|

|

Feltham Fliers - the Rivers Engines

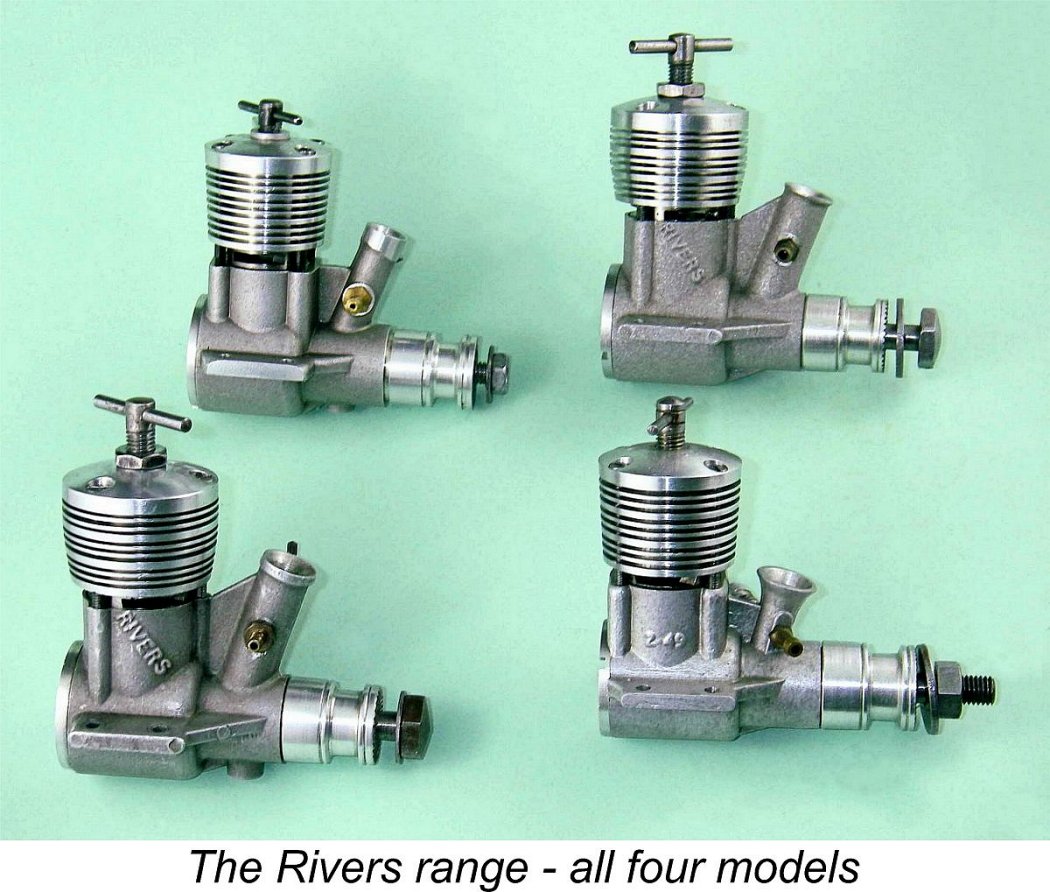

My original article on the Rivers engines appeared on the late Ron Chernich’s fascinating “Model Engine News” (MEN) website in June 2012. However, my mate Ron left us in early 2014 without sharing the access codes for his heavily-encrypted site. Because no maintenance has since been possible, the MEN site is slowly but perceptibly deteriorating - an inevitable process which can have only one ending in the long run. I was unwilling to risk the loss of the information so painstakingly assembled on the widely-respected Rivers range, hence the article’s re-publication here. When I started the original version of this article back in late 2011, I was expecting it to be a relatively straightforward task. After all, we're talking about a company that supposedly made only two versions each of two model diesels - four variants in all, and over a relatively short period of time at that. Moreover, the engines were well advertised and discussed in the modelling media of their day. How much simpler can you get? Accordingly, I began this review as a welcome break from the more complex subjects that I'd tackled for previous issues of MEN. Little did I know ............... During the course of my research, I circulated a routine request for information on serial numbers. So much for happy expectations of an easy ride! I was frankly overwhelmed by the number and range of responses received to this initial request, going far beyond the simple provision of serial numbers to encompass various aspects of the engines' design as well as the issue of model identification. It seems that interest in the Rivers engines runs unusually high, together with a wide range of strongly-held opinions, many of them contradictory. Sorting out all this material became a genuinely daunting task - indeed, for a while there the data flowed in faster than I could assimilate it! Still, I persevered in the hope that the end result might be viewed as being worth the sweat that it cost.

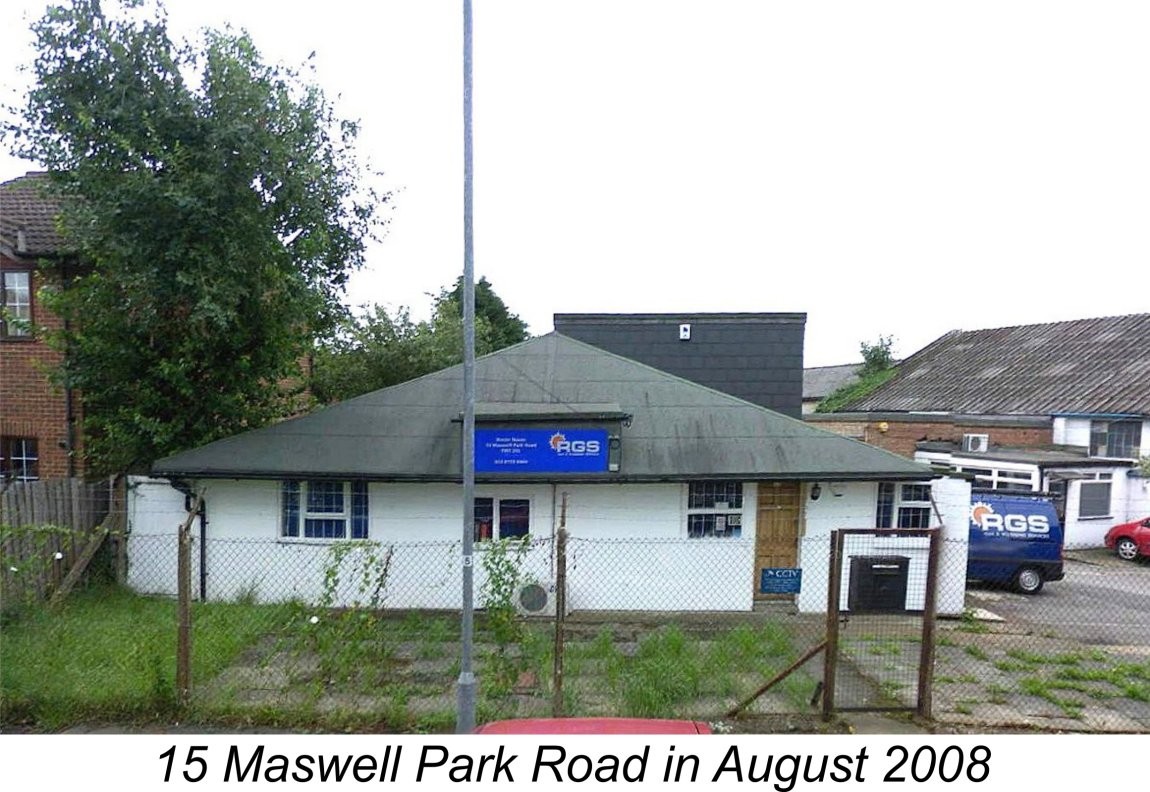

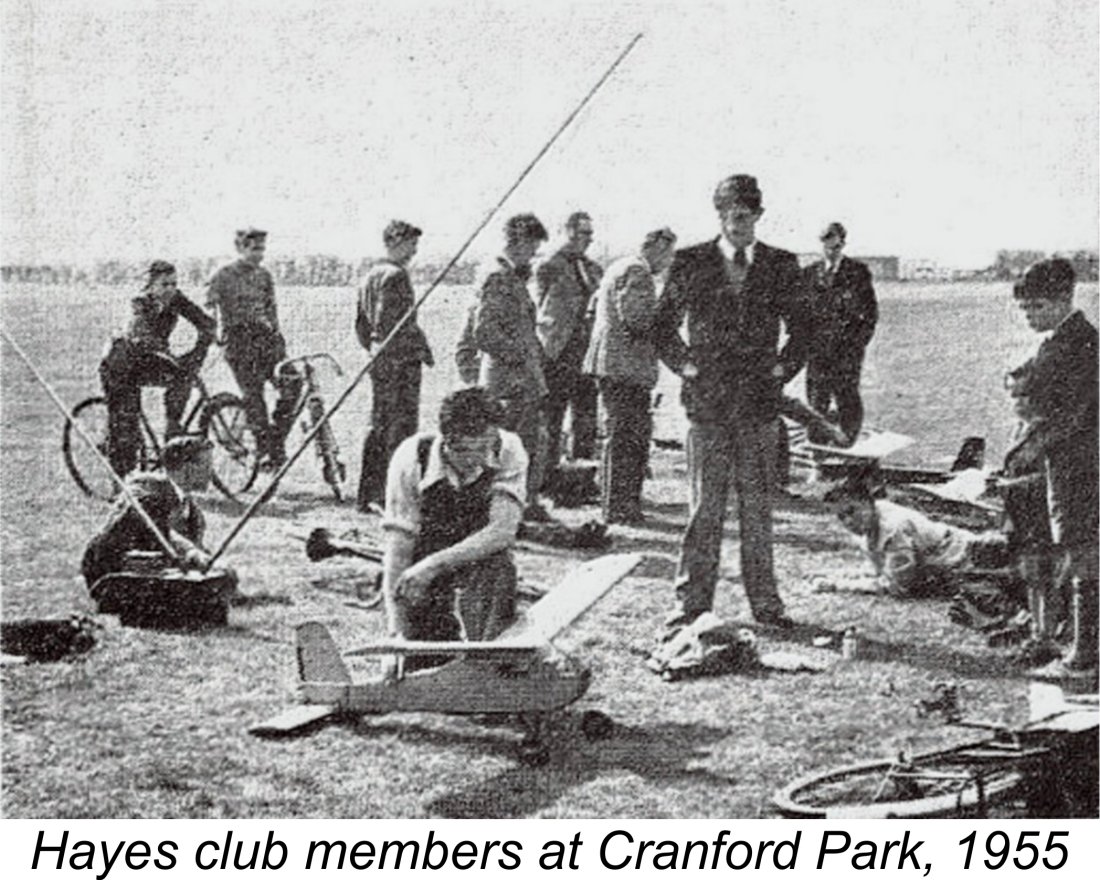

Although thanks are due to everyone who helped in the gathering of material for this article, I would particularly like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of the late Ian Russell, well-known for his excellent series of "Rustler" replicas of notable engines from the past. As an active member of the Hayes & District Model Aero Club during the period when the Rivers engines were being developed, Ian was privileged to be among those who participated in the field testing of the locally-produced Rivers models. In consequence, he became personally acquainted with Bert Rivers and his son Graham (also a Hayes club member) as well as being privy to much of the company's ongoing development work. I'm greatly indebted to Ian for so generously sharing his recollections. I must also make special mention of Jon Fletcher, Maris Dislers, Brian Cox and the late David Owen. All four of these gentlemen went well beyond the limits of my original request for serial numbers, generously sharing their insights into various aspects of the design and production of the Rivers range. I'm very grateful to all of them. I also wish to acknowledge the assistance of Eric Offen, Charlie Stone and the late Bert Striegler for assisting with the collection of serial numbers and other data. Finally, MEN’s late and much-missed Editor Ron Chernich gave freely of his time in searching out reference material to which I didn't have access. Thanks to one and all, including those whom I didn't mention by name - you all know who you are! The initial publication of this article did nothing to slow down the ongoing inflow of information - I’d merely opened the floodgates! Ian Russell contacted a number of his former Hayes clubmates to advise them of the article's publication. As a result, additional first-hand information was supplied by such Hayes luminaries as Dave Balch, Robin and Brian Greenaway and Andrew Longhurst - all guys who were "there" during the brief period when Rivers ruled the roost. It was great to have direct contact with individuals who were modelling superstars during my formative years as an aeromodeller! Ron and I were also delighted to receive additional information from MEN readers at large including Jerry Zierdt, who supplied several useful serial numbers. As a result of all this interest, what had been expected to be a short ‘n sweet write-up on a relatively straightforward subject metamorphosed into the longest and most convoluted article that I've ever written. Moreover, the article has had to be significantly updated several times following its original publication. That being the case, I'd better get right to it! As always, I'll begin by summarising the background to the Rivers story. Background The Rivers engines were developed by the firm of A. E. Rivers, a precision engineering company giving its original address as 15 Maswell Park Road in Hounslow, Middlesex. Hounslow is a suburb of Greater London lying on the north bank of the River Thames some miles to the south-west of the City. It is geographically quite close to the successive haunts of Electronic Developments Ltd, just across the river at Kingston-on-Thames, West Molesey and Surbiton. Other model engine manufacturers located in the area at various times included Allbon Engineering at nearby Sunbury-on-Thames, International Model Aircraft (FROG) a little to the south-east across the river at Morden, and Mills Brothers to the south-west at Woking. Model engine manufacture was a well-established business in south-west London!

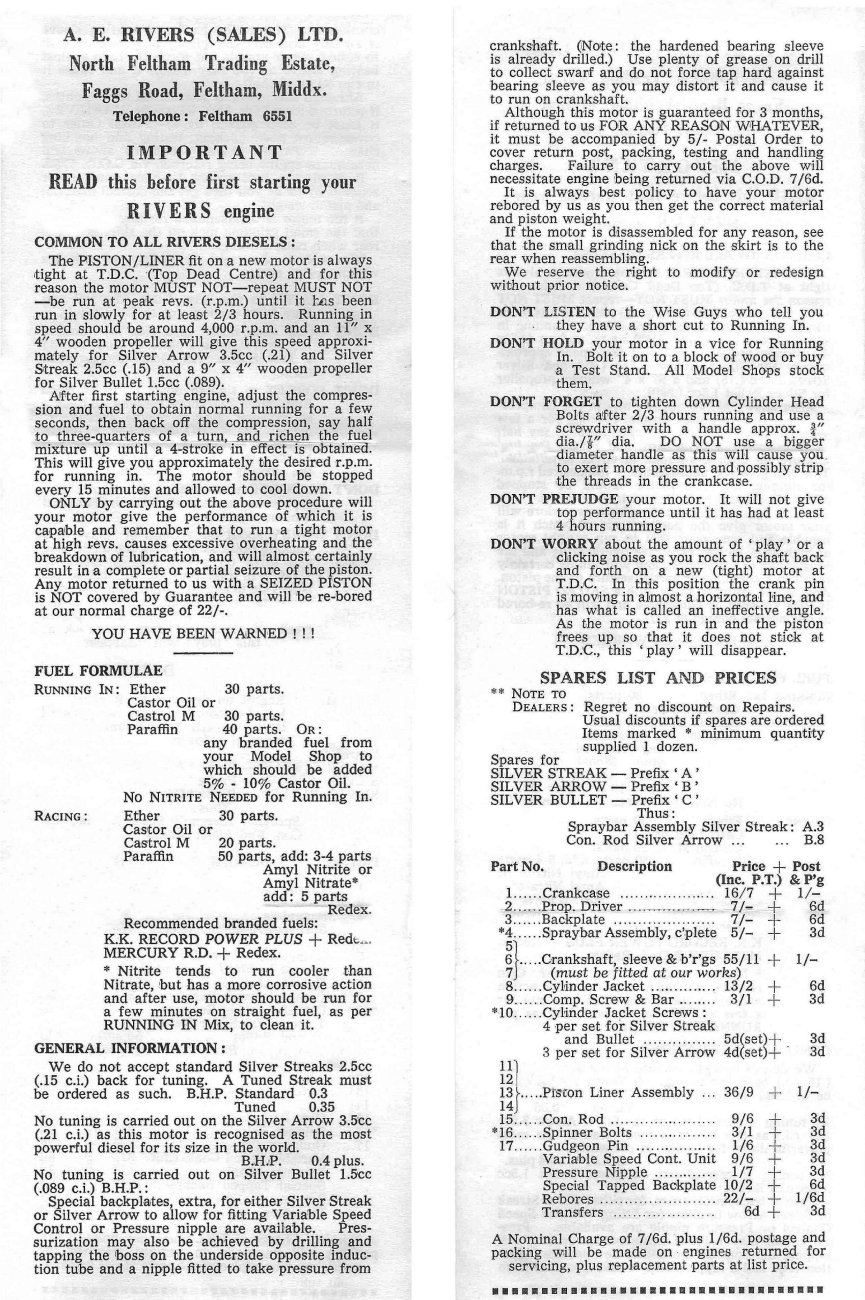

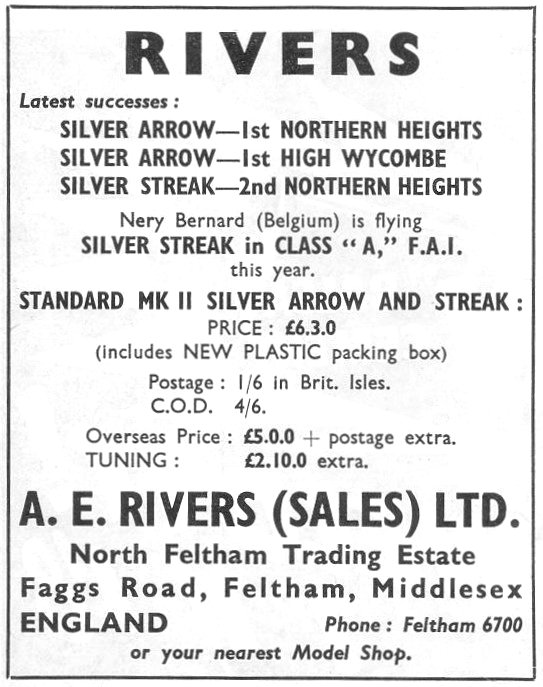

It appears from this that the site has remained in continuous industrial use since the time of the Rivers occupancy. However, this location clearly proved inadequate for Rivers' needs as their business expanded, since by August 1960 the company was trading from a new address on Faggs Road in the North Feltham Trading Estate at nearby Feltham, Middlesex. The Faggs Road area remains a centre of industrial activity today.

As of the late 1950's the British Government of the day started sending clear signals that it wished to see a major reorganization of Britain's aircraft industry. This was to lead to Fairey Aviation Ltd. first being reorganized as the Fairey Aviation Co. Ltd. in April of 1959, followed in 1960 by its absorption into the Westland Aviation group. It may well have been the uncertainties created by this developing situation that led to the Rivers company deciding to diversify by branching out into model engine manufacture. Even so, it appears more than likely that the company continued at least at the outset to engage in contract precision engineering work rather than putting all of its eggs into the model engine basket.

Although Bert Rivers seems to have been the principal designer of the Rivers engines, there's no doubt that Graham must have been at least instrumental in stimulating Bert's interest in the project as well as having some influence over its design. Graham was certainly one of the field testers - prototypes began appearing in his hands at meetings of the Hayes club in the latter part of 1958.

