|

|

The Weston 3.5 cc “Stunt Special” Diesel

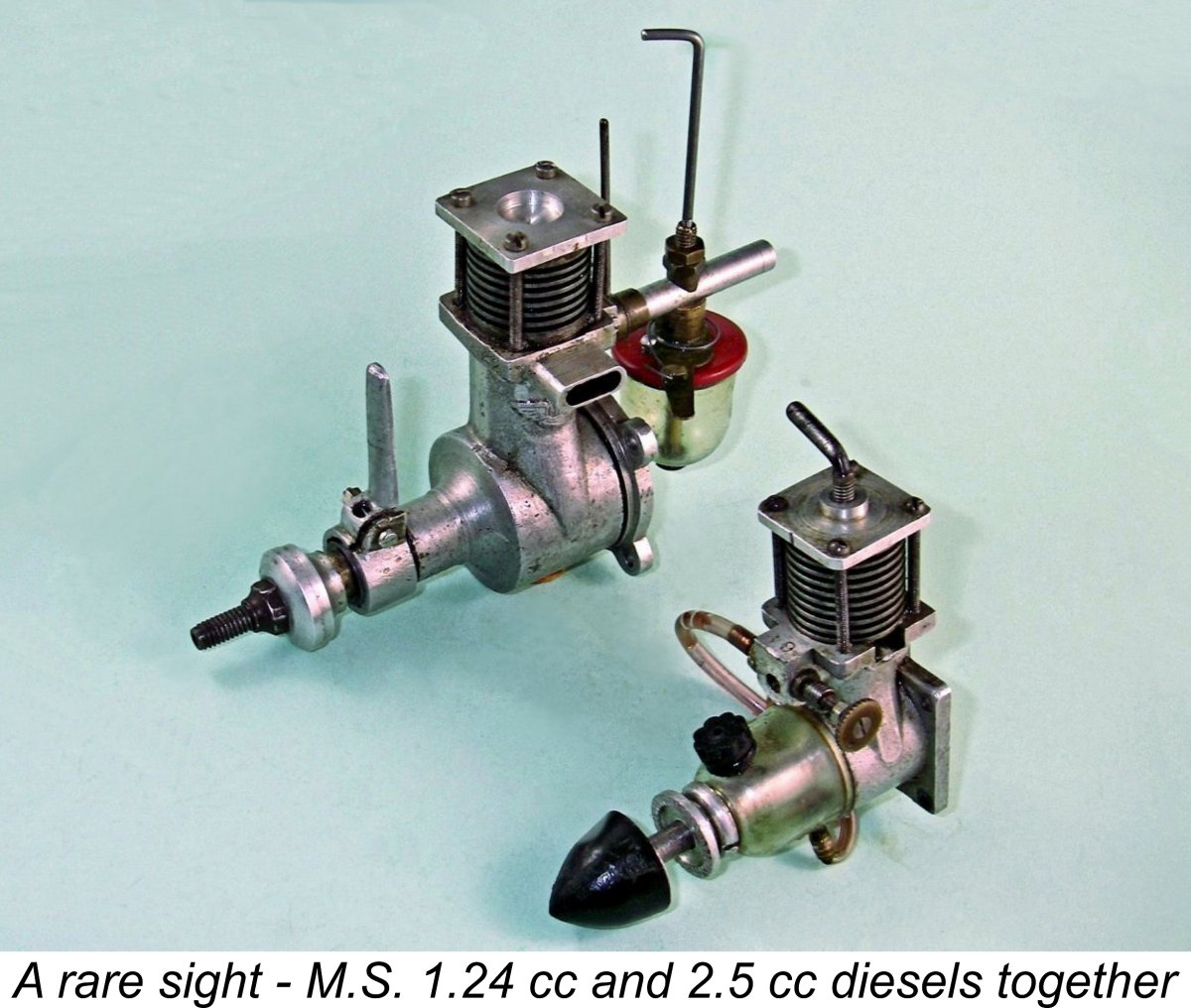

It’s generally been my practise to restrict my writing to engines or engine ranges of which I possess at least one or two examples to serve as review subjects based on my own hands-on experience. Simply repeating what others have said before me without testing their statements fails to meet the fundamental requirement of ensuring historical authoritativeness - those earlier commentators could be wrong (and often are!). Everything needs to be checked against original sources, very much including the engines themselves. Failure to do so can lead to the perpetuation of error through blind repetition - there's been far too much of that in the past! Accordingly, I’d held off writing in any detail about the Weston engines because I didn’t have an example upon which to comment at first hand. Indeed, given the extreme rarity of these engines, I honestly never expected to be able to cover this marque in any detail. I included a comment about the 0.25 cc Weston "A" in my article on the classic micro-diesels, but that was about all that I ever expected to be able to accomplish. All of that changed in 2022 when I was fortunate enough to be offered an unexpected opportunity to acquire a near-pristine example of the Mk. II version of the Weston 3.5 cc "Stunt Special" from a known reputable source. It wasn't cheap, but I was buying information in addition to the engine itself, greatly adding to its value. As I saw it, my good fortune placed me under an obligation to share the engine to the extent possible. May as well get right to it! As usual, I’ll begin by reviewing the background to the appearance of these engines. Background During the early post-WW2 period, interest in power modelling among British enthusiasts was very much on the rise. However, because of severe government restrictions on the importation of many categories of goods, including model engines, suitable powerplants were in short supply. At the same time, ready cash was also in very short supply during the early post-war years as far as the majority of British residents were concerned. At the time in question, a man earning £8 a week before tax would have been viewed as being relatively well off. The cost of the average model engine approached or even exceeded this figure during this period, making the purchase of such an engine a very significant financial decision in the context of the typical British household economy.

