|

|

The E.D. Pep - Forgettable Fiasco or Successful Failure?

In many ways, the Pep was a product which stood well apart from the rest of the contemporary E.D. model engine range. Among other factors, the company's approach to its design and construction was unique among their various products. Moreover, it was their sole offering to take an American My original article on the Pep was published in June 2013 on the late Ron Chernich’s “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. I’m re-publishing it here solely to prevent its loss as Ron’s now-frozen and administratively-inaccessible site steadily deteriorates due to lack of any opportunity to maintain it. I’ve also taken advantage of the opportunity to revise certain aspects of the text to reflect additional information which has since come to light. Before getting started on my main subject, it's both my duty and my very sincere pleasure to acknowledge the unfailing assistance and encouragement which have been accorded to me by my valued friend and colleague Kevin Richards. It would be quite impossible to write with any authority about any aspect I'm equally indebted to the late former E.D. chief engineer Gordon Cornell for generously sharing his recollections of his time at E.D. with me. Such a first-hand viewpoint is invaluable to any researcher, and Gordon's input did much to clarify matters which might otherwise have remained forever obscure. I must also recognize the contribution of the late David Owen in sharing a number of images and serial numbers with me. The preservation of model engine history is a shared responsibility, a fact which David invariably recognized and acted upon. I'm fortunate indeed to have had such assistance always at hand. Now, in order to understand the history of the Pep, it's essential to grasp the context within which it was produced. So here we go with a bit of previous history! Background

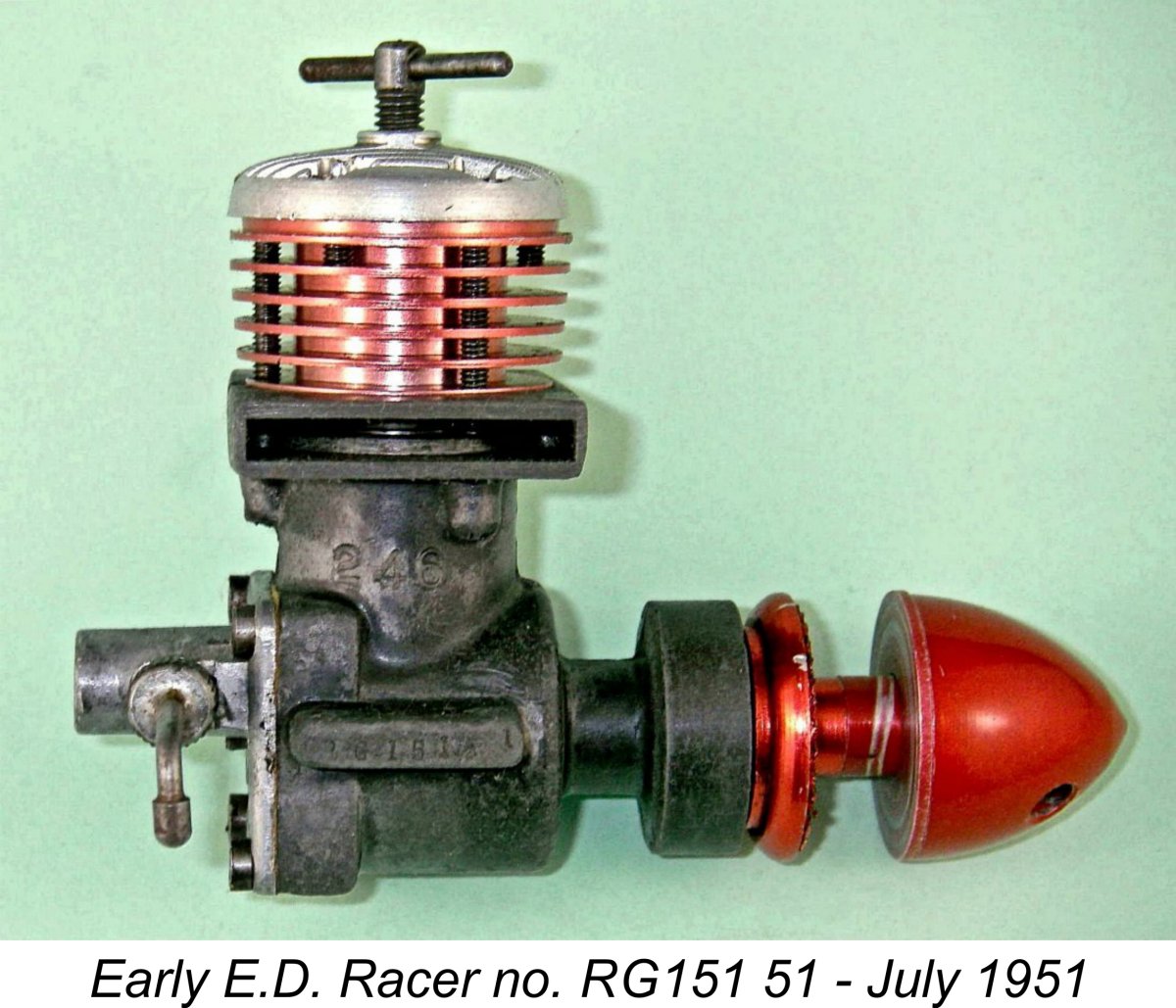

The company maintained its position throughout the 1950's despite a number of setbacks which are covered in my separate history of the venture. New and improved model engines continued to appear regularly throughout the first half of the decade before E.D. entered into a two-year period of reappraisal In May 1958, E.D. announced their first all-new model for some time, the 1.46 cc reed-valve Fury. This was released with high expectations but proved to be uncompetitive both in terms of price and performance. It was by no means the anticipated success, hence doing nothing to bolster E.D.'s somewhat flagging fortunes. The design of the E.D. engines from the late 1940's through until early 1958 had been entrusted Miles' name continued to be openly associated with the E.D. model engines until some point in 1953, when some personal problems forced him to distance himself from the company, at least publicly. Even then, he continued to work for E.D. behind the scenes, also producing a number of engines under his own name at the same time. One of these units, the 5 cc Miles Special, was marketed by E.D. in both diesel and glow-plug configurations. Motivation for the Pep's Development

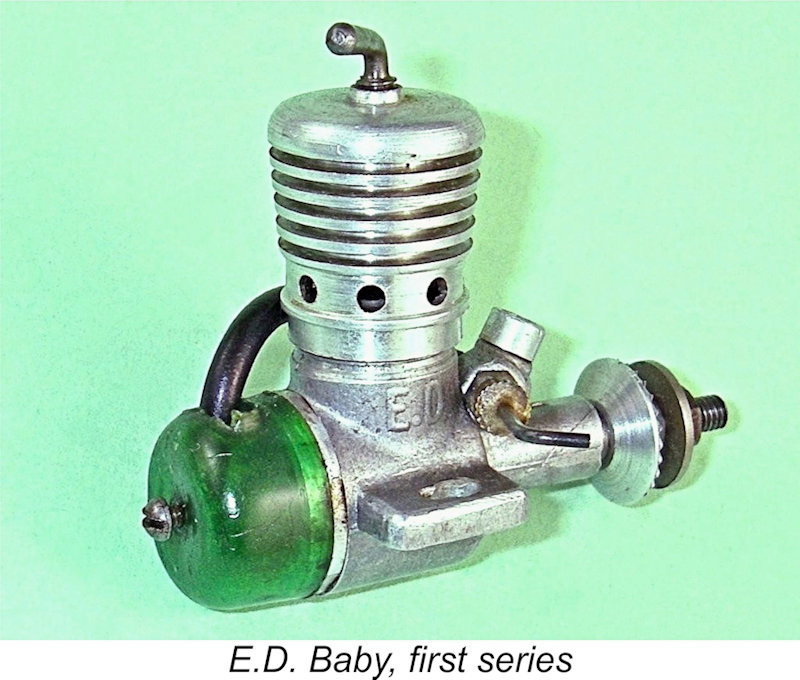

An example from the early 1950's was the ½ cc "revolution" of 1951/52, which was triggered by the late 1950 release of Allbon Engineering's deservedly famous 0.55 cc Dart model. The immediate and overwhelming success of the Dart prompted the development of competing ½ cc models by no fewer than three other competing British manufacturers - Aerol Engineering (Elfin), International Model Aircraft (FROG) and of course E.D. with their 0.46 cc “Baby”. The Elfin 50 fell by the wayside quite early on as a result of production difficulties, but the others stayed the course for some time.

However, the little ½ cc powerplants undeniably had their limitations. They were not notable for their handling qualities, being somewhat "fiddly" to start and adjust and also being far easier From a manufacturers' standpoint too, the tiddlers had their drawbacks. Although less material was used in their construction, the cost of materials was insignificant when compared with the cost of manufacture. Although the marketplace dictated that the "point fives" be sold at relatively modest prices, their manufacturing costs were if anything higher than those of their larger companions in the various ranges. This was due to the inescapable fact that the level of precision required to produce the engines to fully functional standards actually rose with decreasing displacements. It was this factor that forced the early abandonment of the Elfin 50, as related elsewhere. Consequently, the unit profit to be derived from the production of the little "point fives" was somewhat marginal.

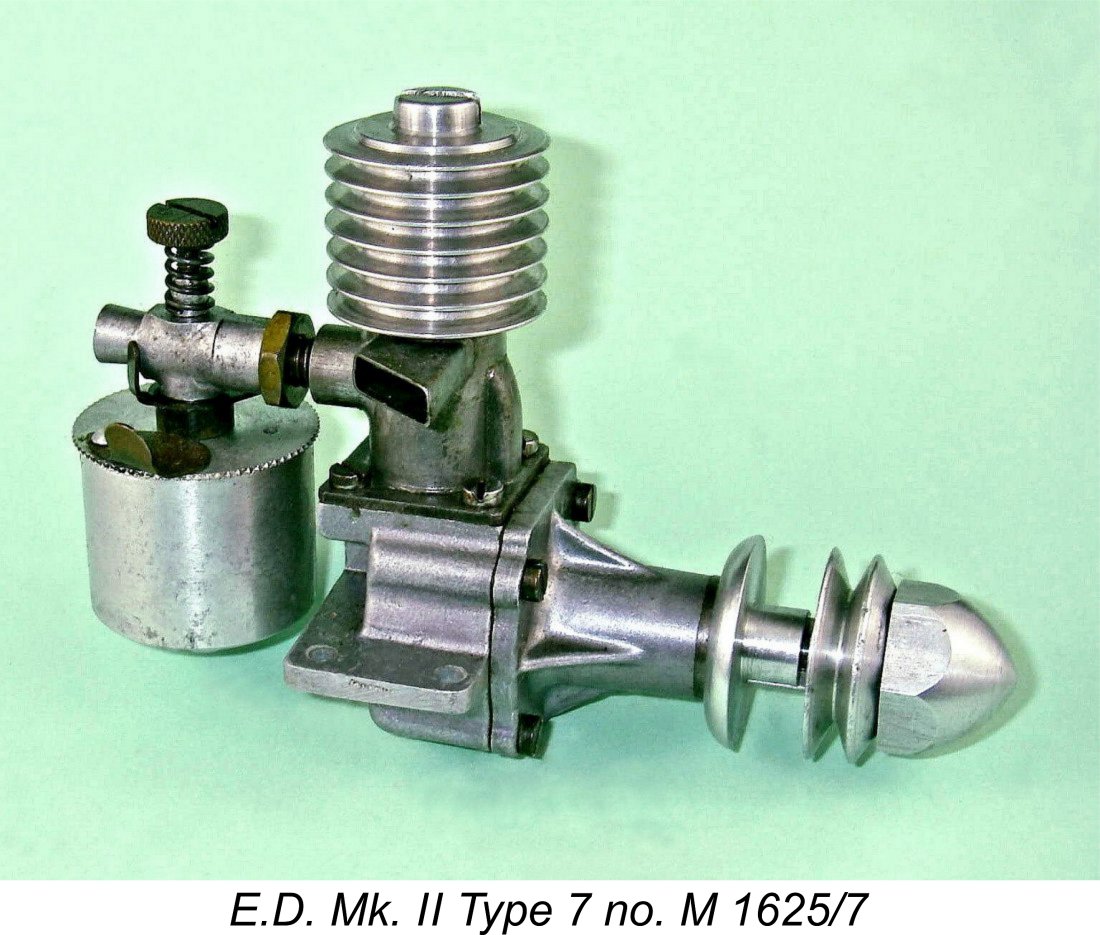

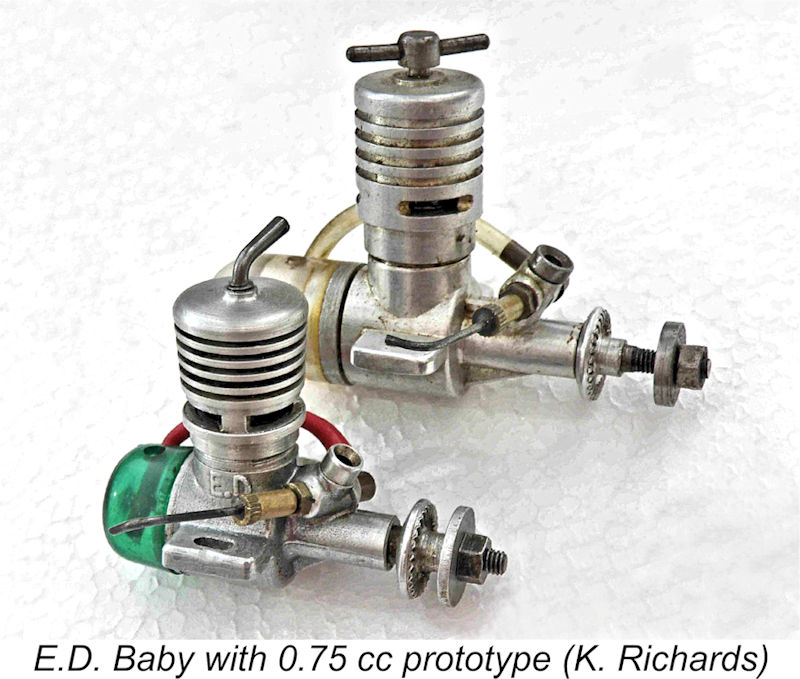

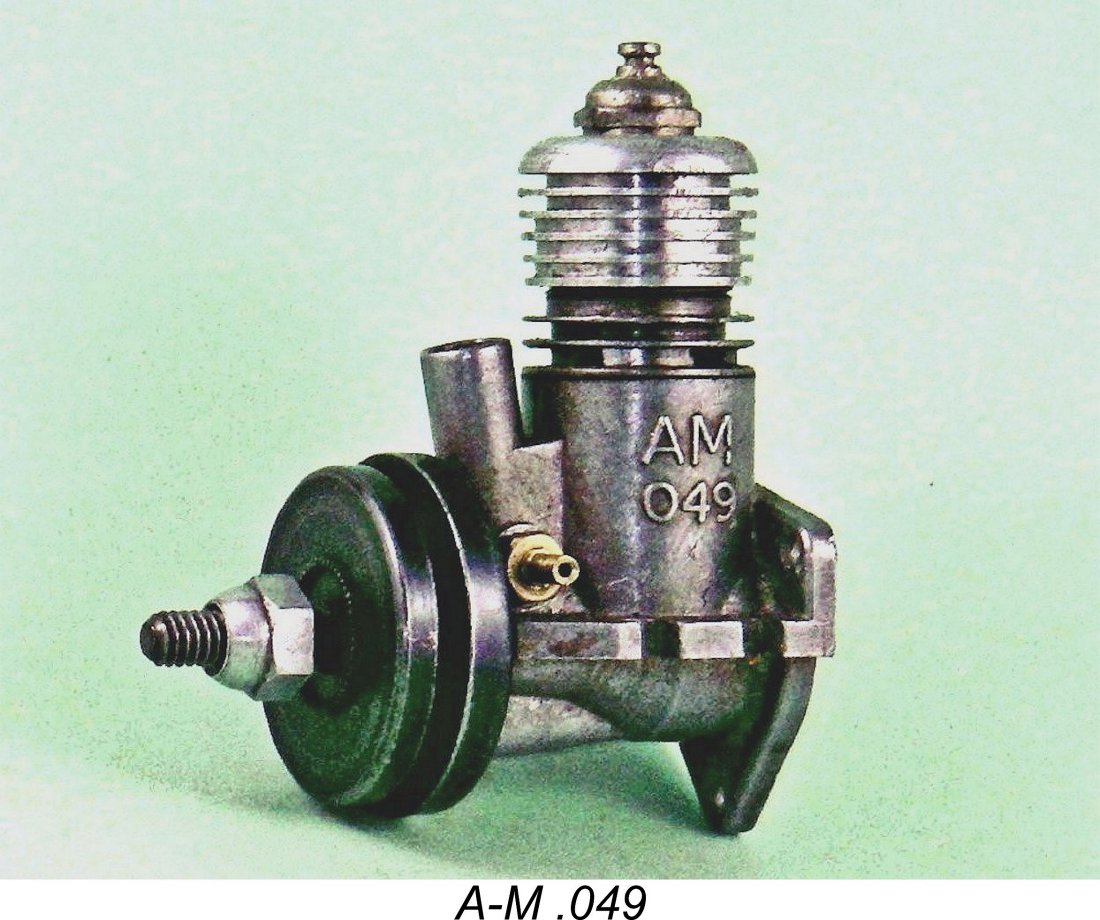

As a result, by early 1957 Mills, FROG and D-C Ltd. all had successful and well-received model diesels in the “¾ cc" category, more or less corresponding with the American ½A class which allowed engines of up to 0.050 cuin. (0.81 cc)displacement. These models were The initial decision to develop an E.D. 0.75 cc (.046 cuin.) diesel model was apparently taken in 1957 while Basil Miles was still active behind the scenes as E.D.'s primary engine designer. This decision was likely prompted by the January 1957 release of the FROG 80. Miles undoubtedly did some work on this engine, to the point of producing at least one prototype which was constructed very much along the lines of the existing E.D. Baby 0.46 cc diesel albeit a little bigger, as the attached image will confirm. Internally, the engine is more or less just a slightly enlarged Baby. This prototype has been preserved by Kevin Richards. The Miles 0.75 cc prototype appears to have represented a good first step towards the development of E.D.'s own ¾ cc entry. Miles' departure from the scene left E.D. facing a situation in which development of their range had stagnated and their production program was in a very shaky state, with an increasing frequency of quality control issues along with a growing inability to meet demand for certain models. All of this was causing a perceptible erosion of E.D.'s formerly-strong market position, a fact of which neither the Directors nor their bankers were unaware. It was clear that they needed help, and needed it quickly!

