|

|

The Super Tigre G.20 V on Test

In my earlier article on the classic Super Tigre engines, I outlined the start-to-finish development of the Super Tigre G.20 glow-plug models which constituted perhaps the most famous and widely-used Super Tigre series of that era. This iconic powerplant first appeared in 1950, thereafter passing through a series of progressively-improving variants extending all the way into the mid 1960’s. In its various forms, the G.20 was flown by competition modellers all over the world for the fifteen years following its introduction, garnering more than its fair share of contest wins in the process.

Although competitions open to 2.5 cc engines were held relatively frequently during the first half of the 1950’s, that displacement category did not acquire official FAI World Championship status until 1955. It was in that year that the FAI finally adopted the 2.5 cc displacement category as the standard for International power competitions held under FAI sanction. Naturally this resulted in the 2.5 cc category immediately acquiring a very high priority among manufacturers of competition engines, both diesel and glow-plug. The Super Tigre G.20 glow-plug unit was among the engines to which its manufacturer’s full attention was now diverted.

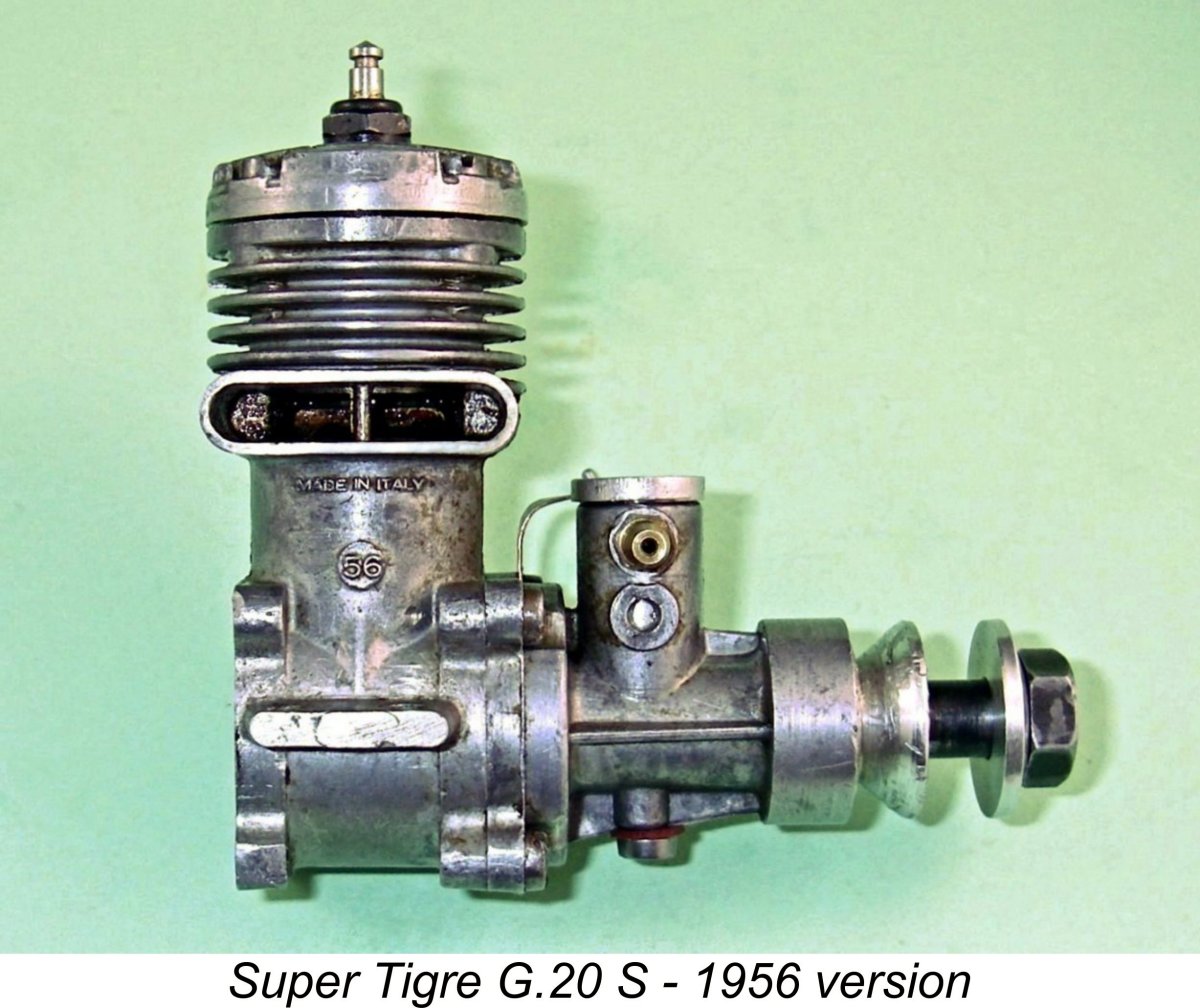

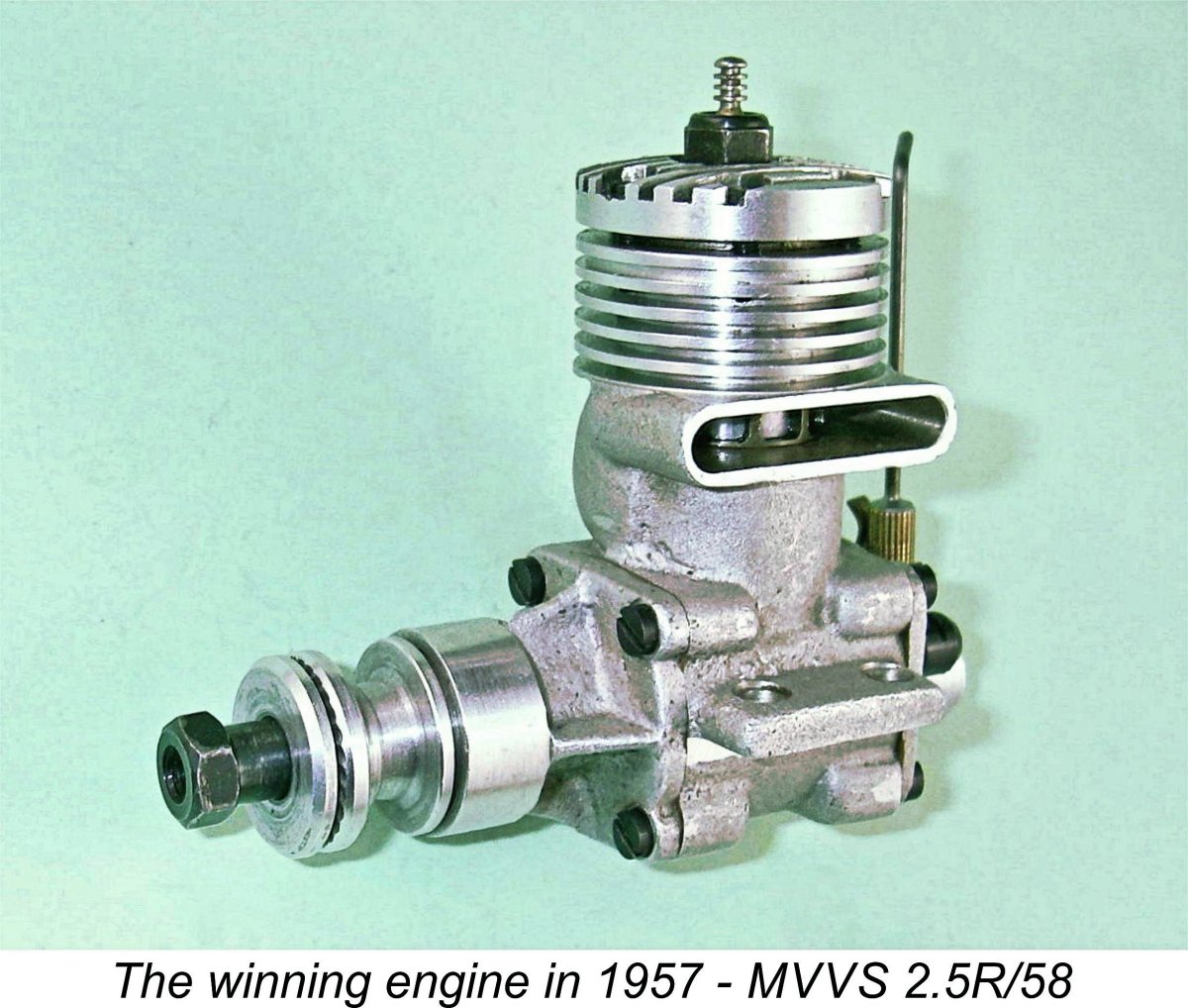

The Italians were clearly hoping and indeed expecting that the improved version of the G.20 S which they were all using would represent their ticket to a clean sweep of the results. They had considerable justification for their expectations - after all, no other commercial manufacturer was offering a competing product which could match the G.20 S in a control-line speed context at that time. This gave the Italians solid grounds for optimism. However, their hopes were derailed by the fact that this event coincided with the emergence of a new threat from the other side of the Iron Curtain. In October 1953 the Czech authorities had established an organization called the Modelářského Výzkumného a Vývojového Střediska (Modelling Research & Development Centre), better known by its initials of MVVS. The early history of the MVVS organization has been recounted in detail elsewhere.

