|

|

The Fuji Story – a Corporate Overview

The inevitable consequence of this has been a steady rise in the prices commanded by the earlier Fuji products and other contemporary Japanese classics. I clearly recall a time when these engines were more or less "give-aways", but those days are now over! Almost any 1950's-vintage Fuji which is complete and in anything like reasonable condition will fetch a price in the vicinity of $100 or more, with prices pushing well into the $200 range or even more for near-mint or NIB examples of the rarer early models. Even the 1960's models are generating increased levels of interest.

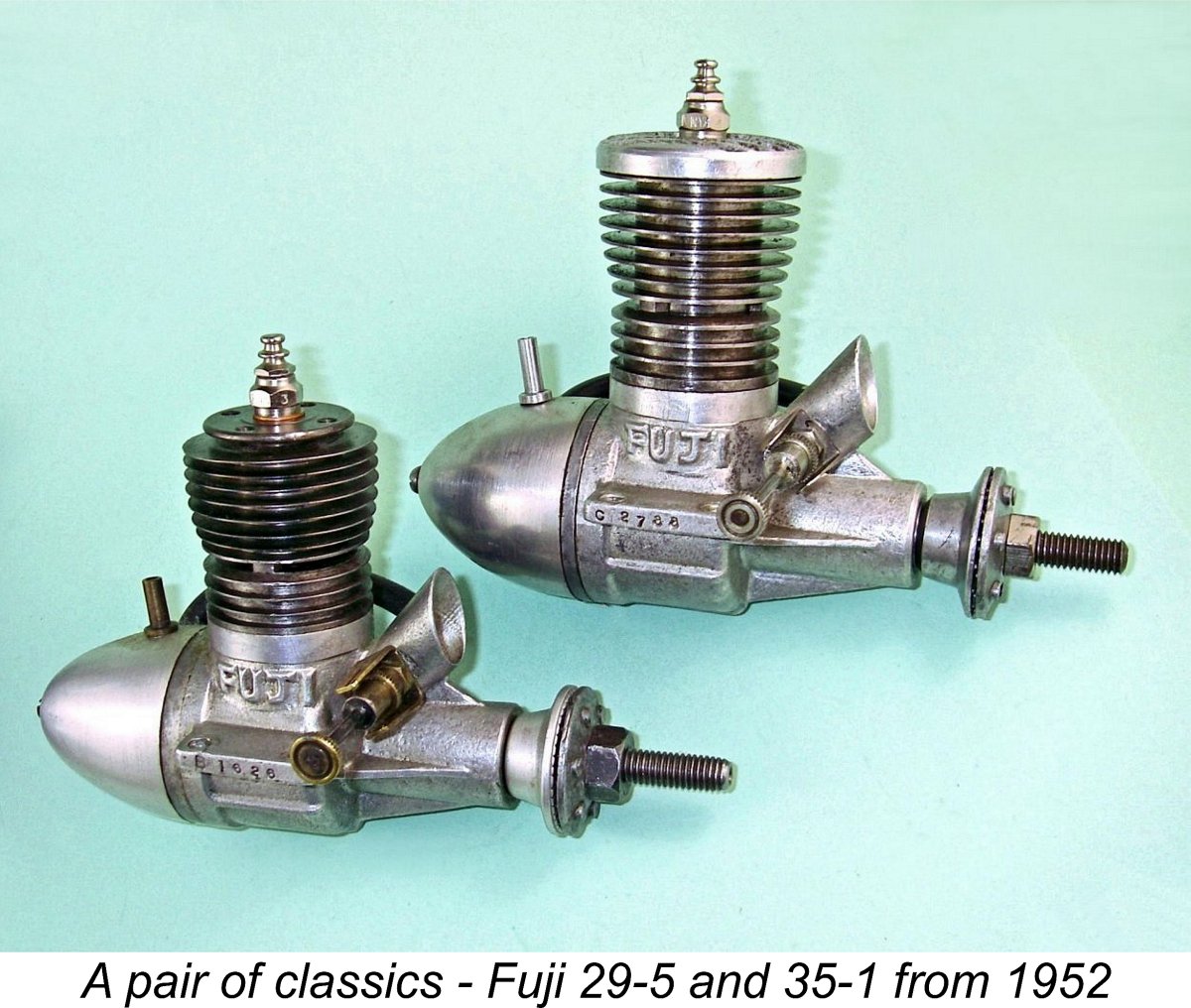

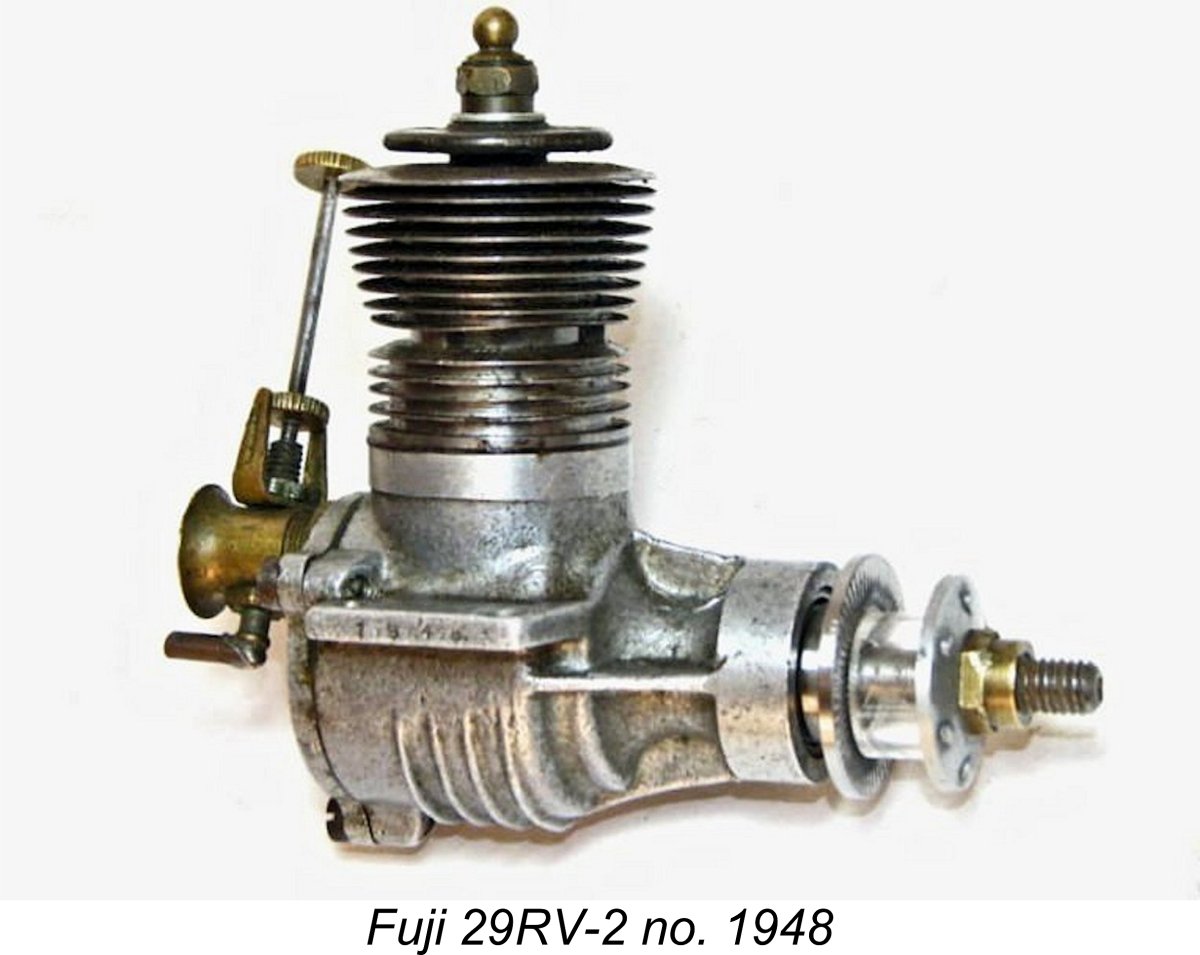

Consequently, the Fuji marque never quite matched the stature and market presence of its more famous Japanese competitors. Although the range attracted sufficient sales attention from the sport-flying community to survive well into the "post-classic" ABC/Schnuerle era which began in the 1970's, Fuji engines from the "classic" era of the fifties and sixties are considerably less common today outside Japan than other contemporary Japanese products, leaving the door open for supply and demand to exert their inevitable influence. Even in Japan, some of the earlier models like the illustrated 29RV-2 are extremely rare.

The final "selling point" which adds to the attractiveness of the early Fuji models is the fact that, in common with other contemporary Japanese ranges, the engines were very competently constructed despite their unpretentious exteriors and their relatively low selling prices. The early models may have lacked the external finish and design sophistication of some of their contemporaries, but from the outset they were very well made where it counted. Despite the challenges imposed by the limited availability in Japan of suitable materials during the early post-war years, the long-wearing qualities of the early Fuji's are legendary, and it's actually rare to find even a fairly well-used one that is anywhere near worn out. The quality of the engines was maintained and in fact steadily improved throughout the long life of the Fuji marque.

My original articles on the early history of the Fuji enterprise appeared as a series on the late Ron Chernich’s “Model Engine News” (MEN) website beginning in October 2011. I’m re-publishing those articles here partly to prevent their loss as Ron’s now-frozen and administratively-inaccessible site steadily deteriorates due to lack of any opportunity to maintain it, but also to take advantage of the opportunity to revise certain aspects of the respective texts to reflect additional details which have since come to light.

