|

|

An Under-Appreciated Venture - Dunham Engineering

Before we commence our review of Dunham’s activities, it’s important to recognize our sources. First and foremost among these was Dunham’s former American distributor and my late valued friend and colleague Bert Streigler (yes, the guy who designed "Ebeneezer"!), who was good enough to respond directly to a number of information requests during the initial research for this article in early 2014. In addition, Bert had previously recorded his highly authoritative recollections of the Dunham range in 1997 in the pages of the now-defunct magazine “Model Engine World” (MEW), then edited by John Goodall. Bert’s recollections thus remain available to us today. A number of useful comments on the Dunham engines by John Goodall himself were also preserved in the pages of MEW. Considerable assistance was provided by Dunham’s former Australian distributor, the late David Owen. In addition, Dunham owner David Zwolak provided a wealth of information relating to the Dunham Elfin replicas, while my good mate Mike Conner made available a seemingly anomalous example of the Dunham Elfin which did much to inform my research. Ken Croft was also kind enough to provide both comments and images. Sincere thanks are due to all of these gentlemen for their respective roles in preserving much of the following information for the benefit of later researchers. Now let’s begin by taking a look at the evolution of the market niche which Dunham set out to occupy.

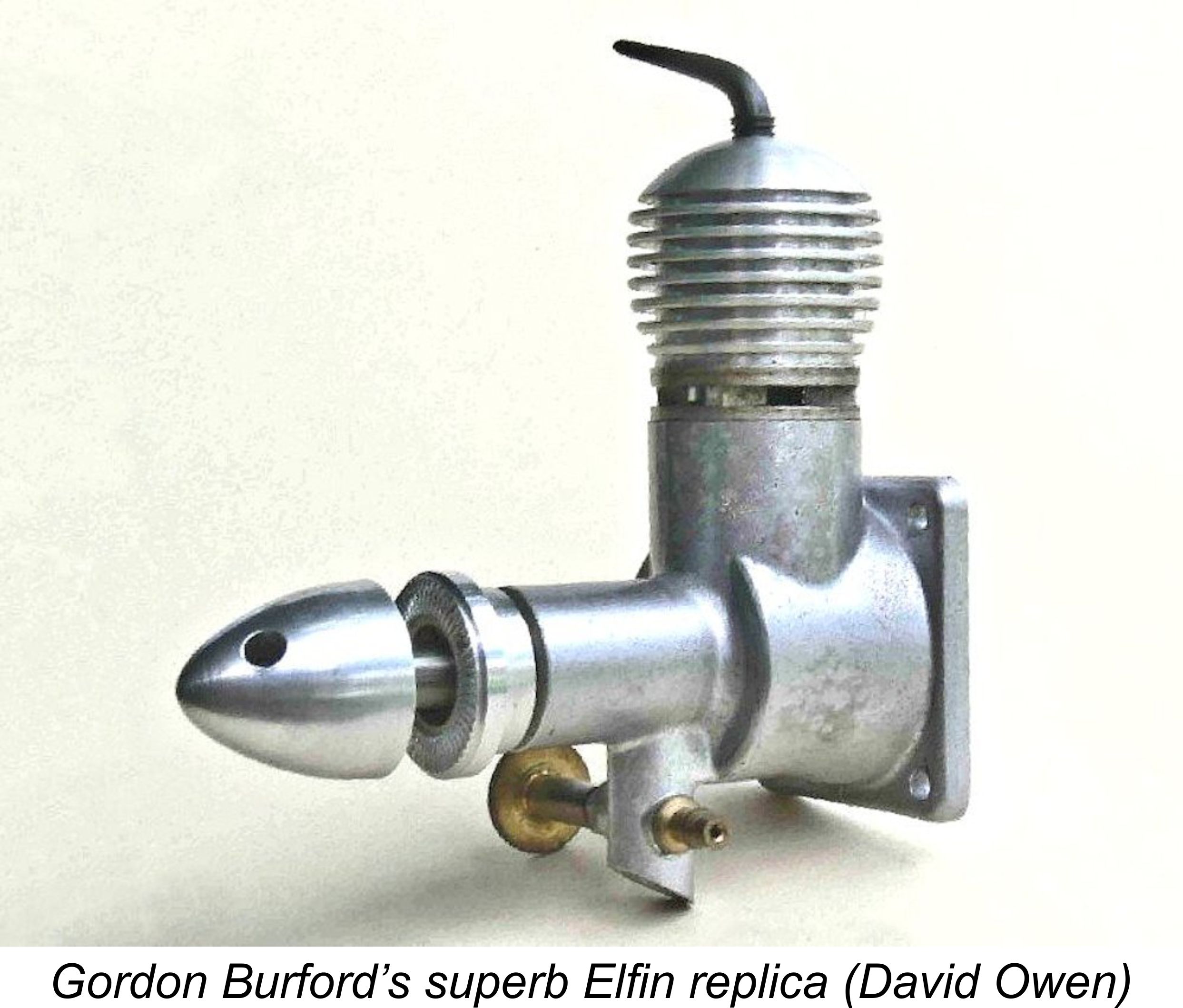

As of the early 1980’s when Dunham Engineering became involved, the production of replicas of model engines by someone other than their original manufacturer was by no means new. In fact, it went back at least as far as the early post-WW2 era, and possibly even further. The pioneering Swiss Dyno diesel of 1941 was widely copied in Europe and elsewhere even during the war years once details of its design became available. Another notable example to which David Owen has drawn attention was the Swiss-made Fischer Castor 2.5 cc model of 1951. This was a very successful close copy of the Elfin 2.49 cc radial-mount model which was later to receive the replica treatment from our subject company, Dunham Engineering. The superb Swiss-made AMRO 10 cc copy of the Dooling 61 is another well-known early example. From the late 1940’s through the 1950’s, Gordon Burford of Australia made a number of engines which, while not marketed as replicas, were very strongly influenced by overseas originals. Another well-known example from 1957 was the Russian-made MD-5 Kometa glow-plug motor, which was a near-clone of the contemporary Super Tigre G21/29 racing model. The full story of the MD-5 Kometa may be found in a separate article on this web-site. The Russians also produced close copies of other well-known competition engines such as the Webra Mach I, the Super Tigre G20/15, the Now it's important to understand that the distinction between these and later replicas was their purpose. They were not replicas of out-of-production models - on the contrary, at the time of their introduction the engines on which they were based were still readily available from their original manufacturers in their countries of origin, or at least still in widespread use and circulation. Hence these early replicas were not produced to satisfy collectors or to comply with rules for a “period” competition of some kind. Their purpose was simply to make certain current engines (or more precisely, copies thereof) more readily available in countries to which the original manufacturers did not or could not export their products directly. If an original was not obtainable, a replica would do! In a very real sense, the appearance of such replicas was a high compliment to the reputations of their original designers - only the better and hence more desirable engines received the replica treatment.

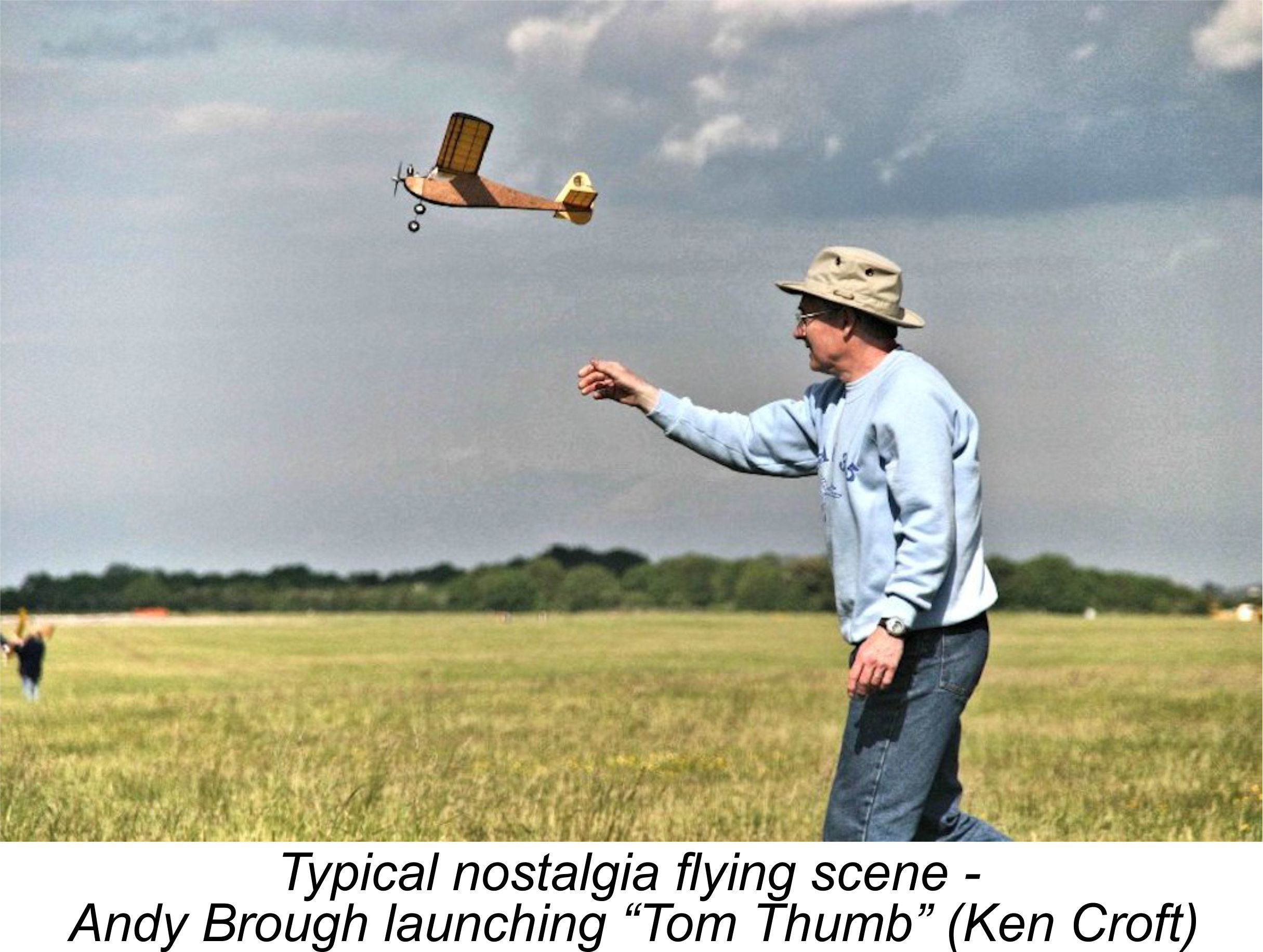

This in turn led to the development of two parallel albeit closely-related movements. One was the rise of engine collecting as a recognized activity among those for whom the engines themselves had always constituted a primary focus of interest. I confess to being largely in that camp myself, although my interests go well beyond mere collecting into the pursuit of historical research along with the experience of actually running and flying these engines. A row of engines of unknown provenance quietly aging in a display case does little for me …………. if that was all there was to collecting, I’d be long gone! The other parallel factor was a rising interest in nostalgia flying. This involved the building and flying of models which Although quite a few individuals had their feet firmly planted in both camps simultaneously, a certain degree of competition between these two movements was of course inevitable. Both groups sought original engines either to display in their collections or to use in “period” models (or in some cases both). However, the pure collectors developed a marked tendency to hoard their acquisitions, the result being that the majority of engines which ended up in collections were effectively removed from circulation. This of course reduced the availability of such engines, thus creating supply difficulties both for the flying community and the growing ranks of collectors. Since the supply was finite given the fact that production of the engines in question had long ceased, this led to a steady rise in the selling prices of good examples of earlier engines, particular the less common examples.

The overall result was that for a while the supply of original or well-restored examples of many engines actually increased or at least held steady. However, the ever-growing demand meant that this situation could not last. Many of the better original or well-restored “recovered” examples of the more desirable or less common engines were soon absorbed in turn into the collecting and vintage flying communities, once again severely limiting the remaining numbers in circulation and thus placing further upward pressure upon prices. This steady rise in prices led inexorably to the development of a further problem. Over time, even many of those individuals who had acquired such engines with the sincere intention of using them for flying purposes became increasingly reluctant to do so given the monetary value and replacement difficulties associated with the engines in question. For such individuals, a replica of their engine offered a viable and practical alternative to risking an original, as well as potentially permitting their original engines to be sold to the collector community to finance further modelling activities. Through the resulting steady process of transference from the flying to the collector communities, the availability of many engines continued to become even further restricted. Indeed, it was not only the flying community which suffered from the effects of this process - there were many latecomers to the collecting hobby who wished to acquire examples of certain engines for display or bench-running purposes but could not afford or even locate an original. Basically, the ever-growing demand had finally overtaken the limits of supply once and for all. This being the case, for these individuals too a replica was undoubtedly the next best thing. In this manner, increasing numbers of both engine collectors and vintage fliers became potential customers for replica engines. Under these circumstances, it was inevitable that the production of such replicas would enjoy a renaissance. Indeed, it was only the development of this situation that made the quantity production of replicas an economically feasible proposition. The development of the replica market had another often-overlooked benefit - the fact that it provided model engine aficionados of all stamps with an affordable alternative to the purchase of an original had the effect of applying the brakes to further price increases of said originals, to some extent at least. While some serious collectors continued to seek originals for which they were prepared to pay, the combined competition from less serious (or less well-heeled!) collectors and the nostalgia flying community was significantly decreased. Given some of the truly absurd prices which prevailed for some time, this has to be viewed positively by anyone who (like me) cares about the future of model engine collecting and the preservation of the engines themselves. It must surely be obvious that the hobby of engine collecting (and hence the preservation of these engines) can only be sustained in the long term if prices remain within rational limits. The present (2015) decrease in selling prices on eBay and elsewhere speaks very clearly to this viewpoint - far from being the disaster as which some investment-minded collectors seem to see it, it is in fact nothing more than a rational readjustment of the market to reflect present-day economic realities, and one which may help to sustain the long-term future of model engine collecting. One of the first manufacturers to recognize this developing situation and attempt to take advantage of it was our subject company Dunham Engineering of Wigan, England. Let’s now turn our attention to the activities of that company. Establishment of the Company

