|

|

A Forgotten Japanese Range - The Hope Engines

This article is actually a re-organization and enhancement of an earlier piece which appeared in installments on the late Ron Chernich’s “Model Engine News” (MEN) website beginning in June 2009. I’m re-publishing it here to prevent its loss as Ron’s now-frozen and administratively-inaccessible site steadily deteriorates due to the lack of any opportunity to maintain it. Before getting started, I'd like to go on record as stating that while I accept full personal responsibility for the content and conclusions set out herein, I couldn't have so much as attempted this survey without the invaluable assistance and encouragement provided by Alan Strutt of England and the late and much-missed David Owen of Australia. The late Ron Chernich also assisted enormously through his editorial and cyber-formatting efforts. The contribution of these three gentlemen was immense, and I freely acknowledge it here. I'd also like to remind the reader that the present article is an overview, not a detailed review of the engines which made up the Hope range. It includes relatively little in the way of technical information relating to those engines. Readers seeking more detail regarding the engines themselves are referred to my separate in-depth articles on the Hope 19 models, the Hope 29 series and the Hope Super 60 design. Now, on with the overall story, beginning as usual with some background. Background Following the September 1945 conclusion of WW2 in the Pacific theatre, the Japanese economy was in a shambles, as was the country's infrastructure. However, it was not long before reconstruction aid together with the economic boost stemming from the arrival of the predominantly American post-war occupying forces combined to re-awaken the enterprising spirit which had always been a characteristic of the industrious Japanese nation in "normal" times.

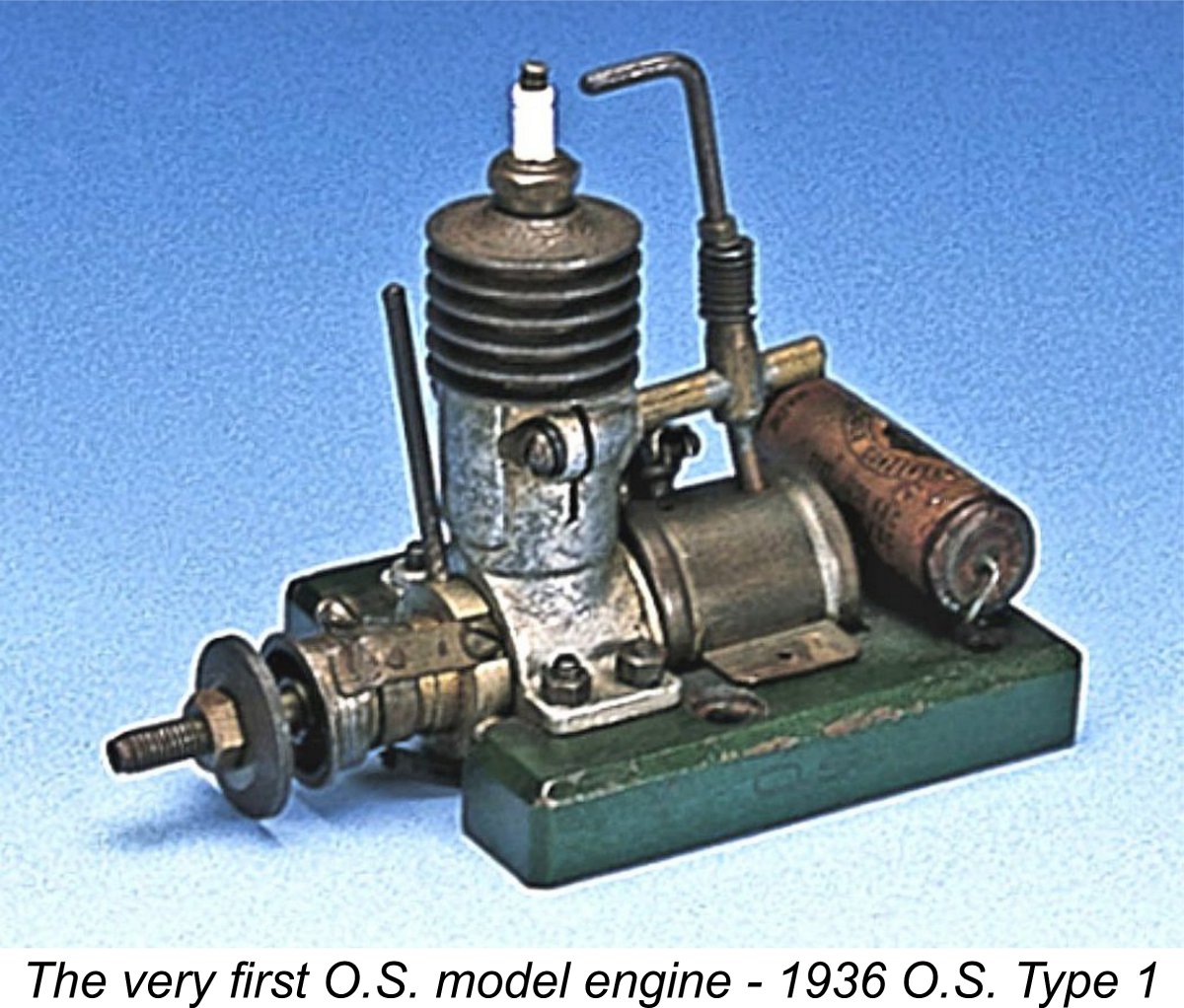

An article which was published in the July 1946 issue of "Air Trails" shed a great deal of light on this period. This article was written by Frank Nekimken, an American military troop carrier pilot who arrived in Japan with US forces a few days after VJ Day (September 2nd, 1945). The article included the substance of an interview with Mr. K. Shimozin, owner of Tokyo's largest model shop (which had somehow resumed business following the wartime bombing) and then-President of the Japanese Model Industry Association. Apart from his retail activities, Mr. Shimozin had been a major kit manufacturer for some thirty-four years at the time of the interview. Before the B-29's wiped out his factory, he had been Japan's largest kit producer, employing 12 men who produced approximately 12,000 kits per month. This included both flying and static models. Mr. Shimozin reported that there had been as many as three hundred kit manufacturers in Japan prior to the war. Their products were marketed through some seventy wholesale jobbers and 600 retail outlets nationwide. Clearly a thriving industry! The article pointed out that the building and flying of kites and model aircraft had been part of every child's education both before and during the war. Aircraft recognition had been an integral part of the wartime school curriculum. As a result, Nekimken went so far as to state his view that there were almost certainly more model airplane builders in Japan than there were in the USA! Of particular relevance to the present discussion, Mr. Shimozin advised that some ten percent of Japanese aeromodellers were involved with power modelling. This level of interest supported the activities of some 10 model engine manufacturers, who produced around 500 engines monthly between them. Most notable among these was the O.S. marque which had become well established in Osaka following its initial market entry in 1936 and had even succeeded in penetrating the pre-war US market to a small extent. But O.S. was far from being alone - Mr. Shimozin confirmed that there were quite a few other pre-war Japanese makers. This situation has always been greatly under-appreciated in Western modelling circles because the pre-war Japanese power-modelling scene had been invisible to the non-Japanese speaking world due to language and political barriers. But the fact is that many of those who became involved with model engine manufacture in Japan after the war actually had considerable prior experience in the model engine field. This was far from being merely a group of talented but inexperienced imitators who were learning from others on the job, as is often assumed - in fact, we're speaking here of a number of experienced power modellers resuming an activity that they already understood very well indeed.