Bert's response was that through his attendance at a number of major contests he had come to the conclusion that he didn't have to beat the entire field of Olivers - he was really only competing with the top 3 or 4 teams who Ian Russell retained some very clear memories of his encounters with Bert Rivers. Among other things, he recalled that Bert drove a Mk. 1 Jaguar saloon with the narrow back axle, which apparently did nothing for the car's road holding qualities. Bert would sometimes convey one or two of the Hayes club members to various rallies in this vehicle. On one occasion, while belting down a hill into Wycombe on the way to the High Wycombe rally, they could feel the back end hopping around to an alarming degree. This prompted the question "Have you ever noticed a problem with road holding?" "Oh no - never!" Bert replied cheerfully, putting his foot down even harder! Clearly a man who met life on his own terms………………. Design Considerations

It was the latter feature which really set the Rivers design apart. Most contest diesels of this type used ball races at both ends of the crankshaft. While these were fairly effective both in absorbing radial loadings and end-thrust loadings, they had to be in perfect alignment to be completely effective. Moreover, they had the disadvantage that the internal diameter of the rear ball race limited the shaft's main journal diameter. As designers strove for more power through the use of larger internal gas passages and induction ports in the shaft, crankshaft strength became an increasingly serious issue, particularly at the induction port location. Peter Chinn devoted a significant section of his June 1959 "Latest Engine News" column in “Model Aircraft” magazine to a discussion of this growing problem.

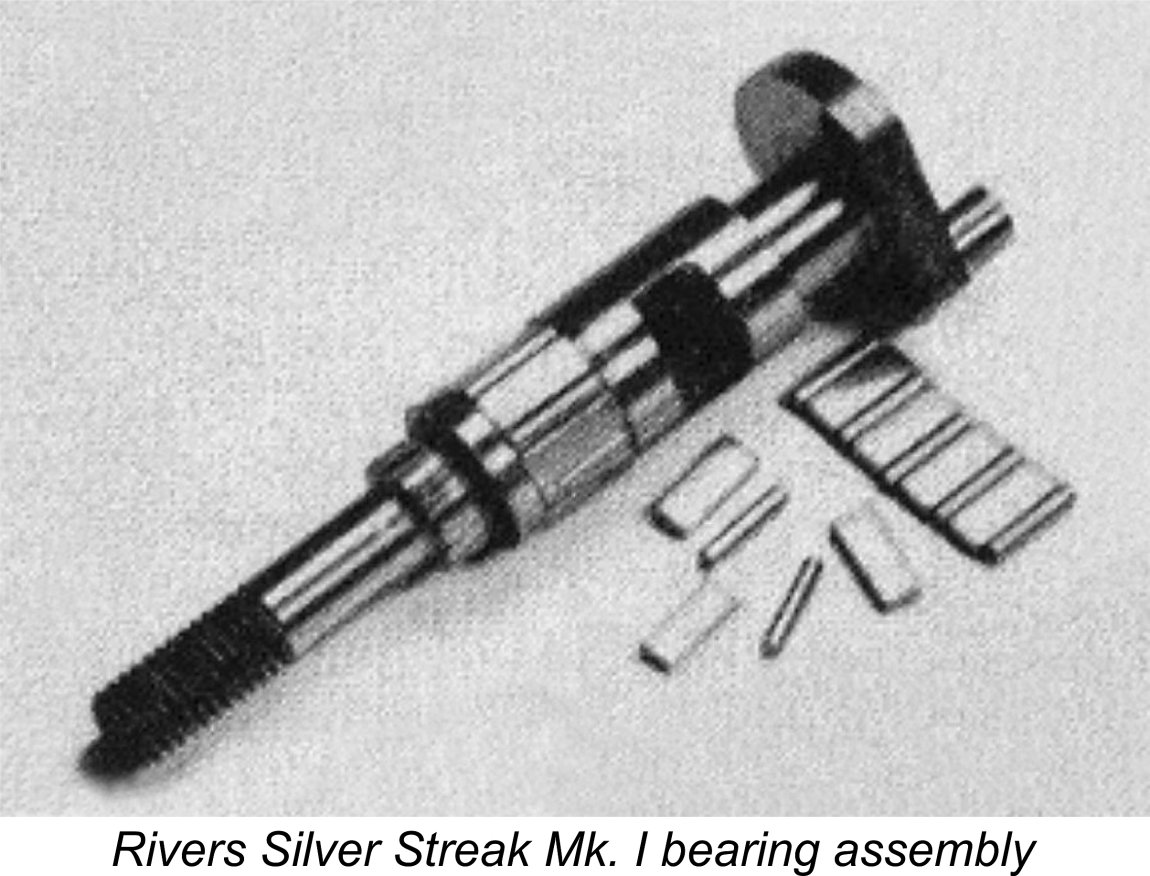

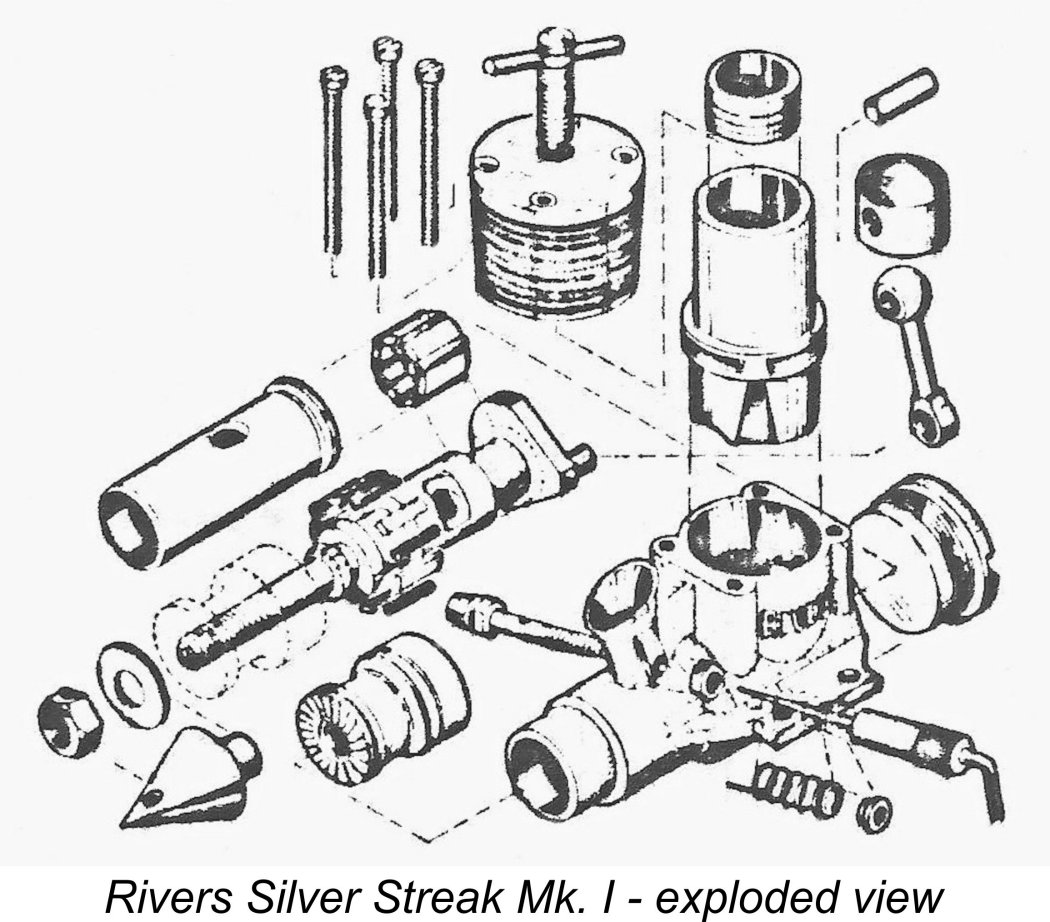

Discussions between Peter Chinn and the Rivers designer confirmed that their crankshaft configuration was a direct response to the issue of crankshaft strength at the induction port location. The Rivers design attacked this problem in a unique way by using a pair of uncaged needle roller bearings, with the rollers operating in direct contact both with their respective crankshaft journals and with the main bearing journal. Each bearing incorporated Since the needle rollers were externally caged only by the internal wall of the main bearing sleeve, they did not have to be slid in an assembled state along the main crankshaft journal as in the case of a ball bearing or caged needle roller bearing but could be assembled in their operating locations prior to installation of the shaft in its bearing. Accordingly, the journal between the two needle roller bearings could be expanded to nominally the same outer diameter as the needle roller bearings when assembled. The design of the Rivers Silver Streak Mk. I took full advantage of this. The shaft featured two lengths of reduced diameter at the bearing locations, into which the needle rollers and their spacers were assembled prior to installation of the shaft. The result was a shaft having needle roller bearings at each end with a plain bearing section in the middle having the same nominal outer diameter as the assembled needle roller bearings. This entire assembly was slid into a hardened steel sleeve which was ground to a constant internal diameter to serve as the main bearing for the composite shaft over its entire length. The outer diameter of the two needle roller bearing journal lengths in the crankshaft was a respectable 0.350 in. (8.89 mm). Although this was a little less than the diameters achieved in some ball race designs, it was not greatly so. More importantly, the fact that these two lengths of shaft were not weakened by the presence of an induction port greatly increased strength at these locations by eliminating the tendency towards the development of stress concentrations which inevitably accompanies the presence of a crankshaft induction port in the main journal.

Of greater significance in a performance context was the fact that the unusually large journal diameter at the induction port gave rise to a very high annular surface speed at a given rate of rotation. This in turn significantly reduced the time taken up by the opening and closing of the induction port, allowing for very precise timing. Moreover, the annular length of the crankshaft induction port was necessarily greater for a given opening period, being formed by cross-milling. All of this promoted a longer fully-open dwell period for the induction system - a great benefit to higher performance. All sounds great, doesn't it? Well, now for a healthy dose of heresy - there were a number of definite downsides to this bearing design. First and foremost, it was clearly very expensive to manufacture. Makers of ball-race diesels could simply buy their bearings in job lots from specialist bearing manufacturers. Not so with the Rivers - the needle roller bearings for each engine had to be individually manufactured and fitted to extremely fine tolerances. You might want to have a calculator handy to follow this next bit! The manufacturers stated that the rollers themselves were ground 1.5 mm (0.0591 in.) diameter items. These were mated to nominally 0.350 in. (8.89 mm) dia. journals which were themselves ground to limits of minus two tenths of a thousandth of an inch (0.0002 in. or 0.0051 mm). This resulted in an external diameter of the assembled bearing of 0.4682 in. with a minus 0.0002 in. tolerance. The internal diameter of the steel main bearing sleeve was ground to 0.4684 in., giving the needle roller bearings a running clearance of 0.0002 in. at a tolerance of minus "two tenths", which was apparently considered ideal. At the induction port location, the crankshaft journal was ground to 0.4682 minus 0.0004 in. - 0.0006 in., thus ensuring that the assembled rollers stood proud of the central plain bearing journal section by some 0.0002 in. It will be seen from all of this that the manufacture of the Rivers engines involved precision grinding of a very high order indeed as well as extremely close attention to manufacturing tolerances. Not a challenge that most commercial model engine manufacturers hoping to make a profit would care to take up!

A further issue was the fact that, generally speaking, friction losses in needle roller bearings in applications of this sort tend to be substantially higher than with good-quality ball races. This is due in large part to the increased viscous drag arising from the presence of lubricant. The needle rollers have to overcome the drag exerted by an oil film extending the full length of the bearing - a far greater area than that for a ball bearing with its spot contact as opposed to the line contact of the needle rollers. The spacers used in the Rivers design would have made a significant further contribution to this problem. Over-lubrication is actually a recognized problem with needle roller bearings, a condition that is very likely to arise in a model engine given the relatively high oil contents in the fuel. Furthermore, while the Rivers needle roller bearings doubtless did a good job of absorbing the radial loadings to which the crankshaft was subjected, they did absolutely nothing to assist with the thrust loadings generated during operation. In that respect, the engines were no better than a plain bearing model. In fact, it's likely that for all its complexity and cost of production, the Rivers shaft design was little better than a good-quality plain bearing at higher speeds, although the engines certainly felt delightfully "free" when turned over by hand at rest. While not themselves ideal in this application, ball-races almost certainly do a better job overall in a high-speed application such as this when under load. It was doubtless the recognition of this characteristic that led Giovanni Barbini to adopt a roller bearing/ball race combination in his 2.5 cc Barbini B40 competition diesel. The final downside of the use of the type of bearing employed was the indisputable fact that cleanliness was absolutely paramount if the roller bearings were to be maintained in good condition. Given the clearances involved, it's obvious that the intrusion of even the smallest particulates could result in skidding and/or scoring of the needle rollers. The presence of particulates in the lubricant is recognized as the leading cause of wear in needle roller bearings. It might accordingly be expected that use of these engines in environments such as control line combat in which dirt ingestion was a potential issue would be highly inimical towards long life. The front bearing would be particularly susceptible to such problems. For all of the above reasons, I am one of those heretics (and I'm not alone) who see the Rivers twin roller bearing arrangement as a handicap in performance terms. I believe that the optimum set-up would have been the Rivers needle roller bearing at the rear and a quality ball-race at the front, with the thrust loadings being absorbed by the ball-race. This was the system adopted very successfully by Barbini with his B40 design. Such an arrangement would have permitted the retention of the large diameter journal at the induction port location. It would have dealt far better with axial loadings while providing outstanding radial support to the shaft at the point of its greatest radial load. As we shall see later, there is evidence to suggest that Rivers themselves eventually came round to this point of view, at least in part. The Rivers Silver Streak Mk. I

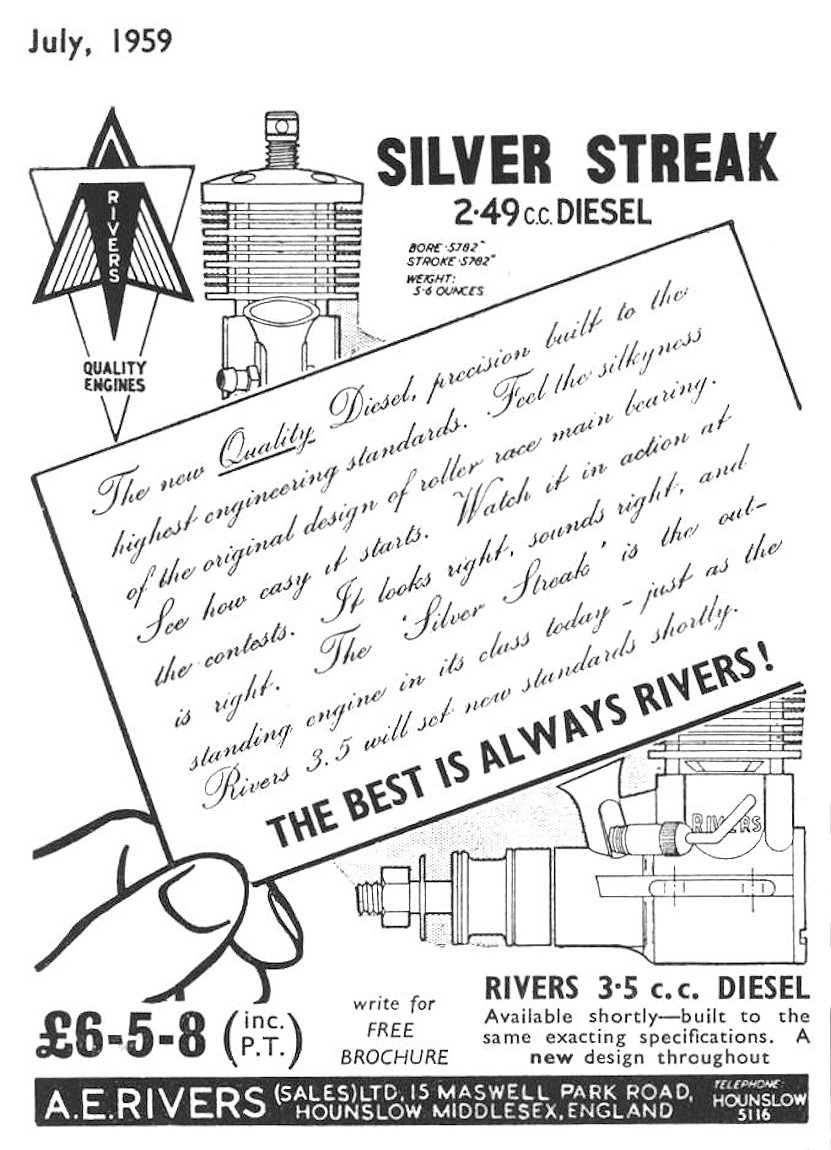

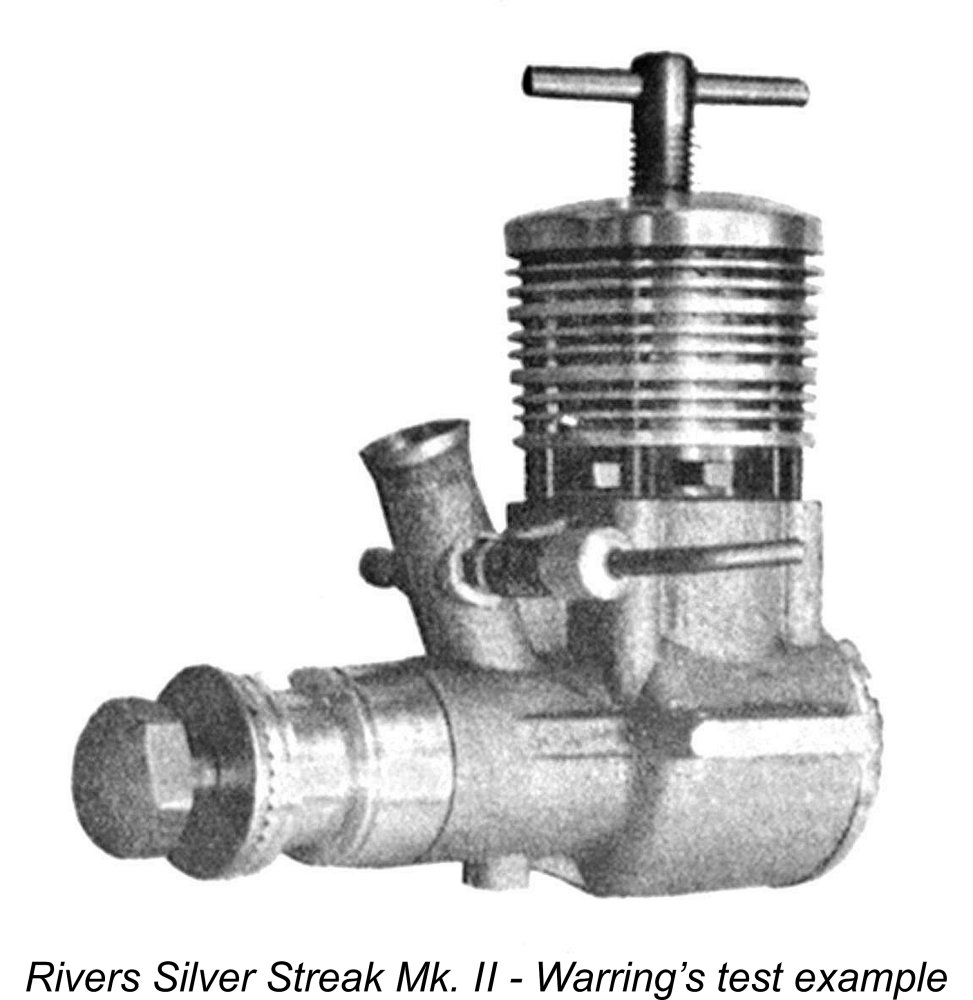

Bore and stroke of the Rivers Silver Streak were identical at 0.5782 in. (14.686 mm) apiece for a displacement of 2.49 cc (0.152 cuin.). The engine weighed in at a relatively healthy 5.85 ounces (166 gm), a fair proportion of which was in the crankshaft/main bearing assembly. This was another disadvantage of the bearing design - it made higher-than-average weight inevitable. Although not excessive by today's standards, this was a pretty substantial weight for a 2.5 cc diesel at the time.

