|

|

Italian Anomaly - the Micromotor Delta 2 diesel

This is truly unfortunate, because Italy richly deserves to be recognized as one of the most prominent nations of them all in terms of its involvement in the early development of the model diesel. Although the principle had first been developed in pre-WW2 Switzerland, it’s clear that Italian designers were extremely quick to pick up on the concept and run with it. Even their country’s involvement in WW2 didn’t stop them. At the end of the war, they were well ahead of their counterparts in Britain, who were really just getting started. In this article, we’ll be sharing a close look at a representative example of the products of one of Italy’s earliest and largely undocumented manufacturers of model compression ignition (aka “diesel”) engines, the Micromotor company of Busto Arsizio in Northern Italy. I’ll be reviewing the Delta 2 diesel produced by that company beginning in 1946. I referred to this engine as an anomaly because it appears to have been released simultaneously by two distinct companies! More of that in due course ........... Before getting started on this review, I wish to draw attention to a source of information on Italian engines which has proved to be quite invaluable in the present instance. This is the very informative Italian Engines website, which contains a great deal of basic information on Italian model engines of the pioneering and classic eras. Much of this information can be found nowhere else. The site is presented in English, although an Italian version will appear eventually. Anyone having an interest in early Italian engines is strongly recommended to check out this outstanding resource. Now, in order to place this engine in context, it’s necessary to present a little background material. Here goes ………….. Background

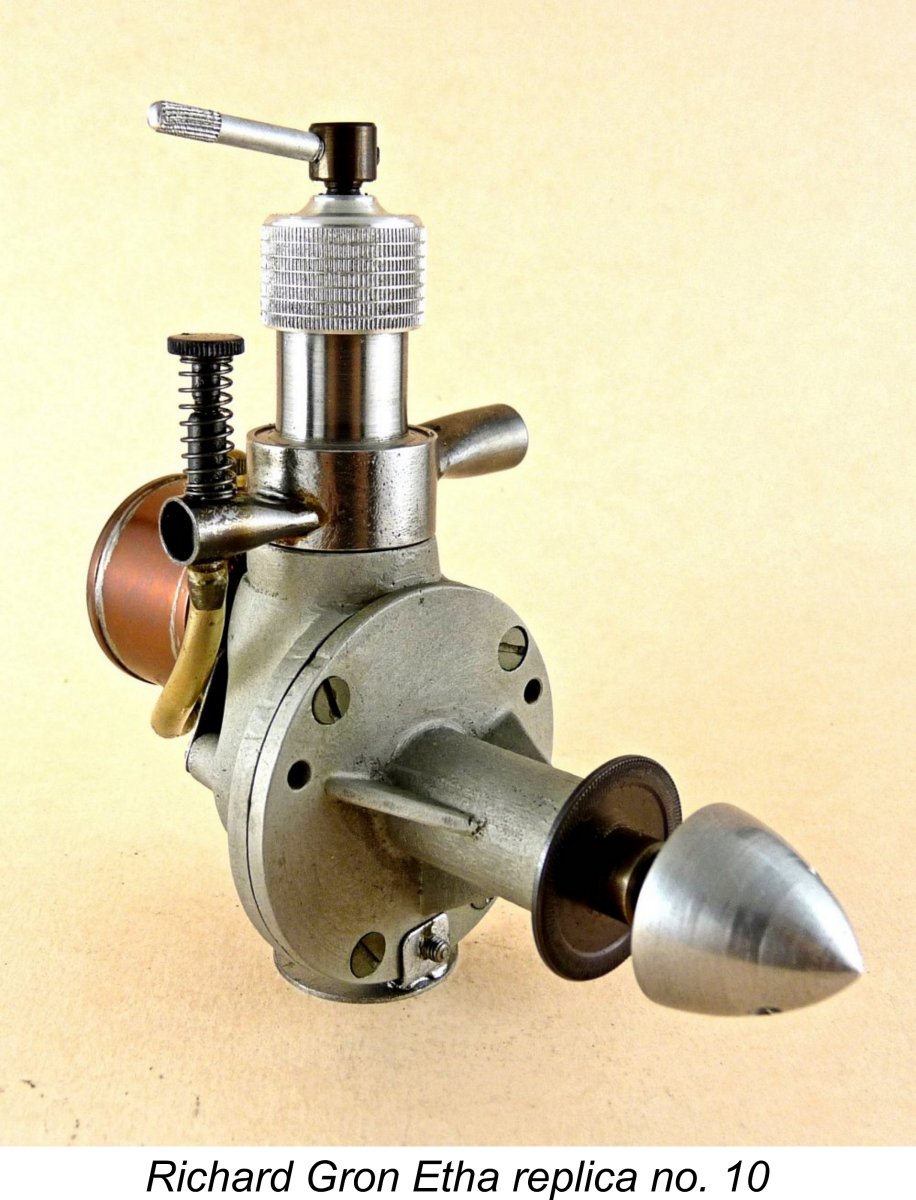

After spending the next ten years making very small numbers of such engines for his own enjoyment and that of his friends as well as some larger models to special order, Thalheim finally went into series production with a succession of model engines which were marketed from 1938 onwards under the ETHA label. The name was of course derived from Ernst THAlheim’s name rather than that of a primary ingredient of the engine’s fuel! These powerplants appear to have been the world’s first commercially-produced model diesel engines. It’s a bit of a mystery why it took Thalheim ten years to actually begin to capitalize upon his patent ……. in all probability the Great Depression which began in 1929 immediately following the issuance of the patent had something to do with it.

