|

|

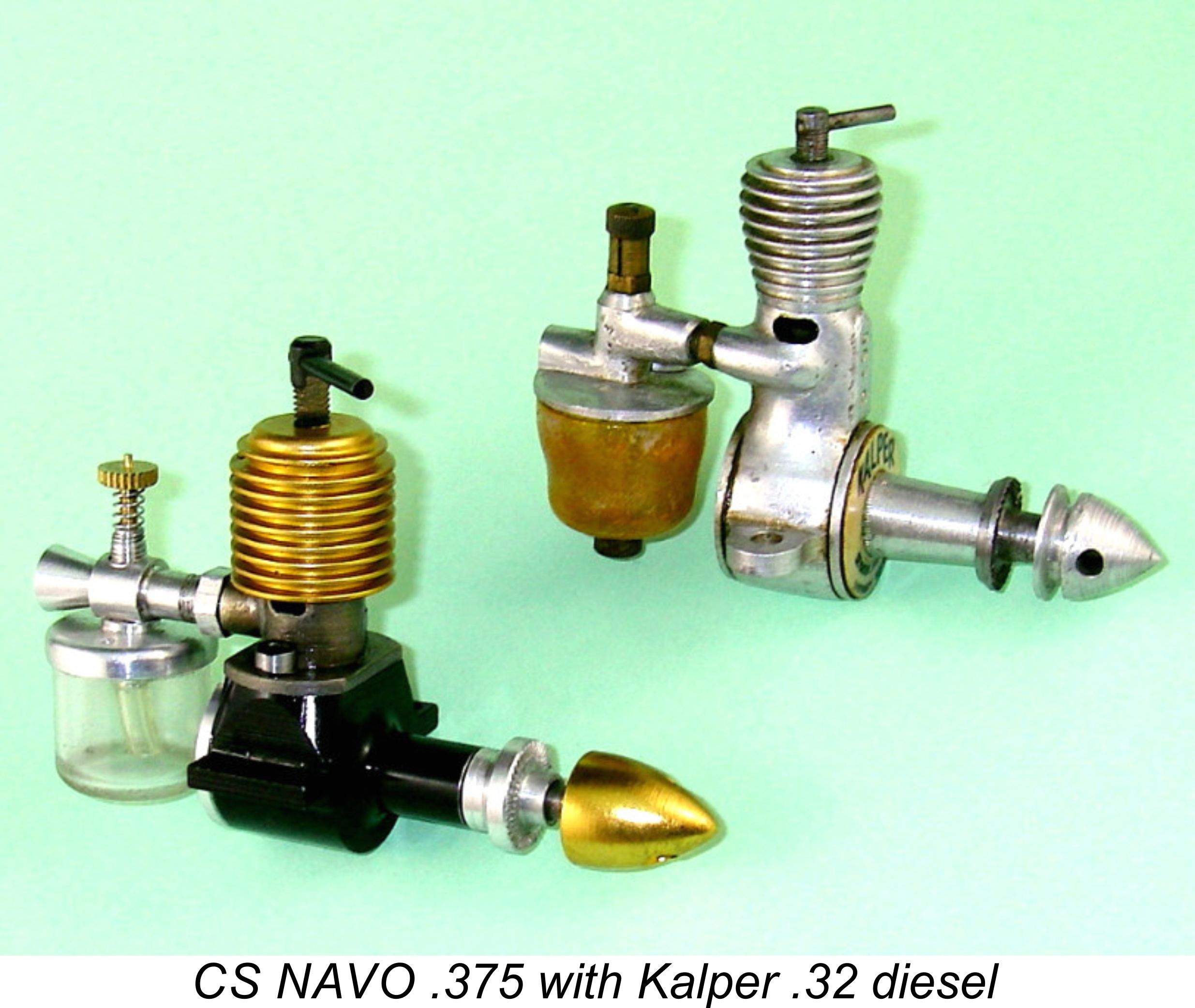

Oriental Gem - the CS NAVO .375 Diesel

The CS company was founded by Mr. Gao Guo Jun, a former Chinese champion in the very competitive F2A control line speed category. In 2007, Mr. Gao was joined in the CS venture by Mr. Peng Han, who took over the day-to-day running of the business at that point. I am extremely grateful to Han (who likes to be known as Hans by his International friends) for his very kind cooperation in helping to assemble the material for this and other articles. Hans is a genuine enthusiast, with whom it has always been a pleasure to correspond.

