|

|

Diesels with a Drawl - the Classic American Diesels

The fact that the model diesel did not require a heavy and potentially undependable airborne ignition support system gave it an obvious advantage over its spark ignition counterparts, particularly in the smaller displacements. Dependability was another factor – compression ignition is essentially weather and oil-proof, involving no ignition-related moving parts, no fouling-prone plug and timer points gaps, no batteries and no electrical connections or components. Accordingly, once a diesel has started it will keep running as long as the fuel supply holds out, because there’s basically nothing to go wrong provided the engine’s mechanical structure stays together! As a result, European designers pursued the diesel concept vigorously, with enthusiastic support from the modelling public, both during and immediately after the war years. By contrast, I can find no record of any attention having been paid in America to the application of compression ignition to model engines prior to or during WW2. In my personal view, this had much to do with the fact that American modellers in the pre-WW2 era tended to favor large models, for which the typical diesel was less well suited than many existing spark ignition units. In addition, the exchange of relevant information from Europe was greatly constrained during the war years beginning in late 1939.

At the time in question, the introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug was still over two years in the future. Consequently, the advantages of the diesel engine summarized above were seen just as positively by Americans as they were by their overseas counterparts in Europe and elsewhere. This being the case, it was inevitable that American model engine manufacturers would take an early interest in exploring the potential of this new form of ignition. The number of those that did so seems to have been one of the better-kept secrets in the field of model engine history. Great Britain is often seen as one of the most influential countries in shaping the course of early post-war diesel development, yet the number of American manufacturers who had some involvement with diesels immediately following the conclusion of WW2 rivalled and possibly exceeded the number of such firms in Britain!

Accordingly, I’ve prepared a single article summarizing all of the various commercially-motivated diesels which made their appearances in America during the first post-WW2 decade. I think that many readers will be quite surprised at the length and scope of this summary – we’re talking about a nation which had a far more significant presence in the model diesel field than many folks may realize! The format of this article will be quite straightforward. I’ll list the engines as closely as possible in the order in which they appeared, although some degree of overlap is inevitable. Each listing will be accompanied by a few descriptive paragraphs along with an image or two. There will also be a link to the relevant article in which the engines in question are discussed in detail. I’ll finish up with a discussion of the reasons why the diesel failed to “catch on” in America to the extent that it did elsewhere. The intent is to provide an overview of diesel developments in early post-war America, with opportunities for those interested to learn more. I sincerely hope that the following material achieves this objective! Thermite 34 (late 1945)

It seems that the Thermite 34 never advanced beyond the prototype stage - the illustrated example is the sole presently-known surviving example of this engine worldwide. This prototype was owned by my late friend Ted Enticknap, who was very well connected with early post-war US model engine manufacturers on the West Coast, often serving as one of their field testers. He was personally acquainted with Jim Brown, which is probably how he came to possess this engine, which I was subsequently able to acquire. The engine runs really well, developing around 0.180 BHP @ 5,900 rpm. A full review of the Thermite 34 may be found elsewhere on this website. Mite .099 (1946 – 1948)

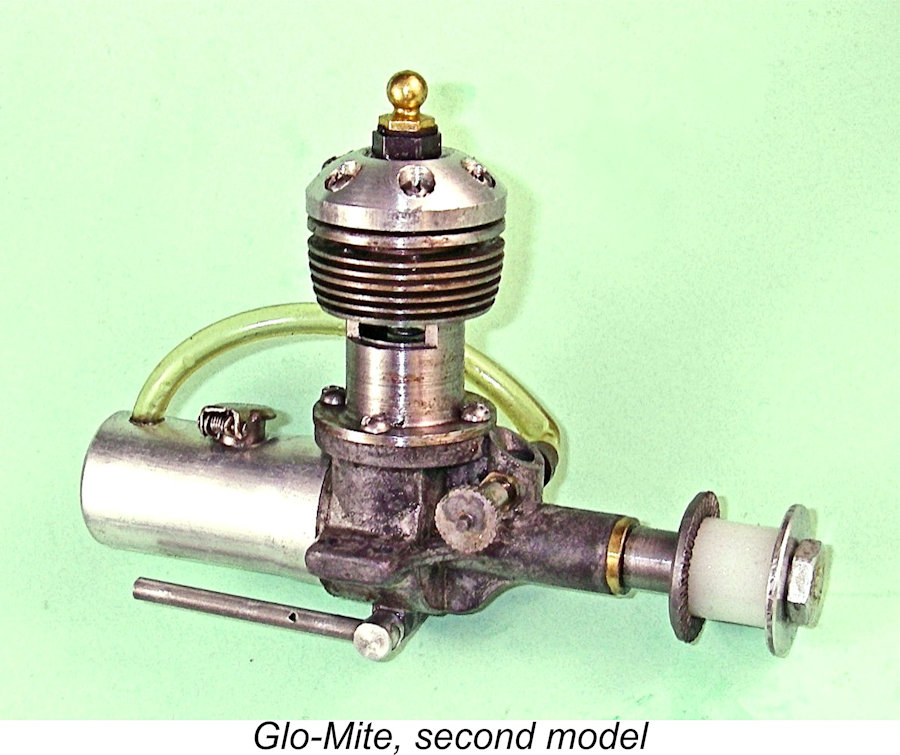

The Mite was unique among diesels in having an unusually low fixed compression ratio of only 13½ to 1. This necessitated the use of a fuel consisting of equal parts of ether and mineral oil. Manderville reached a Present-day testing confirms that the engine starts and runs quite well, although power output is somewhat marginal – around 0.08 BHP @ 8,000 RPM appears to be typical. The Mite set an early Class I control line speed record of 67.6 mph, but was soon outclassed by superior glow-plug designs from other manufacturers. A glow-plug version of the Mite called the Glo-Mite was developed in 1948 to try to stem the tide, but this effort too fell short, although the glow-plug version seems to have out-performed the diesel by a considerable margin. Around 5,000 Mite diesels were reportedly made before the glow-plug revolution buried the Mite along with other US diesels. The number of glow-plug versions is unreported. All that can be said is that examples of either version in good complete condition are relatively rare these days. A full review of the Mite diesel may be found elsewhere on this website. C.I.E. 10 (1946 – 1948)

Despite the engine's name, its true displacement was actually 0.147 cu. in. (2.41 cc). The engines were very competently designed and constructed - indeed, they could easily stand comparison with the best contemporary products of other countries involved in the manufacture of model diesels. Present-day testing has confirmed that the engine performed at a level which was well up to then-prevailing standards. I extracted a peak output of 0.107 BHP @ 7,800 RPM from one of my own examples. A full review of the C.I.E. 10 diesel may be found elsewhere on this website. Ken 61 Diesel (1946 – 1947)

There was also a fixed-compression diesel version of the same engine which was manufactured in extremely small numbers between late 1946 and early 1947. Although this model was advertised, with a few being sold, this appears to have been more of a market-testing batch than a full-scale series production effort. Following a few experiments with glow-plug designs, Ken Wade abandoned the model engine field in 1948. A detailed review of the KEN 61 engines may be found elsewhere on this website. AHC diesel (1946)

However, for reasons which remain somewhat obscure, the project stalled at that point, leaving almost all of the crankcase castings unused. Fortuitously, these castings have survived down through the years. A number of engines have subsequently been completed using surviving examples of these original castings. The illustrated example of the engine is one of these which was constructed by my late and much-missed Aussie mate Ron Chernich. The engine runs well, albeit at relatively modest levels of performance even by the standards of late 1946. A full review of the AHC diesel may be found elsewhere on this website. This includes a review of a number of variants of the engine which have been developed by Ron Chernich and his associates. Deezil (1947 – 1955)

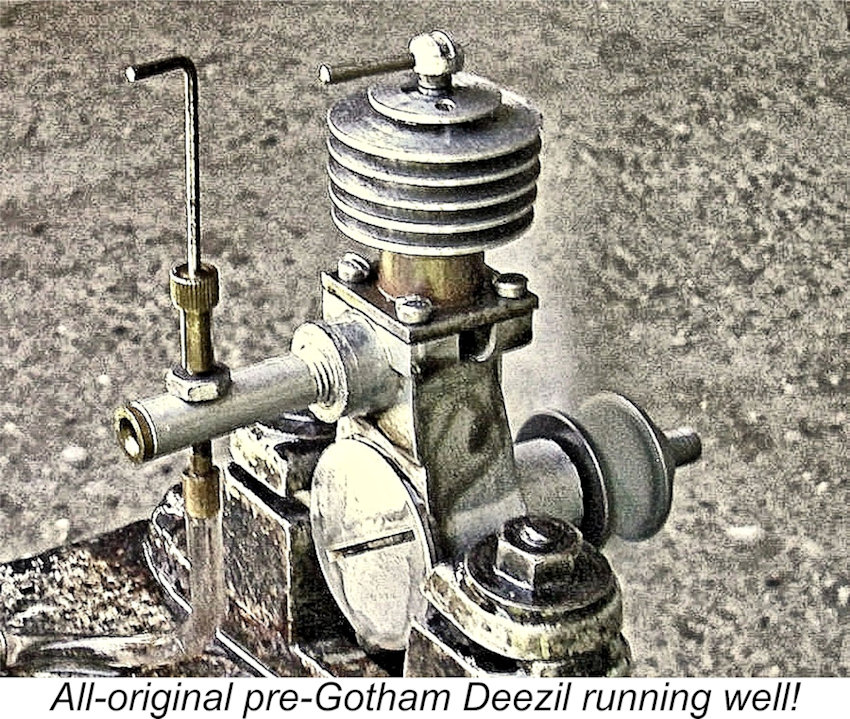

Very few of the resulting engines would run, and those that did only lasted for a few minutes at most! Despite this, the engine continued to be offered until 1955! Many thousands of these engines were sold, to the great detriment of the model diesel's reputation in the USA. See below for further discussion. That said, tests on original pre-Gotham examples as well as reconditioned Gotham units have demonstrated very clearly that there was nothing at all wrong with the basic design - it was unbelievably poor execution that let the Deezil down. A properly set-up example with the junk components replaced runs very well – my own tests imply a peak output of around 0.112 BHP @ 8,800 RPM for a refurbished Gotham model. A full review of the Deezil may be found elsewhere on this website. Arden diesel conversions (1947)

