|

|

Californian C/I Classic - the Air-O Diesel

My initial study of this engine and its background led to the July 2010 publication of the original version of this article on the late Ron Chernich’s “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. So why the article’s re-publication here? Mainly because my mate Ron left us in early 2014 without sharing the access codes for his heavily-encrypted site. Because no maintenance has since been possible, the MEN site is slowly but perceptibly deteriorating as the various links and short-cuts fail progressively - an inevitable process which can have only one ending in the long run. I was unwilling to risk the loss of reader access to the information so painstakingly gathered on the Air-O Diesel, hence the article’s re-publication here. Perhaps of equal importance, I’ve since become more broadly aware of the background to the appearance of this engine. I’ve also been able to come up with a few additional illustrations in addition to improving upon many of those already included in the earlier article. Finally, a number of key links associated with the Air-O Diesel story were omitted from the original text, while many of those that were included have since been updated or replaced. All of these issues required addressing through the publication of a revised version of the article. As usual, I’ll begin with a little background in order to place the Air-O Diesel in its appropriate context. Background The model diesel, or more correctly compression ignition engine, was a Swiss concept of the 1930’s which was further developed during WW2 in a number of European countries despite the conflict which engulfed Europe during those wartime years. The state of hostilities prevented much coordinated international development from taking place. However, the conclusion of the war allowed a resumption of interaction between modellers in different countries, hence creating conditions under which the pace of model diesel development in Europe became greatly accelerated. By 1946 a number of European countries were producing diesels which performed very well indeed by the standards of their day. Britain was a late starter in the diesel field, but caught up very rapidly.