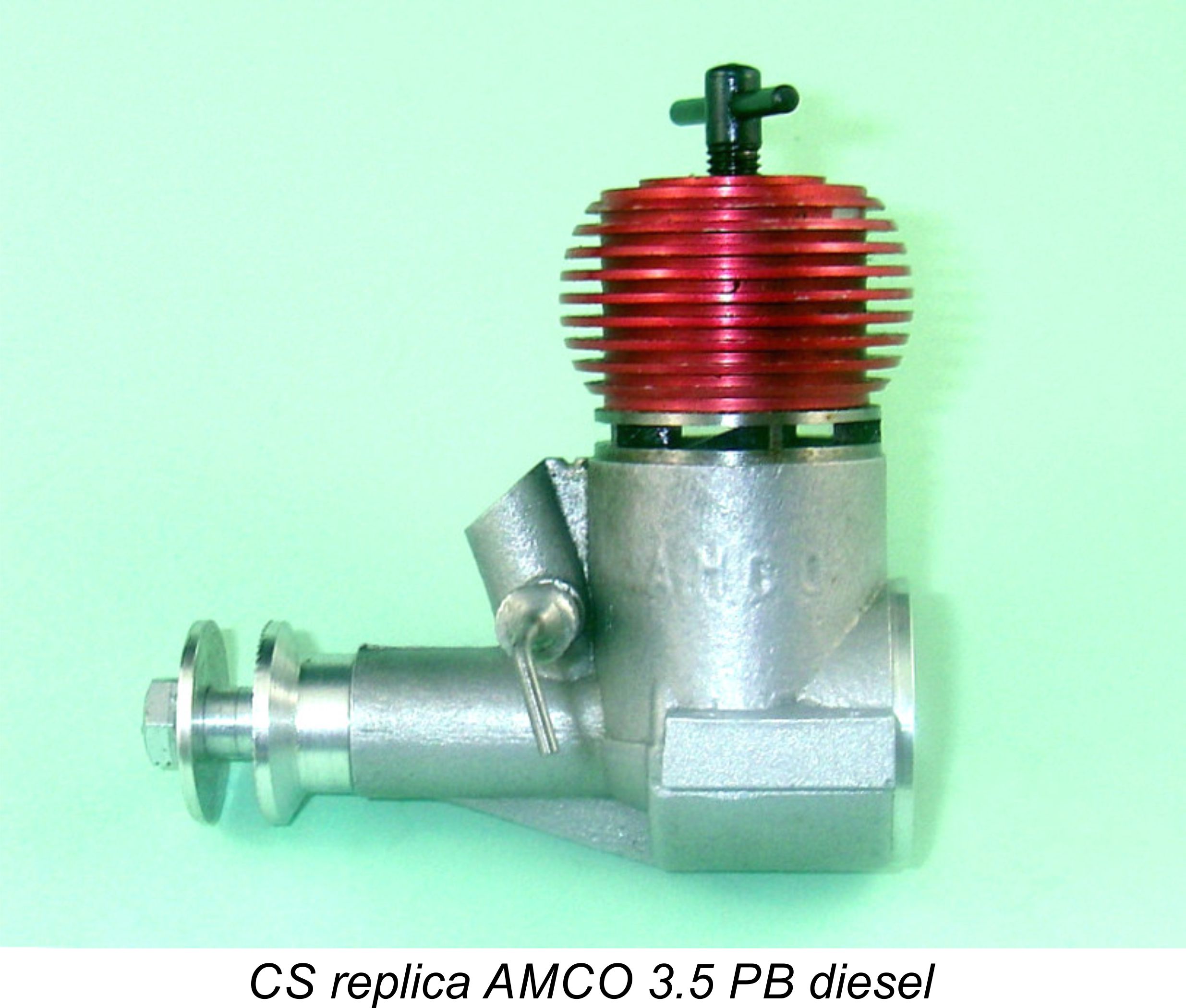

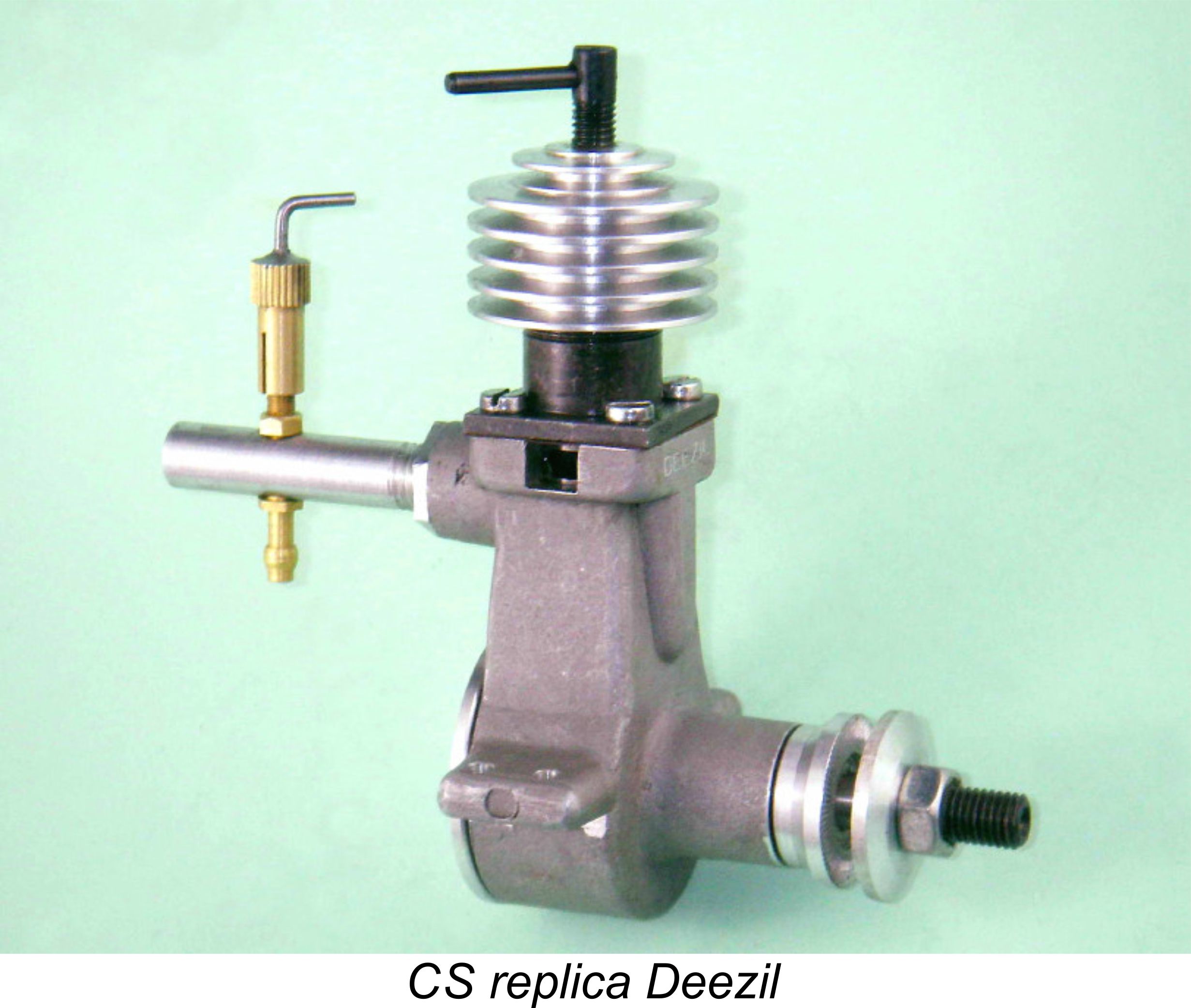

Production capacity was surprisingly small - around 50 engines per month as of April 2014. Hans told me that demand was still running at over 1000 units annually at that time, a Sadly, the ongoing retrenchment of the world market for model I/C engines as a result of the seemingly unstoppable takeover by soul-less electric powerplants eventually forced the company to terminate all model engine production in September of 2015. I for one viewed this as a great loss to the worldwide model engine enthusiast community. I am among those who believe firmly The range of classic model diesel replicas produced by CS over the years eventually grew to impressive proportions. Examples of such models which were replicated included the Elfin 249 plain bearing model in both beam and radial mount versions, the Barbini B.38 1 cc diesel, the plain bearing AMCO 3.5, the Oliver Tiger Mk. III and Tiger Cub Mk. II (albeit under different