The piston and contra-piston were both machined from high-grade Meehanite cast iron. Somewhat unusually, the contra-piston featured three annular grooves around its external circumference into which was packed molybdenum disulphide grease prior to assembly. This was presumably intended to promote smooth operation of the compression control, particularly during the break-in process. The con-rod was machined from DTD 363 alloy. A praiseworthy feature was the very generous small end length incorporated in the rod. In conjunction with a lightly press-fitted gudgeon pin, this might be expected to give excellent con-rod life. The aluminium alloy backplate was of the conventional screw-in variety. In order to provide clearance for its installation, a shallow arc of material was machined away at the base of the cylinder liner beneath the rear exhaust port. This had the benefit of ensuring that if the engine was ever dismantled, it could only be re-assembled with the cylinder in the same orientation as before. Somewhat confusingly, the exploded view provided with the instruction leaflet which is reproduced above showed the relieving arc at the base of the lower liner placed at the front rather than the rear - a potential trap for those not familiar with model engine assembly!

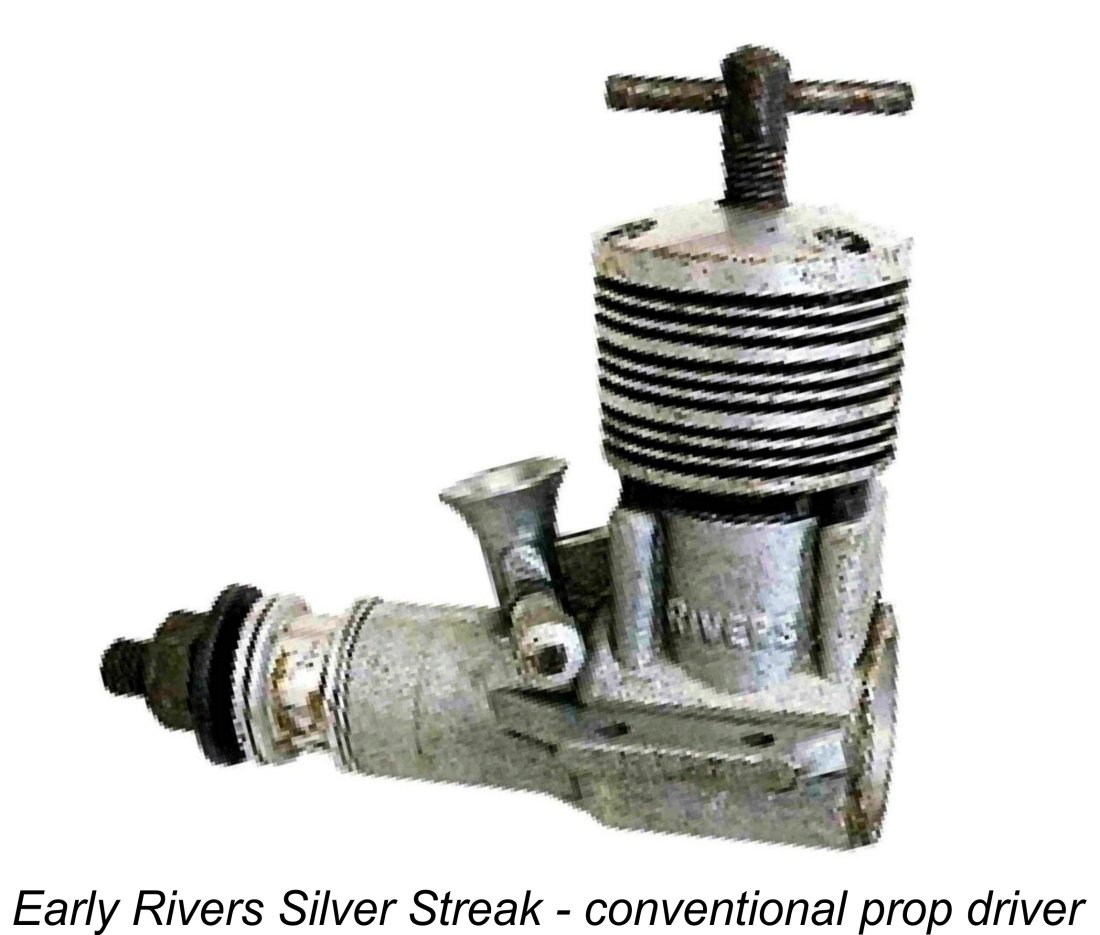

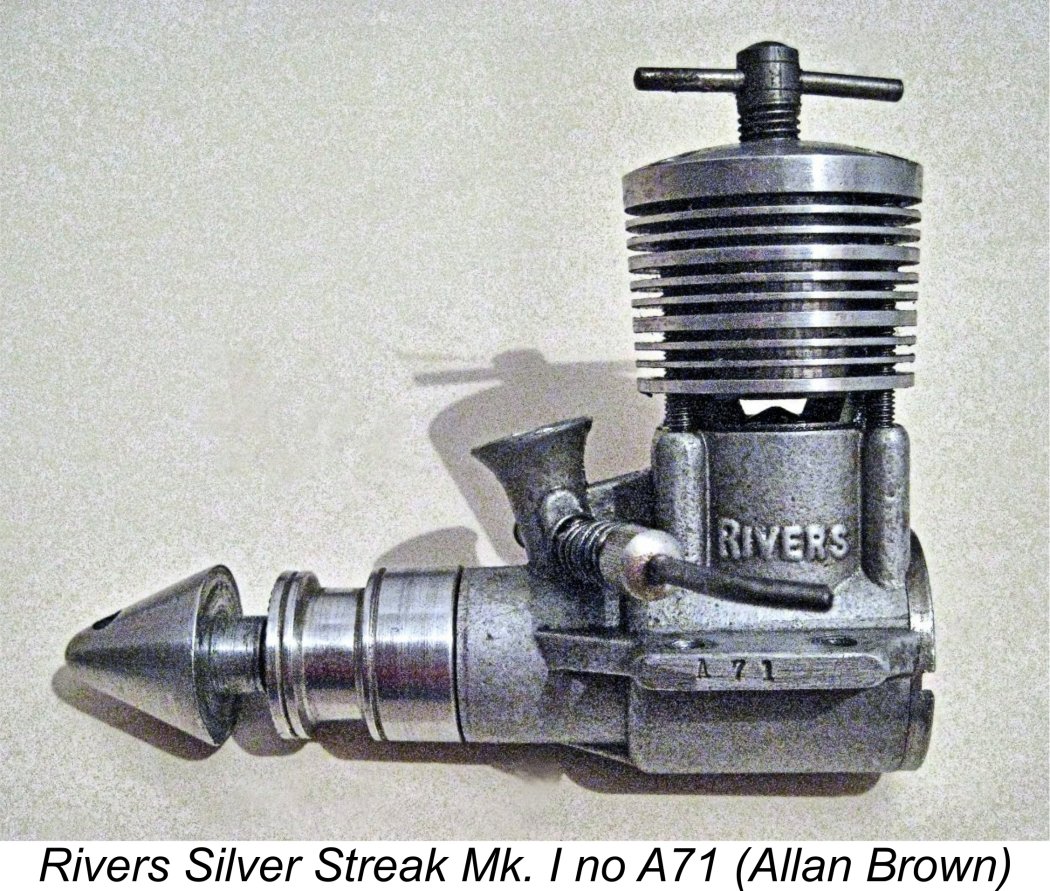

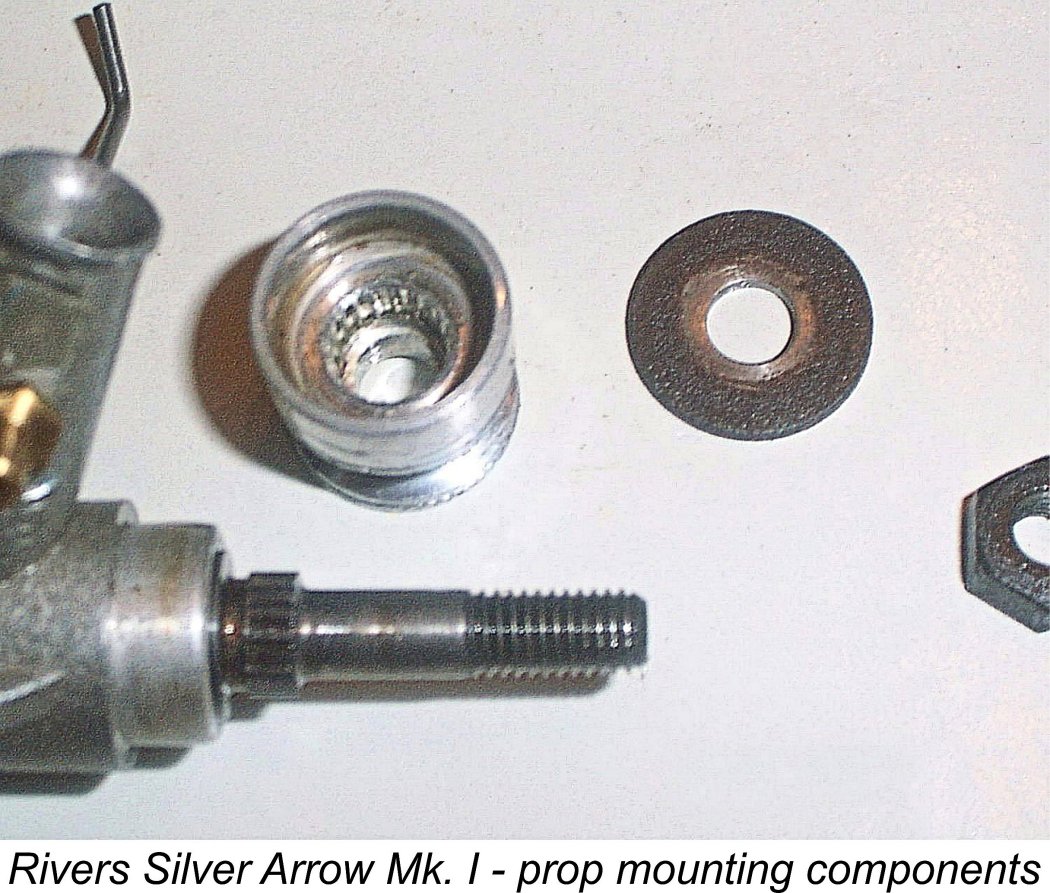

The design progression of the prop mounting system clearly demonstrated the manufacturers' early appreciation of the need to prevent the ingress of foreign material into the engine's main bearing assembly. A few of the very earliest Silver Streaks used a conventional prop driver which was secured on splines, simply butting up against the front of the main bearing with a small amount of end float to provide operating clearance. This of course left the front needle roller bearing exposed to the ingress of dirt as a result of crashes or operation in dusty conditions. The manufacturers clearly became aware of this issue very early on, since a change was quickly made to a prop driver of the wrap-around type. This incorporated a recess at the rear which enclosed a ¼ in. long section of the main bearing housing at the front. This section of the housing was machined down to an external diameter of 0.625 in. to accommodate the driver. There was thus little chance of dirt entering the The engine was completed by a needle valve assembly of more or less conventional form. A brass spraybar was used in conjunction with an aluminium alloy thimble which was tensioned with a coil spring. Appropriately enough given the engine's primary intended application for control line service, the needle was angled back to the left (facing forward in the direction of flight), thus facilitating sidewinder mounting and also placing the needle very conveniently when the engine was mounted in an inverted orientation, as it generally would be in a team racer. Most (but not all) of the Rivers engines bore serial numbers, generally (but not invariably) stamped on the outer edge face of the left-hand mounting lug. Indications are that the numerical sequence for the Silver Streak started at engine number 1 and continued uninterrupted through the changes that produced the Mk. II model (see below). An A prefix appeared in conjunction with the Mk. I engine's serial number. On the very earliest examples, it appears that the mounting lugs were not machined in any way. In addition, I noted previously that these early engines lacked the wrap-around prop driver of the later Just to really confuse the issue, Allan Brown's Mk. I Rivers no. A71 has the wrap-around driver! The implication is that all of the non-wrap-around examples were part of the initial pre-release stock build up and the wrap-around driver was added during the completion of that batch. Later examples had the undersides of their mounting lugs machined flat to provide a more secure mounting. The outer edges of the lugs were also machined. In addition, the wrap-around prop driver was added to all examples. These changes become universal by the time we reach previously-illustrated engine number A146. For clarity during later discussions, it seems appropriate to refer to this variant as the Rivers Silver Streak Mk. Ib. From the outset, the Silver Streak was also made available in a "works tuned" version, albeit at a premium price of £8 17s 2d (£8.86 nowadays). Such units featured a certain amount of hand-finishing of the induction and transfer porting along with an enlarged 0.240 in. dia. central gas passage in the main shaft. The enlarged gas passage had to be created during the original manufacturing process prior to heat treatment and fitting of the needle roller bearings, which meant that the tuned version of the engine was in fact a distinct production - the company specifically noted that they could not accept standard engines for after-sales tuning and that tuned engines had to be ordered as complete new units direct from the factory. The resulting unit was substantially faster than the standard motor, at the possible cost of a degree of increased fragility. The letter T was added as an extra prefix to the serial number to identify these tuned models. Engine number TA735 is a reported example of this type. I’m also aware of engine number A325T, showing that the letter T sometimes appeared as a suffix on the tuned examples. The highest number of which I'm aware for this model is A769 supplied by Miles Patience. The standard needle roller bearing assembly used in these engines was in fact a simplified version of a previously-developed patented Rivers needle roller bearing design in which a combination of balls and needle rollers was employed. This more complex bearing used a larger number of smaller-diameter rollers which were separated by rows of balls rather than by steel spacers. A single spacer was retained, mainly to prevent skewing of the rollers. The balls were a clearance fit in the bearing, the result being that the applied load continued to be carried entirely by the rollers. The advantage of this design was reduced viscous drag and friction within the bearing during operation, although assembly in a model engine must have been a nightmare. Regardless, bearings of this type had reportedly been used successfully in a number of the prototype engines and could be supplied to order with the tuned version of the Silver Streak, albeit at a further additional cost. As one might expect from the earlier comments regarding the engine's design and construction, workmanship throughout was of an extremely high order. Indeed, it had to be given the nature of the design. The question now was - how effectively did all of this care and effort translate into performance? The model engine testers of the day were all ready to answer that question. The Rivers Silver Streak Mk. I On Test

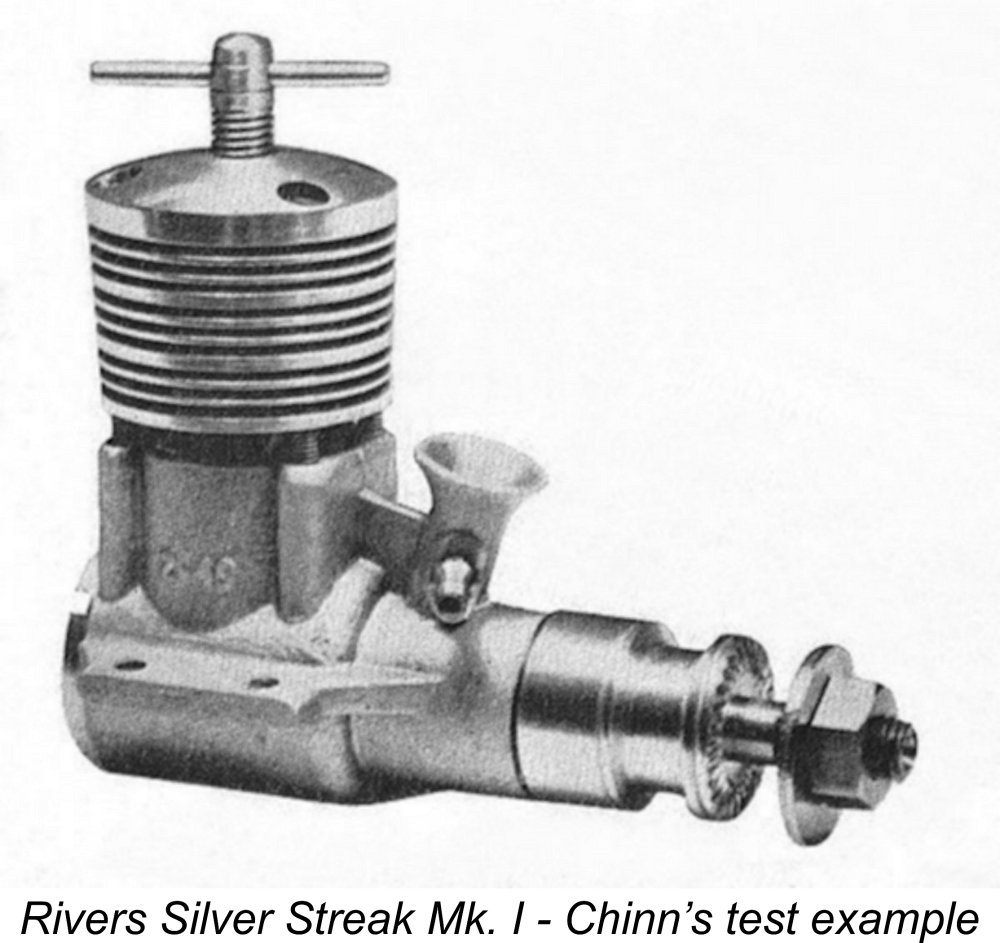

The variant tested by Warring was a Mk. Ib variant featuring the wrap-around prop driver, proving that it was in fact a refined production model with a serial number above A127 as opposed to a prototype or an early production unit. This implies that the company had been very quick indeed to make the changes which resulted in the Mk. Ib variant, quite probably during the pre-release stock build-up which routinely preceded the announcement of any new model for which brisk sales were anticipated. Warring was generally extremely complimentary regarding the engine. He praised the standard of workmanship to the skies, characterizing it as "of the highest order and generally better than that found on normal production engines". In fact, he went so far as to state outright that the Silver Streak was "manufactured to some of the highest standards we have come across in the modelling world". He commented at length on the very close limits to which the engine was constructed, noting that this gave rise to a need for a longer-than-usual running-in period. The manufacturers stated that a running time of some 5-6 hours was generally necessary for maximum performance to be achieved, a recommendation which Warring endorsed.