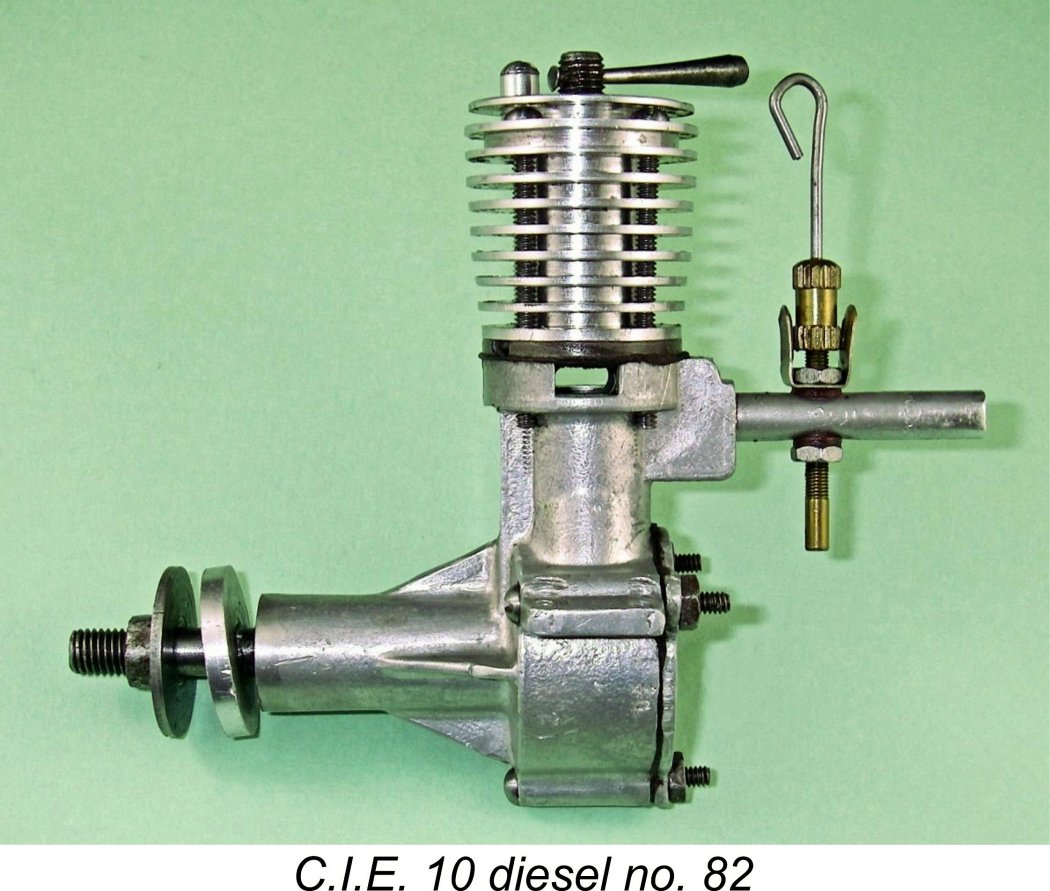

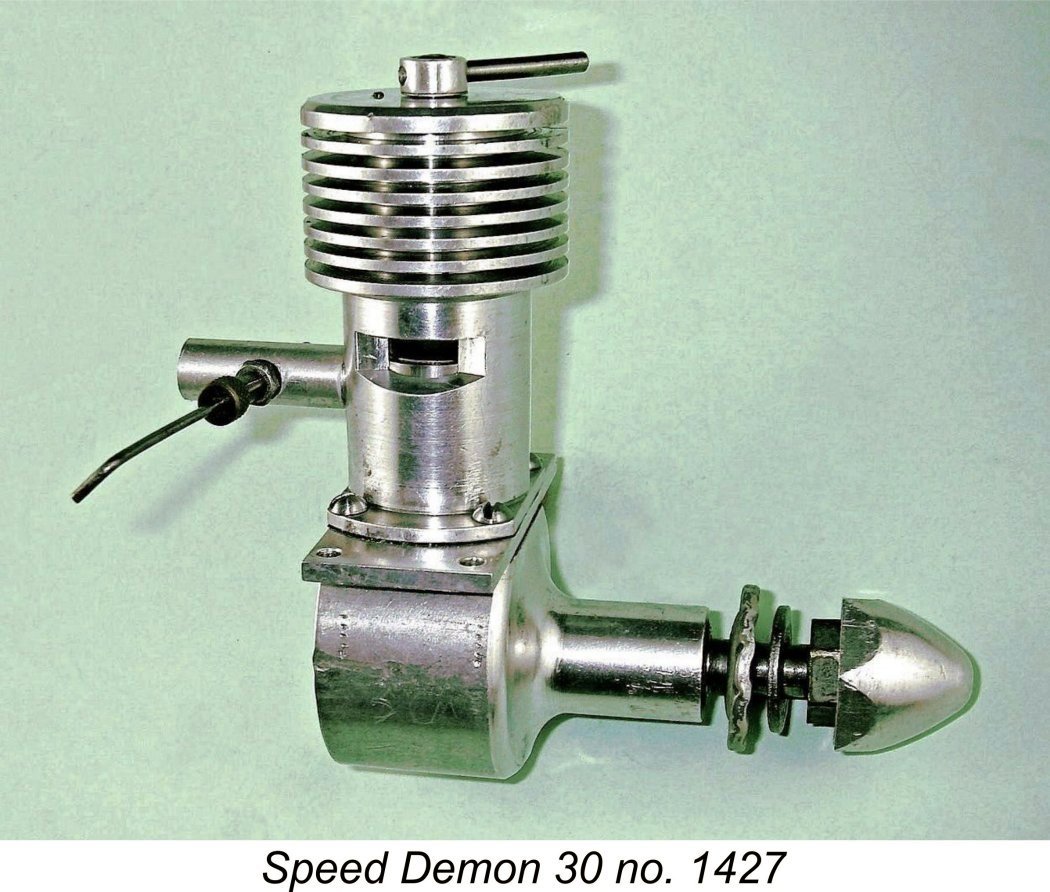

As a result, a surprising number of North American manufacturers developed model diesel designs of their own during the period 1946-1948 before the glow-plug swept all before it in the USA and the diesel faded into relative obscurity in that particular market. In fact, it may astonish some readers to learn that during this period the number of North American model diesel manufacturers - or would-be manufacturers in some cases - equaled or perhaps even exceeded the number of mainstream British diesel manufacturers during the same period! In addition to our main subject Air-O, names such as Drone, Vivell, Mite, C.I.E., Speed Demon, Ken, Deezil and Micro come immediately to mind. Moreover, there were quite a few others such as AHC, DeLong, EDCO, Thermite, Queen Bee and Strato (the latter two in Canada) who developed diesel designs which never actually reached the series production stage.

In doing so, it's my pleasure to pay tribute to the wealth of accessible information on these and other American model engines which has been painstakingly assembled over the years by my valued friend and colleague Tim Dannels editor of the sadly now-discontinued "Engine Collectors' Journal" (ECJ) and compiler of the indispensable "American Model Engine Encyclopedia" (AMEE). It would be impossible to write with any authority about American model engines without drawing upon Tim's work, and I'd like to acknowledge my immense debt to him in the present instance. That said, I wish to emphasize that any errors or omissions in the following text are my own sole responsibility. Capsule History of the Air-O Model Supply Co. The Air-O Model Supply Company was the direct descendant of the Bunch Model Airplane Co. of Los Angeles, California. This latter company had been founded in 1934 by then thirty-year old Joel Danner "Dan" Bunch (1904-1948), initially as a hobby shop and distribution house rather than an engine manufacturing business. Dan Bunch was a keen aeromodeller of long standing who had a number of published modelling articles to his credit and had acquired a great deal of relevant knowledge and experience by the time he started his business.

One of the early product lines handled by the Bunch company was the Gwin-Aero series of model engines which was initially manufactured in early 1936 on a part-time basis in Indianapolis, Indiana by Joseph Gwin, who just happened to be Dan Bunch's father-in-law! This project was something of an experiment on the part of Joseph Gwin - he simply wanted to see if he could make a practical engine for model flying purposes. At this stage, Dan Bunch's role was merely to gauge the engines' sales potential through his marketing efforts.

In addition to the Gwin-Aero models, the Bunch company also made engines under the Mighty Midget designation. These were available both as complete engines and in kit form. Later pre-war products included the Bunch Warrior, Speedway and Tiger Aero models.

As WW2 drew closer to its increasingly-predictable end, limited commercial production of model engines in the USA resumed in August 1944 when the US War Production Board decided to release sufficient Dan Bunch certainly gave every indication that he had by no means lost interest in the field of model engine design - one of his first post-war projects was to undertake the design of the 1946 Contestor D-60 models for the Lucas & Smith Manufacturing Company of Los Angeles, with which Bunch had by then become associated. However, the Contestor was destined to be the last new design with which Dan Bunch was directly involved, since he withdrew from the field at that point, dying in 1948 at the tragically young age of only 44 years. Following Dan Bunch's withdrawal from the model engine scene in 1946, the manufacture and further development of the Bunch range was taken over by a new company, the Air-O Model Supply Company of Hawthorne, California, a satellite community of Los Angeles lying to the south-west of the main city. The driving force behind the new venture was a gentleman by the name of Ray Accord. The Air-O diesel which forms our main subject was a product of this successor company.

Following the introduction of the Air-O Diesel, the Air-O company went on to introduce a glow-plug version of the Mighty Midget in 1948, also producing a slightly different model of identical displacement called the Air-O Cobra in both spark and glow-plug ignition versions. The Cobra engines were also produced by Air-O for sale in the eastern USA by Berkeley Models Inc. of Brooklyn, New York. These engines were sold under the Berkeley name, but they were to all intents and purposes identical to the Air-O Cobra models. Production of all Air-O models appears to have ceased in late 1949 or possibly early 1950. The Air-O company thus had a relatively short life, but the Air-O Diesel's production life was even shorter. Having first appeared on the market in late 1947, it survived more or less until the end of Air-O production. However, this gave it a production life of only some two years or so at most. It's unclear how many Air-O Diesels were produced during this period, but there must have been quite a few of them, because they still seem to crop up fairly regularly, having failed as yet to make the jump into the "unobtanium" class like a good few others. The Air-O Diesel in the Modelling Media As far as I’m aware, the first reference to this engine in the modelling media is to be found in an article by Edward G. Ingram entitled "Model Motors for 1948" which appeared in the January 1948 issue of “Model Airplane News“ (MAN). This article included details of five contemporary American-made model diesels including the Air-O Diesel, which was featured as one of the heading illustrations along with its contemporary, the DeLong diesel (which never actually reached series production). For some reason, the excellent Vivell 0.102 cuin. diesel was not included even though it certainly existed at this time and other Vivell products were covered. Presumably it had not come to Ingram's attention. The paragraph which referred to the Air-O Diesel read as follows:

