|

|

Influential Italian - the MOVO D-2 Diesel

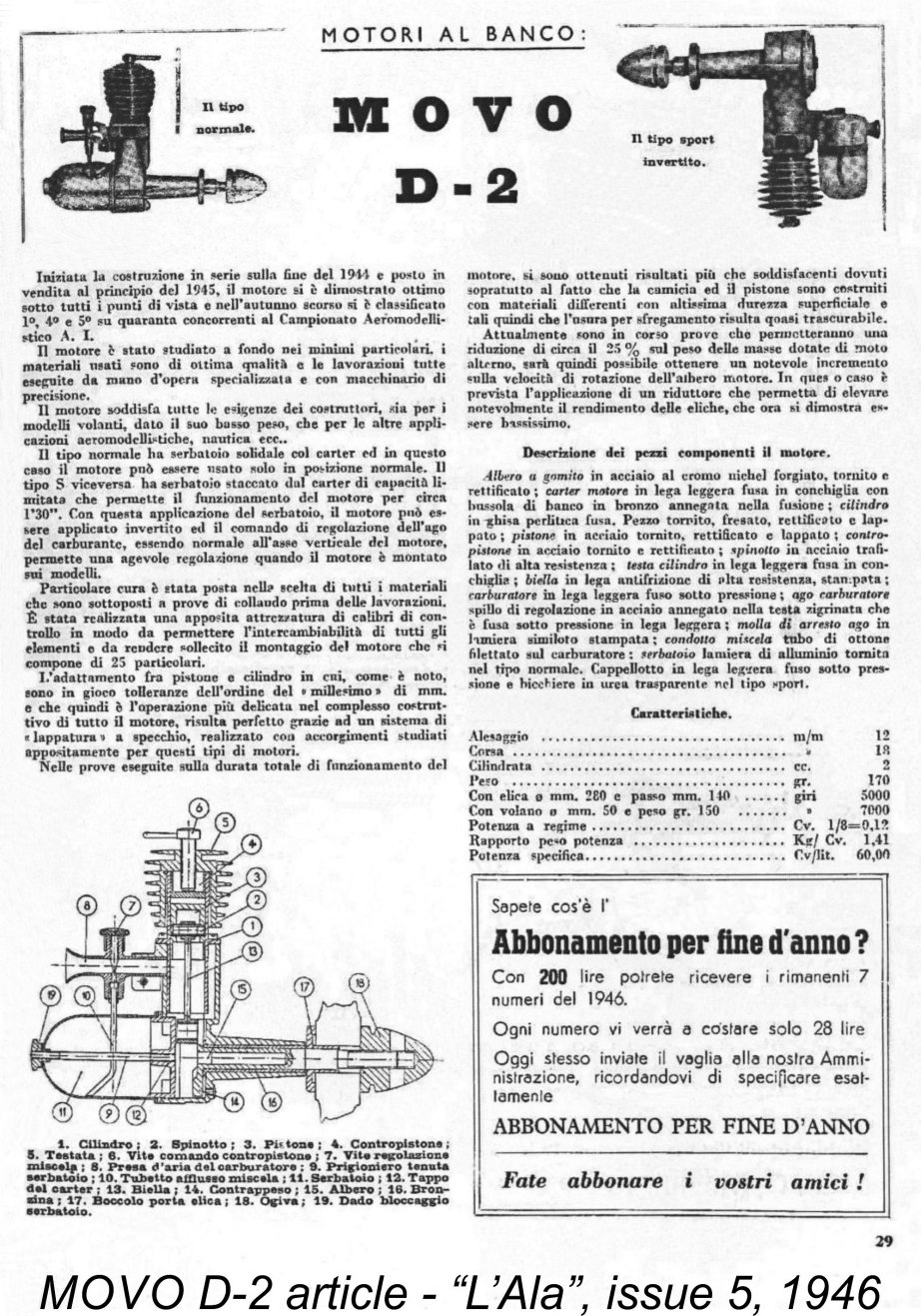

An earlier article on the MOVO D-2 may still be found on the late Ron Chernich’s now-frozen “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. Although a bit short on detail, that article represented a good introduction to the engine. Another excellent source of information regarding the MOVO is to be found in issue number 211 of the late Tim Dannels’ indispensable “Engine Collector’s Journal” (ECJ) for August 2012. This took the form of an article which was jointly prepared by Giancarlo Mensa and Tim Dannels himself. Their text included a great deal of useful information regarding the engine’s origins as well as its reception in the USA. I’m very much indebted to Giancarlo and Tim for sharing this information – thanks, guys! Another invaluable source of information on Italian model engines of the pioneering and early classic eras is the extremely informative Italian Engines website, which contains a great deal of information on such products. Much of this information can be found nowhere else. The site is presented in English, although an Italian version was planned to appear eventually. Anyone having an interest in early Italian engines is strongly recommended to check out this outstanding resource. Now, none of the above sources provided any performance information. Accordingly, a major focus of this present article will be to remedy that omission. However, before getting down to the testing I’ll take some time to summarize the background to the MOVO's very early post-WW2 appearance on the International market and place that event in context. I’ll also include a brief description of the engine. Background

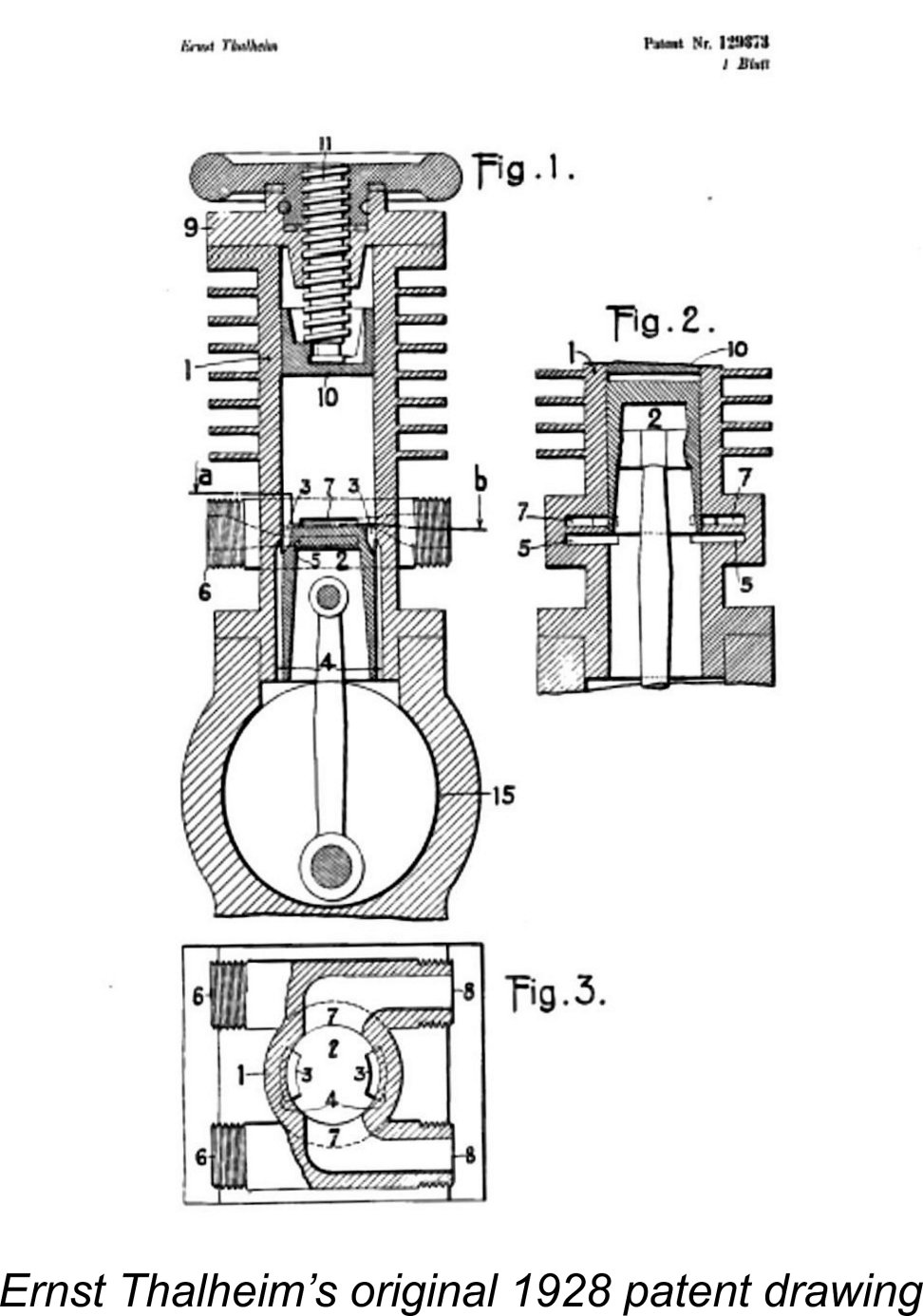

After spending the next ten years making very limited numbers of such engines for his own amusement and that of his friends, Thalheim finally went into commercial production with a series of engines which were marketed from 1938 onwards under the Etha label, derived of course from Ernst Thalheim’s name rather than from a primary ingredient of the engine’s fuel! These appear to have been the world’s first commercially-produced model diesel engines. It’s a bit of a mystery why it took Thalheim ten years to actually begin to capitalize upon his patent ……. in all probability the Great Depression which began in 1929 immediately following the issuance of the patent had something to do with it. The Etha engines were bulky, heavy and cumbersome. However, they were reportedly very competently constructed and ran well, thus proving the concept for all to see. Maris Dislers' test of a fine replica of the 2.5 cc Etha 1 model constructed by Richard Gron may be found elsewhere in this website. The engine ran very well, especially considering its 1938 design date. This being the case, it was inevitable that others would quickly follow Thalheim’s lead. The previously-mentioned Dyno 2 cc model manufactured in Alfligen, Switzerland by Klemenz-Schenk (whose primary business was the manufacture of bicycle lighting generators, hence the engine’s name) was one of the Despite the fact that by the early 1940’s most of Europe was heavily embroiled in WW2, word about this then-innovative type of model engine somehow trickled out of Switzerland along with a few examples to reach a number of other European countries. Among these countries was Italy, then heavily involved in what was becoming a very unpopular war for many Italian citizens. A number of Italian residents sought an escape from wartime concerns by tinkering with the concept of designing and constructing model diesel engines. Italy thus joined France and Czechoslovakia in becoming one of the first nations outside of Switzerland in which serious development of the model diesel concept took place. To take just one example, the celebrated Italian designer Jaures Garofali, a native of Bologna, somehow got a good look at an example of the Dyno during 1943. His previous model engine design experience had all been with spark ignition units, so this was quite an eye-opener. Although All such wartime experimentation aside, it was clear that any large-scale commercial ventures involving such products would have to wait until Italy was finally liberated from Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime and forced out of the war. This did not take place overnight – although Italy formally surrendered to the Allies by signing the Armistice of Cassibile on September 3rd, 1943 following the Allied invasion of Sicily, the Germans immediately responded by occupying the country and attacking Italian forces at a number of locations. The ensuing 20 months of fighting was some of the most bitter of the war, with very heavy casualties on both sides. It was not until April 27th, 1945 that the City of Milan in Northern Italy was finally liberated, with the Italian campaign being formally ended a few days later by the April 29th signing of the instrument of surrender by the leadership of the German Army’s Group C.