As we’ve already seen, American modellers had been engaging in a serious flirtation with compression ignition (diesel) engines prior to that game-changing event. This led several companies, including D-E Model Products of Rockville Center, New York to develop and market diesel conversion kits for the Arden engines. These kits sold in substantial numbers. The engines performed quite well in this form - tests indicate that the illustrated .099 cuin. example equipped with the D-E variable compression conversion starts easily and develops around 0.075 BHP @ 7,700 RPM, figures which are at least equivalent to the same design's performance using spark ignition with a gasoline-based fuel. However, the Arden was really too lightly built to withstand long-term operation on compression ignition. Crankshaft failures were a particular problem. As a result, the dieselized Ardens failed to make much of a mark - modellers quickly gravitated to the glow-plug versions, which ran even better and were more dependable. Even so, no review of American diesels is complete without consideration being given to the dieselized Ardens, substantial numbers of which survive today. A full review of the Arden diesel conversions may be found elsewhere on this website. Drone Mk. I and Mk. II (1947 – 1949)

The Drone diesel was manufactured in two quite distinct variants between early 1947 and mid-1949. Around 15,000 examples were produced during those years. The Drone enjoyed considerable competition success until the arrival of competing purpose-built glow-plug engines like the Fox 35 in 1948. Those lighter and more powerful models spelled the doom of the Drone, causing the termination of its manufacture in mid-1949. The first model Drone featured a plain bearing, while the second variant had a single ball-race at the rear of the crankshaft journal. Both glow heads and variable-compression diesel heads were offered as accessories. Contrary to well-established urban myths, both fixed-compression versions of the engine started easily and ran extremely well if fuelled and handled correctly. Tests on the second model imply a peak output of around 0.247 BHP @ 6,300 RPM. A full review of the Drone diesels may be found elsewhere on this website. A test of a factory glow-plug Drone conversion may also be found here. EDCO diesel (1947)

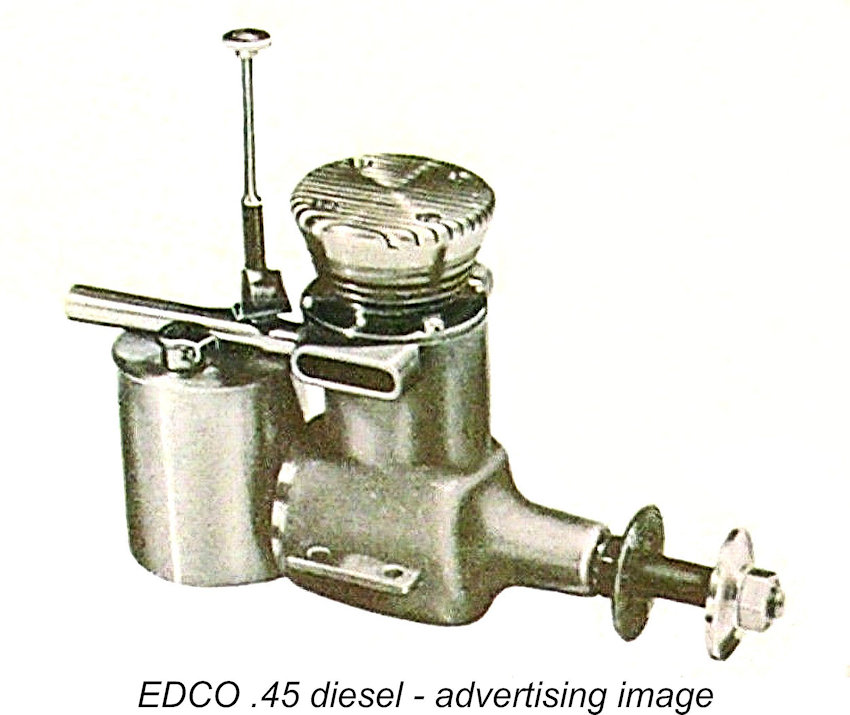

A side-port induction .45 cuin. fixed compression diesel was also planned by EDCO, but it never got past the prototype stage despite appearing in EDCO’s advertising and being mentioned in the contemporary modelling media. Ira Hassad later stated that he had nothing to do with the diesel design, although he did recall having test-run one of the handful of prototypes at Del Mar. The EDCO diesel is covered in the article on Ira Hassad which may be found elsewhere on this website. Speed Demon 30 diesel (1947 – 1948)

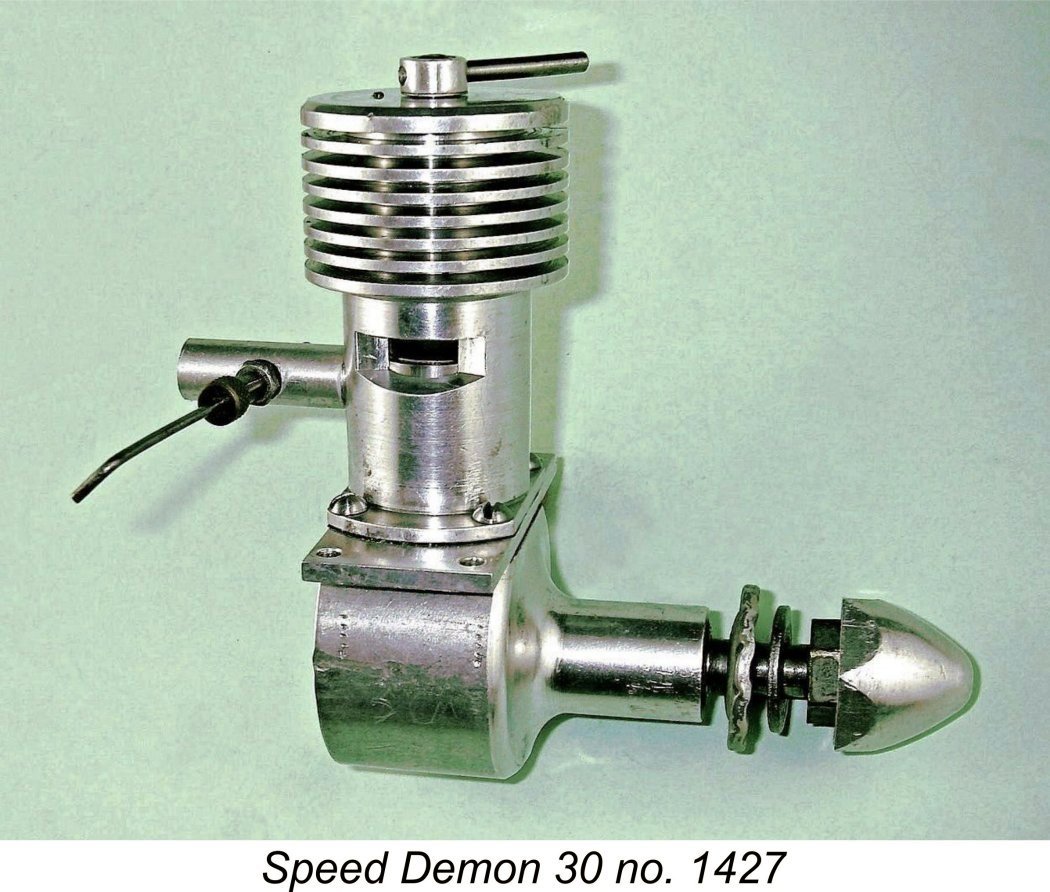

The engines were perfectly useable powerplants, starting and running very well. However, they did not generate competitive power levels, especially considering their weight and bulk. Tests on an original example imply an output of around 0.143 BHP @ 6,200 RPM - well down on the contemporary Drone. A review of the Speed Demon 30 may be found elsewhere on the MEN website. An updated edition of that article will appear on this website in due course. Air-O Diesel (1947 – 1949)

The production of the Air-O Diesel was confined to a two-year period from late 1947 through until mid-1949. Both aero and car versions were produced. The engines were very well made, also performing at a surprisingly high level. Tests on a surviving example imply an output of around 0.229 BHP @ 6,700 RPM. A review of the Air-O Diesel may be found elsewhere on this website. DeLong 29 diesel - 1947 The DeLong 29 FRV diesel was another of the surprising number of still-born American diesels which reached the This is a great pity because, as present-day tests have shown, the Delong 29 diesel was a very well-made unit having a useful performance by the standards of its day. Moreover, there’s no doubt that it had a considerable amount of development potential. Tests on a surviving original prototype example imply a peak output of around 0.134 BHP @ 5,900 RPM, but further development would doubtless have improved on this. Only three surviving original prototypes have been reported to date, while a small handful of replicas were made by the members of Motor Boys International beginning in 2000. The engine is consequently mega-rare today. A full review of the DeLong 29 diesel may be found elsewhere on this website. Micro Diesel (1947 – 1948)