Ingram's reference to the engine having been “recently” placed on the market is significant in terms of the Air-O Diesel's chronology. This comment was published in January 1948. Factoring in the necessary allowance for editorial lead-time makes it readily apparent that Ingram must have actually written the comment in November 1947 at the latest. Moreover, at his time of writing the engine had already reached the market if he was reporting accurately. This seems to confirm either August or September 1947 as the engine's likely introductory date. Ingram's note that the compression control functioned in the same manner as the spark advance on a spark-ignition engine is a disarmingly insightful observation. Even today, a surprising number of diesel enthusiasts fail to appreciate the fact that the primary function of the compression control is to adjust the ignition timing as opposed to merely the temperature reached on the compression stroke. As Ingram pointed out, this is indeed precisely analogous to the function of the timer arm on a sparker. This was a valuable operational point for Ingram to make since it injected a certain sense of familiarity into the operation of a diesel by someone who was used to spark ignition. The Air-O designer clearly recognised that for higher speeds to be achieved, it would be necessary to have the ability to increase compression above its starting level and thus advance the timing, just as in the case of the spark ignition motor. Such insights spelled the end of the road for the fixed-compression diesel, which had to live or die at its pre-set starting compression ratio which severely limited its maximum speed potential.

Most improbably, the claimed speed at which maximum power of over ¼ BHP was developed was stated in these tables to be no less than 16,500 rpm! This was undoubtedly an uncaught editorial error - the intended figure was surely 6,500 rpm in accordance with the peaking speed noted in Ingram's text reproduced above. Moreover, the claimed output of over ¼ BHP appears at first glance to be rather on the optimistic side given the engine's design specification (but read on!). The claimed speed on both the recommended props (12x6 and 11x10) was stated to be 7,000 rpm. Based upon latter-day test results (see below), this claim appears quite credible on suitably-trimmed props. The recommended fuel mixture (41% ether, 35% castor oil and 24% kerosene) is interesting insofar as it proves beyond doubt that the manufacturers had recognized the benefits of including a substantial The realisation that variable compression allowed the use of a more potent fuel mixture was evidently just beginning to sink in among American model diesel designers. For reasons which I've explained elsewhere, fixed-compression engines like the Drone were more or less stuck with their low-power detonation-prone all-ether fuel with mineral lubricant, but the variable compression revolution was opening the door for considerable experimentation with respect to model diesel fuels.

However, the issue of what constituted an ideal fuel for model diesels was far from settled when the Air-O Diesel appeared. Even in 1948 the Detroit-based makers of the variable-compression Class A Micro-Diesel were still recommending the basic Drone fixed compression mix of three parts ether to one part S.A.E. 20 mineral oil. Thereafter, the more or less wholesale adoption of glow-plug ignition by American modellers from late 1948 onwards effectively put an end to further diesel fuel research in that country, handing the further development of such fuels back to the European designers who had started it all. Description Edward Ingram’s published description of the Air-O Diesel as reproduced above is both relatively comprehensive and for the most part accurate, as Ingram's write-ups generally were. Despite this, it seems worth providing a few more details here based on my personal observations. Apart from the ignition system employed, the engine bears a strong family resemblance to the other models produced by the Air-O company, which in turn owed much to their common Bunch ancestry. Since Ray Accord seems to have served as the chief designer for the Air-O company after it took over the Bunch line, he was presumably the designer of the Air-O Diesel. In designing the Air-O diesel, Ray Accord resisted the temptation to re-invent the wheel, instead using such features of the earlier Bunch engines as would contribute to the creation of a successful diesel design. The Air-O diesel was seemingly based upon the earlier Mighty Midget crankcase casting, having the same 0.75 in. stroke, but used a far narrower bore to obtain the reduced displacement. The general construction of the engine was also based very much upon that of the earlier Bunch models. The mounting spigot for the timer was retained but left un-machined since it was no longer used.

An interesting feature of this engine is the fact that, like the British AMCO .87, it uses a screw-in cylinder despite the consequent fact that there is a definite design orientation of the cylinder and its attached induction tube. This must have been achieved in one of two possible ways: a) by selective assembly, perhaps coupled with a little shimming between the cylinder flange and the case. A shim or gasket is certainly visible between the case and the cylinder flange on the illustrated example. Or alternatively; b) by assembling the cylinder in the case and then drilling or marking the exhaust ports in their correct location, after which the cylinder would have to be unscrewed to finish the porting using the already-drilled exhaust ports as a location guide. This was the approach adopted by AMCO. It required the cylinder and crankcase to be treated as a single unit from there on, and a strong argument against this possibility is the fact that, unlike the AMCO, the cylinder and case are not identically The use of this form of construction naturally offered some significant advantages in terms of reducing overall bulk and weight. In the case of the Air-O Diesel, it certainly paid off on both counts - quite apart from its relatively low weight, the engine is remarkably compact for a diesel of its displacement. The attached image of the Air-O Diesel beside an E.D. Comp Special highlights this compactness - the 4.55 cc Air-O Diesel is in fact very little bulkier than the similarly-ported 2 cc Comp Special and weighs only 1¼ ounces (35 gm) more than the smaller engine. Moreover, this is achieved without significantly compromising the durability of the engine - it seems very sturdy.

Transfer is accomplished by a single internal flute machined into the lower cylinder wall on the right-hand side of the cylinder (viewed from the rear) opposite the point where the induction tube enters at a lower level. The relatively thin cylinder wall means that this transfer flute is necessarily of small depth and hence area. The flute is neatly squared-off at the top to give quite rapid opening. It overlaps the exhaust almost completely. The relatively small bypass area should logically promote quite high transfer gas velocities - a good characteristic in terms of promoting good starting and improved low-end torque development. Exhaust and transfer ports open very late in the stroke. This allows the power stroke to utilize the expanding gasses very completely but also limits potential rpm at the top end, as does the rather small bypass area. There is no way that the engine would run effectively at Ingram's erroneously-cited 16,500 rpm or anywhere near it! The late exhaust opening is likely another factor in promoting the engines's relatively low noise levels during operation.