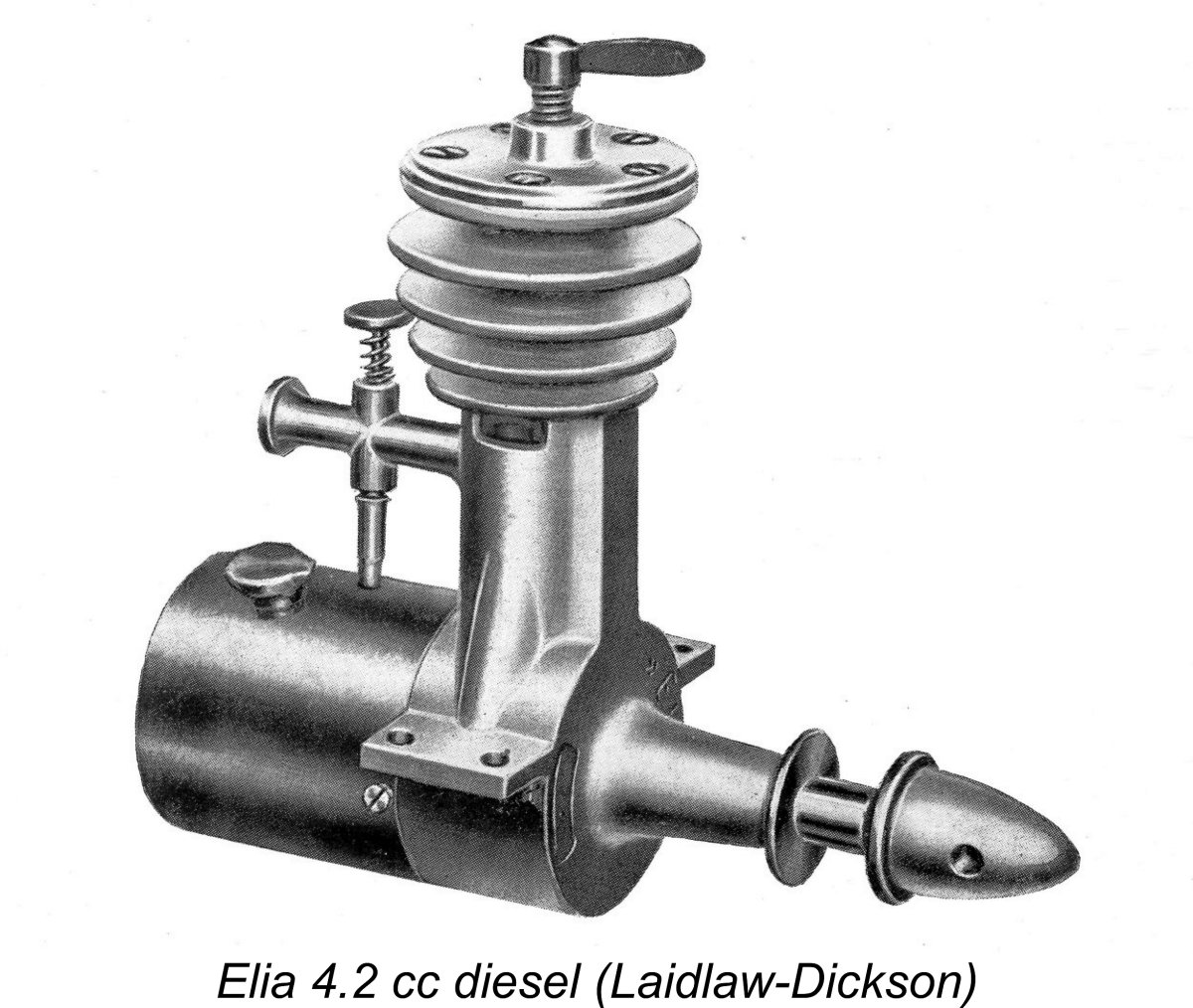

Among these were a surprising number of individuals who had ambitions to become involved in the post-war commercial manufacture of model diesel engines. Such units began to appear in small numbers even while the fighting in the north was continuing. Some of these engines ended up in the hands of Allied military personnel who eventually brought them back to their native countries following the end of the war in Europe. Among these early Italian diesels were the Alfa 1 of 1.86 cc displacement, developed by a certain Signor Mancini; the Antares 4 cc design from Padova; the Atomatic 1 cc and 4 cc models from Rome, developed by Uberto Travagli; the 2 cc P.O.2 diesel from Bergamo; the Giglio 2 cc model from Florence, developed by the Grazzini brothers; the 2 cc Micromotor Delta 1 model from Busto Arsizio; and the Folgore LN 2 of 1.99 cc displacement from Cremona. Several additional models originated in Turin in the form of the Elia 4.2 cc unit and the Helium B.6 and C.6 designs of 6 cc displacement. Italy must be seen as a real hotbed of early model diesel development – all of these engines had appeared well before the first British commercial diesels reached the market in mid 1946.

