|

|

Shanghai Side-Ports - the CS NAVO Mills Replicas

Perhaps the most frequently replicated or imitated engines of them all have been the sideport models manufactured by Mills Brothers between 1946 and 1964. These iconic designs have been subjected to the replica or look-alike treatment from a surprising number of manufacturers around the world, none of whom have had much trouble selling their products once their credentials were established. Indeed, many of these replicas and derivatives have become highly-prized collector’s items in their own right. The Mills engines are also well-established sources of inspiration among members of the model engineering community who build their own model I/C engines. Of course, there’s a downside to all of this. The transition from useable replica to collector's item is only a very short step, with the result that many of the better replica or look-alike Mills-based creations have quickly made the transition from the readily-available and hence flyable engines that they were created to be to sought-after and hence high-priced collectibles. Consequently they have tended to disappear into collections, thus being effectively removed from practical use or even from circulation in the marketplace. As a result, there has long been a niche waiting to be filled by the next company to come up with a Mills replica, provided the products of said company meet user expectations in terms of quality and performance. In a separate article on this site, the late David Owen and I have jointly presented a summary of the commercial producers large and small who have ventured into the realm of Mills diesel reproduction/replication. That summary may not be complete, and I hope that any reader who is aware of a Mills replica series that we've missed will kindly enlighten me! In the meantime, the present article will constitute an evaluation of two of the more commonly-encountered and affordable Mills replicas - the NAVO .75 and 1.3 models manufactured up to 2015 by one of the more recent entrants into this field, namely the CS company of Shangai, China. These engines have so far maintained their place in the "flyable engine" category, hence hopefully being of practical interest to those who wish to indulge in the "Mills flying experience" at reasonable cost and without risk to a more valuable original.

Contrary to a seemingly widespread misconception, CS was a very small company run by a mere handful of genuine enthusiasts on a part-time basis. Far from being (as some people have seen it) a crass attempt to cash in on the nostalgia market, the CS venture was very much a labor of love from the start – if it had not been so, the marque would have disappeared far earlier than it did. As of mid-2014, the company’s four full-time employees were cranking out an average of around 50 model engines per month in addition to undertaking other work. At production levels such as these, no-one was getting rich from the model engines! Sadly, changing economic conditions combined with the steep world-wide decline in demand for model I/C engines as the electrics continued their seemingly inexorable take-over caused CS to abandon the model engine field in the latter part of 2015, re-directing their efforts into other more remunerative business lines. I for one was very sorry to see this happen – I always felt that CS were making a valuable contribution to the preservation of “classic” aeromodelling as I knew and loved it.

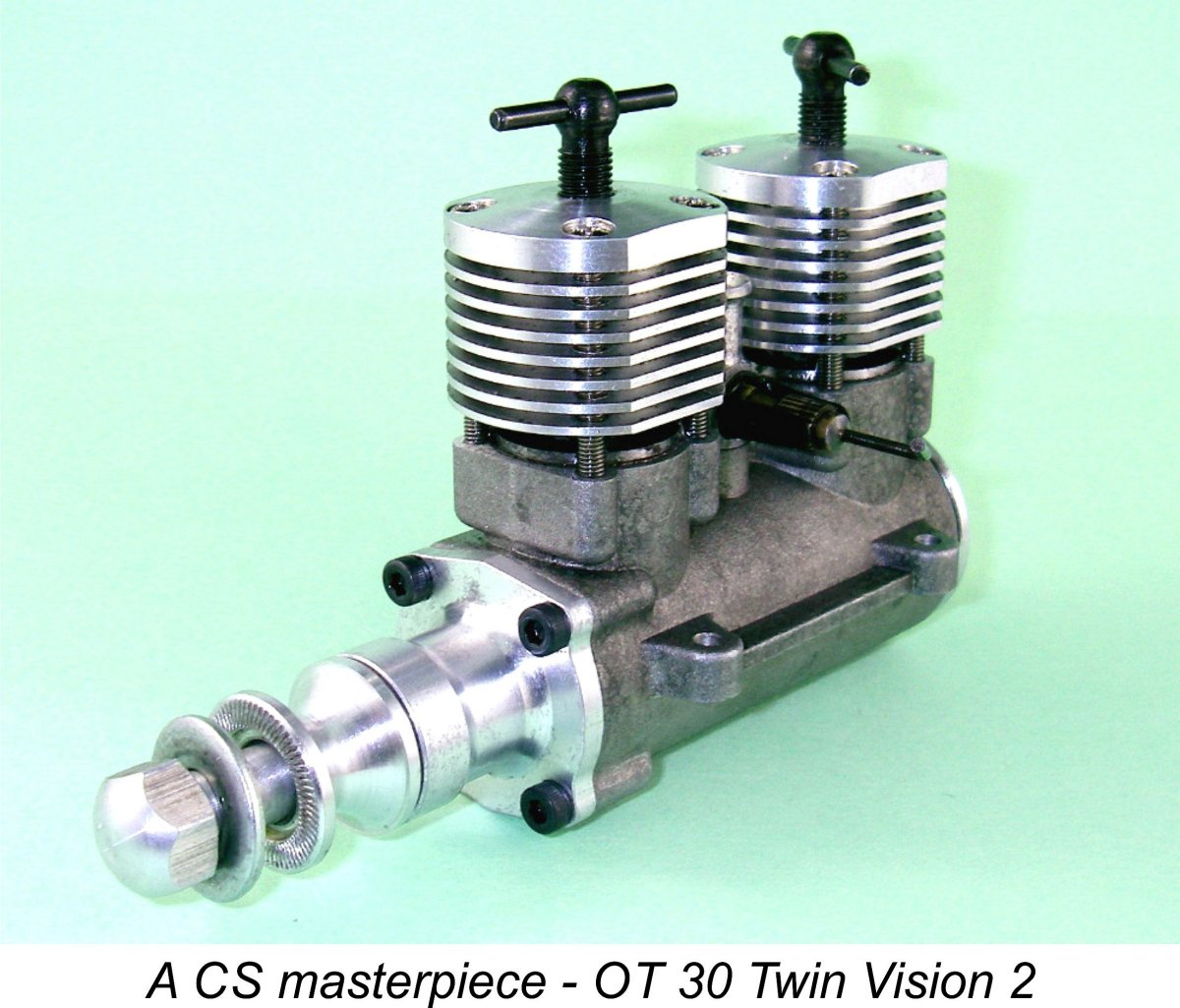

I have previously posted reviews of a number of more recent CS products, all of which have underscored CS’s latter-day success in raising those standards. Their well-executed CT09 Oliver Tiger Cub replica which I had the pleasure of testing for "AeroModeller" magazine (April 2015 issue) was a noteworthy case in point. There was also the excellent little NAVO 0.375 cc sideport model, a full review of which may be found elsewhere on this website. The company's design capabilities were also expanding to match, as witness their outstanding OT 30 Twin 5 cc diesel in its much-improved “Vision 2” form, Check here for an amusing video of my first starting attempt using this engine - note my comment just before it starts! Pessimist .................!! There was also their neat little 1.5 cc Mills-based "Boddo Twin" unit, of which more below. Still, the fact that the model engine marketplace never really ceased to view CS products with some reservations is completely understandable given their earlier history. This being the case, I felt it to be worthwhile to conduct and publish independent reviews of new CS products as they appeared. Love them or hate them, there could have been no argument against the fact that the company had become one of the most important sources of classic replicas and derivatives worldwide, making it highly desirable that their efforts be maintained and further encouraged as far as I was concerned.