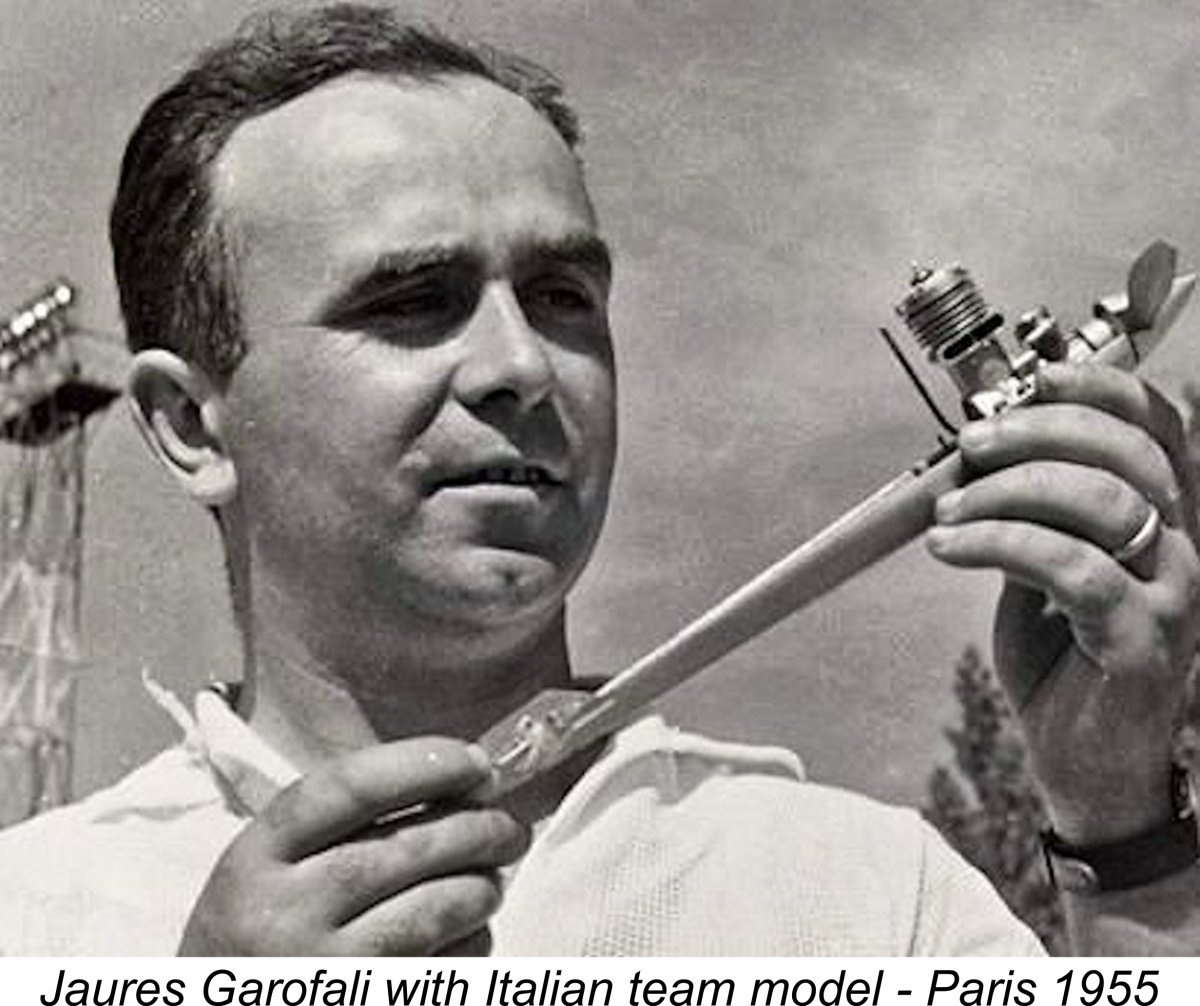

Super Tigre employee Amato Prati came in a frustratingly close second with his G.20 S powered model at a speed of 176.05 km/hr (109.39 mph), closely followed by his similarly-powered fellow Italian team members S. Monti and C. Cappi. Together with G. Gottarelli’s sixth place finish behind Mir Zatočil’s fifth-placed MVVS 25 (in essence, a crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) version of the winning SK-25), this was easily enough to give Italy the team title. However, the fact that the individual title had escaped cannot have sat well with Signor Garofali. Sladký’s success signalled the beginning of what might be termed the “works team” or “special” era in international control-line speed. Thenceforth there were in effect two distinct tiers of competitors – those using well-prepared examples of commercially-available engines and those using non-commercial individually-constructed “specials”. Events were to prove that the “specials” generally ruled the roost, with the commercial engines competing in what amounted to a separate category. As a commercial manufacturer having his eye upon his company's position in the international market, Garofali naturally remained true to the second category, choosing to compete using individually-prepared examples of his own commercial products.