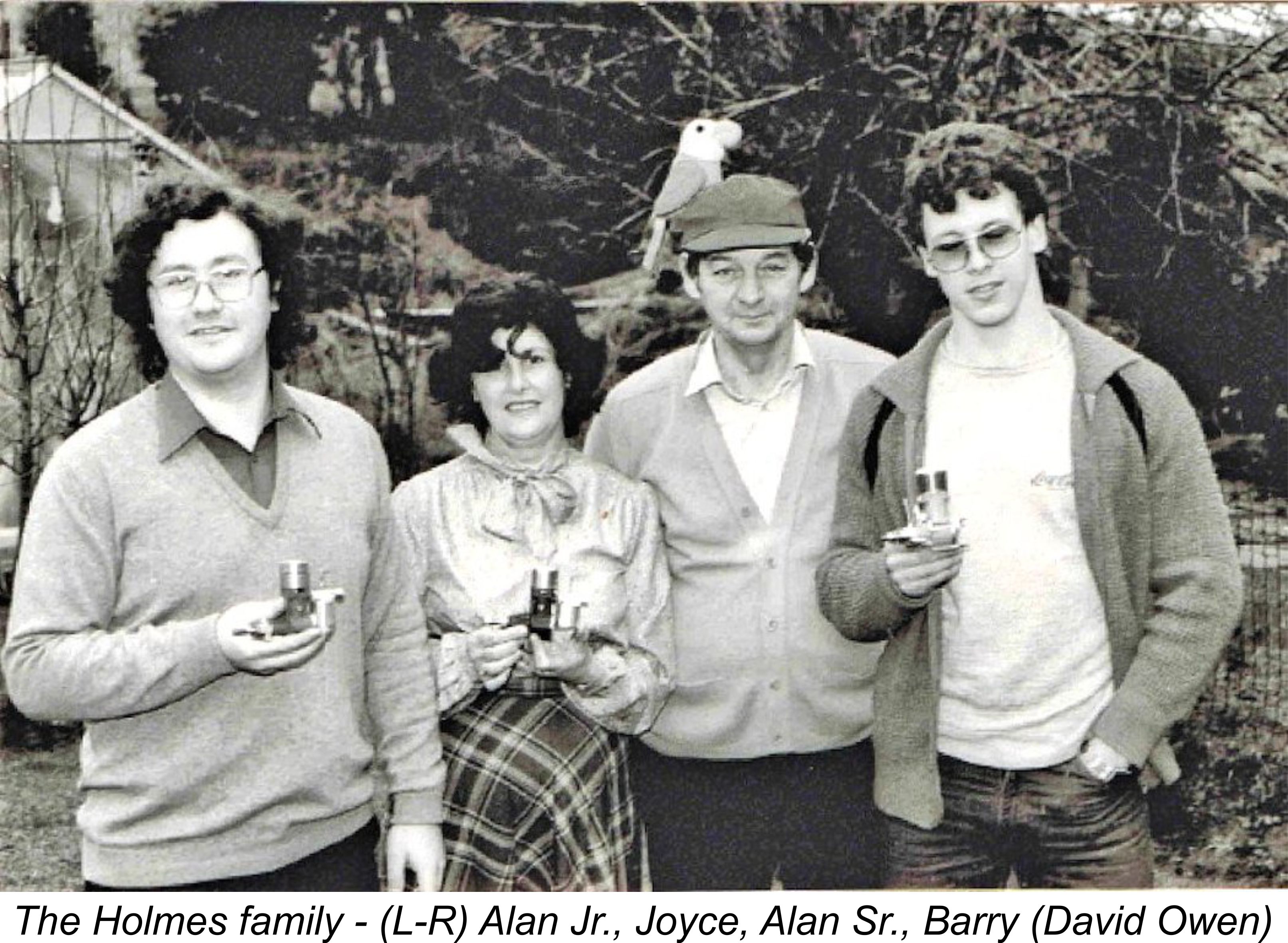

Orrell is a former industrial and coal mining community lying some 3 miles to the west of Wigan itself, although it is now in effect a residential suburb of Wigan, which has itself evolved from a separate town into a Metropolitan Borough of Greater Manchester. Orrell displays little evidence today of its industrial past, being primarily a bedroom community. It appears that the company was established at the outset to service the agricultural industry by supplying spare parts and undertaking repairs. However, the members of the Holmes family were all keen vintage model fliers. Recognizing the factors discussed above which had combined to make the acquisition of original vintage engines problematic for flying purposes, they evidently reasoned that a sincere attempt to create a range of high-quality replicas or retros would be well supported by their fellow British vintage enthusiasts. A somewhat optimistic assumption as events were to prove …………….. The fact that the company name bore no apparent relationship to that of the family which owned it might be taken to suggest that the Holmes family bought an already-existing precision engineering business bearing the Dunham name. However, the fact that the manufacturing all took place at the family residence has always argued strongly against this. In reality, the origin of the name was far more of a family "in-joke" than anything else! Reader Simon Bennett of Portland, Oregon was kind enough to contact me to shed light upon this matter. Prior to relocating to the USA, Simon was a resident of Wigan in England. He was a long-time friend of Barry Holmes, hence having had the opportunity to learn about the Dunham venture at first hand. He recalls asking Barry about the origin of the Dunham name. Barry told Simon that the name came about as a result of the habit of members of this passionately productive family using the expression "Done 'em!" when reporting on the status of a completed task. "Done 'em" rendered in a Lancashire accent sounds very much like "Dunham", hence the name selected for the venture. From the outset, the company’s design policy was to keep their replicas as true to the originals as possible while not replicating and thus perpetuating any obvious design faults. In keeping with this very rational philosophy, their engines displayed a number of design improvements over the originals, while recognizably retaining the character of those models.

By 1984 the move to all in-house manufacturing appears to have been complete. The late former Australian Dunham distributor David Owen visited Dunham Engineering in 1984, as did the late Bert Streigler a year later. At the time of both visits they were operating from a number of small workshops located in the back yard of the family residence at the Orrell address given earlier. Reportedly, Alan Sr. did most of the basic machining, while Alan Jr. made the various electrical components in addition to helping his father with the machining. Barry carried out the bulk of the cylinder grinding and lapping. Model engine manufacture commenced in March 1981. The first model offered was the Mechanair replica, of The firm also offered spark ignition conversions for many of the popular glow-plug engines of the period, including several four-strokes. This led directly to the broadening of their range of products to encompass such items as clips, high tension leads, condensers and coils, including a very highly-regarded twin coil. Dunham Engineering also cooperated with other replica manufacturers such as Attachport of Leicester on the basis of providing mutual assistance through the application of equipment and expertise to the other party’s needs which could not be met in-house. Examples include the Attachport replica Mills Mk. I and the Attachport replica K Hawk 0.25 cc, both of which benefited from some level of involvement on the part of Dunham Engineering. Let’s take a quick look at the main products developed and in most cases marketed over the years by Dunham Engineering.