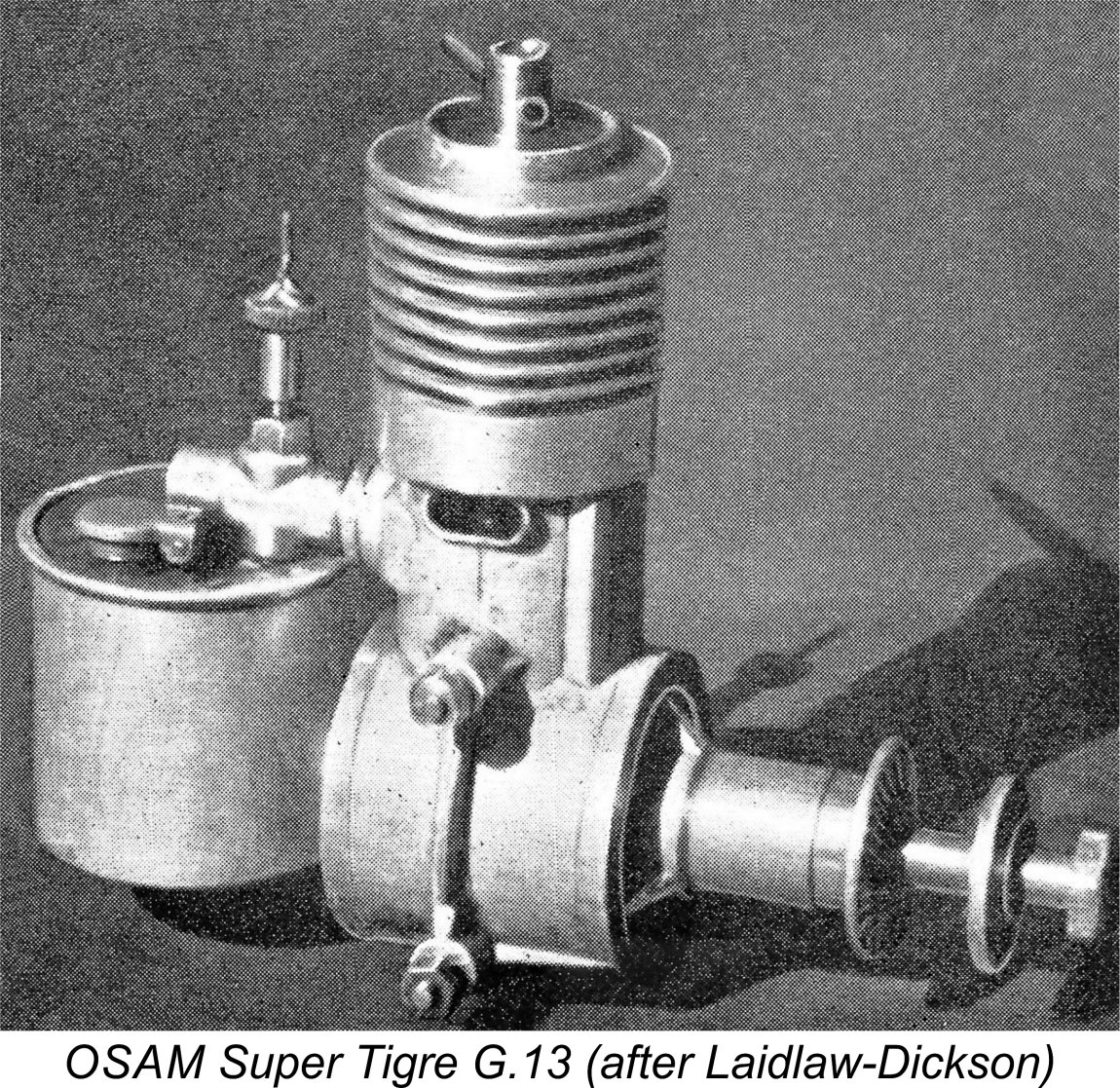

This being the case, it was inevitable that others would follow Thalheim’s lead. The previously-mentioned Dyno 2 cc model manufactured in Alfligen, Switzerland by Klemenz-Schenk (whose primary business was the manufacture of wheel-driven bicycle lighting generators, hence the engine’s name) was one of the earliest spin-off products, being developed in 1939-1940 and making its market debut in mid-1941. It was a considerable step forward from the ETHA designs, being both smaller and lighter as well as having a higher specific power output. As time went on, the Dyno became one of the most influential and widely-imitated early model diesel designs of them all. Despite the fact that by the early 1940’s most of Europe was heavily embroiled in WW2, word about this then-innovative type of model engine, along with a few examples of the Dyno, somehow trickled out of neutral Switzerland to reach a number of other European countries. Among these countries was Italy, then heavily involved in what was progressively becoming a very unpopular war for many Italian citizens. A number of Italian residents sought relief from wartime concerns by tinkering with the concept of designing and constructing model diesel engines. Italy thus became one of the first nations after Switzerland in which the development of the model diesel concept was seriously pursued. However, Italy’s entry into WW2 on June 10th, 1940 had forced a complete change in national focus, with model engine development taking a back seat for some years thereafter. The various experimenters had to restrict their efforts to such time as they were able to free up from their war-related employment. Moreover, the conflict naturally prevented any details of Italian achievements in this field from becoming widely known outside of Italy until after the war. A notable individual who became involved with model diesel development during the wartime period was Jaures Garofali, a native of Bologna. In 1937 after leaving school, the 17 year old Garofali had teamed up with his friends Valerio Ciampolini and a certain Signor Betuzzi to found a company called OSAM, which stood for Officina Sperimentale Apparecchi Motori (Aircraft and Engines Experimental Workshop). The full OSAM story may be found elsewhere on this website. Garofali identified the engines that he designed by his own initial G followed by a number representing the chronological order in which they appeared. Thus the very first Garofali-designed engine was the OSAM G.1, a 3.5 cc spark ignition engine. Only four or five of these units are known to have been built. Over the next four years or so, this was followed by 8 more spark ignition designs, the last of which was the G.9 of 1941. By that time, Italy was heavily involved in WW2 as a member of the Axis alliance. Garofali was only able to construct these engines in very small numbers during such spare time as he could squeeze out of his busy involvement with the war effort. Three further spark ignition designs were subsequently developed, but these never got beyond the paper stage. In part, this was due to a change of focus on Garofali’s part. Despite the ongoing conflict of WW2, several examples of the previously-mentioned Swiss Dyno 1 diesel somehow crossed the Swiss-Italian border to reach northern Italy in time to compete at the 1942 Italian National Championship meeting held that year at Asiago. Naturally, the appearance of these engines stimulated intense Italian interest in this then-new technology. In early 1943, one of these units came to the attention of Jaures Garofali, who was able to take a long hard look at it.

