|

|

A Reclusive Oriental Range - the Boxer Engines I’ve commented previously on the various factors which guide my choice of subjects for these articles of mine on classic model aero engines. I’ve noted that the rarity of a given engine is not a primary factor in those choices. Engine designs which display a higher-than-usual degree of technical interest certainly command my attention, and many such engines do happen to be quite rare. However, the most important engines to cover are those which remain in relatively wide circulation, since such engines may well be of direct interest to many of my readers who may own them or may reasonably aspire to do so.

The main subject of the present article, the Boxer range, falls squarely into the latter category. This range is so little known outside its south-east Asian area of origin that many long-term collectors worldwide appear never to have heard of it! Even in Japan, where the engines undoubtedly were marketed, examples are reportedly very few and far between. My original article on the Boxer engines was published in September 2010 on the late Ron Chernich’s “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. I’m re-publishing it here partially to prevent its loss as Ron’s now-frozen and administratively-inaccessible site steadily deteriorates due to lack of any opportunity to maintain it, but also to permit the addition of some further information which has since come to light. Some may still wonder why I bother to publish information on such an obscure model engine range about which so little definite information is available. My answer is that if I don't do so, who will? At least this article will make people aware of the existence of the Boxer engines, which in itself will be a step forward. The alternative is to say nothing, thereby consigning the Boxer range to eventual oblivion. A small piece of model engine history would thereby be lost forever. Moreover, the raising of awareness of these engines may The Boxer engines appeared on the Asian market for a relatively brief period during the decade following the conclusion of WW2. At the time in question, Japanese modelling activities, including model engine production and marketing, went almost completely un-reported in the English-language modelling media. At present, I don’t even have any definite information on where the Boxer engines were produced or when production commenced and ended. Accordingly, the best that I'll be able to do here is describe the engines on the basis of several examples in my possession, test them on the bench and offer some highly tentative deductions regarding their origins. I wish to stress that many of the conclusions presented herein should be regarded as conjectural at best, hence requiring further corroboration before being accepted as fact. In order to draw some tentative conclusions regarding the production history of the Boxer engines, it’s essential to understand something of the context in which they appeared on the Japanese market. Accordingly, I’ll begin by presenting a brief summary of the Japanese post-war model engine production scene for those readers who are unfamiliar with this topic. Before getting started, I'd like to acknowledge the considerable support and assistance rendered to me by Alan Strutt of England. Not only did Alan make available the complete example of the Boxer 29 which appears in this article, but he also read the original text in draft form and offered many valuable suggestions. We didn't agree on all points of interpretation, so I must stress that I accept full responsibility for the following text, including any errors or omissions. However, Alan's comments added much to the context within which my own tentative conclusions are drawn. OK, on with the story as I see it... Context

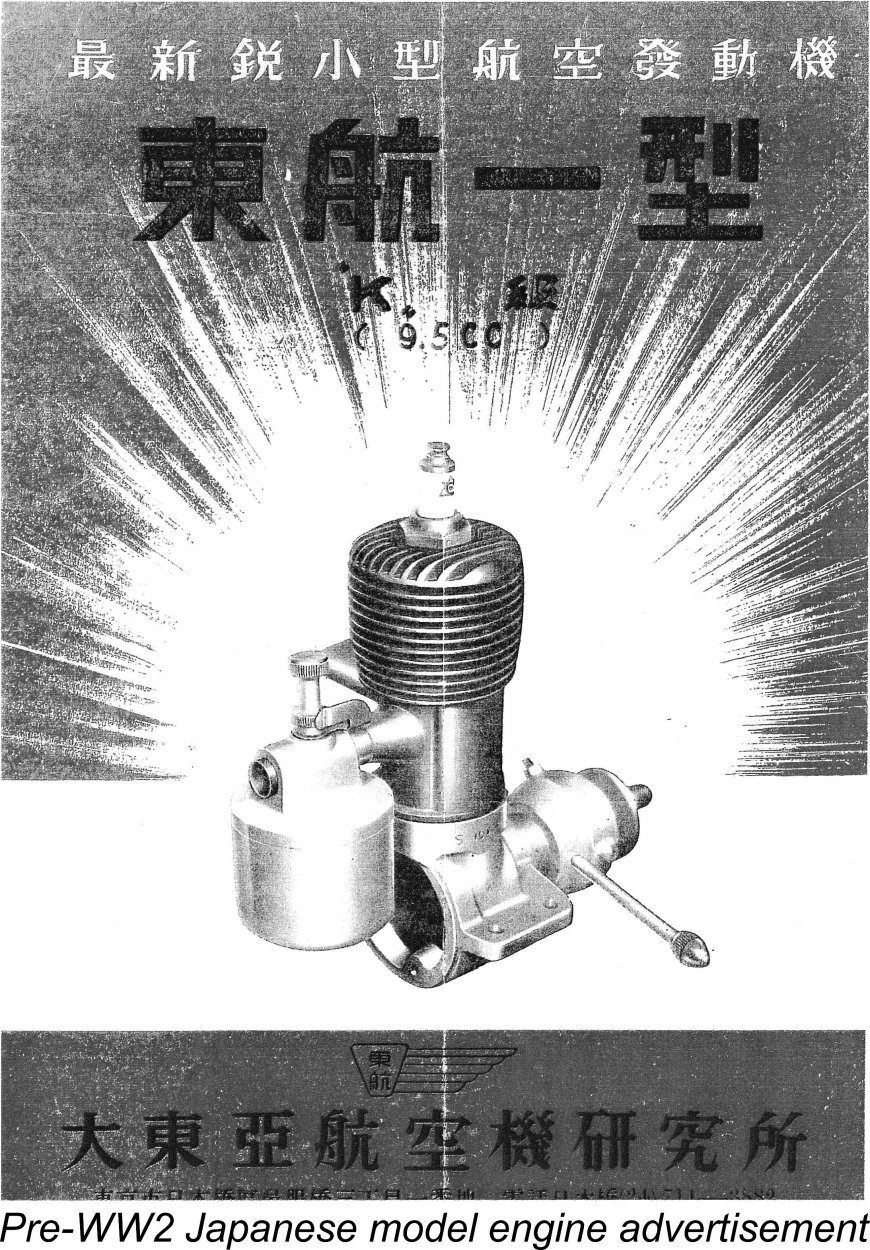

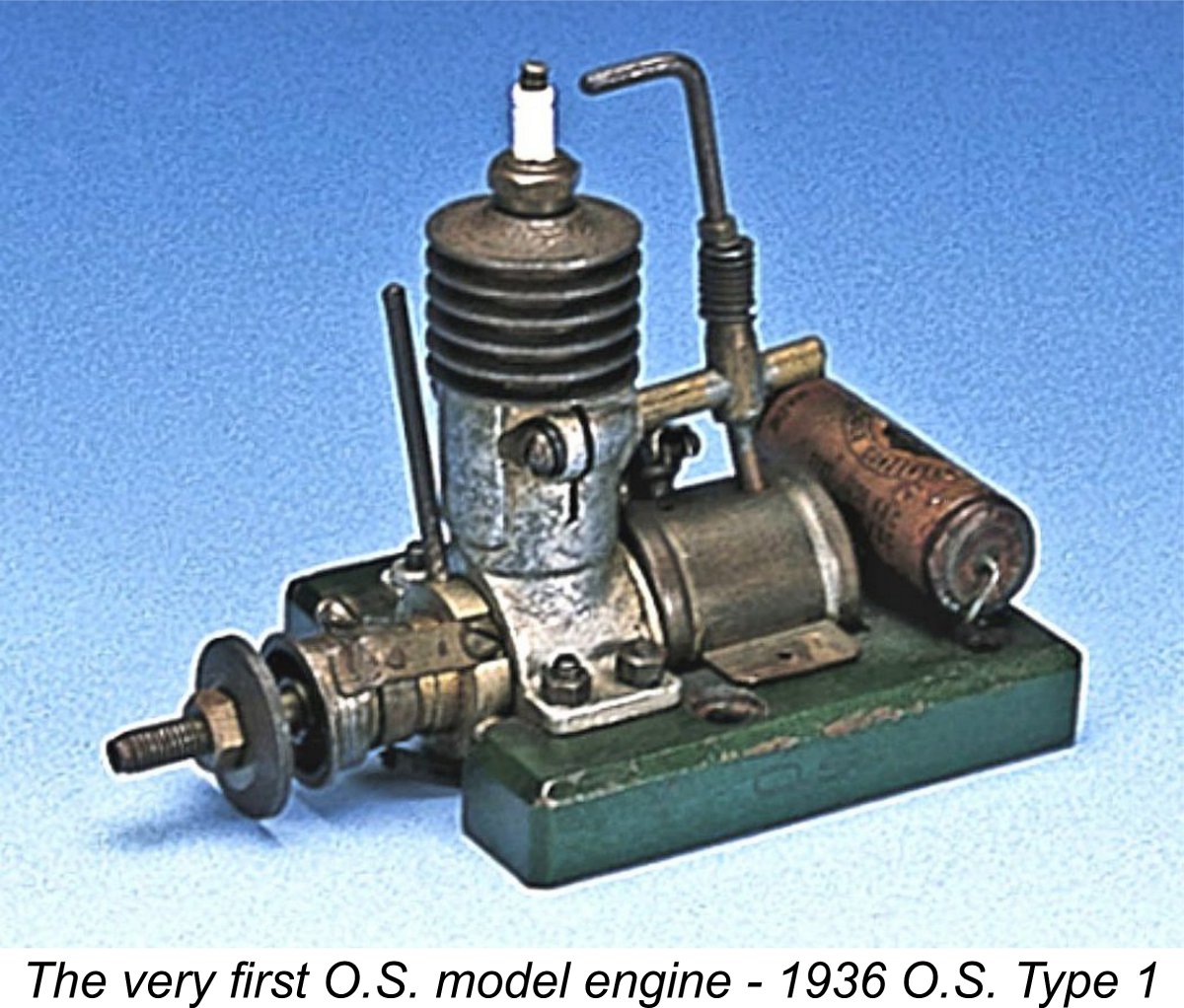

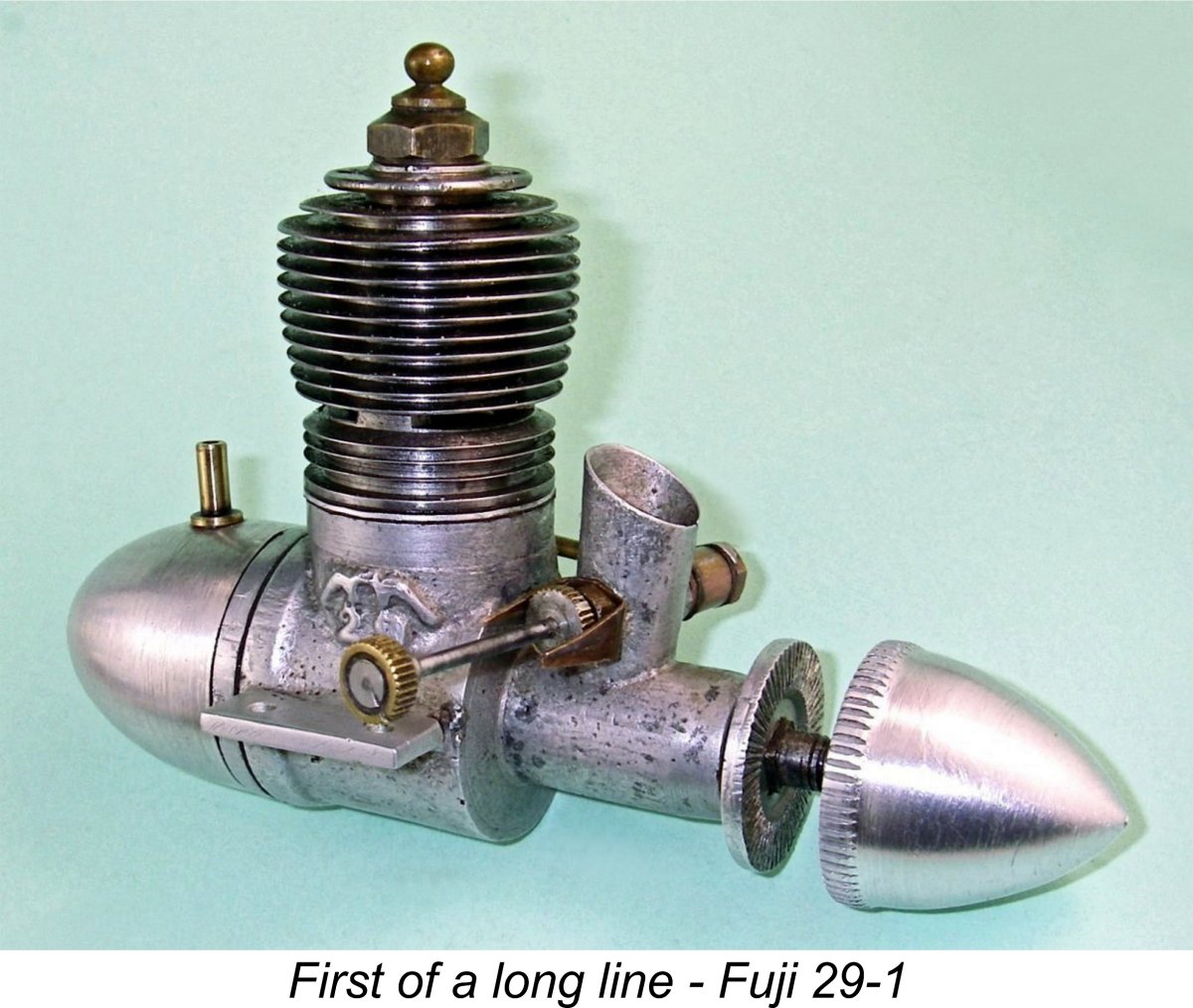

This re-awakening extended into all facets of the Japanese economy, including the field of model engine manufacture. It's vitally important to understand at this point that this was in every sense a re-awakening - unknown to most Western modellers, a thriving power-modelling scene had existed in Japan prior to WW2, albeit largely restricted to those in the upper economic strata of Japanese society. In response to the consequent pre-war domestic demand, a number of commercially-produced Japanese model engine ranges had appeared in the 1930's, mirroring the pattern established in America and elsewhere. Most notable among these was the Osaka-based O.S. marque which had become well-established in Japan following its initial market entry in 1936 and had even succeeded in penetrating the pre-war US market to a small extent. But O.S. was far from being alone - there were quite a few other pre-war Japanese makers, most of whom are now largely forgotten. An article which was published in the July 1946 issue of "Air Trails" shed a great deal of light on this period. This article was written by Frank Nekimken, an American military troop carrier pilot who arrived in Japan with US forces a few days after VJ Day (September 2nd, 1945). My very sincere thanks go to my Aussie mate Gordon Beeby for drawing my attention to this important text. The article included the substance of an interview with Mr. K. Shimozin, owner of Tokyo's largest model shop (which had somehow resumed business following the wartime bombing) and then-President of the Japanese Model Industry Association. Apart from his retail activities, Mr. Shimozin had been a major kit manufacturer for some thirty-four years at the time of the interview (1946). Before the B-29's wiped out his factory, he had been Japan's largest kit producer, employing 12 men who produced approximately 12,000 kits per month. This included both flying and static models.

