|

|

Forgotten British Pioneer - the Majesco range

This article was originally published in late 2014 on the late Ron Chernich's now-frozen but still accessible "Model Engine News" (MEN) web-site. It was in fact the last article of mine that Ron was able to add to his site before his final illness tragically claimed him. Unfortunately, the images associated with the MEN article do not come up as they should, and Ron is no longer around to fix this, nor did he leave instructions, passwords, etc., to allow his successors to do so. Accordingly, I saw no option other than to re-publish the article complete with images on my new web-site. I have taken full advantage of the opportunity to incorporate some significant new insights and test results which have become available since the original publication.

Majesco Miniature Motors was one of the first companies in England to commence the commercial manufacture of model engines in the post-war period. Sadly, it was also one of Britain's shortest-lived such ventures, never managing to achieve mainstream status and hence being virtually forgotten today by all but a few dedicated enthusiasts. Due to its very brief presence in the marketplace, it was also relatively poorly documented in the contemporary modelling media. There is information scattered here and there, but it takes some ferreting out! This being the case, I’ll just have to do the best that I can with the resources at my disposal. When writing this article, I An earlier article on the Majesco Mite appears on the MEN site. However, that earlier article does not not include a full evaluation of the engine. I’ll address that omission in the present write-up. Before commencing, I would as always like to recognize the invaluable assistance rendered to me by others. The preservation of model engine history is very much a shared responsibility, and I’m fortunate in having a number of colleagues who recognize this undeniable fact and are unstinting in their willingness to assist where possible - there's no way that I could do this alone. In the present instance, I must record a debt of gratitude to Kevin Richards, Jon Fletcher, Eric Offen, Gordon Beeby and the late Ken Croft, all of whom assisted me very materially during the course of this exercise. Jon's successful efforts to rectify a few structural issues with the Mite were particularly appreciated, as were Gordon's successful efforts to locate a number of obscure information sources which I had missed first time around. That pleasant duty fulfilled, let’s get right on with the story of the Majesco range! Background

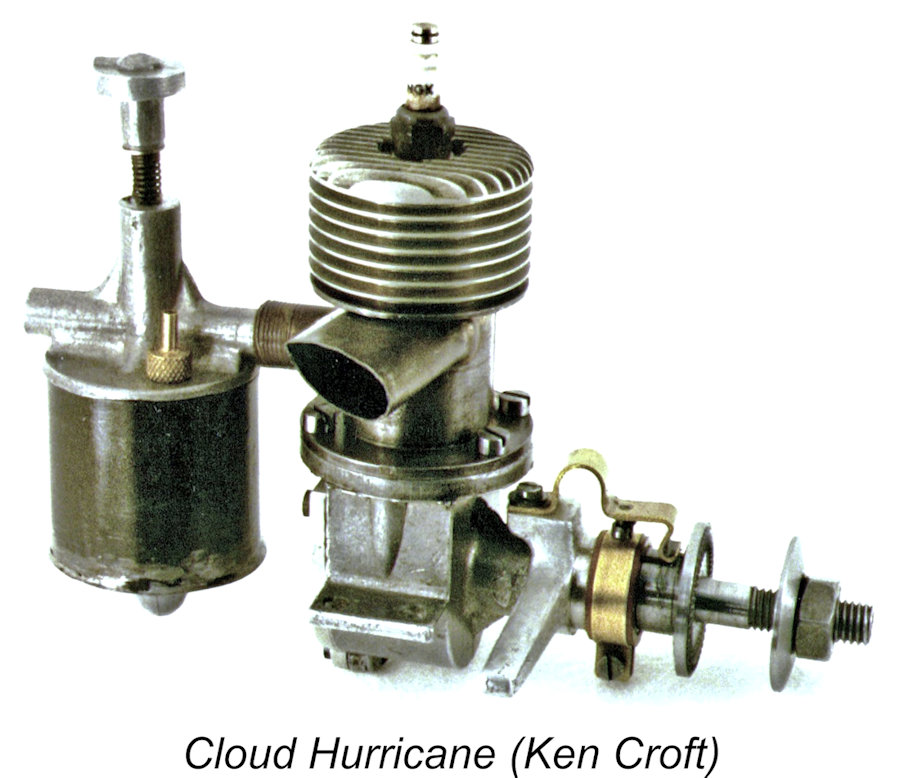

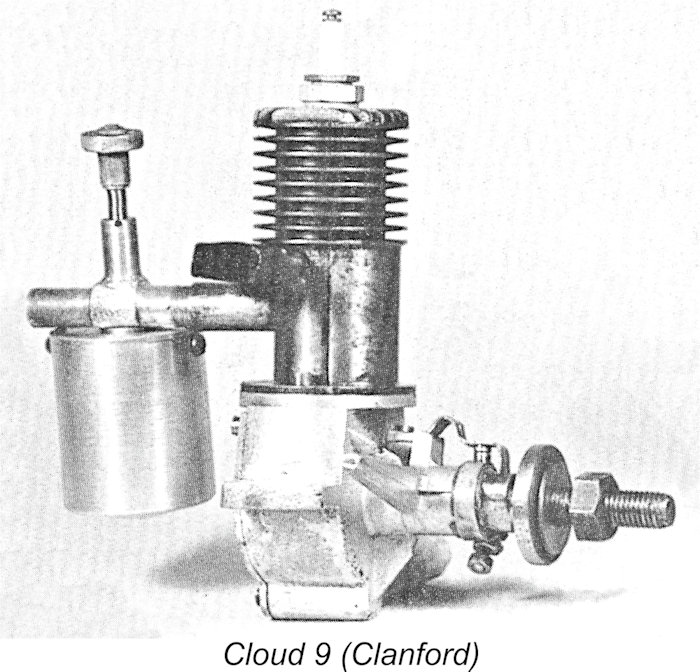

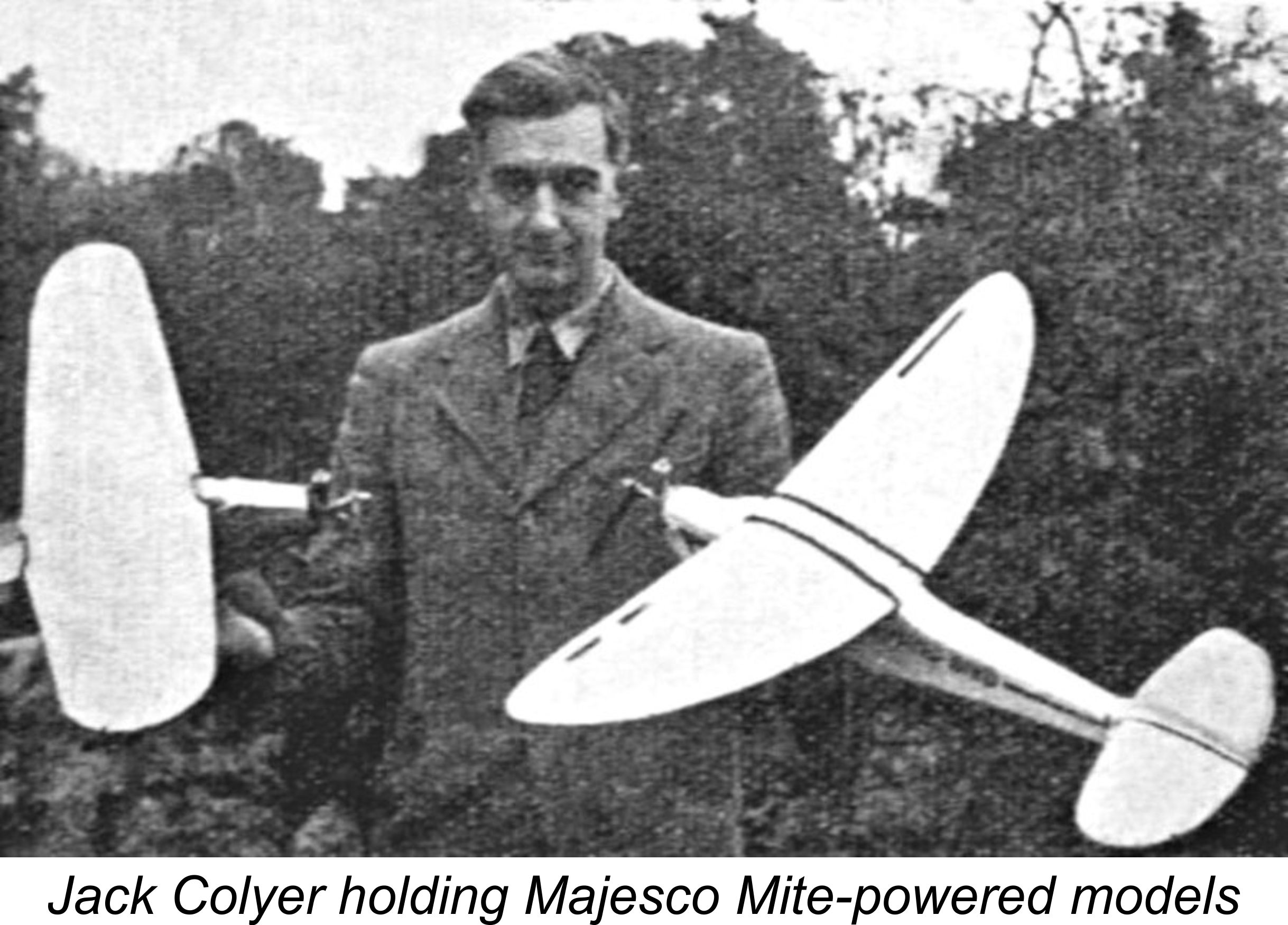

According to a brief obituary which appeared in the March 1990 issue of "Aeromodeller", Colyer was a man of many parts. Apart from being a talented artist and musician, he was a skilled model engineer and a keen aeromodeller, particularly during the pre-WW2 years when he specialized in the building and flying of the large free flight power models of the pioneering era. He became a close friend of Col. (then Captain) C. E. Bowden - in fact, his first power model was a rendition of Bowden's 8 foot wingspan "Blue Dragon" design, using which he narrowly missed winning the inaugural Bowden Trophy in 1937. This model was powered by one of the first examples of the Brown Junior engine to reach England. One of Colyer's more or less forgotten accomplishments was the fact that he got his start as a commercial model engine manufacturer in 1938 by designing and manufacturing the now very obscure and mega-rare pre-war British engines which were marketed under the Cloud trade-name by Cloud (Model) Aircraft of Dorking, Surrey.

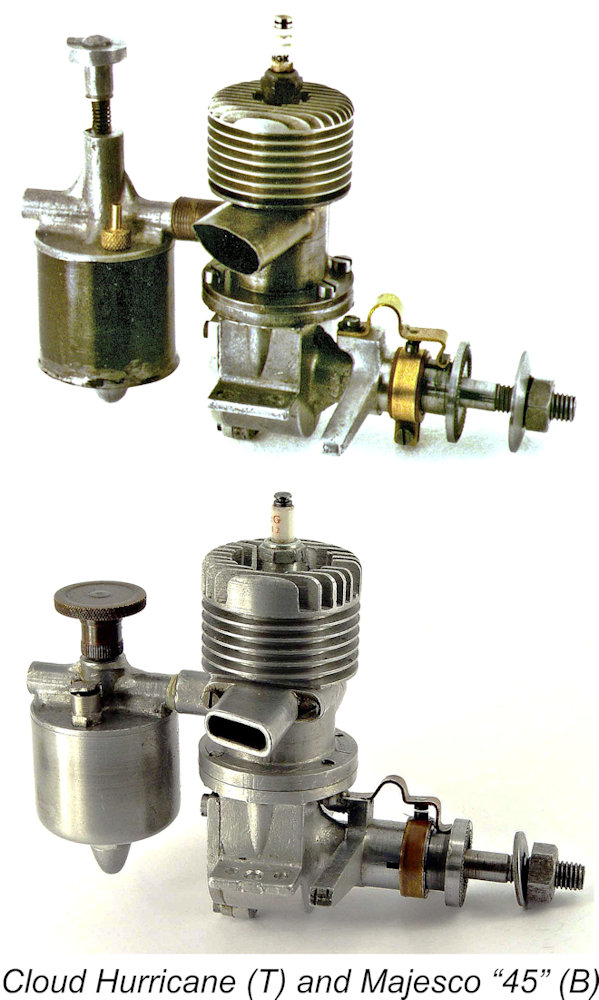

Three models were produced - the 9 cc Cloud 9 of 1938, the 3 cc Cloud 3 of 1939 and the nominally 3.8 cc Cloud Hurricane of 1940 (actually a 4.52 cc model). It's not known if these were consecutive or concurrent productions. Either way, they were manufactured in relatively small numbers, hence being extremely rare today. During this period, Colyer appears to have been living and probably working in Littlehampton, Sussex, a seaside town of modest size lying between Brighton and Chichester on England’s south coast. The report on the 1939 Sir John Shelley Cup competition which appeared in the September 1939 issue of "Aeromodeller" lists him as a competitor and confirms his place of residence as Littlehampton (Colyer finished eighth in this contest). It appears that Colyer's workshop in For obvious reasons, the onset of WW2 put a premature end to Colyer's model engine manufacturing activities, at least for the duration. It's not known how Colyer was occupied during the WW2 years. At age 30 at the outbreak of war, he was eligible for being drafted into military service, but it seems more likely that his precision engineering talents were utilized on the home front in war materiel production. Regardless, the end of the war found Colyer desirous of resuming his model engine manufacturing activities. Since the Cloud model engine venture had died upon the onset of the conflict and was not resumed thereafter, he necessarily did so using his own trade-name of Majesco. Following the original publication of this article, I was fortunate enough to hear from reader Richard Thick, who kindly contacted me after perusing the original text. Richard is actually Jack Colyer's son-in-law, having married his daughter Rosanne and hence having a good deal of knowledge about the Majesco venture. Richard tells us that the letters "MA" in the Majesco name were derived from the initials of Colyer's wife Miriam Annette, who was of course Richard's mother-in-law. The next three letters "JES" were obviously derived from Jack Colyer's own initials, while the "CO" represented Colyer. One of the challenges involved in tracing the story of our subject company is sorting out the unusual number of different addresses with which the venture was associated. According to the instruction sheet which accompanied the kit version of the company’s initial offering, the Majesco “45” (see below), the company’s original manufacturing facility was located on Church Street in Littlehampton. Although it can't be proved, it seems highly likely that this was the same workshop in which the Cloud engines had been produced before the war.

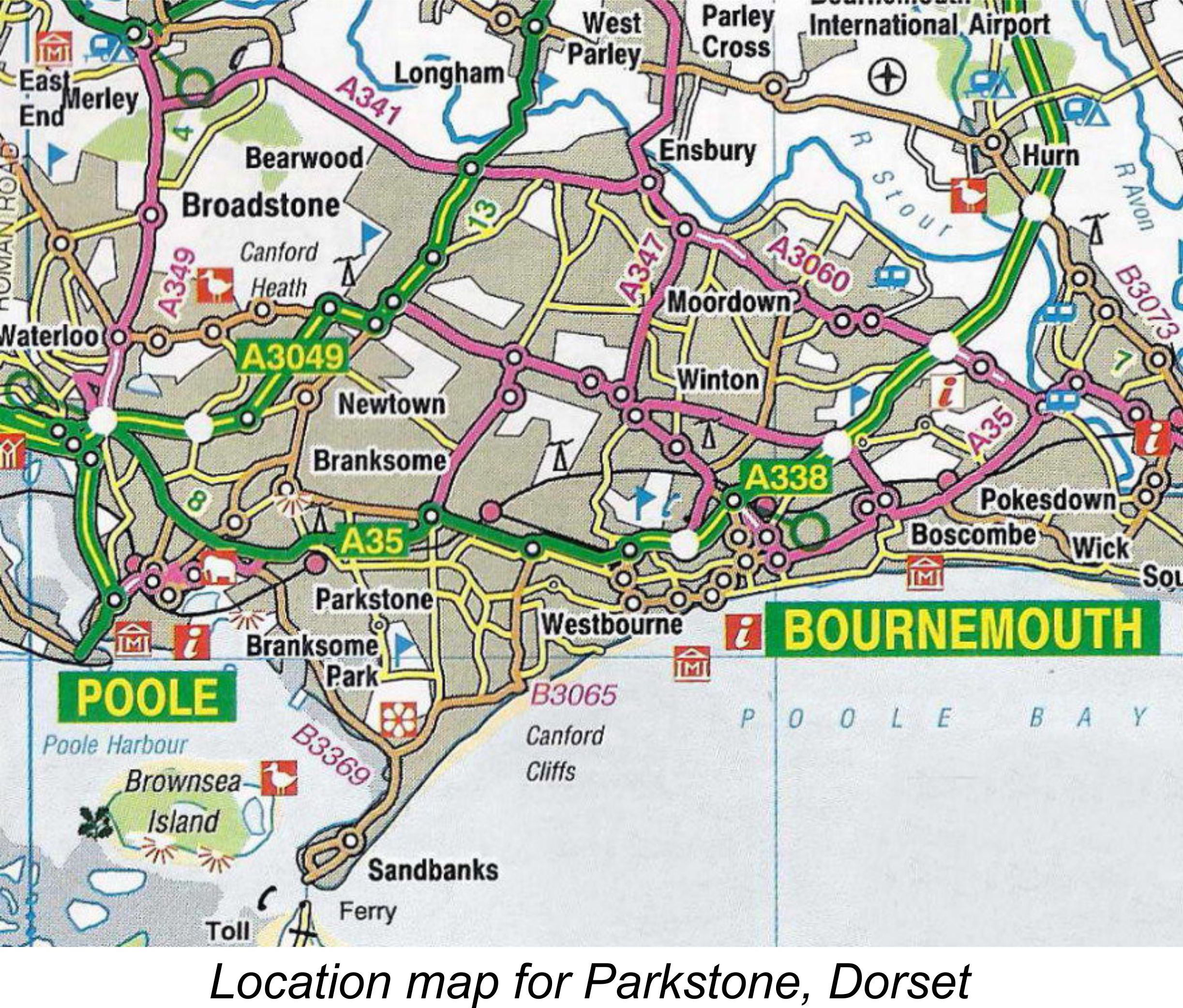

A certain amount of light was thrown on this situation by Richard Thick. It turns out that the Littlehampton business address on St. Flora's Road was in fact the residence of Jack Colyer's parents-in-law! The actual manufacturing evidently took place at the Church Street location. Majesco Miniature Motors was a regular advertiser in "Model Aircraft" magazine during its initial year or more of operation. The ads down to November 1946 confirm that the company continued to conduct business from the Littlehampton address. Moreover, a short paragraph by Ron Warring in the Ian Allan publication "Power Models" referred to a visit to Jack Colyer at Littlehampton around Christmas 1946. However, in early 1947 the company relocated some distance further west along the south coast to a new address on Vale Road in Parkstone, Dorset. This is the address which has been associated most commonly with Majesco Miniature Motors. Confirmation of this move is found on a box label which accompanied a kit version of the Majesco "45". The box label carries the original general office address on St. Flora’s Road in Littlehampton, but a stick-on supplementary label refers to the company’s “new address” as being Vale Road in Parkstone. Thanks to Eric Offen for providing these vital pieces of evidence.