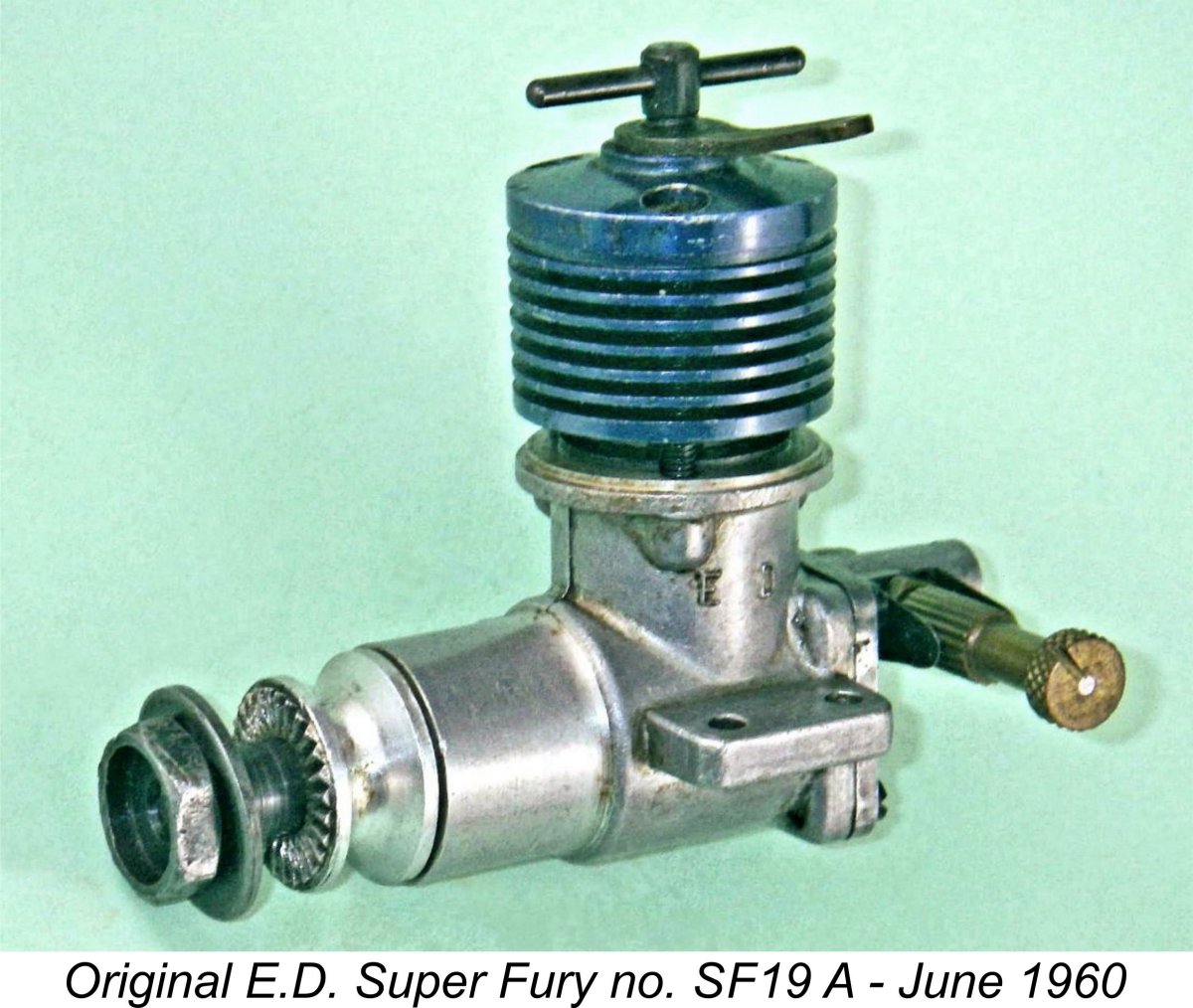

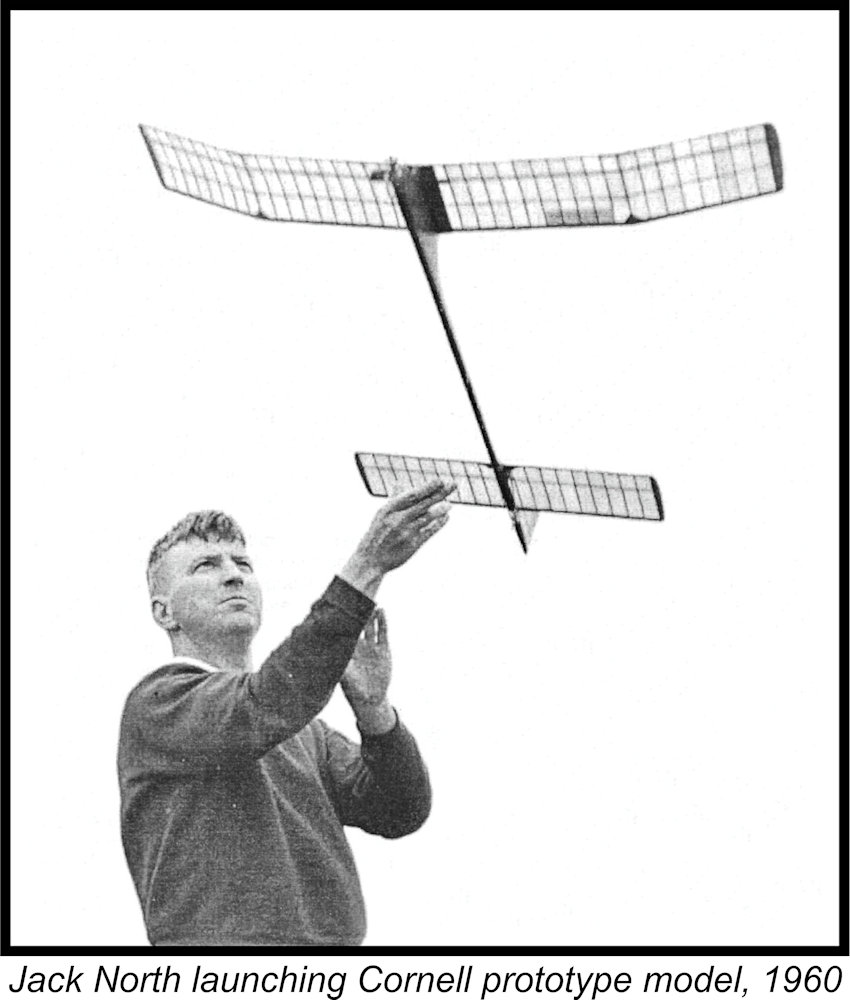

During late 1958 George received a letter from Jim Donald, then Managing Director of E.D., suggesting that Fletcher join them to fill the gap left by their loss of Miles' services. George did not wish to leave IMA at that time, suggesting instead that Gordon Cornell contact Jim Donald. Gordon was quite happy to do so, resulting in an offer from E.D. which Gordon accepted. Accordingly, in late 1958 Gordon moved over from IMA to become the chief engineer for E.D. It quickly became apparent to Gordon that there were many problems at E.D., the state of their finances being merely one such issue among others. All of the key players were very nice people to work with, but there Once having settled in and assessed the many design and production problems facing the company, Gordon prepared a plan as requested. The first step was to address a number of production-related matters. Gordon's efforts in this regard soon resulted in a 300% increase in the company's production capacity. He then took on the first of a number of engine design challenges by redesigning the somewhat lacklustre Fury to produce the first in the long-lived series of disc-valved Super Fury 1.46 cc engines that were to come. This design was developed during 1959, finally appearing on the market in January 1960. It was a great success, having an outstanding performance by the standards of the day, especially in tuned form. Meanwhile, outside events were shaping up which were to goad E.D. into re-activating their 0.75 cc diesel project which had been sidelined as a result of Basil Miles' departure. The British ½ A Revolution of 1959 Prior to 1959, British modellers had for the most part been committed to the use of diesel engines, at least in the small and medium displacement categories. However as 1959 rolled around, the success of the American and Japanese glow-plug motors then reaching Britain in ever-growing numbers had created a situation in which many British modellers were at last ready to give glow-plug operation a fair trial in these lesser displacement classes. The previously-noted attractions of small engines had by no means diminished over time - what had changed was the willingness of British modellers to experiment with glow-plug operation. D-C, Mills and FROG already had well-established diesel models in the ½A displacement category, but the British marketplace was now receptive as never before to giving small glow-plug motors a fair trial.

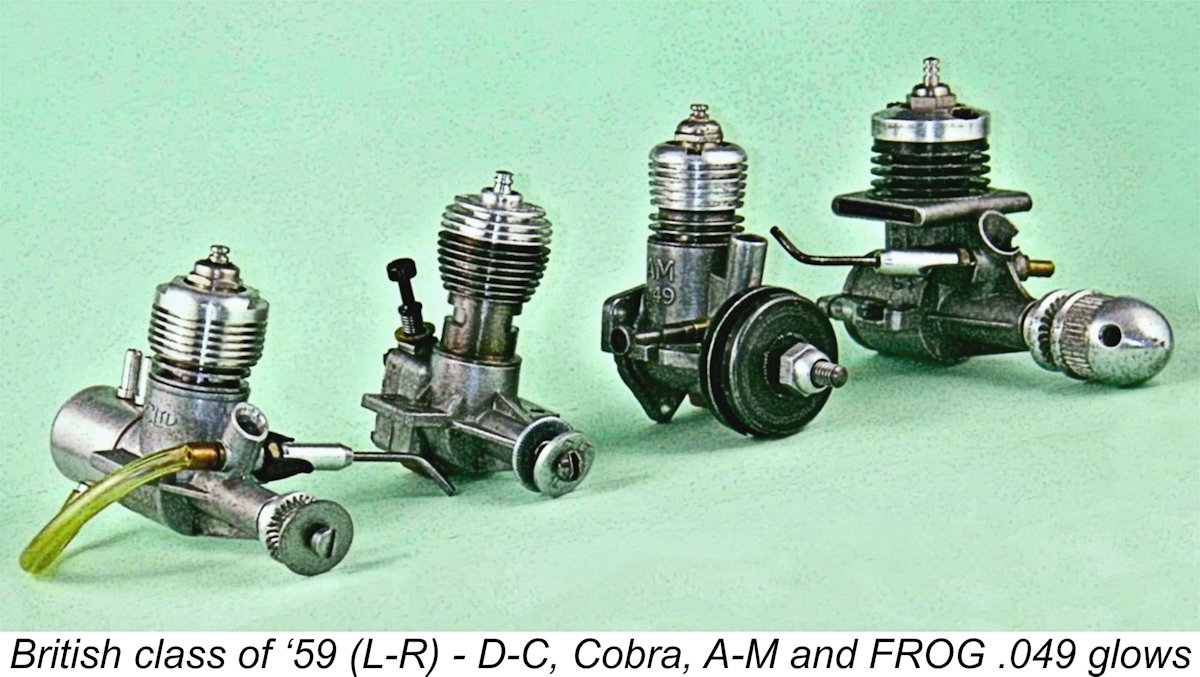

E.D. must have become aware of the above initiatives on the part of their competitors at a very early stage. The initial manifestation of the coming competition for ½A sales was the appearance of the FROG .049 in July 1959. This was simply a glow-plug conversion of the well-established FROG 80 diesel model. It was followed almost immediately by the widely-publicized release of the Allbon Dart-based D-C Bantam in prototype form to selected reviewers in the following month. The impending release of the A-M .049 (a straight Wen-Mac clone) was also public knowledge by July 1959, while the Cox-influenced Cobra .049 was rather unconventionally announced before the end of the year through its inclusion on the plan for the new KeilKraft Firefly control-line stunt model.

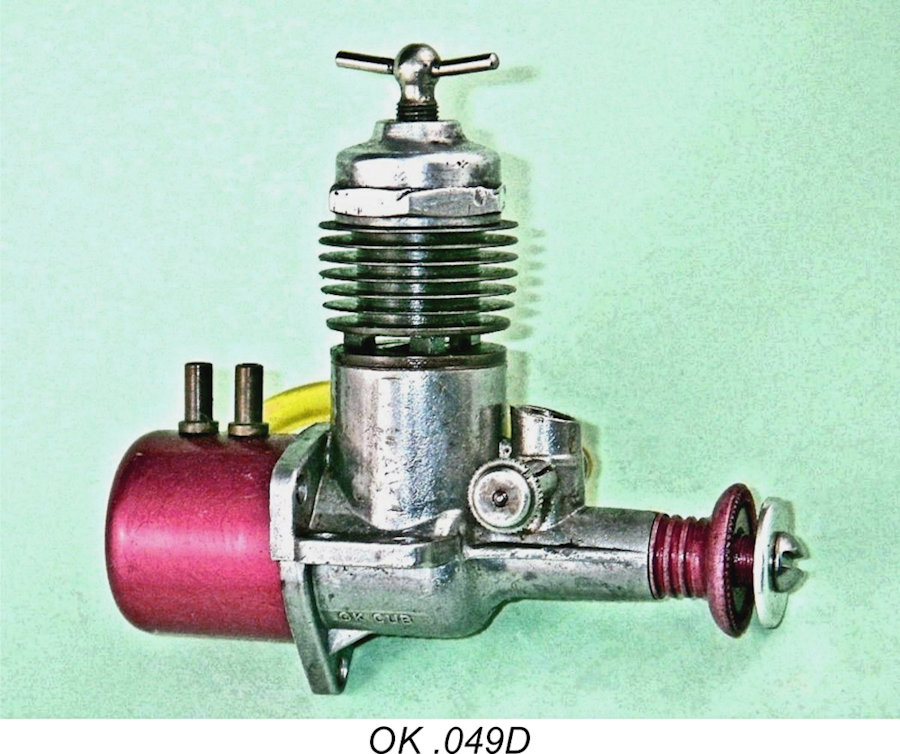

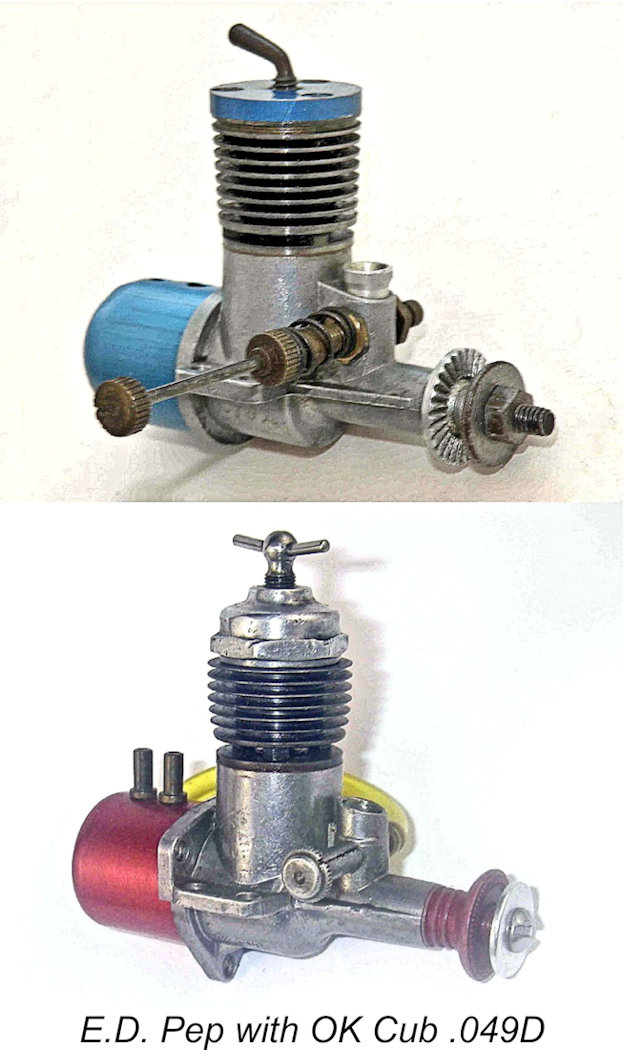

Accordingly, a decision was taken to revive the still-born 0.75 cc diesel project which had become side-tracked when Basil Miles departed. Kevin Richards' in-depth research indicates that it was only at this stage that someone at E.D. (not Gordon Cornell!) had the bright idea of shaving some corners from the required development program by producing what would amount to an Anglicized version of the American OK Cub .049 diesel of 1954. The OK model had been a very worthy effort, as detailed elsewhere, and E.D. clearly felt that they could do at least as well themselves with what would effectively be an Anglicized version of that engine.

One of the unresolved mysteries surrounding the introduction of the Pep centers upon the basic fact that it was a diesel. The OK Cub .049 had been marketed in both diesel and glow-plug guises, so an E.D. model based on that design could easily have been developed in either form. Moreover, the .049 craze of 1959 had been stimulated by a growing interest among British modellers in giving small-displacement glow-plug motors a trial. This being the case, it's very hard to see the introduction of a new ½A diesel model as representing an appropriate response to emerging market forces as of 1959. All that such a move would really accomplish would be to position E.D. as a Johnny-come-lately competitor with the three other British manufacturers who already had well-established diesel models in this category. It seems that E.D. were in effect gambling upon the idea that after a brief flirtation with glow-plug models, British modellers would quickly return in droves to their diesel roots. A woeful misreading, if so!