Having said this, I never at any time sugar-coated my reviews of CS products. I knew from my direct contacts with the company (which continued right to the end and beyond) that they read my articles very attentively and that design improvements were often made on the basis of my comments. This being the case, only honest and objective advice would support the dual goals of helping CS to improve their design and manufacturing standards while at the same time informing prospective purchasers of any issues embodied in a given product. I have always adhered to the principle of reporting honestly and objectively on any and all engines reviewed. The present review will uphold that policy. As a sidebar issue, I was delighted to hear from company owner Peng Han in August 2018 that he was then planning to resume model engine development and production, starting with a very unusual valved two-stroke glow-plug model. No indication was given that further batches of the NAVO sideports or any of the other classic CS products would be produced, but a measure of hope was briefly restored! As events were to prove, this effort came to nothing in the end - too bad. Now, having set the ground rules, let’s proceed to take a look at CS’s renditions of two Mills favourites – the Mk. 2 versions of the .75 and 1.3 models. Although production has long been discontinued, these engines remain readily available on eBay and elsewhere. This being the case, there's every chance that anyone interested should be able to find an example. The CS Mills Models - Description

At the time of these legal actions, Dave was selling the engines on the British market as "Boddo Mills" units, while CS had been marketing them elsewhere on their own account as "Miller" engines. This of course fooled nobody, including Aurora! The eventual settlement allowed Dave to sell off his existing stocks but required him not to order any more. CS's response was to drop the Miller name and continue marketing the engines under the NAVO banner, doing so right up to their departure from the model engine manufacturing field in late 2015. You may encounter these units under any of these three names (Boddo Mills, NAVO, Miller), but they're the same engines regardless. The late David Owen and I covered this incident and much more in our companion article on the Mills replicas. All of the engines in this series were side-port diesels which generally adhered to the design “formula” established by Arnold Hardinge and Mills Brothers over 70 years ago now (as of late 2016). The NAVO side-port series was marketed in a range of displacements which considerably exceeded that of the original Mills side-port models, having included engines with displacements of 0.375 cc, 0.5 cc. 0.75 cc, 0.8 cc and 1.3 cc. As stated earlier, I reviewed the lovely little NAVO .375 cc model in a separate article on this site. The two NAVO side-port models which most closely adhered to the design of their Mills progenitors were the 0.75 cc and 1.3 cc models. The examples of those models which will be discussed here were obtained new from the manufacturers prior to their departure from the scene in the latter part of 2015. Functionally speaking, these engines amount to clones of the original Series 2 Mills P.75 (without cut-out) and 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 2 designs. The familiarity of most model diesel enthusiasts with the classic Mills engines is such that detailed descriptions of the CS renditions are not really warranted in this article – the pictures and published reviews tell the story for the most part. All that is necessary here is to point out the relatively minor differences which are apparent. Readers requiring more information on the original Mills engines are referred to my separate article on Mills production history which appears elsewhere on this website.

The most readily apparent differences are of course in the crankcase and cooling jacket. The cases are cast in aluminium alloy rather than the magnesium alloy of the Mills originals. This is actually a positive move in terms of the engines’ longevity – despite the chemical blackening treatment which was applied to the Mills originals to inhibit corrosion, the eagerness with which magnesium alloy tries to return to its elemental state through corrosion has always posed a problem for Mills owners in conservation terms. Readers interested in this magnesium corrosion issue are referred to my separate article on this subject which appears elsewhere on this web-site. No such problems can be expected with the aluminium alloy cases of the CS models. The quality of the castings is very high, as usual with CS products. The cases are given a nice-looking matte finish, being otherwise left in their natural state.

Finally, the tanks on both CS models are different in shape from those of the Mills originals, that of the 1.3 model in particular being considerably deeper but of lesser diameter. There are of course other minor differences which are peculiar to one model or the other. The NAVO .75 model features a prop driver which is machined from hexagonal bar stock as opposed to the disc-shaped steel unit used on the original Mills .75 model. The spinner nut too has a different contour and is anodized gold to match the head. The NAVO 1.3 model dispenses with the cut-out fitted to the original Mills 1.3 model, also sporting a somewhat larger un-anodized spinner nut along with a plain alloy prop driver.

In the un-run state, the working fits on the tested examples appeared to be pretty much perfect, with no detectable play in the rod bearings and seemingly-optimal piston/cylinder fits. As received, neither engine appeared to have been run at the factory – there’s no hiding the tell-tale aroma of diesel fuel residues or the traces of castor oil in an engine that has been run! Before attempting to run either of these two new-in-box NAVO models, I followed my usual practise with new CS engines of taking them apart to check for any assembly issues or shop residues which may have remained in them following the assembly process. This was a recurring problem with earlier CS designs, and one of which the company was repeatedly made aware by myself and others. I’m very happy to be able to report that both of these engines were found to be scrupulously clean internally. The three previously-tested CS models (the OT 30 Twin, the NAVO .375 and the CT09 Oliver Tiger Cub replica) were all similarly clean as supplied. This particular lesson appears to have been well learned by CS as time went by.