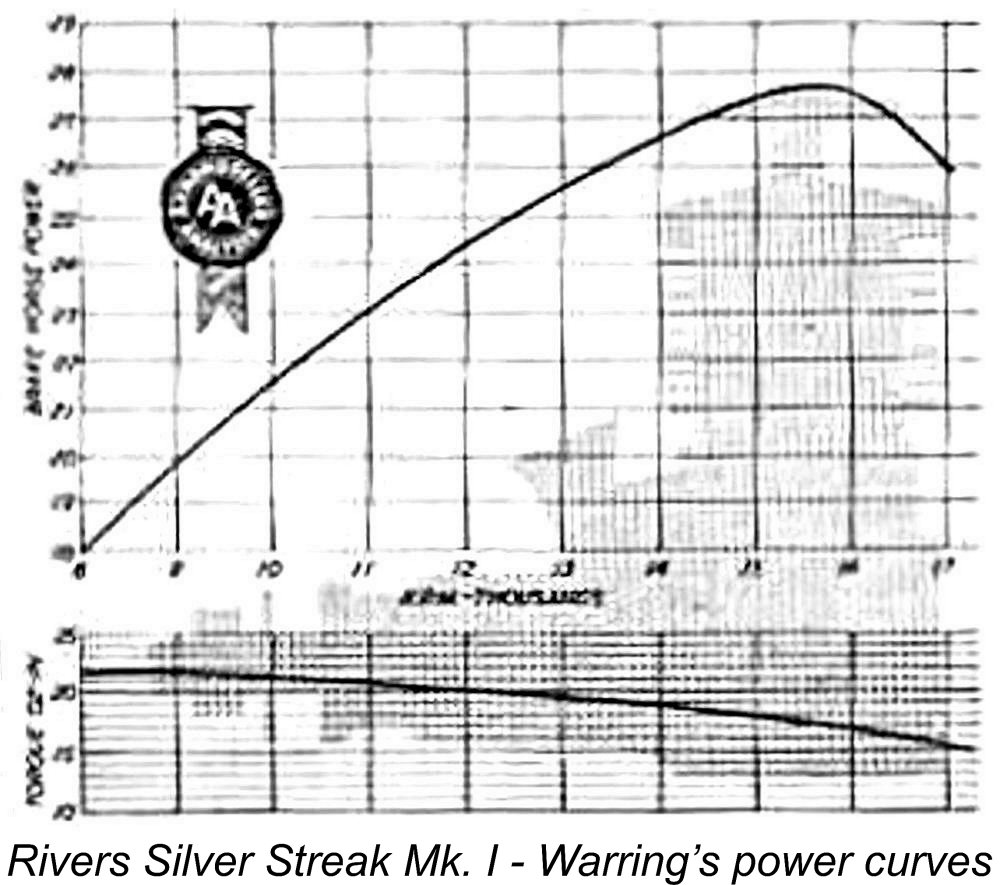

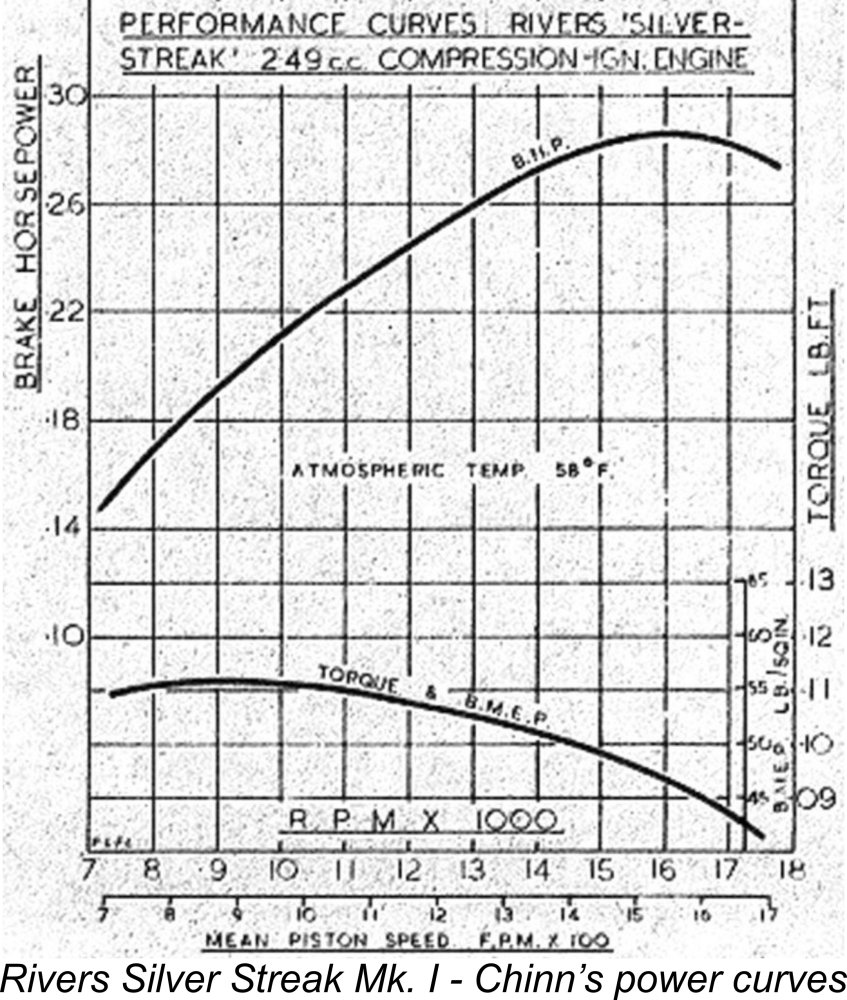

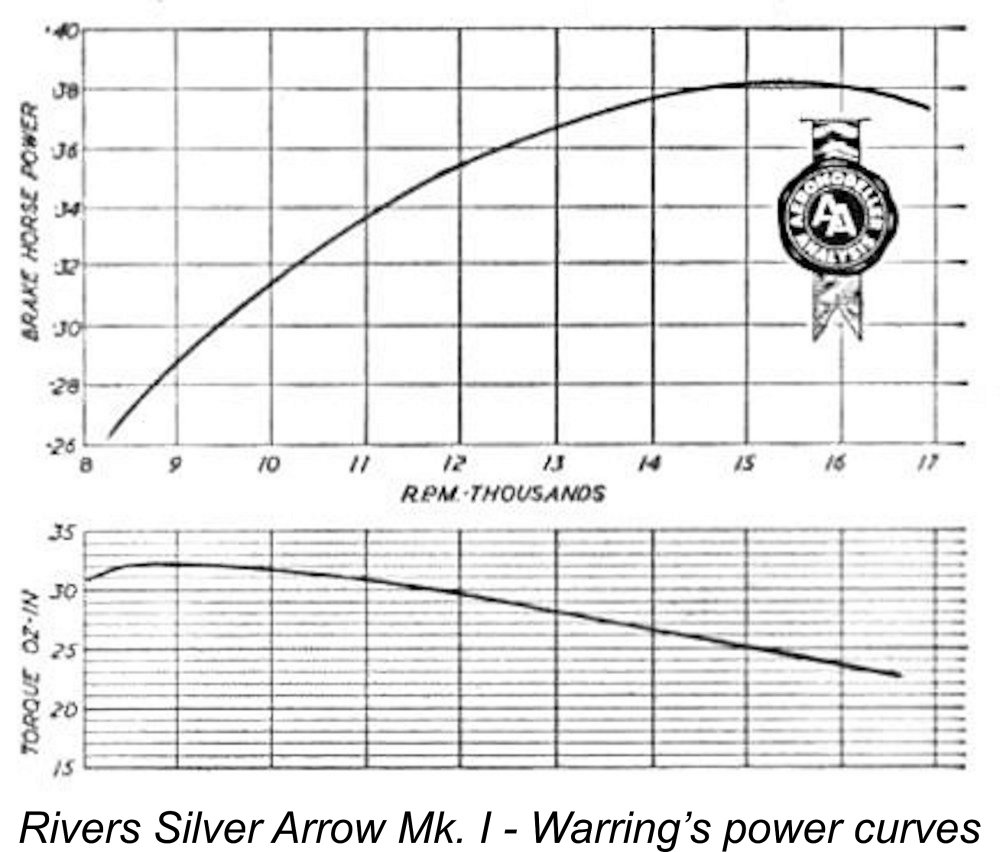

Warring extracted a peak power output of 0.277 BHP @ 15,800 rpm. This was the first indication of a potentially problematic future for the engine - a number of competing 2.5 cc diesels from Britain and elsewhere had previously been tested and found to equal or exceed this level of performance, some by a significant margin. Although Warring did not say so, it appeared on the basis of this test that all of the meticulous work involved in designing and constructing this engine to such high standards had not translated into anything special in the way of performance apart from the unusually high peaking speed for a diesel. For an engine with such a high selling price even in standard form, this was not a positive finding. Warring summarized his report by once more praising the standard of workmanship embodied in the Silver Streak. He justified the engine's higher-than-average selling price on the basis of workmanship rather than performance, although he did note that there was undoubtedly sufficient performance in the design to make the engine a potential contest winner. Finally, he noted that a 3.5 cc version of the engine (soon to appear as the Silver Arrow, of which more below) was even then under development.

Chinn began by reminding his readers of his earlier discussion regarding the growing issue of crankshaft weakness with high-performance 2.5 cc FRV diesels, going on to detail the manner in which this issue was addressed in the Rivers needle roller bearing design. Like Warring before him, he praised both the quality of the engine's construction and its handling attributes, characterizing the latter as being "of a very high order". He found starting extremely easy following a few choked turns and praised the non-critical nature of the controls. He described running qualities as "excellent in all respects".

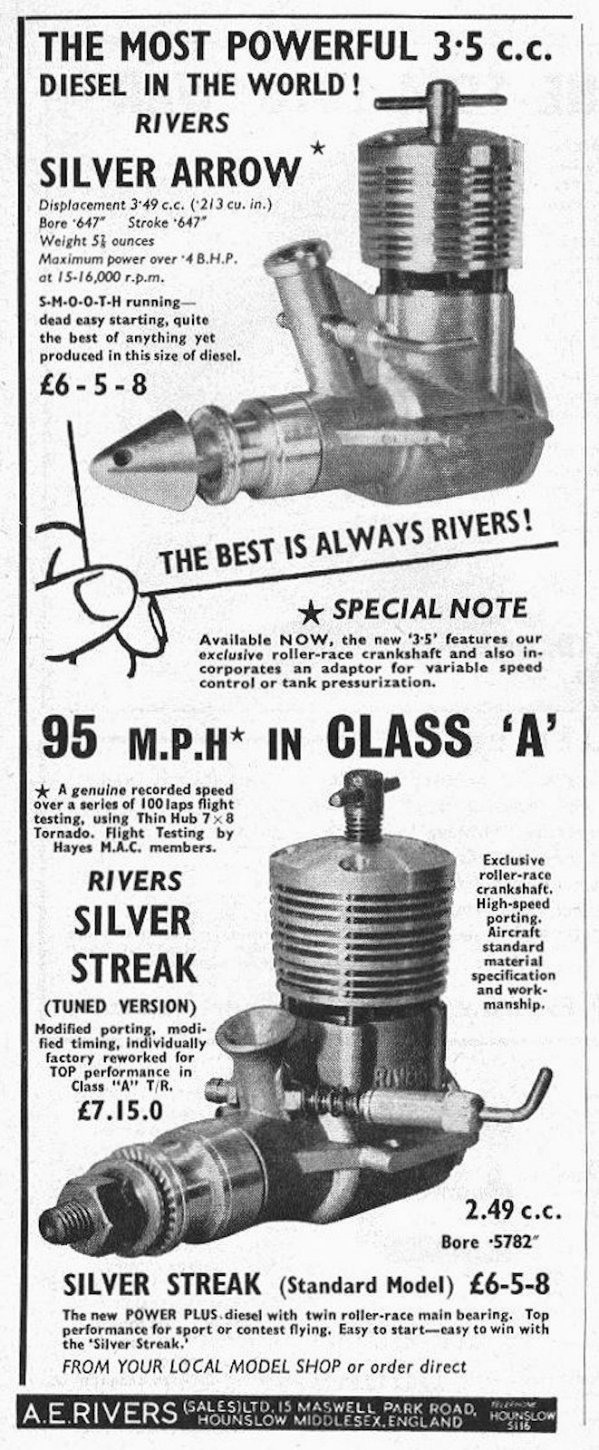

The results of the above two tests were remarkably consistent. They both made it clear that the Silver Streak was very much a high-speed engine which should be propped for around 15,000 - 16,000 rpm in the air to get the best out of it. However, they also revealed the underlying weakness of the Silver Streak's position in the model engine market as it then existed - in standard form, it was undeniably down on power compared to other competing models despite its higher-than-average price. The tuned engine would doubtless do better, but the even greater cost of that model was a significant deterrent. Perhaps even more problematically, the very high operating speed had negative implications for fuel consumption - a major factor in team racing. Early Competition Success Based upon the contemporary contest reports, it would appear that more or less the entire membership of Graham Rivers' Hayes cub rushed to equip themselves with Silver Streak motors! At this time, the Hayes club numbered some of Britain's most accomplished control line competitors among its members, and these individuals were keen to support the local product by demonstrating the potential of the new engine. In effect, the members of the Hayes club became the Rivers "works team"! Ian Russell was among the members of this elite group, which also included team-race expert Dave Balch and combat ace Robin Greenaway. By August of 1959 members of the Hayes club had posted a highly respectable 95 mph average speed in testing for a Class A team race event. Hayes club member Dave Balch was prominent in leading this effort, acting as pit man for models powered by his own tuned engines supplied by the factory. Tuned examples of the engine managed to reach both semi-finals in Class A team racing at the 1959 Godalming rally. In a team racing context, the engine was showing early promise, although it had yet to win a major event.

However, the Silver Streak continued for the most part to fall slightly short of matching the performance of the Oliver Tiger, which remained the standard against which all others were measured. It was clear that further work would be required in order to place the Silver Streak in a truly competitive position in the British marketplace. Having established his goal of beating the Olivers at their own game, Bert Rivers wasn't about to give up now!

Ian Russell recalled that these engines were very good performers indeed. They were apparently made primarily to give the combat crowd an edge while the 3.5 cc Silver Arrow was still in its development stage. Four examples of the 3 cc model were given to Hayes club members, of whom Ian was fortunate enough to be one. Ian believed that more than four of these units were made, but had no knowledge of where the others went. He ended up using his example of the 3 cc model to power his first-ever Gold Trophy control-line stunt entry at the 1959 British Nationals, in which he finished a very creditable 7th. He still had the engine in 2012. Interestingly enough, it bore no serial number.

There were also four sand-cast prototypes of a 3.5 cc diesel which used the same crankshaft as the Silver Streak, albeit with a greater throw. The manufacturers began mentioning the forthcoming appearance of their 3.5 cc model in their advertisements beginning in July 1959, as seen at the right. Peter Chinn conducted private tests on one of these 3.5 cc prototype units for the manufacturers, being quite impressed according to his report in the "Latest Engine News" feature of the October 1959 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Preliminary tests by “Aeromodeller” staff on another prototype reportedly yielded a peak output of 0.35 BHP @ 15,000 rpm, although the manufacturers evidently expected the production version to beat these figures. Another of these prototypes made it into the combat finals at the 1959 Ashford rally, as mentioned earlier. The "Motor Mart" feature in the November 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller” made reference to all of these experiments, noting that the only one which was set to appear in commercial form was the 3.5 cc diesel model, to be called the Silver Arrow. It's now time to take a closer look at that engine. The Mk. I Rivers Silver Arrow

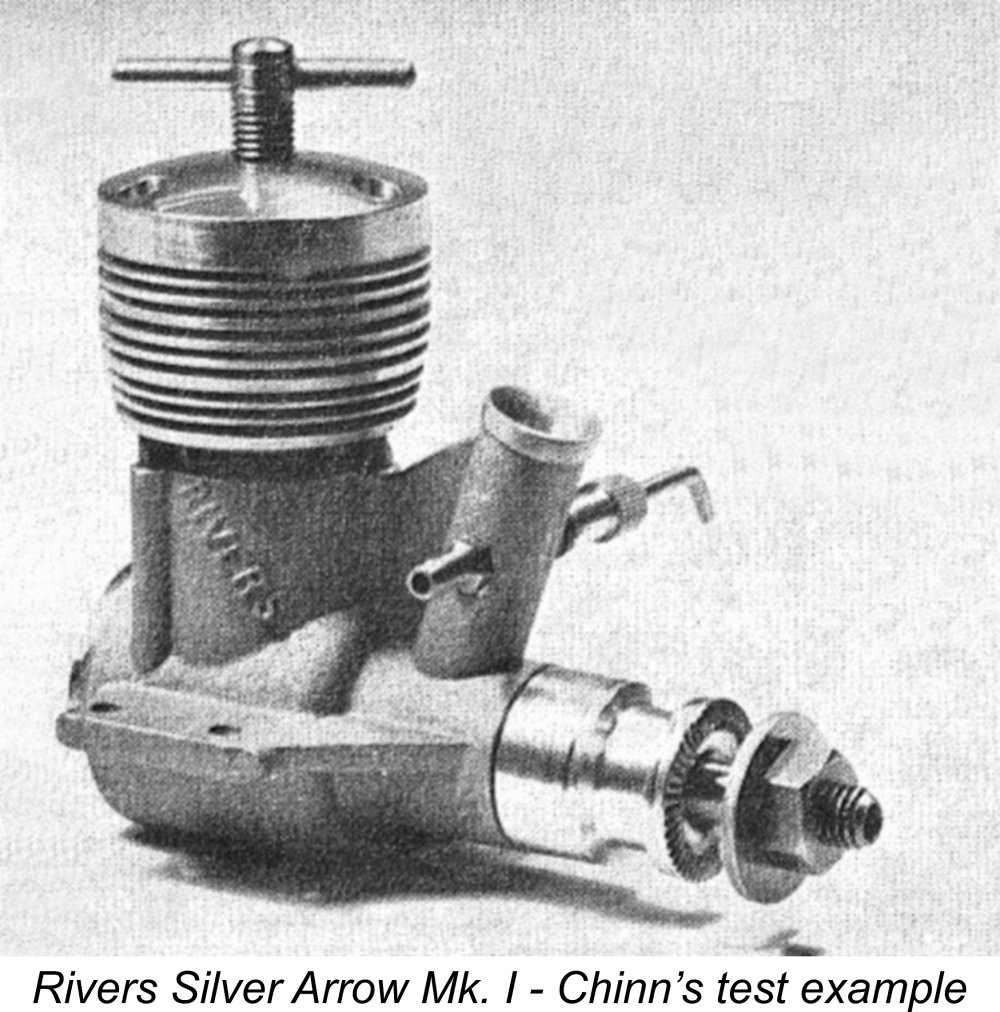

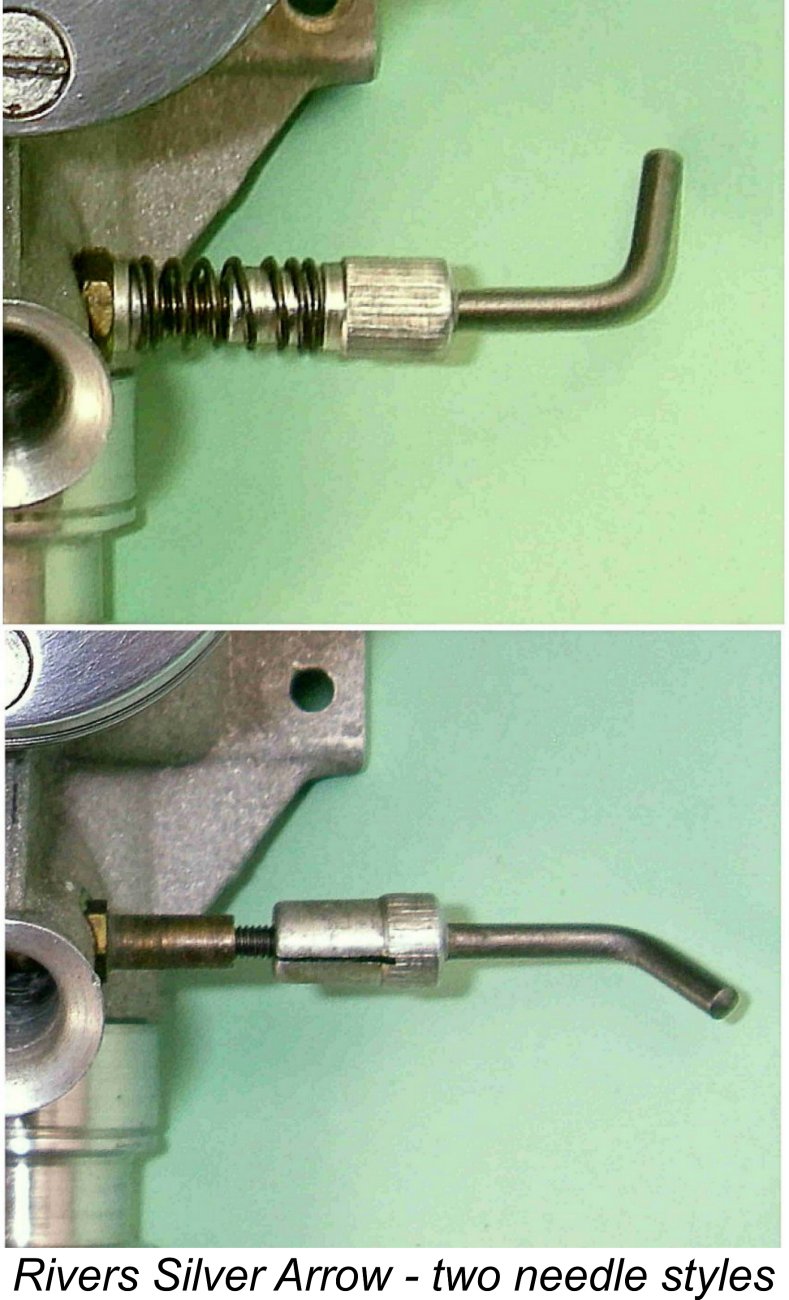

The Mk. I version of the 3.5 cc Rivers Silver Arrow finally made its appearance as a companion to the Silver Streak in the company's September 1959 advertising. Interestingly enough, the engine was introduced initially as the "Rivers 3.5 cc diesel" - no mention of the Silver Arrow name. The engine was first promoted under that name in the company's November 1959 advertising as seen at the left. The advertised selling price was £6 5s 8d (£6.28), slightly less than the introductory price of the Silver Streak. The price of the latter model was concurrently reduced to £6 5s 8d to match. The tuned version of the Silver Streak continued to be offered at a reduced price of £7 15s 0d (£7.75). Despite the engine's appearance in the advertisements, it seems that the production models did not actually begin to reach the marketplace until late November 1959. Peter Chinn noted this fact in his December 1959 "Latest Engine News" column in “Model Aircraft” (clearly written in late October to meet editorial deadlines), citing production problems with the gravity die-cast Silver Arrow crankcases as the reason for the delay.