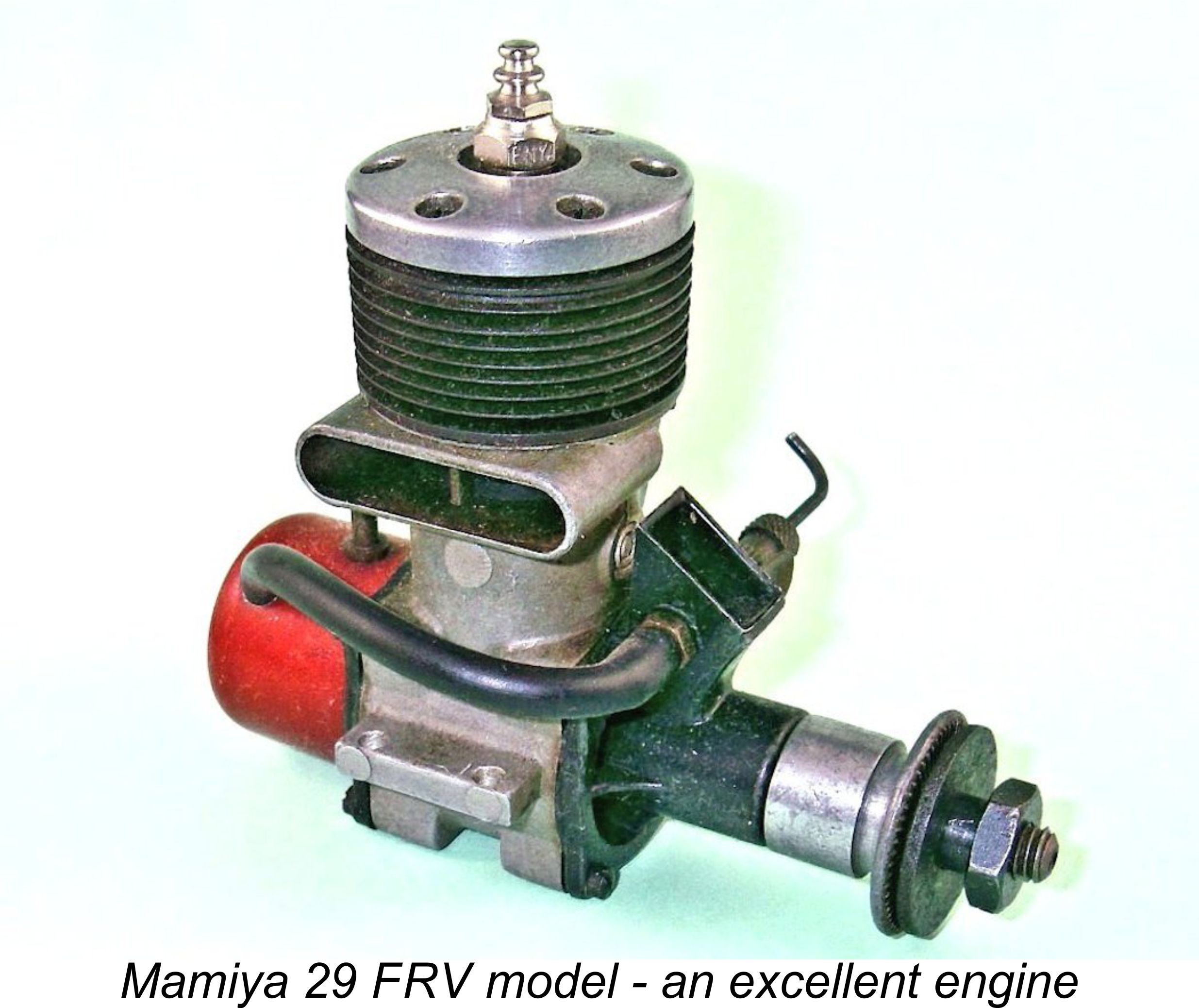

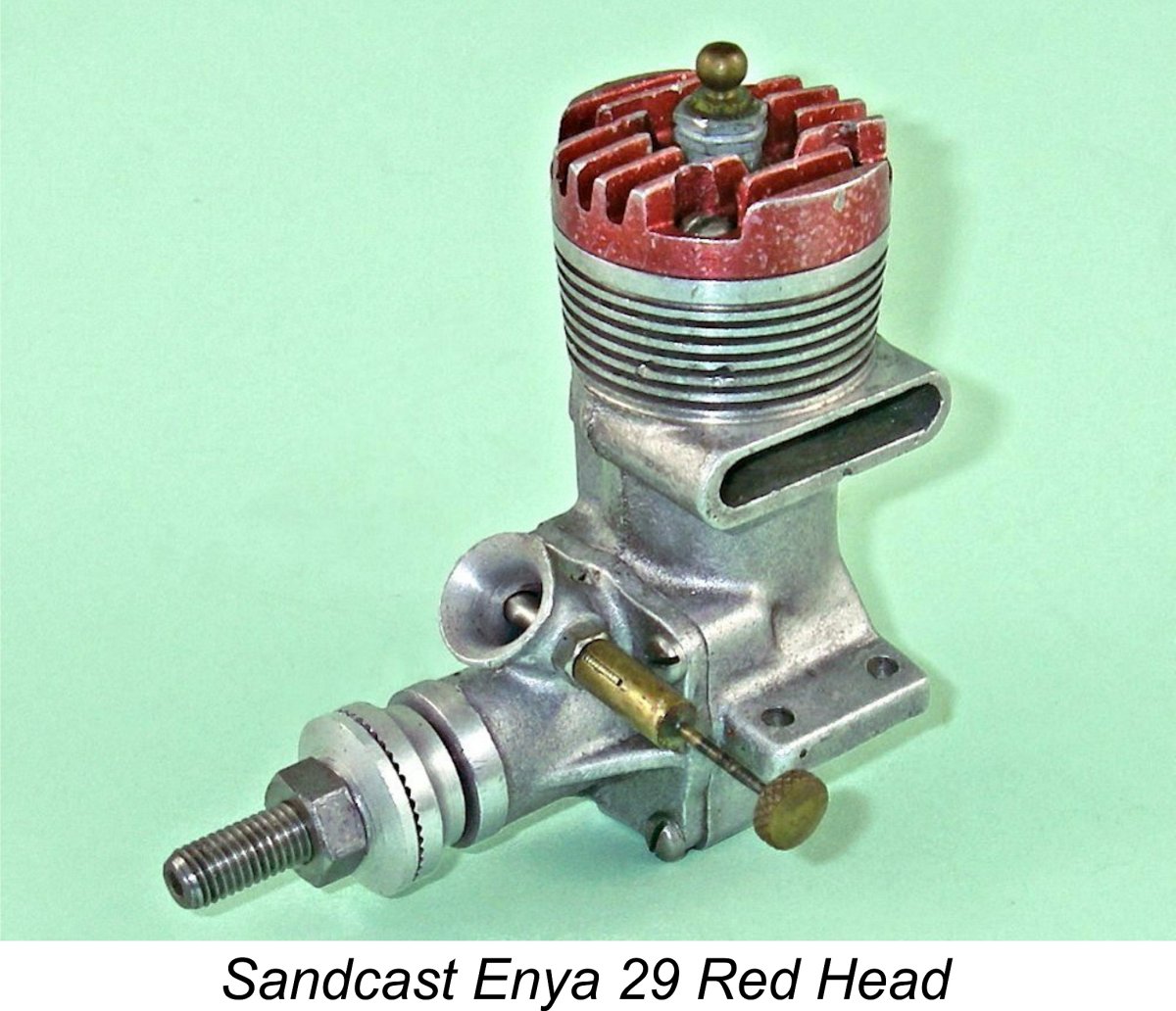

All of the above names are doubtless familiar to the majority of today's modellers. The O.S. and Enya companies are still engaged in the model engine business, albeit with very different and up-to-the-minute product lines by comparison with their early post-war offerings, reflecting the very different nature of the present-day modelling scene. The makers of the Mamiya range ceased model engine production in the latter part of the 1950's, but the Mamiya name remains famously associated with camera manufacture.

The last Hope model engine came off the line almost 70 years ago (as of 2025) and the origins of the Hope range are now very much obscured by the passage of time, at least as far as most observers in the English-speaking world are concerned. No doubt there are a few Japanese enthusiasts who know a great deal more than I do about the history of this now-obscure marque, and I’d be delighted if the re-publication of this survey served as a catalyst for the sharing of further information on the Hope range. Indeed, that's one of my primary motivations in placing this material before my readers in the full knowledge that it must surely contain errors and omissions. In the virtual absence of first-hand English-language references to the Hope range, the best that can be attempted is the documentation of the known range in technical terms, using a number of examples to which I have access as my primary information sources. I recognize very clearly that I may well be missing some Hope products of which I’m presently unaware. Any further information from readers in this regard would be most welcome. In the meantime, the publication of such information as is presently available is surely better than doing nothing at all! I wish to make it very clear that all dates given in this survey must necessarily be treated as speculative at best. There appears to be little doubt regarding the order in which the various models appeared, but there is no certainty whatsoever regarding the actual dates upon which they were introduced. I’ve simply suggested dates that appear probable to me based on the very limited evidence in my possession. I’m very much open to well-informed correction! OK, time to get started on my summary of this interesting and long-neglected model engine range! In The Beginning