names for proprietary reasons), the Micro Diesel, the infamous Deezil, the Chinese Silver Swallow and Jin Shi 2.5 cc models, the Rivers Silver Streak Mk. II, several members of the Mills range and the E.D. 3.46 cc Mk. IV Hunter. The degree to which these various models actually replicated the originals varied somewhat, but all of them served their intended purpose well in allowing more of us to experience the pleasures of running these classic model engine designs.

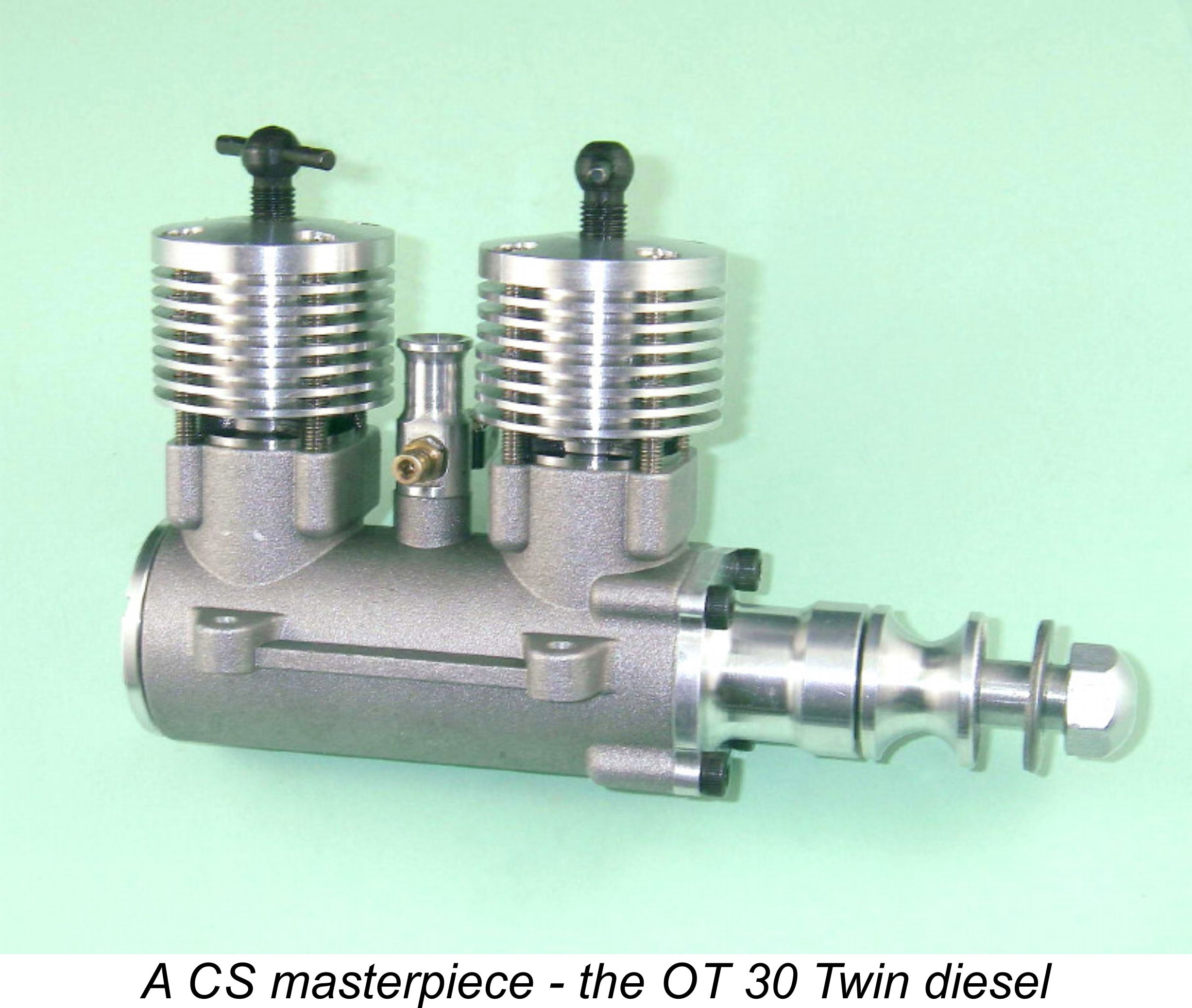

In addition to producing classic replicas such as those noted above, CS also developed a number of Another very interesting offering which was under development at my original time of writing was an in-line twin cylinder side-port NAVO diesel model of 2 cc displacement. A few prototypes of this fascinating design were produced, but the decision to terminate all model engine production ended any chance of its appearing in commercial form. A great loss to the model engine community.........