The error in the conrod production was unfortunate, because further testing of a modified CS replica having a conrod of what was clearly the intended length showed a measurably-improved performance of 0.105 BHP @ 7,300 RPM. This was quite comparable with the outputs of contemporary 2 cc sideport diesels such as the E.D. Comp Special. Sadly, the engine's market launch in December 1947 coincided almost exactly with Ray Arden's introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug, which immediately put the brakes on America's brief but very productive involvement with model diesel development. The Micro Diesel was a highly regrettable casualty of this situation – production had ended by mid-1948 with the conrod length issue remaining unresolved. If the introduction of the all-conquering glow-plug had been delayed by even a year, there's little doubt that on merit alone it would have secured a high status among American modellers of the period. A full review of the Micro Diesel may be found elsewhere on this website. Vivell diesels (1947 – 1949)

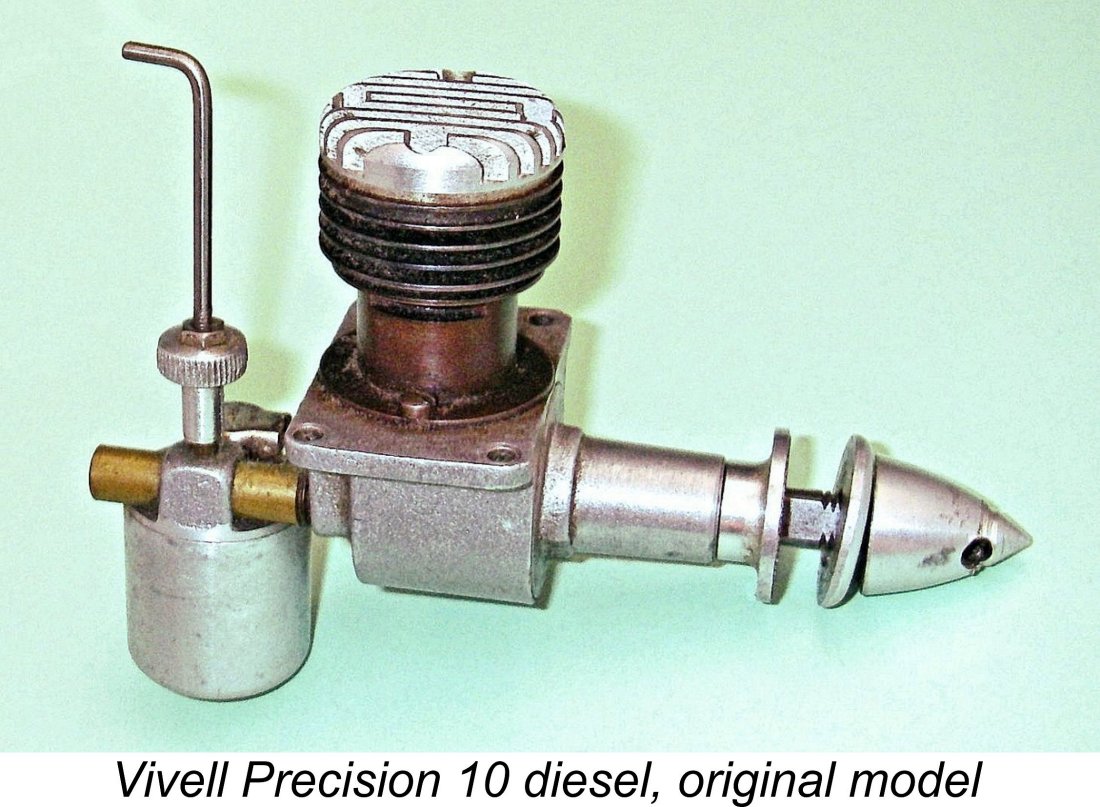

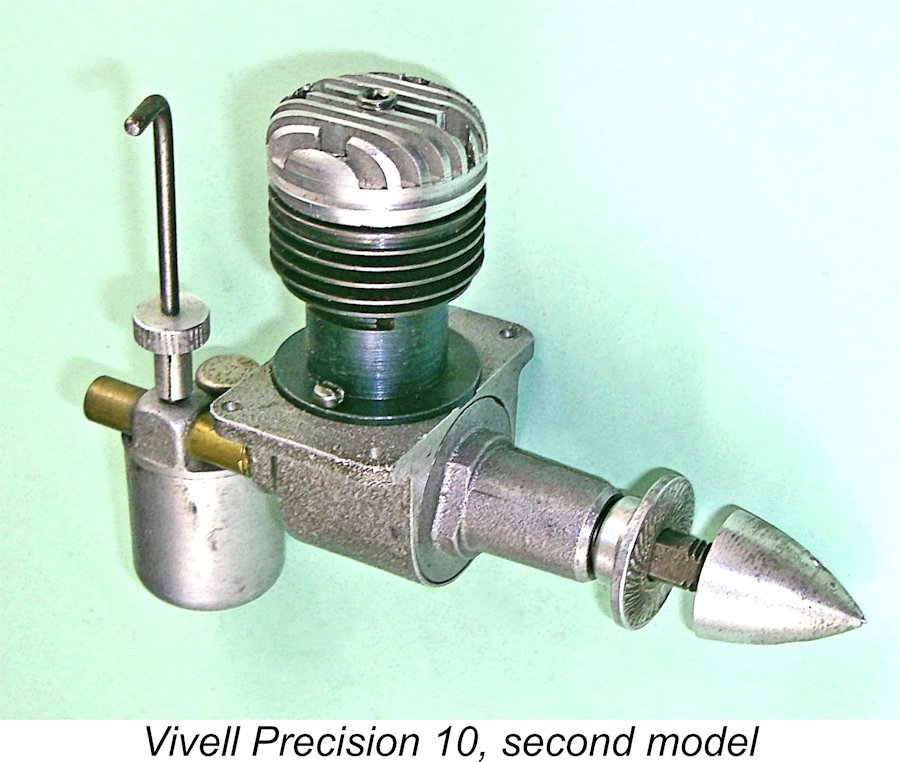

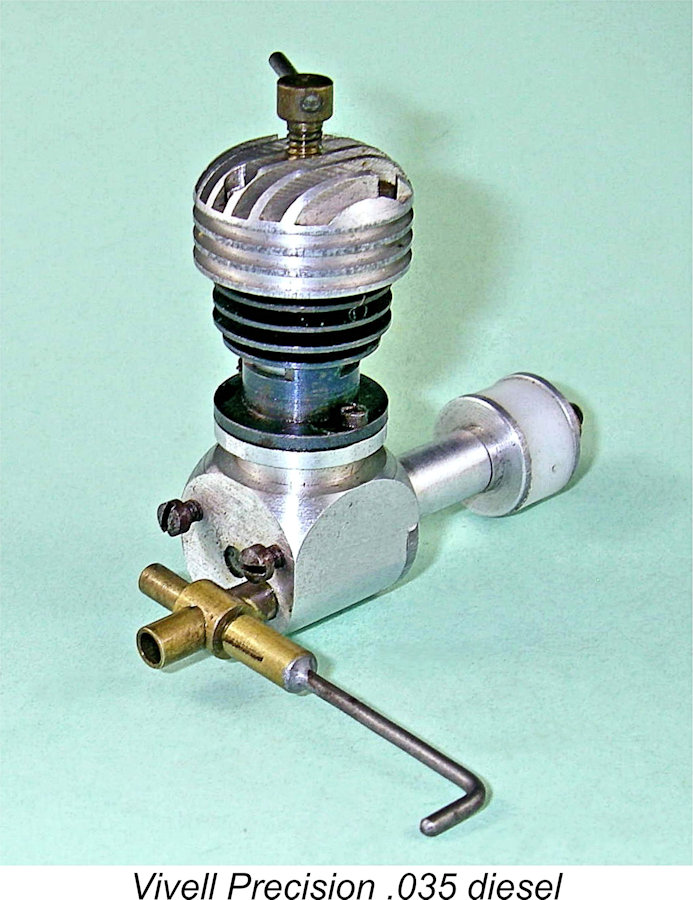

The first of these offerings was the 1947 Vivell Precision 10 diesel, a neat and compact .102 cuin. (1.67cc) fixed compression model. Like its Thermite predecessor, this very well-made engine was an extremely advanced design by the standards of its day. It used sand-castings throughout and featured disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction along with a screw-in front housing. It also used the same twin-port cylinder arrangement which had first been In 1948 a refined version of this engine appeared, featuring a head having deeper fins and incorporating a contra-piston inside the head (as opposed to inside the bore). Compression adjustment was controlled by an Allen-head screw. The variable-compression feature made this variant far more flexible as regards the range of fuels and props which could be used. However, the Allen-head compression adjustment Even so, the engine was an unexpectedly fine performer, being probably the best-performing diesel of its displacement available anywhere in the world as of 1948. It was also constructed to very high standards. If it had been available in Europe, it would doubtless have attracted considerable sales interest. 1948 also saw the appearance of a smaller variable-compression diesel model of basically similar design designated the Vivell Precision 035. This very compact and well-made .035 cuin. (0.57cc) unit did not use any castings, being machined entirely from bar stock. Although also an RRV design, it was set up exclusively for radial mounting direct to the rear of the crankcase, a configuration which actually posed significant problems for the user in arranging an appropriate mounting in a model. The earliest versions of this engine had the contra-piston conventionally located in the cylinder bore, but the illustrated later variant reverted to the contra-piston-in-head approach used in the second model of the .102 cuin. design. The Vivell diesels are covered in my review of the Thermite 34 diesel which may be found elsewhere on this website. McCoy diesels (1953 – 1955)