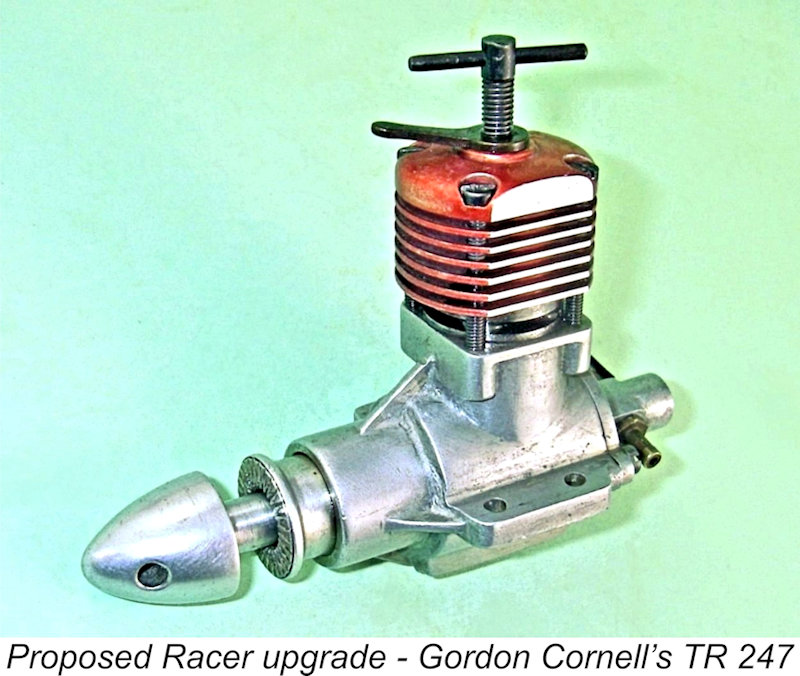

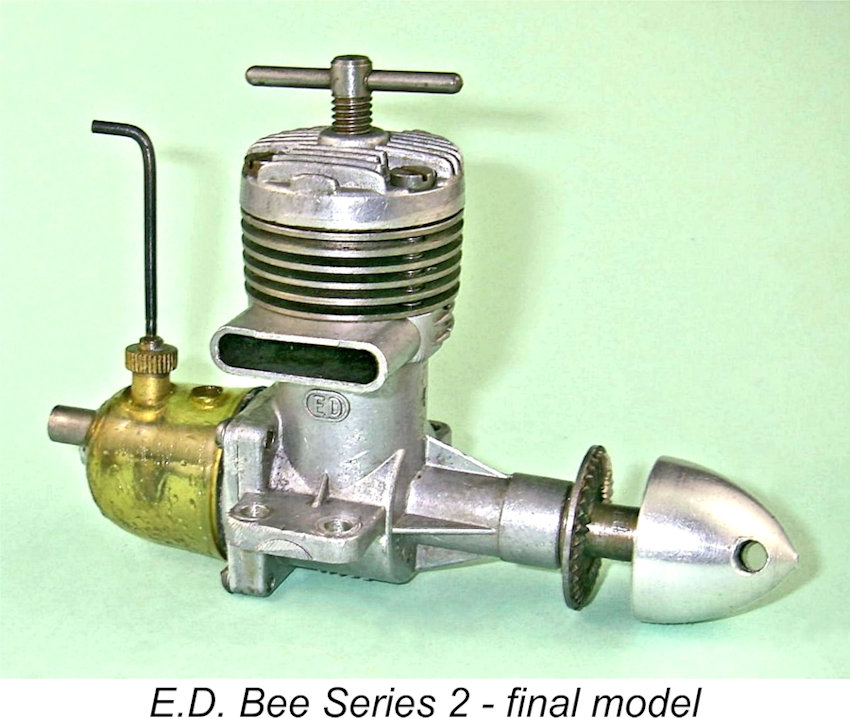

This presented management with an immediate resource allocation problem. When he joined the company in late 1958, Gordon had been put to work immediately both to sort out E.D.'s production problems and to develop a production plan to satisy the company's bankers. When the decision to develop a 0.8 cc diesel model was taken, Gordon was still hard at work fulfilling these tasks. At the same time, Gordon was also finalizing the design of the Super Fury and thinking about possible new models, including some exciting further developments in relation to the 1 cc Bee and 2.46 cc Racer which had been E.D.'s flagship products for some years. It's apparent that the E.D. management team was extremely reluctant to divert Gordon away from these valuable efforts with respect to sorting their production issues and upgrading their existing range - after all, that was precisely what they'd hired him to do! Accordingly, in addition to their adoption of the general design of the OK Cub they took another somewhat radical decision which was to have far-reaching consequences - they elected to outsource many aspects of the detailed design and production of the new model. They clearly believed that this two-tiered approach was the only way in which they could get a new design onto the market within the required time-frame without disrupting the other concurrent initiatives being pursued by Gordon Cornell.

As we shall see, the new model was designed to utilize as many existing E.D. components as possible. According to Gordon Cornell as related to Kevin Richards, E.D. had plenty of in-house production capacity available at this time. Output had fallen below demand prior to Gordon's arrival, but we have already noted that he had moved quickly to raise production capacity by some 300%. Accordingly, the agreement with Bardsley's could not have been in response to a shortfall in this area. It seems likely that it had more to do with a desire to avoid deflecting Gordon away from his work in connection with the upgrading of a number of established E.D. models as well as keeping the bank manager happy. In effect, E.D. were taking their first step into the realm of "badge engineering" - the new model would bear the E.D. name but would in reality be a product of a collaboration between E.D. and a different company altogether. They were to repeat this pattern again in the future .............. Unfortunately, on this occasion they omitted one vital step - they failed to consult with their own newly-appointed chief design engineer Gordon Cornell with respect to the design or production criteria relating to the contract. In fact, it seems that Gordon was not even informed of this initiative, at least until considerably later. Therein lay the seeds of later dissent! Development Problems with the Pep The new model was soon under development by E.D. and the Brentford company in accordance with the terms of the contract. Time was of the essence, since E.D. were already set up to become Tail-end Charlie among British ½A manufacturers. The key marketing target was the 1959 Christmas season with its greatly enhanced sales potential.

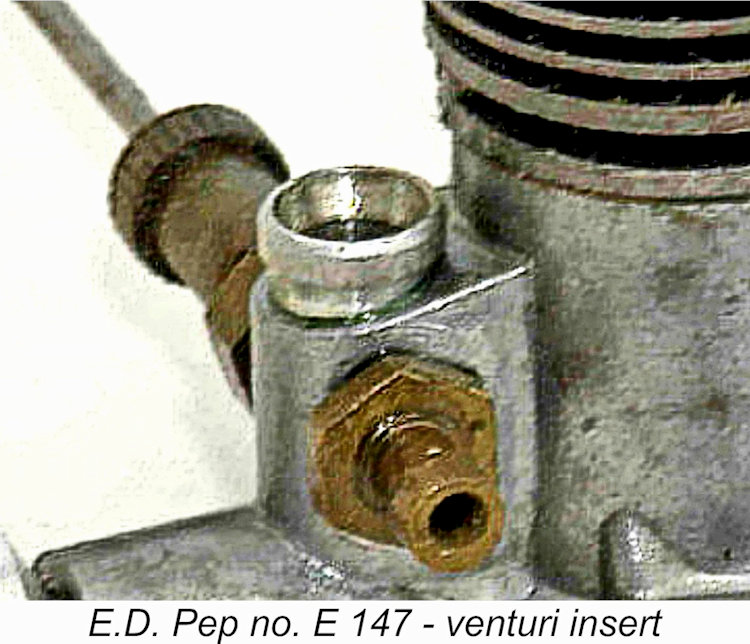

Throughout this period, Gordon Cornell remained in ignorance of the very existence of the Pep project, being kept hard at work getting the Super Fury ready for production, considering his proposed improvements to the Bee and the Racer, contemplating a number of possible new models and sorting out some existing production problems. Because of this, there seems to have been no appropriately-qualified individual within E.D. who was keeping track of the way in which the project was developing. All that was happening was that money was being spent in significant quantities! Given the considerable investment which had been made in design, tooling and die-making by the time the Pep reached the prototype stage in the latter half of 1959, it must have come as a great shock to E.D. management to find that the prototype engines fell well short of meeting their expectations. Among other problems, they would only run with gravity feed, and even then not consistently. The design team hadn't realized that the OK .049 glow and diesel models had different-sized venturis, that of the diesel being smaller to maximize suction and provide better fuel atomization. Re-enter Gordon Cornell, Stage Left!

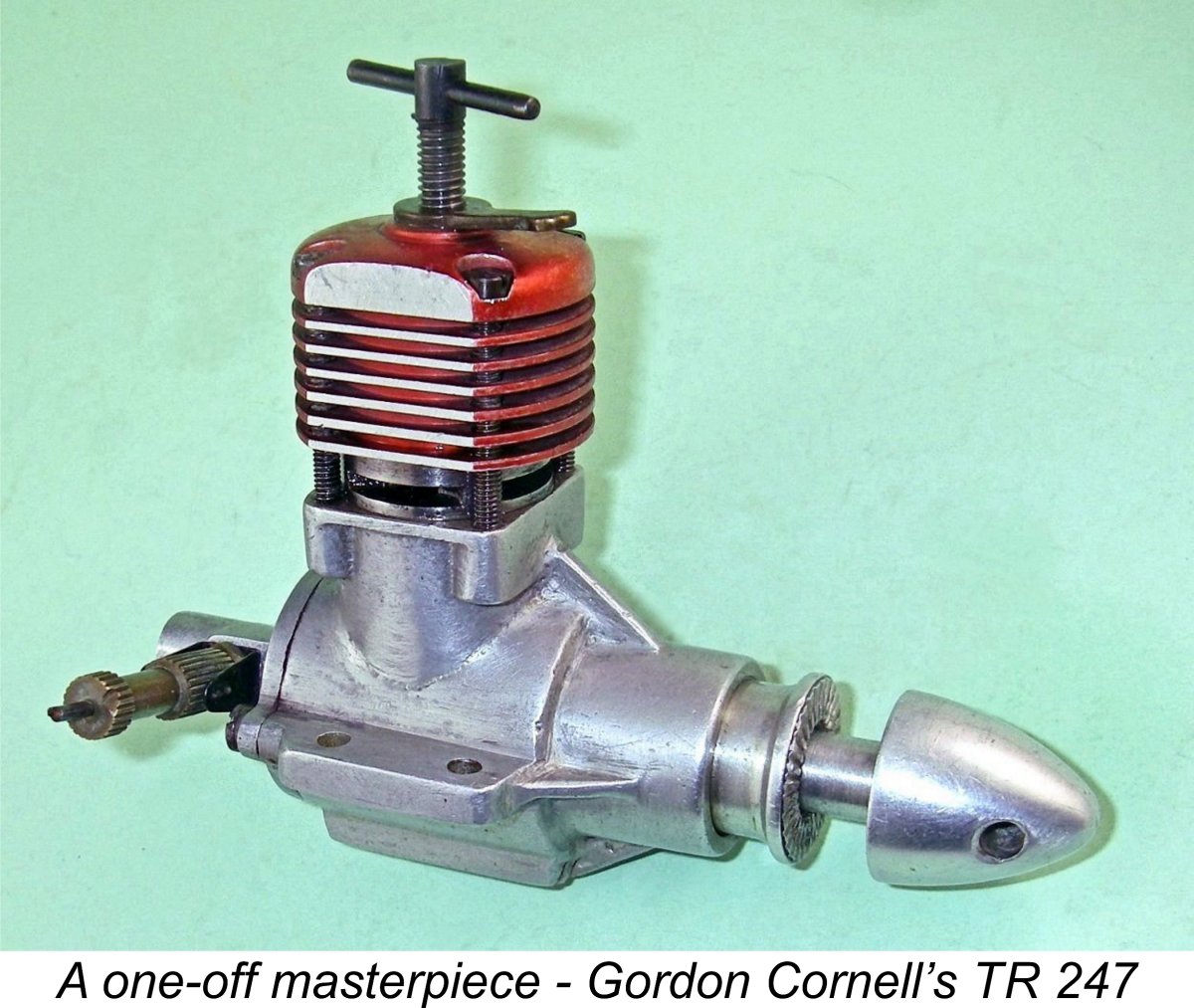

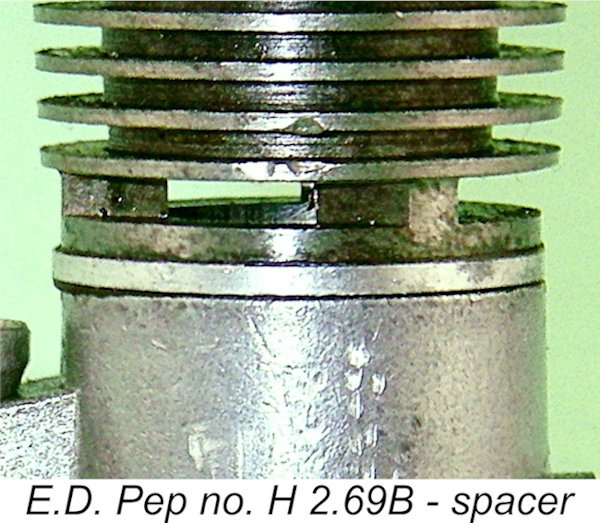

Accordingly, Gordon was diverted away from the various engine upgrade programs upon which he was then engaged, being tasked instead with the job of sorting out the dog's breakfast into which the Pep program had evolved. Quite apart from his natural frustration at having been called in after the fact, Gordon was not best pleased to learn that the new model was to bear his own nickname of "Pep"! Be that as it may, this was very much a case of too little, too late. A large number of finished components were already in existence, and economic considerations said that they All of this tied Gordon's hands to a very large extent. He made a number of suggestions, most of which were not implemented, presumably because in the view of management they would have increased the cost to unmarketable levels; would have extended the development time unacceptably; or would have required the scrapping of too many finished components. Gordon's most direct "statement" to E.D. management took the form of a prototype twin ball bearing disc valve version of the Pep, using the Pep cylinder assembly along with the E.D. Bee One issue which did receive some attention was the venturi throat diameter. We saw There may also have been a perceived issue with the port timing, since some (but by no means all) examples have a spacer inserted beneath the cylinder location flange to raise the cylinder and hence increase the opening periods for the exhaust and transfer ports. But a number of other issues remained unaddressed. Marketing History