Mr. Shimozin reported that there had been as many as three hundred kit manufacturers in Japan prior to the war. Their products were marketed through some seventy wholesale jobbers and 600 retail outlets nationwide. Clearly a thriving industry! The article pointed out that the building and flying of kites and model aircraft had been part of every child's education both before and during the war. Aircraft recognition had been an integral part of the wartime school curriculum. As a result, Nekimken went so far as to state his view that there were almost certainly more model airplane builders in Japan than there were in the USA despite the discrepancies in terms of population! Of particular relevance to the present discussion, Mr. Shimozin advised that some ten percent of pre-war Japanese aeromodellers were involved with power modelling. This level of interest supported the activities of as many as 10 pre-war model engine manufacturers, who produced around 500 engines monthly between them. The most notable of these was the previously-cited O.S. marque, but O.S. was far from being alone - Mr. Shimozin confirmed that there were quite a few other pre-war Japanese makers. This situation has always been greatly under-appreciated in Western modelling circles because the pre-war Japanese power-modelling scene had been completely invisible to the non-Japanese speaking world due to language and political differences. But the fact is that many of those who became involved with model engine manufacture in Japan after the war actually had considerable prior experience in the model engine field. This was far from being merely a group of talented but inexperienced imitators who were learning on the job, as is often assumed - in fact, we're speaking here of a number of experienced power modellers resuming an activity that they already understood very well indeed. Immediately following the 1945 conclusion of the war, all Japanese aeromodelling activity was stopped by the occupation authorities. However, a 1946 appeal to the American occupation leadership by a famed Japanese writer and keen model aircraft enthusiast named Komatsu Kitamura was successful in lifting the ban. The first Japanese-American model club was established later in that year by an American GI, and the hobby immediately took flight once more.

At some point during this very dynamic period, the Boxer engines also made their appearance on the Japanese market. I may as well be honest from the outset and admit that at present I’m unable to state with absolute certainty that the Boxer engines were actually made in Japan! They were certainly marketed there, but that does not of itself prove a Japanese origin. However, such limited evidence as I’ve been able to find, including anecdotal information from latter-day Japanese sources, suggests to me that it's far more likely than not that the Boxer engines were Japanese-made. I’d welcome further evidence on this point, one way or another.

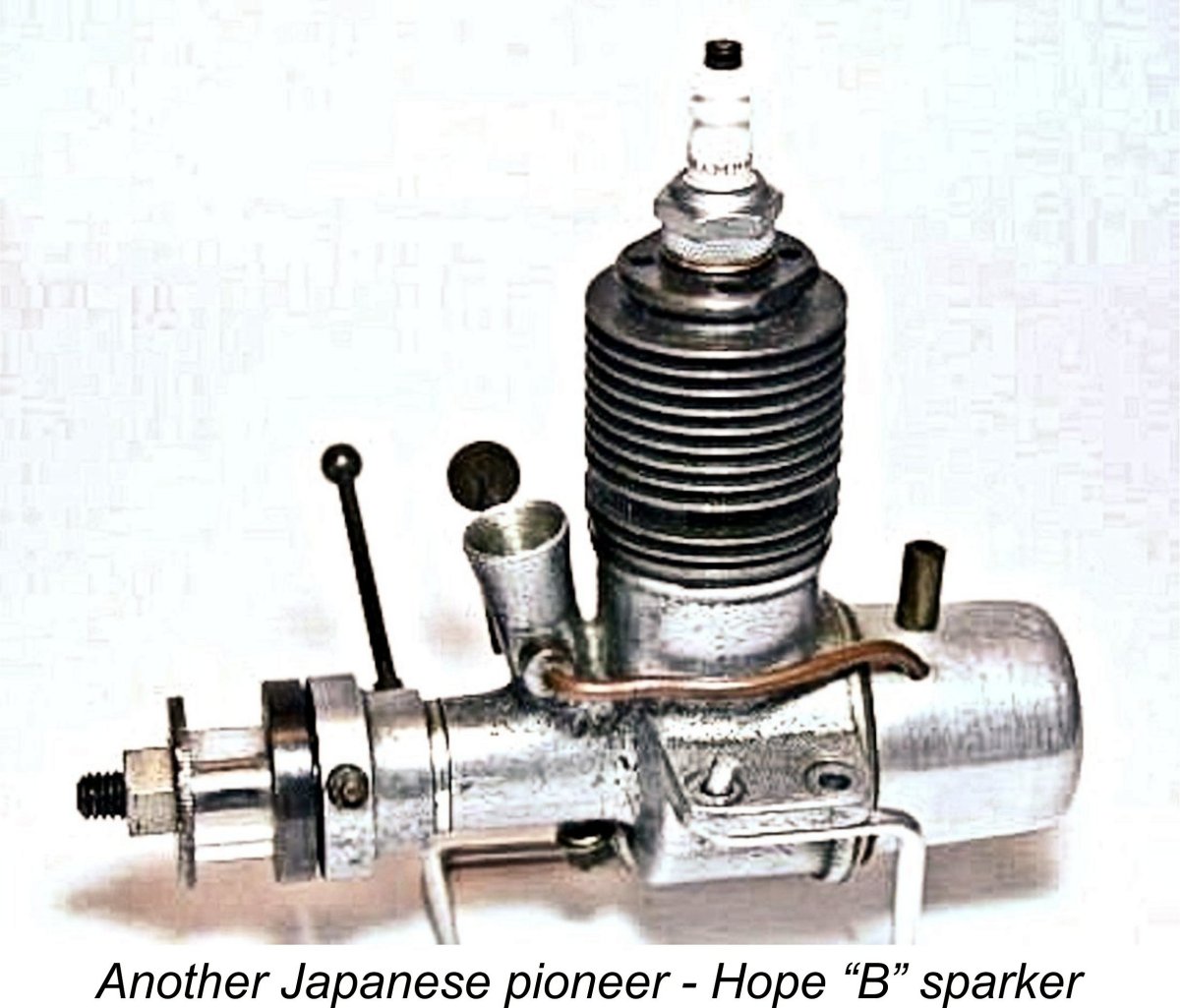

Prior to the conclusion of the war, the appearance of Anglicised names on Japanese products was strictly forbidden by the government. However, during the early post-war period Japanese manufacturers began to fall over themselves in applying Anglicised names to their offerings. In a model engine context, these names typically carried connotations of speed, power and progress. Such names as Hope, Great Leap Forward, Typhoon, TOP, PEAK, Mighty, and the like appeared regularly in the marketplace, so Boxer with its implications of speed, power and stand-up aggression fits right in with this concept. The Anglicisation of the engines' names was doubtless calculated to increase their appeal to the primarily English-speaking markets represented in Japan by the occupation forces.

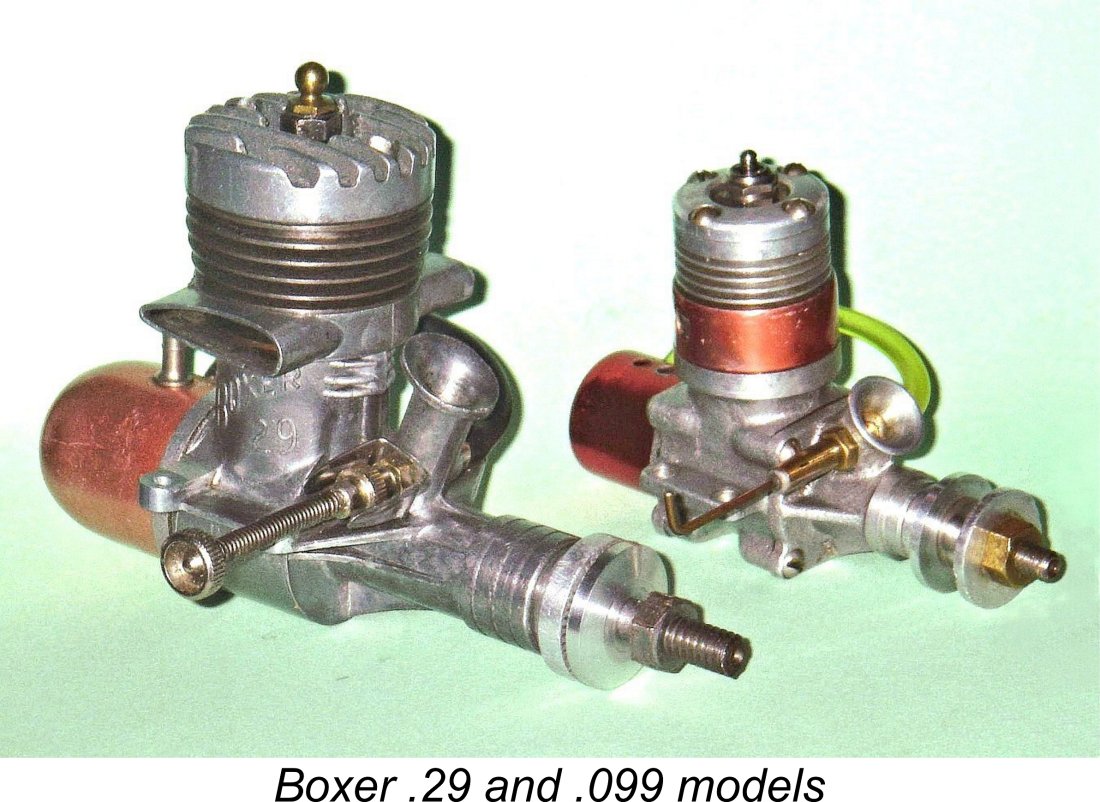

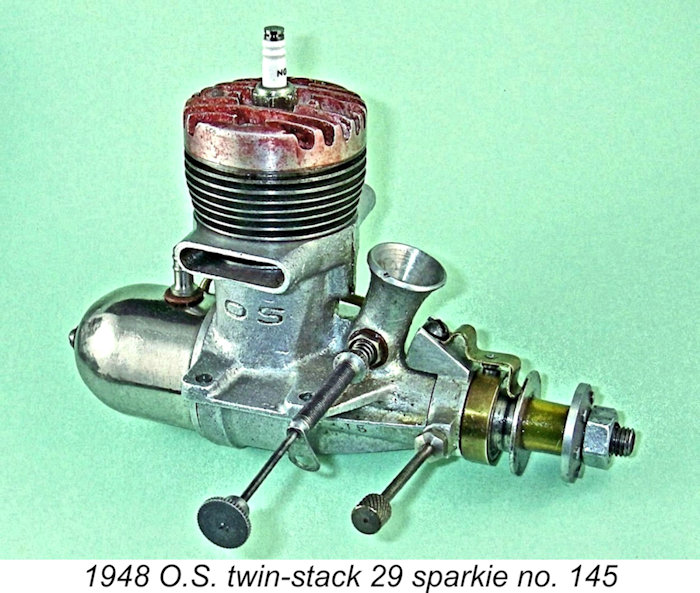

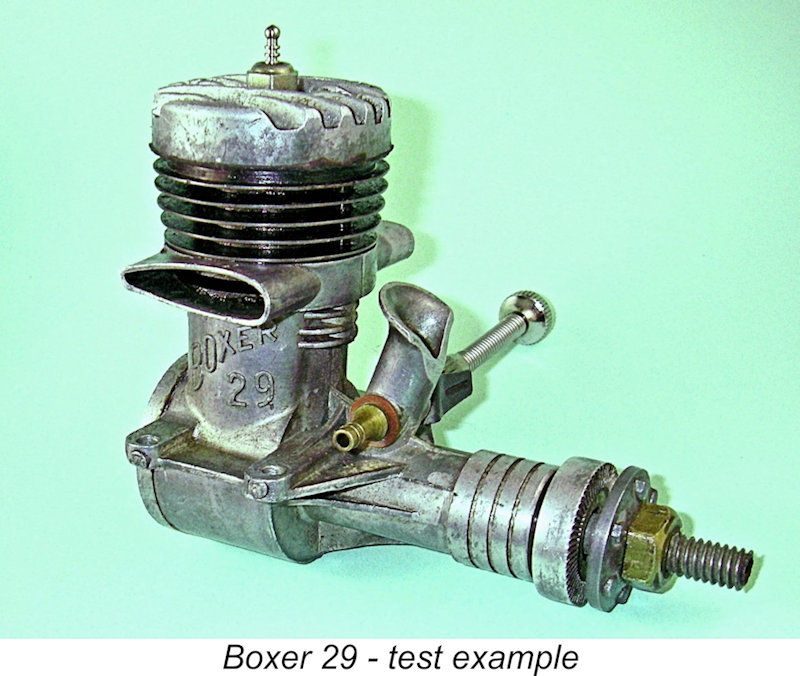

When I come to draw a few conclusions regarding the dating of the Boxer engines, I’ll have occasion to refer back to the above discussion. The two Boxer models of which I’m presently aware are the .29 and the .099. Both of these are glow-plug models - indeed, to date I’ve encountered no evidence whatsoever to suggest that the Boxer range ever included a spark-ignition model (or a diesel for that matter). Combined with the obvious O.S. influence to be discussed below, this seems to place the introduction of the range to late 1948 at the earliest. There is persuasive architectural evidence to suggest that the twin-stack 29 model is the earlier of the two Boxer designs which have so far come to my attention. Accordingly, I’ll begin with a description of that model. The Boxer 29