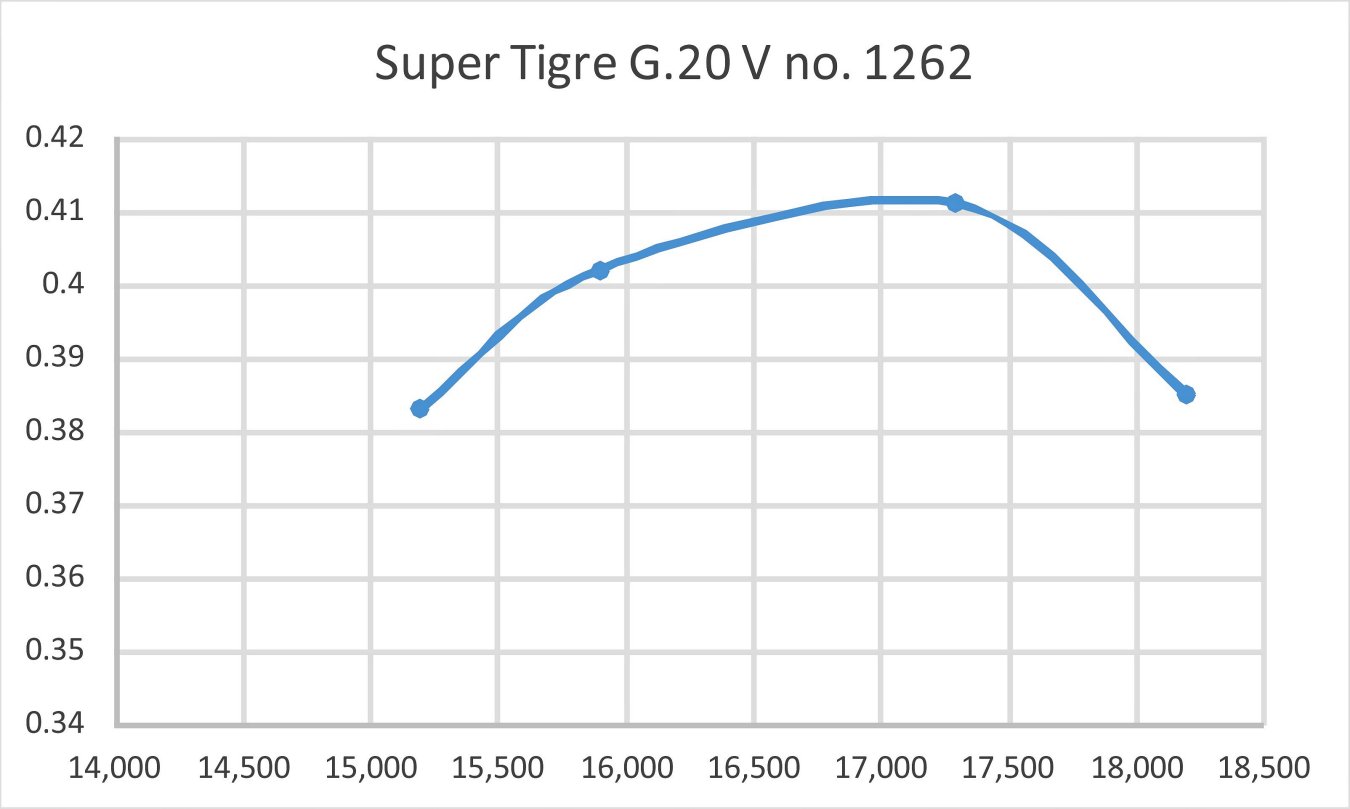

This was a most promising International debut, and there was even more to come. On May 20th, 1956, another well-known Italian speed flier, A. Marconi, used one of these engines in his “Tajavento” (Wind Cutter) model to achieve the then-remarkable speed of 215.56 km/h (133.95 mph), which established a new 2.5 cc FAI World Speed Record. Things were looking really good for that autumn World Championship meeting in Florence - based on its early competition successes, the revised design evidently represented real progress compared with its 1955 predecessor! A full test report on this fine engine appears separately on this website. That test showed that my very "experienced" example of the engine (which may be tuned – I haven’t taken it apart to check) develops over 0.410 BHP at around 17,500 RPM using a fuel containing 30% nitro. This is a sturdy performance indeed in a 1956 context. Clearly Garofali had tweaked this design to very good effect!

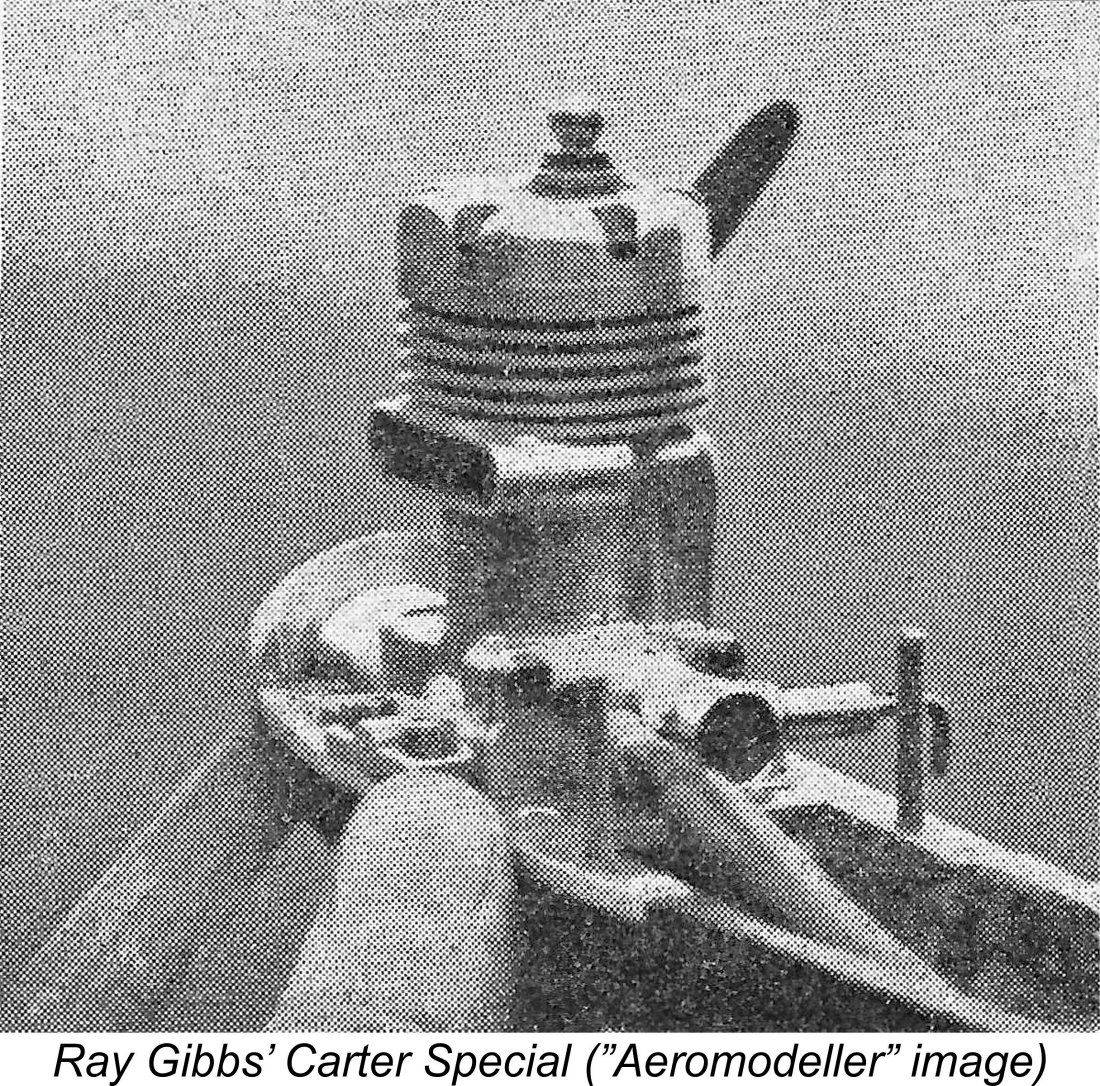

At the same meeting, Gibbs subsequently established a new FAI 2.5 cc World Record at a speed of 225 km/hr (139.81 mph) using thinner lines than those permitted in FAI competition, thus rubbing salt in the wound by eclipsing Marconi's previously-noted Super Tigre mark from earlier in the year. Some going for a normally aspirated (un-piped) 1956 loop scavenged motor flying on two lines! The best Super Tigre-powered Italian team speed was Amato Prati’s sixth place mark of 194 km/hr (120.55 mph) using a well tweaked 1956 Super Tigre G.20 S. It is to be doubted that Jaures Garofali viewed this result in a positive light despite the improvement over the 1955 speeds! However, he could take some comfort from the fact that no fewer than 12 entrants out of a total of 28 were using Super Tigre G.20 powerplants at the meeting. This certainly underscored the international reputation and consequent popularity which the engine had attained. It was undoubtedly the most powerful 2.5 cc racing glow-plug unit then available over the counter to the general public.