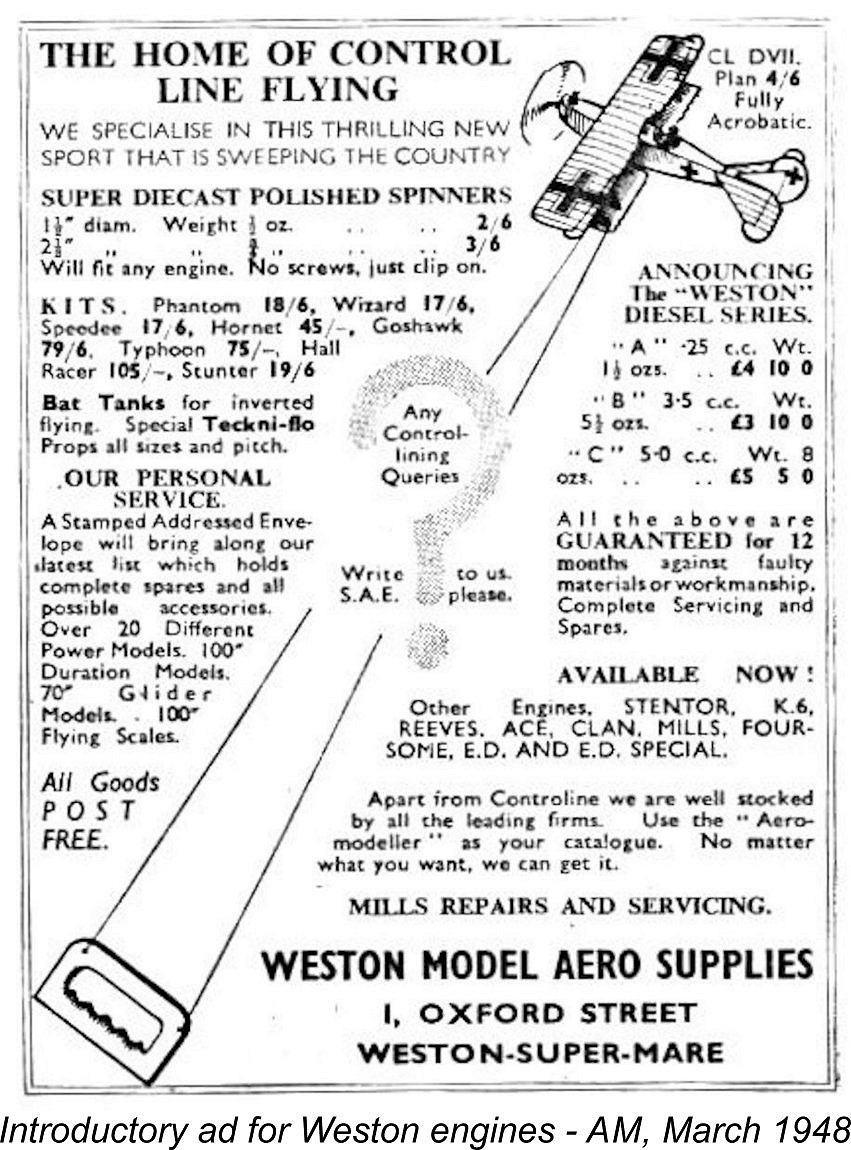

This situation certainly encouraged the design and production efforts of major volume manufacturers such as E.D., International Model Aircraft (FROG) and Mills Brothers. However, it also encouraged a number of small local businesses to make arrangements for the limited production of their own The Weston engines were another example of a small local business becoming involved with marketing their own model engine line. They were manufactured in very small numbers beginning in early 1948 by (or far more probably for) Weston Model Aero Supplies of 1 Oxford Street in Weston-super-Mare, a coastal community located on the south shore of the Bristol Channel in Somerset, England. This firm was actually a retail business specializing in control-line supplies as opposed to a manufacturer per se. The business was owned by one Bill Evans, a leading light in the local control line community who focused his commercial activities accordingly. His business characterised itself as "the home of control line flying". However, some research undertaken by my good friend and colleague Chris Coote of Bristol, England has confirmed that the business actually started as a fishing tackle supply shop, trading as Evans Angling. Given the fact that Bill was in his mid-forties by the late 1940's, it seems very likely that this business had its beginnings during the pre-WW2 years. Bill expanded his shop’s stock by adding aeromodelling items in 1947, when he became fascinated with model engines in general and control line in particular. He was one of the founders of the Weston Control Liners club, and his shop became their headquarters. However, he continued to supply fishing tackle all along.

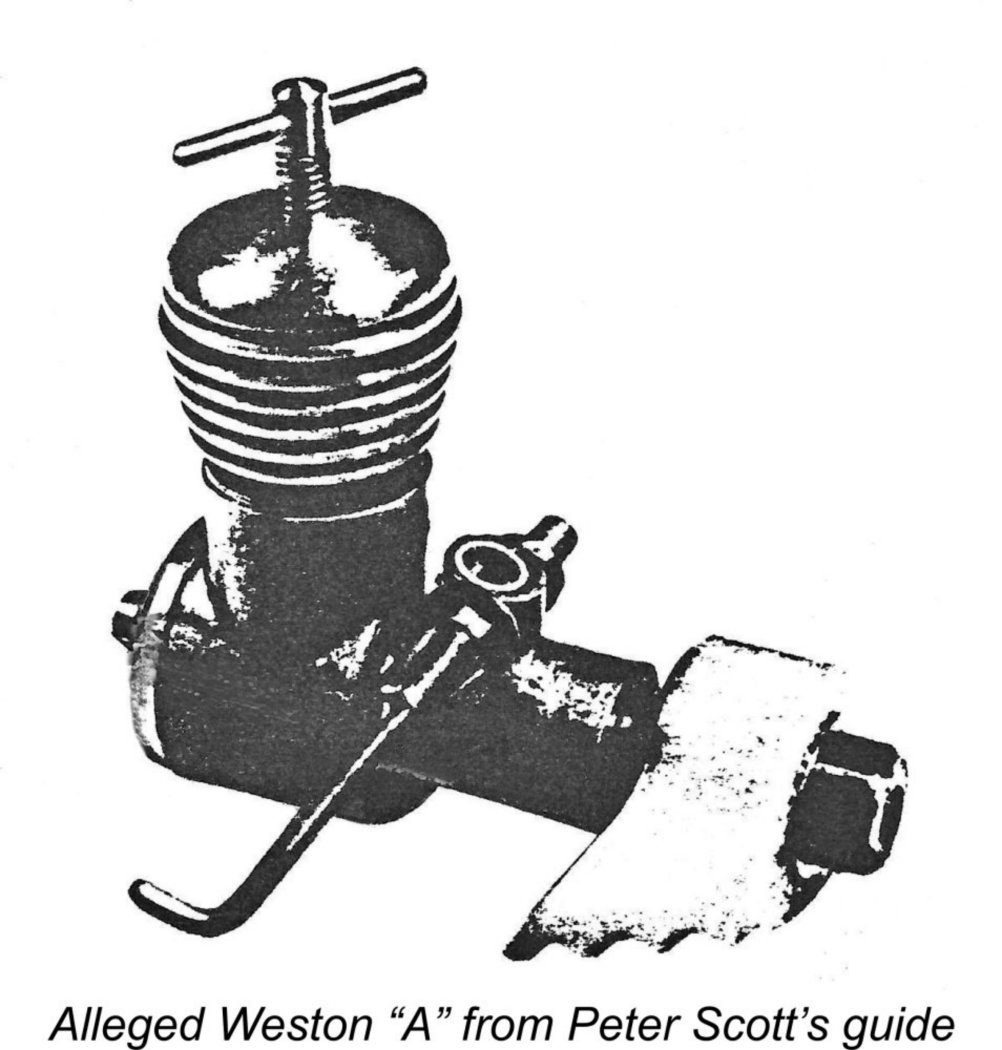

Another possibility which can't be ignored is that the Weston engines were the creation of some local model engineering hobbyist who developed the engines and then persuaded Bill Evans to market them as Weston products. The minimal numbers produced are certainly consistent with this possibility. However, the inexorable passage of time makes it highly unlikely that we'll ever know the truth regarding the origin of the series. The earliest evidence of the Weston model engine range’s market presence comes from its appearance in the initial national advertisement placed by Weston Model Aero Supplies, which appeared in the March 1948 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. This advertisement “announced” the introduction of the "Weston diesel series", seemingly dating its market entry quite closely to early 1948. Unfortunately, the engine manufacturing venture does not appear to have been attended by any noteworthy success. According to Chris Coote, the word among the few surviving members of the local old-time control line fraternity was that very few of the Weston engines made it into the hands of active modellers, while those that did proved to be both fragile and short-lived. Let’s have a look at a few of the models which were offered under the Weston banner. The Weston “A” The smallest engine promoted by Weston under their own name was a little 0.25 cc diesel called the Weston “A”. We know frustratingly little about this engine, which more or less falls into the “legendary” category since although it undoubtedly existed, I’m not presently aware of any authenticated surviving examples! Neither Mike Clanford nor Ted Sladden managed to find an example to illustrate in their respective books, and between them they generally did so if an example was available for photography anywhere. Despite this, the engine’s existence is irrefutably attested both by a series of 1948 advertising appearances over a period of months and by its inclusion in Appendix II of Ron Warring’s early 1949 book “Miniature Aero Motors”. Unfortunately, Warring did not supply any structural details or working dimensions - he only confirmed that the engine was no longer in production as of his publication date. It seems likely that he never had a chance to examine one of these units in the metal.

The attached image of an engine identified as a Weston "A" appeared in a long-forgotten privately-published illustrated guide prepared in 1975 by well-known English collector Peter Scott in connection with his short-lived “International Aero Engine Collector’s Society” (I.A.E.C.S). I was once a member of this Society, hence still having a copy of Peter's guide, from which this image was extracted. If the image is correctly identified, it shows that the Weston “A” was a radially ported diesel engine featuring crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction with a vertical downdraft intake and radial mounting. It actually looked a lot like the later FRV 0.20 cc Kemp Hawk Mk. II of mid 1948. Indeed, it may possibly have influenced that design. The unbraced vertical intake and black crankcase finish are certainly representative of the Weston style as displayed in their later FRV models, of which much more in their place below. However, I have to say that the Of course, I could very easily be wrong! Radial porting was around at that time, as was FRV induction - a forward-thinking designer in early 1948 could certainly have combined the two. Frank Ellis undoubtedly did so in the design of his Aerol Hurricane 2 cc model of November 1947. Moreover, Peter Scott confirmed that he would unquestionably have had a very persuasive basis for identifying the engine as a Weston "A" when preparing his guide back in 1975. However, he informed me in 2021 that he could no longer locate the original evidence after the passage of 46 years. Can any reader resolve this question? If this engine isn't a Weston "A", what is it? Certainly has me beat! Following its inclusion in that original March 1948 advertisement, the Weston “A” continued to be advertised at least through September 1948 at an unchanged price of £4 10s 0d (£4.50). The implication of this is that at least a few examples must have been made during the first half of 1948 - why would Bill Evans continue for at least seven months to advertise a product that didn’t exist?!? To summarize, we know frustratingly little about the Weston “A”. I reckon that we have to leave it there…………… let’s move on to a few models about which we do know a bit more! The Larger Weston Models The Weston “A” was accompanied in the advertisements by a side-port Weston “B” diesel of 3.5 cc displacement and a 5 cc model of unknown specification called the Weston “C”. We already saw that very little of substance is known about the Weston “A”, while the Weston “C” is completely lacking in any documentation whatsoever apart from its appearance in the advertisements and its mention in the data tables of Ron Warring’s previously-cited 1949 book. Even more obscurely, Warring’s book included a reference to a 5 cc diesel called the Weston “D”. The Weston "Aeromodeller" advertisement of August 1948 made reference to a forthcoming 5 cc "twin racing diesel", but no letter designation was used. However, the following month's advertisement in the September 1948 issue specifically included the Weston "D" by that designation, characterizing it as a "twin 5 cc" unit. The clear implication is that it was a twin-cylinder 5 cc diesel.