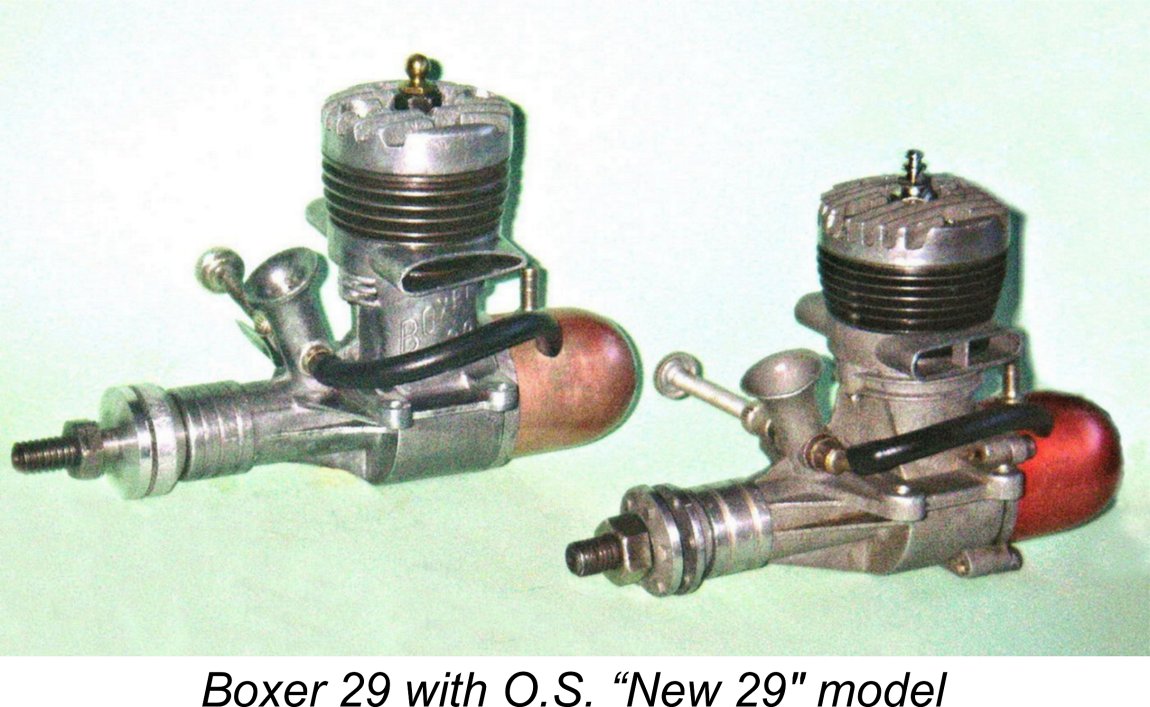

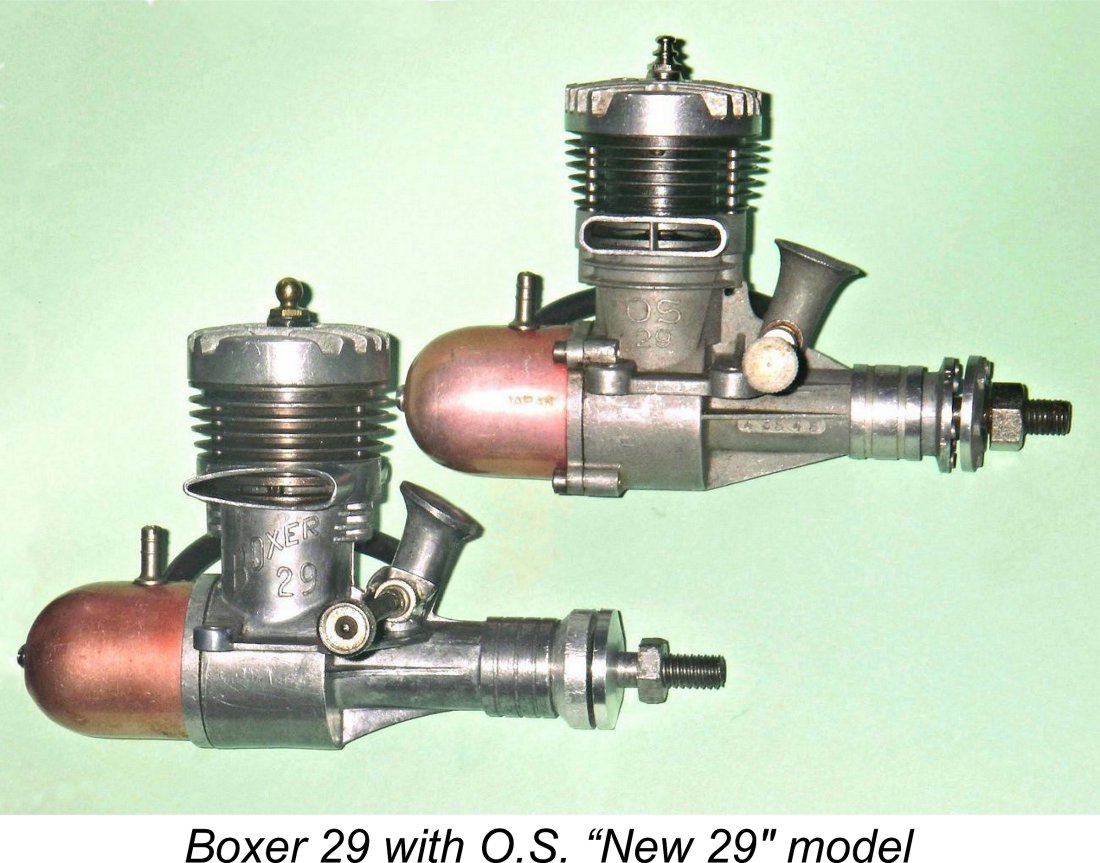

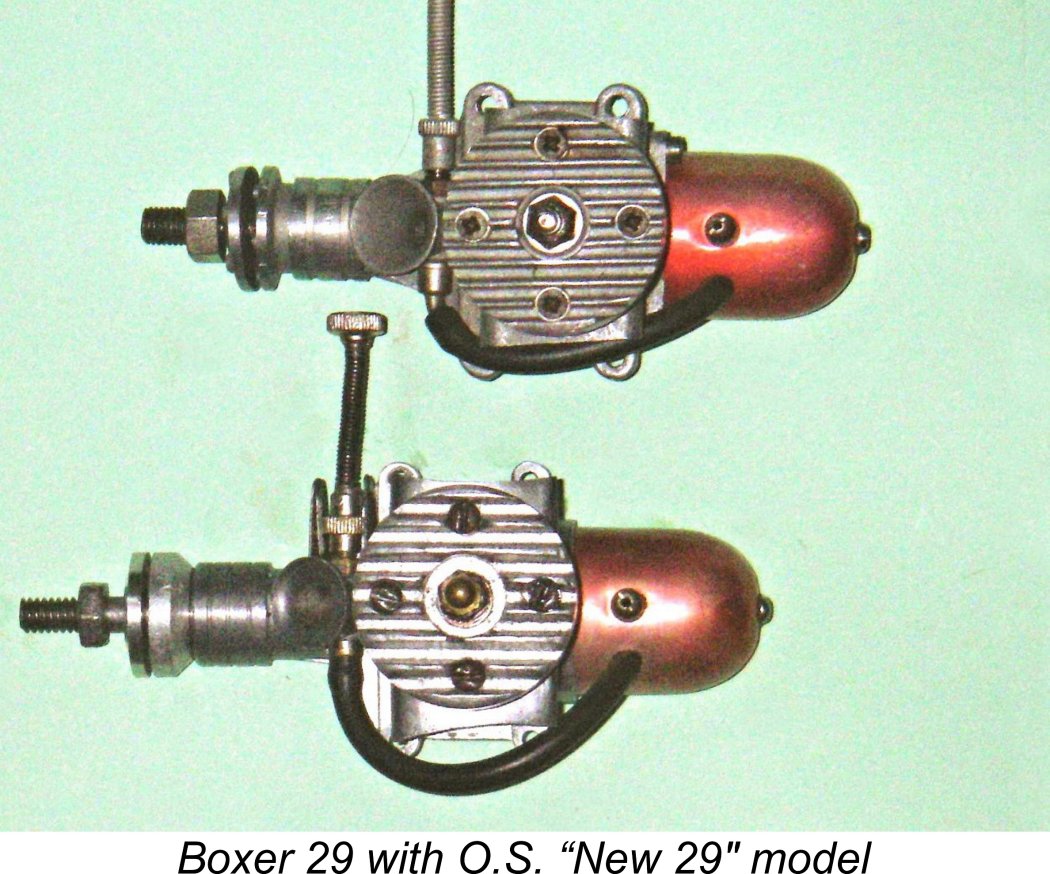

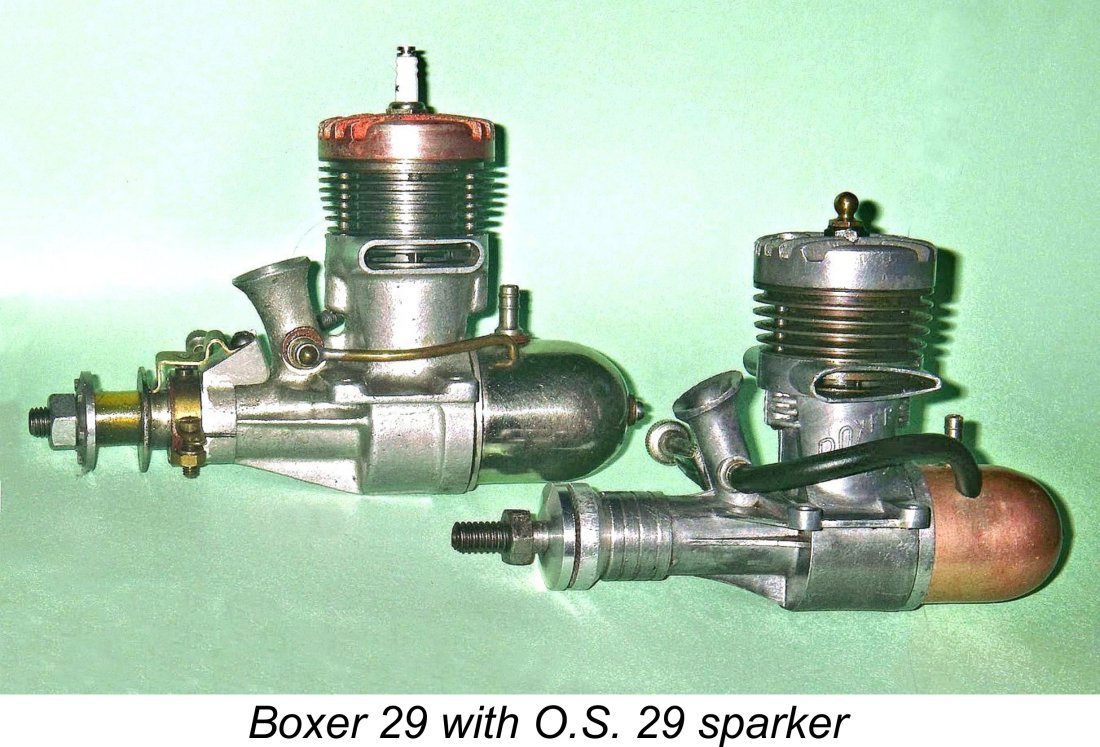

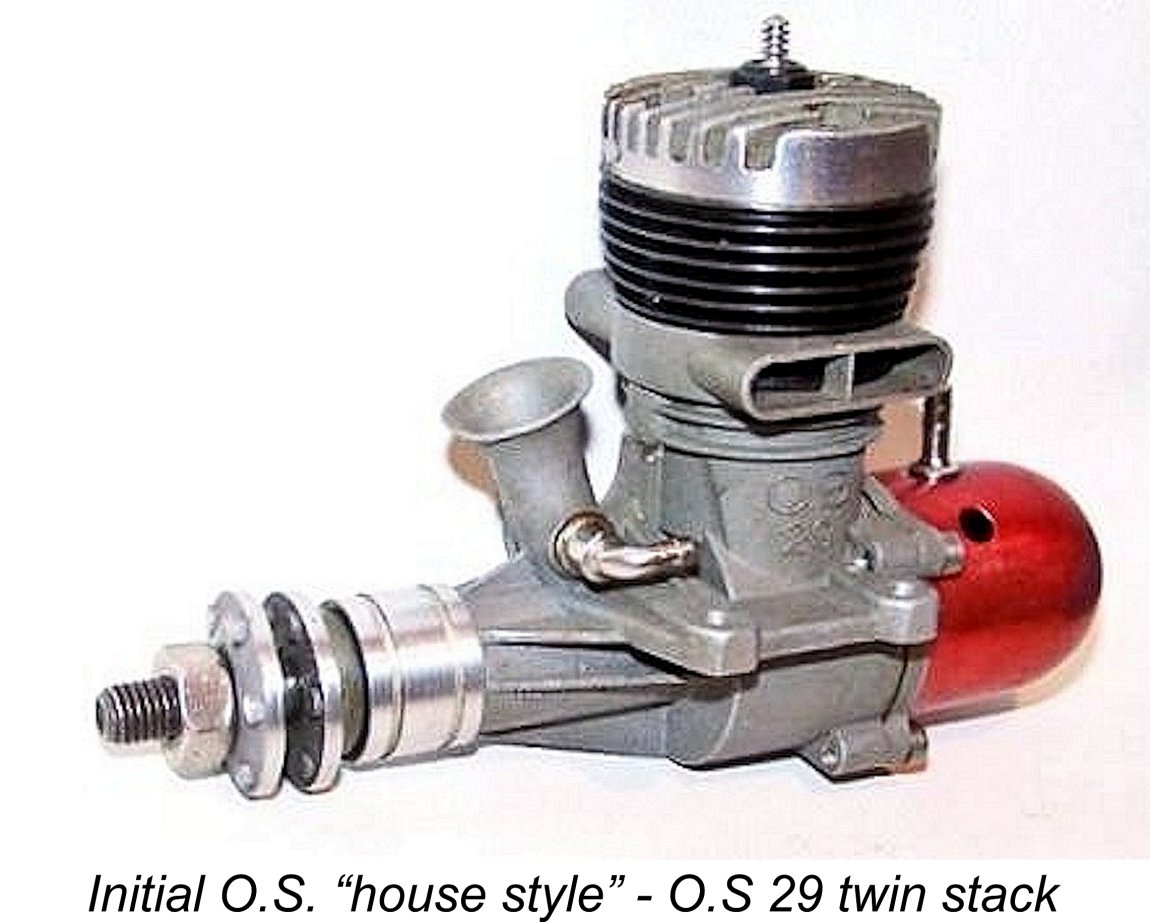

In order to do so, it will be necessary for me to draw the reader's attention to both the similarities and differences between the O.S. and Boxer models. It's perhaps most logical to start with the tale of the tape. Here we find that the Boxer and O.S. twin-stack designs share the same bore and stroke figures of 18.8 mm and 17.3 mm respectively for identical displacements of 4.80 cc (0.293 cuin.). The Boxer is slightly heavier than the O.S., weighing in at 229 gm (8.08 oz) as opposed to the 211 gm (7.44 oz) for the O.S.. It's a little hard to see where the extra weight comes from - perhaps the piston and cylinder units?

