|

|

The Elfin 149 PB Replicas

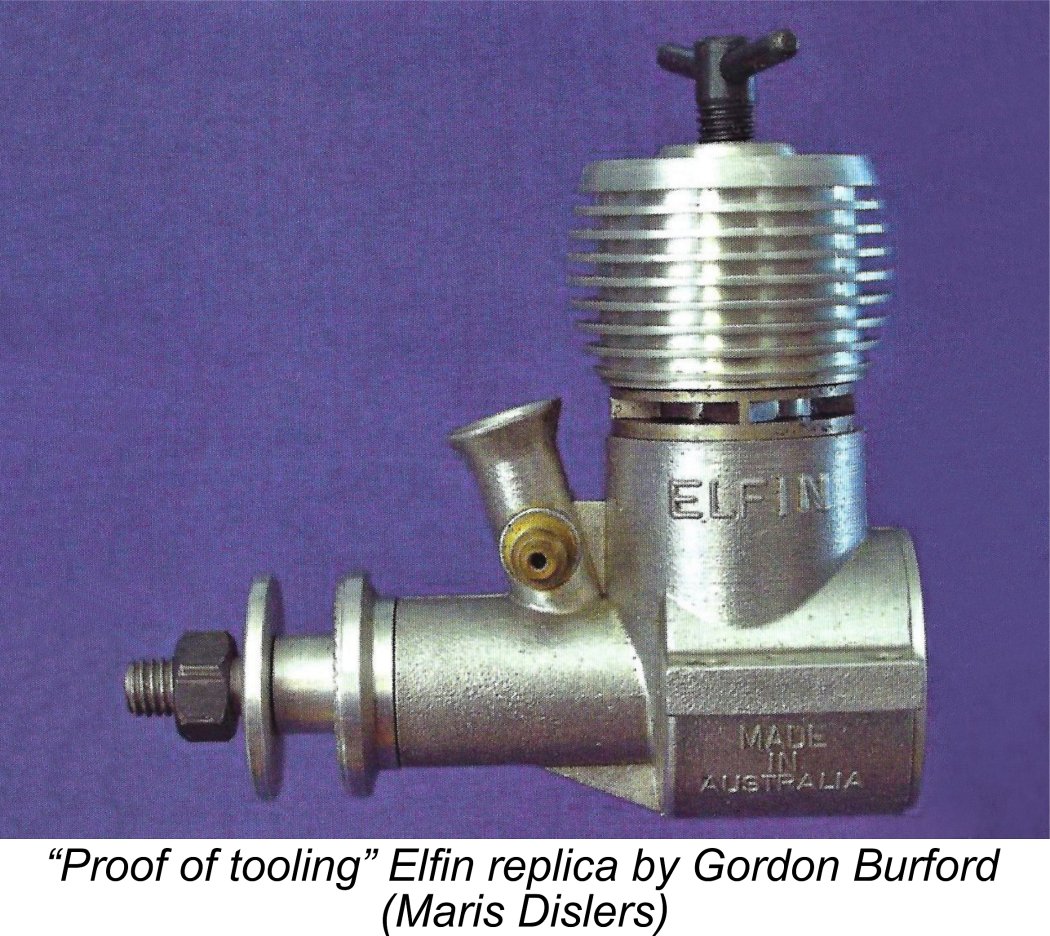

I may as well begin by acknowledging the fact that I would never have so much as embarked upon the writing of this article without the initial assistance and encouragement of my friend Chris Murphy of New Zealand. Prior to receiving some highly relevant first-hand information from Chris, I had absolutely no detailed knowledge about the Australian and New Zealand connections with this story. I’m greatly in Chris’s debt for his generous sharing of that information, which he first provided to me some years ago and subsequently expanded. Had he not done so, a few significant elements of the story would have been irretrievably lost. So much of the gathering and recording of model engine history is a race against time these days. It's great to have finally found the time to put Chris's information to good use. I must also acknowledge the additional help and encouragement which I received during the early stages of this research from the late and much-missed David Owen, who left us in March 2016. I will always regret the fact that my friend David was not spared to see this project through to completion with me. Some elements of this saga have already appeared in an article written by the late Ron Chernich which is still to be found on Ron's now-frozen but still accessible "Model Engine News" (MEN) website. I freely and gratefully acknowledge having drawn upon that article in piecing together this account. I'm also immensely indebted to Ilya Leydman of the Sydney-based Macheast company which was responsible for the actual production of the best-known of these replicas. Ilya was able to provide valuable details regarding their manufacture, including production figures. In addition, I wish to acknowledge the considerable assistance rendered to me by Tahn Stowe of Australia. As the son of one of the major players in this story, the legendary Ivor F, Tahn was in a unique position to keep me on track at certain points in the narrative. Tahn also provided me with the material from which I was able to assemble my own example of the rarest of all these replicas - the original "Made in Australia" Doonside Elfin. More of that below in its place ............... as if this wasn't enough, Tahn was the source of a genuine Ivor-certified Series II Doonside ABC replica which became available to me for examination and test, as reported below. Cooperation doesn't come any better than this! I'd also like to thank Steve Todd of Queensland, Australia for kindly sharing his recollections of his part in the creation of the original Doonside Elfins as well as his production of the far later Steve Todd Doonsides. Without Steve's input, this story wouldn't be complete - thanks, mate! Finally, thanks are due to my good mate Maris Dislers for drawing my attention to a number of issues of which I'd had no knowledge when I first published this article. Not only did he make me aware of a published test which I had overlooked, but he also provided information on an early Australian Elfin replica which had completely escaped my notice! He was also able to provide some extra detail regarding the development of the "original" Doonside Elfin replicas. I need friends like Maris to keep these articles authoritative! Before getting started on my narrative, I must acknowledge the fact that a considerable measure of controversy surrounds certain aspects of this story. Since the passage of over 30 years has taken many of the direct participants from our midst, I am unable to untangle these points of controversy myself. Accordingly, I will present both sides of the issues upon which there is disagreement, leaving my readers free to form their own opinions while making my own views clear where appropriate. With those acknowledgements having been recorded, it's time to get started. Here goes .............. Background

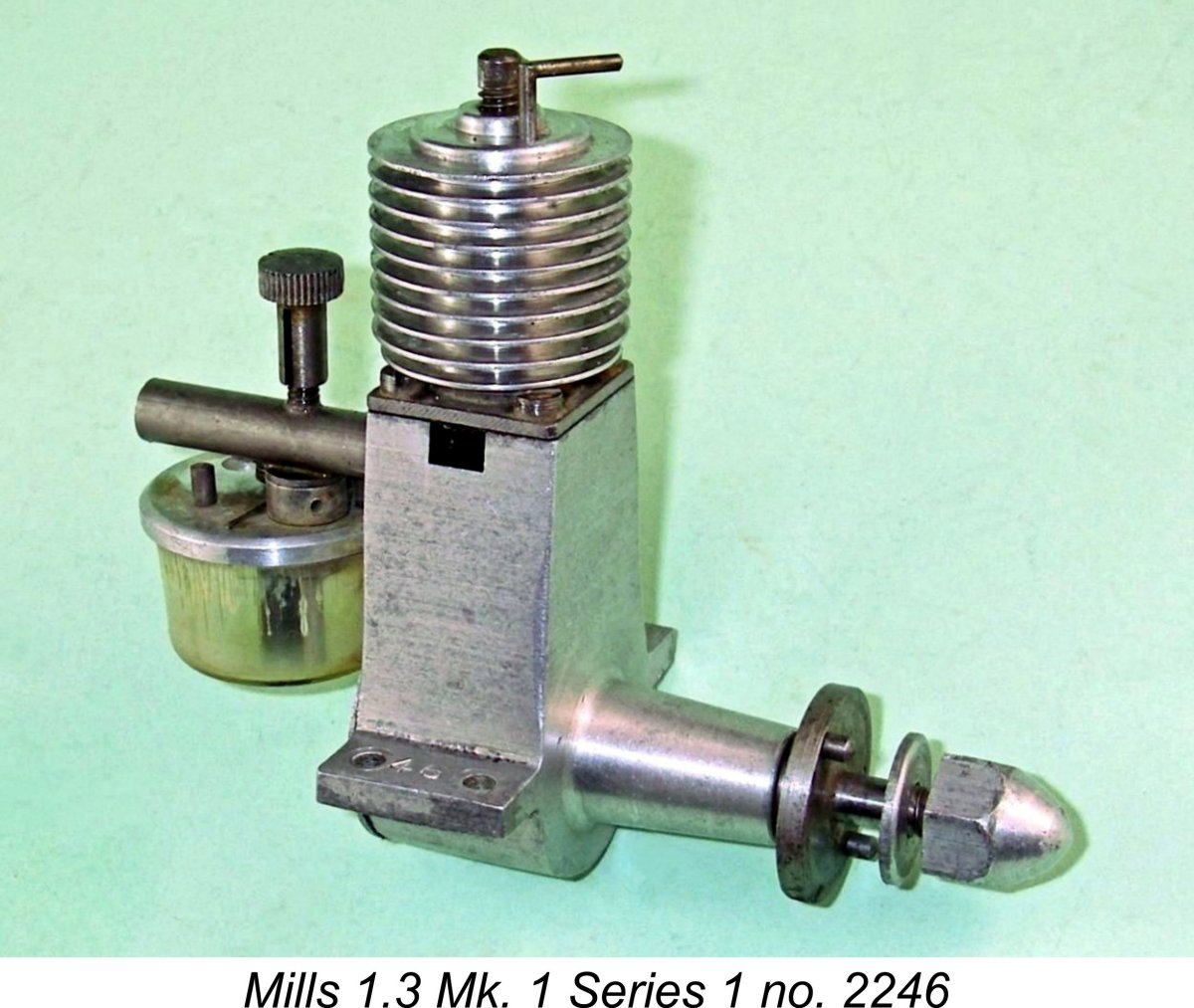

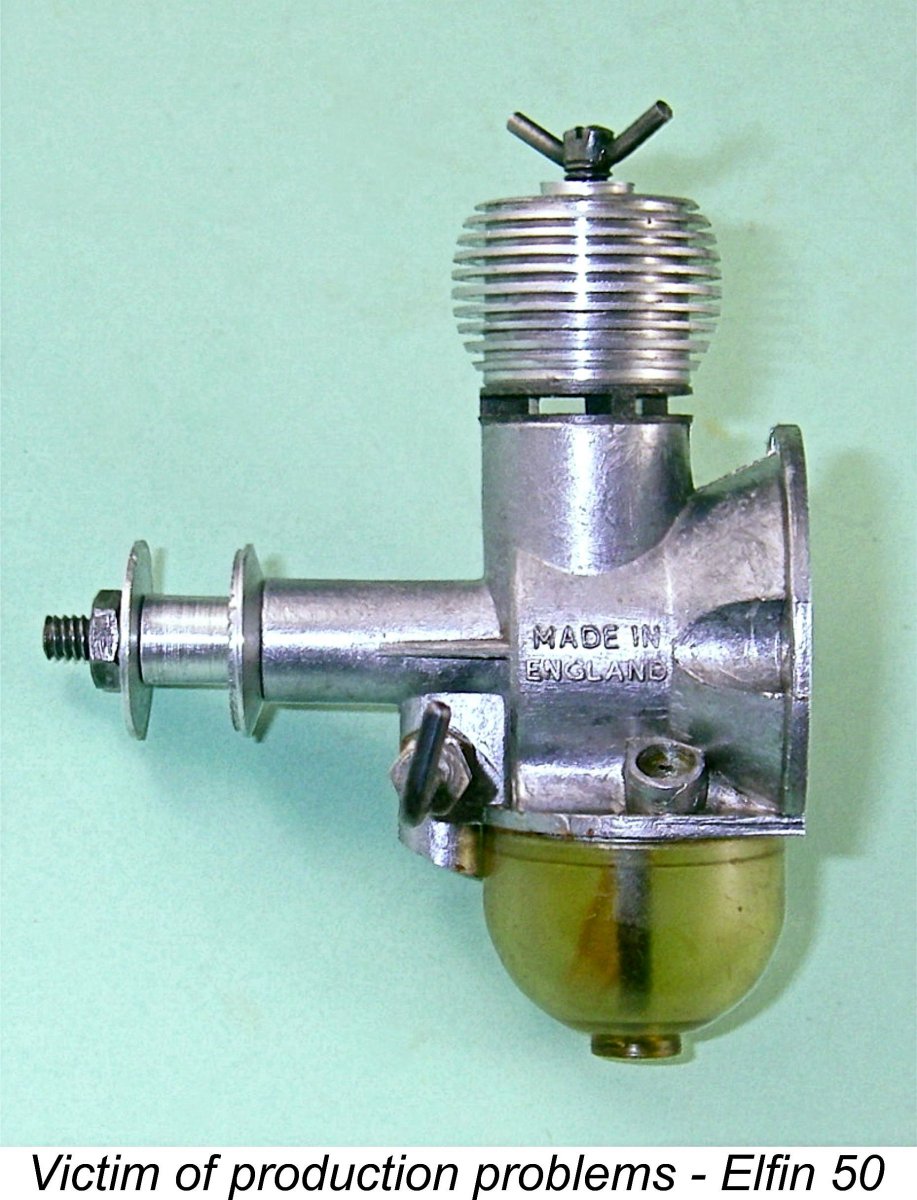

The Mills .75 and 1.3 diesels come immediately to mind as probably the most-replicated designs of them all. An article on the various Mills replicas from around the world may be found elsewhere on this website, along with a focused review of the CS “Mills” models made in Shanghai, China. An amazing variety of makers in many countries have produced replicas or close imitations of these iconic models. The range which almost certainly runs the Mills engines a close second in terms of replication is the Elfin series manufactured in Liverpool, England by Aerol Engineering between 1948 and 1957. Both the radial-mount and beam mount variants of the 2.5 cc Elfin 249 plain bearing (PB) model have been replicated by more than one manufacturer, while even the little Elfin 50 has received its share of attention from Arne Hende and others. I’ve written elsewhere about both the Dunham and Argo USA renditions of the radial-mount Elfin 249 PB model, and there were others such as those from CS.