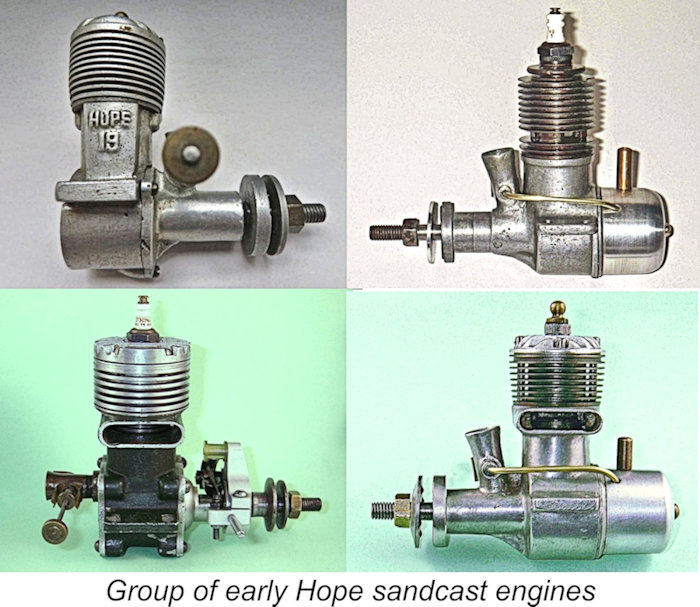

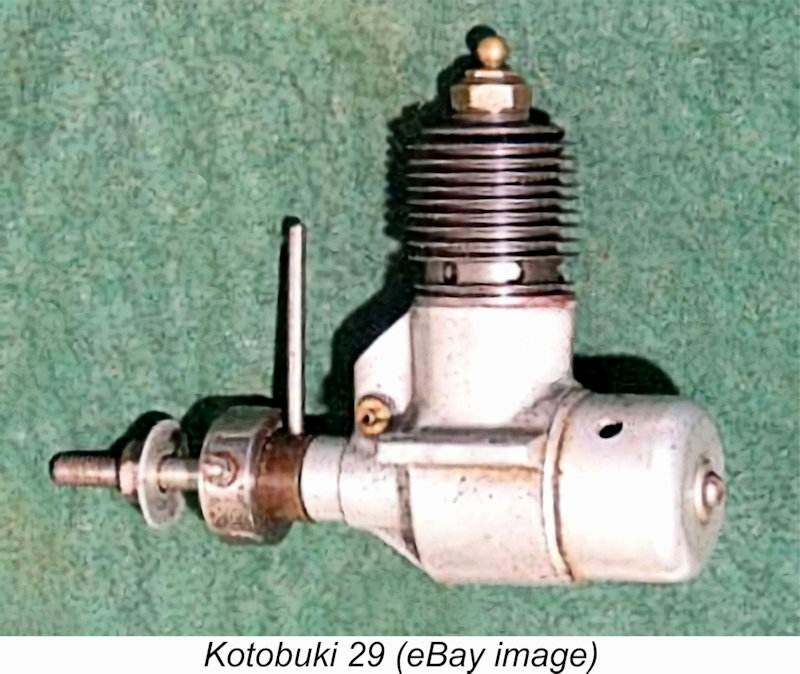

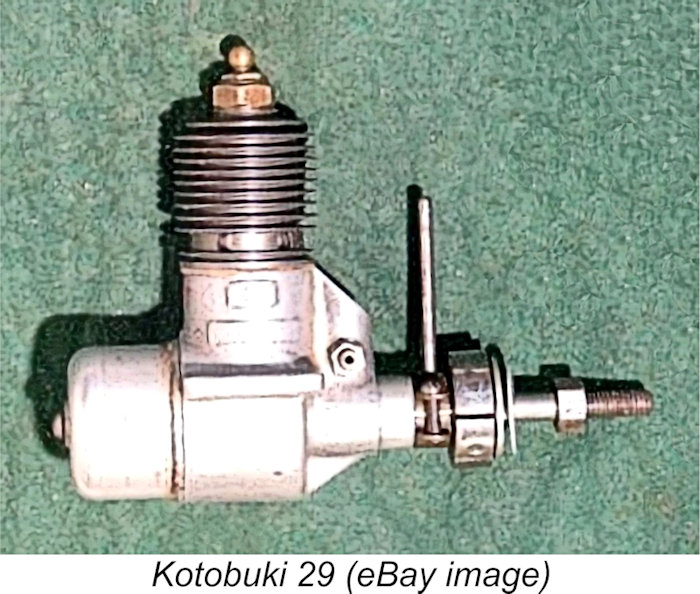

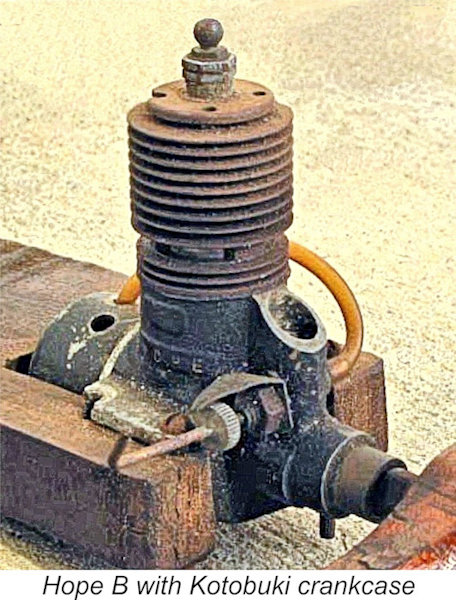

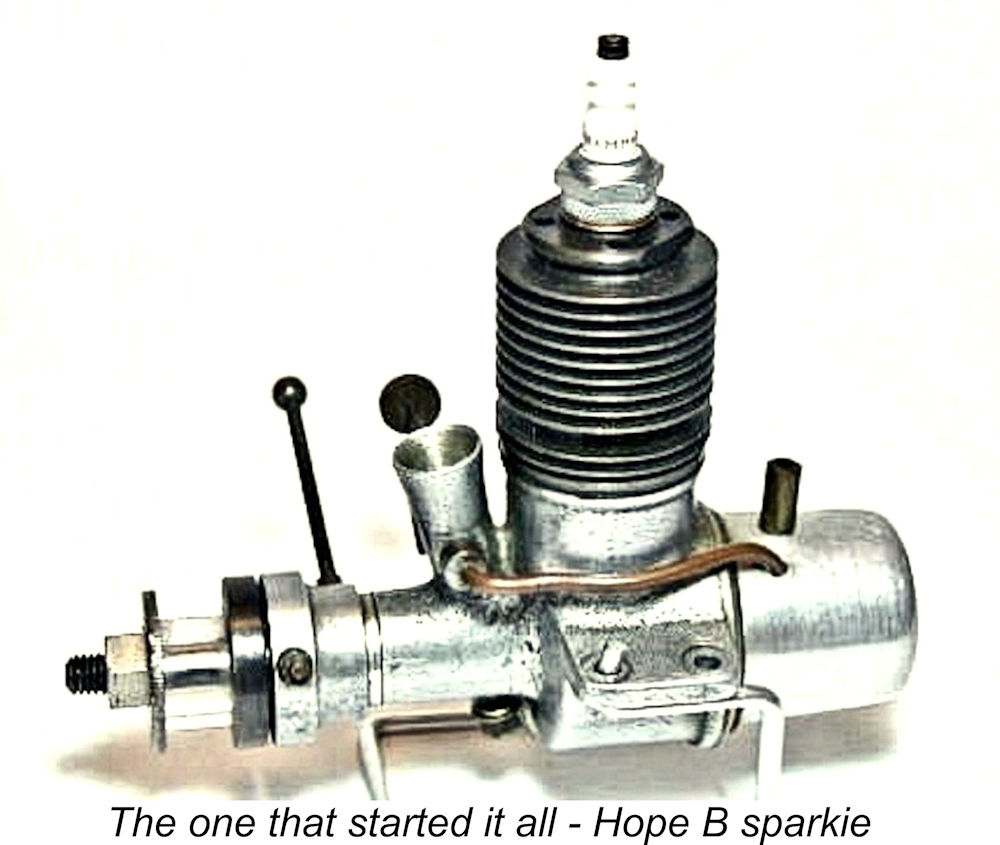

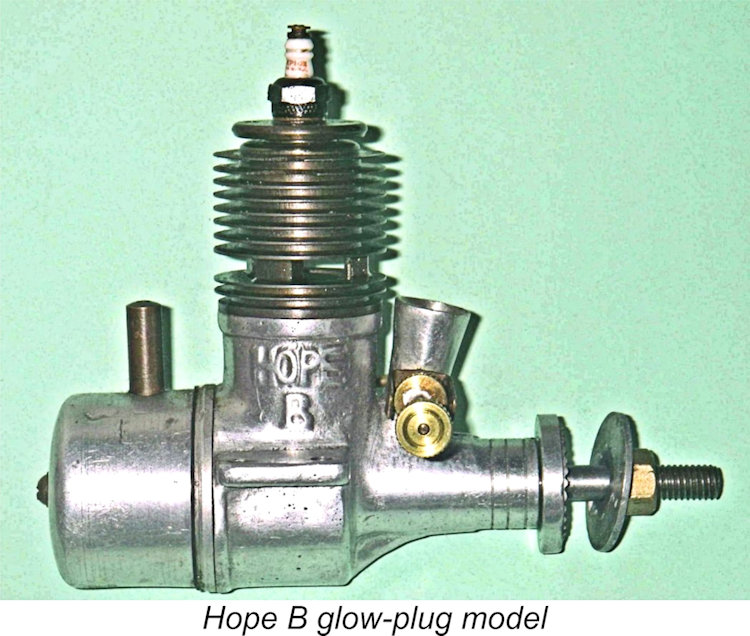

Mr. Sato's only reported Kotobuki product was a 5 cc (.29 cuin.) spark ignition model which bore a very strong resemblance to the later Hope B model - indeed, the similarities are far too marked to be coincidental. My Japanese informants went so far as to state that the Kotobuki manufacturers changed All that I can presently say for sure is that, like the rival Enya, Fuji, KO, and Mamiya concerns, the manufacturers of the Hope engines were located in Tokyo. They traded under the name Hope Engineering Company, at least in English-speaking markets. This information is to be found on the boxes Indeed, the engines themselves are far from common outside Japan, reflecting the fact that relatively few of them appear to have been sold outside their country of origin. It seems evident that for reasons which will forever remain obscure the company never succeeded in mounting a truly effective international sales campaign like those of O.S., Enya and Fuji. No Hope engine was ever the subject of a published test in the English-language modelling media. It's unclear exactly when the Hope range first appeared, although there are a few indicators from which some reasonable conclusions may legitimately be drawn. The earliest known Hope model (the Hope B) unquestionably started life as a spark-ignition engine which was very closely based upon the Kotobuki 29. It went through several variants in that form before being reconfigured as a glow-plug model. This implies that the range must have been founded during the spark ignition era, i.e., prior to 1948. That said, the relative scarcity of surviving examples of spark-ignition examples of the Hope B by comparison with the somewhat more common glow variants implies that the line first appeared near the end of the spark-ignition era, perhaps only a year or so prior to the commencement of the transition to glow-plug ignition. This transition commenced somewhat later in Japan than in Western countries, probably due to the non-availability of the necessary platinum-iridium wire in early post-war Japan. The commonly-quoted range start-up date of 1947 for the Hope range seems entirely consistent with these observations, although an earlier start-up cannot be ruled out. 1947 - The Early .29 cuin. Models As noted above, the first identified product of the Hope company appears to have been the 4.83 cc (0.295 cuin.) Hope B spark ignition model which is illustrated above at the left (timer missing). As far as I’m presently aware, there never was a Hope A, so it seems almost certain that the letter B referred to the competition class for which the engine was dimensioned.

The Hope B was a plain-bearing crankshaft rotary valve spark ignition unit of extremely simple design. The engine featured a sand-cast aluminium alloy crankcase and a blind-bored cast iron cylinder with integral cooling fins and radial porting. The cylinder was to all intents and purposes identical to that of the earlier Kotobuki 29 model, although the cylinder porting differed in detail. The case too was generally similar, as was the overall form of construction. The most obvious externally-visible change was the intake, which continued to be integrally cast but was now a free-standing feature as opposed to an expansion of the upper crankcase at the front. Both the cylinder and the backplate of the Hope B were of the screw-in variety, no screws being used in the main assembly. A very neat enclosed timer was fitted. The engine was equipped with a metal back tank, as were many of the Hope models yet to come. Fuel was supplied through a 2 mm dia. brass tubular fuel line - it appears that fuel-resistant plastic tubing was not readily obtainable in Japan at this time.

It was for this reason that Japanese model engines during this period tended to be considerably lighter, simpler and apparently less substantial than their overseas counterparts. However, their performance generally lagged little if any behind that of their heavier and more complex foreign competitors. The reputation for fragility that they deservedly acquired in these years was unquestionably due far more to the limited availability of suitable materials than to any design or construction shortcomings. The Hope B is described in detail in my separate article on the Hope .29 cuin. models. For present purposes it will suffice to say that from its beginnings in 1947 the design went through several variations in spark ignition form before being reconfigured (probably in 1948) as a glow-plug model. It passed through several variants in that form as well prior to its eventual replacement (likely in early 1950) with the first of the "New 29" models to be mentioned below. The Hope B name was cast in relief onto the right side of the engine's crankcase. It seems worthwhile pausing at this point to explain the significance of this fact. Prior to the conclusion of WW2, the use of non-Japanese characters on Japanese products was forbidden by the Japanese government. But as soon as that prohibition ended following the war, Japanese manufacturers immediately began to fall over themselves using Anglicized names for their products. In doing so, they tended to name their engines from a completely different perspective to that of their Western counterparts. The chosen names often reflected the related concepts of excellence, power and progress, as exemplified by such evocative names as TOP, Peak, Top Class, Great Leap Forward, Cherry, Mighty, Boxer and indeed Hope. An interesting example of the post-war evolution of these principles stemmed from the widespread pre-war and wartime use of the name Jin Puu (or Gin Fuu), meaning Great Wind - after WWII this evolved into Typhoon, a name which was used extensively in the 1950's by Enya.

Moreover, there was at the time a widely-held yet increasingly unjustified view among Japanese modellers themselves that overseas modelling products were somehow superior. Consequently, the use of Anglicized names was doubtless intended in part to impart a certain international "cachet" to the products to which they were applied. Whatever the reasons, Japanese manufacturers were extremely quick to take maximum advantage of their post-WW2 freedom to use non-Japanese characters. The Hope B appears to have been the "bread-and-butter" product of the new company, sales of which would keep food on the table and support the development of further models. It thus fulfilled a very important role for the new company during the initial start-up period. However, there were other forces at work in the Japanese modelling scene of the early post-war period, which Hope could not ignore. These resulted in the early appearance of the next Hope model to be produced - the Super Hope 60. 1948 - The Hope Super 60 Arrives

This seeming Japanese preoccupation with the big-bore displacement category during the early post-war period deserves an attempt at some kind of rational explanation. It cannot have been motivated by expectations of mass domestic sales of such engines in the war-ravaged Japanese economy of the day, so we must look elsewhere for the reasons. Firstly, it's necessary to recall that this displacement category had been very popular in Japan prior to WW2. O.S. made several such models prior to and during Japan's involvement in that conflict, as did the Great Japan Model Aeroplane Co. Ltd. with their popular pre-war K-Class models in 5 to 10 cc (.29 to .61 cuin) displacements. There was doubtless something of a "hang-over" effect in play - the individuals involved resumed their activities by designing, building and flying what they knew.