Promptly abandoning further work on the G.10, G.11 and G.12 spark ignition models, Garofali turned his full attention to the development of his first diesel, the sideport OSAM G.13 “Super Tigre” model of 5.28 cc displacement. A few examples of this engine were made before Italy’s formal surrender to the Allies on September 3rd, 1943 took Italy out of the war. This event changed Garofali’s employment situation to the point where further model engine design and construction work had to be deferred in favour of basic economic survival. Regardless, the G.13 has the honour of having almost certainly been the first model diesel to be produced commercially in Italy. Further examples were manufactured immediately following the conclusion of the war, a few of which made their way to England.

This did not take place overnight. Although Italy formally surrendered to the Allies by signing the Armistice of Cassibile on September 3rd, 1943 following the Allied invasion of Sicily, the Germans immediately responded by occupying the country and attacking Italian forces at a number of locations. The ensuing fighting was some of the most bitter of the war, with very heavy casualties on both sides. It was not until April 27th, 1945 that the City of Milan in northern Italy was finally liberated, with the Italian campaign being formally ended a few days later by the April 29th signing of the instrument of surrender by the leadership of the German Army’s Group C. However, much of Italy had ceased to be directly involved in the conflict as of the liberation of Rome by Allied forces on June 4th, 1944. Thereafter, the ongoing fighting was largely confined to the northern half of the country. This left a sizeable number of Italian citizens free to resume some of their pre-war activities. Among these were a surprising number of individuals who had ambitions to become involved in the post-war commercial manufacture of model diesel engines. Such units began to appear in small numbers even while the fighting in the north was continuing. Naturally, some of these engines ended up in the hands of Allied military personnel who eventually brought them back to their native countries following the end of the war in Europe.

Reviewing the above list, one factor that keeps coming through is the very elegant styling of most of the engines on the list. The majority of Italian designers appear to have been as much concerned with the aesthetic appeal of their designs as they were with their functional merits. This is in sharp contrast to the early British designs, many of which ran very well but were sadly lacking in the visual aesthetic department! Regardless, consideration of the above list makes it quite clear that Italy must be seen as one of the most prominent nations of them all in the early development of model diesels. Remember, all of these engines had appeared on the Italian market well before the first British commercial diesels made their debuts in mid 1946. The Micromotor Range