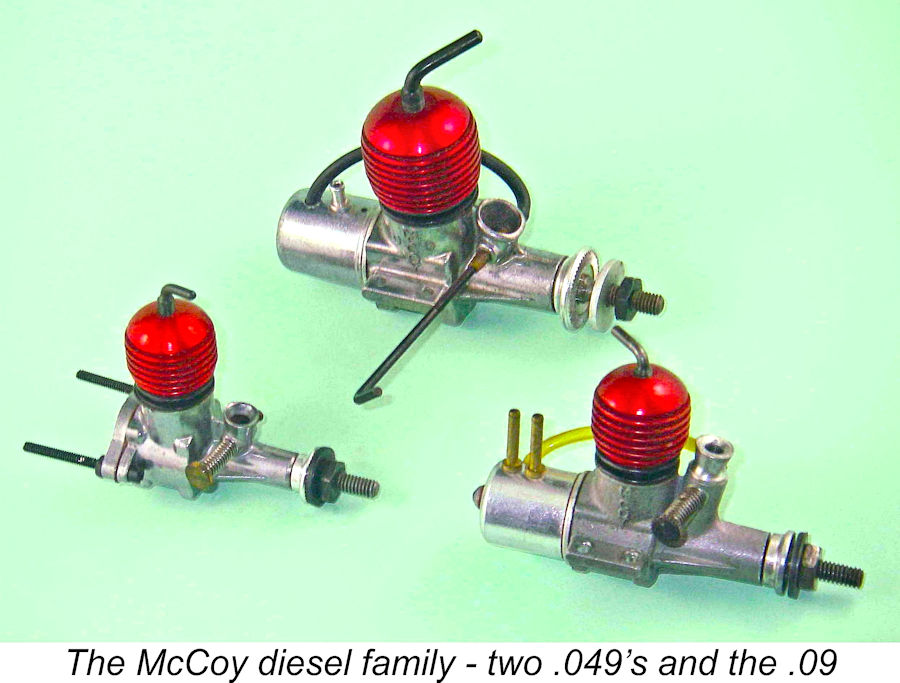

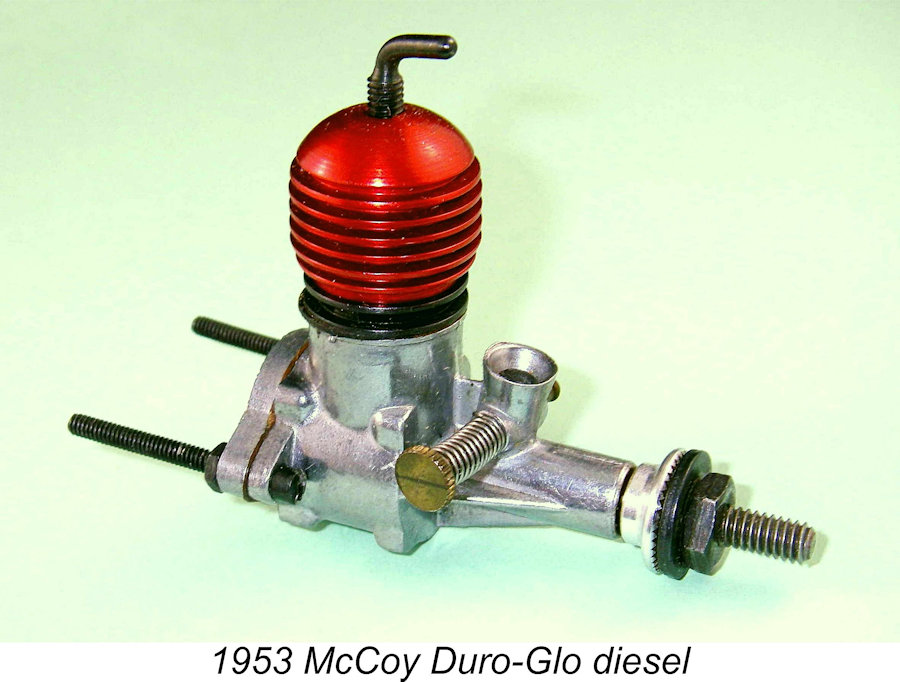

In 1954 an upgraded .049D version of this engine appeared. This had a beam mount crankcase and a far stronger larger-diameter crankshaft. Its performance was somewhat stifled by the inclusion of an atmospherically-activated “poppet valve” in the induction tract. Most users removed and discarded this fitting – the engines ran better without it. Also in 1954, the manufacturer introduced a larger .099 cuin. (1.637 cc) variant of what was basically the same engine, albeit without the poppet valve. This latter model was designated the McCoy 9. It was arguably one of the finest "1.5 cc" diesels ever manufactured during the classic era. In an online poll conducted some years ago on a widely-read modelling forum, the McCoy 9 was voted by an international readership as the finest classic model diesel of their collective experience in the 1.5 cc/.099 cuin. displacement category. I fully concur with this assessment - my own tests show this to be a fine-handling and very powerful engine having a peak output of around 0.185 BHP @ 14,000 rpm - quite a performance by 1954 "sports engine" standards. A full review of the McCoy diesels may be found elsewhere on the MEN website. An updated edition of that article will appear in due course on this website. OK diesels (1953 – 1956)

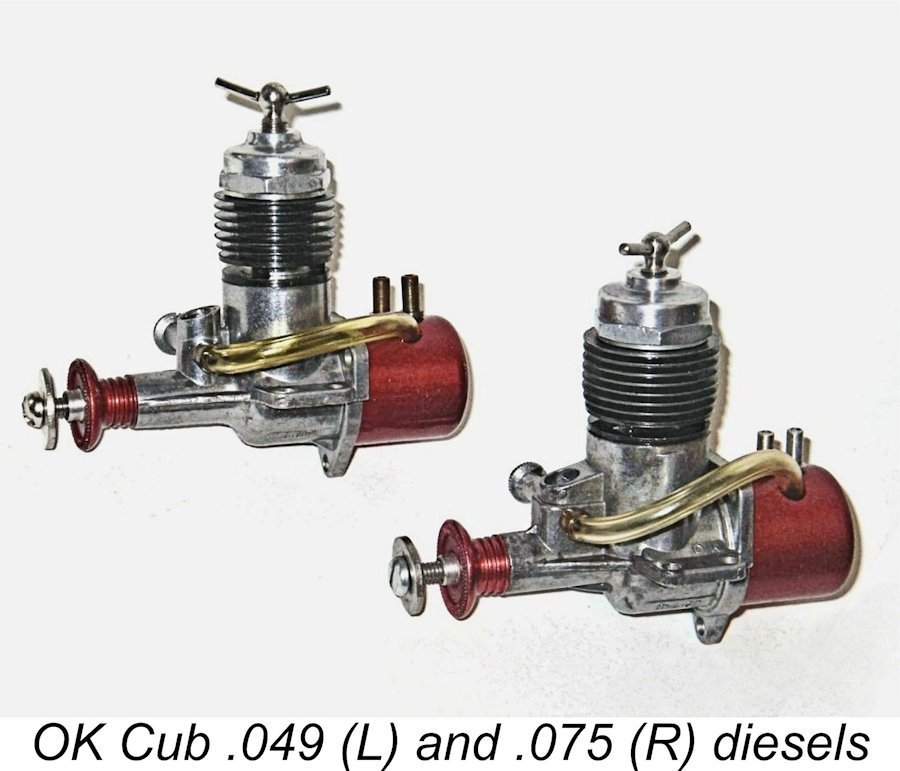

Interestingly enough, neither of the original OK diesel offerings had the same displacements as the far better-known .049 and .075 cuin. models which came later. Those initial offerings had displacements of 0.061 and 0.149 cuin. respectively. They seem to have been viewed as test pieces created specifically to evaluate the OK Cub diesel design concept. They were made in very small numbers. Tests of the .06 and .149 cuin. OK diesel models may be found elsewhere on this website. Very few of these early Cub diesels were sold in the USA, although they were briefly listed by America's Hobby Center (AHC). Instead, they were distributed very quietly on a trial basis, mainly in the established diesel territories of Europe and South America. Surviving examples are extremely rare today. The These experimental models were soon replaced by the familiar .049 and .075 cuin. diesels. These light, compact and well-made little engines were notable for the very ingenious "shock absorber" system which was built into their cylinder assemblies in an effort to minimize shock loadings on the working parts during operation. They also featured contra-pistons which sealed with O-rings. Once one got used to the feel of this system, the engines started and ran very well indeed by contemporary standards. Despite this, they did not find lasting favor with the American public, being phased out during the latter half of the 1950's. A full review of the OK diesels may be found elsewhere on this website. Discussion This completes my survey of model diesel engine developments in early post-WW2 America. I hope I’ve shown that the development of model diesels was pursued very seriously by a surprising number of American manufacturers. Many of the resulting designs must be viewed as doing credit to their designers and constructors, possessing considerable merit by any objective standard. The key point to note here is that the diesel concept was initially very far from being rejected in America, as many folks seem to believe. On the contrary, both manufacturers and practical modellers alike appear to have embraced the technology with considerable enthusiasm, at least in the early stages prior to 1948. A number of very positive diesel-related articles in the contemporary American modelling media certainly attest to this. This being the case, we have to ask – why didn’t the diesel ultimately take root in America to the extent that it did in Europe and elsewhere? American designers and manufacturers of model diesels got off to a very good start – why wasn’t the momentum sustained?

The event which initiated the rapid eclipse of the diesel in the USA was Ray Arden’s introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug in late 1947. This offered a viable alternative ignition technology which combined the diesel’s advantage of dispensing with the airborne ignition support system with the potential for application to the operation of existing large-displacement spark ignition engines and further developments of those designs.