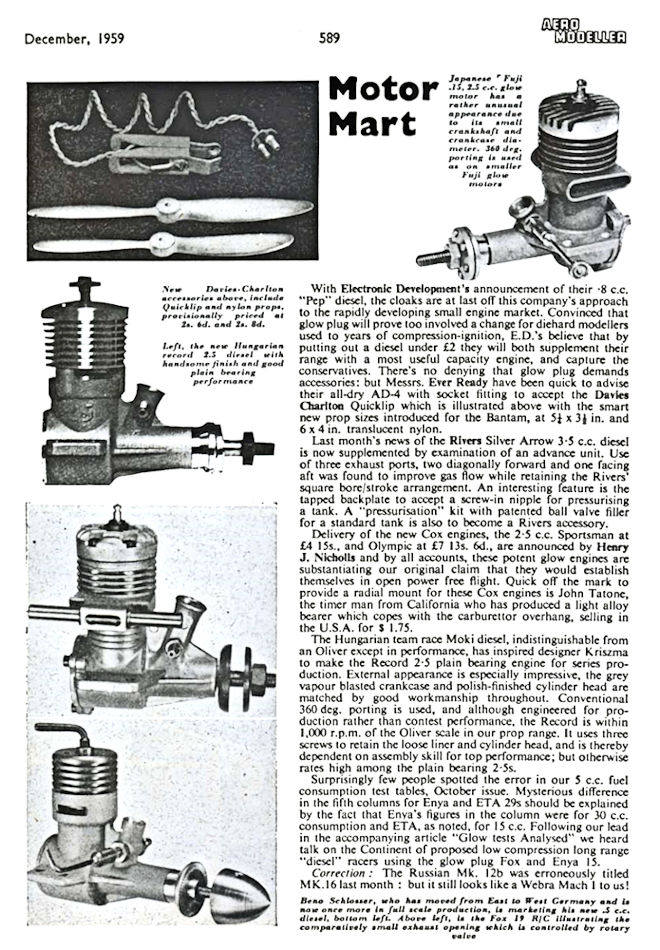

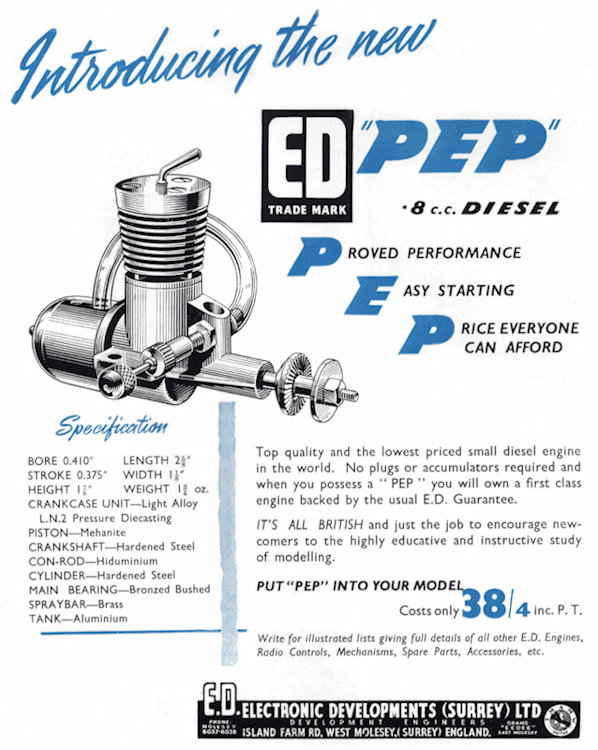

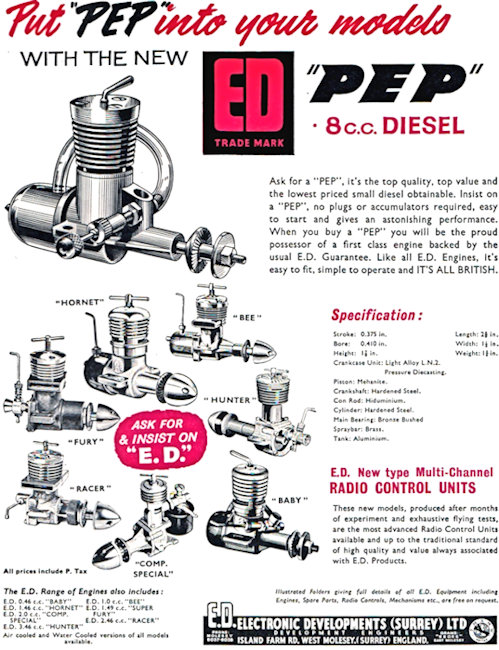

The article noted E.D.’s then-recent announcement of the Pep, also stating that the introduction of this engine reflected E.D.’s conviction that “glow-plug will prove too involved a change for diehard modellers used to years of compression-ignition”. It was evidently E.D.’s belief that “by putting out a diesel under £2 they will both supplement their range with a most useful capacity engine, and capture the conservatives”. This confirmed the previously-stated view that the introduction of a diesel to take on the ½A glow-plug competition was a gamble on the part of E.D. management based upon a mis-reading of the evolving market. The most obvious flaw in this perception was the fact that the “conservatives” were already well supplied with established ¾ cc diesels – the Pep was very much a Johnny-come-lately in that category. Realistically speaking, its only chance E.D. themselves announced the Pep with great fanfare in the January 1960 issues of both “Aeromodeller” and “Model Aircraft” magazines in the form of full-page advertisements (right) devoted solely to the Pep. Ironically, this same issue of “Aeromodeller” featured a comparative test of the three previously-released British ½A glow-plug models with which the Pep would have to compete! It seems pretty clear that this introductory advertisement was a month late in appearing………E.D. undoubtedly dropped the ball on this one. The engine sold for the very competitive price of £1 18s 4d (£1.92), making it the most inexpensive model diesel ever sold in Britain. It's hard to believe that this selling price allowed much headroom for profit, especially given the teething troubles which the engine had experienced. However, E.D. were forced to match the prices of the competition, so their hands were tied.

By September 1960 the Pep had slipped back into equal status with E.D.'s other models. Its appearances in E.D.'s advertising thereafter became increasingly sporadic - many months went by without the Pep putting in an appearance at all. It's clear that E.D. management had already accepted the fact that the Pep was not destined to be a winner in sales terms. One of the oddest aspects of the Pep's marketing history is the fact that despite E.D.'s very serious advertising efforts during the first half of 1960, it seems to have been almost completely ignored by the contemporary modelling media following its release. Apart from the previously-cited “Motor Mart” commentary in the December 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller”, I’m aware of only two other media references to the engine. Of these two, the only comment of any substance was a statement in the “Trade Notes” feature of the May 1960 issue of “Aeromodeller”. After commenting on the introduction of two new E.D. diesel fuels (Economic and Super Zip), the article went on to state that “the 0.8 cc Pep diesel is also their great new line, selling so fast they haven’t had time to send us a viewing sample!” Do I detect a certain measure of editorial sarcasm in this statement?!? The article included the manufacturer’s claim that the Pep turned a 6x4 airscrew at 13,500 RPM – a highly optimistic claim, as we shall see. The claimed "fast" sales also promote a feeling of skepticism ...............

To me, the most likely explanation is E.D.’s evident failure to provide “viewing samples” of the Pep to either magazine, as noted in the May 1960 “Trade Notes” commentary in “Aeromodeller”. You can’t comment on a product which you’ve never seen! If the magazines had wanted to inspect and test the engine, they would have had to purchase their own examples. One gathers that they weren’t accustomed to having to do this, or were not willing to do so in this case! Although there’s no hard evidence, I suspect that the reason for E.D.’s failure to push for more coverage by supplying test samples was likely based upon their immediate recognition of the fact that the Pep was if anything a bit of an under-performer by comparison with its main competitors (see below). A published test would highlight any such shortfall, hence representing a potential sales impediment. Accordingly, the company contented itself with publishing the previously-mentioned highly-optimistic performance claim without independent substantiation, also claiming that the engine was selling like hot cakes when in fact the evidence suggests that it wasn’t doing so.

There were of course other factors involved. Although it was a perfectly useable engine (as we shall see), the Pep possessed no real edge over the competition, either overseas or domestic. In fact, it was "just another ¾ cc diesel" alongside the well-established D-C Merlin, Mills .75 and FROG 80 models. The revolution of 1959 had been triggered by pent-up domestic demand for small glow-plug models rather than diesels. In this respect, E.D. had woefully misread the market. Finally, it can't be denied that E.D. was already seen as "yesterday's company" by many British modellers as more progressive firms like Allen-Mercury and P.A.W. took over centre stage.

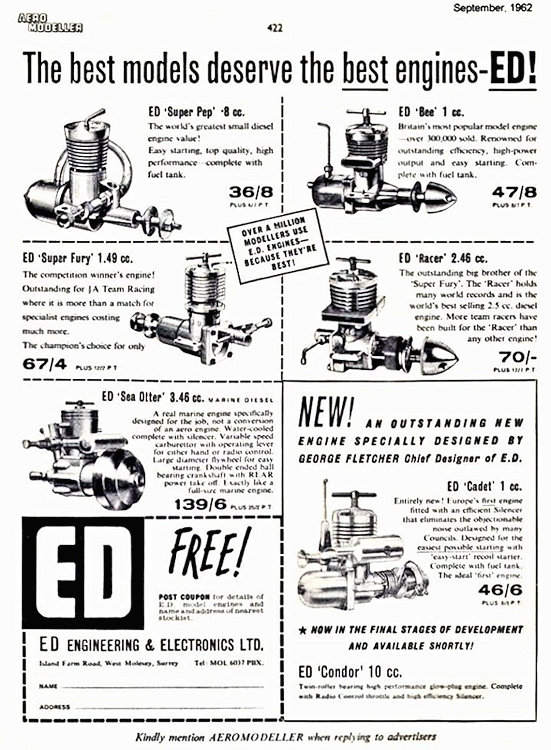

The net result of all these factors was that the Pep failed to achieve any great sales success, claiming a place in the record books by becoming E.D.'s least successful model in commercial terms. This evidently became apparent to the company quite early on. By November of 1960 the Pep was no longer regularly featured in E.D.'s advertising, although it remained in small-scale production throughout much of 1961 and into early 1962, continuing to be available at least until September 1962 when it made its final appearance in an E.D. advertisement placed in that month's issue of “Aeromodeller”. Somewhat ironically, it was by then being referred to as the "Super Pep"!

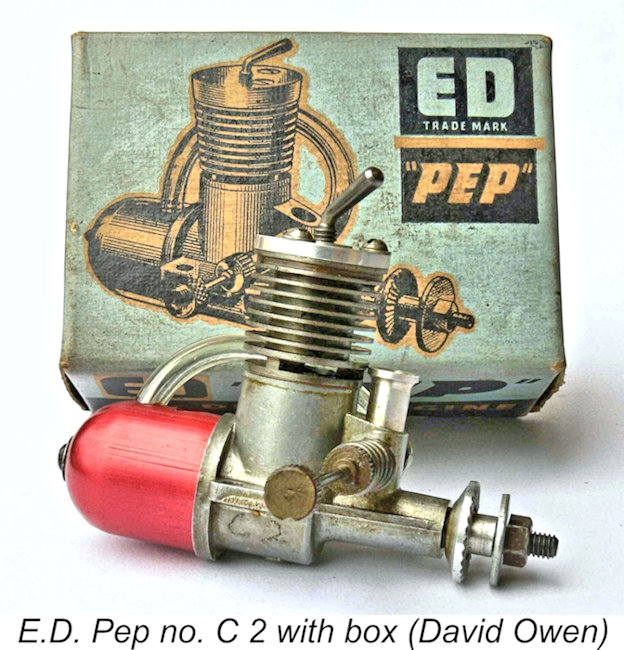

With the above background in mind, it should come as no surprise to learn that overall production figures were relatively low - at the very most, probably only a couple of thousand or so were sold in total. One direct consequence of this is the fact that examples of the Pep in good complete condition are few and far between today, changing hands on the collector market for relatively high prices. The engines were supplied in boxes which featured the engine image and associated script superimposed upon a predominantly blue background as opposed to the red colour used up to 1960 for the E.D. range in general. The new box style was also used for the 0.46 cc Baby which remained in production at a very modest pace. Exit Gordon Cornell

Despite all of this, Gordon continued his development work, which included a 3.5 cc drum-valve prototype model. While very powerful, this had some limitations as an aircraft unit due to its weight and other factors. Gordon accordingly re-developed it into the very successful marine Sea Otter 3.5 cc diesel. He also introduced At the same time, E.D. were casting about for new product lines. Gordon recalled that they had been approached by the Ministry of Defence to manufacture small diesel-powered generators for lifeboats - Ministry staff evidently did not appreciate that E.D. "diesel" engines were not true diesels! Given the fact that E.D. did not have the financial capacity to undertake such a project, Gordon judged it to be not feasible at that time.

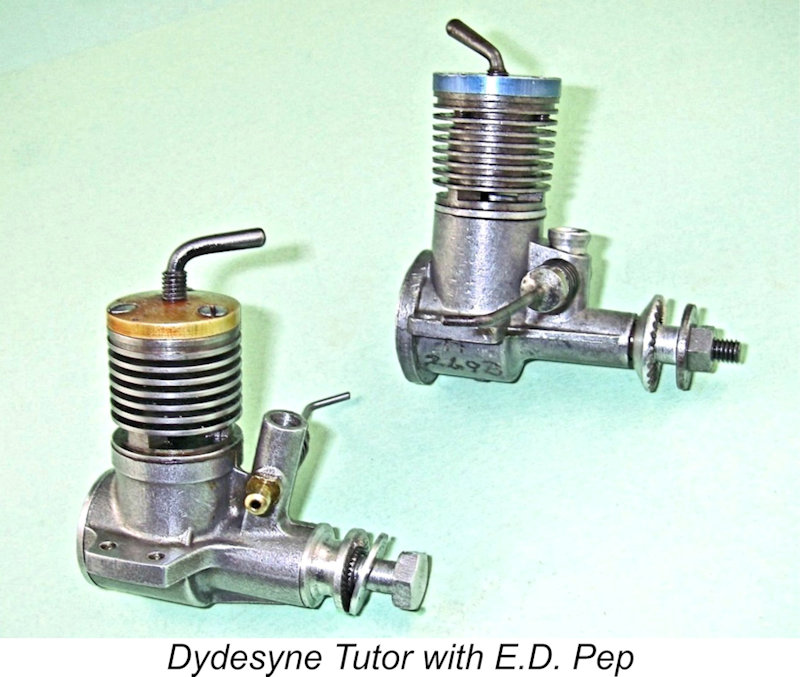

This wonderful design had its roots in the twin ball-race .81 cc prototype version of the Pep mentioned earlier, also reflecting the design of Gordon's one-off TR 247 prototype. As such, it certainly Unfortunately, Gordon was unaware that Alan Dye did not have the necessary financial capacity to underwrite such a project. After Gordon had worked all hours to complete an initial batch of engines, including a small handful of prototypes of a plain bearing This was a great pity, because the Dydesyne engines were outstanding performers which would doubtless have attracted their share of market attention if their manufacture had continued. The Tutor was particularly significant in the context of this article because it probably represented the E.D. Pep as it would have appeared if Gordon Cornell had been involved from the outset. To add insult to injury, it turned out later that Alan Dye had not been paying Gordon's insurance and tax liabilities. Gordon was forced to return to his pre-IMA employment working for Dodge Brothers (Britain) Ltd. By an ironic twist of fate, Alan Dye later ended up working for Gordon at Dodge Brothers, thus reversing their former positions! Looking back at the Pep

All of this has contributed to a subsequently well-entrenched view of the Pep as a second-rate production that was cobbled together in far too much of a hurry and failed completely in the marketplace as a result. The engine has carried the stigma of having been one of E.D.'s least successful designs from that day to this. Now it's undeniably true that the engine failed in commercial terms. But that is only one yardstick of failure - many factors can contribute to such an outcome, some of them having nothing to do with the engine itself. How bad was the Pep in purely practical terms? The engine was never the subject of a published test in the modelling media - in fact, we saw earlier that its coming and going were pretty much ignored altogether! This being the case, I'll have to rely upon my own recollections and observations to gain a retrospective view of the engine in service. In assessing a model diesel in a strictly utilitarian sense, it's perfectly legitimate to draw upon actual experience with the engine in operating terms. I'm in a position to do this because I actually owned and used a blue-headed Pep for a few years in the mid 1960's before moving from England to Canada in 1966. This I used my little Pep in several models, one of which was a small free flight sport model with the others being compact small-field control line designs. One of the latter models had previously been fitted with my faithful old D-C Merlin, which had moved on to other applications. I still have that Merlin today ……... All of my personal recollections of the Pep in actual service are positive and are confirmed by the log book that I've kept since my early years of modelling. I recall the engine as being perfectly straightforward to start and as having a quite acceptable performance. I don't remember feeling that the model which had formerly used the Merlin had suffered at all through the engine switch. Although it was a long time ago now, I can honestly say that I found the Pep to be a perfectly satisfactory unit in actual service. My notes from the time in question bear out this recollection completely. Interestingly enough, my notes also confirm my very clear recollection that my Pep had the infamous bronze con-rod, which acquired a reputation for wearing very rapidly. The rod in my Pep gave no trouble at all in service, a fact for which I have no explanation at this stage. Indeed, I have no record or recollection of any problems with the Pep during the period in which mine was in use.

Both of us moved on to other spheres of modelling activity which required larger engines, and in the course of time our respective Peps were sold on. But we both retained our positive recollections of the engine which have lasted until the present day. The fact that we had no trouble selling them way back then indicates that they retained some attractiveness as useable engines - I know that before leaving England for Canada in 1966 I sold mine to a fellow club-mate in Sheffield who had seen it run many times and was favorably impressed. Where is it now ...?!? Anyway, my own memories of the Pep are entirely positive, and my club-mate’s recollections are very much in line with my own. This being the case, could the engine really have been as bad as its latter-day reputation suggests? To find out, it was necessary to renew old acquaintance by getting my hands upon a reasonably good example of the Pep for present-day examination and testing. As noted earlier, this isn't as easy as it might be, but thanks to the kindness of Kevin Richards, my good mate and mentor in all things E.D., I was finally able to get my hands on a nice example. Moreover, a second example fell into my hands not long afterwards. So I’m now in a position to re-visit the Pep and undertake an objective hands-on re-evaluation, 50 years on. Let's get on with it! The Pep Revisited - General Description