Whatever the circumstances, the move to Parkstone was duly accomplished, almost certainly in very early 1947. As of the present day (2015), Parkstone is more or less a suburb of Poole lying a little to the east of that town’s centre in the direction of nearby Bournemouth. At the time of which we are speaking, however, it’s possible that it was a separate community.

Model engines were also produced in the area by Bijou Mechanical Productions (Bournemouth) Ltd., makers of the B.M.P. diesels which were designed by Henri Baigent. These were sold through the agency of J. W. Kenworthy of 295 Charminster Road, Bournemouth, who did much to promote them. An in-depth article about the fascinating history of the B.M.P. venture may be found elsewhere on this website. Although actually manufactured in Leicester by Rogers & Geary (makers of the prewar Comet 18 cc, Spitfire 2.5 cc, Hornet 3.5 cc and Wasp 6 cc spark ignition models), the well-known post-war Stentor 6 cc spark ignition engines were marketed primarily by Model Aircraft (Bournemouth) Ltd., better remembered today for their Veron kit range. The area was to retain a strong identification with model engine manufacture in subsequent years following the March 1955 relocation of the Oliver workshops from Nottingham to Ferndown, a little to the north of Poole.

Colyer clearly had a very sincere interest in model engines to go along with some excellent connections in the USA plus the means to indulge his interests, since Warring tells us that over the years he eventually assembled a collection of some fifty different engines representative of then-current American design and construction practise, thus becoming one of the very first recorded engine collectors! No doubt he drew heavily upon the information embodied in this collection when developing his own designs. In Colyer's later advertising, he claimed to have constructed the first prototype of the initial post-war Majesco offering, the “45” spark ignition motor, as early as mid-1939, long before Majesco Miniature Motors came into being and during the period when Colyer was manufacturing the Cloud model engines. This claim is consistent with the fact that the design of the Majesco "45" bears a more-than coincidental similarity to that of the Cloud Hurricane of 1940. It would appear that Colyer viewed the Cloud model as the prototype of the later Majesco "45". The fact that several of the Majesco designs were made available as kits of castings and materials for home construction confirms Colyer's ongoing support for the model engineering community of which he was a part. The range appears to have been targeted as much towards the “model craftsman” fraternity as to the average aeromodeller who merely needed an engine to power his models and was prepared to pay others to make it for him. Quite apart from the reasons given earlier for the move to Parkstone, another factor may well have been Colyer's well-documented close friendship with Bournemouth resident Col. C. E. Bowden. One may wonder why Colyer would commence the Majesco venture at distant Littlehampton in the face of a clear desire to relocate to the Bournemouth area when this became possible. The most likely explanation is that he was unable to secure suitable premises in the Bournemouth area at the time when Majesco production commenced, but seized upon a later opportunity. In the interim, he utilized his existing premises at Littlehampton.

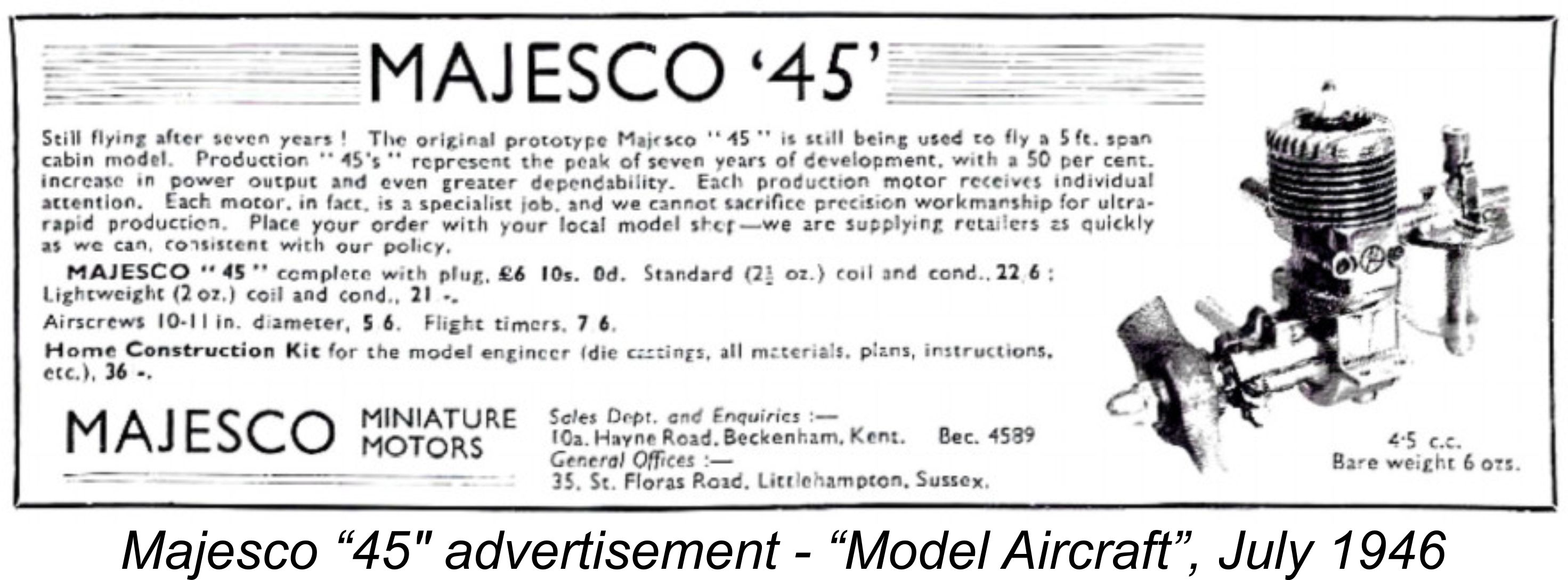

Apart from the considerable time and effort which must have gone into getting the Majesco venture off the ground, Colyer continued his involvement with aeromodelling during this period. He entered the 1945 Bowden Trophy with a very large model powered by a twin-cylinder engine of his own design and manufacture. He also won a first-place award at the 1945 Dorland Hall exhibition with a sleek-looking twin-engined model. Now let’s see what we can do to present a coherent picture of the products of the short-lived Majesco venture. The Beginning - the Majesco “45” The Majesco company started out in early 1946 with a side-port petrol engine of 4.5 cc displacement. This was known as the Majesco “45”, a name which tends to confuse American model engine enthusiasts! It refers of course to the engine’s nominal metric displacement of 4.5 cc (0.275 cuin.) rather than the more familiar .45 cuin. Similar confusion was also to arise in connection with the metrically-designated FROG and Allen-Mercury diesel ranges, among others.

The Majesco "45" was clearly a derivative of the Cloud Hurricane - the design similarities are far too marked to be coincidental. Bore and stroke were identical, while the crankcase appeared to have been produced from the same permanent mold. In addition, the porting, ignition timing and fuel supply arrangements were essentially identical. In an article which appeared in the February 7th, 1946 issue of "Model Engineer", Edgar T. Westbury confirmed that the Majesco "45" had indeed been developed based on experience gained from the small-scale production of an un-named pre-war design - presumably the Cloud Hurricane. Colyer himself evidently considered the Cloud Hurricane to be the development prototype of the Majesco "45". Once introduced, it seems that demand for the Majesco "45" quickly outstripped the manufacturer's ability to produce it! The Majesco Motors advertisement for the "45" which appeared in the September 1946 issue stated that the company was unable to accept any more orders at that time. Let's have a look at this engine to see why it apparently attracted so much attention.

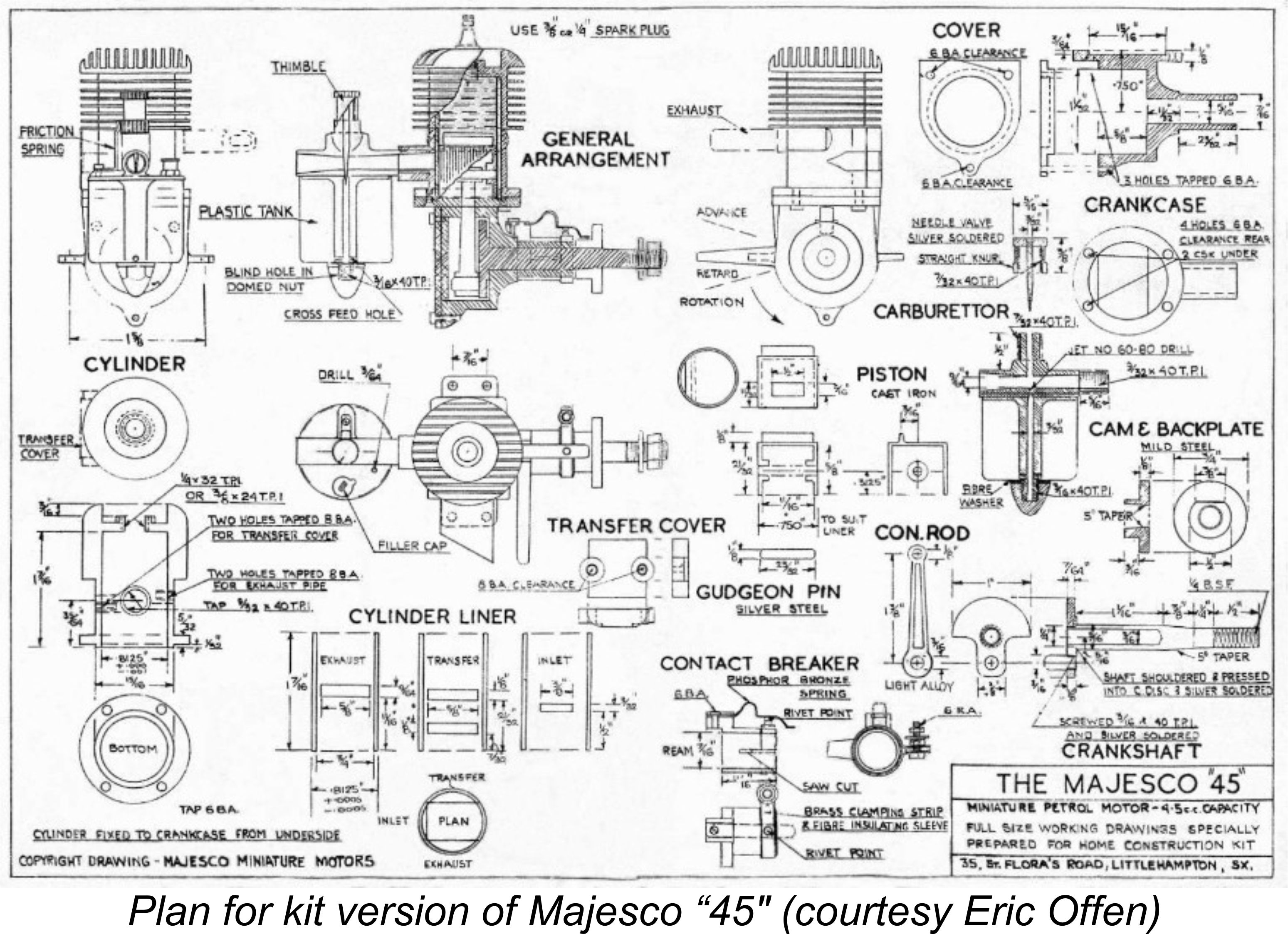

The Majesco "45" sold in ready-to-run form for a fairly healthy price of £6 10s 0d (£6.50). It was also made available at a far more economical price of £1 16s 0d (£1.80) in kit form for home construction by the model engineering fraternity. Structurally, the “45” was built around a main crankcase which incorporated the main bearing housing in unit. This component was die-cast in aluminium alloy, as were all of the other cast components. The crankcase casting terminated in a circular flange just above the crankcase The bypass passage was a composite affair, being open to the external atmosphere as cast. It was externally sealed using a separate die-cast cover plate which was secured to the main cylinder casting with two screws, a gasket being used to ensure a good seal. This arrangement was reminiscent of that seen in the earlier G.H.Q. and Dallaire Pee Wee models from America, among others. The exhaust Internally, the engine featured a cast iron baffle piston to go with the steel cylinder liner. The piston drove the crankshaft through a die-cast aluminium alloy connecting rod. The steel crankshaft was a composite affair which was built up from three components - the main journal, the crankweb and the crankpin. These components were pressed together and then silver soldered. The shaft ran in a plain main bearing formed directly in the material of the crankcase casting. The timer was an open-frame affair which was actuated by a cam formed at the rear of the steel prop driver.

Recommended airscrews as reported by Ron Warring in his book were 11x6 for free flight and 8x8 for control line. These are relatively light loads for a 1940’s engine of this displacement, presumably reflecting the engine’s short-stroke geometry. In the Somewhat oddly, Warring also reported that the selling price of the “45” was £4 4s 0d (£4.20), which is at odds with the advertisements that I've so far encountered. This actually appears to have represented a price reduction during the inventory clearance phase at the end of the company’s production activities, which evidently pretty much coincided with the writing of Warring’s book in late 1948. All Majesco engines that were manufactured by the company (as opposed to being sold in kit form) c Be that as it may, reported serial numbers for the Majesco “45” range at present from a low of 114 up to a high of 717, apparently implying that at least 750 examples may have been built by the company (setting aside the possibility that the numbering sequence may have started at 100). There may well have been quite a few more - my sample remains relatively small. Un-numbered examples also turn up fairly frequently. These are almost certainly home-constructed efforts, the quality of which may vary somewhat. The engine actually seems to have sold quite well in kit form. Although we can’t be definite regarding how many examples of this model were made, it appears to have remained in production or at least on sale for much of the company’s existence, appearing regularly in retailer advertisements throughout 1947. As of June 1947 the engine remained available to order from Gamages of Holborn in London, orders being filled in strict rotation. This suggests that at that time (well over a year following the engine's introduction), demand was still exceeding supply. The “45” was still on offer from Paramount Model Aviation of Westcliff-on-Sea in Essex as of May 1948, at an unchanged price of £6 10s 0d (£6.50). The fact that its selling price had evidently held up for two years is a further indication of its ongoing popularity.

According to those who have used them, these engines are very dependable runners which are well able to give good service. For this reason, the Majesco “45” is much favored by today’s vintage fliers in Britain. As an example, I attach a picture of the late Ken Croft’s model fitted with factory-built Majesco “45” number 114 which had been in regular service for the previous eight years as of 2013 when Ken sent me the photo. To reinforce this positive view of the engine, I recently had occasion to run a bench test of my own example of the Majesco “45”, engine number 576. Before proceeding any further, I’ll summarize the results of that test. The Majesco “45” on Test

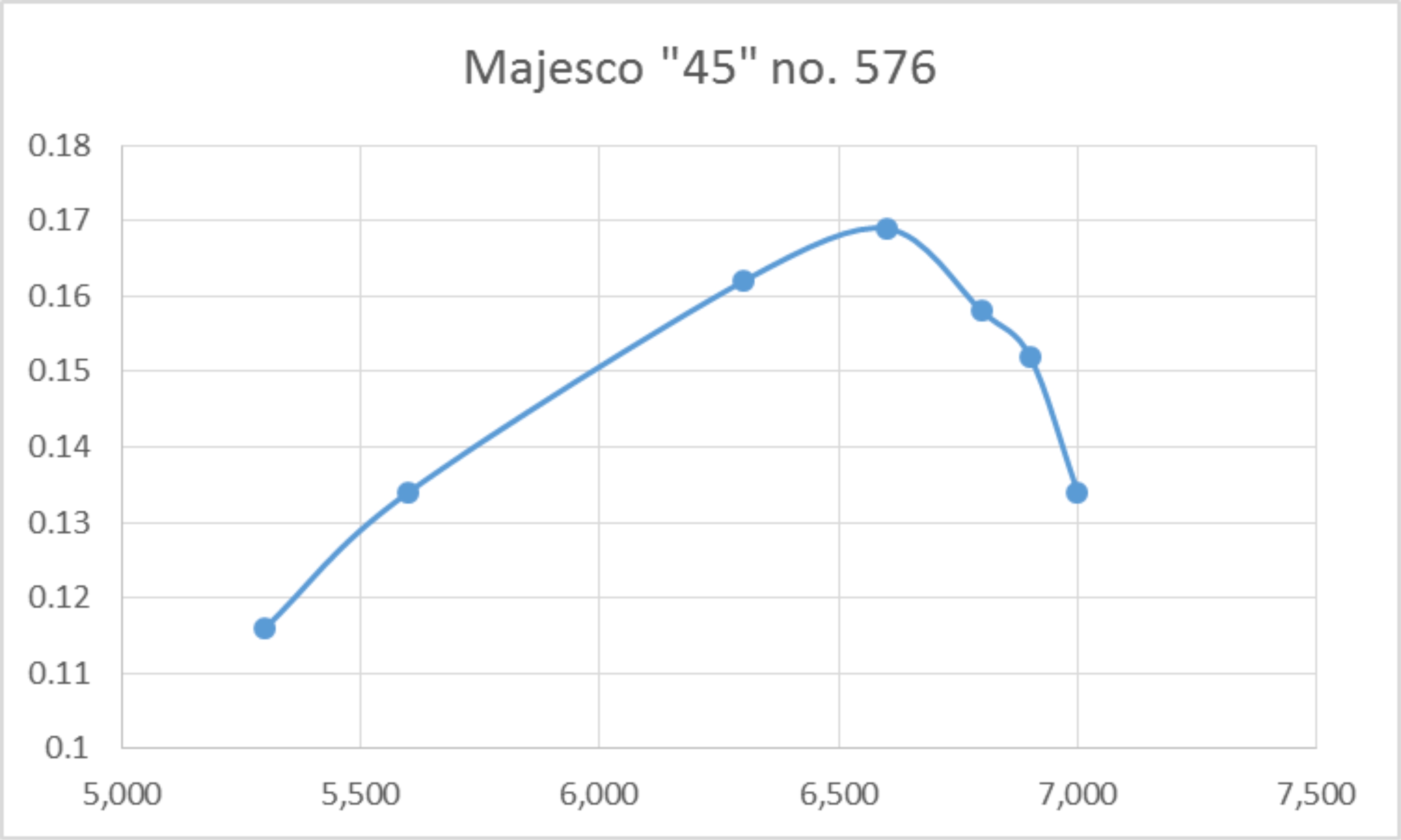

The original KLG spark plug was still with the engine as received. This too proved to be in perfect working order, hence being used for all my testing. I also used my standard “classic sparkie” fuel consisting of 3 parts of Coleman camp fuel (white gas) to one part of AeroShell 120 SAE 60 mineral oil. The essential sparks were provided by one of my very dependable Larry Davidson solid state ignition systems. For those wishing to try their own sparkies (highly recommended - it’s great fun!), I’ve described the very straightforward process of creating one of these systems in my separate article on spark ignition operation. Setting the Majesco up in my test stand, I fitted a 12x5 wood prop for the initial start. I set the needle at 1½ turns by pure guesswork, filled the tank, gave the thing a couple of choked turns, administered a small It turned out that I’d guessed the needle setting almost exactly. I quickly found that the needle setting was quite critical for best performance on a given prop. This is a not-unusual characteristic of surface jet carburettor systems like this one. Despite this, the best setting was easily established - going a few clicks either side of the sweet spot merely caused the engine to slow down rather than stop. By contrast, response to the timer arm setting was by no means ultra-critical. Running qualities were all that could be desired - dead smooth with never a missed beat and no sign of sagging. Vibration levels also appeared to be well within acceptable limits. Restarts following prop changes were also very straightforward, although the engine was a little unusual for a sparkie in preferring a small prime when cold - finger choking alone was a bit unreliable. A couple of finger chokes followed by a small prime generally had the Majesco going within a few flicks. In performance terms, the engine fell a little short of the manufacturer’s claims. The following data were recorded.