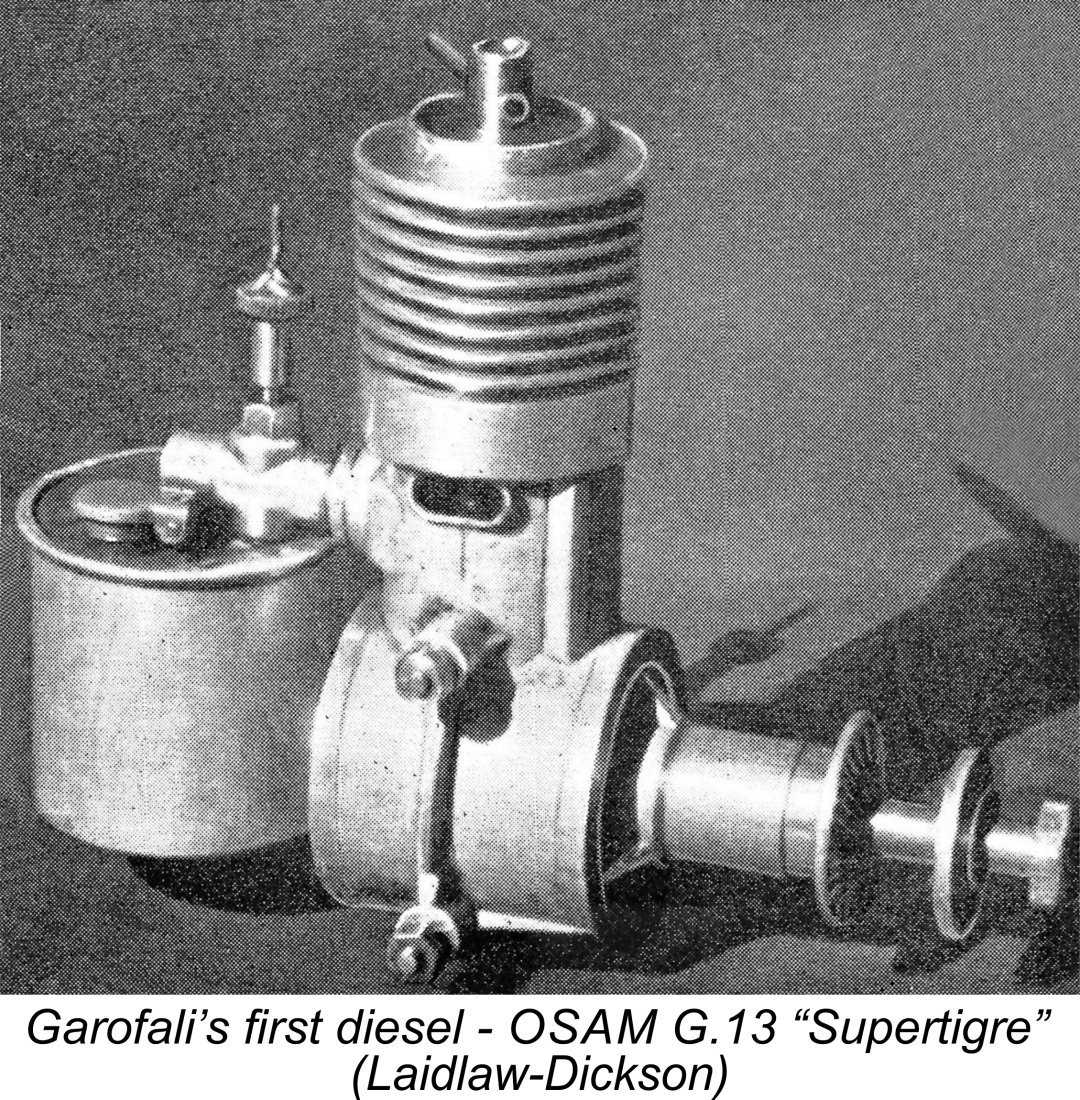

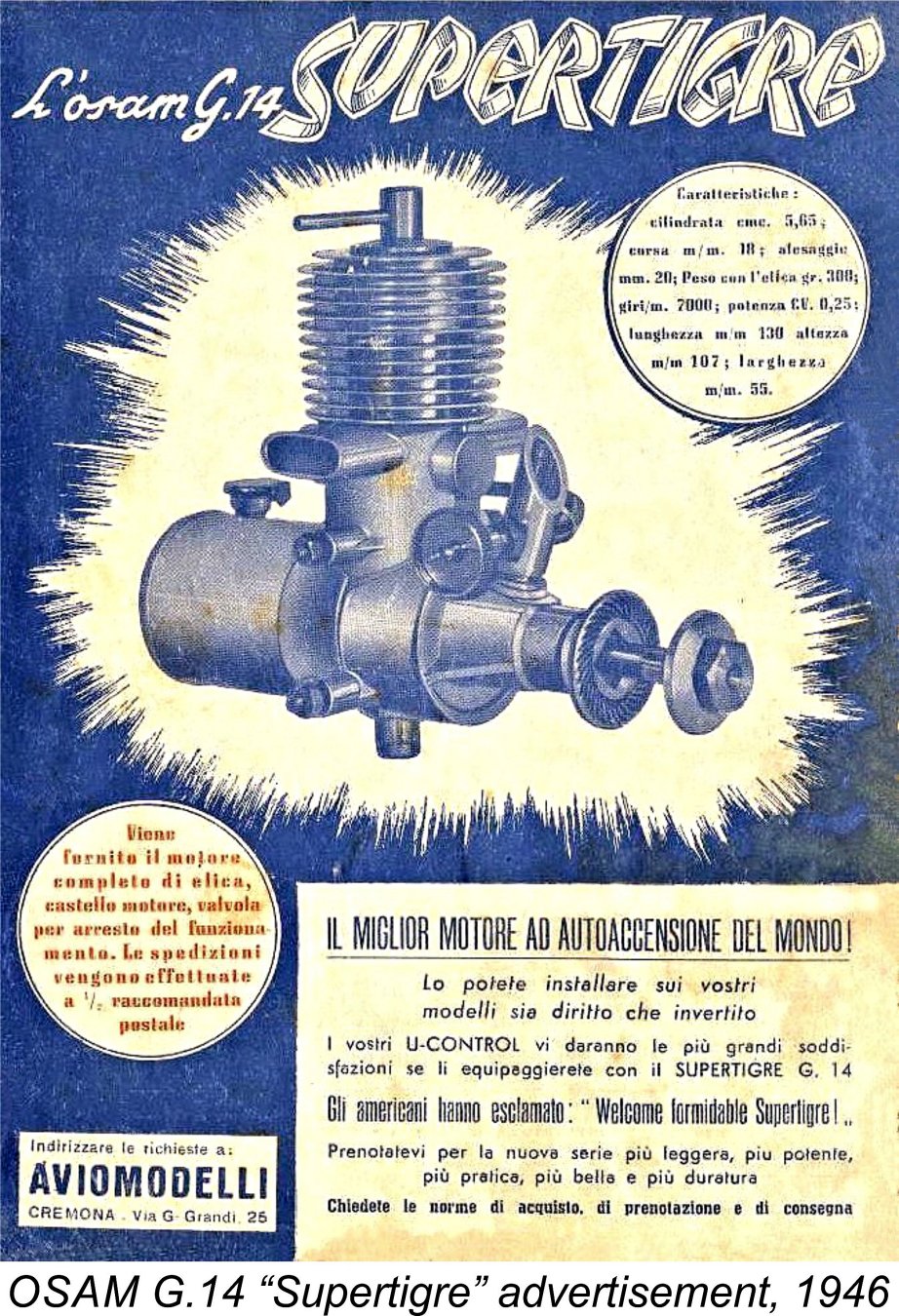

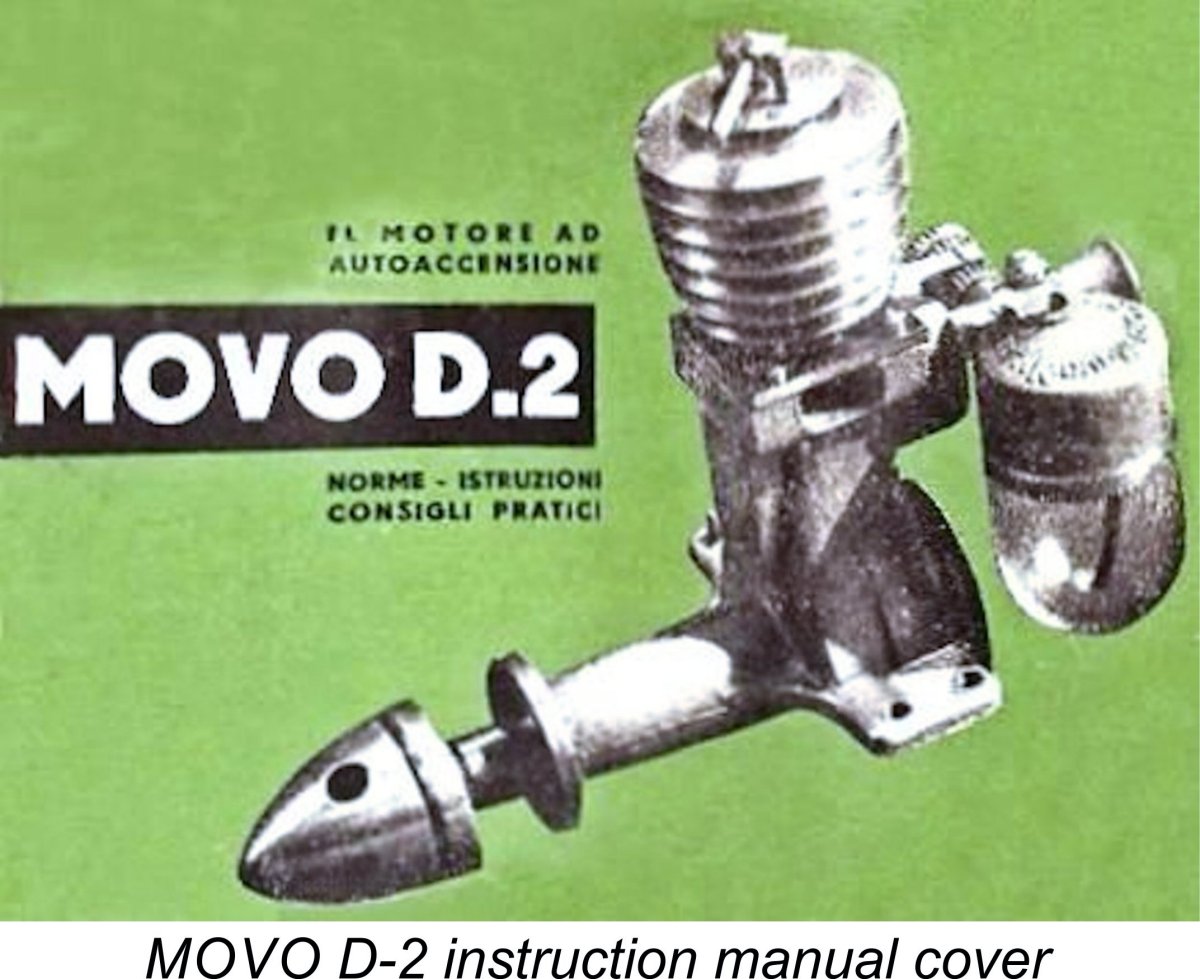

However, in order to manufacture his designs in quantity as well as market them, Garofali needed help. Acccordingly, the G.13’s immediate successor, the 1946 OSAM G.14, was produced and marketed by Signor A. Castellani’s Aviomodelli company in Cremona, which also marketed the Folgore LN 2. Interestingly enough, the OSAM G.14 was advertised with the Supertigre name prominently attached from the outset despite the fact that the emergence of Supertigre as an independent manufacturer based in Jaures Garofali’s native Bologna did not come about until 1949. Other individuals who undoubtedly had early ambitions to throw their hats into the model diesel design ring were a trio of enthusiasts named Stelio Frati, Ermenegildo Preti and Gian-Luigi della Torre. Working together during 1944 while the war in Northern Italy was still very much ongoing, they came up with the Dyno-influenced design of what was to become known as the MOVO D-2. The external styling of the engine was apparently finalized by an associate named Arve Mozzarini. He did a good job – the MOVO D-2 has an extremely pleasing and well-coordinated appearance by the standards of its era. Having come up with a design which they felt would appeal to the modelling marketplace, the design team now needed to establish a coordinated manufacturing and marketing venture. They found an individual who was willing to become involved in this way in the person of Gustavo Clerici of Milan. Signor Clerici had a small but well-equipped workshop at number 14 on a narrow Milanese street named Via Santo Spirito, a tributary of the famous Via Montenapoleone. He came up with the company name of “Modelli Volante – Milano” (Flying Models – Milan) for the model engine manufacturing venture, hence the trade-name MOVO.

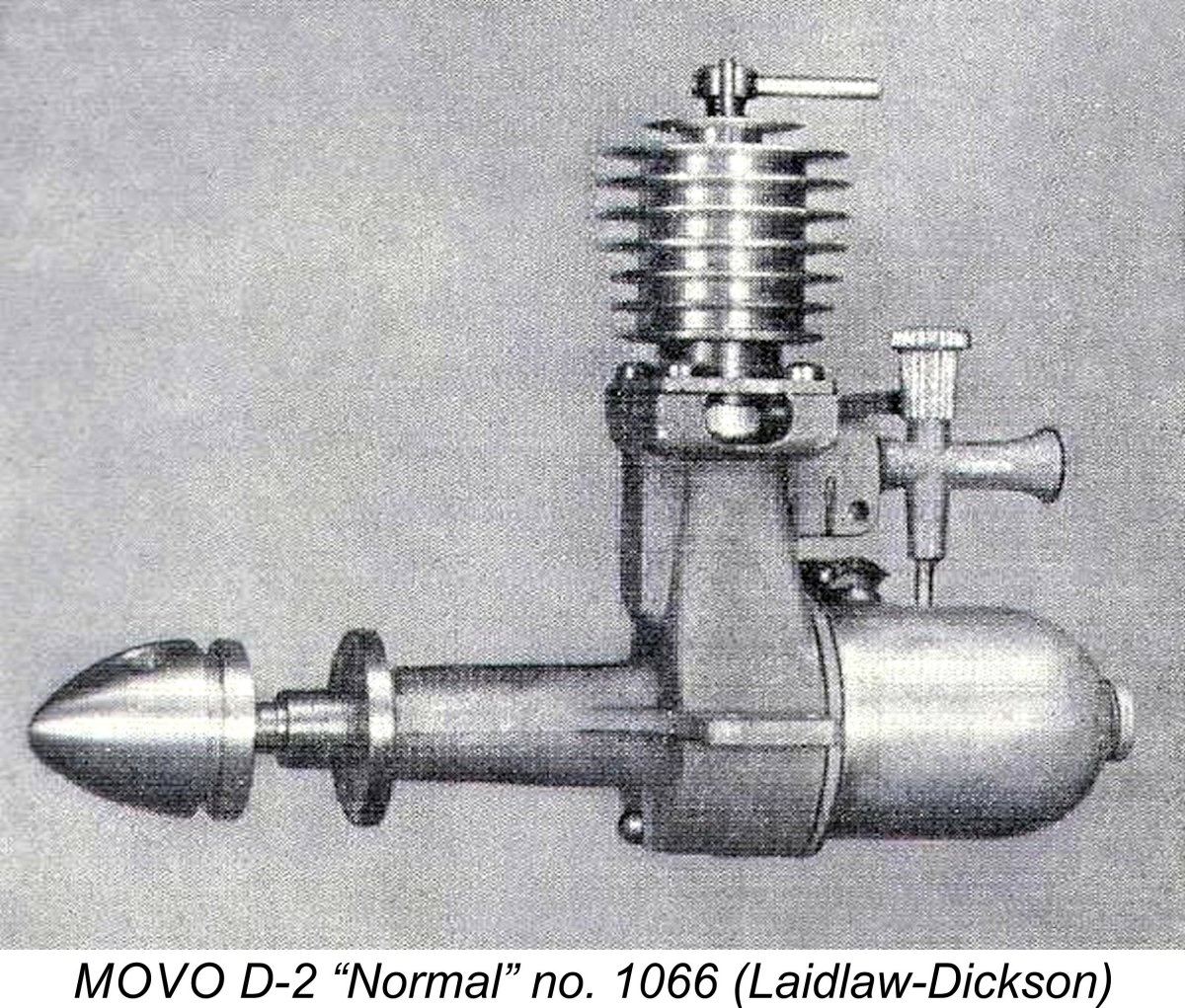

By doing this, I learned that the series production of the MOVO D-2 had commenced as early as late 1944, with sales to the public beginning in early 1945. Given the fact that Milan was still under German occupation at this time, it’s actually quite remarkable that Gustavo Clerici and his associates somehow managed to set up the required tooling, obtain supplies of material, commence series manufacture and initiate sales of their product while the occupation was still winding down. There’s a story there, but at this point in time it seems doubtful that we’ll ever learn the details……….. Regardless, this of course places the market entry of the MOVO at well over a full year prior to the appearance of the first British commercial diesels in mid 1946. This fact poses a challenge in determining a suitable comparison model to use for this test – for the first year and more of its existence, the MOVO had no British competitors. If arrangements could have been made to market the engine in Britain during late 1945 and early 1946, it would doubtless have attracted a great deal of interest. It actually seems likely that a few examples of the MOVO were brought back to England by returning military personnel who had been involved in the Italian campaigns. It’s definitely known that the staff of “Aeromodeller” magazine had an example as of 1946, since D.J. Laidlaw-Dickson’s late 1946 book entitled “Model Diesels” makes specific reference to that engine having been the subject of extensive testing by magazine staff. Presumably this was engine number 1066, of which several images appeared in the book. There’s also no doubt at all that examples of the D-2 were brought back to the USA by returning servicemen. Similar personal importations of French diesels into the USA led directly to the development of American designs such as the Drone 5 cc and Mite 1.66 cc fixed-compression models. The stories of these engines have been recounted elsewhere. Here we’ll remain focused upon the MOVO D-2. The MOVO D-2 – Description