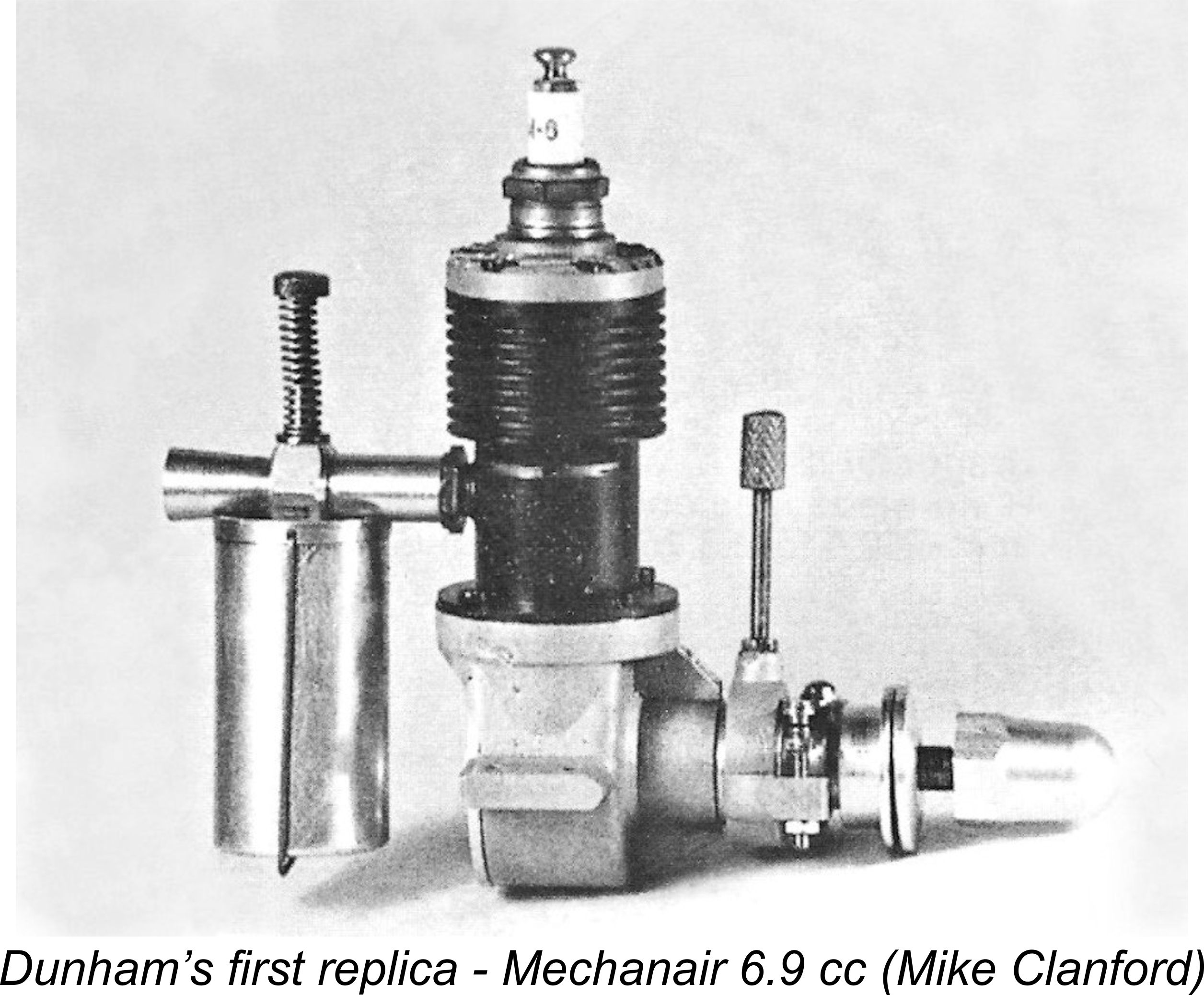

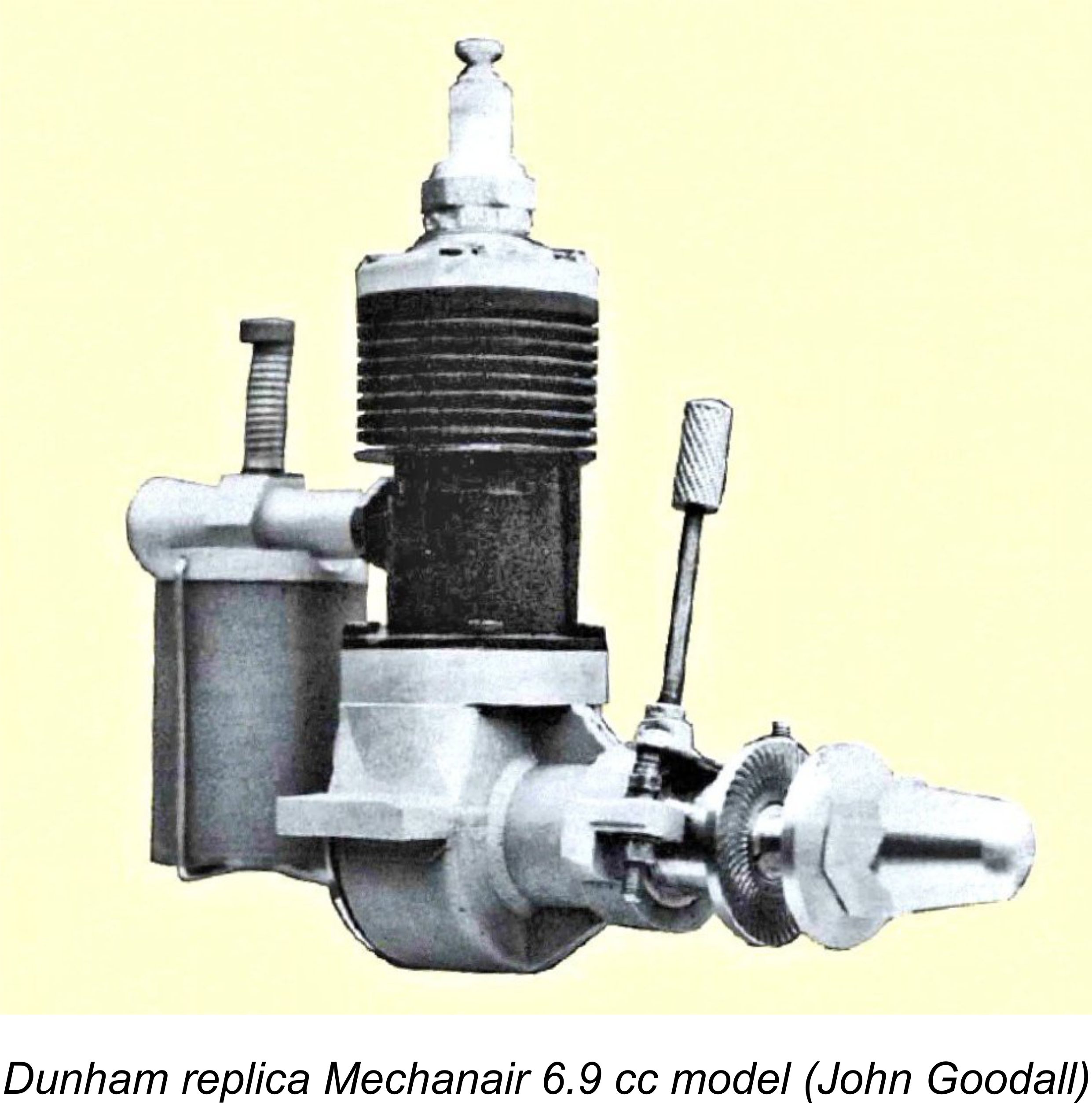

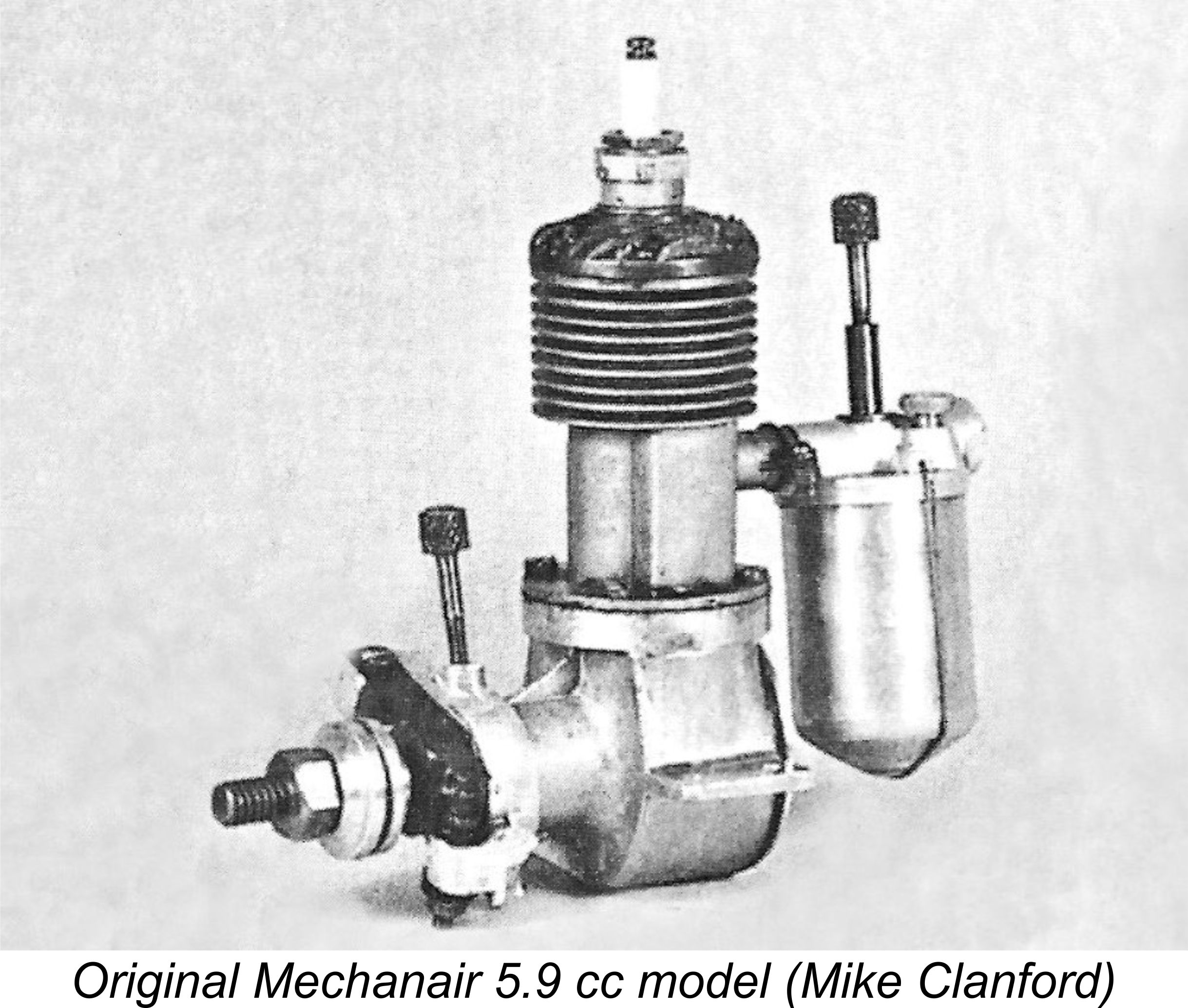

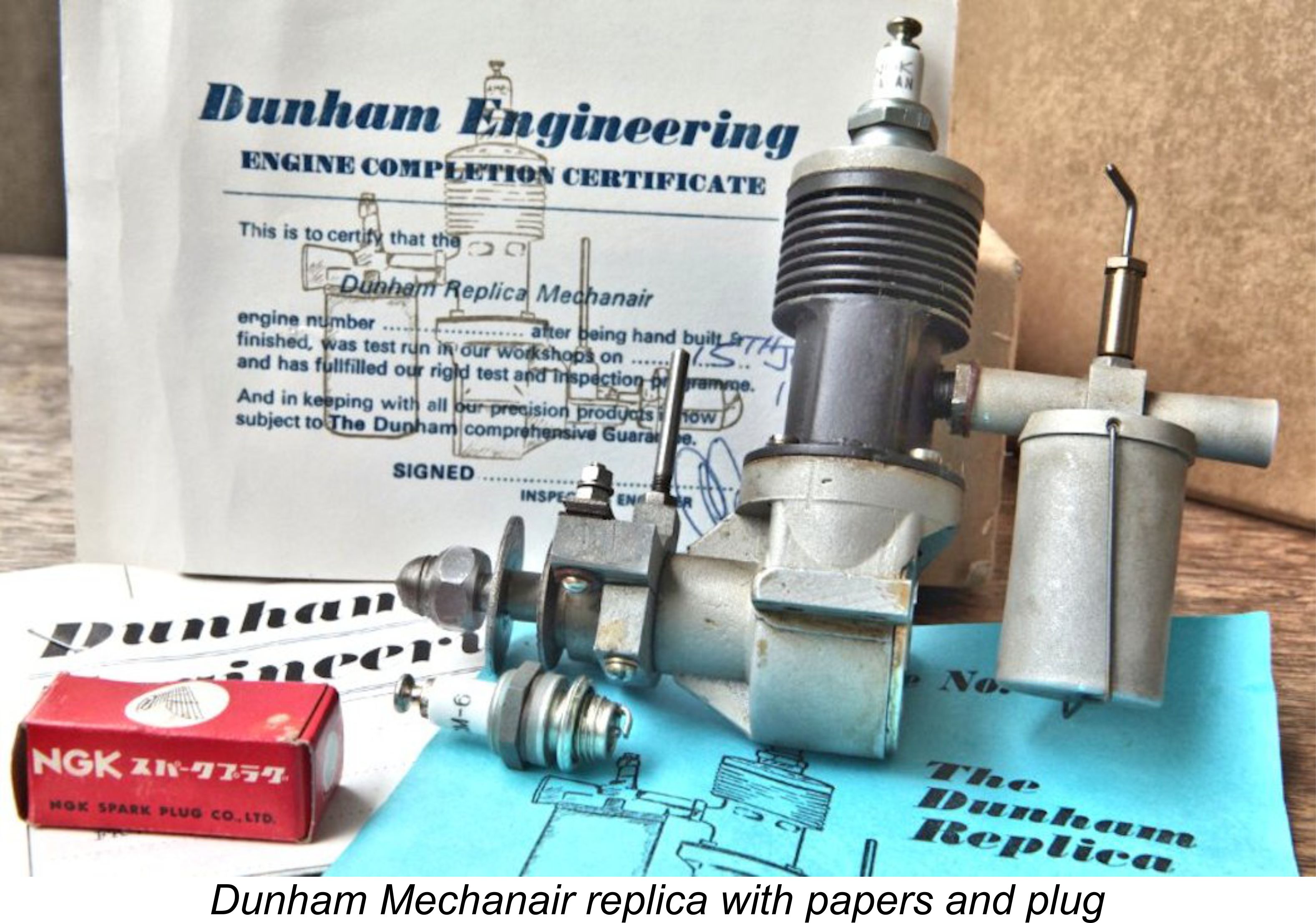

This was the first replica model engine produced by Dunham Engineering beginning in March 1981. It was based upon the 5.9 cc Mechanair design of the mid to late 1940’s. This in turn was a development of the Astral model marketed during the early post-war period by the Astral Model Aero Company of Leeds, which had entered the kit market in 1939 and added the Astral model engine to their range following the end of the war in 1945. Astral’s model engine manufacturing arm was soon taken over by Mechanair Ltd. of Birmingham, who may have been the actual manufacturers of the Astral model all along. They revised the Astral design somewhat, putting the resulting Mechanair model into production in 1946. It’s estimated that perhaps 700 or so examples of the Mechanair were produced between 1946 and 1949. The Dunham “replica” differed sufficiently from the original that it may perhaps be more properly referred to as a look-alike than a true replica. For one thing, the Less controversially, the crankcase configuration and material specification were both revised to improve the strength of the rather marginal engine mounting lugs. Both the cylinder and crankshaft were made of EN24 nickel steel, while the piston was of fine-grained cast iron. The con-rod was of heat-extruded aluminium alloy - again, an improvement over the original in terms of dependability. Few people quarrelled with changes of this nature made in the interests of enhanced durability. The resulting engine was a fine-running Mechanair look-alike with levels of both performance and durability which were markedly superior to those of the originals. The Dunham Despite its many fine qualities, this model did not prove to be a strong seller. This was likely due in large part to the significant departures from the original, which called into question the engine’s right to be called a replica as such. The relatively low sales figures achieved suggest that this may have scared off a fair number of potential customers. As far as Bert Streigler could recall, around 75 examples of the Mechanair replica were sold in total in the USA. This was at least half the total, since Alan Holmes later recalled that overall production did not exceed 150 units. The number of examples sold as kits and subsequently completed by their owners is unknown. The Dunham Mechanair saga highlights a recurring problem (if we can call it that!) with replica engines. This is their tendency to quickly become viewed as collector’s items in their own right, with a consequent strong discouragement to their use for actual flying, followed by their semi-permanent disappearance into people’s collections. The Dunham Mechanair is a case in point - far fewer of the replicas were made than the originals! Consequently, the engine quickly became viewed as a highly desirable collectible in its own right. As a result, it’s doubtful that many of them ever got used for actual flying purposes, which rather sidestepped the manufacturers’ intent in offering them in the first place ……….. Oliver Battleaxe Diesel

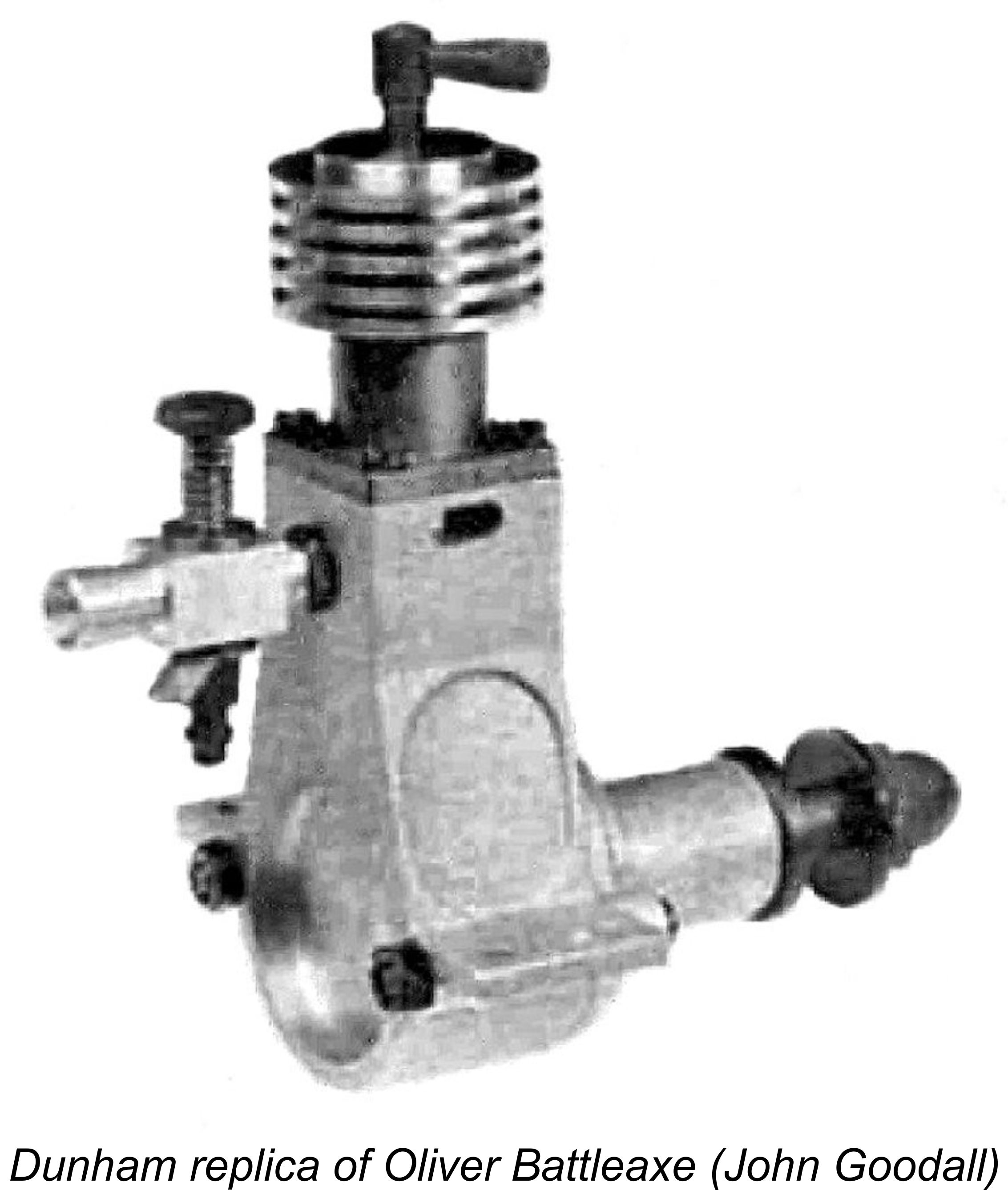

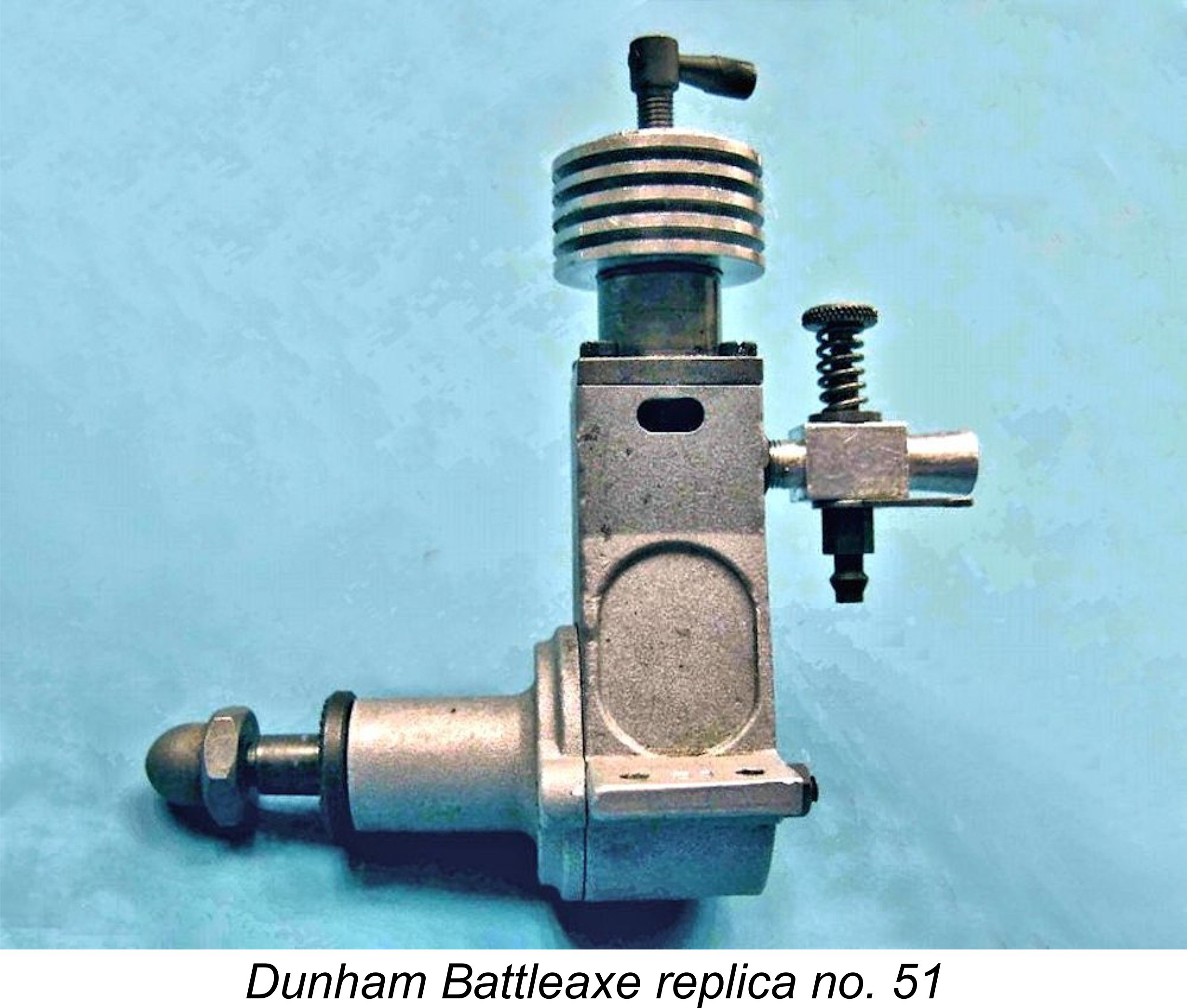

The Dunham Battleaxe was not so much a replica as an authorized reproduction, being entirely faithful to the originals in all respects. Most had a matte aluminium finish to their cases, but a few were finished in black crackle paint. The latter engines for the most part were a tuned-up “Comp Special” version of the engine which had a somewhat higher performance. At least two Two examples of a prototype Battleaxe 4 cc twin were also constructed, along with the issuance of an invitation for the submission of advance orders. For some unaccountable reason very few such orders were received, resulting in the twin not entering production. This was a classic example of the indifference displayed by all too many British vintage enthusiasts to the very sincere efforts of Dunham Engineering, a factor which had much to do with their eventual abandonment of the field. Opportunity lost indeed ……….