It's also undeniable that there may well have been a desire on the part of the Japanese makers of these engines to show their WW2 conquerors that despite their recent defeat in war their capabilities and their competitive spirit remained undiminished. Such feelings would be completely understandable and would certainly add impetus to the efforts that so many of them made to create engines which could take on the best that their American occupiers could muster. This point would be particularly emphasized if these engines could be showcased in the hands of Japanese modellers in successful competition with their American counterparts. It seems very probable that the achievement of competition success or at least respectability in the hands of Japanese modellers sat right at the top of the priority list for the manufacturers concerned and that sales (or perhaps even donations) to leading Japanese competition fliers would have been their primary goal. But bragging rights and national pride alone would not have sustained the manufacturers. To actually earn a living, they had to sell engines in viable numbers and make a profit in doing so. To accomplish this, the selling price had to be to be set sufficiently high for a profit to be realized on each unit sold, and a sufficiently large pool of empowered buyers had to be accessed.

The Japanese post-war situation was considerably less favourable due to the extremely negative impact which the war had exercised upon the Japanese domestic economy and the consequent shortage at that time of "rich adult men". The value of the yen had plummeted and it was hard times all round, with economic survival as the main imperative. The purchasing of a high-priced "luxury" item such as a large model aero engine would not have ranked high on the priority lists of many Japanese citizens at this time. Furthermore, access to overseas markets was essentially non-existent during the early post-war period.

One such factor was undoubtedly the sudden arrival in Japan in September 1945 of the numerous and predominantly-American army of occupation. American modellers had long been attracted to larger models, and it seems likely that the big-bore Japanese engines which appeared in the late 1940's and early 1950's would have attracted at least some attention from the numerous American service personnel having an interest in modelling. These individuals had discretionary spending power far in excess of that of the average Japanese citizen in the war-ravaged Japanese economy of the day, thus constituting a ready-made customer base for those engines which were surplus to the requirements of Japanese modellers. In effect, the Americans acted as an "overflow" market for Japanese manufacturers, ensuring that they would be able to sell all of these large and relatively expensive units that they could produce. There was no such overflow market available to Nordec in Britain. Not only that, but the Americans could pay in dollars, which converted into a lot of the devalued yen of the day. As a result, profit margins on sales to Americans could well be significantly higher than for domestic sales and hence might subsidize sales or donations to Japanese modellers. It also appears likely that the idea of getting some of these larger "prestige" engines into the hands of American modellers was seen by the more forward-looking emerging Japanese manufacturers as an excellent way of promoting their capabilities with a longer-term view towards export of their products to the North American market. Sound thinking if this was indeed the case, and it certainly paid off handsomely in the long run for at least some of the companies involved!

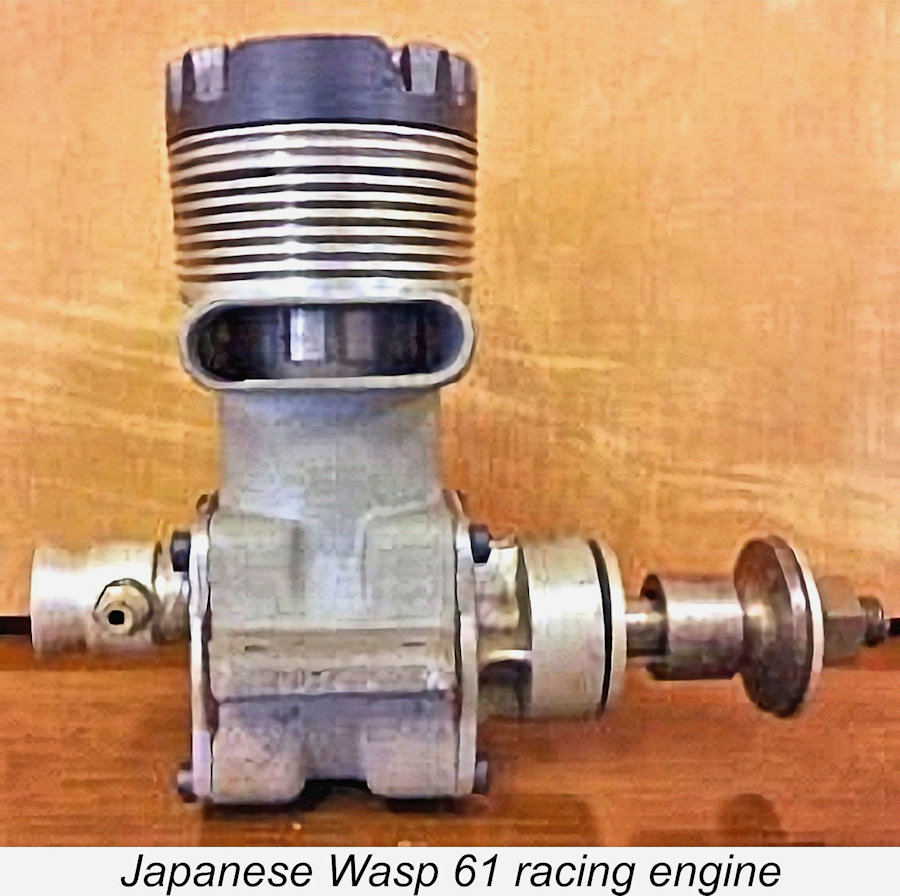

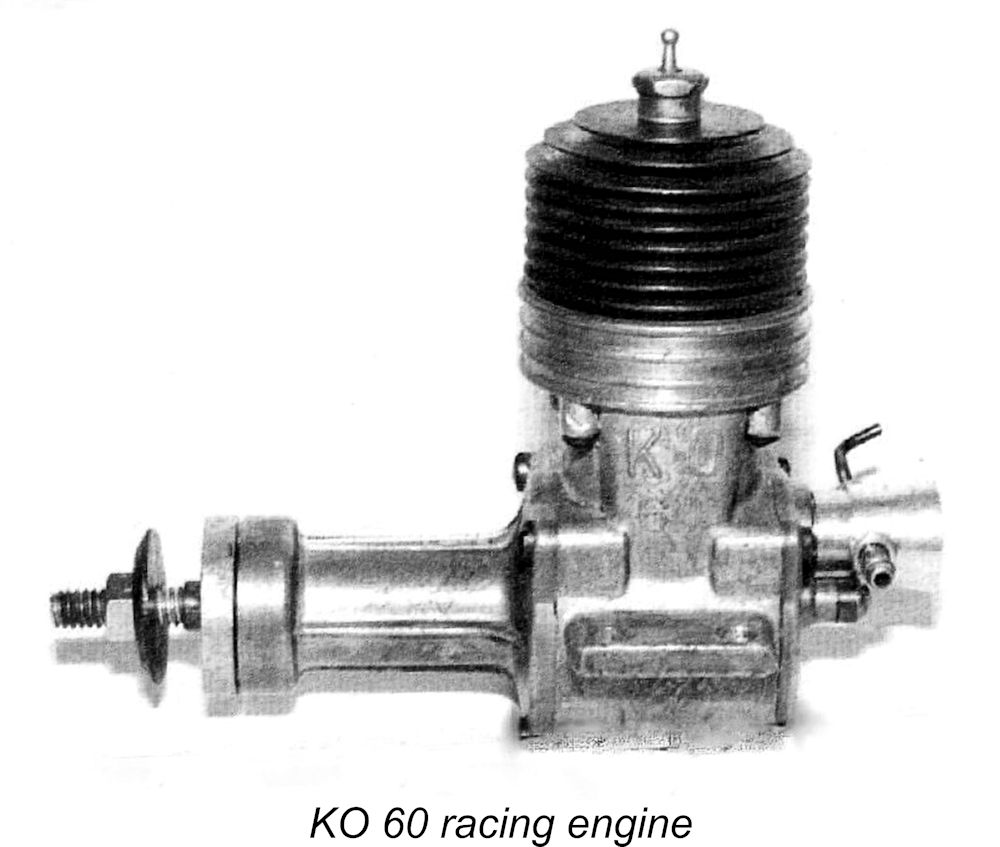

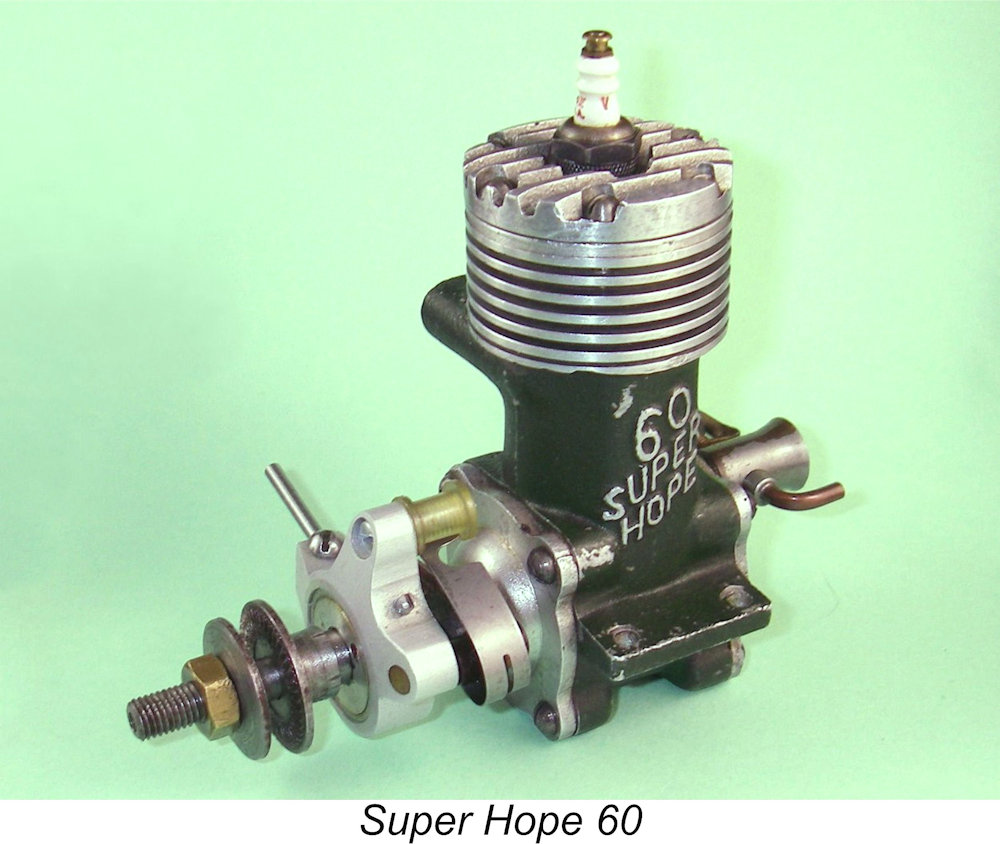

The post-war Japanese manufacturers were quick to recognize this situation and to diversify their production into more popular categories. This ensured them an adequate The Hope Engineering Company certainly followed this pattern. Having first established their "popular" product line in the .29 cuin. category with the Hope B, they then jumped onto the large-engine bandwagon, producing a finely-crafted 10 cc rear disc valve racing-type model in both spark ignition and glow-plug versions while maintaining production of their bread-and-butter 29 model. This racing model was known as the Hope The fact that this engine was produced in both glow-plug and spark ignition versions implies that it was most likely introduced in 1948. However, I cannot claim any certainty for this date – I merely cite it as the most probable date based upon the surrounding circumstances. This would make it a contemporary of the Nordec engines mentioned earlier. Although a fine engine in its own right, it's extremely doubtful that the Super Hope 60 did much to bolster the financial position of the Hope Engineering Co. The Hope B was presumably their staple product at the outset, but long-term survival would undoubtedly require expansion of the range into other "popular" displacement categories. Based upon the presently-available evidence, it appears that the company management looked next at the .19 cuin. displacement category as a potentially lucrative market area in which they might hope to compete successfully. 1949 - The First Hope 19's