To add further individuality, the outer ends of the Boxer stacks are given a concave form in plan view, while those on the O.S. are straight with a slight rearward angle. The Boxer The name "Boxer 29" appears in rather stylized script cast in relief onto both sides of the crankcase. This mirrors the identification cast onto the case of the O.S. 29. However, unlike the O.S. there is no serial number on the Boxer. Nor does the Boxer emulate the O.S. in claiming to be "Made in Japan". Indeed, the only evidence that we have for a Japanese origin at present is a single documentary reference from Peter Chinn (to be noted later) plus the anecdotal opinions of several latter-day Japanese and US sources. One possibly significant difference in the crankcase design is the treatment of the mounting lugs. Those on the Boxer are far thinner and seemingly more fragile than those on the O.S. glow-plug model. In fact, the Boxer lugs are far closer in thickness to those used on the earlier sand-cast O.S. spark ignition model. This may help us in attempting to understand the relationship between the O.S. and Boxer models, since this feature appears to place the Boxer more in the "minimalist" design camp which was in the process of losing favour as of 1949. The porting arrangements for the two engines are identical, with crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction and semi-radial cylinder porting. The exhaust port flange sits on a recessed shelf machined into the upper crankcase casting just below the lower edge of the twin stacks. A seal is ensured through the use of a gasket. There are two pairs of exhaust ports on either side, each pair feeding into one of the two stacks. The paired transfer ports are located directly below the exhaust ports. They are fed by two bypass passages cast into the crankcase, one on each side. The only difference is that the steel cylinder and integral cooling fins of this example of the Boxer are left in their natural state, while those on the O.S. glow-plug model are blued, as are those of other examples of the Boxer which have come to my attention. The Boxer also has fewer but slightly thicker cylinder cooling fins than the O.S.. The hold-down system for the cylinders and heads on both models is identical, with two long screws extending downwards fore and aft through holes drilled through all the cooling fins to engage with tapped holes in the crankcase castings, and two additional short screws on each side to support the main screws in securing the cylinder head. Interestingly, the apparently-original screws on the Boxer are slot-head items, which generally signifies a relatively early date in a Japanese context. The 1948 O.S. spark ignition twin-stack model described elsewhere also used such screws, but the later glow-plug version switched to Phillips-head items in keeping with emerging Japanese practise. The backplates on the two models are of entirely different design. That on the Boxer is a screw-in component similar to the item used on the original sand-cast O.S. 29 spark ignition model, while the backplate on the O.S. glow model is secured by four screws at the corners. In both cases a gasket is used to provide a seal. Another obvious difference between the two designs is the method of producing the cylinder heads and the backplates. On the Boxer and on the earlier O.S. spark ignition model, both of these components are sand-castings, while the O.S. glow-plug model uses pressure die-cast components throughout. The cylinder head of the Boxer has fewer and thicker fins than its O.S. "New 29" counterpart, but is very similar to the head of the original (and quite rare) 1949 O.S. twin-stack glow model, which had fewer head fins than its 1950 successor.

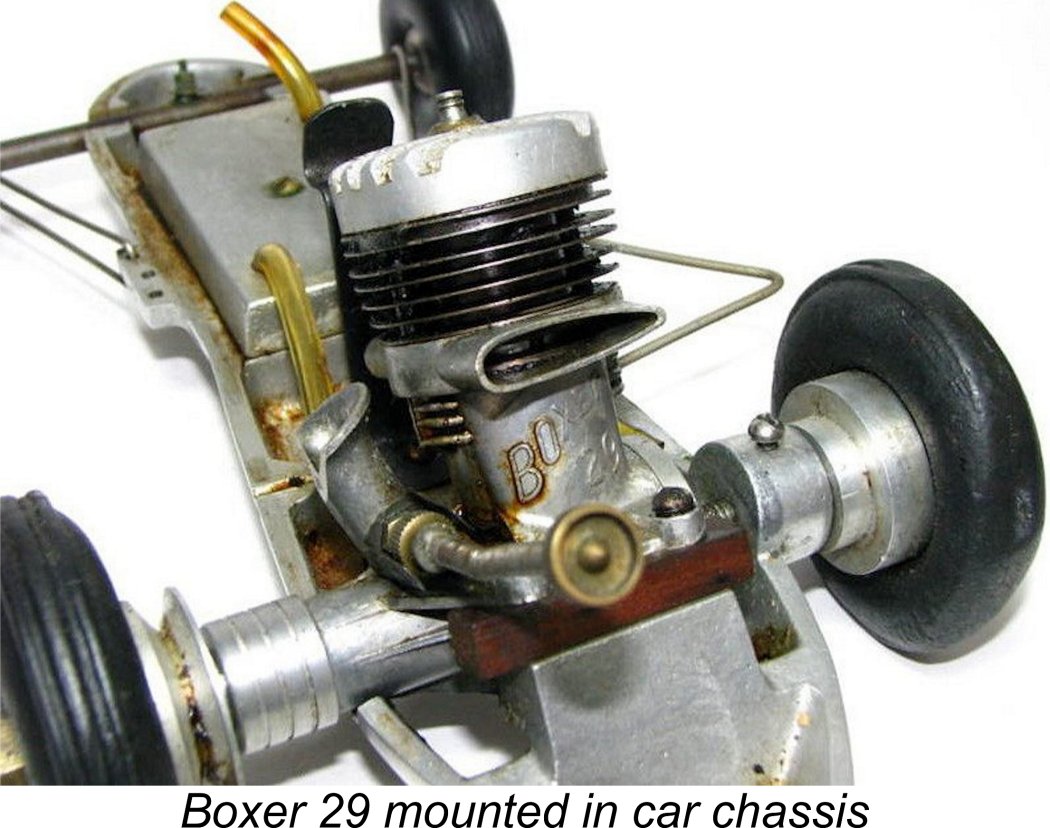

For these reasons, I elected not to disturb the engine beyond the removal of the backplate. This was sufficient to show that the crankshaft and rod in the Boxer are very similar indeed to those in the O.S.. The main difference is that the Boxer follows the lead of the earlier O.S. spark-ignition model in using a conventional gudgeon pin mounted in bosses in the piston as opposed to the separate riveted carrier used in the O.S. glow-plug models. The Boxer piston is flat-topped with a chamfer around the edge (in effect, a truncated cone) as opposed to the conical form of the O.S.. It's possible to confirm without dismantling the engine further that the crankshaft journal diameter of the Boxer is 11 mm, with an 8 mm diameter internal gas passage. These figures are identical to those for the O.S. twin-stack models - indeed, the shafts from the two I'm unable to confirm whether or not the needle valve assembly with the illustrated example of the Boxer is original or not. It fits perfectly, with the jet hole being in exactly the correct lateral location in the centre of the venturi, but it looks very much like an early Enya unit except that the double spring clip which provides needle tension is rather longer on the Boxer than on the Enya's in my collection. That having been said, both of the other Boxer 29's that I've seen on offer recently had needle valve assemblies which appeared to be identical to mine. In addition, both of these other examples had portions of their intake venturis filed away. One of them was still mounted in a car chassis, as seen below at the left. This image clarifies the reason for the intake filing - it was necessary to provide clearance between the engine and the car body. The other example was in aero form (albeit without a tank), but had clearly seen car service, hence the filed intake.

I trust that I've demonstrated that the similarities between the Boxer 29 and the various O.S. twin-stack 29's are far too great to be coincidental. This invites the old chicken-and-egg question - in which order did these engines appear? Here I’m unavoidably forced into the realm of informed speculation. There's little doubt that the first of the Japanese 29 twin-stacks with which we are dealing was the sand-cast O.S. 29 spark ignition model, which evidently appeared in 1948. So the real question here is whether the Boxer came out next as a glow-plug rendition of the O.S. sparker by another maker (whether Japanese or otherwise) or whether the O.S. glow-plug model followed the sparker and inspired the subsequent release of the Boxer version. Either scenario is of course possible, so the following comments represent a personal view only and should not be taken as substantiated fact pending the appearance of further evidence.

By contrast, the O.S. glow-plug models use a die-cast backplate which is secured by four Phillips-head screws at the corners. They also feature far thicker mounting lugs on the die-cast case. The original 1949 model had a head with relatively widely-spaced finning very much like that of the Boxer, while the further-developed 1950 "New 29" model had more closely-packed fins on its die-cast cylinder head. Both models carried the gudgeon pin in an internal carrier which was riveted to the piston crown. They also feature the stiffening columns in the exhaust stacks.

Attention has been drawn to the presence of vestigial finning fore and aft on the crankcase below the exhaust ports of the Boxer. These fins are clearly visible in the previously-reproduced image of the crankcase interior. It has been suggested that these indicate an influence from the O.S. glow-plug models, which had sub-exhaust finning around the entire circumference of the upper case below the exhaust stacks. In my personal view, the Boxer's vestigial fins may just as easily represent an attempt by the Boxer designer to strengthen the tapped cylinder hold-down lugs against the very considerable wedging stresses imposed by the hold-down screws. It's therefore entirely possible that O.S. simply carried the Boxer concept a step further by extending the sub-exhaust finning around the entire case circumference. Overall, I don't see this as a dependable indicator one way or the other. If we were to believe that the Boxer was inspired by the later O.S. glow-plug models, we would have to believe that the designer deliberately decided to use thinner mounting lugs and also abandoned the sub-exhaust finning in addition to reverting to the less sophisticated sand-cast screw-in backplate and sand-cast head. It would be rather "un-Japanese" for the Boxer designer to have produced a retrograde design of this nature - the tendency was either to "clone" or to improve.

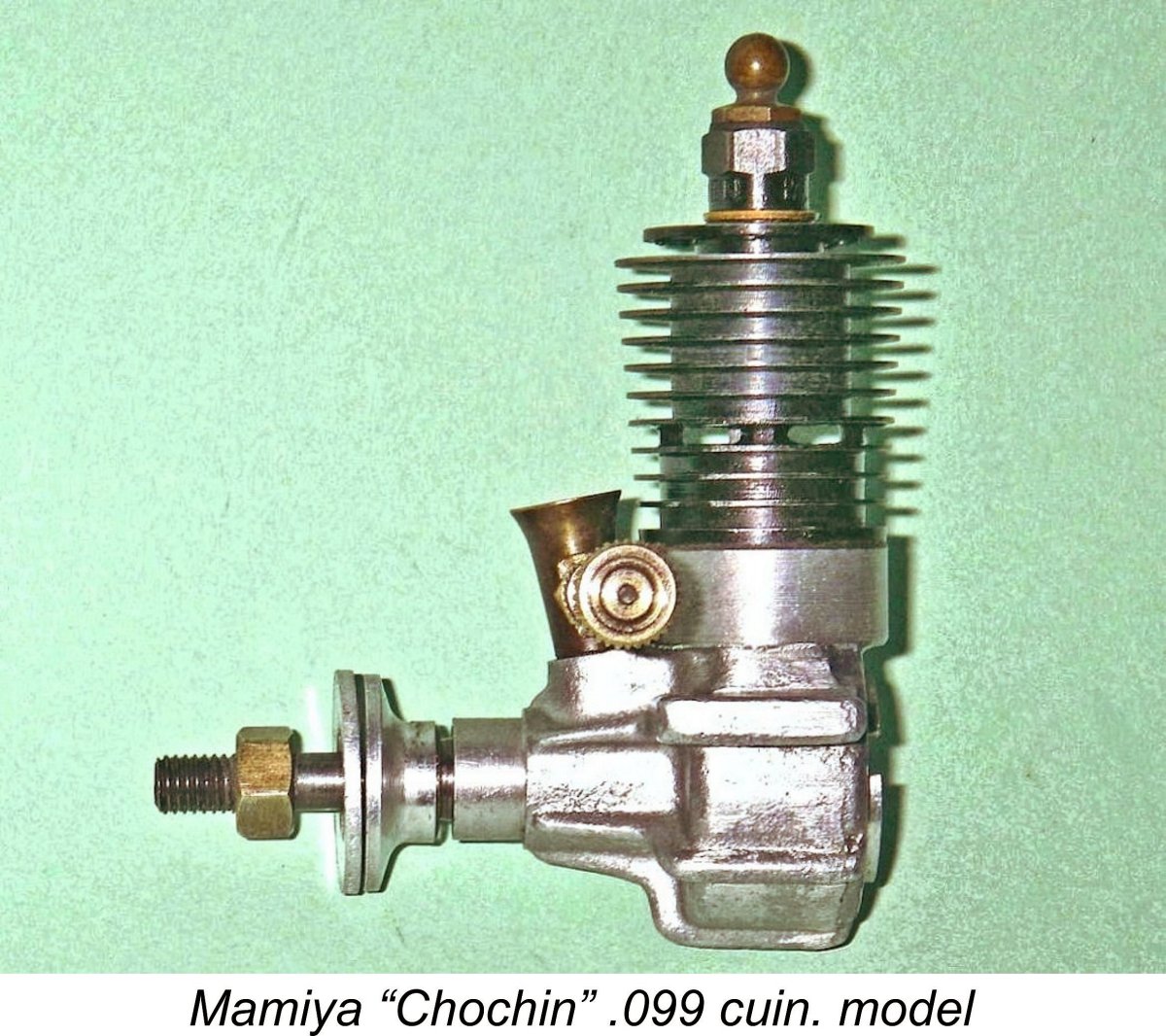

So although I can't prove it, for now I'm personally prepared to adopt the provisional working hypothesis that the Boxer 29 glow-plug model was a Japanese product that was initially inspired by the original O.S. twin-stack spark ignition model and may well have appeared on the market in late 1948 or early 1949 as a near-contemporary of the initial O.S. glow-plug model. At that time it would have been quite an advanced design by comparison with some other contemporary Japanese designs like the Hope B and the Mamiya "Chochin" engines. It actually seems entirely possible that it preceded or at least paralleled the O.S. twin-stack 29 glow-plug model onto the market. Speaking personally, I have great difficulty in seeing its introduction as having been later than 1949. The Boxer 29 must surely be among the rarest 5 cc engines to originate in Japan, assuming of course that it did so. At the time of writing of this revised article in 2025, I was aware of only four other examples of the engine in existence worldwide, and only one of those four was complete and unmodified. I must reiterate yet again that the above conjectural comments represent my personal views only - others may see the matter differently. As always, I remain completely open to any persuasive evidence that might point towards a different interpretation. The Boxer Range in the Modelling Media This section of the article won't delay us long, because there's very little to say! The sole English-language reference to the Boxer range that I've been able to find appeared in an article by Peter Chinn in the April 1954 issue of "Model Aircraft". In that article, Chinn discussed the currently-available International class (2.5 cc) engines from various countries and noted that Japan had no engines in that class at the time, the nearest displacement category in use in Japan being the .099 cuin. category. The Boxer .099 was specifically included in the list of .09 cuin. engines then in production in Japan. Chinn implied that the Boxer .099 was part of the Boxer "range", suggesting that other Boxer models may have remained in production at his time of writing (early 1954, allowing for editorial lead-time). Rightly or wrongly, Chinn clearly believed that the Boxer engines were of Japanese origin. However, by the time Chinn published his list of glow-plug engines for 1954/55 in the May 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft”, we find no mention of the Boxer engines. We know from the earlier article that Chinn was aware of this range and we may safely assume that it would have been included if it was still current even in late 1954. It thus appears that the Boxer range vanished from the market at some point during 1954, at least as far as Chinn was aware. And that, believe it or not, is all that I’m able to deduce from the contemporary English-language modelling media. Unfortunately, these references offer absolutely no support for my estimate regarding the probable 1949 introductory date of the range. If anyone out there has a reference that I've missed, please share it! As it is, all that remains for me to do is to describe the other Boxer model that has come to my attention - the Boxer .099. The Boxer .099

I noted earlier that circumstantial and architectural evidence seem to me to place the introduction of the Boxer 29 in 1949 at the earliest. I’ve just presented documentary evidence to suggest that the Boxer range appears to have departed from the scene at some point in 1954. At present I have no information whatsoever on the date of introduction of the Boxer .099, but on architectural grounds it appears likely that it followed its larger brother onto the marketplace in the early 1950's, perhaps around 1950 or 1951. At present I can't be any more definite than that. The only contemporary image of this engine that I have at present appears on an undated Japanese-language promotional leaflet issued by a Tokyo-based company calling itself the Yuhido Corporation. This image is invaluable because it shows the engine in its as-sold configuration. Once again, I'm immensely indebted to Alan Strutt for making an image of the leaflet available. I obtained a translation of this leaflet in hopes that it might tell me more about the Boxer range, but sadly this hope was not fulfilled. The Yuhido Corporation does not appear to have been the manufacturer of the Boxer engines - instead, the company characterized itself as a wholesaler and retailer of technological products, clearly very much including model aircraft. The Boxer .099 was simply included as the latest model engine on offer from the company, along with a kit called "Mr. Trainer" which could apparently be built in only three hours! Readers of the leaflet were invited to contact the Yuhido Corporation with "any questions about model airplanes".