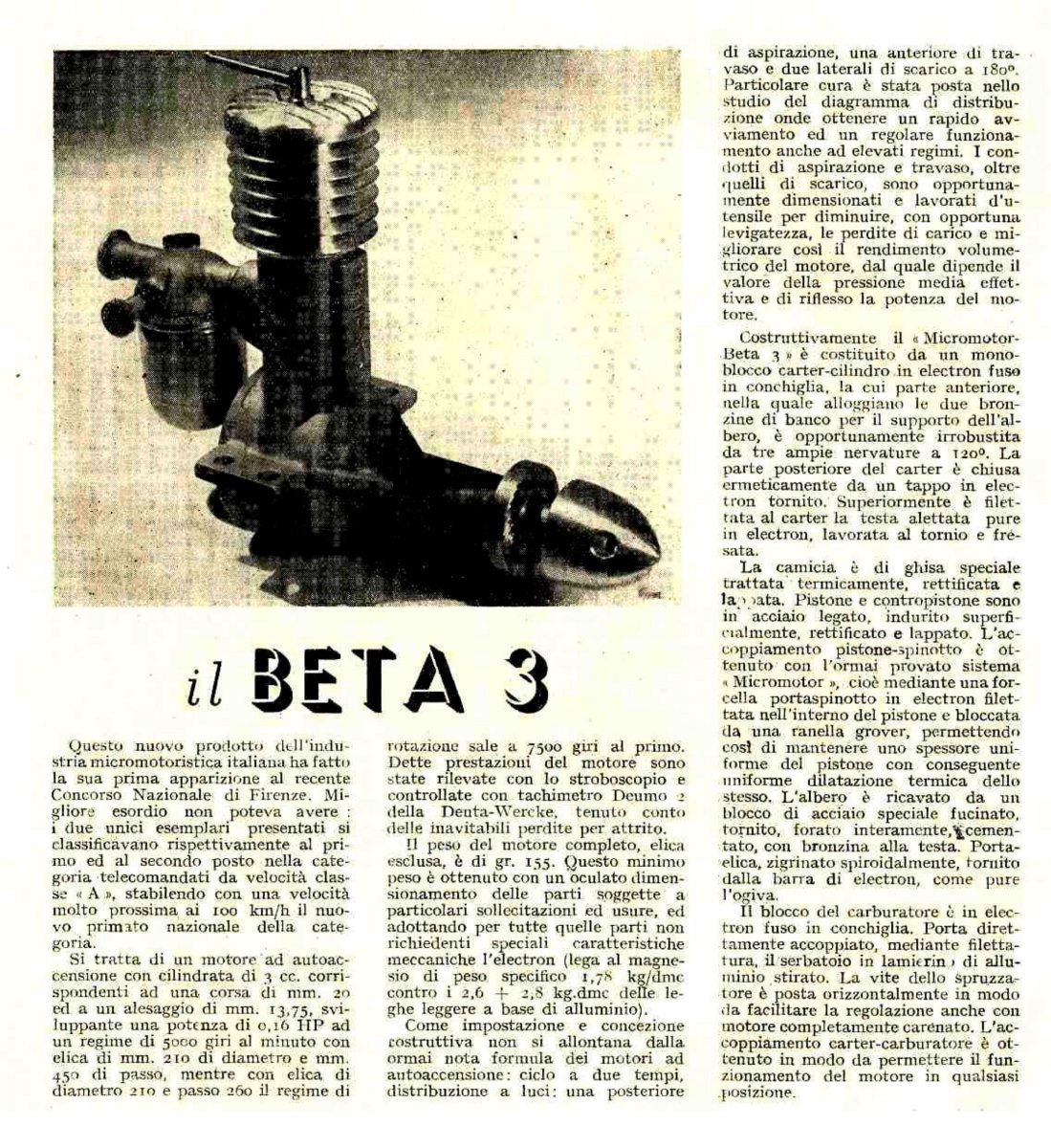

Busto Arsizio (Italian pronunciation busto arsit-sio) is a city and commune located in the Province of Varese in the Lombardy region of Northern Italy, some 34 kilometres (21 mi) north-west of Milan. The economy of Busto Arsizio has long been based mainly on industry and commerce. Today it is the fifth municipality in the region by population and the first in the Province. In contrast to Garofali’s numerical sequence, the Micromotor company adopted the somewhat unusual model identification system of applying a sequence of Greek letters to their various Micromotor engines as they appeared. Their first design appears to have been a 9.81 cc spark ignition model which was somewhat confusingly named the Alfa 1. This is not to be confused with Mancini’s previously-mentioned The Alfa 1 sparker was soon followed by the 3 cc Beta 3 diesel, which appeared in four distinct variants between 1945 and 1947. The initial release of this model appears to have attracted considerable attention. The advertising claimed that the engine had achieved a speed of 98.75 km/hr in the Class A event at an Italian Championship meeting in Florence. It would appear from this that the Italians were following the American lead by allowing engines of up to 0.199 cuin. (3.26 cc) in their Class A competitions. An output of 0.16 BHP was claimed for this model, along with an operating speed range of 5,000 - 7,500 rpm. Not too shabby for a 1945 engine of this type and displacement (assuming that it was accurate)! Weight was cited as 160 gm. The engine was the Another 9.6 cc spark ignition model soon followed, naturally enough bearing the Gamma designation (Gamma being the third letter of the Greek alphabet). Then it was the turn of the letter Delta to join the parade. This took the form of a sideport diesel of 2.0 cc displacement known as the Delta 1. This model also seems to have appeared in 1945 - either the designer was a very busy man at this time, or (more probably) he had spent the latter years of the war quietly developing his designs, delaying the commencement of actual production until the war drew to its close. I don’t have an image of the Delta 1, but it clearly differed in some respects from the Delta 2 variant which followed it. The Delta 1 had a displacement of 2.03 cc derived from bore and stroke figures of 12 mm and 18 mm respectively. The weight given in the relevant table on the Italian Engines website was 160 gm (5.64 ounces). In 1946 this model was replaced by the Delta 2 variant which is the central subject of this review. This model retained its predecessor’s stroke of 18 mm but utilized an increased bore of 12.2 mm for a slightly increased displacement of 2.10 cc. Perhaps more significantly, the weight of the engine had been substantially We’ll be taking a closer look at the Delta 2 in a following section. But before doing so, it seems worthwhile completing the tale of the Micromotor venture in general. The Delta 2 appears to have become the bread-and-butter model offered by the company, but the sequence was continued with the Epsilon Twin, a 7 cc twin-cylinder spark ignition unit which appeared in 1947. With a weight of 300 gm (10.6 ounces), this was clearly a relatively massive unit for its displacement. Unfortunately, I have no further details of what must have been a very interesting design. It appears that no further models were to appear from this manufacturer. The Delta 2 evidently remained in production for a few years, but as time went on it must have become increasingly out-dated. It would seem that as demand for the engine inevitably tapered off, the company abandoned the model engine field rather than continue with their design and development work. The date at which this occurred is now unclear. I have no information regarding the company’s later activities, if any. The FRAM Connection

The FRAM company entered the model engine market with their CA 2.5 cc diesel of 1944. Interestingly enough, this engine seemingly appeared while the city of Milan was still under German occupation. It was followed during 1945 by the Albatross 0.6 cc and CF 5 cc diesels. In 1946, FRAM introduced a 2 cc diesel which they called the Delta 2. This took place concurrently with Micromotor’s introduction of their own model by the same name. A close look at the admittedly rather poor image incorporated into the advertisement reproduced above will confirm that the FRAM Delta 2 looked This raises the strong possibility that the FRAM Delta 2 was actually constructed for them by the Micromotor company in nearby Busto Arsizio. Perhaps a few cosmetic changes were incorporated to distinguish between the two offerings. From Micomotor’s standpoint, this arrangement would be perfectly acceptable - they made money regardless of which version was sold. The other possibility is that one of the two companies purchased the rights to the design from the other. Once again, The Delta 2 was by no means FRAM’s swansong in the model engine trade. They continued in 1946 with the Eolo 5 cc diesel. Then in 1947 they came out with the 3 cc Testa Bleu (Blue Head) plain bearing sideport diesel. This was generally similar in design layout to the Micromotor Beta 3 unit, but there were enough differences to suggest that it may well have been a separate production. Of course, it could also be a close facsimile of the later 1947 version of the Beta 3, of which I do not have an image. The Testa Bleu was the subject of another very positive article in the Italian modelling media. Once again, for the convenience of my Italian readers I've attached a scan of the article. The Testa Bleu was joined in 1948 by a twin ball-race rear rotary valve 3 cc model called the Testa Rossa (Red Head), presumably of significantly higher performance. At some indeterminate date, there was also a FRAM 2.26 cc diesel called the FC2. However, I have been unable to discover anything about this model - even its date of introduction is unclear. Anyway, now that I’ve set out the somewhat ambiguous situation caused by the release of the Delta 2 by two distinct companies, we can focus from this point onwards on the Micromotor version of 1946, a fine example of which is available for inspection and test. The Micromotor Delta 2 Diesel - Description