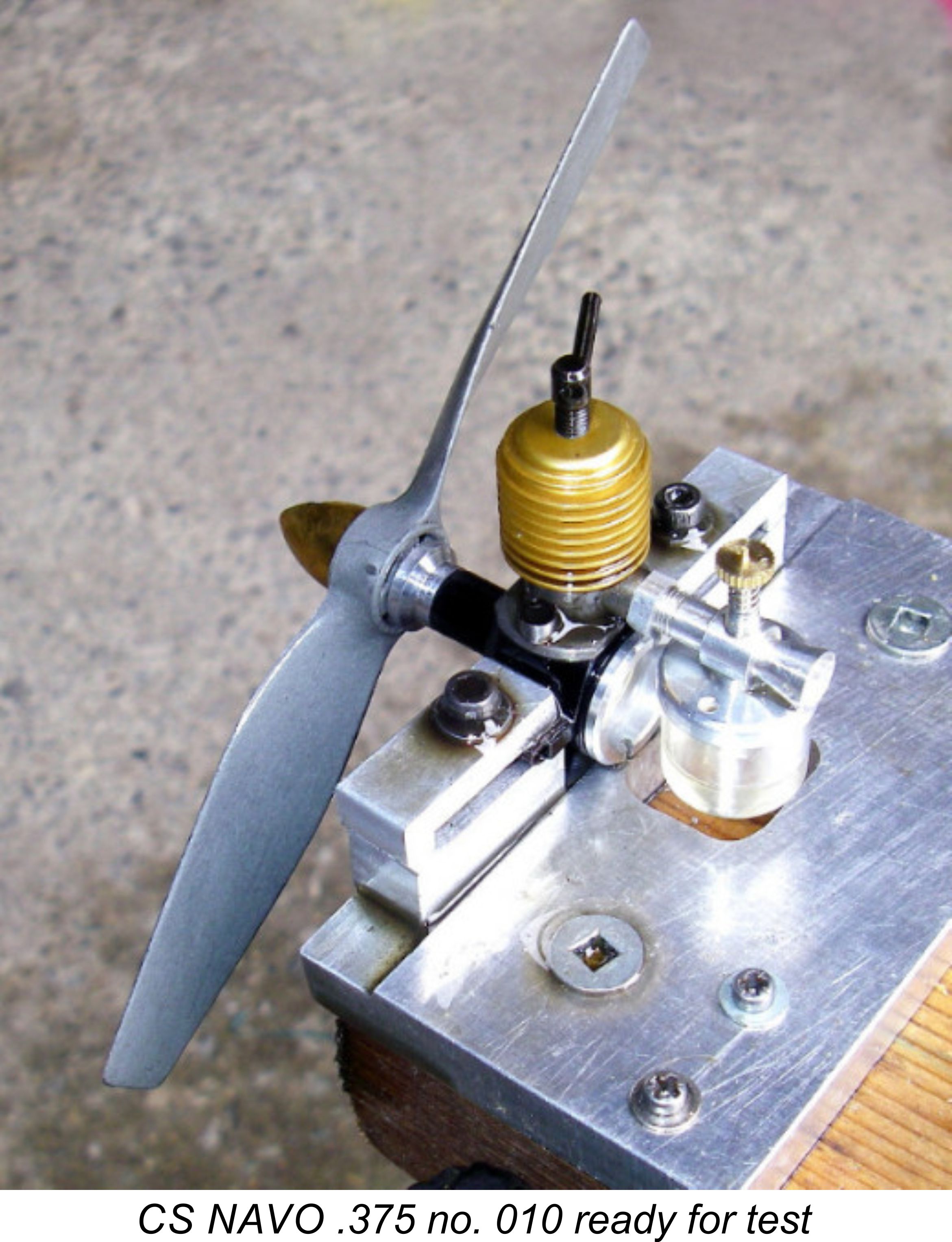

Having outlined the history of the CS venture, in the balance of the present article I’ll focus on the smallest member of CS’s NAVO series of side-port engines which were broadly based upon the classic Mills diesels from England. CS marketed a number of As of the original time of writing in mid-2014, the smallest member of the NAVO range was the 0.375 cc model which is the main subject of this article. Production of this model was confined to a limited edition of only 22 examples. My own test engine is number 010 of this now highly collectible series. The intention had been to prduce this model in a somewhat larger series, but this goal fell by the wayside when all CS model engine production ceased in September 2015. Let's have a closer look and see what we all lost.................. Description

First impressions on taking the engine out of the box are that this is a very handsome little motor indeed. The gold anodizing on the cooling jacket and spinner is set off most attractively by the black-anodized crankcase and the polished aluminium prop driver, backplate and tank components.

A few vital statistics should be noted at the outset. The engine features measured bore and stroke dimensions of 6.90 mm and 10.0 mm respectively for a displacement of 0.374 cc (0.023 cuin.). The resulting stroke/bore ratio of 1.45:1 is unusually high, being exceeded by only a few The NAVO .375 is constructed around a cleanly-machined barstock case which is black-anodized. Unlike the Mills, the installation flange for the steel cylinder is located well below the induction and exhaust ports, being secured to the crankcase using two Allen-head machine screws. A short spigot protrudes below this flange to locate the cylinder securely in the case.

The one-piece steel crankshaft features a simple unbalanced disc-form crankweb. The shaft is a very close fit in its plain bearing, with just the right amount of detectable dry clearance to ensure adequate lubrication and cool running.