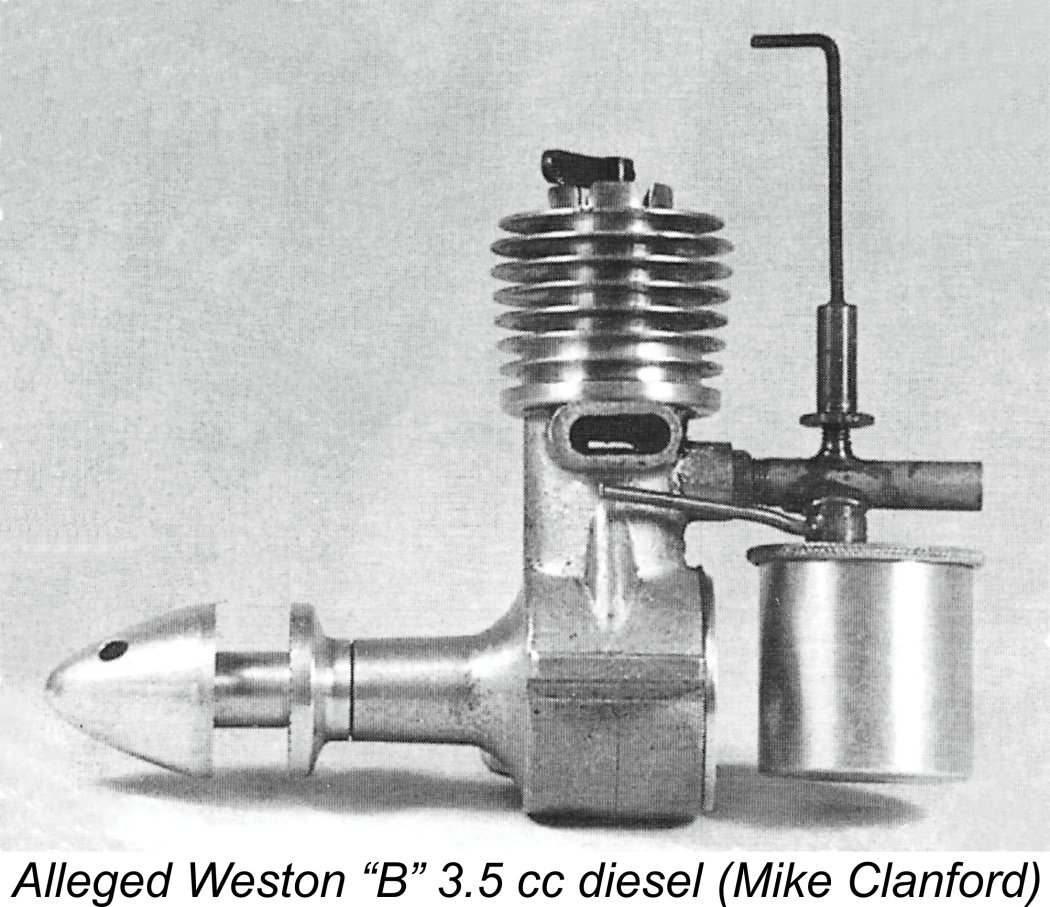

In the event, the only member of the original Weston diesel range to make any kind of a mark was the 3.5 cc "B" model, of which one or two examples reportedly survive today. At least we know what it looked like thanks to the inclusion of the accompanying image in the Weston advertisement for August 1948. The company claimed an output of 0.23 BHP at between 6,000 and 8,000 rpm. According to O.F.W. Fisher’s sometimes unreliable “Collector’s Guide to Model Aero Engines”, only some 6 examples of this engine were produced. Mike Clanford illustrated a purported example of a Weston 3.5 cc side-port model in his well-known but often less than accurate “A-Z” book. However, this engine looks very different from the one in the illustration which appeared in the Weston advertisement for this model. It also bears absolutely no design imprint of the general style of the confirmed Weston 3.5 cc diesels. I would need to see some fairly compelling supporting evidence before I could accept the unit illustrated by Clanford as a genuine Weston offering. He's been wrong before .............

Indeed, at this stage the marketing reach of the Weston engines appears to have extended well beyond Weston-super-Mare. The 3.5 cc Weston model was also advertised by Paramount Model Aviation of London in their June 1948 advertisement. However, this seems to have been the sole London-area listing. Even so, the implication is that whoever was making the Weston engines was not tied down to any exclusive marketing agreement with Bill Evans. Chris Coote was kind enough to contact the late Phil Darke prior to his death in 2022 at the age of 86. Phil had been a teenage member of the Weston Control Liners club during the late 1940's and early 1950's when it was led by Bill Evans. Phil recalled accompanying Bill to local Western Area contests at Lulsgate Bottom Aerodrome (a former RAF fighter base which is now Bristol International Airport). The only Weston engine that Phil ever saw was the 3.5 cc model - he didn’t make clear whether this was the side-port Weston “B” model or the later FRV Weston 3.5 cc “Stunt Special”, of which much more anon. Since it was apparently used in stunt models at those early 1950 meetings, it seems highly likely that it was the later model, which was certainly in existence by early 1949. Phil recalled that the Weston performed poorly by comparison with the Elfin 1.8 powered models then in vogue. Starting seemed to be quite a problem compared to the Elfins, and the engine did not rev up as well. He never saw a 5 cc model and never so much as heard of the miniature 0.25 cc “A” version - hardly surprising in a control-line context. The only really small engine that Phil recalled being around at the time was the little Kalper 0.32 cc diesel which has been reviewed in detail elsewhere. The manufacture of the side-port 3.5 cc Weston “B” was evidently confined to the year 1948, with perhaps as few as 6 examples being completed if Fisher is to be believed. As of early 1949 a significantly amended crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) 3.5 cc model called the Weston "Stunt Special" was being touted by the company, with no further mention of the Weston “A”, “B”, “C” or "D". From this point onwards, I’ll confine my attention to that model. The Weston 3.5 cc “Stunt Special” Mk. I on Contemporary Test