Perhaps the engine’s most significant contest result came in 1952 when Barry Wheeler’s Elfin 149 PB-powered model was proxy-flown into first place at the World Free Flight Power Championship meeting held that year in Switzerland. A Swiss-made Fisher-Castor replica of the original radial mount Elfin 249 PB had won the inaugural contest in 1951, also finishing second in 1952 to Wheeler's Elfin 149-powered entry. In the control-line field, Alan Hewitt won both the European Stunt Championship and the Gold Trophy in 1951 using an Elfin 249 plain bearing powerplant, repeating his Gold Trophy win with the same engine in 1952. These results really underscored the performance capabilities of the plain bearing Elfin engines. There was further International success in 1954 when J. A. Gorham’s 149 PB equipped model was again proxy-flown to a very creditable fourth place in that year’s World Free Flight Power Championship. Both of these notable 1.5 cc free flight successes were achieved in the face of predominantly 2.5 cc opposition. These free flight accomplishments led for a time to a re-appraisal of the merits of 1.5 cc diesels as opposed to 2.5 cc units in Free Flight Power competitions. Perhaps the most notable effort along these lines came from the Russian free flight expert Vladimir I. Petukhov, who produced his extremely powerful 1.48 cc MK-15K and MK-16K prototype diesels between 1953 and 1955. His very impressive and far-reaching efforts are fully documented in a separate article to be found on this website. Immediately following its 1950 release, the Elfin 149 PB was the subject of two published tests which appeared back to back in the British modelling media. The first of these was Lawrence Sparey’s report which appeared in the June 1950 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. Sparey praised both the engine’s handling and performance very highly despite recording a somewhat disappointing peak output of 0.100 BHP @ 13,700 rpm. Even so, Sparey considered this to be a very acceptable performance by the standards of 1950. Peter Chinn’s test of the same model appeared a few months later in the August 1950 issue of the rival “Model Aircraft” magazine. Chinn was equally complimentary regarding the engine’s overall attributes. Moreover, he measured a significantly better performance than Sparey, reporting a peak output of 0.15 BHP @ 13,500 rpm – more or less the same peaking speed as Sparey, but clearly reflecting significantly greater torque development at that speed. Chinn rightly characterized this performance as “exceptional”, which it certainly was as of mid-1950.

Aerol Engineering founder and Elfin designer Frank Ellis had started the business in late 1946 using well-used WW2 surplus machine tooling which had given its best to the war effort before being sold off after the conflict at bargain prices, which were all that Frank could afford at the outset. Frank was subsequently unable to secure the financing necessary to upgrade this equipment, which naturally became progressively even more worn as time went on. Understandably, this had a very negative effect upon production consistency. The issue actually forced the cancellation of the very promising Elfin 50 project, as related elsewhere, ultimately leading to the termination of all Elfin production in early 1957. Despite this inconsistency, a good Elfin 149 PB was widely viewed as the best of the British 1.5 cc/.09 cuin. plain bearing diesels of the mid 1950’s. Following the termination of production in early 1957, the engine remained a popular item on the second-hand market. During my own formative years as a power modeller in Britain during the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, I recall frequently encountering both the 149 and 249 Elfin PB models still in regular use. They were no longer competitive in contest terms by that time, but for general purpose sport flying they continued to be highly regarded. Consequently, many of them received a lot of use, often being run into the ground (sometimes literally!) and subsequently discarded in those pre-collector days when “second-hand engines” were two a penny. The inevitable result as time went on was a steady decline in the number of good examples still in circulation and use. However, the first Elfin replicating effort in Australia came long before that situation developed. I'll begin at the beginning by taking a look at that initiative in the next section of this aticle. The First Aussie Replica - the Comet 150 The first Australian attempt to create an Elfin replica came way back in the early 1950's when the original Elfin 149 and 249 beam mount plain bearing models were still very much in production in their native England. This effort was motivated not by any thoughts of creating such a replica to satisfy collector or vintage flier demand - after all, the original Elfin 149 was then in production and available if one could source an example and was prepared to pay for it! Rather, this initiative represented an attempt to fill a supply-side shortfall in the Australian model engine market as it then existed. During the early post-WW2 period, model engines were in short supply in Australia. The importation of engines from overseas was made both difficult and costly by a combination of government-imposed restrictions on both overseas currency exchange and foreign imports. Accordingly, the relatively few engines that were available tended to be very expensive by the standards of the day.

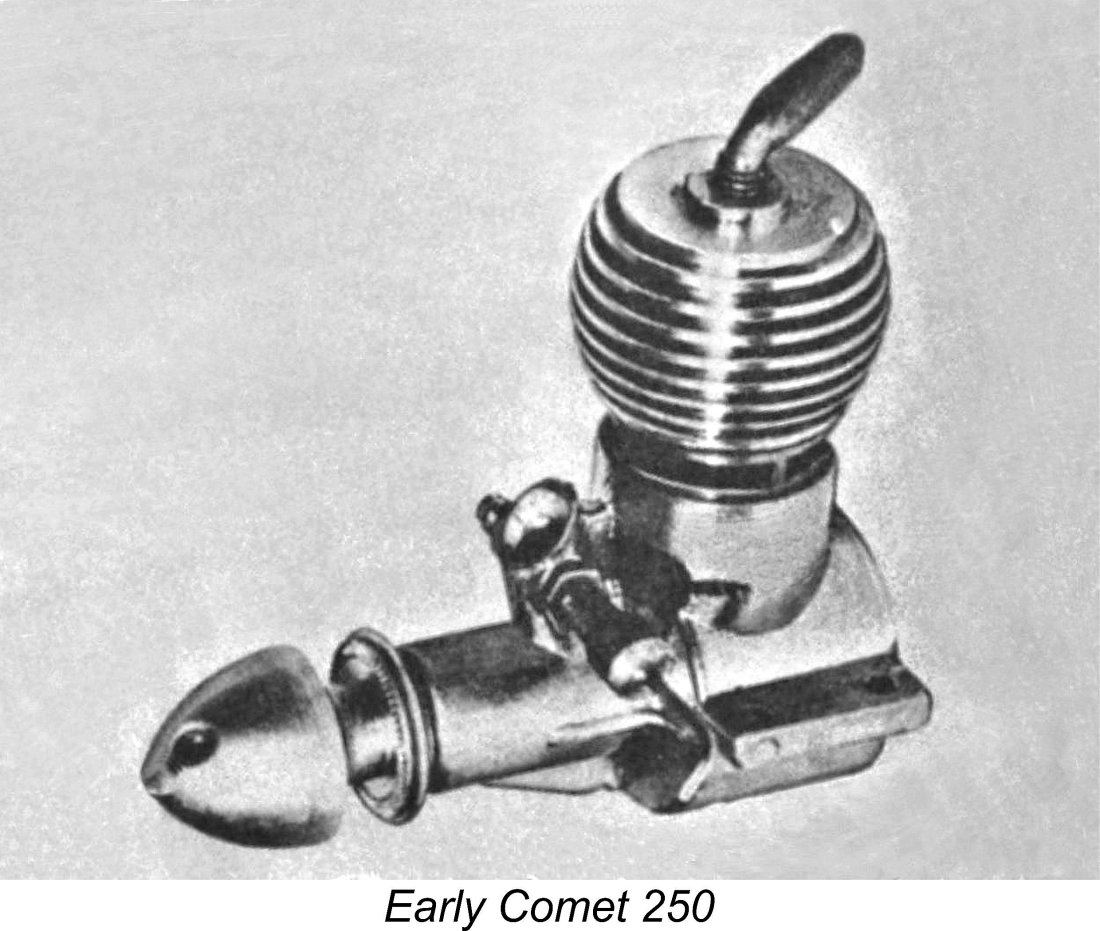

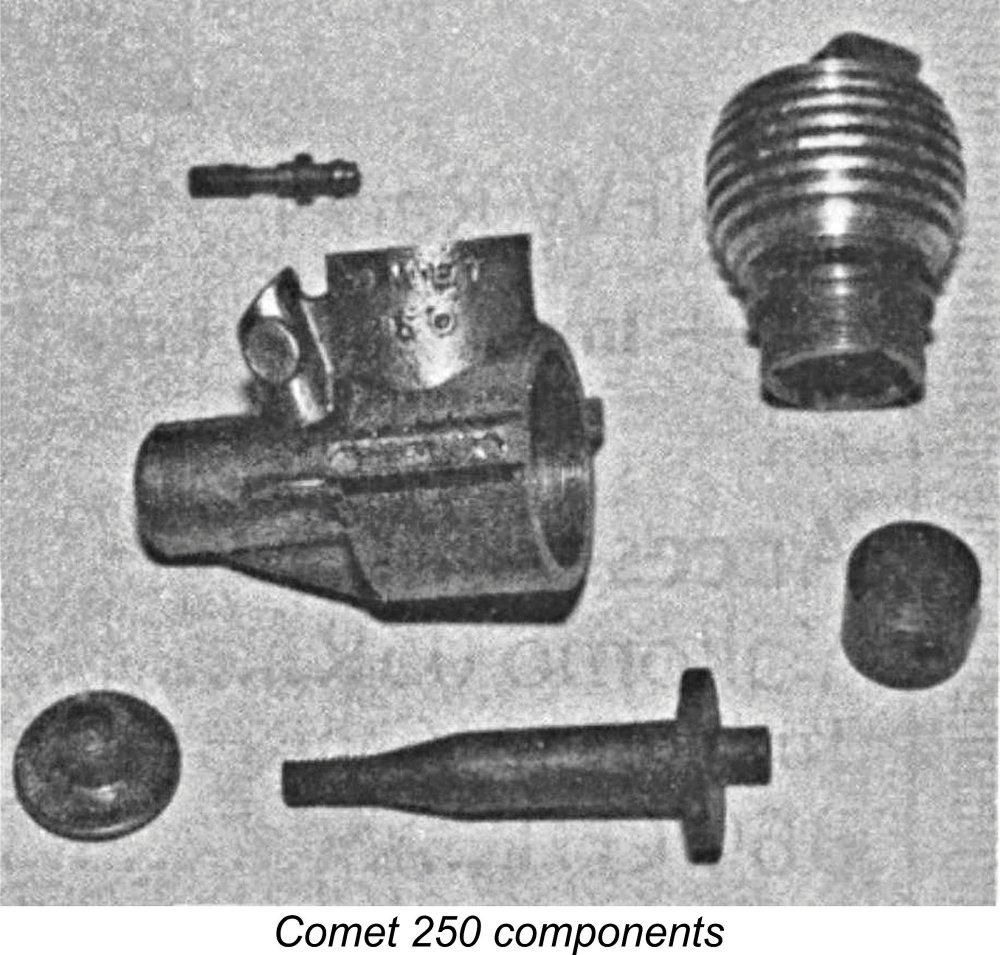

James Small was clearly interested in this proposal. In the interests of minimising development time, it made complete sense to imitate rather than innovate. The company chose the plain bearing Elfin 1.5 cc and 2.5 cc models of 1950 to serve as their design templates. A few examples of these engines had made it down to Australia by that time, hence being available to copy. As previously stated, the production of these models was not in any way motivated by collector or nostalgia-driven market pressures, since these didn't exist at the time. The motivation was purely to address a supply-side shortfall of available model engines that then existed in Australia. The fact that the resulting units were near-replicas was purely incidental, arising solely from an understandable desire to minimise development time by copying a successful existing design. This differentiates the Comets from later Elfin replicas, which were specifically intended to be replicas of an original. The model that was evidently produced in the greatest numbers was the 2.5 cc Comet 250, which was a close copy of the beam mount Elfin 249 PB model of 1950. At least 500 and possibly as many as 1000 examples of this model were reportedly made, a few of which survive today. These surviving examples confirm that the engines were very well made.

The Comet engines were very close copies of the 1950 Elfin beam mount originals apart from using gravity die-cast cases rather than pressure die-cast. The early examples of the Comet 250 such as that illustrated above carried no identification, while later examples had the Comet name and 250 displacement cast in relief onto the case, as seen in the accompanying component image. Whether or not the 150 was similarly identified is not known. According to the recollections of former James Small employee Peter Ellis which were published in “Airborne” magazine, a good example of the Comet 250 actually outperformed the original Elfin 249 PB. Presumably the 150 would have performed just as well. However, Peter didn't mention that model in his article.

It’s actually unlikely that production of the Comet engines continued past 1953. The Comet 250 apparently sold in the £7 to £10 range, a week’s wages for many Australians at the time, while a Sabre 250 sold at the time for just under 5 quid. No contest .......... the FROG 150 which was then becoming available in Australia would almost certainly have undercut the Comet 150. Against such competition, the Comet engines stood no chance in the marketplace. Still, a very worthy first Aussie attempt to replicate the Elfin plain bearing models! The "Real" Replica Era Begins By the time that the early 1970’s were reached, the first stirrings of widespread interest in both collecting and flying vintage and classic model engines had begun to influence the marketplace. The Elfin 149 PB was still fondly remembered, hence being seen as a highly desirable engine to acquire either for use in retro flying or simply as a collectible in its own right. The 249 models were viewed in a very similar light.

Australia took a leading role in jump-starting the replica movement with the 1974 release of the Doonside Mills engines which were manufactured by Gordon Burford at the instigation of the legendary and highly original Australian model enthusiast Ivor F (his full legal name - 2001 ABC Eccentric of the Year!). By the mid 1980's, the replica concept was in full implementation in Australia and elsewhere for a wide variety of classic model engines which were seen as particularly desirable. Gordon Burford went on to produce other replicas, including his fine Deezil, C.I.E. and Elfin 249 units. In Britain, Dunham Engineering based their entire model engine business portfolio on the production of replicas and retros, as detailed elsewhere. The Ivor F Elfin 149 Doonside Replicas

The projected market for this replica was the relatively numerous combined community of Australian and New Zealand vintage fliers, general sports users and collectors. It must be borne in mind that at the time the only 1.5 cc diesels generally available new anywhere would have been the P.A.W. 149 and the excellent Russian MK-17, which was a development of Vladimir Petukhov's previously-mentioned MK-16. A good quality replica of the light and powerful Elfin 149 PB would be a very welcome addition. According to Ivor's surviving diary, a few handwritten pages of which remain in the possession of his son Tahn, the production of some 1000 examples of this engine was envisaged at the outset. They were to be marketed using Ivor's Doonside trade-name which had been applied earlier to the aforementioned Mills .75 replicas produced in the 1970's by Gordon Burford at Ivor's instigation.