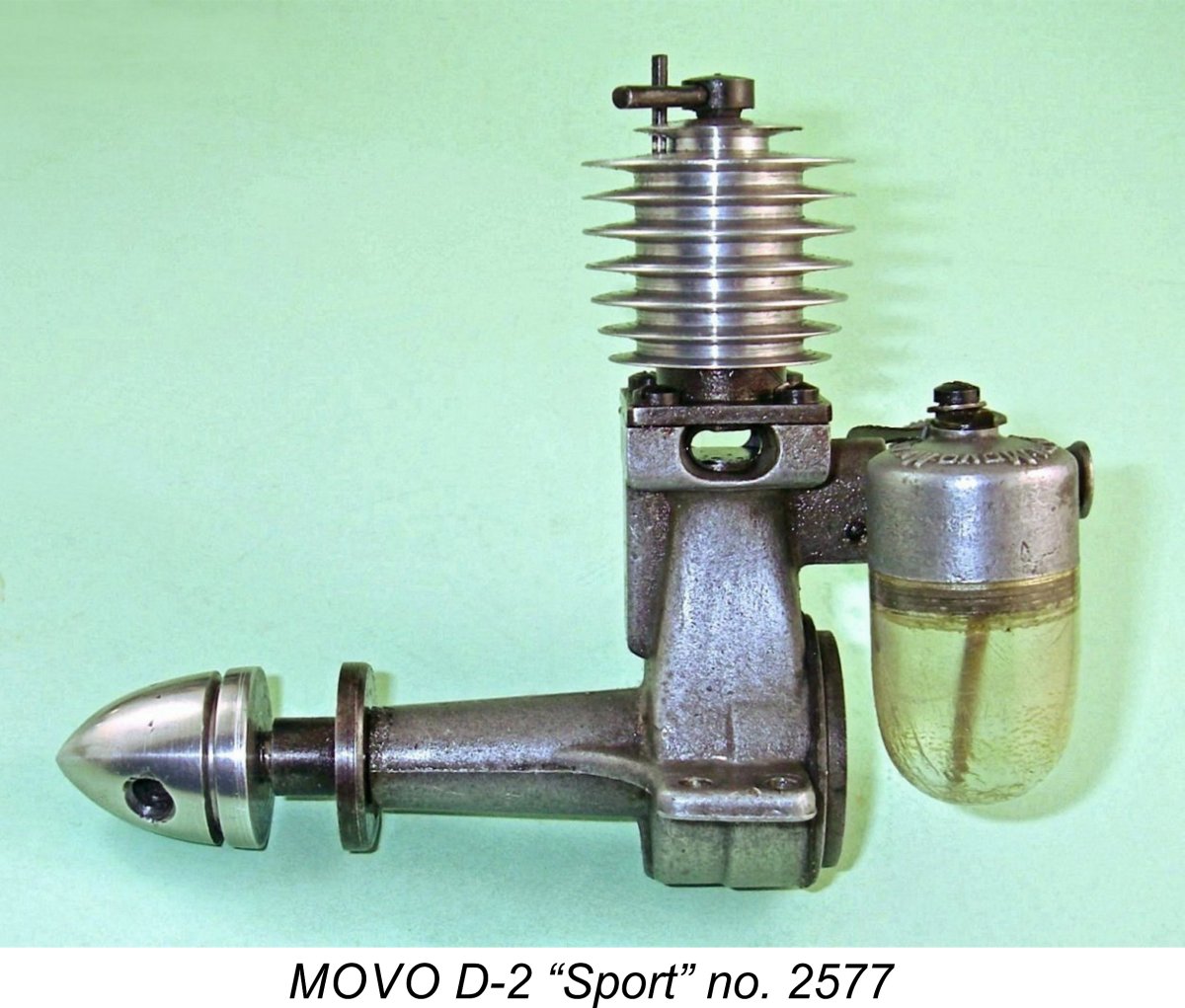

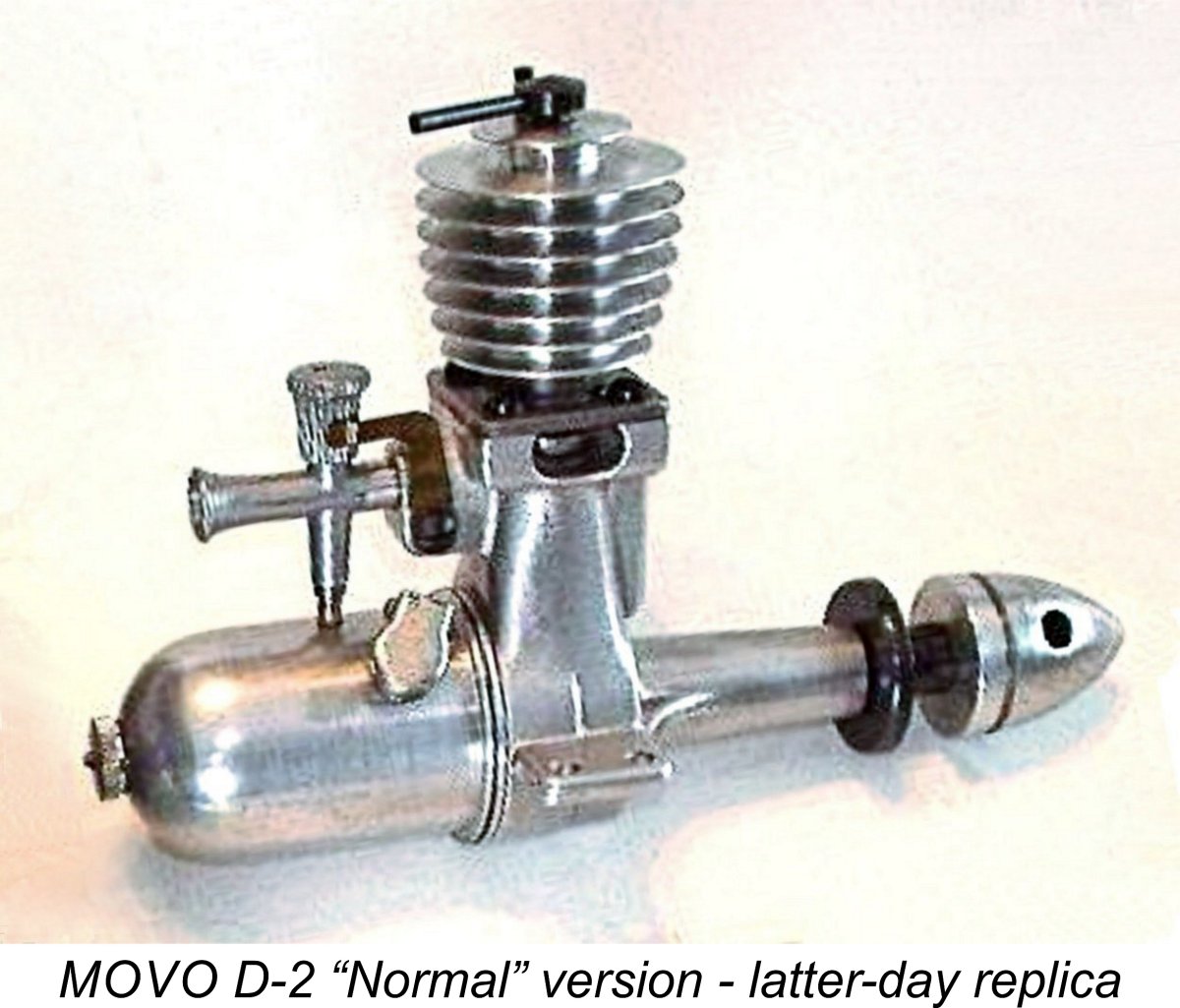

The MOVO D-2 was offered in two distinct variants – the so-called “Normal” version and the “Sport” model. In the instruction manual, the manufacturer referred to these two models as the D-2 and D-2s respectively. Engine number 2577 illustrated at the right is an example of the "Sport" model. Bore and stroke of both variants were 12.0 mm (0.472 in.) and 18.0 mm (0.709 in.) respectively for a calculated displacement of 2.04 cc (0.124 cuin.). The “Sport” version weighs a checked 166 gm (5.85 ounces). I don’t have access to an example of the “Normal” variant to check. Indeed, original examples of the “Normal” model are far less frequently encountered today than their “Sport” companions in the range.

The main differences between the two models were the widely differing tank capacities and the mounting options. The “Normal” model with its vertical fuel line could only be used in the upright configuration, but it offered a relatively long run time on a tank of fuel – between 4 and 5 minutes according to the instruction manual. This would have been the version to use in boat or car service. The “Sport” model was clearly aimed specifically at the model aircraft field. It could be used in any mounting orientation simply by slackening off the intake venturi clamp bolt and rotating the entire carburettor to suit. However, it only allowed for a run time of around 1½ minutes. Still plenty for free flight applications, of course.