The engine is completed by a handsome gold-anodized cooling jacket and spinner nut. Overall, the engine’s appearance is very pleasing indeed. In terms of the little NAVO’s operating parameters, the following approximate figures were measured: Exhaust opens 110 degrees ATDC - total exhaust period 140 degrees There is also a period of sub-piston induction of around 15 degrees either side of TDC for a total period of 30 degrees. This seems to be a leaf taken out of the E.D. and Allbon sideport design books.

I commented earlier on the somewhat chequered reputation that CS acquired over the years in terms of quality control. This being the case, particular attention was paid to this issue during the present review. The engine had clearly been test-run at the factory - the delicious aroma that emanated from the It must also be said that all fits in this example of the NAVO .375 were found to be superb. This is particularly true of the piston/cylinder fit, which becomes an increasing challenge to get right as the bore decreases. The fit in my illustrated example is exceptional for such a small engine - perfect compression seal with no trace of “stiction” at any point in the stroke. My objective overall comment is that this is undoubtedly the best-made CS engine of my present and previous acquaintance. It is the first CS engine that has passed through my hands that has required no intervention whatsoever, being all ready to run as received. Fair enough - full marks to CS for one of their best-ever production jobs. How does it run?? Well, the engine was produced primarily as a collector’s piece, hence probably not being expected to do much if any running. However, that’s never stopped me - let’s head for the test bench! The CS NAVO .375 on Test For the purposes of this test I brewed up a fresh batch of my standard small-bore diesel mix. Model diesels of less than 0.5 cc (0.030 cuin.) displacement typically show a marked preference for a fuel having a higher-than-normal ether content. They also need an elevated oil content to look after the very small bearing surfaces and maintain a good compression seal. I have generally had good results with a fuel consisting of 40% ether, 30% kerosene and 30% castor oil with the addition of up to 2% ignition improver to the overall mix. Not a high performance brew by any means, but it does promote good starting and wearing qualities in very small diesels. This was the fuel used in the present test.

The airscrews to be used were selected on the basis of past experience with small sideport diesels of this type. I was expecting this engine to develop pretty good torque for its displacement, selecting my test props accordingly. As it turned out, my expectations were a little optimistic ……… Starting proved to be almost absurdly easy - in fact, the engine actually started on the third flick! However, I had made the assumption that a fairly substantial prop would suit this little engine, accordingly beginning with an APC 7x4 glass fibre prop - quite a hefty load for an engine this small. On this prop, it proved rather difficult to establish a needle setting at which the engine would run the tank out cleanly - the tendency was for the unit to hunt rather than to maintain a steady speed. Moreover, it was readily apparent to an experienced ear that even if running could be smoothed out, the performance on this prop would be rather marginal at best - it simply wasn’t “happy” on this load. It appeared in fact that the engine was rather less of a torque producer than I had expected. I did eventually obtain a reasonably steady run from which a representative speed could be measured, but the needle setting to achieve this was mega-critical at around 1¾ turns. The engine clearly wanted to run at higher speeds. Once I switched to an APC 6x4 glass fibre prop, things improved dramatically. A dependable needle setting could easily be established, although the optimum setting remained rather critical. However, once the correct setting was found, running qualities were excellent - the engine ran the tank out very steadily. The contra piston proved to be if anything a little tightly fitted but held its settings firmly while never at any time sticking in the bore. Hence compression settings were easily optimized. The fuel tank proved to have ample capacity, giving a leaned-out run of some 100 seconds.