The domestic manufacture of glow-plugs in England also commenced at this time. Later in 1948 the first purpose-built British glow-plug engine designs such as the FROG 160 and the Nordec RG10 also began to make their appearance, soon to be followed by others from the likes of ETA and Yulon. So the European and American markets were impacted by the same technological development at more or less the same time. Logic might lead one to expect a similar response from modellers in both areas. However, the near-simultaneous introduction of the glow-plug in both Europe and America had very different results in the two regions.

By contrast, the appearance of the glow-plug in America immediately swept all further consideration of the diesel concept off the table in that country, just as American designers and manufacturers of diesels were getting into their stride. I sometimes wish that Ray Arden had been a few years later in marketing the glow-plug – given a little more time to take root, diesels might well have gained as much acceptance in America as they did in the rest of the world, and American manufacturers might have continued to carry the diesel torch for quite a while with very positive results.

In this respect, the European and American modelling communities undoubtedly fared somewhat differently. In European countries such as Italy, France, Denmark, Switzerland, Norway and Sweden, the early post-war distribution of diesels was quite widespread, having actually begun while the war was still ongoing. Moreover, the vast majority of European model diesels which were available as of 1945 and beyond were highly practical units which recommended themselves and their underlying technology to both users and observers, thus fulfilling a very positive ambassadorial role.

During the period from early 1946 onwards, quality European diesels such as the MOVO D-2 were certainly available in America to take on the ambassadorial role. However, their numbers were relatively small, while their sales and distribution were largely handled by the major hobby supply companies such as Polk’s Hobbies, as opposed to Moreover, America is geographically a far larger country than Britain or any other European country. Consequently, the various American-made diesels which were inspired by the European imports tended to be distributed for the most part in their immediate areas of production. The distribution of diesels among the far-flung American modelling public was thus considerably more fragmentary than it was in Europe. In large areas of the country, the reputation of the diesel was largely dependent upon what we might call the “grapevine”, namely word of mouth or published comments from other modellers having direct experience of these engines. No Internet or email in those days ………..

The Deezil’s unknown designer came up with a highly serviceable engine which was manufactured at the outset to a very good standard, albeit in relatively small quantities. I have several of these very rare originals, which are extremely well-made units having a fine performance. Unfortunately, at this point the fate of the Deezil became enmeshed in what amounted to a family feud among the four Winston brothers of New York City who had participated as equal partners in the establishment of AHC in 1931. When America joined WW2 in December 1941, the two younger brothers enlisted in the US armed forces and went off to "do their bit", leaving the elder two behind to keep the AHC business going. Both of the military Winstons survived the war and returned to New York, presumably expecting to resume their involvement with AHC, which was still very much a going (and growing) concern. However, this is where things began to get a bit rocky - the stay-at-homes refused to let them back in! The outcome of this chain of events was an immediate move by the rejected brothers to establish their own model supply business in direct competition with their AHC siblings. Thus was born the major player in the Deezil saga, the Gotham Hobby Co. It's extremely difficult to resist the conclusion that a desire by the rejected Winstons to beat their brothers at their own game must have played a significant role in this development. Once established, the Gotham Hobby brothers looked around for products with which to compete with their AHC relatives. Unfortunately, they quickly came across the locally-produced Deezil. Seeing this as an opportunity to enter the market with their own diesel model in competition with the AHC diesel which their brothers were then known to be developing, they somehow brokered a deal whereby they took over the Deezil design wholesale.

Along with this went an aggressive marketing policy which extolled the “virtues” of the engine to the skies notwithstanding the fact that few of the Gotham engines would even run. Moreover, any that did so generally failed after a few seconds of running. Believe me, many have tried – few have succeeded! Basically, what had originally been an excellent $12.95 engine was trashed down to a $2.95 paperweight. However, the unsuspecting public did not know this. As a result, the Deezil’s seductively low price and falsely-claimed virtues combined to ensure that tens of thousands of them got out into the American hobby community. It’s easy to imagine the reaction of a modeller who received one of these sorry products, although why anyone would expect to receive a quality engine at that price is beyond me. Regardless, most of the engines went into the trash can, while the grapevine quickly spread the word that the "Deezil" was something to be strictly avoided. Now here’s the really unfortunate bit! The fact that the engine was called the Deezil resulted in a rapidly-spreading impression that investing in a “Deezil” was a waste of money. The fact that the terms “Deezil” and “diesel” are phonetically interchangeable meant that this view was rapidly transferred in the minds of the masses to all diesel engines, not only the Deezil. The more serious modellers knew the difference, of course, but they were in the minority. Sadly, the fact that the Gotham Deezil was sold in such large numbers inevitably threw it into the role of an ambassador model. Unfortunately, it was totally lacking in the qualities required to allow it to exert a positive influence in that role – on the contrary, it did much to besmirch the reputation of the diesel among ordinary modellers in America. If it had borne a different name, the damage might have been less severe. In summary then, the failure of the diesel to catch on in America despite the promising efforts of a number of US manufacturers prior to 1948 was evidently due to a combination of three main factors:

I suspect that if the glow-plug had not appeared when it did to offer a viable alternative, the diesel might well have been able to weather the damage to its reputation in America stemming from the advent of the Gotham Deezil. Think about it - in such a case, the ½A glow-plug revolution which began in 1949 would not As it was, a somewhat ephemeral American diesel renaissance did take place in the mid 1950’s as a result of the previously-noted efforts of McCoy and Herkimer (OK). It’s an often-overlooked fact that the very favorable published media reviews of these engines stimulated a diesel comeback of sorts in America at around this time. The positive attributes reflected in these test reports were quickly recognized by the American aeromodelling fraternity, with the result that the McCoy Duro-Glo diesel soon became a serious contender for all forms of ½A competition other than all-out speed. Indeed, it became the engine to use in the popular AMA free-flight ½A PAA-load category. The slightly later OK Cub diesels were also positively received, at least for a time.

As a result, the mid-1950’s diesel comeback in America faded quickly, with a lot of excellent American diesels being consigned to the sidelines (and subsequently to eBay!) for most of the post-war period apart from a few specialized uses such as FAI team racing, in which ether-burning American modellers were to excel. In my personal view, this virtual abandonment of diesels was America’s loss………….. ____________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published January 2024

|

| |

Most serious model engine aficionados are aware that the model diesel (or more correctly, compression ignition) engine first appeared in pre-WW2 Switzerland and Germany, being further developed during the wartime years in various neutral or occupied countries. Naturally, the hostilities which engulfed Europe during those years prevented much coordinated development from taking place. However, the conclusion of the war created conditions under which both the pace of model engine development and the international exchange of relevant information were greatly accelerated.