The Micromotor Delta 2 forms an entry in the previously-cited table to be found on the Italian Engines website. From this table, we learn that the Delta 2 is a more or less conventional long-stroke sideport diesel having bore and stroke measurements of 12.2 mm and 18.0 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.10 cc (0.128 cuin.). The resulting stroke/bore ratio of 1.475 to 1 is among the highest such ratios of my personal experience, exceeded only by the Kalper and Foursome diesels from Southwick in Sussex, England. The weight of the Delta 2 model is cited as 130 gm (4.58 ounces), a figure which is precisely confirmed by the checked weight of my example. All of these figures are also confirmed by those given in D. J. Laidlaw-Dickson’s pioneering late 1946 book “Model Diesels”. Incidentally, it appears that Laidlaw-Dickson was referring to the FRAM version of the engine, since his list of Italian model engine manufacturers gives the address of the FRAM company as the manufacturers of the Delta 2. There is no mention of Micromotor. The first thing that one notices about the Delta 2 is its seeming use of magnesium alloy castings throughout. Even the prop driver and spinner are of this material, as is the main intake casting. The only exposures of any other material are the comp screw and the fuel tank!

The surfaces of the castings used in the Delta 2 seem to have been given some form of surface treatment to reduce their corrosion potential. Certainly, there is absolutely no sign of any corrosion anywhere on this 78 year old engine’s visible surfaces. I noted earlier that apart from a bore increase, the major difference between the Delta 2 and its Delta 1 predecessor is weight. The reduction in weight from 160 gm down to 130 gm must surely be due at least in part to the Delta 2’s use of magnesium castings. Presumably, those used in the Delta 1 were made from the significantly heavier aluminium alloy. In the absence of an opportunity to subject the engine to an internal examination, only a few general comments can be made here. The engine follows the classic Dyno-inspired sideport layout of an induction port at the rear, a single bypass-transfer combination at the front and a pair of exhaust ports, one on each side. As many model engine enthusiasts know, long-stroke sideport diesels are notoriously prone to pooling excess fuel in the crankcase, to the point that the engine can easily become flooded. A number of manufacturers of such engines made provision for the clearing of a flooded crankcase by incorporating a drain plug at the bottom of the engine. The Delta 2 has just such a fitting, which may be seen very clearly in the attached images.

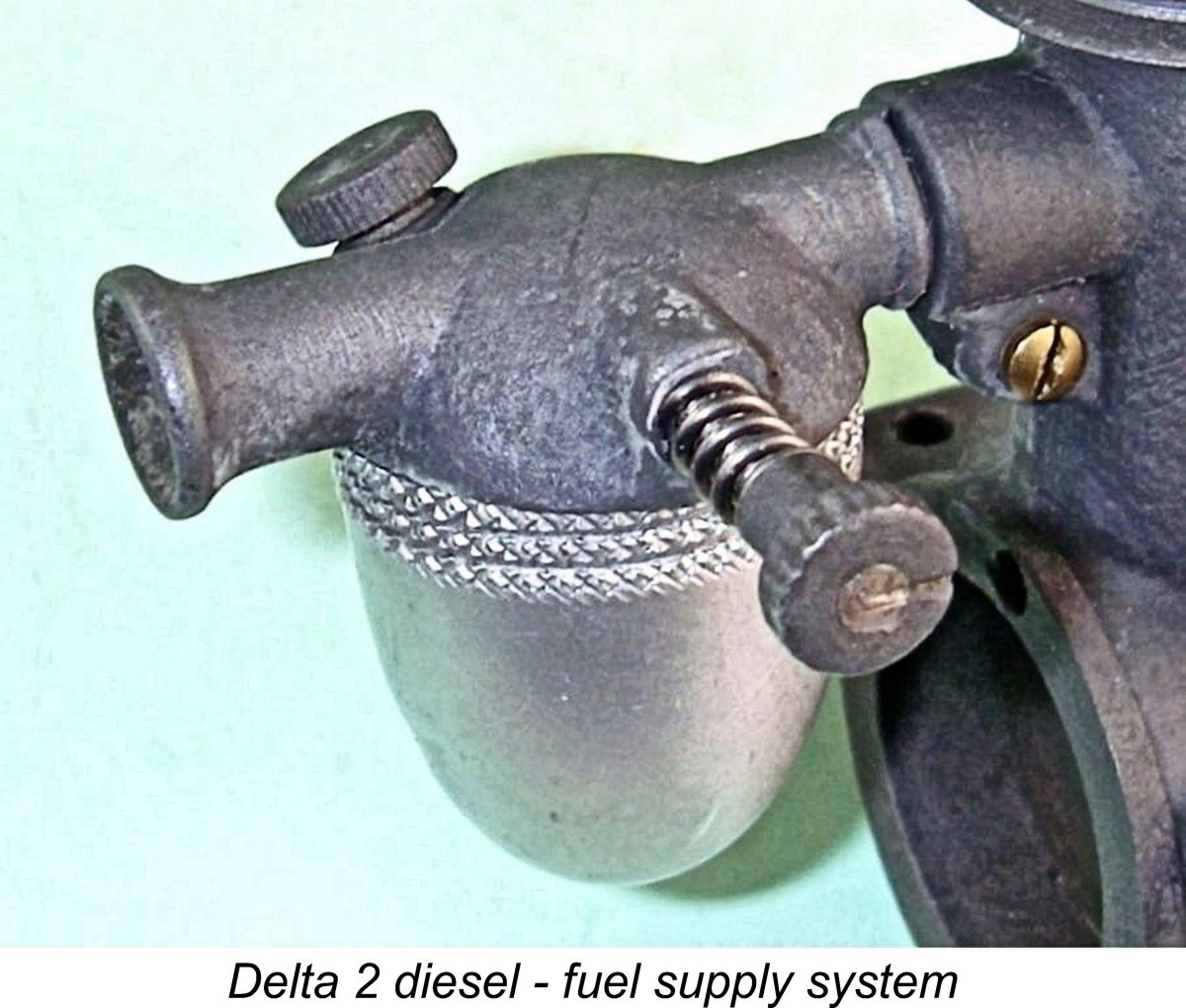

The fuel system is quite impressive in its execution. It appears to be the same unit that was used on the Beta 3 model mentioned earlier. The intake tube, tank top (with screw-in filler cap) and needle valve mount are all combined in a single casting. Since there's no spraybar, the carburettor is necessarily of the surface-jet type. The tank seems to have been spun from aluminium sheet. It threads onto the base of the tank top in the usual way.