By contrast, the CS model uses a nicely-machined alloy prop driver which mounts on a tapered split collar. While this provides a very secure and long-lasting wobble-free mounting, it means that small variations in the machining of the tapers in either the prop driver or its split collar have a significant effect upon the clearance between the rear face of the prop driver and the forward end of the main bearing when the prop is tightened up. In the case of the test example of the NAVO 1.3, the amount of end-float with the prop fully tightened was sufficient that when the shaft was set back, the end of the crankpin contacted the backplate well before the rear face of the prop driver contacted the main bearing. This of course in no way prevented the engine from running. However, if the engine was used in a pusher configuration (or if it started backwards - a very common occurrence with side-port engines), the thrust would all be taken by the end of the crankpin rubbing against the front face of the backplate. This of course would gouge a circular groove in the backplate very quickly, sending a steady stream of aluminium alloy particles through the engine, to its potential detriment. It's this kind of issue that justified a thorough inspection of any new CS product. Almost all such issues are easily fixed by a knowledgeable owner, after which the engines become highly servicable units. In the present instance, the fix was to ensure that prop drivers were matched to their collars such that the correct end-float (5 to 10 thou, or .12 to .25 mm) was present when the prop was fully tightened. Easily accomplished by anyone having access to a lathe. Failing that, a steel thrust washer of appropriate thickness could be installed between the prop driver and the front of the main bearing. This was the approach that I adopted in correcting this condition with my test engine, since an alloy-on-steel combination wears far better than alloy-on-alloy. The end-float of the shaft in the NAVO .75 model was perfect as supplied. However, it subsequently turned out not to be immune from any issues requiring attention, as we shall see in due course. Another point which seems worth mentioning is the fact that the needles in both models are one-piece all-brass items. The taper of the needle might be expected to wear relatively rapidly as a result. A minor point, but I would have preferred to see the use of a steel needle set into the brass thimble. Having said this, the needles supplied with the engines worked perfectly well, as will become apparent below. In other respects, I have to honestly classify the quality of construction of both these particular engines as high. All fits and finishes appeared to be excellent as supplied, with nice snug bearings and outstanding compression seals. If they were all as good as these two, buyers would have had little about which to complain in terms of quality despite the fact that, as so often with CS engines, each presented an issue requiring attention prior to use. OK, so here we have two very well-made engines which follow the Mills design pattern almost exactly while presenting themselves visually in a quite distinct guise. How do they compare in performance terms? Let’s find out!! The NAVO and Mills Models Compared on the Bench Both of the subject NAVO models are based upon the final production versions of the original Mills P.75 and 1.3 designs. Accordingly, I selected a pair of used but still very well-fitted late-model original Mills engines from my own collection to use as bench-marks for comparison purposes.