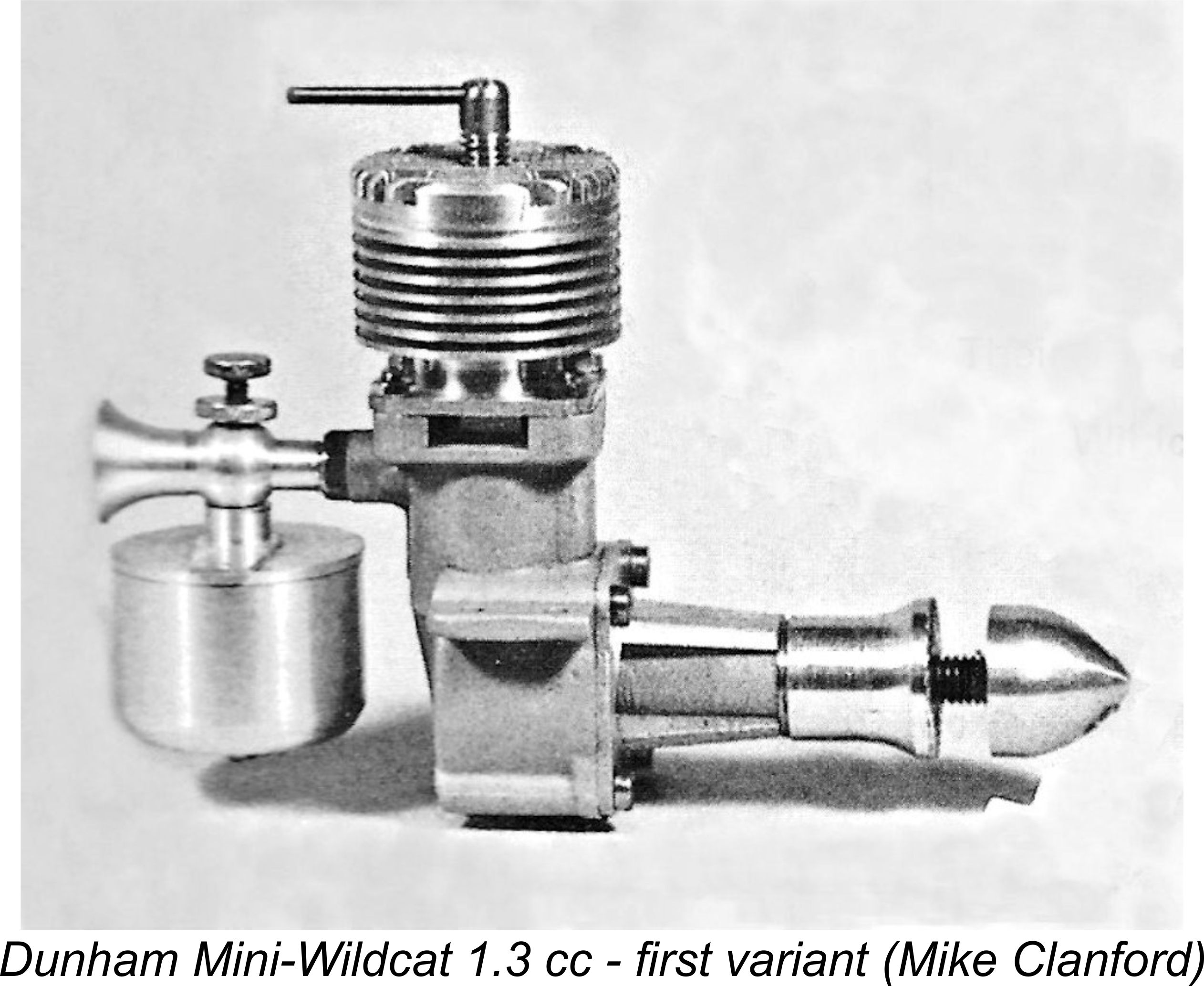

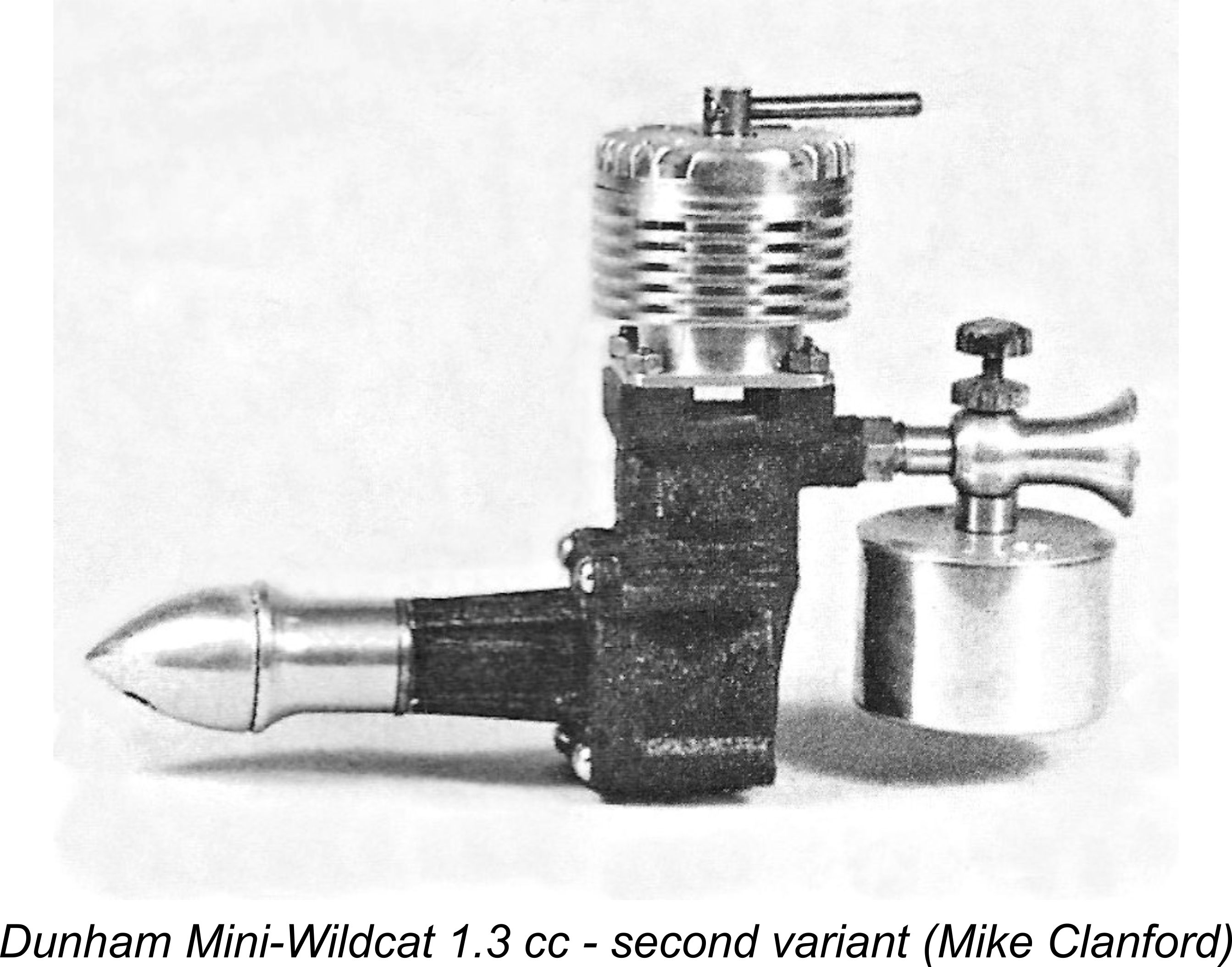

Regardless, the number produced was not large. Consequently, this is a very rare and highly collectible model today. The twin is even more exclusive, being effectively in the “unobtanium” category. Davies-Charlton Mini-Wildcat Diesel Dunham Engineering produced two prototype examples of a beautiful little ¼ sized 1.3 cc miniature Davies-Charlton Wildcat sideport diesel. One featured a matte aluminium case, while the The intention at the outset was to put this model into production, but unfortunately it proved impossible to secure the agreement of the Davies family to do this without payment of an exorbitant Whatever the facts, the net result was that this wonderful little engine never entered production. This was a great pity - this little gem would doubtless have found quite a few buyers.

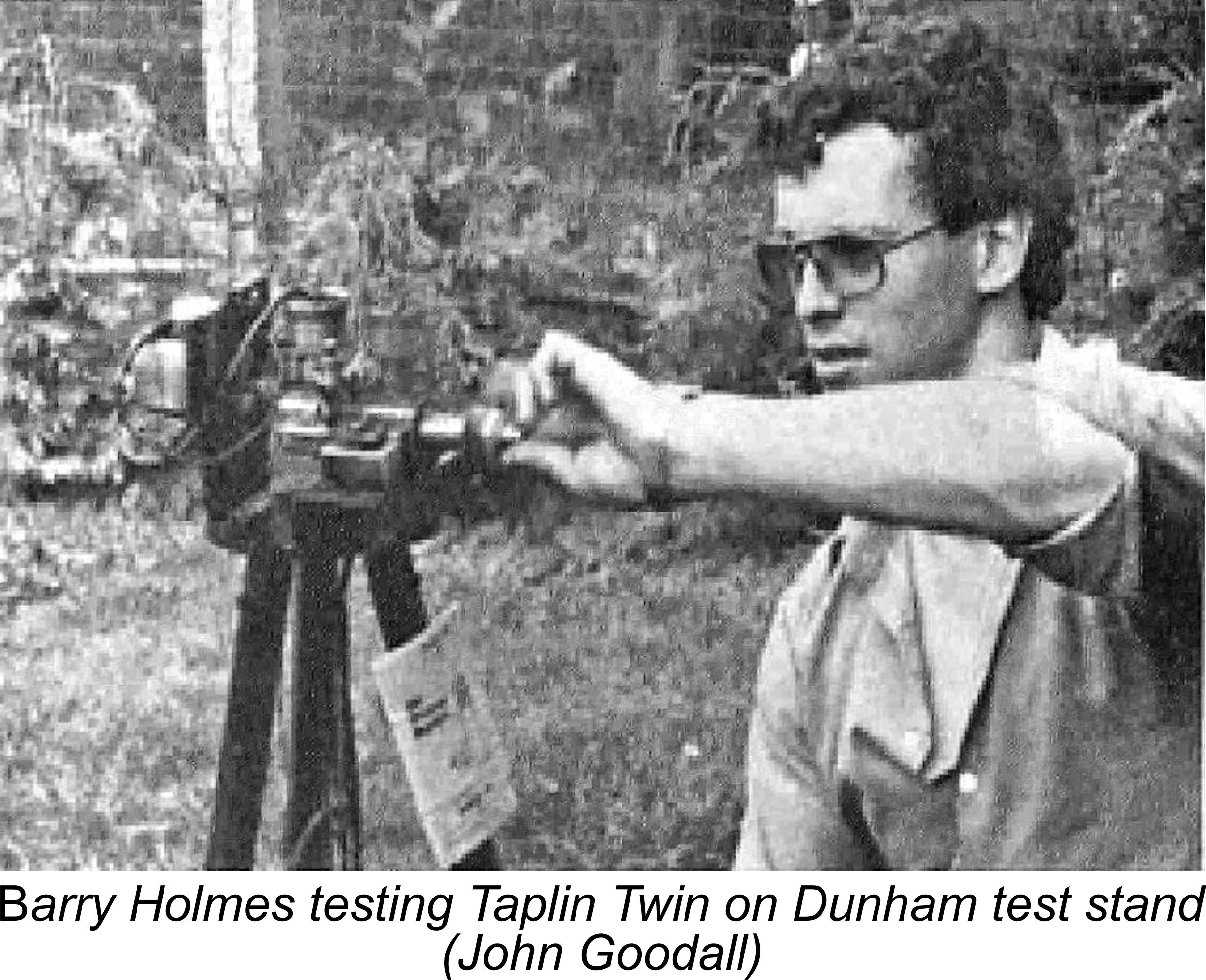

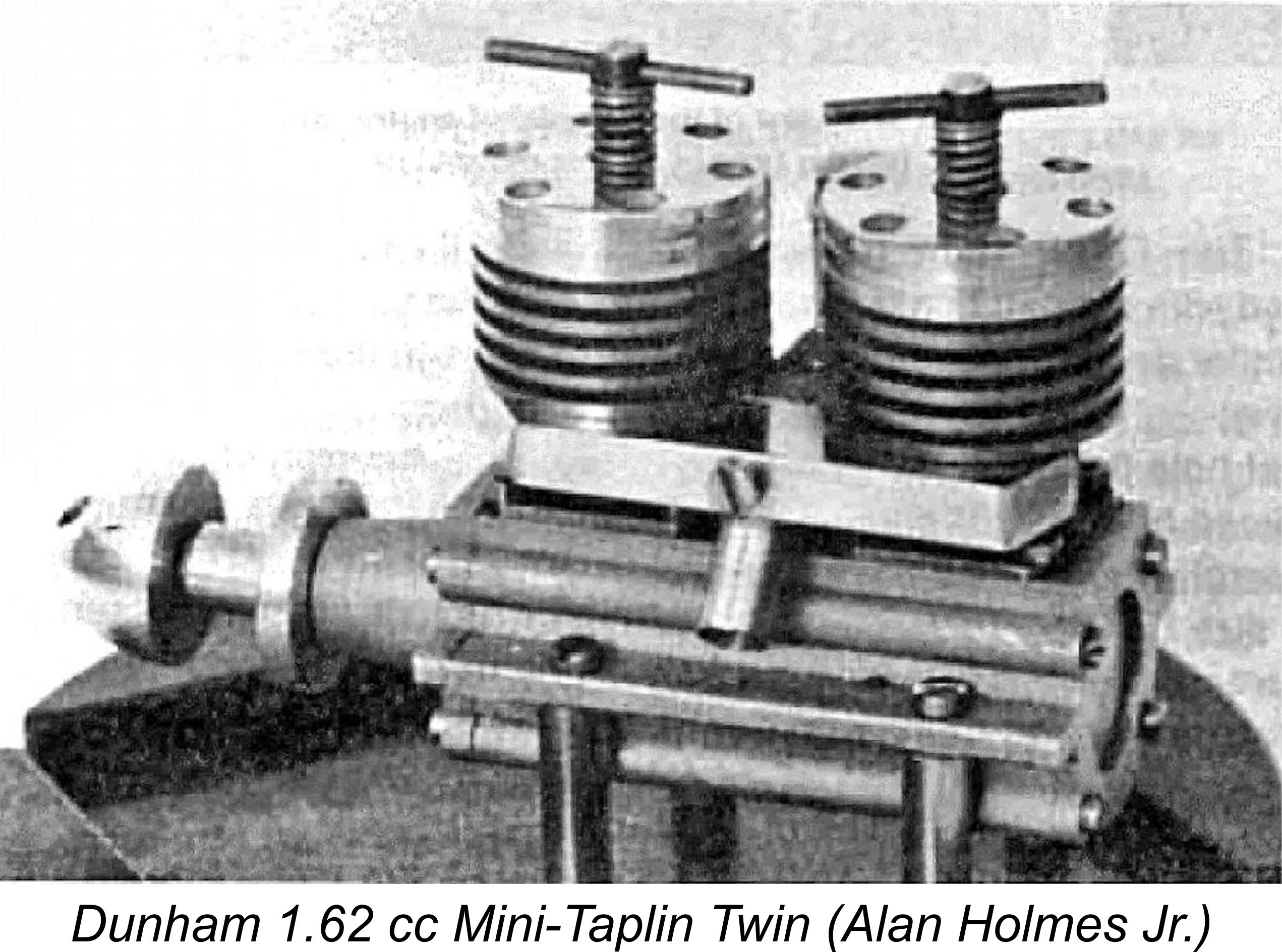

Another fascinating design that sadly failed to make it into production was the mini Taplin Twin of only 1.62 cc total displacement. Two prototypes of this proposed model were made. The intention was to use Cox piston/rod assemblies, and a batch of such items was actually sent to Alan Holmes in anticipation. However, they were never used. Pity ……….. Elfin 2.49 Diesel This was one of Dunham Engineering’s better-known and more successful products, particularly in the USA. It was a near-replica of the highly-regarded 1949 Elfin 2.49 cc radial mount diesel which remained in production for less than a year, consequently becoming a relatively rare and much sought-after engine in later years. Production of the Dunham replicas was concentrated during the period between 1984 and 1987.