The engines don't appear to have carried serial numbers. The only markings are stamped very neatly onto the front surfaces of the crankcase and bypass passage. The identification "MICROMOTOR - MADE IN ITALY" appears in a circular sequence surrounding the main bearing housing, while the name "DELTA" appears stamped vertically onto the bypass passage. The use of the English term "MADE IN ITALY" strongly suggests that the manufacturer had ambitions in relation to the export of the engines to English-speaking markets. However, I can find no evidence that he achieved any success in that regard. The attached images tell you as much as any words of mine about the engine’s externally-visible features. I can say nothing about the internal structure beyond making the comment that the standard of workmanship displayed in this unit is very high - certainly as good as or better than any contemporary British product. Fair enough - so we have here a very well-executed long-stroke sideport diesel of conventional design which follows the Dyno pattern fairly closely, in common with many other diesels of the period. How well does it run? Only one way to find out …………….. The Delta 2 Diesel on Test I cannot find any performance data for the Delta 2 beyond that given in Laidlaw-Dickson’s previously-cited book. Appendix I of that publication cites an operating speed of 7,000 rpm and a recommended metric propeller size of 280 x 200 mm (given by Laidlaw-Dickson as 111/8 x 8). Not very helpful, particularly since the suggested prop size appears to represent a greatly excessive load for an early 2 cc sideport diesel. A typical engine of that type and displacement would be brought to its knees by such a prop. I know of no 2 cc sideport diesel of the 1940's that could turn an 11x8 prop at 7,000 rpm or anywhere near it! The first challenge imposed by a desire to test the Delta 2 is that of finding a suite of suitable test props. Like many other European engines, the Delta suffers from the difficulty of having a 10 mm diameter prop mounting hub at the front of the prop driver. Since my standard set of calibrated test props is all drilled out to 3/8 in. (9.52 mm - I use sleeves to accommodate smaller hub sizes), they won't fit. I was not prepared to modify the engine in any way, nor did I wish to modify my usual calibrated set just for this one test. Instead, I scrounged among my extensive collection of props to find some suitable sizes that were already drilled out to test other engines in the past. The calibration figures for these props are perhaps a little on the "approximate" side, but they're certainly close enough to provide some pretty good indications. In Appendix II of Laidlaw-Dickson’s book, the manufacturer’s recommended fuel mixture is given as 40% ether, 45% naphthalene and 15% lubricating oil. Nowhere near enough oil to keep me happy! I decided to stick with my usual “early sideport” blend of 35% either, 35% kerosene and 30% castor oil, with a small addition of ignition improver. Almost any early sideport diesel will work OK on such a brew.

Since this example appears to be virtually unused (certainly unmounted), I elected to treat it as a new engine by giving it some break-in runs before commencing the actual testing. I also elected to use a conventional steel propnut and washer for the test runs in order to minimize wear on the magnesium alloy spinner nut as a result of the many prop changes required. This is a sound approach for any engine which uses an alloy spinner nut. The magnesium alloy component was only installed for the operating photographs. Finally, I dispensed with the screw-in tank filler cap for this test session. Apart from the hassle of unscrewing and refitting it between runs, there was also the possibility of somehow losing it during the session. Best to take no chances .......... In common with many early long-stroke sideport diesels, the Delta 2 displayed a marked tendency towards flooding at the slightest provocation. Such engines tend to pool excess fuel in the crankcase. When a firing burst is obtained, any pooled fuel gets thrown up into the cylinder en masse to put the engine into oscillating mode or flood it to a halt. Once flooded, it takes some effort to get the crankcase cleared sufficiently for a start to be achieved - I know, because I had to do this several times! The drain plug at the bottom of the crankcase would really earn its keep in such a situation, but it was inaccessible with the engine mounted in the test stand.

Once running, the needle was found to be unusually sensitive, with a very small fraction of a turn making a significant difference to the running. It was necessary to exercise great care in tuning the needle for best performance. However, once the setting was established, the engine held that setting very securely throughout the run, with no tendency to "hunt". The compression control was far less sensitive, making the establishment of that setting perfectly straightforward. The comp screw held its settings perfectly at all times, while the contra piston showed no tendency to seize in the bore as the cylinder became hot. Once set, running was extremely smooth and consistent - the engine ran the tank out very cleanly indeed. There was some vibration, particularly at the higher speeds, but not to a degree that I would consider objectionable. In fact, the engine vibrated less than I had been expecting, considering its rather long stroke. It must be quite well balanced internally. The main fly in the ointment was the fact that the engine simply didn't develop a lot of power! The following data tell the story.