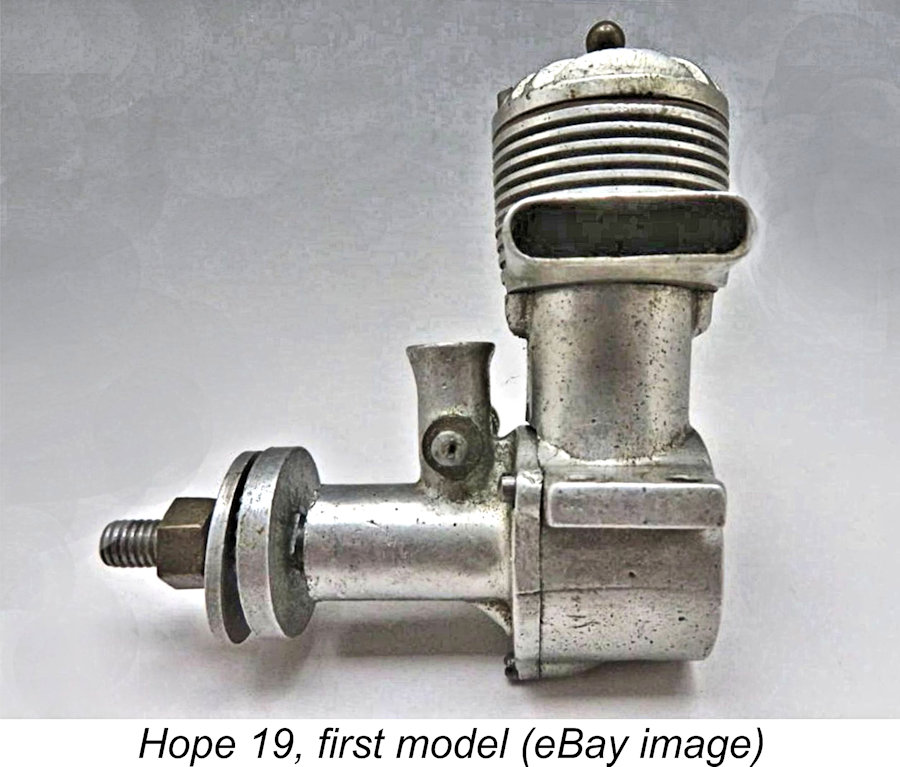

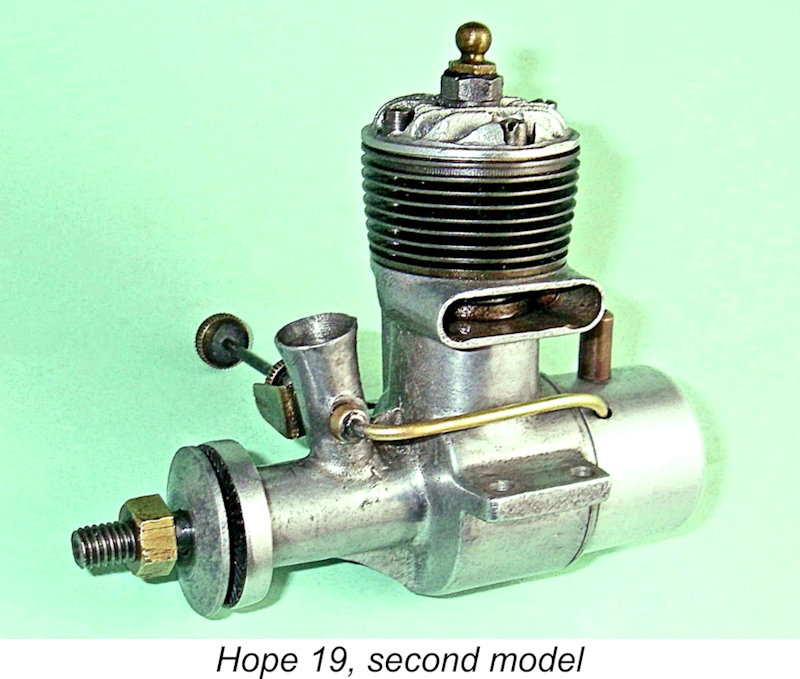

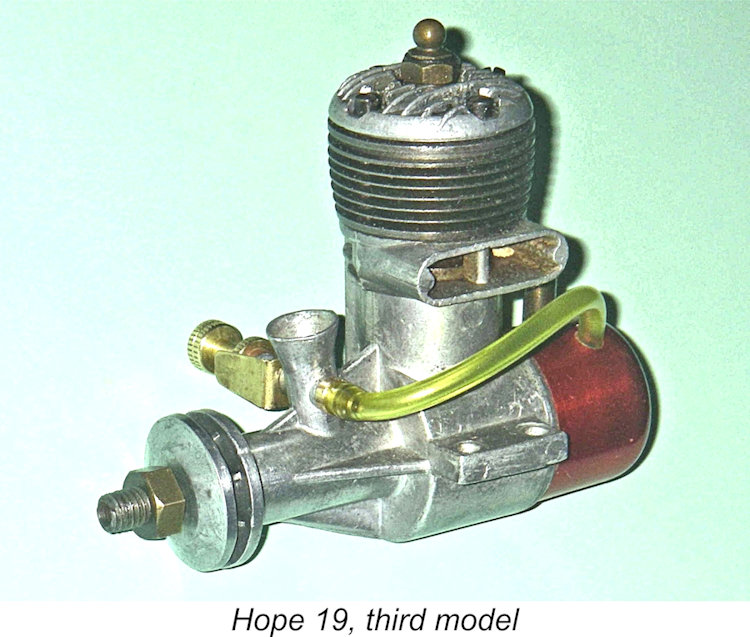

Apart from the significantly more up-to-date design, the fact that there is currently no evidence whatsoever that a spark ignition version of the 19 was ever produced by the factory implies that it arrived on the scene in its sandcast form somewhat later than the Hope B and the Super Hope 60, most likely in 1949. It seems probable that it pre-dated the far better-known Enya 19, which first appeared in early 1950 as a sandcast model. It is perhaps best seen as a contemporary of the competing KO 19 model of 1948/49.

Detailed descriptions of these very rare engines will be found in my separate article on the Hope .19 series. The relative scarcity of surviving examples of these sandcast Hope 19 models suggests that they were in production for only a relatively short time. 1950 - The Die-casting Era Arrives As always, it's impossible to be certain about dates, but it appears reasonable to suppose that it was in early 1950 that Hope initiated the next major step towards enhancing their manufacturing capacity and hence broadening their potential sales base. This was the general application of die-casting to the production of their range.

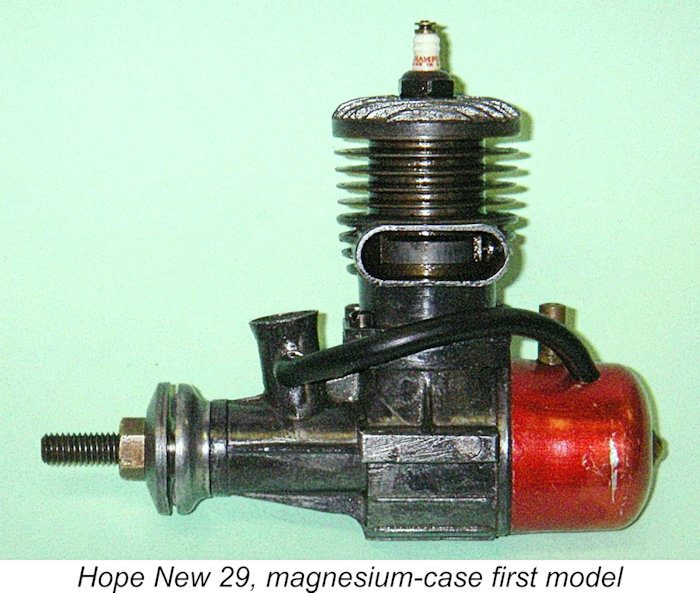

And indeed improvements were necessary by this time if Hope was to retain any kind of market share - their rival Japanese manufacturers had by no means been idle! Mamiya, Fuji, KO and O.S. had all introduced new glow-plug .29 models in 1949, and all of these handily outperformed the by-then out-dated To their credit, Hope's response to this situation was both vigorous and seemingly effective. They quickly produced a completely revised .29 model in the form of the Hope "New 29", also developing a rather less radically updated revision of their original .19 model. Both of these revised designs were based upon die-cast alloy components, indicating an expectation that production figures would increase in response to demand for the updated products.

The cylinder retained the integral cooling fins and blind bore of the Hope B but now featured cross-flow loop scavenging in place of the former radial porting. It was secured to the upper crankcase casting with a pair of internal spot welds in a fashion somewhat reminiscent of the American O&R models, although in the case of the Hope New 29 these welds were applied from inside the bore, hence being externally During this period, the engines were attractively presented in red-and-yellow boxes with black lettering. The instructions were supplied both in Japanese and very clear English, indicating ambitions to market the engines outside Japan. However, it seems clear that the domestic market remained of primary importance, and Japanese sources advised that the Hope range enjoyed considerable popularity in Japan during the early 1950's. This is borne out by the fact that development of both models continued throughout this period. Without encouragement from the marketplace, it's hard to see this occurring. 1952 - The Range Is Further Updated

However, these changes were insufficient to counter the parallel moves of other domestic manufacturers, most notably Enya. In April It was time once again for Hope to choose whether to respond to these market challenges or to throw in the towel and move into other areas of manufacturing activity. To their credit, they chose to stand and fight. They did so with a completely revised and expanded range of engines in three displacement categories. 1953 - The Hope "Super" Series