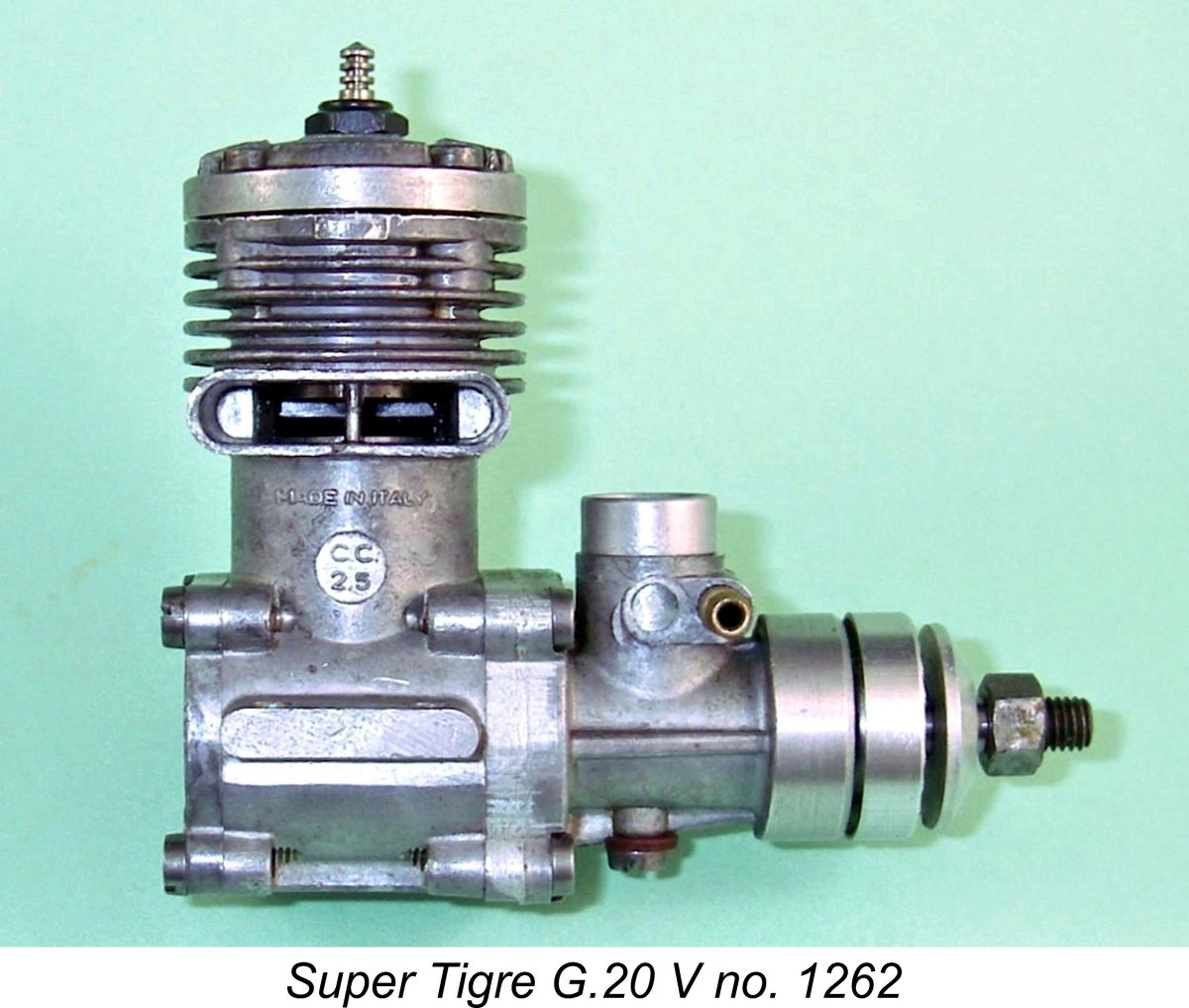

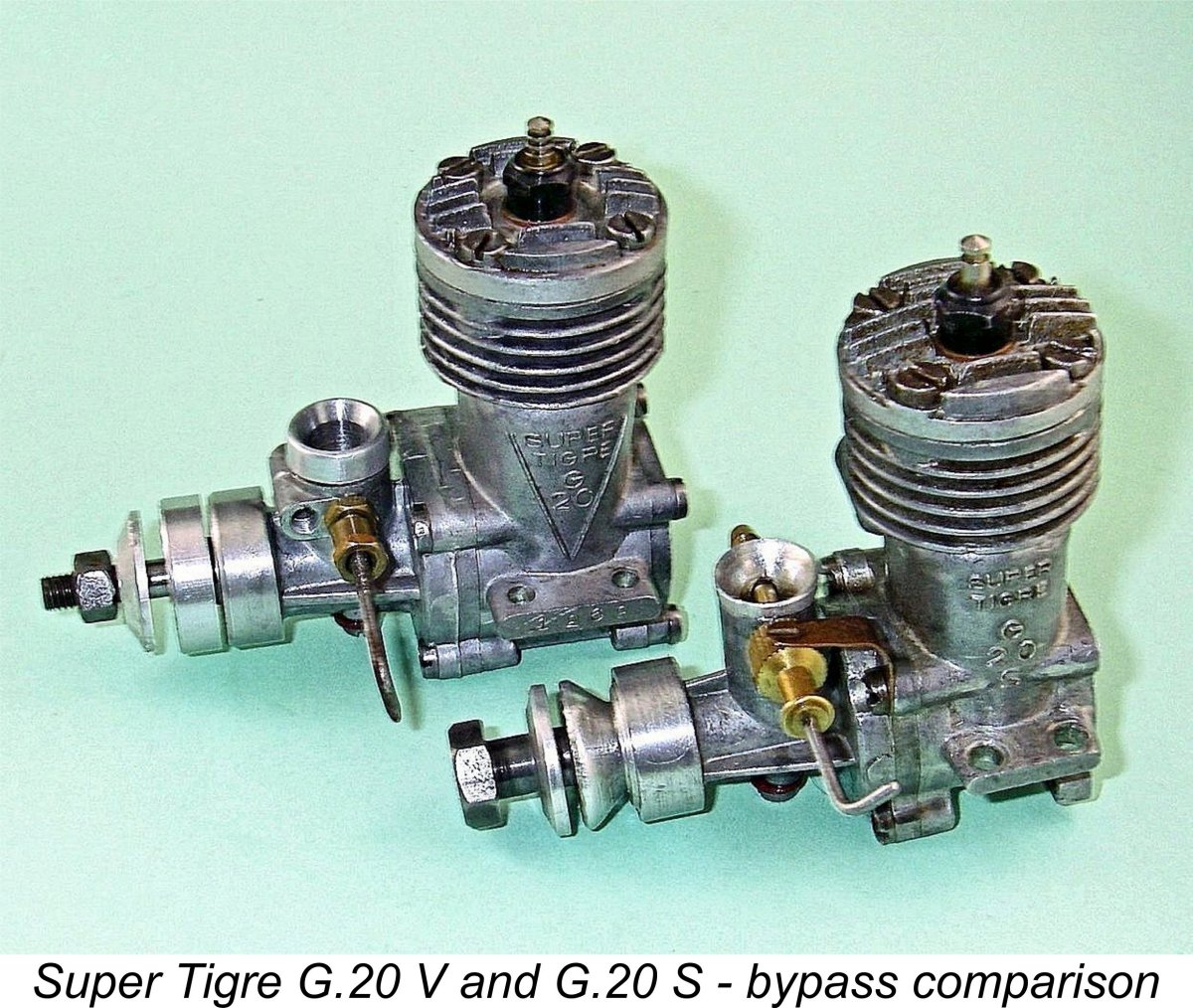

The new G.20 V retained many features of its 1956 predecessor, including the lapped cast iron baffle piston, FRV induction and twin ball-race crankshaft. However, it also featured a strengthened crankcase having far more sturdy mounting lugs, thus addressing an often-noted criticism of the earlier G.20 models. The revised crankcase was open at both ends, with the bolt-on front cover being retained and a new bolt-on rear cover being used in place of the former integrally-cast component. The bypass passage on the new model was considerably enlarged.

Provision was made for the installation of the needle valve either in a conventional transverse orientation or in a tangential location which placed the fuel jet on the intake venturi periphery. An alternative big-bore venturi insert was supplied for this purpose. The latter orientation would doubtless require the use of pressure fuel feed, for which provision was made by the inclusion of a crankshaft-timed pressure tapping point beneath the intake venturi. In addition, a number of internal improvements were also incorporated. One structural feature to note if you ever have to dismantle the carburettor assembly on one of these engines is the fact that the spraybar is threaded into the venturi insert body on the needle side when installed in transverse mode. People have been fooled by this into thinking that the spraybar was merely stuck in there by congealed castor oil residues. Not so - it has to be unscrewed from the fuel supply side. Ill-informed attempts to push it out can potentially lead to damage being done. The Super Tigre G.20 V on Test As far as I’m aware, the G.20 V was never the subject of a published test in the English-language modelling media. This being the case, it was up to me to put my completely original and unmodified example no. 1262 through its paces on the test bench. I obtained the engine many years ago from its original owner, my late friend Squadron Leader Laurie Ellis of "Javelan" fame. He had run the engine on the bench but had never actually flown it or disturbed it in any way. I had subsequently run the engine myself, but had never taken any prop/rpm readings from it beyond noting that it seemed to possess plenty of “urge”. This earlier running had confirmed that it was well run in and ready for some hard work. Although I have both styles of venturi on hand, I elected to test the engine in transverse spraybar mode, in which configuration it should work well on suction feed. The spraybar diameter is 4 mm, while the suction venturi that I used has an internal diameter of 7.5 mm. Reference to Maris Dislers’ invaluable Choke Area Calculator reveals that this combination provides an effective choke area of 15.67 square Upon setting the Super Tigre up in the test stand, it quickly became apparent that the carburettor setup which I was using was indeed pretty much right at the limit for suction operation, just as predicted. The engine would run rich on this configuration, but the needle had to be unscrewed almost all the way in order to achieve this condition. Nevertheless, the G.20 V proved to be an instant starter provided that a small exhaust prime was first administered. Once running, the engine showed itself to be a very smooth runner having excellent response to the needle - an optimum setting was easily established for each prop tested. Running was absolutely steady and completely mis-free all the way up to the highest speeds tested. I was expecting a pretty strong performance from this unit, and I wasn't disappointed! Using a "cold" glow-plug and a fuel containing 30% nitro, here's the data that I recorded:

As can be seen, my rather limited suite of suitable test props leaves a rather large gap between the 7x6 and 7x5 APC props. I should make up and calibrate a cut-down 7x6 to fill that gap. Even so, it's apparent that the engine achieved a maximum output of somewhere around 0.415 BHP @ 17,000 rpm. Interestingly enough, this almost exactly duplicated the measured output of the 1956 Super Tigre G.20 S which was the subject of a separate test to be found on this website. That earlier unit delivered an unexpectedly high output of 0.418 BHP @ 17,400 rpm. Mind you, the G.20 S was a well used and quite possibly modified example (it had seen top level free flight competition service before I acquired it), while the G.20 V which is the main subject of this article is completely stock in all respects and has never been mounted in a model. No doubt some knowledgeable tweaking and a bit more running time would result in a measureable improvement. Of course, neither motor came close to matching the truly remarkable peak output of around 0.470 BHP @ 18,500 rpm which I recorded during my test of the MVVS 2.5R-58. The relative contest results achieved by the MVVS and Super Tigre designs in 1957 and 1958 become readily understandable when we look at the above figures. In that vein, let's turn now to a review of the Super Tigre G.20 V's competition record. The Super Tigre G.20 V in Competition

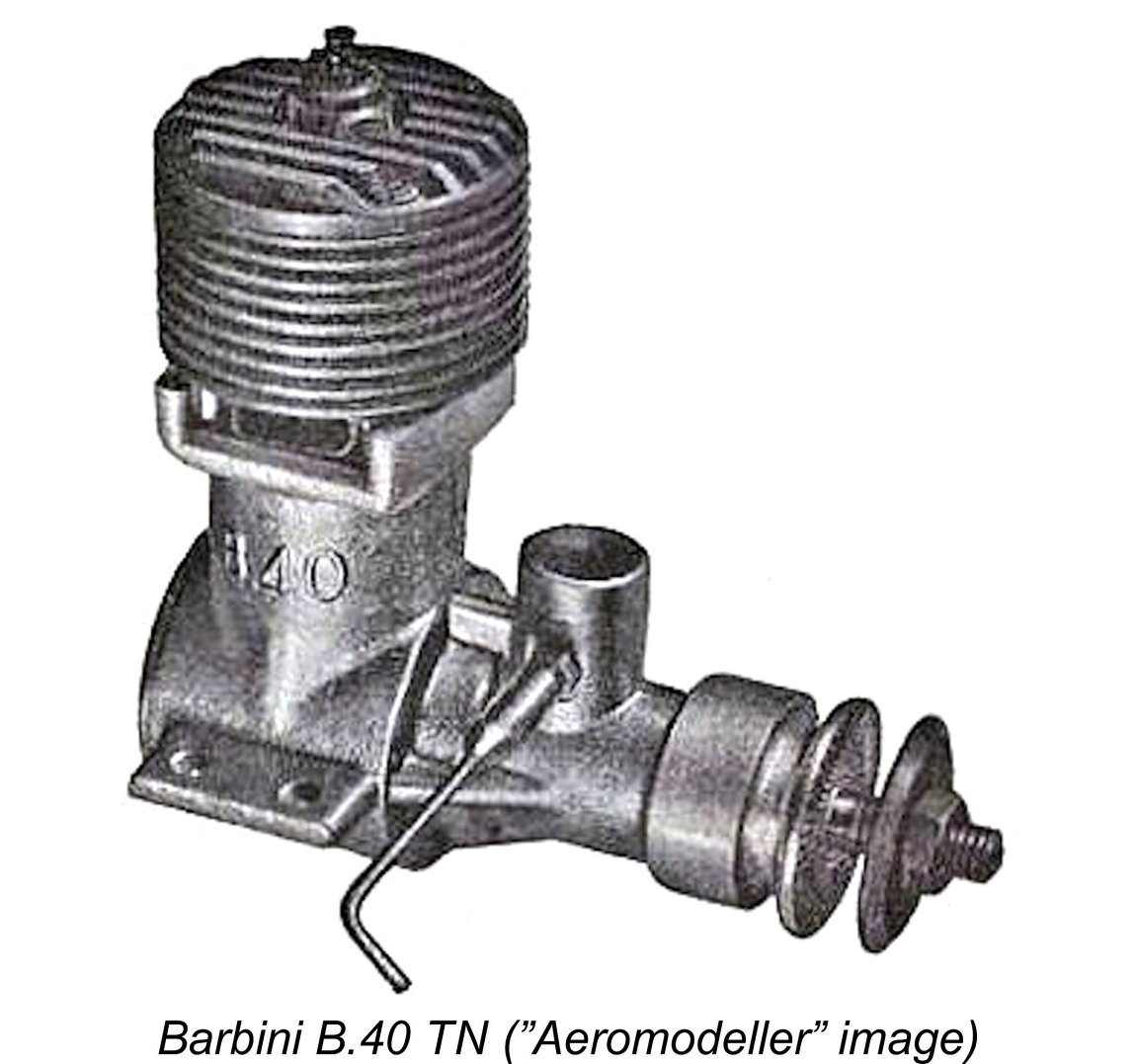

Alas for high hopes! Once again, things did not go anywhere near as well for the Super Tigre squad as they had been expecting. The Czechs and Hungarians filled the first five places with their MVVS tool-room specials and Gyula Krizsma’s lone Alag Y-03 (in fourth place), while the top “commercial” engine (if one discounts Krizsma’s Y-03 prototype) was once again the pesky Barbini B.40 TN, this time in the hands of Renzo Grandesso, who finished sixth as the highest-placed Italian team member with a very creditable speed of 206 km/hr (128 mph).

So ….. back to the drawing board and on to the next year, with hopes for better things! Garofali continued to pin his hopes upon a further refined version of the G.20 V – he clearly still believed in the design. However, by 1958 the “commercial” manufacturers were no longer getting a look in. In 1957 the Hungarian government of the day followed the lead of their Czech counterparts by establishing their own version of the MVVS institute in the form of the Modell Kisérleti Intézet (Experimental Modeling Institute) at Buadörs Airport near Budapest.