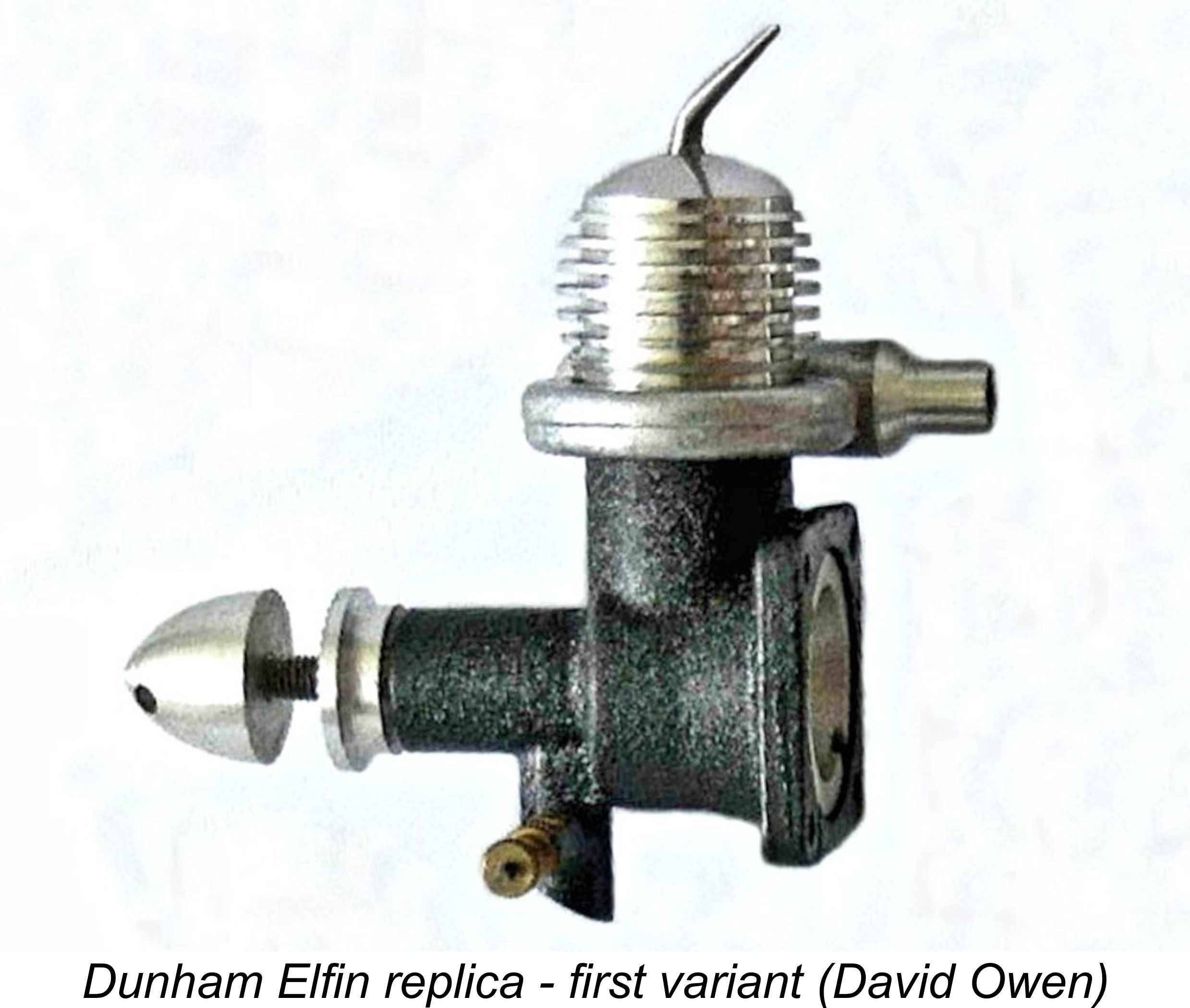

The result was that the appearance and speedy homologation of the light and powerful Dunham Elfin replica in 1984 was welcomed with open arms by SAM members in the USA. The rapid acceptance of the engine in America was greatly facilitated by its ready availability through the Houston, Texas-based agency of Bert Streigler. Beginning in February 1985, the engines also became readily available to modellers in Australia and New Zealand through the agency of David Owen. Examples quickly found their way into the Class A competition models of many SAM members, achieving a very high level of success. In America, the injection of the Dunham Elfin into this category led to a huge upswing in the use of diesels for Class A competition under SAM rules. Indeed, the overwhelming acceptance and competition success of the replica Elfin in the USA provides an indication of how diesels might have fared back in the 1940’s if they had been more actively developed or more effectively promoted in America ………………. In keeping with Dunham’s policy of not perpetuating what they saw as design flaws in a given model, their Elfin replicas featured stronger crankcases than the originals, with a slightly thicker and more squared-off mounting flange. They also featured somewhat longer intake venturi tubes, presumably to promote better suction. A neat combined exhaust collector/silencer unit of aluminium alloy was also made available. The Dunham Elfin underwent a number of detail design changes during the three or more years during which it was manufactured. Here’s a brief summary of the successive configurations in which the engine appears to have been marketed.

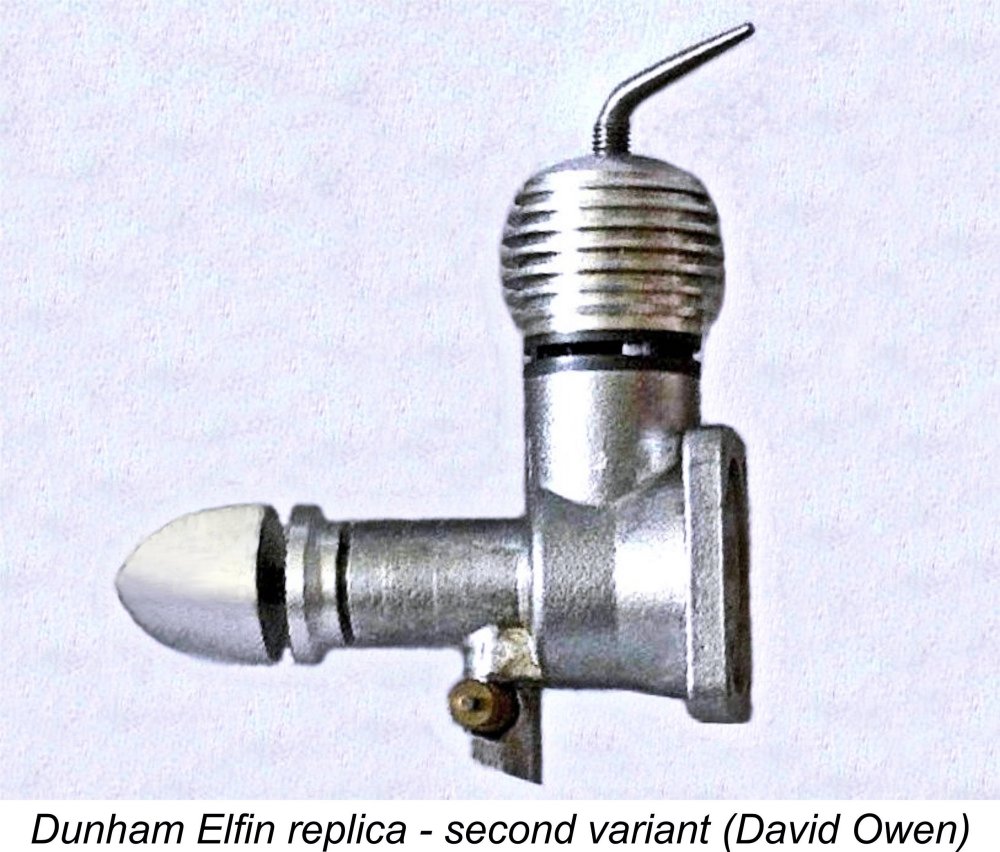

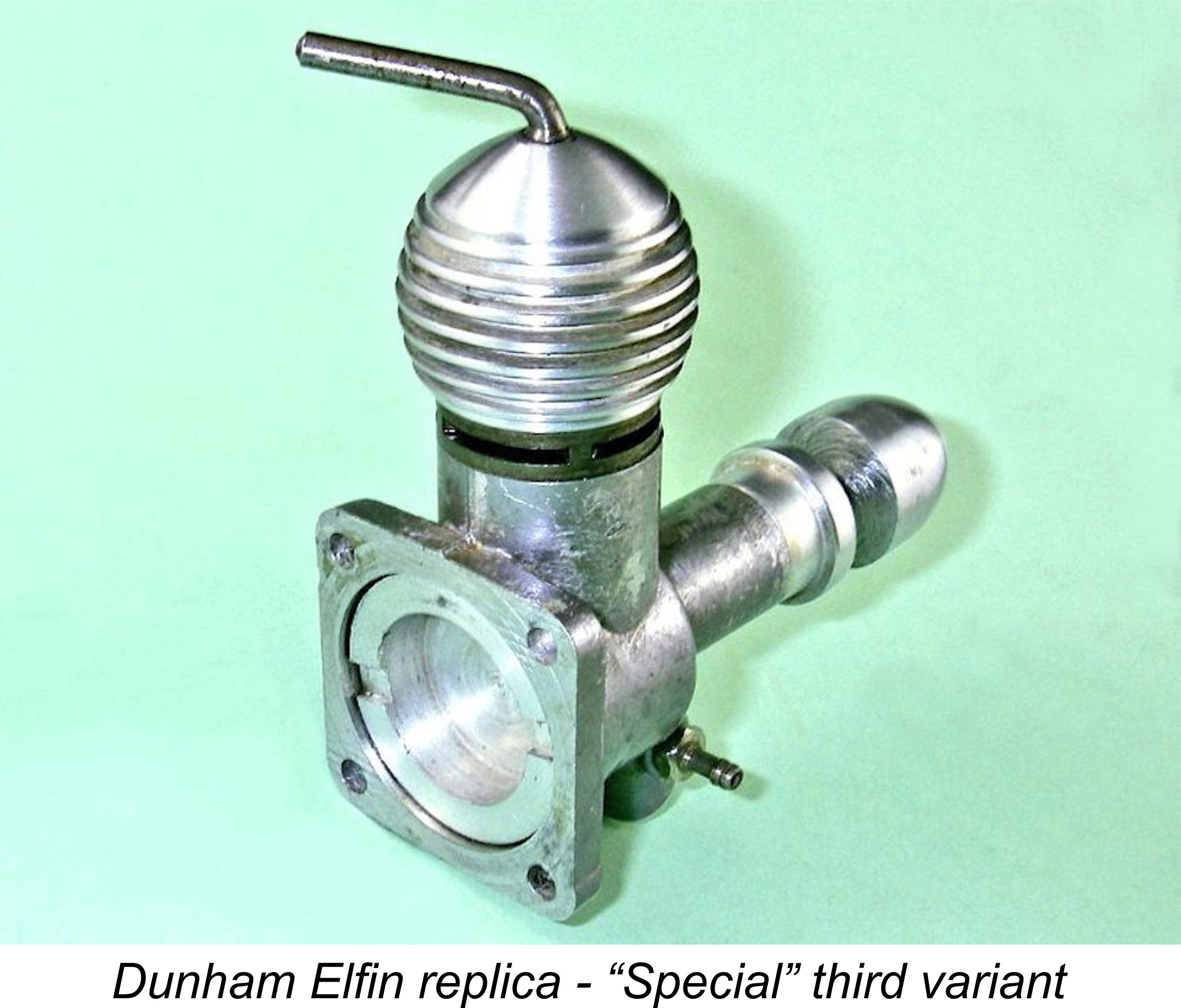

Cylinder porting followed the standard Elfin pattern with internally-formed bypass flutes in the cylinder wall, precluding the provision of any overlap between the exhaust and the transfers. The cast iron piston had a domed crown. The compression lever tapered to a very sharp point which imparted an elegant appearance but represented a considerable safety hazard - people were forever impaling their hands on this lever! The engine also featured a brass O.S. Pet needle valve assembly. Anyone who has made replica needle valve assemblies for vintage engines knows how surprisingly time-consuming this can be! The use of a readily-available proprietary component thus represented a worthwhile cost saving. Moreover, the O.S. unit was undeniably functionally superior to the Elfin original. That said, there was nothing to prevent a suitably-equipped purist from making his own replica of an original Elfin needle valve assembly. The crankshaft design followed that of the originals very closely up to the front of the main journal, with a plain disc crankweb having no counterbalance whatsoever. However, the shaft was truncated immediately Version 2 – this was identical to Version 1 except for the fact that the black crackle paint was omitted. It’s possible that some of the Version 1 and Version 2 engines were produced more or less concurrently. David Owen’s Version 2 example is illustrated. This is perhaps the most common variant of the engine. Version 3 - appeared somewhat later. This featured several design changes which distinguish it from its predecessors. It had been found that a flat-topped piston yielded improved handling and running characteristics, doubtless due to the swirl effect produced by the combination of a flat-topped piston with a concave contra piston surface. This version therefore featured such a piston.

A final change which was introduced at some point was the use of a compression lever having a blunt end in place of the very sharp point formerly used. This was a very good move – far too many modellers managed to impale their hands on that elegant but hazardous original component!! Otherwise, the engine was unaltered. In particular, the same crankcase casting was used. The illustrated example of this variant is actually an example of the “special” version of this model, to be discussed next. Version 3 “Special” – the confirmed existence of a number of examples in the writer’s possession and elsewhere confirms that at some point the company conducted a rather radical experiment to test the possibility of producing a “special” version of the Elfin replica having a significantly improved performance. My good mate Maris Dislers checked his example of the Dunham Elfin, finding that it too was of this type. So examples are now known to have found their way both to the USA and to Australia. Interestingly enough, Maris's example differs slightly from mine in that it features the larger cylindrical carburettor boss which was included in the fourth version of the Dunham Elfin to be described next. It thus appears that this variant lies more or less at the transition point between Version 3 and Version 4 of the engine. If anyone out there has knowledge of more examples, let’s hear from you!

The flat-topped piston was retained in this variant, but featured a significant design departure in the form of a circlip running round the piston in a groove formed externally at gudgeon (wrist) pin height. This circlip had the function of securing the gudgeon pin to prevent it from contacting and potentially scoring the bore or fouling a transfer port, thus allowing the use of a fully-floating gudgeon pin. The same approach had been adopted earlier in the design of the M.E. engines from the Isle of Man. While it works well enough, the drawback is that the circlip tends to become annealed over time, with the potential consequence that it can fail in service and do precisely what it was intended to prevent - foul the ports.

Although this can’t be proved pending the receipt of further information, it appears not unlikely that Dunham noted the success of their Elfin replica in American Class A competition under SAM rules and decided that a revised version with a higher performance might be well received. This would explain a decision to make some examples using Oliver porting. They certainly made an effort to maximize the engine’s potential - the quality of the internal fits in this example is truly superb. I don't know if the SAM rule-makers ever got wind of this change, which represented a radical departure from the original Elfin design. If the thing outperformed the existing Dunham Elfins (to say nothing of the originals), it would render them all obsolete overnight, which might not please a lot of people who had already made the investment............besides, no original Elfin 2.49 plain bearing model ever left the factory with this kind of porting! I have no information regarding how this matter was handled by SAM. At some point in the future I intend to run a comparative test between this example and a standard model. I will add the findings to this article at that time.

The one-piece shaft and longer splined prop driver were retained, but the prop was now secured with a steel acorn nut. The needle valve continued to be the O.S. Pet item used all along. At some point during the production run for this model, the piston material was changed from cast iron to hardened steel. The thinking behind this latter change is unclear.

When queried directly on this matter, Dunham's former officially-appointed US distributor, the late Bert Streigler, was unable to shed any light on how this came about - he sincerely believed himself to have been the sole US distributor! Moreover, he strongly concurred with the widely-expressed opinion that the Holmes family were extremely ethical in their business dealings and would never have knowingly undermined the status of their duly appointed American distributor.

Therein lies the probable explanation of this odd situation. After Dunham Engineering ended production of the Dunham Elfin in late 1987, the field was left open for another Elfin replica to pick up the considerable residual demand which still existed. First to rise to this challenge was the late Gordon Burford of Australia, who produced some 100 examples of his own very fine Elfin replica in 1989. However, John Targos appears at the same time to have begun to entertain ideas about entering the replica Elfin field himself. In support of this ambition, Targos first approached former Australian Dunham Following his inspection of these six flawed Dunham examples, Targos next approached Gordon Burford to seek practical assistance in setting up his own manufacturing venture. Gordon was finding it impossible to meet the demand for his own Elfin replica in a timely fashion, accordingly being happy to provide the requested assistance. Sadly, Gordon's very material assistance was never acknowledged by Targos, nor was Gordon’s agreed modest fee ever forthcoming.