The leaflet also stated that the Yuhido Corporation offered "a complete selection of all types, all models and all makes" of model engines. This being the case, it's interesting that the Boxer .099 was specifically featured in this leaflet - perhaps the Boxer engines were a "house brand" of the company?!? Or perhaps it was just the latest engine on offer at the time when the leaflet was produced. The "house brand" scenario plus the absence of any "Made in Japan" designation on the engines themselves once again raises the interesting possibility that the Boxer engines might not have been made in Japan at all but might have been produced for Yuhido under contract in, say, Taiwan (or Formosa as it was then generally called). It also raises the possibility that the two very different models (.29 and .099) could have been produced by two different manufacturers under separate contract. This would certainly explain the very different design and production styles of the two models. I must make it clear that at present I have absolutely no evidence to support such interpretations, but these possibilities should be borne in mind by future researchers (if there are any!). One very interesting tid-bit that comes from the leaflet is the fact that the Yuhido Corporation had been established in 1908! This made them a contemporary of Gamages in London, which included what amounted to a hobby department from the early years of the 20th century onwards. There's no certainty that the Yuhido company was in the modelling business back in 1908, but the possibility exists given the surprisingly long history of modelling in Japan to which reference was made earlier. A company called the Yuhido Corporation (Yuhido KK) remains in business today, dealing in mechanical and electrical products. It claims to have been in business for a "long time", making it entirely possible that it is the same company still going after over 100 years. If so, it outlasted Gamages, which closed in 1972!

The illustrated example also arrived without a needle, and the item with which it is now fitted is a reproduction based visually upon the component in the illustration on the Yuhido leaflet. The spraybar appears to be original. The thread is a rather obscure 3.5 mm x 0.35 mm, and my lack of such a tap at the time forced me to use a home-made tap to produce the split thimble for the repro needle. On the upside, this might be expected to provide extremely fine mixture control in service.

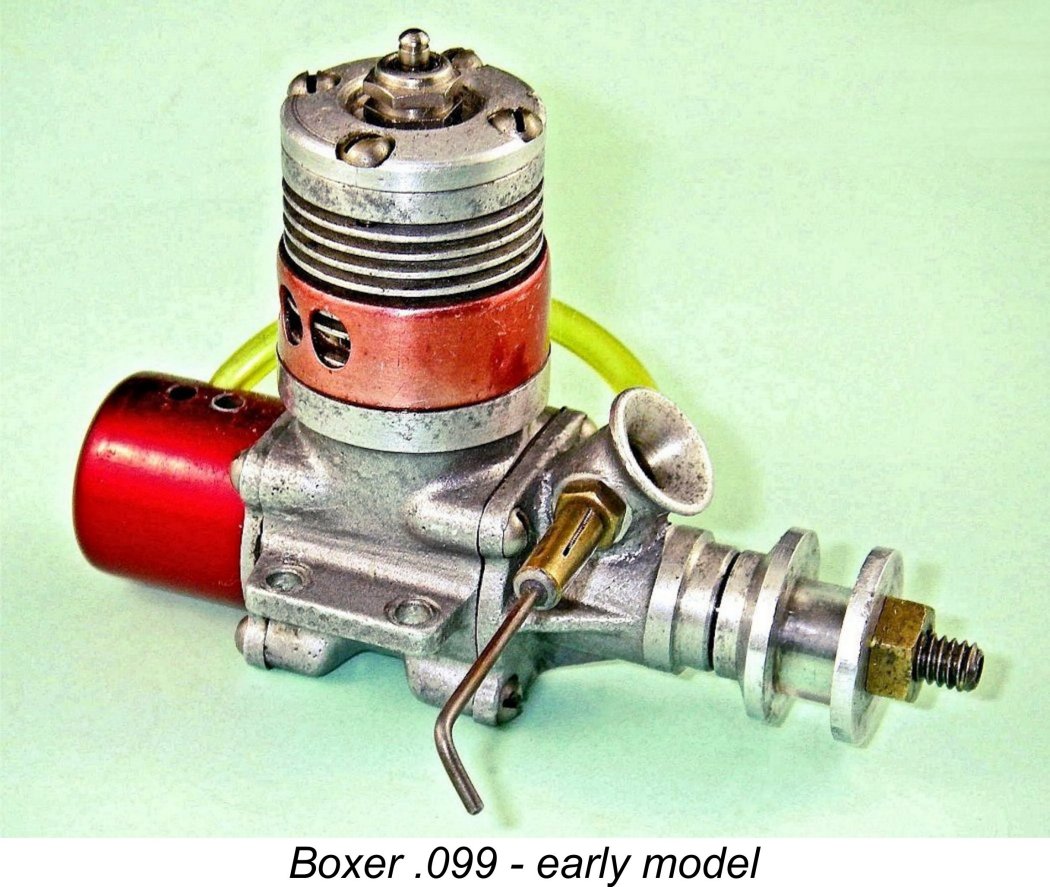

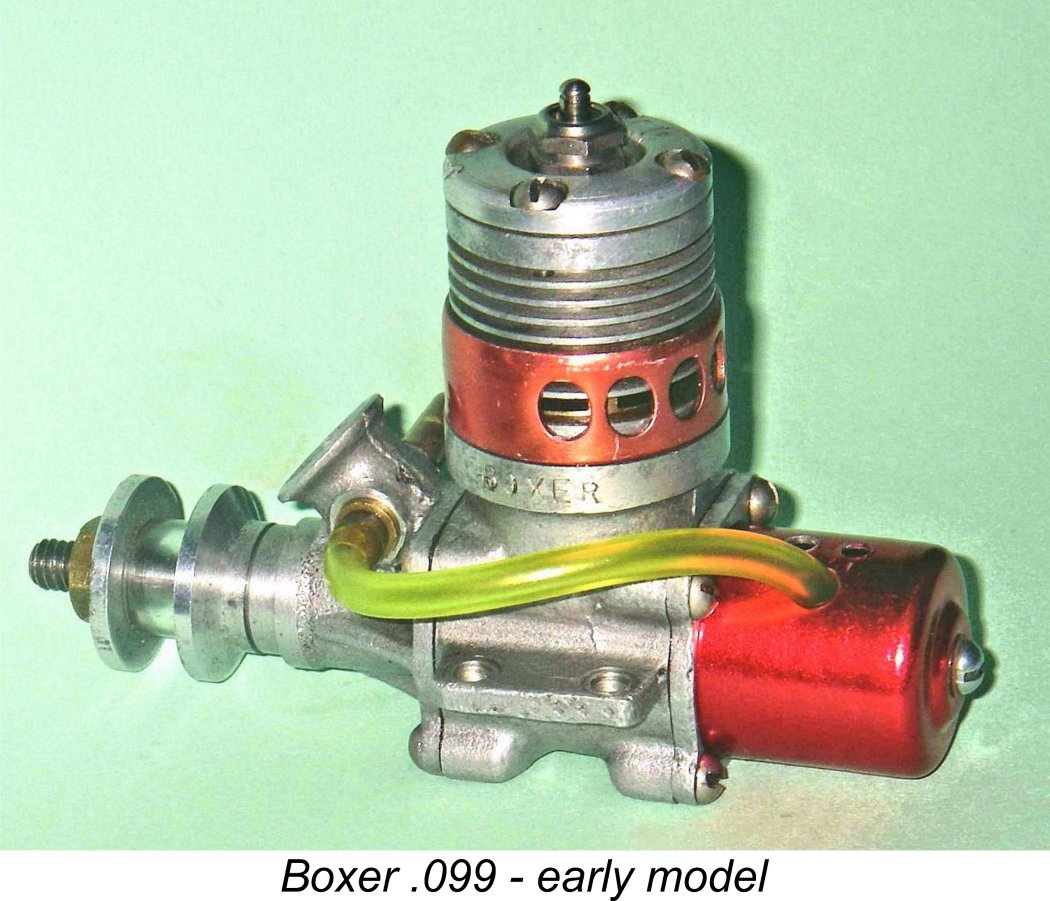

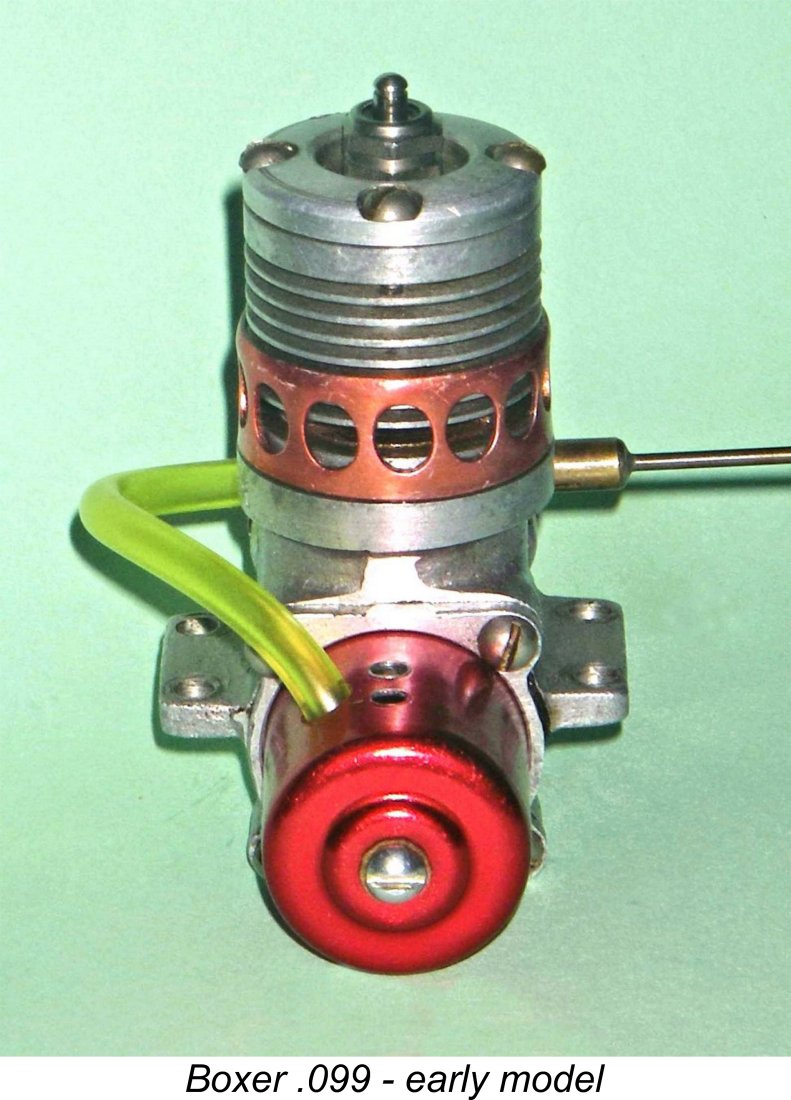

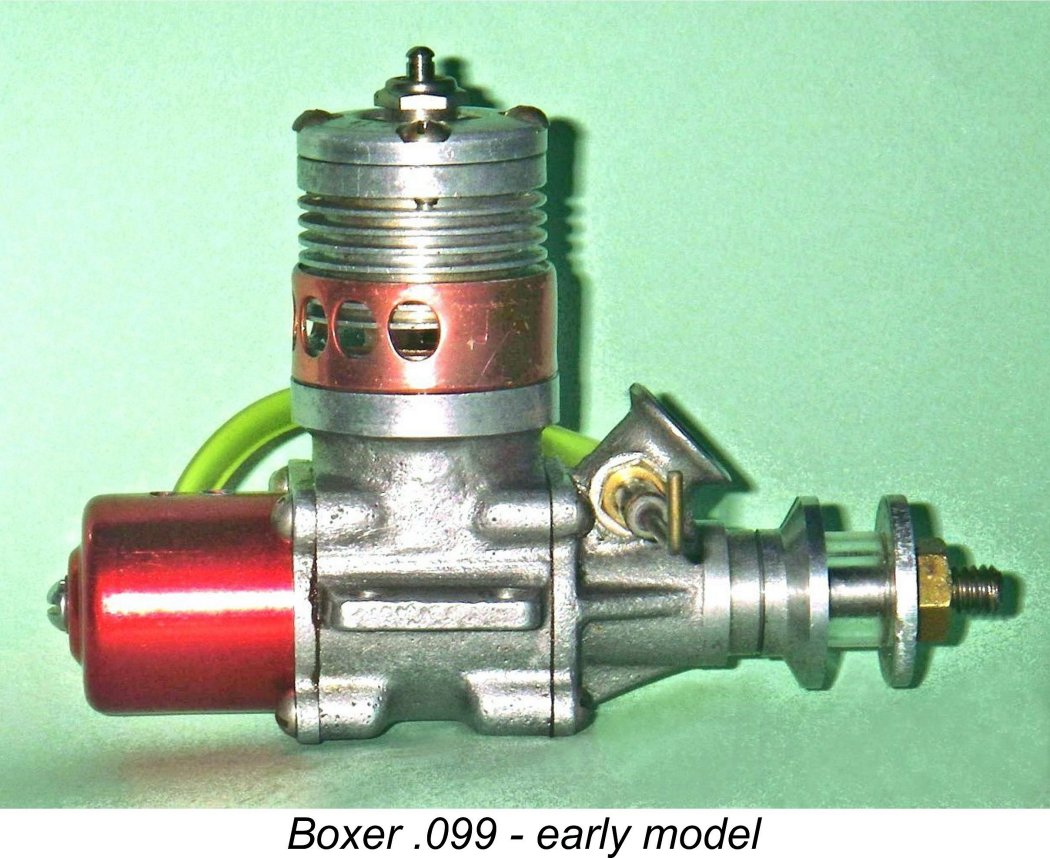

The most immediately obvious visual anomaly that leaps out at an observer is the red-anodized exhaust collector ring which surrounds the exhaust port belt. This has large oval holes stamped around half its circumference and can be rotated to any desired position to direct the exhaust in an appropriate direction for the model in question. It is a slightly "binding" fit, which should encourage it to retain its position once set. It can also be removed entirely if desired by slipping off past the cylinder head, and it's a good bet that many of them were removed in this way and subsequently lost. Fortunately, this has not been done to the illustrated example - I imagine that complete examples are relatively rare. The engine is based upon a set of well-executed sand-castings, all of which are relatively massive for an engine of this displacement - nothing in the least minimalist about this design!! The use of sand-casting throughout is another somewhat odd feature - we know that the makers of the Boxer 29 were well able to produce excellent pressure die-castings. So why the switch to sand-castings? Perhaps a different manufacturer was involved, as suggested earlier?!? I'd welcome any other ideas.