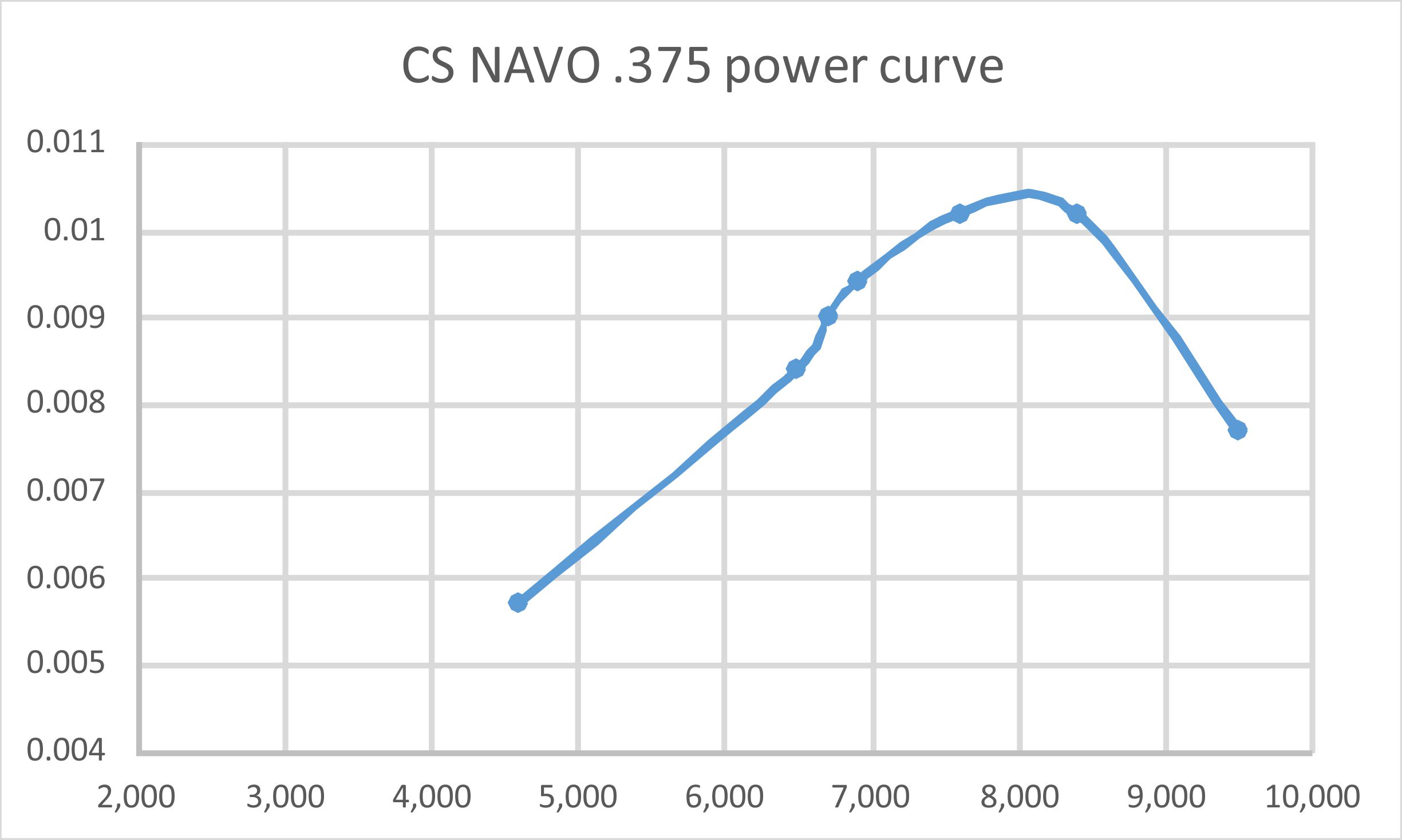

I ended up testing the engine over a fairly wide speed range from 4,600 rpm all the way up to 9,500 rpm. To achieve the latter speed, I had to use the infamous D-C nylon 5¼x3½ flea-swatter which was expressly designed to make the amazingly gutless D-C Bantam sound good on the bench rather than actually move air. However, it must be said that the faster it ran, the happier the little NAVO seemed. In particular, the optimum needle setting became progressively better defined as the speed went up - the reverse of the usual trend. Although it was clear that this example of the engine had done some running at the factory before coming into my possession, I naturally had no idea how much running time it had undergone. Although it felt absolutely superb right from the outset, I elected in fairness to the manufacturers to put on a little more time prior to commencing the actual test. Having learned from experience that the APC 6x4 prop suited the engine very well, I put on a number of additional runs on that prop to allow things to settle down. Then I took rpm readings for the selected range of test props, with the following results:

The power curve derived from these figures implies a peak output of around 0.0104 BHP @ 8,000 rpm. Not a stellar performance by any means, but a perfectly acceptable output for the kind of service to which an engine of this displacement and layout might be applied. The implied specific output of 0.027 BHP/cc is not all that far out of line with the figure of 0.030 BHP/cc reported by “Aeromodeller” magazine in their June 1952 test of the very similarly-designed 0.246 cc Kemp Hawk. I could easily identify a number of potential modifications to ths design which would almost certainly improve performance considerably. However, that's not the point - this is never going to be a high performance engine, nor was it intended for that role. Hence I elected to leave it in its original state to serve as a witness to the unaided capabilities of CS. During the classic era to which this engine belongs in spirit, very small diesels of this type were typically used to substitute for rubber power in small free flight models which had been originally designed for the latter form of propulsion. For such purposes, the little NAVO would be a perfectly acceptable performer. A 6x3 prop would probably be the ideal airscrew for such applications, allowing the engine to peak in the air. We must also remember that this engine was produced by CS as a limited collector’s edition, presumably with the expectation that few of the engines would actually be run. The fact that the engine does run, and very well at that, is very much to the credit of CS. The little NAVO came through its test with flying colours. No problems of any kind developed during the test, nor was there any evidence of rapid wear on any component. I got the impression that if suitable fuel were used along with a conservative approach to engine management, this very well-made little unit would actually give long and dependable service in a practical flying application. Conclusion

___________________________________________

Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, BC, Canada First published December 2014 |

||

| |

The CS company from Shanghai, China is well remembered by most individuals who have taken an active long-term interest in model engines. Beginning with its establishment in 1978 as a manufacturer of world-class competition engines, the company increasingly specialized in the manufacture of replicas and look-alikes of classic model diesel engines from the earlier years of post-WW2 power modelling.

The CS company from Shanghai, China is well remembered by most individuals who have taken an active long-term interest in model engines. Beginning with its establishment in 1978 as a manufacturer of world-class competition engines, the company increasingly specialized in the manufacture of replicas and look-alikes of classic model diesel engines from the earlier years of post-WW2 power modelling.  The factory in Shanghai where the CS engines were produced was far smaller than might be supposed. However, it was well equipped with an adequate inventory of up-to-date CNC machine tooling. As of 2014 when I wrote the original text of this article, the workforce was also quite small, consisting of only four employees in addition to Hans himself. Hans was in fact very much a part-timer at the factory, since he is not in fact a skilled model engineer - his main career is in the banking industry. This venture was very much a labor of love as opposed to a focused money-making initiative.