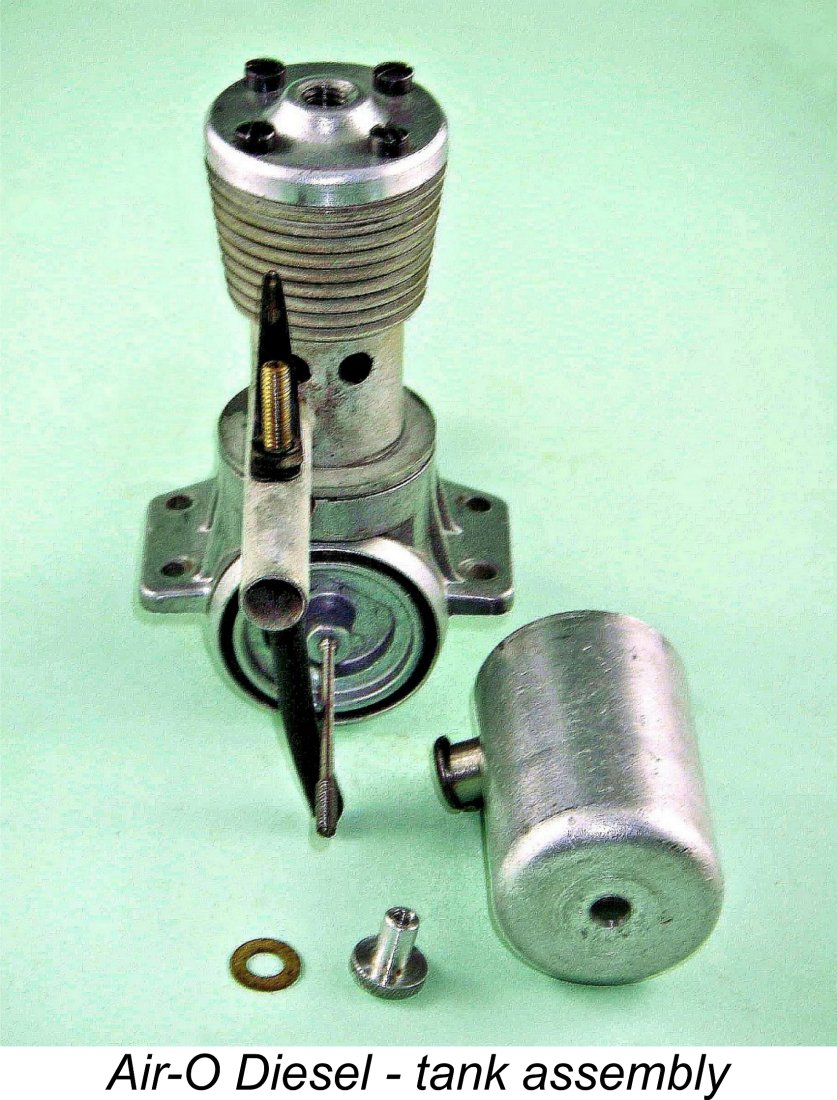

Overall quality of the engine is first-class - all fits are truly excellent. All external steel or brass surfaces on the illustrated example are cadmium-plated, although the earliest examples apparently had a black finish on their cylinders. There were two The one component that looks a bit skimpy at first sight is the con-rod, which seems a little under-nourished for an engine of this size. But it is very strong for its size, being made from chrome-moly The Air-O Diesel is fitted with a metal back tank of extremely generous capacity. This is held in place by a composite system employing a somewhat skinny stud which is threaded at both ends. One end screws into the backplate and the other accommodates an internally-threaded aluminium alloy cap-screw which actually retains the tank. This cap screw is sealed with a gasket - a nice touch. The tank is very securely seated in a radial groove machined around the circumference of the backplate. Again, a gasket is used to ensure a seal. In 1949 the engine appeared in a number of different versions expressly intended for model car use. These latter engines did not have tanks, and some had one of their mounting lugs removed to facilitate mounting in a car chassis. Personal Recollections of the Air-O Diesel I must be one of the relatively few surviving modellers with experience of actually flying an Air-O Diesel! I acquired my first one in the early 1970's (when it was less than 25 years old, and I was a lot younger too!). Sadly, I didn't have a camera back then, so I can't share an image, but I do still retain my notes. I found it to be an extremely easy starter and a very steady runner with plenty of torque for its era - the claimed power output of 0.20 - 0.25 BHP actually seemed quite believable, albeit at pretty low speeds and probably at the low end of that output range. Torque is this engine's strong suit. Apart from its ability to swing a pretty meaningful prop, the engine was nice and light for its size, especially when compared with something like a Drone! So, having a taste for flying weird antique engines at the time (still do), I built a simple ultra-lightweight vintage-styled profile sport control-line model for it, just to get it into the air. The back tank naturally had to be set aside for this purpose (bringing the weight down below 7 ounces), but the engine ran fine on the wedge tank provided instead. Not having an 11x10 prop at the time (the same as that recommended for the Drone, note!), I used a cut-down wide-blade 12x8 prop, which worked well. The engine shifted a lot of air on this prop and the model flew just fine on 52 foot lines, albeit not particularly fast. There was sufficient "urge" for simple manoeuvres like loops and "lazy 8's" to be executed (over long grass, naturally), but I avoided any high-risk stuff in deference to the engine's age. Anything overhead was definitely a bit dodgy! I used the Air-O Diesel for a while just to be different, but then succumbed to some serious pleading and sold the engine to a collector, still in fine condition despite the careful use which it had received. I immediately regretted selling the thing and grabbed the illustrated example when it came along some years later - it is in near-new condition, although it has been mounted and run. I bench-ran it myself a few times, finding it to be just as good as its predecessor. However, I never flew this one. My notes from my "user" period state that the engine was extremely easy to start, needing only two choked turns to get enough fuel into the case for starting. The rather small transfer passage and equally small crankcase volume doubtless combine to provide good transfer gas velocities, and I found that a prime was not required at any time. The compression screw worked well enough, although a normal screw fitted with a built-in tommy bar would have been far more convenient. I actually made one for my first example while I was using it for flying, although I naturally preserved the original Allen screw. The contra piston is a very good fit and the engine held its settings well, which was fortunate since a locking lever cannot be fitted with a recessed Allen key compression adjustment screw. One of the really noteworthy things about the engine is its quietness - for a large-displacement diesel, it is really very quiet indeed! The small drilled exhaust ports with their progressive and very late opening probably account for this. But like many large diesels, the engine runs slightly "harshly" when tuned for maximum speed on a given prop - there is a more or less constant slight misfire about which nothing can be done. In addition, the engine tends to detonate if leaned out too far or even slightly over-compressed. I have always used "modern" diesel fuel in these engines, since the variable compression feature allows for any necessary adjustments to be made. But even the fact that such fuels have ignition improver in them doesn't eliminate the slight tendency to misfire and detonate. The small exhaust ports and rather constricted transfer passage may account for these characteristics, at least in part - scavenging is probably far from perfect. Certainly, both of the examples that I have run at various times exhibited this behaviour. This doesn't affect performance in practical terms to any great extent - running is extremely steady at all times, with no tendency to "hunt" (that bane of Lawrence Sparey's existence!). The Air-O Diesel On Test