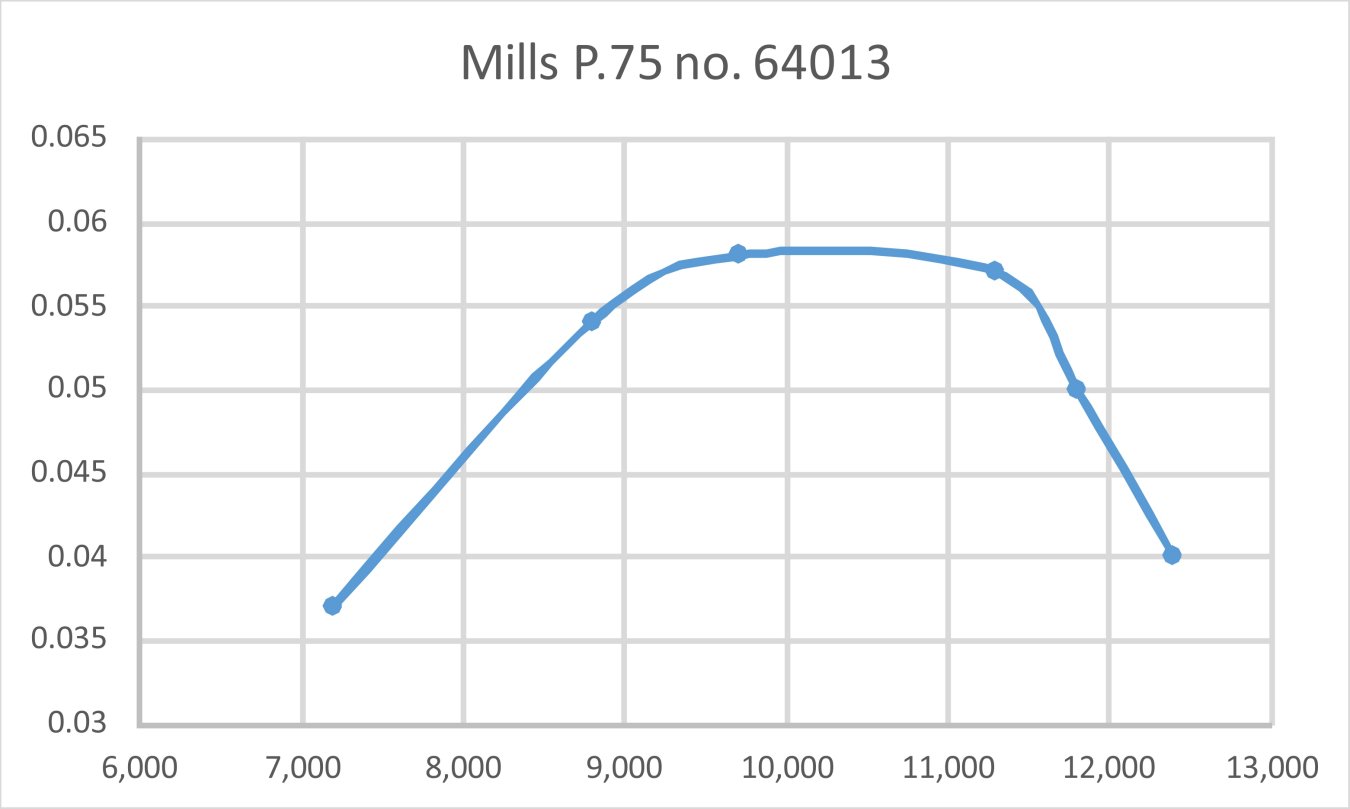

I had run this one quite a bit in the past, so it was all ready for testing with no need for any further running-in. The original Mills engines were also well-run-in, although I had not run either of them for some time. By contrast, the two NAVO models were un-run, requiring me to give them a break-in period to allow them a fair chance to show what they could really do. Not surprisingly in view of their identical designs, both of the NAVO models proved to have starting and running characteristics which very closely matched those of the original Mills engines. Once the correct settings were established, neither engine required a prime at any time, needing only a single lazy choked flick followed by one or two more vigorous flicks to start. Response to the controls was very positive, the one issue being a certain ambiguity in the optimal needle valve setting on both models which made establishing the perfect needle setting a little more tricky than expected. However, a good setting was readily established, after which running qualities were beyond reproach. The NAVO 1.3 model proved to be perfectly set up apart from needing the steel thrust washer already mentioned. However, an issue did become apparent with the .75 model which in my view should have presented itself to CS as something requiring attention. This was the fact that the minimum compression setting possible with this example of the engine proved to be marginal in terms of allowing the operator to back off compression sufficiently to clear a flooded case. On the 7x6 nylon prop used for the initial runs, the engine ran at a compression setting which was only about 1/8 of a turn above the minimum possible setting. Clearing a flooded crankcase generally requires compression to be backed off substantially more than this. Upon removing the engine from the test stand to dismantle the cylinder for a check, it turned out that the limiting factor was contact between the lower inner surface of the cylinder head and the upper edge of the contra piston. I turned some ten thou (0.25 mm) off the upper edge of the contra piston, after which things felt just fine upon reassembly, with ample scope for decreasing compression to deal with an over-wet engine. It would have been very easy for CS make their contra-pistons for this model slightly shorter to prevent this problem from occurring. It does however bear repeating that the engine started and ran well as supplied – it was only the potential need to clear a flooded crankcase that made this modification appear advisable. After sorting this issue, I put some 30 minutes on each engine, running a full tank out each time. I ran the engines slightly rich and under-compressed, but leaned out to full chat as the run neared its end, after which I allowed complete cooling before attempting a re-start. The latter step is critical to allow the piston to pass through the full-range heat cycles which are so essential to the longevity and performance of a ferrous piston/cylinder combination. A separate article on the break-in of such engines may be found elsewhere on this web-site. At the end of this treatment, both engines felt superb – quite up to genuine Mills standards, in fact. I could see little point in continuing the running-in, and therefore began preparations to undertake a comparative test using the same props and fuel. In his re-test of both the Mills P.75 and 1.3 models which appeared in the December 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”, Peter Chinn reported respective power outputs of 0.054 BHP @ 11,000 rpm and 0.114 BHP @ 11,000 rpm for the two engines. Both the reported outputs and peaking speeds were relatively high for engines of this pioneering sideport design, a tribute to the original designer’s success in matching the engine’s various cycles (induction, transfer, exhaust) to near-perfection. Given the fact that the CS NAVO models follow the Mills design pattern almost exactly in functional terms, it seemed reasonable to anticipate that they would perform at comparable levels. I selected my range of test airscrews accordingly. I began with the .75 models. The original Mills P.75 used for comparison purposes bore the serial number 64013, dating it to the middle of the Mills production run during the latter half of the 1950’s. It was used, but remained in completely original condition, with excellent fits all round.

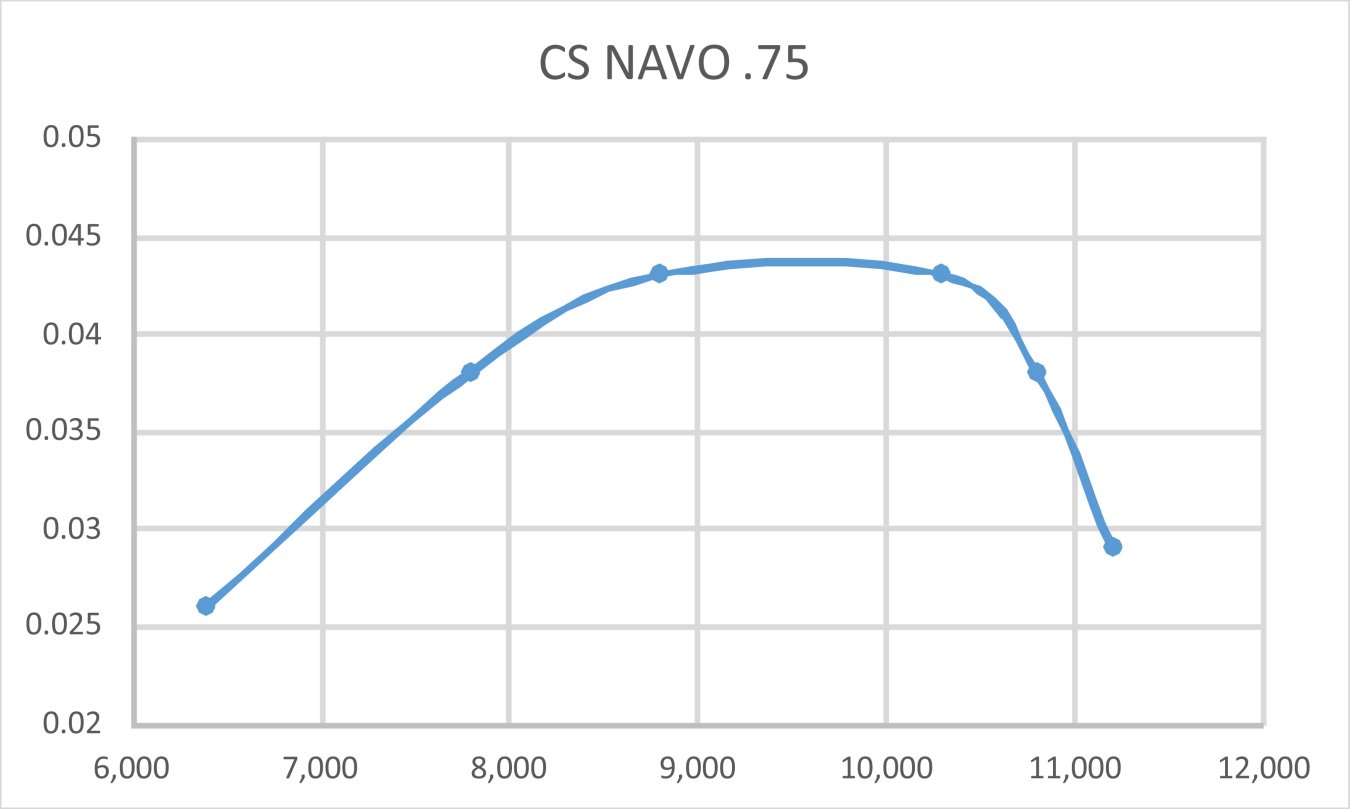

Starting hot or cold was as easy as with any full-sized engine – a choked flick to induct some fuel, followed by a single flick (in most cases) to start. Response to the controls was very positive without being in the least bit critical, while running qualities were unimpeachable. After running a set of suitable test props on the original Mills, I switched to the CS NAVO .75. This proved to be just as easy to start as the Mills original, the same technique being found to work very well. Running qualities too were just as good, the one minor fly in the ointment being the previously-noted fact that the needle setting was rather more critical, with a somewhat ambiguous response to adjustments at times. I think that a steel needle with a slightly sharper taper might work better in this instance. That said, the engine ran very well indeed once the setting was established. The compression control was very positive in action. It quickly became apparent that the CS replica was not going to equal the original Mills in performance terms. The figures in the table below tell the story.

Interestingly enough, the output measured for the original Mills P.75 actually exceeded Peter Chinn’s previously-noted figure of 0.054 BHP @ 11,000 RPM. The actual figures implied by the above results for engine number 64013 were 0.060 BHP @ 10,800 RPM, with a commendably flat peak. The corresponding figures for the NAVO were somewhat more modest – the power curve derived from the above numbers suggests an output of around 0.045 BHP @ 9,800 rpm – actually a quite reasonable figure for an engine of this type and displacement. However, the original Mills was the clear winner in this particular contest. That said, it's very likely that some more running time would improve the figures for the NAVO. It’s also worth recalling the well-established fact that the original Mills engines were well-known for displaying a considerable variation in performance between different examples of the same model. In his December 1960 double test mentioned earlier, Peter Chinn commented on this very point, stating for the record that tests on different examples of the Mills P.75 had yielded figures ranging from “less than 0.050 BHP” up to a most impressive 0.070 BHP. The figures measured for the NAVO .75 are well within sight of the lower end of this range, with a clear potential for improvement as the engine gains more running time.