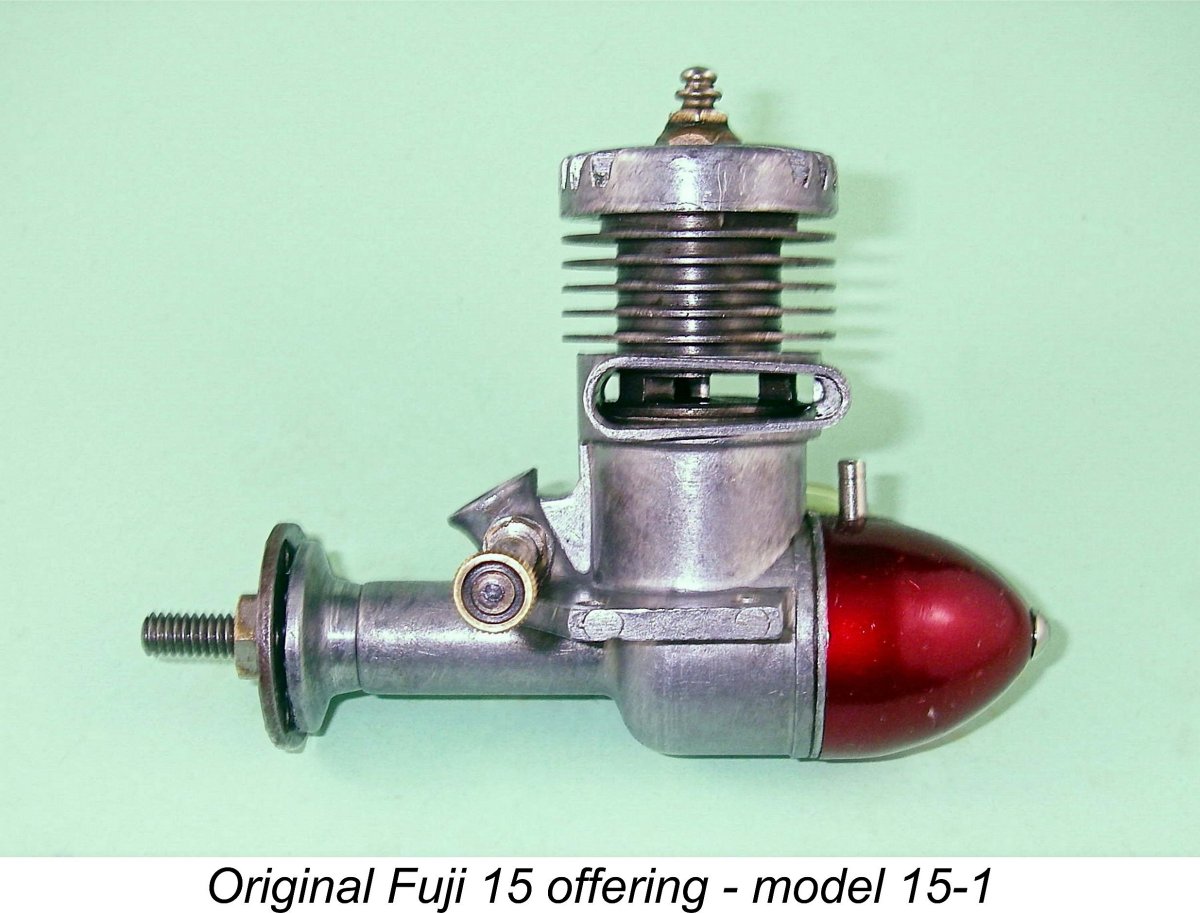

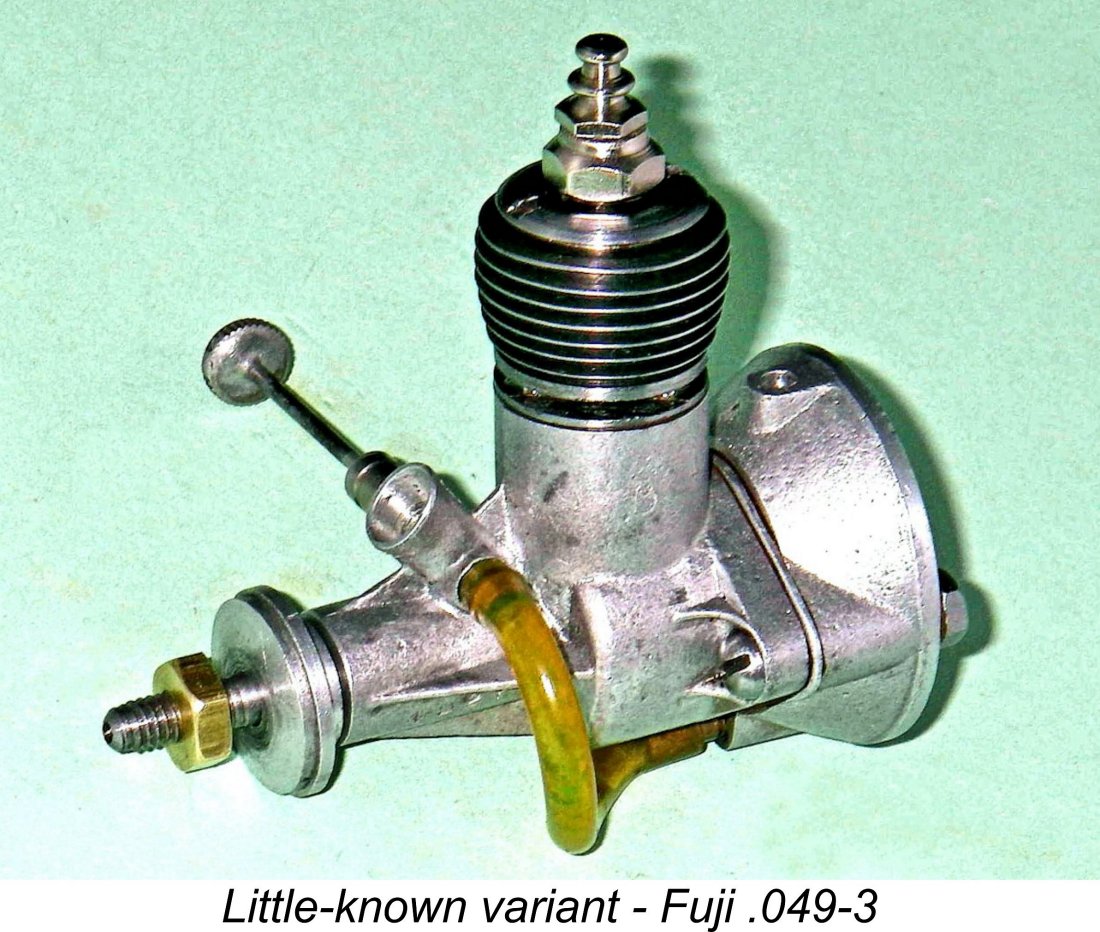

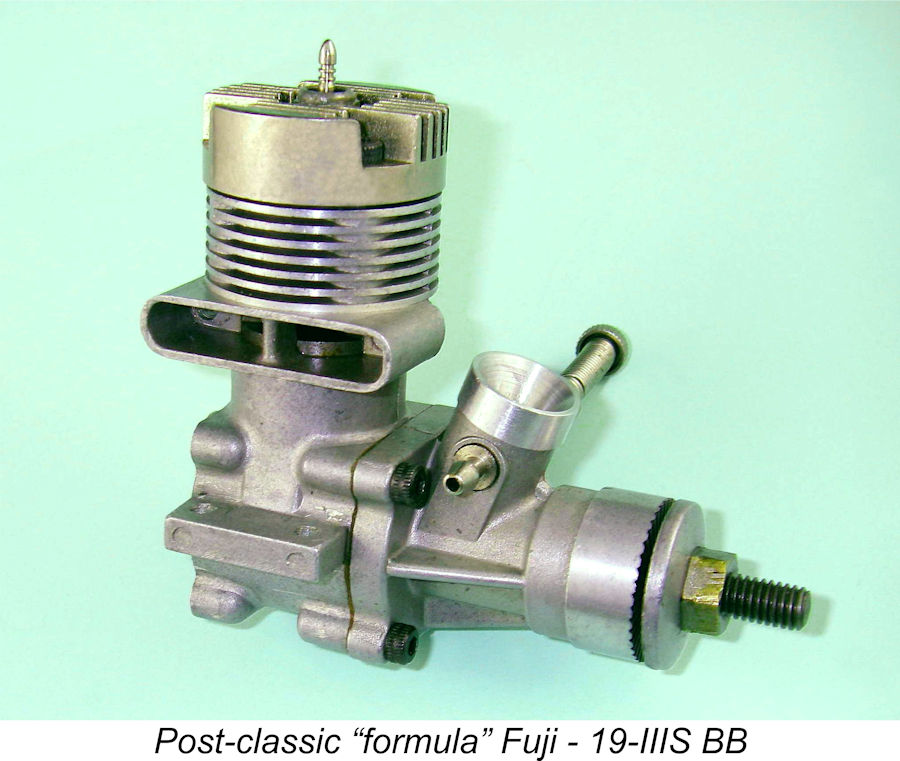

Secondly, I must acknowledge the ongoing support and unfailing assistance received from the late David Owen of Woolongong, Australia. David was indefatigable in researching serial numbers and providing images and other data from his own Fuji collection. Throughout our association, David never let me down, and he came through again in fine style on this occasion. Thanks, mate – I really miss you! Finally, having acknowledged the considerable assistance that I received during the writing of these articles, I must emphasize that the responsibility for any errors and omissions is mine and mine alone. Context and Scope In order to place my focused reviews of the various Fuji models in their proper setting, it's important that I clarify the context and scope of my efforts. I define the "classic" Fuji's as being those which used ferrous materials for their piston/cylinder combinations and which did not employ Schnuerle porting in any form. This period ended in the mid-1970's when Fuji introduced their "Inner Bypass Schnuerle" style of porting and began to use ABC piston/cylinder construction. At that point, the Prior to that point in time, there was a far greater diversity of design approaches among the various model engine manufacturers worldwide. The makers of the Fuji engines were major contributors to this diversity. It's that very fluid and inventive period in the history of model engine development that has always commanded my personal interest. Accordingly, my articles on the Fuji range are confined to the models which preceded those changes. I leave the documentation of the later models to others. I have also confined my attention for the most part to the model aero engines marketed under the Fuji banner. Although this was not readily apparent to observers outside Japan, the range of model products offered under the Fuji name was amazingly broad in scope, encompassing both aero and marine engines as well as specialty items such as glow-plugs, outboard motors, a range of model tether cars, a glow-engined R/C motorcycle and even a glow-engined "flying saucer"! Once again, I leave these products as research subjects for others. The balance of the present introductory article will summarize the background to the start-up of the Fuji model engine manufacturing business as well as its corporate evolution over the years. Those who merely wish to read about the Fuji engines themselves are invited to go straight to the various focused articles on the Fuji .049/.061 series, the Fuji .099 models, the Fuji. 15 series and the Fuji 29/35 models. Others, please read on............... Origins In common with most of the pioneering Japanese engine marques, the origins of the Fuji model engine line are rather obscured in the combined mists of time and Oriental inscrutability. There can be no doubt at all that the evolution of this range is well-documented in the pages of the post-war Japanese-language modelling media. However, until some kind soul takes pity on us who is fluent in both languages, has time on his hands and has ready access to such documents, we'll have to make do with what can be inferred from the relatively few references to be found in the English-language modelling press as well as what can be deduced from a close study of the engines themselves. The English-language modelling media offers very little help. The Fuji marque never achieved a high level of international brand recognition during the first decade of the "classic" era. Even thereafter, the Fuji range was generally (and perhaps justifiably) viewed as a second-tier "economy" range. Consequently, it was always of lesser interest to model engine commentators in the English language modelling media, at least during the period with which I’m concerned. There are references, but they are relatively few and far between.