The fuel used for these test runs was a more-or-less standard "modern" diesel mix complete with ignition improver. One would expect a modest improvement in performance on such a fuel by comparison with that to be obtained on the manufacturer's recommended un-doped high-ether brew, but the results should be in the same ball-park regardless.

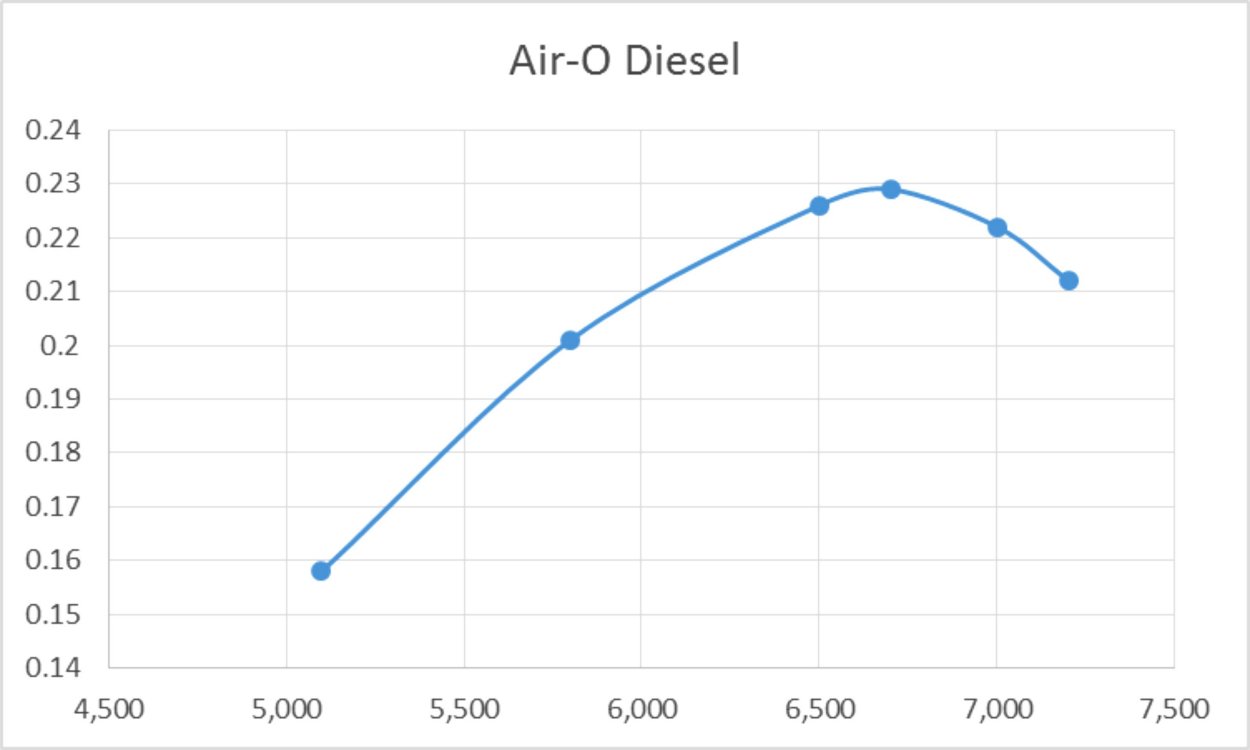

Despite coming off a very long lay-off, the engine gave no trouble at all and was soon running. It started exactly as per my recollections - a prime was never necessary at any point. Two choked flicks induced sufficient fuel for a quick start every time. For cold starting, the compression had to be increased a little above running settings, which is a normal characteristic of larger low-revving diesels running on "modern" diesel fuels, but the needle valve could be left alone once the best setting was established. Hot re-starts were immediate at running settings. The Air-O Diesel turned in an unexpectedly excellent performance, giving prop-rpm figures as follows:

As can be seen, the application of known power absorption coefficients to these figures generates a remarkably smooth power curve implying a peak output of around 0.229 BHP @ 6,700 rpm - very much in line with the manufacturer's claim of ¼ BHP @ 6,500 rpm, and actually a lot better than I was expecting. In fact, this is not that far short of the performance measured for the fixed-compression Drone diesel in my separate article on that engine. No wonder that I found this engine to be such a good motor for vintage flying! I didn't press the engine much past the 7,000 rpm point since it was clear that the peak lay below that speed. I did however time a run with the back tank, finding that it gave a duration of just over three minutes on the 11x7, with which the engine runs on the bench exactly at its indicated peaking speed. This is of course far too long for free flight, and the tank is unsuitable for control line. Moreover, no cut-out is fitted. I suspect that many owners would have made alternative fuel supply arrangements, as I did when I had one of these units in use. Conclusion I must confess to holding the Air-O Diesel in rather high regard - perhaps higher than it deserves! I can only say in my own defence that that I enjoyed using it and found it to be a very dependable and well-mannered companion on the flying field. The more recent test reported above did nothing to diminish my feelings of affection for this engine - it was a real pleasure to test, performing at an unexpectedly high level by the standards of its day! Really, a credit to its manufacturers based on my own personal experience. It's too bad that they didn't carry on from this quite promising start with diesel technology! ________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN July 2010 This revised edition published here September 2023

|

||

| |

This time I’ll take a look at another of the short-lived American diesels from the early post-war era - the Air-O Diesel of 0.28 cuin. (4.55 cc) displacement. This individualistic engine was manufactured to a very good standard by the Air-O Model Supply Co. of Hawthorne, California, during America's brief flirtation with diesels prior to the general adoption of glow-plug ignition in the USA.