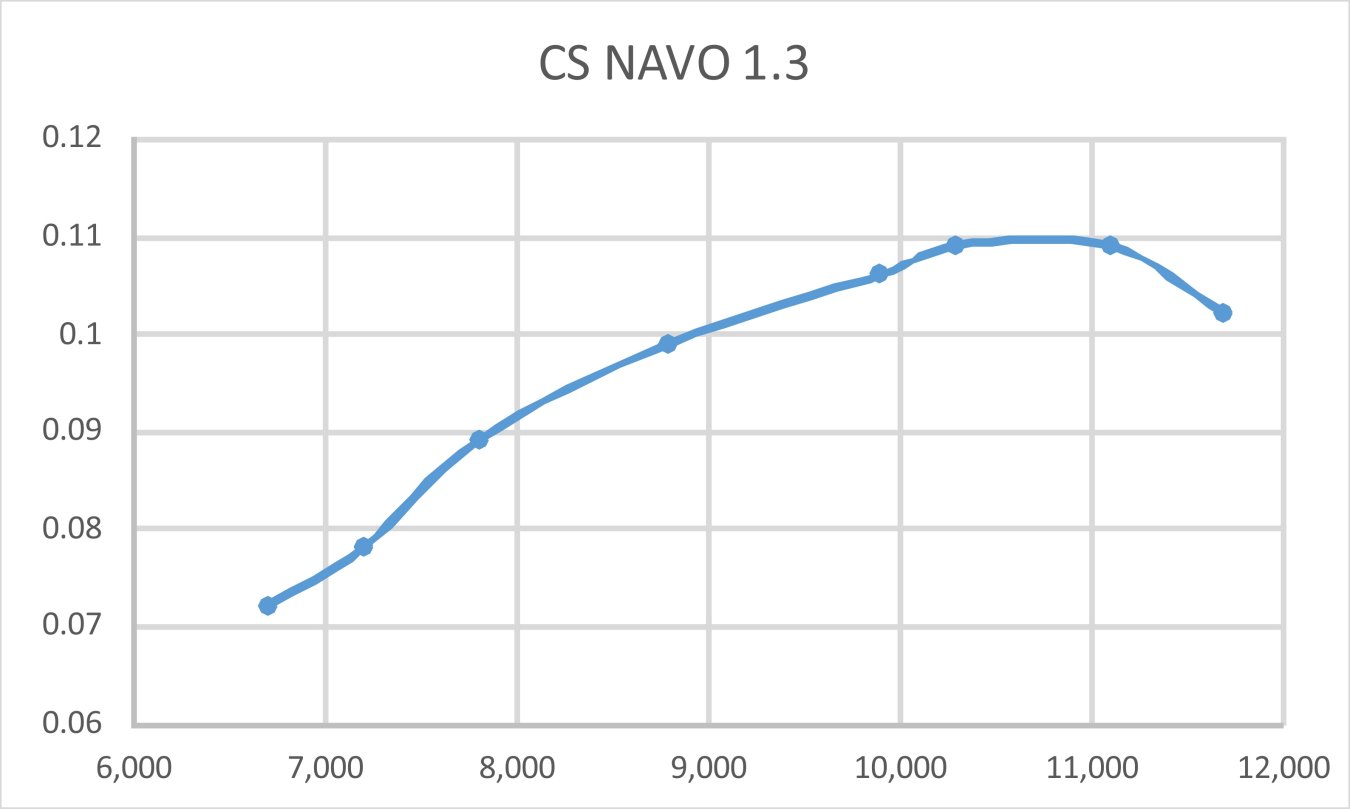

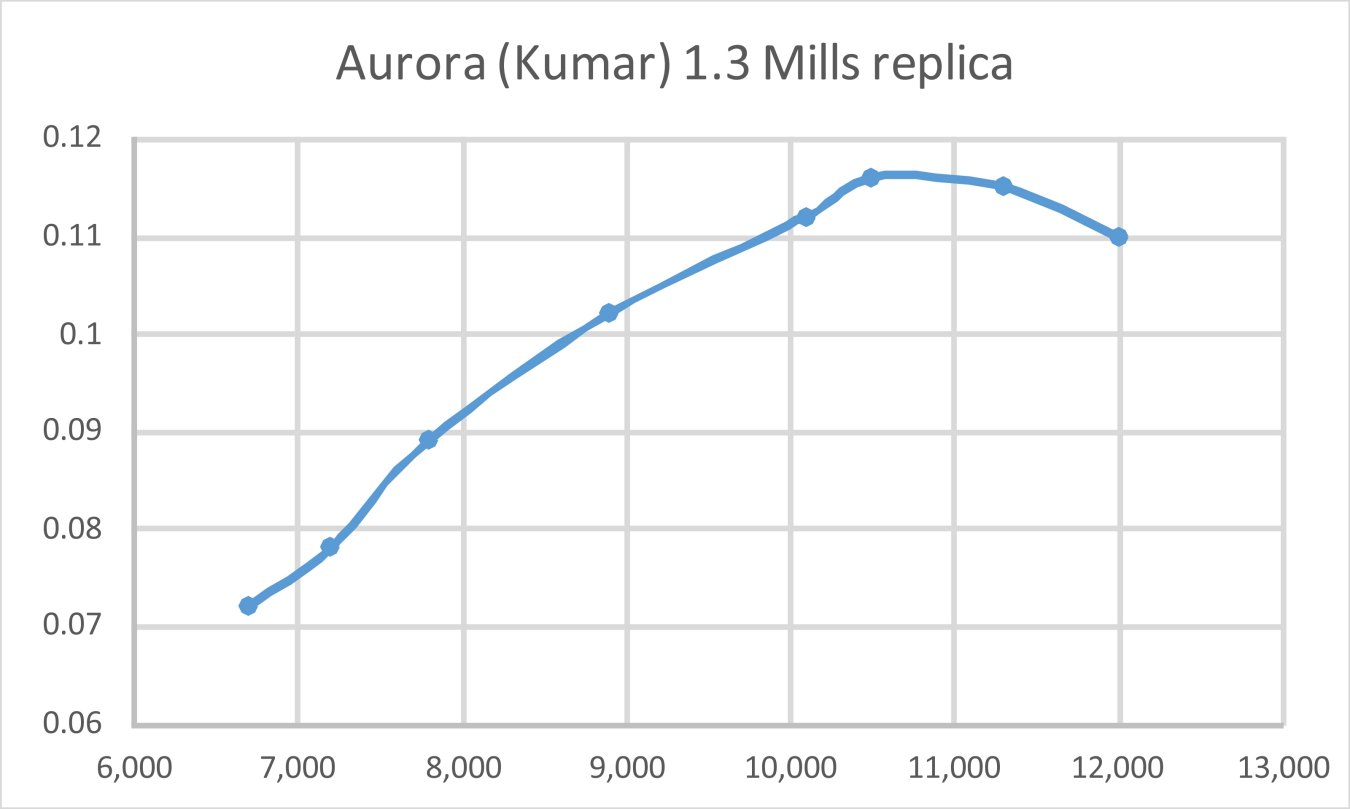

The original Mills upheld the honor of the marque splendidly, starting and running flawlessly, just like its smaller brother tested previously. I wish that all model diesels were as well-mannered as the Mills designs ……. After the original Mills had been put through its paces, it was the turn of the NAVO 1.3 and the Aurora 1.3 in succession. Both of these models started and ran like the real McCoy (or in this case, the real Mills!). Despite the rather chequered reputation that the Aurora replicas have acquired over the years, this one is superbly fitted and has survived some hours of running both on the bench and in the air. Just don’t put one of these into the ground – the un-hardened shafts tend to bend with little provocation …… The figures obtained on test for all three engines are summarized in the following table.

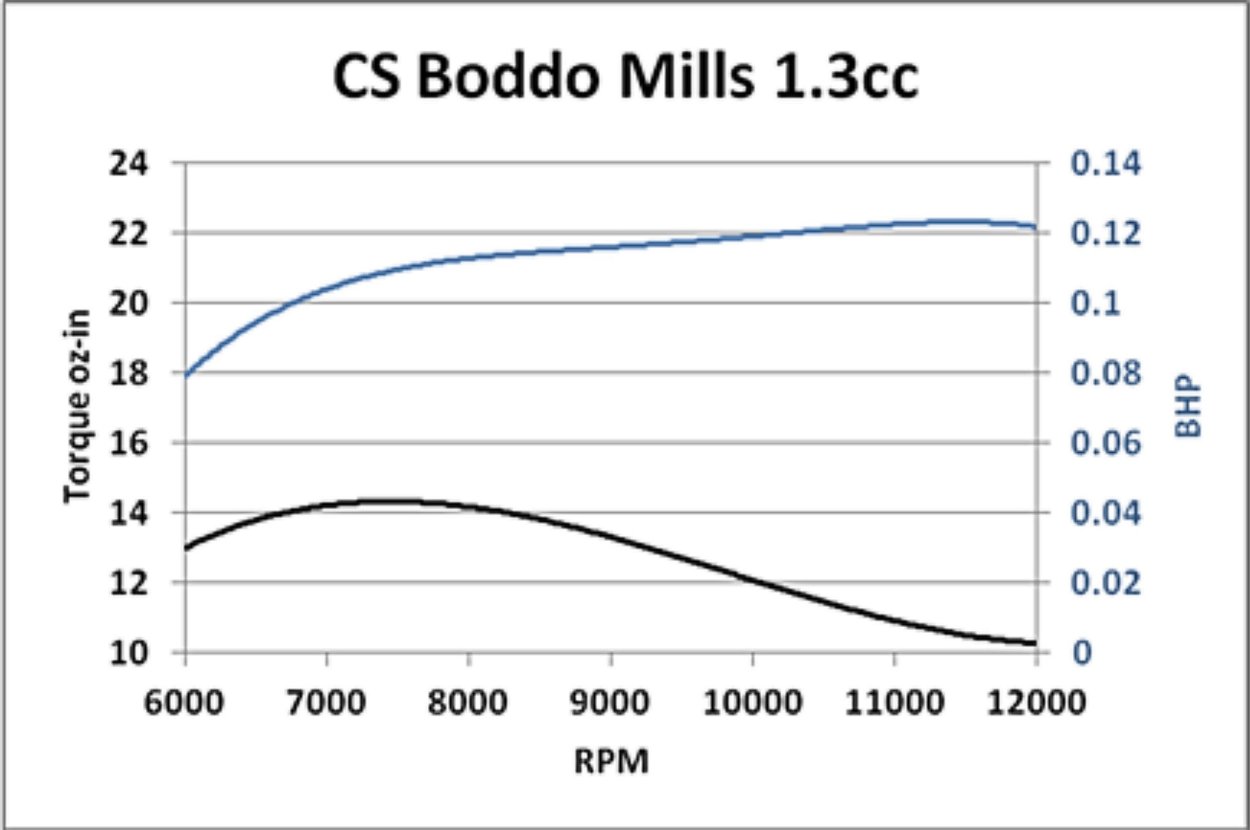

I have a sneaking suspicion that the performance of the original Mills may have been adversely affected by deposits of congealed castor oil gum in the transfer system. This is a My good Aussie mate Maris Dislers had previously run a test on Don Howie's "Boddo Mills" 1.3 replica, which is of course the same CS engine under a different name. Maris's results are reproduced below, along with my very sincere thanks. Like me, Maris found that the engine delivered an excellent performance - in fact, his results somewhat exceeded those obtained for my engine as well as those reported years ago by Peter Chinn. Some variation in performance between different examples of the same consumer-grade engine is to be expected, so no real surprises there. The important thing is that Maris's results confirm that my findings were not simply a flash in the pan - indeed, it's possible that mine is actually a sub-standard example!

Overall, both Maris and I found the CS replicas to be very practical and well-made units which provide the genuine “Mills experience” without any risk of damage to a more valuable original. A little attention to the very few details mentioned in this report, and these units become highly acceptable substitutes for the originals! Conclusion Both of the CS models covered by this test proved to deliver exactly what they claimed - a very creditable facsimile of the handling and performance of the original Mills diesels. It was particularly gratifying to see the positive results of CS’s latter-day efforts to upgrade their quality control standards. Neither of the issues noted above which merited my intervention were such as to prevent the engines from running. Indeed, both of my test examples represented excellent value for money as received despite both requiring some attention to certain details. In my view, few modellers buying one of these engines in order to experience the pleasures of Mills operation should have been disappointed. Thanks, CS, and good luck in your future endeavours!! ______________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2016 |

||||||

| |

In the first three decades following the end of the "classic" era in around 1970, the inescapable effects of supply and demand progressively tended to result in an ever-increasing imbalance between demand for and availability of certain classic model engines from among the collector and vintage aeromodelling communities. This in turn led to a significant upsurge in the production of replicas or look-alikes of some of the more highly-regarded classic model engines of yesteryear.