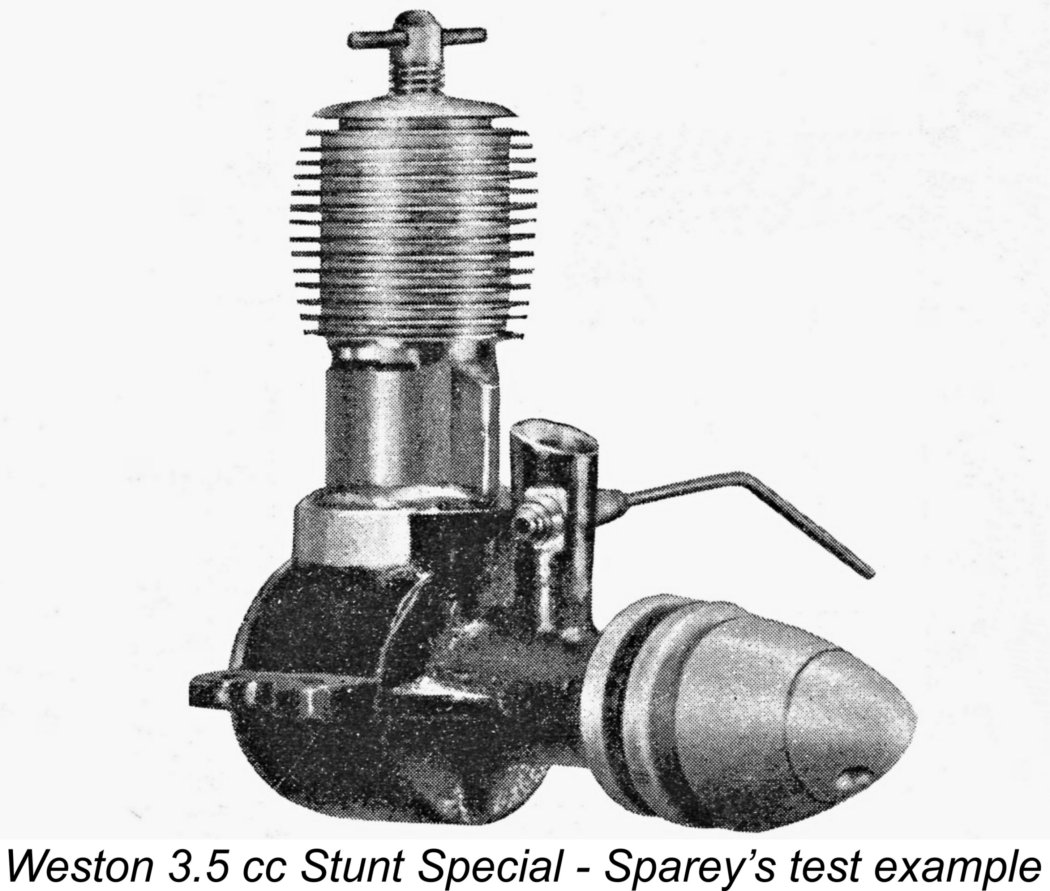

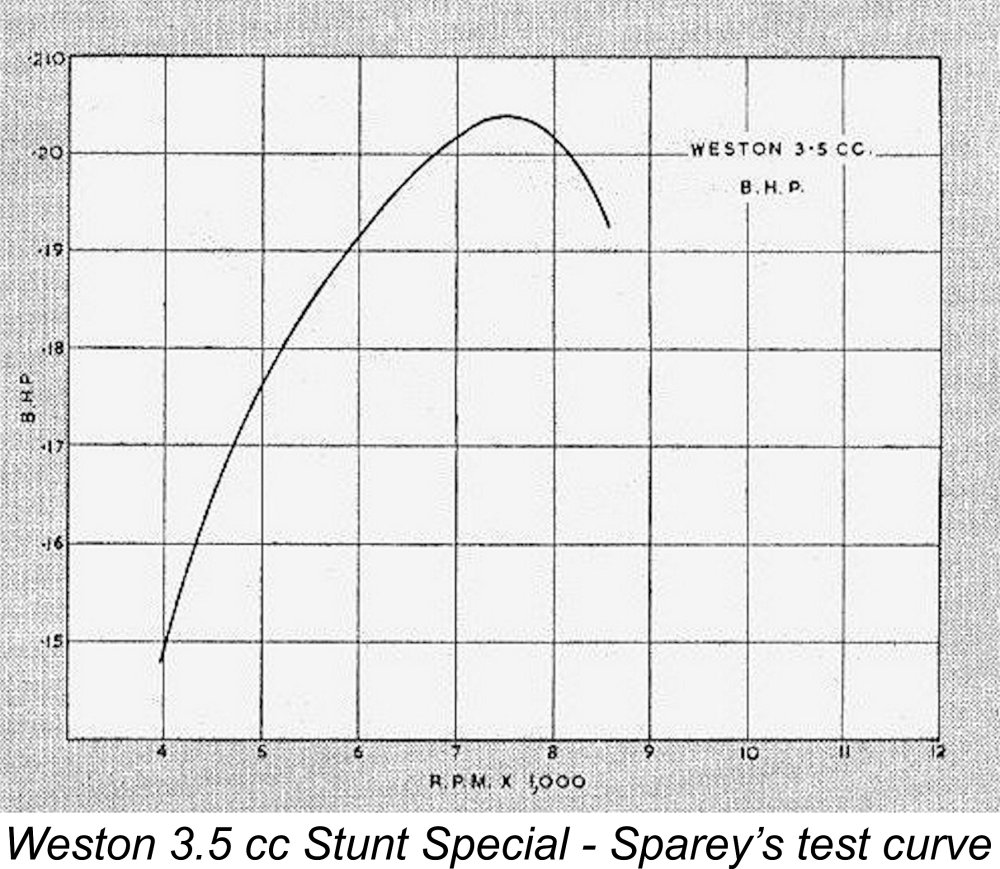

We know a fair bit about the Mk. I version of the Weston 3.5 cc "Stunt Special" because it was actually the subject of a published test by Lawrence H. Sparey which appeared in the June 1949 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Unfortunately, the Weston came in for an unusually high level of criticism in Sparey's test report. Sparey commented that the engine started well when loaded for its best performance, also running "well and steadily" in its Another criticism levelled by Sparey was the strength of the rather vulnerable-looking carburettor assembly. It's hard to disagree with this criticism - the very long slender needle looks extremely vulnerable, while the intake tube is both very thin and poorly supported, looking as if a typical crash impact could cause it to fracture or distort. Sparey actually claimed that the pressure of the spraybar installation nut was sufficient to distort the very thin-walled intake tube. I’ve chosen not to disturb the spraybar on my example to find out!