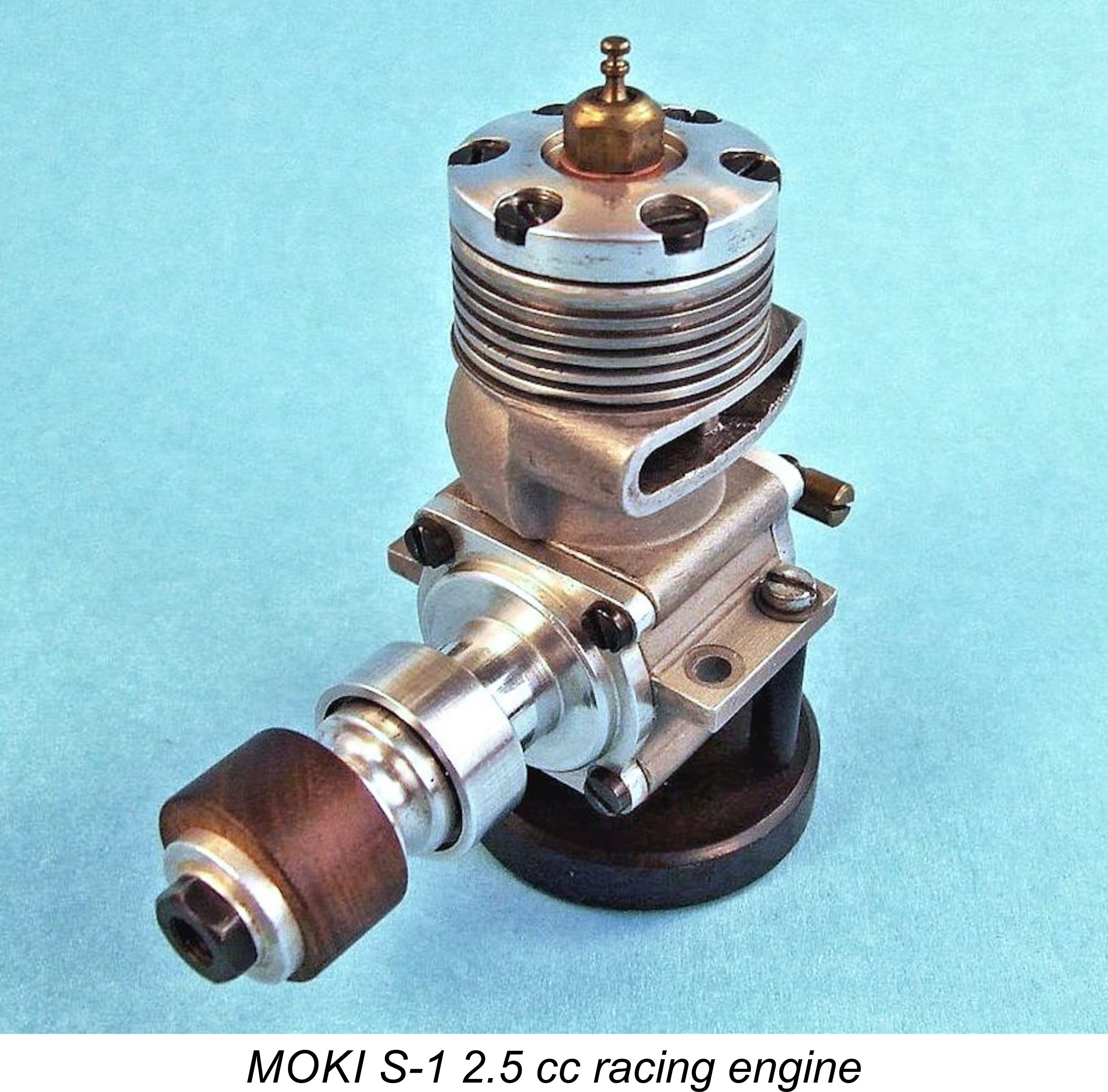

The 1958 Championship meeting at Brussels turned out to be a straight dog-fight between the MVVS and MOKI works specials from Czechoslovakia and Hungary respectively. The MOKI squad came out on top, taking the first two places, followed by three MVVS entries. This was a remarkable achievement considering that this was the MOKI S-1’s first-ever major contest. Top Italian was the sixth-placed Cesare Rossi (later of Novarossi fame), whose best Super Tigre G.20 V powered speed of 204 km/hr (126.76 mph) was no threat to Imre Toth’s MOKI-powered winning mark of 216 km/hr (134.22 mph). Indeed, it represented only a very small advance over the best speed achieved by the G.20 V at the 1957 meeting. In their desperate efforts to surmount Toth's lead, several of the Italian and Czech team members resorted to highly questionable pylon tactics, going well beyond the "standard" continental technique of having the handle held in the pylon at a 40 degree angle to the lines. The extent to which they did so went beyond the patience of the event officials, resulting in the second-round disqualifications of one member each of the Czech and Italian teams. Not only was Kočí's handle held at such an acute angle to the lines that the latter were actually brought across his right shoulder, but Cesare Rossi actually used an outrigger attached to his handle! In both cases, the result was the shortening of the effective line length, thus reducing the distance covered during the timed laps. The need for an indicator projecting from the handle to visibly line-up the flier and his model was never more obvious. This episode was to be recalled at the highly controversial 1960 event which has been discussed in depth elsewhere. At that meeting, Italy's Ugo Rossi used exactly the same tactics that had resulted in Kočí's disqualification in 1958. However, Rossi's speed obtained in this clearly illegal manner was inexplicably allowed to stand as the winning mark in 1960. It appears that the 1958 result finally convinced Garofali that for all its worthy qualities the G.20 V simply wasn’t up to the challenge of getting on top of the MOKI and MVVS specials. He thereupon threw away the design book and came up with a radical new form of cylinder porting which he subsequently patented. This incorporated a pair of directional transfer ports which directed incoming fuel mixture up into the cylinder head without the use of a baffle piston. This permitted the creation of a far more efficient combustion chamber.