In the first three decades following the end of the "classic" era in around 1970, the inescapable effects of supply and demand progressively tended to result in an ever-increasing imbalance between demand for and availability of certain classic model engines from among the collector and vintage aeromodelling communities. This in turn led to a significant upsurge in the production of replicas or look-alikes of some of the more highly-regarded classic model engines of yesteryear. Following its establishment in 1978 as a manufacturer of world-class competition powerplants, the CS company went on through several ownership/management changes to become one of the world’s most prolific sources of replica and look-alike classic model engines. This being the case, it’s actually rather surprising that it took as long as it did for the Mills engines to become subject to the attentions of this manufacturer.

Following its establishment in 1978 as a manufacturer of world-class competition powerplants, the CS company went on through several ownership/management changes to become one of the world’s most prolific sources of replica and look-alike classic model engines. This being the case, it’s actually rather surprising that it took as long as it did for the Mills engines to become subject to the attentions of this manufacturer.  I accept the fact that many readers will be aware of the considerable criticism that the products of the CS company drew over the years from a quality control standpoint. While this may not have been undeserved at times, there were unmistakeable and very welcome signs during the final years that the company was making a determined and increasingly effective effort to improve its quality control standards.

I accept the fact that many readers will be aware of the considerable criticism that the products of the CS company drew over the years from a quality control standpoint. While this may not have been undeserved at times, there were unmistakeable and very welcome signs during the final years that the company was making a determined and increasingly effective effort to improve its quality control standards.  I felt quite strongly that only through the evaluation and documentation of their ongoing efforts could a basis be established for encouraging the continued support of the classic modelling community for CS’s very sincere efforts. It was always clear that without such support, the range could not survive, and indeed that’s how things eventually unfolded. In my personal view, the loss of CS was a body blow to the classic modelling movement. Another textbook case of the movement shooting itself in the foot as far as I'm concerned - the somewhat similar fate of

I felt quite strongly that only through the evaluation and documentation of their ongoing efforts could a basis be established for encouraging the continued support of the classic modelling community for CS’s very sincere efforts. It was always clear that without such support, the range could not survive, and indeed that’s how things eventually unfolded. In my personal view, the loss of CS was a body blow to the classic modelling movement. Another textbook case of the movement shooting itself in the foot as far as I'm concerned - the somewhat similar fate of  The CS Mills “look-alike” series was latterly marketed under the NAVO trade-name – the company was compelled by legal considerations to resist the temptation to cash in directly on the Mills label. In fact, the legal owners of the Mills name, the

The CS Mills “look-alike” series was latterly marketed under the NAVO trade-name – the company was compelled by legal considerations to resist the temptation to cash in directly on the Mills label. In fact, the legal owners of the Mills name, the  To begin with, the CS versions of the two engines weight more or less exactly the same as their original Mills progenitors. The NAVO .75 weighs in at 50 gm (1.76 ounces), while the 1.3 model tips the scale at 102 gm (3.60 ounces), in both cases within a couple of grams of the originals. Bore and stroke dimensions are also very similar – the respective measurements for the NAVO .75 model check out at 8.60 mm (original 8.51) and 13.00 mm (original 13.21) for a displacement of 0.75 cc, while the 1.3 model measures up at 10.25 mm (original 10.32) and 16.00 mm (original 15.87) for a displacement of 1.32 cc.

To begin with, the CS versions of the two engines weight more or less exactly the same as their original Mills progenitors. The NAVO .75 weighs in at 50 gm (1.76 ounces), while the 1.3 model tips the scale at 102 gm (3.60 ounces), in both cases within a couple of grams of the originals. Bore and stroke dimensions are also very similar – the respective measurements for the NAVO .75 model check out at 8.60 mm (original 8.51) and 13.00 mm (original 13.21) for a displacement of 0.75 cc, while the 1.3 model measures up at 10.25 mm (original 10.32) and 16.00 mm (original 15.87) for a displacement of 1.32 cc. The other obvious difference is the fact that the aluminium alloy cooling jackets of the illustrated CS models are anodized gold rather than being left in their natural state as machined. Neither cooling jacket is equipped with the compression screw stop pin which was a feature of the Mills originals – a good move in my book because that dratted pin always seemed to impose inconvenient limits upon the movement of the comp screw. Indeed, many owners of original Mills engines removed the pin for precisely this reason.

The other obvious difference is the fact that the aluminium alloy cooling jackets of the illustrated CS models are anodized gold rather than being left in their natural state as machined. Neither cooling jacket is equipped with the compression screw stop pin which was a feature of the Mills originals – a good move in my book because that dratted pin always seemed to impose inconvenient limits upon the movement of the comp screw. Indeed, many owners of original Mills engines removed the pin for precisely this reason.  In all other respects, the CS engines are essentially identical to their Mills progenitors. This extends to the porting and timing arrangements as well as the balance of the material specification. A particularly commendable point to be made here is the fact that the hole spacings in the beam mounting lugs are identical to those of the Mills originals. This means that the CS replica is interchangeable with an original in the same model. I have commented previously on several occasions regarding the desirability of this – it allows the replica to be used for everyday flying, while a more valuable original can still be mounted for display or “special occasion” use. Other manufacturers of replica engines would do well to follow suit.

In all other respects, the CS engines are essentially identical to their Mills progenitors. This extends to the porting and timing arrangements as well as the balance of the material specification. A particularly commendable point to be made here is the fact that the hole spacings in the beam mounting lugs are identical to those of the Mills originals. This means that the CS replica is interchangeable with an original in the same model. I have commented previously on several occasions regarding the desirability of this – it allows the replica to be used for everyday flying, while a more valuable original can still be mounted for display or “special occasion” use. Other manufacturers of replica engines would do well to follow suit. I also looked for any assembly issues. For the most part, both engines were correctly assembled as received. However, in keeping with my policy of honestly reporting any deficiencies, I must record the fact that the 1.3 model suffered from a problem which was actually amazingly common in the classic era, namely an excessive amount of end-float in the crankshaft assembly. The original Mills designs used steel prop drivers which keyed onto flats machined into the front end of the crankshaft main journal. Since they bore against shoulders formed in the forward end of the shaft, their axial location was fixed, thus also fixing the amount of end-float.

I also looked for any assembly issues. For the most part, both engines were correctly assembled as received. However, in keeping with my policy of honestly reporting any deficiencies, I must record the fact that the 1.3 model suffered from a problem which was actually amazingly common in the classic era, namely an excessive amount of end-float in the crankshaft assembly. The original Mills designs used steel prop drivers which keyed onto flats machined into the front end of the crankshaft main journal. Since they bore against shoulders formed in the forward end of the shaft, their axial location was fixed, thus also fixing the amount of end-float. Just for fun, I also dusted off my example of the Indian-made

Just for fun, I also dusted off my example of the Indian-made

The original Mills P.75 model was first into the test stand. Every time I treat myself to a running session using one of the Mills engines, I am reminded once again of the immense debt of gratitude that all model diesel aficionados owe to the designers and manufacturers of these engines. The fact that they appeared relatively early on in the history of the post-war model diesel and were produced in substantial numbers, hence achieving wide circulation quite rapidly, must have done wonders for the establishment of the very positive view which the majority of British and Commonwealth modellers quickly formed of the model diesel. They were perfect ambassadors for this then-new type of engine.