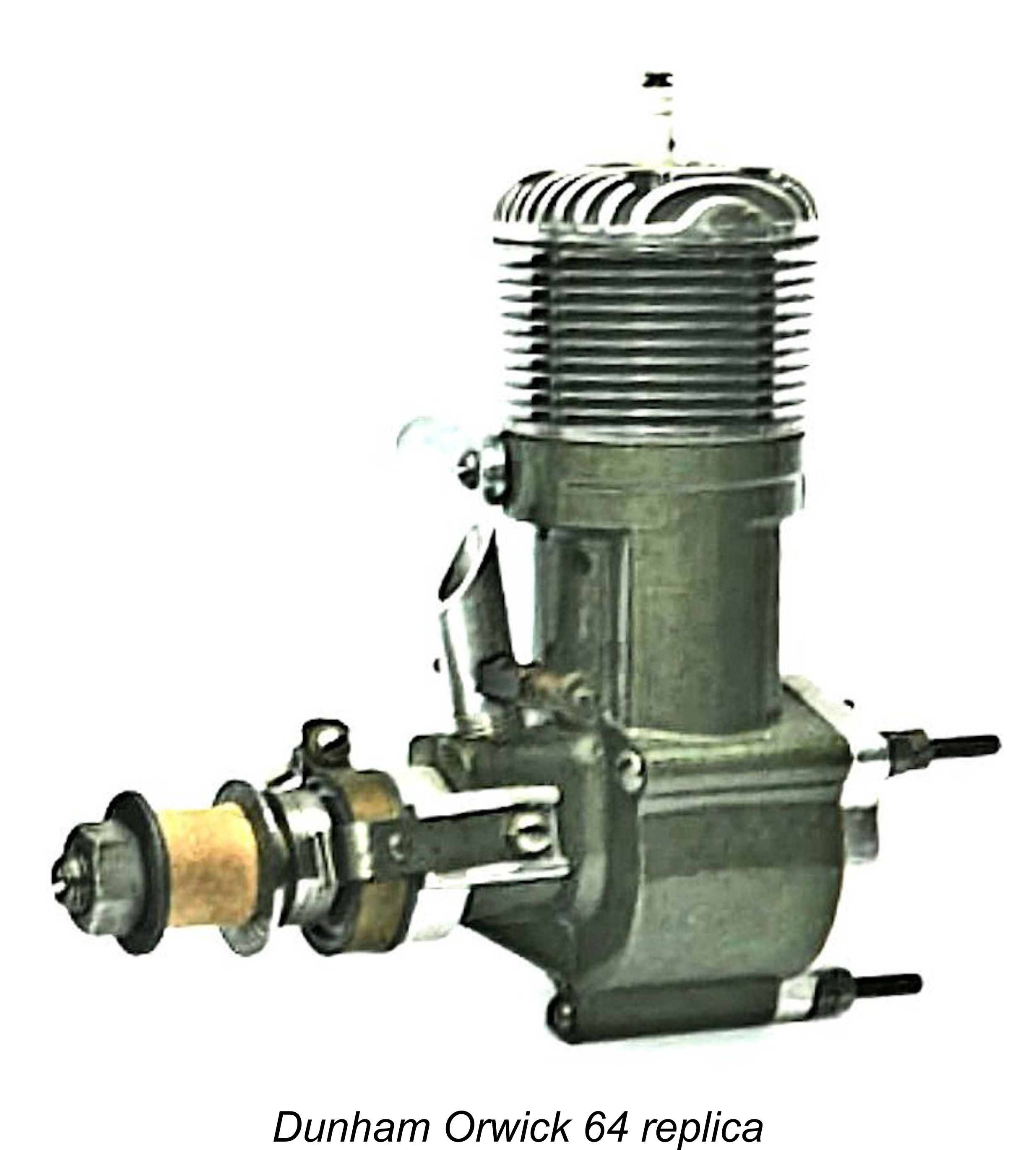

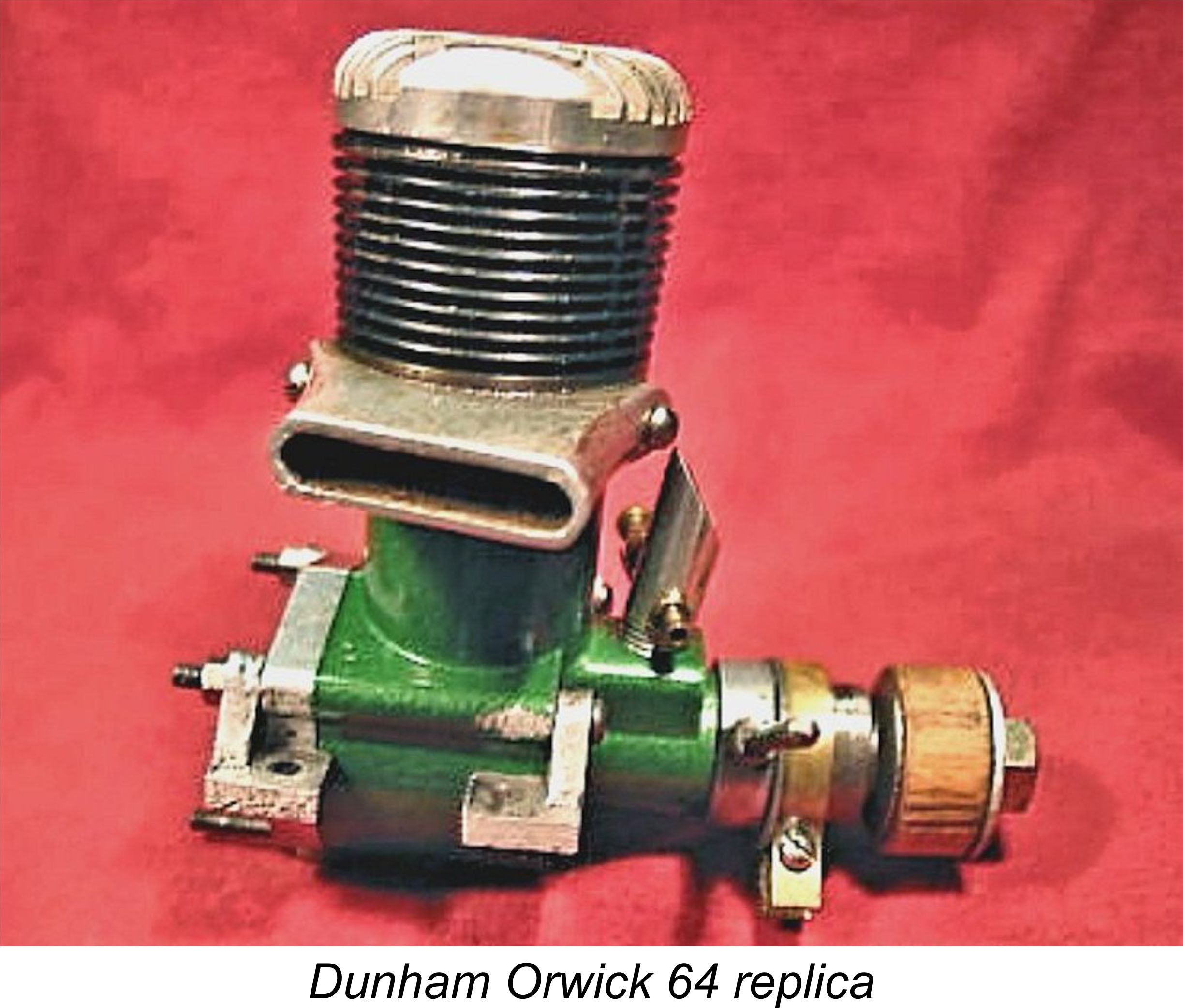

Unless someone can provide persuasive evidence to the contrary, I for one will continue to view this as the most probable explanation for the appearance of these “ARGO Dunhams”. If anyone out there can shed further light on this episode, please get in touch!! Another interesting tid-bit of information supplied by Bert Streigler during the writing of this article was the fact that at the end of his distributorship in 1988 he had a number of spare crankcases and other components on hand. Bert built these up into complete engines using additional components made by himself. There are thus a small number of Streigler-Dunham Elfin replicas floating about! It’s unclear how many examples of the Dunham Elfin were sold in the engine’s native Britain, but the number was David Owen confirmed that despite the undoubtedly sincere efforts of the Holmes family, the Dunham Elfins exhibited some variation in overall quality. This comment has been echoed by a number of independent sources. Although piston/cylinder fits were generally quite good, there were occasional problems relating to such issues as poorly-made conrods and misalignment of the various construction axes. However, a good example was very good indeed. Moreover, the company invariably stood behind its products by attending to any legitimate manufacturing shortcomings encountered by its customers. Overall, David Owen rated the general quality of these engines as “not P.A.W. standard, but generally OK”. As noted previously, at the end of his distributorship in late 1987 (when he last had contact with Dunham Engineering), David had accumulated six examples of the Dunham Elfin which he viewed as un-saleable for a variety of reasons - about 10% of the total which had passed through his hands. These were the engines which were subsequently traded to John Targos, as related earlier. Alan Holmes was reportedly extremely disappointed with the unexpectedly poor sales response to these engines in the UK. The quality issue may have had something to do with this, as may the harsh economic climate which prevailed in 1980’s Britain. Regardless of the reason however, the engine was not as well received in Britain as might have been expected. This issue was by no means confined to the Elfin replicas - the UK proved to be a rather dismal marketplace for most of the Dunham models. As we shall see, this was a major reason for the company ending model engine production in 1988. Orwick Spark Ignition/Glow-plug/Diesel The replicas for which the Dunham Engineering name is perhaps best remembered are the company’s series of Orwick models. These engines were produced for the most part during the years 1983 through 1986. Bert Streigler recalled loaning his own original Orwick 64 no. 64543 to Dunham for their use as a pattern when developing their Orwick 64 replica. As far as Bert was aware, three prototypes of this model were made. One was sent back to Bert (#3) and one to George Aldrich (#2), while the other (#1) remained in England.

Following an evaluation of these prototypes, it was decided to make changes which would return the production engines to closer conformity with the originals. Perhaps most significantly, the production models reverted to integrally-machined cooling fins on the steel cylinders. The late David Janson expressed his opinion that the resulting production version of the Dunham Orwick 64 and its relatives ended up being 95% faithful to the originals. However, the production replicas undeniably retained a number of readily observable differences if one knew what to look for. The crankcases were not sand-cast as per the originals, but were die-cast using a two-piece steel die. BA screws were used throughout except for the prop nut, which was threaded to US standard as per the original, although both the prop washer and prop nut were much smaller than those used on the originals. The base for attaching the exhaust stack was slightly different, as was the stack casting employed. The combined prop driver/ignition cam was secured by a split collet instead of the square-on-shaft system seen on the originals. Finally, three different types of needles were utilized, none of which conformed to the original items.

A careful examination of both the Dunham and K&M Orwick replicas undertaken by David Janson indicated that while the Dunhams were about 95% faithful to the originals, the K&Ms were almost 100% accurate. However, the Dunhams were considerably less expensive, ranging in price from $140 to $190 depending on the model. Against that, the quality of the Dunham replicas was not quite up to the very high standard exhibited in the K&M models. As always, you got what you paid for .......... The larger Dunham engines came in an attractive carton with coil, condenser and a set of optional beam mounts as well as a copy of the original Orwick parts list and running instructions. To clearly distinguish them from the originals, the backplates were stamped “Made in England” followed by a serial number of the 64xxx pattern (or 73xxx for the companion 0.73 cuin. models which were also offered). These Dunham replicas were very attractive engines with a very crisp “new” appearance. They were also generally very well made. However, they were not without problems in an operational sense. Modellers who actually used them for flying purposes quickly discovered that the crankshafts weren't hardened properly, if at all. Another issue which emerged was the fact that the leaf springs for the moving point were not tempered, consequently tending to suffer fatigue failures relatively early on. To their credit, the company The 64 and 73 models were not the only Orwick replicas offered by Dunham. The late great George Aldrich supplied an original example of an Orwick 29, from which a Dunham replica was also created. This followed more or less the same development pattern as that described above for the 64. Bert Streigler later provided an example of the Orwick 32, which was also used as a pattern by Dunham Engineering to create a 32 replica. These engines were finished in a distinctive glossy green paint. Bert Streigler believed that around 200 of the 29/32 series spark ignition engines were sold in the USA. In addition, around 35 examples of the 29/32 series were sold in glow-plug configuration. These smaller engines came in a close A very few examples of the Dunham Orwick29 and 64 engines were sold with Super Tigre mufflers and a specially-designed throttle for R/C use. Bert reckoned that only about ten or so were sold in this configuration. The 29 R/C model was based upon the 32 case since it accepted a muffler more readily. A single example of a magneto-equipped Orwick 64 was also produced purely to test the concept. Although it reportedly ran very well, it was never produced in series due to cost and complexity factors. There were also a few Orwick 29 diesels. These too were based on the Orwick 32 case, being finished in the same glossy green paint as the sparkers. They were very handsome engines as well as being strong runners. They were identified by having a large letter S stamped on the backplate, with the numbers 2 and 9 appearing above and below the S respectively. However, they did not bear serial numbers. As far as Bert Streigler was aware, only ten or so of these were made. Valkyrie Diesel and Viking Spark Ignition

In this regard, there have been persistent reports from users that many of these engines were supplied with too-tight crankshaft fits which caused them to overheat and sag. It was apparently a good idea to dismantle the engines and relieve the shaft fits somewhat by lapping. After this treatment, they evidently ran very well. Former Australian Dunham distributor David Owen confirmed that this was indeed a common fault with these engines. However, it was also easily remedied.

Color schemes varied as well, with finishes ranging between smooth black, crinkle black, smooth green and crinkle green. A very few were also made with natural finish cases. About 150 examples of these models were produced, most of which were sold in the USA through Bert Streigler. Almost all were the Valkyrie diesel model, well set-up examples of which achieved some success in SAM Class B contests in the USA. M.E. Engines David Owen provided evidence in the form of an un-dated article which appeared in the contemporary English modelling press to the effect that towards the end of their active involvement with model engines, Dunham were planning to market reproduction versions of the M.E. range which had originally been manufactured in the Isle of Man during the 1960’s. Given the astonishing frequency with which M.E. parts used to show up literally by the sackful on the UK market, it’s entirely possible and even likely that these engines were intended to be based upon original components assembled by Dunham, with any missing bits being manufactured by Dunham as well.

It must be admitted that the Wren seen in the image bears a strong superficial resemblance to the A-S 55 ……. but then, design originality was never M.E.’s strong suit! It seems possible, albeit completely unproven, that M.E. acquired the A-S 55 project after the original manufacturers Allbon-Saunders terminated model engine production in 1964. If anyone out there knows more, please get in touch .......... The End of the Road Various tales have been told regarding the reasons for Dunham Engineering abandoning the model engine field, which they did rather precipitately in 1988 after only 7 years in the business. Bert Streigler reckoned that although there were doubtless other contributing factors, it probably came down in the end to simple economics. The plain fact was that small-scale production of replica model engines could never have been viewed as a major money-making venture but rather had to be undertaken primarily as a labour of love. The Holmes family very likely came to the realization that their technical expertise could be put to more remunerative use, amending their business plan accordingly. That said, the company had persisted for quite a while in the face of lower-than-anticipated sales interest from those who might reasonably have been expected to support their efforts to the full. Notable among these were the vintage modellers of their native British Isles. By all reports, the relative lack of support from the domestic vintage modelling community contributed significantly to the company’s decision to abandon the field. A labour of love still needs to be nourished by indications that the effort is valued by others. Such indications were seemingly few and far between in Britain. In this context, it must be recalled that the average British resident was going through a very bad patch indeed in the 1980’s under the Thatcher government, whose policies of flagrantly favouring its wealthy corporate and individual supporters over the interests of the average Briton had a devastating effect upon the economic wellbeing and employment prospects of the mainstream British population. This factor makes it undeniable that the lack of domestic support for Dunham Engineering may well have had far less to do with lack of appreciation of their efforts than with plain economics.

One example of this which was displayed was an Orwick 64 which had been sold in perfect condition only a few weeks previously and had been returned with a complaint that it didn’t run. The reason for this turned out to be that the owner had mindlessly drilled the three radial mounting holes to an enlarged diameter of 3/16 inch. As a result, they had (quite predictably) broken through into the crankcase interior, thus ventilating the case and destroying crankcase compression along with the engine's structural integrity. How anyone with a trace of self-respect could have the gall to claim this as a manufacturing fault is beyond rational explanation………however, this was seemingly not an isolated incident. It appears that it was a combination of UK customer indifference, flagrant customer abuses of the sort just described and the inherent lack of profitability of a small-scale model engine manufacturing venture that led to the 1988 cessation of model engine production by Dunham Engineering. A sad loss to the vintage modelling movement, although it would be some time before this was fully appreciated. Conclusion Dipping into the discussion threads on various model engine-related forums over the years, there have been frequent references to various shortcomings displayed by some of the Dunham models. This has cumulatively led to a distressingly widespread present-day view that these engines constituted in some senses a second-rate range, to be approached with caution.

Accordingly, when the modelling world lost the services of Dunham Engineering they lost a highly motivated and ethical company which had made a genuine effort to supply what they perceived as a need among their fellow enthusiasts. It’s very pleasing to be able to report that the end of model engine manufacture by no means heralded the end of the company. On the contrary, they returned to their original business of manufacturing spare parts and undertaking repairs for agricultural machinery, a venture which was evidently completely successful. At some point Dunham Engineering relocated to new expanded premises located a little to the west in nearby Skelmersdale. As of 2014, the company remained in operation, working from an address at 48-49 Greenhey Place, Skelmersdale, West Lancashire, WN8 9SA. They were apparently still engaged in plant and machinery repair work. However, by 2020 they were listed as no longer being in business. I hope you've enjoyed this look at one of England's more dedicated manufacturers of replica engines. I for one continue to enjoy their products very much! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published April 2015

|

| |

The Dunham Engineering company of Wigan in England was one of the first model engine manufacturing concerns worldwide to focus strictly on the series production of replica and retro model engines as opposed to the development and manufacture of new up-to-date designs. In doing so, the company was tapping into a market which was just reaching maturity as the modelling world headed into the 1980’s.