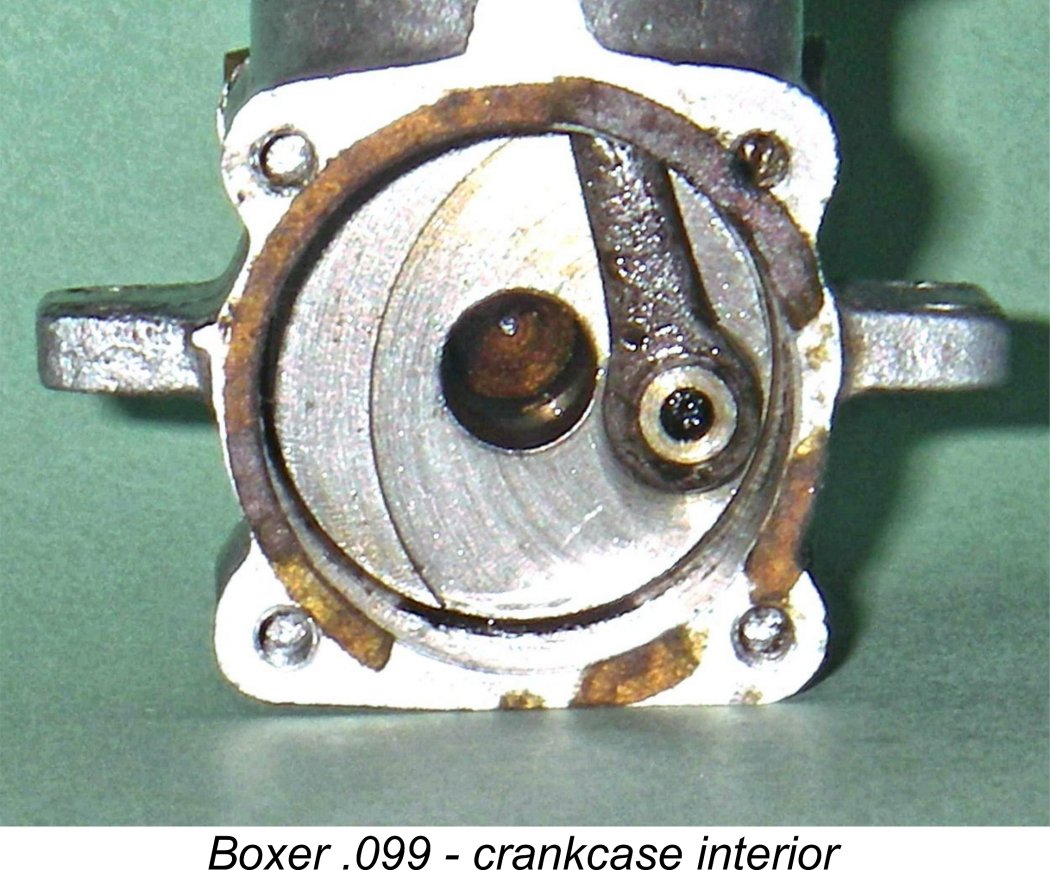

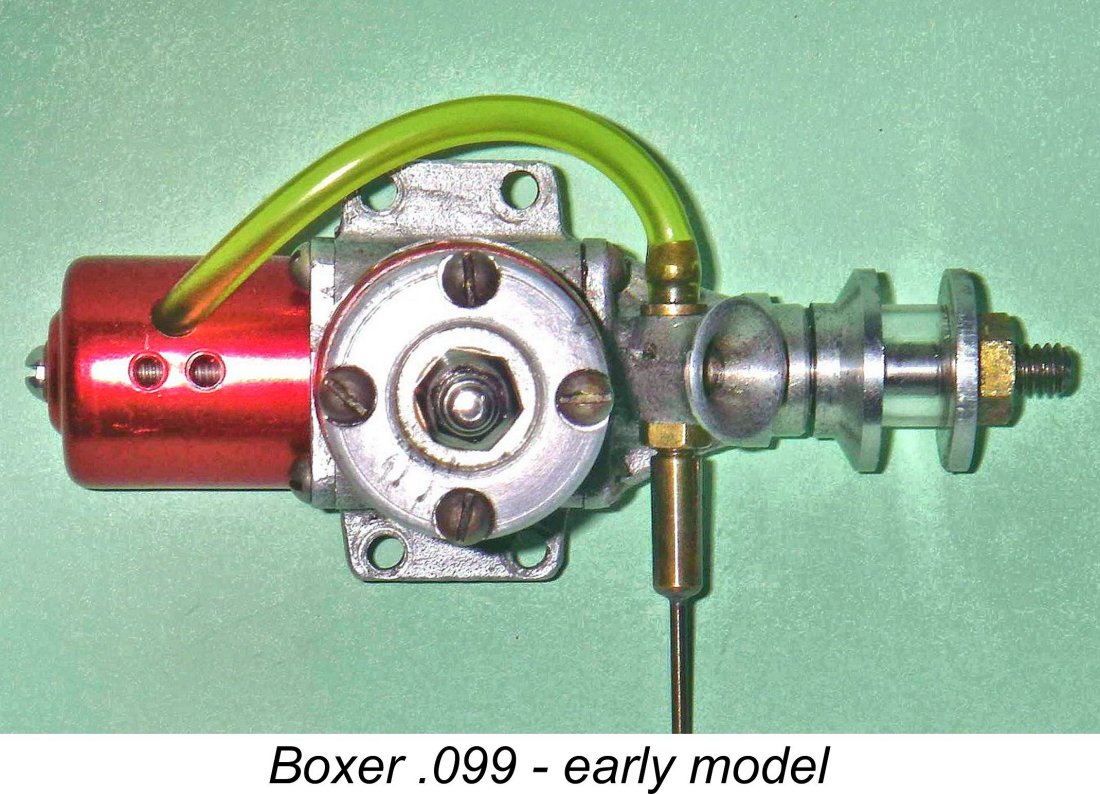

Another design feature which is somewhat individualistic is the fact that the engine has bolt-on front and rear covers. This was somewhat unusual for a sports engine of this displacement - most contemporary engines in this displacement class had one-piece crankcases with bolt-on or screw-in backplates. Enya and Mamiya of course reversed this arrangement by using bolt-on front bearing housings with cast-in-unit backplates. But as far as I'm presently aware, no other contemporary Japanese .099 used bolt-on components both front and rear. Generally speaking, this form of construction was confined to racing engines. It seems possible that the manufacturers adopted this route to give themselves the option of developing a rear induction version of the engine. I have yet to find any evidence of the existence of such a variant, so at present there's no reason to suppose that such a model was ever produced. The backplate seals to the case with a very thin and typically Japanese circular paper gasket without "ears" for the screws at the corners. The fit of this component in the case emphasizes the precision of manufacture - it is a slightly tight plug fit in the case and would almost certainly seal without a gasket Removal of the backplate in defiance of the above cautionary note reveals that the engine uses a forged steel con-rod along with a conventional steel gudgeon pin and a cast iron piston. The one-piece steel crankshaft has a full-disc crankweb with a modest counterbalance. The journal diameter is 8 mm with an internal gas passage of 6 mm diameter, resulting in a rather minimal wall thickness of only 1 mm. This is probably adequate for a relatively low-powered sports glow-plug engine of this displacement, but still seems a bit marginal. The induction port (visible through the venturi) is a simple round hole drilled through the shaft wall. The shaft runs directly in the material of the case, no bushing being used. By feel, the shaft is a superb fit in its bearing - in fact, all fits throughout are beyond reproach.

The cylinder head is a plain unfinned unit which is secured to the cylinder using four screws. Unlike the screws used for the backplate, these are of adequate length and utilize all of the available thread in the upper cylinder flange. The use of a long-reach plug is implied by the length of thread provided for that component. The plug is centrally located. The steel cylinder itself is a screw-in item with integrally-machined cooling fins. Unusually, these fins are cadmium-plated, the plating being applied only above the port belt. Porting is Oliver-style, with three generously-proportioned milled exhaust ports separated by pillars. The transfer ports consist of holes drilled at an angle upwards though each of the three pillars to overlap the exhaust to a considerable extent.

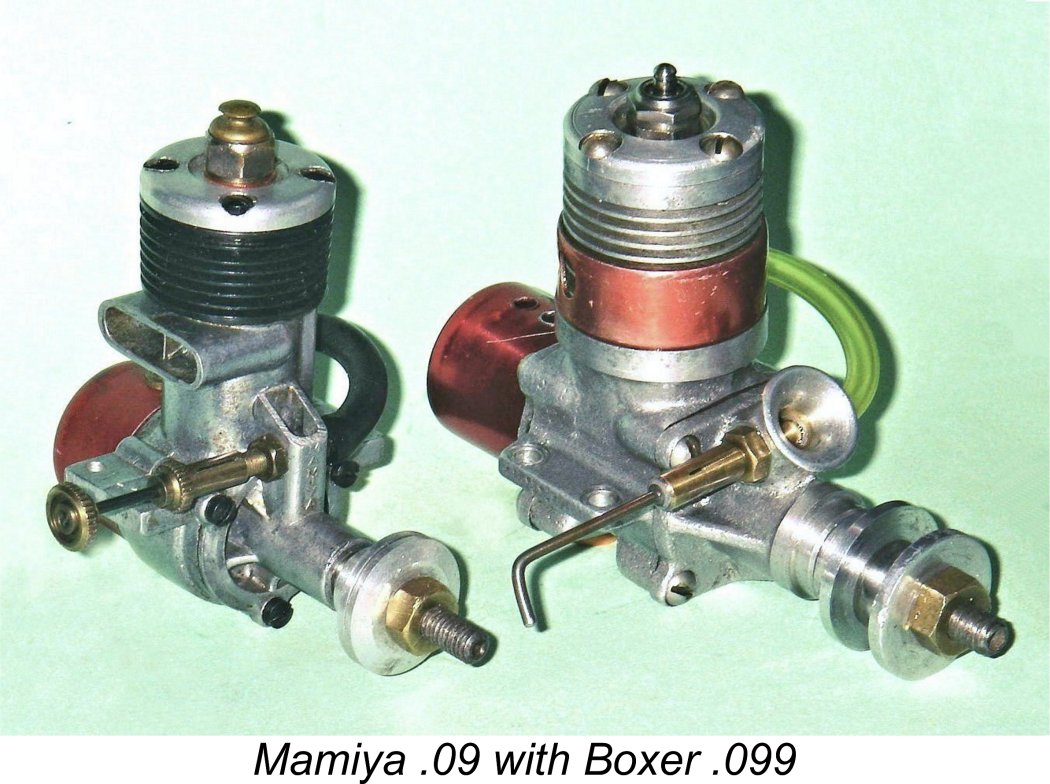

In view of the above observation, I elected not to disturb the engine further, since there was no way that I could guarantee that it would go back together in precisely the same alignment. Since the engine was clearly well run in, I judged it best to leave well alone. Accordingly, the above description is as far as I'm able to go unless further information becomes available down the road. The Boxer Engines On Test I For the tests, I used a fuel containing plenty of castor oil and 10% nitro. I also chose airscrews that would not have any tendency to lug the engines - always a wise approach when running glow-plug engines given the lack of any positive ignition timing control while running. To provide a bench-mark for comparison purposes I also brought along my "flying" example of the O.S. "New 29" model which has so much in common with the Boxer .29 in design terms and is almost certainly a contemporary product. As a bench-mark competitor for the Boxer .099, I included a Mamiya .099 of the post-1950 loop-scavenged variety, which was almost certainly a contemporary of the Boxer .099.

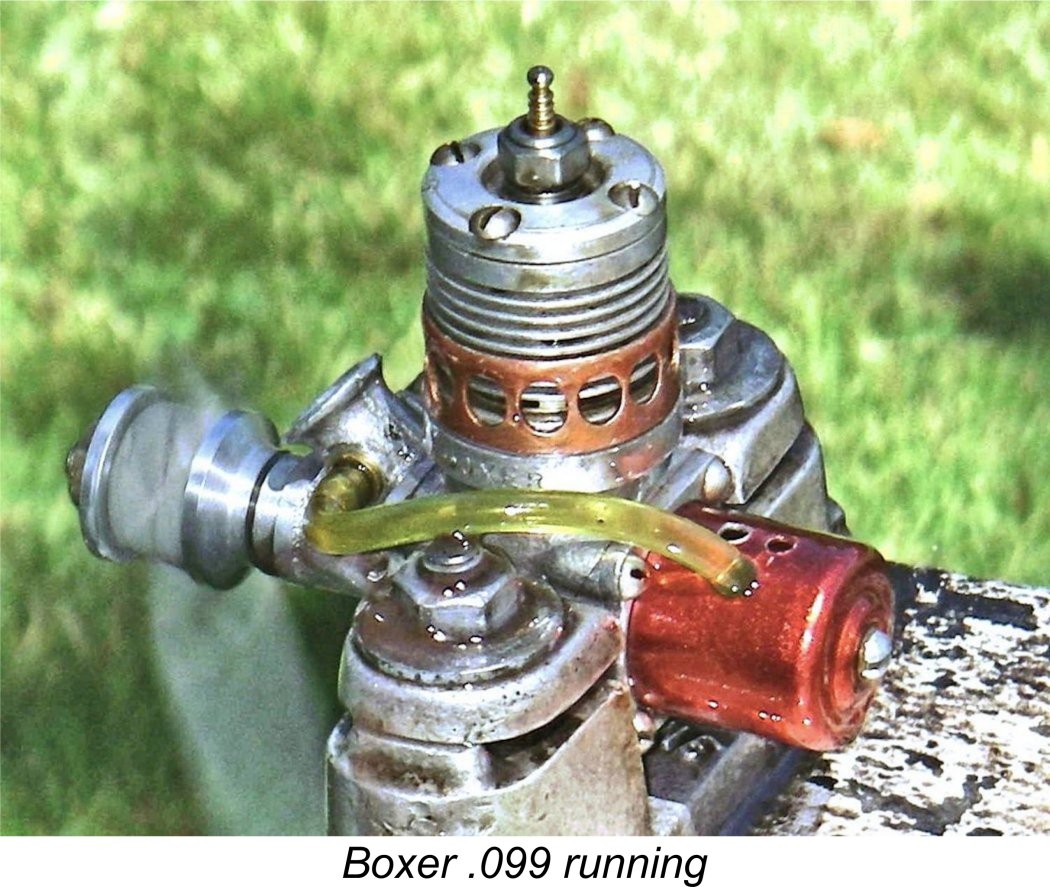

The exhaust collector ring proved to be insufficiently tightly fitted to prevent rotation while the engine was running, and I must admit to seeing this fitting as being of very questionable value - it simply rotated continually while the engine was running, thus ensuring that the exhaust spent time being fired out in all directions rather than any particular intended direction! If I were planning to use this engine in a model, I would almost certainly remove the collector ring, as many owners no doubt did. I used the back tank for all testing. There's no assurance that the modified OK Cub .074 tank now fitted is of identical capacity to the original - I merely trimmed it to a length which appears to match that shown in the Yuhido Corporation image presented earlier. Be that as it may, the present tank gave an 80 second run when the engine was propped for over 11,000 rpm - an adequate duration for free flight use. Both the Boxer and the Mamiya were tested using the same props and fuel. The Boxer was well down on the far lighter Mamiya on all props tested. Actual figures were as follows:

Turning to the larger engines, I first tested the O.S., which started and ran superbly as always and delivered a very sturdy performance. When I switched to the Boxer, I immediately found that the compression seal on this well-used example is marginal for hand-starting, although in my judgment there was just about enough. I was still working away on it trying to find the correct needle setting when I noticed that the engine felt a bit loose in the stand. Upon investigation, it turned out that one of the repaired mounting lugs had re-fractured. So that was it for this test. I was easily able to repair the problem using JB Weld, but this engine is now sitting in my collection in the "non-running" category - I won't try again given the demonstrated risks. In any event, it probably doesn't matter much. The fact that the engine is pretty much a clone of the O.S. in strictly functional terms implies that it would likely deliver a somewhat similar performance. On this test, the O.S. delivered the following figures:

These figures imply a peak of perhaps 0.420 BHP at somewhere in the region of 12,000 RPM - a very useful performance for a 1950 sports design! The Boxer might not match that, but there seems to be no reason why a good example shouldn't come reasonably close.