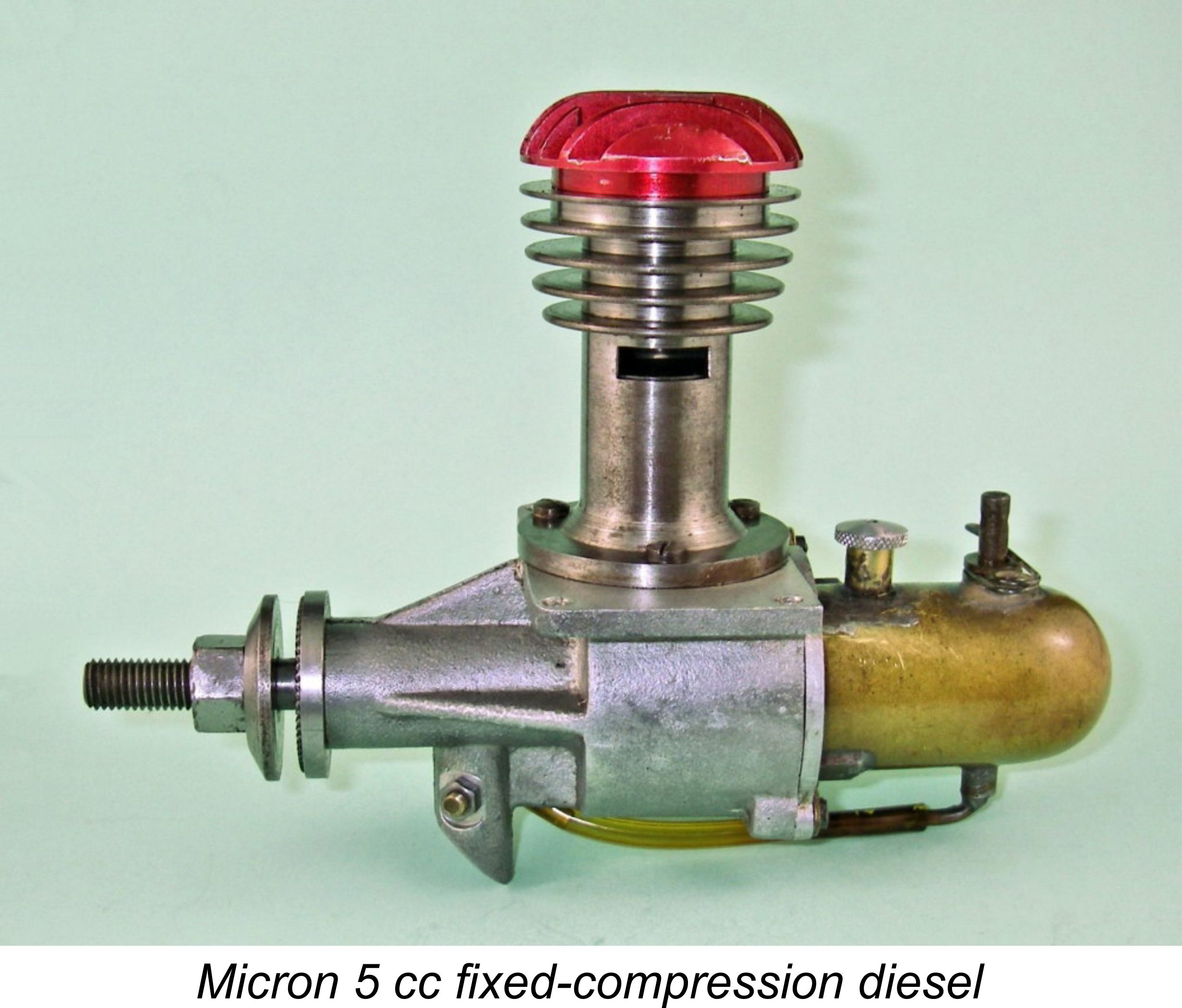

Most serious model engine aficionados are aware that the model diesel (or more correctly, compression ignition) engine first appeared in pre-WW2 Switzerland and Germany, being further developed during the wartime years in various neutral or occupied countries. Naturally, the hostilities which engulfed Europe during those years prevented much coordinated development from taking place. However, the conclusion of the war created conditions under which both the pace of model engine development and the international exchange of relevant information were greatly accelerated. However, this began to change shortly after the mid-1945 conclusion of WW2, when returning US servicemen started bringing European diesels back home with them in increasing numbers. Their fellow American modellers quickly noted that these engines performed very well, some punching significantly above their weight in power-for-displacement terms. The French Micron 5 cc fixed-compression model was a notable example, greatly influencing the design of the very successful American Drone diesel (see below). The

However, this began to change shortly after the mid-1945 conclusion of WW2, when returning US servicemen started bringing European diesels back home with them in increasing numbers. Their fellow American modellers quickly noted that these engines performed very well, some punching significantly above their weight in power-for-displacement terms. The French Micron 5 cc fixed-compression model was a notable example, greatly influencing the design of the very successful American Drone diesel (see below). The  Over the course of developing my long-running series of articles on model engine history, I’ve written detailed accounts covering all of the various diesel designs which originated from American commercial manufacturers. Having completed this task, I saw value in making an effort to render the overall history of American diesel developments both more readily accessible and easier to place in context.

Over the course of developing my long-running series of articles on model engine history, I’ve written detailed accounts covering all of the various diesel designs which originated from American commercial manufacturers. Having completed this task, I saw value in making an effort to render the overall history of American diesel developments both more readily accessible and easier to place in context.  This late 1945 side-port design appears to have been the first model diesel to originate in the workshop of an established American manufacturer, in this case Jim Brown, who produced the Thermite range in Oakland, California from 1941 until late 1945 before becoming involved with the Vivell range. This extremely well-made 0.34 cuin. (5.57 cc) unit featured variable compression using an eccentric crankshaft bearing – a design concept which had originated in wartime France.

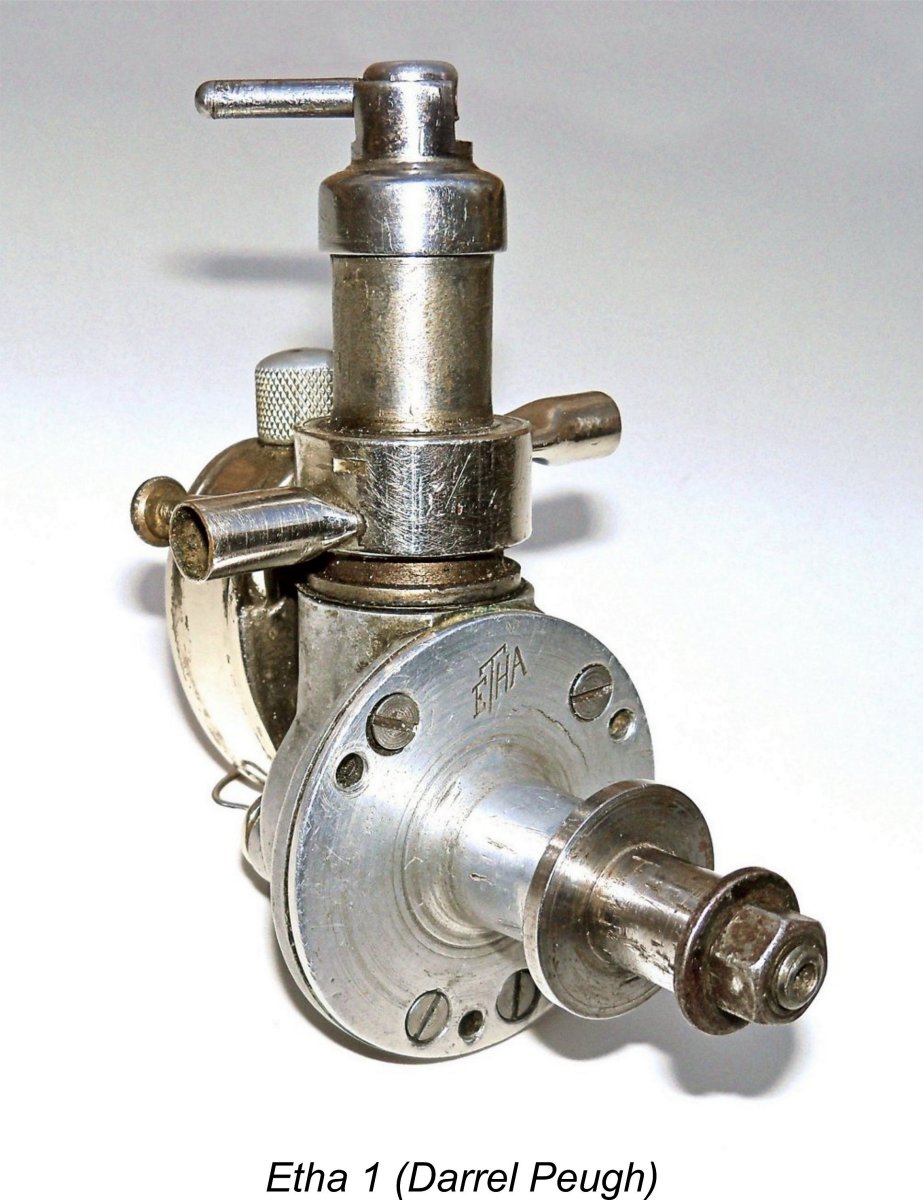

This late 1945 side-port design appears to have been the first model diesel to originate in the workshop of an established American manufacturer, in this case Jim Brown, who produced the Thermite range in Oakland, California from 1941 until late 1945 before becoming involved with the Vivell range. This extremely well-made 0.34 cuin. (5.57 cc) unit featured variable compression using an eccentric crankshaft bearing – a design concept which had originated in wartime France. The Mite 0.099 diesel was a crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) fixed-compression magnesium-case unit which was manufactured by the Mite Mfg. Co. of Brooklyn, New York beginning in late 1946. It was claimed as the first commercially-produced American diesel, a claim which may or may not be correct (see below) - but who really cares?!? The engine was designed by Howard Manderville, who may have been influenced in design terms by the very similar 1944 French Jidé 1.7 cc diesel, a few examples of which evidently reached America following the conclusion of WW2.

The Mite 0.099 diesel was a crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) fixed-compression magnesium-case unit which was manufactured by the Mite Mfg. Co. of Brooklyn, New York beginning in late 1946. It was claimed as the first commercially-produced American diesel, a claim which may or may not be correct (see below) - but who really cares?!? The engine was designed by Howard Manderville, who may have been influenced in design terms by the very similar 1944 French Jidé 1.7 cc diesel, a few examples of which evidently reached America following the conclusion of WW2.

The C.I.E. 10 side-port diesel is the other candidate for the title of “America’s first diesel”. There’s no doubt that it was one of the first model diesels to appear in the USA in production form following the conclusion of WW2. Beginning in late 1946, it was manufactured initially by the Compression Ignition Engines division of Modelcraft Hobbies of Los Angeles, California. The actual designers and manufacturers were a pair of gentlemen named Barney Snyder and William (Bill) A. Ruff. Later the manufacture of the design was taken over by a different company called Hy-Pro Engines, also of Los Angeles. Hy-Pro production continued until early 1948. It appears that some 3,000 examples may have been manufactured in total.

The C.I.E. 10 side-port diesel is the other candidate for the title of “America’s first diesel”. There’s no doubt that it was one of the first model diesels to appear in the USA in production form following the conclusion of WW2. Beginning in late 1946, it was manufactured initially by the Compression Ignition Engines division of Modelcraft Hobbies of Los Angeles, California. The actual designers and manufacturers were a pair of gentlemen named Barney Snyder and William (Bill) A. Ruff. Later the manufacture of the design was taken over by a different company called Hy-Pro Engines, also of Los Angeles. Hy-Pro production continued until early 1948. It appears that some 3,000 examples may have been manufactured in total.  The KEN 61 racing spark-ignition engine appeared in mid-1946. It was the brainchild of Ken Wade, a high school teacher in Garden Grove, California. Apart from his teaching activities in the fields of woodworking and auto mechanics, Wade was also a skilled model maker and model engineer. His design utilized a very unusual front rotary disc arrangement in which the crankweb doubled as the disc valve. Although extremely interesting in a technical sense, the Ken 61 offered nothing special in the way of performance, hence meeting with very limited sales success. Just over 1000 examples were apparently completed.