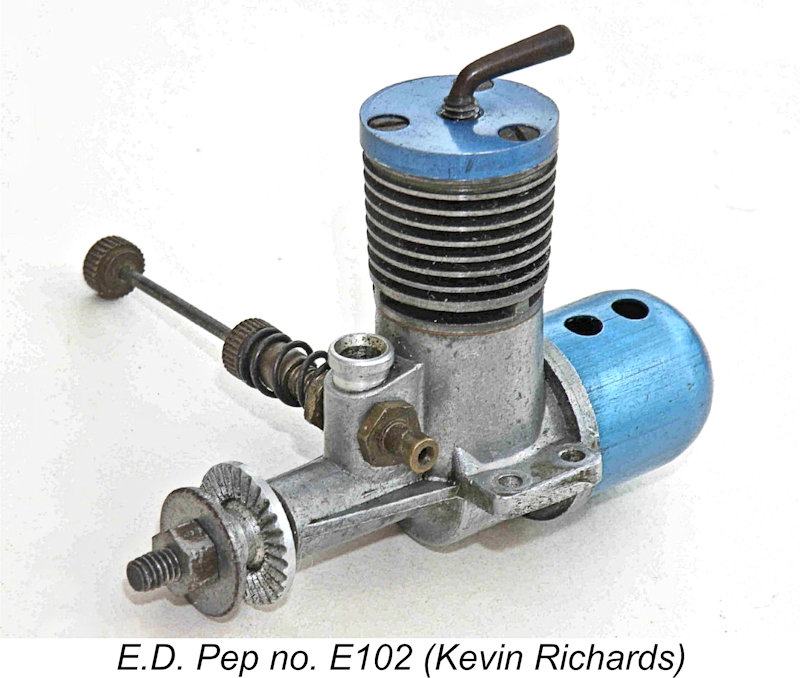

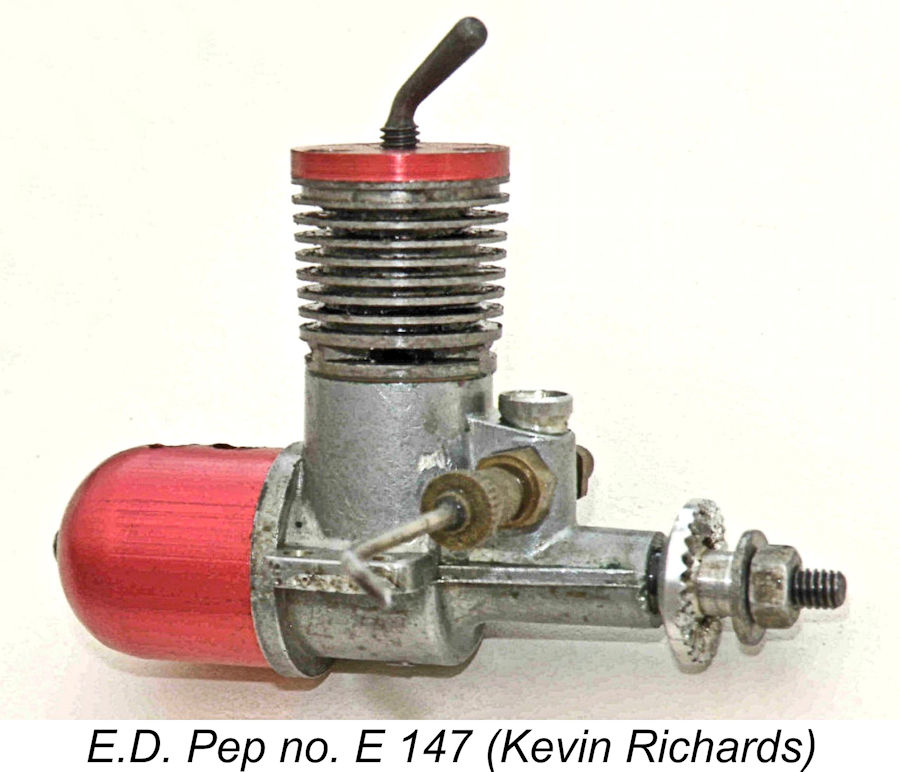

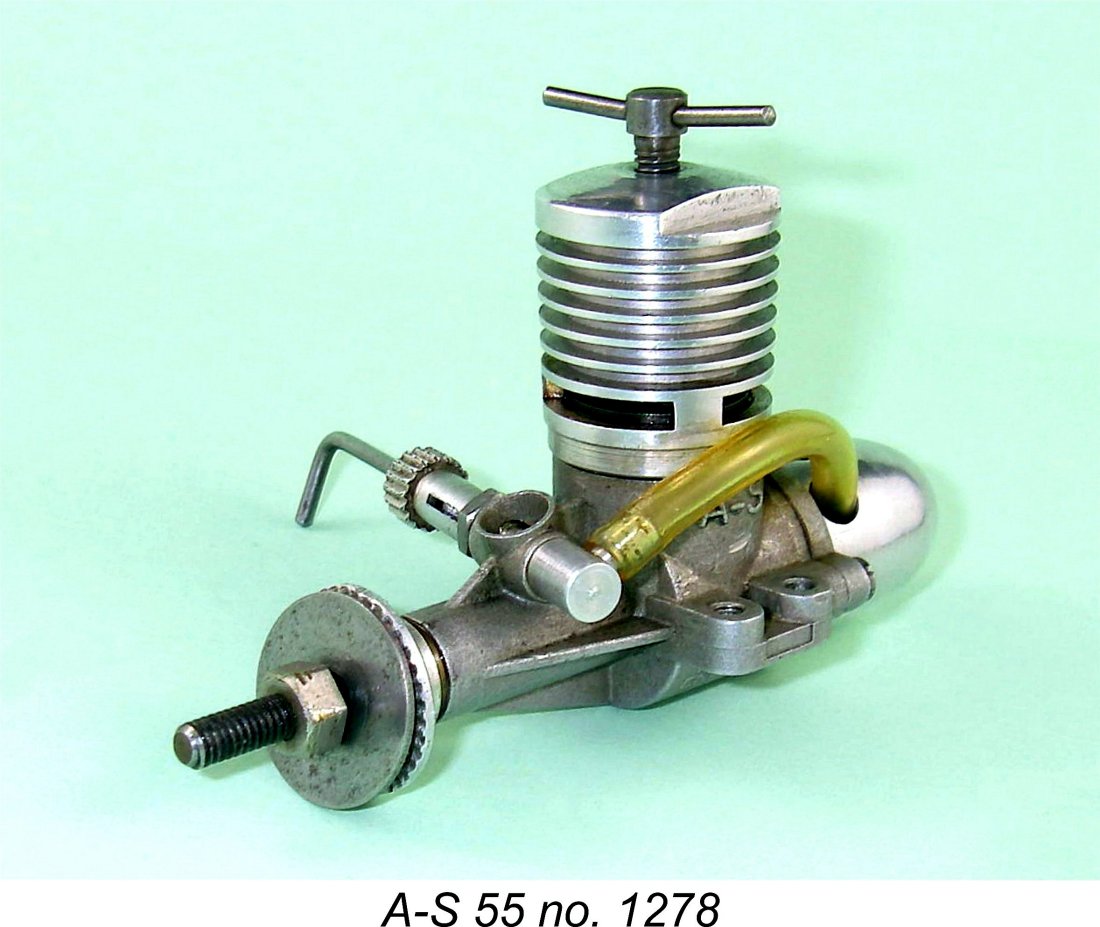

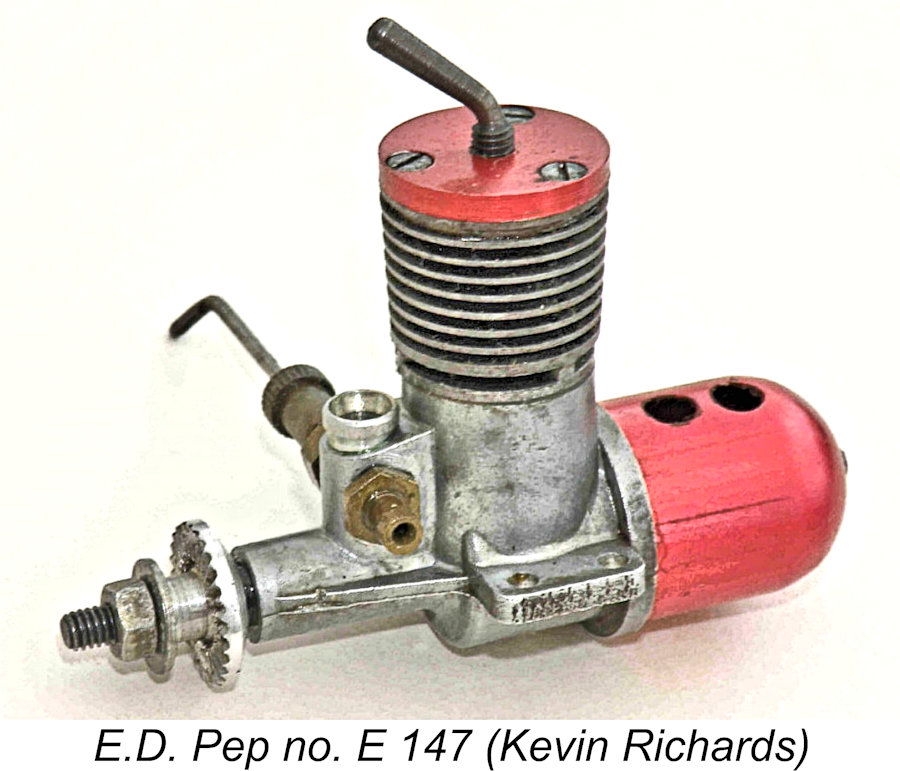

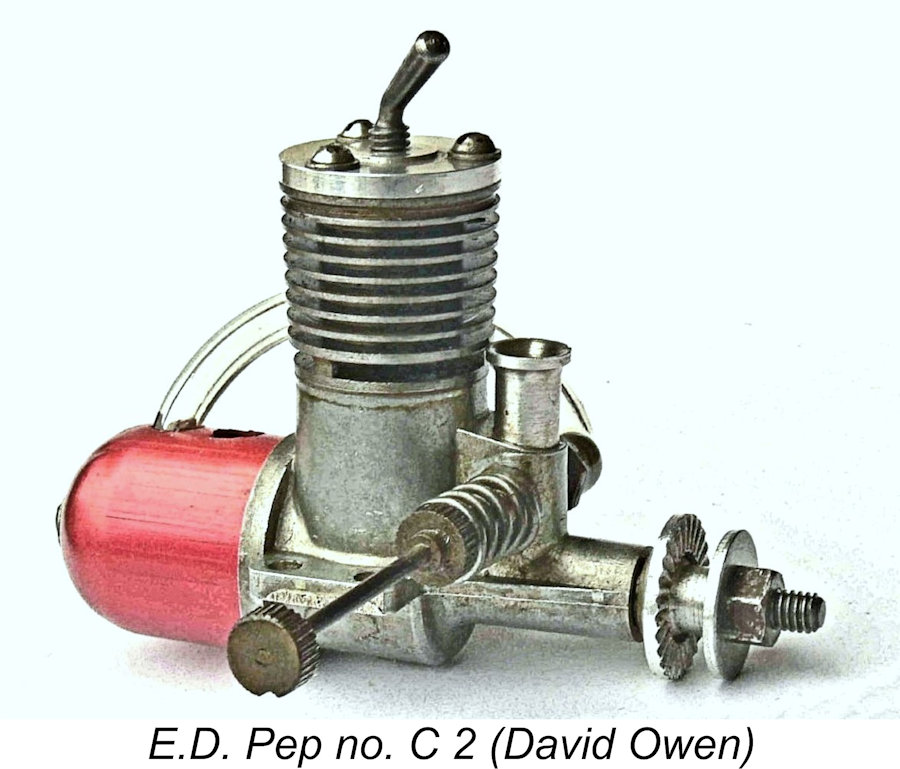

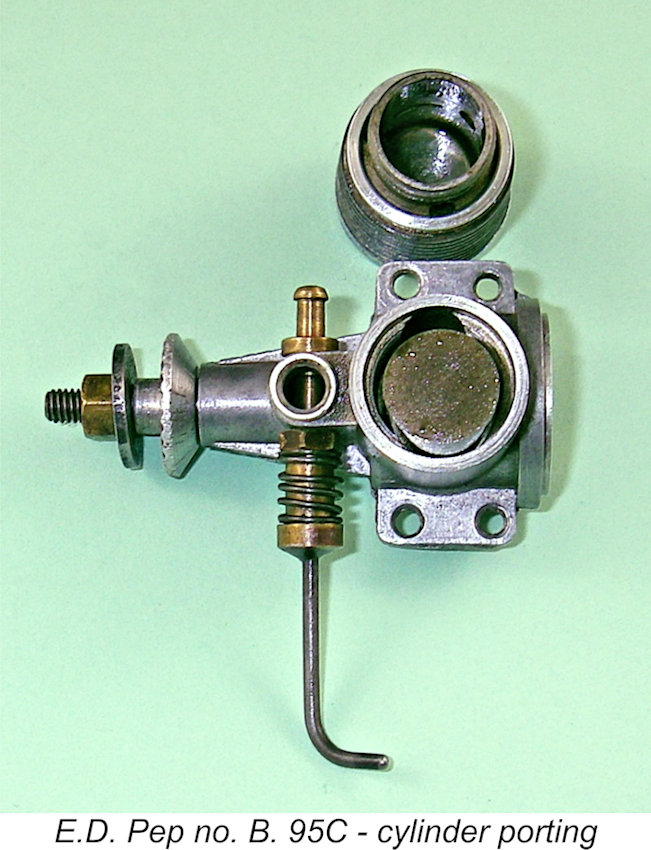

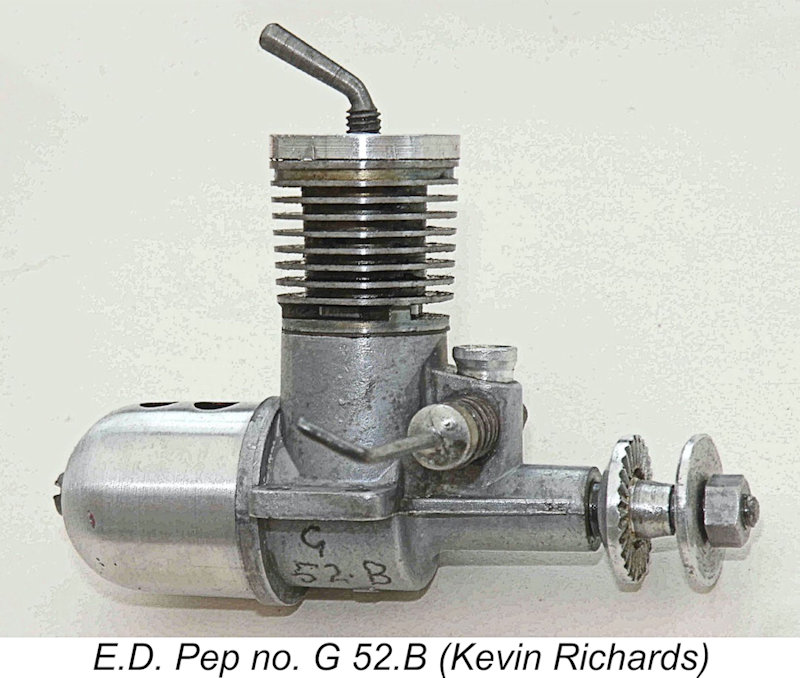

The influence of the OK Cub .049 diesel upon the Pep's design is immediately obvious when one looks at the two engines both side by side and internally. Despite the clear architectural differences, there is an unmistakable similarity in the crankcase design. In addition, the cylinder porting arrangements are identical, as is the FRV induction employed. There are differences, of course - the Pep's steel cylinder is hardened in keeping with normal British practice and has thicker (and hence stronger) fins. The contra-piston is of cast iron and is lapped into the cylinder as opposed to being a steel item fitted with an O-ring and a "shock absorber" as in the OK. But generally speaking, the Pep is very much the Anglicized version of the Cub .049 diesel that it was intended to be. Bore and stroke of the Pep are 10.41 mm (0.410 in.) and 9.52 mm (0.375 in.) respectively for a displacement of 0.81 cc (0.049 cuin.). The engine was clearly designed to take maximum advantage of the .050 cuin. upper limit for American ½A competition, perhaps indicating a degree of daydreaming on E.D.'s part regarding the possibility of marketing the engine in the US. The engine weighed in at 2 ounces (57 gm) exactly, with tank. The Pep is built around a pressure die-cast crankcase which includes provision for both screw-in cylinder and backplate components. The major difference between the Pep case and that of the OK Cub is the omission from the Pep of the radial mounting lugs which were a feature of the OK model. This doubtless reflects the fact that British modellers were generally far more committed to beam mounting than their American counterparts. The tank is missing from both of my own examples, but it was made of aluminium alloy which would have been anodized blue to match the cylinder heads. The hardened steel cylinder features integrally-machined cooling fins. The top flange is made thick enough to accommodate tapped holes for the three 8 BA screws which secure the alloy head to the cylinder. This head is centrally tapped 4 BA to accommodate the L-shaped steel compression screw. Surviving examples of the Pep most commonly feature blue-anodized head and tank components. However, examples are regularly encountered having green and red anodizing, as well as several examples which were never anodized at all! It would appear that the engines were made in small batches and that different anodizing colors were applied (or not!) to different batches, blue being merely the most common.

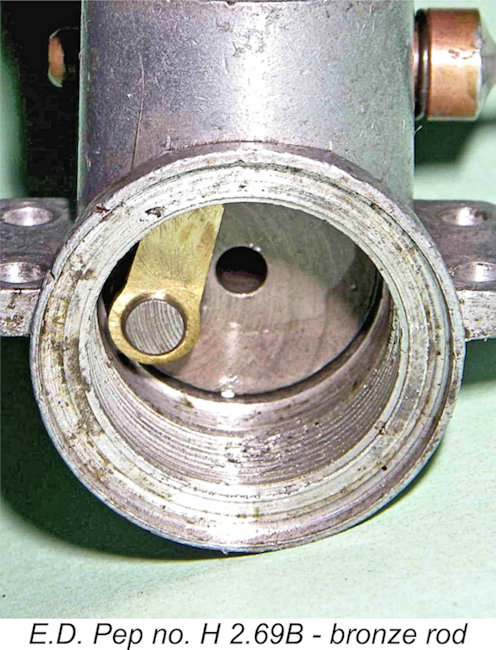

The transfer ports are fed via two milled bypass passages which interrupt the female cylinder installation thread in the upper crankcase, one on each side. A portion of the upper thread is relieved to form an unthreaded annular passage completely surrounding the cylinder just below the exhaust port belt. The three transfer ports are supplied with mixture from this annular passage, which is in turn supplied from the lower crankcase by the two bypass passages mentioned previously. Again, this precisely reflects the design of the American OK Cub models. The advantage is that transfer efficiency should be relatively unaffected by the annular position in which the screw-in cylinder ends up when fully tightened. One possible indication of a design compromise is the previously-noted presence in some (but by no means all) examples of a 0.040 in. thick alloy As noted earlier, the engine was advertised at the outset as having a con-rod made of hyduminium, although the early 1960 example once owned from new by Kevin Richards definitely had a bronze alloy rod. The con rod in both of my own examples from later production batches is also of bronze alloy, as was the rod in the example of the Pep that I owned and used many years ago. Indeed, the previously-noted advertisement which appeared in the May 1962 issue of "Aeromodeller" specifically referred to the rod being made of this material. Although it seems that both materials may be randomly encountered, I have to say that the bronze rods appear to predominate.