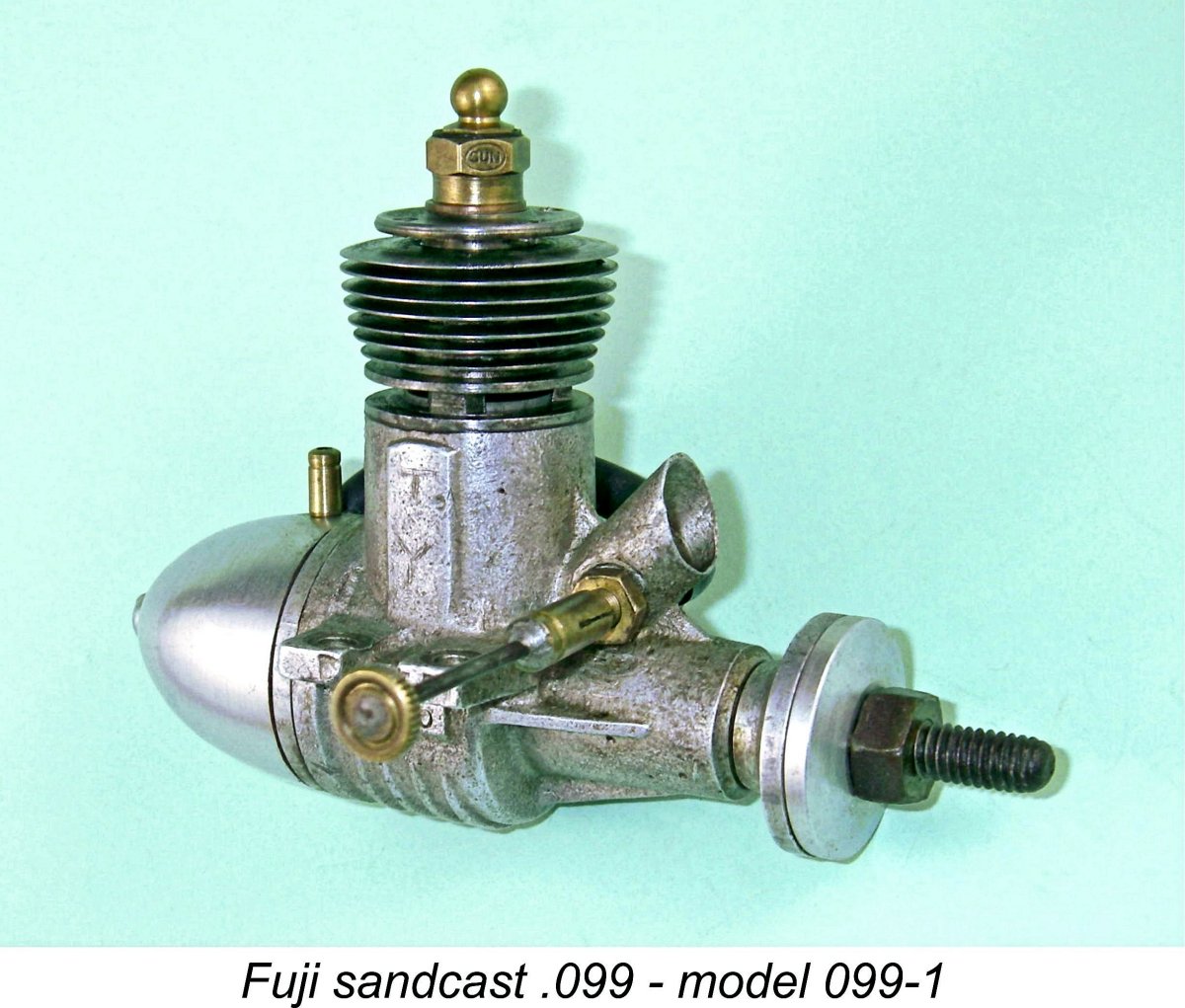

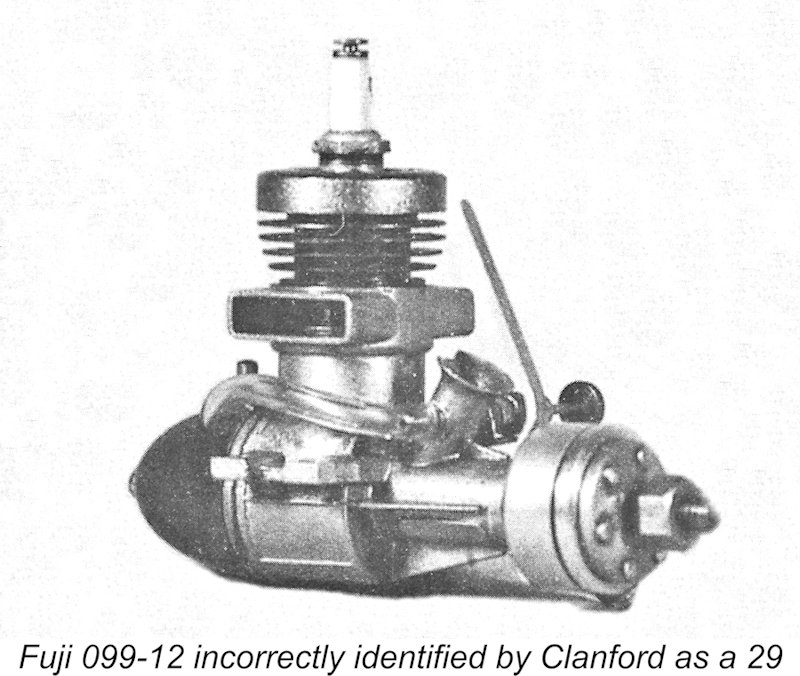

Fortunately, and perhaps not coincidentally, both of these authorities agree on the date. The Fuji page on the MECOA website is headed by the slogan "Fuji is an innovator of Model Engine design since 1949". The date The 1949 date is consistent with the fact that I’m presently unaware of any reported examples of an unquestionably original factory-made Fuji spark ignition engine, although later owner retro-conversions do exist - page 84 of Clanford's frequently unreliable book has created some confusion by illustrating just such an engine, which is incorrectly described as a 1955 Fuji 29 (it's actually a 1958 Fuji .099!). It would thus appear almost certain that the line originated after the commencement of the glow-plug era in 1948. The 1949 date is also consistent with what is known from other sources about the chronological evolution of the Fuji range. Hence there appears to be no basis for challenging the date in the MECOA slogan unless or until someone conclusively proves it to be wrong!

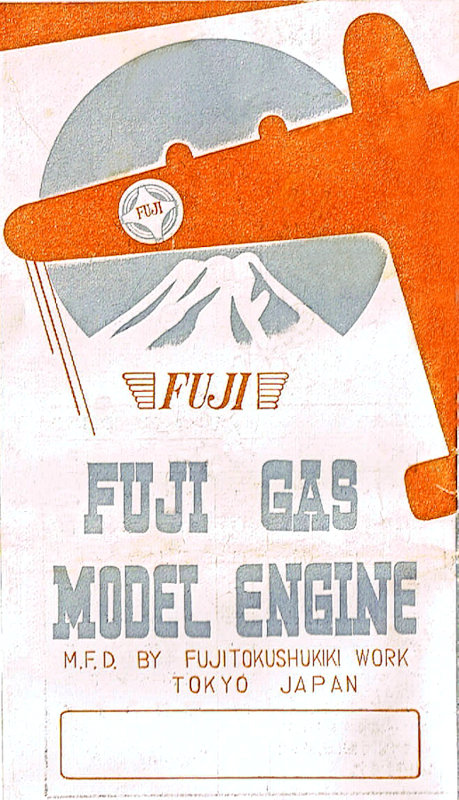

It thus comes as no surprise to find that the name is very commonly used by Japanese commercial enterprises wishing their name to impart a sense of quality to their products or services. There's even a highly-regarded Japanese apple that bears the Fuji name - one of my personal favorites! However it came into existence, it seems clear that the Fuji model engine line had its origins as a very small-scale manufacturing operation. Reports from Japanese sources have consistently indicated that the company's The earliest recorded company name attached to the Fuji engines was Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work. This name appears on some of the early engine boxes and leaflets used by the company (below right) as well as on at least one of their engines. Note also that a stylized "Mount Fuji" emblem appeared on these early leaflets - the manufacturers were clearly playing upon the name association with the famous mountain. This emblem also appeared on the crankcase castings of a few of the earliest Fuji models, although it was later dropped. By contrast, the "winged Fuji" logo which also appears survived up to the 1970's. The term "tokushu" means more or less "special" or "speciality" in Japanese, while the term "kiki" is broadly equivalent to "machinery". The company name thus translates into something along the lines of "Peerless Specialty Machine Shop". This name was to be associated with the Fuji engines until around 1954.

Mel Reid and I examined each of the above possibilities in turn. For those interested, the results are detailed in a separate section below dealing with the corporate history of the Fuji venture. For now, I'll confine myself to stating a few established facts as well as noting several matters which remain conjectural at present. First, we've seen that it seems to be an established fact that Fuji production commenced in 1949. However, uncertainty remains regarding the manner in which the venture got its start. Our investigations revealed that there is a demonstrable possibility (among others) that the early manufacture of the range may have involved engineers from one of the wartime aircraft factories which produced the famous Zero fighter among other aircraft. Indeed, this possible connection may provide a clue to the originality of design and simple but functionally effective construction of these engines. This possibility will be examined in its place below. We also know that by 1954, the Fuji model engine business was in the hands of the Fuji Bussan Co. Ltd, a name well-known to present-day collectors of Japanese engines with their colourful, readily identifiable boxes and quaintly-translated leaflets for the western market. However, a number of factors suggest that Fuji Bussan's core competence may have lain in sales and distribution rather than manufacture. Accordingly, the extent of Fuji Bussan's direct involvement in the actual production of the engines as opposed to their marketing remains unresolved at this point. We know for certain that at least one other company took on the manufacturing role at some indeterminate point in time, with Fuji Bussan retaining responsibility for marketing. These facts are likely well-known within Japan but appear to be far less so elsewhere. The above comments represent the briefest-possible synopsis of many hours spent researching the origins and corporate history of the Fuji enterprise. I’d urge any reader with an interest in such history to read the later section of this article since that section goes into far more detail regarding the results of our research on this topic. In particular, I would appreciate any and all authoritative additions to the story, especially from Japanese collectors who may be in a position to provide further information from the vantage point of their home country. Somewhere out there, someone knows a lot more than I do and I’m the first to admit that! The Early Post-War Japanese Modelling Scene

As of 1949 when the Fuji range appears to have got its start, the Japanese model engine manufacturing industry was very much back up and running again after the hiatus of WW2, with a surprising number of different manufacturers competing for a share of the market and more joining in all the time. A major catalyst for this post-war resurrection of the Japanese model engine industry was the presence of large numbers of predominantly US service personnel stationed in Japan as part of the Army of Occupation. This large superimposed group of temporary residents possessed purchasing power far in excess of that of the average Japanese citizen in post-war Japan. Japanese manufacturers in all sectors were quick to take advantage of the opportunities represented by this situation. As one would expect, a proportion of the US personnel stationed in Japan at this time were modellers in their free time. Accordingly, every US forces base had its own hobby shop attached to the base's service facilities. It appears that these shops were encouraged to market local products as part of the effort to assist the Japanese people to rebuild their war-shattered economy. This of course created a ready "overflow" market for Japanese-produced modelling goods, including engines. It also created opportunities for the establishment of personal relationships with Americans who might be influential in promoting or at least endorsing Japanese modelling products upon their return to the USA. Enya's first distribution deal in the USA arose from just such a contact, and O.S. also benefited greatly from a similar contact with the legendary Bill Atwood.

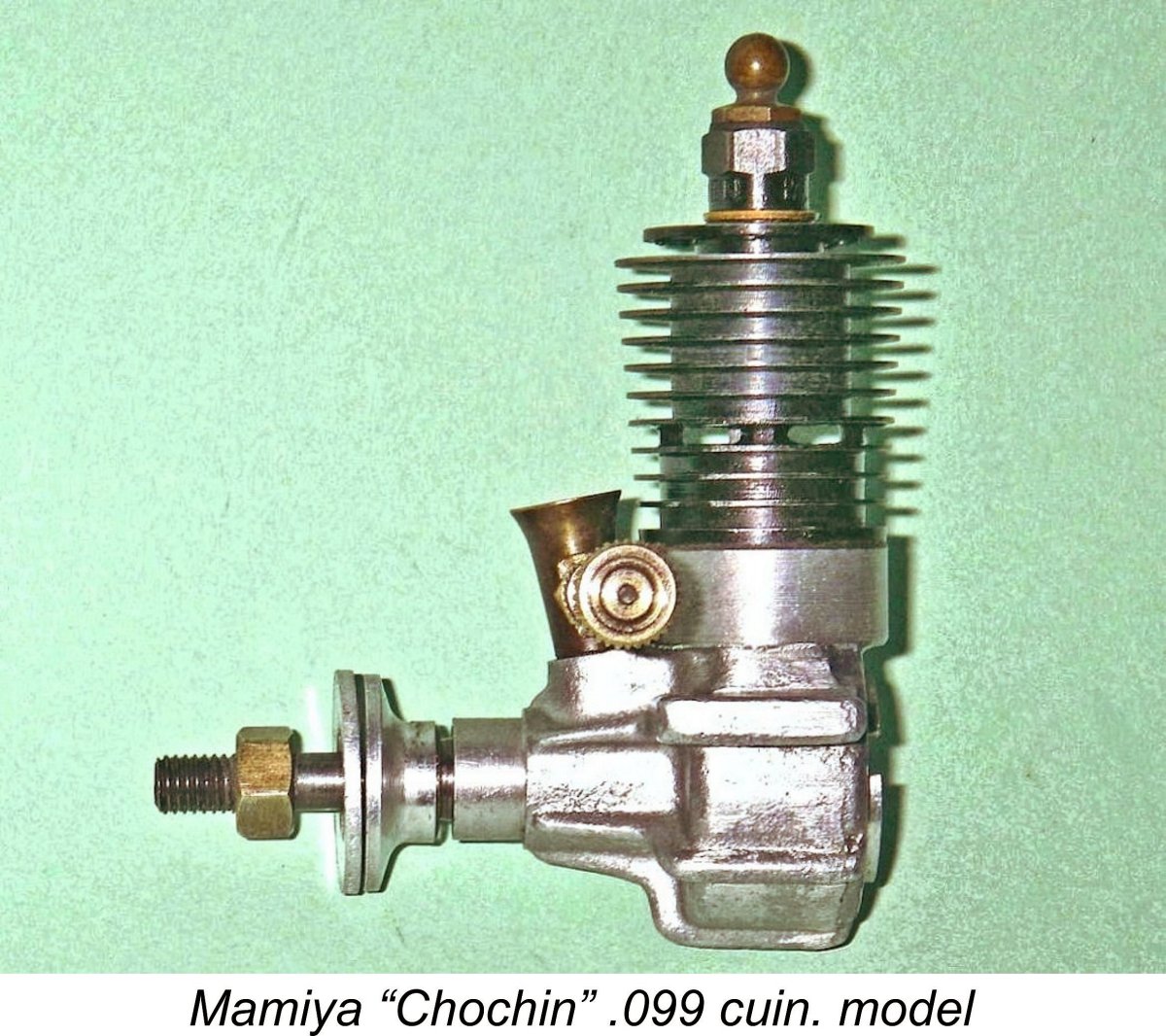

Apart from the Osaka-based manufacturers of the O.S. line and the far more obscure TOP range, essentially all of the name-brand Japanese model engine makers were based in Tokyo, where they But things were different in the latter half of the 1940's, and control-line flying at this downtown site was a weekly occurrence and something of a local "event" in those years. Apart from the regular testing and practise sessions that took place, the site was the venue for a series of major contests at which many of the competitors were American servicemen using the latest US-made engines and model designs. This gave the various fledgling Tokyo-based manufacturers such as the Enya brothers and the makers of the Fuji, Mamiya, Hope and KO ranges every opportunity to make contact with and fly against American modellers, study American equipment, research American modelling preferences and design approaches and learn from their observations. Time was to show that they learned well ................ At the time when the Fuji range first became established, the other companies mentioned above were for the most part focused on the mid-sized and larger displacement categories of .19 cuin. or greater. This left the door wide open for another Japanese company to enter the marketplace with a simple and compact smaller-displacement model suitable for general-purpose sport flying which could be sold at a lower price than the larger and more complex engines and for which models could be built and operated more easily, cheaply and quietly.