The most significant departure from the design of the Silver Streak was the Silver Arrow's use of only three exhaust ports instead of the four used in the smaller model. These were accompanied by three upwardly-angled transfer ports between the exhaust openings. The transfer ports overlapped the exhaust to a greater degree than in the case of the Silver Streak, giving a relatively long transfer duration with a minimal blowdown period.

The induction period was actually increased over that used in the Silver Streak, the intake opening at 35° ABDC and closing at 45° ATDC for an unusually long induction period (for an FRV engine) of 190°. This was supplemented by a period of sub-piston induction. Exhaust timing was equally aggressive, with an opening period of 165°. This is the explanation of the very "powerful" sound of one of these engines in operation! I suspect that a reduction in the exhaust period could have resulted in improved mid-range torque.

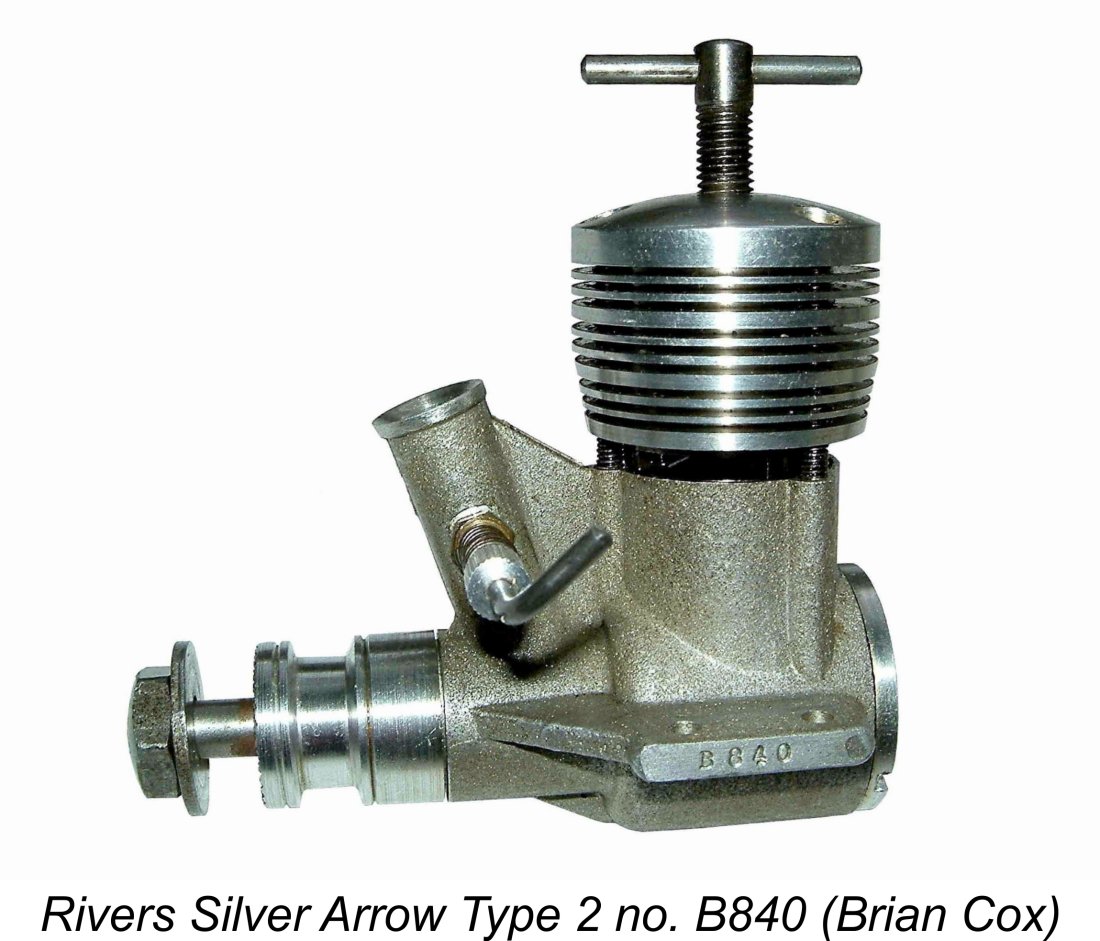

Like their Silver Streak siblings, the Silver Arrows were numbered sequentially on the left-hand mounting lug, starting at engine number 1. In this case, the letter prefix B was used to indicate that this was a 3.5 cc model. I am aware of engine numbers B38, B101 and B120 as well as engine numbers B186, B205 and B274 which were reported respectively by Miles Patience, Brian Cox and Pat Hardy following the initial publication of this article. As before, tuned engines were available from the manufacturers, although in the case of the Silver Arrow the letter T usually appeared as a suffix to the main number rather than as a prefix. Engine number B2132T exemplifies this system. There have also been persistent reports of Silver Arrows which feature no serial number at all. I'll comment further on this latter point in a subsequent section of this article. The original version of the Silver Arrow just described is by far the rarest variant. Perhaps this reflects the sad fact that many of them are known to have broken their crankshafts. Peter Chinn made specific reference to this problem in his April 1960 "Latest Engine News" column, noting that a larger shaft of different design was then in the process of being introduced for both the Silver Arrow and Silver Streak. Although this can't be proved, it's likely that any engines returned with broken shafts under guarantee from March 1960 onwards were fitted with the larger shaft, necessitating a replacement case to accommodate the larger-diameter main bearing sleeve. Logical move - why fit a replacement for a busted shaft that you suspect may simply break again? This may well explain the reported existence of a number of Silver Arrows with no serial numbers - they may be upgraded early models. As a high-performance diesel of 3.5 cc displacement, the Silver Arrow's obvious application was in control line combat, since then-current S.M.A.E. rules allowed engines of up to 3.5 cc in that category. I’ve noted previously that even before its release to the public the Arrow had attracted some attention in that category in prototype form. This being the case, test reports on the performance of the production version were awaited with some interest. The Mk. I Silver Arrow On Test

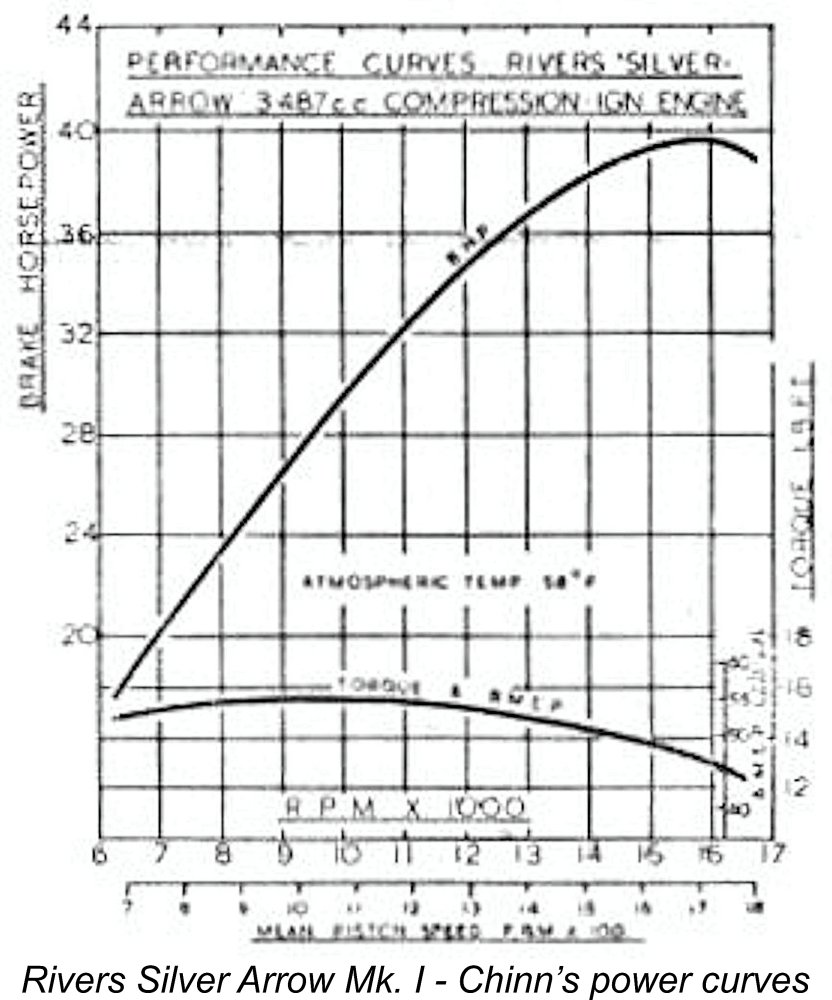

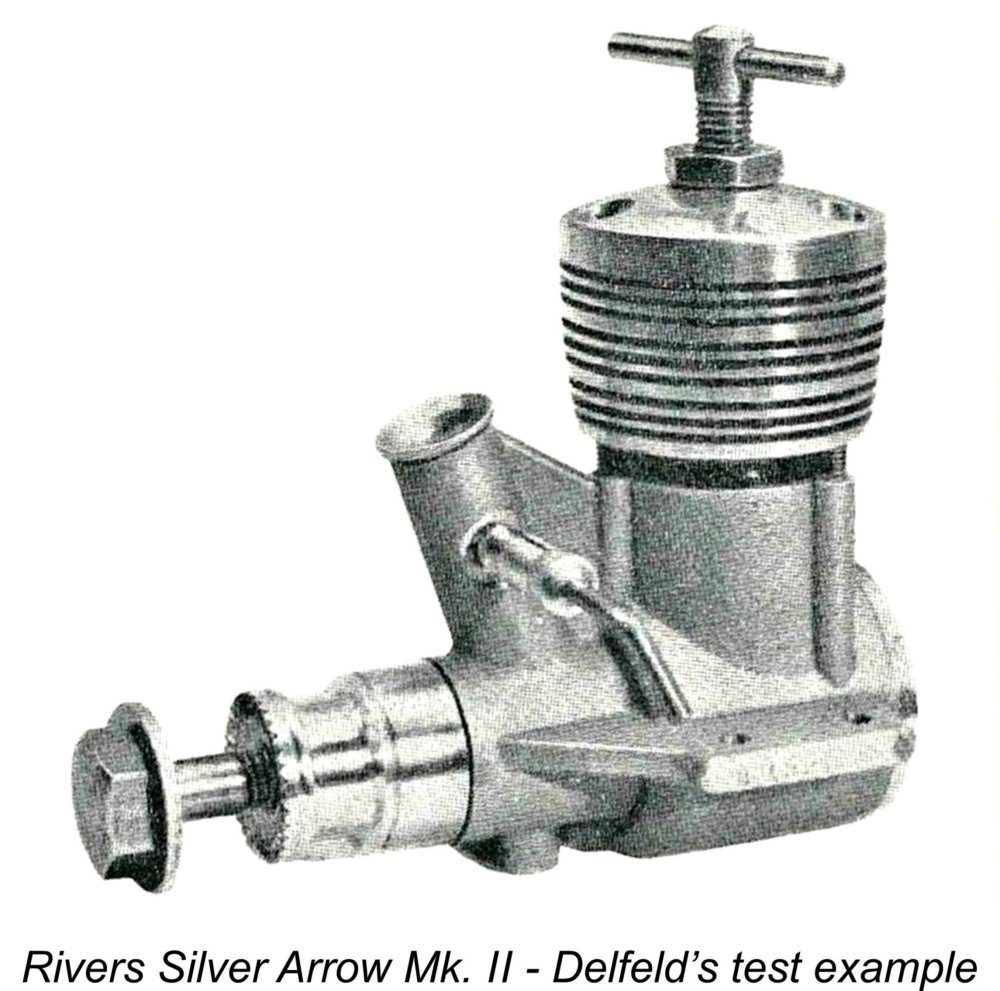

It is perhaps a measure of the extent to which Chinn was impressed by this engine that he began his report with what amounted to a defence of his findings in light of the known fact that different examples of the same engine can undeniably perform at different levels. He conceded the possibility that not all production examples might come up to the standard displayed by his test engine, but concluded that regardless of the answer, the Silver Arrow was "inherently, an exceptional engine, with handling and performance characteristics that lift it well above the general run of "large" diesels". Chinn stated without prevarication that his test engine's power output "far surpassed that of any other 3.5 cc diesel produced to date". He characterized the engine's handling qualities as "remarkable", stating that it was "quite the easiest starting 3.5 cc diesel we have encountered in recent years".

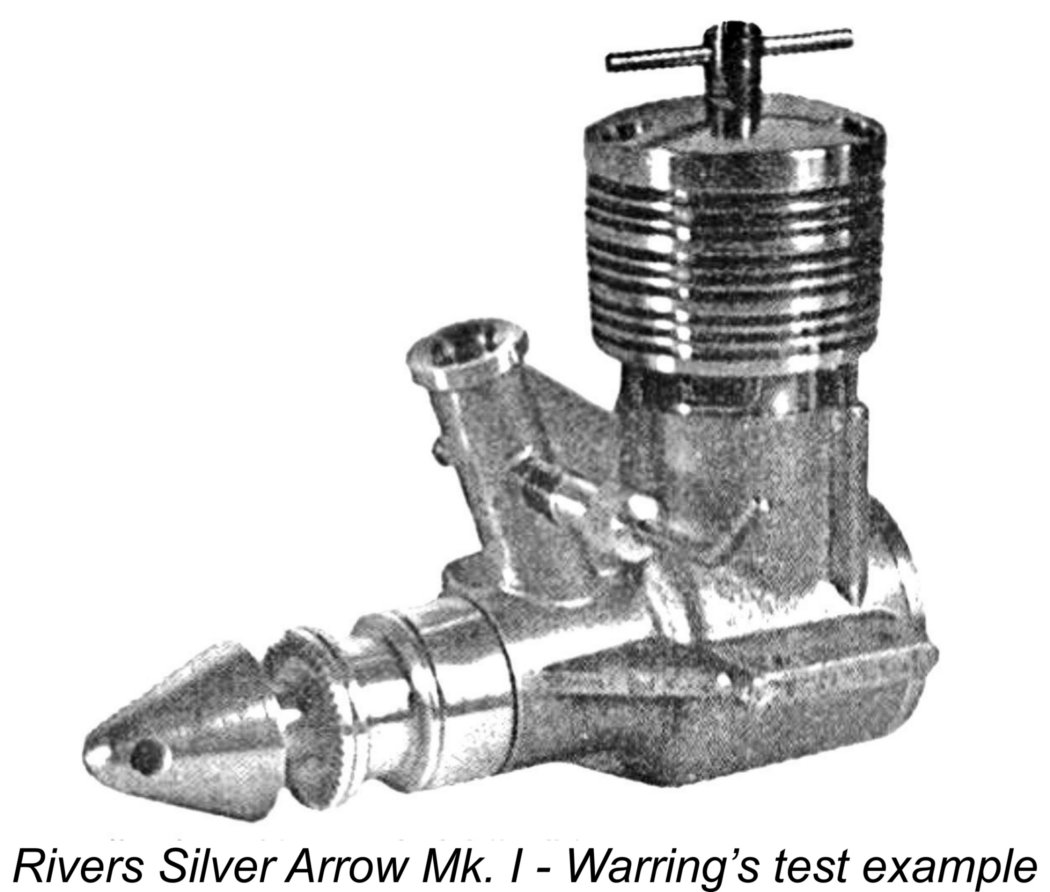

Chinn concluded his report by noting that while the Silver Arrow was relatively costly at £6 5s 8d, this could hardly be considered unreasonably expensive considering the engine's "all-round excellence". High praise indeed from Britain's most respected model engine expert! In the case of the Silver Arrow, Ron Warring of “Aeromodeller” magazine lagged as far behind as he had been ahead when testing the Silver Streak. His test report on the Silver Arrow didn’t appear until the July 1960 issue of the magazine. When it did so, it was every bit as complimentary as Chinn's had been. Warring confirmed that the engine was "remarkably easy to handle", praising its running characteristics in addition. He also commented on the outstanding quality of the engine's construction.

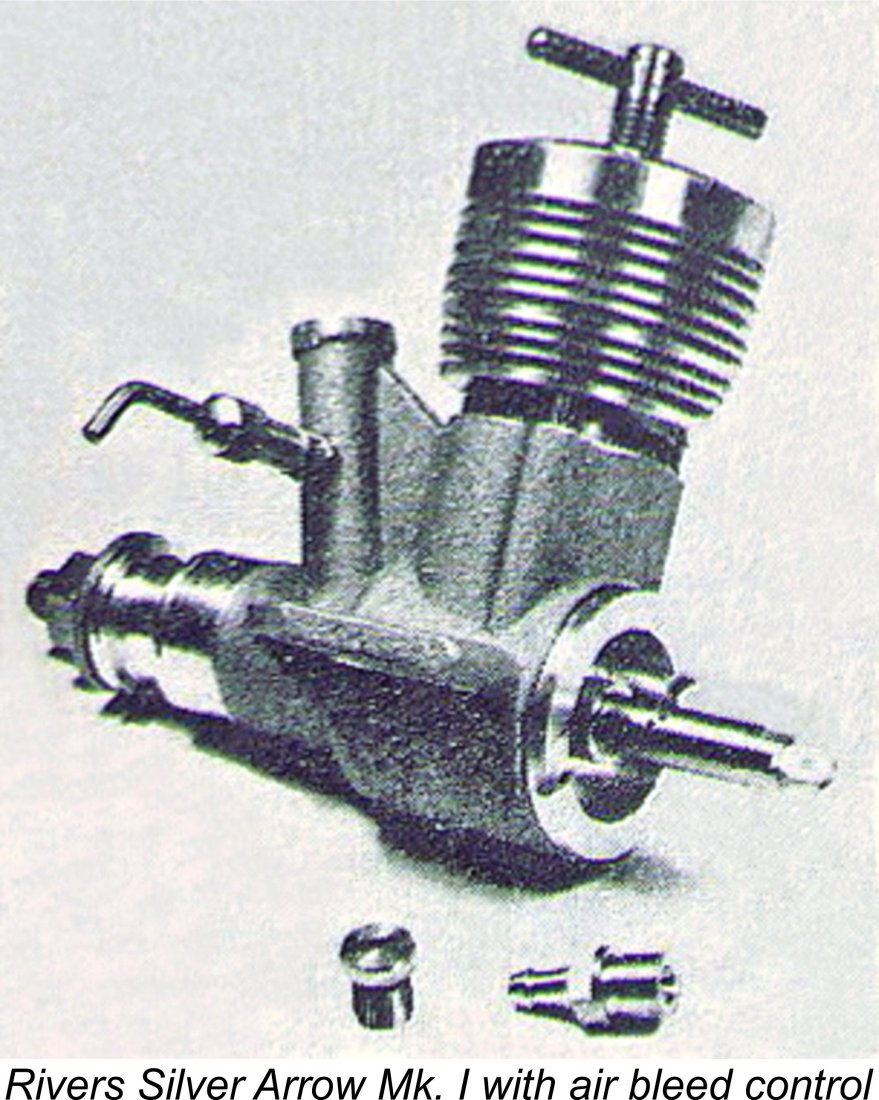

One accessory tested by Warring which had escaped Chinn's attention was the air-bleed throttle which could be installed in the central backplate spigot in place of the standard brass plug. Warring found that this gave quite reasonable throttle control, a speed reduction of around 50% being recorded with the air bleed fully open. Response to closing the air bleed was found to be immediate, the engine returning instantly to full speed.