The KEN 61 racing spark-ignition engine appeared in mid-1946. It was the brainchild of Ken Wade, a high school teacher in Garden Grove, California. Apart from his teaching activities in the fields of woodworking and auto mechanics, Wade was also a skilled model maker and model engineer. His design utilized a very unusual front rotary disc arrangement in which the crankweb doubled as the disc valve. Although extremely interesting in a technical sense, the Ken 61 offered nothing special in the way of performance, hence meeting with very limited sales success. Just over 1000 examples were apparently completed.  The AHC (America's Hobby Center) diesel of 0.12 cuin. (2 cc) displacement is a classic example of a commercial model engine that never was! It was designed by AHC boss Bernie Winston during 1946, being scheduled for release to the public in 1947. At least one prototype was completed, along with the necessary crankcase die. A sizeable batch of perhaps 1000 crankcase castings was produced using this die.

The AHC (America's Hobby Center) diesel of 0.12 cuin. (2 cc) displacement is a classic example of a commercial model engine that never was! It was designed by AHC boss Bernie Winston during 1946, being scheduled for release to the public in 1947. At least one prototype was completed, along with the necessary crankcase die. A sizeable batch of perhaps 1000 crankcase castings was produced using this die. There can be little question that the infamous 2 cc Deezil from New York must surely rank as one of the all-time worst model diesels ever to be foisted on an unsuspecting public! That said, there is irrefutable evidence in the form of a number of surviving examples such as that illustrated here to confirm that the early examples which were manufactured in early 1947 by a very capable maker, whose identity is now lost in the mists of time, were actually perfectly sound engines. It was only after the Gotham Hobby organization took over in early 1948 that the engine was progressively trashed down to a ridiculously low price, with any pretense at quality being thrown out of the window.

There can be little question that the infamous 2 cc Deezil from New York must surely rank as one of the all-time worst model diesels ever to be foisted on an unsuspecting public! That said, there is irrefutable evidence in the form of a number of surviving examples such as that illustrated here to confirm that the early examples which were manufactured in early 1947 by a very capable maker, whose identity is now lost in the mists of time, were actually perfectly sound engines. It was only after the Gotham Hobby organization took over in early 1948 that the engine was progressively trashed down to a ridiculously low price, with any pretense at quality being thrown out of the window.  The Arden spark ignition engines appeared almost immediately following the conclusion of WW2, immediately becoming very popular. As model engine history records, designer Ray Arden did not stand pat with his very successful .099 and .199 cuin. sparkies, proceeding to render them obsolete through his late 1947 introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug.

The Arden spark ignition engines appeared almost immediately following the conclusion of WW2, immediately becoming very popular. As model engine history records, designer Ray Arden did not stand pat with his very successful .099 and .199 cuin. sparkies, proceeding to render them obsolete through his late 1947 introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug.  The 5 cc Drone Diesel is arguably one of the best model diesels ever to originate in the USA. This sturdy and very well-made fixed-compression diesel was designed and manufactured by the well-known US modeller Leon Shulman, who was strongly influenced by the French Micron 5 cc fixed compression model, examples of which had been showing up in America since mid-1945.

The 5 cc Drone Diesel is arguably one of the best model diesels ever to originate in the USA. This sturdy and very well-made fixed-compression diesel was designed and manufactured by the well-known US modeller Leon Shulman, who was strongly influenced by the French Micron 5 cc fixed compression model, examples of which had been showing up in America since mid-1945.  In early 1947, a certain Mr. Frank Howarth, owner of a company called Engineering Development Co. Inc. (EDCO) of Del Mar, an oceanside community lying a little to the north of San Diego, California decided to introduce a mass-produced version of Ira Hassad’s very powerful Custom 61 FRV racing engine, bringing Hassad on board to help with this endeavour. The resulting engine appeared in 1947 as the well-known EDCO Sky Devil spark ignition unit. Although a very fine engine in its own right, it couldn't match the Hassad original in performance terms.

In early 1947, a certain Mr. Frank Howarth, owner of a company called Engineering Development Co. Inc. (EDCO) of Del Mar, an oceanside community lying a little to the north of San Diego, California decided to introduce a mass-produced version of Ira Hassad’s very powerful Custom 61 FRV racing engine, bringing Hassad on board to help with this endeavour. The resulting engine appeared in 1947 as the well-known EDCO Sky Devil spark ignition unit. Although a very fine engine in its own right, it couldn't match the Hassad original in performance terms. The 4.85 cc (0.296 cuin.) Speed Demon 30 was a side-port barstock diesel made to very high standards in relatively small numbers (around 500 in total) in Long Island, New York, USA for less than a year beginning in late 1947. It featured variable compression by moving liner rather than the more familiar contra-piston arrangement. In this, it followed the design of the earlier

The 4.85 cc (0.296 cuin.) Speed Demon 30 was a side-port barstock diesel made to very high standards in relatively small numbers (around 500 in total) in Long Island, New York, USA for less than a year beginning in late 1947. It featured variable compression by moving liner rather than the more familiar contra-piston arrangement. In this, it followed the design of the earlier  The 0.28 cuin. (4.55 cc) Air-O Diesel was a sideport diesel manufactured by Ray Accord’s Air-O Model Supply Co. of Hawthorne, California. Contrary to an often-reiterated error, it had absolutely nothing to do with the Bunch Model Airplane Co. of Los Angeles, California – the Air-O company had acquired the assets of the Bunch company in 1946, well prior to the development of the Air-O Diesel. A certain amount of Bunch design influence could be seen in the design of the Air-O Diesel, but there was no other connection.

The 0.28 cuin. (4.55 cc) Air-O Diesel was a sideport diesel manufactured by Ray Accord’s Air-O Model Supply Co. of Hawthorne, California. Contrary to an often-reiterated error, it had absolutely nothing to do with the Bunch Model Airplane Co. of Los Angeles, California – the Air-O company had acquired the assets of the Bunch company in 1946, well prior to the development of the Air-O Diesel. A certain amount of Bunch design influence could be seen in the design of the Air-O Diesel, but there was no other connection.

The Micro Diesel was an American side-port diesel engine of 0.13 cuin. (2.13 cc) displacement which was manufactured in relatively small numbers by the Micro Diesel Co. of Detroit, Michigan between late 1947 and mid 1948. The engine was built to very high standards, also performing very well by comparison with its contemporaries. Purely on merit, it ranks as one of the finest model diesels to emerge from the early post-WW2 American model engine manufacturing industry, although its performance suffered somewhat from an evident manufacturing error which resulted in the conrod being made too long, with negative effects upon the engine’s port timing. Even so, tests on an original example showed a peak output of around 0.099 BHP @ 6,700 RPM.

The Micro Diesel was an American side-port diesel engine of 0.13 cuin. (2.13 cc) displacement which was manufactured in relatively small numbers by the Micro Diesel Co. of Detroit, Michigan between late 1947 and mid 1948. The engine was built to very high standards, also performing very well by comparison with its contemporaries. Purely on merit, it ranks as one of the finest model diesels to emerge from the early post-WW2 American model engine manufacturing industry, although its performance suffered somewhat from an evident manufacturing error which resulted in the conrod being made too long, with negative effects upon the engine’s port timing. Even so, tests on an original example showed a peak output of around 0.099 BHP @ 6,700 RPM. This summary began with a mention of the prototype Thermite 34 diesel produced in late 1945 by Jim Brown prior to his becoming fully involved with the manufacture of the Vivell range for Earl Vivell. The Thermite 34 never got past the prototype stage, but in 1947 Earl Vivell authorized Jim Brown to develop and manufacture a series of diesel models under the Vivell Precision designation.

This summary began with a mention of the prototype Thermite 34 diesel produced in late 1945 by Jim Brown prior to his becoming fully involved with the manufacture of the Vivell range for Earl Vivell. The Thermite 34 never got past the prototype stage, but in 1947 Earl Vivell authorized Jim Brown to develop and manufacture a series of diesel models under the Vivell Precision designation.  applied to the Thermite by Jim Brown. The engine performed very well on a correctly-matched fuel and prop combination.

applied to the Thermite by Jim Brown. The engine performed very well on a correctly-matched fuel and prop combination.

The McCoy diesels began appearing in early 1953 following a 4-year period during which diesel development in the USA had stalled completely apart from some behind-the-scenes experimental work by Dick McCoy. The initial result of Dick's efforts was the early 1953 appearance of the original radial-mount .049 Duro-Glo diesel model. This engine ran extremely well but suffered from a rather undernourished crankshaft which led to frequent breakages.

The McCoy diesels began appearing in early 1953 following a 4-year period during which diesel development in the USA had stalled completely apart from some behind-the-scenes experimental work by Dick McCoy. The initial result of Dick's efforts was the early 1953 appearance of the original radial-mount .049 Duro-Glo diesel model. This engine ran extremely well but suffered from a rather undernourished crankshaft which led to frequent breakages.  The OK diesels represented the final attempt by an American mass producer of model engines to market the compression ignition concept to the American public. The first OK diesel models appeared with little fanfare in mid-1953, a few months after the advent of the competing McCoy .049 Duro-Glo diesel model mentioned earlier. Indeed, it was probably the early 1953 appearance of the McCoy Duro-Glo diesel that prompted the quick development of the OK diesels.

The OK diesels represented the final attempt by an American mass producer of model engines to market the compression ignition concept to the American public. The first OK diesel models appeared with little fanfare in mid-1953, a few months after the advent of the competing McCoy .049 Duro-Glo diesel model mentioned earlier. Indeed, it was probably the early 1953 appearance of the McCoy Duro-Glo diesel that prompted the quick development of the OK diesels.