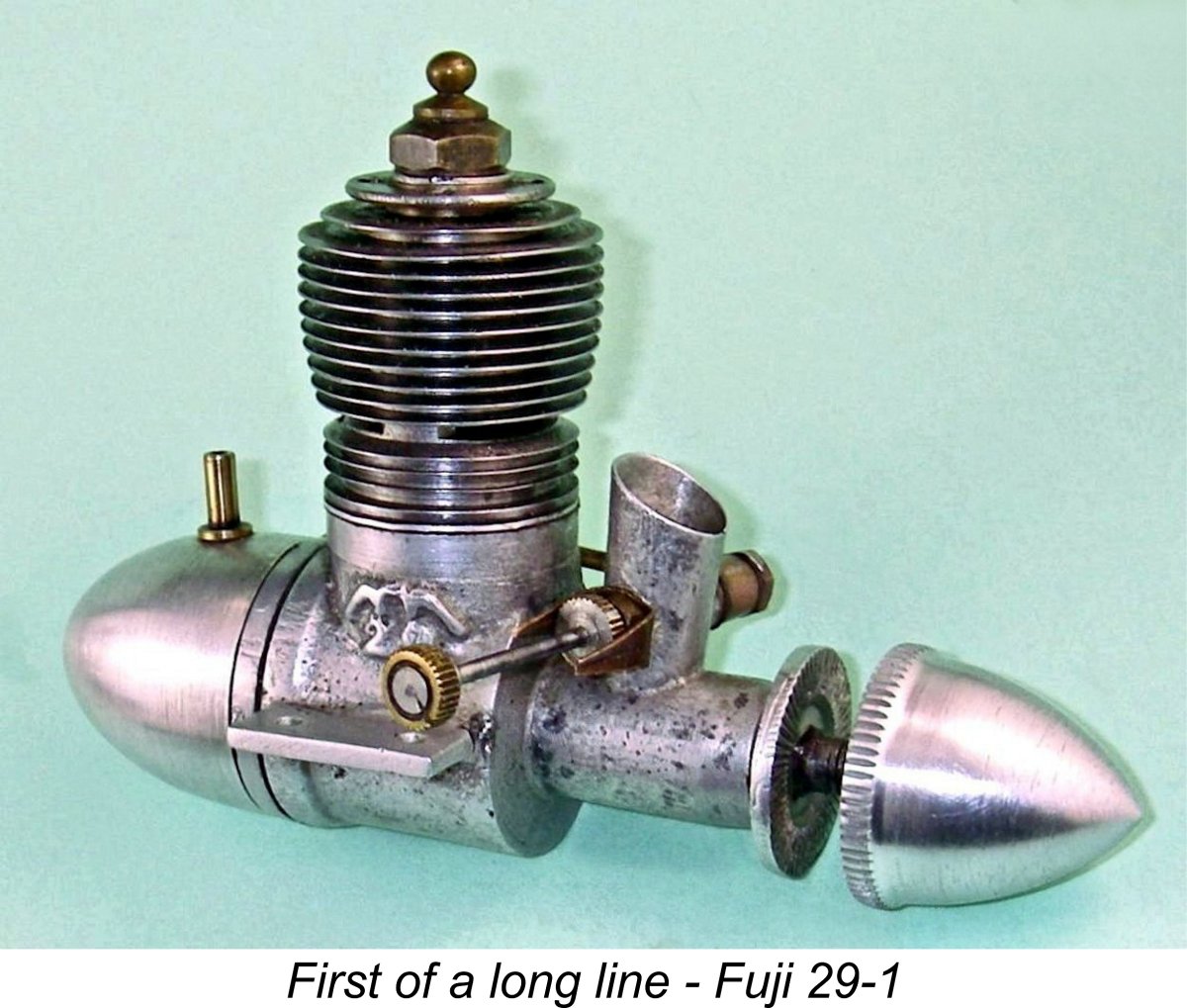

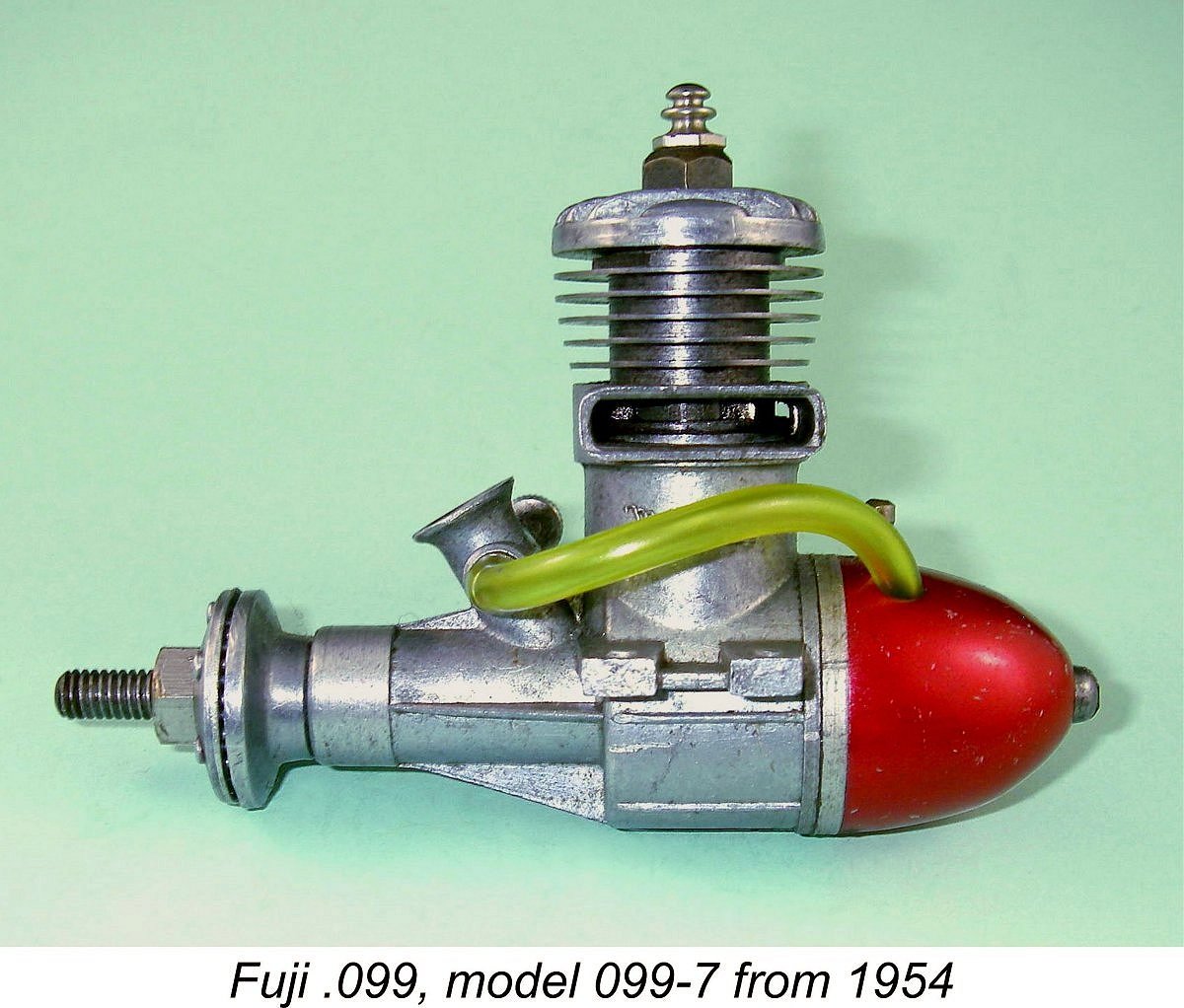

The makers of the Fuji range had first entered the market with a .29 cuin. offering, but lost little time in following the Mamiya lead in 1949 with the first of their own long line of .099 cuin. models. This proved to be a sound decision - although O.S. and Boxer soon entered the market in 1950 with .09 models of their own, the Fuji .099 faced relatively little domestic competition in its displacement category at the outset, thus getting a good head start in the marketplace. Even after O.S. and Boxer entered the category, the market was readily able to absorb the start-up production from all four companies. Moreover, further competition was relatively slow to appear. The Kondo brothers' twin-stack KO .099 glow-plug model did not appear on the scene until late 1953. Enya delayed even longer - they waited until May 1954 to introduce an .099 cuin. model of their own. Hope followed suit soon thereafter. As events were to prove, that initial Fuji .099 model helped to lay the foundations of a long-lasting and ultimately successful model engine manufacturing business. Much more of the Fuji .099 models in a separate article to be found elsewhere on this website. Fuji Production Commences

