been this that caused him to give up before more damage was done!  I decided that since the engine needed a rebore in any case, I might as well rebuild it to appropriate engineering standards, just as it should have been made in the first place. I re-lapped the cylinder to deal with the results of the previous owner’s meddling, and made a new conventional piston of Meehanite cast iron, internally milled for lightness. I also made an alloy conrod which was fitted to the replacement piston using a pressed-in gudgeon pin. Next, I made a ring spacer for the top of the case which re-established something akin to the correct deck height. Finally, I lapped the shaft to establish an optimum fit – it was way too tight as received.