I decided to run the same props that I had used some years earlier when testing the O.S. 29, also using the same castor-based 10% nitro fuel. Although the test was taking place years after that of the O.S., potentially under differing atmospheric conditions, the figures would at least allow a rough comparison of the two engines' performances.

...........but not for long! The engine recommended itself to me by starting on the very first flick - not bad after years of sitting around with a well-congealed coating of castor gum and accumulated grime (all of which I had cleaned out beforehand). This turned out to be the norm - first-flick starts were pretty much routine following that port prime. I had guessed rather rich on the needle, but a bit of tweaking soon had things well sorted. The Boxer proved to be an extremely smooth and steady runner, also being very responsive to the needle. Optimum settings were therefore extremely easy to establish. However, this example of the Boxer was well down on power by comparison with the O.S. competition. As mentioned earlier, compression seal was a little on the "soft" side, and the clearly-experienced engine is probably well past its best. That said, it still handles superbly and runs very smoothly, with no tendency to sag when fully warmed up. The following figures were recorded using the same props that had been tried during the earlier test of the O.S. 29.

As can be seen, this example of the Boxer was some 1,500 - 1,800 RPM down on the O.S. on the same props. Indications are that it produced some 0.242 BHP @ 11,000 RPM. It's certainly true that the test example of the O.S. (which I still have) is in far better condition than the well-used test example of the Boxer, having seen relatively little previous use by comparison. That said, I can't see even a relatively new example of the Boxer challenging the O.S. in performance terms. It's best characterized as a very useable and well-made engine which would have provided an owner with good service as long as performance wasn't the primary criterion. So Why Buy a Boxer? .......which is undoubtedly the question that we're left asking ourselves after going through the above exercise! The Boxer 29 is in effect a clone of the O.S. .29 glow-plug model, albeit of simpler and (it must be said) less sturdy construction. Looking at the two engines side by side, most people would undoubtedly go for the O.S. - it simply looks far more sturdy and better-finished. In addition, it's slightly lighter, as we saw earlier. Moreover, indications are that the Boxer didn't match the O.S. competition in performance terms. The one joker in the pack could be price - although we have no information on the price of the Boxer 29 relative to its O.S. competition, it's possible that it undercut the O.S. product by a sufficient margin to secure a share of the domestic market, for a time at least. The Boxer .099 is undoubtedly a well-made and attractive little engine which functions well and looks as if it would give long and dependable service, but it doesn't come close to matching a typical competitor in the shape of the Mamiya. At 67 gm all inclusive (2.36 ounces), the Mamiya is 1½ ounces lighter than the Boxer and is both more compact and considerably more powerful. Any practical modeller facing a choice between the two designs would undoubtedly go for the Mamiya. Unless they enjoyed a significant price advantage over the competition, it's actually hard to see how the Boxer engines could have maintained a viable position in the Japanese model engine market. And indeed, they appear not to have done so - they were marketed for at most some five years, and possibly significantly less. Their extreme rarity today is ample testimony to their relative lack of sales success. A Later Boxer .099 Variant

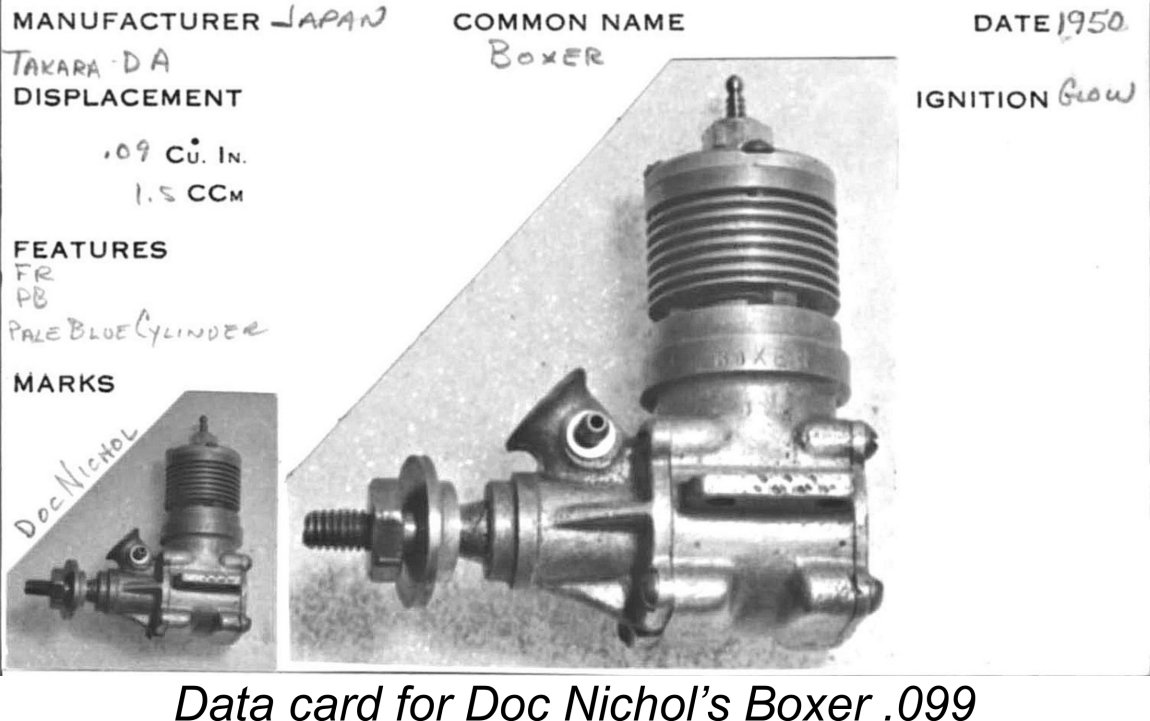

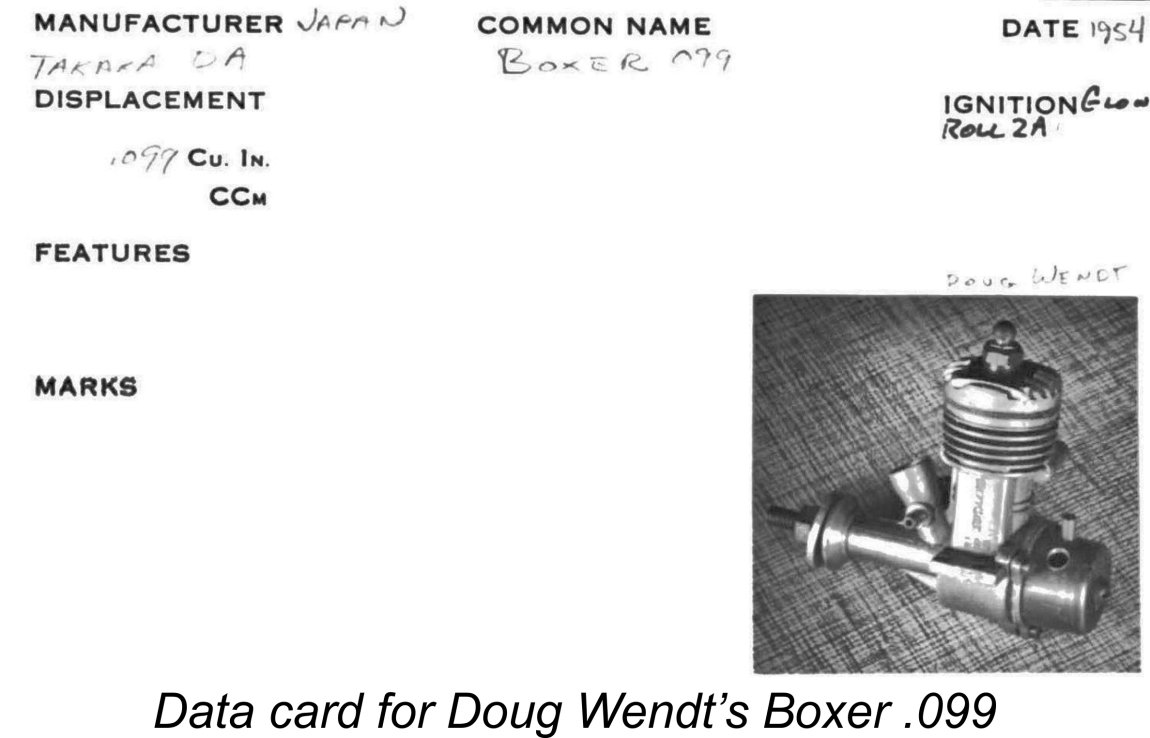

Firstly, my late and much-missed colleague Tim Dannels, to whom we all owe so much for his outstanding research into model engine history over the years, was kind enough to send along photos of a couple of data cards from his archives. These showed black-and-white images of a couple of Boxer .099 engines owned (or now perhaps formerly owned) by friends of his. The first of these was owned by Doc Nichol. It was clearly identical to the example described in detail above apart from missing the exhaust collector ring. However, The second image supplied by Tim was far more enlightening in that it showed a completely different Boxer .099 design! This one was owned by Doug Wendt, a long-time collector and MECA member with whom I completed many mutually-satisfactory trades. Another interesting piece of information was the provision of the maker’s name on the cards to which these images were attached. The name is rendered as "Takara DA" and the country of origin is given in both cases as Japan. Placing the constituents of this name in their English order yields the name D. A. Takara. This is not a name with which I’m familiar, and I leave it to others to follow up on this rather slim lead. However, the name is certainly consistent with the claimed Japanese origin of the Boxer engines. Unfortunately, the images made available by Tim are somewhat lacking in clarity, through no fault of Tim’s whatsoever. Hence I felt doubly blessed to hear from the .09 expert Dan Vincent (now deceased), who had recently sold a Boxer .099 of the later type on eBay (Drat! I missed it!). Happily, Dan retained some excellent images of this engine, so I’m able to present those images here as a record of what must surely be the final Boxer .099 model, likely dating from 1954. Since I don’t have access to the actual engine, I’m unable to supply any further details at this time. My most sincere thanks are due to both Tim and Dan for their invaluable assistance in helping me to tell the Boxer story as completely as possible. It’s responses like this that repay all of the hours that go into the preparation of these articles! Conclusion I hope that you've enjoyed this look at one of the more elusive Oriental marques from the early post-war period. If anyone out there can add to my knowledge or set me straight where I've gone wrong, please get in touch - all contributions gratefully and openly acknowledged!! ________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN September 2010 This revised edition published here April 2025 |

||||

| |

Due to the limited availability in Japan of both glow-plugs and the platinum-iridium wire needed to make them, Japanese makers were somewhat later than their American counterparts in fully embracing the glow-plug field. The first commercial Japanese glow-plug engines seem to have appeared in the marketplace in the latter part of 1948 as the plugs themselves became more generally available. O.S. did not enter the glow-plug field in a big way until 1949, when they released their twin-stack .29 cuin. glow-plug model which succeeded their earlier 1948 limited-edition sand-cast spark ignition .

Due to the limited availability in Japan of both glow-plugs and the platinum-iridium wire needed to make them, Japanese makers were somewhat later than their American counterparts in fully embracing the glow-plug field. The first commercial Japanese glow-plug engines seem to have appeared in the marketplace in the latter part of 1948 as the plugs themselves became more generally available. O.S. did not enter the glow-plug field in a big way until 1949, when they released their twin-stack .29 cuin. glow-plug model which succeeded their earlier 1948 limited-edition sand-cast spark ignition . Earlier, I mentioned the O.S. twin-stack sparker. The photos here show the subsequent glow version of the O.S. 29 twin-stack alongside the Boxer 29. Although there are a number of obvious styling differences, the similarities between the Boxer and O.S. .29 cuin. models seem too marked to be entirely co-incidental. The underlying designs bear a remarkable resemblance to each other, an impression which is confirmed by a detailed examination. The question immediately arises - in which direction did the influences flow? I'll offer a few speculative comments on this as I go through my description.