The original Mills P.75 model was first into the test stand. Every time I treat myself to a running session using one of the Mills engines, I am reminded once again of the immense debt of gratitude that all model diesel aficionados owe to the designers and manufacturers of these engines. The fact that they appeared relatively early on in the history of the post-war model diesel and were produced in substantial numbers, hence achieving wide circulation quite rapidly, must have done wonders for the establishment of the very positive view which the majority of British and Commonwealth modellers quickly formed of the model diesel. They were perfect ambassadors for this then-new type of engine.

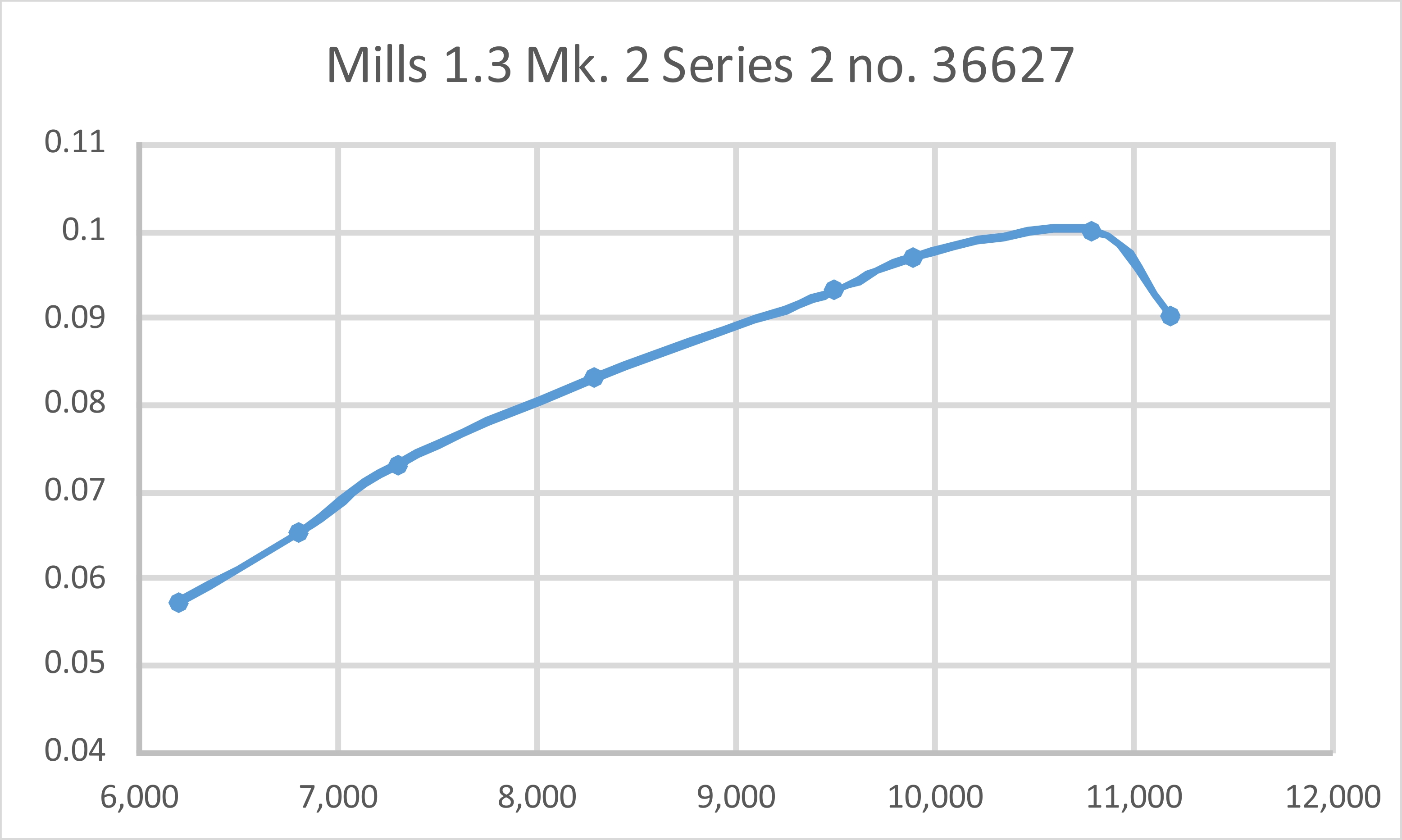

After this, it was the turn of the various 1.3 models. The original example used as a bench-mark bore the serial number 36627, making it a relatively late example of the engine, probably dating from the early 1960’s. Like its smaller sibling tested earlier, it had received a certain amount of previous use but remained in perfect original condition.

After this, it was the turn of the various 1.3 models. The original example used as a bench-mark bore the serial number 36627, making it a relatively late example of the engine, probably dating from the early 1960’s. Like its smaller sibling tested earlier, it had received a certain amount of previous use but remained in perfect original condition.

These results turned the tables with a vengeance! As can readily be seen, the two replicas both handily out-performed the original Mills model across the entire tested speed range. The Aurora unit actually beat Chinn’s December 1960 figures by recording a peak output of around 0.118 BHP @ 10,800 rpm, while the CS NAVO 1.3 came close to duplicating Chinn’s results with a measured peak of around 0.111 BHP @ 10,800 rpm. Both sets of figures are outstanding for simple long-stroke sideport engines like these. The original Mills example was Tail-End Charlie in this instance, managing a peak of only some 0.100 BHP @ 10,800 rpm. It is however really noteworthy that all three engines peaked at exactly the same speed. A certain degree of design consistency at work there ……….

These results turned the tables with a vengeance! As can readily be seen, the two replicas both handily out-performed the original Mills model across the entire tested speed range. The Aurora unit actually beat Chinn’s December 1960 figures by recording a peak output of around 0.118 BHP @ 10,800 rpm, while the CS NAVO 1.3 came close to duplicating Chinn’s results with a measured peak of around 0.111 BHP @ 10,800 rpm. Both sets of figures are outstanding for simple long-stroke sideport engines like these. The original Mills example was Tail-End Charlie in this instance, managing a peak of only some 0.100 BHP @ 10,800 rpm. It is however really noteworthy that all three engines peaked at exactly the same speed. A certain degree of design consistency at work there ……….