Having been in direct contact with Ivor and his associates during the relevant period, Chris Murphy retains some very clear personal recollections of this project which he has kindly shared with us. The usual approach of concentrating the manufacture of the engines at a single production facility was not pursued - instead, production of individual components was farmed out to a handful of widely-scattered individuals, each of whom agreed to make one or more specific components to Ivor's specifications. Once completed, these components were to be sent to Ivor for assembly into complete engines. Chris tells us that a number of Australian modelling luminaries became involved, making different parts for the engines. The investment castings for the crankcases were produced by Gordon Burford, while Gordon's son Peter Burford made the crankshafts. Ivor's son Tahn Stowe tells us that Ivor himself made the needle valve assemblies and most of the turned alloy components, on which he did a very good job. Based upon Steve Todd's recollections, it appears likely that Ivor also roughed out the piston/cylinder sets using equipment from the earlier Sesqui operation which he brought out of mothballs with Gordon Burford's assistance. However, it's probable that one Ted Hocking (a skilled machinist who was also a CAD/CAM expert) did the final finishing on those components. By the time that they reached Steve, they did so as complete assemblies.

The production of different components by individuals who are remotely located from each other inevitably invokes a high potential for incompatibilities between those components unless a very high level of coordination is maintained along with absolute adherence to extremely precise specifications and production standards. Sadly, in this case the level of coordination between participants fell short of what was required, the result being that although they were all beautifully made, many of the parts wouldn't fit together. A common problem at the outset arose from Ivor's inability to cut the female cylinder and backplate installation threads in the crankcase to the required standards of fit and finish. According to his own notes, Ivor eventually got around this by reducing the speed of the turret lathe on which these threads were cut as well as changing to a different machining lubricant. However, many cases were compromised before this fix was implemented. A further problem related to the main bearings - some of the main bearing housings were bored off centre, while others tended to split when the bushing was pressed in. As if this wasn't enough, many of the intakes broke during the boring process. Although it's probable that many of these issues were down to his own approaches, Ivor evidently blamed the casting alloy, prompting Gordon Burford to walk away from the project. While it's possible that the alloy used may not have been ideal, individuals other than Ivor (including Gordon) did manage to complete the machining of some of these cases successfully, proving that the case material was quite useable with care. Both Steve Todd and Stan Pilgrim pitched in to help Ivor out, with Steve completing some 30 engines, 5 of which he kept as payment, while Stan reportedly completed a further 10 or a dozen units. Ivor was thus able to number some 35-40 engines, most of which were sent to people to whom Ivor was indebted for collectible engines already received. Now that Gordon Burford had withdrawn from the project, Ivor had to look elsewhere to replace the cases which had been damaged through his earlier failed efforts. He apparently hoped that a switch to a permanent mold might produce castings which were better able to resist machining and installation stresses. To that end, his notes indicate that he paid $1000 to the aforementioned Ted Hocking to produce such a mold for the engine. It's unclear how many crankcases were produced from the resulting permanent molds, but some undoubtedly were. Maris Dislers recalls seeing a number of cases having a noticeably rougher finish than those produced by Gordon Burford. Tahn Stowe believes that these castings were produced from Ted Hocking's permanent mold. He recalled the early struggles to get good quality castings from this mold - the initial efforts apparently looked like early Taipan or English Elfin castings as opposed to the very clean investment castings that Gordon had produced. Ted was apparently sure that he could do better, but it's unclear how far he went in this direction. Unfortunately, Ted has dropped off the radar in recent years, so we can't ask him. Steve Todd was able to shed a little more light on Ted Hocking's involvement. It seems that Ted produced two different Elfin cases. The first had no name or displacement on it. The die was subsequently modified to show the Elfin designation on one side and the 149 displacement indication on the other side. Steve doesn't know how many of these castings were produced, but he ended up with dozens of both styles, many of which he has given to fellow modellers. To the best of Steve's knowledge, no engines were ever manufactured back in the day using these cases. Steve also believes that Ted made a die for the Mills .75 replica. He still has a crankcase casting that was given to him by Ivor at the same time as the Elfin cases.

Despite a waiting list of several hundred individuals who had committed in advance to purchase, Ivor's son Tahn Stowe believed that perhaps only some 35-40 examples were completed by Ivor and others during the late 1980's. A few more were subsequently assembled from residual components, but the total number in existence today almost certainly falls well below three figures. Thanks to the kindness of Tahn Stowe, I was granted the opportunity to tackle the assembly of such an engine myself. Tahn sent me a collection of residual components which included enough material to assemble at least one complete engine apart from the spraybar and prop mounting hardware, which I made myself. There were actually enough key components left over to serve as the basis for making a second example, albeit involving a great deal more work. Assessing these components prior to starting work on them enabled me to examine the engine very closely. A few departures from the original design were readily apparent. The prop driver was very different, being both longer and having a larger diameter. The intake venturi bore was increased from 0.187 in. to 0.209 in., presumably to allow the use of a spraybar having a larger working diameter. The spraybar was threaded M3.5x0.6 instead of the original Elfin's 4 BA component, which is waisted across its working length to reduce its effective diameter. The induction port in the crankshaft was elongated fore and aft with a forward angle, clearly to improve the efficiency of the rotary valve. Instead of the integrally-formed threaded extension at the front of the shaft to mount the prop, the replica used a tapped hole in the shaft which accommodated a separate steel stud or prop bolt. The thread used was M4x0.7 as opposed to the original Elfin's 1 BA.

While I agree that any replica should differ from the original sufficiently to prevent any possibility of its being passed off as the real thing, I firmly believe that mounting hole spacing is one detail that replicators should match faithfully. It's great to be able to use an original for special occasions or display purposes and then switch to a replica for rough and tumble flying (or vice versa in cases such as this where the replica is far more exclusive than the original!). As it is, you have to use adaptor plates to switch engines in the same model. I honestly wish that more replicators would get this right! Setting that issue aside, the accompanying images will confirm that these original all-Australian Doonside Elfins are very convincing replicas of the original. All components are beautifully made - it was just a matter of fettling them to get them to fit. The main assembly issue that I encountered with the components supplied to me by Tahn The unit which I was eventually able to complete ended up as a superb and fully representative example of its type. It weighed a checked 82 gm (2.89 ounces), a fraction more than the original Elfin's average 78 gm (2.75 ounces). Still, a very reasonable weight for a 1.5 cc diesel of the expected performance. There's zero possibility of mistaking one of these original Doonside Elfin 149 replicas for an original. Quite apart from the detail differences described earlier, the kicker is the fact that the inscription "Made in Australia" is cast in bold relief onto the underside of the crankcase in place of the Aerol original's "Made in England". In any event, the original Doonside replicas are actually far more exclusive and hence desirable collectibles than the originals, so why would anyone want to pass one off as an Aerol original, even if that was possible?!?

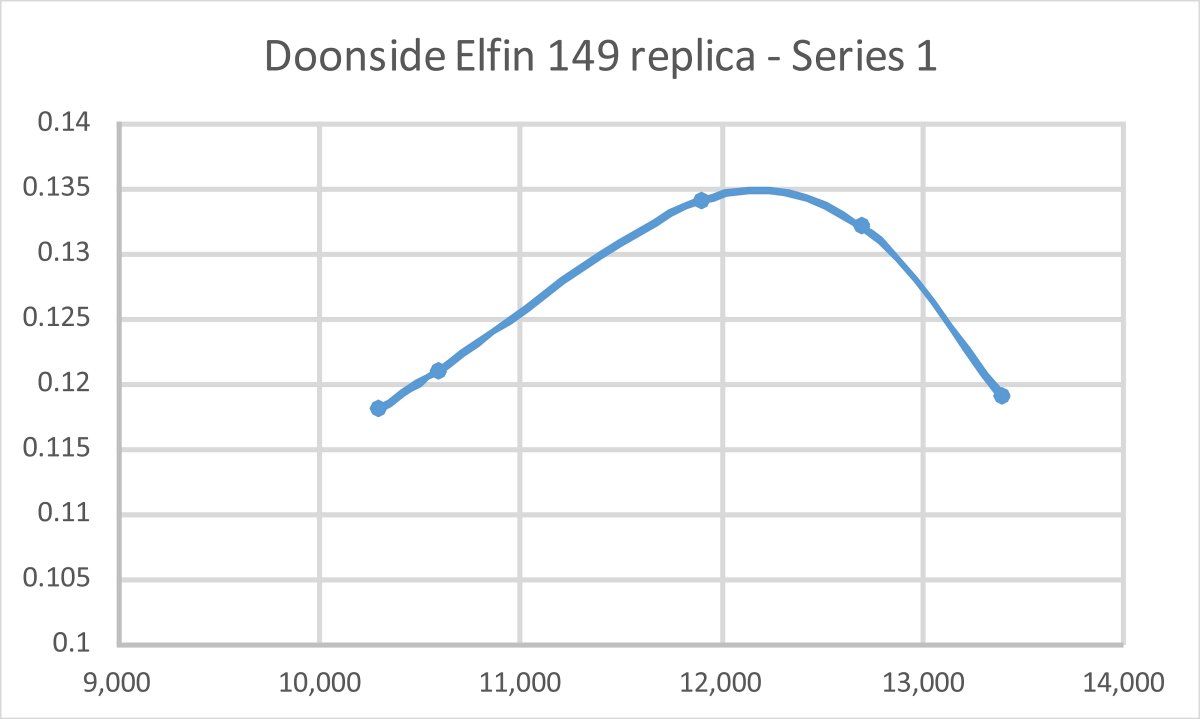

On the test bench, the previously unrun engine proved to be just as sticky as anticipated, making the initial start somewhat more challenging than it might have been. The engine actually had difficulty carrying over from the first firing stroke to the next. Chris Murphy reported that his previously-mentioned example of the same engine was tight to the point that although Ivor had managed to get it started immediately following its assembly in Chris's presence, it required a little subsequent fettling by Harvey Westland to get it fully sorted. It seems that initial tightness was a characteristic of these units. In the case of my example, it took a while for a start to be achieved following a switch to a 9x4 prop for a little more flywheel plus a few fairly generous port primes and a healthy stretch of arm exercise accompanied by some invective (to which the engine initially seemed impervious)! However, it decided to co-operate eventually. Things improved quickly once the engine was finally running - it proved to be very responsive to the controls, both of which held their settings perfectly while remaining fully adjustable at all times. Once the engine had an initial five-minute run on the 9x4 under its belt, with the usual 30-second lean-out at the end and subsequent complete cool-down to begin subjecting the piston to the required full-range heat cycles, subsequent starts on the 8x4 prop originally fitted proved to be relatively trouble-free despite some residual tightness in the piston/cylinder assembly. The engine continued to like a small prime for cold starting, but hot re-starts required only one or two choked flicks as a perliminary. Running when leaned out at the end of each run was commendably smooth and mis-free. Following a further half-dozen or more 5-minute break-in runs, during which the piston/cylinder fit improved noticeably, the engine seemed to be all ready to yield some meaningful test figures. A little additional running-in would almost certainly result in a further performance improvement, but I didn't feel like burning the extra fuel or subjecting the neighbours to a great deal more noise (the Covid situation then prevailing confined me to testing at home). I therefore began to take readings for a series of calibrated test airscrews, continuing to warm the engine up on reduced compression and a slightly rich mixture on each successive prop, leaning out only long enough to get a steady maximum-speed reading in each case and then allowing complete cooling prior to the next prop test. The engine thus continued to experience the full-range heat cycles which are probably the most important element of any break-in of an iron-and-steel engine. The all-Aussie Doonside showed itself to be a good performer, albeit delivering what I would consider to be a slightly below-average output for an Elfin 149 PB. That having been said, it remains true that this example was still a bit on the stiff side when tested. I would expect a measurable improvement in performance with some more running. The following data were obtained on test.

These numbers suggest a peak output in the region of 0.135 BHP @ 12,200 rpm for the engine as it stands. The low peaking speed certainly suggests that there's more It's clear from the findings of the above review that the failure of the original Australian Doonside Elfins to appear in the envisioned numbers was a great pity. It's definitely the best-made Elfin 149 that I've ever experienced, originals included. In hindsight, it's obvious that this engine set the quality standard to which all other Elfin 149 PB replicas would have to aspire. However, given the very small number of completed motors (certainly considerably less than 100 units), one's chances of finding an example today are pretty slim. I only have my tested example thanks to the kindness of my good mate Tahn Stowe. This being the case, it's time now to turn our attention to a later replica which appeared in far greater numbers and which is therefore significantly more likely to be encountered by any enthusiast. The Second Generation Doonside Elfins As the 1990's rolled around and the all-Australian Doonside Elfin 149 replicas continued to present insurmountable assembly challenges, the project had stalled with an accumulated deficit of some AU$80,000 or more and little hope of recovery. Back in 1990, this was a chunk of change! At this point, Ivor finally abandoned any idea of completing the project and began looking around for alternatives. An event which factored into Ivor’s thinking was the 1989 collapse of the Soviet Union and the consequent end of the hard-line Iron Curtain era. This seminal event had re-opened direct lines of communication with Russian manufacturers of model engines and other products. Taking note of this, in 1992 Ivor entered into negotiations with Ilya Leydman, then a Sydney resident (now living in Canberra) with strong Russian connections. Through his Sydney-based Macheast company, Ilya marketed his own line of Russian-made Zeus engines as well as a number of other Russian motors such as MDS glows, MK-17 diesels, Kometa glow and diesel models, MARZ 2.5 diesels and glows, etc. This was facilitated by the fact that Ilya retained some close contacts within Russia, actually owning a workshop located in Moscow. The following account is the subject of some controversy among the various participants, a number of whom have shared differing summaries of what transpired. Sadly, many of those from whom these accounts originated are now deceased. This being the case, I can only present the story in the form suggested by the majority of latter-day recollections to which I've been made privy along with the comments of participants who are no longer with us (including some surviving pages from Ivor F's diary). I am not taking sides in this matter - merely presenting a story which best represents the course of events as it has been brought to my attention by others. I will share my personal opinions at certain points but will play fair by openly presenting the opposing points of view. Readers are thus free to form their own opinions. The outcome of Ivor F's discussions with Ilya Leydman was a hand-shake agreement that Ilya and his colleagues would supply 1,500 engines, 1,000 of which were to be Elfin 149 replicas and the balance Mills .75 replicas (which have been discussed elsewhere in a separate article). It was Ivor's hope that these engines could theoretically be sold relatively quickly as "second generation Doonsides" to recover part of the outstanding costs stemming from the stillborn Australian Doonside Elfin 149 project. Prudently as things turned out, Ivor stipulated that he would personally inspect each and every engine before finally accepting delivery of those units that passed his inspection, thus fulfilling the necessary Quality Assurance (QA) function.