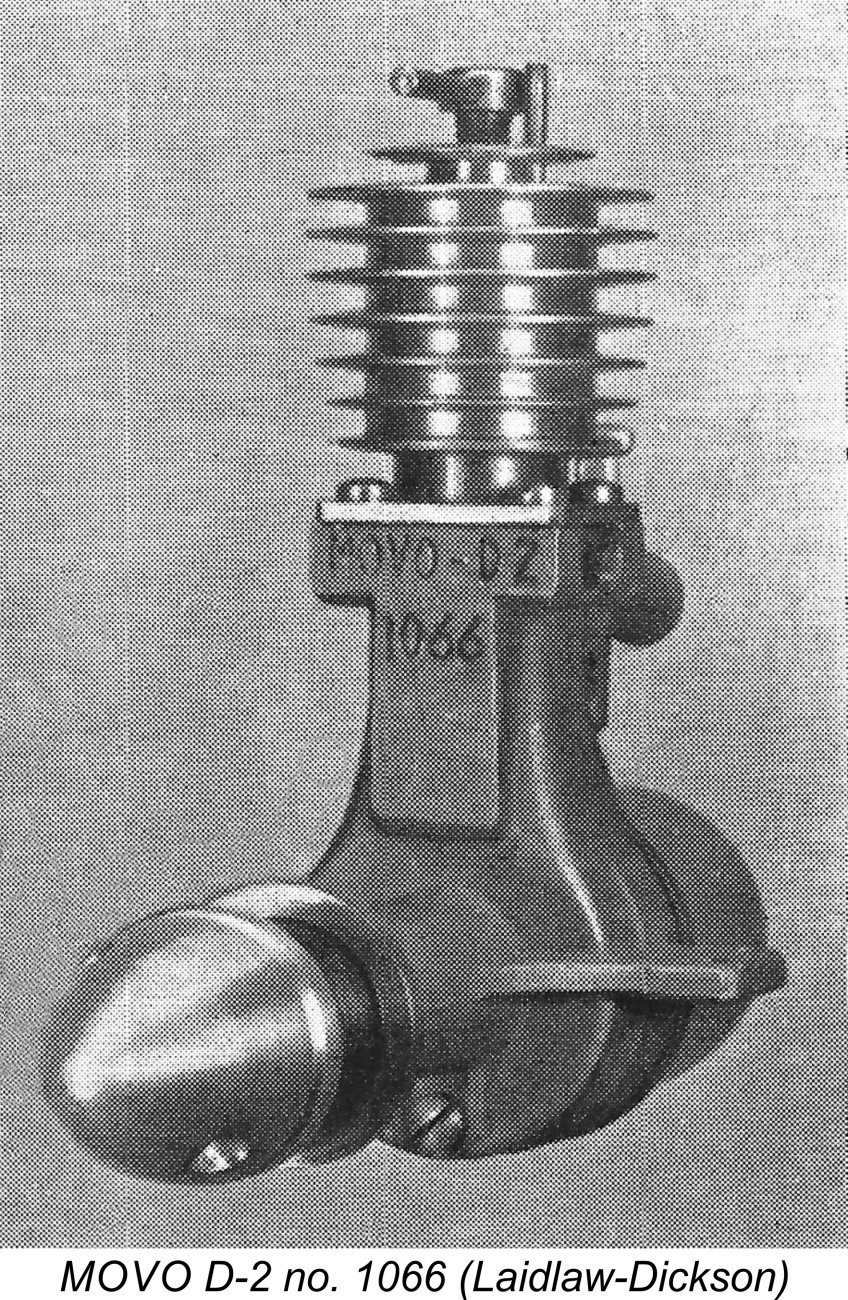

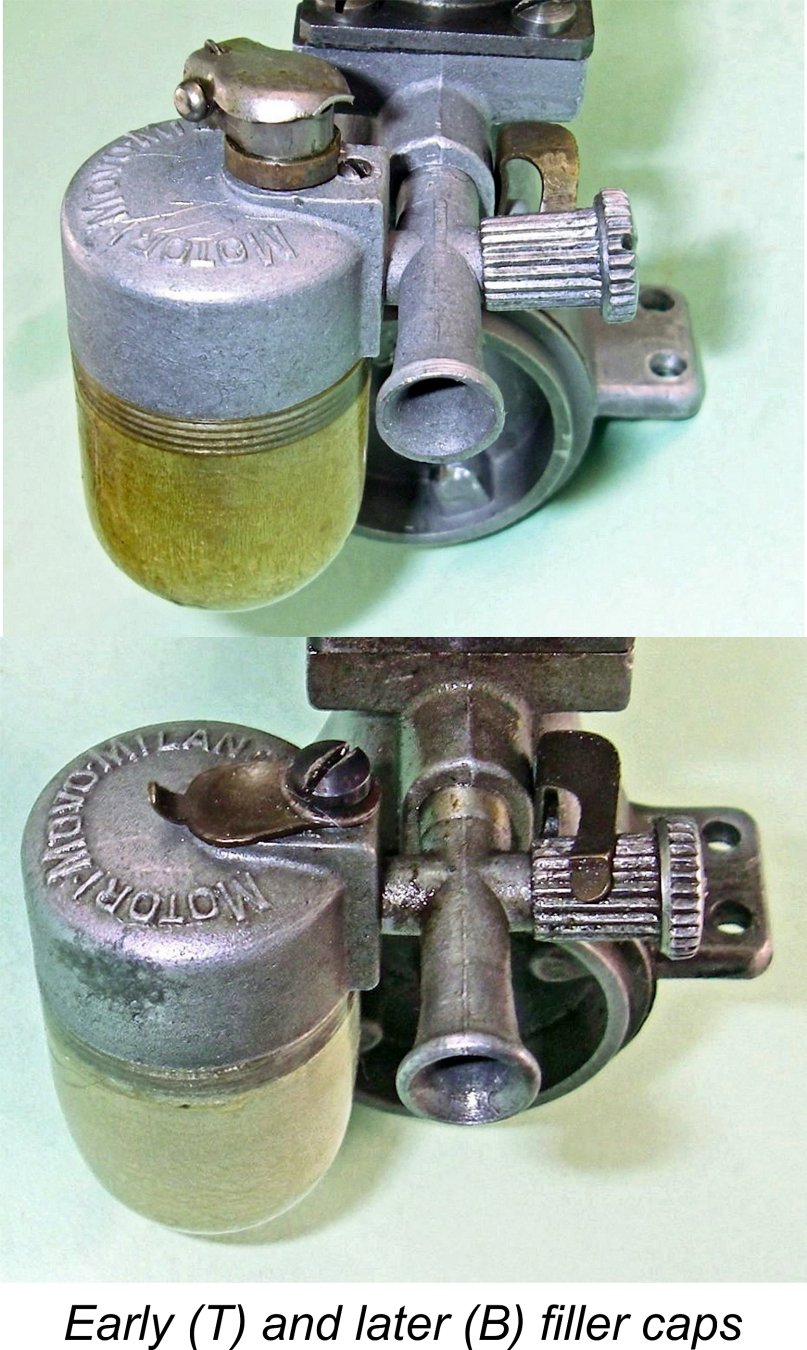

Oddly enough, neither version included any provisions for a cut-out. However, the company listed an accessory called a “Movostop” which seems to have been a timer of some sort. This apparently acted upon a crankcase pressure relief valve which could be mounted either on the suitably drilled and tapped backplate or at the front of the crankcase. It stopped the engine by breaking the crankcase seal, hence compromising the engine’s base pumping efficiency A small cast-in extrusion was provided on the lower front face of the crankcase beneath the main bearing housing to accommodate such a valve following drilling and tapping. The instruction manual makes specific reference to this feature. It would seem that the early examples were supplied with this extrusion already drilled and tapped, since engine number 1066 which appears in Laidlaw-Dickson’s book has a blanking screw mounted in this hole, as seen at the right. An example which is so equipped also appears in one of the drawings in the instruction manual. On later models, such as my own engine number 1256 and those having higher numbers, this location is undrilled. The functional design of the engine more or less followed the pattern established in 1941 with the Dyno and widely imitated by others. The four cleanly-cut cylinder ports were milled oval-shaped “race track” The material specification as set out in the instruction manual was of some interest. The cylinder was machined from pearlitic cast iron, while the flat-topped piston and matching contra piston were of steel – the reverse of the usual British material selection. The crankcase was a cleanly-formed gravity die-casting in aluminium alloy, with a bronze bushing for the main bearing cast in place during the foundry stage. The one-piece steel crankshaft was machined from a forging. All carburettor components were pressure die-castings. The standard of casting and workmanship throughout was very high. The most unusual component in design terms was the con-rod. This was formed out of a high-strength bronze alloy by stamping. It must be said that the proportions of this component appear to be very much on the minimal side for a 2 cc diesel. In his previously-referenced late 1946 book entitled “Model Diesels”, D. J. Laidlaw-Dickson commented Another slightly unusual feature was the absence of any knurling on the face of the steel prop driver. In some ways this is a good idea in that it allows for slippage of the prop in the event of such issues as a hydraulic lock or a hard impact with the ground. The manufacturers recognized the possibility of a slipping prop affecting starting, since it is one of the possibilities covered in the trouble-shooting section of the instruction manual. The fuel tanks of the “Normal” variants and the early examples of the “Sport” model were both fitted with spring-loaded filler caps of the Gits pattern. My own “Sport” model no. 1256 is so equipped, as was engine number 1270 illustrated in the instruction manual. However, later examples of the “Sport” model such as my engine number 2577 feature a pivoting cap of sheet brass in place of the Gits-type cap. All models utilized an externally-threaded steel needle which engaged with a surface jet in the intake venturi. The needle was embedded in a heavily-serrated die-cast alloy thimble. Needle stability was ensured through the use of a sheet brass spring which was secured by the same screw that tightened the clamp which secured the intake tube. This spring is extremely effective in use.

For normal applications (presumably in free flight service), the manufacturers recommended the use of an airscrew having a diameter of 280 - 300 mm (11- 12 inch) and a pitch of 140 – 150 mm (5.5 – 6 inch). The instruction manual claimed that the engine would turn a 280x152 (11x6) airscrew at 5,000 RPM. For control line models, a propeller of 240 mm (9.5 inch) diameter and 200 mm (8 inch) pitch was suggested. In present-day non-metric terms, this reads as if an 11x6 would be correct for free flight, with a 9x8 for control line applications.

Each original MOVO carried a very cleanly stamped serial number on the forward-facing bypass passage just below the engine’s similarly-stamped name. The earlier examples carried only the name and the serial number, as exemplified by my own engine number 1256 as well as engine number 1676 illustrated by Ron Chernich. Engine number 1270 which appeared in the factory instruction manual was also marked in this way, as was previously-illustrated engine number 1066 which appeared in Laidlaw-Dickson’s book. Later examples, including my own engine no. 2577, had “Made in Italy” stamped below the serial number in addition. This addition was presumably inspired by the engine’s success in America, of which more below in its place. The orders from America appear to have combined with demand in Europe to stimulate the production of a sizeable number of these engines by early post-WW2 European standards. Engine number 1066 appeared in Laidlaw-Dickson’s book, as noted above. I own engine nos. 1256, 2577 and 4239, while engine nos. 1676 and 3255 appeared in Ron Chernich’s previously-referenced article. Engine number 2740 appeared in the ECJ article to which reference was made earlier. I’d be extremely grateful to hear of any additional serial numbers which extend this range either up or down. It’s interesting to note that I have yet to see a three-digit serial number in many years of looking. This makes it appear highly likely, albeit presently unproven, that the sequence started at engine number 1000, a common practise at the time. Until clarification is obtained on this point, the best that I can do is to state that we currently have evidence for the production of at least 4,000 examples in total. Of course, the true number could be considerably greater than this. Some higher serial numbers would tell the tale ............. The MOVO D-2 in America The previously-noted early arrival of the MOVO D-2 in America following WW2 is confirmed by the existence of an article by Jim Watson which appeared in the March 1946 issue of “Model Airplane News”. In this pioneering article (which must have been written by February 1946 allowing for editorial deadlines), Watson described the operation of model diesels in some detail, also specifically mentioning four model diesels with which he was personally familiar. The MOVO D-2 was among those four engines.

The various contemporary articles by other diesel-minded American commentators such as Jim Noonan (“Air Trails”) and Jack Bayha (“Model Airplane News”) were also highly influential in promoting this development. Both Noonan and Bayha were enthusiastic diesel users who promoted the diesel cause quite vigorously. Both writers mentioned the MOVO D-2 in very positive terms. The fine qualities of the MOVO quickly awoke a desire among American model fliers to own their own examples. This led to the engine becoming the first European diesel to enter the American market in quantity – indeed, it was almost certainly the first European engine of any type to penetrate that market. Major distribution houses such as America’s Hobby Center (AHC) and Polk’s Hobbies (both of New York) placed large orders, resulting in thousands of examples entering service in American from mid 1946 through into 1949. It’s noteworthy that the majority of examples which show up on eBay today seem to come from American sources.

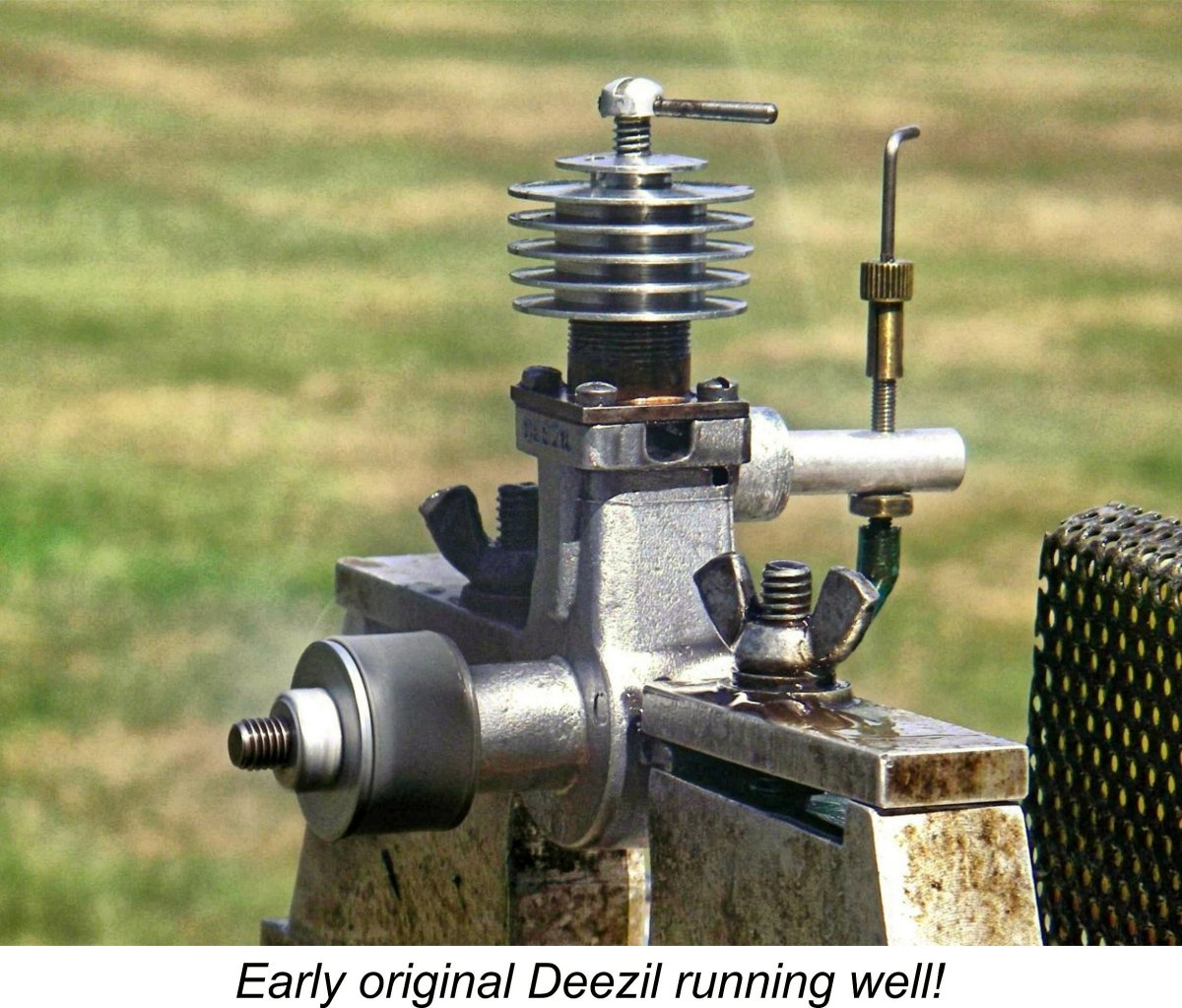

When it was first introduced to the US market in 1946, the D-2 was priced at a rather healthy $24.95 – a serious chunk of change at that time, especially for a 2 cc diesel! By the time of the engine’s final withdrawal from the American scene in mid 1949 its price had been dropped to a somewhat more rational $14.95. However, this was not enough to keep the engine’s head above water in the rising glow-plug tide, hence its mid 1949 disappearance from the US market. Overall, it’s true to say that the early 1946 appearance of the MOVO D-2 in the USA was highly influential in initiating a glorious two-year period during which the model diesel secured a place of some prominence in the American model flying and engine manufacturing scenes. In many ways it’s a pity that Ray Arden’s introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug in late 1947 derailed America’s diesel development programs so comprehensively – we might have seen some outstanding products if the trend had continued. Be that as it may, the role of the D-2 in promoting that period of intensive diesel development and use in America cannot be overstated. The Deezil Connection I already mentioned the examples of the Drone and Mite diesels, both of which evidently drew their design inspirations from European models which found their way to America after the conclusion of WW2. It’s far less well-known that the MOVO D-2 may also have been the design inspiration for a somewhat less praiseworthy American product. The design in question is perhaps one which Signor Clerici and his colleagues would rather not have associated with their excellent product – we’re talking about the infamous Deezil here!