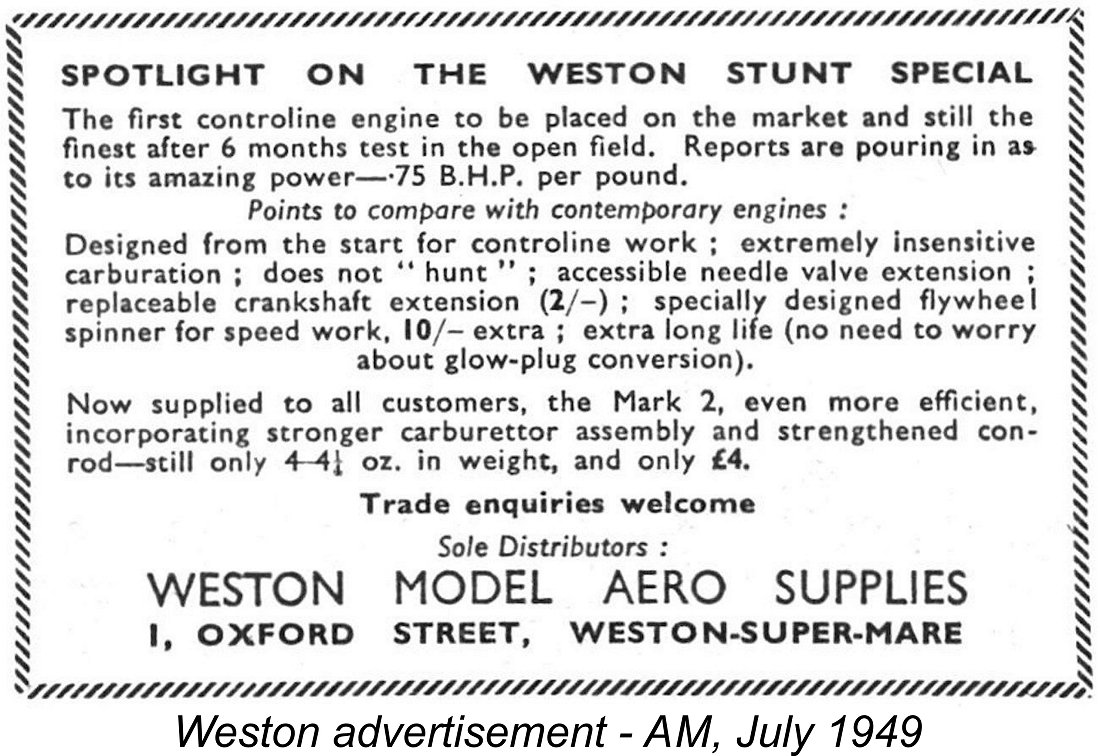

Unfortunately, the engine expired towards the end of Sparey’s test, apparently emitting an “ominous clanking from within”. Overall, the impression gained from reading Sparey’s test report was that of an under-designed engine which progressively fell apart during the test! Scarcely an inducement for anyone to consider purchasing an example! Sparey speculated that the test-ending issue may have been a conrod bearing failure, but inexplicably he didn’t remove the backplate to confirm or refute this. In my opinion, the reported symptoms are far better explained by the loosening of the screw which secured the gudgeon pin carrier to the inside of the composite piston. This was a fairly common failure with engines constructed in this manner, although it’s easily rectified by simply re-tightening the screw while holding the piston (as opposed to using the con-rod as the means of preventing the piston from turning - that guarantees a twisted rod!). Although a conrod failure as postulated by Sparey almost certainly wasn’t the cause of his difficulties, his widely-read report doubtless created an impression among his readers that the "Stunt Special" was significantly under-designed, in particular suffering from a weak rod, a flimsy intake structure and a poorly-designed needle valve. His comments appear to have led It's perhaps significant to note that Weston Model Aero Supplies identified themselves as the "sole distributors" of the Stunt Special as opposed to its manufacturers. This is consistent with the previously-stated view that the engines were almost certainly manufactured by someone other than Weston. Despite these efforts, the damage was done - Sparey’s report undoubtedly sounded the death knell for any marketing prospects which the Weston 3.5 cc “Stunt Special” may have had. The engine quickly sank without trace, with no more being heard of it - the previously-reproduced July 1949 advertisement was the final advertisement in which the engine was mentioned. Reportedly only about 20 examples ended up being constructed. Bill Evans appears to have abandoned the model engine manufacturing field entirely at this point. Indeed, the August 1949 advertisement by Weston Model Aero Supplies was the company's final national placement that Gordon Beeby could find. The Weston "Stunt Special" was not mentioned in that final advertisement. The cessation of national advertising by no means indicated that Weston Model Aero Supplies had gone out of business at this time. It was simply that Bill Evans had found that the return on his national advertising campaign in terms of mail orders or trade inquiries was insufficient to justify the continued expenditure. He actually continued to operate his business as a combined fishing tackle and model supply shop for many years thereafter. However, as time went along he progressively lost interest in the club that he had been instrumental in founding, eventually stopping flying himself in the early 1960’s and subsequently winding down his inventory of model goods in favour of a continued emphasis on fishing tackle. Chris Coote visited Bill's shop in 1976. Bill hadn't completely abandoned the model trade at this point - some items such as kits and balsa wood were still on display. Chris visited again in the mid-1980's, by which time Bill was in his mid-80's. Remarkably, he was still carrying on his fishing tackle business, although there were no longer any modelling items in evidence. A new model shop which was part of the RCS (Radio Control Supply) chain had opened only 300 yards away, and this of course catered to the “modern” modelling market in which Bill evidently had no interest in competing. In summary, Bill Evans was seriously into the model supply business from 1947 through to around 1965, continuing thereafter at a far lower level of intensity until the early 1980’s. His involvement in the model trade thus spanned a period of some 35 years. The Weston 3.5 cc "Stunt Special" - Description