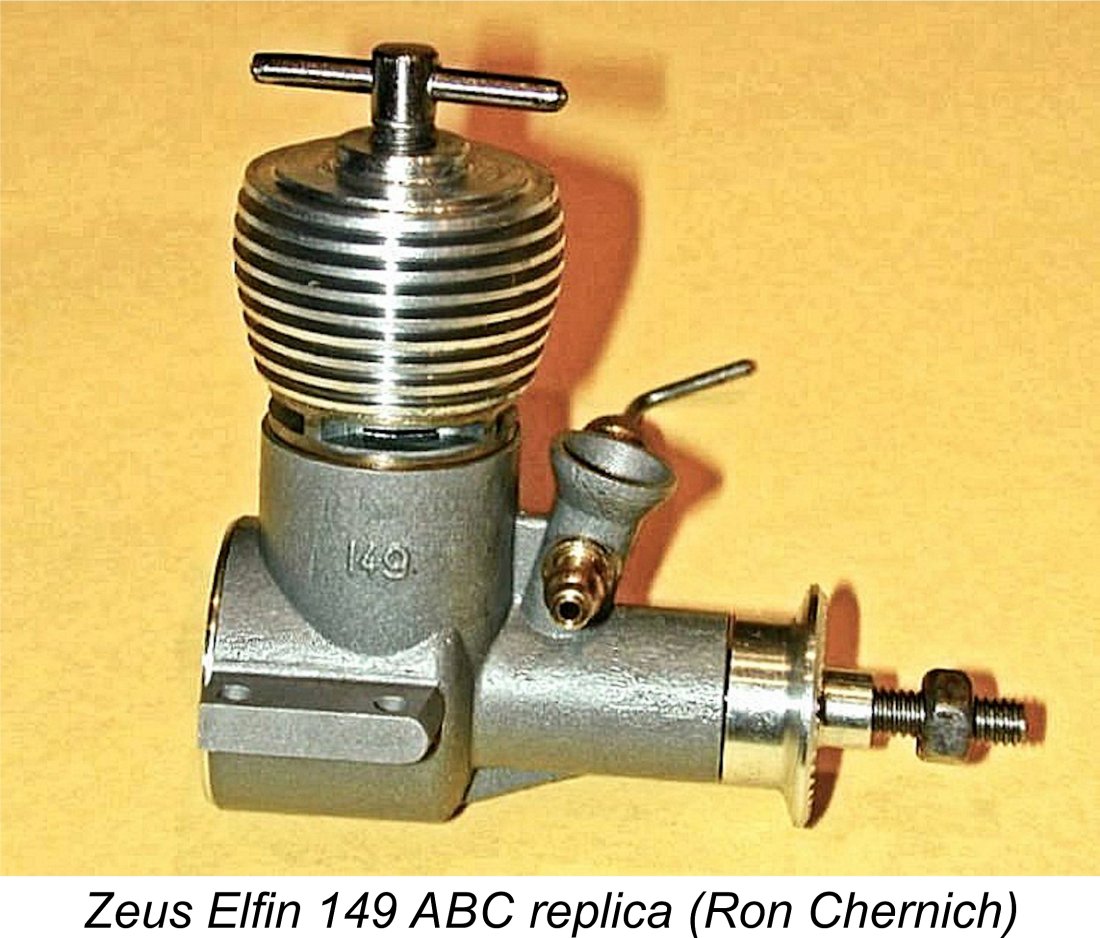

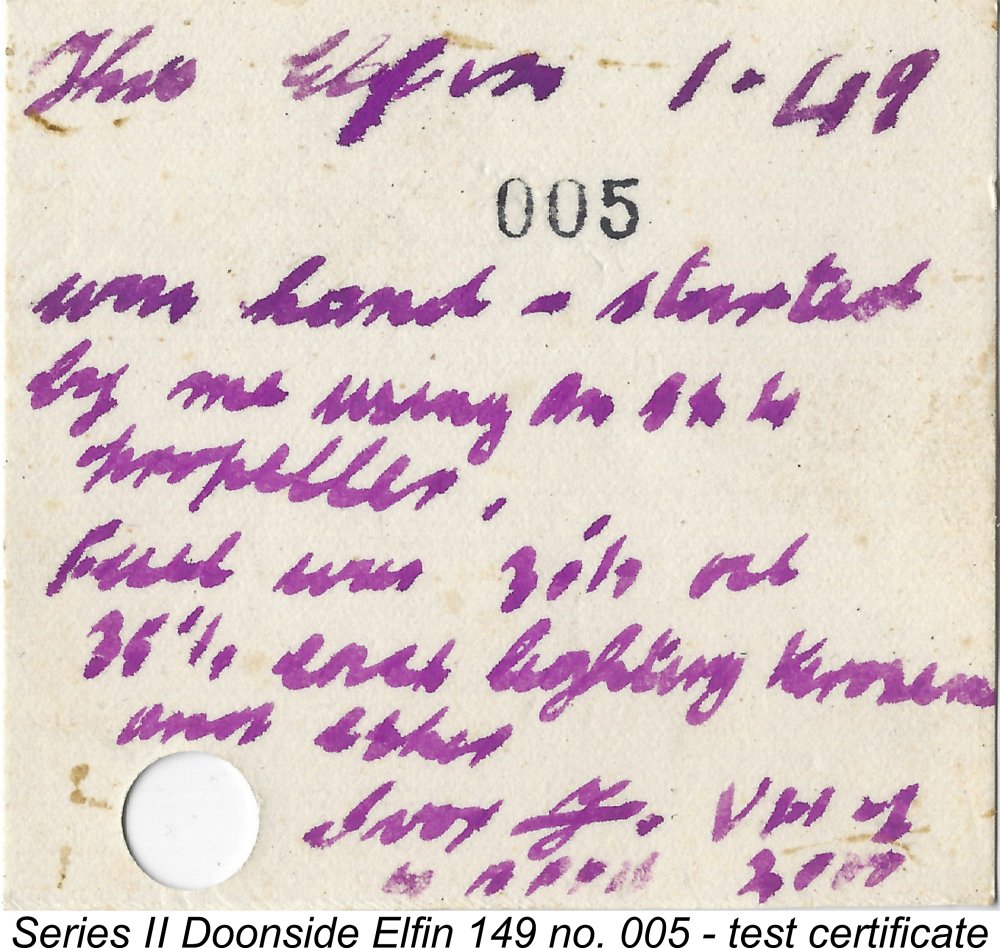

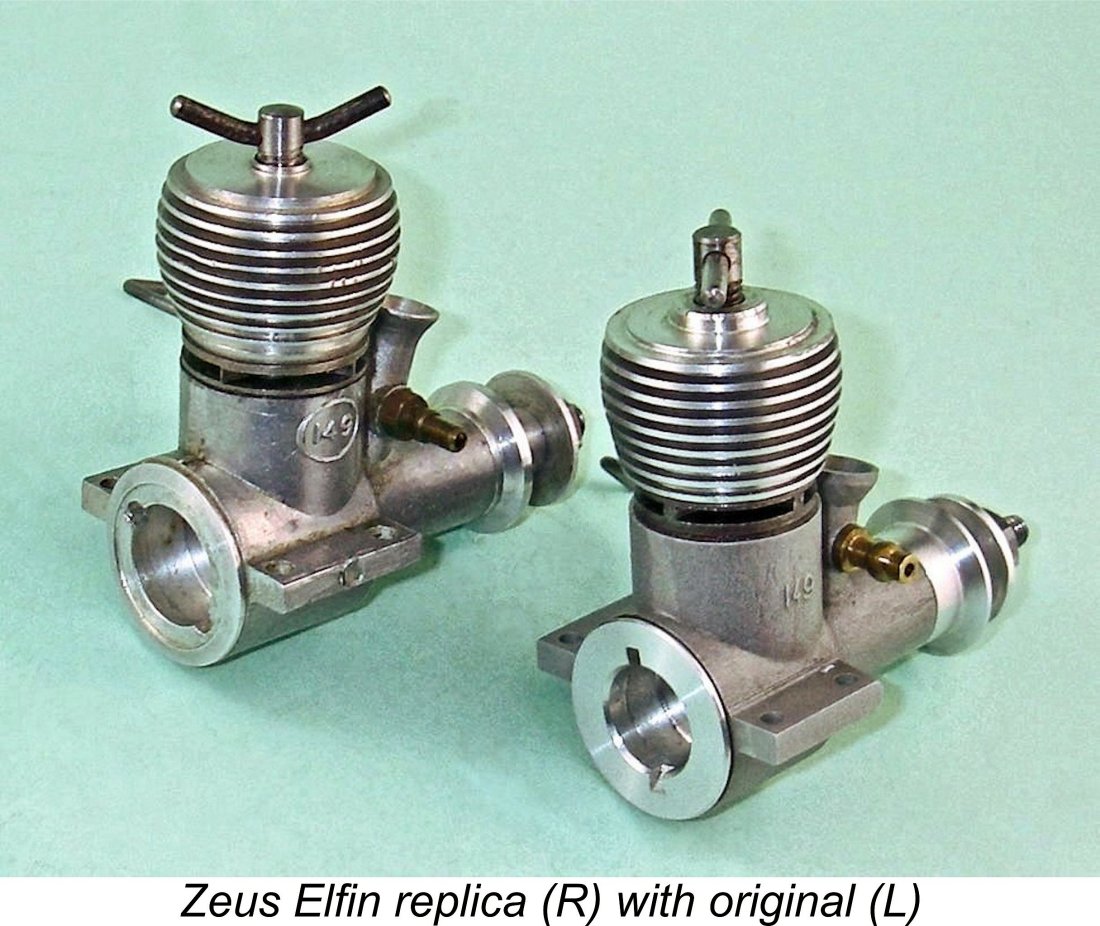

The crankshafts and iron-and-steel piston/cylinder sets were produced by a sub-contractor in the USA, while crankcases, needle valve assemblies and ABC piston/cylinder sets were made in Moscow. The machined aluminium components were produced in Australia by Macheast, who also assembled the engines. Accordingly, the term "Russian replica" which has been applied at times to these engines is inappropriate and should be avoided - they are properly referred to as "Zeus replicas", an identification reinforced by the appearance of the letter Z stamped on the crankcases. Mention of the ABC piston/cylinder sets brings us to the first of several seemingly unresolvable bones of contention. When deliveries commenced, a significant number of both the Elfin and Mills replicas were found to feature ABC piston/cylinder set-ups. According to Ivor and his direct associates, such a feature had not been specified - rather, the engines were all supposed to be iron-and-steel units like the originals (the completed "Made in Australia" examples had been ferrous). By contrast, Ilya has asserted that Ivor specified that some of the engines should be ABC. He advised that of the 1,000 Elfin replicas supplied, 500 were ABC. Clearly these two versions of the story are irreconcilable. Moreover, one of the individuals most closely concerned is now deceased, as are several of his colleagues who were "there" at the time and supported his version of events based on conversations with him. Ivor's surviving notes are silent upon this matter. Since no-one has produced any conclusive documentary evidence one way or the other, I'm left with no choice other than to leave both versions on the table for readers to consider and decide for themselves. In my personal view, it scarcely matters after the passage of 30 years - what is important for the historical record is that these ABC engines were produced, for whatever reason. I have three of them myself! According to his closer associates, Ivor was far from happy with this turn of events. Nevertheless, he proceeded to check each and every unit individually, thus fulfilling his commitment to undertake the QA function. The upshot was that he ended up identifying around 250 of the Zeus Elfin engines (both ABC and ferrous) as meeting the required standards to merit the application of the Doonside name, while the rest did not. Each accepted engine was paid for, subsequently being provided with its own matching-numbered and dated test certificate hand-written by Ivor. The others were returned to Macheast without payment, thus remaining Macheast's property to dispose of as they saw fit.

Ivor advised Ilya that he was returning 750 of the Elfin replicas (plus many of the Mills replicas, of which more elsewhere) without payment, citing quality issues as his reason for rejection. Here we encounter another divergence between different versions of the story - Ilya has claimed that the quality issue was never mentioned during the "rejection" discussions and that the rejections were for other reasons. Neither Ivor's diary entries nor the stated recollections of a number of Ivor's closer associates support this assertion, which therefore remains a point of controversy. As with the earlier case, I have no way of establishing the truth of this matter independently, leaving me with no choice other than to leave both versions on the table for readers to consider. Once again, in my view this is not really worth squabbling about at this distance in time - what matters is that for whatever reason, the 750 engines were returned. The returned engines have since become widely distributed, hence being able to speak for themselves, as we shall see. The outcome was that Ivor ended up selling around 250 of the Z-stamped Elfin 149 replicas produced by Macheast that met his quality standards. These were designated by Ivor as Series II Doonside Elfin replicas (the ill-fated "Made in Australia" model had been the Series I). Since Ivor was very busy fettling and testing engines during this period, the accepted units were passed along to his son Tahn Stowe to fulfil the marketing function. Tahn dispatched them to enthusiasts all over the world.