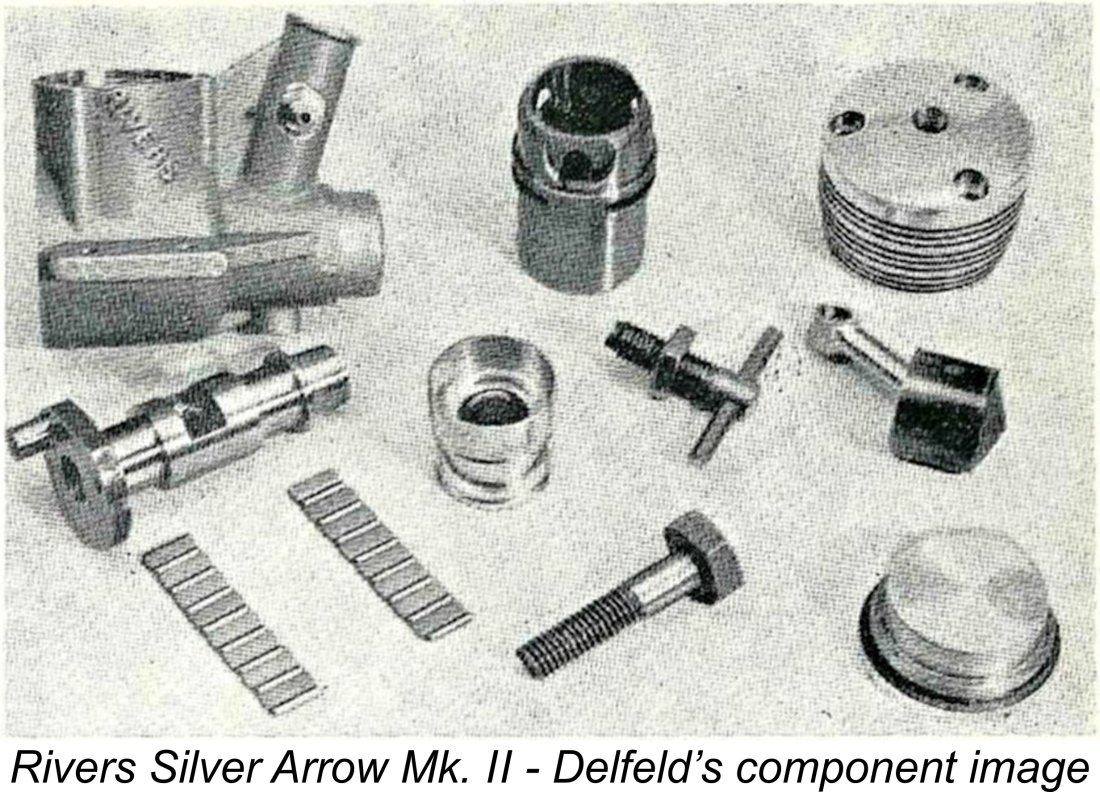

Warring noted the fact reported earlier by Chinn that problems had been experienced with some of the earlier engines with crankshaft breakages. Although according to the manufacturers this problem had been confined to a specific batch of crankshafts which had been made too hard, Warring confirmed that the company had elected to play safe by increasing the roller bearing journal diameter of the shaft in both the Silver Streak and Silver Arrow from 0.350 in. to 0.406 in. This necessitated an increase in the number of rollers used from seven to eight to maintain an appropriate spacing. The diameter of the central section of the shaft was of course increased to match, as was the bore of the steel bearing sleeve. The prop mounting system had also been changed from a threaded extension of the shaft to a threaded recess in the shaft interior at the front into which a steel 0 BA prop mounting bolt (or alloy spinner bolt) was screwed. A hard impact might be expected to bend or break the bolt rather than damage the shaft - a far less costly repair, especially given the complexity of the Rivers crankshaft assembly! This change actually appears to have preceded the increase in the diameter of the main journal, since although the example tested by Warring featured the newly-introduced internally-threaded shaft with prop bolt, it retained the earlier 7-roller bearings (clearly seen in the component images which accompanied the test report). In addition, it retained the air-bleed spigot in the backplate which was about to be dropped, also lacking the steel hex nut compression lock which was applied to the revised models. It was thus identical to the Mk. I example tested by Peter Chinn apart from the method of prop mounting. In commenting on the above changes in the shaft design, Warring was in fact speaking about the updated versions of the two models which were just being released at the time when his test report on the Mk. I version of the Silver Arrow was written. Let's have a look at those models. Upgraded Versions of the Silver Streak and Silver Arrow

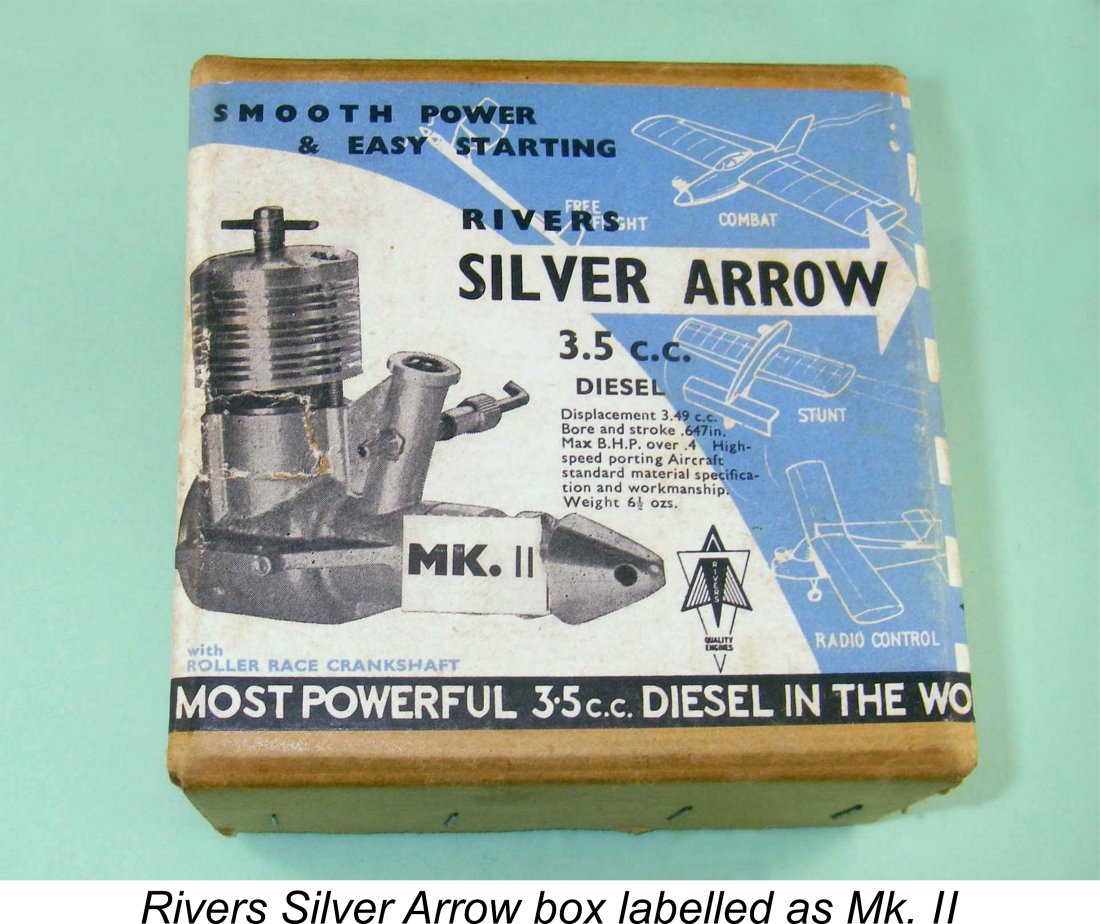

At this point, it's unfortunately necessary to interrupt our story to deal with a somewhat controversial matter - the question of model identification as applied to the Silver Arrow. This issue arises largely due to inconsistency on the part of the manufacturers, who identified the upgraded Silver Streak as a Mk. II from the outset (see left) but did not do so for the Silver Arrow even though the upgrades were exactly the same. In consequence, there are strongly-held divergent opinions regarding the identification of the Mk. I and Mk. II Silver Arrow models. There is general agreement that the revised shaft is the defining feature of what was called from the outset the Silver Streak Mk. II, being referred to as such by the manufacturers in their advertising. However, this matter is far less clear in the case of the Silver Arrow. The issue is further clouded by the fact that there are three variants of the Silver Arrow, not two! Let's review the issue in detail. It seems best to begin by recording the three distinct production variants of the Silver Arrow of which I’m presently aware: 1) Early model as tested by Chinn and Warring and referred to by Chinn in his April and July 1960 articles, with the smaller-size 7-roller shaft and externally-threaded extension for the prop nut or spinner nut. The serial number range clearly started at B1, but to date the only reported engine numbers for this type are B38, B101, B120, B205 and B274 - scarcely a statistically reliable sample! We therefore have no firm estimate for the upper limit of the range, except to say that by engine number B315 it had undoubtedly been supplanted by the next model in the series (see below). The implication is that no more than some 300 examples of this version of the Silver Arrow were manufactured. 2) Significantly revised model heralded in April 1960 and further detailed in July 1960 (by Peter Chinn in both cases) with larger 8-roller shaft and prop-bolt (or spinner-bolt) with internally threaded shaft, also missing the former spigot in the backplate for the air-bleed accessory (although a few examples continued to feature the air-bleed, perhaps as a customer option - engine no. B886 is an example). A steel hex nut was now included to serve as a compression lock. Presently-known serial number range - B315 to B1201. It’s noteworthy that there is a seemingly anomalous gap in the sequence between engine number B315 and the next highest reported number B635. I’ll have more to say about the implications of this gap as I proceed. 3) Further slightly revised model which was identical in all respects to the previously-described variant apart from the addition of a pressure tapping point cast onto the underside of the main bearing as in the Mk. II Silver Streak. Presently-known serial number range – B1224 to B3114. For the sake of clarity during the following discussion, I’ll refer to these variants as Type 1, Type 2, and Type 3. Readers should remain mindful of the fact that these are my own identifying terms which have nothing whatsoever to do with any official identification. They are applied here solely to ensure clarity regarding which variant I’m discussing in this article. Looking at each of these variants in turn, the example tested by Peter Chinn was unquestionably of Type 1 - the images which appeared with his test report prove as much beyond argument. It has been suggested that this variant should be viewed as a prototype, but this flies in the face of Chinn's earlier statement in his October 1959 "Latest Engine News" column in “Model Aircraft” that only four prototypes were produced and that these had apparently undergone extensive testing with no problems, both by Chinn and others. It is also inconsistent with the fact that as many as 300 examples of the Type 1 Arrow are known to have been produced. Nobody produces and sells that many prototypes! Furthermore, Ian Russell advised that he was privileged to field-test one of the original prototypes back in 1959. He recalled that they were quite distinct from the subsequent production versions, having very rough sand-cast crankcases as well as different timing. They apparently required excessive proportions of amyl nitrate in the fuel (as much as 5%), a characteristic which was found to be related to the cylinder port timing employed. In the production versions, this problem was partially relieved by the simple expedient of raising the cylinder somewhat to extend the exhaust and transfer periods, although later testing showed that the Rivers engines nonetheless retained a preference for well-nitrated fuel. Further evidence is to be found in Peter Chinn's previously-mentioned April 1960 "Latest Engine News" article in “Model Aircraft”, in which Chinn noted that "a few cases of shaft breakage have been reported from users". He made it specifically clear that he was speaking of the shafts used in "prototype and initial These statements together appear to me to confirm that the original production version of the Silver Arrow differed significantly from the prototypes and moreover unquestionably featured the externally threaded prop shaft as seen on Chinn's test example. I am aware of absolutely no evidence to the contrary. Whatever one's views regarding the following two variants, it seems indisputable to me that Type 1 in our list was the initial production version of the engine and can thus lay a persuasive claim to being viewed as the Mk. I version of the engine. We have to call it something - if not the Mk. I, then what?

It has been suggested that these stickers were placed in error by packing staff who were then quite legitimately placing "Mk. II" stickers on Silver Streak boxes and were simply doing the same (incorrectly) with the Silver Arrow. However, there is no evidence whatsoever to back up this assertion. Moreover, it's really hard to envision such an elementary error escaping the attention of company management for the entire production life of the Type 2 variant. That said, there has to be some explanation for the presence of those stickers! I'm personally a great believer in the validity of Occam's Razor, which says in effect that when multiple solutions to an issue present themselves, the simplest and most obvious is very likely to be the truth! in this case, the simplest and most obvious explanation is that the stickers meant exactly what they said and that the engines in the boxes were indeed viewed by the manufacturers as Mk. II models. If it was only as simple as that, we'd be done with this discussion!

The difference in these approaches is surprising given the fact that the major change to both models was the switch to a beefed-up crankshaft, the only real difference being that the Silver Streak also received a pressure tapping point under the main bearing, while the Silver Arrow did not (but see further discussion of this point below). Moreover, the Silver Streak's venturi intake was changed to match that on the Silver Arrow. So why the Mk. II was applied in the advertisements to one but not the other despite the identical box labelling remains unclear. For my part, I can think of at least one plausible explanation for this. The upgrade of the Silver Arrow was prompted not by any performance shortfall but by a design flaw in the original model. The company may have been reluctant to remind their customers of this somewhat embarrassing fact. Therefore, their advertising continued unchanged. However, they needed to have some way of confirming that engines going out to customers had the revised shaft, hence the Mk. II stickers on the boxes. This possibility is no more amenable to proof than the alternative explanation of a simple labeling error, but it seems to me to be far more likely.

For me, a change to a new Mk. number purely on the basis of the addition of a pressure tapping point appears highly uncharacteristic of normal model engine manufacturing practise. The record shows that changes in model identification were generally accompanied by far more substantial design changes than that. Moreover, changes in model designation were generally based upon performance-related improvements. Manufacturers routinely introduced minor changes such as a pressure tapping point, which didn't affect engine performance in any way, without altering their model identification. This is not to say that Rivers couldn't have made such a change in identification on that basis - merely that it would be highly unusual for them to do so in light of normal industry practise. To me, it seems far more likely that the change came about simply because they ran out of the original cases for the beefed-up Silver Arrow and had to order a new batch. When that requirement arose, they decided to add the pressure tapping point to bring the 2.5 cc and 3.5 cc designs into closer conformity. This may have been seen as an excuse to start openly referring to the engine as the Mk. II Silver Arrow in the ads, as it had been all along on the boxes, without harking back to the embarrassment of the crankshaft failures. By this stage, they may have felt that enough time had passed that the openly-applied Mk. II designation would be viewed as an indication of an upgrade rather than a response to a design shortcoming, even though in reality the engine was unchanged in functional terms. So what does all of this mean? Well, my preferred approach is always to deal with the evidence as I find it. We have ample evidence both from Chinn and from surviving examples that the original Silver Arrow used the externally-threaded small-diameter shaft, both in prototype and production form. So for me, that has to be the Mk. I version - what else can we call it? Following a series of failures, the shaft was re-designed, triggering a parallel re-design for the Silver Streak also. Both revised models were identified on the boxes as Mk. II's, although only the Silver Streak was so designated in the advertisements, at least initially. Nevertheless, those Mk. II box labels exist and cannot legitimately be ignored. Unless persuasive evidence appears to support an alternative explanation for the presence of those Mk. II labels on the boxes for Type 2 examples of the Silver Arrow, I personally believe that we must give the manufacturer credit for knowing what he was doing and that the Type 2 Silver Arrow should be viewed as a Mk. II model. After all, in functional terms it is a Mk. II model - the only difference between it and the Type 3 variant is the pressure point, which would constitute a highly uncharacteristic basis for a model identification change based on the usual approach taken by model engine manufacturers. This having been said, the argument seems to me to be essentially moot. Since the only difference between Type 2 and Type 3 is the pressure point, in practical terms they're one and the same engine. To call one a Mk. I and the other a Mk. II makes little sense to me personally, but it really doesn't matter regardless - they're effectively the same engine whatever you choose to call them! Readers are free to form their own opinions on this issue ................ Perhaps the fairest way to leave this issue is to state that for the purposes of the balance of this article I will refer to Type 1 from my list above as the Silver Arrow Mk. I, Type 2 as the Silver Arrow Mk. IIa and Type 3 as the Silver Arrow Mk. IIb. I fully realize that not everyone will agree with me, but we have to move this lengthy discussion along.................. The Mk. II Versions of the Rivers Engines

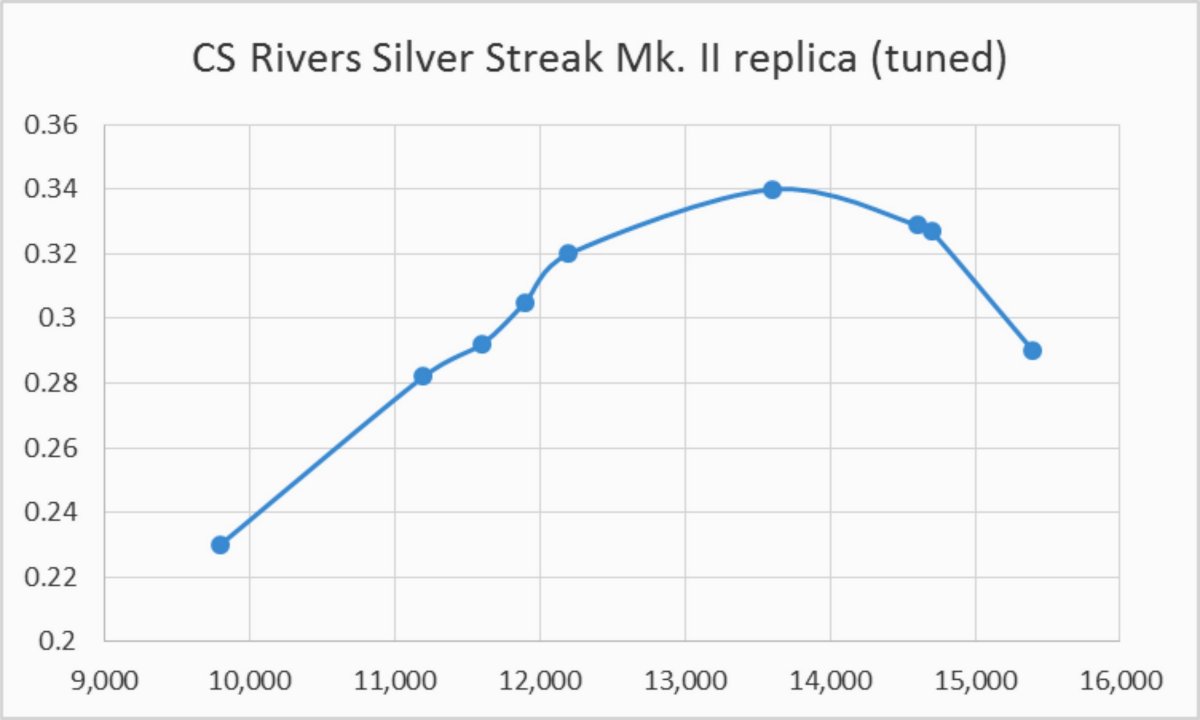

The diameter of the central plain bearing section which incorporated the induction port was also increased from its former 0.4682 in. to a truly whopping 0.524 in. (13.31 mm). Along with this went some minor changes to the induction timing to match the engine's theoretically improved breathing capacity. The prop mounting system was changed from the original prop nut design to the prop bolt arrangement mentioned by Warring. The crankcase was also modified, featuring an increased diameter with a consequent increase in crankcase volume. This measure appears to have been aimed at improving the engine's fuel consumption for team racing. The crankcase sported a revised intake along the lines of the unit featured on the companion Silver Arrow, being far taller than that used on the original Silver Streak and lacking the former bell-mouth. As on the Arrow, the spraybar was now aligned at right angles to the engine's axis so that the needle could be oriented either to left or right of the engine. The final change to the crankcase was the inclusion of an integrally-cast blind spigot beneath the main bearing at the intake location. This could be drilled and tapped to allow for the fitting of a nipple to direct timed crankcase pressure to a pressure feed fuel system. Bore and stroke remained unchanged, but a slightly longer piston skirt was used together with a longer con-rod. Cylinder port timing was slightly altered as well to harmonize with these new dimensions. In all The engines were packaged in sturdy cardboard boxes with a label having a red-and-white background. The boxes appear to be the same ones used for the Mk. I engines, since the unit illustrated on the label continued to be a Mk. I model. A Mk. II sticker was added to identify the contents. This was strategically located to obscure the fact that the illustrated engine was a Mk. I model with a conventional prop nut and washer. The boxes also bore a second sticker which covered the former Hounslow address, giving instead the company's new trading location on Faggs Road in Feltham. A works tuned version of the Silver Streak Mk. II continued to be offered, featuring a further enlargement of the internal gas passage in the crankshaft from 0.256 in. to 0.280 in. at the cost of a decrease in wall thickness at the journal to only 0.063 in. This however was still greater than the 0.055 in. wall thickness featured in the tuned version of the Mk. I Silver Streak with its 0.240 in. dia. central gas passage. Moreover, the slightly increased wall thickness extended around a greater circumferential arc length of shaft, providing substantially more metal to resist operational stresses. Along with this went a considerable amount of individual reworking, much of it carried out by hand. The cost of this tuning work was an additional £2 10s 0d (£2.50) over the price of a standard example.