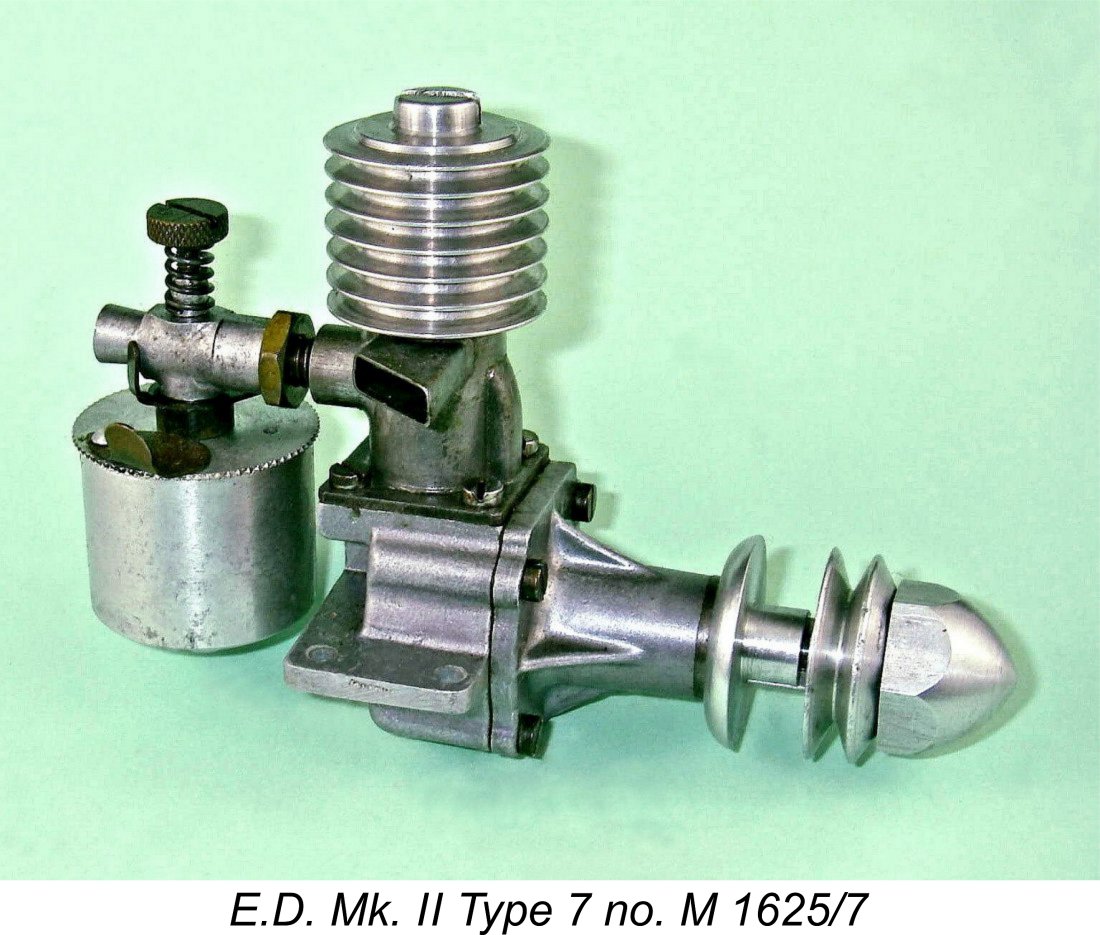

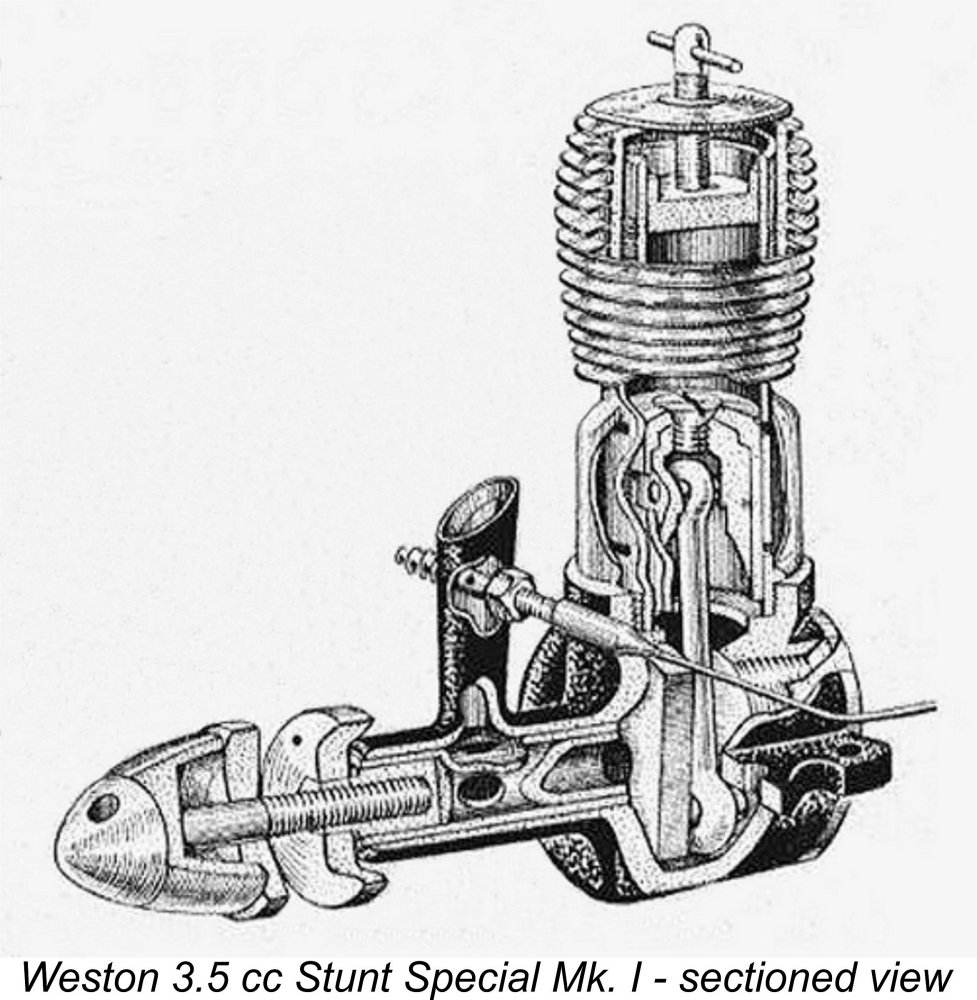

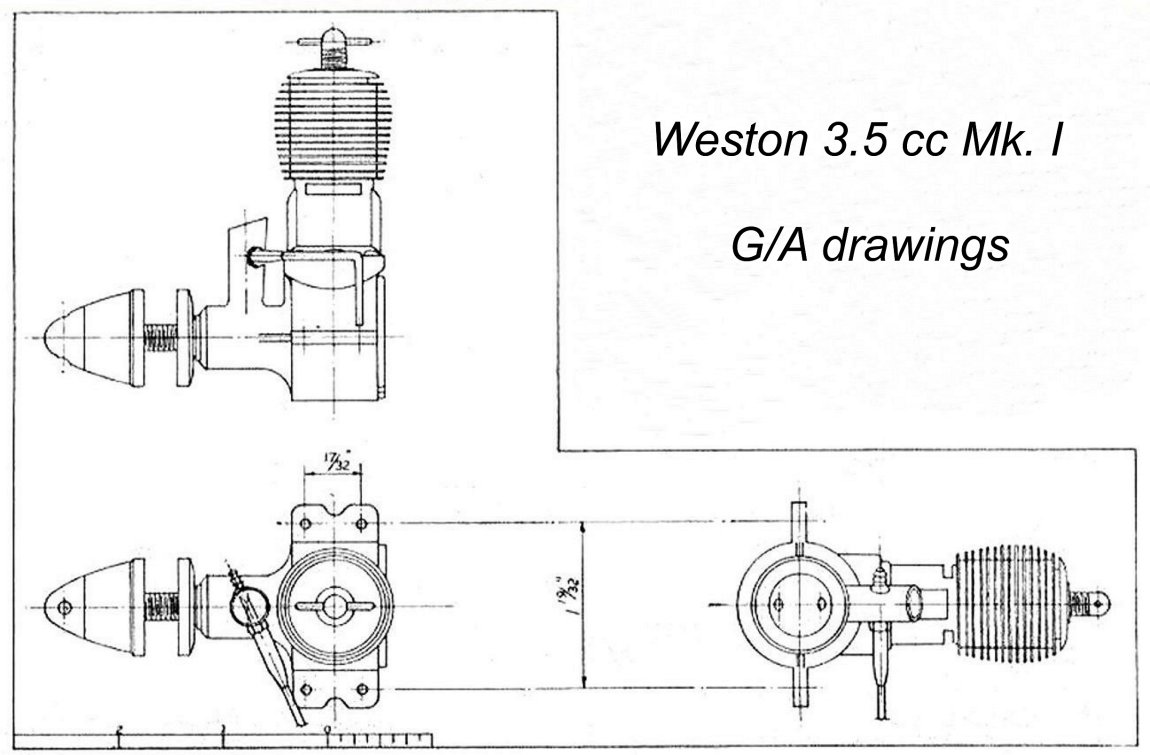

Reference to the accompanying sectioned view extracted from Sparey’s test report may help to clarify certain aspects of the design. The accompanying G/A drawings from Sparey's report may provide further clarification regarding the engine's construction. The Weston "Stunt Special" was a lightweight 3.5 cc plain bearing diesel featuring crankshaft front rotary valve induction. In support of its proclaimed purpose of serving as a stunt engine, it showed clear evidence of a sincere attempt to minimise its weight. From this point of view, it would also have made a very practical free flight powerplant. As mentioned earlier, the Weston "Stunt Special" appeared in two successive versions. The example which I was fortunate enough to acquire appears to be a Mk. II model. Both variants featured bore and stroke dimensions The engine was built up around a gravity die-cast crankcase which included both the main bearing housing and the intake venturi tube in unit. This casting was given a very durable black crackle paint finish. The company’s “Winged W” emblem appeared on the left side of the case.

The heat-treated screw-in steel cylinder was machined from a billet of hexagonal bar stock which measured ¾ inch across the flats. The cylinder installation flange below the exhaust ports retained the original hexagon, greatly facilitating the tightening of the cylinder. A gasket was included beneath the hexagonal location flange.

Considering the engine's displacement of 3.5 cc, the two bypass channels are notably small in size - the rear view included below highlights this observation. By eyeball, the combined area of the two channels appears to be less than the area of the single bypass featured on the 2 cc E.D. Comp Special, for example. Viewing the matter objectively, I would expect the "Stunt Special" to be bypass-limited in performance terms. Every example of the engine that I’ve ever seen either in the metal or in photographs has had its cylinder installed so as to locate the exhaust ports to right and left, with the bypass passages being located fore and aft. This was clearly the design orientation. It was evidently achieved through the use of cylinder installation gaskets having different thicknesses, thus serving as shims. It was my reluctance to disturb the orientation of my example that led to my decision not to fully dismantle it for inspection. The piston was a composite component consisting of an external thin-walled Meehanite cast iron working shell with a light alloy internal carrier to accommodate the gudgeon (wrist) pin. In my example at least, the piston/cylinder fit is beyond reproach, with outstanding compression. This form of composite piston construction resulted in the working surface of the piston being uninterrupted by the outer ends of the gudgeon pin bearings. The carrier was secured within the working piston by a slot-head countersunk screw passing through the center of the piston crown. In my view, it was almost certainly this screw coming loose that caused the premature termination of Sparey’s testing - it's really unfortunate that he didn't bother to check.

The crankshaft featured a rather unusual crankweb having a semi-rectangular plan view which expands slightly in width from the crankpin end to the opposite end. A small degree of counterbalance was thus provided, although I would have been happier to see a somewhat heavier crankweb having a more significant counterbalance. Once again, the designer seems to have been driven by the goal of achieving minimum weight.

The induction port in the shaft was a simple round hole which engaged with the base of a vertical tubular intake. This intake was cast integrally with the crankcase and main bearing housing. It was completely unsupported by any form of bracing, adding credibility to Sparey’s comment that the engine was rather more lightly constructed than the requirements of structural integrity might suggest.