As can be seen, the engine appeared to develop a peak output of around 0.169 BHP @ 6,600 rpm. While this is a little down on the manufacturer’s claim of 0.200 BHP @ 7,500 rpm, it is not greatly so. With a bit more running time to free things up a little more, the engine would doubtless do more than it did on this occasion. Even so, it was well ahead of competing British models such as the Reeves 6 cc model and the Mechanair 5.9 cc unit tested elsewhere. The very sharp drop-off in output past the peak is entirely typical of sideport model engine designs - there would be no point in propping this example for airborne speeds in excess of 6,500 rpm. The manufacturer's recommendation of an 11x6 prop for free flight applications seems entirely appropriate. On the basis of this test, I can quite understand the high regard in which the Majesco “45” is held by the old time flying community. It’s a dependable and easy-starting unit which runs very smoothly and develops more than enough power to fly a model of quite considerable size. Most of its users back in the day would have been well satisfied! A False Start - the Majesco 10 cc prototype

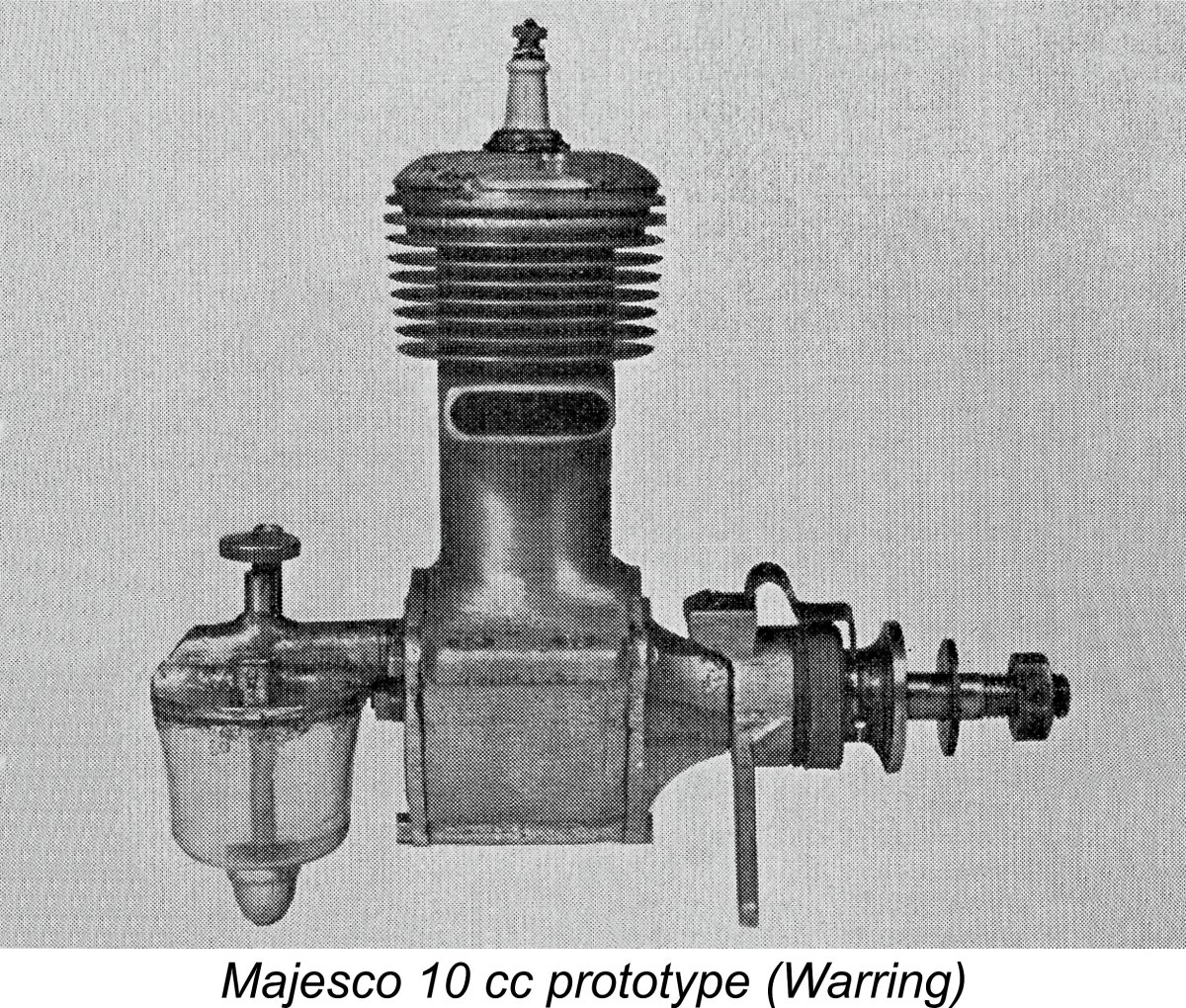

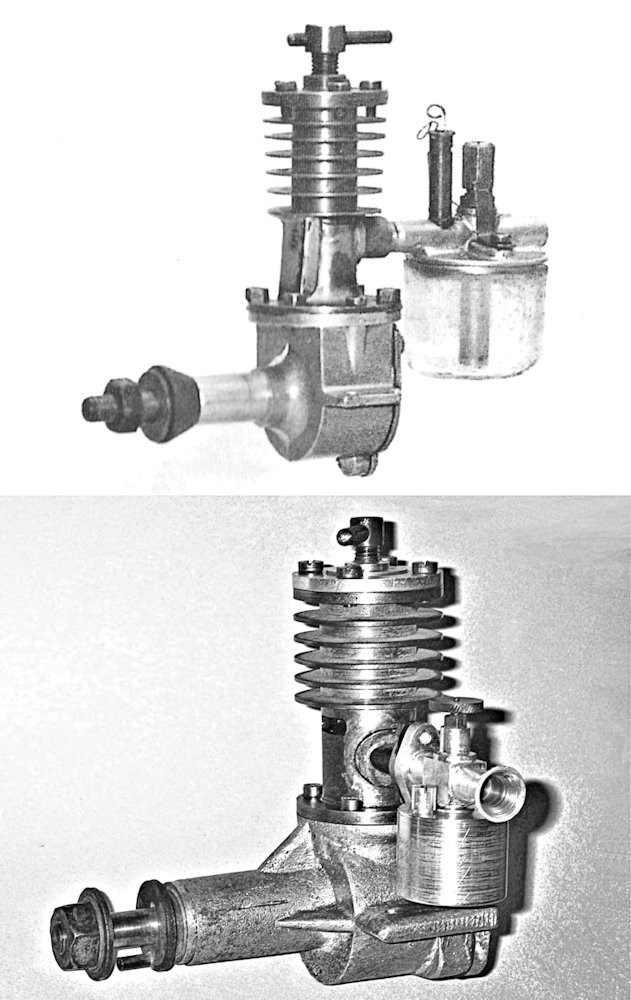

The tank and timer appear to be the same components used in the Majesco "45", seemingly confirming that the 10 cc prototype was a contemporary of the smaller model. The fact that Warring applied the Majesco name to it clearly implies that it post-dated the early 1946 establishment of Majesco Miniature Motors. It was certainly under development as of August 1946 when a prototype appeared at the Model Engineer Exhibition, as noted in the October 17th, 1946 issue of "Model Engineer". It was presumably this prototype that was illustrated by Warring. Warring evidently saw this engine run, because he commented that it performed well up to par with American non-racing designs. However, for reasons regarding which Warring was silent, the engine never entered production. It's entirely possible that this was not the only Colyer design to stall following the prototype stage. Jack Colyer was evidently an inventive individual, and he had that large collection of American engines from which to draw inspiration. We only know about this example because of Warring's decision to include an illustration in his book. Thanks, Ron!! The Majesco “22”diesel Although the Majesco “45” seems to have been a steady seller for the Majesco company, Jack Colyer’s attention evidently became increasingly drawn towards model diesels as 1946 wore on. The rapidly rising interest in diesels among British modellers almost certainly had much to do with this change in focus.

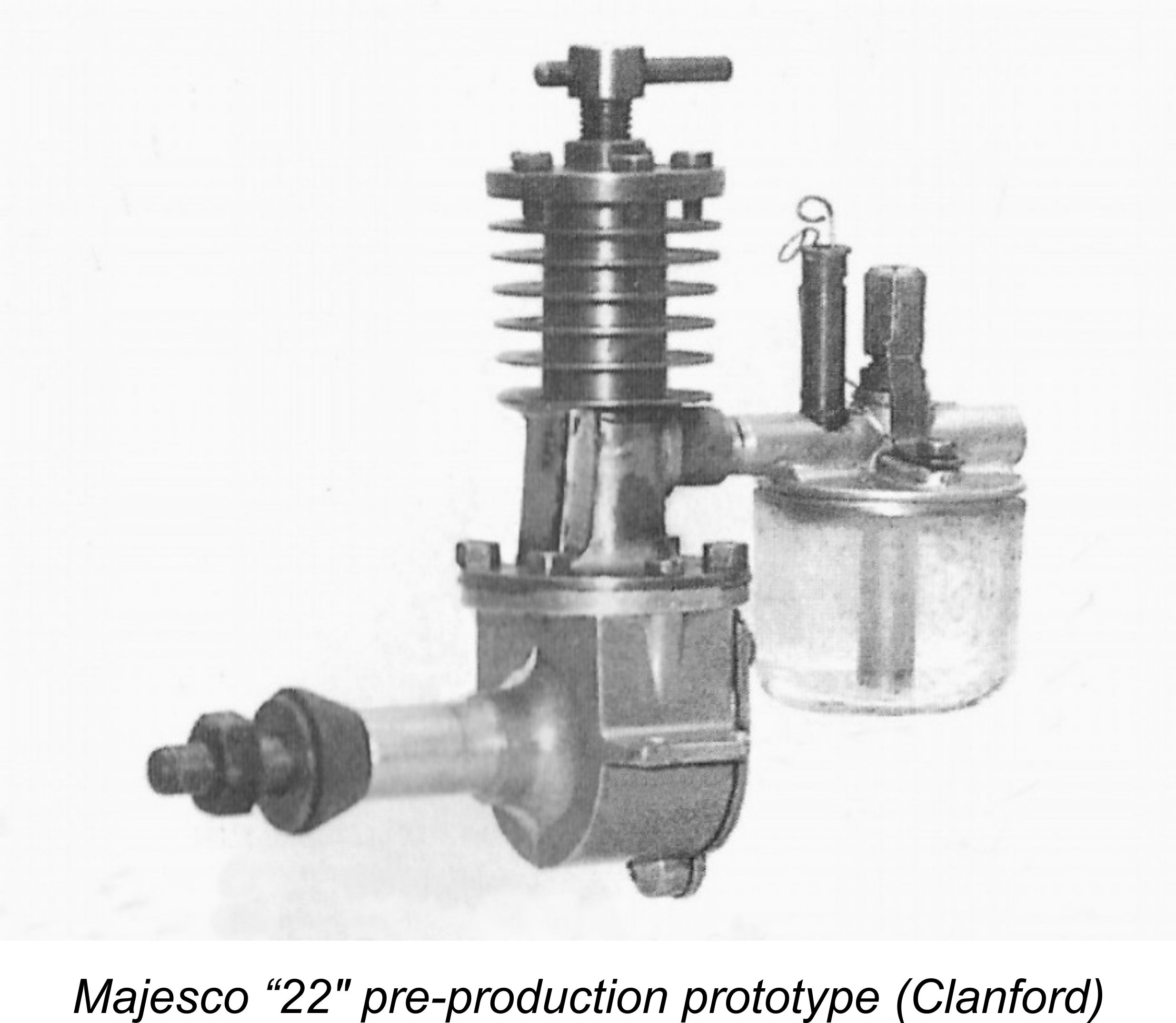

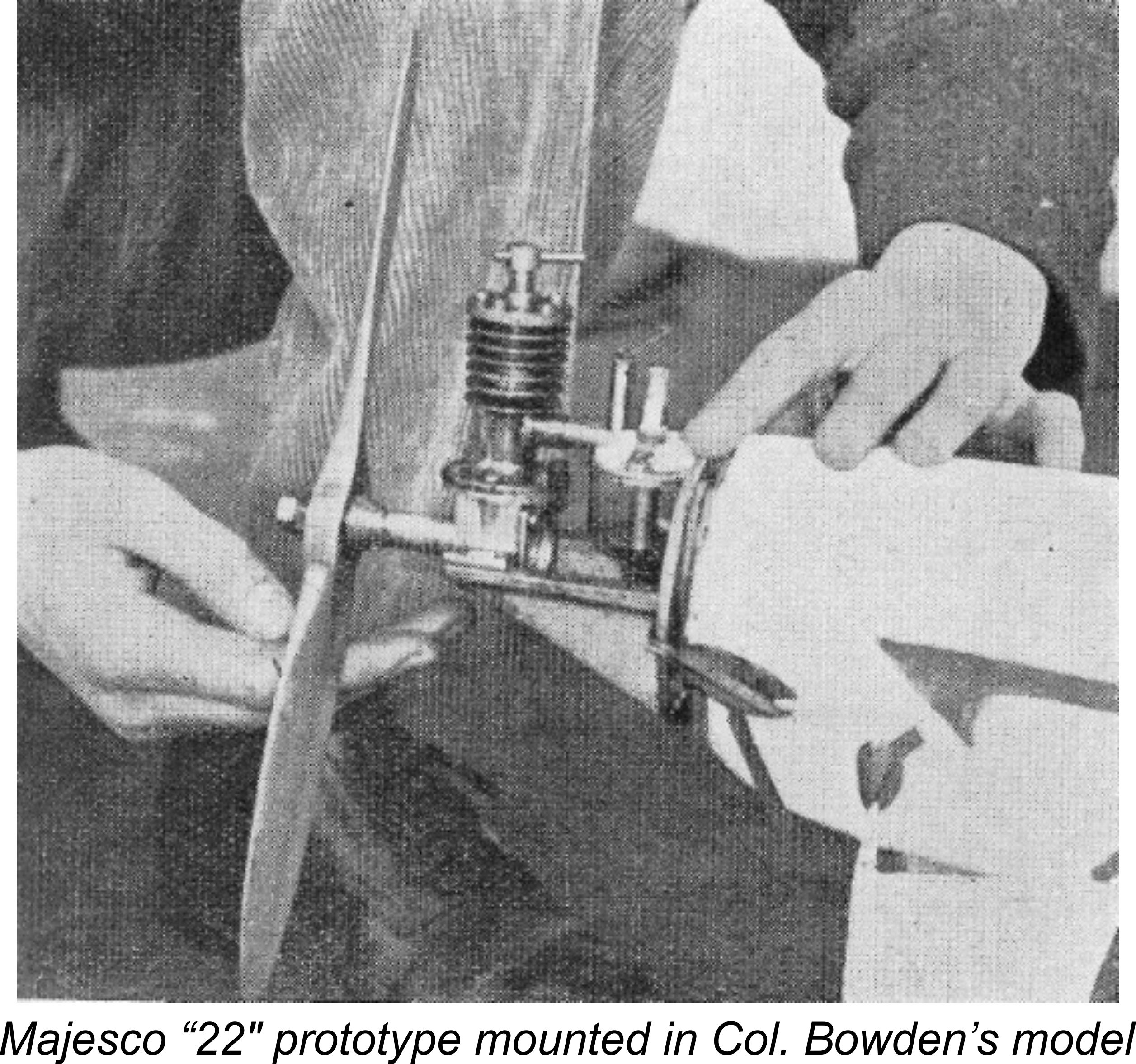

On the other hand, the “22” was mentioned in the articles by Col. C. E. Bowden which appeared in the January and February 1947 issues of "Model Aircraft" under the heading "Rich Mixtures". The January article refer to a "Myeses" 2 cc diesel which was reportedly made to Col. Bowden's personal order and had subsequently been put into limited production. The February article corrected the name, stating that in reality it should have been named as the Majesco.