The Dunham Engineering company of Wigan in England was one of the first model engine manufacturing concerns worldwide to focus strictly on the series production of replica and retro model engines as opposed to the development and manufacture of new up-to-date designs. In doing so, the company was tapping into a market which was just reaching maturity as the modelling world headed into the 1980’s.  Background

Background

What changed matters significantly as time went by was the increasing chronological separation of active modellers from the dates of manufacture of the older engines, particularly those from the “pioneering” era. As these engines became ever older, they became viewed with increasing nostalgia, particularly by the growing community of aging but still-active modellers who had used them in their younger years. Guilty as charged, your Honour, as the attached image should clearly demonstrate!!

What changed matters significantly as time went by was the increasing chronological separation of active modellers from the dates of manufacture of the older engines, particularly those from the “pioneering” era. As these engines became ever older, they became viewed with increasing nostalgia, particularly by the growing community of aging but still-active modellers who had used them in their younger years. Guilty as charged, your Honour, as the attached image should clearly demonstrate!!

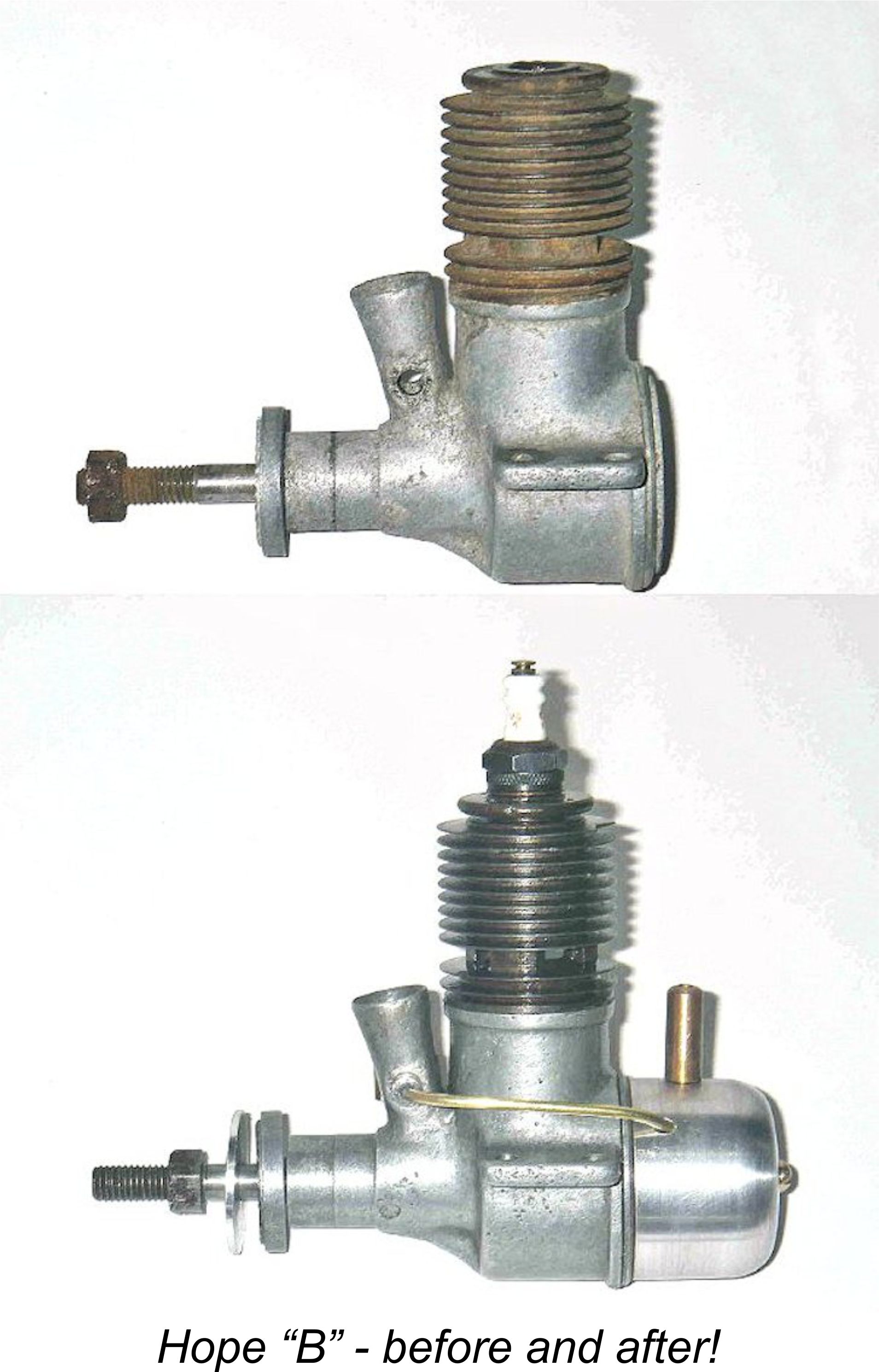

In conservation terms, this had one very positive effect - the old “junk” engines in the attic or in Dad’s old model box became increasingly seen as having a value and thus being worthy of being brought out of hibernation to be offered for sale rather than being thrown out with the rubbish when it came time to clean out the attic. The result was that a good many collectible engines which might otherwise have ended up in the dump were returned to circulation. Not only that, but their restoration became worthwhile given the extent to which a competent restoration can increase a given example’s interest and value. Would the illustrated example of the

In conservation terms, this had one very positive effect - the old “junk” engines in the attic or in Dad’s old model box became increasingly seen as having a value and thus being worthy of being brought out of hibernation to be offered for sale rather than being thrown out with the rubbish when it came time to clean out the attic. The result was that a good many collectible engines which might otherwise have ended up in the dump were returned to circulation. Not only that, but their restoration became worthwhile given the extent to which a competent restoration can increase a given example’s interest and value. Would the illustrated example of the  The Dunham Engineering enterprise was established by Alan Holmes Sr. in partnership with his two sons Alan Jr. and Barry. Alan Sr.’s wife Joyce acted as the firm’s business manager. The company’s address was given as Dunham Engineering, 12 Lawns Ave., Orrell, Wigan, Lancashire, England.

The Dunham Engineering enterprise was established by Alan Holmes Sr. in partnership with his two sons Alan Jr. and Barry. Alan Sr.’s wife Joyce acted as the firm’s business manager. The company’s address was given as Dunham Engineering, 12 Lawns Ave., Orrell, Wigan, Lancashire, England. The company’s manufacturing activities were conducted very much on a hands-on basis, with essentially all of the work eventually being carried out by the Holmes family themselves at the family residence. However, the company moved towards all in-house production in measured stages - a very sensible approach given the fact that they were new at the model engine manufacturing game. My late friend Ian Russell of Rustler fame has confirmed that a large number of the components used in the early Dunham replica engines (notably crankshafts) were made for them by

The company’s manufacturing activities were conducted very much on a hands-on basis, with essentially all of the work eventually being carried out by the Holmes family themselves at the family residence. However, the company moved towards all in-house production in measured stages - a very sensible approach given the fact that they were new at the model engine manufacturing game. My late friend Ian Russell of Rustler fame has confirmed that a large number of the components used in the early Dunham replica engines (notably crankshafts) were made for them by

Mechanair 6.9 cc Spark Ignition

Mechanair 6.9 cc Spark Ignition bore was increased to raise the displacement from 5.9 cc to 6.9 cc - a gain of some 17%. Along with this increase went improvements to the design of the cylinder transfer and exhaust ports as well as an improved piston baffle configuration. Understandably, some purists questioned the extent of these departures from the originals, but they did result in a far stronger-running unit while not significantly affecting the external appearance of the engine.

bore was increased to raise the displacement from 5.9 cc to 6.9 cc - a gain of some 17%. Along with this increase went improvements to the design of the cylinder transfer and exhaust ports as well as an improved piston baffle configuration. Understandably, some purists questioned the extent of these departures from the originals, but they did result in a far stronger-running unit while not significantly affecting the external appearance of the engine. Mechanair was also made available as a kit of parts in varying stages of completion. One offering was a complete set of finished parts requiring only assembly. The other was a kit of castings and materials complete with working drawings.

Mechanair was also made available as a kit of parts in varying stages of completion. One offering was a complete set of finished parts requiring only assembly. The other was a kit of castings and materials complete with working drawings. Soon after production commenced, Dunham Engineering obtained permission from John Oliver to resume production of the Oliver Battleaxe 2 cc sideport diesel which had been the first model engine to bear the Oliver name. This design dated back to the early post-war period prior to Oliver’s brief 1949 association with Raylite of Nottingham. It was among the many early model diesels which closely followed the Dyno pattern.

Soon after production commenced, Dunham Engineering obtained permission from John Oliver to resume production of the Oliver Battleaxe 2 cc sideport diesel which had been the first model engine to bear the Oliver name. This design dated back to the early post-war period prior to Oliver’s brief 1949 association with Raylite of Nottingham. It was among the many early model diesels which closely followed the Dyno pattern. ball-race specials were also made.

ball-race specials were also made. The Battleaxe singles looked good and ran well, but failed to attract much sales interest. This was particularly (and somewhat inexplicably) true in their native Britain, where strong support for this venture might reasonably have been anticipated but was not forthcoming. The original intention had been to produce 50 of the singles and 10 of the twins. Bert Streigler believed that in fact probably only about 30 singles were made in total, of which perhaps 13 were sold in the USA. However, this recollection is at variance with the indisputable existence of Dunham Battleaxe replica no. 51 as illustrated here. Unless there was a gap in the numbering sequence, this engine appears to imply that the target was met or perhaps even slightly exceeded for that model.

The Battleaxe singles looked good and ran well, but failed to attract much sales interest. This was particularly (and somewhat inexplicably) true in their native Britain, where strong support for this venture might reasonably have been anticipated but was not forthcoming. The original intention had been to produce 50 of the singles and 10 of the twins. Bert Streigler believed that in fact probably only about 30 singles were made in total, of which perhaps 13 were sold in the USA. However, this recollection is at variance with the indisputable existence of Dunham Battleaxe replica no. 51 as illustrated here. Unless there was a gap in the numbering sequence, this engine appears to imply that the target was met or perhaps even slightly exceeded for that model. other was finished in black crackle paint.

other was finished in black crackle paint. license fee. John Goodall later recorded some unsubstantiated reports from the Isle of Man to the effect that the Davies family charged a royalty of £1 per engine to Dav-Cal during the brief period during which that company took over the Davies-Charlton range beginning in November of 1982 - this at a time when the engines sold (with difficulty!) on the retail market for prices in the £3 range! Talk about a millstone around the neck ……..!

license fee. John Goodall later recorded some unsubstantiated reports from the Isle of Man to the effect that the Davies family charged a royalty of £1 per engine to Dav-Cal during the brief period during which that company took over the Davies-Charlton range beginning in November of 1982 - this at a time when the engines sold (with difficulty!) on the retail market for prices in the £3 range! Talk about a millstone around the neck ……..! Taplin Twin Diesel

Taplin Twin Diesel Dunham’s former US agent, the late Bert Streigler, voiced his well-informed opinion that the advent of the Dunham Elfin permanently changed the face of the SAM Class A competition class in America, which allowed specified diesel engines to compete alongside eligible spark ignition models. One of the homolgated diesels was the 1949 radial-mount Elfin 2.49. Until the arrival of the Dunham replica, original examples of that model were so scarce in the USA that few modellers were able to use one in competition. However, those few examples that did appear demonstrated convincingly that the 1949 Elfin possessed a power-to-weight ratio which was unparalleled among SAM-homologated Class A powerplants at the time.

Dunham’s former US agent, the late Bert Streigler, voiced his well-informed opinion that the advent of the Dunham Elfin permanently changed the face of the SAM Class A competition class in America, which allowed specified diesel engines to compete alongside eligible spark ignition models. One of the homolgated diesels was the 1949 radial-mount Elfin 2.49. Until the arrival of the Dunham replica, original examples of that model were so scarce in the USA that few modellers were able to use one in competition. However, those few examples that did appear demonstrated convincingly that the 1949 Elfin possessed a power-to-weight ratio which was unparalleled among SAM-homologated Class A powerplants at the time. Version 1 – this was the original form in which the Dunham Elfin appeared. As previously noted, it had a somewhat different crankcase casting from the original 1949 Elfin, featuring a thicker and more square-sectioned mounting flange as well as a slightly longer intake venturi. However, the needle valve boss was of the same small diameter as seen in the originals. The crankcase was finished in black crackle paint. David Owen’s illustrated example was fitted with the previously-mentioned exhaust collector/silencer unit.

Version 1 – this was the original form in which the Dunham Elfin appeared. As previously noted, it had a somewhat different crankcase casting from the original 1949 Elfin, featuring a thicker and more square-sectioned mounting flange as well as a slightly longer intake venturi. However, the needle valve boss was of the same small diameter as seen in the originals. The crankcase was finished in black crackle paint. David Owen’s illustrated example was fitted with the previously-mentioned exhaust collector/silencer unit. forward of the main journal. Instead of the integrally-formed threaded extension used in the original Elfins, a separate screw-in prop mounting stud was used in the early Dunham replicas along with a light alloy spinner nut and a relatively short prop driver which was mounted on a split collet.

forward of the main journal. Instead of the integrally-formed threaded extension used in the original Elfins, a separate screw-in prop mounting stud was used in the early Dunham replicas along with a light alloy spinner nut and a relatively short prop driver which was mounted on a split collet. At some point during the production run of this variant, the crankshaft design was also changed. Instead of a separate prop mounting stud being used along with a short split collet-mounted prop driver, the shaft was made in one piece with an integral threaded section for prop mounting. The prop driver was secured to the shaft by splines and was made somewhat longer to increase the effective length of the splines, thus minimizing any tendency for them to strip. The aluminium alloy spinner nut was retained in this version. This actually brought the engine into closer conformity with the original, which may have been one motivation for this amendment.

At some point during the production run of this variant, the crankshaft design was also changed. Instead of a separate prop mounting stud being used along with a short split collet-mounted prop driver, the shaft was made in one piece with an integral threaded section for prop mounting. The prop driver was secured to the shaft by splines and was made somewhat longer to increase the effective length of the splines, thus minimizing any tendency for them to strip. The aluminium alloy spinner nut was retained in this version. This actually brought the engine into closer conformity with the original, which may have been one motivation for this amendment. Externally, this variant appears identical in all respects to Version 3. Internally however, it is a very different story! This variant features “Oliver” porting in place of the original Elfin system. The four transfer ports are drilled at an upward angle through the pillars of metal between the exhaust openings, overlapping the exhaust almost completely in true Oliver fashion. They are fed by four generously-sized bypass passages formed in the outer cylinder wall and hence interrupting the cylinder installation threads. This version might reasonably be expected to have a significantly stronger top end than the standard Elfin design.

Externally, this variant appears identical in all respects to Version 3. Internally however, it is a very different story! This variant features “Oliver” porting in place of the original Elfin system. The four transfer ports are drilled at an upward angle through the pillars of metal between the exhaust openings, overlapping the exhaust almost completely in true Oliver fashion. They are fed by four generously-sized bypass passages formed in the outer cylinder wall and hence interrupting the cylinder installation threads. This version might reasonably be expected to have a significantly stronger top end than the standard Elfin design. This example of the “special” is fitted with an O.S. 10 FSR needle valve assembly as seen on the later

This example of the “special” is fitted with an O.S. 10 FSR needle valve assembly as seen on the later  Version 4 – this proved to be the final variant of the Dunham Elfin replica. It was based upon a revised crankcase casting featuring a far thicker (and hence even stronger) mounting flange along with a needle valve boss of significantly greater diameter. This latter feature may perhaps imply that the manufacturers were entertaining visions of developing an R/C throttle or at least a rotary fuel cut-off for this engine. If so, such accessories never appeared in any quantity.