This time I’ll take a look at another of the short-lived American diesels from the early post-war era - the Air-O Diesel of 0.28 cuin. (4.55 cc) displacement. This individualistic engine was manufactured to a very good standard by the Air-O Model Supply Co. of Hawthorne, California, during America's brief flirtation with diesels prior to the general adoption of glow-plug ignition in the USA. Following the end of the war, American modellers quickly became aware of the model diesel through the personal importation of European designs by returning US servicemen who had picked them up while on overseas service. It must be recalled that the miniature glow-plug did not become a mainstream commercial reality until late 1947. This being the case, the fact that the model diesel allowed modellers to dispense with the heavy and undependable on-board ignition support equipment needed to run the hitherto ubiquitous spark ignition motors was just as much of an attraction in early post-war America as it was in Europe.

Following the end of the war, American modellers quickly became aware of the model diesel through the personal importation of European designs by returning US servicemen who had picked them up while on overseas service. It must be recalled that the miniature glow-plug did not become a mainstream commercial reality until late 1947. This being the case, the fact that the model diesel allowed modellers to dispense with the heavy and undependable on-board ignition support equipment needed to run the hitherto ubiquitous spark ignition motors was just as much of an attraction in early post-war America as it was in Europe. Many of these North American designs possessed considerable merit, standing up well to comparison with their British and European contemporaries. The famous Drone .297 cuin. (4.85 cc) fixed-compression model was perhaps the best-known and most successful of these American diesels, but a number of the others mentioned above also laid strong claims to the respect of model engine aficionados. It's actually a great pity that the attention of American manufacturers was so quickly diverted away from diesels, since they had got off to an excellent start despite their relatively late entry into the field. We might have seen some highly influential US diesel designs if domestic market conditions had encouraged further development.

Many of these North American designs possessed considerable merit, standing up well to comparison with their British and European contemporaries. The famous Drone .297 cuin. (4.85 cc) fixed-compression model was perhaps the best-known and most successful of these American diesels, but a number of the others mentioned above also laid strong claims to the respect of model engine aficionados. It's actually a great pity that the attention of American manufacturers was so quickly diverted away from diesels, since they had got off to an excellent start despite their relatively late entry into the field. We might have seen some highly influential US diesel designs if domestic market conditions had encouraged further development. My main subject here, the Air-O Diesel, was a relative late-comer to the American diesel market, being introduced in August or September 1947, only a few months in advance of

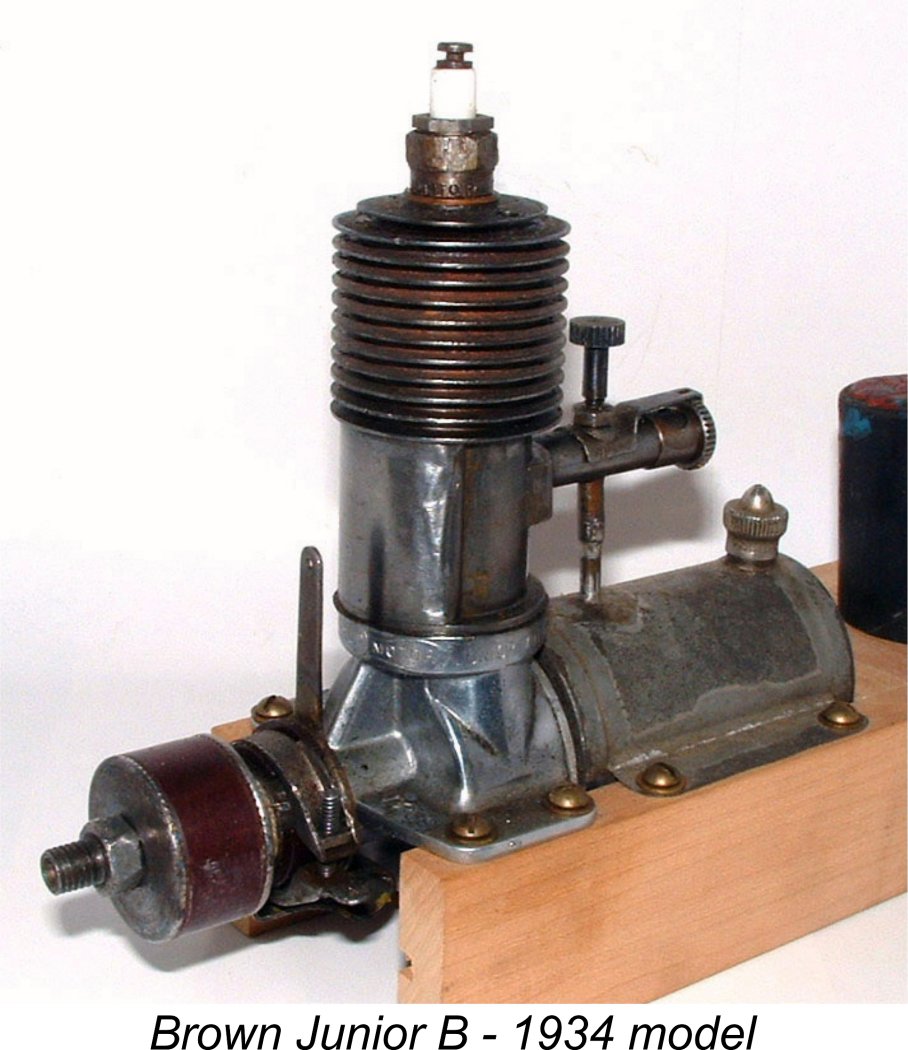

My main subject here, the Air-O Diesel, was a relative late-comer to the American diesel market, being introduced in August or September 1947, only a few months in advance of  Although a number of one-off or short-run engines suitable for use in model aircraft had appeared previously in a number of industrialized countries, the development of the model aero engine into a commercially-viable form had been pioneered by Bill Brown of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and

Although a number of one-off or short-run engines suitable for use in model aircraft had appeared previously in a number of industrialized countries, the development of the model aero engine into a commercially-viable form had been pioneered by Bill Brown of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and  The Gwin-Aero engines proved to have good sales potential, but Joseph Gwin was unable or perhaps unwilling to manufacture them in sufficient quantities to meet demand - they had after all been no more than a part-time experiment as far as he was concerned. Accordingly, in September 1936 the Bunch Model Airplane Co. took over the Gwin-Aero project, commencing the volume manufacture of these engines at a factory in Los Angeles.