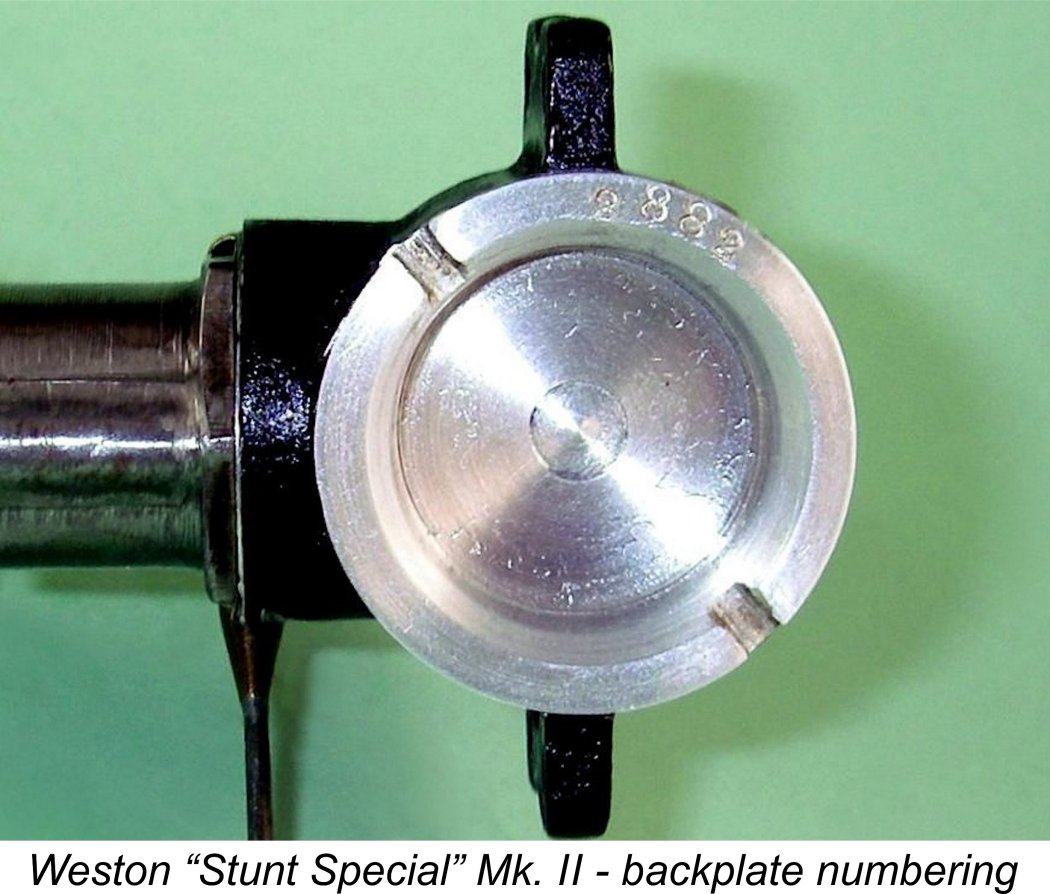

The Mk. II version of the "Stunt Special" had its needle valve angled even more extremely at a full 45 degrees. This was presumably done in order to decrease the vulnerability of the needle valve to crash damage. In addition, the wall thickness of the induction tube was increased slightly, with a somewhat more prominent bell-mouth being featured. This too was clearly aimed at improving crash resistance. The revised angle of the needle valve was such that the fuel nipple was a separate piece of brass tubing which was soldered at right angles to the supply end of the spraybar and directed towards the rear of the engine. This permitted a very neat and direct alignment of the fuel supply tube alongside the engine, also keeping the delivery end of The engine was completed by a screw-in alloy backplate which was an outstanding fit in its installation thread. A thin fibre gasket was used to create a seal. The backplate on my Mk. II example bears the stamped-on number 2882 on the rim. This may be a serial number, although this is by no means certain. The Mk. I example illustrated in Ted Sladden’s book “British Model Aero Engines - 1946 - 2011” appears to display the seemingly unrelated number B 2121x (the last digit indecipherable) on the right-hand side of the upper crankcase. It’s impossible to draw any valid conclusions regarding serial numbers from these very limited data. My overall comment may come as a bit of a surprise - it certainly did to me! I have to say that far from being the corner-cutting mechanical “house of cards” suggested by Sparey, the The main valid points of criticism are undoubtedly the long vulnerable needle valve and the thin-walled unbraced intake venturi tube. Even on the beefed-up Mk. II version, this looks a bit on the flimsy side. I also reckon that a heavier crankweb with a bit more counterbalance wouldn't have hurt. That aside, this is undoubtedly a quality product - a finding which I was frankly not expecting based on Sparey’s long-ago assessment. I actually gained the impression that the working components of the engine were well up to their designated tasks. This being the case, I had no hesitation in putting the "Stunt Special" onto the test stand to see how it performed. The Weston 3.5 cc “Stunt Special” Re-Tested My example of the Mk. II "Stunt Special" appeared to have done some running but displayed no evidence in the form of witness marks that it had ever been mounted in a model. By feel, it seemed to be well run in, hence being all ready for testing. I felt pretty confident that Sparey’s test results provided at least a reasonable ball-park expectation regarding the engine’s performance. This being the case, I elected to begin with a 10x6 APC prop which would provide plenty of flywheel to facilitate the initial start. I also decided to test the engine on a nitrated castor-based fuel. The manufacturers recommended a 9x6 Tru-Flo prop for stunt, so I was confident that the engine would by no means over-speed on the 10x6.

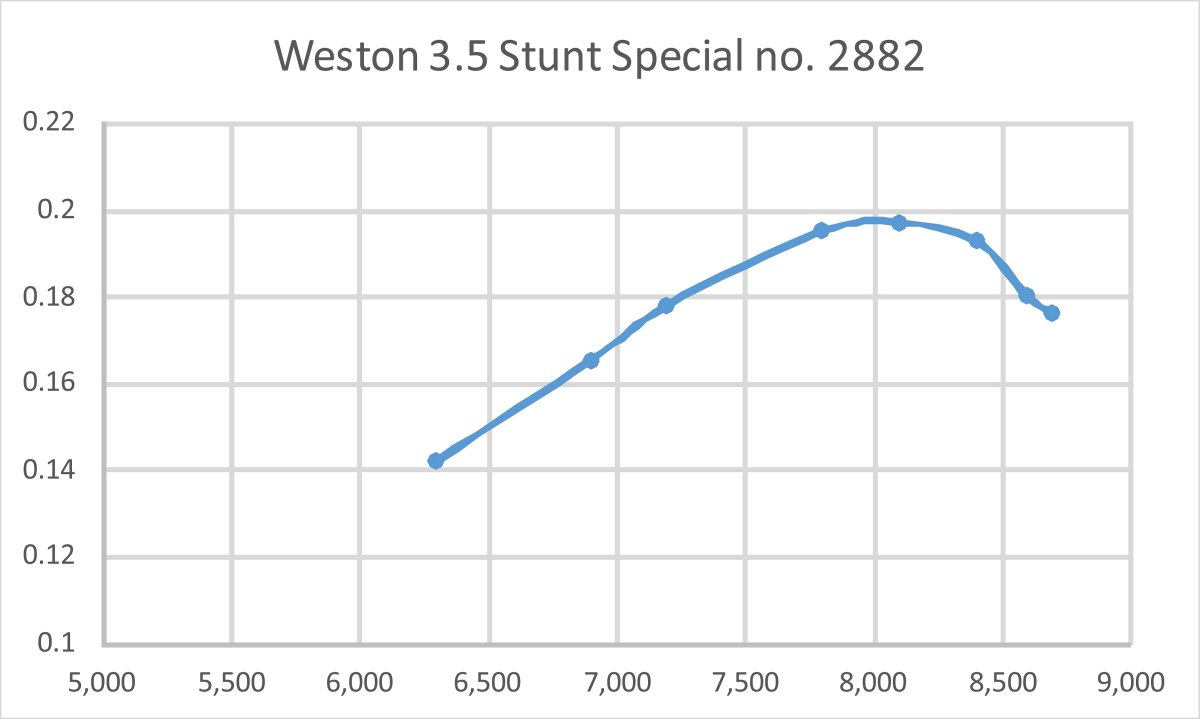

By feel, the engine seemed to me to require a slightly higher compression setting than that with which it had been received. Accordingly, I added a ¼ turn, after which things felt right to me. I then set the needle by choking the engine on an empty fuel line and observing the movement of fuel in the line when the engine was turned over. It turned out that around 8 turns of the needle appeared to my experienced eye to be a good rich-mixture setting at which to start. Having set the controls, I gave the engine a couple of choked turns and then injected a small “dry prime” (administered with the exhaust ports closed). Then it was a case of flexing the flicking finger and getting down to it! Thankfully, I didn’t have to work too hard - the engine actually The Weston continued to demonstrate outstanding starting qualities throughout the test, regardless of the prop being tested. One- or two-flick starts were the norm. Once set for best running when fully warmed up, the Stunt Special proved to be an outstandingly smooth runner. I had none of the problems reported by Sparey with respect to any difficulty in establishing a good needle setting, nor was there any tendecy to "hunt" or sag. Suction appeared to be more than adequate. Some vibration was certainly present, but no more than a really solid mounting would accommodate. I didn't consider it to be excessive or unmanageable. The needle showed no symptoms of being excessively stressed by vibration as reported by Sparey. Both controls held their settings perfectly. It turned out that my selection of a 10x6 prop had been a pretty good guess! The engine turned this prop at a smooth and steady 8,100 rpm, which turned out to be right around this example’s peak. I tried a few smaller loads, finding that although the engine did turn these at slightly higher speeds it appeared to be reluctant to run much beyond 8,500 rpm. It was certainly at its best swinging a more substantial prop. The following data tell the story.

As can be seen, my example of the Weston 3.5 cc "Stunt Special" Mk. II seems to have developed a peak output of around 0.197 BHP @ 8,100 rpm - fractionally less power than reported by Sparey, but at a slightly higher speed. I’d say that the recommended 9x6 prop might have under-propped it a little, but not by much. Not perhaps a stellar performance by mid-1949 standards, especially given the impending appearances of the AMCO 3.5 PB and E.D. 3.46 cc Mk. IV Hunter designs, both of which exceeded this level of performance by a substantial margin. However, the Weston was certainly a lightweight and very useable engine which would have done a more than acceptable job of flying a sport control line or free flight model. It was also constructed to a far higher standard than Sparey’s report had led me to anticipate. As a final note, my Aussie mate Gordon Beeby drew my attention to an "engine starting contest" which was held on September 9th, 1950 by the Southampton M.A.C. This event was reported in the "Club News" features in the December 1950 issues of both "Model Aircraft" and "Aeromodeller". There were 9 entries, the winner being club member Peter Cock, the 1948 Gold Trophy winner. Interestingly enough, Peter used a Weston 3.5 cc diesel (almost certainly a "Stunt Special") to win this contest. The "Model Aircraft" report stated that filling the tank was part of the timed starting procedure and that Peter Cock's Weston only needed one flick to start once this was done. It seems that my example's excellent handling was typical of this engine! Conclusion

In reality, and setting aside that indisputably vulnerable intake structure and needle valve, the Weston surprised me by turning out to be a very user-friendly and perfectly sound model diesel which would have served its owners well provided they treated it with respect and kept it out of the ground. I’d have no hesitation in running my example again should the occasion arise. I hope that I’ve done something to rehabilitate the reputation of an engine which has hitherto been regarded as a bit of an inconsequential failure. In reality, this was a sincere attempt by its unknown maker to produce a lightweight 3.5 cc diesel having a reasonable performance which would provide some good service to its owners! Its design shortcomings were far less serious than Sparey implied and take nothing away from its value as a useable engine and a very rare collectible. I am indeed fortunate to have had the opportunity to experience its qualities at first hand! _________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published January 2023 |

||

| |

Here we’ll share a look at a near-mythical early post-WW2 product of a little-known British company from Weston-super-Mare in Somerset, England. I’ll be summarizing what little is known about the extremely elusive Weston diesels, also presenting a test report on a rare surviving example.