Earlier, I mentioned the O.S. twin-stack sparker. The photos here show the subsequent glow version of the O.S. 29 twin-stack alongside the Boxer 29. Although there are a number of obvious styling differences, the similarities between the Boxer and O.S. .29 cuin. models seem too marked to be entirely co-incidental. The underlying designs bear a remarkable resemblance to each other, an impression which is confirmed by a detailed examination. The question immediately arises - in which direction did the influences flow? I'll offer a few speculative comments on this as I go through my description. As can be seen, the two engines share a common crankcase layout with pressure die-cast cases featuring twin exhaust stacks and rather tall intake venturis for the front rotary valve (FRV) induction systems. However, the styling of the two models is quite different, with the Boxer using aerofoil-section stacks (widely favoured in Japan at this time) as opposed to the more American-influenced "rounded rectangular" shape used on the O.S.. The internal stiffening column which is cast into the O.S. stacks is absent on the Boxer. Moreover, the Boxer case is left "as cast" in contrast to the attractive

As can be seen, the two engines share a common crankcase layout with pressure die-cast cases featuring twin exhaust stacks and rather tall intake venturis for the front rotary valve (FRV) induction systems. However, the styling of the two models is quite different, with the Boxer using aerofoil-section stacks (widely favoured in Japan at this time) as opposed to the more American-influenced "rounded rectangular" shape used on the O.S.. The internal stiffening column which is cast into the O.S. stacks is absent on the Boxer. Moreover, the Boxer case is left "as cast" in contrast to the attractive

The head and base seals of my own example of the Boxer were both in very good condition with no detectable leaks, which made me reluctant to disturb them. I was also mindful of the fact that the cylinder fastening system with only two long screws is prone to introducing distortion when tightened down. When the cylinder is first tightened, it tends to take a "set" with some degree of microscopic distortion which is relieved through the break-in process. After the engine has settled down, as this well-used example clearly has, the original "set" is unlikely to be precisely duplicated if the cylinder is removed and re-tightened. Accordingly, the engine must in effect be run-in all over again, with unpredictable results.

The head and base seals of my own example of the Boxer were both in very good condition with no detectable leaks, which made me reluctant to disturb them. I was also mindful of the fact that the cylinder fastening system with only two long screws is prone to introducing distortion when tightened down. When the cylinder is first tightened, it tends to take a "set" with some degree of microscopic distortion which is relieved through the break-in process. After the engine has settled down, as this well-used example clearly has, the original "set" is unlikely to be precisely duplicated if the cylinder is removed and re-tightened. Accordingly, the engine must in effect be run-in all over again, with unpredictable results.

Looking at all of this, I personally feel that the Boxer is rather more logically seen as a derivative of the original O.S. spark ignition model than as a spin-off from the O.S. glow-plug design. The relatively thin mounting lugs, the screw-in backplate, the un-stiffened stacks, the treatment of the gudgeon pin, the slot-head screws and the sandcast head and backplate are all direct reflections of the O.S. sparker. Furthermore, the design of the Boxer case appears more consistent with the minimalist design philosophy mentioned earlier which was beginning to lose favour by 1949.

Looking at all of this, I personally feel that the Boxer is rather more logically seen as a derivative of the original O.S. spark ignition model than as a spin-off from the O.S. glow-plug design. The relatively thin mounting lugs, the screw-in backplate, the un-stiffened stacks, the treatment of the gudgeon pin, the slot-head screws and the sandcast head and backplate are all direct reflections of the O.S. sparker. Furthermore, the design of the Boxer case appears more consistent with the minimalist design philosophy mentioned earlier which was beginning to lose favour by 1949. That said, I’ve noted the possibility that the engines were in fact made elsewhere. If that possibility could be substantiated, it might be easier to rationalize changes of this nature. As it is, we presently lack any documentary or anecdotal evidence for a non-Japanese origin to balance that which we have in favour of such an origin.

That said, I’ve noted the possibility that the engines were in fact made elsewhere. If that possibility could be substantiated, it might be easier to rationalize changes of this nature. As it is, we presently lack any documentary or anecdotal evidence for a non-Japanese origin to balance that which we have in favour of such an origin. It's pretty clear from the architectural evidence that the introduction of the Boxer .099 model post-dated that of the Boxer 29 described earlier. The .099 is a far sturdier and more up-to-date design in a number of ways, displaying none of the minimalist design philosophy that was in evidence in the larger model. It also displays no design influence whatsoever from its larger sibling.

It's pretty clear from the architectural evidence that the introduction of the Boxer .099 model post-dated that of the Boxer 29 described earlier. The .099 is a far sturdier and more up-to-date design in a number of ways, displaying none of the minimalist design philosophy that was in evidence in the larger model. It also displays no design influence whatsoever from its larger sibling. The leaflet featured the Boxer .099 front and centre, claiming it as a "new standout model engine" which had both "excellent performance and style" and was "eminently suited to beginners". The quoted price of the engine, including shipping, was ¥1,270, which converts to a cost of US$3.55 at the prevailing exchange rate of ¥360 to the US dollar established under the American

The leaflet featured the Boxer .099 front and centre, claiming it as a "new standout model engine" which had both "excellent performance and style" and was "eminently suited to beginners". The quoted price of the engine, including shipping, was ¥1,270, which converts to a cost of US$3.55 at the prevailing exchange rate of ¥360 to the US dollar established under the American  The image on the Yuhido Corporation's leaflet shows that the Boxer .099 was originally supplied with both a metal back tank and a metal exhaust collector sleeve. Although the image is not in color, the tank in the image is clearly anodized, and it seems safe to assume that it was anodized red like the exhaust collector sleeve. Accordingly, the attached images of the sole example in my possession show the engine fitted with a modified OK Cub. .074 tank, which fits perfectly and looks more or less identical to the tank in the Yuhido image. At least it creates a far closer visual impression of what the engine looked like straight out of the box. On this used example, the exhaust collector ring has faded somewhat from heat—the tank color is probably close to the original.

The image on the Yuhido Corporation's leaflet shows that the Boxer .099 was originally supplied with both a metal back tank and a metal exhaust collector sleeve. Although the image is not in color, the tank in the image is clearly anodized, and it seems safe to assume that it was anodized red like the exhaust collector sleeve. Accordingly, the attached images of the sole example in my possession show the engine fitted with a modified OK Cub. .074 tank, which fits perfectly and looks more or less identical to the tank in the Yuhido image. At least it creates a far closer visual impression of what the engine looked like straight out of the box. On this used example, the exhaust collector ring has faded somewhat from heat—the tank color is probably close to the original. The Boxer .099 is basically a conventional radial-ported .099 cuin. glow-plug motor with one or two unusual features. One such feature in the context of the engine's time, place and displacement is the fact that it's a long-stroke engine. Measured bore and stroke are 12.40 and 13.50 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.63 cc (0.099 cu. in). The engine weighs 109 gm (3.85 ounces) all complete - a relatively hefty figure for a glow motor of its displacement.

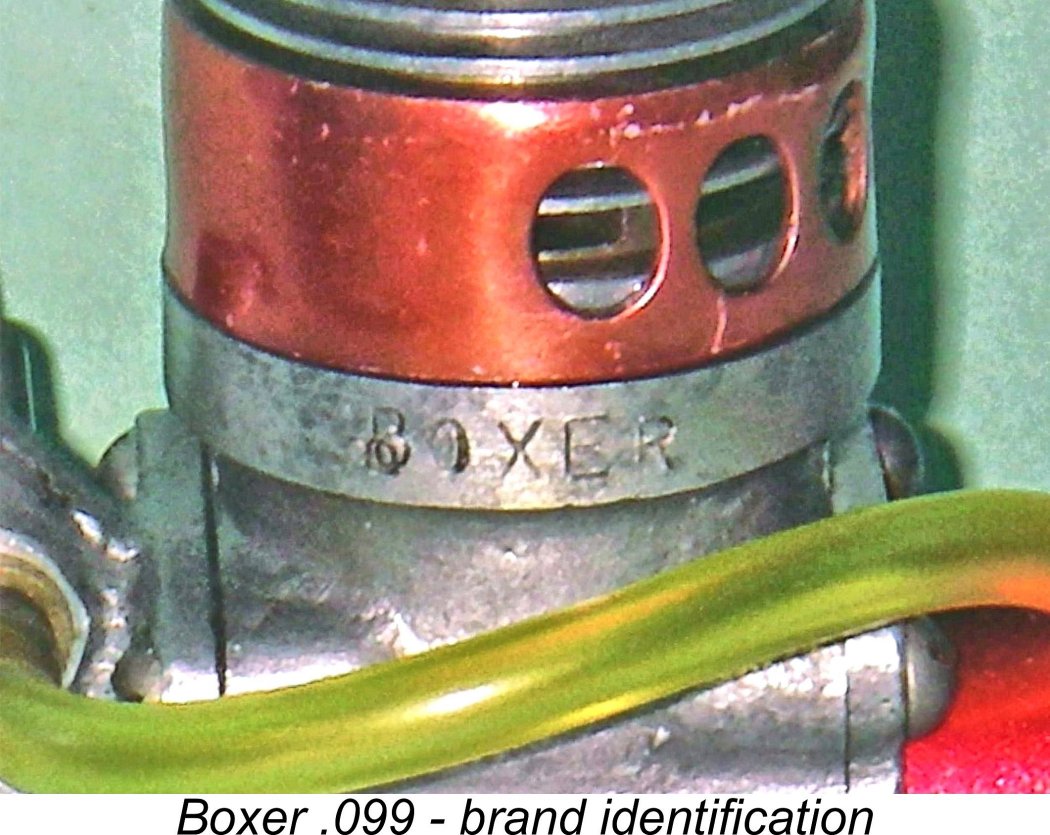

The Boxer .099 is basically a conventional radial-ported .099 cuin. glow-plug motor with one or two unusual features. One such feature in the context of the engine's time, place and displacement is the fact that it's a long-stroke engine. Measured bore and stroke are 12.40 and 13.50 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.63 cc (0.099 cu. in). The engine weighs 109 gm (3.85 ounces) all complete - a relatively hefty figure for a glow motor of its displacement. No marks of identification are cast onto the engine at any point. The only identification is the word "BOXER" stamped onto the left side of the integrally-machined location ring which forms the upper part of the main casting and accommodates the female thread for the screw-in cylinder. This stamping was clearly done by hand, since the "B" was initially mis-struck. There is no serial number, and once again the engine makes no claim to having been "Made in Japan".

No marks of identification are cast onto the engine at any point. The only identification is the word "BOXER" stamped onto the left side of the integrally-machined location ring which forms the upper part of the main casting and accommodates the female thread for the screw-in cylinder. This stamping was clearly done by hand, since the "B" was initially mis-struck. There is no serial number, and once again the engine makes no claim to having been "Made in Japan". simply by virtue of the excellent fit and fine machined finish. An unusual structural feature which should be noted at this point is the unusually short length of the slot-head hold-down screws - there are very few exposed threads to engage with the tapped holes in the case. This is not an engine for frequent dismantling or over-tightening of the screws! Fingers only, please.

simply by virtue of the excellent fit and fine machined finish. An unusual structural feature which should be noted at this point is the unusually short length of the slot-head hold-down screws - there are very few exposed threads to engage with the tapped holes in the case. This is not an engine for frequent dismantling or over-tightening of the screws! Fingers only, please. The front rotary valve is supplied with mixture through an early-'50's Enya-styled angled bell-mouth venturi which is cast integrally with the front bearing housing. Throat diameter is 5 mm for a rather fat spraybar having a diameter of 3.5 mm. Clearly the intent here was to promote good suction - a useful characteristic in a sports engine intended for beginners. There's little doubt that substantially more power could be released by judicious "waisting" of the spraybar, possibly at some expense in terms of handling qualities.

The front rotary valve is supplied with mixture through an early-'50's Enya-styled angled bell-mouth venturi which is cast integrally with the front bearing housing. Throat diameter is 5 mm for a rather fat spraybar having a diameter of 3.5 mm. Clearly the intent here was to promote good suction - a useful characteristic in a sports engine intended for beginners. There's little doubt that substantially more power could be released by judicious "waisting" of the spraybar, possibly at some expense in terms of handling qualities.  The bypass passages consist of three channels cast into the interior wall of the main casting. The design is in fact very similar to that of the

The bypass passages consist of three channels cast into the interior wall of the main casting. The design is in fact very similar to that of the  n the interests of making this review as complete as possible, I felt more or less duty-bound to undertake some test running. I had few qualms about doing this as far as the very sturdy Boxer .099 was concerned, but I admit to having been a little leery of putting too much of a strain on the Boxer .29! The example in question has clearly had a fair bit of use and has survived intact apart from a set of broken mounting lug "ears" which had been neatly repaired. I was a bit uncertain as to the integrity of these repairs, and as it turned out I was right to worry..........

n the interests of making this review as complete as possible, I felt more or less duty-bound to undertake some test running. I had few qualms about doing this as far as the very sturdy Boxer .099 was concerned, but I admit to having been a little leery of putting too much of a strain on the Boxer .29! The example in question has clearly had a fair bit of use and has survived intact apart from a set of broken mounting lug "ears" which had been neatly repaired. I was a bit uncertain as to the integrity of these repairs, and as it turned out I was right to worry.......... The Boxer .099 proved to be a very useable little engine, albeit not spectacularly powerful. It needed a small prime to start, but responded well when that was given and ran very smoothly indeed once speed was increased to above 11,000 rpm. Below that speed, there was a slight tendency towards a misfire which could not be entirely eliminated by needle adjustments. Overall, I gained the impression that the engine was somewhat asphyxiated by the very fat spraybar which blocked much of the intake area, and I have little doubt that "waisting" the spraybar would improve performance quite significantly. The engine certainly gave me the impression of wanting to give more.

The Boxer .099 proved to be a very useable little engine, albeit not spectacularly powerful. It needed a small prime to start, but responded well when that was given and ran very smoothly indeed once speed was increased to above 11,000 rpm. Below that speed, there was a slight tendency towards a misfire which could not be entirely eliminated by needle adjustments. Overall, I gained the impression that the engine was somewhat asphyxiated by the very fat spraybar which blocked much of the intake area, and I have little doubt that "waisting" the spraybar would improve performance quite significantly. The engine certainly gave me the impression of wanting to give more.

Fortuitously enough, it subsequently turned out that all was not lost in regard to testing a Boxer 29! While I was writing up this revised article on the Boxer range in early 2025, I was fortunate enough to have an unexpected opportunity to acquire a second example of the engine. This example had been well used, also having been modified to fit into a car, as a result of which it had a shaved intake venturi like the one illustrated earlier. It had also lost its tank - doubtless another result of its former car service. However, it remained in excellent running order, with adequate compression, little bearing wear and intact mounting lugs. Despite its cosmetic flaws, it would obviously make a very good test subject.

Fortuitously enough, it subsequently turned out that all was not lost in regard to testing a Boxer 29! While I was writing up this revised article on the Boxer range in early 2025, I was fortunate enough to have an unexpected opportunity to acquire a second example of the engine. This example had been well used, also having been modified to fit into a car, as a result of which it had a shaved intake venturi like the one illustrated earlier. It had also lost its tank - doubtless another result of its former car service. However, it remained in excellent running order, with adequate compression, little bearing wear and intact mounting lugs. Despite its cosmetic flaws, it would obviously make a very good test subject.  So into the test stand went the newly-acquired Boxer 29 with the 10x6 APC prop fitted. It felt really good when flipped over, seemingly all ready to go. I fuelled it up, opened the needle valve, choked to fill the fuel line, administered a healthy port prime, lit the plug, turned it over to feel the "bump" and then started flicking..........

So into the test stand went the newly-acquired Boxer 29 with the 10x6 APC prop fitted. It felt really good when flipped over, seemingly all ready to go. I fuelled it up, opened the needle valve, choked to fill the fuel line, administered a healthy port prime, lit the plug, turned it over to feel the "bump" and then started flicking..........