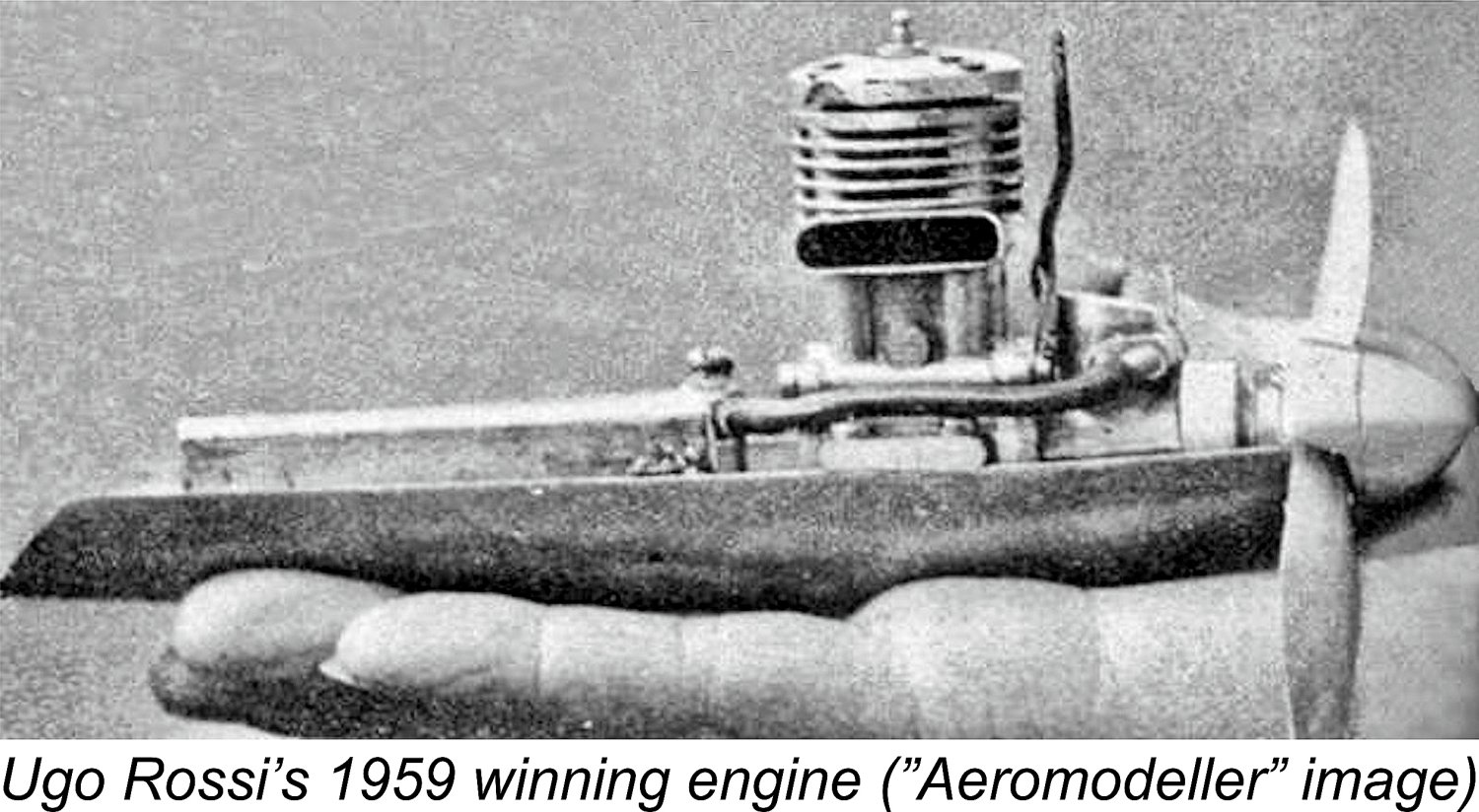

Although it was not officially accorded the title, the tenth Criterium of Aces meeting held once again at Brussels, Belgium effectively constituted the World Championship event for 1959. At this event the hybrid Super Tigre G.20 V’s finally broke through, with Ugo Rossi of Brescia winning at a much improved and very creditable speed of 222 km/hr (137.95 mph) and brother Cesare placing third at 210 km/hr (130.49 mph). Observers at the meeting noted with approval that Rossi's winning speed was achieved without a trace of whipping. It's interesting to note in passing that Rossi would almost certainly not have won this contest had it not been for the misfortune suffered by Jaures Garofali's favorite entrant, his faithful employee Amato Prati. Garofali had carefully checked all of the engines in advance, giving the best of them to Prati. Sadly, Prati suffered a broken lead-out in flight at a very early stage, causing his model to crash. This destroyed both Prati's model and Garofali's best engine, leaving the way clear for Rossi to come through to win. All such misfortunes aside, this was an outstanding result in the face of the ongoing presence of the MOKI specials, which were beaten into second and fourth places. The result was somewhat tempered by the fact that the MVVS "works team" did not contest this event, due in large part to the unfortunate A hint of the effect that the presence of an Institute-backed MVVS team might have had on the results was the 193.9 km/hr (120.5 mph) speed achieved by K. Jaaskelainen of Finland to earn 6th place using one of the early production versions of the 2.5R-58 which he had somehow acquired. A highly creditable performance for a lone individual using a self-prepared production engine without official support! Regardless, this result spelled the end of the road for the G.20 V. Greatly encouraged by the 1959 result, Garofali developed an all-new model, the Super Tigre G.20/15V "Jubilee", for 1960. With its one-piece crankcase and directional porting with flat-topped piston, this design bore only a superficial resemblance to its predecessor. The G.20 V thus became the final Super Tigre G.20 model to feature a baffle piston. Conclusion I hope that you've enjoyed this retrospective look at one of the classic 2.5 cc racing engines of the 1950's and its role in shaping the future development of the 2.5 cc Super Tigre series. Although it didn't fulfil the high hopes for success that its designer placed upon it, the engine is extremely significant in that it inspired a major turning point in Jaures Garofali's design philosophy. As such, it is well worth remembering. _________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published August 2019 |

||

| |

Continuing with my coverage of classic 2.5 cc racing engines of the 1950’s, it’s time to evaluate the second Super Tigre model to be analyzed in detail here. This time it’s the turn of the Super Tigre G.20 V which replaced its predecessor, the previously-tested

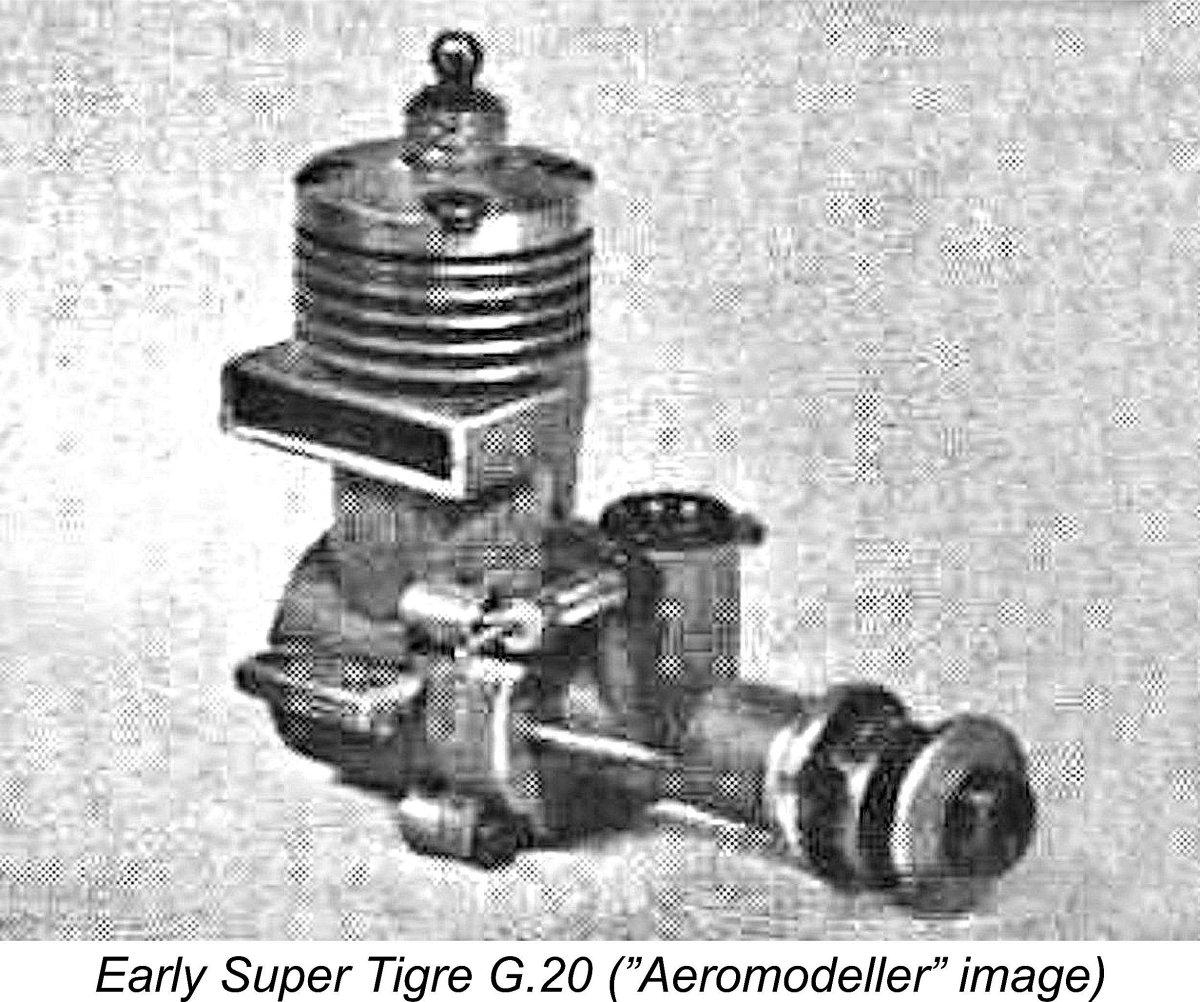

Continuing with my coverage of classic 2.5 cc racing engines of the 1950’s, it’s time to evaluate the second Super Tigre model to be analyzed in detail here. This time it’s the turn of the Super Tigre G.20 V which replaced its predecessor, the previously-tested  The original 1950 version of the G.20 featured a sandcast crankcase with a rectangular exhaust stack and an integrally-cast backplate; a bolt-on front housing with provision for FRV induction; a single inboard ball bearing on the shaft; a finless head with the plug offset towards the bypass side; and a light alloy baffle piston with two rings. Bore and stroke dimensions were 15 mm and 14 mm respectively, a combination of dimensions which was destined to become more or less a standard for Continental 2.5 cc motors. These figures yielded a displacement of 2.47 cc (0.151 cuin.).