The Gwin-Aero engines proved to have good sales potential, but Joseph Gwin was unable or perhaps unwilling to manufacture them in sufficient quantities to meet demand - they had after all been no more than a part-time experiment as far as he was concerned. Accordingly, in September 1936 the Bunch Model Airplane Co. took over the Gwin-Aero project, commencing the volume manufacture of these engines at a factory in Los Angeles.

material and manufacturing capacity for non-military purposes to allow this to happen. This freed the Bunch company to return its focus to its pre-war model engine manufacturing activity.

material and manufacturing capacity for non-military purposes to allow this to happen. This freed the Bunch company to return its focus to its pre-war model engine manufacturing activity.  The Air-O company got started by manufacturing its own 1946 version of the 0.451 cuin. (7.39 cc) Mighty Midget spark ignition motor which had been a mainstay of the former Bunch enterprise. The company's second design, the Air-O Diesel, did not reach the market until late 1947. It should be clear from this chronology that the Air-O Diesel was not a carried-over Bunch design but was in fact an Air-O original, as its name suggests. The Air-O Diesel has sometimes been referred to as a Bunch design (the late

The Air-O company got started by manufacturing its own 1946 version of the 0.451 cuin. (7.39 cc) Mighty Midget spark ignition motor which had been a mainstay of the former Bunch enterprise. The company's second design, the Air-O Diesel, did not reach the market until late 1947. It should be clear from this chronology that the Air-O Diesel was not a carried-over Bunch design but was in fact an Air-O original, as its name suggests. The Air-O Diesel has sometimes been referred to as a Bunch design (the late  "Several new makes of compression-ignition engines have been placed on the market. One recent offering is the Air-O Diesel, produced by the manufacturer of the Air-O Mighty Midget. It is a Class B engine operated on a mixture of 7 parts ether, 6 parts castor oil and 4 parts kerosene. It has a hardened and ground compression adjusting plug or counter piston. This is adjusted to provide low compression for starting and high compression for full power by means of an Allen type setscrew and a wrench. It functions in a manner similar to that of the spark advance on a gasoline engine. The manufacturer claims this provides a distinct advantage over the use of a fixed compression ratio because an engine of this size with the compression ratio set for easy starting cannot approach the maximum power and rpm obtainable with a high compression. Rated at 1/5 hp at 6,500 rpm, the Air-O Diesel is said to be capable of developing over ¼ hp at maximum speed. It weighs only 7 ounces including the fuel tank. The cylinder, including fins, is machined from steel bar stock, and the heat-treated alloy steel piston is centerless ground and lap-fitted. A chrome-moly steel rod is used and the crankshaft main bearing is bronze-bushed. It is a three-port engine with a crankcase die-cast from aluminum alloy. For free flight a 12" diameter 6" pitch propeller is recommended; and for U-control one of 11" diameter and 10" pitch".

"Several new makes of compression-ignition engines have been placed on the market. One recent offering is the Air-O Diesel, produced by the manufacturer of the Air-O Mighty Midget. It is a Class B engine operated on a mixture of 7 parts ether, 6 parts castor oil and 4 parts kerosene. It has a hardened and ground compression adjusting plug or counter piston. This is adjusted to provide low compression for starting and high compression for full power by means of an Allen type setscrew and a wrench. It functions in a manner similar to that of the spark advance on a gasoline engine. The manufacturer claims this provides a distinct advantage over the use of a fixed compression ratio because an engine of this size with the compression ratio set for easy starting cannot approach the maximum power and rpm obtainable with a high compression. Rated at 1/5 hp at 6,500 rpm, the Air-O Diesel is said to be capable of developing over ¼ hp at maximum speed. It weighs only 7 ounces including the fuel tank. The cylinder, including fins, is machined from steel bar stock, and the heat-treated alloy steel piston is centerless ground and lap-fitted. A chrome-moly steel rod is used and the crankshaft main bearing is bronze-bushed. It is a three-port engine with a crankcase die-cast from aluminum alloy. For free flight a 12" diameter 6" pitch propeller is recommended; and for U-control one of 11" diameter and 10" pitch". A number of further details were provided in the extensive tables of technical data which accompanied Ingram’s article. Bore and stroke were given as 0.687 in. (11/16 in./17.45 mm) x 0.750 in. (3/4 in./19.05 mm) respectively for a displacement of .278 cuin (4.55 cc). These figures check out by direct measurement. The stroke was identical to that of the Mighty Midget, but the bore was reduced from 0.875 in. (22.22 mm) to achieve the reduced displacement.

A number of further details were provided in the extensive tables of technical data which accompanied Ingram’s article. Bore and stroke were given as 0.687 in. (11/16 in./17.45 mm) x 0.750 in. (3/4 in./19.05 mm) respectively for a displacement of .278 cuin (4.55 cc). These figures check out by direct measurement. The stroke was identical to that of the Mighty Midget, but the bore was reduced from 0.875 in. (22.22 mm) to achieve the reduced displacement.

The Air-O and C.I.E. mixes represented a significant step towards the basic formula that remains

The Air-O and C.I.E. mixes represented a significant step towards the basic formula that remains

The result was a basically conventional long-stroke side-port variable-compression diesel engine of its day. With nominal bore and stroke measurements of 11/16 in. (0.6875 in./17.46 mm) and 3/4 in. (0.750 in./19.05 mm) respectively, it had a displacement of 0.278 cuin. (4.55 cc), as reported by Ingram. The engine weighs a quite reasonable 7.125 ounces (202 gm) with tank - a fraction more than the weight given by Ingram, but still a very creditable figure for a 4.55 cc diesel of its day, especially one equipped with a tank. For comparison, the contemporary Drone Mk. I diesel weighed in at all of 9.7 ounces (275 gm).