These measurements support an observation which I had already tentatively made prior to my detailed examination of the engine. The crankshaft of the Pep appears to be very similar to that employed on the companion Baby 0.46 cc model! That engine had a bore of only 7.94 mm to go with the 9.52 mm stroke and was thus a long-stroke design. The use of a 10.14 mm bore in the Pep along with the same stroke of 9.52 mm still left the engine only slightly over-square. The Pep crankshaft is some 1/8 inch longer than that of the Baby, while the induction port is considerably extended. However, the basic design is more or less identical, implying that the Pep crankshaft was likely simply a modified Baby item. The fact that an off-the-shelf component that was already in E.D.'s production program could be used in slightly modified form must have been seen as an obvious cost-cutting measure. Doubtless the commitment to the use of this shaft design was one of the constraints which tied Gordon Cornell's hands when attempting to sort the Pep out at the pre-production stage. As soon as one recognizes this connection, other similar connections become apparent. The prop driver also appears to be a Baby component, fitting to the front of the shaft on a self-locking taper. The prop-nut and washer also appear to be Baby items, as does the comp screw. This seems to confirm that maximum use was made of components for which tooling and/or inventory already existed. It actually appears possible that the original plan had been to use the Baby con-rod as well but that a longer rod had been found desirable after the crankcase die had been finalized. The vertical intake is fitted with the previously-mentioned insert, which once again bears a possibly more than coincidental resemblance to that used on many examples of the Baby. This was one of Gordon Cornell's few implemented improvements, as noted previously. Unusually for a British motor, the spraybar on many examples follows the OK Cub pattern by being press-fitted into the transverse hole provided for the purpose, rather than being secured with a nut in the more usual British style. Other examples have conventional spraybars with nuts for security. The thread for the needle valve on a number of examples is an unusually fine 60 tpi American thread, presumably to reduce the engine's sensitivity to this control. Although many of them are pressed in rather than being retained by a nut, some of the 60 tpi spraybars do feature a retaining nut. This thread was not by any means a universal feature - other examples are encountered with a 5 BA spraybar thread and retaining nut. In either case, needle tension is provided by a rather sturdy coil spring which fits over the thimble and bears upon the side of the intake. This is very effective in practice.

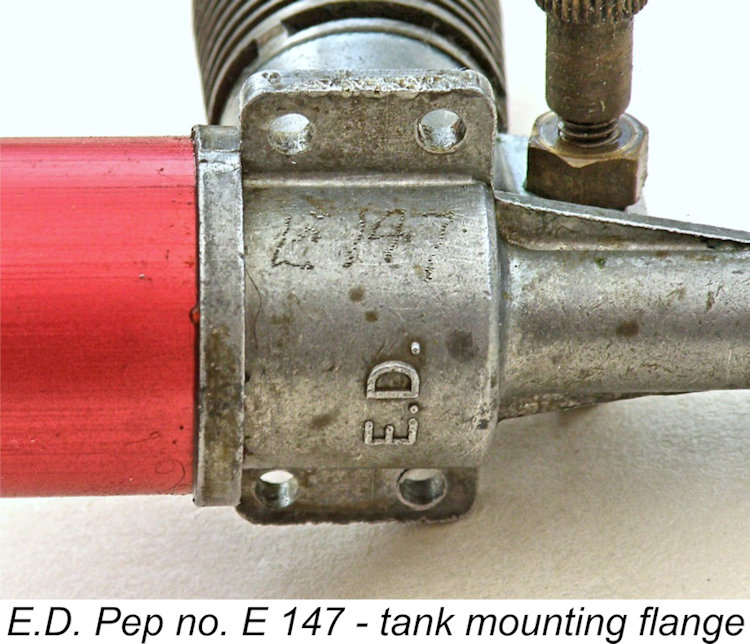

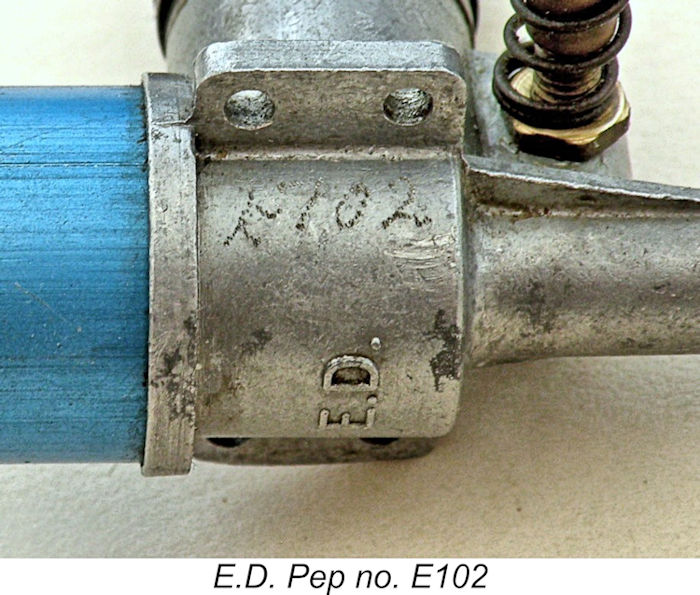

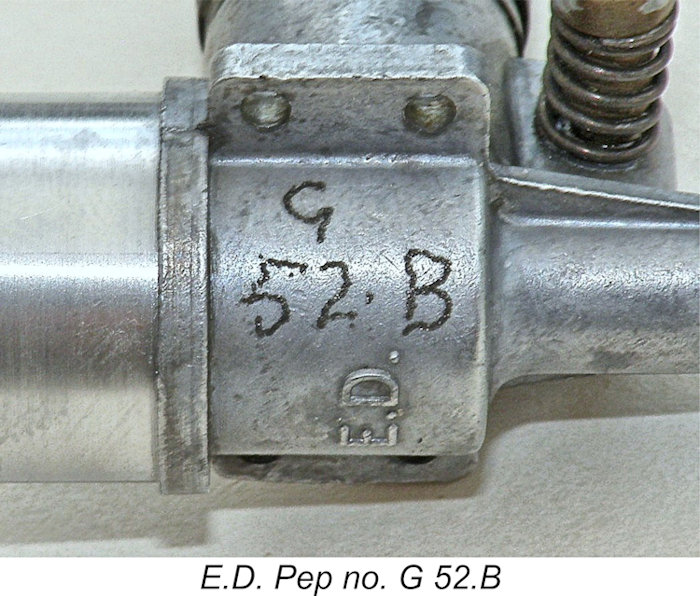

Coupled with the presence of the mounting holes, these necessary modifications significantly weakened the bearers. The accompanying illustration should make this clear. This was undoubtedly a highly annoying feature, as I well recall myself. Indeed, the contemporary A-M .049 glow-plug model came in for published criticism as a result of having the same inconvenient feature. Apart from that, the above examination confirms that the Pep was a completely conventional model diesel of its type which showed strong OK Cub influence. All fits and finishes are excellent, in my own two examples at least. That said, it's apparent that efforts were made to keep costs down through the maximum use of components that were already available from the existing production inventory. Nevertheless, the ultimate test must always be the way in which the final product performs. But before we look at that aspect of the matter, let's consider the question of identification. Identification and Serial Numbers The letters "E.D." are cast in relief onto the underside of the Pep's crankcase. Apart from that, the only other identification is a hand-engraved serial number on the lower surface of the case on one side. The above illustration showing the underside of the case from engine no. E 147 typifies these markings. As of early 1960 when the Pep first appeared, E.D. serial numbers on their other engines were invariably stamped on, so the Pep was an anomaly in this regard. It appears to have been the first designated E.D. product to be numbered in this way.

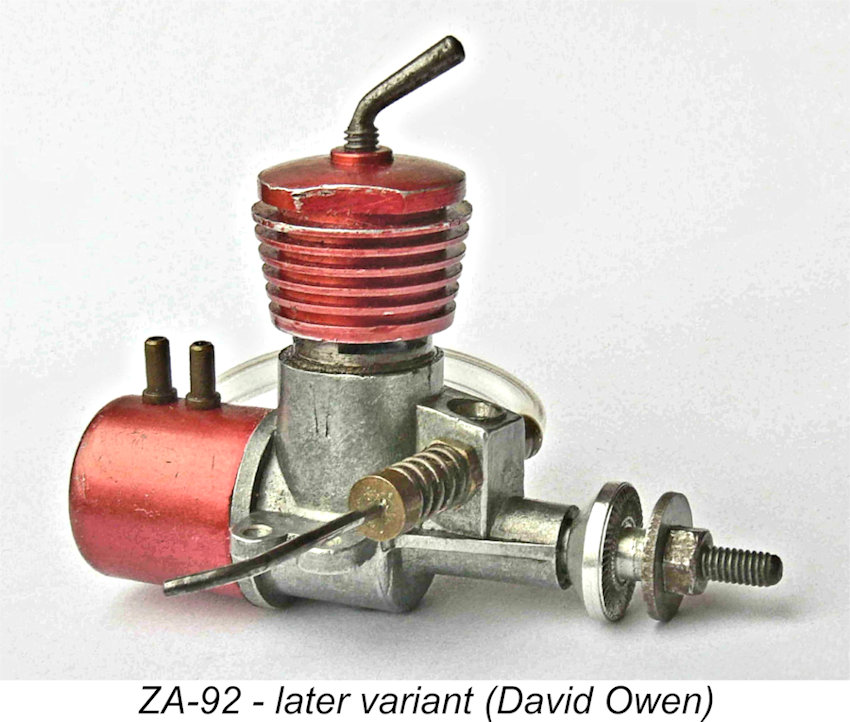

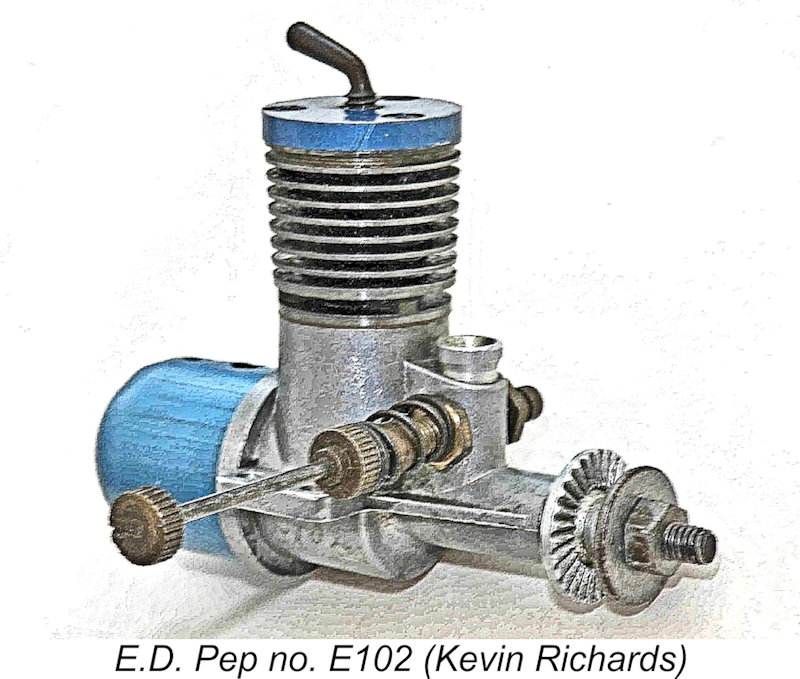

However, there appear to be a few anomalies in the case of the Pep. For one thing, the year indication letter at the end is missing from a significant number of reported examples - my unanodized New-in-Box example no. A85 (as written) is one such unit. For another, my other engines bear the numbers H 2.69B and B. 95C, both as written. In each instance, the decimal point is unquestionably there and appears to be a quite deliberate inclusion rather than a striking error. Both of these engines have blue heads but H 2.69B is missing its tank. Kevin Richards owns engine numbers G 52.B (plain head and tank), E102 (blue head and tank) and E147 (red head and tank - all numbers as written), while David Owen reported owning engine number C 2 (plain head, red tank) with no decimal point. Kevin also reported that he formerly owned engine numbers F41B (blue head and tank), H278B (blue head and tank) and A341 (red head and tank). Bob Beaumont reported owning engine no. D71C. The numbering and coloration are all over the shop, with those pesky decimal points moving about freely or being absent altogether!

However, there are some clear inconsistencies in these numbers, particularly with respect to the letter suffix issue as well as the decimal points. A case in point is provided by engine number E102, which is known to have been made in 1960. On this basis, it would be expected to carry an A suffix, which is missing. Indeed, it's noteworthy that up to now we have yet to see an example of the Pep which carries an A suffix. The most logical explanation for this would be that the year signifier was missed off the entire 1960 production, only commencing in 1961 with the addition of the B suffix. It also appears not unlikely that the letter prefixes which are invariably present are month indicators as per the usual E.D. system. Hence engine number C 2 from the above list would date from March 1960. That number would also appear to confirm that the batch numbers started from 1, this being only the second engine from that batch.

Reviewing the above discussion, the best that we can do for now is to propose the working hypothesis that the numbering system generally followed the main E.D. system with the exception that the year indicator (the A suffix) was omitted from the engines manufactured in 1960, only being re-instated in 1961 with the appearance of the B suffix to avoid the creation of duplicate serial numbers. The significance (if any) of the decimal points remains obscure. Regardless, it appears probable that any example of the Pep lacking a letter suffix dates from 1960, with the month of production being indicated by the letter prefix in the established manner. In terms of production figures, Pep manufacture appears to have been largely confined to the years 1960 and 1961, although we do have presumptive evidence for the production of at least one batch in early 1962 in the form of my own engine number B. 95C, which would date from February 1962 if our working hypothesis has any validity. The fact that engine numbers E102 and E147 feature blue and red anodizing respectively despite the fact that they are apparently only 45 engines apart raises an interesting point. If my working hypothesis regarding the numbering system applied to these engines is correct, both of these examples belong to the batch produced in May 1960. The different colors may simply reflect a lack of synchronization between the production of the heads and tanks and the assembly of the engines. If this was the case, then coloration would essentially be independent of the batch to which a specific engine belonged. The assembly staff would simply use whatever anodized components were on hand, trying as far as possible to match colors between heads and tanks (and not always succeeding if NIB mixed-colour engine C 2 is any guide!).

To me, such a figure as that implied for August 1961 would best be explained by the notion that prior to that point in time monthly production had been more or less tailored to demand. Given the engine's failure to attract much sales interest, there would have been many months in which production was very small indeed - in fact, the two August 1961 figures are currently the sole three-digit numbers which we have after 1960. The sudden "spike" in batch size which appears in August 1961 may well be due to a management realization at that time that the small two-digit batches which appear to have become the norm were uneconomic to produce and that it would be better to produce fewer but larger batches, holding off on further production until the available shelf inventory had been significantly depleted. A direct consequence of such a decision would be that there would have been subsequent months during which no engines were produced at all! Further production would have been strictly confined to the manufacture of the odd batch on an "as required" basis to replenish the wholesale stock shelf. The frequency of such batches would be entirely dependent on how fast the previous batch approached the sell-out point at the wholesale level. Given the engine's apparently lacklustre sales record, this would in turn imply that batches such as that of August 1961 were few and far between. It's likely that only two or three further batches at most were manufactured after August 1961. Whichever way one slices it, production figures for the Pep appear to have been well below average by E.D. standards - perhaps around 400 or so monthly during the first few months of production as part of the introductory stock build-up, but tapering off sharply to far lesser figures in the two-figure range thereafter, with most months after August 1961 seeing no production at all. When we consider that E.D. are known to have produced well over 2000 examples of certain other specific models in some months, we can see that Pep production was on a very small scale indeed by E.D. standards. An extrapolation from all of this over the engine's two-year production run would seem to indicate a maximum total production of somewhere between 2000 and 2500 examples. This estimate could of course be in error either way, but the present-day scarcity of surviving examples is certainly consistent with a relatively low total production figure. Speaking personally, I'd be very surprised indeed to learn that the total number manufactured exceeded 2500 units. Regardless of the truth, it appears that the serial numbering system applied to the Pep stands somewhat apart from that applied to the other E.D. models and is not yet securely understood. More serial numbers please, preferably with firm dates from guarantee cards! The Pep on Test