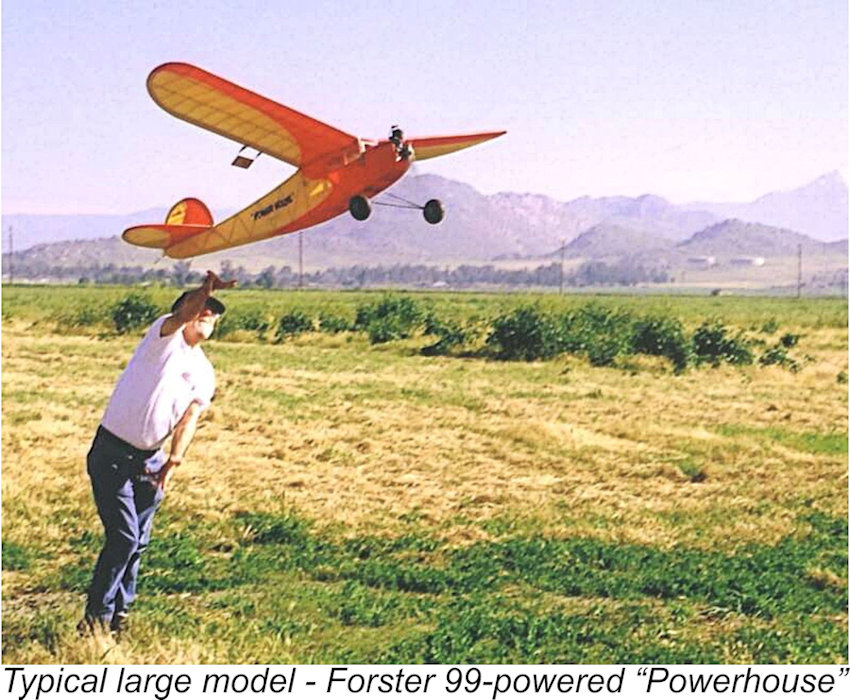

Well, for one thing the previously-noted American preference for large models undoubtedly played a part, at least in the period up to early 1948. While diesels could certainly compete with their spark ignition and (later) glow-plug rivals in the small and medium displacement categories widely favored in Europe, it was some years before they began to appear as suitable powerplants for the larger models which the Americans still tended to favor. Prior to early 1948, large spark ignition engines continued to be the only game in town for such models, tending to inhibit diesel sales in America by comparison with Europe, where smaller models were generally preferred.

Well, for one thing the previously-noted American preference for large models undoubtedly played a part, at least in the period up to early 1948. While diesels could certainly compete with their spark ignition and (later) glow-plug rivals in the small and medium displacement categories widely favored in Europe, it was some years before they began to appear as suitable powerplants for the larger models which the Americans still tended to favor. Prior to early 1948, large spark ignition engines continued to be the only game in town for such models, tending to inhibit diesel sales in America by comparison with Europe, where smaller models were generally preferred. This event is often cited as the main reason for the diesel’s failure to gain a secure long-term foothold in America. However, in itself it doesn’t constitute an adequate explanation. After all, the same technology reached Europe almost immediately, as witness the fact that beginning in early 1948 a number of European manufacturers such as Britain’s

This event is often cited as the main reason for the diesel’s failure to gain a secure long-term foothold in America. However, in itself it doesn’t constitute an adequate explanation. After all, the same technology reached Europe almost immediately, as witness the fact that beginning in early 1948 a number of European manufacturers such as Britain’s

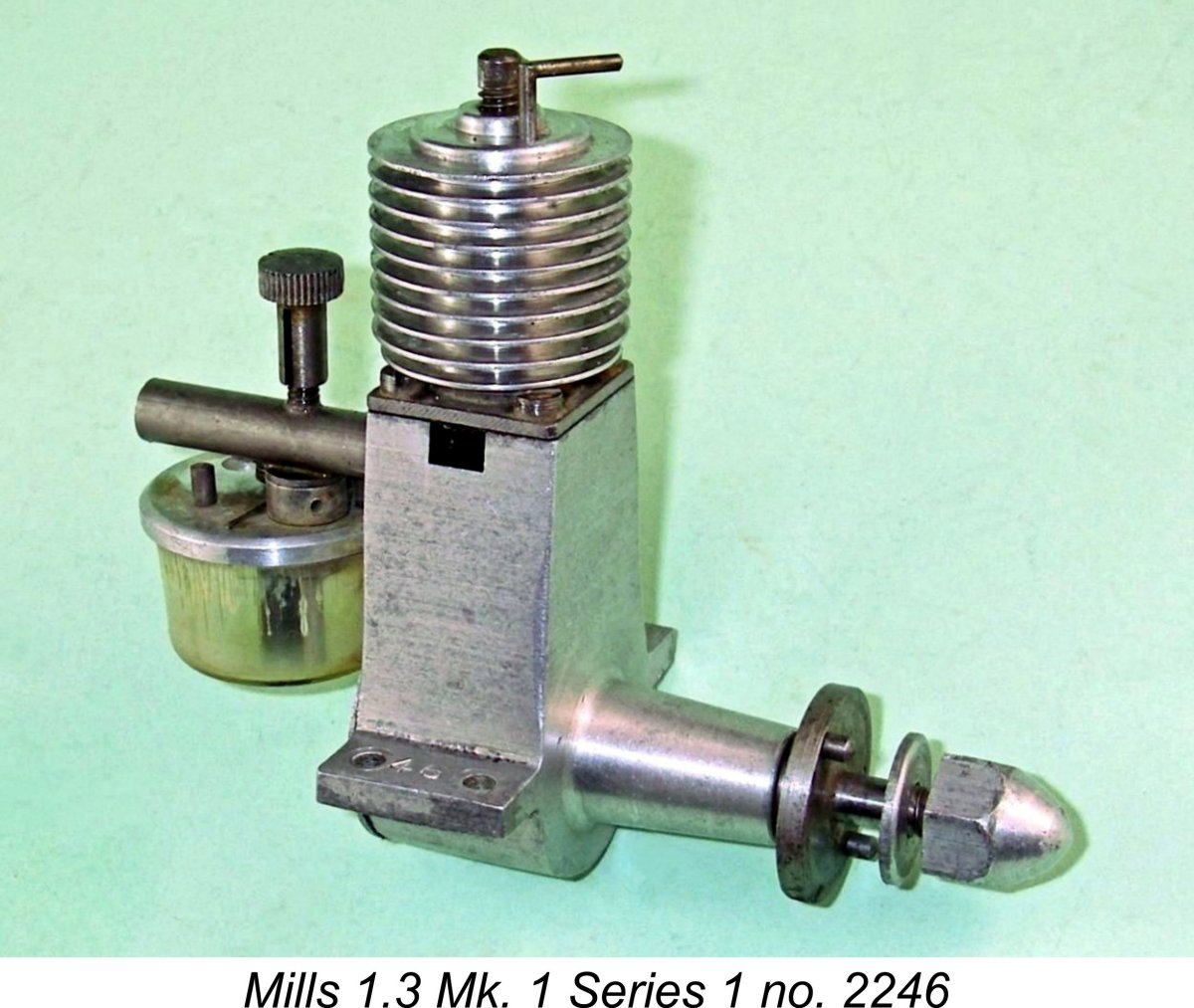

Due to its earlier wartime preoccupations, Britain was relatively late in hopping onto the model diesel bandwagon. However, the British designers caught up very rapidly. The first British diesel to become widely available was the

Due to its earlier wartime preoccupations, Britain was relatively late in hopping onto the model diesel bandwagon. However, the British designers caught up very rapidly. The first British diesel to become widely available was the

In terms of the reputation of the model diesel in North America, this might have been of no great consequence if Gotham Hobby had maintained the excellent quality of the original engines. However, they adopted a policy of extreme cost-cutting, purely to enable them to undercut their AHC rivals by offering the engines at ridiculously low prices. Beginning in early 1948, the poor old Deezil was progressively trashed down to a truly abysmal level of quality which in my extensive experience was unparalleled anywhere in the model diesel world.

In terms of the reputation of the model diesel in North America, this might have been of no great consequence if Gotham Hobby had maintained the excellent quality of the original engines. However, they adopted a policy of extreme cost-cutting, purely to enable them to undercut their AHC rivals by offering the engines at ridiculously low prices. Beginning in early 1948, the poor old Deezil was progressively trashed down to a truly abysmal level of quality which in my extensive experience was unparalleled anywhere in the model diesel world.

However, this positive view of diesels among American modellers was not to last. A primary reason for this appears to have been the seemingly spotty availability of ready-mixed diesel fuel. Both McCoy and OK marketed excellent fuels for their respective diesel models, but these fuels were evidently omitted from the order books of far too many US retailers. As a result, many US modellers of the mid-1950's were unable to secure a dependable supply of fuel for their diesels. This undoubtedly discouraged their use – in fact, a number of modelling forums have carried postings from American old-timers to the effect that they gave up on diesels in the 1950’s for precisely this reason.

However, this positive view of diesels among American modellers was not to last. A primary reason for this appears to have been the seemingly spotty availability of ready-mixed diesel fuel. Both McCoy and OK marketed excellent fuels for their respective diesel models, but these fuels were evidently omitted from the order books of far too many US retailers. As a result, many US modellers of the mid-1950's were unable to secure a dependable supply of fuel for their diesels. This undoubtedly discouraged their use – in fact, a number of modelling forums have carried postings from American old-timers to the effect that they gave up on diesels in the 1950’s for precisely this reason.