The original 1950 version of the G.20 featured a sandcast crankcase with a rectangular exhaust stack and an integrally-cast backplate; a bolt-on front housing with provision for FRV induction; a single inboard ball bearing on the shaft; a finless head with the plug offset towards the bypass side; and a light alloy baffle piston with two rings. Bore and stroke dimensions were 15 mm and 14 mm respectively, a combination of dimensions which was destined to become more or less a standard for Continental 2.5 cc motors. These figures yielded a displacement of 2.47 cc (0.151 cuin.). The first World Control-Line Speed Championship event to be run under the new displacement rule took place on July 2

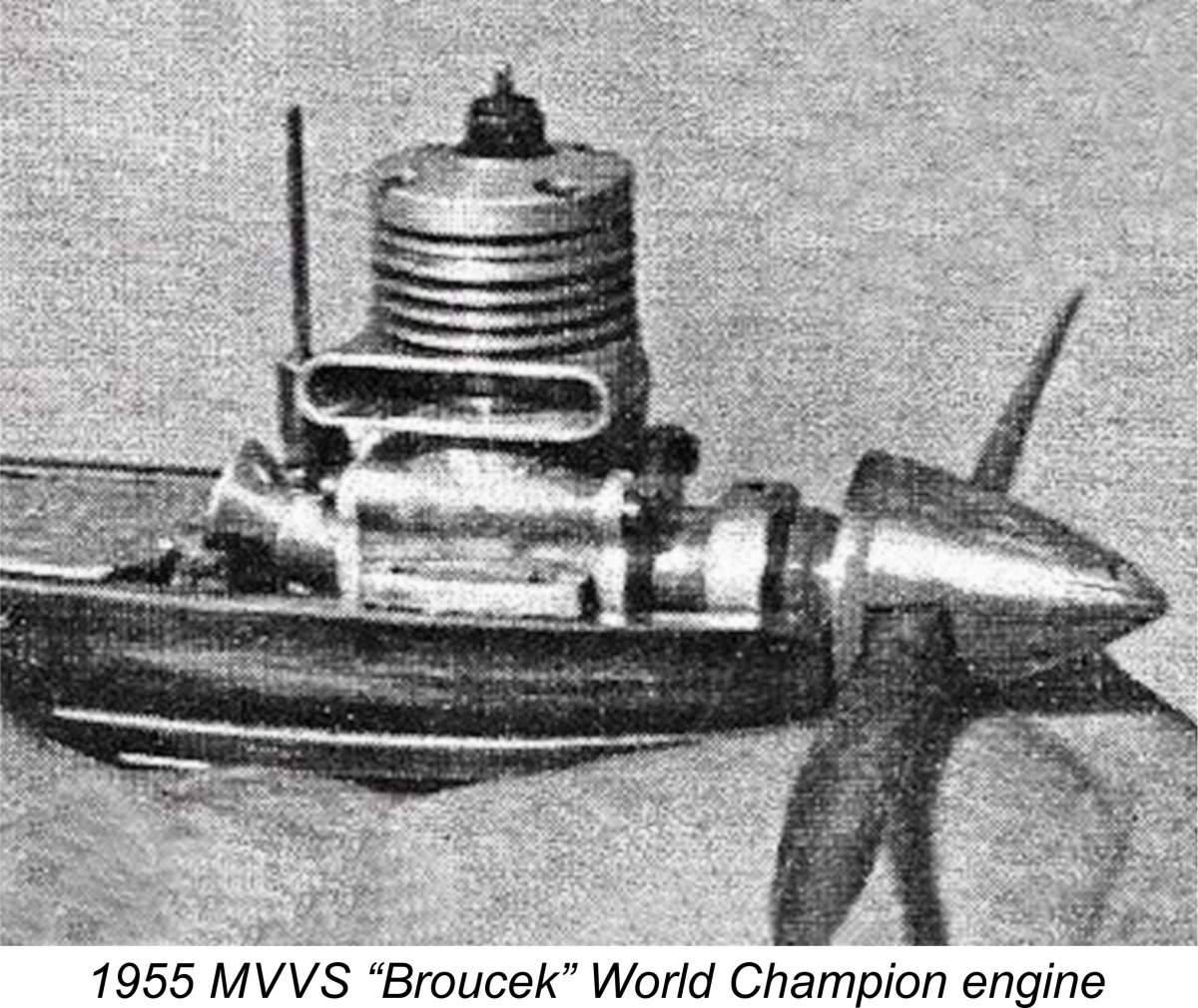

The first World Control-Line Speed Championship event to be run under the new displacement rule took place on July 2 The Czech team showed up at Paris with a number of individually-constructed 2.5 cc powerplants which had emerged from the MVVS workshops in Brno. One of these engines was the disc rear rotary valve (RRV) SK-25 “Broucek” (Poppet) prototype which had been constructed in the MVVS workshops by Josef Sladký and Luboš Kočí (hence the SK letters in the engine's name). Using this one-off unit, Sladký won the individual title with a speed of 179.11 km.hr (111.30 mph).

The Czech team showed up at Paris with a number of individually-constructed 2.5 cc powerplants which had emerged from the MVVS workshops in Brno. One of these engines was the disc rear rotary valve (RRV) SK-25 “Broucek” (Poppet) prototype which had been constructed in the MVVS workshops by Josef Sladký and Luboš Kočí (hence the SK letters in the engine's name). Using this one-off unit, Sladký won the individual title with a speed of 179.11 km.hr (111.30 mph). This being the case, there can be little doubt that Garofali placed a very high priority upon achieving success at the 1956 World Control Line Speed Championship meeting, since the event was to take place on September 29

This being the case, there can be little doubt that Garofali placed a very high priority upon achieving success at the 1956 World Control Line Speed Championship meeting, since the event was to take place on September 29 Given the attainment of such levels of performance, hopes must have run high for a good result at Florence. However, things did not go Garofali’s way at all at the meeting. Using a well-prepared but surprisingly close-to-stock Barbini B.40 TN constructed by Garofali’s rival Italian manufacturer

Given the attainment of such levels of performance, hopes must have run high for a good result at Florence. However, things did not go Garofali’s way at all at the meeting. Using a well-prepared but surprisingly close-to-stock Barbini B.40 TN constructed by Garofali’s rival Italian manufacturer  However, such considerations did nothing to assuage Garofali’s sense of frustration at being very publicly bested for a second successive year, and on his own turf at that. He clearly possessed more than his share of Italian technical competitiveness, hence being unwilling to take this lying down. Work was immediately put in hand to develop a significantly further improved version of the G.20, which appeared in 1957 as the Super Tigre G.20 V. It is this model which is the central subject of this review. The "V" in the designation of this engine reportedly stood for Super Tigre's "Victory Series" - a clear indication of expectations!

However, such considerations did nothing to assuage Garofali’s sense of frustration at being very publicly bested for a second successive year, and on his own turf at that. He clearly possessed more than his share of Italian technical competitiveness, hence being unwilling to take this lying down. Work was immediately put in hand to develop a significantly further improved version of the G.20, which appeared in 1957 as the Super Tigre G.20 V. It is this model which is the central subject of this review. The "V" in the designation of this engine reportedly stood for Super Tigre's "Victory Series" - a clear indication of expectations! For the first time since the G.20 series had been introduced, the plug was centrally located in the finned head instead of being displaced to the bypass side as in all former models. Compression ratio was unchanged at 8:1, reflecting an expectation that high-nitro fuels would be used. A revised needle valve giving more precise mixture control was incorporated as well, using an externally-threaded needle with a split internally-threaded spraybar and gland nut for tension.

For the first time since the G.20 series had been introduced, the plug was centrally located in the finned head instead of being displaced to the bypass side as in all former models. Compression ratio was unchanged at 8:1, reflecting an expectation that high-nitro fuels would be used. A revised needle valve giving more precise mixture control was incorporated as well, using an externally-threaded needle with a split internally-threaded spraybar and gland nut for tension.

As I hope I’ve just demonstrated, the performance of the new G.20 V undoubtedly gave Jaures Garofali and his colleagues every reason to expect a positive outcome at the 1957 World Control Line Speed Championship meeting held that year in MVVS’s back yard at Mlada Boleslav in Czechoslovakia. Garofali showed up at the 1957 event along with the ever-faithful Amato Prati, who had both his own G.20 V powered model and a similarly-powered model which he flew proxy for Paolo Berselli. The third member of the official Italian team was Renzo Grandesso, who chose to use the rival Italian

As I hope I’ve just demonstrated, the performance of the new G.20 V undoubtedly gave Jaures Garofali and his colleagues every reason to expect a positive outcome at the 1957 World Control Line Speed Championship meeting held that year in MVVS’s back yard at Mlada Boleslav in Czechoslovakia. Garofali showed up at the 1957 event along with the ever-faithful Amato Prati, who had both his own G.20 V powered model and a similarly-powered model which he flew proxy for Paolo Berselli. The third member of the official Italian team was Renzo Grandesso, who chose to use the rival Italian  However, this paled in comparison with the winning performance! Using a prototype of the

However, this paled in comparison with the winning performance! Using a prototype of the