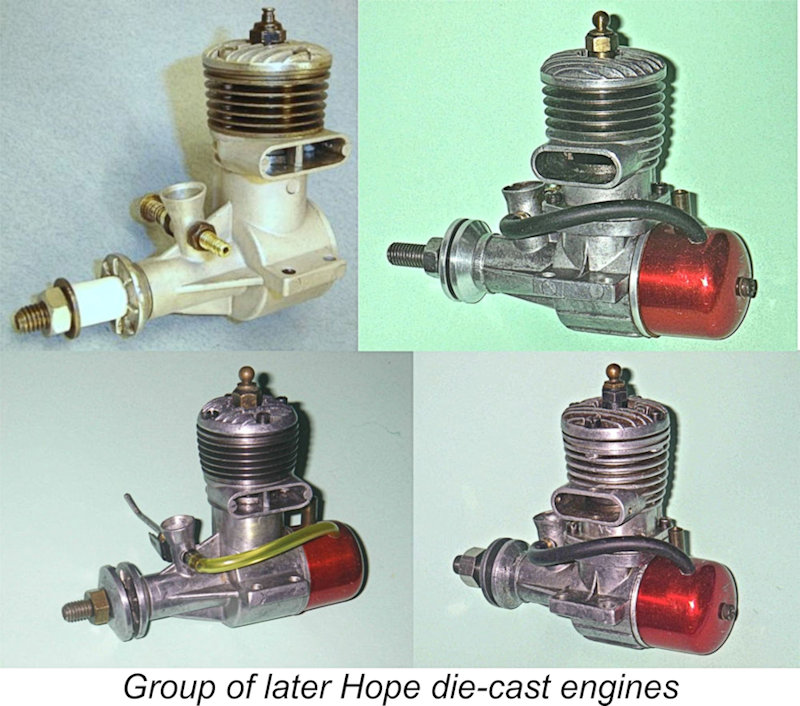

It's not completely clear when these revised models appeared, but the preponderance of available evidence suggests that the "Super" Hopes began to appear in the latter part of 1953 in response to the challenges then being mounted by Enya and others. The style of the boxes in which the engines were marketed was also changed at the time of introduction of these "Super" models. The new box was decorated in a two-tone blue pattern with white bordering and a combination of yellow and white lettering. The engines were identified exclusively in English on the boxes. English-language instructions continued to be provided, indicating an ongoing ambition to market the engines in the English-speaking world. The Hope Super 29 was so identified on the die-cast crankcase as well as on the box. This was in rather odd contrast to the Super 19 model, which was only identified as "Super" on the box.

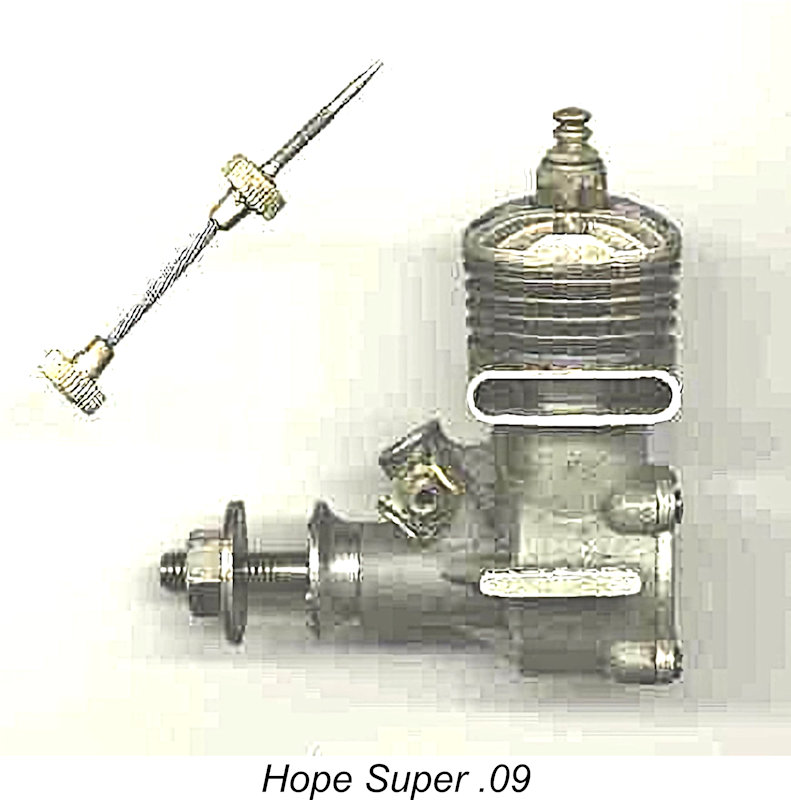

The revised models were up-to-date loop-scavenged designs of completely conventional layout - typical general-purpose lightweight glow motors of their day, in fact. The cylinders with integral cooling fins were retained, albeith now being made of steel. The crankcases were completely revised - the screw-in backplates and back tanks of the earlier designs were gone, being replaced by conventional backplates attached using four screws. The externally-threaded needles were retained as they had been all along, but now had a flexible cable extension instead of the former solid thimble. The cases were given an attractive vapour-blast matte finish. This family of engines was very well made and had a pleasingly neat and uncluttered appearance. Based on present-day testing, performance and durability were well up to then-current standards for plain-bearing general purpose engines of this genre. Detailed descriptions of the Hope "Super" models will be found in the separate articles which deal with the evolution of the various displacement categories. The Hope .09 Model I’ll conclude my review of the Hope range with a necessarily brief look at another of the more elusive Hope models - the "Super" .09 design. This was one of the final offerings of the Hope company, arriving on the scene relatively late. Examples are few and far between - indeed, I have never managed to gain access to one myself up to the present time, and I only have a single image. Still, in the interests of presenting a complete survey of the known Hope models, I'll do what I can.