The result was a basically conventional long-stroke side-port variable-compression diesel engine of its day. With nominal bore and stroke measurements of 11/16 in. (0.6875 in./17.46 mm) and 3/4 in. (0.750 in./19.05 mm) respectively, it had a displacement of 0.278 cuin. (4.55 cc), as reported by Ingram. The engine weighs a quite reasonable 7.125 ounces (202 gm) with tank - a fraction more than the weight given by Ingram, but still a very creditable figure for a 4.55 cc diesel of its day, especially one equipped with a tank. For comparison, the contemporary Drone Mk. I diesel weighed in at all of 9.7 ounces (275 gm).

The twin rear-facing exhaust ports of the Air-O Diesel are simple drillings through the cylinder wall. This of course results in progressive opening of the exhaust rather than the instant full-width opening which a square-cut port provides. This may help to explain the relatively attenuated noise levels produced by one of these engines when running. The induction tube is brazed onto the cylinder, feeding the crankcase though a piston-controlled induction port of generous area drilled obliquely through the left rear of the cylinder below exhaust port level.

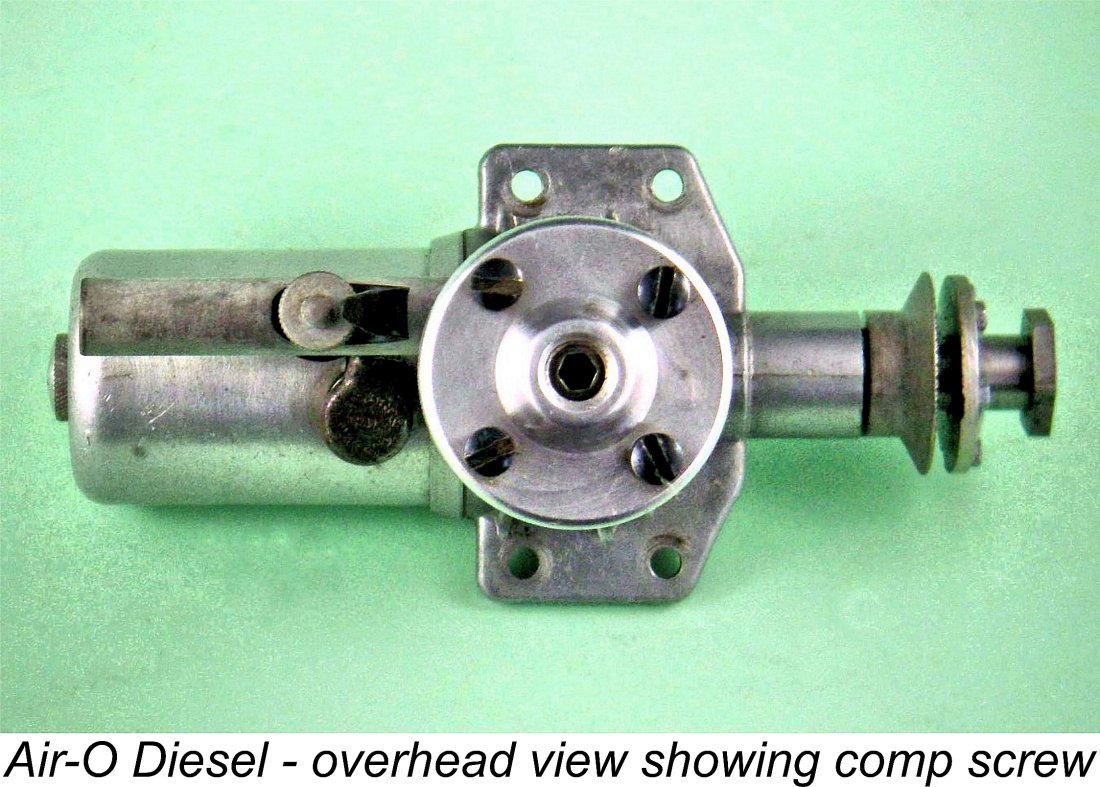

The twin rear-facing exhaust ports of the Air-O Diesel are simple drillings through the cylinder wall. This of course results in progressive opening of the exhaust rather than the instant full-width opening which a square-cut port provides. This may help to explain the relatively attenuated noise levels produced by one of these engines when running. The induction tube is brazed onto the cylinder, feeding the crankcase though a piston-controlled induction port of generous area drilled obliquely through the left rear of the cylinder below exhaust port level.  Another unusual feature is the compression control, which is a simple Allen-head set screw instead of the more usual tommy bar arrangement. It must be said that this is a less-than-ideal arrangement - inserting the end of the Allen wrench into the socket of this set screw while the engine is running (and hence vibrating!) is a bit of an inconvenience. However, it works well enough in practise and gives the engine a very clean and elegant profile. The socket in the head of the set screw is quite deep and retains the Allen key very well during starting.

Another unusual feature is the compression control, which is a simple Allen-head set screw instead of the more usual tommy bar arrangement. It must be said that this is a less-than-ideal arrangement - inserting the end of the Allen wrench into the socket of this set screw while the engine is running (and hence vibrating!) is a bit of an inconvenience. However, it works well enough in practise and gives the engine a very clean and elegant profile. The socket in the head of the set screw is quite deep and retains the Allen key very well during starting.

Having assembled a set of calibrated airscrews for which power absorption coefficients were reliably known, I decided that prior to the completion of this article I should run some tests on my current example of the Air-O Diesel both to reinforce my memories and notes as summarized above and to establish the engine's true level of performance. Accordingly, I set it up in the test stand to give it an outing on a range of suitable props.

Having assembled a set of calibrated airscrews for which power absorption coefficients were reliably known, I decided that prior to the completion of this article I should run some tests on my current example of the Air-O Diesel both to reinforce my memories and notes as summarized above and to establish the engine's true level of performance. Accordingly, I set it up in the test stand to give it an outing on a range of suitable props. I used the Allen screw compression adjustment for this test. As noted earlier, the socket in the screw is quite deep, and the Allen key stays in place during starting with little problem. The only challenge is re-inserting it if necessary while the engine is running - the vibration is not excessive, but it does make fitting the key a little tricky on occasion.

I used the Allen screw compression adjustment for this test. As noted earlier, the socket in the screw is quite deep, and the Allen key stays in place during starting with little problem. The only challenge is re-inserting it if necessary while the engine is running - the vibration is not excessive, but it does make fitting the key a little tricky on occasion.