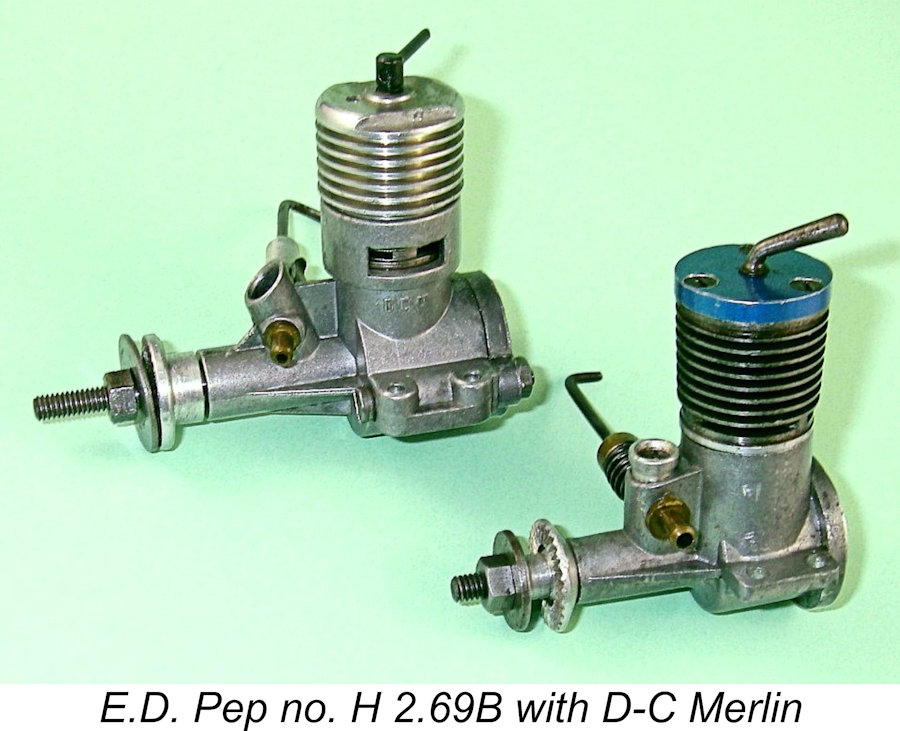

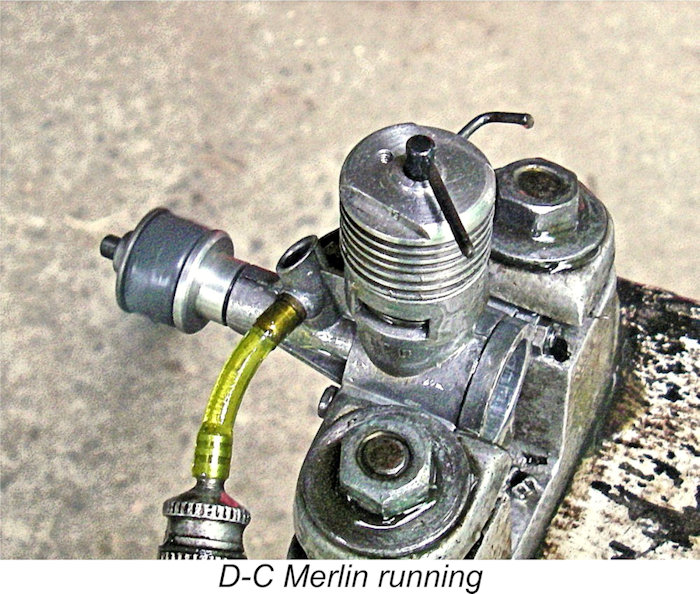

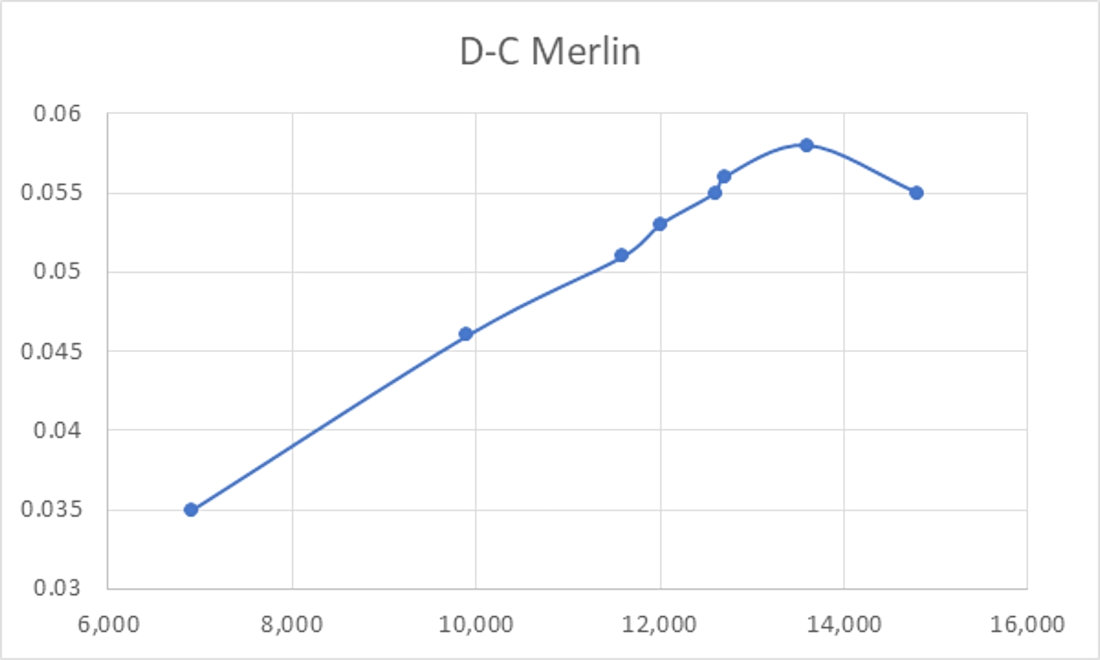

I already knew from past experience that the Merlin would bury the D-C Bantam, which was the main British glow-plug competitor in strictly commercial terms. Naturally, no-one who was specifically interested in switching to glow-plug operation would consider buying either a Pep or a Merlin, regardless of any performance differential! However, diesel-minded modellers might well linger over a choice between these two offerings. Accordingly, this comparison between competing diesels seemed fair enough to me. The Merlin which I chose for this test was not my old faithful warrior from years gone by, since I had successfully modified that one years ago to release a considerably enhanced performance. Instead, I First up was the Merlin. Every time I re-acquaint myself with one of these little units, I'm reminded of what an excellent little powerplant it was for a neophyte modeller like myself in the old days! The engine was a very dependable starter, just needing a couple of choked flicks as a preliminary to a quick start. Response to the controls was very positive without being at all critical, making the establishment of optimum settings very straightforward indeed. Once running, the little Merlin quickly settled down into a very steady rhythm, running without a trace of a misfire and holding its settings perfectly. It proved to be a very solid performer, swinging a wide range of props with no problems whatsoever. The range of speeds achieved was entirely consistent with previous experience as well as with published test figures for the engine. The following data tell the story.

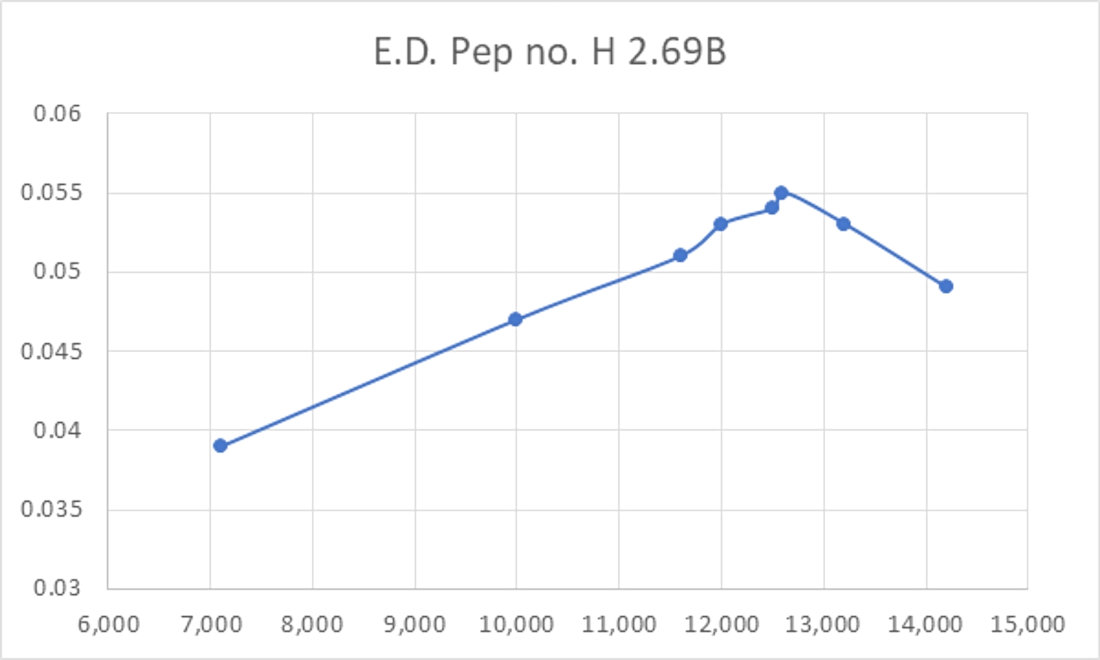

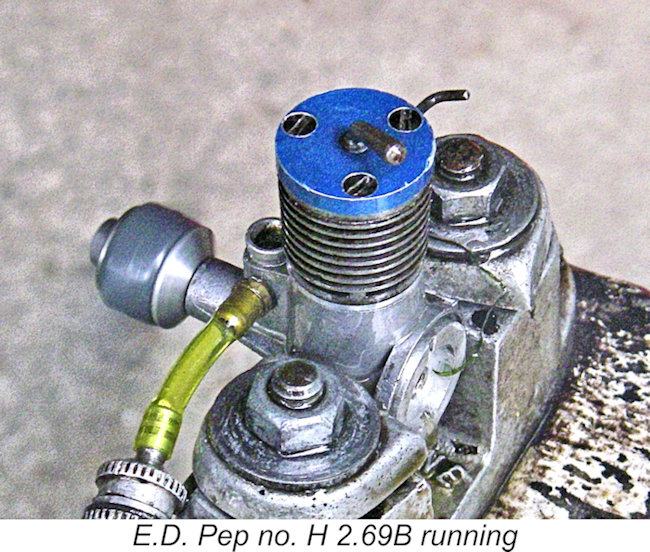

Then it was the turn of the Pep. Like the Merlin, it proved to be a very easy starter, although in this case I found that a small prime was a considerable aid to a quick start - choking alone was less effective. This is probably a reflection of the very different transfer porting arrangements. Once the appropriate technique was established, the Pep invariably started with just a few flicks. It was every bit as smooth a runner as the Merlin, being just as easy to set for optimum performance on a given prop. A wide range of prop-rpm figures was readily obtained, as follows:

It will be immediately apparent that the Pep came close to matching the Merlin across much of the tested tested speed range. If anything, it was actually a little stronger at the lower end of the range below 12,000 RPM, but fell increasingly far behind at speeds above that point. However, it could not fairly be said that the Pep was completely outclassed by the Merlin - the difference in performance implied by this test would not be overtly apparent in an actual sport-flying situation. It certainly wasn’t to me back in the day!

As far as the Pep goes, the above figures imply a peak of around 0.055 BHP @ 12,600 RPM. At this speed, the Merlin is developing around 0.056 BHP, a difference which would have little noticeable effect in a sport-flying situation. This doubtless explains why I never noticed any drop in model performance when I switched from my original Merlin to the Pep all those years ago.

Reviewing the above comparison, it becomes objectively clear that for all its rather hurried and poorly-coordinated development, the production version of the Pep that was somehow salvaged from the mess actually turned out to be a quite good little motor - far better than its subsequent reputation would suggest. It certainly outperformed the contemporary British glow-plug competition in the ½A class. Notwithstanding its troubled genesis, it begins to appear far more in the light of a successful salvage job which was a commercial failure than as the complete fiasco throughout that it is generally portrayed as having been. The Legacy of the Pep It remains for us to look into the aftermath of the Pep's failure to penetrate the marketplace to any significant extent. We already saw that the Pep saga almost certainly contributed to the eventual resignation of Gordon Cornell as E.D.'s chief engineer in early 1961. After a seemingly lengthy hiatus, Gordon's place was finally taken in March 1962 by his former IMA colleague George Fletcher, who had previously been involved with engine design and manufacture at Allbon Engineering and IMA but had become surplus to IMA's requirements when the decision was taken in early 1962 to wind down IMA's production of the FROG model engine range.

The consequent loss of machinery, records and stock was a disaster for the company, from which it never really recovered. However, a fair proportion of the vital castings and materials were salvaged, and thanks to George Fletcher's efforts E.D. were once again back in business soon after the fire, albeit with substantially reduced production capacity and a significantly truncated range. The company name was also changed at this time from Electronic Developments (Surrey) Ltd. to E.D. Engineering & Electronics Ltd. Some older designs like the Comp Special None of this was sufficient to save the "original" E.D. company, and after a brief flirtation in 1963 with having one or two badge-engineered models (notably the excellent 1.5 cc Hawk) manufactured in West Germany by the makers of the Webra range, the company underwent the first of a succession of ownership changes which resulted in most of the then-existing range being terminated. But that's another story, to be related elsewhere…….. The dropping of the Pep from the range in 1962 meant of course the cancellation of E.D.'s assembly and servicing contract with Bardsley's. However, this was by no means the end of the story! Under the terms of their parting of the ways with E.D., it appears that the Brentford company was left free to make whatever use they chose of the design and perhaps the remaining parts inventory. It's possible that E.D. owed them some money for engines already produced and this was the way in which they settled the debt. Regardless, the next move in the saga was the establishment of a new company in Brentford named De-Za-Lux Developments Ltd. It might be assumed at first sight that this was simply a reorganization of Bardsley's under a new name. However, Bardsley's had many irons in the engineering fire, making it appear more probable that this was actually a new venture altogether, perhaps funded by RipMax Ltd. who distributed the products of the new company. Some kind of tie-in with Bardsley's at the formative stage is implied by the fact that De-Za-Lux Developments seemingly took over the entire Pep project, likely including the remaining parts inventory, establishing themselves only a short distance down High Street in Brentford from Town Meadows, at number 231 to be precise. However, there's currently no evidence that the two firms were formally connected.

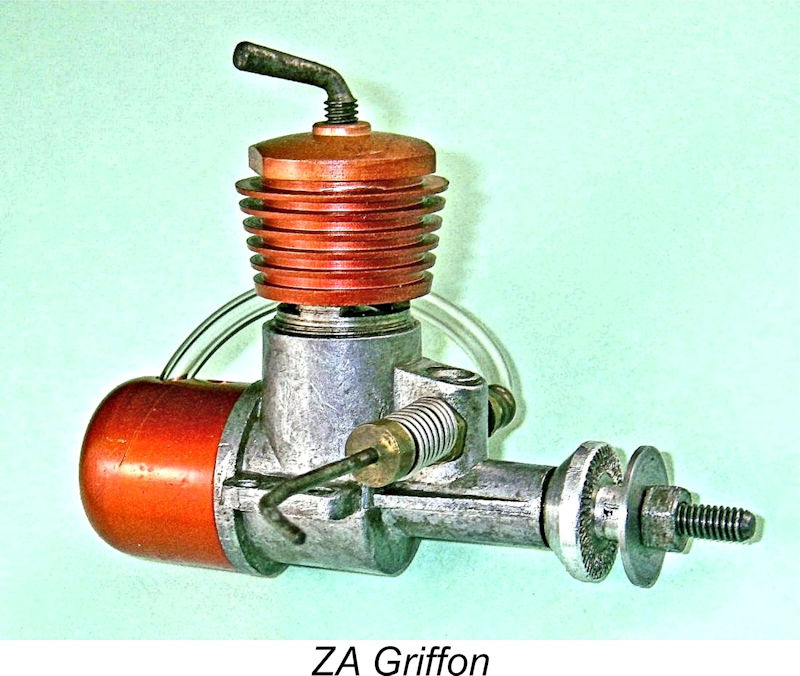

The initial examples of the ZA 92 were based upon a standard Pep crankcase from which the E.D. identification was removed by hand. These early engines appear to have been produced primarily to use up existing stocks of Pep crankcases. The resulting engine appeared on the market in around May 1963, being sold in this form as the ZA Griffon.

The ZA was hailed at the time as a new entry into the British market, but in effect it was at heart nothing more than an over-bored Pep with a few alterations. It was extremely odd how few people spotted this at the time - certainly, the ZA 92 received a far higher accolade from the media and the modelling fraternity than the poor old Pep had ever done! Its measured performance level of 0.082 BHP @ 11,800 RPM (Aeromodeller, January 1964) was well up to expectations for a plain-bearing sports diesel of its displacement. In this disguise, the Pep lived on for a few years more, earning a favorable reputation among British modellers. The ZA 92 was indeed a very nice little engine - I certainly enjoyed using my own second-hand example of the Griffon, which I still have. The company which produced it did not survive down the years - the site of 231 High Street is now buried under a supermarket car park! Conclusion So there we have it! The Pep was undoubtedly something of a compromise design which suffered from having been developed to an artificially-tight schedule by an inadequately-supervised outside contractor rather than up to a standard by E.D.’s own engineering staff. Even with this accelerated development schedule, it still arrived on the market too late to benefit in commercial terms from the British small-engine craze which triggered its development but which was over-supplied and began cooling down quite soon after the Pep's appearance. Its development as a diesel rather than a glow-plug motor resulted from a complete mis-reading of the evolving market on the part of E.D. management. As if all of this wasn’t enough, the Pep was also woefully under-promoted in terms of media coverage. The reasons for this are debatable, but most likely relate to the engine’s evident failure to offer anything special in the way of performance to its competitors. It's clear that the Pep saga had some influence upon the later fortunes (or misfortunes) of the "original" E.D. company. However, when viewed objectively in terms of its practical qualities, the Pep emerges as a perfectly useable little engine having a performance which was well up to par with that of the majority of its domestic competitors. It was actually an attractive and well-made little unit which was undoubtedly able to give good service to the relatively few individuals who cared to give it a fair trial. In my personal view, it deserves a far more positive reputation than it has been accorded in the past! ___________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN June 2013 This revised edition published here June 2024 |

||

| |

Here I’ll take a close-up look at one of the more poorly-documented and certainly least-appreciated members of the

Here I’ll take a close-up look at one of the more poorly-documented and certainly least-appreciated members of the  prototype as its underlying design inspiration. For these reasons, it forms a more than usually interesting subject for detailed study - it's always the exceptions that prove the rule! In particular, the Pep offers an ideal opportunity to examine some of the challenges facing E.D. which cumulatively led to the eventual failure of the "original" company in 1963.

prototype as its underlying design inspiration. For these reasons, it forms a more than usually interesting subject for detailed study - it's always the exceptions that prove the rule! In particular, the Pep offers an ideal opportunity to examine some of the challenges facing E.D. which cumulatively led to the eventual failure of the "original" company in 1963.