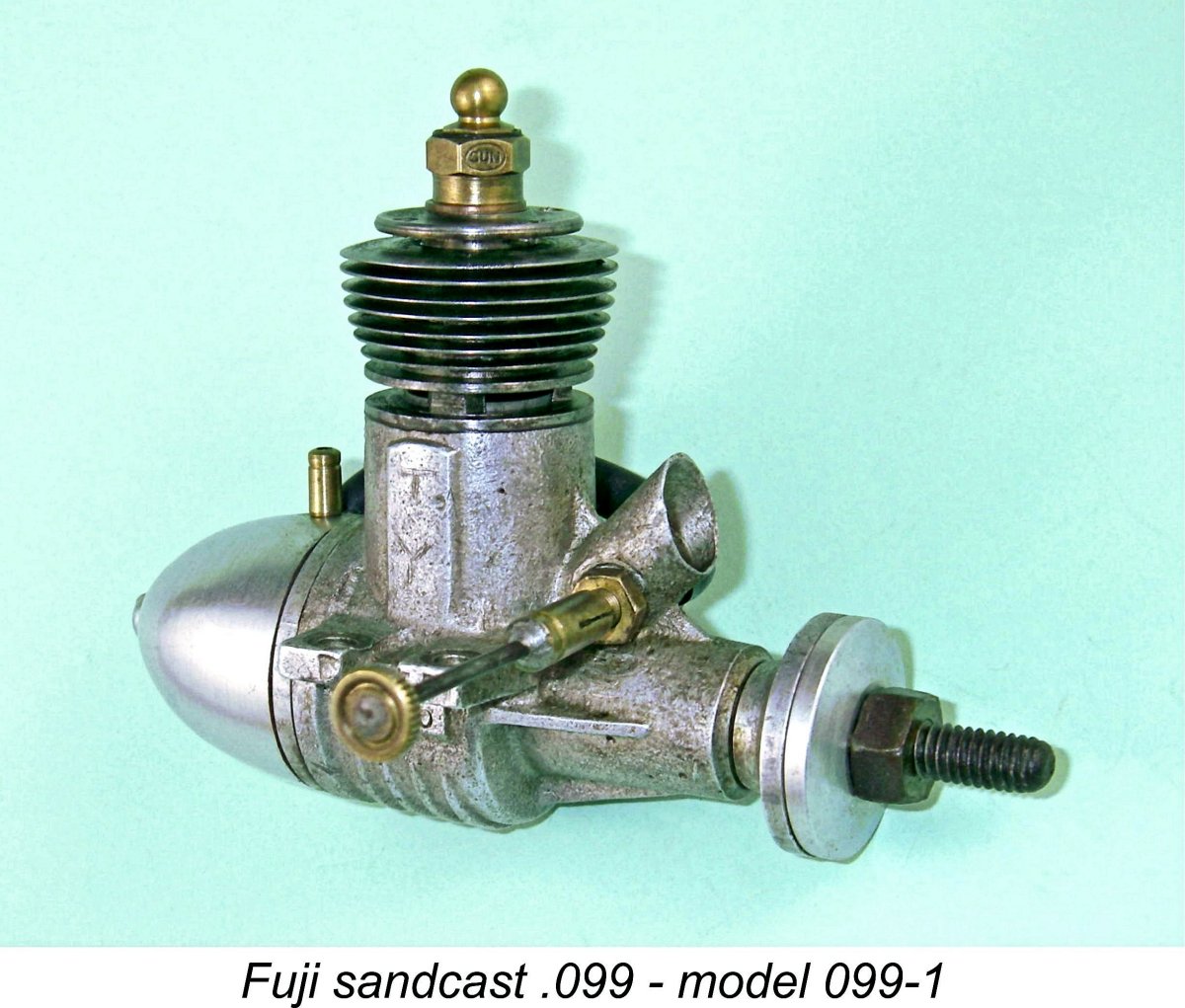

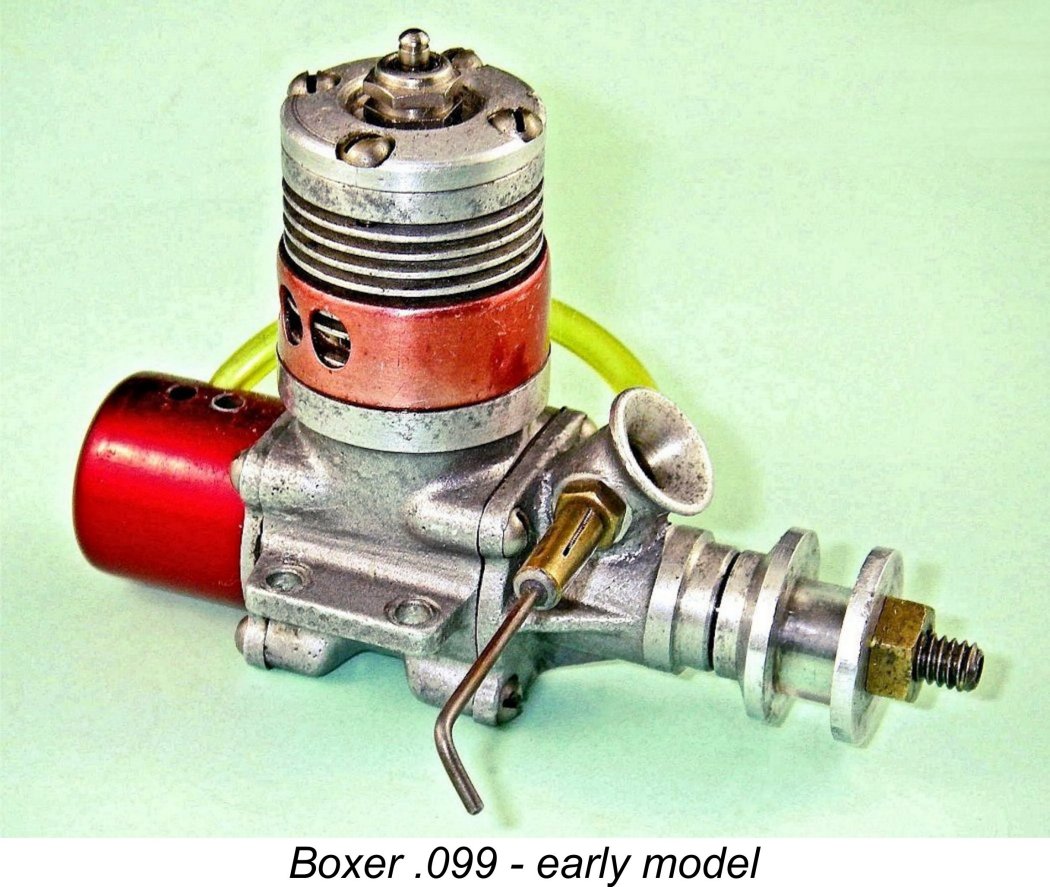

Mr N. Haruyama seems to have been among the first individuals to manufacture model engines in this displacement category, doing so beginning shortly after the conclusion of WW2 and being joined fairly quickly thereafter by Mamiya and Fuji. O.S. re-joined the .099 party in 1950, the makers of the almost-forgotten By contrast, the .049 displacement category was largely ignored by Japanese manufacturers during the 1950's, only Fuji and the ultra-obscure ROC and Haru companies producing .049 models during that period. Of these, the Fuji offerings were by far the most popular. This being the case, it's rather odd to report that at present there's no persuasive evidence for Hope having entered the .099 market prior to late 1954 or perhaps even 1955. By this time the market was pretty well saturated with established high-quality Japanese-made products I noted earlier that the "Super" versions of the .19 and .29 engines seem to have begun to appear in late 1953 or thereabouts. Such evidence as has come to my attention to date suggests that the .09 model arrived at some point after that date. Certainly, Peter Chinn's 1954 international glow engine survey (“Model Aircraft”, May 1955) contains no reference to any Hope .09 model, although both the .19 and .29 models are included. However, it's clear that before ending their involvement with model engine production, Hope did make one effort in the .09 class. This took the form of an .09 version of their contemporary "Super" series which also included the previously mentioned .19 and .29 cu. in. models. The .09 cuin. version of this engine was mentioned in the survey of the world's model engines published in early 1958 in the book “Model Aero Engine Encyclopaedia”, but actual examples are almost never seen outside of Japan.

Bore and stroke of this very elusive model were given in the previously-cited 1958 survey as a "square" 12.7 mm by 12.7 mm for a displacement of 1.61 cc. The weight was given as a commendably light 1.75 ounces, comparable to that of the contemporary Mamiya .099. Operating speed range was given as 8,000 - 14,000 rpm. In the absence of an actual example to examine, I’m unable to provide more specific information at this time. This was among the final products of the Hope Engineering Company. As mentioned earlier, production of all Hope models appears to have ceased at some intermediate point in the latter part of the 1950's, most likely in 1957. It's true that the range was mentioned in the early 1958 survey noted above, but inclusion in that list cannot be taken as conclusive evidence of ongoing production as of 1958 - a number of other engines on the list were unquestionably out of production by that time. The End Of The Line The Hope "Super" models just summarized proved to be the final products of the Hope Engineering Co., at least as far as I’m presently able to determine. It appears that a number of these engines were sold in the US market - I have encountered several old-timers who claimed to have purchased them new in the States during the mid-1950's, and I also have a box bearing a price indication in dollars. However, it's clear that the results of Hope's international marketing efforts fell well short of meeting expectations, prompting the company to decide eventually to end its involvement with the model engine manufacturing industry. The question of precisely when the Hope range finally disappeared from the scene remains unanswered at present. Such references as are available (quoted in the detailed descriptions presented elsewhere) confirm that the Hope "Super" models were still in production as of 1956, but at present that's as far forward as I’m able to trace the range with any authority. What is certain is that the Hope range had faded both from existence and from memory as of 1962, when "American Modeller" published its first Global Engine Review in its 1963 Annual released in late 1962. This very comprehensive Review was unattributed, but a great deal of internal evidence indicates that it was prepared by Peter Chinn. Indeed, there can have been few if any other individuals who were capable of assembling such a summary at that time.

Hope's evident failure in this respect was doubtless caused at least in part by a rather insidious factor that was more or less unnoticed at the time. This was the now-recognizable fact that the world market for model engines had already peaked and was even then entering the slow but steady decline which it has experienced ever since. In large part, this was driven by the increasing dominance of the R/C market which elevated the costs of participation in the hobby to new levels and had the unfortunate effect of imposing a "means test" upon would-be modellers which doubtless discouraged many (particularly the younger set) from becoming involved. Back to "rich adult men" again.......... the wheel was coming full circle. In the new market that was being shaped by these forces, only the best-established, most diverse and most aggressively-promoted marques would survive. The death-blow was probably administered by O.S. and Enya, whose newly-introduced Max-II 29 and 29-III models respectively simply buried the Hope Super 29 in performance terms, as did Enya's Model 4003 in the .19 class and Model 3001 in the .09 category. This shortcoming performance-wise would undoubtedly have been an inhibiting factor as far as the enthusiasm of most distributors and retailers was concerned, and even the lower price of the Hope models would have been insufficient to offset this. In addition, there is no evidence that Hope ever produced an R/C version of any of their designs. It thus follows that any existing distribution chain would be inclined to drop the Hope line as sales inevitably dwindled in the face of the competition from Enya and O.S.. The competing Fuji marque probably only survived this period due to its far greater diversity coupled with a better-established market presence and extremely competitive pricing. Regardless of the reason, it seems certain that the Hope company finally abandoned its efforts to compete with the likes of Enya, O.S. and Fuji at some intermediate point in the latter 1950's. They were not alone in doing so - the competing Mamiya model engine range also disappeared from the field during this period, likely for similar reasons. If I had to give my "best guess" (and it would be no more than that) regarding the year in which production ceased, I would probably opt for 1957. An unanswered question in relation to the cessation of production is whether Hope Engineering went out of business altogether or simply moved on to other fields. I’d welcome any information from readers who may be able to enlighten us on this topic. I must also admit to a considerable degree of ongoing uncertainty regarding the dates of the various models described in this summary. It's unlikely that I’m that far off with most of the dates given, but at present there are no guarantees! It would be of the greatest assistance if anyone having Hope instruction leaflets or promotional material in which different models appear in association could make scans of that material available to me. Finally, I confess to entertaining lingering doubts regarding the completeness of the above summary in terms of the models covered. It appears to me to be not unlikely that there were Hope models of which I’m presently unaware. If any reader is able to enlighten me in this regard, especially with a few images, I'd be extremely grateful! I will pass along any such information received, with full acknowledgement. Conclusion This completes my overview of the Hope models of which I’m presently aware. I hope (groan!) that you've enjoyed this attempt to summarize one of the least-documented model engine ranges of the early post-war period. I invite those readers who wish to obtain more detailed information to dip into the companion articles on the 19, 29 and 60 displacement categories, in which the various models are described in considerably more detail. In doing so, I repeat my earlier cautionary note to the effect that all dates given are best estimates only and the coverage may well be incomplete. _________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN June 2009 This revised edition published here May 2025 |

| |

The material which follows represents what I believe to be the first-ever published major study in the English language of one of the now-forgotten Japanese model engine ranges - the Hope marque. In this article, I’ll present an overview of the range and the historical context in which this surprisingly prolific range became established, flourished for a time and then died.

The material which follows represents what I believe to be the first-ever published major study in the English language of one of the now-forgotten Japanese model engine ranges - the Hope marque. In this article, I’ll present an overview of the range and the historical context in which this surprisingly prolific range became established, flourished for a time and then died. This re-awakening extended into all facets of the Japanese economy, including the field of model engine manufacture. It's vitally important to understand at this point that this was in every sense a re-awakening - unknown to most Western modellers, a thriving power modelling scene had existed in Japan prior to WW2. In response to the consequent pre-war domestic demand, a significant number of commercially-produced Japanese model engine ranges had appeared in the 1930's, more or less in parallel with similar developments in the United States.

This re-awakening extended into all facets of the Japanese economy, including the field of model engine manufacture. It's vitally important to understand at this point that this was in every sense a re-awakening - unknown to most Western modellers, a thriving power modelling scene had existed in Japan prior to WW2. In response to the consequent pre-war domestic demand, a significant number of commercially-produced Japanese model engine ranges had appeared in the 1930's, more or less in parallel with similar developments in the United States. Following the conclusion of WW2, Shigeo Ogawa (the founder of the

Following the conclusion of WW2, Shigeo Ogawa (the founder of the  There were other Japanese companies who entered (or in some cases re-entered) the model engine business after the war with high hopes of the kind of long-term success that attended the efforts of the above-named manufacturers but who were destined to depart the scene relatively quickly and be almost immediately forgotten. Only the more knowledgeable of today's model engine enthusiasts will recall the names of

There were other Japanese companies who entered (or in some cases re-entered) the model engine business after the war with high hopes of the kind of long-term success that attended the efforts of the above-named manufacturers but who were destined to depart the scene relatively quickly and be almost immediately forgotten. Only the more knowledgeable of today's model engine enthusiasts will recall the names of  The origins of the Hope range are very much obscured by a combination of the language barrier and the passage of time, at least in terms of accessible information in the English language. My knowledge of this phase of the range's existence is limited to a few comments received from several Japanese colleagues regarding the existence of a connection between the Hope range and the earlier K

The origins of the Hope range are very much obscured by a combination of the language barrier and the passage of time, at least in terms of accessible information in the English language. My knowledge of this phase of the range's existence is limited to a few comments received from several Japanese colleagues regarding the existence of a connection between the Hope range and the earlier K

The earliest form of the Hope B was in essence a re-badged Kotobuki 29. It was built up around a Kotobuki crankcase which was painted black and stamped with the Hope B identification. This underscores the previously-noted probability that the Hope enterprise was simply the Kotobuki initiative being continued under an Anglicized name. However, this original interim variant didn't last long in production - a number of changes were made quite quickly to produce the form of the engine which is most familiar today.

The earliest form of the Hope B was in essence a re-badged Kotobuki 29. It was built up around a Kotobuki crankcase which was painted black and stamped with the Hope B identification. This underscores the previously-noted probability that the Hope enterprise was simply the Kotobuki initiative being continued under an Anglicized name. However, this original interim variant didn't last long in production - a number of changes were made quite quickly to produce the form of the engine which is most familiar today. The design simplicity of the Hope B was by no means unique to the Hope range but in fact reflected a minimalist trait which pervaded Japanese technical thinking at the time in question. For the most part, both pre-war and early post-war Japanese technical designs in many fields reflected a primary concern with function rather than form. Basically, things were designed to do their job effectively while remaining as simple as the achievement of that goal allowed them to.