During the initial production period starting in 1949, Fuji's monthly production figures were undoubtedly quite low. This is consistent with the fact that the earliest Fuji's feature sand-cast crankcases and do not carry particularly high serial numbers - certainly nowhere near five figures. Presumably at the outset the fledgling company lacked the required combination of established consumer demand, technical expertise and financial capability to engage in the production of the rather intricate pressure die-castings for which their products were to become notable in later years. Over the years, Fuji were extremely prolific producers of different models in the various displacement categories with which they were involved. For example, there were to be no fewer than seventeen distinct Fuji .099 cuin. models during the "classic" era. Keeping track of all the different models will be very important as we proceed to evaluate the various displacement categories with which Fuji became involved. Accordingly, before undertaking any detailed evaluations of the various Fuji designs it seems worthwhile to pause at this point and consider the important question of model identification. Model Identification One factor which has greatly assisted my research is the fact that from the outset all "classic" Fuji engines carried serial numbers. There was no particular system involved - the engines sharing a given displacement and design configuration were simply numbered sequentially starting from 1 as they came off the line. The numbers appeared in various locations on the engines. When the design configuration was altered significantly, the sequence was generally re-started from 1. Hence there were duplicate numbers within all of the various displacement categories in which Fuji competed, as well as duplicate numbers between engines belonging to different displacement categories. The secure identification of a given engine thus requires that the serial number, the displacement and the particular design configuration within that displacement series all be known. In some cases a letter prefix was added in front of the serial number, sometimes apparently without restarting the numerical sequence. The full significance of this is not presently understood, but it appears to have been used to distinguish between specific production series, perhaps when a minor design or production change was made that needed to be highlighted in case of a request for spares or service. While the serial numbers are extremely useful indicators, they were unfortunately not accompanied by any other means of model identification. Unlike Enya and O.S., who very quickly began to assign model numbers (Enya 09 Model 3001, etc.) or series numerals (Enya 19-IV, OS Max-II 15, etc.) to distinguish their various design evolutions, Fuji continued throughout much of the "classic" era to identify their engines simply by the Fuji name and the displacement. When a given design changed substantially, they re-started (and/or letter-coded) the serial number sequence, but the engine's name remained unaltered. It was only in the mid-1960's that Fuji began to follow the lead of their competitors by applying a series numeral to their engines. Naturally, this creates difficulties both for the researcher and the reader in remaining clear at all times regarding which particular model is under discussion at any given time. When one considers that there were no fewer than 17 variants of the Fuji .099 during the classic era and that all but three of these were simply called the Fuji .099, one may begin to appreciate the problem! Accordingly, it appeared to me that the establishment of some kind of identification system would be of great benefit to collectors of these engines. The numbering system established by the late and much-missed Tim Dannels in the Engine Collector's Journal for the McCoy range, for example, has been of the greatest service to collectors of those engines, being in common use worldwide. For this reason, I have assigned model numbers to each of the variants to be described in my focused articles on the various Fuji series. It's crucial to note that these numbers are mine, not Fuji's, and are assigned purely for convenience in specifying the model(s) to which reference is being made. The assigned numbers indicate the displacement followed by the chronological position of the variant in question within the design sequence of models having that displacement. To take a couple of examples, model number 099-4 identifies the fourth variant in the Fuji .099 cuin. series. Similarly, the 29-2 designation denotes the second variant in the Fuji .29 cuin. sequence. Having set the scene and established my study parameters, I’m ready to direct my readers’ attention towards my detailed examinations of the various Fuji models. But before doing so, it may be helpful to those readers having an interest in such matters to take a little time to review the somewhat convoluted corporate history of the Fuji venture. If nothing else, this will help to make sense of the various company names which appear on the boxes and in the leaflets. Readers having no interest in this topic are cordially invited to proceed directly to my separate articles on the various engine series which appeared under the Fuji trade-name. Links to those articles will be found at the bottom of the present article. The Fuji Venture – Corporate History The corporate history of the manufacturers of the Fuji range is unusually complex as well as being greatly obscured by a combination of time and language barriers. Sorting it out from locations outside Japan and without any fluency in the Japanese language has proved to be a daunting task at best. In writing about this topic, I'm very mindful of the probability that the majority of my readers will have no interest whatsoever in the corporate background to the manufacture of the Fuji engines. Viewed in that light, some might think that I'm wasting my time. In my defence, I will only say that even if no-one reads it, the material is at least preserved and made available to be read if desired. No-one will have to go through this exercise again in the future! Indeed, doing so may become impossible as time passes. Moreover, the nature of the subject matter does not readily lend itself to the use of illustrations to make the account more readable. Consequently, I already hear a chorus of voices saying "To heck with all this bureaucratic BS - let's get to the engines themselves!". All those harbouring such thoughts are hereby cordially invited to proceed directly to my companion articles on the various Fuji model engine series – I won’t be offended! For the rest, please read on.......... The account which follows has been derived from a combination of close scrutiny of a variety of Fuji leaflets and labels together with the extraction of as much corporate information as possible from various data sources primarily accessed through Google Japan. For the latter effort, the main credit is due to my English colleague Mel Reid, who has worked tirelessly in this area of research. If there is a reader out there who is fluent in Japanese and is willing to provide further assistance, I’d be immensely and openly grateful! Mel and I felt that we'd gone as far as we could without such assistance. The sequence of corporate entities which guided the fortunes of the Fuji range seems reasonably clear. However, I acknowledge that many of the fine details such as dates and precise roles/relationships remain obscure, thus leaving ample scope for further research. I hope very sincerely that others may feel inclined at some point to take up this challenge, setting me straight where I've gone wrong! In the present article, I'll set out what Mel and I have been able to deduce from the limited amount of information available to us from where we sit. We would be delighted if this served as the groundwork for others possessing a closer knowledge of the facts or having both the time and opportunity for further research to add their insights to ours. As it is, I'll just do the best that I can to present our findings to date. The leaflets and box labels associated with the earliest Fuji products make it abundantly clear that the original manufacturer of the range was the previously-cited Tokyo-based company known as Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work. I previously noted several references which give the date of the commencement of Fuji production as 1949. Given the fact that there is currently no evidence that Fuji ever produced any spark-ignition models, there seems little reason to question this date unless further persuasive evidence comes to light. Origin of Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work The question of the origin of the Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work company is one that remains very much open to debate. The problem is that there is currently very little evidence upon which to base such a debate! There appear to be three broad possibilities:

It is an undeniable possibility that Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work was established from scratch in 1949 as an entirely new small-scale company. This is certainly consistent with the fact that production figures during the first few years appear to have been relatively small. Unfortunately, Mel Reid’s extensive search of Japanese corporate data which were available on line failed to turn up any record of a company of this name being established at the right time. Hence there is currently no evidence whatsoever to support this possibility.

Another plausible scenario would be for the manufacture of model engines to have been added to the business portfolio of an established company already engaged in some other line of work. To test this possibility, Mel Reid undertook an exhaustive search of Japanese companies called Fuji Tokushu Somethingorother. The most promising candidate was a present-day company called Fuji Tokushu Corporation which was established in Tokyo in 1938 for the purpose of making air conditioning systems and "specialty products" (hence the term "Tokushu" in the company name). Although there is at present absolutely no direct evidence, it is possible that the Fuji model engine venture was a sideline or an offshoot of this company. There are doubtless other companies which might be connected in this way - we simply don't know.

The early post-war Japanese business community underwent a series of significant upheavals as the country attempted to gain control of a highly unfavourable economic situation and restore confidence in the Japanese business community. A number of major industrial conglomerates became fragmented as a result. It is possible that the Fuji model engine enterprise may have begun during this period as an independent offshoot of a larger company. Mel Reid's research identified several possibilities in this context. One was the Fuji Electric Company, which was established in 1932 and is still operating today. As well as motors, generators, etc., the company makes pumps and compressors. More interestingly, it has been possible to confirm that they did at one time have a subsidiary called Fuji Tokushu! However, Mel was unable to find any information about this latter operation beyond its name. Consequently, there is no direct evidence at present to support this possibility. Another potential candidate is Fuji Precision Industries, which arose from the ashes of WW2 as a result of a 1945 restructuring of the former Tachikawa Aircraft Co. This company had manufactured Zero fighters and other military aircraft during WW2 but was forced to divert its capabilities into non-military production following the conclusion of the war. That did not alter the fact that it was unquestionably an air-minded company possessing the technical expertise to design and manufacture model aero engines. The Case for a Possible Tachikawa Connection The only one of the above possibilities for which a cohesive circumstantial argument can presently be developed is the last-mentioned, namely the Tachikawa connection. Since this is a fascinating tale in itself which throws considerable light upon the effect of WW2 upon Japanese industry in general, it seems well worth setting down here since if nothing else it may help to clarify the business climate within which the Fuji model engine manufacturing enterprise was established. However, I must caution my readers that the evidence is entirely circumstantial. Consequently, this connection cannot in any sense be regarded as substantiated. Moreover, honesty compels me to admit quite freely that in the context of an examination of the Fuji model engine range, the origin of the Fuji Tokushu Kiki company is really of academic interest only. Accordingly, those wishing to skip this line of entirely circumstantial argument are invited to move directly to the following section of this article. For the rest of you, I’ll share what Mel and I learned.

In 1936, the Imperial Japanese Army acquired a controlling interest in the Ishikawajima company, renaming it the Tachikawa Aircraft Company Ltd. This company manufactured a number of aircraft types, mostly training models and fighters for the Imperial Japanese Army. Some of these were in-house designs which were put into full production, while a number of others were either short-run specials or prototypes that did not enter production. It came as something of a surprise to us to learn that in 1940, the company received license-production rights from its future American adversaries to the Lockheed Model 14 Super Electra, which Tachikawa produced as the Army Type LO transport. Tachikawa also produced aircraft designed by other Japanese manufacturers.

It's an intriguing and undeniably attractive possibility that the same expertise that went into the Zero may possibly have been applied to the manufacture of the Fuji model engine range! Let's look at the circumstantial case that can be made for this scenario. The full-scale aeronautical manufacturing activities of the Tachikawa Aircraft Company were ended by the terms of the Japanese surrender to Allied forces in August 1945. The Tachikawa Aircraft Company and its fellow Japanese aircraft manufacturer the Nakajima Aircraft Co. were both dissolved and merged into a new entity known as the Fuji Sangyo Corporation. Unable to continue any involvement in the aircraft industry, this new organization very shrewdly based its business plan upon meeting the fundamental ongoing needs of the Japanese people in the foodstuffs and transportation sectors, beginning immediately to diversify into a number of different subsidiaries focused upon non-aviation fields. Although its production facilities had suffered extensive damage during WW2, much of Tachikawa's very considerable technical expertise remained at the disposal of the new conglomerate. As part of the above-noted restructuring, the staff of the former Tachikawa Aircraft Company were re-deployed within a new subsidiary known as Fuji Precision Industries. Management immediately began to search for other forms of manufacturing to which their capabilities could be applied.

Following a fairly lengthy development period, commercial production of Tama electric cars commenced in 1947, with three versions being produced - the E4S-47 and the "Junior" (both 4-seaters) and the 5-seater "Senior". The range of these vehicles at their economical cruising speed of 35 km/hr was around 65 km on a single charge. In 1950, changes in Japanese corporate legislation forced the formal disassociation of Fuji Precision Industries from the Fuji Sangyo Corporation, but this had little or no effect upon the former subsidiary's activities. Following their initial success with the Tama electric automobiles, the company commenced the development of their own conventional automobile engine and entered the field of conventional automobile At around the same time, the company adopted the name Prince Motor Company. Under this name, it became highly respected for its range of premium-quality automobiles. The organization possessed a level of engineering and technical expertise which was then unrivalled in Japan, largely because of the wartime aircraft production and engine development background of its technical staff. Prince Motors eventually merged with Nissan Motors in 1966, thus making Prince's outstanding technical capabilities available to Nissan. Returning to the early post-war years, the ban on Japan's involvement with full-scale aircraft production ended in November 1949. The fact that Fuji Precision Industries had never lost its leaning towards involvement in the aviation industry is clearly demonstrated by the fact that immediately following the lifting of the ban, the company returned to its roots by establishing a subsidiary called the New Tachikawa Aircraft Company Ltd. The reconstituted full-size aircraft manufacturing venture was not however a long-term commercial success, and by 1955 the company had ended its involvement with the full-scale aviation industry once and for all. Given the nature and scope of the above activities, it must surely be obvious that as of 1949 the manufacture of model engines would have appeared commercially inconsequential to Fuji Precision Industries. Accordingly, if the Fuji Tokushu Kiki company was indeed an offshoot of Fuji Precision Industries, then its establishment must surely have been as much a labour of love as anything else. Perhaps a former Tachikawa employee within the parent company simply wished to resume a connection with aero engines, regardless of the scale. It's an attractive notion ................

There are parallels even in Japan for the establishment of model engine lines as offshoots of far more significant companies having nothing to do with modelling - the Mamiya range, for example, was manufactured by a completely independent offshoot of the prestigious Mamiya camera company founded by a former Mamiya Further research might well confirm or refute the existence of the connection just discussed. I do not claim it as an established fact - rather, I simply point it out as a credible scenario and a possible avenue for further research. My presentation of the above case here must not be taken to imply that I’m necessarily convinced by my own arguments - it's simply that this is the only one of a number of possible scenarios which can be argued at all on the basis of present evidence. I'll argue the others just as strongly if any evidence becomes available in the future! Having gone through the above unproven scenario in some detail, I will now attempt to trace the various corporate changes which influenced the fortunes of the marque from 1949 onwards. The Fuji Bussan Connection The manufacture of the Fuji engines by Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work evidently continued from 1949 through to 1954. Throughout this period there appears to have been a notable lack of sophistication in the company's marketing efforts, particularly in terms of overseas sales. It appears that they were sufficiently occupied in developing and manufacturing the engines, while the relatively small scale on which manufacturing seemingly took place at this time meant that finding domestic buyers for their output presented far less of a challenge than it would have done for a larger-volume producer. Basically, at this stage the venture was technically-driven rather than being sales-oriented.