The E.D. company got its start in 1946 under the formal name of Electronic Developments (Surrey) Ltd. As the name suggests, its initial focus was as much on electronics as on model engines, but it soon achieved a strong market position on the strength of both its R/C gear and its ever-expanding range of model engines. Its first commercial model engine was the

The E.D. company got its start in 1946 under the formal name of Electronic Developments (Surrey) Ltd. As the name suggests, its initial focus was as much on electronics as on model engines, but it soon achieved a strong market position on the strength of both its R/C gear and its ever-expanding range of model engines. Its first commercial model engine was the

There had always been a certain tendency among British manufacturers to respond to the moves of their competitors rather than strike out boldly on their own initiative. When a given manufacturer did come up with something new, his competitors tended to fall over themselves to emulate his innovation.

There had always been a certain tendency among British manufacturers to respond to the moves of their competitors rather than strike out boldly on their own initiative. When a given manufacturer did come up with something new, his competitors tended to fall over themselves to emulate his innovation.

Accordingly,

Accordingly,

As matters transpired, such help was available in close proximity to the E.D. factory in the person of Gordon Cornell, who had been working on the FROG range with George Fletcher over at International Model Aircraft (IMA) in nearby Merton. Following the completion of his National Service in 1954 (during which he served in Germany as a member of the RAF), Gordon had been working as an engineer for Dodge Brothers (Britain) Ltd. before being invited by Fletcher to join him at IMA in 1957 to assist in the upgrading of the company's FROG model engine range. This proved to be a very fruitful collaboration.

As matters transpired, such help was available in close proximity to the E.D. factory in the person of Gordon Cornell, who had been working on the FROG range with George Fletcher over at International Model Aircraft (IMA) in nearby Merton. Following the completion of his National Service in 1954 (during which he served in Germany as a member of the RAF), Gordon had been working as an engineer for Dodge Brothers (Britain) Ltd. before being invited by Fletcher to join him at IMA in 1957 to assist in the upgrading of the company's FROG model engine range. This proved to be a very fruitful collaboration.

Accordingly, beginning in mid-1959 the "revolution" of 1951/52 was repeated in almost every detail, the contestants this time being British-made ½A glow-plug models rather than ½ cc diesels. The main participants were

Accordingly, beginning in mid-1959 the "revolution" of 1951/52 was repeated in almost every detail, the contestants this time being British-made ½A glow-plug models rather than ½ cc diesels. The main participants were

This decision was clearly driven by the fact that E.D. did not have an existing ¾ cc diesel design upon which to base their new offering.

This decision was clearly driven by the fact that E.D. did not have an existing ¾ cc diesel design upon which to base their new offering.  Be that as it may, the decision was taken that the new model would be developed and marketed as a diesel. This decision appears to have been taken in early 1959 - an article which appeared oddly enough in the May 1959 issue of the full-sized automotive magazine "Motorsport" recounted a visit to E.D. during which company representatives let slip the fact that they were already contemplating the development of "a new 0.8 c.c. engine, to sell for 38s". This appears to point ahead towards the development of the Pep.

Be that as it may, the decision was taken that the new model would be developed and marketed as a diesel. This decision appears to have been taken in early 1959 - an article which appeared oddly enough in the May 1959 issue of the full-sized automotive magazine "Motorsport" recounted a visit to E.D. during which company representatives let slip the fact that they were already contemplating the development of "a new 0.8 c.c. engine, to sell for 38s". This appears to point ahead towards the development of the Pep.  To accomplish this objective, they entered into a contract with a precision engineering firm called Bardsley's located at Town Meadows in High Street, Brentford, Middlesex, just a short distance across the River Thames to the north-east of the E.D. factory at Island Farm Road, West Molesey. According to Gordon Cornell's recollection, this company was one of E.D.’s established contract suppliers, although their exact previous relationship with E.D. remains obscure. The terms of the contract are also unknown, but they seem to have covered at least the assembly, testing and servicing of the engines. It's entirely possible that the contract went further than this, but we have no hard evidence at present.

To accomplish this objective, they entered into a contract with a precision engineering firm called Bardsley's located at Town Meadows in High Street, Brentford, Middlesex, just a short distance across the River Thames to the north-east of the E.D. factory at Island Farm Road, West Molesey. According to Gordon Cornell's recollection, this company was one of E.D.’s established contract suppliers, although their exact previous relationship with E.D. remains obscure. The terms of the contract are also unknown, but they seem to have covered at least the assembly, testing and servicing of the engines. It's entirely possible that the contract went further than this, but we have no hard evidence at present. It appears that the contract required E.D. to more or less pay as they went - they had to meet all design and development costs as they were incurred. Accordingly, a considerable investment was evidently made in these areas as well as in the production of the necessary dies. All of this work was pressed to the utmost given the time constraints which E.D. felt themselves to be facing.

It appears that the contract required E.D. to more or less pay as they went - they had to meet all design and development costs as they were incurred. Accordingly, a considerable investment was evidently made in these areas as well as in the production of the necessary dies. All of this work was pressed to the utmost given the time constraints which E.D. felt themselves to be facing. E.D. management now found themselves in a trap of their own making - they had made a considerable investment in a project which was apparently failing to meet their expectations and was falling behind schedule, largely due to inadequate project supervision on their part. At this point, they finally did what they should have done at the outset - they brought their own chief design engineer Gordon Cornell into the picture.

E.D. management now found themselves in a trap of their own making - they had made a considerable investment in a project which was apparently failing to meet their expectations and was falling behind schedule, largely due to inadequate project supervision on their part. At this point, they finally did what they should have done at the outset - they brought their own chief design engineer Gordon Cornell into the picture.

The end result of all the above shenanigans was inevitable - the version of the Pep which finally reached the market in late 1959 was a compromise, with a number of design flaws left unresolved. The appearance of the Pep was first announced in the “Motor Mart” feature of the December 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Since this issue actually hit the stands in mid-November, it would seem that E.D. met their self-imposed deadline of making the engine available for Christmas 1959, perhaps cutting a few corners to do so. Somewhat strangely, the “Motor Mart” commentary was not accompanied by an introductory E.D. advertisement for the Pep in the same December 1959 issue.

The end result of all the above shenanigans was inevitable - the version of the Pep which finally reached the market in late 1959 was a compromise, with a number of design flaws left unresolved. The appearance of the Pep was first announced in the “Motor Mart” feature of the December 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Since this issue actually hit the stands in mid-November, it would seem that E.D. met their self-imposed deadline of making the engine available for Christmas 1959, perhaps cutting a few corners to do so. Somewhat strangely, the “Motor Mart” commentary was not accompanied by an introductory E.D. advertisement for the Pep in the same December 1959 issue. of eroding the market share of those competing diesel models was to offer something extra by way of quality and/or performance. As events were to prove, it did neither.

of eroding the market share of those competing diesel models was to offer something extra by way of quality and/or performance. As events were to prove, it did neither. During the early stages of its existence, the Pep was promoted very aggressively by E.D. in a somewhat desperate effort to recover as much as possible of the considerable investment which it undoubtedly represented. It was still the main feature in their advertisement which appeared in the June 1960 issues of both “Aeromodeller” and “Model Aircraft”, six months after its release. Oddly enough, the recently-released Super Fury was not featured in this advertisement (seen at the left) despite the fact that it was the subject of

During the early stages of its existence, the Pep was promoted very aggressively by E.D. in a somewhat desperate effort to recover as much as possible of the considerable investment which it undoubtedly represented. It was still the main feature in their advertisement which appeared in the June 1960 issues of both “Aeromodeller” and “Model Aircraft”, six months after its release. Oddly enough, the recently-released Super Fury was not featured in this advertisement (seen at the left) despite the fact that it was the subject of

Whatever the reason, the result was that E.D. received almost no help at all from the contemporary modelling media in their efforts to promote the Pep. To rub salt in the wound, E.D.'s unaided efforts failed from the start to generate much sales interest in the engine despite their claims to the contrary. In large part this was no doubt due to the fact that by mid-1960 the British small-engine market had become saturated. This was an inevitable consequence of so many manufacturers all targeting the same market niche at the same time. Indeed, few of the 1959/60 crop of British ½A models were to last long in production - the woefully anemic

Whatever the reason, the result was that E.D. received almost no help at all from the contemporary modelling media in their efforts to promote the Pep. To rub salt in the wound, E.D.'s unaided efforts failed from the start to generate much sales interest in the engine despite their claims to the contrary. In large part this was no doubt due to the fact that by mid-1960 the British small-engine market had become saturated. This was an inevitable consequence of so many manufacturers all targeting the same market niche at the same time. Indeed, few of the 1959/60 crop of British ½A models were to last long in production - the woefully anemic  There were also a few of those niggling design issues in the mix as well. Although the conrod material was advertised from the outset as hyduminium, Kevin Richards recalled that his own new example from early 1960 had a phosphor bronze rod which burned off its big end bearing during the running-in process! This was apparently a characteristic failure of the early bronze rods, which Gordon Cornell had recognized immediately when consulted about the Pep project after the fact. The material specification was quickly changed to RR56 aluminium alloy, but a number of engines had reached the market before this change was implemented. The reputation of the engine was not enhanced by this issue.

There were also a few of those niggling design issues in the mix as well. Although the conrod material was advertised from the outset as hyduminium, Kevin Richards recalled that his own new example from early 1960 had a phosphor bronze rod which burned off its big end bearing during the running-in process! This was apparently a characteristic failure of the early bronze rods, which Gordon Cornell had recognized immediately when consulted about the Pep project after the fact. The material specification was quickly changed to RR56 aluminium alloy, but a number of engines had reached the market before this change was implemented. The reputation of the engine was not enhanced by this issue. This brings up yet another oddity with respect to the history of the Pep. Although Gordon had recognized the inadequacy of the Pep conrod well prior to the engine’s introduction (hence his use of a forged aluminium alloy Bee item in his twin ball-race .049 special), and despite the fact that the rod material was initially advertised as being hyduminium, examples from both ends of the Pep production cycle are routinely encountered with bronze rods. Apart from Kevin Richards' previously-noted example from early 1960, my own engine numbers H 2.69B and B. 95C from August 1961 and February 1962 (if my hypothesis regarding serial numbers is correct - see later discussion) both feature bronze rods. In fact, examples with the bronze rod greatly outnumber those with the hyduminium component. Moreover, one of the later Pep advertisements (from May 1962 - left) specifically refers to the con-rod being made of phosphor-bronze.

This brings up yet another oddity with respect to the history of the Pep. Although Gordon had recognized the inadequacy of the Pep conrod well prior to the engine’s introduction (hence his use of a forged aluminium alloy Bee item in his twin ball-race .049 special), and despite the fact that the rod material was initially advertised as being hyduminium, examples from both ends of the Pep production cycle are routinely encountered with bronze rods. Apart from Kevin Richards' previously-noted example from early 1960, my own engine numbers H 2.69B and B. 95C from August 1961 and February 1962 (if my hypothesis regarding serial numbers is correct - see later discussion) both feature bronze rods. In fact, examples with the bronze rod greatly outnumber those with the hyduminium component. Moreover, one of the later Pep advertisements (from May 1962 - left) specifically refers to the con-rod being made of phosphor-bronze. At present, I have no explanation for these inconsistencies other than to suggest that E.D. management may have been completely serious in their insistence that all components manufactured prior to Gordon Cornell's involvement be used. This may have included the bronze rods. It's also possible that a bronze conrod having a more suitable alloy specification was adopted later.

At present, I have no explanation for these inconsistencies other than to suggest that E.D. management may have been completely serious in their insistence that all components manufactured prior to Gordon Cornell's involvement be used. This may have included the bronze rods. It's also possible that a bronze conrod having a more suitable alloy specification was adopted later. However, since this post-dated the April 1962 arson fire which brought the original E.D. company to its knees, it seems certain that by that time the company was simply selling off existing stocks of the engine. As far as can be ascertained today, the bulk of Pep production took place in relatively small batches during the years 1960 and 1961, with perhaps one small batch being produced in early 1962 (see further discussion below).

However, since this post-dated the April 1962 arson fire which brought the original E.D. company to its knees, it seems certain that by that time the company was simply selling off existing stocks of the engine. As far as can be ascertained today, the bulk of Pep production took place in relatively small batches during the years 1960 and 1961, with perhaps one small batch being produced in early 1962 (see further discussion below). It should be clear from the above account that the commercial failure of the Pep must have left a bad taste in a few mouths. One of those mouths undoubtedly belonged to Gordon Cornell. A number of fundamental problems within the E.D. company had by now become painfully apparent to Gordon, and his consequent frustration levels had undoubtedly been elevated by being tasked with getting the Pep to perform at a stage when it was already too late to do anything meaningful about its problems. There were also the issues of management inertia with respect to both his proposed twin ball-race .049 diesel and his very promising

It should be clear from the above account that the commercial failure of the Pep must have left a bad taste in a few mouths. One of those mouths undoubtedly belonged to Gordon Cornell. A number of fundamental problems within the E.D. company had by now become painfully apparent to Gordon, and his consequent frustration levels had undoubtedly been elevated by being tasked with getting the Pep to perform at a stage when it was already too late to do anything meaningful about its problems. There were also the issues of management inertia with respect to both his proposed twin ball-race .049 diesel and his very promising

It was at this point that Jim Donald introduced Gordon to a certain Alan Dye to discuss the possibility of E.D. undertaking alternative engine production such as chainsaw engines. Unfortunately for Gordon, Alan Dye was basically a smooth talker who was looking to create a work opportunity for himself - he was in fact nothing more than a competent draughtsman, although he evidently presented himself as something more. He persuaded Gordon to leave E.D. to join his company Dydesyne Ltd. of Slough in Buckinghamshire to produce what became Gordon's legendary Dynamic .049 twin ball-race diesel.

It was at this point that Jim Donald introduced Gordon to a certain Alan Dye to discuss the possibility of E.D. undertaking alternative engine production such as chainsaw engines. Unfortunately for Gordon, Alan Dye was basically a smooth talker who was looking to create a work opportunity for himself - he was in fact nothing more than a competent draughtsman, although he evidently presented himself as something more. He persuaded Gordon to leave E.D. to join his company Dydesyne Ltd. of Slough in Buckinghamshire to produce what became Gordon's legendary Dynamic .049 twin ball-race diesel.

.049 model to be called the Tutor, the bailiffs turned up unannounced one morning, putting an end to the very promising Dynamic .049 project, killing the Tutor and leaving Gordon high and dry. Only some 20 or so examples of the Dynamic .049 ended up being competed, along with perhaps half-a-dozen examples of the Tutor in both beam and radial mount configurations.

.049 model to be called the Tutor, the bailiffs turned up unannounced one morning, putting an end to the very promising Dynamic .049 project, killing the Tutor and leaving Gordon high and dry. Only some 20 or so examples of the Dynamic .049 ended up being competed, along with perhaps half-a-dozen examples of the Tutor in both beam and radial mount configurations.  No doubt the members of the E.D. Board of Directors as well as their bankers acquired a highly negative view of the Pep given the financial drain upon the company coffers which it must have represented. It seems highly unlikely that E.D. ever came close to recovering their investment in this model, which doubtless contributed towards E.D.'s rapidly-accelerating slide towards marginalization in the British model engine manufacturing field. Given its very low price, only mass sales could have turned the engine into a financial winner, and the Pep never came close to reaching that status.

No doubt the members of the E.D. Board of Directors as well as their bankers acquired a highly negative view of the Pep given the financial drain upon the company coffers which it must have represented. It seems highly unlikely that E.D. ever came close to recovering their investment in this model, which doubtless contributed towards E.D.'s rapidly-accelerating slide towards marginalization in the British model engine manufacturing field. Given its very low price, only mass sales could have turned the engine into a financial winner, and the Pep never came close to reaching that status. engine was of course obtained second-hand, as were most of my engines at the time (I was still attending Grammar School in England), but I bought it not as a collector's item (a status which model engines had yet to acquire in those far-off days for all but a few prescient individuals) but as a useable engine that was available at a good price. Unfortunately, I never recorded its serial number.

engine was of course obtained second-hand, as were most of my engines at the time (I was still attending Grammar School in England), but I bought it not as a collector's item (a status which model engines had yet to acquire in those far-off days for all but a few prescient individuals) but as a useable engine that was available at a good price. Unfortunately, I never recorded its serial number. Far more recently, I learned that one of my compatriots in my latter-day Western Canadian model club (an ex-patriate British resident like myself) had also owned a Pep way back - in fact, he had received his example brand new as a birthday gift from his parents in 1961! It was his first model engine, which he used both to learn how to operate a model diesel engine and to power a series of models during the period when he was just getting started. He too has nothing but positive memories of the engine, including the fact that it seemed to him to be well up to par with other competing British productions at the time.

Far more recently, I learned that one of my compatriots in my latter-day Western Canadian model club (an ex-patriate British resident like myself) had also owned a Pep way back - in fact, he had received his example brand new as a birthday gift from his parents in 1961! It was his first model engine, which he used both to learn how to operate a model diesel engine and to power a series of models during the period when he was just getting started. He too has nothing but positive memories of the engine, including the fact that it seemed to him to be well up to par with other competing British productions at the time. Cylinder porting is essentially conventional, following the OK Cub pattern exactly. Three sawn slits form the exhaust ports, while three small holes are drilled at an upward angle through the pillars which separate the exhaust ports. These holes function as the transfer ports. This arrangement allows for a small degree of overlap between the exhaust and transfer ports, yielding a reasonably generous transfer period without the need to open the exhaust ports unduly early. There is no supplementary sub-piston induction. The flat-topped piston and matching contra-piston are both of cast iron, being very well fitted indeed on my two examples.

Cylinder porting is essentially conventional, following the OK Cub pattern exactly. Three sawn slits form the exhaust ports, while three small holes are drilled at an upward angle through the pillars which separate the exhaust ports. These holes function as the transfer ports. This arrangement allows for a small degree of overlap between the exhaust and transfer ports, yielding a reasonably generous transfer period without the need to open the exhaust ports unduly early. There is no supplementary sub-piston induction. The flat-topped piston and matching contra-piston are both of cast iron, being very well fitted indeed on my two examples.