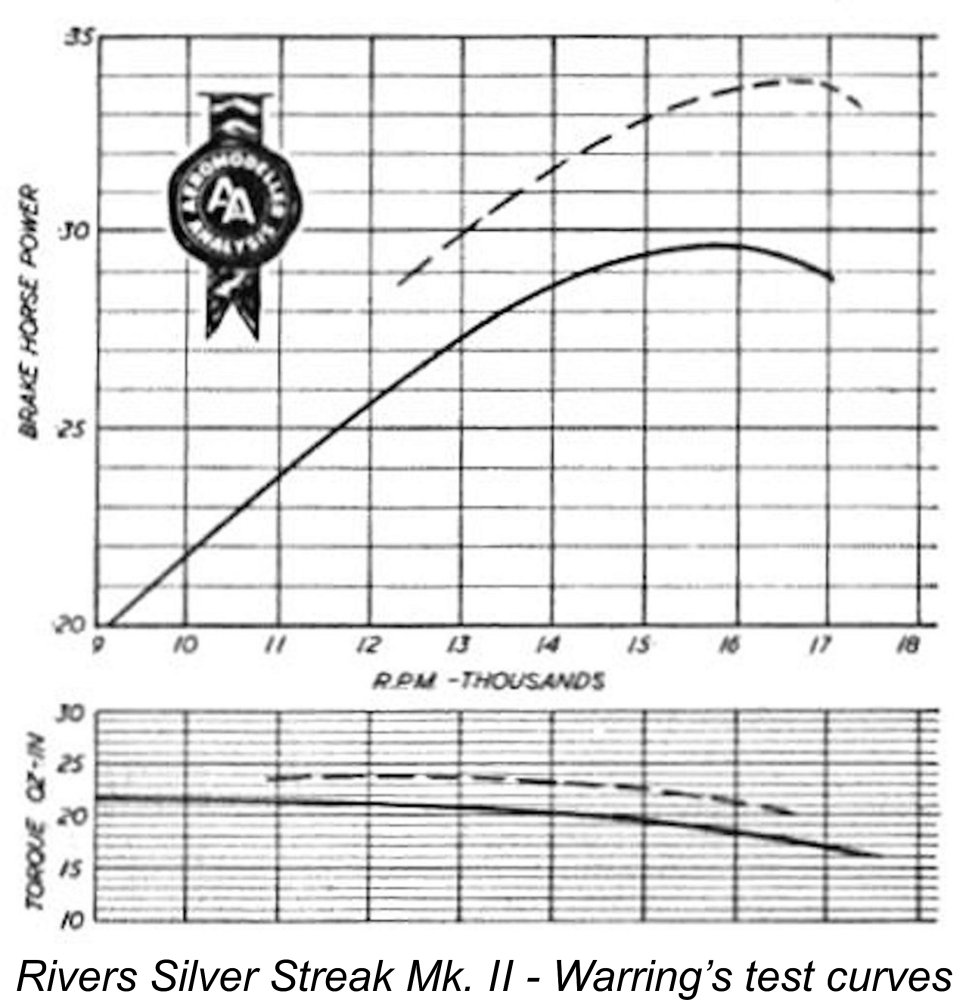

Warring's published test figures bore out this assessment. The standard version of the Mk. II Silver Streak was found to deliver 0.296 BHP @ 16,000 rpm, an increase of some 7½% over Warring's figure for the previous model. Spot testing of the tuned model revealed an even more impressive improvement - indications were that this version produced some 0.34 BHP @ 16,500 rpm, an increase of over 20% on the original model and over 13% compared with the standard Mk. II model.

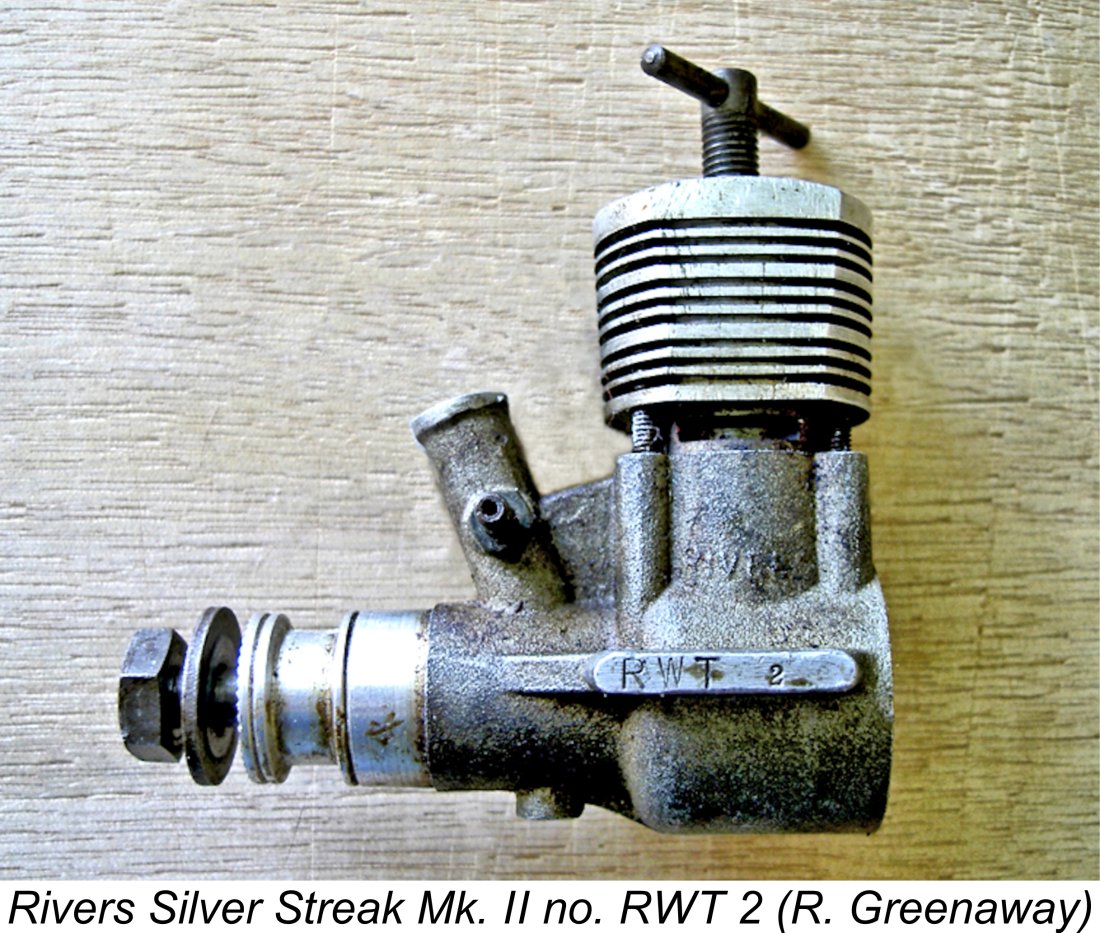

All of these competing models outperformed the standard Rivers Silver Streak Mk. II, and did so at a significantly lower cost. The tuned Silver Streak Mk. II was a match for any of them, but its overall cost of £8 15s 8d (£8.78) was well above that of any of its competitors. This did not bode well for the long-term future of the Rivers range. It's perhaps significant to note that Peter Chinn never published a test of the Mk. II Silver Streak. Chinn was clearly very well-informed regarding the design details of the new variant given his coverage in his previously-mentioned articles of April and June 1960. This being the case, it's inconceivable that he would not have undertaken a direct evaluation of the new model. Chinn was well known for his reluctance to As of 2012, former Hayes combat ace Robin Greenaway still had his tuned example of the Mk. II Silver Streak. Like most of the Rivers engines used by the Hayes club, this unit was supplied to Robin direct from the factory. It is numbered RWT 2, which conforms to no established Rivers serial number sequence. The best guess that the Hayes boys could come up with is that RWT stands either for "Rivers Works Tuned" or "Rivers Works Team", the latter possibility being due to the fact that the Hayes club members were the de facto Rivers works team at the time, hence their direct access to hand-picked works-tuned engines.

The resulting model was externally little changed from its predecessor apart from the use of a prop bolt or spinner bolt in place of the former threaded extension and nut system. However, the engine was significantly altered internally, now featuring the beefed-up 8-roller shaft described earlier. The same crankcase casting was used, merely being bored out some 60 thou oversize to accommodate the slightly larger main bearing sleeve. There was plenty of metal to accommodate this change. Apart from the revised shaft, a few detail differences were also apparent. The engines were now supplied with a steel hexagonal nut for the purpose of locking the compression setting. While this was very effective, it had the disadvantage of requiring the use of a spanner for tightening. A locking lever would have been more practical. Another minor change was the omission of the tapped spigot in the backplate - presumably the accessory air-bleed throttle had not proved to be a great success.

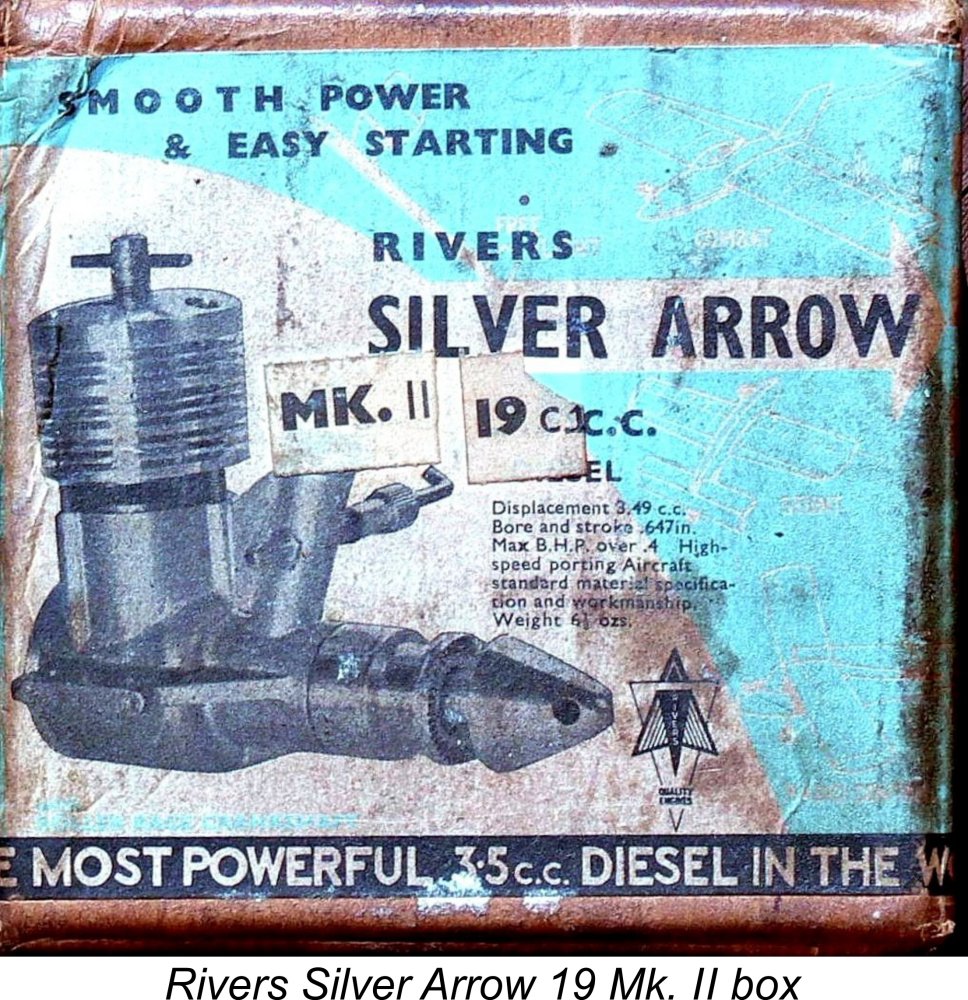

The increased mass of the beefed-up shaft naturally had an effect on the engine's weight. The revised model weighed in at an extremely hefty 7.45 ounces (211 gm), some 9 gm more than the already-heavy Mk. I version. At this time, competitors were just beginning to appreciate the critical importance of low wing loadings in the aerobatic performance of the control-line combat models for which the Silver Arrow was primarily intended, so this was not a positive attribute of the engine. Even if the soon-to-be-enacted S.M.A.E. rule change banning 3.5 cc motors had not come into effect, it's likely that the weight factor alone would soon have caused modellers to look elsewhere for their combat powerplants. Like the Silver Streaks, the Silver Arrows were packaged in sturdy cardboard boxes, albeit with a label having a blue-and-white background to allow easy identification of the model. Again, the boxes appear to be the same ones used for the Mk. I engines, since the image on the label was unquestionably a Mk. I model as tested by Peter Chinn. As with the upgraded Silver Streak, the boxes bore a strategically located Mk. II sticker to identify the contents as well as featuring a second sticker which A further change which appeared between engine numbers B1201 and B1224 was the addition of an un-drilled pressure tapping point underneath the main bearing, exactly as used on the Silver Streak Mk. II. This resulted in the third previously-discussed variant, the Type 3 Silver Arrow which I have chosen to refer to as the Mk. IIb. As previously noted, I am well aware that some Rivers enthusiasts consider this to be the only true Silver Arrow Mk. II despite the box labels and the fact that the Mk. IIa and Mk. IIb variants were exactly the same engine apart from the pressure tapping point. I leave it to readers to make up their own minds on this matter - we all have a right to our own opinions, and life's too short to waste time arguing!

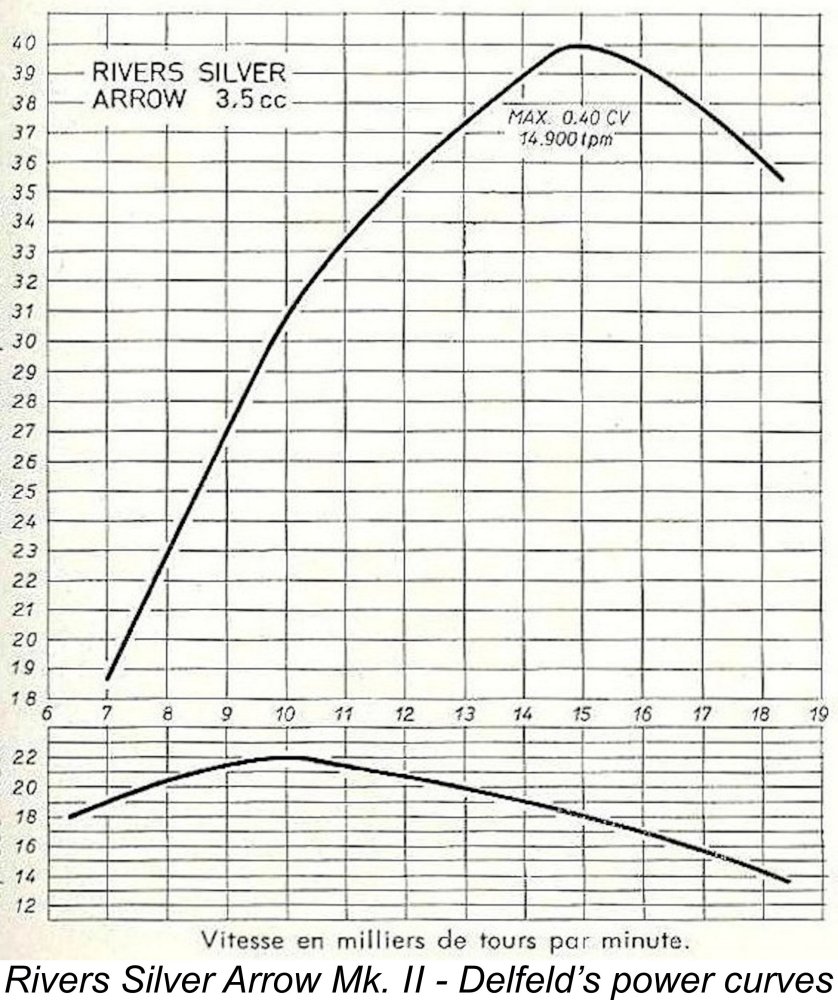

However, the Mk. IIb Silver Arrow was tested! Brian Cox was able to confirm that engine number B1224 was sent by the manufacturers to "Model Avia" magazine in Brussels, Belgium, to be tested by the late Pierre Delfeld. Thanks to Brian for pointing out this connection. Thanks also to the kindness of reader George Blair, who provided me with a scan of Pierre's French-language report dated August 1961, of which I did a rough translation. Pierre was very taken with the engine, praising both its design and quality of manufacture. He found starting and running qualities to be as outstanding as his English colleagues had done previously. Overall, he described the engine as being "....a motor of the very highest class...".