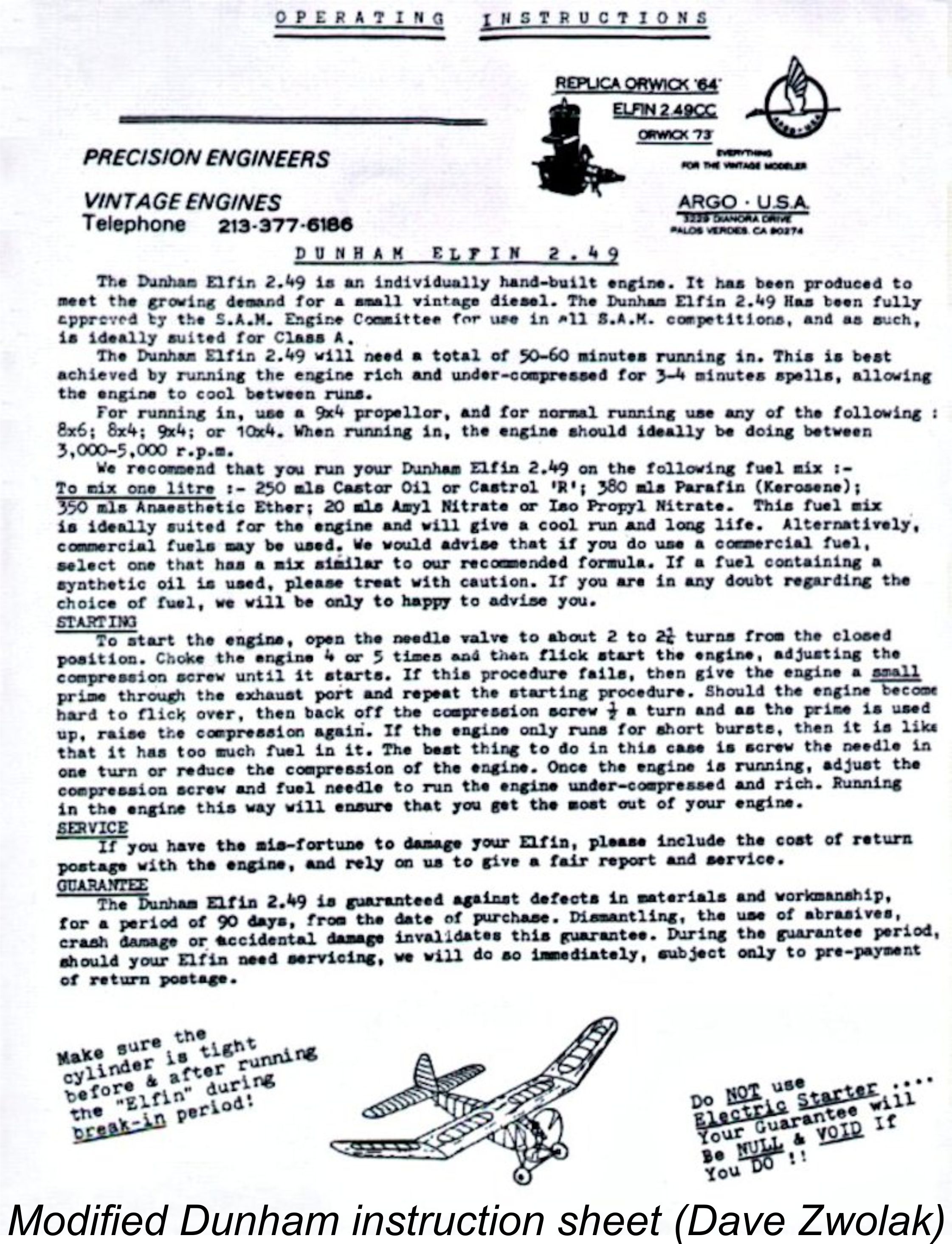

Version 4 – this proved to be the final variant of the Dunham Elfin replica. It was based upon a revised crankcase casting featuring a far thicker (and hence even stronger) mounting flange along with a needle valve boss of significantly greater diameter. This latter feature may perhaps imply that the manufacturers were entertaining visions of developing an R/C throttle or at least a rotary fuel cut-off for this engine. If so, such accessories never appeared in any quantity.  At least a few of these final variants are definitely known to have been marketed by John Targos of the California-based vintage model supply company ARGO USA. David Zwolak had a NIB example in an ARGO USA box with a Dunham instruction sheet which featured Targos’s ARGO USA logo superimposed upon the otherwise unchanged Dunham original, together with Targos’s business card on which he characterized himself as a Dunham dealer.

At least a few of these final variants are definitely known to have been marketed by John Targos of the California-based vintage model supply company ARGO USA. David Zwolak had a NIB example in an ARGO USA box with a Dunham instruction sheet which featured Targos’s ARGO USA logo superimposed upon the otherwise unchanged Dunham original, together with Targos’s business card on which he characterized himself as a Dunham dealer. However, Bert was of course well aware of the American-made

However, Bert was of course well aware of the American-made  distributor David Owen to ask if he had any Dunham examples left, presumably to serve as reference samples to guide Targos in setting up his own production. As it happened, David still had six unused New-in-Box examples on hand, although all of these were flawed in some way to an extent which rendered them un-saleable in David’s highly ethical view. David told Targos as much, but he was still interested. After some rather challenging negotiations, David ended up trading these engines to Targos for a box of model-sized spark plugs! David’s records showed that the six engines were sent to Targos on May 26

distributor David Owen to ask if he had any Dunham examples left, presumably to serve as reference samples to guide Targos in setting up his own production. As it happened, David still had six unused New-in-Box examples on hand, although all of these were flawed in some way to an extent which rendered them un-saleable in David’s highly ethical view. David told Targos as much, but he was still interested. After some rather challenging negotiations, David ended up trading these engines to Targos for a box of model-sized spark plugs! David’s records showed that the six engines were sent to Targos on May 26 Nonetheless, Gordon’s input (which included the provision of at least one example of his own replica) presumably meant that the six Dunham Elfins supplied by David Owen were no longer of value as reference samples. It appears that Targos may have sold them on as useable engines despite David Owen’s clearly-stated contrary opinion. All that was necessary was to superimpose the ARGO USA logo onto the Dunham instruction sheet as illustrated earlier and include a cobbled-up business card styling Targos as a Dunham dealer. This over a year after Dunham had ceased production ..........

Nonetheless, Gordon’s input (which included the provision of at least one example of his own replica) presumably meant that the six Dunham Elfins supplied by David Owen were no longer of value as reference samples. It appears that Targos may have sold them on as useable engines despite David Owen’s clearly-stated contrary opinion. All that was necessary was to superimpose the ARGO USA logo onto the Dunham instruction sheet as illustrated earlier and include a cobbled-up business card styling Targos as a Dunham dealer. This over a year after Dunham had ceased production .......... apparently well below expectations. Bert Streigler reckoned that he sold around 200 examples in the USA, mainly to Class A competitors in SAM events. On top of this, a few additional examples were evidently sold independently in the USA by John Targos. David Owen was the distributor of these engines in Australia, and he estimated that he sold perhaps 50 examples to purchasers in Australia and New Zealand. We might not be too far wrong in speculating that perhaps 500 examples may have been made in total.

apparently well below expectations. Bert Streigler reckoned that he sold around 200 examples in the USA, mainly to Class A competitors in SAM events. On top of this, a few additional examples were evidently sold independently in the USA by John Targos. David Owen was the distributor of these engines in Australia, and he estimated that he sold perhaps 50 examples to purchasers in Australia and New Zealand. We might not be too far wrong in speculating that perhaps 500 examples may have been made in total.  The prototype Dunham version of the Orwick differed from the original in several respects. The original Orwicks had steel cylinders with integrally-formed cooling fins, while the Dunham prototypes had shrunk-on aluminium alloy sleeves which incorporated the cooling fins. The exhaust stacks were also somewhat different in shape. The crankcase finish was more or less the same dull green crackle paint that had been used on the originals.

The prototype Dunham version of the Orwick differed from the original in several respects. The original Orwicks had steel cylinders with integrally-formed cooling fins, while the Dunham prototypes had shrunk-on aluminium alloy sleeves which incorporated the cooling fins. The exhaust stacks were also somewhat different in shape. The crankcase finish was more or less the same dull green crackle paint that had been used on the originals. Despite these departures, the resulting engines became perhaps the best-known of the Dunham replicas. Bert Streigler recalled selling around 700 examples of the replica Orwick 64 and perhaps 150 examples of the companion 73. This was an impressive total, especially considering the fact that the superb American-made K&M Orwick 64 replicas produced in California by Joe Klause and John McCollum came on the market in 1983 at about the same time. Additional examples were sold in various countries throughout the world. The total almost certainly exceeded 1000 units. This number far exceeded the production of the competing but more expensive K&M replicas.

Despite these departures, the resulting engines became perhaps the best-known of the Dunham replicas. Bert Streigler recalled selling around 700 examples of the replica Orwick 64 and perhaps 150 examples of the companion 73. This was an impressive total, especially considering the fact that the superb American-made K&M Orwick 64 replicas produced in California by Joe Klause and John McCollum came on the market in 1983 at about the same time. Additional examples were sold in various countries throughout the world. The total almost certainly exceeded 1000 units. This number far exceeded the production of the competing but more expensive K&M replicas.

The Valkyrie 5.33 cc diesel model and its Viking spark-ignition relative were “retros” rather than replicas, since they were actually designed in the post-vintage era by Alan Holmes’s son Barry, albeit some years before Dunham Engineering entered the model engine business. Once Dunham got rolling, these engines were put into production. They were really nice units which ran very well indeed if properly set up.

The Valkyrie 5.33 cc diesel model and its Viking spark-ignition relative were “retros” rather than replicas, since they were actually designed in the post-vintage era by Alan Holmes’s son Barry, albeit some years before Dunham Engineering entered the model engine business. Once Dunham got rolling, these engines were put into production. They were really nice units which ran very well indeed if properly set up.

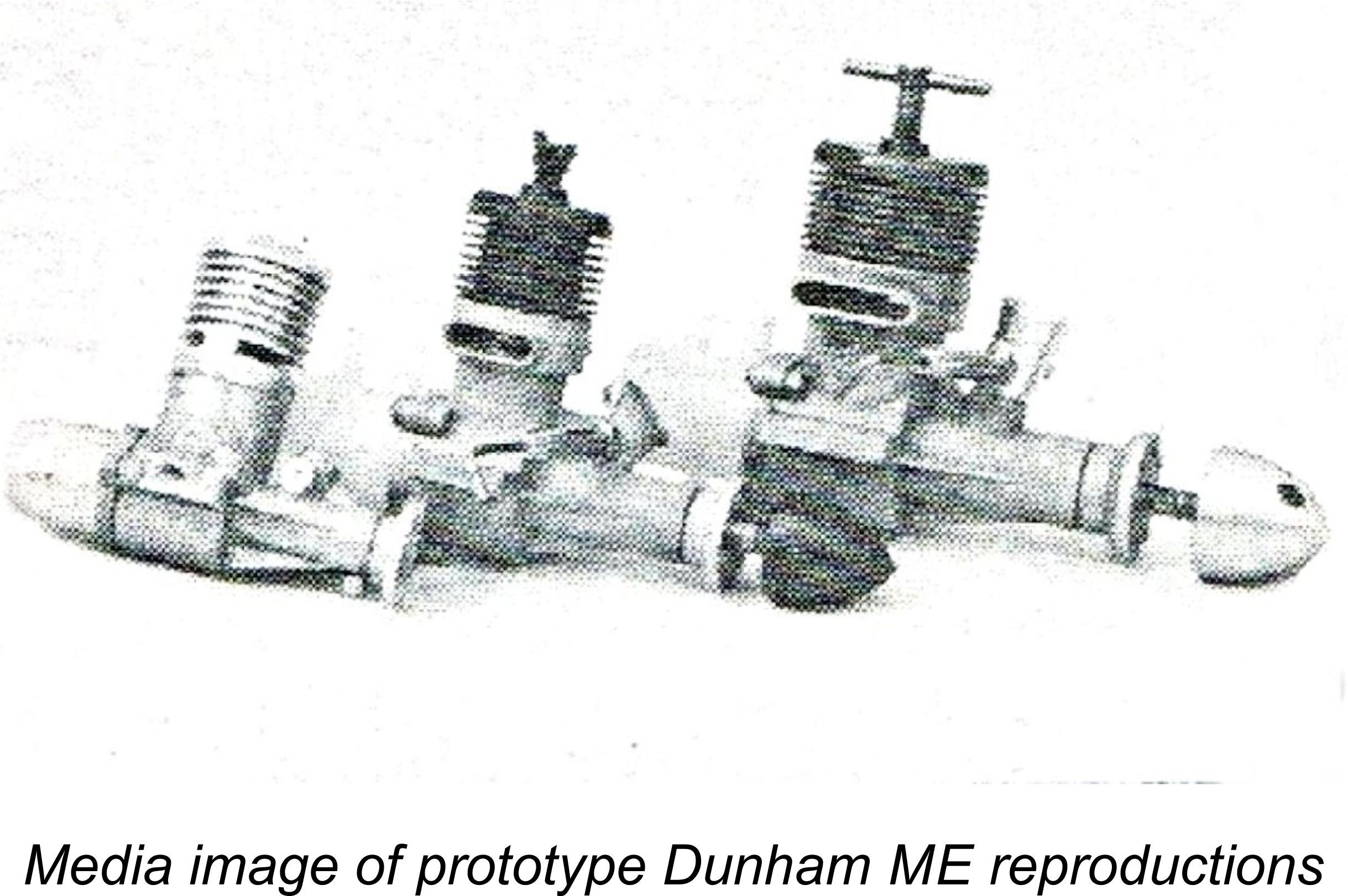

An image was included in the article showing the Dunham versions of the 1 cc M.E. Heron and 1.5 cc M.E. Snipe, together with an engine which never reached the market at any time, the M.E. Wren of un-stated but clearly lesser displacement. Despite the unavoidably poor quality of the available scan, the image proves conclusively that at least one prototype of each of these models was produced by Dunham, but the M.E. reproductions do not appear to have entered series production in quantity.

An image was included in the article showing the Dunham versions of the 1 cc M.E. Heron and 1.5 cc M.E. Snipe, together with an engine which never reached the market at any time, the M.E. Wren of un-stated but clearly lesser displacement. Despite the unavoidably poor quality of the available scan, the image proves conclusively that at least one prototype of each of these models was produced by Dunham, but the M.E. reproductions do not appear to have entered series production in quantity. Issues with individual customers also played a part. John Goodall reported in MEW that during a visit to the Dunham workshops just before the company abandoned the model engine field, an unnamed customer was treated to a tirade from Alan Holmes regarding the lack of support from the British vintage modelling community as well as their chronic tendency to mistreat his engines and then blame the resulting problems on the company! In support of his contention in this latter regard, Alan showed the customer a number of engines which had been returned by their British purchasers as faulty but were in reality the victims of their owners’ crass and very obvious stupidity!

Issues with individual customers also played a part. John Goodall reported in MEW that during a visit to the Dunham workshops just before the company abandoned the model engine field, an unnamed customer was treated to a tirade from Alan Holmes regarding the lack of support from the British vintage modelling community as well as their chronic tendency to mistreat his engines and then blame the resulting problems on the company! In support of his contention in this latter regard, Alan showed the customer a number of engines which had been returned by their British purchasers as faulty but were in reality the victims of their owners’ crass and very obvious stupidity! In reality, this impression is quite unfair to Dunham Engineering. I hope that I’ve demonstrated very conclusively that the manufacture of the Dunham replicas and retros was very much a labour of love undertaken by a family of genuine enthusiasts. They put their hearts and souls into offering the best products that they could given the somewhat grassroots conditions under which they were constrained to work. And while it’s true that quality issues did undoubtedly arise from time to time with specific examples of their products, this is equally true of many far more prominent model engine ranges. Moreover, Dunham Engineering invariably stood behind their work by remedying any legitimate manufacturing issues which were brought to their attention. The guarantee that was provided with each engine really meant something……….

In reality, this impression is quite unfair to Dunham Engineering. I hope that I’ve demonstrated very conclusively that the manufacture of the Dunham replicas and retros was very much a labour of love undertaken by a family of genuine enthusiasts. They put their hearts and souls into offering the best products that they could given the somewhat grassroots conditions under which they were constrained to work. And while it’s true that quality issues did undoubtedly arise from time to time with specific examples of their products, this is equally true of many far more prominent model engine ranges. Moreover, Dunham Engineering invariably stood behind their work by remedying any legitimate manufacturing issues which were brought to their attention. The guarantee that was provided with each engine really meant something………. Several thousands of their engines survive today as a testament to the generally very successful results of their efforts.

Several thousands of their engines survive today as a testament to the generally very successful results of their efforts.