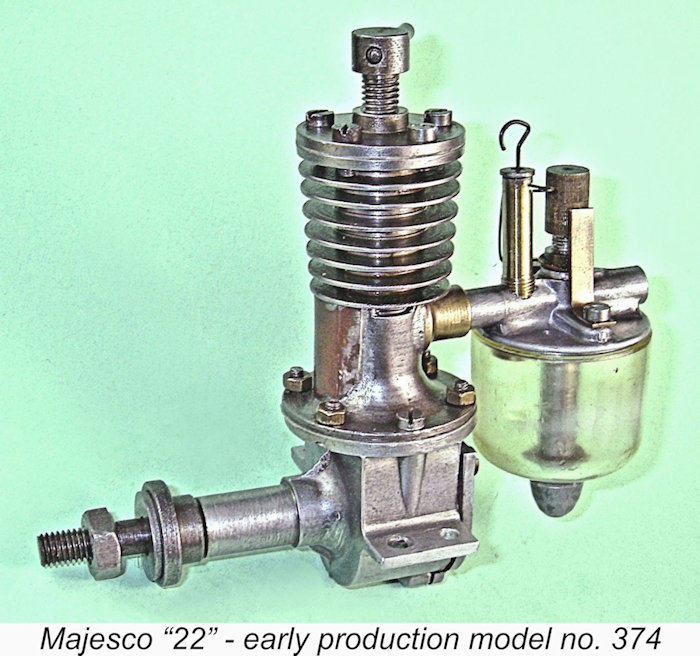

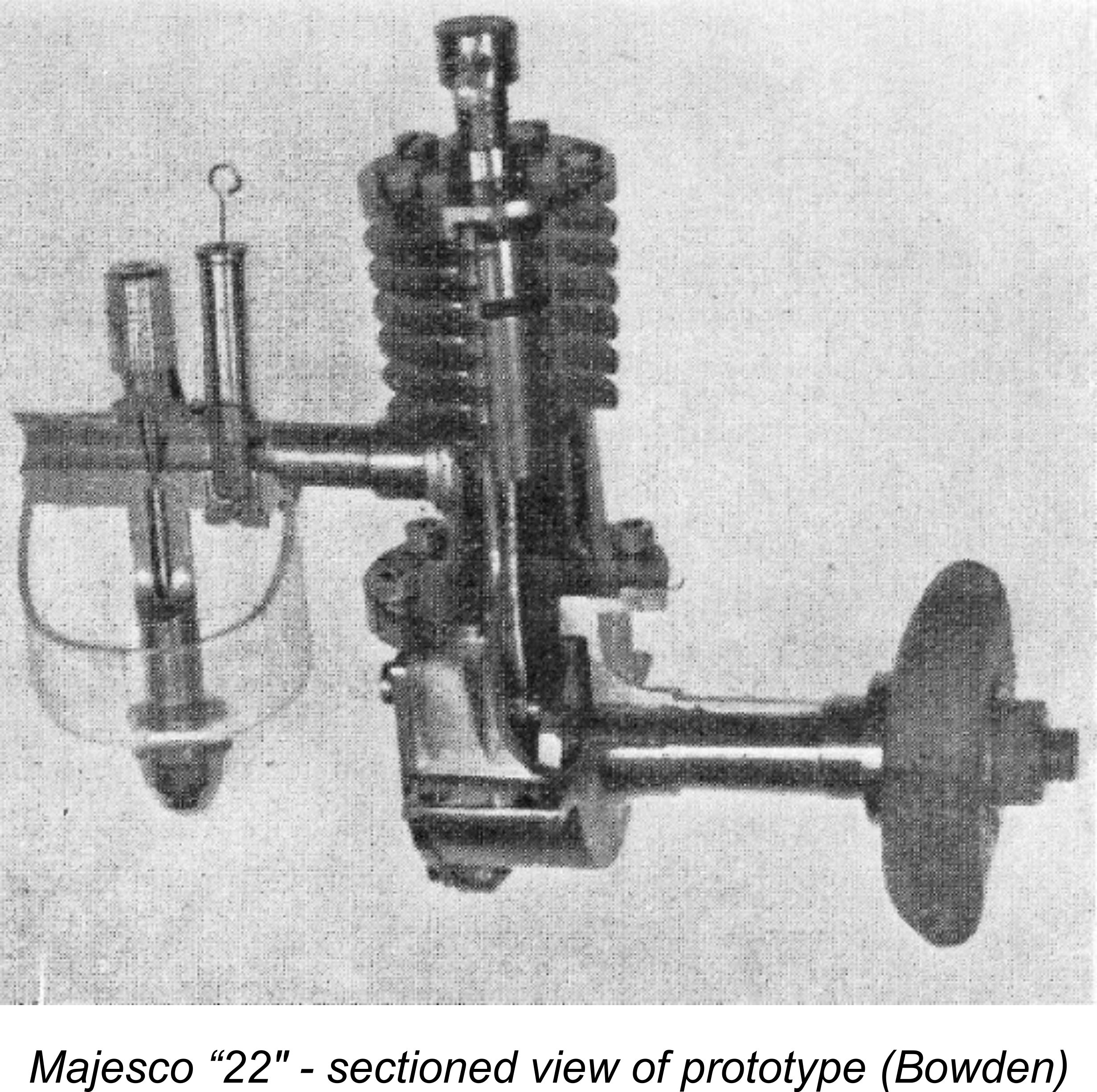

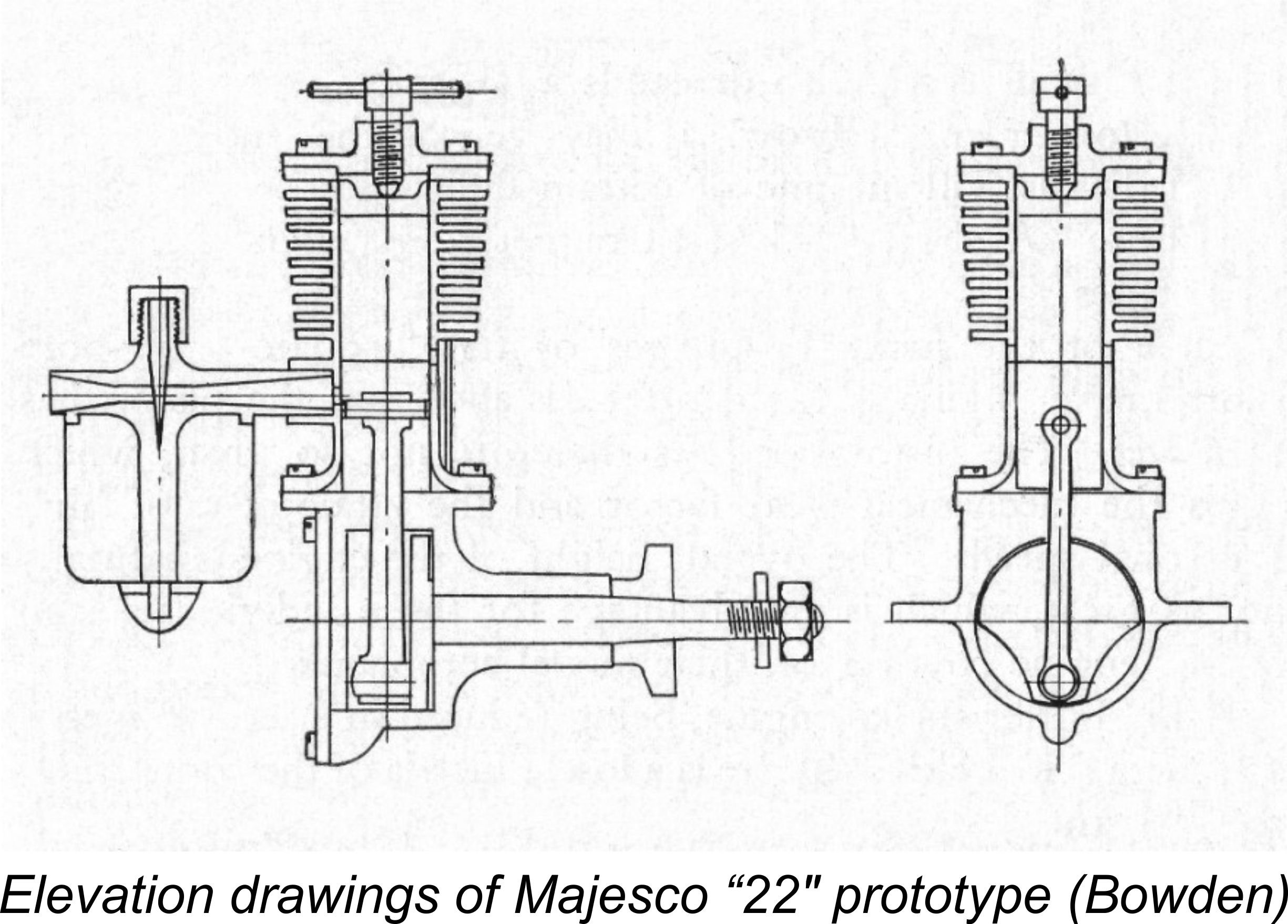

Like its larger spark ignition predecessor, the new diesel model was made available both ready to run and in kit form. It was based upon the same crankcase casting as the earlier “45” sparker. However, the internal geometry was significantly changed. At the time in question, the employment of long strokes was widely considered to be the most effective approach to model diesel construction, taking advantage of their ability to develop high torque figures while minimizing piston area with a consequent reduction in combustion stresses on the working components. Jack Colyer went along with this in his new diesel design, using bore and stroke measurements of 0.500 in. (12.70 mm) and 0.6875 in. (17.46 mm) respectively for an actual displacement of 2.21 cc (0.135 cuin.). Thus the “22” actually had a slightly longer stroke than the larger “45” model! My example of the initial version of the Majesco "22" turns the scales at a hefty 214 gm (7.55 ounces), a little heavier than the companion "45" sparkie.

First, I should point out that British engine designers of the period almost invariably worked in dimensions of a fraction of an inch rather than decimal figures. This meant that once a set of fractional dimensions had been decided upon, the engine's precise displacement came out to be what it was! The die-hard practise of working in fractional dimensions quite escapes any rational explanation given the fact that the designers invariably quoted the resulting displacements in cubic centimetres (cc)! Go figure ...... Furthermore, at the time in question the “magic” displacement of 2.5 cc (0.151 cuin.) had yet to be adopted by the FAI for International competition, resulting in the competitive use of engines covering a wide displacement range in the same contest categories. Under these circumstances, no particular displacement really had much of an edge over another. The only issues were what size of model was desired and whether or not a given engine could do the job of flying that model to the standard required.

Seen in this 1947 context, there was nothing at all extraordinary about Majesco Miniature Motors releasing what was doubtless intended to be a “popular” new model with a displacement of 2.21 cc. It was only when the British Class 1 (later ½A) displacement limit was set somewhat confusingly at 1.5 cc and later when the 2.5 cc limit was formally adopted by the FAI that the attention of manufacturers became increasingly focused on engines built to the new competition limits, leaving the 2.2 cc displacement category as something of an orphan lying between competition classes. By that time, the Majesco range was long gone.

The bypass was relocated to the front of the cylinder, being formed from a brass channel which was soldered onto the cylinder. The motivation for the relocation of the bypass was clearly the designer’s wish to use twin exhaust ports, one on The fuel system appeared to be carried over more or less directly from the “45”, the sole evident difference being the addition of a vertically oriented plunger-type fuel cut-out. Naturally, a cut-out was required for the diesel model since the engine could no longer be shut off simply by switching off the ignition circuit. Contrary to expectations, this fitting did not contain a coil spring, being activated instead by a combination of gravity and induction manifold suction. Its operational effect was to block the induction tube between the fuel jet and the cylinder's induction port. In addition, the boss for the screw-in venturi was soldered to the steel cylinder rather than being formed integrally with it. This latter change was of course dictated by the different form of construction.

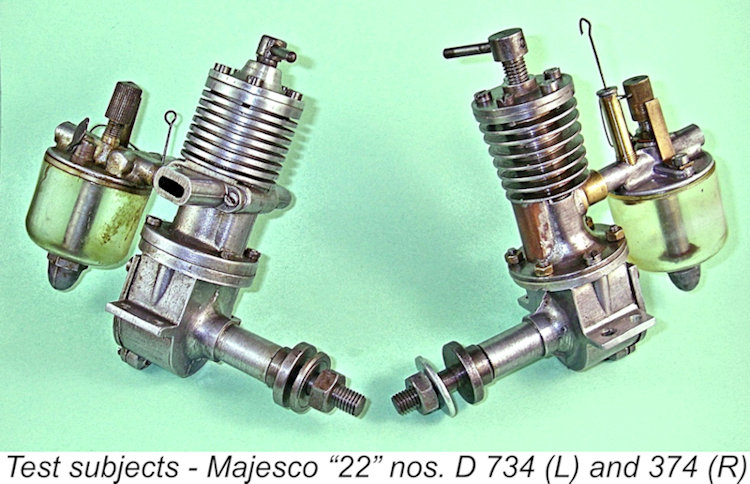

My own previously-illustrated example of this early model, engine number 374, features the seven-fin cylinder, but otherwise appears to be identical to Col. Bowden's examples. The serial number implies that as many as 400 examples may have been made in this form.

The engine used a cast iron piston operating in a steel cylinder liner. The con-rod in this instance was of hardened steel, a not-uncommon choice for diesels at this early stage of development, although not an ideal material choice for this component - hardened steel on hardened steel doesn't wear too well.

In his “Collector’s Guide to Model Aero Engines”, the late O. F. W. Fisher Otherwise, the construction of the “22” appears to be well up to contemporary standards of quality among British model engine manufacturers. Indeed, it’s actually better made than many of its competitors, especially where it counts. All working fits in my own illustrated examples are outstanding.

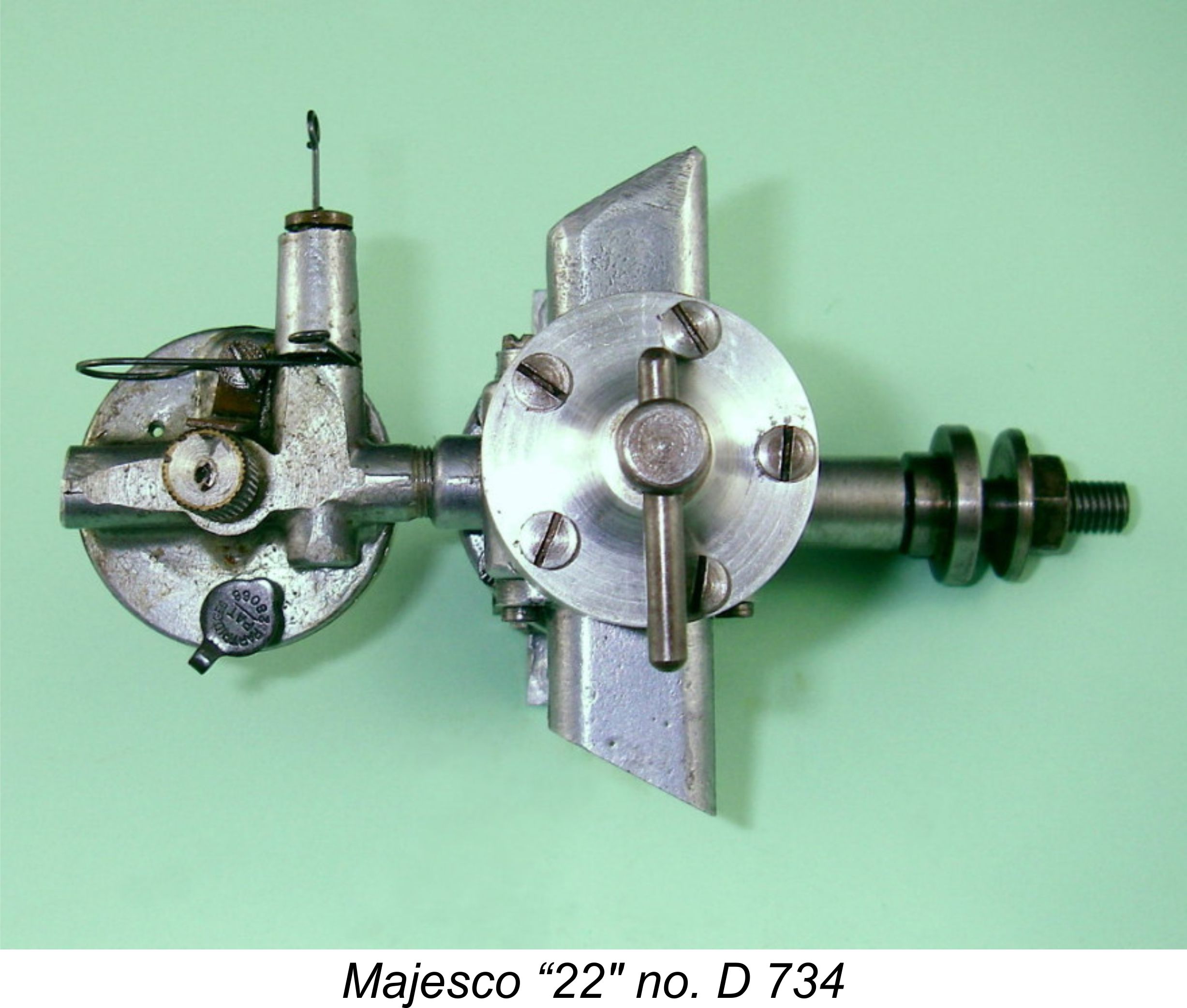

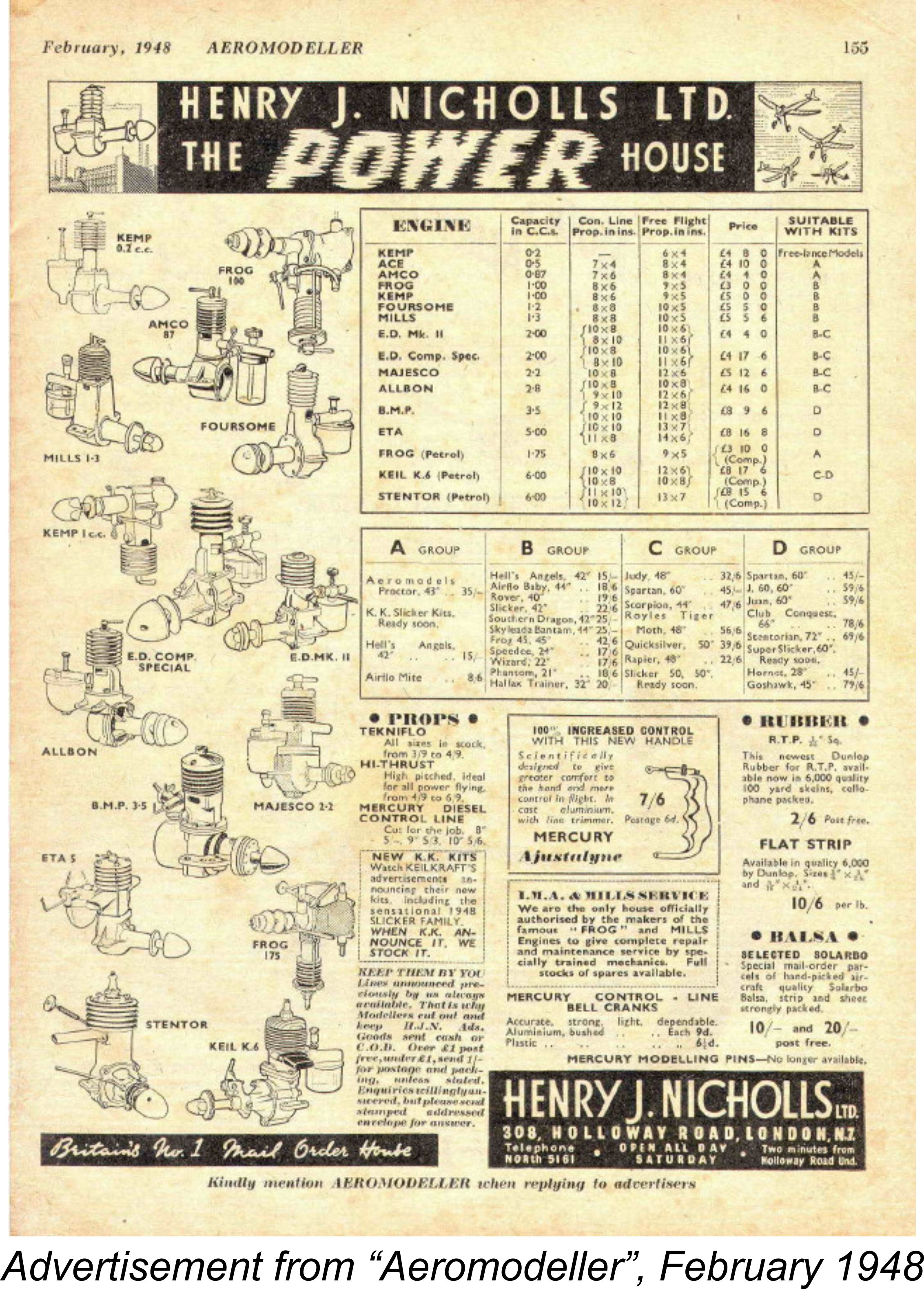

This made the Majesco one of the most expensive engines in its displacement category. Ron Warring tells us that later in 1948 the price was dropped to £3 10s 0d (£3.50) - a far more competitive figure, although Warring was almost certainly referring to the engine’s inventory clearance price. It’s worth noting in passing that the only Majesco model which appeared in Nicholl's February 1948 advertisement was the second variant of the “22”. This is consistent with Fisher’s statement to the effect that the firm’s attention was very much concentrated upon the manufacture of this model, the result being that the “22” was reportedly produced in relatively substantial numbers. This statement is supported by the known serial numbers. It appears that when the second variant of the "22" appeared, a “D” prefix was added to the number, presumably to indicate that the engine in question was a diesel. The one outstanding question is whether or not the numerical sequence was restarted at D 1 or simply carried on from the sequence for the original model, with the D added to underscore the change in design.