This of course is a completely unsubstantiated possibility, since we actually have no authoritative knowledge of the way in which the design of the Deezil came about, or even who was responsible. However, the company which introduced the Deezil to the mass US market, Gotham Hobby of New York, had previously been involved in the marketing of the MOVO D-2 in America. So the MOVO was certainly available to serve as a design influence. What an insult, some might think – to have the excellent MOVO cited as the possible design influence for arguably the world’s worst-ever model diesel!! Well, even if that were true (and there's presently no hard evidence of which I'm aware), it might not be as bad as it appears. My extensive research into the Deezil saga has amply documented the fact that that the Dumpster Deezils that we all know and hate were the result of a basically sound design being trashed down So the actual American design which may have been inspired by the MOVO was a pretty good engine until it was trashed down after the fact through a change in manufacturing and marketing philosophies. Can't hold that against the MOVO! I noted earlier that prior to embarking upon its course of consigning the poor old Deezil to undeserved infamy, Gotham Hobby had actually been involved in the marketing of the MOVO D-2 in America. Beginning in April 1947, they initiated a “Diesel Block” in their advertising. The MOVO D-2 was included in that original placement along with the American-made Drone and Mite diesels. This placement continued unchanged apart from the addition of a dieselized Arden until December 1947, when the “Deezil A” was added. Gotham ceased listing the MOVO soon thereafter, throwing all of their weight behind the Deezil. One can’t help but feel that they got it the wrong way round ………. Meanwhile, Back in Italy ……..

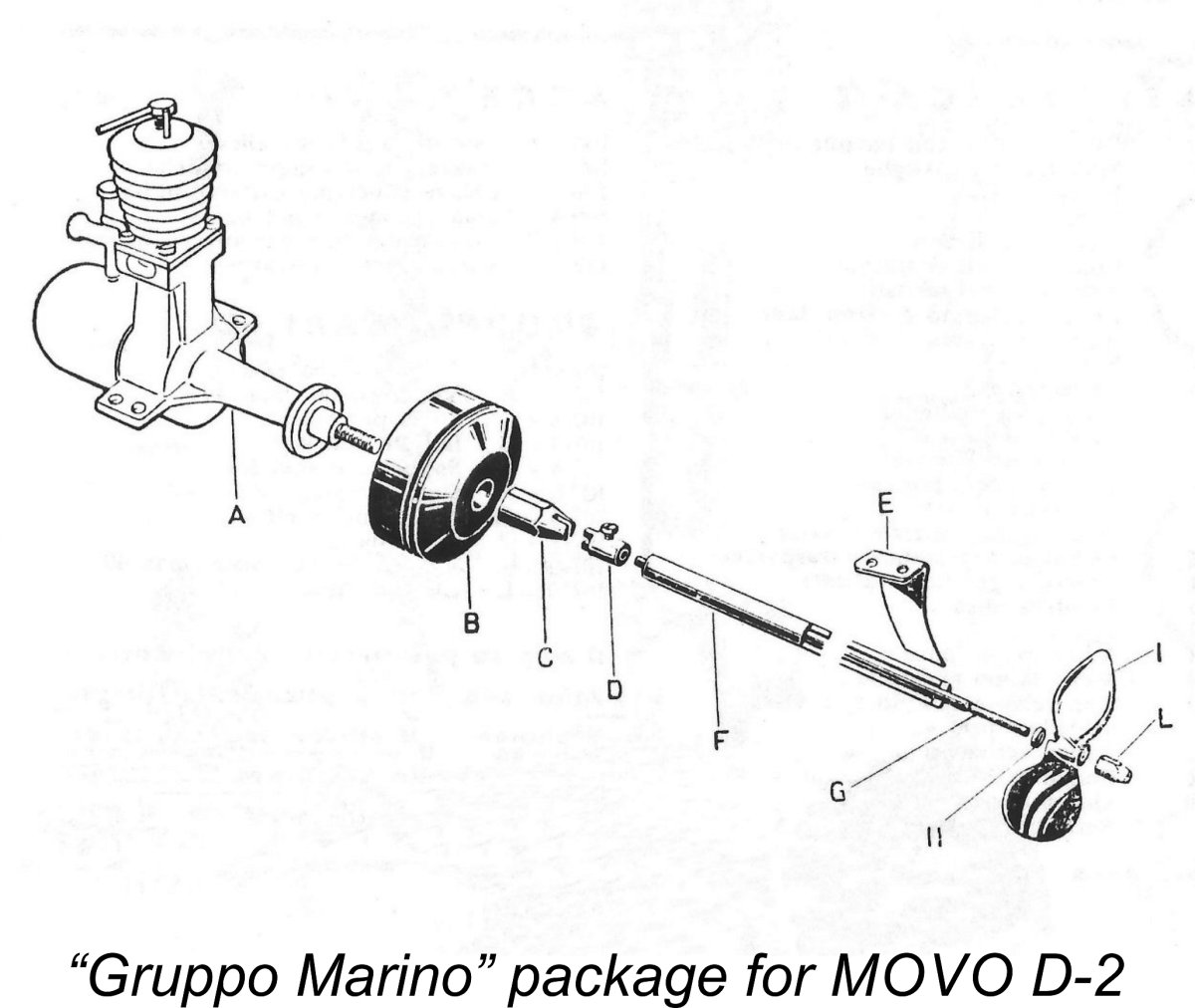

The firm also made a 9.97 cc spark ignition engine called the MOVO D.P. 23 for reasons which are hard to fathom given its displacement! This was a complete contrast in design styles to the MOVO D-2, being built very much in thesame style as the larger American spark ignition engines of the early post-WW2 era. Aopologies for the poor quality of the attached image, but it's the only one that I've so far been able to find.

The company also advertised a variable-pitch propeller which looks a lot like the similar unit produced in England by International Model Aircraft (IMA) under their FROG label. It is to be hoped that this was somewhat more successful than the FROG version, which was rather problematic in service. Finally, the company reportedly made a MOVO D-1 diesel of only 1 cc displacement. So far, I have been unable to independently confirm the existence of this model – indeed, I was unable to find as much as a photograph to use for this article. If this model did in fact exist, it seems to have been made in extremely small numbers. It’s presently unclear when MOVO production finally ceased. The company was evidently still trading as of 1949, when the previously-mentioned 10 cc diesel models were illustrated in the May 1949 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine, but I have no information regarding how much longer the company continued to operate after the orders from the USA dried up in mid 1949. Perhaps some kind reader can enlighten me?!? The MOVO D-2 Replicas For over three decades after the end of MOVO D-2 production, the dies remained in the hands of the Aguzzoli Company of Milan, which had evidently supplied the castings for the engines. In 1984 it was learned that these dies were finally about to be scrapped. An enterprising individual named N. Sauro Zanchi stepped in at this point and acquired the dies.

These superb replicas would be almost indistinguishable from the original engines except for the fact that they have a very different serial numbering system. The actual serial number is stamped on one of the mounting lugs, while the serial number location on the bypass passage at the front bears only the year of manufacture. Now, having shared what little I’ve been able to learn about the MOVO range, it’s time at last to join the oily hand brigade and get down to the main business at hand - some serious testing! The MOVO D-2 on Test

I decided to pay tribute to Peter's fine work by using engine no. 2577 as my test example of the MOVO. Although clearly quite well used, it remains in completely original configuration, also appearing to be in excellent mechanical condition. It should thus be quite representative of the design. That said, there’s always value in testing different examples of the same engine. Performance differences are to be expected between different examples of the same mass-produced powerplant – the Mills diesels from England, for example, were notorious for this, as were the later die-cast Elfin engines. The extent of any such differences speaks eloquently to the consistency of manufacture, hence its relevance in a testing context. Bearing this in mind, I intend to carry out spot checks of my other two examples when time permits. Any significant performance differentials will be duly reported in a future update of this article. For now, time constraints dictate that the test of engine number 2577 will have to suffice.

The chosen reference example of the E.D., engine number M670/7 dating from November 1947, was completely original as tested apart from having lost its stacks, probably due to the usual Mk. II issue of the soft solder melting during some bench test running! Looking at the MOVO and the E.D. side by side undescores one of the most attractive aspects of early Italian model engines - their curvaceous lines! The Italian designers had it all over the Brits when it came to endowing their engines with seductive outlines, and the MOVO is by no means their best example! Check out a Helium B.6 or an Atomatic 5 sometime ........... When running any example of the MOVO D-2, it’s always wise to keep that rather flimsy-looking con-rod in mind. I had run both engine numbers 1256 and 4239 previously (a long time ago) and had encountered no trouble, noting only that neither engine appeared to develop much power. However, it’s prudent to exercise considerable restraint with the comp screw, avoiding any suggestion of a hydraulic lock. In addition, the use of an electric starter would almost certainly be a death warrant for one of these units. You have been warned!

Engine number 2577 had clearly seen some use in the past, hence being well run in. Accordingly, I saw no need to go through a break-in procedure prior to commencing the actual testing. A few shake-down runs were all that was required. The engine was soon happily ensconced in the test stand and fitted with an 11x4 Zinger wood prop. I used a fuel containing some 30% castor oil and a small dose of ignition improver. With this fuel in the tank, I commenced operations. I soon learned that the main thing to avoid with this engine was getting it flooded. Like all long-stroke sideport diesels, the MOVO was found to have a well-developed tendency to pool excess fuel in the crankcase. A firing burst would throw this up into the cylinder en masse, immediately either putting the engine into oscillation mode or flooding it to a complete stop. Once flooded, the engine took a lot of clearing - best avoided.

Once running, the MOVO performed very well. The needle setting was found to be quite critical for best performance - a single click made a noticeable difference. However, once established, the setting was held firmly. By contrast, the compression setting was far from critical, hence being very easy to establish. The comp screw held its settings perfectly at all speeds tested, while the contra piston displayed no tendency to stick in the bore when hot. The seemingly flimsy conrod held up just fine - in fact, no mechanical problems of any kind were experienced. Running was very smooth indeed, with vibration levels being no more than might be reasonably expected for a long-stroke engine of this type. Now for the bad news - I have to say that the test unit signally failed to confirm the manufacturer's performance claims! The following data were obtained on test.