The factory in Shanghai where the CS engines were produced was far smaller than might be supposed. However, it was well equipped with an adequate inventory of up-to-date CNC machine tooling. As of 2014 when I wrote the original text of this article, the workforce was also quite small, consisting of only four employees in addition to Hans himself. Hans was in fact very much a part-timer at the factory, since he is not in fact a skilled model engineer - his main career is in the banking industry. This venture was very much a labor of love as opposed to a focused money-making initiative. demand which the company was unable to fulfill at then-current staffing and equipment levels. Evidently the rising cost of skilled labor in China precluded the hiring of more staff, besides which the company's machine tool inventory was insufficient to allow for an expanded workforce. Hans advised that at my original time of writing (mid 2014) he was considering the option of contracting out the manufacture of certain components.

demand which the company was unable to fulfill at then-current staffing and equipment levels. Evidently the rising cost of skilled labor in China precluded the hiring of more staff, besides which the company's machine tool inventory was insufficient to allow for an expanded workforce. Hans advised that at my original time of writing (mid 2014) he was considering the option of contracting out the manufacture of certain components. that the very sincere efforts of CS to bring us interesting replicas and original products richly deserved to be supported and encouraged by the model engine community. Warts or no, we were far better off with these engines than without them! It's too bad that the company did not receive the customer support which I sincerely believe that they deserved.

that the very sincere efforts of CS to bring us interesting replicas and original products richly deserved to be supported and encouraged by the model engine community. Warts or no, we were far better off with these engines than without them! It's too bad that the company did not receive the customer support which I sincerely believe that they deserved.  In making these replicas and look-alikes available, CS provided an immense (and in my view grossly under-appreciated) service to the classic modelling movement. Although the company’s products acquired a not-undeserved reputation for inconsistent quality over the years, the fact remains that most examples of any CS product could be made to work very well indeed through some knowledgeable and suitably-equipped intervention on the part of the owner. This undeniably made a typical example of these engines something of an “engine guy’s special”. Indeed, over the years many people, myself included, tended to view these engines as supplied in the light of “kits” requiring some effort on our part to get them sorted. I actually derived a great deal of personal satisfaction from getting them just right!

In making these replicas and look-alikes available, CS provided an immense (and in my view grossly under-appreciated) service to the classic modelling movement. Although the company’s products acquired a not-undeserved reputation for inconsistent quality over the years, the fact remains that most examples of any CS product could be made to work very well indeed through some knowledgeable and suitably-equipped intervention on the part of the owner. This undeniably made a typical example of these engines something of an “engine guy’s special”. Indeed, over the years many people, myself included, tended to view these engines as supplied in the light of “kits” requiring some effort on our part to get them sorted. I actually derived a great deal of personal satisfaction from getting them just right! This of course took nothing away from the fact that, thanks to CS’s ongoing activities, these engines

This of course took nothing away from the fact that, thanks to CS’s ongoing activities, these engines  CS were of course well aware of the quality control criticisms which were levelled against their products over the years. From my own personal contacts with the company, I was satisfied that they were making sincere efforts to respond to these criticisms. Indeed, there was a noticeable improvement over time, which I am sure would have continued if the company had been able to remain in the model engine business. Moreover, both in my direct experience and that of others, CS stood behind their products by moving quickly to resolve any un-fixable issues with a given example of their work.

CS were of course well aware of the quality control criticisms which were levelled against their products over the years. From my own personal contacts with the company, I was satisfied that they were making sincere efforts to respond to these criticisms. Indeed, there was a noticeable improvement over time, which I am sure would have continued if the company had been able to remain in the model engine business. Moreover, both in my direct experience and that of others, CS stood behind their products by moving quickly to resolve any un-fixable issues with a given example of their work. original designs of considerable technical interest. Chief among these was their outstanding 5 cc (0.29 cuin.) OT 30 Twin diesel model based on their Oliver Tiger 2.5 cc (.15 cuin.) replica. A

original designs of considerable technical interest. Chief among these was their outstanding 5 cc (0.29 cuin.) OT 30 Twin diesel model based on their Oliver Tiger 2.5 cc (.15 cuin.) replica. A  Apart from the previously-mentioned OT 30 Twin, one other twin cylinder model which did reach production was the "Boddo Twin" 1.5 cc diesel based on a pair of CS's NAVO .75 piston/cylinder assemblies. This neat little twin was commissioned by CS's English distributor Dave Boddington in 2009, not long prior to his untimely death in 2010 from cancer. These twins were numbered, with only 300 examples being made.

Apart from the previously-mentioned OT 30 Twin, one other twin cylinder model which did reach production was the "Boddo Twin" 1.5 cc diesel based on a pair of CS's NAVO .75 piston/cylinder assemblies. This neat little twin was commissioned by CS's English distributor Dave Boddington in 2009, not long prior to his untimely death in 2010 from cancer. These twins were numbered, with only 300 examples being made.

The CS NAVO .375 cc diesel was supplied in a durable metal box with a sturdy foam insert and plastic bag to protect the engine. No instructions were provided - the only literature was a certificate of authenticity confirming that the engine formed part of a limited edition of only 22 examples, which were expressly stated to be intended for collectors. The engine’s serial number and date of manufacture were also included on the certificate, which was signed in Latin characters by Peng Han.

The CS NAVO .375 cc diesel was supplied in a durable metal box with a sturdy foam insert and plastic bag to protect the engine. No instructions were provided - the only literature was a certificate of authenticity confirming that the engine formed part of a limited edition of only 22 examples, which were expressly stated to be intended for collectors. The engine’s serial number and date of manufacture were also included on the certificate, which was signed in Latin characters by Peng Han. The NAVO .375 is in many ways a half-sized look-alike of the original Mills .75 model with the cylinder attached to the case by machine screws rather than being dropped into the crankcase casting as on the more familiar later version of the Mills .75. That said, the engine presents a number of original design features in which it departs from the Mills pattern. This is no slavish copy of the Mills!

The NAVO .375 is in many ways a half-sized look-alike of the original Mills .75 model with the cylinder attached to the case by machine screws rather than being dropped into the crankcase casting as on the more familiar later version of the Mills .75. That said, the engine presents a number of original design features in which it departs from the Mills pattern. This is no slavish copy of the Mills!  engines of my personal experience, such as the

engines of my personal experience, such as the  Looking at the cylinder in detail, the induction and exhaust porting follow the Mills pattern very closely, with two drilled holes at the rear serving as the induction ports and two oval exhaust apertures, one on each side. The difference is in the transfer arrangements, which in the case of the NAVO consist of a pair of neatly-formed internal bypass flutes at the front of the inner cylinder wall. These passages extend up the cylinder to overlap the exhaust ports to a significant degree.