Quite apart from its price, a factor which must surely There is an unsubstantiated possibility that Colyer may have experimented with other diesel prototypes during the production life of the Majesco "22". The 6.3 cc diesel in my collection which is illustrated here with the Majesco "22" prototype may well be a case in point. The resemblance of its cylinder design to that of the far smaller Majesco "22" prototype variant is striking, as is the general similarity of its construction arrangement apart from the rotation of the twin-exhaust cylinder through 90° to bring the induction system to the left-hand side of the engine, presumably to minimize its installation length requirements. Indeed, this very unusual orientation of the induction system may represent a Colyer "signature" of sorts - he used a similar orientation in the design of his Majesco Mite diesel, as we shall see in a later section of this article. The connection of Colyer with my unknown 6.3 cc diesel cannot now be proved, but it remains an intriguing and logical possibility! Certainly, the quality of its construction is beyond reproach. The engine starts easily and runs very well indeed. Full details may be found in my Wotizit pages. The Majesco “22” on test

At the time when I was writing the original version of this article for MEN back in late 2014, the only example of the Majesco "22" that I had on hand was second model no. D 734. Accordingly, that was the example that was tested for that original article. However, I have subsequently acquired the superb illustrated example of the early integral-fin variant, engine no. 374, from my good mate Dean Clarke of Cre8tionworx Engineering in New Zealand. Accordingly, I was placed in a position to conduct a comparative test of the two variants head to head. Can't pass up an opportunity like that! Needing little encouragement to put this idea into practise, I tested both models at the same session using the same fuel and calibrated suite of test props. The fuel used was a 35/35/30 blend of kerosene, ether and SAE 60 mineral oil. Low-speed diesels of the pioneering era generally run fine on such a brew, which is kind to the engines and has the added benefit of not leaving them soaked in potentially gum-creating castor oil residue. Castor oil is an unsurpassed lubricant and preservative, but it does have a downside ................. First into the test stand was the earlier variant, engine number 374. Mounted in the stand with a Taipan 11x7 airscrew fitted, it felt absolutely superb when flipped over, doing great credit to Dean Clarke's fettling skills. It didn't feel as if it was in need of any running in, but I decided nonetheless to run half a dozen tankfuls through it on a rich mixture with slightly reduced compression, just to be safe.

Thankfully, once I had got the measure of this behavior, it never took that many preliminary flicks to get the engine to the point of starting. I certainly wouldn't rate it as a routine first-flick starter, but I would classify it as a very dependable starter, never requiring an excessive level of effort to get it going. I actually found that once the settings had been established, the port prime was unnecessary - two or three finger chokes invariably sufficed, after which two or three starting flicks generally had it going. Once running, the engine was extremely smooth in operation, with vibration levels at the relatively low speeds involved being well within manageable limits. At higher speeds, I reckon that it would be a bit of a shaker, but the test results confirmed that high speeds are not in this engine's repertoire!

The cut-out worked perfectly, greatly speeding up the testing. The main thing to remember was to re-set the cut-out to the running position before attempting a re-start following a prop change - I got caught out once myself in this manner, giving both my flicking finger and my vocabulary plenty of unnecessary exercise before I realized my error! Apart from that one self-induced hiccup, testing this engine was a real pleasure, and the necessary prop/RPM data were soon recorded. Then it was the turn of second model number D 734. I had tested this one way back in 2014, but a fair comparison with its predecessor required that I test it again.

Response to the controls was excellent at all speeds tested. Both controls held their settings perfectly while remaining fully adjustable at all times. Accordingly, the establishment of optimum settings was very easy indeed, making the testing a real pleasure. Once set, the engine ran very smoothly indeed, draining the tank completely with no apparent suction problems. In terms of its starting and running qualities, I’d have to give this one very high marks indeed. Another aid to enjoyable testing was the fact that this cut-out also worked flawlessly - even Lawrence Sparey (who frequently had trouble with cut-outs) should have been able to get this one to operate! So far so good ....... a set of matching prop/RPM figures for the same suite of test props was soon developed. However, when it comes to the results obtained, it must be said that both variants of the Majesco "22" proved to be rather modest performers, especially for engines of their bulk and weight. For comparison purposes, I've presented the prop/RMP figures for both examples in the same table, along with implied BHP figures and derived power curves.

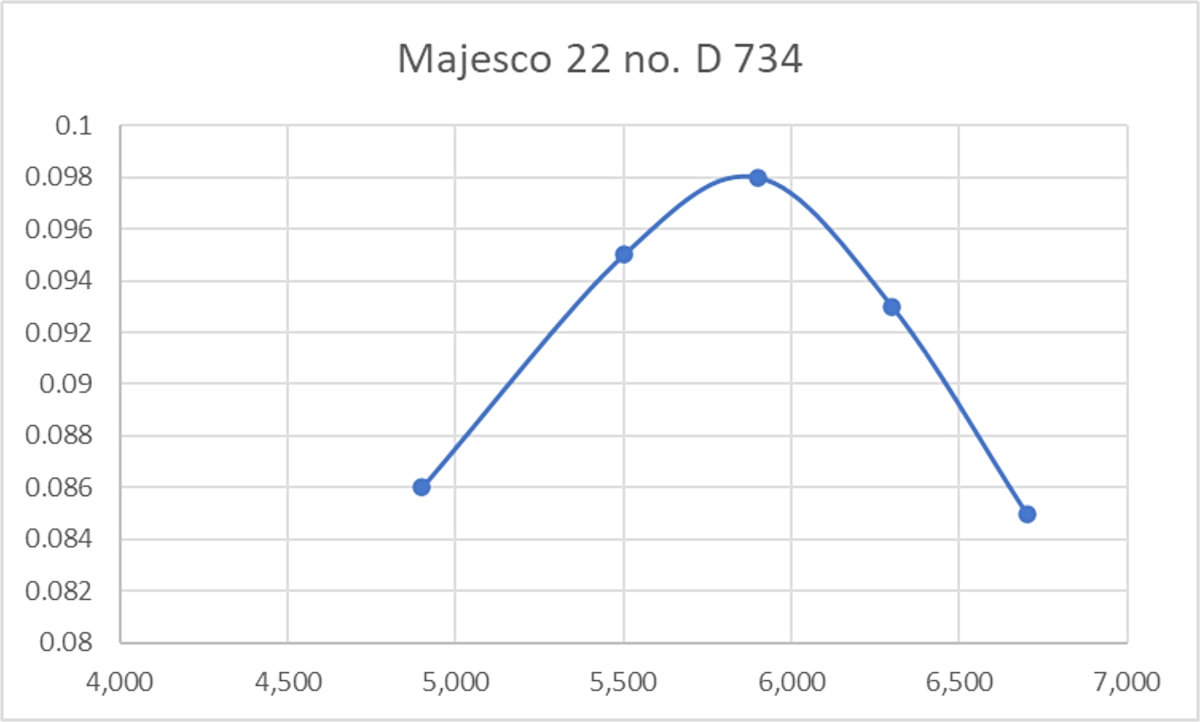

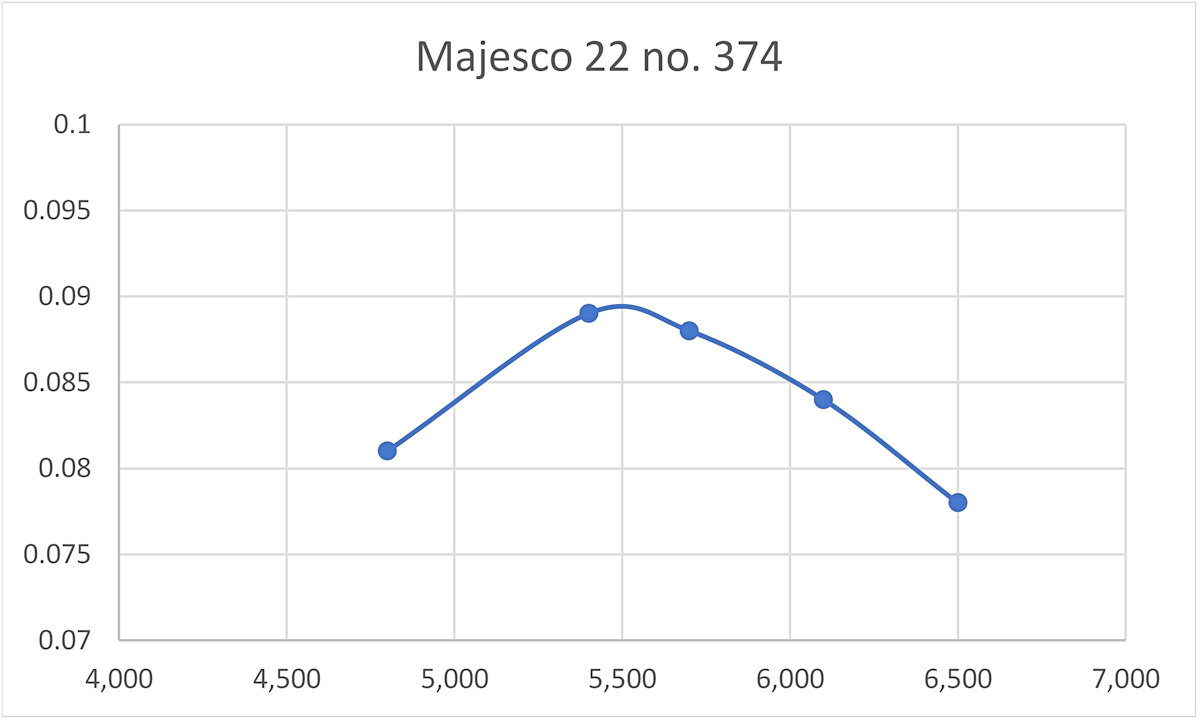

The above figures imply well-defined peak outputs of around 0.090 BHP at 5,500 RPM for early variant no. 374 and 0.098 BHP @ 5,900 RPM for later variant no. D 734. We might conclude from this that the re-configured second variant was the stronger performer, but I'd be cautious in drawing any such conclusion - the difference is well within the range of variation to be expected from two examples of the same series-produced engine, especially ones having different previous use histories. That said, it is likely that if any performance tweaks had presented themselves to Jack Colyer, he would almost certainly have incorporated them into the design of the second variant. The output of the second variant is somewhat less than the figure of 0.109 BHP later reported by Lawrence Sparey for the slightly smaller and considerably lighter 2 cc E.D. Comp Special ("Aeromodeller", May 1948), and also well down on the prop/RPM figures obtained in my own previously-published tests of the admittedly larger Allbon 2.8 model, which may be found in my separate review of the Allbon 2.8 diesel. However, context is everything in such matters! It must be recalled that the Majesco "22" predates both the Comp Special and the Allbon 2.8 by a full year. Its nearest contemporary was the slightly lower-displacement 2 cc E.D. Mk. II, for which my own testing indicated a peak output of around 0.089 BHP @ 7,000 RPM. In terms of specific output, the Majesco’s figure of 0.043 BHP/cc is in the same general ballpark as the equivalent figure of 0.051 BHP/cc reported by Sparey for the slightly higher-displacement Allbon 2.8, which dated from late 1948 in the form in which Sparey tested it ("Aeromodeller", December 1948). By the standards of its late 1946 release date, the Majesco was well in the hunt.

Indeed, the very steady and readily adjustable performance characteristics of the Majesco along with its easy and dependable starting plus its highly functional cut-out were probably exactly what most early post-war modellers required. It was only when control line became a major preoccupation that all-out performance became a dominant factor in an engine’s marketability. The recommended prop sizes noted by Ron Warring do seem a little offside based upon these results. The 12x6 which is cited as the suggested free flight prop would pretty much bring the Majesco to its knees, at least in its APC guise. I would have thought that far better results would be obtained with an 11x6, which the engine turns at only a little below its peak, or perhaps a 12x4. Based upon its known power absorption coefficient, an APC 8x8 would take the engine well past its peak even on the bench, thus appearing to be a poor choice for control line. However, a “slower” 8x8 having wider blades might work just fine. Not possessing details of the props on which these recommendations were based, I can’t really settle this question. All that can be said is that for best results the engine would have had to be propped for no more than 6,000 rpm in the air. The Majesco Mite Diesel