Herein lies yet another point of disagreement, and this time it's important. Along with his associates and successors, Ivor took the position that since the Doonside trade-name had been applied to his engines since the 1970's, he and only he had the right to decide which engines merited the application of the Doonside name and which did not. I must confess that I am in complete sympathy with this view - in my personal opinion, every owner of a well-respected trade-name of long standing has such a right. Ivor's well-established association with the Doonside name was widely known and respected - positive memories of the original Doonside Mills engines of the 1970's were still fresh. The application of the Doonside name conveyed Ivor's endorsement along with it, thus imparting a significant value to the use of the name. Protection of the value implied by the Doonside name gave Ivor a perfect right to require that any engines bearing that name met his standards. That's what the QA process is all about. For me, the issue comes down to whether or not Ivor recognised the "rejected" engines as Doonsides, regardless of how anyone else viewed them. Ivor's rejection of the engines strongly suggests that the application of the Doonside name to those units was not endorsed by him. Indeed, to this point no-one has been able to present any evidence to support the idea that he did endorse the application of the Doonside name to those rejected units. On the contrary, Ilya Leydman has confirmed that the name application issue was never raised during the rejection discussions, which it would have had to be if the application of the Doonside name to the rejected units was actually endorsed by Ivor. This being the case, it would appear that Ivor never authorised the application of the Doonside name to these rejected engines. Ergo, they're not Doonsides. As previously stated, they are correctly identified as Zeus Elfin replicas, since that was Ilya's own brand-name which was reflected by the apearance of the letter Z stamped onto the mounting lugs. That at least is how I choose to refer to them. In fairness, I must point out that Ilya Leydman holds a contrary view. He believes that the very fact that the engines were produced at Ivor's instigation with the intention of selling them as Doonsides (which is perfectly true) makes them all Doonsides, whether or not Ivor accepted them as such. Personally, I find little merit in this argument, but I leave the dispute on the table for readers to consider and form their own opinions. A Second-Generation Doonside Elfin 149 Replica on Test

The engine was identified on the box as a Series II example. Like all of the engines produced by Macheast, it carries the letter Z for Zeus stamped under one mounting lug. This one also carries the number 2 stamped on top of the right-hand mounting lug. Persumably this identifies it as a Series II Doonside example. This one must have slipped through Ivor's original 1994 QA net somehow, because the previously-reproduced test certificate is dated some 7 years after the first engines were supplied! Clearly this example was somehow overlooked during the initial round of testing in 1994-95, hence never have been offered for sale previously. That in turn probably explains how it remained in Tahn's possession after all these years - he found it buried in a box of Ivor's stuff which he had inherited from his Dad. Ivor clearly came across it and belatedly tested it well after the main selling push for these engines had ended. That same box was also the source of the previously-mentioned original "Made in Australia" components which I built up into the Series I engine tested earlier. I was able to acquire this certified Series II example, hence having an opportunity to set it up in the test stand and find out for myself how good one of these engines had to be to get past Ivor. Pretty good, as it turned out! Some preliminary work was required to clear out the 20-year old residual castor oil gum, but once that was done the engine seemed to be more or less perfectly fitted - the very first Macheast-produced ABC Elfin of my direct experience to exhibit such fits as received. It seems very likely that it's one of the high-graded units assembled by Ivor using mix 'n match components "borrowed" from a number of as-supplied engines, a process which Ivor referred to in his diary as "cannibalization". Ivor openly admitted to having created some 20 high-graded examples in this manner, much to the disapproval of Macheast. This is probably one of those units - the very low serial number and exemplary fitting are both consistent with this notion. Once mounted in the test stand, the ABC Doonside did indeed prove to have a perfectly appropriate piston/cylinder fit for a near-new ABC diesel, just as anticipated - a bit "pinched" around top dead centre, but not unduly so. It handled more or less exactly like its all-Australian ferrous relative tested earlier. It liked a small prime to start, but responded immediately to such a preliminary. Once running, response to the controls was all that could be desired. Vibration levels were minimal, presumably thanks to the significantly lighter aluminium alloy piston, while both controls held their settings perfectly at all times.

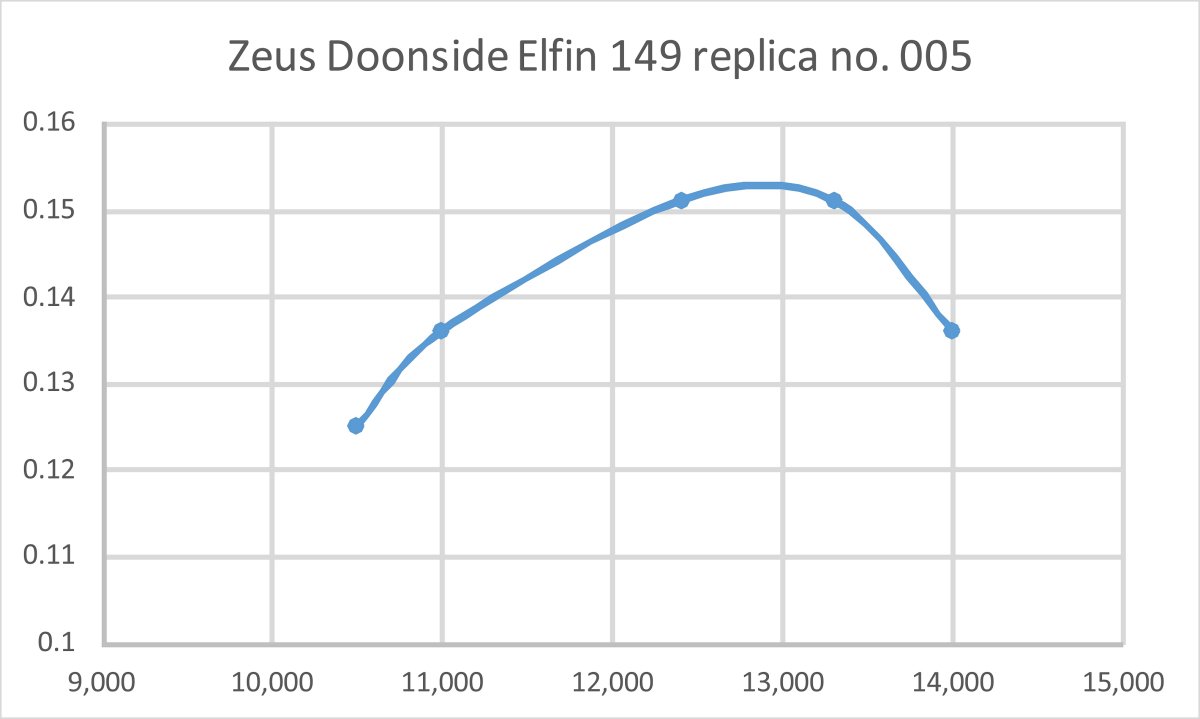

ABC engine break-in requires a somewhat different approach to that applied to the iron-and-steel variety. ABC units are dimensioned to achieve a perfect piston/cylinder fit around top dead centre when fully warmed up. To achieve this, they have to be set up a bit on the tight side when cold, with a noticeable "pinch" around top dead centre. In effect, the piston has to be a slight interference fit in the upper cylinder when cold. Consequently, such engines should be never be idly turned over compression by hand when cold, especially when new or "dry". Moreover, once started they should be quickly brought up to something approaching normal operating temperature for the break-in to be effective. The familiar approach of running at reduced compression on a rich mixture makes them run too cool to bring the components into their optimal dimensional relationship. The result will be premature wear of the crucial piston/cylinder fit in the upper cylinder. A trick that I've used successfully to achieve an initial start with an excessively-tight ABC engine is to pre-heat the upper cylinder using a powerful heat gun (not a butane torch, please!) with the piston set at bottom dead centre so that it stays relatively cool. This generally relieves the fit to the point that a start is readily achieved. I've found that only a few starts and 5-minute runs using this approach are usually required to bring things to a state in which normal cold-starting procedures can be applied. In this case, such measures were clearly not required. I followed Ivor's lead by starting the engine on an APC 8x4 prop in the usual way, immediately adjusting it for best running. I then backed off the compression fractionally and opened the needle a little, maintaining smooth two-stroke operation for most of the time. This allows the components to run themselves in at something approaching normal operating temperature, albeit at a slightly reduced speed and with a little extra lubrication. As with the iron-and-steel types, I still leaned the engine out all the way for the last 30 seconds or so. After 30 minutes of this in 5-minute runs (plus whatever running time Ivor had given it), the piston/cylinder fit seemed to be approaching perfection. A small amount of detectable play had developed in the conrod bearings, but nothing to prevent the engine from giving a good test performance. I therefore ran the same series of calibrated test props that I had used previously for the all-Aussie Series I Doonside replica. Starting remained very easy, while running was absolutely smooth and steady on all props tested. The results were as shown below.

The above data make it clear that this engine outperformed the previously-tested all-Australian Doonside model by a substantial margin. The implied output is around 0.153 BHP @ 12,800 rpm - very much in line with the figures reported by Peter Chinn for the original Aerol product. Overall, Ivor-certified Zeus ABC Elfin 149 Series II Doonside replica no. Z-005 showed itself to be an excellent model powerplant which would have served its owner well. It might well show a further improvement with more running time. To do full justice to its manufacturers, it's important to remember that this engine is a high-graded example of those manufactured by Macheast at Ivor's instigation (setting aside the debated issue of the ABC piston/cylinder technology) - it bears the Z (for Zeus) stamping of all the Macheast units along with its Ivor-assigned serial number. Moreover, engine no. Z-005 is apparently typical of the Ivor-certified ABC units. Reader David Hill of England confirmed this impression. He owned Ivor-certified Series II Doonside ABC engine no. Z-083, which was apparently quite tight as received, just like my example. However, following a proper break-in using the correct procedures, it turned out to be "a superb, strong-running engine". If they had all been this good, Ivor would have had no legitimate cause for complaint or rejection. But they weren't ................. as we've already seen, a considerable number of engines were returned to Macheast, supposedly on the basis of failing to meet the standards required to bear the Doonside name. This initiated the next phase of this saga. The Zeus Elfin Replicas After the dust had settled on this stage of the affair, Ilya Leydman found himself in 1995 saddled with a lot of unsold Ivor-reject Zeus Elfins that he now had to get rid of to recoup his costs. If you accept Ivor's account of his reasons for rejection (and that's up to you), it inevitably follows that these engines might be expected to be flawed in some way, since they had failed to get past Ivor, who evidently kept the good 'uns and returned the rest. The examples which had contributed components to Ivor's "cannibalization" procedure must have been particularly bad - in fact, Ivor specifically confirmed this in his diary.

Naturally, any flaws that may have caused these engines to be rejected by Ivor would still have been there, a possibility which the experiences of many purchasers (myself included) appear to support. In that regard, I can only say that every uncertified Zeus example of my own direct acquaintance has been flawed in some way. This doesn't prove that they all were, but it is certainly suggestive. Interestingly enough, Ivor's incomplete diary pages include a reference to this matter. Ivor expressed the view that by selling the rejected engines in competition with the Series II Doonside units at prices which undercut the latter, Macheast had broken the handshake agreement that all motors would be sold through Ivor's Sesqui Engineering company. Having sided with Ivor on one of the contentious issues discussed previously (the Doonside name application controversy), I now have to say that I find his logic here to be totally lacking in credibility. Ivor was offered the opportunity to sell all of the engines as agreed - all were sent to him for his acceptance or rejection. By rejecting many of the engines, he was forgoing his option to market those examples. Consequently, any marketing agreement which may have existed no longer applied to the rejected units. They remained the property of Ilya Leydman and Macheast, who therefore had a perfect right to sell the engines on their own account at whatever price they deemed appropriate. However, they did not have the right to sell the rejected engines as Doonsides - at least, that's my firmly-held view. Unfortunately for Macheast and their agents, the reputation of the Ivor rejects preceded them. Consequently, the Zeus replicas hung about for decades. As late as August 2021, well over 25 years after their manufacture, New-in-Box examples of both ABC and ferrous Zeus Elfins still remained readily available from Ed Carlson, priced at US$55.00 plus postage. I'm not sure how long this situation will continue - all that I can say is that Ed reported retaining a fairly good stock as of that date. As of 2021, Ilya Leydman was also still selling the engines periodically on eBay, sometimes presenting them as Doonsides, a designation which I personally do not accept for the reasons stated earlier. Be aware that if you buy one of the Z-stamped examples (whether ABC or ferrous) that doesn’t have a genuine matching certificate signed by Ivor, you’re almost certainly getting one of Ivor’s rejects, regardless of the source and however it's described in the offering! That won’t necessarily prevent it from running, but it may present set-up challenges …………… all of the uncertified New-in-Box examples that I've seen (5 of which I still own myself) have required significant skilled interevention to get them to run. Maybe I've just been unlucky .......... The story doesn’t quite end there. Chris Murphy tells us that Macheast had a New Zealand agent, the late Des McAnelly, who was a noted C/L speed flier and engine wizard. The Zeus Elfins and the Russian MK-17 diesels were the biggest sellers in New Zealand, and Des quickly realised (correctly in my experience) that the most pervasive problem with the Zeus ABC Elfins was that they were generally set up too tight and with too much bore taper. He personally checked every engine that passed through his hands. Having both the equipment and the engine knowledge, he honed the liners to improve the fits. Consequently, a Des McAnelly breathed-on Zeus Elfin 149 ABC “reject” was typically a better engine than one of the “passed Ivor F quality control” certified Series II Doonside examples! Chris Murphy should know, since he has four of these replicas in total - the mega-rare original Ivor F Australian-made ferrous example which he actually saw Ivor assemble; an Ivor F certified ABC Series II Doonside unit produced by Macheast; a Des McAnelly honed “reject” ABC Zeus example; and an ABC Zeus unit obtained second hand, of unknown provenance but very likely one of the reject units imported by Des into New Zealand but never fettled by him.

A group of my own examples is shown at the right along with the original Elfin 149 PB seen at the top left. Going clockwise from that unit, they are: an original "Made in Australia" Doonside Elfin replica; a certified ABC Series II Doonside Elfin replica; and an uncertified Zeus iron-and-steel Elfin replica. As can readily be seen, they all look the part! All have been successfuly test-run. To sum up, the Australian Elfin 149 PB replica sequence went as follows:

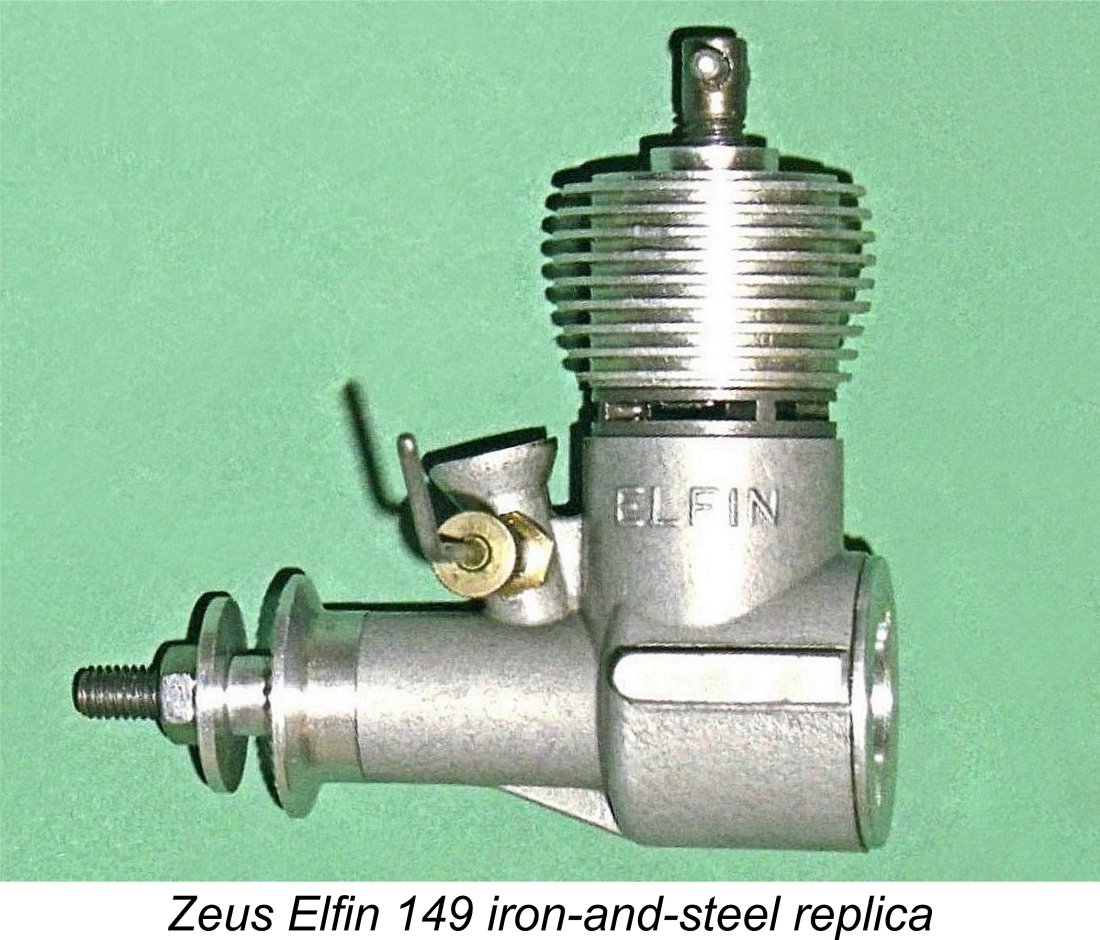

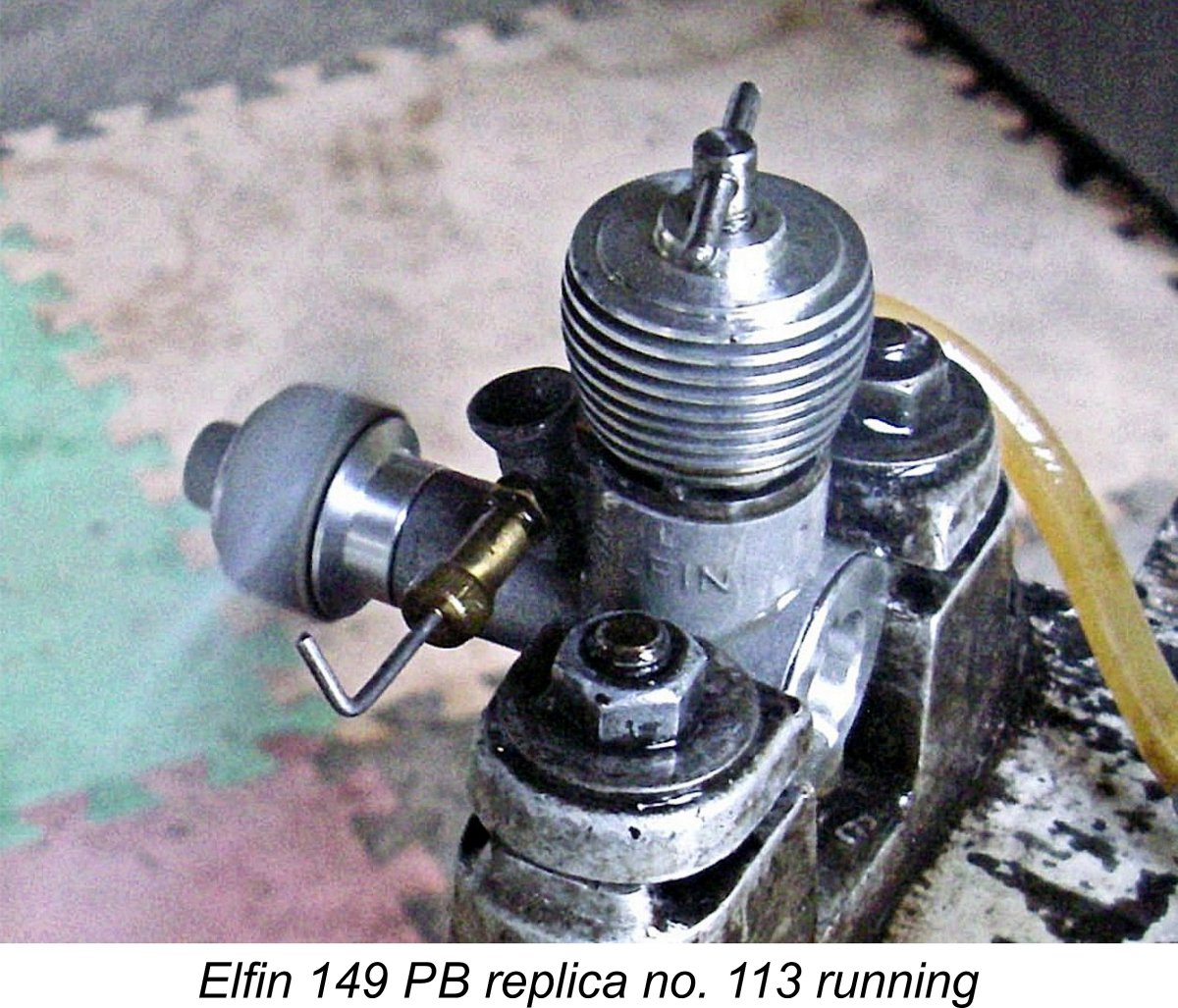

Now before we move on, it's worth reminding readers at this point that the Macheast-produced Elfin replicas were accompanied by some 500 Z-stamped examples of a Mills .75 replica which was also manufactured in both iron-and-steel and ABC versions. I've reviewed those units in detail in the "Australian" section of my separate article on the Mills replicas produced around the world. Readers having an interest in those models are referred to that article. The Zeus Elfin 149 PB Replica – Brief Description Returning to the Elfin replicas which form our main subject here, it should be clear from the foregoing discussion that the variant which is by far the most likely to be encountered today is the Ivor-reject Zeus unit in either ABC or ferrous configuration. This being the case, it seems worthwhile spending a little time describing this rendition more fully. In attempting this, I'll take my own ferrous test example no. Z-113 as my yardstick. The ABC variant is more or less identical apart from the materials used in the piston/cylinder combination. One issue facing any replicator of a given engine is – which version to replicate?!? Although the Elfin 149 PB remained largely unchanged throughout its production life, the number of fins on the screw-on cooling jacket did change over time. The early example tested by Sparey had 13 very thin fins, as did the example tested by Chinn. I have three engines of this early type myself, one of which is illustrated at the top of this article. Later they went to a cooling jacket having a smaller number of thicker cooling fins, usually nine but sometimes only eight. Ya pays yer money, ya takes yer choice ………..

It has to be said that the Zeus Elfin is a generally satisfying visual rendition of the original. It is however readily distinguishable "across the room" from the original Aerol product. For starters, the cleanly-cast crankcase is vapour-blasted instead of being left more or less in its as-cast state. The oval border around the “149” designation on the right-hand side of the original’s upper crankcase is omitted on the replica, as is the “Made in England” statement cast onto the lower left hand side of the original Elfin crankcase. The form of the case is generally very similar, although the replica has shorter mounting lugs of greater thickness. Once again, the mounting hole spacing is completely different, with the holes more closely spaced longitudinally and more widely spaced laterally. This prevents a switch from an original to a replica in the same model - in fact, a Zeus replica can't even be exchanged with a made-in-Australia Doonside unit. I've already stated my firmly-held opinion that mounting hole spacing is Further differences are to be seen in the Russian-made needle valve assembly. The spraybar on the replica is notable for featuring a spherical “bubble” expansion centered over the single jet hole in the spraybar. This was created by reducing the spraybar diameter on either side of the jet, resulting in an extra restriction of the venturi at the jet location. Ron Chernich's attached image should make this clear. The Zeus replica follows the lead of the original Australian Doonside units in having a slightly enlarged venturi choke area to go along with the unusual spraybar configuration described above. The intent here was seemingly to maximise effective choke area while maintaining the best possible suction. The theory was seemingly that placing the maximum restriction in terms of spraybar diameter at the jet location should maximize air velocity and hence suction at that location.

Internally, the two engines are pretty much identical in functional terms. The steel cylinder features four sawn exhaust ports with four internal bypass/transfer flutes located below them in a staggered arrangement. The width of the transfer flutes precludes any overlap between the exhaust and transfer ports. The cast iron piston has a shallow conical crown which is matched by the contra-piston. The typical British-style “dog bone” turned light alloy conrod drives a one-piece steel crankshaft having an unbalanced plain disc crankweb. Ron Chernich's attached image should clarify most of these details.

Avoidance of any possibility of bypass fouling would require the use of a crankcase/cylinder combination which aligned the end of the pin with the exhausts rather than the transfers when the cylinder is fully tightened – something to check before running an Elfin. It must be said that the staked arrangement appears to be a preferable approach. The other relevant observation relates to the bore of the Zeus replica. I don’t know whether or not my three iron-and-steel examples (all acquired NIB from Ed Carlson) are typical, but I have to say that all three of their bores presented quite the worst finish of any model diesel of my 60 plus year acquaintance – even worse than my previously-mentioned Zeus Mills .75. test engine, and that was bad enough. The Zeus Elfin bores all had a very rough appearance which imparted a “scratchy” feel to the engines when one attempted to turn them over (don't try too hard!). They had been honed, but it was clear that a very coarse hone had been used which was not followed up as it should have been with a micro-hone or a lap. Since several other new and unrun examples which I have examined for other owners displayed exactly the same condition, I have reasonable cause to believe it to be typical of these engines.

In the end it came out not too badly, although by the time that I had a reasonable bore the compression seal ended up somewhat less secure than I would have liked. Even so, the fact that I was able to lap off as much as I did and still end up with a useable fit is an eloquent testament to the extreme tightness of the fit as received. The bore issue is a pity, because in other respects the engine is a very nice-looking unit which is quite well made and fitted. I’d recommend that anyone buying one of these units try to get a “tight” one and take the time to lap the bore to a better form and finish before so much as trying to run the engine or even turning it over. Once this was done for my example, it gave the impression that it should be quite serviceable despite the somewhat “soft” compression seal. The two examples of the ABC Zeus replica that I currently own (engine nos. Z-537 and Z-577) both suffer from what Chris Murphy tells me is the common problem of a too-tight piston in an excessively-tapered bore. I've never even tried to run them, nor do I have the necessary capability to relieve the fit. Where's Des McAnelly when you need him?!? As they stand, I doubt that I could start either of them, even with my cylinder-warming technique. Since I've handled several other examples owned by acquaintances that suffered from the same condition, there is good reason to believe that it may indeed be typical. The Zeus replicas are all serial-numbered. My illustrated "improved" ferrous test example of that replica is engine number Z-113. The number is neatly stamped into the underside of the left-hand mounting lug, while the underside of the other lug is stamped with the letter Z to stand for Macheast's Zeus trade-name. My other two ferrous Z-prefixed examples are numbered Z-333 and Z-378 respectively. At the time of writing in early 2022, David Hill of England owned Ivor-certified ABC engine no. Z-083, while Chris Murphy owned ABC engines nos. Z-115 and Z-157. Engine no. Z-115 appears to be one of the Des McAnelly reworked examples. It's also very interesting to note that it's only 2 units away from my ferrous test engine no. Z-113. The implication is that the two cylinder types were all mixed in together in the numbering sequence. My previously-discussed Ivor-certified ABC unit bears the very low number Z-005, while my two uncertified Zeus ABC examples bear the numbers Z-537 and Z-577. Tim Dannels had uncertified ABC Elfin no. Z-226 through his hands in early 2022. By contrast, the majority of the original Aerol units do not bear serial numbers. There are exceptions – the late Ron Chernich owned engine number 5757 (with a separate 59 prefix, the meaning of which is unclear), while I own the previously-illustrated original example number 5643 (no prefix). My other four original units have no number. So how well does my "massaged" Zeus ferrous replica perform on the test bench?!? Let’s find out! The Zeus Elfin Iron-and-Steel 149 PB on Test As stated earlier, the “adjusted” piston fit in my test ferrous example of the Zeus Elfin (number Z-113) had ended up being slightly looser than I would consider to be ideal. This was due to the amount of material that had to be lapped off to achieve a functional bore finish. Nonetheless, I found that there was more than adequate residual compression for starting, without the need to resort to an oil prime to generate a sufficient seal.

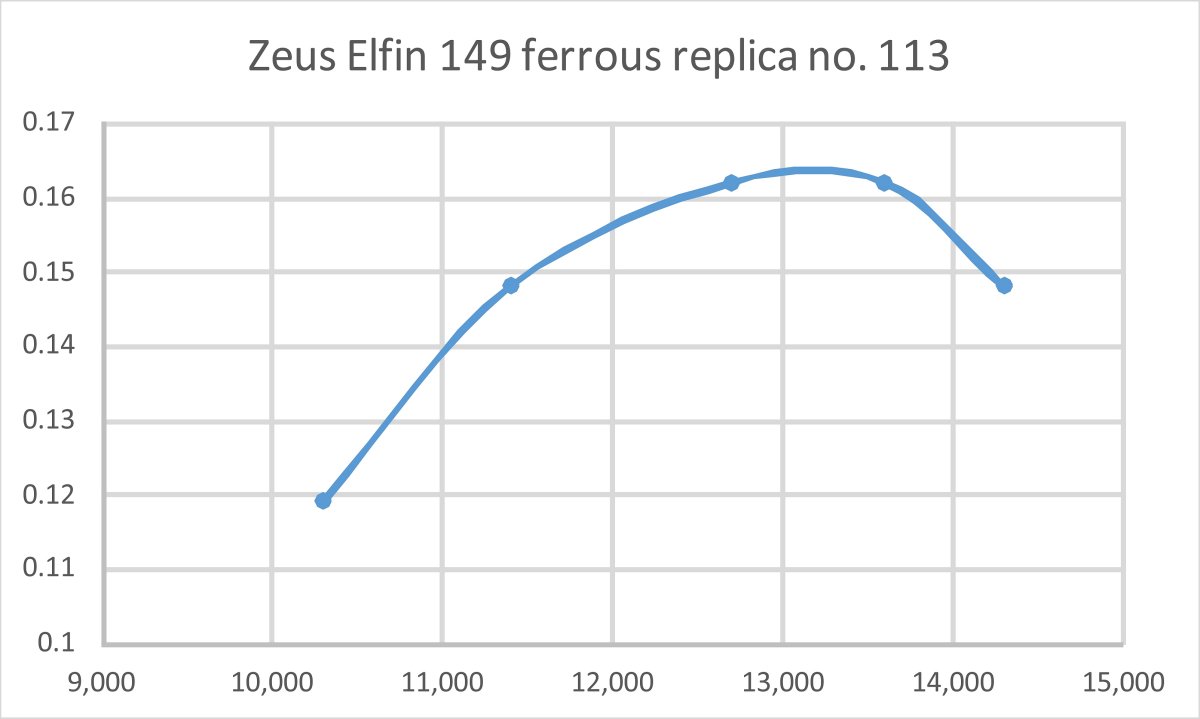

Like the other replicas tested as reported earlier, the engine liked a prime for starting, but once this was given it came to life very promptly within a few flicks. Response to both controls was very positive, making the establishment of the optimum setting perfectly straightforward. Running was commendably smooth and mis-free, with no tendency to sag as things heated up. Both controls held their settings perfectly. The compression seal actually improved very slightly during this period. This is because a cast iron piston tends to "grow" microscopically over its first dozen or more full-range heat cycles. I've explained this characteristic more fully in my separate article on iron-and-steel diesel break-in. In addition, the castor oil in the fuel encourages the build-up of a persistent coating on the bore and piston skirt which helps to create a seal. Once that's built up, don't wash it off! Following the completion of the break-in, I switched to appropriate members of my usual set of calibrated test props. The engine continued to perform very well as I developed a series of prop/rpm figures for those airscrews. The results are summarized below:

The implied output is around 0.163 BHP @ 13,200 rpm. These are the best figures measured for any of the three replicas tested for this article. However we might expect this - thanks to my lapping efforts, engine no. Z-113 is by far the best freed-up example for which data were obtained, with no trace of tightness. As with the previously-tested ABC unit no. Z-005, these figures are well up to par with those reported far earlier by Peter Chinn for the original Elfin 149 PB - in fact, the peak output of engine no. Z-113 is very slightly higher. I suppose that this shouldn't really come as much of a surprise given the fact that this unit is a very close facsimile of the original with a slightly larger intake choke area and an extremely free-running bore. However, it was nice to see that Macheast's efforts had resulted in an engine that would serve as a very acceptable substitute for the real thing in performance terms, even if a fair bit of work was required to get it to that point. It also looks very much the part. As with its ABC compatriot tested earlier, a detectable amount of play had developed in the engine's con-rod bearings at the end of the test. Of course, that's not at all uncommon with the classic British "dog bone" design employed. The configuration results in a small end bearing that is very short and prone to "wandering" on the wrist pin. However, the major criticism undoubtedly relates to that very poor bore fit and finish which required some careful attention to overcome, ending up leaving the compression seal somewhat less secure than ideal. Even so, I would guess that the engine would provide a good few hours of satisfactory service, particularly if supplied with a steady diet of a relatively "oily" castor-based fuel. Not having successfully tested an uncertified example, I can't comment on the relative performance potential of the Ivor-reject Zeus ABC version. I can only say that if an owner was successful in getting one to run, there's no reason why it shouldn't perform up to the level displayed by Ivor-certified ABC engine no. Z-005 tested earlier. See below for some test data received from Maris Dislers following the initial publication of this article. The one point of interest that might have a bearing on this issue is the fact that the ABC model weighs 4 gm less than its iron-and-steel counterpart (78 gm vs. 82 gm). Since the brass cylinder actually has an 8% higher material density than its steel counterpart, the lower weight must be related to the reduction in reciprocating weight represented by the alloy piston as compared to its cast iron counterpart. Lower reciprocating weight tends to favour higher performance ....... That said, the extreme tightness of the piston/cylinder combinations in both my unrun ABC examples suggests that it would probably take some fettling by someone with the skill set exemplified by the late Des McAnelly to get the best out of one, or even to get it running at all. None of the uncertified ABC units that I've examined previously (including my own two examples) have been in a condition to run. That said, my very positive experience with Ivor-certified Series II Doonside ABC replica no. Z-005 proves beyond argument that the ABC technology had the potential to work very well in this design if it was properly executed in the first place. The concept was fine - it was consistency of execution that seems to have let it down. Testing in Australia Following the initial publication of this article, my good mate Maris Dislers contacted me to make me aware of a number of tests of the Elfin replicas which had been conducted earlier in Australia. The first of these was a test of both ABC and ferrous variants of the Zeus Elfin 149 replica by the late Brian Winch. Brian’s test was published in the November 1995 issue of the Australian modelling periodical “Airborne”. I had completely missed this reference. This test is quite revealing with respect to the prevalence of the assembly issues highlighted earlier. Brian found that both models suffered from excessively-tight and overly-tapered piston/cylinder fits. In his case, the ferrous example was the worse of the two - it couldn’t even be turned over by hand unless the contra piston was backed way off. This finding seems to provide further support for my earlier comments regarding the typical piston/cylinder fits in these engines. In typical Brian Winch fashion, the tester’s response was to reach for his electric starter! Brian was notorious for being one of the very few advocates of the use of an electric starter on diesels. In this instance, he used the starter to force the engines through an excessively tight fit at top dead centre, rather than taking steps to relieve the fit in advance. He went so far as to give the ferrous example a series of starter-powered “runs” with the compression backed way off, just to relieve the fit a little. Even then, after loosening things enough to permit the engine to start and run, he continued to use the electric starter. Personally, I find this treatment to be quite inappropriate - the stresses on the working components must have been severe, particularly the tension imposed on the rod while pulling the piston out of the top dead centre interference fit. Brian was lucky not to break or distort something, in my view anyway. Once freed up sufficiently to receive a more “normal” running-in period with the compression setting re-established, both engines apparently started and ran very well. However, they didn’t seem to develop much in the way of power. The ABC unit turned a Taipan 7x4 prop at only 12,300 RPM, implying an output at that speed of around 0.12 BHP. All of my own examples managed considerably higher speeds on the admittedly slightly "faster" APC 7x4 prop. Even more surprisingly, Brian's ferrous example was found on average to be around 1,000 RPM down on his under-performing ABC unit, although this performance gap apparently narrowed a little with more running time following the test. My own ferrous example clearly outperformed Brian's test unit by a very considerable margin. Apart from his adventures with the excessively-tight and over-tapered piston/cylinder fits, Brian had little but praise for the quality of the engines’ construction in other areas, stating that they ”gave the impression of being very well designed and very well made”. He felt that “due to the use of modern alloys and machining (the engines) could actually be better than the original(s)”. In terms of their potential, my own tests reported earlier confirmed that this statement was very likely true once the piston/cylinder issues were sorted in some way. Not to be outdone, Maris Dislers also reported that he had run his own test of a "good" Zeus ABC replica against an original Aerol Elfin 149 PB which he had assembled from a stash of spare original components. The results were most interesting, as follows:

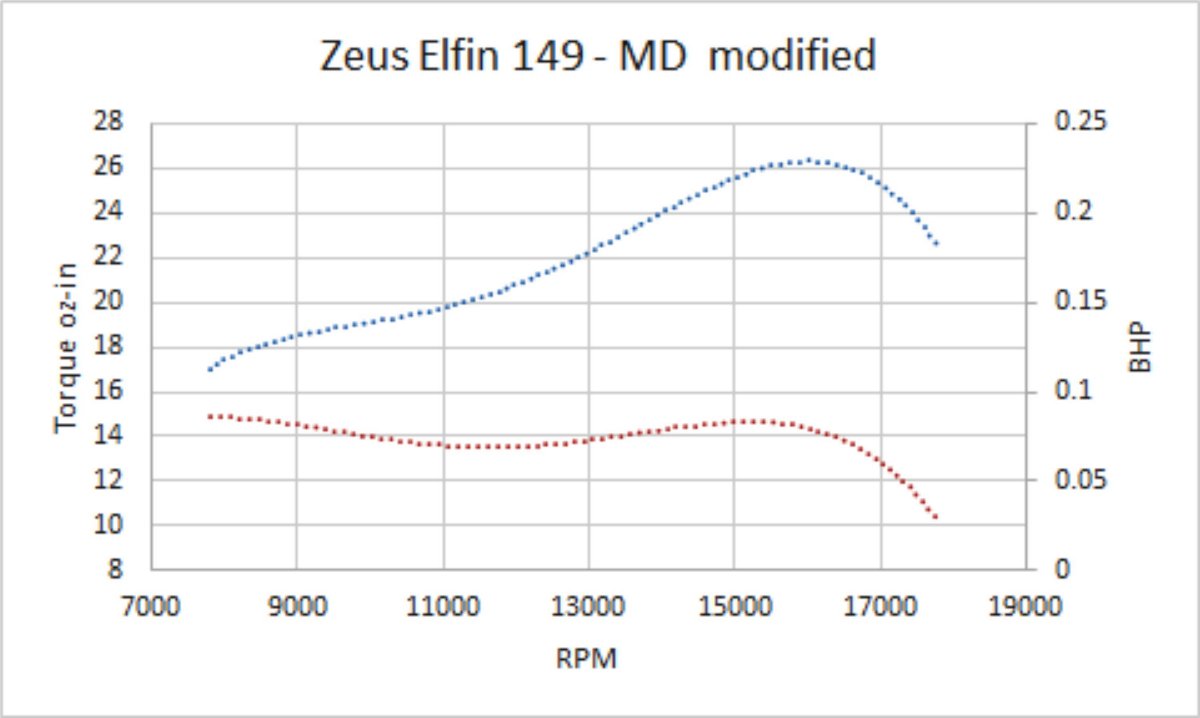

Maris’s Zeus ABC replica did somewhat better at the top end than my own admittedly still-tight Ivor-certified Series 2 Doonside example tested earlier. However, it came nowhere near matching the cobbled-together original Elfin unit which Maris had constructed from components. Still, a perfectly acceptable performance for the Zeus example. Maris also had some fun playing with an example of the ferrous Zeus replica. As received, it was a non-runner due to the usual combination of a poor bore finish allied to an excessively tight piston. Maris re-lapped the cylinder to a more appropriate finish and taper, after which he made a new piston and contra piston to suit. Finding that the engine had seemingly excessive timing figures of 164 degrees exhaust and 142 degrees transfer, he raised the top of the transfer flutes to reduce the engine’s blow-down period and then machined the deck on top of the crankcase to lower the cylinder, producing more appropriate exhaust/transfer timing figures of 142 degrees and 132 degrees respectively. Maris also did some work on the crankshaft, extending the induction period from 160 degrees up to a full 190 degrees, with earlier opening (40 deg. ABDC) and later closure (50 deg. ATDC). He also ground material off the crankdisc to introduce a degree of counterbalance. With these modifications aboard, the Zeus Elfin was completely transformed! Sample prop/RPM figures included the following:

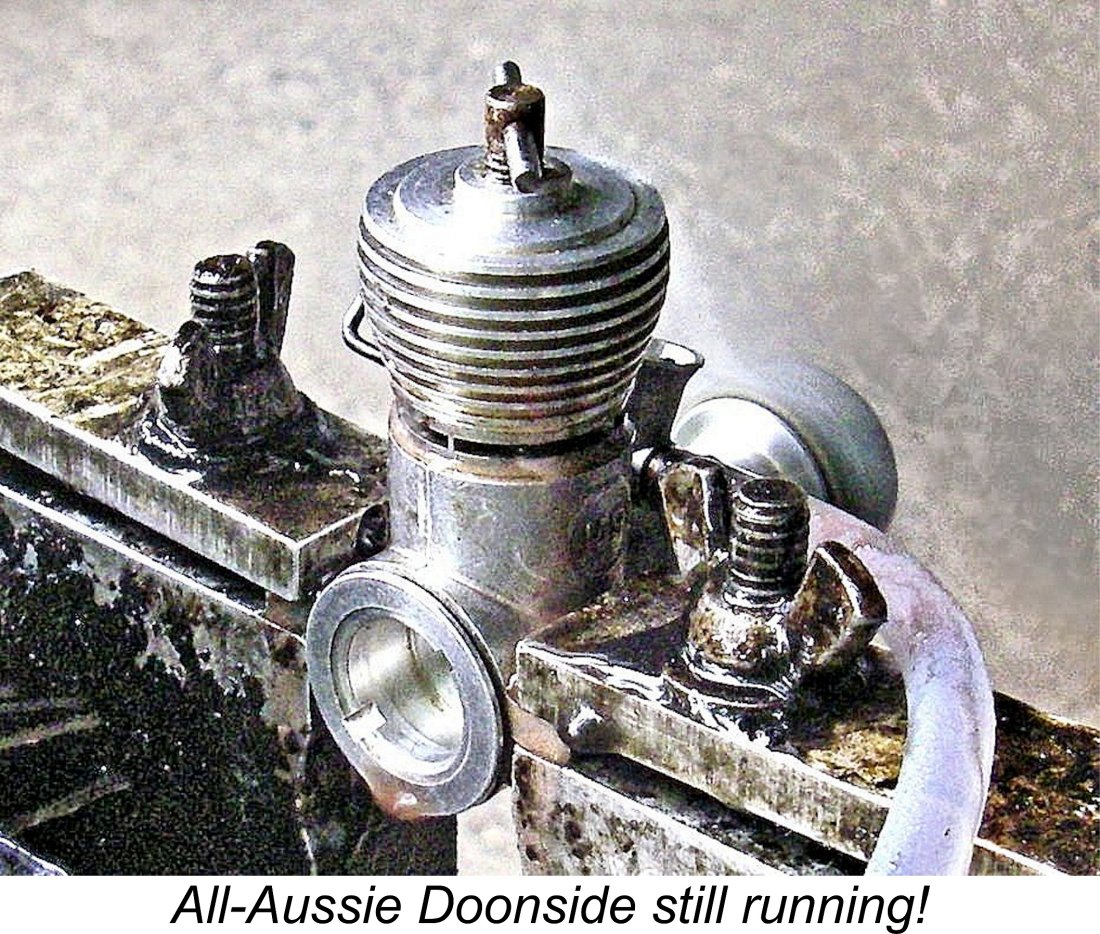

As can be seen from the derived power curves, the modified engine delivered a sterling performance, developing a maximum of around 0.226 BHP @ 16,000 rpm. No stock Elfin 149 PB ever got near those figures! Of course, the engine as tested was no longer a Zeus replica in functional terms, having a re-lapped and re-timed cylinder to go along with a new piston and contra piston as well as a significantly modified shaft. Still, these results show how much potential was there in the basic Elfin 149 PB design! My own figures reported earlier for my freed-up but otherwise unmodified Zeus iron-and-steel replica are doubtless far more indicative of the engine’s true potential as delivered. And they’re really not that bad!! Maris’s closing comment was that apart from the piston/cylinder issues which appear to be more or less universal, the rest of the Zeus replica is actually really good. I’d echo this comment based on my own experiences. It’s really too bad that they got the piston/cylinder components so woefully wrong! The Steve Todd Elfin Replicas I mentioned earlier that Steve Todd was involved in the production of the original Doonside Elfin replicas. I noted that he had produced some 30 examples to assist Ivor F in filling outstanding orders, using partially-completed components supplied by Ivor. Upon learning that I was planning to publish this article, Steve was kind enough to get in touch to supply some additional information. At the time in question, Steve's workshop was located at Karangi near Coffs Harbour in New South Wales. The hardened and ground piston/cylinder sets were supplied by Ivor complete with contra piston and con-rod. The crankshafts were also completed, including hardening and grinding. Consequently, Steve’s main contribution was finishing off some of the machining operations for the crankcase and needle valve assemblies, as well as assembling and testing the completed engines.