Looking at the cylinder in detail, the induction and exhaust porting follow the Mills pattern very closely, with two drilled holes at the rear serving as the induction ports and two oval exhaust apertures, one on each side. The difference is in the transfer arrangements, which in the case of the NAVO consist of a pair of neatly-formed internal bypass flutes at the front of the inner cylinder wall. These passages extend up the cylinder to overlap the exhaust ports to a significant degree. With this system, there is no need for the step in the piston crown which was a feature of the Mills design. The NAVO’s cast iron piston is a simple cylinder with a flat crown. The gudgeon pin is a light press fit in the piston bosses, carrying a connecting rod which is very nicely machined from light alloy.

With this system, there is no need for the step in the piston crown which was a feature of the Mills design. The NAVO’s cast iron piston is a simple cylinder with a flat crown. The gudgeon pin is a light press fit in the piston bosses, carrying a connecting rod which is very nicely machined from light alloy. The induction manifold at the rear of the cylinder is a simple internally-threaded brass tube which is soft-soldered to the cylinder at the appropriate location to enclose the two drilled cylinder induction ports. An intake venturi/tank/needle valve assembly of the familiar Mills pattern threads into this manifold, being secured by a lock-nut. No cut-out is included in this assembly. The tank can of course be located at any desired angle relative to the rest of the engine in order to deal with differing mounting configurations.

The induction manifold at the rear of the cylinder is a simple internally-threaded brass tube which is soft-soldered to the cylinder at the appropriate location to enclose the two drilled cylinder induction ports. An intake venturi/tank/needle valve assembly of the familiar Mills pattern threads into this manifold, being secured by a lock-nut. No cut-out is included in this assembly. The tank can of course be located at any desired angle relative to the rest of the engine in order to deal with differing mounting configurations. An interesting feature which I have encountered before in certain designs is the fact that the induction ports open partially at around BDC as the piston crown approaches its BDC position. The opening period is pretty small - around 15 degrees either side of BDC for a total period of 30 degrees or so - but it is there nonetheless. I doubt very much that this has any effect upon the engine’s induction system since the internal cylinder pressure should be completely relieved at the point of opening. This appears to be an incidental feature arising from the combination of the engine’s internal geometry and chosen timing. The use of a higher piston crown would prevent such an opening, but the exhaust and transfer ports would need to be moved up to match, adding to the engine’s height.

An interesting feature which I have encountered before in certain designs is the fact that the induction ports open partially at around BDC as the piston crown approaches its BDC position. The opening period is pretty small - around 15 degrees either side of BDC for a total period of 30 degrees or so - but it is there nonetheless. I doubt very much that this has any effect upon the engine’s induction system since the internal cylinder pressure should be completely relieved at the point of opening. This appears to be an incidental feature arising from the combination of the engine’s internal geometry and chosen timing. The use of a higher piston crown would prevent such an opening, but the exhaust and transfer ports would need to be moved up to match, adding to the engine’s height.  plastic bag immediately confirmed as much! As a result, any shop debris which may have been introduced during assembly had long departed - the engine was internally very clean as received. However, it must be said that the working surfaces showed no signs of any damage from the presence of any such materials during the initial starts.

plastic bag immediately confirmed as much! As a result, any shop debris which may have been introduced during assembly had long departed - the engine was internally very clean as received. However, it must be said that the working surfaces showed no signs of any damage from the presence of any such materials during the initial starts. Engines of this small size are pretty much lost in a conventional test stand. It is for this reason that I made up a miniature test stand some years ago to be used for such engines. I have never regretted taking the time to make this very useful little mount. The NAVO .375 looked right at home!

Engines of this small size are pretty much lost in a conventional test stand. It is for this reason that I made up a miniature test stand some years ago to be used for such engines. I have never regretted taking the time to make this very useful little mount. The NAVO .375 looked right at home! The little NAVO turned out to be a very easy starter on a well-matched prop once the correct starting mixture was established. Its main vice, albeit one which it shares with many very small sideport diesels, was a tendency towards flooding. Provided this condition was avoided, starting presented no problems at all. A single choked flick with the needle left at its running setting was all that was required. If flooding did occur, the usual remedy of backing off compression and burning the excess out of the case, picking up compression as the excess was consumed, proved to be very effective.

The little NAVO turned out to be a very easy starter on a well-matched prop once the correct starting mixture was established. Its main vice, albeit one which it shares with many very small sideport diesels, was a tendency towards flooding. Provided this condition was avoided, starting presented no problems at all. A single choked flick with the needle left at its running setting was all that was required. If flooding did occur, the usual remedy of backing off compression and burning the excess out of the case, picking up compression as the excess was consumed, proved to be very effective.

So there we have it - a first-class effort on the part of CS which represented a sincere and unquestionably successful attempt to produce a genuinely attractive collectable which also happened to be a very nice little engine to use, if anyone cared to do so. In terms of its quality, the tested example would do credit to any series manufacturer of model diesels. If CS could have maintained a similar standard with subsequent products, they would have had nothing for which to apologize to anyone! Sadly, they never got the chance to answer this question ...........

So there we have it - a first-class effort on the part of CS which represented a sincere and unquestionably successful attempt to produce a genuinely attractive collectable which also happened to be a very nice little engine to use, if anyone cared to do so. In terms of its quality, the tested example would do credit to any series manufacturer of model diesels. If CS could have maintained a similar standard with subsequent products, they would have had nothing for which to apologize to anyone! Sadly, they never got the chance to answer this question ...........