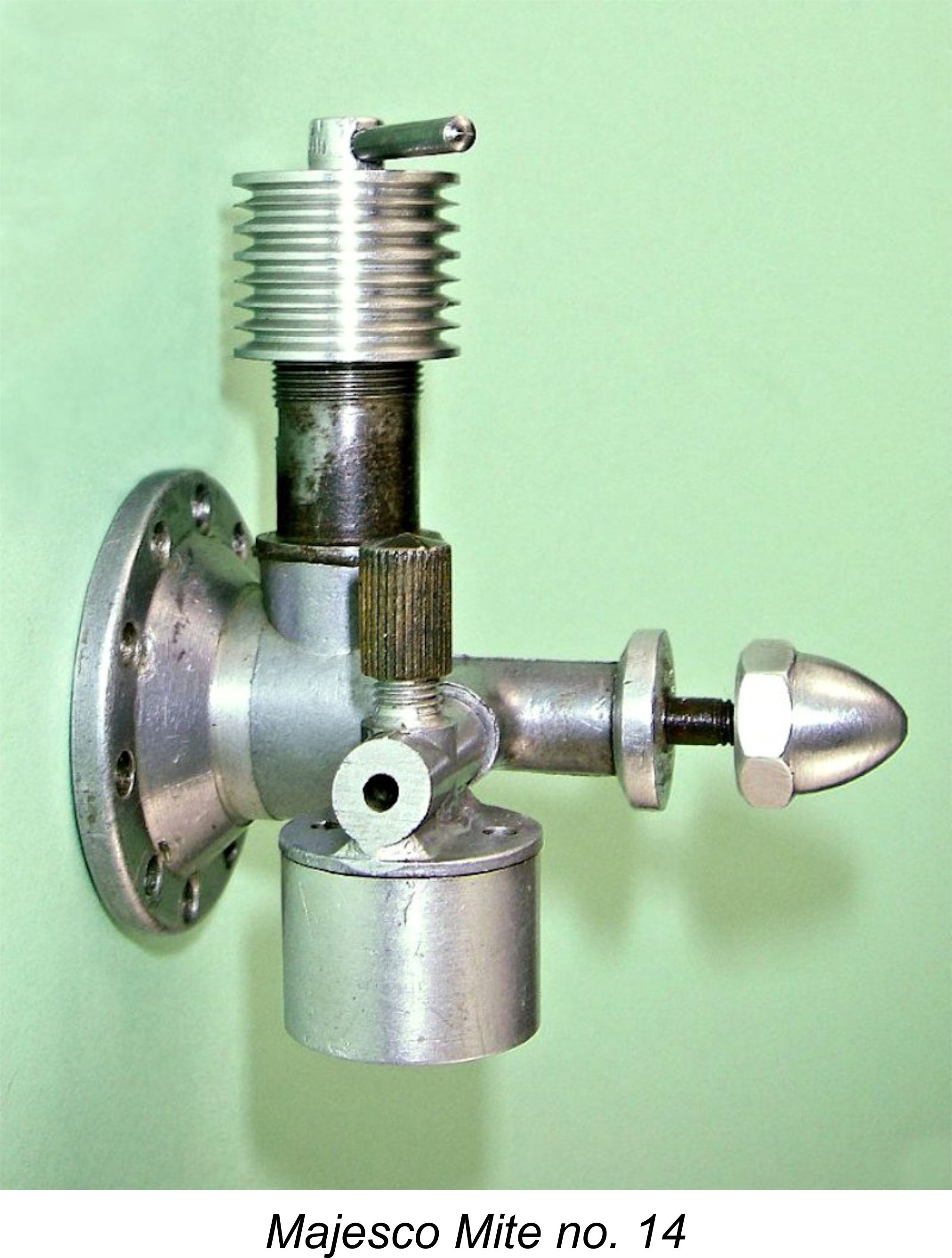

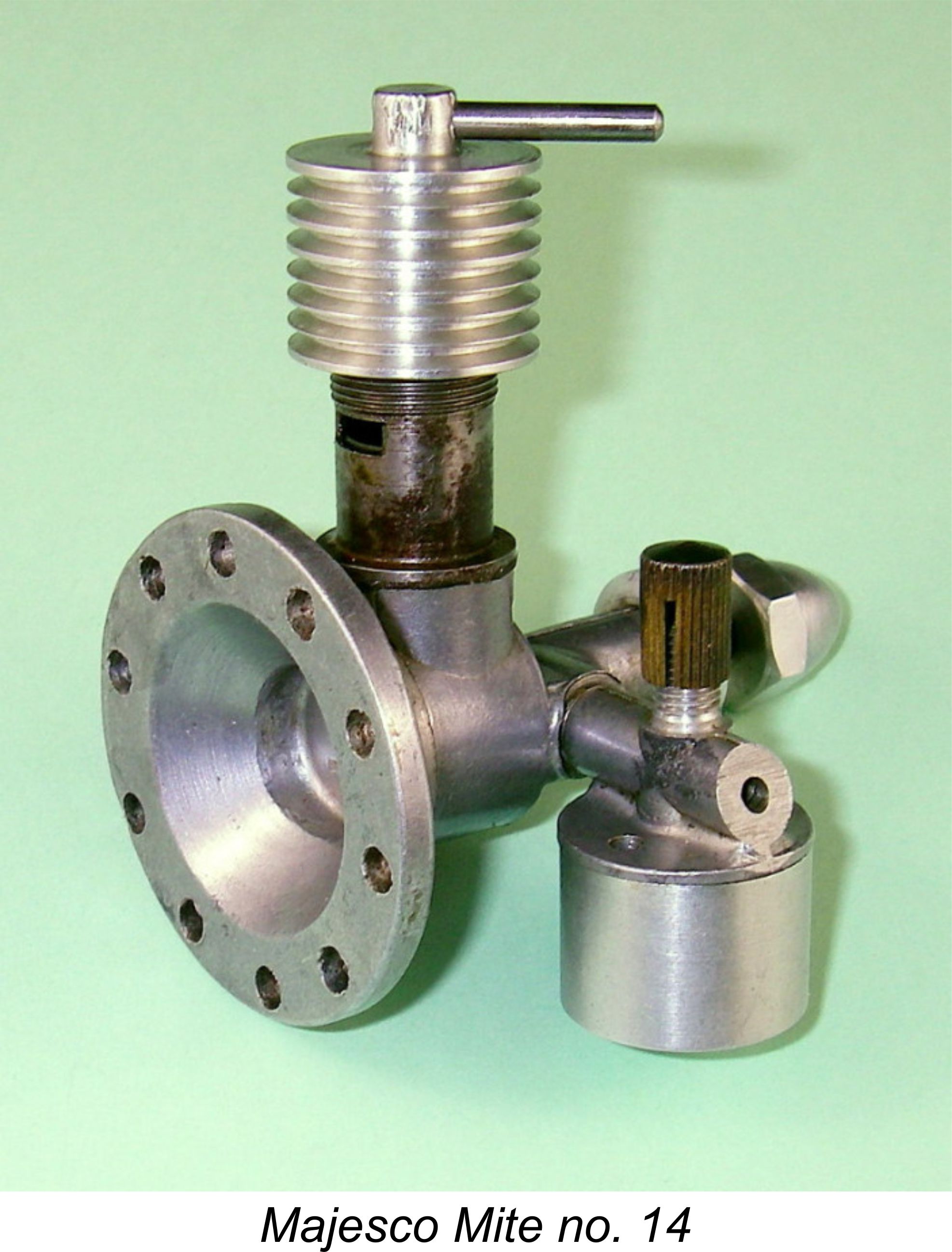

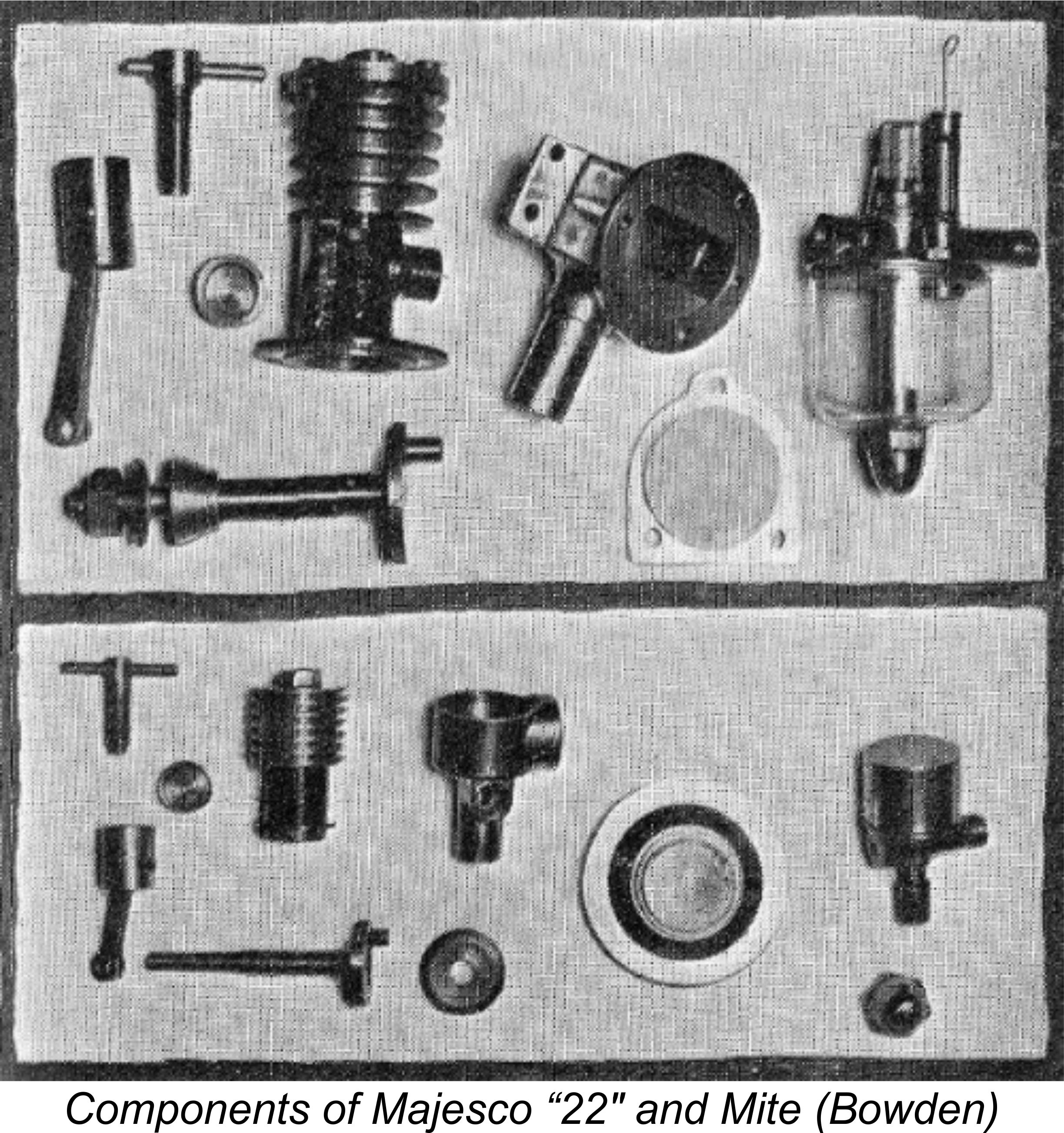

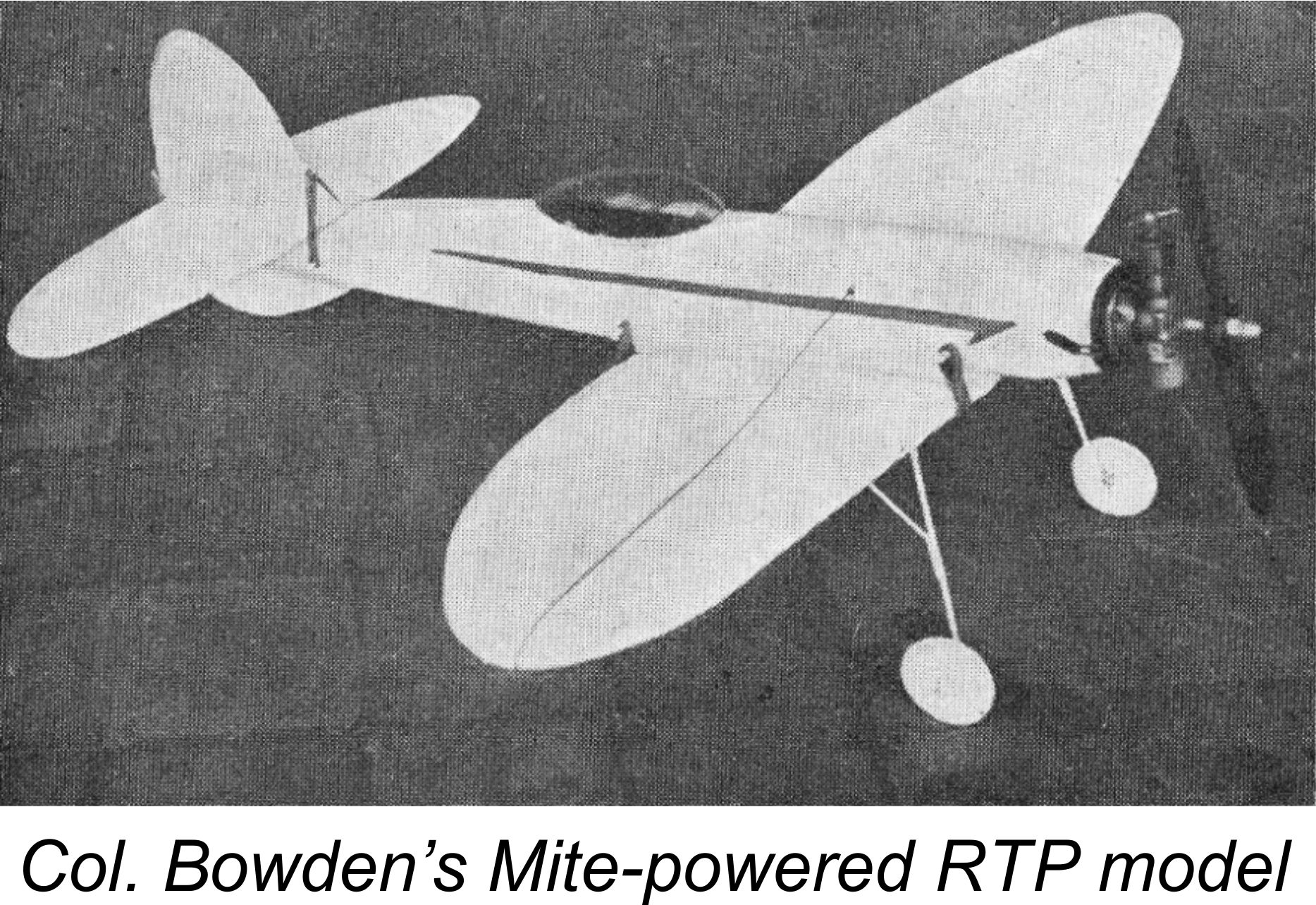

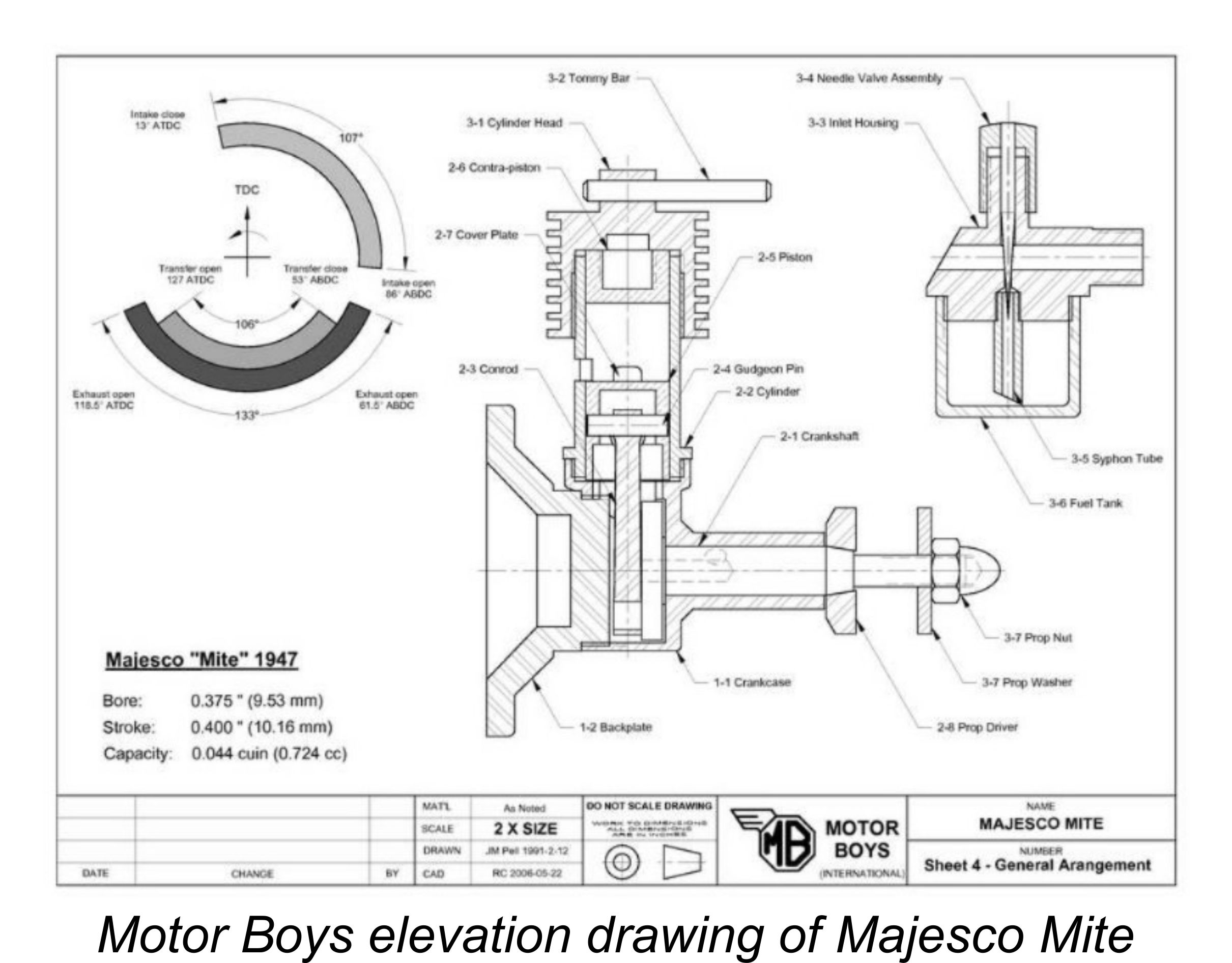

In fact, the Mite appears to have been introduced quite soon after the “22” diesel already described, almost certainly in early 1947. In the previously-mentioned article by Ron Warring which appeared in the Ian Allan publication "Power Models", Warring mentioned that the prototype Majesco Mite had just been finished at the time of his December 1946 visit with Jack Colyer at Littlehampton. Moreover, in his previously-cited "Rich Mixtures" article which appeared in the January 1947 issue of "Aeromodeller", Col. Bowden referred to a Colyer "0.5 cc diesel". He evidently got the displacement wrong, since the "Rich Mixtures" article in the February 1947 issue named this engine more precisely as the "Mite". Taken together, the statements by Warring and Bowden appear to confirm that the production version of the Majesco Mite appeared in early 1947, shortly after the debut of the "22". Oddly enough, the Mite never appeared in any Majesco advertisements during the year 1947. Despite this, it had undoubtedly been in production for some time as of mid 1947 since it was featured in Col. Bowden’s previously-mentioned article on power topics in the June 1947 issue of “Aeromodeller”. The gallant Colonel had clearly been using the Mite for some time when that article was written. The engine was also a prominent inclusion in the 1947 first edition of Col. Bowden’s book “Diesel Model Engines”, complete with photographs of a surprising number of models that Col. Bowden had built for it prior to the appearance of the book. Presumably all sales had been made directly from the manufacturer to purchasers in the immediate area, without any perceived need for more widespread advertising. The contents of Col. Bowden’s book make it abundantly clear that there was a close association between Col. Bowden and Jack Colyer, doubtless arising in part from their common residency in the vicinity of Bournemouth as well as their shared enthusiasm. One of these illustrations shows Colyer holding Bore and stroke of the Mite were 0.375 in. (9.52 mm) and 0.4062 in. (10.32 mm) respectively for a displacement of 0.735cc (0.045 cuin.). As far as I’m presently aware, it was the first engine of this displacement to appear on the British market, presaging the later appearances of such models as the Mills .75, the 0.79 cc Wilsco 79, the Allbon Merlin 0.76 cc, the FROG 80 and the 0.81 cc E.D. Pep. The little The Mite was built around a cleanly die-cast crankcase featuring a plain bearing cast in unit. Unlike the other models in the Majesco range, the engine was arranged strictly for radial mounting. A cast iron piston was used together with a screw-in steel cylinder. The con-rod was made of aluminium alloy. The engine employed crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction with an unusual side-mounted venturi and fuel tank. Another unusual feature was the method of compression adjustment, which involved rotation of the entire screw-on cooling jacket on the externally-threaded upper cylinder using a lever mounted in a spigot at the top of the jacket. This mirrored the approach used by E.D. in their Mk. II diesel, although the Majesco arrangement with built-in lever was far more convenient (and cheaper!) than E.D.’s “penny slot”. Transfer was accomplished through a single rather constricted bypass passage formed in the left side of the cylinder wall (facing forward in the direction of flight). The upper portion of this passage was created by the simple expedient of cutting a slot completely through the relatively The slot naturally could not be carried through the cylinder installation flange. Accordingly, the lower portion of the bypass passage was created by milling a flat into the lower wall of the The exhaust port was oriented at 90 degrees to the bypass passage, the screw-in cylinder being shimmed so as to have the exhaust discharge to the rear. This is not an incidental arrangement - in order for the composite bypass just described to work, the engine has to be assembled in this manner so that the two elements of the bypass passage line up correctly. A serious design flaw needs to be mentioned at this point. The amount of thread available for cylinder installation purposes is very marginal indeed. This issue is exacerbated by the fact that the cylinder needs to be secured quite tightly in order to maintain the correct alignment of the ports against the considerable turning forces generated by compression adjustments. Moreover, the amount of metal available to restrain the threaded socket for the cylinder in the case against the considerable wedging stresses caused by the Interestingly enough, Col. Bowden’s book includes an illustration showing both the “22” and the Mite in component form. The “22” is clearly the early pre-production version with all-steel cylinder, which appears to confirm that the initial appearance of the Mite was more or less contemporary with that of the original variant of the “22”. Significantly, the Mite is shown as featuring a conventional T-shaped compression screw which is separate from the cooling jacket. It appears that this too may be a pre-production model, since the later production versions of the Mite invariably featured the previously-noted moving jacket form of compression adjustment with the compression adjustment arm mounted directly in a spigot at the top of the jacket. Presumably this was a weight-saving measure. I would personally have stayed with the compression screw arrangement - the torque applied to the cylinder during compression adjustments would be greatly reduced.