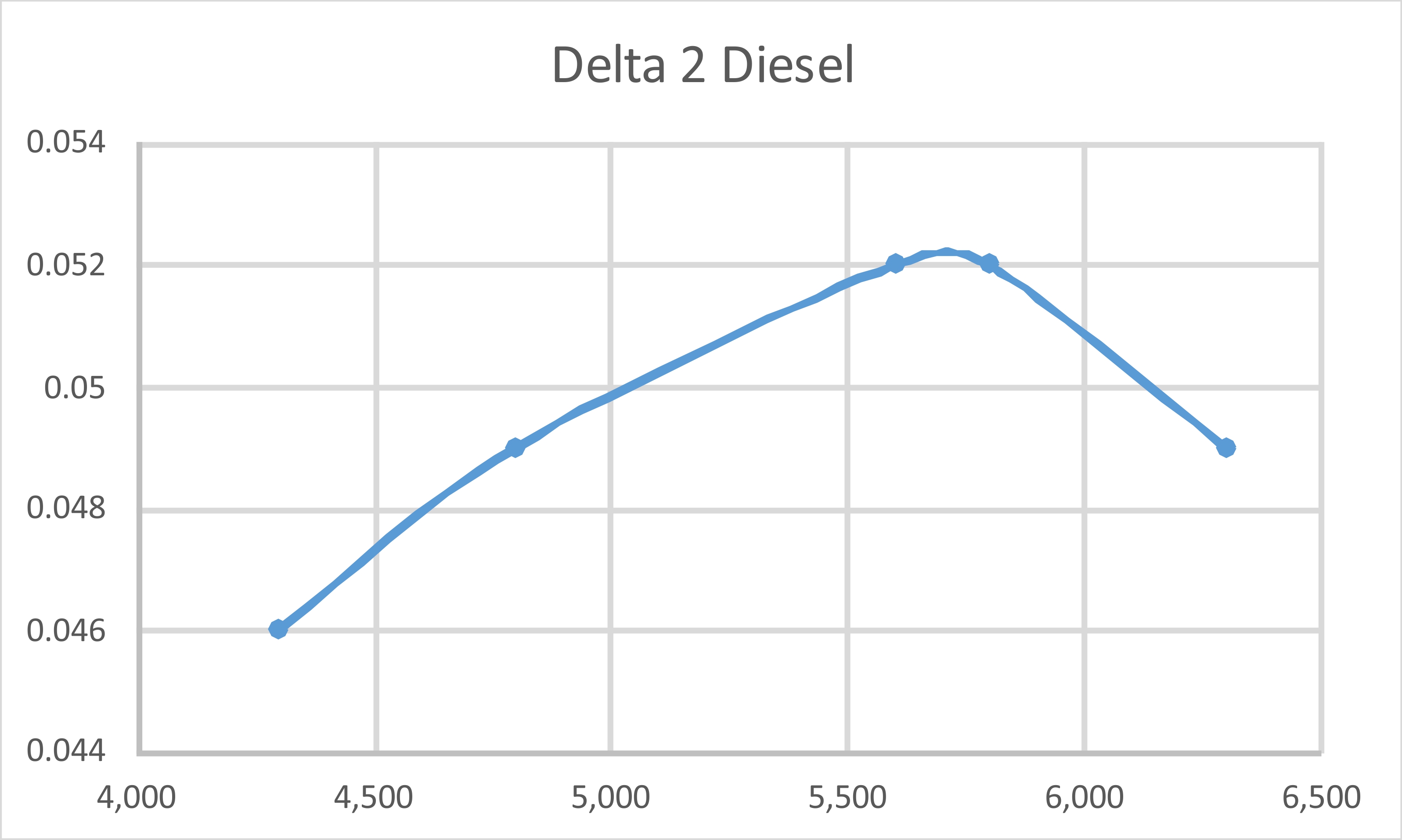

As can be seen, the engine was found to develop around 0.0521 BHP @ 5,700 rpm. Interestingly enough, this figure is almost identical to that derived from a test of the MOVO D-2 from nearby Milan which took place at the same testing session using the same fuel - indeed, the rpm figures for those props which were tested on both engines were virtually identical. It can be accurately stated that the Delta 2 performs at exactly the same level as its contemporary Milanese rival. Even the handling characteristics are pretty much directly comparable. Of course, this is by no means a stellar performance for a 2 cc diesel. However, we must remember that the engine dates from 1946, before any British commercial diesel had made its appearance. Viewed in that context, as of 1946 the Delta 2 would undoubtedly have been seen as a perfectly satisfactory performer for use in a sport free-flight model. A 10x5 prop would probably be a very good size to use for that purpose. The engine's low output would be far more of a limitation in a control-line context. The Delta 2 came through its fairly extended test period with flying colours. No mechanical difficulties of any kind were experienced, nor did any evidence of undue wear develop. The engine appears well able to give long and dependable service to any owner. Conclusion If the test example of the Delta 2 may be considered as being representative of its manufacturer's capabilities, it becomes clear that we're speaking here about a quality model engine producer. If all Micromotor products were this good by the standards of their dates of release, any of them would have been viewed as very useful model engines indeed. It's a bit of a puzzle why the Micromotor company seems to have failed to follow its Milanese neigbours from MOVO in making inroads into the international market. Examples of the Micromotor range appear to be very scarce indeed outside of Italy - the test engine is the first such unit that I've ever seen in the metal. I thoroughly enjoyed the experience of getting to know this engine, and I can certainly suggest that any model diesel enthusiast having the chance to acquire a member of the Micromotor range should give serious consideration to doing so - you'll be getting a quality product!! ______________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2022

|

||

| |

Apart from the major classic Italian ranges like

Apart from the major classic Italian ranges like  The concept of the model compression ignition engine (aka somewhat incorrectly “diesel”) goes back way further than many of today’s model engine enthusiasts seem to realize. In the past, it was often claimed that the 2 cc Swiss Dyno 1 model of 1941 was the “first” commercial model diesel. While that may be true in terms of widespread acceptance and design influence, it’s now well recognised that the concept actually dates back to December 17

The concept of the model compression ignition engine (aka somewhat incorrectly “diesel”) goes back way further than many of today’s model engine enthusiasts seem to realize. In the past, it was often claimed that the 2 cc Swiss Dyno 1 model of 1941 was the “first” commercial model diesel. While that may be true in terms of widespread acceptance and design influence, it’s now well recognised that the concept actually dates back to December 17 The ETHA engines were bulky, heavy and cumbersome. However, they were reportedly very competently constructed and evidently ran well, thus proving the concept for all to see. A test report by Maris Dislers on an accurate replica of the

The ETHA engines were bulky, heavy and cumbersome. However, they were reportedly very competently constructed and evidently ran well, thus proving the concept for all to see. A test report by Maris Dislers on an accurate replica of the  Although all of Garofali’s model engine design experience up to this point had been with spark ignition motors, he was immediately intrigued by the compression ignition concept, instantly recognizing its advantages in terms of dispensing with the parasitic weight of the sparker's ignition support system as well as its inherently superior reliability given the virtual absence of anything to go wrong. Garofali was sufficiently intrigued by his examination of the Dyno to begin immediately to explore the compression ignition concept for himself.