Fuji began experimenting with the use of die-casting (as opposed to sand-casting) in 1950, phasing in this technology progressively over time. Their first model based entirely on die-cast components was the .29 cuin. Silver Arrow of late 1952. By mid-1953 their .099 cuin. model had also been switched over to die-casting. Most of the leaflets which came with the engines prior to 1954 appear to have been in The name "Fuji Bussan" translates very roughly into "Fuji Products", which is completely consistent with the companies' business activities. Under Japanese corporate law the KK and Co. Ltd. company registrations were (and are) entirely distinct. The "KK" form of company registration had been in existence for many years, having first been used in 1873. The letters stand for "kabushiki kaisha", which pretty much translates into "stock company", thus being more or less synonymous with the familiar term “corporation” in America (in Britain, a publicly listed company (plc), or Akitengesellschaft (AG) in Germany). This form of registration required the posting of a very substantial bond as well as the use of a registered trade-mark, but it did allow the company to trade its stock on the open market. By contrast, the "Co. Ltd." form of company registration was relatively new, having been introduced shortly after the conclusion of WW2. This step was possibly motivated by the greatly increased level of interaction with Western society in general, but it's perhaps more likely that it was intended to provide smaller Japanese businesses with greater flexibility during their start-up and expansion phases. The revitalization of the Japanese economy was the primary challenge at this time, and the new registration option was doubtless intended to encourage small-scale entrepreneurial activity. This form of registration had far lower bonding requirements as well as limiting the company's liability, the downside being that there were severe restrictions upon the company's ability to raise outside capital. It was perhaps best suited to small family-owned operations - the Enya Metal Products Co. Ltd is a familiar example. Given the above facts, the two distinct registrations would appear at first sight to imply that Fuji Bussan KK and Fuji Bussan Co. Ltd. were separate corporate entities. However, this cannot be taken for granted by any means - it is entirely possible that the two companies were in fact one and the same! Odd though this may seem, it appears that under Japanese corporate law there was nothing to stop a KK registered company from representing itself as a Co. Ltd organization in a promotional context. This might be seen as an advantage for markets in which such a representation would be more comfortably familiar. There are actual precedents for this approach being taken. Even if this were not the case and the two Fuji Bussan entities were in fact distinct, both the coincidence of names and the common focus on the Fuji model engine range make it all but certain that the two Fuji Bussan entities were directly related, with one most likely being a subsidiary of the other. Based upon his own extensive career involvement with the British corporate sector, Mel Reid thought it most likely that the KK firm would have been the parent company while the Co. Ltd entity was the subsidiary. It is apparently common practice in Britain to have a plc company owning a number of Ltd companies which do the actual work while the parent company checks the books and reaps its share of the profits. It may well be that the same practice was followed in the case of Fuji Bussan - we simply don't know at this point. However the two entities were related and regardless of their respective roles, there's no question whatsoever that it was from this point onwards that we see a greatly increased level of concern with the marketing of the engines as opposed to merely their manufacture. There's no doubt at all that the Fuji Bussan organization entered the picture with marketing ambitions which extended well beyond Japanese shores. Their advent coincided with a significant upgrading and Anglicization of Fuji's packaging, while leaflets with engines destined for overseas markets were now also printed in somewhat clumsy English. These moves reflected a sincere effort to market the engines world-wide for the first time. At present we have absolutely no evidence regarding the extent to which Fuji Bussan was involved in the manufacturing of the engines as opposed to their marketing. The complete disappearance of Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work from the record makes it appear most probable that Fuji Bussan took over both the manufacturing and marketing from Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work, establishing manufacturing and marketing divisions within their own corporate structure. However, the possibility can't be completely discounted that Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work carried on in the background as the manufacturer, at least for a time. Alternatively, they may have been reorganized as the "Co. Ltd." partner to continue their manufacturing role, while the "KK" entity handled the marketing side. Again, we simply lack any evidence to settle this point one way or the other. Some confusion has been thrown into this already-complex picture by the documented existence of yet another entity identified (in English) as "Fuji Trading". Labels bearing this name have been encountered with several NIB engines destined for the US market at around this time. However, the fact that the name never appeared on any official Fuji packaging or leaflets implies that this may well be a red herring - it may have been no more than a rendering of the name "Fuji Bussan" into an Anglicized form which would be comfortably familiar to North American customers. Alternatively, it may have had no corporate connection with Fuji Bussan, being merely a warehousing and shipping company coincidentally bearing the Fuji name (very common in Japan). A major company of this nature still operates today under the same name. One very frustrating feature of the leaflets issued with the engines during this period is the fact that they included no contact information whatsoever for either the manufacturers or distributors of the engines. It is thus impossible to keep track of any relocation initiatives which may have taken place during these years. This must have been as frustrating for the customers as it is for us today - where were they supposed to go for service or spare parts? Changes in the Late 1950's By 1957 the Fuji range had begun to gain a foothold in the world model engine market, largely as a result of the manufacturer's firm adherence to a very logical policy of staying out of the high-performance race and focusing instead on producing dependable low-cost engines for sport and recreational flying. Indications are that the expanded sales potential of the range was beginning to tax the capacity of the original factory (assuming that it was then still in use).

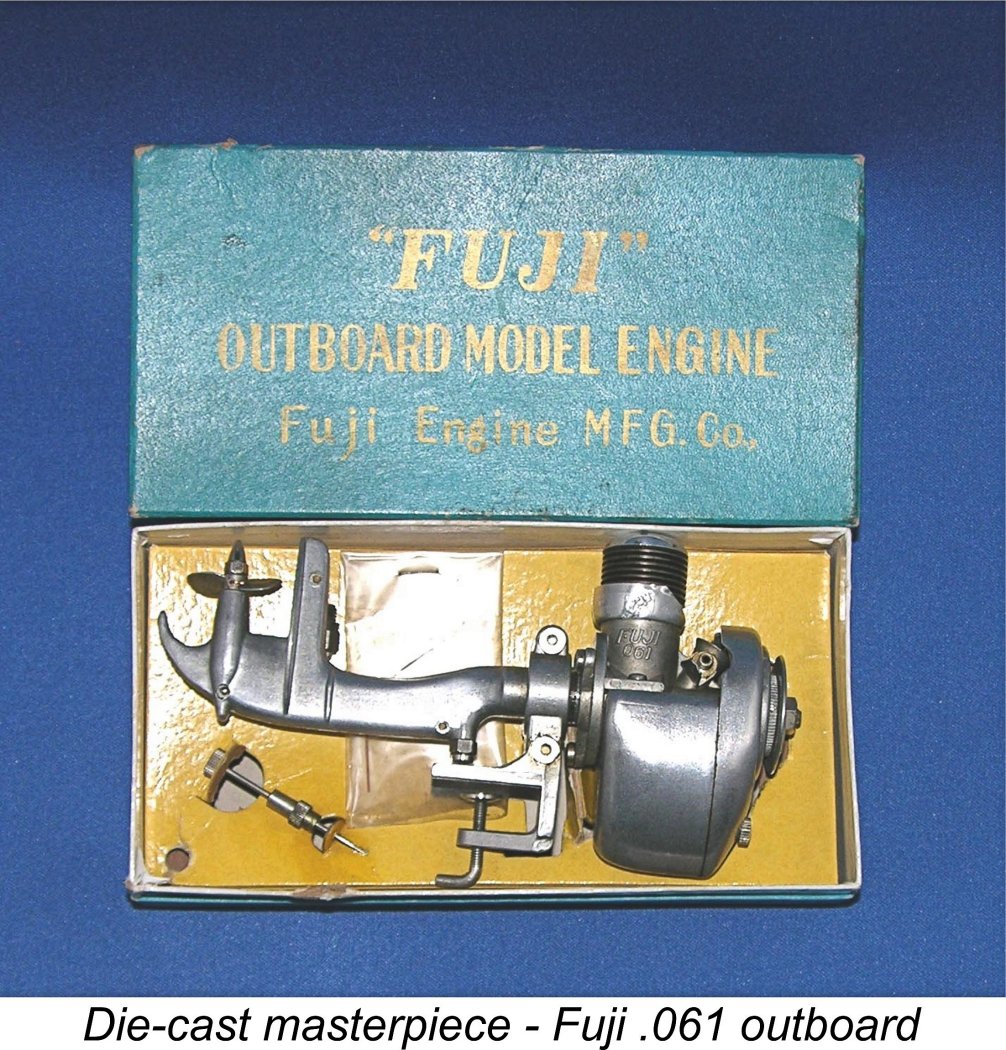

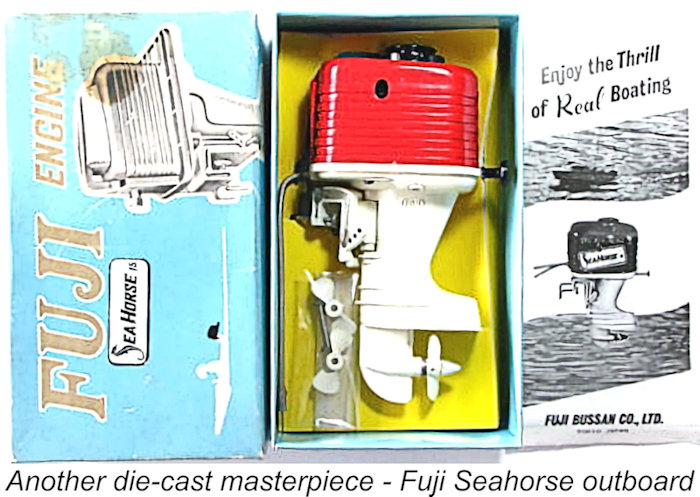

Quite apart from this, it is also from around 1957 onwards that we begin to see a marked diversification of the product lines sold under the Fuji banner. In 1957 the company began to market outboard motors in both .049 and .061. cuin displacements, following these later with a series of .15 cuin. "Seahorse" models. The pressure die-castings used in the manufacture of these units were little short of works of art, displaying an almost virtuosic mastery of die-making and casting of a standard not previously seen in connection with the Fuji range. Overall, it's apparent from the above factors that demand for the range (or the ambitions of the Fuji Bussan Co.) as well as I must now stress that I’m forced once more into the realm of speculation to a significant extent when attempting to sort out this very dynamic period in the corporate history of the Fuji marque. I’ll proceed on the basis that whatever scenarios I may propose must at least be consistent with such observed facts as are available to me. As noted earlier, serial numbers from the various models manufactured from 1958 onwards are up to an order of magnitude higher than those seen on models dating from before that year. It's very difficult to explain this other than by postulating a major expansion of the company's production capacity at around that time. Moreover, the diversity and complexity of the products concurrently entered a major expansion phase, implying a greatly stepped-up development program along with a substantial broadening of the manufacturer's technical capabilities. Leaflets and packaging supplied with the engines into the early and mid-1960's continued to bear the names of both Fuji Bussan Co. Ltd and Fuji Bussan KK. This may be taken to imply that the respective roles of these corporate entities (whatever those roles were) remained unchanged at this time. However, a new name now appeared in the Fuji family - that of the "Fuji Engine Manufacturing Company". This name was attached to the outboard motors which began to appear in 1957, as depicted in the earlier illustration above at the right. There is certainly an implication here that at least this aspect of Fuji's production activities had been entrusted to a different manufacturer as of that date. Indeed, the possibility cannot be discounted that all Fuji manufacturing had then been entrusted to this new company, with Fuji Bussan left free to focus upon the marketing role. However, if this were the case then it's hard to see why the Fuji Engine Manufacturing Company would have been identified with the outboards but not with the aero engines. For this reason, a division of manufacturing responsibilities at this stage seems perhaps somewhat more likely. Overall, it appears certain that by the late 1950's Fuji had made arrangements to greatly expand both the volume and scope of their manufacturing activities. It's unclear whether this was accomplished through the expansion of their original Tokyo manufacturing operation, through the abandonment of those facilities in favour of expanded facilities elsewhere or through an increased reliance upon sub-contracting for certain aspects of their overall production. However, this uncertainty does not in any way diminish my confidence in making the broader assertion. Enter Tannan Industrial