According to Ron Warring, the recommended airscrew for free flight was an 8x4. No recommendation was noted by Warring for control-line use, although Col. Bowden’s book included an illustration of an example in tethered Round-the-Pole service. It’s certainly true to say that the Mite as supplied was very poorly configured for control line.

It seems significant that the Mite did not appear alongside its larger 2.2 cc sibling in the previously-mentioned February 1948 advertising placement from Henry J. Nicholls. The impression created by this omission is that production of the Mite had already ceased as of early 1948. This is consistent with the comment made by Fisher in his “Collector’s Guide to Model Aero Engines” that the Mite was manufactured in very small numbers and that Majesco for the most part concentrated on their 2.2 cc diesel model. Certainly, original Mites are very rarely encountered today. Probably at most only a hundred or so were made, if that.

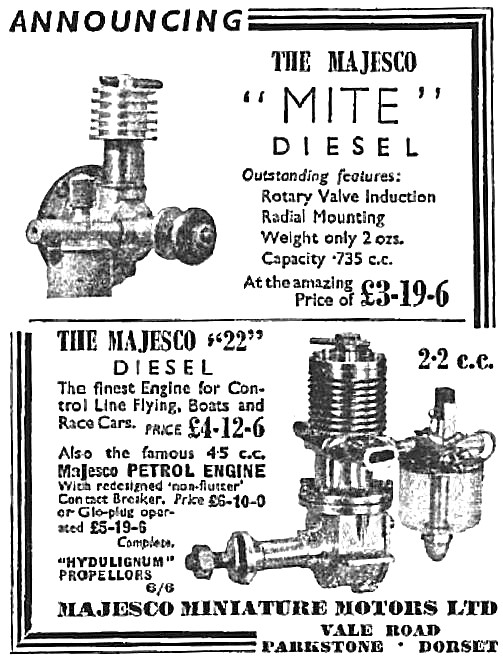

His response to this issue was to "announce" the engine to a national audience through its belated inclusion in some of his 1948 advertising. The June and July 1948 advertisements in "Aeromodeller" as reproduced here at the left "announced" the Majesco Mite diesel at a price of £3 19s 6d (£3.98), as well as continuing to promote the "22" diesel at £4 12s 6d (£4.63) and the "45" in both spark ignition and glow-plug configurations. This "announcement" of the Majesco Mite came some 18 months after the engine is definitely known to have appeared in reality. These advertisements probably explain why an erroneous introductory date of 1948 has sometimes been cited for the engine. Jon I The Mite would have met all of these requirements very well. However, its characteristics would have told heavily against it when viewed in a control-line context. As much as anything else, this factor probably had much to do with the engine's short market tenure. Engines of this rarity invariably attract the attention of replica constructors. Examples of the engine in replica form may be encountered from such makers as Ivan Prior, although such replicas are probably at least as rare as the originals! In order to provide today’s model engineers with an opportunity to construct their own close replica of this extremely rare little engine, the late and much-missed Ron Chernich produced a Motor Boys plan of the engine from rough drawings provided by Ken Croft. I’ve illustrated a fine example of a replica built from these plans by Les Stone. All I can say is - well done, Les! The Majesco Mite on Test None of the Majesco engines were ever subject to the attentions of any of the engine testing gurus of their era. This seems to be an omission which should be rectified! Given the fact that I was fortunate enough to have a fine example of the Majesco Mite on hand for evaluation, there appeared to be little excuse for passing up the opportunity to mount it on the test stand and attempt to form a first-hand impression of its operating qualities. This being the case, let’s get right to it!

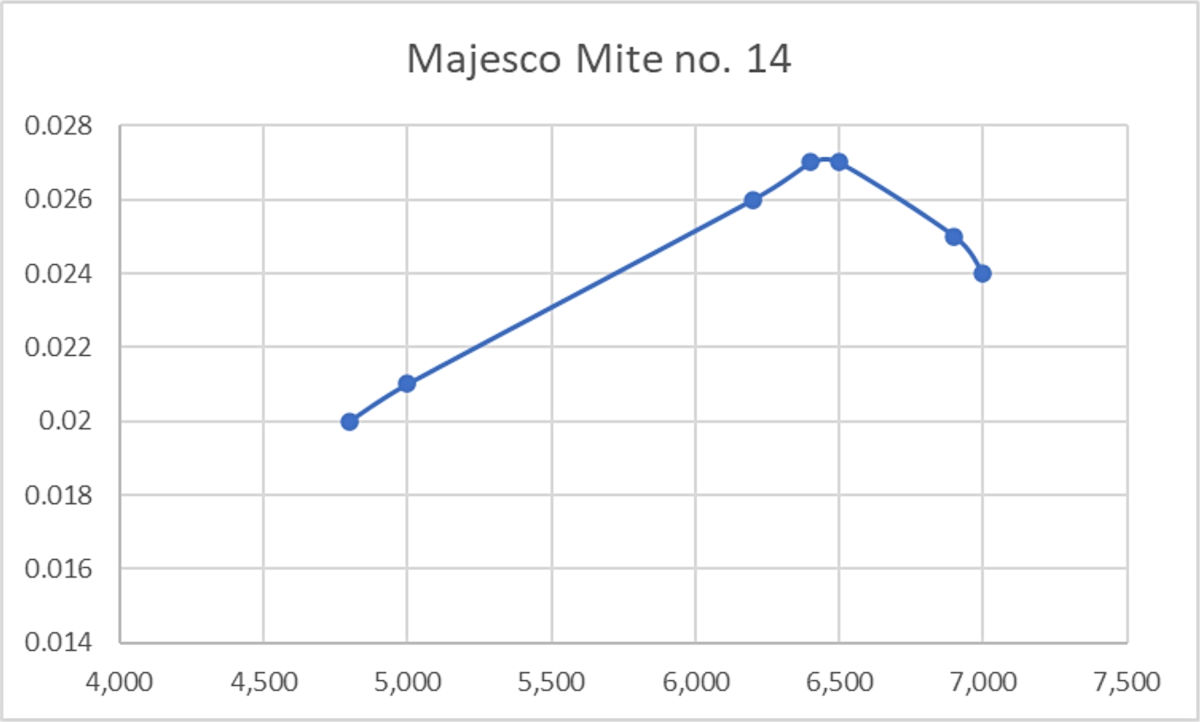

I began with the Mills. I’m always up for any excuse to Then it was the turn of the Majesco. It proved to be another very easy starter, although a That said, the moving jacket form of compression adjustment is definitely far less user-friendly than a conventional comp screw with tommy bar. The control is actually extremely stiff in operation, raising the possibility that it could shift the cylinder in its threaded socket or over-stress the socket in the upper crankcase. Jon Fletcher installed a PTFE (Teflon) washer between the contra-piston and the head, which helped a lot, although the action is still very stiff. A conventional compression screw would undoubtedly be far better. Another issue is the fact that the action of flicking the engine over to start tends to cause the crankcase to unscrew from the backplate radial mount. Once again, the fact that there's relatively little metal in the crankcase to resist the wedging forces created by the backplate thread argues strongly against over-tightening this thread. I adopted the approach of actually holding the cylinder in my left hand while flicking with my right. Once running of course, the engine's torque tends to tighten this thread, so there's no danger of it coming undone while the engine is in operation. It only took a few runs to demonstrate convincingly that the Majesco was not going to get to within a block of the ballpark occupied by the Mills! It was well down on all props tested. It has to be recalled that as a design it dates from well over a year prior to the Mills, but there’s no doubt that its performance falls further short than might have been expected. The relative figures are shown in the following table, along with the derived power curve:

Even allowing for a few seemingly missed settings (probably due to the stiffness of the compression control), the implied output of only some 0.027 BHP @ 6,500 rpm is pretty marginal for anything other than low-key sport free flight applications using lightweight airframes. However, it was for precisely those applications that the engine was arranged. It’s noteworthy that the little Mite turns an 8x4 prop as recommended for free flight at 6,200 rpm, just below its peaking speed. Hence this recommendation appears to be entirely appropriate. So .... certainly not a powerhouse by any means, but a well-made and very user-friendly little engine apart from the unduly stiff compression control. If it has a downside other than its marginal power output, it is that it appears to be somewhat vulnerable to crash damage. The tank is definitely hanging “out there”, and the cylinder installation thread length is pretty marginal. Definitely one to keep out of the ground!! Having said this, there can be no doubt that the Mills simply buries the Majesco in performance terms as well as being a far more practically-arranged design. Once the Mills appeared on the market, it’s my considered opinion that the Majesco would have stood no chance at all. Even the AMCO .87 of July 1947 would have had far greater appeal to the average modeller. The End of the Line

Further confirmation of this is to be found in the pages of Ron Warring’s previously-mentioned book “Miniature Aero Motors”. The Majesco “45” sparker and the Majesco Mite and “22” diesels were all included in the data tables which formed an appendix to Warring’s book. However, all of these models were specifically noted by Warring as being out of production. Since there’s a good deal of internal evidence in the form of inclusions and exclusions to suggest that the book was mostly compiled between late 1948 and early 1949, this seems to prove yet again that all Majesco production had ceased as of late 1948. So the Majesco range was gone after a market presence of only some 30 months or so. Presumably Jack Colyer found that he could not compete in the evolving British marketplace with the mass-production capabilities of firms such as E.D., International Model Aircraft (FROG) and Mills and still make a livable income. In fact, the manufacture of the Majesco engines may well have been a labour of love which was in fact a sideline to Colyer’s main employment activities. Regardless, a sad end to what was surely a very sincere attempt by a genuine enthusiast to offer a quality product to his fellow modellers. Jack Colyer lived on to the age of almost 81 years, passing away on December 18th, 1989 only a few days before his 81st birthday. He probably thought that his long-ago efforts had been forgotten, and it's been a pleasure to create this article to confirm that this isn't so! _____________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published February 2015 Updated February 2020 (test of Majesco "45") Second update June 2025 - additional dates, images and test of early Majesco "22" Third update December 2025 - information on the pre-WW2 Cloud connection |

||||

| |

Here we take what I believe to be the first ever in-depth look at a model engine range which was one of the early post-WW2 pioneers of the British model engine manufacturing industry but which failed to survive in the highly competitive model engine market which developed very rapidly during that period. I’ll be examining the all-too brief story of Majesco Miniature Motors, who manufactured a number of highly serviceable engines to very acceptable standards but were unable to keep up with the rapid technical advances in model engine design which characterized the early post-war years.

Here we take what I believe to be the first ever in-depth look at a model engine range which was one of the early post-WW2 pioneers of the British model engine manufacturing industry but which failed to survive in the highly competitive model engine market which developed very rapidly during that period. I’ll be examining the all-too brief story of Majesco Miniature Motors, who manufactured a number of highly serviceable engines to very acceptable standards but were unable to keep up with the rapid technical advances in model engine design which characterized the early post-war years.  Given the inevitable progressive corruption of material on a long-term web-site that is no longer being maintained, I imagine that similar action on my part will become necessary for other MEN articles as time goes by. I will do my best to monitor this situation and to respond accordingly.

Given the inevitable progressive corruption of material on a long-term web-site that is no longer being maintained, I imagine that similar action on my part will become necessary for other MEN articles as time goes by. I will do my best to monitor this situation and to respond accordingly.

The designer and manufacturer of the Majesco engines was a gentleman named John Edward Snelling Colyer (1908 - 1989), always known to one and all as "Jack" Colyer. Apologies for the abysmal quality of the attached image, but it’s the only one that I've so far been able to find. If anyone has a better image of Colyer, please share it!!

The designer and manufacturer of the Majesco engines was a gentleman named John Edward Snelling Colyer (1908 - 1989), always known to one and all as "Jack" Colyer. Apologies for the abysmal quality of the attached image, but it’s the only one that I've so far been able to find. If anyone has a better image of Colyer, please share it!!

Littlehampton must have been quite small given the very low production figures for the Cloud model engines. For those interested, a full history of Colyer's involvement with the Cloud engines and a description of the engines that he produced under that trade-name will appear elsewhere on this website in due course.

Littlehampton must have been quite small given the very low production figures for the Cloud model engines. For those interested, a full history of Colyer's involvement with the Cloud engines and a description of the engines that he produced under that trade-name will appear elsewhere on this website in due course.

It may come as a surprise to some readers to learn that the Bournemouth area was a significant centre for modelling activity and related commercial ventures during the early post-WW2 period. In addition to Majesco (following the move), the long-established Hallam company of nearby Poole remained very active, having begun the commercial manufacture of model engines well prior to the onset of WW2. A detailed article about the Hallam range will appear elsewhere on this website in due course.

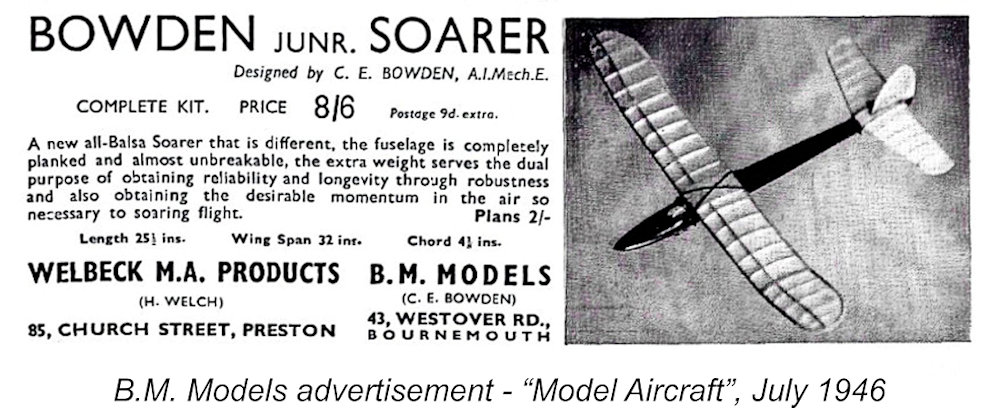

It may come as a surprise to some readers to learn that the Bournemouth area was a significant centre for modelling activity and related commercial ventures during the early post-WW2 period. In addition to Majesco (following the move), the long-established Hallam company of nearby Poole remained very active, having begun the commercial manufacture of model engines well prior to the onset of WW2. A detailed article about the Hallam range will appear elsewhere on this website in due course.  The strong post-war focus on model-related activity in the Bournemouth area probably had much to do with the fact that two of the most influential figures in post-war British aeromodelling were local residents - Phil Smith of Veron fame and the noted pioneering power modeller and author Col. C. E. Bowden. Phil Smith’s excellent Veron designs successfully introduced many individuals to the aeromodelling hobby, myself among them. Col. Bowden was indefatigable in promoting power modelling, publishing numerous books and articles on the subject in addition to sponsoring major competitions both in the Bournemouth area and elsewhere. He was also a participant in the model trade, advertising his model designs as of mid 1946 onward from an address at 43 Westover Road in Bournemouth under the trade-name B. M. Models.

The strong post-war focus on model-related activity in the Bournemouth area probably had much to do with the fact that two of the most influential figures in post-war British aeromodelling were local residents - Phil Smith of Veron fame and the noted pioneering power modeller and author Col. C. E. Bowden. Phil Smith’s excellent Veron designs successfully introduced many individuals to the aeromodelling hobby, myself among them. Col. Bowden was indefatigable in promoting power modelling, publishing numerous books and articles on the subject in addition to sponsoring major competitions both in the Bournemouth area and elsewhere. He was also a participant in the model trade, advertising his model designs as of mid 1946 onward from an address at 43 Westover Road in Bournemouth under the trade-name B. M. Models.  In his 1949 book “

In his 1949 book “ As far as the production equipment used in the manufacture of the engines is concerned, Colyer probably initiated Majesco production using the same equipment that had been used in the pre-war manufacture of the Cloud engines. It's likely that he added to this equipment during the course of the relocation to Parkstone.

As far as the production equipment used in the manufacture of the engines is concerned, Colyer probably initiated Majesco production using the same equipment that had been used in the pre-war manufacture of the Cloud engines. It's likely that he added to this equipment during the course of the relocation to Parkstone.

The wording of the attached advertisement from the July 1946 issue of “Model Aircraft” makes the previously-noted claim that the “45” had been under development for no less than 7 years! The advertisement also claimed that the prototype was still in use as of mid 1946 after seven years of service! If this was in fact the case, that prototype must have dated from 1939, prior to the onset of World War 2.

The wording of the attached advertisement from the July 1946 issue of “Model Aircraft” makes the previously-noted claim that the “45” had been under development for no less than 7 years! The advertisement also claimed that the prototype was still in use as of mid 1946 after seven years of service! If this was in fact the case, that prototype must have dated from 1939, prior to the onset of World War 2. The Majesco “45” was a more or less conventional design apart from its use of considerably over-square internal geometry, still a relatively uncommon feature at this time. Bore and stroke were 0.750 in (19.05 mm) and 0.625 in. (15.87 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 4.52 cc (0.276 cuin.). In his previously-mentioned book, Ron Warring reported that the engine weighed 6.25 ounces (177 gm) without the ancillary ignition support equipment. However, my own example acquired a few years after the original appearance of this article weighs in at 6.98 ounces (198 gm) with plug and tank but minus the ignition support system.

The Majesco “45” was a more or less conventional design apart from its use of considerably over-square internal geometry, still a relatively uncommon feature at this time. Bore and stroke were 0.750 in (19.05 mm) and 0.625 in. (15.87 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 4.52 cc (0.276 cuin.). In his previously-mentioned book, Ron Warring reported that the engine weighed 6.25 ounces (177 gm) without the ancillary ignition support equipment. However, my own example acquired a few years after the original appearance of this article weighs in at 6.98 ounces (198 gm) with plug and tank but minus the ignition support system. itself. An upper casting incorporating the location flange, cylinder barrel, cooling fins, exhaust port, bypass passage and cylinder head was attached to the upper crankcase flange with four screws. Somewhat unusually, these screws were inserted from below, as was the steel cylinder liner. In common with many other engines at this time, a

itself. An upper casting incorporating the location flange, cylinder barrel, cooling fins, exhaust port, bypass passage and cylinder head was attached to the upper crankcase flange with four screws. Somewhat unusually, these screws were inserted from below, as was the steel cylinder liner. In common with many other engines at this time, a  stack was another separate die-casting which was attached to the main cylinder block with a pair of screws.