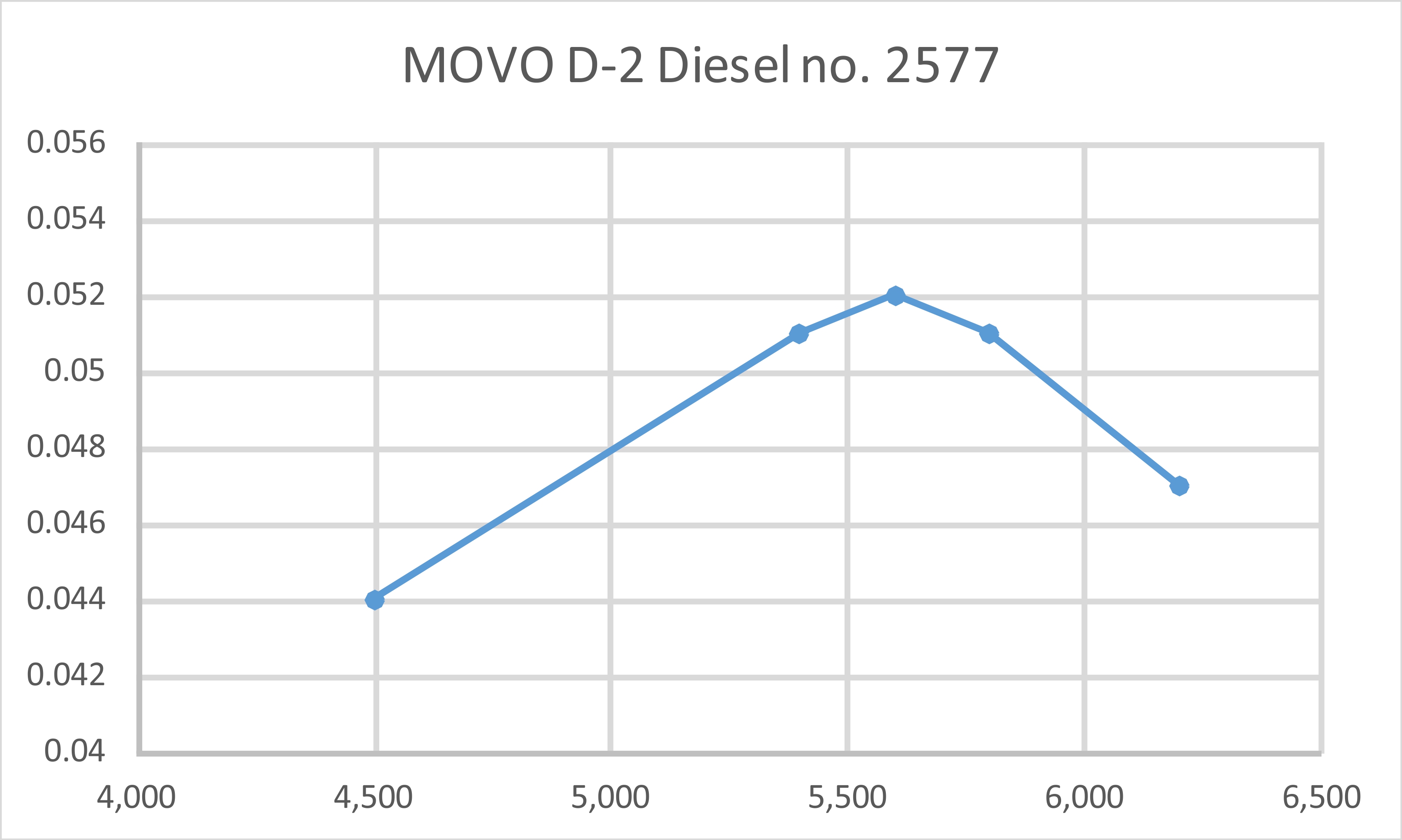

The 9x7 WB wood prop is a cut-down Zinger 11x7 prop created and calibrated to fill a gap in my wood prop test series. As can be seen, the test engine appeared to develop around 0.052 BHP @ 5,600 RPM - about what I'd expect from a design of this type dating from 1944. This is well down on the measured performance of the previously-cited reference engine, E.D. Mk. II no. M670/7, which was found on test to develop around 0.085 BHP @ 6,500 rpm. However, we have to remember once again that the MOVO D-2 pre-dates the E.D. by over 2 years. I'm completely unsurprised by the MOVO's failure to achieve anything even close to its manufacturer's performance claims. It wasn't until late 1947, when the E.D. Comp Special appeared, that 2 cc sideport diesels began to develop the kind of performance claimed by the MOVO designer. Moreover, the Comp Special had to rev considerably faster than 5,000 RPM to get to that kind of output. As it is, the MOVO would doubtless have been seen as a perfectly satisfactory powerplant in the mid 1940's. With something like a 10x5 prop fitted, it would have flown a free flight sport model very well. It's also extremely well made, suggesting that it would last for a very long time provided one avoided damaging that seemingly flimsy conrod. Its low power would have been more of a limitation for control-line applications. Conclusion

Good examples of the D-2 continue to turn up fairly regularly, many of them in the USA where the engine clearly achieved considerable sales success back in the day. Many of those engines remain in excellent condition today because the diesel era (if we may call it that) in the USA didn't last long, being effectively ended by Ray Arden's late 1947 introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug. At that point, most of the MOVO engines already in America were put away, long before their useful life had ended. They are still around today to allow us the opportunity to appreciate their qualities. So keep your eyes open, and you may find your own opportunity to become acquainted with one of the real classic pioneering diesels! It's an experience that any model diesel enthusiast will savour! ______________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published February 2020 |

||

| |

In this article, I’ll present a review and test of an Italian engine which has a far greater historical significance than many people realize. This is the MOVO D-2 diesel from Milan in Northern Italy. It was notable in being among the first European engines to be exported in quantity to other countries, particularly the USA. It appears to have done much to usher in the brief and often overlooked two-year period during which model diesel engines achieved considerable prominence in America before being submerged by the rising glow-plug tide.

In this article, I’ll present a review and test of an Italian engine which has a far greater historical significance than many people realize. This is the MOVO D-2 diesel from Milan in Northern Italy. It was notable in being among the first European engines to be exported in quantity to other countries, particularly the USA. It appears to have done much to usher in the brief and often overlooked two-year period during which model diesel engines achieved considerable prominence in America before being submerged by the rising glow-plug tide.  The concept of the model compression ignition (aka somewhat incorrectly “diesel”) engine goes back way further than many of today’s model engine enthusiasts seem to realize. In the past, it was often claimed that the 2 cc Swiss Dyno 1 model of 1941 was the “first” commercial model diesel. While that may be true in terms of widespread acceptance and design influence, the concept actually dates back to December 17

The concept of the model compression ignition (aka somewhat incorrectly “diesel”) engine goes back way further than many of today’s model engine enthusiasts seem to realize. In the past, it was often claimed that the 2 cc Swiss Dyno 1 model of 1941 was the “first” commercial model diesel. While that may be true in terms of widespread acceptance and design influence, the concept actually dates back to December 17 earliest spin-off products, being developed in 1940 and making its market debut in 1941. It was a considerable step forward from the Etha designs, being both smaller and lighter as well as having a higher specific power output. As time went on, the Dyno became one of the most influential and widely-imitated early model diesel designs of them all.

earliest spin-off products, being developed in 1940 and making its market debut in 1941. It was a considerable step forward from the Etha designs, being both smaller and lighter as well as having a higher specific power output. As time went on, the Dyno became one of the most influential and widely-imitated early model diesel designs of them all. at the time he was heavily involved with war-related work at the Aeronautical Academy in Forli, he was sufficiently intrigued by the Dyno to immediately begin exploring the compression ignition concept for himself by developing the design of his first diesel, the OSAM G.13 “Supertigre” model of 5.28 cc displacement. A few examples were produced in 1943, but Garofali's return to Bologna in September 1943 following Italy’s formal surrender to the Allies changed his employment situation to the point where further model engine building work had to be deferred until late 1945.

at the time he was heavily involved with war-related work at the Aeronautical Academy in Forli, he was sufficiently intrigued by the Dyno to immediately begin exploring the compression ignition concept for himself by developing the design of his first diesel, the OSAM G.13 “Supertigre” model of 5.28 cc displacement. A few examples were produced in 1943, but Garofali's return to Bologna in September 1943 following Italy’s formal surrender to the Allies changed his employment situation to the point where further model engine building work had to be deferred until late 1945. However, much of Italy had ceased to be directly involved in the fighting as of the liberation of Rome on June 4

However, much of Italy had ceased to be directly involved in the fighting as of the liberation of Rome on June 4 The Supertigre range had its commercial origins in late 1945 with the appearance of a few more examples of the G.13 diesel of 5.28 cc displacement, which had been designed by Jaures Garofali during the war, as mentioned earlier. Prior to the outbreak of war, Garofali had been involved with several others in a venture called the Officina Sperimentale Apparecchi Motori (Aircraft and Engines Experimental Workshop), known as OSAM for short. Throughout his changes of employment during WW2, Garofali retained this connection. Hence, the G.13 was referred to as the OSAM G.13 at this stage, although the Supertigre name was already associated with it. About 24 examples of this model were produced.

The Supertigre range had its commercial origins in late 1945 with the appearance of a few more examples of the G.13 diesel of 5.28 cc displacement, which had been designed by Jaures Garofali during the war, as mentioned earlier. Prior to the outbreak of war, Garofali had been involved with several others in a venture called the Officina Sperimentale Apparecchi Motori (Aircraft and Engines Experimental Workshop), known as OSAM for short. Throughout his changes of employment during WW2, Garofali retained this connection. Hence, the G.13 was referred to as the OSAM G.13 at this stage, although the Supertigre name was already associated with it. About 24 examples of this model were produced. An excellent source of information from classic Italian-language modelling magazines may be found on the very informative website entitled “

An excellent source of information from classic Italian-language modelling magazines may be found on the very informative website entitled “ I mentioned more or less at the outset that the Swiss Dyno 2 cc diesel from 1941 became one of the most influential and widely-imitated model diesels of the pioneering era. The MOVO D-2 provides a good example – basically it is Yet Another Copy Of The Dyno, albeit with a number of refinements which set it apart.

I mentioned more or less at the outset that the Swiss Dyno 2 cc diesel from 1941 became one of the most influential and widely-imitated model diesels of the pioneering era. The MOVO D-2 provides a good example – basically it is Yet Another Copy Of The Dyno, albeit with a number of refinements which set it apart. The two variants were basically identical in functional terms – all working parts were interchangeable. The differences were confined to the fuel supply arrangements. The “Normal” model had a backplate-mounted aluminium fuel tank of quite substantial capacity. On this version, the vertically oriented needle valve and spray bar extended directly downwards into the tank from above. On the “Sport” model, the venturi was rotated 90° and equipped with a side-mounted diecast top for a far smaller screw-on tank of a translucent plastic material, which the manufacturer referred to as “plexiglass”.

The two variants were basically identical in functional terms – all working parts were interchangeable. The differences were confined to the fuel supply arrangements. The “Normal” model had a backplate-mounted aluminium fuel tank of quite substantial capacity. On this version, the vertically oriented needle valve and spray bar extended directly downwards into the tank from above. On the “Sport” model, the venturi was rotated 90° and equipped with a side-mounted diecast top for a far smaller screw-on tank of a translucent plastic material, which the manufacturer referred to as “plexiglass”. As any diesel enthusiast knows, the operation of a model diesel in the inverted orientation carries with it a greatly enhance risk of a hydraulic lock developing during starting. The manufacturers were very well aware of this issue, making a point of explaining this problem and its potential consequences in the instruction manual. They actually went so far as to recommend that the engine be used in an inverted position only by modellers who were extremely familiar with the operating characteristics of model diesels. Very wise advice ..............

As any diesel enthusiast knows, the operation of a model diesel in the inverted orientation carries with it a greatly enhance risk of a hydraulic lock developing during starting. The manufacturers were very well aware of this issue, making a point of explaining this problem and its potential consequences in the instruction manual. They actually went so far as to recommend that the engine be used in an inverted position only by modellers who were extremely familiar with the operating characteristics of model diesels. Very wise advice .............. apertures. There was a single induction port at the rear, with a single transfer port at the front which overlapped the exhaust almost completely. This was fed by a bypass passage formed in the upper crankcase casting at the front. At the sides, between the induction and transfer ports, there were a pair of exhaust openings which discharged through channels formed in opposite sides of the upper crankcase casting.

apertures. There was a single induction port at the rear, with a single transfer port at the front which overlapped the exhaust almost completely. This was fed by a bypass passage formed in the upper crankcase casting at the front. At the sides, between the induction and transfer ports, there were a pair of exhaust openings which discharged through channels formed in opposite sides of the upper crankcase casting. upon this very point, stating that the stamped alloy con-rod used in the D-2 appeared to be “perhaps a trifle light for hard use……………..In spite of this, however, our test engine has stood up to a remarkable degree of maltreatment, so must in fact be quite sound.”

upon this very point, stating that the stamped alloy con-rod used in the D-2 appeared to be “perhaps a trifle light for hard use……………..In spite of this, however, our test engine has stood up to a remarkable degree of maltreatment, so must in fact be quite sound.” The engines were supplied with a very detailed and lavishly illustrated 24 page instruction manual presented in Italian. The operating instructions were well considered and clearly expressed. I do not know if an English version was printed for the American market, but it would have been logical for the company to do this given the fact that the MOVO D-2 was a “first diesel” for many American modellers.

The engines were supplied with a very detailed and lavishly illustrated 24 page instruction manual presented in Italian. The operating instructions were well considered and clearly expressed. I do not know if an English version was printed for the American market, but it would have been logical for the company to do this given the fact that the MOVO D-2 was a “first diesel” for many American modellers. The recommended fuel mixture is interesting. This was a time when there was still widespread disagreement regarding the best fuel mixture for model diesels. The range of mixtures suggested by various manufacturers was considerable. The manufacturers of the MOVO D-2 recommended a mixture consisting of 38% ether, 38% white gas or naptha and 24% lubricating oil. The use of a high quality mineral oil such as Castrol XXL was specifically recommended.

The recommended fuel mixture is interesting. This was a time when there was still widespread disagreement regarding the best fuel mixture for model diesels. The range of mixtures suggested by various manufacturers was considerable. The manufacturers of the MOVO D-2 recommended a mixture consisting of 38% ether, 38% white gas or naptha and 24% lubricating oil. The use of a high quality mineral oil such as Castrol XXL was specifically recommended. The generally excellent and trouble-free performance of the MOVO by the standards of the day doubtless did much to encourage American modellers to take a serious interest in model diesels. The engine seems to have served as a very worthy ambassador for the model diesel cause. At the time when the MOVO first appeared in the USA there were no commercial American diesels, but the speedy acceptance of the MOVO along with that of the larger Micron 5 cc model quickly encouraged an amazing number of US manufacturers to become involved in the development of diesels. That story has been recounted in other articles on this website which deal with

The generally excellent and trouble-free performance of the MOVO by the standards of the day doubtless did much to encourage American modellers to take a serious interest in model diesels. The engine seems to have served as a very worthy ambassador for the model diesel cause. At the time when the MOVO first appeared in the USA there were no commercial American diesels, but the speedy acceptance of the MOVO along with that of the larger Micron 5 cc model quickly encouraged an amazing number of US manufacturers to become involved in the development of diesels. That story has been recounted in other articles on this website which deal with  In researching his contribution to the previously-cited article in ECJ, the earliest US advertisement for the MOVO D-2 that Tim Dannels was able to find was an October 1946 placement by Polk’s Hobbies which showed an example of the “Sport” version of the engine. Thereafter, the D-2 appeared on a regular basis in advertisements placed both by Polk’s and AHC, not finally disappearing from the ads until mid 1949.