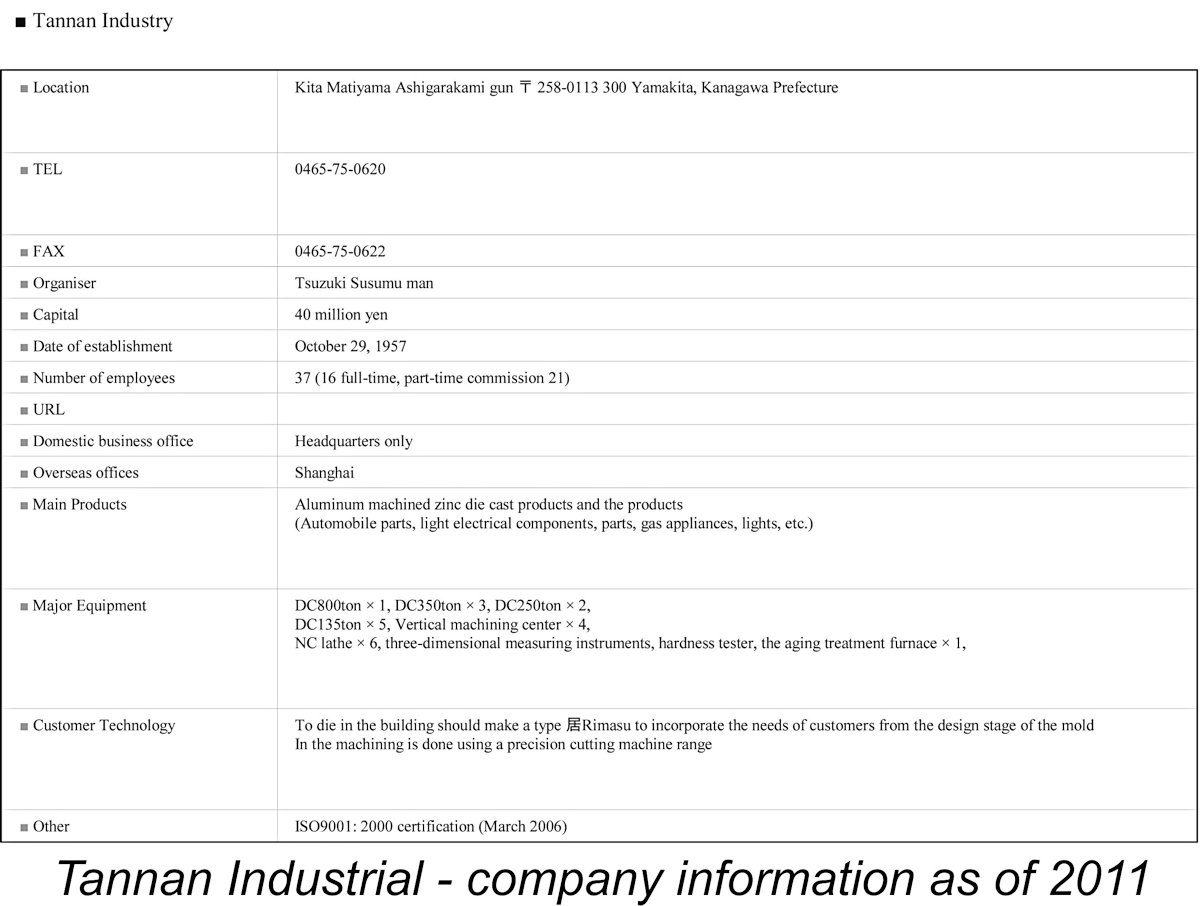

Nestling in the shadow of Mount Fuji at Yamakita, Tannan Industrial was established in October 1957. Its stated expertise was aluminium alloy die casting and machining, a perfect combination for making model aero engines. It remains an open question whether Tannan Industrial was established primarily to play a role in the manufacture of Fuji engines or whether it undertook their manufacture after becoming established through other work. However, the timing of the company's establishment certainly coincides with the well-attested major increase in production rates and diversity of the Fuji range already discussed. This of course may or may not be coincidental. If Tannan did indeed become involved at this stage (and I currently have no direct evidence for this), then their involvement may have been limited to the production of dies and die-casting, since this was their stated specialty at the outset. In addition, they may have taken on the relatively complex task of manufacturing the outboard motors, using the Fuji Engine Manufacturing Company name in that connection to keep that activity separate from their other work. The machining and assembly work relating to the aero engines may have continued to be carried out by Fuji Bussan, albeit at expanded premises. In such a case, it's also possible that Fuji Bussan supplied finished engines to the Fuji Engine Manufacturing Company for use in constructing the outboards. Whatever the facts regarding their manufacturing role, there is a very real possibility that the further technical development of the Fuji range was subcontracted to Tannan Industrial at this time. There's no question that it was from 1958 onwards that we begin to see a significant acceleration in the rate of development of the Fuji marque into the completely up-to-date range that it was to become by the late 1960's. The insertion of a new development team is strongly implied here. The combination of technical capabilities claimed by Tannan Industrial makes it clear that from the outset they were fully capable of undertaking all aspects of the manufacture of the Fuji engines. Moreover, it’s an established fact that by the late 1960's they had actually done so. My basis for making this statement is the fact that the Japanese-language leaflet with a domestic-market Fuji 15-IV in my possession specifically identifies Fuji Bussan Co. Ltd as the "Sole Seller" and Tannan Industrial as the "Sole Manufacturer". This seems quite conclusive regarding the respective roles of the two companies and does not preclude the possibility that this division of responsibilities may have been established considerably earlier. The Fuji 15-IV was introduced in around 1970, confirming that Tannan Industrial had assumed sole manufacturing responsibility prior to that date, with the Fuji Bussan Co. Ltd. continuing to handle the marketing chores. This division of responsibilities was still in effect at the end of the "classic" era with which we are concerned here. None of this precludes the possibility that Tannan Industrial may actually have taken over Fuji's manufacturing role from the outset as early as late 1957 – I’ve seen no evidence that contradicts this. The continued appearance of Fuji Bussan on the leaflets and packaging would then have been related solely to their ongoing marketing role. Tannan's stated mix of expertise (die-casting and machining) is completely consistent with Peter Chinn's comment (made in the late 1960's when Tannan is known to have taken over) that Fuji was almost unique among contemporary model engine manufacturers in making their engines entirely in-house, including the castings. Regardless of when Tannan actually became the sole Fuji manufacturer, the production figures from the mid 1960's to the close of the "classic" era, particularly with respect to the very popular .099 cuin. models, make it clear that Fuji engine manufacture must have absorbed a major part of Tannan's production capacity, if not all of it. At present I don’t know exactly when the manufacture of these engines by Tannan Industrial ceased, but whenever it came about the loss of that business must have represented a significant blow for the company. The Fuji name and associated business assets were subsequently acquired by the Model Engine Company of America (MECOA), which continued to offer (as of 2024) a line of modern engines under the Fuji trade-name, along with a number of other lines which they had acquired. Happily, Tannan seems to have successfully overcome any temporary difficulties which the loss of the model engine manufacturing may have created. As of 2011 the company remained very much in business, albeit on a relatively modest scale, apparently functioning as a jobbing engineering firm and making components for the automobile industry amongst others. Interestingly enough, the name, address and even the telephone number of the company as printed on the previously-mentioned 15-IV leaflet are identical in all respects to the 2011 information which remained available on Google Japan for Tannan Industrial and was reproduced earlier. Seemingly, things move slowly in Yamakita! Having taken any interested readers through the rather convoluted corporate history of the Fuji venture as well as present circumstances allow, it's now time at long last to direct attention towards the various model engine series produced under the Fuji banner. Articles may be found dealing with the Fuji .049/060 models, the Fuji .099 series, the Fuji .15 sequence and the Fuji 29/35 offerings. Enjoy!! _________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN in installments beginning in October 2011 This revised edition published here February 2025 |

| |

I’ve been around long enough to recall a time when the mention of the "consumer-grade" engines made in Japan and marketed under the Fuji trade-name during the "classic" era prior to 1970 or thereabouts generally produced little more than wisecracks or raised eyebrows from other "vintage" modelling types. In fact, a good few of the younger fliers didn't even know what you were talking about! Fifty years ago, interest in these early Fujis was largely confined to Japan itself - elsewhere, you could scarcely give these old Japanese classics away!

I’ve been around long enough to recall a time when the mention of the "consumer-grade" engines made in Japan and marketed under the Fuji trade-name during the "classic" era prior to 1970 or thereabouts generally produced little more than wisecracks or raised eyebrows from other "vintage" modelling types. In fact, a good few of the younger fliers didn't even know what you were talking about! Fifty years ago, interest in these early Fujis was largely confined to Japan itself - elsewhere, you could scarcely give these old Japanese classics away!

I have so far been able to find only two published references regarding the start-up date of the Fuji range. One is to be found in Mike Clanford's useful but often unreliable

I have so far been able to find only two published references regarding the start-up date of the Fuji range. One is to be found in Mike Clanford's useful but often unreliable

The brand-name Fuji is not derived from any direct association with the famous Japanese mountain of that name, which is some distance from Tokyo, where the Fuji range had its origin. There is however a connection nonetheless. Mount Fuji has great cultural significance for the Japanese people and is held in deep respect as the "peerless mountain", being generally referred to by the honorific "Fuji-san". Accordingly, the name "Fuji" applied to a product or a business denotes "quality" or "peerless" to the people of Japan.

The brand-name Fuji is not derived from any direct association with the famous Japanese mountain of that name, which is some distance from Tokyo, where the Fuji range had its origin. There is however a connection nonetheless. Mount Fuji has great cultural significance for the Japanese people and is held in deep respect as the "peerless mountain", being generally referred to by the honorific "Fuji-san". Accordingly, the name "Fuji" applied to a product or a business denotes "quality" or "peerless" to the people of Japan.  original premises were located in the Kyobashi district of Tokyo. Today this is part of the fashionable Ginza shopping district - seemingly a most improbable location for a precision engineering company, but things may well have been very different back in 1949 during the period when Tokyo was still recovering from the massive damage sustained during World War II. It is certainly true that the company's advertisements from the late 1950's were still citing the Kyobashi location, although this was very likely merely an office location by that time, with the actual manufacturing taking place elsewhere.

original premises were located in the Kyobashi district of Tokyo. Today this is part of the fashionable Ginza shopping district - seemingly a most improbable location for a precision engineering company, but things may well have been very different back in 1949 during the period when Tokyo was still recovering from the massive damage sustained during World War II. It is certainly true that the company's advertisements from the late 1950's were still citing the Kyobashi location, although this was very likely merely an office location by that time, with the actual manufacturing taking place elsewhere.