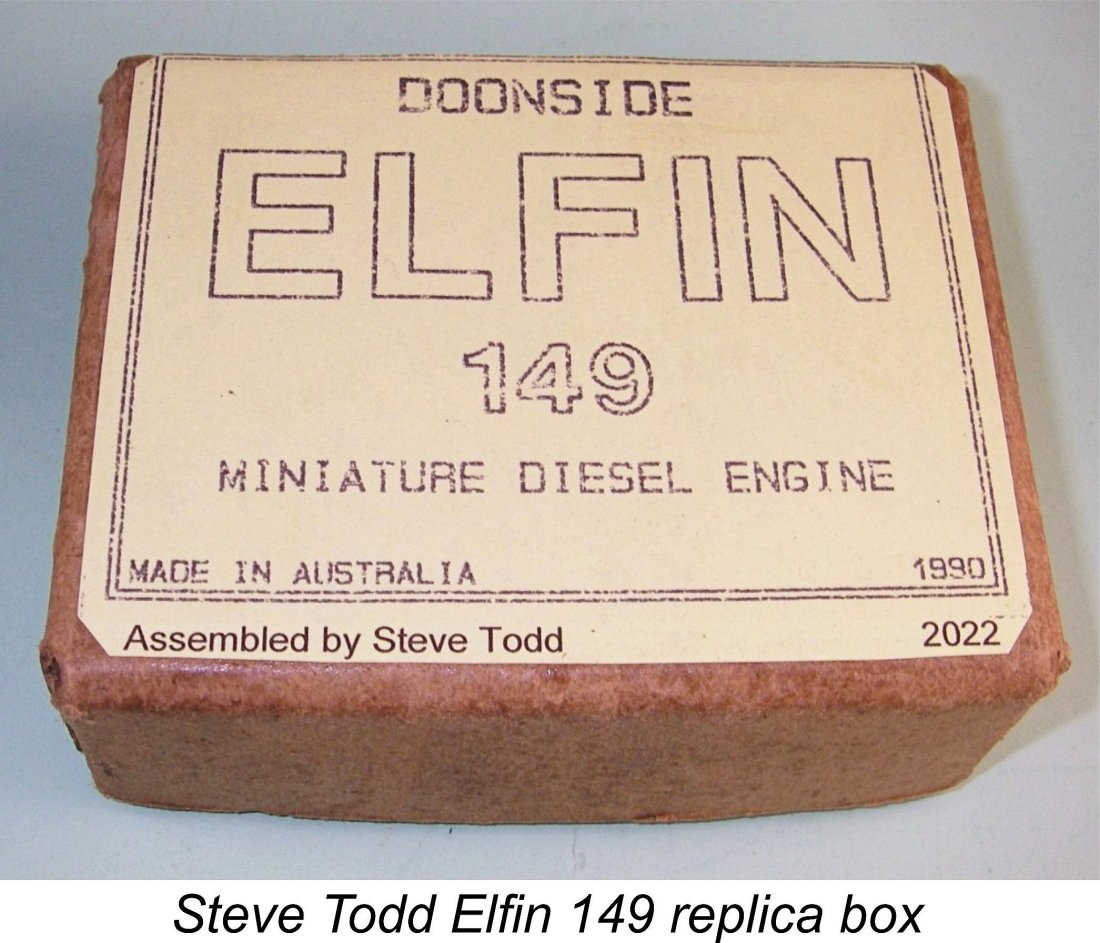

However, this story had a twist to its tail! Steve subsequently moved from Coffs Harbour to Bribie Island in Queensland. Following this move, in January 2022 he came across a box of engine components that he had packed away several years earlier and subsequently forgotten prior to the move. The box turned out to contain 6 unfinished Doonside Elfin 149 crankcases along with many other components. Treasure trove indeed! Steve found that he had enough of the key components to potentially make 6 more engines, the main shortfalls being two cylinder heads and two crankshafts. Fortuitously, Steve was able to obtain these components from Ivor’s previously-mentioned son Tahn Stowe. In the box of bits there was a smaller box containing about 50 or so aluminium alloy contra pistons which had been made on a CNC lathe by either Gordon or Peter Burford. Steve recalled Ivor telling him some years earlier that he was planning to assemble a number of the Elfins with aluminium contra-pistons fitted with a high temperature Viton “O” ring to create a seal. Ivor never got around to carrying through on his intention, so Steve decided that it was down to him to make a few engines with the aluminium contra pistons just to see how they would run.

Steve kept the number 1 diesel and the number 1 glow-plug for his own collection, designating the remaining 3 diesels and 1 glow for sale to collectors. These engines were made completely from original Doonside Elfin components apart from the glow-plug head inserts. They were entirely finished and assembled by Steve, accordingly being stamped “S T” on the top of one lug with the number of the engine on the top of the other lug. The four diesels also had the letter “A” stamped under one of the lugs to denote the fact that they were fitted with aluminium contra pistons.

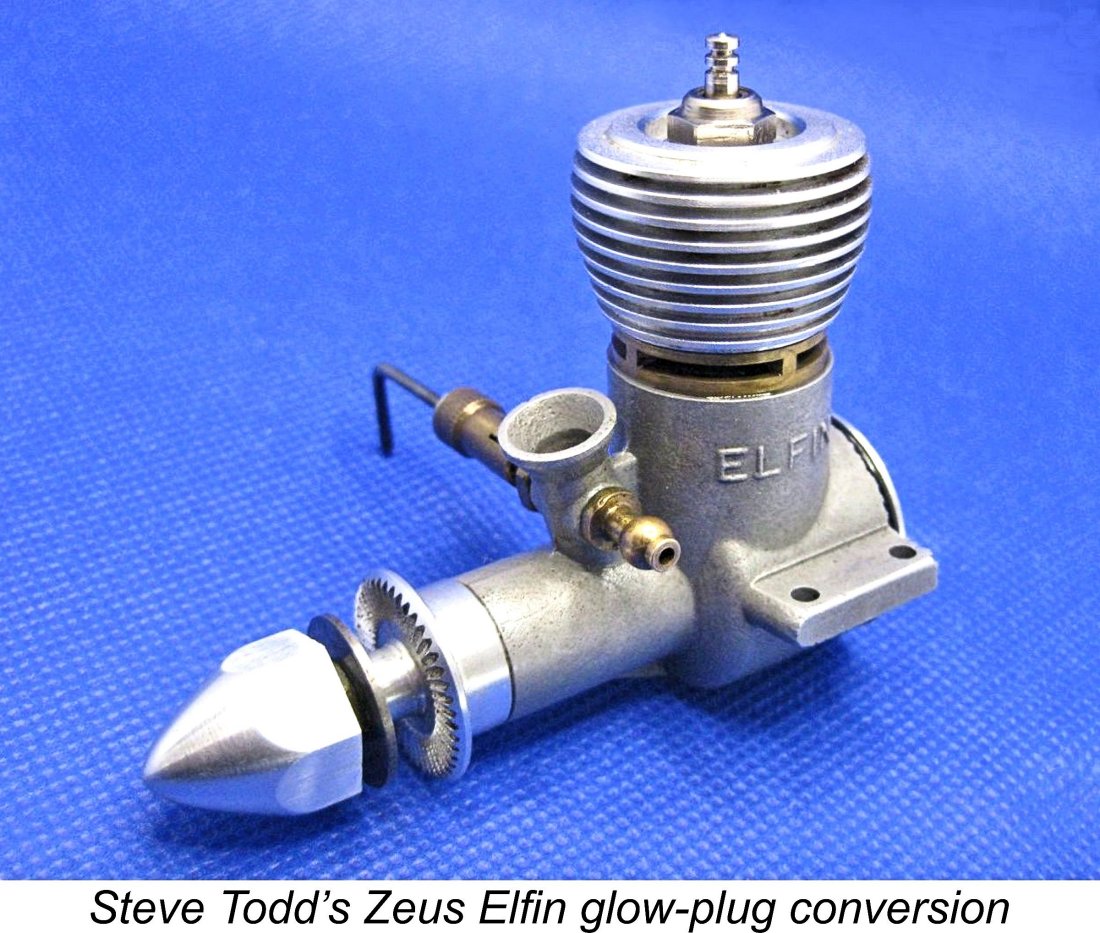

Needless to say, I was quite overwhelmed by Steve's generosity! I will treasure this gift from a talented model engineer and a good friend. Given the very small number of these replicas assembled by Steve, the chances of finding one are pretty remote unless you get as lucky as I did! Even so, you never know what the future may bring - if you're ever fortunate enough to become one of the select group of owners of a Steve Todd Doonside Elfin, Steve's involvement in this story doesn't even end here! In early 2022 a friend of Steve's gave him an example of the ABC Zeus Elfin 149 replica which he couldn't start. Steve's friend asked him if he could fix it and convert it into a glow-plug model. On stripping it down, Steve found that the contra-piston was a very loose fit and there was also a massive amount of play in the conrod little end. Like all of these engines, the piston/cylinder fit was a bit on the tight side. However, Steve persevered, fitting a new rod and trying two successive head button designs. Once sorted, the engine ran very smoothly and re-started 1st or 2nd flick when hot. Despite the fact that it was still a touch tight when Steve ran it, the engine managed 14,000 RPM on an APC 7x4 prop, with further improvement expected following some more running-in. Conclusion

I suspect that the poor bore fit and finish in my test ferrous example and its two companions in my possession are typical of the uncertified examples, leading me to expect that some effort will often be required to get one of these engines into good running order. Even then, its useful service life might be relatively short before a rebore became necessary. That having been said, one could almost treat this as a "disposable" engine, since they still appear to be quite readily available at reasonable cost, even in 2022, no less than 29 years after their manufacture. The Ivor-reject Zeus ABC variant may be a bit more problematic - re-finishing an ABC bore is a very skilled exercise that will be beyond the capability of most owners. Certainly, I've never tried it myself. Still, it's by no means impossible that a dedicated owner might be able to get one of these units running by one means or another. As stated earlier, new boxed examples of the uncertified Zeus Elfins in both iron-and-steel and ABC configurations remained available from Ed Carlson in August 2021 at a very reasonable price of US$55.00 plus postage. Despite the warts identified in this report, I'd still consider this to be quite good value for money. If interested, give Ed's son Randy a call at 602–863–1684. For me, the main benefit conferred upon the "traditional" modelling world by these Zeus replicas is the ability to fly an "Elfin"-powered model while sparing a more valuable original from undue wear and tear. If the manufacturers had only duplicated the mounting hole arrangement, thus making the replica directly interchangable with an original in the same model, all would be perfect. However, the use of mounting plates allows this issue to be overcome quite easily. So if you want to try an Elfin 149 PB but can't find an original, here's a practical alternative. Just be prepared for a few issues requiring attention, and you should end up with a perfectly useable engine! It may not last forever, but you have an alternative even then - buy another! ____________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published March 2022

|

||||

| |

In this article, I’ll do my best to untangle the surprisingly complex story of the Elfin 149 plain bearing (PB) diesel replicas which emerged from Australian sources, primarily in the 1980's and 1990’s. Examples of the best-known of these units are still not infrequently encountered today on eBay and elsewhere. It's a convoluted story with a certain amount of controversy attached and a bit of a twist to the tail - the kind of subject that is the most fun to research and write up!

In this article, I’ll do my best to untangle the surprisingly complex story of the Elfin 149 plain bearing (PB) diesel replicas which emerged from Australian sources, primarily in the 1980's and 1990’s. Examples of the best-known of these units are still not infrequently encountered today on eBay and elsewhere. It's a convoluted story with a certain amount of controversy attached and a bit of a twist to the tail - the kind of subject that is the most fun to research and write up!  There are certain classic model engines whose notable qualities and consequent desirability have created a demand for them which the finite number of surviving original examples in circulation has proved insufficient to meet. In a number of instances, this created market conditions under which the series production of replicas of the engines became an economically viable proposition.

There are certain classic model engines whose notable qualities and consequent desirability have created a demand for them which the finite number of surviving original examples in circulation has proved insufficient to meet. In a number of instances, this created market conditions under which the series production of replicas of the engines became an economically viable proposition.  Another notable member of the Elfin range which has been the focus of repeated replication efforts is the 1.5 cc Elfin 149 PB unit which was introduced by Aerol Engineering in 1950 along with the beam mount version of the Elfin 249 PB. The light and powerful Elfin 149 PB was a huge success, ultimately becoming the most popular Elfin model of them all. It remained in production for some 7 years, achieving an enviable record of stellar competition successes along the way.

Another notable member of the Elfin range which has been the focus of repeated replication efforts is the 1.5 cc Elfin 149 PB unit which was introduced by Aerol Engineering in 1950 along with the beam mount version of the Elfin 249 PB. The light and powerful Elfin 149 PB was a huge success, ultimately becoming the most popular Elfin model of them all. It remained in production for some 7 years, achieving an enviable record of stellar competition successes along the way.  So there was nothing at all wrong with the performance of a good example of the original Elfin 149 PB. Its main Achilles Heel, and indeed that of all of the Elfin models in the 1950’s, was a decided variability in quality, doubtless arising from the enforced ongoing use of well-worn production equipment. A good one was really good, but not all of them came up to that standard. This may well explain the difference between the results reported by Chinn and Sparey – Chinn may have simply got a “good ‘un”!

So there was nothing at all wrong with the performance of a good example of the original Elfin 149 PB. Its main Achilles Heel, and indeed that of all of the Elfin models in the 1950’s, was a decided variability in quality, doubtless arising from the enforced ongoing use of well-worn production equipment. A good one was really good, but not all of them came up to that standard. This may well explain the difference between the results reported by Chinn and Sparey – Chinn may have simply got a “good ‘un”!

Of greater relevance in the context of this article was the 1.5 cc Comet 150 based on the Elfin 149. This appears to have been the first of the Australian Elfin 149 replicas, hence its inclusion here. However, it seems to have been manufactured in very small numbers indeed - there are no known confirmed survivors at the time of writing. Indeed, the existence of this model is only known authoritatively from comments provided by former James Small employee James Schmul to Harry Bailey.