In researching his contribution to the previously-cited article in ECJ, the earliest US advertisement for the MOVO D-2 that Tim Dannels was able to find was an October 1946 placement by Polk’s Hobbies which showed an example of the “Sport” version of the engine. Thereafter, the D-2 appeared on a regular basis in advertisements placed both by Polk’s and AHC, not finally disappearing from the ads until mid 1949. It has been credibly suggested that the original design of the Deezil was influenced by, or at least inspired by, that of the MOVO D-2. Placing a Deezil and a MOVO side by side does indeed create an undeniable impression that the general design layout of the Deezil could have been substantially influenced by that of the MOVO.

It has been credibly suggested that the original design of the Deezil was influenced by, or at least inspired by, that of the MOVO D-2. Placing a Deezil and a MOVO side by side does indeed create an undeniable impression that the general design layout of the Deezil could have been substantially influenced by that of the MOVO.  to an absurdly low price by Gotham Hobby after they took over the design from its unknown originators, with absolutely no regard for quality. There’s irrefutable evidence that the original Deezils were perfectly acceptable engines – my illustrated all-original early example is a well-made motor which runs very nicely indeed with no requirement for any owner intervention.

to an absurdly low price by Gotham Hobby after they took over the design from its unknown originators, with absolutely no regard for quality. There’s irrefutable evidence that the original Deezils were perfectly acceptable engines – my illustrated all-original early example is a well-made motor which runs very nicely indeed with no requirement for any owner intervention.  Of course, while all this was going on in America the Italian home market was by no means ignored. Advertisements were placed in Italian modelling magazines, resulting in the MOVO D-2 achieving considerable popularity in Italy itself. The engine seems to have been quite successful in competition – the previously-mentioned 1946 Italian article from “L’Ala” records the fact that models powered by the D-2 secured 1

Of course, while all this was going on in America the Italian home market was by no means ignored. Advertisements were placed in Italian modelling magazines, resulting in the MOVO D-2 achieving considerable popularity in Italy itself. The engine seems to have been quite successful in competition – the previously-mentioned 1946 Italian article from “L’Ala” records the fact that models powered by the D-2 secured 1 The MOVO D-2 was not the only product of Signor Clerici’s company. A complete range of accessories was produced for the engine, including the previously-mentioned automatic cut-out system, a flywheel, a prop shaft extender (presumably intended for scale models), an extractor tool for freeing the prop driver from its tapered mounting on the shaft, a set of tools for tightening the spinner and removing the backplate and a radial mount flange which could evidently replace the standard backplate. All of these were listed in the instruction manual.

The MOVO D-2 was not the only product of Signor Clerici’s company. A complete range of accessories was produced for the engine, including the previously-mentioned automatic cut-out system, a flywheel, a prop shaft extender (presumably intended for scale models), an extractor tool for freeing the prop driver from its tapered mounting on the shaft, a set of tools for tightening the spinner and removing the backplate and a radial mount flange which could evidently replace the standard backplate. All of these were listed in the instruction manual.

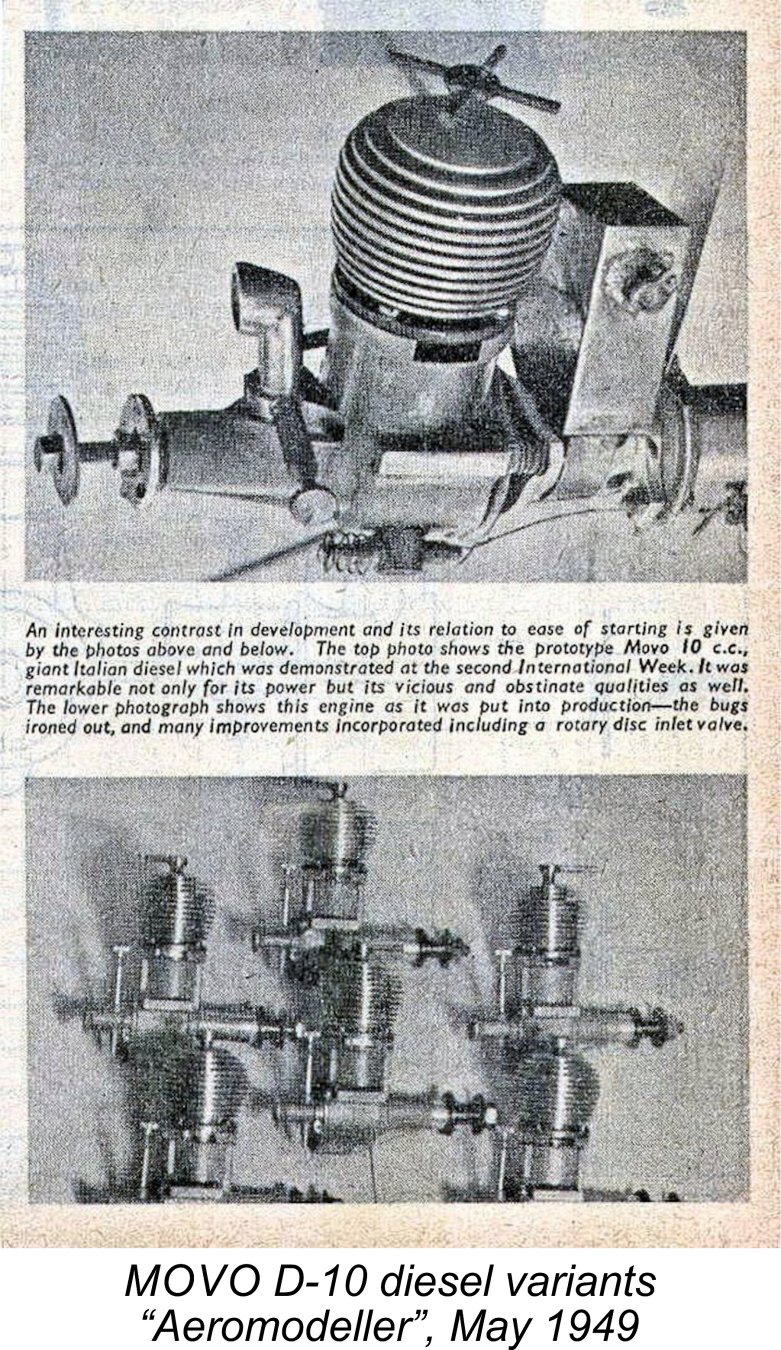

There was also a big D-10 diesel of 10 cc displacement. This was in no sense a dieselized version of the D.P. 23 sparker, as one might logically expect - rather, it was a completely distinct design from the ground up. It was produced in two successive forms – a crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) prototype which was apparently somewhat less than successful and a more refined disc rear rotary valve (RRV) version which was put into series production. Few of these appear to have made it out of Italy. This engine made its first recorded appearance at the 1947 International Week at Eaton Bray in England in the hands of Piero Gnesi.

There was also a big D-10 diesel of 10 cc displacement. This was in no sense a dieselized version of the D.P. 23 sparker, as one might logically expect - rather, it was a completely distinct design from the ground up. It was produced in two successive forms – a crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) prototype which was apparently somewhat less than successful and a more refined disc rear rotary valve (RRV) version which was put into series production. Few of these appear to have made it out of Italy. This engine made its first recorded appearance at the 1947 International Week at Eaton Bray in England in the hands of Piero Gnesi.

However, saving the dies was only part of the plan. Zanchi formed a Milan-based company called Fabrica Italiana Motori Movo for the express purpose of producing a series of replicas of the engine. Beginning in 1985, these replicas were produced using the original dies, albeit modified to be compatible with modern die-casting equipment. The components were precisely dimensioned in accordance with the originals, to the point that parts from the replicas would fit the original engines and vice versa. Replicas of both the “Normal” and “Sport” versions of the engine were offered. A test of the replica “Sport” variant by Stu Richmond appeared in the October 1991 issue of “Model Builder” magazine.

However, saving the dies was only part of the plan. Zanchi formed a Milan-based company called Fabrica Italiana Motori Movo for the express purpose of producing a series of replicas of the engine. Beginning in 1985, these replicas were produced using the original dies, albeit modified to be compatible with modern die-casting equipment. The components were precisely dimensioned in accordance with the originals, to the point that parts from the replicas would fit the original engines and vice versa. Replicas of both the “Normal” and “Sport” versions of the engine were offered. A test of the replica “Sport” variant by Stu Richmond appeared in the October 1991 issue of “Model Builder” magazine. I had direct access to three original examples of the MOVO D-2 during the preparation of this article. I’ve had two of then – nos. 1256 and 4239 – for many years now. They were both obtained from separate North American sources, which is scarcely surprising given the number of these engines which were evidently sold in the USA during the period 1946 – 1949. The third example, no. 2577, arrived far more recently, once more from a North American source. It had a graunched cooling jacket, for which an exact duplicate was very kindly made to a superb standard by my good friend Peter Valicek of the Netherlands. I’m extremely grateful to Peter for his kindness.

I had direct access to three original examples of the MOVO D-2 during the preparation of this article. I’ve had two of then – nos. 1256 and 4239 – for many years now. They were both obtained from separate North American sources, which is scarcely surprising given the number of these engines which were evidently sold in the USA during the period 1946 – 1949. The third example, no. 2577, arrived far more recently, once more from a North American source. It had a graunched cooling jacket, for which an exact duplicate was very kindly made to a superb standard by my good friend Peter Valicek of the Netherlands. I’m extremely grateful to Peter for his kindness. As my regular readers will know, it’s my usual practise to compare the performance of any tested engine with that of a familiar contemporary design of similar displacement. This really helps to place the performance of the test engine in context. In the present instance, the best comparative data that I had available were the figures obtained from an unmodified example of the

As my regular readers will know, it’s my usual practise to compare the performance of any tested engine with that of a familiar contemporary design of similar displacement. This really helps to place the performance of the test engine in context. In the present instance, the best comparative data that I had available were the figures obtained from an unmodified example of the  The attentive reader will recall the instruction manual’s claim that the engine would turn a 280x152 (11x6) airscrew at 5,000 RPM, with a peak power output of 0.12 CV (0.118 BHP) at unspecified rpm. However, I have to admit quite frankly that I was more than a little skeptical regarding both of these claims, especially given the engine's 1944 design date. I elected to go with a somewhat more rational 11x4 wood prop for initial runs, feeling that this would represent a much fairer test of the engine's torque development capabilities.

The attentive reader will recall the instruction manual’s claim that the engine would turn a 280x152 (11x6) airscrew at 5,000 RPM, with a peak power output of 0.12 CV (0.118 BHP) at unspecified rpm. However, I have to admit quite frankly that I was more than a little skeptical regarding both of these claims, especially given the engine's 1944 design date. I elected to go with a somewhat more rational 11x4 wood prop for initial runs, feeling that this would represent a much fairer test of the engine's torque development capabilities.  The best approach was to give the engine no more than 2 choked flicks followed by a "dry" exhaust prime (administered with the ports closed). Even with this approach, the engine tended to start a little on the rich side, taking some time to clear its throat and settle down. However, it never failed to start very promptly if the flooding trap was avoided.

The best approach was to give the engine no more than 2 choked flicks followed by a "dry" exhaust prime (administered with the ports closed). Even with this approach, the engine tended to start a little on the rich side, taking some time to clear its throat and settle down. However, it never failed to start very promptly if the flooding trap was avoided.

My test session with the MOVO D-2 provided an ample explanation for the engine's success both at home and abroad. It's an extremely well-made unit which starts easily once one has mastered the appropriate technique and runs very well indeed by the standards of its time. It would certainly have given long and dependable service to any careful owner.

My test session with the MOVO D-2 provided an ample explanation for the engine's success both at home and abroad. It's an extremely well-made unit which starts easily once one has mastered the appropriate technique and runs very well indeed by the standards of its time. It would certainly have given long and dependable service to any careful owner.