Here we’ll share a look at a near-mythical early post-WW2 product of a little-known British company from Weston-super-Mare in Somerset, England. I’ll be summarizing what little is known about the extremely elusive Weston diesels, also presenting a test report on a rare surviving example. Nevertheless, people were willing to save up and make such purchases due in large part to the novelty value and perhaps the “exclusivity” of these little units. To a certain degree, the possession of an engine was doubtless seen as something of a status symbol among British modellers of the period. This created a British marketplace in which pretty much any model engine that would start and run reasonably well most of the time was assured of a buyer.

Nevertheless, people were willing to save up and make such purchases due in large part to the novelty value and perhaps the “exclusivity” of these little units. To a certain degree, the possession of an engine was doubtless seen as something of a status symbol among British modellers of the period. This created a British marketplace in which pretty much any model engine that would start and run reasonably well most of the time was assured of a buyer. “house brand” model engines intended for sale mainly to the local market in their vicinity. Examples of this abound, including the Comet,

“house brand” model engines intended for sale mainly to the local market in their vicinity. Examples of this abound, including the Comet,

Both the advertisements and Warring’s book reference agree that the Weston "A" had a displacement of 0.25 cc and weighed 1¼ ounces (35.4 gm). However, neither bore nor stroke dimensions were given. Figures of 0.250 in. (6.35 mm) and 0.3125 in. (7.94 mm) would fit the bill nicely, but they’re no more than an educated guess.

Both the advertisements and Warring’s book reference agree that the Weston "A" had a displacement of 0.25 cc and weighed 1¼ ounces (35.4 gm). However, neither bore nor stroke dimensions were given. Figures of 0.250 in. (6.35 mm) and 0.3125 in. (7.94 mm) would fit the bill nicely, but they’re no more than an educated guess.

My Aussie friend and colleague Gordon Beeby very kindly trolled the pages of his "Aeromodeller" magazine collection to find advertisements relating to the Weston "Stunt Special". The earliest advertisement for the engine that he found appeared in the magazine's March 1949 issue. Allowing for Editorial lead time, this seems to confirm that the engine first became available in January 1949.

My Aussie friend and colleague Gordon Beeby very kindly trolled the pages of his "Aeromodeller" magazine collection to find advertisements relating to the Weston "Stunt Special". The earliest advertisement for the engine that he found appeared in the magazine's March 1949 issue. Allowing for Editorial lead time, this seems to confirm that the engine first became available in January 1949.  optimum speed range of 6,000 - 7,000 rpm. However, he stated that it was inclined to run erratically at speeds outside this range. He put this down to the carburettor design. To make matters worse, the needle itself apparently failed during the test due to the effects of vibration.

optimum speed range of 6,000 - 7,000 rpm. However, he stated that it was inclined to run erratically at speeds outside this range. He put this down to the carburettor design. To make matters worse, the needle itself apparently failed during the test due to the effects of vibration.  Sparey reported a peak output of 0.204 BHP @ 7,500 rpm - somewhat below the manufacturer’s previously-cited claim for the side-port Weston ”B”. Nonetheless, Sparey considered this to be an excellent performance from an engine weighing only 4½ ounces (128 gm).

Sparey reported a peak output of 0.204 BHP @ 7,500 rpm - somewhat below the manufacturer’s previously-cited claim for the side-port Weston ”B”. Nonetheless, Sparey considered this to be an excellent performance from an engine weighing only 4½ ounces (128 gm).

Before beginning this section of the article, I should note that I was unwilling to disturb my Mk. II example of the engine beyond the removal of the backplate. The following description is therefore based upon my own external examination together with the structural details included in Sparey’s test report and Warring’s data tables.

Before beginning this section of the article, I should note that I was unwilling to disturb my Mk. II example of the engine beyond the removal of the backplate. The following description is therefore based upon my own external examination together with the structural details included in Sparey’s test report and Warring’s data tables.

Cylinder porting consisted of two generously-sized rectangular exhaust ports with two smaller rectangular transfer ports cut through the lower cylinder wall between them - the familiar arrangement made famous by Cox, although it had been used by a number of other manufacturers before Cox adopted it. The bypass passages which fed these ports took the form of stamped sheet metal channels which were very neatly soldered onto the outer wall of the lower cylinder. These channels were supplied at their lower end with fresh mixture from the crankcase through two similar rectangular ports cut through the lower cylinder wall.

Cylinder porting consisted of two generously-sized rectangular exhaust ports with two smaller rectangular transfer ports cut through the lower cylinder wall between them - the familiar arrangement made famous by Cox, although it had been used by a number of other manufacturers before Cox adopted it. The bypass passages which fed these ports took the form of stamped sheet metal channels which were very neatly soldered onto the outer wall of the lower cylinder. These channels were supplied at their lower end with fresh mixture from the crankcase through two similar rectangular ports cut through the lower cylinder wall. The piston drove the one-piece steel crankshaft through a relatively long con-rod of typical British turned “dog bone” pattern. In his previously-cited early 1949 book, Ron Warring identified the rod material of the Mk. I variant as

The piston drove the one-piece steel crankshaft through a relatively long con-rod of typical British turned “dog bone” pattern. In his previously-cited early 1949 book, Ron Warring identified the rod material of the Mk. I variant as  The main journal ran in a well-fitted Meehanite bushing, another quality touch which seems to promise a long working life. At the front, the shaft terminated in a very short section of reduced diameter which featured two opposing flats to lock the appropriately-formed alloy prop driver to the shaft. The front section of the shaft was hollow, being tapped ¼-26 BSC to accommodate a composite streamlined spinner bolt machined from light alloy. Once again, the designer has reduced weight to the extent possible while also protecting the shaft to some degree from potential crash damage.

The main journal ran in a well-fitted Meehanite bushing, another quality touch which seems to promise a long working life. At the front, the shaft terminated in a very short section of reduced diameter which featured two opposing flats to lock the appropriately-formed alloy prop driver to the shaft. The front section of the shaft was hollow, being tapped ¼-26 BSC to accommodate a composite streamlined spinner bolt machined from light alloy. Once again, the designer has reduced weight to the extent possible while also protecting the shaft to some degree from potential crash damage.  On the original Mk. I variant of the engine as tested by Sparey, a conventional straight spraybar was used with the very long needle angled to the rear at some 25 degrees, placing the control handle well aft of the prop disc. A conventional brass split thimble was used to provide needle tension. The orientation of the needle to the left was clearly intended to be compatible with the probable sidewinder mounting of the engine in a control-line model.

On the original Mk. I variant of the engine as tested by Sparey, a conventional straight spraybar was used with the very long needle angled to the rear at some 25 degrees, placing the control handle well aft of the prop disc. A conventional brass split thimble was used to provide needle tension. The orientation of the needle to the left was clearly intended to be compatible with the probable sidewinder mounting of the engine in a control-line model.

A vital element of preparation when testing an engine having a painted crankcase is the provision of some means of protecting the paint finish from the pressure imposed by the test stand upon the engine bearers. I wrapped the bearers in two small sheets of fibre gasket material in order to prevent metal-to-paint contact. As events were to prove, this measure was completely effective.

A vital element of preparation when testing an engine having a painted crankcase is the provision of some means of protecting the paint finish from the pressure imposed by the test stand upon the engine bearers. I wrapped the bearers in two small sheets of fibre gasket material in order to prevent metal-to-paint contact. As events were to prove, this measure was completely effective.

My major conclusion following the completion of this review is that Sparey’s test report created an undeservedly negative impression of the Weston 3.5 cc “Stunt Special”. Unfortunately, that impression has lasted down to this day - prior to my direct encounter with an example, I myself had viewed this engine as an under-designed and overly fragile failure.

My major conclusion following the completion of this review is that Sparey’s test report created an undeservedly negative impression of the Weston 3.5 cc “Stunt Special”. Unfortunately, that impression has lasted down to this day - prior to my direct encounter with an example, I myself had viewed this engine as an under-designed and overly fragile failure.