The design simplicity of the Hope B was by no means unique to the Hope range but in fact reflected a minimalist trait which pervaded Japanese technical thinking at the time in question. For the most part, both pre-war and early post-war Japanese technical designs in many fields reflected a primary concern with function rather than form. Basically, things were designed to do their job effectively while remaining as simple as the achievement of that goal allowed them to. To a large extent this process of Anglicization doubtless reflected the early post-war prevalence of anti-Japanese prejudice within the predominantly English-speaking countries, notably the USA, which had opposed the Japanese and sustained great losses in the bitter conflict of WW2. To any Japanese manufacturer harbouring the ambition of entering the international market, it may well have appeared wise to avoid the appearance of Japanese characters anywhere on either the engines or their packaging. Even the choice of names for the Hope line (Hope B, Hope New, Hope Super) appears calculated to "Anglicize" the products as far as possible. In the context of the times, this would be quite understandable.

To a large extent this process of Anglicization doubtless reflected the early post-war prevalence of anti-Japanese prejudice within the predominantly English-speaking countries, notably the USA, which had opposed the Japanese and sustained great losses in the bitter conflict of WW2. To any Japanese manufacturer harbouring the ambition of entering the international market, it may well have appeared wise to avoid the appearance of Japanese characters anywhere on either the engines or their packaging. Even the choice of names for the Hope line (Hope B, Hope New, Hope Super) appears calculated to "Anglicize" the products as far as possible. In the context of the times, this would be quite understandable. It's particularly noteworthy that a surprisingly high level of attention appears to have been paid by early post-war Japanese manufacturers to the .60 cuin. (10 cc) displacement category. O.S., Super Devil,

It's particularly noteworthy that a surprisingly high level of attention appears to have been paid by early post-war Japanese manufacturers to the .60 cuin. (10 cc) displacement category. O.S., Super Devil,  In addition, it appears likely that engines in this large displacement category were seen as "prestige" or "flagship" products that underlined the technical credentials of their manufacturers. Indeed, the majority of these big-bore post-war models were "racing" designs which were clearly directed towards the high-profile competition classes in which such engines could compete. The post-war emergence of control-line flying undoubtedly accelerated this trend.

In addition, it appears likely that engines in this large displacement category were seen as "prestige" or "flagship" products that underlined the technical credentials of their manufacturers. Indeed, the majority of these big-bore post-war models were "racing" designs which were clearly directed towards the high-profile competition classes in which such engines could compete. The post-war emergence of control-line flying undoubtedly accelerated this trend. This challenge was not new - a pre-war Japanese 9.6 cc engine had typically cost about 60-65 Yen, which translated into roughly US$20 at the then-current 1930's exchange rate of some 3.3 yen to the US dollar. Even in the USA, this would have been a high-cost "luxury" item in the pre-war period. In Japan, such products were clearly the exclusive province of "rich adult men", to quote well-known Japanese model engine icon Akira Fujimuro. Even so, there must have been quite a few "rich adult men" in pre-war Japan because there appear to have been numerous buyers for these engines during the years prior to Japan's entry into the war.

This challenge was not new - a pre-war Japanese 9.6 cc engine had typically cost about 60-65 Yen, which translated into roughly US$20 at the then-current 1930's exchange rate of some 3.3 yen to the US dollar. Even in the USA, this would have been a high-cost "luxury" item in the pre-war period. In Japan, such products were clearly the exclusive province of "rich adult men", to quote well-known Japanese model engine icon Akira Fujimuro. Even so, there must have been quite a few "rich adult men" in pre-war Japan because there appear to have been numerous buyers for these engines during the years prior to Japan's entry into the war. The situation facing Japanese manufacturers at this time was actually very much like that facing the post-war British makers of the

The situation facing Japanese manufacturers at this time was actually very much like that facing the post-war British makers of the

Super 60 (or Super Hope 60). It is perhaps the least known of the Hope engines, and readers wishing to learn more are directed to the

Super 60 (or Super Hope 60). It is perhaps the least known of the Hope engines, and readers wishing to learn more are directed to the  At some point in the late 1940's the Hope range was further expanded by the introduction of the company's first .19 cuin. design. It's impossible to be certain regarding the introductory date of this model, but the fact that it was a sandcast engine like its Hope B and Super Hope 60 counterparts suggests that it started life as a concurrent production.

At some point in the late 1940's the Hope range was further expanded by the introduction of the company's first .19 cuin. design. It's impossible to be certain regarding the introductory date of this model, but the fact that it was a sandcast engine like its Hope B and Super Hope 60 counterparts suggests that it started life as a concurrent production. The new Hope 19 showed a considerable degree of design progression from the Hope B, abandoning the radial porting of its sibling in favour of the far more fashionable cross-flow loop scavenging. The initial variant featured a bolt-on front housing with an integrally-cast backplate, but this arrangement was sooon amended to the combination of screw-in backplate and bolt-on metal tank which had been features of the Hope B. A separate cylinder head was employed in place of the former blind bore. This resulted in a substantially improved combustion chamber configuration. The cylinder and head were initially retained by only two screws, but two additional head screws were soon added to improve the head's sealing characteristics.

The new Hope 19 showed a considerable degree of design progression from the Hope B, abandoning the radial porting of its sibling in favour of the far more fashionable cross-flow loop scavenging. The initial variant featured a bolt-on front housing with an integrally-cast backplate, but this arrangement was sooon amended to the combination of screw-in backplate and bolt-on metal tank which had been features of the Hope B. A separate cylinder head was employed in place of the former blind bore. This resulted in a substantially improved combustion chamber configuration. The cylinder and head were initially retained by only two screws, but two additional head screws were soon added to improve the head's sealing characteristics.  By this time it seems certain that the Super Hope 60 was no longer in production, since it was woefully out-dated by that time. The range now consisted of the previously-noted sandcast models in the popular .19 and .29 cuin. displacement categories. The reception of these models in the domestic marketplace had clearly been sufficiently positive to justify further development of the engines and improvements in production technology.

By this time it seems certain that the Super Hope 60 was no longer in production, since it was woefully out-dated by that time. The range now consisted of the previously-noted sandcast models in the popular .19 and .29 cuin. displacement categories. The reception of these models in the domestic marketplace had clearly been sufficiently positive to justify further development of the engines and improvements in production technology. Hope B. In addition, KO had an O&R-influenced die-cast .19 glow-plug model on offer, and

Hope B. In addition, KO had an O&R-influenced die-cast .19 glow-plug model on offer, and  The die-cast .19 model was generally very similar to its sand-cast predecessor, merely being cleaned up a little. By contrast, the original "New 29" model was a refreshingly different design which featured a horizontally-split crankcase. This feature allowed the exhaust stack to be positioned on either the left or right side, perhaps to accommodate American or European market tastes.

The die-cast .19 model was generally very similar to its sand-cast predecessor, merely being cleaned up a little. By contrast, the original "New 29" model was a refreshingly different design which featured a horizontally-split crankcase. This feature allowed the exhaust stack to be positioned on either the left or right side, perhaps to accommodate American or European market tastes.

In the latter part of 1952, the Hope New 29 was updated through the provision of a revised cylinder design, a separate detachable cylinder head and an improved combustion chamber. Details of this model will be found in my companion article on the

In the latter part of 1952, the Hope New 29 was updated through the provision of a revised cylinder design, a separate detachable cylinder head and an improved combustion chamber. Details of this model will be found in my companion article on the

The completely revised Hope designs which now appeared were designated as the "Super" series by the company. There were revised designs in both the .19 and .29 cuin. categories, while in addition Hope subsequently entered the popular .09 category as well. More of that model below ..............

The completely revised Hope designs which now appeared were designated as the "Super" series by the company. There were revised designs in both the .19 and .29 cuin. categories, while in addition Hope subsequently entered the popular .09 category as well. More of that model below ..............

Based on the attention paid to the .099 displacement category by Japanese manufacturers of model aero engines during the first post-WW2 decade, it would appear that the .099 cuin. displacement category enjoyed a very high level of customer support in the Asian markets in which the Hope engines competed for the most part. Indeed, the .099 category seems to have come to occupy the same major market niche in Japan which the

Based on the attention paid to the .099 displacement category by Japanese manufacturers of model aero engines during the first post-WW2 decade, it would appear that the .099 cuin. displacement category enjoyed a very high level of customer support in the Asian markets in which the Hope engines competed for the most part. Indeed, the .099 category seems to have come to occupy the same major market niche in Japan which the  Boxer range threw their hats into the ring in around 1951, KO added their own design to the list in 1953 and Enya was actually a Johnny-come-lately among Japanese manufacturers in this displacement category, waiting until May 1954 to launch their own initial .099 model, the excellent Enya 09 Model 3001.

Boxer range threw their hats into the ring in around 1951, KO added their own design to the list in 1953 and Enya was actually a Johnny-come-lately among Japanese manufacturers in this displacement category, waiting until May 1954 to launch their own initial .099 model, the excellent Enya 09 Model 3001.

As previously stated, I don't presently have access to an example of this little-known model. However, thanks to the kindness of the late David Owen, I am at least able to present an image of this engine. This image shows that this neat little .09 glow-plug engine was very much in step with the other Hope "Super" models in design terms. It featured the same blend of a one-piece die-cast matte-finished crankcase with the backplate secured by four screws, together with a cylinder having integral cooling fins and a separate finned alloy head. The cylinder/head assembly was secured in exactly the same manner as on the larger engines, using two short and two long screws. A further similarity was the left-side location of the exhaust stack.

As previously stated, I don't presently have access to an example of this little-known model. However, thanks to the kindness of the late David Owen, I am at least able to present an image of this engine. This image shows that this neat little .09 glow-plug engine was very much in step with the other Hope "Super" models in design terms. It featured the same blend of a one-piece die-cast matte-finished crankcase with the backplate secured by four screws, together with a cylinder having integral cooling fins and a separate finned alloy head. The cylinder/head assembly was secured in exactly the same manner as on the larger engines, using two short and two long screws. A further similarity was the left-side location of the exhaust stack. Be that as it may, the Hope engines were not mentioned even retrospectively in the 1962 Review. It's clear that as of that year the range had been gone for some time. As I trust I've shown, there was not much wrong with the engines themselves, and they seem to have been relatively popular in Japan if reports from that country be true. They were also priced very competitively. I must conclude that it was most likely a rather half-hearted and ultimately unsuccessful international marketing effort that persuaded the company that they were not riding a long-term winner.

Be that as it may, the Hope engines were not mentioned even retrospectively in the 1962 Review. It's clear that as of that year the range had been gone for some time. As I trust I've shown, there was not much wrong with the engines themselves, and they seem to have been relatively popular in Japan if reports from that country be true. They were also priced very competitively. I must conclude that it was most likely a rather half-hearted and ultimately unsuccessful international marketing effort that persuaded the company that they were not riding a long-term winner.