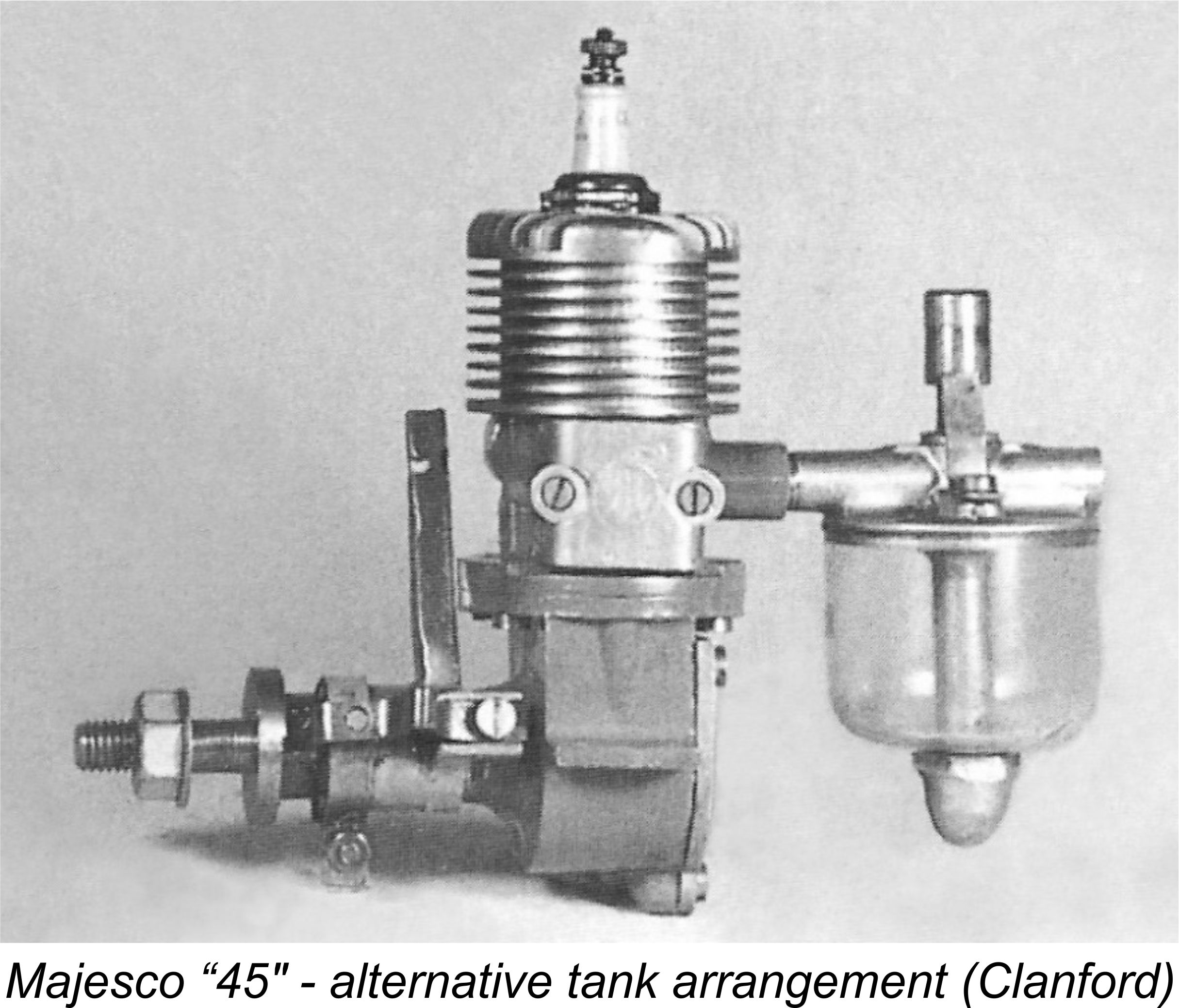

stack was another separate die-casting which was attached to the main cylinder block with a pair of screws. The fuel system was built around a cast venturi with integral tank top. A plastic hang tank was attached to this using the light alloy fuel pickup tube for support. Some examples used an acorn nut in conjunction with a clear plastic tank, while others featured a screw-on tank molded in red plastic. The latter tanks had the word “MAJESCO” formed in relief on their sides. The complete assembly simply screwed into a boss at the rear of the upper cylinder casting, being secured by a knurled brass locking ring. The needle valve was of the surface jet type then in very common use.

The fuel system was built around a cast venturi with integral tank top. A plastic hang tank was attached to this using the light alloy fuel pickup tube for support. Some examples used an acorn nut in conjunction with a clear plastic tank, while others featured a screw-on tank molded in red plastic. The latter tanks had the word “MAJESCO” formed in relief on their sides. The complete assembly simply screwed into a boss at the rear of the upper cylinder casting, being secured by a knurled brass locking ring. The needle valve was of the surface jet type then in very common use. instruction leaflet for the kit version of the engine, the manufacturers confined themselves to recommending props in the 10 inch - 12 inch diameter range, no pitch being specified. Claimed output was 0.200 BHP @ 7,500 rpm - probably not that far out of line with reality for a good example.

instruction leaflet for the kit version of the engine, the manufacturers confined themselves to recommending props in the 10 inch - 12 inch diameter range, no pitch being specified. Claimed output was 0.200 BHP @ 7,500 rpm - probably not that far out of line with reality for a good example.

The implication of all of this data is that the Majesco “45” remained in production for well over two years, during which time a considerable number may have been produced both in kit form and as complete engines. The fact that the engine’s selling price appears to have been maintained all along despite the emergence of less expensive alternatives from mid 1946 onwards suggests that it was highly regarded and hence in considerable demand despite its relatively high price.

The implication of all of this data is that the Majesco “45” remained in production for well over two years, during which time a considerable number may have been produced both in kit form and as complete engines. The fact that the engine’s selling price appears to have been maintained all along despite the emergence of less expensive alternatives from mid 1946 onwards suggests that it was highly regarded and hence in considerable demand despite its relatively high price. My factory-built example of the Majesco “45” (no. 576) has clearly been mounted and has seen some use. However, it remains in first-class mechanical condition, with excellent compression and minimal play in the bearings. In fact, I would objectively say that it’s still a little on the tight side. It is also in completely original configuration, including the tank. I ran all the usual checks on the timer, finding that it functioned perfectly. There seemed to be no reason why the engine should not perform up to its potential.

My factory-built example of the Majesco “45” (no. 576) has clearly been mounted and has seen some use. However, it remains in first-class mechanical condition, with excellent compression and minimal play in the bearings. In fact, I would objectively say that it’s still a little on the tight side. It is also in completely original configuration, including the tank. I ran all the usual checks on the timer, finding that it functioned perfectly. There seemed to be no reason why the engine should not perform up to its potential.

The Majesco "45" was not Jack Colyer's only venture into the world of model spark ignition engine design. In his previously cited 1949 book “

The Majesco "45" was not Jack Colyer's only venture into the world of model spark ignition engine design. In his previously cited 1949 book “ The result was the appearance of Majesco’s first diesel model, the Majesco “22” unit of 2.2 cc displacement. The new design seems to have made its debut in late 1946. This date is consistent with the fact that the Majesco range was not mentioned in the 1946-47 first edition of the pioneering book “

The result was the appearance of Majesco’s first diesel model, the Majesco “22” unit of 2.2 cc displacement. The new design seems to have made its debut in late 1946. This date is consistent with the fact that the Majesco range was not mentioned in the 1946-47 first edition of the pioneering book “ The Majesco "22" was mentioned frequently in the 1947 first edition of Col. Bowden’s book “

The Majesco "22" was mentioned frequently in the 1947 first edition of Col. Bowden’s book “

It appears that a fair number of examples of the “22” reached the market in this form during 1947. Certainly, by his own statements Col. C. E. Bowden had at least two of these variants - his examples appeared in many of the illustrations to be found in his 1947 book “

It appears that a fair number of examples of the “22” reached the market in this form during 1947. Certainly, by his own statements Col. C. E. Bowden had at least two of these variants - his examples appeared in many of the illustrations to be found in his 1947 book “ At some point quite early on in the production program, certainly during 1947, the design of this model was refined somewhat. The former all-steel cylinder with integral fins was replaced by an upper cylinder casting in light alloy with a steel liner, much like the configuration of the earlier “45” spark ignition model. However the porting arrangements for the diesel remained unaltered from those of the original version, with a single bypass located at the front and twin exhaust ports, one on each side. These exhaust ports were completed by a pair of stacks which were attached to the upper cylinder casting by two screws apiece. In other respects, the design appeared to be more or less unchanged.

At some point quite early on in the production program, certainly during 1947, the design of this model was refined somewhat. The former all-steel cylinder with integral fins was replaced by an upper cylinder casting in light alloy with a steel liner, much like the configuration of the earlier “45” spark ignition model. However the porting arrangements for the diesel remained unaltered from those of the original version, with a single bypass located at the front and twin exhaust ports, one on each side. These exhaust ports were completed by a pair of stacks which were attached to the upper cylinder casting by two screws apiece. In other respects, the design appeared to be more or less unchanged.

In common with the prototypes, the revised version of the “22” retained a tank assembly which incorporated a fuel cutout. This was of the spring-loaded plunger type, with a wire release clip to actuate the device. The difference was that the integrally-cast barrel of the cut-out was now oriented horizontally rather than vertically - the use of a spring rather than gravity to activate the device permitted this.

In common with the prototypes, the revised version of the “22” retained a tank assembly which incorporated a fuel cutout. This was of the spring-loaded plunger type, with a wire release clip to actuate the device. The difference was that the integrally-cast barrel of the cut-out was now oriented horizontally rather than vertically - the use of a spring rather than gravity to activate the device permitted this.  commented that this model suffered from overly-fragile mounting lugs but was otherwise a reliable general-purpose unit. It’s perfectly true that the mounting lugs appear somewhat on the fragile side, as does the rather skimpy unbraced main bearing housing. It must also be said that the screw-in carburettor assembly also looks pretty vulnerable -

commented that this model suffered from overly-fragile mounting lugs but was otherwise a reliable general-purpose unit. It’s perfectly true that the mounting lugs appear somewhat on the fragile side, as does the rather skimpy unbraced main bearing housing. It must also be said that the screw-in carburettor assembly also looks pretty vulnerable -  The Majesco “22” appears to have sold quite well in this form, remaining on sale for some time. Advertisements for the engine were placed in the December 1947 issue of "Aeromodeller" magazine by both Gamages and Super Model Aircraft Supplies. The engine was featured in Henry J. Nicholls’ February 1948 advertising placement in “Aeromodeller”, selling at that time for a rather uncompetitive figure of £5 12s 6d (£5.62). By comparison, the

The Majesco “22” appears to have sold quite well in this form, remaining on sale for some time. Advertisements for the engine were placed in the December 1947 issue of "Aeromodeller" magazine by both Gamages and Super Model Aircraft Supplies. The engine was featured in Henry J. Nicholls’ February 1948 advertising placement in “Aeromodeller”, selling at that time for a rather uncompetitive figure of £5 12s 6d (£5.62). By comparison, the  As mentioned previously, my early example bears the serial number 374, implying that at least that many were made in this form. The only three D-prefix serial numbers of my present acquaintance are Kevin Richards’ former example number D 707, my own engine number D 734 and engine number D 823 which appeared some time ago on eBay. This may be a very small sample, but if we assume that the sequence followed the usual Majesco pattern by starting at 1, the implication is that at least 823 examples were made in total. The true number may of course have been substantially greater than this. More serial numbers, please!

As mentioned previously, my early example bears the serial number 374, implying that at least that many were made in this form. The only three D-prefix serial numbers of my present acquaintance are Kevin Richards’ former example number D 707, my own engine number D 734 and engine number D 823 which appeared some time ago on eBay. This may be a very small sample, but if we assume that the sequence followed the usual Majesco pattern by starting at 1, the implication is that at least 823 examples were made in total. The true number may of course have been substantially greater than this. More serial numbers, please!

The Majesco “22” was never the subject of a published test during its relatively brief period of production. This being the case, it was down to me to put an example on the bench and attempt to form some kind of rational opinion regarding its performance and operating qualities.

The Majesco “22” was never the subject of a published test during its relatively brief period of production. This being the case, it was down to me to put an example on the bench and attempt to form some kind of rational opinion regarding its performance and operating qualities.  This example proved to be very easy to start, although it did have its own characteristics which took a little knowing. It seemed to be quite fussy regarding the amount of fuel in the cylinder - following a few choked flicks and a small port prime, it would absorb a series of starting flicks with absolutely no response. Then all of a sudden it would burst into life - no preliminary popping and banging at all! The engine was either running .....or it wasn't!

This example proved to be very easy to start, although it did have its own characteristics which took a little knowing. It seemed to be quite fussy regarding the amount of fuel in the cylinder - following a few choked flicks and a small port prime, it would absorb a series of starting flicks with absolutely no response. Then all of a sudden it would burst into life - no preliminary popping and banging at all! The engine was either running .....or it wasn't!  Response to the needle was excellent, greatly facilitating the establishment of the optimum setting for each prop tested. The engine's only handling vice was a tendency for the contra piston to freeze in the bore at full running temperature. However, this really wasn't much of a problem given the fact that the engine would start and run at the same compression setting once this had been established. It's probably an idiosyncracy of this particular example.

Response to the needle was excellent, greatly facilitating the establishment of the optimum setting for each prop tested. The engine's only handling vice was a tendency for the contra piston to freeze in the bore at full running temperature. However, this really wasn't much of a problem given the fact that the engine would start and run at the same compression setting once this had been established. It's probably an idiosyncracy of this particular example.

Moreover, the engine delivered its peak output at very moderate RPM. It was a torque producer rather than a powerhouse, being able to swing a prop of very useful size at moderate speeds. It was also very controllable through judicious use of the compression and mixture settings. All of this would have made life very comfortable for many contemporary power modellers. Factor in the excellent handling together with the high quality of construction, and it’s clear that Majesco had a very useable product here, at least by the standards which prevailed at the time of its introduction.

Moreover, the engine delivered its peak output at very moderate RPM. It was a torque producer rather than a powerhouse, being able to swing a prop of very useful size at moderate speeds. It was also very controllable through judicious use of the compression and mixture settings. All of this would have made life very comfortable for many contemporary power modellers. Factor in the excellent handling together with the high quality of construction, and it’s clear that Majesco had a very useable product here, at least by the standards which prevailed at the time of its introduction. Paradoxically, although very few examples were produced by comparison with the “45” and “22” models, perhaps the Majesco company’s best-remembered model among present-day model diesel enthusiasts seems to be the Majesco Mite, a cute little radially-mounted 0.735 cc diesel of highly unusual layout. Although in the past it has often been assigned an introductory date of 1948, the production of this little unit actually seems to have been confined to the year 1947.

Paradoxically, although very few examples were produced by comparison with the “45” and “22” models, perhaps the Majesco company’s best-remembered model among present-day model diesel enthusiasts seems to be the Majesco Mite, a cute little radially-mounted 0.735 cc diesel of highly unusual layout. Although in the past it has often been assigned an introductory date of 1948, the production of this little unit actually seems to have been confined to the year 1947.  both his own and Col. Bowden’s models, both powered by the Majesco Mite. In addition, many of the other illustrations feature the companion “22” diesel in its original pre-production or early production guise, although an image of the later production version was also included. It seems not unlikely that Col. Bowden acted as one of the official “factory testers” used by Colyer to evaluate and improve his products.

both his own and Col. Bowden’s models, both powered by the Majesco Mite. In addition, many of the other illustrations feature the companion “22” diesel in its original pre-production or early production guise, although an image of the later production version was also included. It seems not unlikely that Col. Bowden acted as one of the official “factory testers” used by Colyer to evaluate and improve his products.

It must be said that the location of the fuel system on the Mite was not the most convenient arrangement in many ways, particularly if cowling was involved. The engine was also quite unsuitable for control line use as supplied. In addition, it could only be used in an upright mounting configuration. These factors may well have contributed to the Mite’s seemingly very brief tenure in the marketplace.

It must be said that the location of the fuel system on the Mite was not the most convenient arrangement in many ways, particularly if cowling was involved. The engine was also quite unsuitable for control line use as supplied. In addition, it could only be used in an upright mounting configuration. These factors may well have contributed to the Mite’s seemingly very brief tenure in the marketplace. The Mites carried serial numbers which were stamped into the centre of the backplate casting at the rear. My own illustrated example (which I subsequently traded on) bore the serial number 14. I've since acquired an identical example bearing the number 2. The rarity of the engine is such that these are the only serial numbers of my present acquaintance. I’d love to hear of more ........

The Mites carried serial numbers which were stamped into the centre of the backplate casting at the rear. My own illustrated example (which I subsequently traded on) bore the serial number 14. I've since acquired an identical example bearing the number 2. The rarity of the engine is such that these are the only serial numbers of my present acquaintance. I’d love to hear of more ........ Setting aside the previously-noted design flaws, the quality of construction of the engine leaves little to be desired. I’d say that it was at least as well-made as the majority of its competitors, and better than many.

Setting aside the previously-noted design flaws, the quality of construction of the engine leaves little to be desired. I’d say that it was at least as well-made as the majority of its competitors, and better than many.

As of early 1947 when the Mite appears to have been manufactured, it had no direct competition in its immediate displacement category. Its closest competitor was the AMCO .87 Mk. I which appeared in August 1947. The

As of early 1947 when the Mite appears to have been manufactured, it had no direct competition in its immediate displacement category. Its closest competitor was the AMCO .87 Mk. I which appeared in August 1947. The  run one of these well-behaved and fine-running little beasts! No wonder they were so popular in their day - starting is an absolute breeze on a few choked flicks, as is finding the optimum settings thanks to the excellent response to both controls. The little Mk. I ran flawlessly and developed a lot more urge than you might expect from an engine of its rather “primitive” sideport design layout. The figures obtained suggested a peak output of somewhere in the neighborhood of 0.062 BHP @ 9,000 rpm - a very worthy performance for a 0.75 cc engine of 1948 vintage, and one which the Majesco would be pushed to beat.

run one of these well-behaved and fine-running little beasts! No wonder they were so popular in their day - starting is an absolute breeze on a few choked flicks, as is finding the optimum settings thanks to the excellent response to both controls. The little Mk. I ran flawlessly and developed a lot more urge than you might expect from an engine of its rather “primitive” sideport design layout. The figures obtained suggested a peak output of somewhere in the neighborhood of 0.062 BHP @ 9,000 rpm - a very worthy performance for a 0.75 cc engine of 1948 vintage, and one which the Majesco would be pushed to beat.