That said, the figure obtained by Delfeld was near enough to 0.40 BHP at pretty close to 15,000 rpm. Moreover, the makers claimed that output had been This impression was later underscored by the publication of Ron Warring's test of the 3.5 cc Oliver Tiger Major in the April 1964 issue of “Aeromodeller”. The Ollie was found to produce 0.386 BHP @ 13,200 rpm. Clearly the Oliver produced quite a bit more torque but couldn't match the then four-year old Rivers design at the top end. Actual user impressions bore this out. Many enthusiasts who experienced both models (myself among them) considered the Silver Arrow to be superior to the Oliver Tiger Major in performance terms. Sadly, by the time the Tiger Major appeared, the Rivers range was history. Overall, the Silver Arrow Mk. II was a remarkable product and a great credit to its designers and manufacturers. It was undoubtedly the crowning achievement of the Rivers model engine manufacturing venture. A Rare Variant - The Rivers Silver Arrow 19

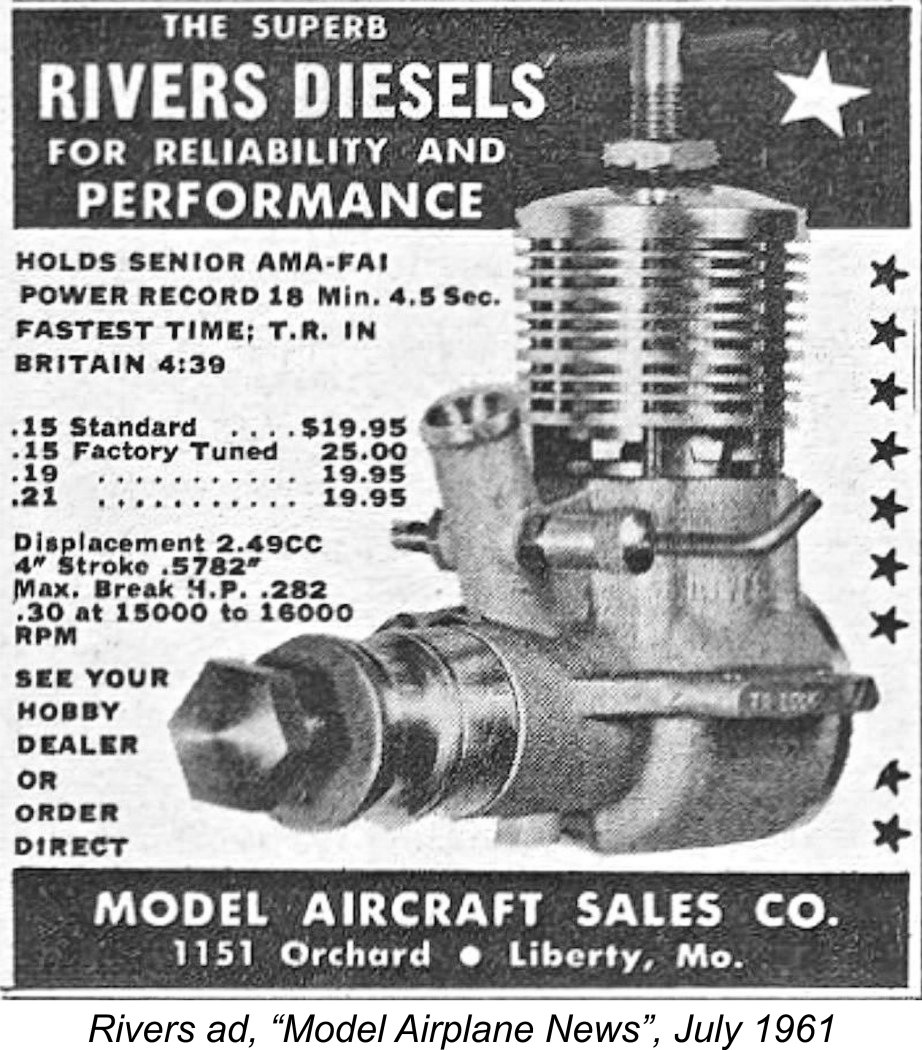

These engines were designated as the Rivers Silver Arrow 19. It's unclear just how many of these units were made, but the seeming rarity of surviving examples implies that the number cannot have been large. Somewhat strangely, I have yet to find an advertisement in a British publication which promoted this model, so perhaps it was only advertised in America. The earliest US advertisement which I’ve so far been able to find for this engine appeared in the July 1961 issue of “Model Airplane News” (MAN), where the 19 was promoted alongside its 2.5 cc and 3.5 cc relatives. At this time, the US distributor was the Model Aircraft Sales Co. of Liberty, Missouri. The same company also promoted a mix called Rivers Diesel Fuel, a commodity which as far as I know was never offered in Britain. Presumably it was mixed in the USA to Rivers' specification to alleviate the difficulty that many US modellers experienced at the time in obtaining diesel fuel.

The Silver Arrow 19 was externally identical to the Mk. IIa model described earlier in that it was missing the pressure point beneath the main bearing. It featured both the prop bolt airscrew mounting and the steel hex nut compression lock. Weight was essentially the same as that of the Mk. IIa 3.5 cc Silver Arrow at a measured 7.48 ounces (212 gm). The only confirmed serial numbers that I have for the 19 are C452 (which I own), C453 and C462. The fact that these closely-spaced numbers lie within the known serial number range for the Mk. IIa Silver Arrow may indicate that these engines were manufactured in a small batch and were numbered within the main sequence starting at around 400 using the replacement of the B prefix with the C prefix to distinguish them from the 3.5 cc models. They may even have been converted 3.5 cc models as opposed to scratch-built 19's. The Rivers That Never Was - the Silver Bullet

In Britain at the time, the ½A class differed from its American counterpart in that engines of up to 1.5 cc (0.0915 cuin.) were permitted. In the control-line field, both ½A team race and combat were popular events, resulting in a steady demand for high-performance diesel engines of 1.5 cc displacement. The Oliver Tiger Cub was the most successful engine for ½A team racing, while the ½A combat field was in the process of becoming dominated by the light, powerful and durable P.A.W. 149 which had been introduced in May 1959. The Cub had been introduced in its improved Mk. II form in late 1960. Clearly, Rivers felt that they had a good chance of competing successfully against these established models. Whatever the motivation, there's no doubt whatever that in early 1961 they commenced the development of a 1.5 cc version of their basic design. In keeping with their established nomenclature, this was to be known as the Silver Bullet. As usual, Peter Chinn became aware of the Silver Bullet project during its developmental stages. In his "Foreign Notes" article in the August 1961 issue of MAN, Chinn made reference to the engine, stating that it was expected to appear "shortly". However, I have so far been unable to find another reference to the engine in any British modelling publication. Chinn also referred to the previously-described Silver Arrow .19 model in the same article. And that's where the story ends! The Silver Bullet never appeared in public, even in prototype form. However, there's no doubt whatsoever that at least one prototype was completed. In a post on one of the modelling forums, former ½A team race exponent Alan Dell recalled a 1961 invitation to go over to the Rivers plant at the North Feltham Trading Estate to assist in the evaluation of this prototype. He was asked to bring his best Oliver Tiger Cub along so that a direct comparison could be undertaken. Using the selected test prop, the 1.5 cc Silver Bullet ran well enough, allowing a fully representative prop speed to be sustained and measured. Alan then ran up his tuned Cub on the same stand, prop and fuel. Although he did not record the exact figures obtained, Alan recalled that his tuned Cub was between 1000 and 2000 rpm faster than the Rivers. In fact, according to Alan the performance differential was so great that it was this comparative test that prompted Bert Rivers’ decision not to proceed further with the development of the 1.5 cc engine.

To Ian, it seemed more likely that the test revealed not that the engine lacked potential but rather that the development of the engine to a suitable level of performance would require more time than Bert wished to devote to it. A further factor may well have been the realization that it would not be possible to manufacture the engine in quantity at a competitive price. It's clear that this was not an anticipated outcome, since the company did undoubtedly prepare a spare parts schedule, going so far as to include it in the instruction manual which accompanied their Mk. II 2.5 cc and 3.5 cc models. A scan of this document is attached for reference at the right. The Silver Bullet evidently used the same roller bearing crankshaft design as that employed on the larger engines. It also used the same four-port cylinder design as that of the Silver Streak. Overall, it appears that it was planned as more or less a scaled-down Silver Streak. The text of the manual included some additional comments specifically aimed at the Silver Bullet. A 9x4 airscrew was recommended for running-in. Oddly, the manual specifically stated that there would not be a tuning option available for the Silver Bullet. It also failed to include a specific performance claim for the engine, presumably indicating that sufficiently encouraging test figures were not available when the manual was printed. The cancellation of the Silver Bullet program is entirely understandable given that the tests on the prototype showed that the engine would require considerable further development to become competitive in performance terms against the best of the opposition. On top of this, the continued use of the Rivers needle roller bearing assembly in the Silver Bullet would have dictated a relatively high price for the engine, making it uncompetitive from a marketing standpoint as well. A further contributing factor may well have been an already-apparent negative trend for sales of the established range, likely due in large part to the cost factor. As 1961 unfolded, the company may have already been able to discern the writing on the wall and decided to defer any further financial commitment until the future of the range became clarified. However, none of this had been apparent back in 1960, when all had seemed well, at least as far as the ability of the established Rivers engines to compete in performance terms. Let's return to 1960 to consider the evidence for this. 1960 - Further Contest Successes

There was ongoing success at home as well. The June 1960 British Nationals proved to be a happy hunting ground for Rivers, the highlight being the Class A (FAI) team race win by the pairing of pilot Mike Smith of the High Wycombe club with pit-man Dave Balch of the Hayes club using Balch's works-supplied tuned Silver Streak Mk. II. This was the first British Nationals Class A win by any engine other than the Oliver Tiger, thus being a momentous occasion. A standard Silver Streak Mk. II also finished second in the Combat event in the hands of Hayes club member Robin Greenaway. The Silver Arrow was not left out of the results either, since Ted Coppard's "Uproar" model powered by one of these engines finished second in the R/C Multi class. Needless to say, Rivers made much of these successes in their advertising. Further notable results in 1960 included first places in Class A team racing at both the Enfield and Sidcup rallies in June and July respectively. At the August meeting at Ramsgate, the Silver Streak Mk. II powered the top three finishers in Class A. The engine also appeared in the finals at the prestigious Cranfield meeting, having set the fastest heat time of the day in the preliminary rounds. It capped all of this by winning the South Coast Gala meeting at Tangmere held in September of 1960. At the latter meeting, the winning team of Smith and Balch set the fastest heat time yet recorded in Britain at 4 min 39 secs. In fact, the Smith/Balch combination won all but two of the domestic events that they entered in 1960 - an impressive record!

The Silver Arrow quickly fulfilled Ron Warring's prediction that it would be a top contender in control line combat. Entries using the Silver Arrow finished first and second at the 1960 RAF Championships as well as winning the combat event at the Ramsgate meeting. The tuned Silver Streak also showed well in combat events, notably in the hands of Baz Bumstead and his famous "September Warrior" design. Things were definitely looking good for Rivers at this stage!

Moreover, the competition was intensifying. The April Published tests confirmed that the ETA was at least the equal of the tuned Mk. II Rivers Silver Streak. Moreover, it significantly undercut the price of the tuned Rivers at £5 19s 11d (£5.99) including taxes. The late 1960 release of the P.A.W. 249 Mk. III did nothing to help given the fact that this design came close to equalling the tuned Mk. II Silver Streak in standard trim at a very competitive price of only £4 18s 6d (£4.93) including taxes.

As a result of these developments, 1960 proved to be the one and only banner year for the Rivers range in terms of competition success. In team racing, the ETA 15D swept all before it in 1961, the team of Long and Davy winning everything in sight. Although Rivers made much of the reported "adoption" of the Silver Streak by the well-known Belgian team race expert and 1960 World Team-race Champion (using an Oliver) Nery Bernhard, things were not actually quite as implied by the advertising statements. Ian Russell recalled that the engine in question was the best-performing Silver Streak Mk. II ever made by Rivers and was sent to Nery Bernhard purely on a speculative basis in hopes that he would be sufficiently impressed to use it. Alas for fond hopes - as far as Ian was aware, Bernhard never actually used the motor in anger. In Ian's recollection, this particular example of the Mk. II Silver Streak was a real weirdo! It had a totally overhung shaft, with ALL the counterweight opposite the crankpin removed. Ian and his colleagues queried this, but Bert Rivers simply replied that the engine had been tested and found to be the best ever, so what could he do? In Ian's well-informed view, such a result could only have been achieved with an extremely heavy and solid bench mounting which absorbed any vibration. Ian's guess was that in a model it would have been a different story, hence Bernard's decision not to use the engine in competition. Perhaps he thought that it was Perfidious Albion’s attempt to derail the Belgian team! It seems that Bert Rivers continued to play with the Silver Streak, consequently producing the odd example which significantly outperformed the rest. Ian Russell had the "previous" best engine to emerge from the Rivers plant prior to the one sent to Nery Bernard. Apparently Ian's engine was a real stonker up to the time when he encountered a friend of his, one Pete Kilner, at a team race meeting. On this occasion, Ian didn't have a model but Pete did, albeit without an engine. It was of course a logical step to install Ian's mega-fast engine in Pete's model. All went well for the first few laps as they streaked ahead of the opposition (pardon the pun), but then the engine began to slow down, eventually stopping altogether. Subsequent investigation revealed that the crankpin had actually seized on the rod big end. Ian was far from happy, questioning whether or not the pan was true. Pete claimed that it was, but admitted a few years later that they had subsequently tried another engine in the model with the same result - the pan was not machined true! Ian's fabulous engine was never the same again. Things were little better in combat circles. The Silver Arrow achieved some success prior to the S.M.A.E. rule changes which initially restricted engines to .19 cuin. and subsequently required a plain bearing for engines over 2.5 cc (hence the plain-bearing P.A.W. 19D-II). However, competitors were becoming ever more aware of the importance of weight control in combat models, making the weight penalty of the Silver Arrow a real deterrent to its ongoing use in that discipline, its outstanding performance notwithstanding. The lower cost and impressive durability of the P.A.W. engines ensured their widespread adoption for combat use, and suddenly things were not looking good for the Rivers range. A Belated Response - The Silver Streak Mk. III

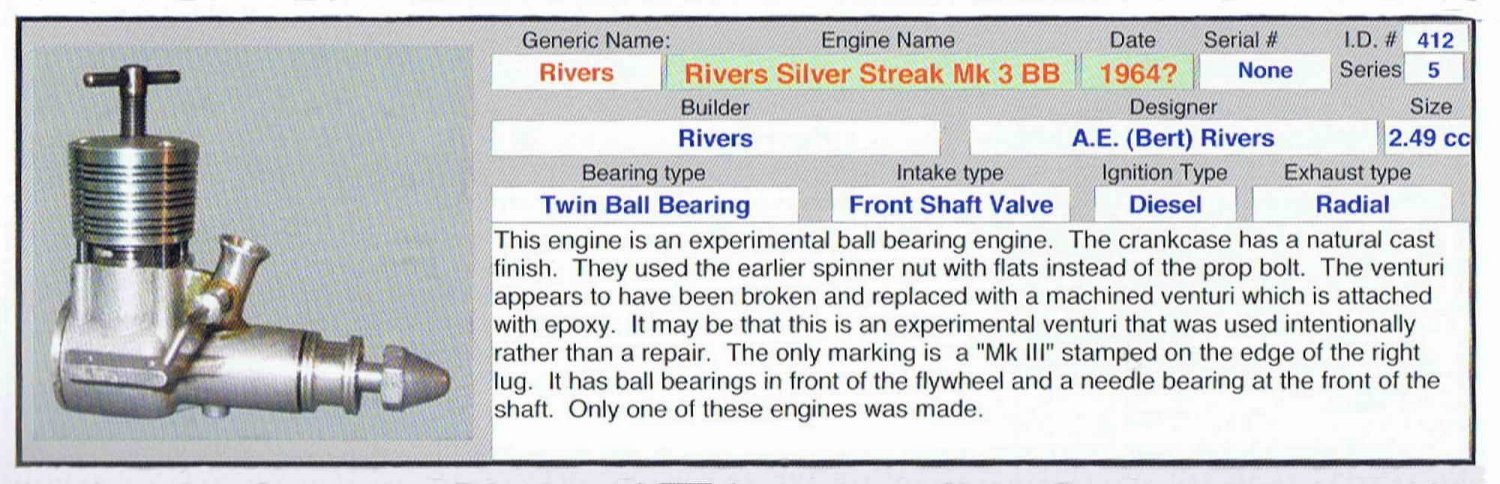

The engine in question appears as I/D #412 in the revised edition of Jim Dunkin's definitive book on 2.5 cc (.15 cuin) model engines. It appears that Rivers had finally accepted the previously-discussed fact that their needle roller bearing design had its drawbacks when applied to a model diesel engine. This particular unit has a ball-race at the rear of the shaft and a Rivers needle roller bearing at the front. It also features a modified venturi which has been epoxied to the standard Mk. II case, clearly as an experiment. Finally, the prop driver is a conventional component rather than the wrap-around item generally seen on Rivers engines. As discussed earlier, the combined ball-race/needle roller set-up is probably the arrangement which should have been used all along. The ball race would do a far better job of assisting with the axial loadings imposed by the airscrew, while the front needle roller bearing would provide excellent radial support to the One may wonder how they managed to squeeze a ball bearing of sufficient size into the (seemingly) standard Rivers Mk. II case. Thankfully, this question was answered definitively by my valued mate Miles Patience, who acquired this very engine in April 2023. It turns out that there was no inner race - instead, the inner track for the uncaged balls was machined directly into the surface of the shaft itself, which thus became in effect the inner race. This permitted the omission of the recess in the shaft which formerly accommodated the rear needle roller bearing, allowing the diameter of the internal gas passage to be increased to a monumental 0.285 in. (7.24 mm). The "Mk. III" designation stamped on the edge of the right-hand lug seems to provide clear evidence that this design was being evaluated as a replacement for the Rivers Silver Streak Mk. II. However, the late Jim Dunkin reported that only one example was made. The fact that the tuned Silver Streak Mk. II came as close as it did to matching the performance of the Oliver Tiger despite what I see as the handicap of the Rivers needle roller bearing arrangement is actually a testament to the effectiveness of the rest of the design. The above description should have clarified the fact that the rear ball bearing in the Mk. III Rivers Silver Streak was The downside was that the creation of the ball bearing using the crankshaft as the inner race involved precision grinding of an extremely high order with no room for the slightest error. This would have had an extremely adverse effect upon manufacturing costs. It was most likely the cost factor that led to the Mk. III Silver Streak failing to reach the production stage. Too bad - I suspect that the Mk. III unit could have been a very dominant force in the 2.5 cc diesel category. Some persuasive support for this view comes from another example of the Rivers Silver Streak which came into my hands in 2013. This was a Mk. I Silver Streak bearing the serial number A281. It had been comprehensively reworked, including the removal of much of the crankweb counterbalance as featured in the modified Mk. II example sent to Nery Bernhard. Of even greater significance, I found upon examination that it had been fitted with a ball-race at the rear of the shaft in place of the roller bearing normally featured. The construction appeared to be identical to that seen on the Mk. III prototype described earlier. The front roller bearing remained in place. The engine had by far the most free-turning shaft of any Rivers product of my personal experience. The performance measured for this example on test was nothing short of astounding! The engine was found to develop around 0.387 BHP @ 15,300 rpm - a simply remarkable performance which amply confirms the potential of the basic Rivers design. It also undercores the negative impact upon the engine's performance arising from the use of the Rivers needle roller bearing at both ends of the shaft. A full review of this very special unit appears elsewhere on this web-site. The End of the Road By mid 1961 it had become apparent to most serious modellers that the Rivers Silver Streak was no longer in the running as a top-flight competition diesel. The engine failed to achieve any notable wins in that year, the British Class A (FAI) team race season being totally dominated by the ETA 15D. Moreover, the relatively high weight of the Silver Arrow had become seen as a major impediment to its continued use in control line combat, causing many competitors to revert to the trusty and lighter Oliver Tiger and P.A.W. diesels. Baz Bumstead soldiered on for a while using his tuned Mk. II Silver Streaks, but he was very much in a minority in this regard.