Although all of Garofali’s model engine design experience up to this point had been with spark ignition motors, he was immediately intrigued by the compression ignition concept, instantly recognizing its advantages in terms of dispensing with the parasitic weight of the sparker's ignition support system as well as its inherently superior reliability given the virtual absence of anything to go wrong. Garofali was sufficiently intrigued by his examination of the Dyno to begin immediately to explore the compression ignition concept for himself.  Of course, Garofali was by no means the only Italian resident to be taking an interest in model diesel development at this time - the circulating examples of the Dyno 1 saw to that. However, it was clear that any large-scale commercial ventures involving such products would have to wait until Italy was finally liberated from Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime and forced out of the war.

Of course, Garofali was by no means the only Italian resident to be taking an interest in model diesel development at this time - the circulating examples of the Dyno 1 saw to that. However, it was clear that any large-scale commercial ventures involving such products would have to wait until Italy was finally liberated from Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime and forced out of the war.  Among these early Italian diesels were the Antares 4 cc design from Padova; the Atomatic 1 cc and 4 cc models from Rome, developed by Uberto Travagli; the 2 cc P.O. 2 diesel from Bergamo; the Giglio 2 cc model from Florence, developed by Signor Grazzini; the

Among these early Italian diesels were the Antares 4 cc design from Padova; the Atomatic 1 cc and 4 cc models from Rome, developed by Uberto Travagli; the 2 cc P.O. 2 diesel from Bergamo; the Giglio 2 cc model from Florence, developed by Signor Grazzini; the  Another individual who became involved with model diesels during this early period was an unknown resident of the Northern Italian community of Busto Arsizio. I’ve been unable to learn anything at all about this individual - all that we know for sure is that he applied the trade-name Micromotor to all of his products.

Another individual who became involved with model diesels during this early period was an unknown resident of the Northern Italian community of Busto Arsizio. I’ve been unable to learn anything at all about this individual - all that we know for sure is that he applied the trade-name Micromotor to all of his products.

In considering the Delta 2 diesel, there’s a bit of a mystery surrounding the appearance of a virtually identical model of the same name which was marketed by a company called FRAM. This business was located at 60 Via Carlo Farini in Milan. The motto of the business was “Tutto per L’Aeromodellismo” (Everything for Aeromodelling), implying a far broader range of involvement with the model trade than engine production alone. It’s quite possible that this was a hobby shop as opposed to a model engine manufacturer per se.

In considering the Delta 2 diesel, there’s a bit of a mystery surrounding the appearance of a virtually identical model of the same name which was marketed by a company called FRAM. This business was located at 60 Via Carlo Farini in Milan. The motto of the business was “Tutto per L’Aeromodellismo” (Everything for Aeromodelling), implying a far broader range of involvement with the model trade than engine production alone. It’s quite possible that this was a hobby shop as opposed to a model engine manufacturer per se.

I may as well begin by stating that the following comments are based solely upon an external inspection of my own example of the engine, coupled with what little information is available from other sources. The seeming rarity of the Delta 2 outside Italy combined with the near-mint condition of this example have convinced me that it would be irresponsible to dismantle it unnecessarily. With this limitation in mind, I’ll do the best that I can.

I may as well begin by stating that the following comments are based solely upon an external inspection of my own example of the engine, coupled with what little information is available from other sources. The seeming rarity of the Delta 2 outside Italy combined with the near-mint condition of this example have convinced me that it would be irresponsible to dismantle it unnecessarily. With this limitation in mind, I’ll do the best that I can.  As every classic model engine enthusiast knows, magnesium has an incorrigible tendency to want to return to the ocean from whence it came! The fight against corrosion with such engines is an ongoing battle from which there is generally no let-up. An article setting out the associated challenges for owners may be found

As every classic model engine enthusiast knows, magnesium has an incorrigible tendency to want to return to the ocean from whence it came! The fight against corrosion with such engines is an ongoing battle from which there is generally no let-up. An article setting out the associated challenges for owners may be found

I fitted a 10x7 Top Flite wood prop and was all set. Once mounted in the test stand, the Delta 2 felt just great - very smooth when turned over, but with an excellent compression seal. Base compression too was extremely good - the engine "popped" healthily through the transfer port when turned over slowly. I anticipated no trouble in getting it going.

I fitted a 10x7 Top Flite wood prop and was all set. Once mounted in the test stand, the Delta 2 felt just great - very smooth when turned over, but with an excellent compression seal. Base compression too was extremely good - the engine "popped" healthily through the transfer port when turned over slowly. I anticipated no trouble in getting it going.  The best approach was found to be to administer no more than one or two choked flicks, followed by a "dry" exhaust prime (administered with the exhaust ports closed). This was effective in minimizing the engine's tendency to pool fuel in the crankcase, although even then the engine tended to start on the rich side, taking a few seconds to clear its throat and pick up speed. Still, it proved to be a relatively easy starter once the appropriate procedure had been adopted.

The best approach was found to be to administer no more than one or two choked flicks, followed by a "dry" exhaust prime (administered with the exhaust ports closed). This was effective in minimizing the engine's tendency to pool fuel in the crankcase, although even then the engine tended to start on the rich side, taking a few seconds to clear its throat and pick up speed. Still, it proved to be a relatively easy starter once the appropriate procedure had been adopted.