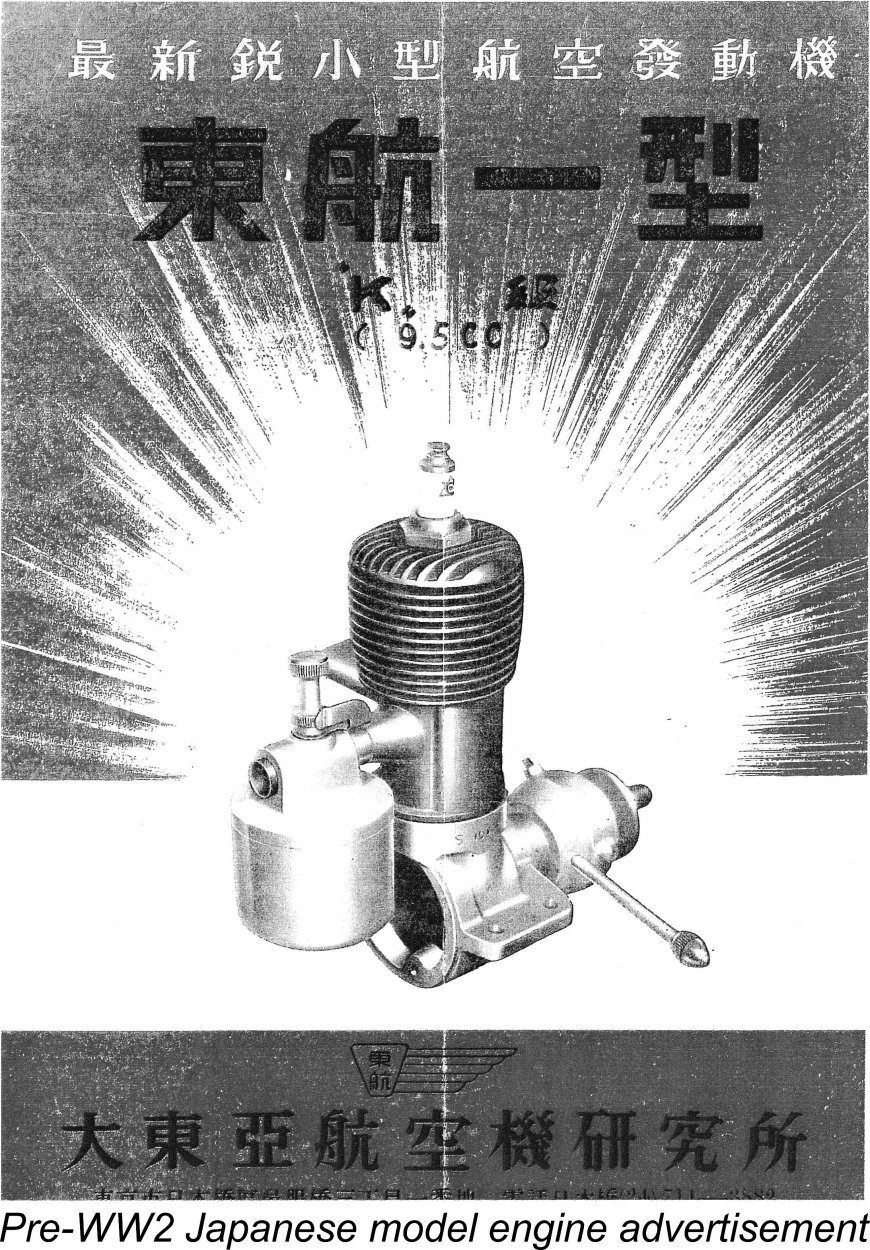

In order to fully appreciate the activities of any newly-established model engine manufacturer, it's essential to understand the context in which those activities took place. It's a widely under-appreciated fact that there was a thriving power modelling scene in Japan prior to WW2 - indeed, the commercial manufacture of model engines was well established there prior to the Japanese entry into that conflict in December 1941. WW2 put the brakes on such activities, but commercial-scale model engine manufacturing in Japan resumed very quickly following the end of the war.

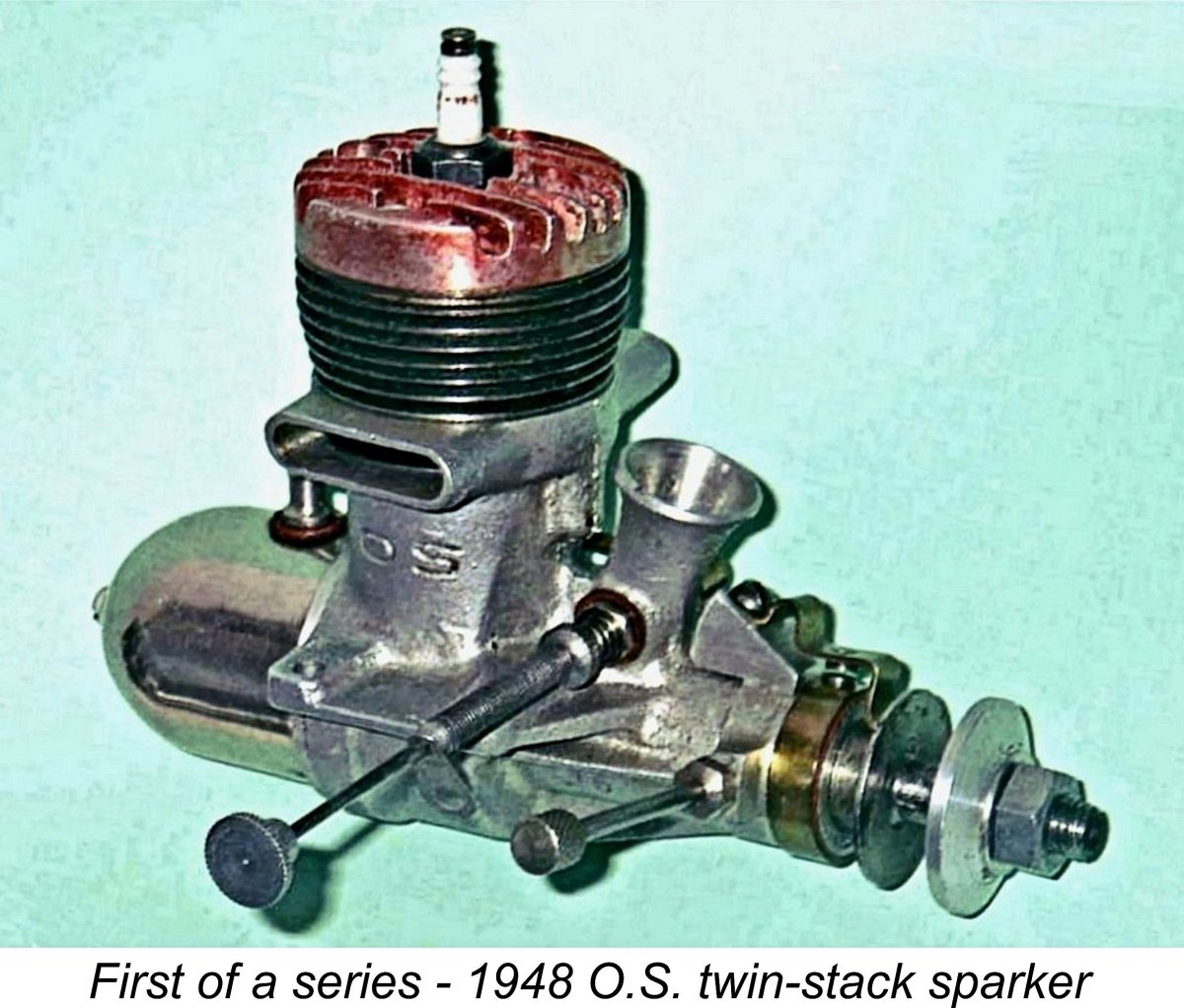

In order to fully appreciate the activities of any newly-established model engine manufacturer, it's essential to understand the context in which those activities took place. It's a widely under-appreciated fact that there was a thriving power modelling scene in Japan prior to WW2 - indeed, the commercial manufacture of model engines was well established there prior to the Japanese entry into that conflict in December 1941. WW2 put the brakes on such activities, but commercial-scale model engine manufacturing in Japan resumed very quickly following the end of the war. The Osaka-based O.S. line, which had been well-established prior to WW2, was early in the post-war field. By 1949 designer Shigeo Ogawa had a number of well-made engines on the market, including both .29 cuin. and .64 cuin. glow models.

The Osaka-based O.S. line, which had been well-established prior to WW2, was early in the post-war field. By 1949 designer Shigeo Ogawa had a number of well-made engines on the market, including both .29 cuin. and .64 cuin. glow models.

Tokyo Hobbycrafts, makers of the

Tokyo Hobbycrafts, makers of the  The commercial marketing of the Fuji range appears to have commenced in early 1949 with their first .29 cuin. model, which was quickly followed by a companion .099 design. In separate articles to be found elsewhere on this website, I’ve traced the development of the Fuji engines in both of those displacement categories.

The commercial marketing of the Fuji range appears to have commenced in early 1949 with their first .29 cuin. model, which was quickly followed by a companion .099 design. In separate articles to be found elsewhere on this website, I’ve traced the development of the Fuji engines in both of those displacement categories. The Tachikawa Aircraft Company Ltd. had its origins in 1924, when Ishikawajima Shipyards (the future IHI Corporation) established a subsidiary company, the Ishikawajima Aircraft Manufacturing Co. This company's first design was a primary training aircraft called (in Japanese) the Red Dragonfly.

The Tachikawa Aircraft Company Ltd. had its origins in 1924, when Ishikawajima Shipyards (the future IHI Corporation) established a subsidiary company, the Ishikawajima Aircraft Manufacturing Co. This company's first design was a primary training aircraft called (in Japanese) the Red Dragonfly. During the war, Tachikawa manufactured an extensive range of military aircraft, including the famed

During the war, Tachikawa manufactured an extensive range of military aircraft, including the famed  Motivated by prevailing gasoline shortages in Japan, the new subsidiary immediately began to develop a battery-powered electric car to be marketed under the

Motivated by prevailing gasoline shortages in Japan, the new subsidiary immediately began to develop a battery-powered electric car to be marketed under the  manufacture. Their first such product was the highly-successful 1952 "Prince Sedan" automobile, so-named in honor of Prince Akihito's formal investiture as Crown Prince in that year.

manufacture. Their first such product was the highly-successful 1952 "Prince Sedan" automobile, so-named in honor of Prince Akihito's formal investiture as Crown Prince in that year. If someone within the company had wished to re-enter the aviation field through the manufacture of model aero engines, it would have made complete sense to do so through the establishment of a subsidiary venture. Such a move in this instance might have seen Fuji Tokushu Kiki established for the purpose of manufacturing model engines while the parent Fuji Precision Industries maintained its focus on the far larger-scale activities which were to take them so far.

If someone within the company had wished to re-enter the aviation field through the manufacture of model aero engines, it would have made complete sense to do so through the establishment of a subsidiary venture. Such a move in this instance might have seen Fuji Tokushu Kiki established for the purpose of manufacturing model engines while the parent Fuji Precision Industries maintained its focus on the far larger-scale activities which were to take them so far. Camera Co. employee. The

Camera Co. employee. The  Over the first few years of the Fuji model engine manufacturing venture, the range expanded considerably in terms of scope. Development of the .099 and 29 models with which the business had got its start continued, with additional models in the .049, 19 and 35 displacement categories also being added successively. Levels of production remained modest, but the Fuji range was an industry leader in terms of diversity.

Over the first few years of the Fuji model engine manufacturing venture, the range expanded considerably in terms of scope. Development of the .099 and 29 models with which the business had got its start continued, with additional models in the .049, 19 and 35 displacement categories also being added successively. Levels of production remained modest, but the Fuji range was an industry leader in terms of diversity.

Serial numbers of Fuji models dating from the latter half of the 1950's indicate conclusively that production figures took a quantum upward leap starting in around 1957. Not only that, but from 1957 onwards we can document a rapid acceleration in the process of transforming the Fuji marque from a basic and increasingly (if charmingly) archaic range into the somewhat stereotypical modern and completely up-to-date range that it was to become during the following decade.

Serial numbers of Fuji models dating from the latter half of the 1950's indicate conclusively that production figures took a quantum upward leap starting in around 1957. Not only that, but from 1957 onwards we can document a rapid acceleration in the process of transforming the Fuji marque from a basic and increasingly (if charmingly) archaic range into the somewhat stereotypical modern and completely up-to-date range that it was to become during the following decade. the broadening scope of the products themselves had outstripped the ability of the original Tokyo factory to keep up. Not only that, but the technical demands placed upon the manufacturing arm, particularly in the area of die-casting, had increased significantly. If it had not already taken place, a change in manufacturing arrangements was clearly in order. Such evidence as I have been able to gather is entirely consistent with this notion.

the broadening scope of the products themselves had outstripped the ability of the original Tokyo factory to keep up. Not only that, but the technical demands placed upon the manufacturing arm, particularly in the area of die-casting, had increased significantly. If it had not already taken place, a change in manufacturing arrangements was clearly in order. Such evidence as I have been able to gather is entirely consistent with this notion. Although at present I don't know exactly when this took place, there's no doubt whatsoever that at some point after 1957 the further development and manufacture of the Fuji range was entrusted to a precision engineering company known as Tannan Industrial. This company remains in existence today, albeit on a relatively modest scale, and it has been possible to learn something of its corporate history.

Although at present I don't know exactly when this took place, there's no doubt whatsoever that at some point after 1957 the further development and manufacture of the Fuji range was entrusted to a precision engineering company known as Tannan Industrial. This company remains in existence today, albeit on a relatively modest scale, and it has been possible to learn something of its corporate history.